Abstract

Aims: Mitochondrion is considered as the major source of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS). H2S has been reported to be an antioxidant, but its mechanism remains largely elusive. P66Shc is an upstream activator of mitochondrial redox signaling. The aim of this study was to explore whether the antioxidant effect of H2S is mediated by p66Shc. Results: Application of exogenous H2S with its donor, NaHS, or overexpression of its generating enzyme, cystathionine β-synthase, induced sulfhydration of p66Shc, but inhibited its phosphorylation caused by H2O2/D-galactose in SH-SY5Y cells or in the mice cortex. H2S also decreased mitochondrial ROS production and protected neuronal cells against stress-induced senescence. PKCβII and PP2A are the two key proteins to regulate p66Shc phosphorylation. Although H2S failed to affect the activities of these two proteins, it disrupted their association. Cysteine-59 resides in proximity to serine-36, the phosphorylation site of p66Shc. The C59S mutant attenuated the above-described biological function of H2S. Innovation: We revealed a novel mechanism for the antioxidant effect of H2S and its role in oxidative stress-related diseases. Conclusion: H2S inhibits mitochondrial ROS production via the sulfhydration of Cys-59 residue, which in turn, prevents the phosphorylation of p66Shc. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 21, 2531–2542.

Introduction

P66Shc, together with p52Shc and p46Shc, belongs to the ShcA family whose members share three common functionally identical domains: the C-terminal Src homology 2 domain (SH2), the central collagen homology domain (CH1), and the N-terminal phosphotyrosine-binding domain (PTB) (22). Different from the other two isoforms, p66Shc shows a negative influence on the Ras-mediated signaling pathway (26). P66Shc was demonstrated to be involved in intracellular redox balance. In response to oxidative stress (UV exposure or H2O2 treatment), p66Shc is activated through protein kinase C-βII (PKCβII)-mediated phosphorylation at Ser-36. The activated p66Shc is finally dephosphorylated and translocates to mitochondria, where it binds to cytochrome c and transfers electrons from cytochrome c to molecular oxygen (7, 24). There was a 30% increase in the lifespan of p66Shc−/− mice (17). Furthermore, macrophages from p66Shc−/− mice appeared to be a defect in the activation of the NADPH oxidase and, therefore, less superoxide production was observed (33). All these findings suggest a crucial role for p66Shc in the oxidative challenge.

H2S is now recognized as the third gasotransmitter along with nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide. It is generated by cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3-MST). CBS is primarily expressed in various regions of the brain and is essential to the production of H2S in the central nervous system (1). We proved that H2S exerted a wide range of biological functions, including neuroprotection (8, 14), cardioprotection (20, 21), antihypertension (13), and osteoblastic protection (37). Most of these functions are attributed to its antioxidant effects. This antioxidant effect of H2S has also been proved in a wide array of cells and tissues (16, 25). The mechanisms include suppression of membrane oxidase activity [e.g., NADPH oxidase (37) and glutathione peroxidase (12)], inhibition of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and stimulation of synthesis of ROS scavengers [e.g., superoxide dismutase (11) and glutathione (9)]. Recently, we demonstrated that H2S protected dopaminergic neurons against degeneration in a mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2-mediated antioxidative mechanism (14), indicating a direct effect of H2S on mitochondrial oxidative stress formation. However, the exact action site of H2S and its molecular mechanisms is still in need of further exploration.

Innovation.

We demonstrated for the first time that H2S may inhibit mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production via a p66Shc-dependent mechanism. H2S sulfhydrated p66Shc at cysteine-59, which resides in proximity to the phosphorylation site serine-36. Sulfhydration of p66Shc further impaired the association of PKCβII and p66Shc and attenuated H2O2-induced p66Shc phosphorylation, a critical step in p66Shc-mediated mitochondrial ROS generation. This was further confirmed in vivo in the D-galactose-induced aging model. Thus, we revealed in the present study, a novel mechanism for the antioxidant effect of H2S and its role in oxidative stress-related diseases.

An emerging aspect of H2S signaling is the pathway mediated by protein sulfhydration. This H2S-induced posttranslational modification has been confirmed to regulate the function of a large number of proteins, such as the potassium channels (like KATP, IKca, and SKca) (19), PTP1B (10), NF-κB (27), and Keap1 (38). It was believed that the conserved cysteine residue at the key point holds the key (23) to the sulfhydration.

Structure analysis revealed that p66Shc also contains a unique conserved cysteine residue, which locates at position 59 (Cys-59) in the CH2 domain (5). We thereby hypothesized that the conserved Cys-59 was also subject to S-sulfhydration by H2S and this modification would provide a mechanism for the regulation of H2S on p66Shc function. The study presented here was designed to examine the effect of H2S on p66Shc and its role in mitochondrial ROS production.

Results

H2S alleviates H2O2-induced mitochondrial ROS production in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells

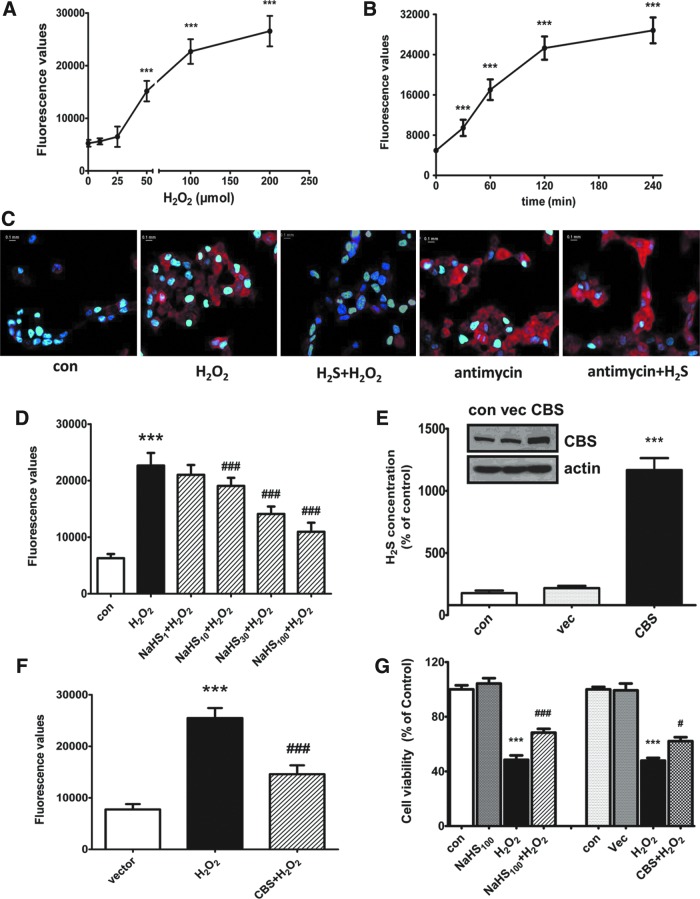

The first step of our experiments is to confirm the effect of H2O2 on mitochondrial oxidative stress. We measured the mitochondrial ROS generation using a selective fluorescence indicator, MitoSOX™ Red mitochondrial superoxide indicator (Molecular Probes). As shown in Figure 1A, treatment of SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells with different concentrations of H2O2 (0–200 μM) for a 60-min concentration dependently increased the ROS level. The time course study showed that treatment with H2O2 at 50 μM increased the mitochondrial ROS level in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). In contrast, pretreatment with NaHS (an H2S donor, 100 μM) for 30 min inhibited H2O2 (50 μM, 2 h)-induced mitochondrial ROS generation (Fig. 1C). The concentration-dependent response is shown in Figure 1D. Antimycin is an inhibitor of mitochondrial electron transport chain via direct binding to mitochondrial complex III. Interestingly, NaHS failed to affect antimycin (10 μM, 1 h)-induced mitochondrial ROS production (Fig. 1C). To characterize the effect of endogenous H2S on mitochondrial oxidative stress, we transfected the CBS gene into SH-SY5Y cells. As shown in Figure 1E and F, overexpression of CBS caused a large increase in both the protein level of CBS and H2S production (Fig. 1E) and a significant inhibition on H2O2-induced mitochondrial oxidative stress (Fig. 1F). In addition, both NaHS and CBS overexpression protected cells against H2O2-induced cell injury (Fig. 1G).

FIG. 1.

Effect of endogenous and exogenous H2S on H2O2-induced mitochondrial ROS generation and cell viability in SH-SY5Y cells. Concentration- (A) and time- (B) dependent responses of H2O2-induced mitochondrial ROS generation. (C) Representative images showing that NaHS pretreatment decreased mitochondrial ROS production caused by H2O2, but not that caused by antimycin. (D) Pretreatment with NaHS concentration dependently decreased H2O2-induced mitochondrial ROS production. Cells were pretreated with different concentrations of NaHS for 30 min followed by treatment with H2O2 (50 μM, 2h) or antimycin (10 μM, 1 h). (E) CBS overexpression and its effect on H2S synthesis. (F) CBS overexpression decreased H2O2-induced mitochondrial ROS production. (G) NaHS pretreatment and CBS overexpression attenuated H2O2-induced cell death. Cells were transfected with pME18S-CBS-HA cDNAs or its empty vector for 48 h before the experiments. Data are expressed as mean±SEM, n=8, ***p<0.001 versus control/vector, #p<0.05, ###p<0.001 versus H2O2 group. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

H2S inhibits H2O2-induced p66Shc phosphorylation in SH-SY5Y cells

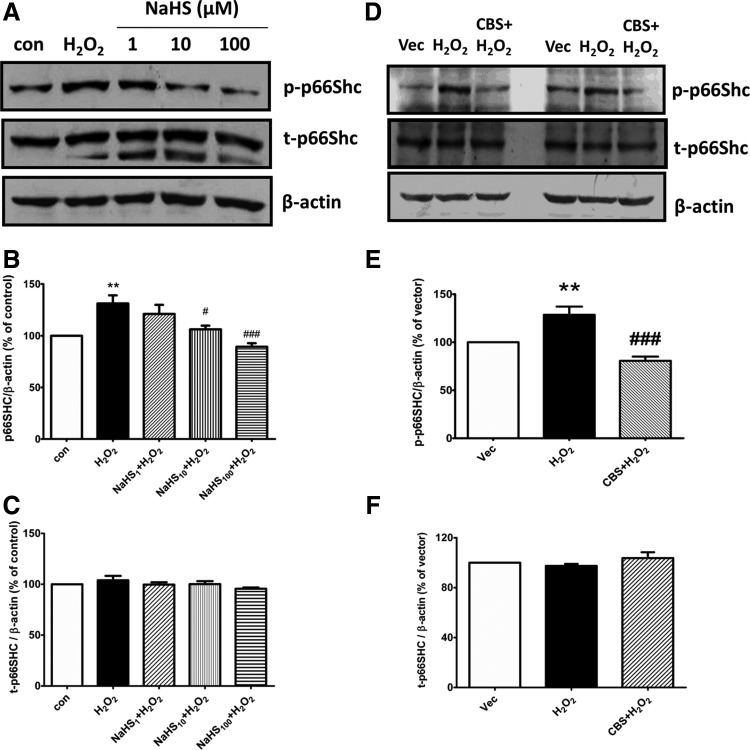

P66Shc is recognized as a general regulator on mitochondrial ROS formation. The critical step for p66Shc activation is the phosphorylation of serine residue (Ser-36) in CH2 domain (24). We therefore continued to test the effect of H2S on p66Shc phosphorylation. Treatment with 50 μM H2O2 for 20 min significantly increased the level of p66Shc Ser-36 phosphorylation. This effect was concentration dependently reversed by exogenous application of NaHS (1–100 μM, Fig. 2A, B) or stimulation of endogenous H2S production by overexpression of CBS (Fig. 2D, E). No significant change was found in the expression of total p66Shc protein among different treatment groups (Fig. 2C, F).

FIG. 2.

Effect of H2S on H2O2-induced p66Shc phosphorylation in SH-SY5Y cells. Representative images (A) and densitometric analysis (B–C) of Western blots showing that pretreatment with NaHS concentration dependently decreased H2O2-induced p66Shc phosphorylation without affecting the total protein expression of p66Shc. Cells were pretreated with different concentrations of NaHS (1–100 μM) for 30 min followed by H2O2 (50 μM) treatment for another 20 min. (D–F) Representative images (D) and densitometric analysis (E–F) of Western blots showing that CBS overexpression inhibited H2O2-induced p66Shc phosphorylation without affecting the total protein expression of p66Shc. Cells were transfected with pME18S-CBS-HA cDNAs or its empty vector for 48 h before the experiments. The values are presented as mean±SEM from five to eight independent experiments, **p<0.01 versus control group, #p<0.05, ###p<0.001 versus H2O2 treatment group.

