Highlights

-

•

Lymph node metastasis of osteosarcoma, which is a rare entity.

-

•

Metastatic patterns could not be clearly explained.

-

•

The effects of lymph node metastasis on prognosis are also not clearly defined and further studies are needed.

Keywords: Tumor, Lymph node metastasis, Osteosarcoma, Osteoblastic osteosarkoma

Abstract

INTRODUCTION

We report a case with lymph node metastasis of osteosarcoma, which is a rare entity in comparison to hematogeneous lung or bone metastasis.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

Twenty-seven years old male patient referred to our clinic complaining of ongoing left knee pain and swelling since one month without a history of prior trauma. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a mass of malignant nature which causes more prominent expansion and destruction of the bone distally with periosteal reaction. A lymphadenomegaly 16 mm × 13 mm in diameter was also present in the popliteal fossa having the same signal pattern with the primary lesion. Thirteen weeks following the first referral of the patient, wide resection and reconstruction with modular tumor prosthesis was performed. Popliteal lymph node was excised through the same incision. Pathologic examination of the resected speciman reported osteoblastic osteosarcoma. The lymph node extirpated from the popliteal fossa was reported to be a metastasis of the primary tumor.

DISCUSSION

Osteosarcoma of the long bones is the most common primary malignant bone neoplasm of both childhood and adulthood. Osteosarcomas commonly metastasize hematogeneously to the lungs and bones. Lymph node metastasis is a rare entity. Similar studies report rates between 2.3% and 4%. It is not clearly explained, how lymph node metastasis in osteosarcoma occurs despite lack of lymphatic drainage in normal cortical and spongious bone.

CONCLUSION

Lymph node metastasis of osteosarcoma is a rare entity and metastatic patterns could not be clearly explained. On the other hand, the effects of lymph node metastasis on prognosis are also not clearly defined and further studies are needed.

1. Introduction

We report a case with lymph node metastasis of osteosarcoma, which is a rare entity in comparison to hematogeneous lung or bone metastasis.

Osteosarcoma of the long bones is the most common primary malignant bone neoplasm of both childhood and adulthood. Twenty percent of all malignant bone tumors are osteosarcomas. It is more common in males (1.5:1–2:1) than in females. Distal femur, proximal tibia and proximal humerus are most commonly affected sites where bone growth is fastest.1 Most of osteosarcomas occur as conventional osteosarcomas, histologically subdivided as osteoblastic, fibroblastic and chondroblastic types. Osteosarcomas commonly metastasize hematogeneously to the lungs and bones. Lymph node metastasis is a rare entity.2–4

2. Case presentation

Twenty-seven years old male patient referred to our clinic complaining of ongoing left knee pain and swelling since one month without a history of prior trauma. Initial radiographic evaluation showed a sclerotic lesion filling the whole proximal tibial epiphysis and metaphysis with extension to diaphysis and destruction of the anteromedial cortex (Fig. 1a, and b). Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a mass of malignant nature 7.6 cm × 7.15 cm × 7.7 cm in diameter and which causes more prominent expansion and destruction of the bone distally with periosteal reaction (Fig. 2a and b). Gadollinium-enhanced magnetic resonance images demonstrated peripheral contrast uptake. A lymphadenomegaly 16 mm × 13 mm in diameter was also present in the popliteal fossa having the same signal pattern with the primary lesion. Computerized tomography (CT) scanning of the thorax showed no lung metastasis.

Fig. 1.

(a and b) Pre-operative X-ray images demonstrate the lesion.

Fig. 2.

(a and b) Pre-operative MR images demonstrate the lesion and the arrows show the lymph node metastasis (sagittal T1–T2).

