Abstract

Ribosomes are molecular machines that function in polyribosome complexes to translate genetic information, guide the synthesis of polypeptides, and modulate the folding of nascent proteins. Here, we report a surprising function for polyribosomes as a result of a systematic examination of the assembly of a large ribonucleoprotein complex, the vault particle. Structural and functional evidence points to a model of vault assembly whereby the polyribosome acts like a 3D nanoprinter to direct the ordered translation and assembly of the multi-subunit vault homopolymer, a process which we refer to as polyribosome templating. Structure-based mutagenesis and cell-free in vitro expression studies further demonstrated the critical importance of the polyribosome in vault assembly. Polyribosome templating prevents chaos by ensuring efficiency and order in the production of large homopolymeric protein structures in the crowded cellular environment and might explain the origin of many polyribosome-associated molecular assemblies inside the cell.

Keywords: vault particle, nanoprinting, polyribosome function, structure-based mutagenesis, cryo-electron tomography

Despite the detailed and broad knowledge that has been acquired about the structure and function of individual ribosomes, there is little information about the organization and function of the polyribosome. Fifty years ago, a model for eukaryotic polyribosome structure was described whereby ribosomes were sequentially aligned along a single mRNA strand moving from the 5′ to 3′ end as they produced the growing protein chain.1,2 Different routes have been proposed for the path by which the mRNA threads through the polyribosome including hairpins, spirals, and loops.3−5 Recent cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) analyses of free cytoplasmic polyribosomes indicate that the mRNA adopts pseudohelical and pseudoplanar paths with 5′ and 3′ ends spatially separated and with ribosome exit channels facing outward.6,7 This arrangement would maximize the distances between the growing peptides from neighboring ribosomes and prevent unfavorable aggregation.6,7 Here, we present evidence for a new function of the polyribosome where its spatial organization is critical for orchestrating favorable interactions between the growing peptide chains, leading to the assembly of large complexes. Discovery of this function, which we call polyribosome templating, arose during the study of vault assembly.

With a molecular mass of 13 MD and dimensions of ∼72 nm × 42 nm × 42 nm, vaults are among the largest ribonucleoprotein particles found in eukaryotic cells.8 Although no definitive function for vault particles has yet been determined, their evolutionary conservation and high abundance suggest that they are involved in one or more basic cellular activities.9 A single rat vault is composed of 78 copies of the 95.8 kDa major vault protein (MVP), tightly arranged to form the capsule-like shell of the particle.10 Each MVP chain is symmetrically arranged with its N-terminus at the waist of the particle and its C-terminus at the cap11,12 (see Figure 1A). Inside the shell are multiple copies of two additional proteins, vault poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (VPARP) and telomerase-associated protein (TEP1), and multiple copies of one or more small vault RNAs (vRNAs).9 Although insects do not have vaults, mammalian MVP expressed in insect cells assembles into vault particles. These recombinant vaults lack VPARP and TEP1 orthologs and the vRNA, yet they are structurally indistinguishable from native vaults.13 While vaults were discovered almost 30 years ago, their assembly has remained a mystery. Here, we have discovered how MVP chains assemble into the unique vault structure.

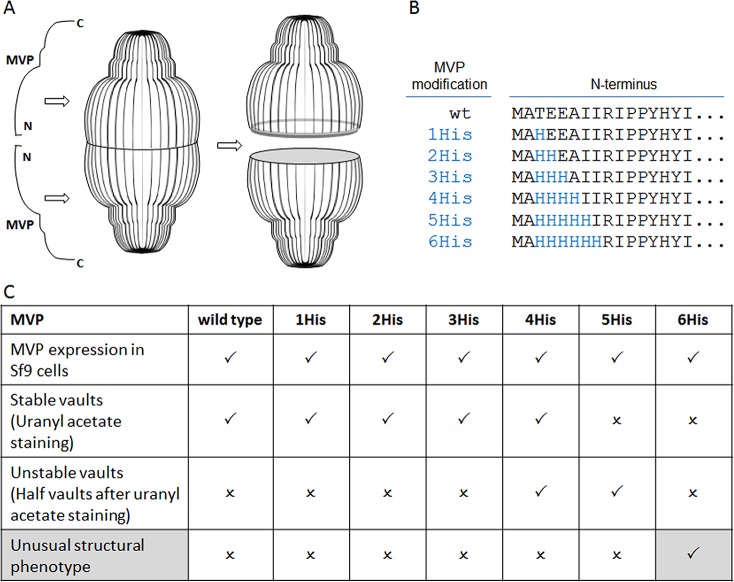

Figure 1.