H2S-induced p66Shc sulfhydration at cysteine-59 mediates its inhibitory effects on p66Shc phosphorylation and oxidative stress

Different from the other two ShcA members, p66Shc has an additional N-terminal collagen homology domain (CH2), which contains a single cysteine at position 59 (Cys-59) (5). Our results showed that NaHS at 1–100 μM induced p66Shc sulfhydration in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 3A). This effect was almost completely abolished by 2 mM idoacetamine, a sulfhydryl-reactive alkylating reagent, which binds covalently with the thiol group in the cysteine residues to prevent disulfide bond formation (Fig. 3A). The similar effect was also observed in CBS overexpressed SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

H2S-induced p66Shc sulfhydration at cysteine-59 and its effects on mitochondrial ROS generation. (A) NaHS concentration dependently induced p66Shc sulfhydration in SH-SY5Y cells. This was largely abolished by idoacetamine (IA), a sulfhydryl-reactive alkylating reagent. (B) CBS overexpression promoted p66Shc sulfhydration. (C) Highly conserved serine (Ser-36) and cysteine (Cys-59) residues in CH2 domain (aa 1–100) of p66Shc. (D) C59S reduced H2S-induced p66Shc sulfhydration in HEK293 cells. Cells were transfected with either pcDNA3-p66Shc (WT-HEK) or pcDNA3-p66Shc-C59S cDNAs (C59S-HEK). (E–F) C59S eliminated the inhibitory effect of H2S on H2O2-induced p66Shc phosphorylation (E) and mitochondrial ROS generation (F). (G) C59S abolished the protective effect of NaHS on cell viability in response to hydrogen peroxide. The values are presented as mean±SEM. n=4–8. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 versus control group, ###p<0.001 versus H2O2 group. ‡p<0.05 versus NaHS100 group. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

To identify the sulfhydrated cysteine residue of p66Shc, the conserved cysteine-59 was mutated to serine (C59S) (Fig. 3C). It was found that the Cys-59 mutation markedly attenuated the sulfhydration of p66Shc induced by NaHS (Fig. 3D), suggesting the critical role of Cys-59 in H2S-induced p66Shc sulfhydration. Meanwhile, the C59S mutation also significantly eliminated the inhibitory effect of H2S on H2O2-induced p66Shc phosphorylation (Fig. 3E). These data showed that H2S-induced sulfhydration contributes to its inhibitory effect on p66Shc phosphorylation.

To link the Cys-59 sulfhydration of p66Shc to its function on mitochondrial oxidative stress, we thereby examined the effect of H2S on mitochondrial ROS generation in HEK293 cells transfected with the C59S mutant. As shown in Figure 3F, the ROS level in the NaHS pretreatment group was only about 67% of that of H2O2-treated HEK293 cells transfected with WT p66Shc. However, this inhibitory effect of NaHS was not observed in HEK293 cells transfected with the C59S mutant. In addition, the C59S mutation also abolished the protective effect of NaHS on cell viability (Fig. 3G).

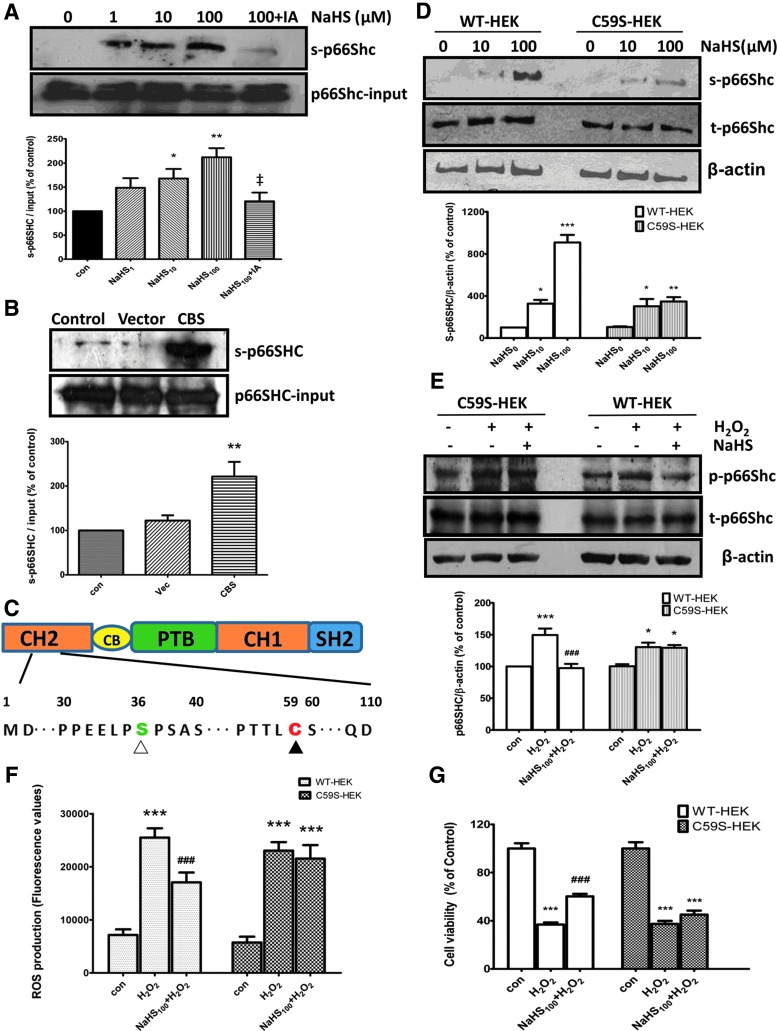

H2S inhibits the association between PKCβII and p66Shc without affecting their activities

Both PKCβII and PP2A were reported to regulate the p66Shc activity (24). We next explored the effect of H2S on the activities of PKCβII and PP2A in SH-SY5Y cells. Our results showed that no significant difference was observed among different treatment groups in either PP2A protein expression (Fig. 4A) or its activity (Fig. 4B). This result is consistent with previous studies, in which PP2A was found to be resistant to oxidants (2, 30). In addition, NaHS did not affect H2O2-induced translocation of PKCβII from cytosol to particulate membrane (Fig. 4C), the hallmark for PKCβII activation (3).

FIG. 4.

Effects of H2S on activities of PP2A and PKCβII and their interaction. (A, B) NaHS had no significant effect on the protein expression (A) and activity (B) of PP2A. SH-SY5Y cells were pretreated with different concentrations of NaHS (1–100 μM) for 30 min followed by 50 μM H2O2 for another 30 min. (C) NaHS at 1–100 μM had no significant effect on H2O2-promoted translocation of PKCβII. (D) Treatment with H2O2 (50 μM) for 30 min increased the association between PKCβII and p66Shc, which was inhibited by pretreatment with NaHS (100 μM). (E) C59S resumed the association between PKCβII and p66Shc in HEK293 cells. Cells were transfected with either pcDNA3-p66Shc (WT-HEK) or pcDNA3-p66Shc-C59S cDNAs (C59S-HEK). The values are presented as mean±SEM from four to six independent experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 versus control group, ##p<0.01, ###p<0.001 versus H2O2-treated group.

On the contrary, coimmunoprecipitation assay showed that NaHS treatment significantly reduced the interaction between PKCβII and p66Shc in HEK293 cells treated with H2O2 (Fig. 4D). However, this effect was eliminated when Cys-59 of p66Shc mutated to serine (Fig. 4E), suggesting a key role of Cys-59 in PKCβII-mediated p66Shc phosphorylation.

