Abstract

Aims: Hypoxia induces expression of various genes and microRNAs (miRs) that regulate angiogenesis and vascular function. In this study, we investigated a new functional role of new hypoxia-responsive miR-101 in angiogenesis and its underlying mechanism for regulating heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression. Results: We found that hypoxia induced miR-101, which binds to the 3′untranslated region of cullin 3 (Cul3) and stabilizes nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) via inhibition of the proteasomal degradation pathway. miR-101 overexpression promoted Nrf2 nuclear accumulation, which was accompanied with increases in HO-1 induction, VEGF expression, and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS)-derived nitric oxide (NO) production. The elevated NO-induced S-nitrosylation of Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 and subsequent induction of Nrf2-dependent HO-1 lead to further elevation of VEGF production via a positive feedback loop between the Nrf2/HO-1 and VEGF/eNOS axes. Moreover, miR-101 promoted angiogenic signals and angiogenesis both in vitro and in vivo, and these events were attenuated by inhibiting the biological activity of HO-1, VEGF, or eNOS. Moreover, these effects were also observed in aortic rings from HO-1+/− and eNOS−/− mice. Local overexpression of miR-101 improved therapeutic angiogenesis and perfusion recovery in the ischemic mouse hindlimb, whereas antagomiR-101 diminished regional blood flow. Innovation: Hypoxia-responsive miR-101 stimulates angiogenesis by activating the HO-1/VEGF/eNOS axis via Cul3 targeting. Thus, miR-101 is a novel angiomir. Conclusion: Our results provide new mechanistic insights into a functional role of miR-101 as a potential therapeutic target in angiogenesis and vascular remodeling. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 21, 2469–2482.

Introduction

Local tissue hypoxia affects embryonic development as well as many pathophysiological processes in adult life, including wound healing, myocardial infarction, peripheral arterial disease, and tumor progression (1, 10, 17, 28). As a consequence, the complex angiogenic process is activated in hypoxic tissues to generate new blood vessels from pre-existing vascular beds, which supply oxygen and nutrients to hypoxic organs and tissues (10). This biological process is tightly regulated by a balance of endogenous pro-angiogenic growth factors (e.g., vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF] and fibroblast growth factor) and anti-angiogenic molecules (e.g., thrombospondin, angiostatin, and endostatin). Dynamic regulation of these factors in local microenvironments and vascular tissues contributes to the pathogenesis and tissue repair processes of hypoxia-associated diseases.

Innovation.

The present study provides evidence that hypoxia-responsive microRNA (miR)-101 downregulates cullin 3 by targeting its 3′untranslated region and activates the nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)/heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1)/vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)/endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS)-derived nitric oxide (NO) production pathway. Elevated NO further amplifies HO-1-mediated, but oxygen-independent, VEGF production through S-nitrosylation of Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1, leading to a positive feedback circuit between the Nrf2/HO-1 and VEGF/eNOS axes. Moreover, miR-101 overexpression promotes angiogenesis and improves perfusion recovery in a mouse hindlimb ischemia model. These data highlight the importance of miR-101 as a novel therapeutic angiomiR to regulate angiogenesis and vascular remodeling.

VEGF, a known pro-angiogenic factor, is mainly upregulated by the oxygen-sensitive transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), a master factor of cellular response to hypoxia (37). Under normoxic conditions, HIF-1α is hydroxylated at proline residues 402 and/or 564 by prolyl hydroxylase domain protein (PHD) and increases interaction with the von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) protein, leading to ubiquitination-dependent proteasomal degradation (51). However, hypoxia inhibits hydroxylase activity, subsequently leading to HIF-1α stabilization. Conversely, this transcription factor is also regulated in an O2-independent manner via an interaction with heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) and translational activation (14, 51). We and others have shown that degradation products, such as bilirubin and carbon monoxide (CO), of heme by heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) stimulate angiogenesis by increasing VEGF expression (13, 30), implicating HO-1 as a potent angiogenic modulator.

HO-1, a phase II enzyme, catalyzes the rate-limiting step in heme degradation, resulting in CO liberation, iron, and biliverdin, in which biliverdin is converted to bilirubin by biliverdin reductase (44). HO-1 is induced by protecting the transcription factor nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) from Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1)/cullin (Cul)3/E3 ligase complex-mediated degradation after exposure to various stimulants, including heme, hypoxia, cytokines, and growth factors (52). Recent studies demonstrated that either Cul3 mutation or siRNA-based Cul3 knockdown confers Nrf2 activation and upregulates phase II genes (43, 47). However, Cul3 overexpression negatively regulates the biological function of Nrf2 (43). These evidence suggest a possibility that functional loss of Cul3 may increase Nrf2 stability, which then leads to induction of HO-1 expression and an angiogenic switch.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-protein-coding single-stranded RNA molecules of 21–23 nucleotides that negatively regulate protein expression in various organisms, mainly by promoting mRNA degradation or inhibiting mRNA translation via binding to the 3′untranslated region (3′UTR) of their targeted mRNAs (3, 4). It is now evident that miRNAs are major players involved in many aspects of vascular homeostasis and the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases, including angiogenesis, vascular remodeling, and myocardial infarction (4, 5, 9, 24). Since Poliseno et al. first demonstrated that miRNAs (miRs)-221/222 modulate the angiogenic activity of stem cell factor by targeting its receptor c-Kit (49), many miRNAs have emerged as critical players in the regulation of angiogenesis and vascular function. For example, miR-34a is known to regulate cardiac aging and function via inhibition of senescence-associated PNUTS expression (6). miRs-199a/590 is also suggested to stimulate cardiac regeneration via proliferation of adult cardiomyocytes (22). In addition, the miR-132 and miR-17–92 cluster, which is expressed in human tumors, promotes tumor angiogenesis by suppressing p120RasGAP expression and the thrombospondin family, respectively (2, 19). Moreover, miR-132 secreted by human pericyte progenitor cells has been shown to improve cardiac function via induction of angiogenesis in a paracrine mode of action after myocardial infarction in the mouse (35). Although some miRNAs, including miRs-10/30 family/126, are shown to facilitate angiogenesis by promoting VEGF signaling (7, 29, 46), miRs-492/195/16/15a function as anti-angiogenic molecules via VEGF expression inhibition (48, 53, 57). Therefore, identifying the function of new pro-angiogenic miRNAs may be valuable to further understand the molecular mechanisms of neovascularization and establish new therapeutic strategies for ischemic diseases.

Some miRNAs are identified to be regulated under hypoxic conditions, and a subset of hypoxic responsive miRNAs, including Let-7 and miRs-93/103/107/424, is considered pro-angiogenic (13, 27, 30). Although miR-101 is downregulated in some human prostate tumors during tumor progression (56), this molecule is upregulated in endothelial cells (ECs) exposed to shear stress and can modulate endothelial homeostasis (12). In this study, we found that miR-101 is increased under hypoxic conditions and stimulates angiogenesis to improve blood perfusion in mouse ischemic hindlimbs via the HO-1/VEGF axis. This effect is achieved by targeting Cul3, a key modulator of Nrf2-mediated HO-1 induction. Our study thus concludes that hypoxia-responsive miR-101 plays an important physiological role in post-ischemic neovascularization and vascular remodeling.

Results

Hypoxia-induced miR-101 regulates Cul3 expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells

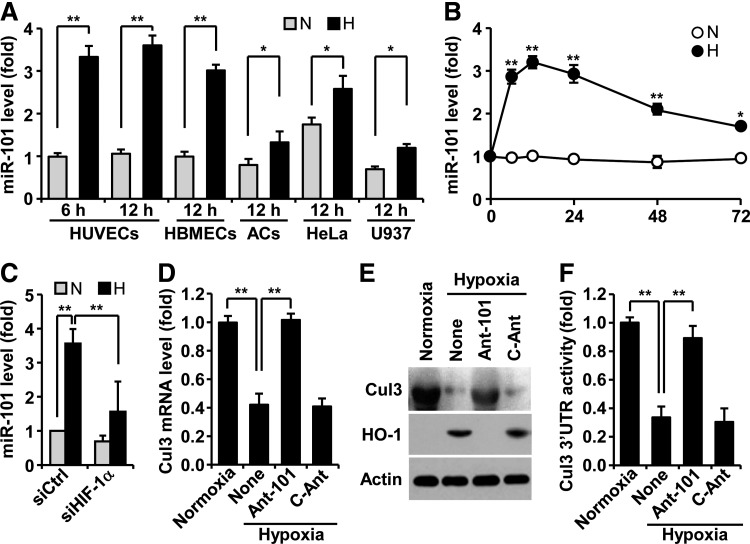

To assess whether hypoxia regulates miR-101 biogenesis, human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were exposed to normoxia and hypoxia, and expression levels of miR-101 were determined by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Hypoxia induced about a 3.5-fold increase in miR-101 expression at 6 h, as compared with normoxia, and no further increase at 12 h (Fig. 1A). Human brain microvascular ECs revealed a similar response to hypoxia-induced miR-101 expression, and additional cell types, including astrocytes, HeLa, and U937, also increased, but to a lesser extent (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, basal levels of miR-101 in normoxic HeLa cells were significantly higher than those of other normoxic cells. The level of miR-101 rapidly increased in ECs 6 h after exposure to hypoxia and remained almost unchanged until 24 h. Thereafter, a gradual decrease in its steady-state level was observed at 72 h (Fig. 1B). Elevated miR-101 levels in hypoxic HUVECs were blocked by HIF-1α knockdown (Fig. 1C), suggesting that miR-101 is upregulated in an HIF-1α-dependent manner under hypoxic conditions. We next predicted highly reliable targets of miR-101 using TargetScan, microRNA.org, and miRDB. Among 31 target genes, Cul3 was selected as a new target of miR-101 (Supplementary Fig. S1A; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/ars), as this gene is known to play a key role in hypoxia-associated expression of HO-1, which modulates angiogenesis (18). To verify whether Cul3 is a bonafide target of miR-101, we tested whether its expression is downregulated by hypoxia. Hypoxia decreased the expression levels of Cul3 mRNA and protein in HUVECs, and these decreases were completely restored by transfection with antagomiR-101, as compared with control antagomiR (Fig. 1D, E). Moreover, HO-1 as a downstream target of Cul3 was effectively induced by hypoxia, and its expression was abolished by transfection with antagomiR-101 (Fig. 1E). Computational prediction showed that the 3′UTR of human Cul3 mRNA contains four possible conserved seed-matched sites for miR-101, with the second and third sites identified as more important than the others (Supplementary Fig. S1B). In addition, the 3′UTR of mouse Cul3 also conatins a conserved seed-matched site for miR-101 (Supplementary Fig. S1C). Therefore, we further explored miR-101 targeting of the Cul3 3′UTR region containing both canonical seed sites. Hypoxia decreased the 3′UTR activity of Cul3 as compared with normoxia, and this decrease was reversed by transfection of antagomiR-101, but not by control antagomiR (Fig. 1F). These results suggest that hypoxia-responsive miR-101 inhibits Cul3 expression by destabilizing its 3′UTR activity.

FIG. 1.

Hypoxia induces upregulation of miR-101, which targets Cul3 in ECs. (A) HUVECs, HBMECs, human primary ACs, HeLa cells, and U937 cells were maintained under normoxia (N) and hypoxia (H). miR-101 expression levels were determined by qRT-PCR. (B) Time course of miR-101 levels was determined in HUVECs exposed to normoxia and hypoxia. (C) Cells transfected with control or HIF-1α siRNA were maintained under normoxia and hypoxia, and miR-101 levels were quantified. (D, E) Cells were transfected with antagomiR-101 (Ant-101) or control antagomiR (C-Ant) and maintained under normoxia or hypoxia for 12 h. Cul3 and HO-1 expression levels were determined by qRT-PCR and Western blotting. (F) Cul3 3′UTR activity was determined using a dual-luciferase report assay system of psiCHECK™-2/Cul3 3′UTR. Data shown in graphs are the mean±SD (n=3). *p<0.05 and **p<0.01. 3′UTR, 3′untranslated region; AC, astrocyte, Cul3, cullin3; HBMEC, human brain microvascular endothelial cell; HIF-1α, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cell; miRNA, miR, microRNA; qRT-PCR, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; SD, standard deviation.

miR-101 upregulates Nrf2-dependent HO-1 expression by directly targeting Cul3

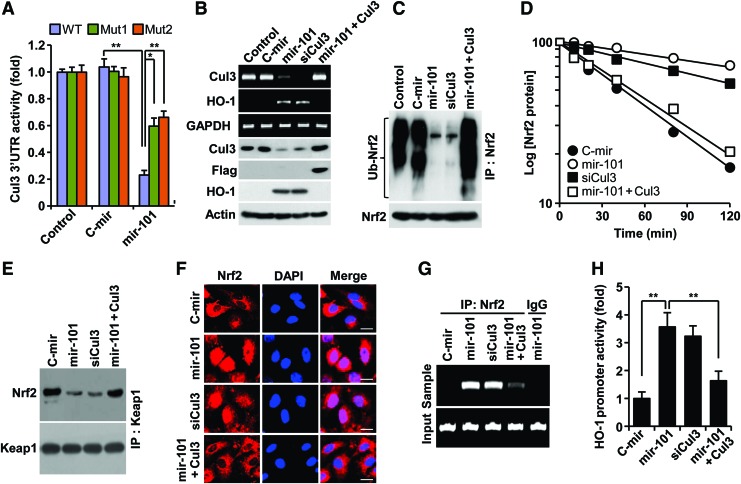

Since Cul3 is a scaffold protein in the E3 ligase complex, which negatively regulates HO-1 expression via ubiqutination-mediated proteasomal degradation of Nrf2 from Nrf2-Keap1 system (38), we determined a functional role of miR-101 in Nrf2-dependent HO-1 expression via Cul3 downregulation. Transfection with a precursor miR-101 (pre-mir-101) expression vector increased mature miR-101 levels (Supplementary Fig. S2A). Overexpression of mir-101 effectively inhibited Cul3 3′UTR-WT reporter activity, as compared with the control. This inhibition was markedly, but not completely, reversed by each single mutation of two putative miR-101-binding seed sites (Fig. 2A; Supplementary Fig. S1D). These data indicate that miR-101 binds to both sites. As expected, mir-101 overexpression resulted in a decrease of Cul3 mRNA and protein levels and a subsequent increase in HO-1 expression (Fig. 2B), leading to elevated HO-1 enzyme activity (Supplementary Fig. S2B). We further examined whether miR-101 elicits Nrf2-dependent HO-1 expression via regulation of Cul3-based E3 ligase activity using several biochemical methods. We found that miR-101 significantly inhibited Nrf2 ubiquitination compared with the negative control (Fig. 2C), which resulted in about a fivefold increase in Nrf2 half life (46 vs. 228 min) (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, mir-101 overexpression markedly inhibited the interaction between Keap1 and Nrf2 (Fig. 2E). These effects of miR-101 were nearly abolished by Cul3 overexpression. Further, Cul3 knockdown effectively increased the half life of Nrf2 protein similar to miR-101 (Fig. 2B–E). As a result of this inhibition, miR-101 increased Nrf2 nuclear translocation as confirmed by confocal microscopy (Fig. 2F). We next examined a functional role of nuclear Nrf2 accumulated by miR-101 in HO-1 promoter activation. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay showed an increase in functional binding to the HO-1 promoter in HUVECs overexpressing mir-101 (Fig. 2G). Moreover, luciferase reporter assay indicated that miR-101 significantly increased HO-1 promoter transcriptional activity as compared with the control (Fig. 2H). Expectedly, the promotive effects of miR-101 on Nrf2-dependent HO-1 promoter activity were abolished by Cul3 overexpression. Moreover, Cul3 knockdown showed a similar outcome to Nrf2-mediated HO-1 promoter activity induced by miR-101 (Fig. 2F–H). We further examined the functional role of Nrf2 in hypoxia- and miR-101-mediated HO-1 expresion using siRNA technology. Nrf2 knockdown suppressed the induction of HO-1 expression in ECs by hypoxia and miR-101 (Supplementary Fig. S3A, B). These results indicate that miR-101 increases Nrf2-dependent HO-1 expression through direct targeting of Cul3 3′UTR.

FIG. 2.

miR-101 upregulates Nrf2-dependent HO-1 expression by targeting Cul3. HUVECs were transfected with pSilencer 2.1-U6/pre-miR-101 (mir-101), pSilencer 2.1-U6/control pre-miR (C-mir), or p3xFLAG-CMV10-Cul3 or in combination with the psiCHECK™-2 vector containing wild-type or mutant 3′UTRs of Cul3, followed by incubation in fresh media for 12 h. (A) Cul3 3′UTR activity was determined by dual-luciferase report assay. (B) Cul3 and HO-1 expression levels were determined by RT-PCR and Western blotting. (C) After cells were treated with 5 μM MG132 for 4 h, ubiquitinated Nrf2 was determined by Western blotting after immunoprecipitation. (D) Cells were treated with 0.5 μg/ml actinomycin D for the indicated time period. Nrf2 protein levels were determined by Western blot analysis. Data shown are average values from two individual experiments. (E) Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibodies for Keap1. Interaction between Keap1 and Nrf2 was determined by Western blotting. (F) Nrf2 nuclear translocation was determined in intact cells by immunohistochemistry. Scale bars: 25 μm. (G) Specific binding of Nrf2 to the antioxidant response element of HO-1 promoter was determined by ChIP assay. (H) HO-1 promoter activity was determined using a luciferase-base assay system. The data shown in bar graphs are the mean±SD (n=3). *p<0.05 and **p<0.01. ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; Keap1, kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2-related factor 2; pre-miR-101, precursor miR-101; RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