Systematic mutagenesis of the vault structure. (A) Scheme of MVP configuration within the vault structure. (B) MVP N-terminal modifications. (C) Outcome of the structure-based mutagenesis: (check mark) = positive, (x) = negative.

Results

Capturing Assembly Intermediates of Vault Particles by Structure-Based Mutagenesis

With the intent of using recombinant vaults as nanoscale delivery vehicles,13−15 MVP was engineered to include peptide extensions. Such an engineering effort would benefit from a definitive understanding of how MVP assembles into vaults. MVPs modified with N-terminal tags (ranging from 11 to 238 amino acids) assembled into vaults, but how the extra and potentially flexible N-terminal peptides all ended up inside the particle at the waist was not fully understood.13

Therefore, we focused our attention on the natural N-terminus of MVP, as analysis of the vault 3.5 Å crystal structure revealed that the two identical halves are connected with each other at the waist via antiparallel β-sheet interactions that form between the first four N-terminal amino acids.10

An attempt was made to alter the interactions in this area by a series of histidine substitutions for amino acids at positions 3–8, expressing the constructs and analyzing the resulting protein products for vault assembly (Figure 1B,C). Substitution with one to three histidines (positions 3–5) did not alter the formation of vault particles. Substitution with four and five histidines (positions 3–7) generated unstable vault particles which appeared to separate into halves after assembly. Interestingly, substitution with six histidines (positions 3–8) completely disrupted vault assembly. Instead of individual vault particles (Figure 2A), unusual large structures were observed, predominantly staggered “rolls” (Figure 2B) and some “sheets” (Figure 2C) that appear to be rolls that became unraveled during the negative stain EM preparation. These large MVP rolls suggest that the 6-His-MVP mutant generates a structure that represents a vault assembly intermediate, rather than just a chaotically misassembled swirl of protein.

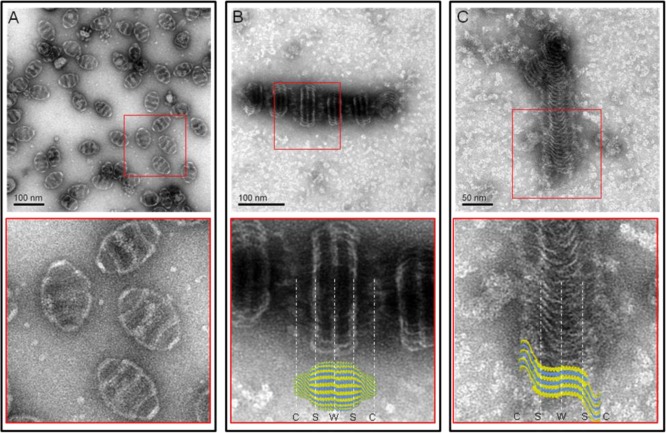

Figure 2.

Representative structures of the 6-His-MVP mutant. Electron micrographs of uranyl acetate stained supernatants of lysates from infected Sf9 cells. (A) Wild-type MVP vaults with a close-up view from its red inset. (B) Staggered rolls of MVP chains. Close-up view of the rolls aligned with a vault particle from the crystal structure.10 The vault cap (C), shoulder (S), and waist (W) regions are indicated by white dashed lines. (C) Long sheet of an unraveled MVP roll. Close-up view of the sheet superimposed with several individual MVP chains from the crystal structure.

Three prominent white bands are seen on each MVP roll (Figure 2B). The distances between these bands are remarkably similar to the distance from the vault waist to the shoulder region (shown in Figure 2B aligned with a vault particle based on the crystal structure),10 while the vault cap appears to be unstructured. The structures pictured in Figure 2C were interpreted as the inside of an unrolled sheet of MVP chains with their C-termini emanating from the sides of the sheet in a disordered manner (illustrated in Figure 2C with superimposed MVP chains).