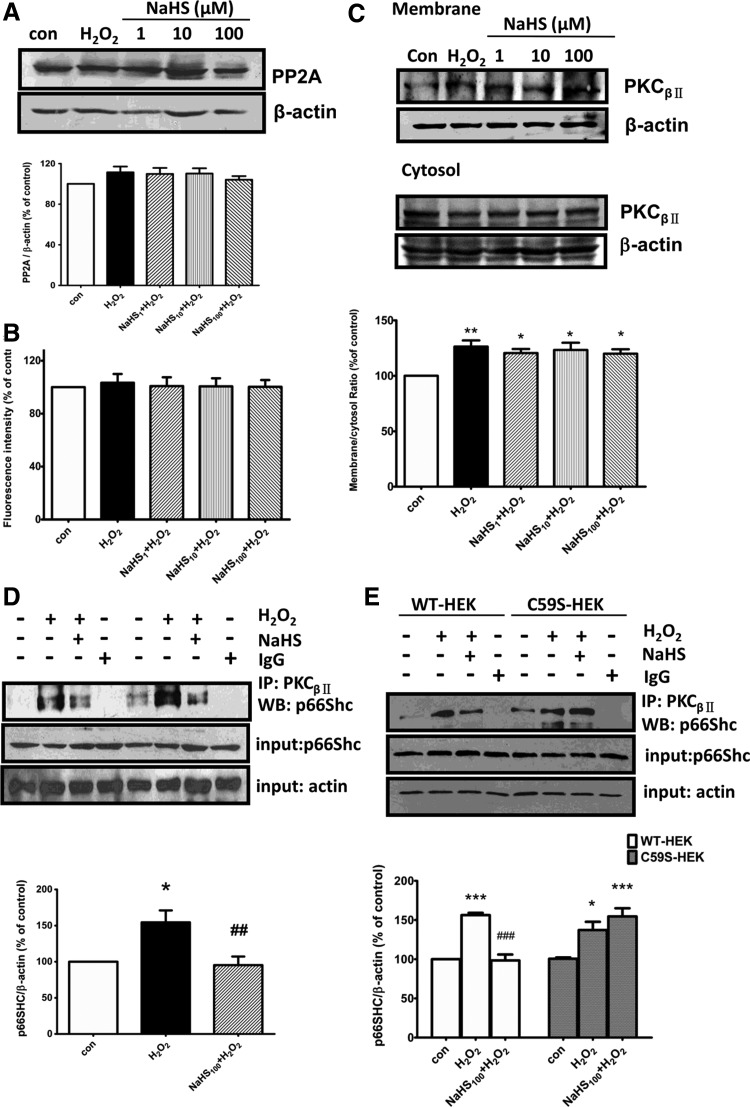

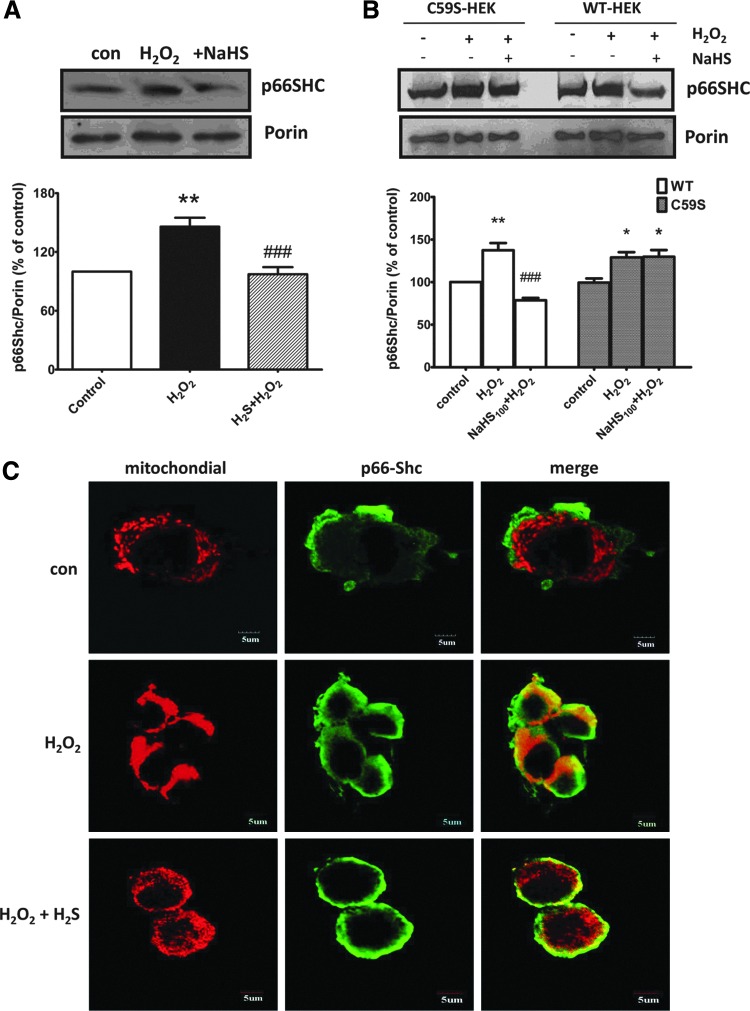

H2S reduces p66Shc translocation to mitochondria

It was believed that p66Shc finally translocated to the mitochondria where it participated in ROS production. We therefore evaluated the mitochondrial pool of p66Shc. In normal SH-SY5Y cells, H2O2 treatment increased the amount of p66Shc within mitochondria about 45.9%. In contrast, the expressions of p66Shc were less pronounced in mitochondria isolated from cells pretreated with 100 μM NaHS for 30 min (Fig. 5A). A similar effect was also found in HEK293 cells transfected with WT p66Shc. However, no detectable changes were observed in cells transfected with C59S mutants (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Effect of H2S on H2O2-induced mitochondrial translocation of p66Shc. (A) Representative images and densitometric analysis of Western blots showing that pretreatment with NaHS inhibited H2O2-induced mitochondrial translocation of p66Shc in SH-SY5Y cells. (B) C59S abolished the effect of NaHS on H2O2-induced mitochondrial translocaton of p66Shc in HEK293 cells, which were transfected with pcDNA3-p66Shc (WT-HEK) or pcDNA3-p66Shc-C59S cDNAs (C59S-HEK). Porin was used as a loading control of mitochondrial protein. (C) Representative confocal images showing that NaHS pretreatment attenuated H2O2-induced colocalization of p66Shc with mitochondria in SH-SY5Y cells. Cells were pretreated with NaHS (100 μM, 30 min) followed by H2O2 (50 μM) treatment for another 30 min. The values are presented as mean±SEM from three to five independent experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 versus control group, ###p<0.001 versus H2O2-treated group. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

This was further confirmed by immunofluorescence assay. Confocal microscopy confirmed a clear preferential colocalization between p66Shc and mitochondria upon treatment with H2O2 (50 μM) for 30 min and this effect was abolished by NaHS pretreatment (Fig. 5C). Our data suggest that H2S may prevent the translocation of p66Shc to the mitochondria and its contribution to ROS generation.