miR-101 promotes HIF-1α-mediated VEGF expression via HO-1 induction

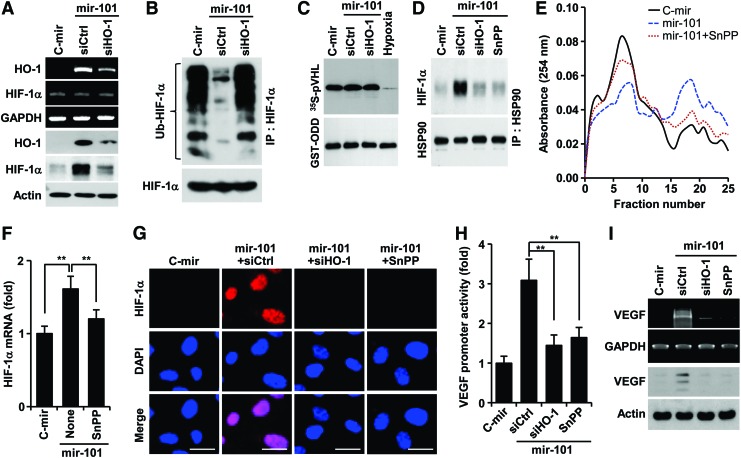

The reaction product of HO-1, CO elevates VEGF expression by increasing HIF-1α protein levels via two distinct mechanisms, translational activation and stabilization of HIF-1α protein (14). We examined whether miR-101 promotes HO-1-mediated stabilization of HIF-1α, which plays an important role in VEGF expression. HUVECs overexpressing mir-101 upregulated HO-1 expression and subsequently stabilized HIF-1α protein, and these increases were inhibited by transfection with HO-1 siRNA (Fig. 3A). These results suggest that miR-101 regulates post-translational increases in HIF-1α protein level in an HO-1 dependent manner. However, miR-101 inhibited ubiquitination of HIF-1α, which was reversed by HO-1 knockdown (Fig. 3B), without affecting biological activity of PHD, the key enzyme responsible for degrading HIF-1α (34), as compared with its activity under hypoxic condition as a positive control (Fig. 3C). This indicates that miR-101 enhances HIF-1α protein levels in an HO-1-dependent, but not in a PHD-dependent manner. Since HSP90 inhibits HIF-1α ubiquitination by physically interacting with HIF-1α, leading to protection of HIF-1α from PHD-independent degradation (14), we further examined the effect of miR-101 on the interaction between HSP90 and HIF-1α. Overexpression of mir-101 enhanced the interaction between HIF-1α and HSP90, and this interaction was blocked by HO-1 knockdown and the HO-1 inhibitor tin-protoporphyrin IX (SnPP) (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, miR-101 increased the formation of a high-molecular-weight polysome complex, which was associated with a high level of HIF-1α mRNA in pooled polysome fractions from 16 to 22. These effects were attenuated by co-treatment with SnPP (Fig. 3E, F), reflecting an increase in HIF-1α mRNA's translational activity. Consequently, miR-101 increased nuclear accumulation of HIF-1α, and this event was suppressed by treatment with HO-1 siRNA and SnPP (Fig. 3G). In addition, miRNA-101 significantly increased VEGF promoter activity and expression, and both effects were reduced by HO-1 siRNA and SnPP (Fig. 3H, I). The HO-1 byproducts, CO, biliverdin, and bilirubin, but not Fe2+, increased the protein levels of HIF-1α and VEGF as well as tube formation (Supplementary Fig. S4A, B). These results indicate that miR-101 stabilizes HIF-1α protein and induces VEGF expression and angiogenesis by increasing HO-1 expression and its reaction products.

FIG. 3.

miR-101 increases HIF-1α-mediated VEGF expression via induction of the HO-1 pathway. HUVECs were transfected with pSilencer 2.1-U6/mir-101 (or pSilencer 2.1-U6/C-mir) or in combination with control siRNA (siCtrtl), HO-1 siRNA (siHO-1) or pGL3-VEGF-Luc for 24 h, followed by treatment with or without SnPP for 12 h. (A) HO-1 and HIF-1α expression levels were determined by RT-PCR and Western blotting. (B) HIF-1α ubiquitination was determined in cell lysates from HUVECs treated with 5 μM MG132 for 12 h. (C) PHD activity was assayed in cell lysates by determining the interaction between [35S]methionine-labeled VHL protein and purified GST-ODD domain. (D) Interaction between HSP90 and HIF-1α was determined after immunoprecipitation with an HSP90 antibody. (E) Cell lysates were ultracentrifuged on sucrose density gradients. The absorbance profiles of collected fractions were determined at 254 nm. (F) The levels of polysome-bound HIF-1α mRNA were determined in samples pooled from fractions 16 to 22. Values represent the mean±SD (n=3). **p<0.01. (G) HIF-1α nuclear translocation was determined by immunohistochemistry. Scale bars: 25 μm. (H) Luciferase reporter activity (mean±SD, n=3) was analyzed in HUVECs transfected with pGL3-VEGF-Luc. **p<0.01. (I) VEGF expression levels were determined by RT-PCR and Western blotting. GST-ODD, glutathione S-transferase-oxygen-dependent degradation; HSP90, heat shock protein 90; PHD, prolyl hydroxylase domain protein; SnPP, tin-protoporphyrin IX; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; VHL, von Hippel–Lindau. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

miR-101 amplifies VEGF expression via a positive feedback circuit between HO-1 activity and VEGF/endothelial nitric oxide synthase axis by S-nitrosylating Keap1

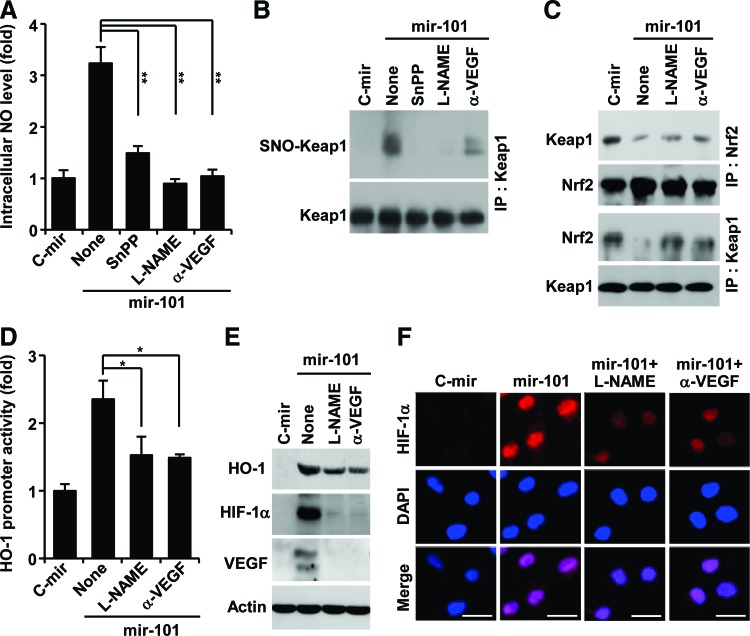

VEGF promotes endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS)-derived nitric oxide (NO) production in ECs, and NO plays important roles in a variety of physiological systems via modification of protein thiols (26, 50). We examined the effects of miRNA-101 on the intracellular NO level in ECs. HUVECs expressing mir-101 exhibited significant increases in NO production, which was inhibited by treatment with SnPP, the NOS inhibitor NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME), and a neutralizing VEGF antibody (Fig. 4A). We next determined the effect of miR-101 on NO-mediated modification of free thiol groups of Keap1 using a S-nitrosylation detection kit. miRNA-101 increased S-nitrosylation of Keap1 in HUVECs, and this modification was inhibited by SnPP, L-NAME, and an anti-VEGF antibody (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, miR-101 inhibited the formation of the Keap1-Nrf2 complex, and this inhibitory effect was suppressed by L-NAME and an anti-VEGF antibody (Fig. 4C). We further examined a role of NO in miR-101-mediated HO-1 expression and VEGF production. miR-101-mediated increases in HO-1 promoter activity were inhibited by L-NAME and an anti-VEGF antibody (Fig. 4D). Western blot analysis showed that elevation of HO-1, HIF-1α, and VEGF expression by miR-101 was also suppressed by treatment with L-NAME and an anti-VEGF antibody (Fig. 4E). Similarly, miR-101-mediated increases in nuclear HIF-1α accumulation were inhibited by L-NAME and an anti-VEGF antibody (Fig. 4F). These results suggest that expression of HO-1 by miR-101 amplifies VEGF production via a positive feedback loop, where eNOS-derived NO elicits S-nitrosylation of Keap1 and subsequent Nrf2 activation.