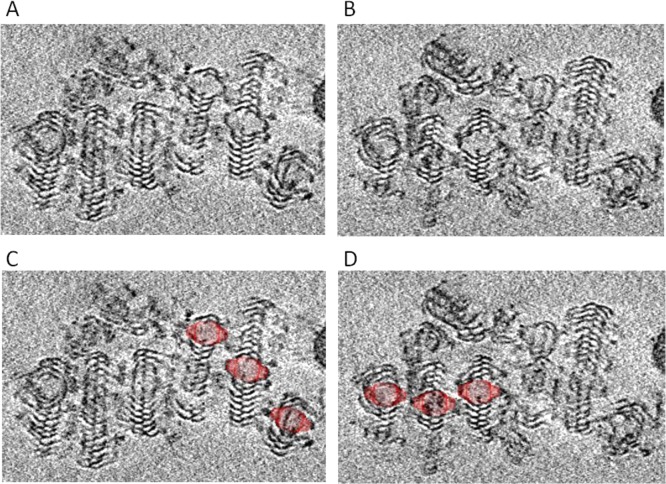

To confirm this observation, we further carried out cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) analysis of the vault assembly intermediate from the 6-His-MVP mutant (Figure 3). The 3D tomogram showed that each roll of 6-His-MVP was centered on a vault-like core structure (Figure 3C,D). The sheets that form from the 6-His-MVP mutation indicated that the sequence at the MVP N-terminus was essential for the vault maturation. Substitution of the natural amino acids of MVP at positions 3–8 with histidines prevented a vault particle from maturing and instead resulted in a continuously formed sheet of MVP polypeptide chains giving rise to the roll-like structures observed in the 6-His mutant (Figure 3 and Supporting Information movie S1).

Figure 3.

Cryo-electron tomography of 6-His-MVP mutant rolled structures. (A,B) Two frames from a cryo-ET cut series (Supporting Information movie S1) corresponding to different sample depths through a multiple 6-His-MVP roll. (C,D) Vault particle is superimposed over the center of each roll, shown at the same magnification.

Polyribosome Templating Model for Vault Assembly

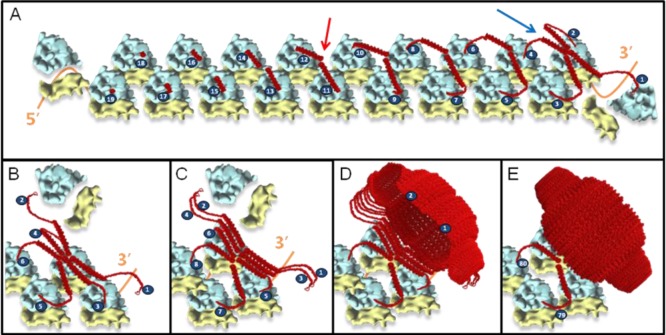

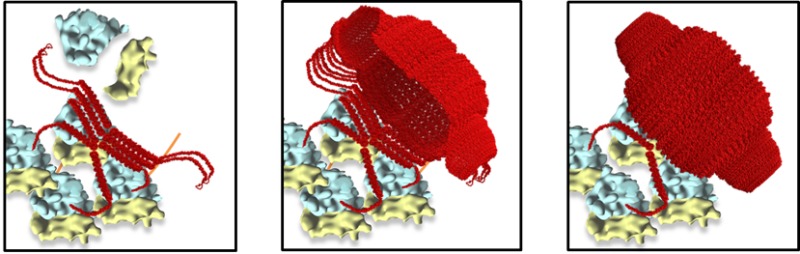

By combining the observed 6-His-MVP structural phenotype with recently described polyribosome geometry,6,7 a model of vault assembly was formulated as a co-translational process that is spatially constrained on a cytoplasmic polyribosome (Figure 4 and Supporting Information Figure S1 and movie S2 see: http://vaults.arc2.ucla.edu/MovieS2.htm).

Figure 4.

Model for vault assembly by polyribosome templating. (A) Schematic representation of a fully assembled polyribosome; as translation continues, MVP chains emerge (red); when two opposing MVP chains are long enough (red arrow), the N-termini interact to form a dimer; as translation of the MVP dimers nears completion, side-to-side interactions between neighboring MVP dimers begin to occur to give rise to an MVP tetramer (blue arrow). These side-to-side interactions of sequentially incoming MVP dimers begin to form a sheet (B,C), initiating the vault body to take its unique structure (D). Once 39 MVP dimers emerge, a pinch-off event occurs, leading to formation of an intact vault particle (E). All components of the model (MVP, vaults, and the 80S ribosome)10,16–18 were drawn to scale.