Technetium 99 whole body bone scan depicted only the proximal tibial mass and the lymph hode metastasis in a lateral view. The patient was evaluated by a whole crural MRI, including the knee and ankle joints, in order not to miss a skip metastasis. Approximately 12 cm long lesion of the cortex, reminding the beads of a rosary, without any cortical expansion in the mid-diaphyseal region was displayed. This lesion caused no periosteal reaction and had low contrast uptake. CT verification of the lesion was performed and it was associated with the callus formation due to the closed spiral fracture of the tibial shaft which was treated conservatively five years ago (Fig. 3a–c).

Fig. 3.

(a–c) Pre-operative CT images demonstrate the lesion.

Following tru-cut biopsy of the lesion and pathology reports being in compliance with osteoblastic osteosarcoma, three cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy was administered. The pain regressed after the first chemotherapy cycle. The popliteal lymph node had no involution and the main lesion had minimal regression when evaluated by preoperative MRI (Fig. 4). Thirteen weeks following the first referral of the patient, wide resection and reconstruction with modular tumor prosthesis was performed (Fig. 5). Popliteal artery and vein were explored. Anterior tibial artery and vein were sacrified as they were within the reactive zone of the tumor. Popliteal lymph node was excised through the same incision. Soft tissue coverage of the prosthesis and extansor aparatus reconstruction was achieved by a medial gastrocnemius rotation flap and split thickness skin graft (Fig. 6). Pathologic examination of the resected speciman reported osteoblastic osteosarcoma with a necrosis rate exceeding 90%. The lymph node extirpated from the popliteal fossa was 2 cm in diameter and was reported to be a metastasis of the primary tumor. Following wound healing, 3 cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy was applied (Fig. 7a and b).

Fig. 4.

MR image following neoadjuvant chemotherapy demonstrates the necrosis.

Fig. 5.

The photograph shows the resectate.

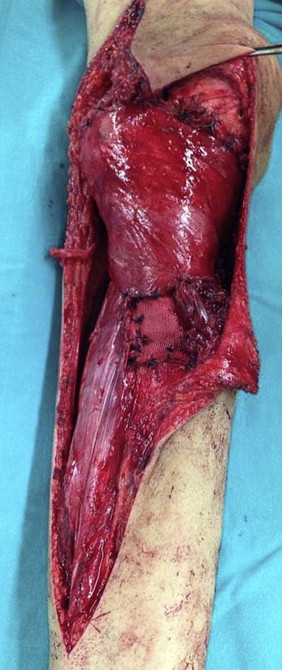

Fig. 6.

Peri-operative photograph shows the reconstruction using the medial head of gastrocnemius.

Fig. 7.

(a and b) Reconstruction with tumor prosthesis is seen on the post-operative X-ray images.

3. Discussion

Twenty to thirty percent of classic osteosarcoma patients have clinically apparent metastasis when first diagnosed.2,5,6 Most common metastasis are hematogeneous to the lungs and bones.1–3 Thorax CT for the lung metastasis and bone sintigraphy for the skeletal metastasis are advised but uncalcified lymph node metastasis might not be detected using Technetium-99 m methylene diphosphate scintigraphy.2,3,7 Gallium(Ga-67) scintigraphy is a better choice to detect the uncalcified lymph node metastasis.3 Positron emission tomography (PET) is another choice to evaluate the metastatic lesions.2 Lymphangiography can be used to identify an occult metastasis or to avoid local recurrence.8,9

Lymph node metastasis of osteosarcoma is a rare entity (<4%). Similar studies report rates between 2.3% and 4%.1–4,10–12 It is not clearly explained, how lymph node metastasis in osteosarcoma occurs despite lack of lymphatic drainage in normal cortical and spongious bone.2 The soft tissues like joint capsule or synovium, being in relation with upper layers of periosteum, have lymphtic vessels. In a study, J.R. Edwards et al. reported that tumors destructing cortex and penetrating soft tissue with lymph node metastasis contained lymphatic vessels. These lymphatics were limited in the cortex and did not enter medullary canal. In the same study, it was implied that the macromolecules could reach from medulla to periosteum through the gaps in the sinusoids of bones by fluid flow.4 In our case the tumor had destructed the cortex so it was thought that the popliteal lymph node metastasis could have been through lymphatics of joint synovium and capsule.