FIG. 4.

miR-101 amplifies VEGF expression by S-nitrosylating Keap1. HUVECs transfected with the pSilencer 2.1-U6 vector containing mir-101 or C-mir were cultured with or without SnPP, an anti-VEGF antibody (α-VEGF), and L-NAME. (A) Intracellular NO levels (mean±SD, n=3) were determined by confocal microscopy using 4-amino-5-methylamino-2′,7′-difluorofluorescein. **p<0.01. (B) S-Nitrosylation of Keap1 was determined using S-nitrosylated protein detection kit. (C) Interaction between Keap1 and Nrf2 was determined by Western blotting after immunoprecipitation with Keap1 and Nrf2 antibodies. (D) Luciferase activity (mean±SD, n=3) was analyzed in lysates from cells transfected with pGL3-HO-1-Luc. *p<0.05. (E) HO-1, HIF-1α, and VEGF protein levels were determined by Western blotting. (F) Nuclear accumulation of HIF-1α was determined by immunohistochemistry. Scale bars: 25 μm. L-NAME, NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester; NO, nitric oxide. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

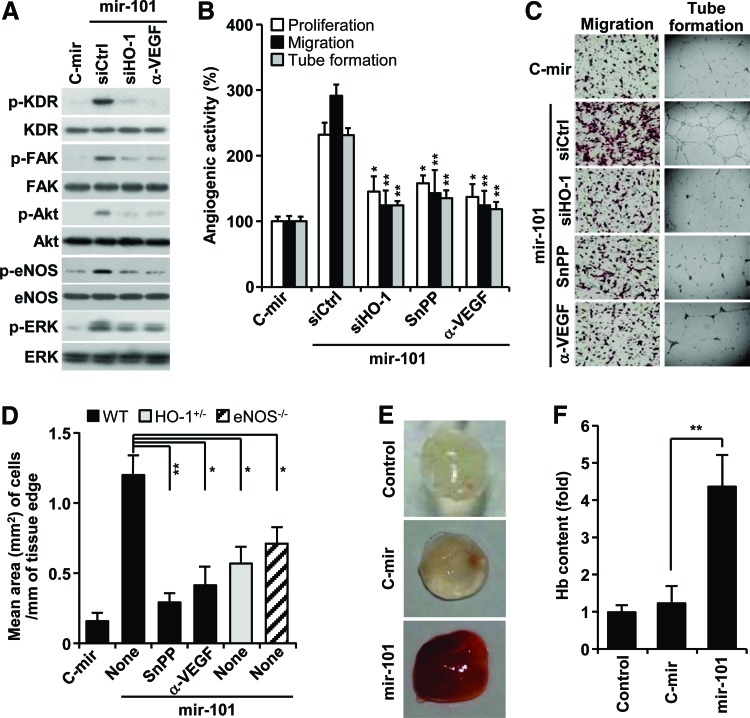

miR-101 stimulates angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo

Based on our data that miRNA-101 increased VEGF production via HO-1 induction (Fig. 3, 4), we further examined the effects of miR-101 on the activation of angiogenic signal mediators (14). Overexpression of mir-101 increased VEGF receptor-2 (KDR) phosphorylation and its downstream effectors, including FAK, Akt, eNOS, and ERK, and these effects were blocked by HO-1 siRNA and an anti-VEGF antibody (Fig. 5A). As expected, miRNA-101 increased proliferation, migration, and tube formation of HUVECs. These effects were significantly suppressed by HO-1 siRNA, SnPP, and an anti-VEGF antibody (Fig. 5B, C). Mouse aortic rings transfected with mir-101 lentivirus, which was confirmed to express mature miR-101 and activate Cul3-mediated HO-1/VEGF axis in HUVECs (Supplementary Fig. S5A, B), led to longer and more abundant sprouts compared with control aortic rings. Importantly, this effect was abolished by the addition of SnPP and an anti-VEGF antibody (Fig. 5D; Supplementary Fig. S6). Moreover, the angiogenic sprouting activity of miR-101 was significantly attenuated in aortic rings from HO-1+/− and eNOS−/− mice (Fig. 5D; Supplementary Fig. S6). These data suggest that miRNA-101 stimulates angiogenesis by amplifying VEGF production via a cross-interaction between HO-1 and eNOS pathways. We further examined the role of miR-101 in the development of functional vasculature in nude mice by Matrigel plug assay. The plug containing mir-101-overexpressing HUVECs appeared dark red (Fig. 5E) and abundantly filled with intact red blood cells (RBCs), as determined by measuring hemoglobin contents (Fig. 5F). However, the plug containing control mir-expressed HUVECs was pale in color and minimally influxed with RBCs, comparable to Matrigel alone (Fig. 5E, F). These results indicate that miR-101 is capable of promoting a functional vasculature via in vivo angiogenesis.

FIG. 5.

miR-101 stimulates angiogenesis via HO-1-mediated VEGF expression. HUVECs were transfected with either pSilencer 2.1-U6/mir-101 or pSilencer 2.1-U6/C-mir or in combination with control or HO-1 siRNA for 24 h and treated with or without SnPP, and an anti-VEGF antibody. (A) Phosphorylation of angiogenic signal molecules was determined by Western blot analysis. (B, C) Cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation were determined by [3H]-thymidine incorporation assay, Boyden chamber assay, and phase-contrast microscopy, respectively. Data represent the mean±SD (n=3). *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 versus miR-101 alone. (D) Aortic rings from wild-type, HO-1+/−, and eNOS−/− mice were transduced with lentivirus carrying mir-101 or C-mir, followed by treatment with or without SnPP and an anti-VEGF antibody on Matrigel plates for 18 days. Endothelial sprouting area was quantitated from the edges of the aortic rings. Data represent the mean±SD (n=6–8 aortic rings per group, two aortic rings were prepared from each mouse). *p<0.05 and **p<0.01. (E, F) HUVECs transfected with lentivirus carrying mir-101 or control mir (C-mir) were mixed with Matrigel and subcutaneously implanted into nude mice. Matrigel plugs were harvested after 7 days. (E) Representative photographs and (F) hemoglobin quantification. Data represent the mean±SD (n=4) **p<0.01. eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

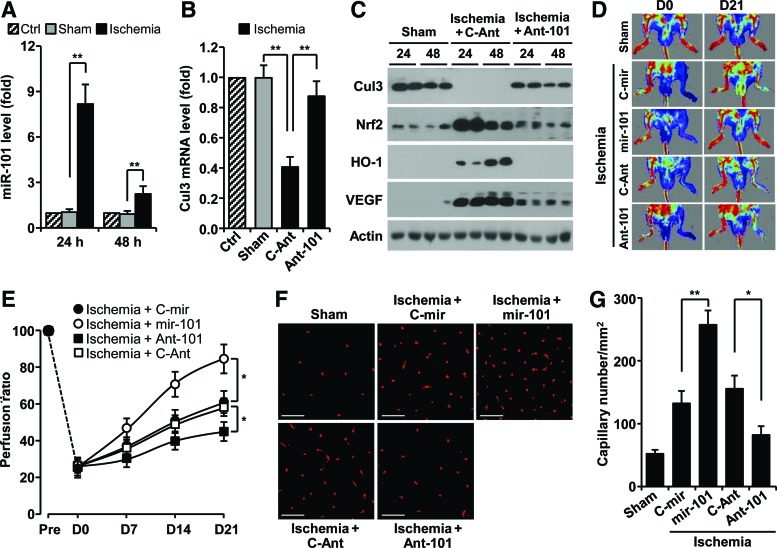

Hypoxia-responsive miR-101 promotes neovascularization

We next examined whether miR-101 expression is regulated in a mouse hindlimb ischemia model. The levels of miR-101 were increased about eight and twofold in gastrocnemius muscles harvested at 24 and 48 h after femoral artery ligation, compared with those of sham-operated muscles (Fig. 6A). As expected, the levels of Cul3 mRNA and protein were effectively decreased in ligated hindlimb muscles compared with sham tissues (Fig. 6B, C). However, the protein levels of Nrf2, HO-1, and VEGF were dramatically increased in ligated tissues (Fig. 6C). These expressional changes were restored by treatment with antagomiR-101 (Fig 6B, C). We further examined the in vivo role of hypoxia-responsive miR-101 in neovascularization and blood flow after hindlimb ischemia. Mice treated with mir-101-expressing lentivirus demonstrated significantly improved blood flow in ischemic hindlimbs compared with mir-control lentivirus-transfected mice (Fig. 6D, E). In contrast, mice treated with antagomiR-101 showed impaired perfusion recovery in the ischemic hindlimb compared with control animals treated with control antagomiR (Fig. 6D, E). Consistent with improved perfusion recovery, ischemic muscle from miR-101-treated mice showed higher capillary density than mock-treated mice (Fig. 6F, G). Moreover, treatment with antagomiR-101 reduced the number of capillaries in the ischemic hindlimb. Taken together, our results demonstrate that miR-101 promoted functional angiogenesis and was associated with significantly improved blood perfusion after hindlimb ischemia.

FIG. 6.