In this model, which we termed polyribosome templating, a single polyribosome acts like a cellular 3D nanoprinter. Progressively growing, neighboring MVPs interact with each other on a polyribosome with their N-termini to form a dimer. This MVP dimer then interacts with another adjacent MVP dimer via gradual side-to-side interactions to form an MVP tetramer. Successive addition of growing MVP dimers, layer-by-layer like in a 3D printing process, continues until the 78-mer of MVPs is reached and completes the entire vault structure at the 3′ end of a polyribosome.

The polyribosome templating model implies that (i) the local MVP monomer concentration on a polyribosome is a reflection of the polyribosome topology and is constant and hence does not depend on a critical cellular concentration of MVP monomers to generate a mature vault particle, as opposed to self-assembly; (ii) free MVP monomers should not exist at any given time as the polyribosome templating is a co-translational event; (iii) each vault is translated from the same copy of mRNA; and (iv) the observed roll-like structures of the 6-His-MVP mutant should be tethered to a polyribosome as they have lost their ability to pinch-off.

Experimental Evidence for Polyribosome Templating

In Vitro, Cell-Free Assembly

Self-assembly of vaults from individual subunits would require a critical concentration of MVP. However, vaults were detected by EM following in vitro translation of MVP mRNA under conditions where very low concentrations of MVP were synthesized (see Figure 5A). This result provides further evidence for the polyribosome templating model of vault assembly which predicts that a single MVP mRNA polyribosome should produce a vault even in a very dilute solution.

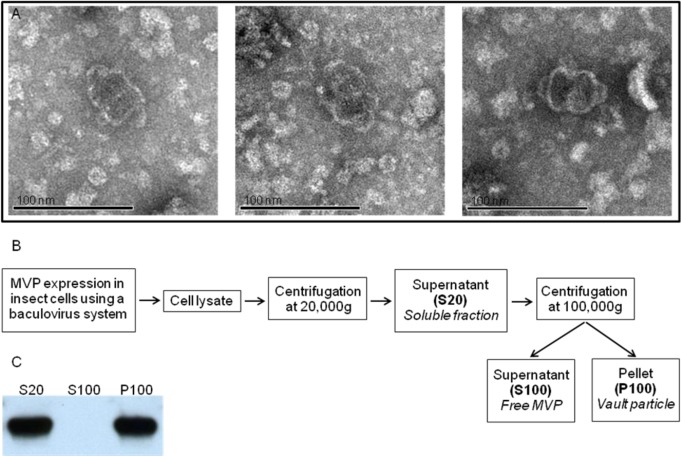

Figure 5.

Experimental evidence for polyribosome templating. (A) Electron micrograph of in vitro synthesized vaults. Samples were negatively stained with uranyl acetate. (B) Scheme of a differential centrifugation experiment. (C) Western blot analysis of S20, S100, and P100 fractions from the differential centrifugation.

All of the MVP Monomers Are Assembled into Vault Particles

To demonstrate that all of the MVPs are incorporated into the vault particles, we performed differential centrifugations (Figure 5B) of lysates from insect cells expressing MVP followed by Western blot analysis. As seen in Figure 5C, we could not detect any free MVP monomer.

Coexpression of Two Different MVP mRNAs

To test whether each assembled vault would be translated from the same copy of mRNA, we further performed coexpression experiments. Thus, if two different MVP mRNAs are present in the same cell, two different vault particles would be formed. To test this theory, mRNA coding for an MVP containing an N-terminal fusion with mCherry fluorescence protein (mCherry-MVP) and mRNA coding for a VSVG-tagged N-terminal MVP fusion (VSVG-MVP) were expressed in insect cells using a dual promoter expression system. When VSVG-MVP mRNA was expressed alone from a single promoter plasmid, stable vaults were formed (Figure 6A). In contrast, expression of the mCherry-MVP mRNA alone resulted in unstable vaults that rapidly dissociated into halves under conditions used for uranyl acetate staining (Figure 6B). Coexpression of the two different MVP mRNAs in the same cells using the dual promoter system revealed that, indeed, two types of vaults were formed (Figure 6C).