The initial tru-cut and trocar biopsy of the lesion reviewed a low grade osteosarcoma but the existence of a pathologic popliteal lymph node and periosteal reaction of the medial tibial cortex reminded of a high grade malignancy. A repeated open biopsy resulted with the diagnosis of a classic osteosarcoma.

Long-term survival rates have increased with patients who did not have metastasis upon first referral and treated with appropriate surgery and effective chemotherapy. The 5 year survival rate of osteosarcoma patients without metastasis is 50–80 but with the patients who had metastasis when first diagnosed, the 5 year survival rates are around 10–37%.1,2,6,13–18 The most important (negative) prognostic factor in osteosarcoma is occurrence of metastasis when first diagnosed. 20–30% of the patients have lung metastasis when diagnosed.2,14,15 The prognosis of the patients with solitary and surgically removable lesions are better according to patients who have multiple and/or unresectable lesions of the lungs.2 The most common sites for extrapulmonary metastasis are vertebras and pelvic bones. Extrapulmonary metastasis is more common below the level of diaphragma for lesions of femur. In contrast, extrapulmonary metastasis of the humeral lesions are more common above the diaphragma.9

Another significant prognostic factor is tumor necrosis ratio fallowing neoadjuvant chemothrapy. The pathologist calculates the ratio of necrotic cells within the resected tumor so that the effectiveness of the neoadjuvant chemotherapeutics can be determined. The ratio being over 90% like with our case is accepted as a positive prognostic factor.19–23

Prognosis is worse with bone metastasis while the effect of lymph node metastasis on prognosis is not exactly known.2 In a study 74 of 2748 (2.7%) patients with high grade osteosarcoma had lymph node metastasis when diagnosed and 19 of these were confirmed with pathologic studies. These patients were more likely to have extraskeletal tumors, distant metastases, tumors arising outside the lower extremity and larger tumors. This study also concluded that regional lymph node involvement is a significant prognostic factor independent of metastatic status, extraskeletal origin, age and tumor site.12

In conclusion, lymph node metastasis of osteosarcomas is a rare entity and metastatic patterns could not be clearly explained. On the other hand, the effects of lymph node metastasis on prognosis (of the patient) also are not clearly defined and further studies are needed.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from each patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Funding

Nothing to declare.

Ethical approval

Nothing to declare.

Authors’ contributions

All authors have been equally involved in the collection of data and drafting of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Yalın Dirik, Email: drdirik@gmail.com.

Arda Çınar, Email: arda.cinar@memorial.com.tr.

Feridun Yumrukçal, Email: feridun.yumrukcal@memorial.com.tr.