Hypoxia-responsive miR-101 increases neovascularization and blood flow recovery in ischemic mouse hindlimbs. (A, B) Gastrocnemius muscles were harvested from femoral artery-ligated and shamed mice at 24 and 48 h after surgery. Levels of miR-101 (A) and Cul3 mRNA (B) were determined by qRT-PCR (n=5 mice per group). (C) Cul3, Nrf2, HO-1, and VEGF representative protein levels were determined by Western blotting. (D–G) Mice were subjected to femoral artery ligation, followed by injection with lentivirus containing mir-101 or control mir (C-mir), antagomiR-101 (Ant-101), or control antigomiR (C-Ant) (n=5 per group). (D) Representative laser-Doppler perfusion imaging of mice at day 0 and 21 after hindlimb ischemia. (E) Blood flow recovery was quantitated. (F) Representative immunofluorescent images show CD31-positive capillaries in transverse sections of gastrocnemius muscles from ischemic mouse hindlimbs. Scale bars: 50 μm. (G) Quantitation of vessel density. Data shown in graphs represent the mean±SD. *p<0.05 and **p<0.01. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Discussion

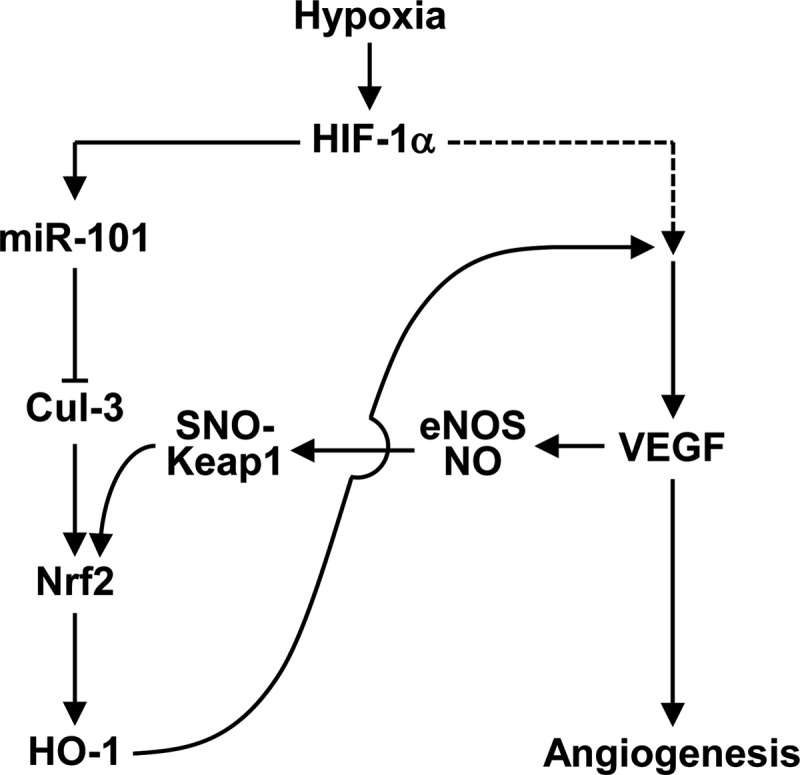

Several hypoxia- or ischemia-responsive miRNAs, including Let-7 and miRs-93/103/107/210/424 (13, 27, 30, 39), are known to play an important physiological role in post-ischemic vascular remodeling and angiogenesis. Unfortunately, there is still limited information on the role of miRNAs in ischemia-associated vascular homeostasis and diseases. A previous study provided the possibility that hypoxia can increase miR-101 expression in ECs compared with normoxic cells using array analysis (27). However, its expressional regulation and function have not been elucidated. In this study, we identified an important role of hypoxia-responsive miR-101 in promoting angiogenesis and blood perfusion. The conclusion of a novel role of miR-101 is supported by several lines of evidence. First, we provide data that miR-101 is upregulated both in vitro and in vivo in response to hypoxia and increases VEGF expression. The expression of VEGF is associated with HO-1 upregulation via activation of the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway by targeting the 3′UTR of Cul3. Second, our data show that an miR-101-mediated increase in VEGF expression is amplified via a positive feedback loop, where VEGF-induced S-nitrosylation of Keap1 promotes Nrf2-dependent HO-1 induction. Finally, our in vitro experiments show that miR-101 improves angiogenic behavior of ECs via activation of VEGF-mediated angiogenic signal cascades. In vivo, we confirmed the role of miR-101 in angiogenesis and hemodynamic recovery in a mouse hindlimb ischemia model. Based on these findings, we identify miR-101 as a novel angiomiR, which promotes neovascularization via a positive circuit between HO-1/CO and VEGF/eNOS/NO axis by targeting Cul3 (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Schematic diagram demonstrating miR-101 promotion of angiogenesis. Hypoxia elevates the expression of miR-101, which binds to the 3′UTR of Cul3 mRNA. A reduction of Cul3 level activates Nrf2/HO-1 axis and then degrades heme to produces CO, biliverdin, and bilirubin. These products lead to HIF-1α stabilization and VEGF expression. There is a positive feedback circuit to amplify the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway via VEGF/eNOS/NO-dependent S-nitrosylation of Keap1. CO, carbon monoxide.

Although increasing evidence indicates that several miRNAs play an important role in vascular homeostasis and angiogenesis, the molecular targets and biological functions of only a few angiomiRs are identified in ECs and non-ECs (11, 58). One main hurdle that has limited the determination of a specific miRNA function is the difficulty of identifying determinant target genes. The first identified target of miR-101 is EZH2, a tumor suppressor that functions as a negative regulator of a mammalian histone methyltransferase. The miR-101 locus is somatically lost in some solid tumors, leading to overexpression of EZH2 and concomitant dysregulation of epigenetic pathways to promote tumor progression (54, 56). Recently, miR-101 induced in human breast tumor MCF-7 cells by starvation and etoposide was shown to specifically downregulate several autophagic genes, including STMN1, ATG4D, and RAB5A, leading to an efficient decrease of tumor cell autophagy (25). Interestingly, contradictory reports show that under hypoxic conditions, miR-101 can be increased in ECs (27) and downregulated in squamous cell carcinoma (39). However, our data demonstrate that miR-101 was effectively induced in response to hypoxia, particularly in an HIF-1α-dependent manner, in ECs compared with other cell types. Thus, the mechanism for miR-101 function and expression is mediated by a diverse range of targets and transcriptional machinery that likely vary depending on the cell type and environmental setting.

Here, we have found new potential target genes, including Cul3, Cul4B, and Cul5, for hypoxia-responsive miR-101 by performing in silico analysis using algorithm of TargetScan (Supplementary Fig. S1B). Cullin family proteins consisting of seven members are molecular scaffolds for E3 ligase, which play diverse and essential roles in many biological processes via mediating ubiquitination of target proteins. Crucial substrates of Cul3, Cul4B, and Cul5 are identified as Nrf2, CDT1, and EPAS1, which are involved in phase II gene expression, chromatin regulation, and cartilage destruction, respectively (21, 59). In fact, functional inhibition of Cul3 effectively stabilizes the transcription factor Nrf2 (21). Importantly, a wide range of evidence shows that Nrf2 is an important transcription factor for phase II genes, including HO-1, which promotes angiogenesis and survival of ECs by increasing VEGF expression (32, 33). Here, we provide evidence that hypoxia-inducible miR-101 inhibits Cul3 expression by directly targeting its 3′UTR, leading to upregulation of Nrf2-mediated HO-1 expression and concomitant promotion of angiogenesis. Thus, this study demonstrates a signaling pathway that links miR-101 to Nrf2-dependent HO-1 expression via direct targeting of Cul3.

It is well established that expression of HO-1 is regulated by the Nrf2/Keap1/Cul3/Rbx1 E3 ligase complex. As mentioned earlier, Cul3 binds the RING domain protein Rbx1 that, in turn, recruits an E3 ligase, which facilitates Nrf2 ubiquitination and degradation. Dominant-negative Cul3 is unable to recruit E3 ligase and stabilize Nrf2, a transcription factor required for phase II genes (21, 38). Moreover, siRNA-mediated knockdown of Cul3 significantly increased Nrf2 protein levels and induced phase II enzymes (43). Of these enzymes, HO-1 catalyzes heme to produce CO, biliverdin, and bilirubin, which play important roles in preventing EC death and promoting angiogenesis (8). In this study, we identify hypoxia-responsive miR-101 as a new member of the angiomiR family. In fact, this miRNA promotes both in vitro and in vivo angiogenesis by activating the HO-1/HIF-α/VEGF axis via Cul3 targeting. In keeping with these findings, several lines of evidence also show that hypoxia and hemin (an inducer of HO-1) induce HO-1 expression and concomitant augmentation of VEGF production, which enhances EC proliferation and in vitro capillary formation (18, 32). In addition, hemin-induced VEGF production and angiogenesis were not elicited in normal ECs by co-treatment with the HO-1 inhibitor (20) or in ECs from HO-1−/− mice (16), strongly implicating a role of HO-1 byproducts in angiogenesis. The HO-1 reaction product, CO, promoted VEGF expression via translational activation and stabilization of the HIF-1α protein (14), and expression of VEGF by hypoxia was significantly blocked by inhibition of HO-1 activity (20, 32). These findings indicate that HO-1 is critically involved in hypoxia-induced VEGF production. In accordance with this view, the present study demonstrates that hypoxia-responsive miR-101 increases HIF-1α and VEGF protein levels, which were suppressed by HO-1 siRNA and an HO-1 inhibitor. In addition, our data show that miR-101 increased HIF-1α protein levels via HSP90-mediated HIF-1α stabilization and translational synthesis of HIF-1α, whose effects were associated with HO-1 induction and activity. Moreover, these results indicate that miR-101 is a typical angiomiR, which functions as a positive regulator of VEGF expression via HIF-1α activation by modulating the Cul3/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway.