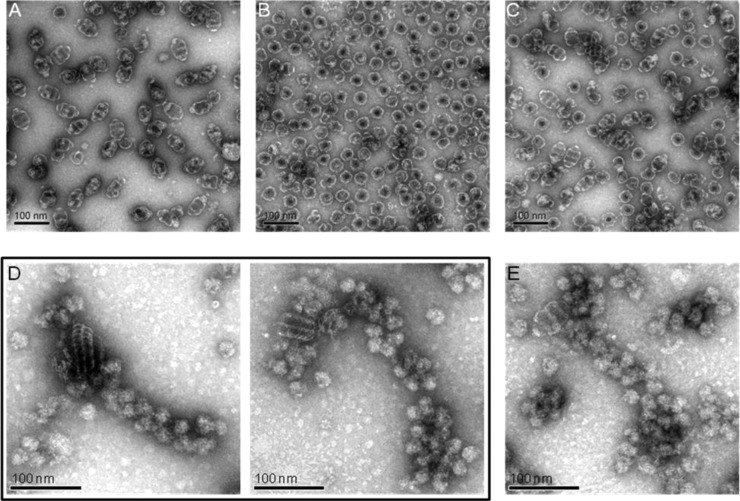

Figure 6.

Additional supportive evidence for polyribosome templating. (A–C) Coexpression of two different MVP mRNAs leads to two types of vaults. Electron micrograph of (A) VSVG-MVP full vaults expressed from a single promoter plasmid, (B) mCherry-MVP half vaults expressed from a single promoter plasmid, and (C) coexpression of mCherry/VSVG-MVP half and full vaults using a dual promoter plasmid. (D,E) Visible association of 6-His-MVP mutant structures with polyribosomes. Electron micrographs of purified polyribosomes from Sf9 cells expressing 6-His-MVP for 48 h (D) or MVP for 24 h (E). Samples were negatively stained with uranyl acetate. Scale bar 100 nm.

Association of Polyribosomes with 6-His-MVP Mutant

When polyribosomes were isolated from cells expressing the 6-His-MVP mutant at 48 h following infection, numerous bound MVP rolls were observed (Figure 6D). As expected, the rolls were considerably larger in diameter than those seen at 24 h.

We also isolated polyribosomes from Sf9 cells expressing an MVP lacking the 6-His substitution and found individual assembled vaults associated with polyribosomes (Figure 6E). The observation of a vault associated with a polyribosome was a less frequent event, as these vaults possess the native ability to pinch-off from the polyribosome upon their completion.

Discussion

The proposed polyribosome templating model explains previous assumptions that were inconsistent with self-assembly of individual free MVP chains into vault particles.13 A requirement for a polyribosome to form vaults predicts that reassembly from MVP monomers should not occur. Indeed, efforts to reassemble vaults from dissociated MVP monomers by urea and guanidine HCl treatment of purified vaults have failed even when gentle renaturation was attempted in the presence of cytoplasmic chaperones (data not shown). Polyribosome templating would allow 78 MVP monomers to form into a complex structure within the crowded cytoplasm environment despite an extremely low overall monomer concentration, as supported by the fact that vaults assemble in in vitro translations and that free MVP chains could not be detected in lysates of Sf9 cells during active vault synthesis.

An advantage of coupling the assembly of the vault complex to translation on a polyribosome is to guarantee an efficient ordered interaction of MVP chains into the stable macromolecular structure and to protect nascent MVPs from potential degradation and/or aggregation.

The sole conformation of the MVP monomer plays a determinant role in permitting co-translational assembly to occur. Each MVP monomer consists of nine structural repeat domains, a shoulder domain, a cap helix domain, and a cap ring domain.10 The structural repeat domains are expected to fold quickly and independently of each other during translation, a necessary prerequisite for co-translational assembly on a polyribosome. The shoulder domain brings the initially outward facing MVP chains together to form a dimer. Finally, the cap helix domain would impose favorable tension on vault assembly by tethering the incrementally built vault complex to the polyribosome.

The high evolutionary structural conservation and broad species distribution of vaults are a result of the prominent conservation of the unique MVP coding sequence. This high degree of MVP homology between different species might be a reflection of polyribosome templating, where polyribosome topology is conserved among species and is critical for vault assembly. This would also explain why vaults can be produced in eukaryotic organisms that naturally do not possess vaults (e.g., insects). The MVP itself in combination with the topology of a eukaryotic polyribosome is sufficient to form vaults.