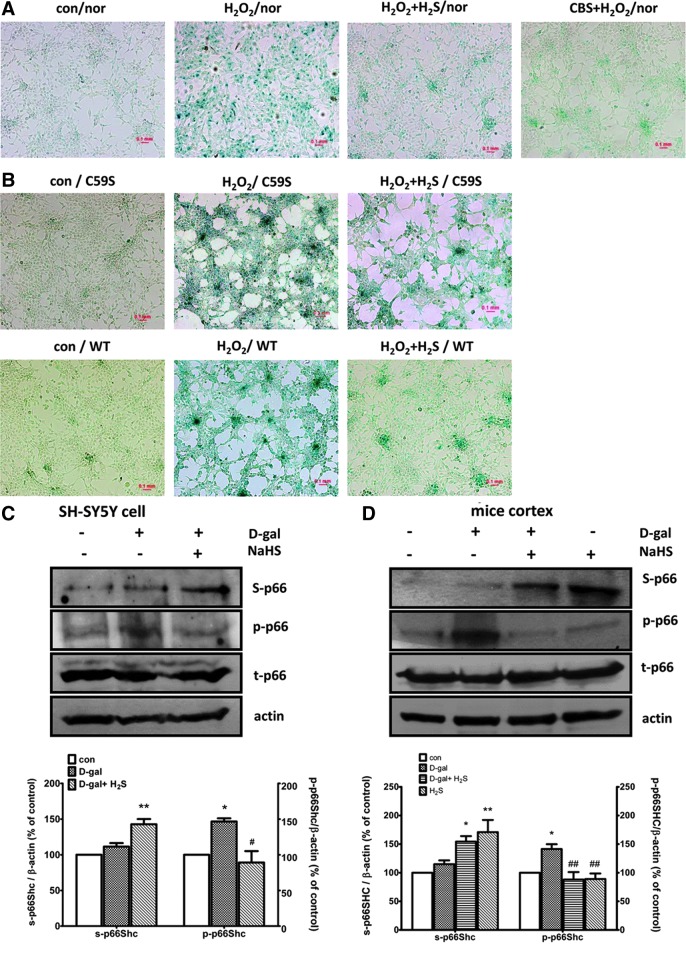

Effect of H2S on oxidative stress-induced senescence

As intracellular oxidative stress is thought to be a common trigger for activation of the senescence program, we next investigated the effect of H2S on H2O2-induced cellular senescence with a standard senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining assay. H2O2 treatment increased the number of SA-β-gal-positive cells (stained as blue color), while both CBS overexpression and 100 μM NaHS pretreatment for 30 min significantly reversed H2O2-induced senescence in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 6A). A similar result was also observed in HEK293 cells transfected with WT p66Shc. The C59S mutation attenuated the protective effect of H2S on cellular senescence (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

H2S inhibited H2O2-induced cellular senescence and p66Shc sulfhydration in senescent cell and mouse model. (A) NaHS pretreatment (100 μM, 30 min) or CBS overexpression reduced H2O2-induced SH-SY5Y cell senescence. Cells were treated with H2O2 (50 μM, 1 h) followed by culture in 10% serum Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium for another 24 h. (B) C59S attenuated the inhibitory effect of H2S on cell senescence. For overexpression experiments, SH-SY5Y cells were transfected with pcDNA3-p66Shc or pcDNA3-p66Shc-C59S cDNAs for 48 h before the experiments. (C, D) Increased sulfhydration and decreased phosphorylation of p66Shc in H2S-treated senescent SH-SY5Y cells (C) or the senescent mice cortex induced by D-galactose (D). Mice were injected with 150 mg/kg D-galactose subcutaneously per day for 8 weeks. NaHS (5.6 mg/kg) was given intraperitoneally 1 h before each D-galactose injection. Cells were pretreated with NaHS (100 μM, 30 min) followed by 200 mM D-galactose for 48 h, as described previously (12). The values are presented as mean±SEM from three to four independent experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 versus control group, #p<0.05, ##p<0.01 versus H2O2-treated group. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

This is similar to what we observed in the D-galactose-induced cellular senescence model in our previous study (12). Rodent chronic administration of D-galactose has been used as an animal model in aging research (31). We also monitored phosphorylation and sulfhydration of p66Shc in D-galactose-induced cellular and animal senescent models. As shown in Figure 6C and D, NaHS treatment significantly induced sulfhydration of p66Shc, but reversed D-galactose-induced p66Shc phosphorylation in senescent SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 6C) and senescent mice cortex (Fig. 6D).

Discussion

H2S has been recognized to be a potent reducing agent, which can react directly with and quenches the superoxide anion (O2−) as well as other ROS (25). The present study, however, demonstrated that H2S may act as an endogenous antioxidant mediator by inhibition of p66Shc-mediated mitochondrial ROS production, rather than via the direct quenching function.

Intracellular oxidative stress and redox imbalance are mainly caused by ROS overproduction or deficiency of enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidants. Mitochondria are the major source of intracellular ROS and a leak from the electron transfer chain is thought to be the main route (28). Mounting evidence shows that p66Shc is involved in mitochondrial redox signaling and its phosphorylation at serine-36 acts as a switch on mitochondrial ROS production (4, 6). Our results showed here that H2O2 significantly enhanced the interaction between PKCβII and p66Shc, which in turn, resulted in the phosphorylation of p66Shc. All these effects were largely reversed by either exogenous NaHS treatment or CBS overexpression. Consistently, both exogenous and endogenous H2S also decreased mitochondrial ROS generation and the oxidative stress-induced senescence. It is plausible that inhibition of the p66Shc-mediated mitochondrial redox signaling pathway contributes to the antioxidant function of H2S.