The HO-1/CO pathway positively modulates HIF-1α-mediated VEGF synthesis and promotes angiogenesis via activation of several intracellular signal pathways, including PI3K/eNOS-derived NO production. Conversely, VEGF activates HO-1 via activation of Nrf2 (40). Since both CO and NO, produced from HO-1 and eNOS, respectively, share similar biological properties, such as the ability to regulate angiogenesis and vasodilation, it is now evident that both gaseous molecules do not always work independently, but rather can cross-modulate each other's biological activity in the vasculature. Although both molecules readily react with ferrous heme-iron, only NO modifies free cysteine residues to disulfide linkage or S-nitrosylation and also interacts with iron–sulfur clusters. NO can induce S-nitrosylation of critical cysteine residues in Keap1, which coincides with disruption of Nrf2 from the Keap1-Cul3 ubiquitination system (55). Although several mechanisms for VEGF-mediated Nfr2 activation have been proposed (23, 40), our data show that miR-101 elicits Keap1 S-nitrosylation, a crucial step of Nrf2-dependent HO-1 induction, which is associated with activation of the VEGF/eNOS axis (Fig. 7). These evidence suggest that miR-101 stimulates the angiogenic processes via a positive feedback loop between Nrf2/HO-1 and VEGF/eNOS/NO axes after initially targeting the 3′UTR of Cul3.

Angiogenesis is a physiological process that may also occur as a natural repair mechanism against ischemic diseases, such as ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, and peripheral arterial disease. Although several pro-angiomiRs have been identified (31, 58), there is still limited application to therapeutic angiogenesis. Previous reports point to the HO-1/VEGF/eNOS axis as one of the determinants of angiogenesis and improved blood flow in the ischemic hindlimb (40, 45). These data suggest that miRNAs activating this signaling axis can be used as potential therapeutic agents in patients with vascular obstructions. We confirmed the angiogenic function of miR-101 in a murine hindlimb ischemia model by gain- and loss-of-function experiments using exogenous miR-101 and its antagomiR. Indeed, mir-101 overexpression enhanced perfusion recovery via an increase in capillary density in the ischemic hindlimb. However, antagomiR-101 impaired angiogenic responses to ischemia. These data suggest that miR-101 promotes angiogenesis via activation of the HO-1/HIF-1α/VEGF signaling axis by directly targeting Cul3. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that a pro-angiogenic function of miR-101 can be associated with the regulation of other targets, because more than 30 genes can be regulated as determined by computational algorithms for miRNA target perfection. One of miR-101 target genes, Cul5 can regulate the post-translational stability of EPAS, which promotes VEGF expression. This possibility is currently under investigation.

In summary, our present findings demonstrate that miR-101 induced by hypoxia is an important regulator in vascular remodeling and angiogenesis. Increased miRNA-101 expression in hypoxic ECs and hindlimb muscles was identified as a novel mechanism contributing to angiogenesis by triggering HO-1/HIF-1α/VEGF signaling axis via negative expression of Cul3, a critical scaffold protein in the E3 ligase complex. Moreover, miR-101 improved neovascularization and blood flow recovery in the ischemic hindlimb. Therefore, hypoxia-responsive miR-101 may provide a potential therapeutic avenue for the treatment of ischemia-related diseases. Importantly, this angiogenic modulation is a potential novel mechanism independent of canonical (oxygen-dependent) HIF-1α-mediated angiogenic pathway.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid construction

To generate the pre-miR-101 or control pre-miR expression vectors, oligonucleotides of human pre-miR-101 and control pre-miR were purchased from Bioneer and cloned into BamHI and HindIII sites of pSilencer 2.1-U6 (Invitrogen). The 3′UTR (∼0.5 kb) of Cul3 was prepared using human genomic DNA by PCR using the following primers, 5′-CGGCCTCGAGATTCTTGTCAGATATCCTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-AATGCGGCCGCACACCTGACTTAGGTACTA-3′ (reverse). The PCR product was ligated at the XhoI and NotI sites of psiCHECK™-2 vector (Promega). The luciferase reporter vectors, pGL3-HO-1-Luc and pGL3-VEGF-Luc, were used for promoter activity assay (14, 36).

Cell culture and treatment

HUVECs were cultured as previously described (36). Cells were transfected with 1 μg/ml of expression vectors (pSilencer 2.1-U6/pre-miR-101, pSilencer 2.1-U6/control pre-miR, psiCHECK™-2/Cul3 3′UTR, psiCHECK™-2/Cul3 3′UTR mutant 1, psiCHECK™-2/Cul3 3′UTR mutant 2, pGL3-HO-1-Luc, pGL3-VEGF-Luc, and p3xFLAG-CMV10-Cul3) and 100 nM of siRNA targeted to HO-1 or Nrf2 or Cul3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), miR-101 (Qiagen), control miRNA (Qiagen), or antagomiR-101 (Bioneer) using a microporator (NanoEnTek) or Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen) for 24 h and treated with or without 20 μM SnPP (Frontier Scientific), 1 mM L-NAME (Sigma-Aldrich), or 0.5 μg/ml VEGF-neutralizing antibody (R&D Systems) to VEGF for 12 h. The cells were used for further analyses.

Hypoxia treatment

Cells were maintained in a hypoxic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products, Inc.) flushed with a gas mixture containing 94% N2 and 5% CO2. Under these conditions, O2 levels in the medium were determined to be 2±1%.

In vitro angiogenic assays

HUVECs were transfected with pSilencer 2.1-U6/mir-101 or in combination with HO-1 siRNA, followed by treatment with SnPP and a VEGF neutralizing antibody. Proliferation, migration, and tube formation of HUVECs were carried out as previously described (41).

Ex vivo aortic ring and Matrigel plug assays

All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Kangwon National University. Aortic rings from 7-week-old female C57BL/6J wild-type, eNOS−/−, and HO-1+/− mice (Jackson Laboratory) were transduced with lentivirus carrying either mir-101 or control mir (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and incubated at 37°C for 18 days. Aortic ring sprouts were photographed using a microscope that was equipped with a digital camera. For a quantitative assessment of sprouting, the area of sprouting per millimeter of tissue was assessed using Image J software (NIH; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij). For Matrigel plug assay, HUVECs were transduced with lentivirus carrying either pre-miR-101 or control pre-miR (MOI=4) and mixed with Matrigel (BD Bioscience). Matrigel (400 μl) containing 1×106 cells was then subcutaneously implanted into nude mice (7-week-old females). Matrigel plugs were removed after 7 days and photographed with a digital microscope.

PCR analysis

miRNAs were isolated using an miRNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocols. cDNA for determining miRNAs were obtained from 1 μg of miRNAs using a miScript II RT kit. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed with miScript SYBR Green PCR kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. The miR-101 level was analyzed by miScript primer assay using a target miR-101-specific primer and universal primer (Qiagen). In addition, the Cul3 mRNA expression levels were determined by iTaqTM SYBR Green Supermix with ROX (BioRad) with ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystem). The following sets of primers were used: 5′-GTGGTAAACCAACACAGCGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGGTCGGATTCACCTTGTTT-3′ (reverse) for Cul3; 5′-CGCCACAGTTTCCCGGAGGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCCTCCAAAATCAAGTGGGG-3′ (reverse) for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). The fold change of miR-101 and Cul3 mRNA was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method as previously described (42). For reverse transcription PCR analysis, total RNAs were isolated from the indicated cells using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). RT-PCR analysis was performed as previously described (14). The following sets of primers were used: 5′-AGTCGGACAGCCTCAC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGCTGCCTTGTATAGGA-3′ (reverse) for human HIF-1α; 5′-CAGGCAGAGAATGCTGAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCTTCACATAGCGCTGCA-3′ (reverse) for human HO-1; 5′-GAGAATTCGGCCTCCGAAACCATGAACTTTCTGT-3′ (forward) and 5′-GAGCATGCCCTCCTGCCCGGCTCACCGC-3′ (reverse) for VEGF; 5′-CAGGGCTGCTTTTAACTCTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TAGAGGCAGGGATGATGTTC-3′ (reverse) for GAPDH. PCR products were analyzed on 1.2% agarose gels.