The existence of the polyribosome has been known for 50 years, and it is generally accepted that most protein synthesis occurs on these structures.1,2 However, the only function which is implied from the structure of the polyribosome is the ability to increase the efficiency of protein production by a single mRNA. The ability to template the assembly of a macromolecular complex demonstrated here is a new function for the polyribosome, the significance of which could go far beyond vault assembly as other complexes, homopolymeric or heteropolymeric, might also utilize this ordered process. Certain homodimers (p53 and NF-kB)19,20 and cytoskeletal protein polymers (vimentin, myosin, and titin) are believed to assemble co-translationally.21 A nascent polypeptide could be directed by the polyribosome to participate in an ordered assembly with one or more completed protein chains. This would imply that certain multi-subunit complexes could require one or more subunits to be translated on a polyribosome to ensure proper assembly. Indeed, a recent study used ribonucleoprotein immunoprecipitation analyzed with DNA chips to examine 31 proteins with different functions and structures and found ∼38% co-purified with mRNAs that encode interacting proteins.22 The authors concluded that “co-translational formation of protein–protein interactions is a widespread phenomenon”.

Whether the multiple polyribosome topologies found in prokaryotes and eukaryotes6,7 are related to the polyribosome templating for assembling such multi-subunit complexes awaits further experimental demonstration. It was argued that the polyribosome topology limits internascent chain interactions to prevent unfavorable folding and aggregation,6 a scenario mainly for monomeric proteins. Conversely, our data shown here establish that polyribosome templating may direct and promote favorable protein interactions for homopolymeric protein complexes.

Conclusion

In a time in which efficient 3D manufacturing is predicted to have a revolutionary effect on mankind, nature unveils that it has already been using this technique for millions of years. Vaults are very large ribonucleoprotein particles found widely in eukaryotes. Our discovery of the unique assembly mechanism of the vault particle reveals an unforeseen function of the polyribosome as a very sophisticated cellular 3D nanoprinter. This role of the polyribosome as a molecular platform that is actively involved in the ordered translation of protein complexes may provide new avenues toward the understanding of the implication of protein aggregation in a vast number of pathologies such as Alzheimer’s disease. Elucidating the involvement of the polyribosome in inappropriate protein aggregation could uncover it as a novel translational target for therapies.

Materials and Methods

Recombinant MVP

The rat MVP N-terminus was systematically modified by substitution with histidines at residues 3–8 by PCR. To produce recombinant vaults, a baculovirus system (Invitrogen) was used to infect insect Sf9 cells as previously described.23 Infected Sf9 cells were then lysed in buffer A (50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 75 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM MgCl2) supplemented with 1% Triton X-100 plus RNase A (0.1–0.2 μg/mL final concentration), incubated on ice for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 20 000g at 4 °C for 20 min. The clarified supernatant (S20) was collected, and recombinant vaults were visualized by electron microscopy.

Preparation of Polyribosomes

Sf9 cells infected with either 6-His-MVP or wild-type MVP baculoviruses were harvested 24 and 48 h post-infection. Cells were lysed on ice for 5 min in buffer containing 15 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 1% Triton-X-100. Cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 10 000g for 5 min at 4 °C. Clarified cell lysates were overlaid onto sucrose step gradients (20, 30, 40, 45, 50, and 60%) and centrifuged at 25 000g for 2.5 h at 4 °C (Beckman SW41 rotor). The 45% sucrose fraction was collected and designated the polyribosome fraction.

Electron Microscopy

Samples were assessed by EM using negative staining with 1% aqueous uranyl acetate as previously described.24 Grids were examined on a JEM1200EX (JEOL) electron microscope, and micrographs were captured with a BioScan 600 W digital camera (Gatan).