It was believed that cysteine, at physiological pH conditions, often has a low pKa value and exists predominantly as thiolate anions (S−). The thiolate anions behave as strong nucleophiles and high susceptibility to modification (15). Using a modified biotin switch (S-sulfhydration) assay, which was originally used to monitor nitrosylation, Mustafa et al. demonstrated that as many as 39 proteins in the liver were sulfhydrated by H2S. The sulfhydration had been proposed to emerge as a major functional alteration of proteins (18). As we mentioned above, p66Shc contains a serine residue at position 36 in the N-terminal CH2 domain and its phosphorylation, mediated by PKCβII, seemed to be critical for coupling p66Shc to mitochondrial oxidative stress responses. It is important to note that the unique cysteine (Cys-59) also located within the same domain besides Ser-36. Thereby, we speculate that H2S-mediated p66Shc modification, which is performed by impelling an additional sulfur to the thiol (-SH) group of cysteine to form a persulfide (-SSH) bond, promotes a conformational change in the CH2 domain. The conformational change will then trigger alterations in the local structure (due to electrostatic interactions, etc.). This results in the Ser-36 residue, difficult to be exposed and therefore less phosphorylated by PKCβII. However, this hypothesis warrants further investigation.

Oxidative stress is the important factor for cellular senescence, aging, and neurodegeneration (35). Chronic administration of D-galactose has been used in aging research for a long time and oxidative stress was considered one of the main mechanisms (29, 31). In this study, we proved that H2S attenuated intracellular oxidative stress and provided cytoprotection in the D-galactose-induced SH-SY5Y cell aging model (12). We further revealed that H2S treatment caused an increased p66Shc sulfhydration in parallel with a decreased phosphorylation in the cortex of mice treated with D-galactose. Our data may imply a potential therapeutic function of H2S in retarding aging development.

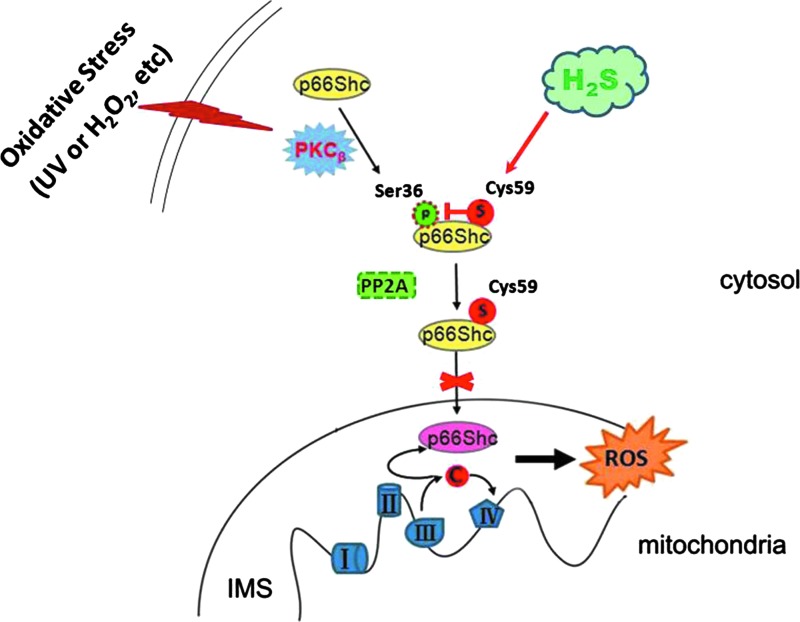

In summary, we demonstrated for the first time that H2S inhibits mitochondrial ROS production via sulfhydration of Cys-59 residue and, in turn, prevention of p66Shc phosphorylation (Fig. 7). These novel results may help to understand the important role of the H2S/CBS system in oxidative stress and oxidative stress-related disease.

FIG. 7.

Proposed model for the effect of H2S on p66Shc-mediated mitochondrial ROS generation. H2S sulfhydrates p66Shc at cysteine-59 in the N-terminal CH2 domain. This modification disrupts the association between PKCβII and p66Shc and therefore leads to the inhibition of PKCβII-mediated p66Shc phosphorylation at Ser36. This, in turn, inhibits p66Shc translocation to mitochondria and therefore decreases mitochondrial ROS production. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

The human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y and human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection and cultured in 10% serum Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Hyclone) plus 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C in 5% CO2. The cells were used for experiments when they grew to about 80% confluence.

Mitochondrial ROS production measurement

Cells at equal number were seeded in black 96-well plates or 35-mm dishes, incubated with different concentrations (10, 25, 50, 100, 200 μM) of H2O2 for different periods (30, 60, 120, or 240 min). In the H2S treatment group, cells were pretreated with different concentrations of NaHS (1, 10, 30, 100 μM) 30 min before administration of H2O2. At the end of treatment, the 5 μM MitoSOX reagent (Molecular Probes) was applied at 37°C for 30 min in the dark. Cells were then washed with warmed Hank's Balanced Salt Solution and subjected to fluorescence measurement using a fluorescent microscope (Nikon, with a DAPI counterstain for nuclear) or a fluorescence reader (Safire2, Tecan Group Ltd.; Ex/Em=510/580 nm).

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was detected with the MTT method, as described previously (37). Briefly, cells were pretreated with 100 μM NaHS for 30 min, washed, and then incubated with 50 μM H2O2 for 4 h. One hundred microliters of fresh medium containing 0.5 mg/ml MTT was added and incubated at 37°C for another 4 h. Finally, the culture medium containing MTT was removed. Dimethyl sulfoxide (150 μl) was then added and the absorbance at 570 nm was measured using a spectrophotometric plate reader (Safire2, Tecan Group Ltd.).

H2S measurement

The H2S level in the culture supernatant was measured as described previously (34). Briefly, CBS transfected cells were cultured in 10% serum phenol red-free DMEM for 48 h and 800 μl culture supernatants were collected. Then, 8 μl of NaOH (1 N), 80 μl of N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine sulfate (20 mM in 7.2 M HCl), and 80 μl of FeCl3 (30 mM in 1.2 M HCl) were added sequentially. The mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 20 min and the absorbance was detected at 668 nm. The H2S concentration was assessed with a standard curve of NaHS.

Plasmids and cell transfection

The pME18S-CBS-HA cDNA was kindly provided by Dr. Hideo Kimura (National Institute of Neuroscience and Psychiatry, Japan). pcDNA3-p66Shc and pcDNA3-p66Shc-C59S (Cys-59 was mutated to serine) were gifts from Dr. Mauro Cozzolino (Laboratory of Neurochemistry, Italy). The cDNAs were subcloned and isolated using the QIAGEN Plasmid Mini Kit (QIAGEN). Transient transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) for 6 h in Opti-MEM (Gibco).

Cellular senescence assay

Cells were pretreated with or without H2S for 30 min followed by stimulation with 50 μM H2O2 for 1 h, then transferred to normal 10% serum DMEM and cultured continually for 24 h. Cellular senescence was detected using a Senescence-β-galactosidase staining kit from Cell Signaling Technology according to the manufacturer's protocol. Images were acquired with a Nikon light microscope. SA-β-gal-positive cells were stained as blue color.