Luciferase assay

HUVECs were transfected with psiCHECK™-2 vector containing the Cul3 3′UTR region as well as antagomiR-101 or negative control antagomiR for 24 h and were maintained under normoxia or hypoxia for 12 h. Promoter activity was assayed using a dual-luciferase report assay kit (Promega). Cells were also transfected with pGL3-HO-1-Luc (or pGL3-VEGF-Luc) or in combination with pSilencer 2.1-U6/pre-miR-101 (mir-101), pSilencer 2.1-U6/control pre-miR (C-mir), p3xFLAG-CMV10-Cul3, Cul3 siRNA, HO-1 siRNA, or control siRNA for 24 h, followed by treatment with SnPP, L-NAME, and a VEGF neutralizing antibody for 12 h. Luciferase activity was assayed using a luciferase assay system.

ChIP assay

ChIP assay was performed as previously described (36). Briefly, DNA/protein cross-linking was obtained in HUVECs by incubating cells for 20 min at 37°C in 1% formaldehyde. After sonication, chromatin was immunoprecipitated overnight with 10 μl of anti-Nrf2 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Targeted promoter sequences of HO-1 were identified by PCR (150 bp, 30 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s) using primer pairs spanning HO-1-specific promoter regions containing the antioxidant response element-binding sequence. The products (150 bp) were identified on a 2% agarose gel. The primer sequences are as follows: 5′-GGGATTAAACCTGGAGCAGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TTTTTCCTGCTGAGTCACGG-3′ (reverse) for HO-1.

Immunoprecipitation

Cellular proteins from HUVECs were incubated with an antibody for Keap1 or Nrf2 in RIPA buffer with constant rotation overnight at 4°C. Cell lysates were incubated with antibodies against Keap1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Nrf2, HIF-1α (Novus Biologicals), and HSP90 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and immune complexes were collected by centrifugation after incubation with an antibody against protein G-Sepharose (Millipore). Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacryl amide gel electrophoresis, followed by Western blot analysis using the indicated antibodies.

Biochemical analyses

Western blot analysis for target proteins in whole-cell lysates as well as cytosolic and nuclear fractions was performed as previously described (36). S-nitrosylation of Keap1 was measured by an S-nitrosylated protein detection kit (Cayman) according to the manufacturer's protocols. The intracellular NO level was measured by using 4-amino-5-methylamino-2′,7′-difluorofluorescein diacetate (Molecular Probes) according to a previous protocol (15). PHD activity was assayed by determing the interaction between [35S]methionine-labeled VHL protein and purified glutathione S-transferase-oxygen-dependent degradation domain (amino acids 401–603 of human HIF-1α) that was preincubated with cell lysates as previously described (14). Hemoglobin was measured using the Drabkin reagent kit 525 (Sigma-Aldrich) to quantify blood vessel formation in Matrigel plugs.

Immunohistochemistry and vascular density

HUVECs were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature, washed gently, and permeabilized with 0.1% saponin. Cells were incubated with antibodies (1:100) against Nrf2 and HIF-1α for 2 h and then incubated with Alexa Fluor antibody (1:200; Invitrogen). For nuclear staining, cells were further incubated for 30 min with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (1 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich). After mounting, nuclear translocation of transcription factors was observed by confocal microscopy. For measurement of vascular density, the gastrocnemius muscles were dissected out from ischemic mouse hindlimbs, and coronal sections (10 μm) were fixed with formalin, processed, and stained for blood vessels with Texas Red-conjugated mouse CD31 antibody (DB Pharmingen).

Polysome assay

Polysome analysis was performed as previously described (14). HUVECs were lysed in 400 μl lysis buffer. After centrifugation at 2000 g for 5 min, the supernatant was added to heparin (a broad-range RNase inhibitor) at a final concentration of 200 μg/ml. After removing debris by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 5 min, the cytoxolic supernatants were laid on a 20–50% sucrose gradient (total volume: 5 ml), and centrifuged at 39,000 rpm for 120 min in Beckman SW-55Ti rotor at 4°C. Fractions (0.2 ml) were collected and monitored for absorbance at 254 nm. RNA was isolated from pooled polysome fractions from 16 to 22, and HIF-1α mRNA levels were analyzed by qRT-PCR.

Hindlimb ischemia

Lentivirus carrying either control pre-miR or pre-miR-101 and antagomiR-101 were delivered into the right gastrocnemius muscle of 8-week-old female C57Bl/6J mice by three injections (total 2.5×106 virus particles in 50 μl/mouse and total 8 mg/kg of antagomiR-101 or control antagomiR) under anesthesia with ketamine (100 mg/kg) und xylazine (2 mg/kg). After 30 min, unilateral femoral artery occlusion was performed by double ligation of the superficial femoral artery proximal to the deep femoral artery and distal femoral artery. Mice were also i.v. injected with 8 mg/kg of antagomiR-101 at days 3 and 7 after hindlimb ischemia. Sham-operated control animals were subjected to the same surgical protocol, but the femoral artery was not ligated. Blood flow in both hindlimbs was determined by laser-Doppler perfusion imaging (Moor Instruments). Flow ratios of the occluded/nonoccluded leg were compared between experimental groups. The gastrocnemius muscles were surgically removed for miR-101 analysis, target gene expression, and immunohistochemistry.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data are expressed as the mean±standard deviation of at least three separate experiments. Statistical significance was determined using either one-way analysis of variance or unpaired Student's t test, depending on the number of experimental groups analyzed. Significance was established at a p-value<0.05.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- 3′UTR