Cryo-Electron Tomography and Image Processing

Cryo samples were prepared by placing a small drop (∼4 μL) of sample solution onto a glow discharged holey carbon mesh (Quantifoil 200 mesh grid with 3.5 μm holes spaced 1 μm apart). The grids were blotted and plunged immediately into liquid-nitrogen-cooled liquid ethane to rapidly freeze the samples in vitrified ice. The cryo samples were visualized with an FEI Titan Krios transmission electron microscope with an accelerating voltage of 300 kV. The samples were imaged at 50 000× to 100 000× with an underfocus value of 3 μm at 0° tilt, utilizing an energy filter. Tomography tilt series were taken using the FEI batch tomography software to set up and automatically acquire sample images with a tilt range from −70 to +70°. The tilt series were recorded on an Ultrascan 4 megapixel CCD camera (Gatan). Alignment of the tilt series was performed using the etomo tomography processing software from the Imod package. The steps included X-ray removal, rough alignment by cross-correlation, and fine alignment by fiducial gold tracking. The aligned tilt series were then used to make a 3D reconstruction using GPU-based SIRT (simultaneous iterative reconstruction technique) reconstruction implemented in Inspect3D. The 3D reconstructions were saved as a stack of X–Y plane images that are single pixel slices along the Z plane. Slices from the reconstructions were displayed using the slicer within 3dmod from the Imod package.

In Vitro Translation of MVP mRNA

In vitro translation was carried out using an insect-based cell-free system (EasyXpress Insect Kit II, Qiagen), using the protocol described by the manufacturer. In vitro synthesized recombinant vaults were further treated with RNase A and purified over 20% sucrose cushion (centrifuged at 100 000g for 2 h at 4 °C in Beckman Coulter Ti 70.1 rotor). Pellets were then dissolved in buffer A and visualized by EM.

Differential Centrifugation and Western Blot Analysis

Infected Sf9 cells were lysed as described above and centrifuged at 20 000g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant, referred to as S20, was diluted in 7.5 mL of buffer A and subsequently centrifuged at 100 000g for 1 h at 4 °C after reserving 5 μL for future electrophoretic analysis. The obtained pellet and supernantant, referred to as P100 and S100, respectively, were then diluted in 7.5 mL buffer A each, and 5 μL of each fraction was subjected to electrophoresis.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoretic (SDS–PAGE) analysis was carried out on minigels (4–12% acrylamide, Bio-Rad). Separated proteins were transferred to Hybond-C nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare) for 1 h, by means of a Mini-PROTEAN II cell apparatus (Bio-Rad) and incubated in TTBS (50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1% Tween-20, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5), containing 5% nonfat dry milk for 1 h. Samples were then incubated overnight in TTBS/3% nonfat dry milk, containing the primary antibody (MVP polyclonal rabbit, 1:2000). After several washes in TTBS, the membrane was incubated in TTBS/5% nonfat dry milk containing goat anti-rabbit antibody coupled to horseradish peroxidase (1:2000; Bio-Rad) for 2 h. After several washes in TTBS, immunoreactive bands were visualized by using an enhanced chemiluminescence Western blotting detection kit (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The membrane was then immediately exposed to Fuji medical X-ray film Rx-U in a film cassette at room temperature.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank David S. Goodsell for his drawing of the polyribosome templating illustration (Figure S1). The animation (movie S2) was produced by Jacob Dotson. We thank Daniel H. Anderson, Gayle M. Boxx, Daniel Buhler, Alison Frand, Feng Guo, Nancy L. Kedersha, Michael E. Rome, and Todd Yeates for reading the manuscript. This research was supported in part by grants from the Jonnson Comprehensive Cancer Center at UCLA, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences UCLA CTSI Grant UL1TR000124, and NIH Grant R01GM071940 (to H.Z.). The authors acknowledge the use of instruments at the Electron Imaging Center for NanoMachines supported by NIH (1S10RR23057) and CNSI at UCLA.