PP2A activity assay

The PP2A activity was detected using the SensoLyte® FDP Protein Phosphatase Assay Kit (AnaSpec, Inc.) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell fractionation and mitochondria isolation

Cell fractionation was performed as described previously (32). Briefly, cells were scraped in 0.5 ml of precold extract buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.3, 2 mM EDTA, 250 mM sucrose, and protease inhibitors) and lysed with liquid nitrogen twice. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 500 g at 4°C for 5 min to discard the nucleus-rich pellet and then recentrifuged at 20,000 g at 4°C for 20 min to collect the supernatant, which was used as a cytosolic fraction. The pellet was lysed again with a 50 μl traditional lysis buffer containing 1% Triton X-100 at 4°C for 1 h and centrifuged at 20,000 g at 4°C for 20 min. The supernatant was collected as particulate membrane fraction.

Mitochondria were isolated from at least 1×108 cells using a mitochondria isolation kit for cultured cells (Thermo Scientific) according to the method recommended by the manufacturer.

S-sulfhydration assay (modified biotin switch)

The assay was performed as described previously (18, 19) with minor modification. Briefly, cells were homogenized by sonication in the HEN buffer (250 mM Hepes-NaOH pH 7.7, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.1 mM neocuproine) supplemented with 100 μM deferoxamine and centrifuged (13,000 g, 30 min, 4°C). Cell lysates were treated with different NaHS (37°C, 30 min) followed by a 30-min incubation with or without 2 mM idoacetamine. The blocking buffer (2.5% SDS HEN buffer and 20 mM MMTS) was then added (50°C, 20 min) and the MMTS was removed by precold acetone (−20°C, 20 min). After removal of acetone (13,000 g, 4°C, 10 min), the proteins were resuspended in the HENS buffer (adjusted to 1% SDS). Leaving a part of the mixture as control (input), the remaining was added with 1 mM biotin-HPDP and incubated at 25°C for 3 h. Finally, the biotinylated proteins were precipitated by streptavidin-agarose beads, eluted by the SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer, and subjected to Western blot alongside the input.

Western blotting and coimmunoprecipitation analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (36). The final concentrations of primary antibodies were anti-phospho-s36-p66Shc (abcam) 0.4 μg/ml, anti-p66Shc (R&D Systerms) 0.5 μg/ml, anti-PP2A, anti-PKCβII (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) 4 μg/ml, anti-β-actin (Sigma) 0.4 μg/ml, and anti-Porin (Cell Signal Technology) 1:1000.

For coimmunoprecipitation, about 500 μg sample protein was used and incubated with 4 μg anti-PKCβII antibodies at 4°C overnight. One hundred microliters of protein G agarose beads was then used to pull down the target protein. The beads were washed, eluted, and finally subjected to Western blotting analysis detected with the anti-p66Shc antibody.

Subcellular colocalization assays

Cells were seeded onto glass coverslips coated with poly-L-lysine. The fluorescent dye for mitochondria, CellLight® Mitochondria-RFP (Molecular Probes), was added 1 day before the experiment. At the end of experiment, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin for 1 h. After incubation with mouse anti-p66Shc (1:50) at 4°C overnight, coverslips were subjected to Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:1000; Molecular Probes) for 1 h at room temperature, then mounted, and viewed using a laser scanning confocal microscope (FV300; Olympus). Images were processed using FLUOVIEW Viewer software.

Animal experiments

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of National University of Singapore.

After 4 weeks of acclimatization to the home cage, 7-week-old female C57 BL/6J mice (18±3 g) were randomly divided into four groups: control, D-galactose model, D-galactose plus H2S treatment, and H2S treatment alone groups. The mice in the D-galactose model group were subcutaneously injected with 150 mg/kg D-galactose per day for 8 weeks, while those of the control group were treated with the same volume of 0.9% NaCl. The mice in the D-galactose plus H2S treatment group received daily intraperitoneal injection of 7.6 mg/kg NaHS for 3 days, before and during injection of D-galactose. The mice in the H2S alone group received only 7.6 mg/kg NaHS intraperitoneal injection. Animals were sacrificed and cerebral cortexes were harvested for Western blotting analysis.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean±SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test for multiple group comparison. p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Abbreviations Used