Levent Eralp, Email: drleventeralp@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Zwaga T., Bovée J.V., Kroon H.M. Osteosarcoma of the femur with skip, lymph node, and lung metastase. Radiographics. 2008;28(January–February (1)):277–283. doi: 10.1148/rg.281075015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hattori H., Yamamoto K. Lymph node metastasis of osteosarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(November (33)):e345–e349. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.3384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arkader A., Morris C.D. Lymphatic spread of pagetic osteogenic sarcoma detected by bone scan. Cancer Imaging. 2008;June (8):131–134. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2008.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards J.R., Williams K., Kindblom L.G., Meis-Kindblom J.M., Hogendoorn P.C., Hughes D. Lymphatics and bone. Hum Pathol. 2008;39(January (1)):49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adamkova D., Vesely K., Zambo I., Tucek S., Tomasek J., Jureckova A. Selingerova analysis of prognostic factors in osteosarcoma adult patients, a single institution experience. Klin Onkol. 2012;25(5):346–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rasalkar D.D., Chu W.C., Lee V., Paunipagar B.K., Cheng F.W., Li C.K. Pulmonary metastases in children with osteosarcoma: characteristics and impact on patient survival. Pediatr Radiol. 2011;41(February (2)):227–236. doi: 10.1007/s00247-010-1809-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heyman S. The lymphatic spread of osteosarcoma shown by Tc-99m-MDP scintigraphy. Clin Nucl Med. 1980;5(December (12)):543–545. doi: 10.1097/00003072-198012000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madsen E.H. Lymph node metastases from osteoblastic osteogenic sarcoma visible on plain films. Skeletal Radiol. 1979;4(4):216–218. doi: 10.1007/BF00347216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeffree G.M., Price C.H., Sissons H.A. The metastatic patterns of osteosarcoma. Br J Cancer. 1975;32(July (1)):87–107. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1975.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gulia A., Puri A., Jain S., Dhanda S., Gujral S. Indian chondrosarcoma of the bone with nodal metastasis: the first case report with review of literature. J Med Sci. 2011;65(August (8)):360–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.English R., Dicks-Mireaux C., Malone M., Scott R. Osteosarcoma – presumed lymph node metastases in two cases. Skeletal Radiol. 1989;18(4):289–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00361209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thampi S., Matthay K.K., Goldsby R., DuBois S.G. Adverse impact of regional lymph node involvement in osteosarcoma. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(November (16)):3471–3476. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y., Zhang L., Zhang G., Li S., Duan J., Cheng J. Osteosarcoma metastasis: prospective role of ezrin. Tumour Biol. 2014;35(March):5055–5059. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1799-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luetke A., Meyers P.A., Lewis I., Juergens H. Osteosarcoma treatment – where do we stand? A state of the art review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40(May (4)):523–532. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vijayamurugan N., Bakhshi S. Review of management issues in relapsed osteosarcoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2014;14(February (2)):151–161. doi: 10.1586/14737140.2014.863453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nathan S.S., Healey J.H. Demographic determinants of survival in osteosarcoma. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2012;41(September (9)):390–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Briccoli A., Rocca M., Salone M., Guzzardella G.A., Balladelli A., Bacci G. High grade osteosarcoma of the extremities metastatic to the lung: long-term results in 323 patients treated combining surgery and chemotherapy, 1985–2005. Surg Oncol. 2010;19(December (4)):193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mialou V., Philip T., Kalifa C., Perol D., Gentet J.C., Marec-Berard P. Metastatic osteosarcoma at diagnosis: prognostic factors and long-term outcome – the French pediatric experience. Cancer. 2005;104(September (5)):1100–1109. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miwa S., Takeuchi A., Shirai T., Taki J., Yamamoto N., Nishida H. Prognostic value of radiological response to chemotherapy in patients with osteosarcoma. PLOS ONE. 2013;8(July (7)):e70015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomez-Brouchet A., Bouvier C., Decouvelaere A.V., Larousserie F., Aubert S., Leroy X. Place of the pathologist in the management of primary bone tumors (osteosarcoma and Ewing's family tumors after neoadjuvant treatment) Ann Pathol. 2011;31(December (6)):455–465. doi: 10.1016/j.annpat.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hendershot E., Pappo A., Malkin D., Sung L. Tumor necrosis in pediatric osteosarcoma: impact of modern therapies. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2006;23(July–August (4)):176–181. doi: 10.1177/1043454206289786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bacci G., Ferrari S., Bertoni F., Picci P., Bacchini P., Longhi A. Histologic response of high-grade nonmetastatic osteosarcoma of the extremity to chemotherapy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;386(May):186–196. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200105000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bielack S.S., Kempf-Bielack B., Delling G., Exner G.U., Flege S., Helmke K. Prognostic factors in high-grade osteosarcoma of the extremities or trunk: an analysis of 1,702 patients treated on neoadjuvant cooperative osteosarcoma study group protocols. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(February (3)):776–790. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.3.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]