Supporting Information Available

Additional figure and movies. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Warner J. R.; Knopf P. M.; Rich A. A Multiple Ribosomal Structure in Protein Synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1963, 49, 122–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner J. R.; Rich A.; Hall C. E. Electron Microscope Studies of Ribosomal Clusters Synthesizing Hemoglobin. Science 1962, 138, 1399–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin K. A.; Miller O. L. Jr. Polysome Structure in Sea Urchin Eggs and Embryos: An Electron Microscopic Analysis. Dev. Biol. 1983, 98, 338–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen A. K.; Bourne C. M. Shape of Large Bound Polysomes in Cultured Fibroblasts and Thyroid Epithelial Cells. Anat. Rec. 1999, 255, 116–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopeina G. S.; Afonina Z. A.; Gromova K. V.; Shirokov V. A.; Vasiliev V. D.; Spirin A. S. Step-Wise Formation of Eukaryotic Double-Row Polyribosomes and Circular Translation of Polysomal mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 2476–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt F.; Etchells S. A.; Ortiz J. O.; Elcock A. H.; Hartl F. U.; Baumeister W. The Native 3D Organization of Bacterial Polysomes. Cell 2009, 136, 261–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt F.; Carlson L. A.; Hartl F. U.; Baumeister W.; Grunewald K. The Three-Dimensional Organization of Polyribosomes in Intact Human Cells. Mol. Cell 2010, 39, 560–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedersha N. L.; Rome L. H. Isolation and Characterization of a Novel Ribonucleoprotein Particle: Large Structures Contain a Single Species of Small Rna. J. Cell Biol. 1986, 103, 699–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger W.; Steiner E.; Grusch M.; Elbling L.; Micksche M. Vaults and the Major Vault Protein: Novel Roles in Signal Pathway Regulation and Immunity. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009, 66, 43–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H.; Kato K.; Yamashita E.; Sumizawa T.; Zhou Y.; Yao M.; Iwasaki K.; Yoshimura M.; Tsukihara T. The Structure of Rat Liver Vault at 3.5 Angstrom Resolution. Science 2009, 323, 384–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikyas Y.; Makabi M.; Raval-Fernandes S.; Harrington L.; Kickhoefer V. A.; Rome L. H.; Stewart P. L. Cryoelectron Microscopy Imaging of Recombinant and Tissue Derived Vaults: Localization of the MVP N Termini and VPARP. J. Mol. Biol. 2004, 344, 91–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson D. H.; Kickhoefer V. A.; Sievers S. A.; Rome L. H.; Eisenberg D. Draft Crystal Structure of the Vault Shell at 9-Å Resolution. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5, e318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rome L. H.; Kickhoefer V. A. Development of the Vault Particle as a Platform Technology. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 889–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M.; Kickhoefer V. A.; Nemerow G. R.; Rome L. H. Targeted Vault Nanoparticles Engineered with an Endosomolytic Peptide Deliver Biomolecules to the Cytoplasm. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 6128–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buehler D. C.; Marsden M. D.; Shen S.; Toso D. B.; Wu X.; Loo J. A.; Zhou Z. H.; Kickhoefer V. A.; Wender P. A.; Zack J. A.; Rome L. H. Bioengineered Vaults: Self-Assembling Protein Shell-Lipophilic Core Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 7723–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen E. F.; Goddard T. D.; Huang C. C.; Couch G. S.; Greenblatt D. M.; Meng E. C.; Ferrin T. E. UCSF Chimera—A Visualization System for Exploratory Research and Analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandramouli P.; Topf M.; Menetret J. F.; Eswar N.; Cannone J. J.; Gutell R. R.; Sali A.; Akey C. W. Structure of the Mammalian 80s Ribosome at 8.7 Å Resolution. Structure 2008, 16, 535–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer S.; Brandt F.; Hrabe T.; Lang S.; Eibauer M.; Zimmermann R.; Forster F. Structure and 3D Arrangement of Endoplasmic Reticulum Membrane-Associated Ribosomes. Structure 2012, 20, 1508–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls C. D.; McLure K. G.; Shields M. A.; Lee P. W. Biogenesis of P53 Involves Cotranslational Dimerization of Monomers and Posttranslational Dimerization of Dimers. Implications on the Dominant Negative Effect. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 12937–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L.; DeMartino G. N.; Greene W. C. Cotranslational Dimerization of the Rel Homology Domain of Nf-κb1 Generates P50-P105 Heterodimers and Is Required for Effective P50 Production. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 4712–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton A. B.; L’Ecuyer T. Cotranslational Assembly of Some Cytoskeletal Proteins: Implications and Prospects. J. Cell Sci. 1993, 105, 867–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan C. D.; Mata J. Widespread Cotranslational Formation of Protein Complexes. PLoS Gen. 2011, 7, e1002398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephen A. G.; Raval-Fernandes S.; Huynh T.; Torres M.; Kickhoefer V. A.; Rome L. H. Assembly of Vault-like Particles in Insect Cells Expressing Only the Major Vault Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 23217–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poderycki M. J.; Kickhoefer V. A.; Kaddis C. S.; Raval-Fernandes S.; Johansson E.; Zink J. I.; Loo J. A.; Rome L. H. The Vault Exterior Shell Is a Dynamic Structure That Allows Incorporation of Vault-Associated Proteins into Its Interior. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 12184–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.