- 3-MST

3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase

- C59S

cysteine-59 mutation to serine

- C59S-HEK

HEK293 cells transfected with pcDNA3-p66Shc-C59S cDNAs

- CBS

cystathionine β-synthase

- CH1

the central collagen homology domain

- CSE

cystathionine γ-lyase

- Cys-59

cysteine residue at position 59 in the CH2 domain of p66Shc

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- NO

nitric oxide

- PKCβII

protein kinase C-βII

- PTB

phosphotyrosine-binding domain

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SA-β-gal

senescence-associated β-galactosidase

- SDS-PAGE

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- Ser-36

serine residue at position 36 in the CH2 domain of p66Shc

- SH2

the Src homology 2 domain

- WT

wild type

- WT-HEK293

HEK293 cells transfected with pcDNA3-p66Shc cDNAs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NUSHS bench-to-bedside grant NUHSRO/2011/012/STB/B2B-08 and the National Kidney Foundation NKFRC/2011/01/04.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that no competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Abe K. and Kimura H. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide as an endogenous neuromodulator. J Neurosci 16: 1066–1071, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denu JM. and Tanner KG. Specific and reversible inactivation of protein tyrosine phosphatases by hydrogen peroxide: evidence for a sulfenic acid intermediate and implications for redox regulation. Biochemistry 37: 5633–5642, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Shewy HM, Abdel-Samie SA, Al Qalam AM, Lee MH, Kitatani K, Anelli V, Jaffa AA, Obeid LM, and Luttrell LM. Phospholipase C and protein kinase C-beta 2 mediate insulin-like growth factor II-dependent sphingosine kinase 1 activation. Mol Endocrinol 25: 2144–2156, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galimov ER. The Role of p66shc in Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis. Acta Naturae 2: 44–51, 2010 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gertz M, Fischer F, Wolters D, and Steegborn C. Activation of the lifespan regulator p66Shc through reversible disulfide bond formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 5705–5709, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gertz M. and Steegborn C. The Lifespan-regulator p66Shc in mitochondria: redox enzyme or redox sensor? Antioxid Redox Signal 13: 1417–1428, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giorgio M, Migliaccio E, Orsini F, Paolucci D, Moroni M, Contursi C, Pelliccia G, Luzi L, Minucci S, Marcaccio M, Pinton P, Rizzuto R, Bernardi P, Paolucci F, and Pelicci PG. Electron transfer between cytochrome c and p66Shc generates reactive oxygen species that trigger mitochondrial apoptosis. Cell 122: 221–233, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu LF, Lu M, Tiong CX, Dawe GS, Hu G, and Bian JS. Neuroprotective effects of hydrogen sulfide on Parkinson's disease rat models. Aging Cell 9: 135–146, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimura Y, Goto Y, and Kimura H. Hydrogen sulfide increases glutathione production and suppresses oxidative stress in mitochondria. Antioxid Redox Signal 12: 1–13, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishnan N, Fu C, Pappin DJ, and Tonks NK. H2S-Induced sulfhydration of the phosphatase PTP1B and its role in the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Sci Signal 4: ra86, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu L, Cui J, Song CJ, Bian JS, Sparatore A, Soldato PD, Wang XY, and Yan CD. H(2)S-releasing aspirin protects against aspirin-induced gastric injury via reducing oxidative stress. PLoS One 7: e46301, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu YY, Nagpure BV, Wong PT, and Bian JS. Hydrogen sulfide protects SH-SY5Y neuronal cells against d-galactose induced cell injury by suppression of advanced glycation end products formation and oxidative stress. Neurochem Int 62: 603–609, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu M, Liu YH, Goh HS, Wang JJ, Yong QC, Wang R, and Bian JS. Hydrogen sulfide inhibits plasma renin activity. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 993–1002, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu M, Zhao FF, Tang JJ, Su CJ, Fan Y, Ding JH, Bian JS, and Hu G. The neuroprotection of hydrogen sulfide against MPTP-induced dopaminergic neuron degeneration involves uncoupling protein 2 rather than ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Antioxid Redox Signal 17: 849–859, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marino SM. and Gladyshev VN. Analysis and functional prediction of reactive cysteine residues. J Biol Chem 287: 4419–4425, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martelli A, Testai L, Breschi MC, Blandizzi C, Virdis A, Taddei S, and Calderone V. Hydrogen sulphide: novel opportunity for drug discovery. Med Res Rev 32: 1093–1130, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Migliaccio E, Giorgio M, Mele S, Pelicci G, Reboldi P, Pandolfi PP, Lanfrancone L, and Pelicci PG. The p66shc adaptor protein controls oxidative stress response and life span in mammals. Nature 402: 309–313, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mustafa AK, Gadalla MM, Sen N, Kim S, Mu W, Gazi SK, Barrow RK, Yang G, Wang R, and Snyder SH. H2S signals through protein S-sulfhydration. Sci Signal 2: ra72, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mustafa AK, Sikka G, Gazi SK, Steppan J, Jung SM, Bhunia AK, Barodka VM, Gazi FK, Barrow RK, Wang R, Amzel LM, Berkowitz DE, and Snyder SH. Hydrogen sulfide as endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor sulfhydrates potassium channels. Circ Res 109: 1259–1268, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan TT, Chen YQ, and Bian JS. All in the timing: a comparison between the cardioprotection induced by H2S preconditioning and post-infarction treatment. Eur J Pharmacol 616: 160–165, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan TT, Feng ZN, Lee SW, Moore PK, and Bian JS. Endogenous hydrogen sulfide contributes to the cardioprotection by metabolic inhibition preconditioning in the rat ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 40: 119–130, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pelicci G, Dente L, De Giuseppe A, Verducci-Galletti B, Giuli S, Mele S, Vetriani C, Giorgio M, Pandolfi PP, Cesareni G, and Pelicci PG. A family of Shc related proteins with conserved PTB, CH1 and SH2 regions. Oncogene 13: 633–641, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perkins ND. Cysteine 38 holds the key to NF-kappaB activation. Mol Cell 45: 1–3, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pinton P, Rimessi A, Marchi S, Orsini F, Migliaccio E, Giorgio M, Contursi C, Minucci S, Mantovani F, Wieckowski MR, Del Sal G, Pelicci PG, and Rizzuto R. Protein kinase C beta and prolyl isomerase 1 regulate mitochondrial effects of the life-span determinant p66Shc. Science 315: 659–663, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Predmore BL, Lefer DJ, and Gojon G. Hydrogen sulfide in biochemistry and medicine. Antioxid Redox Signal 17: 119–140, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ravichandran KS. Signaling via Shc family adapter proteins. Oncogene 20: 6322–6330, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sen N, Paul BD, Gadalla MM, Mustafa AK, Sen T, Xu R, Kim S, and Snyder SH. Hydrogen sulfide-linked sulfhydration of NF-kappaB mediates its antiapoptotic actions. Mol Cell 45: 13–24, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sena LA. and Chandel NS. Physiological roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell 48: 158–167, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen YX, Xu SY, Wei W, Sun XX, Yang J, Liu LH, and Dong C. Melatonin reduces memory changes and neural oxidative damage in mice treated with D-galactose. J Pineal Res 32: 173–178, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sommer D, Coleman S, Swanson SA, and Stemmer PM. Differential susceptibilities of serine/threonine phosphatases to oxidative and nitrosative stress. Arch Biochem Biophys 404: 271–278, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song X, Bao M, Li D, and Li YM. Advanced glycation in D-galactose induced mouse aging model. Mech Ageing Dev 108: 239–251, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tiong CX, Lu M, and Bian JS. Protective effect of hydrogen sulphide against 6-OHDA-induced cell injury in SH-SY5Y cells involves PKC/PI3K/Akt pathway. Br J Pharmacol 161: 467–480, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomilov AA, Bicocca V, Schoenfeld RA, Giorgio M, Migliaccio E, Ramsey JJ, Hagopian K, Pelicci PG, and Cortopassi GA. Decreased superoxide production in macrophages of long-lived p66Shc knock-out mice. J Biol Chem 285: 1153–1165, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang XH, Wang F, You SJ, Cao YJ, Cao LD, Han Q, Liu CF, and Hu LF. Dysregulation of cystathionine gamma-lyase (CSE)/hydrogen sulfide pathway contributes to ox-LDL-induced inflammation in macrophage. Cell Signal 25: 2255–2262, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei H, Li L, Song Q, Ai H, Chu J, and Li W. Behavioural study of the D-galactose induced aging model in C57BL/6J mice. Behav Brain Res 157: 245–251, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xie L, Hu LF, Teo XQ, Tiong CX, Tazzari V, Sparatore A, Del Soldato P, Dawe GS, and Bian JS. Therapeutic effect of hydrogen sulfide-releasing L-Dopa derivative ACS84 on 6-OHDA-induced Parkinson's disease rat model. PLoS One 8: e60200, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu ZS, Wang XY, Xiao DM, Hu LF, Lu M, Wu ZY, and Bian JS. Hydrogen sulfide protects MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells against H2O2-induced oxidative damage-implications for the treatment of osteoporosis. Free Radic Biol Med 50: 1314–1323, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang G, Zhao K, Ju Y, Mani S, Cao Q, Puukila S, Khaper N, Wu L, and Wang R. Hydrogen sulfide protects against cellular senescence via S-sulfhydration of Keap1 and activation of Nrf2. Antioxid Redox Signal 18: 1906–1919, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]