3′untranslated region

- AC

astrocyte

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- CO

carbon monoxide

- Cul

cullin

- EC

endothelial cell

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GST-ODD

glutathione S-transferase-oxygen-dependent degradation

- HBMECs

human brain microvascular endothelial cells

- HIF-1α

hypoxia-inducible factor-1α

- HO-1

heme oxygenase-1

- HSP90

heat shock protein 90

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- Keap1

kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1

- L-NAME

NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester

- miRNA, miR

microRNA

- NO

nitric oxide

- Nrf2

nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2-related factor 2

- PHD

prolyl hydroxylase domain protein

- pre-miR

precursor miR-101

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- RBC

red blood cell

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- SD

standard deviation

- SnPP

tin-protoporphyrin IX

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VHL

von Hippel-Lindau

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (NRF-2011-0028790). The authors thank Dr. Elaine Por for helpful comments and a critical reading of this article.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Adams RH. and Alitalo K. Molecular regulation of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 464–478, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anand S, Majeti BK, Acevedo LM, Murphy EA, Mukthavaram R, Scheppke L, Huang M, Shields DJ, Lindquist JN, Lapinski PE, King PD, Weis SM, and Cheresh DA. MicroRNA-132-mediated loss of p120RasGAP activates the endothelium to facilitate pathological angiogenesis. Nat Med 16: 909–914, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116: 281–297, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136: 215–233, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonauer A, Carmona G, Iwasaki M, Mione M, Koyanagi M, Fischer A, Burchfield J, Fox H, Doebele C, Ohtani K, Chavakis E, Potente M, Tjwa M, Urbich C, Zeiher AM, and Dimmeler S. MicroRNA-92a controls angiogenesis and functional recovery of ischemic tissues in mice. Science 324: 1710–1713, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boon RA, Iekushi K, Lechner S, Seeger T, Fischer A, Heydt S, Kaluza D, Tréguer K, Carmona G, Bonauer A, Horrevoets AJ, Didier N, Girmatsion Z, Biliczki P, Ehrlich JR, Katus HA, Müller OJ, Potente M, Zeiher AM, Hermeking H, and Dimmeler S. MicroRNA-34a regulates cardiac ageing and function. Nature 495: 107–110, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bridge G, Monteiro R, Henderson S, Emuss V, Lagos D, Georgopoulou D, Patient R, and Boshoff C. The microRNA-30 family targets DLL4 to modulate endothelial cell behavior during angiogenesis. Blood 120: 5063–5072, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bussolati B. and Mason JC. Dual role of VEGF-induced heme-oxygenase-1 in angiogenesis. Antioxid Redox Signal 8: 1153–1163, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caporali A. and Emanueli C. MicroRNA regulation in angiogenesis. Vascul Pharmacol 55: 79–86, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in life, disease and medicine. Nature 438: 932–936, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chamorro-Jorganes A, Araldi E, and Suárez Y. MicroRNAs as pharmacological targets in endothelial cell function and dysfunction. Pharmacol Res 75: 15–27, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen K, Fan W, Wang X, Ke X, Wu G, and Hu C. MicroRNA-101 mediates the suppressive effect of laminar shear stress on mTOR expression in vascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 427: 138–142, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Z, Lai TC, Jan YH, Lin FM, Wang WC, Xiao H, Wang YT, Sun W, Cui X, Li YS, Fang T, Zhao H, Padmanabhan C, Sun R, Wang DL, Jin H, Chau GY, Huang HD, Hsiao M, and Shyy JY. Hypoxia-responsive miRNAs target argonaute 1 to promote angiogenesis. J Clin Invest 123: 1057–1067, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi YK, Kim CK, Lee H, Jeoung D, Ha KS, Kwon YG, Kim KW, and Kim YM. Carbon monoxide promotes VEGF expression by increasing HIF-1α protein level via two distinct mechanisms, translational activation and stabilization of HIF-1α protein. J Biol Chem 285: 32116–32125, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung BH, Kim S, Kim JD, Lee JJ, Baek YY, Jeoung D, Lee H, Choe J, Ha KS, Won MH, Kwon YG, and Kim YM. Syringaresinol causes vasorelaxation by elevating nitric oxide production through the phosphorylation and dimerization of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Exp Mol Med 44: 191–201, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cisowski J, Loboda A, Józkowicz A, Chen S, Agarwal A, and Dulak J. Role of heme oxygenase-1 in hydrogen peroxide-induced VEGF synthesis: effect of HO-1 knockout. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 326: 670–676, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coultas L, Chawengsaksophak K, and Rossant J. Endothelial cells and VEGF in vascular development. Nature 438: 937–945, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deramaudt BM, Braunstein S, Remy P, and Abraham NG. Gene transfer of human heme oxygenase into coronary endothelial cells potentially promotes angiogenesis. J Cell Biochem 68: 121–127, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dews M, Homayouni A, Yu D, Murphy D, Sevignani C, Wentzel E, Furth EE, Lee WM, Enders GH, Mendell JT, and Thomas-Tikhonenko A. Augmentation of tumor angiogenesis by a Myc-activated microRNA cluster. Nat Genet 38: 1060–1065, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dulak J, Józkowicz A, Foresti R, Kasza A, Frick M, Huk I, Green CJ, Pachinger O, Weidinger F, and Motterlini R. Heme oxygenase activity modulates vascular endothelial growth factor synthesis in vascular smooth muscle cells. Antioxid Redox Signal 4: 229–240, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emanuele MJ, Elia AE, Xu Q, Thoma CR, Izhar L, Leng Y, Guo A, Chen YN, Rush J, Hsu PW, Yen HC, and Elledge SJ. Global identification of modular cullin-RING ligase substrates. Cell 147: 459–474, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eulalio A, Mano M, Dal Ferro M, Zentilin L, Sinagra G, Zacchigna S, and Giacca M. Functional screening identifies miRNAs inducing cardiac regeneration. Nature 492: 376–381, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernandez M. and Bonkovsky HL. Vascular endothelial growth factor increases heme oxygenase-1 protein expression in the chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane. Br J Pharmacol 139: 634–640, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fiedler J, Jazbutyte V, Kirchmaier BC, Gupta SK, Lorenzen J, Hartmann D, Galuppo P, Kneitz S, Pena JT, Sohn-Lee C, Loyer X, Soutschek J, Brand T, Tuschl T, Heineke J, Martin U, Schulte-Merker S, Ertl G, Engelhardt S, Bauersachs J, and Thum T. MicroRNA-24 regulates vascularity after myocardial infarction. Circulation 124: 720–730, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frankel LB, Wen J, Lees M, Høyer-Hansen M, Farkas T, Krogh A, Jäättelä M, and Lund AH. MicroRNA-101 is a potent inhibitor of autophagy. EMBO J 30: 4628–4641, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fukumura D, Gohongi T, Kadambi A, Izumi Y, Ang J, Yun CO, Buerk DG, Huang PL, and Jain RK. Predominant role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenesis and vascular permeability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98: 2604–2609, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghosh G, Subramanian IV, Adhikari N, Zhang X, Joshi HP, Basi D, Chandrashekhar YS, Hall JL, Roy S, Zeng Y, and Ramakrishnan S. Hypoxia-induced microRNA-424 expression in human endothelial cells regulates HIF-α isoforms and promotes angiogenesis. J Clin Invest 120: 4141–4154, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanahan D. and Folkman J. Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell 86: 353–364, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hassel D, Cheng P, White MP, Ivey KN, Kroll J, Augustin HG, Katus HA, Stainier DY, and Srivastava D. MicroRNA-10 regulates the angiogenic behavior of zebrafish and human endothelial cells by promoting vascular endothelial growth factor signaling. Circ Res 111: 1421–1433, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hazarika S, Farber CR, Dokun AO, Pitsillides AN, Wang T, Lye RJ, and Annex BH. MicroRNA-93 controls perfusion recovery after hindlimb ischemia by modulating expression of multiple genes in the cell cycle pathway. Circulation 127: 1818–1828, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jakob P, Doerries C, Briand S, Mocharla P, Kränkel N, Besler C, Mueller M, Manes C, Templin C, Baltes C, Rudin M, Adams H, Wolfrum M, Noll G, Ruschitzka F, Lüscher TF, and Landmesser U. Loss of angiomiR-126 and 130a in angiogenic early outgrowth cells from patients with chronic heart failure: role for impaired in vivo neovascularization and cardiac repair capacity. Circulation 126: 2962–2975, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jazwa A, Loboda A, Golda S, Cisowski J, Szelag M, Zagorska A, Sroczynska P, Drukala J, Jozkowicz A, and Dulak J. Effect of heme and heme oxygenase-1 on vascular endothelial growth factor synthesis and angiogenic potency of human keratinocytes. Free Radic Biol Med 40: 1250–1263, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jazwa A, Stepniewski J, Zamykal M, Jagodzinska J, Meloni M, Emanueli C, Jozkowicz A, and Dulak J. Pre-emptive hypoxia-regulated HO-1 gene therapy improves post-ischaemic limb perfusion and tissue regeneration in mice. Cardiovasc Res 97: 115–124, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaelin WG, Jr., and Ratcliffe PJ. Oxygen sensing by metazoans: the central role of the HIF hydroxylase pathway. Mol Cell 30: 393–402, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katare R, Riu F, Mitchell K, Gubernator M, Campagnolo P, Cui Y, Fortunato O, Avolio E, Cesselli D, Beltrami AP, Angelini G, Emanueli C, and Madeddu P. Transplantation of human pericyte progenitor cells improves the repair of infarcted heart through activation of an angiogenic program involving micro-RNA-132. Circ Res 109: 894–906, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim JH, Choi YK, Lee KS, Cho DH, Baek YY, Lee DK, Ha KS, Choe J, Won MH, Jeoung D, Lee H, Kwon YG, and Kim YM. Functional dissection of Nrf2-dependent phase II genes in vascular inflammation and endotoxic injury using Keap1 siRNA. Free Radic Biol Med 53: 629–640, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klagsbrun M. and Soker S. VEGF/VPF: the angiogenesis factor found? Curr Biol 3: 699–702, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kobayashi A, Kang MI, Okawa H, Ohtsuji M, Zenke Y, Chiba T, Igarashi K, and Yamamoto M. Oxidative stress sensor Keap1 functions as an adaptor for Cul3-based E3 ligase to regulate proteasomal degradation of Nrf2. Mol Cell Biol 24: 7130–7139, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kulshreshtha R, Davuluri RV, Calin GA, and Ivan M. A microRNA component of the hypoxic response. Cell Death Differ 15: 667–671, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kweider N, Fragoulis A, Rosen C, Pecks U, Rath W, Pufe T, and Wruck CJ. Interplay between vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor-2 (Nrf2): implications for preeclampsia. J Biol Chem 286: 42863–43872, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee SJ, Namkoong S, Kim YM, Kim CK, Lee H, Ha KS, Chung HT, Kwon YG, and Kim YM. Fractalkine stimulates angiogenesis by activating the Raf-1/MEK/ERK- and PI3K/Akt/eNOS-dependent signal pathways. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H2836–H2846, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Livak KJ. and Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−ΔΔCt) method. Methods 25: 402–408, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loignon M, Miao W, Hu L, Bier A, Bismar TA, Scrivens PJ, Mann K, Basik M, Bouchard A, Fiset PO, Batist Z, and Batist G. Cul3 overexpression depletes Nrf2 in breast cancer and is associated with sensitivity to carcinogens, to oxidative stress, and to chemotherapy. Mol Cancer Ther 8: 2432–2440, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maines MD. The heme oxygenase system: a regulator of second messenger gases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 37: 517–554, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murohara T, Asahara T, Silver M, Bauters C, Masuda H, Kalka C, Kearney M, Chen D, Symes JF, Fishman MC, Huang PL, and Isner JM. Nitric oxide synthase modulates angiogenesis in response to tissue ischemia. J Clin Invest 101: 2567–2578, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nicoli S, Standley C, Walker P, Hurlstone A, Fogarty KE, and Lawson ND. MicroRNA-mediated intergration of haemodynamics and Vegf signaling during angiogenesis. Nature 464: 1196–1200, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ooi A, Dykema K, Ansari A, Petillo D, Snider J, Kahnoski R, Anema J, Craig D, Carpten J, Teh BT, and Furge KA. CUL3 and NRF2 mutations confer an NRF2 activation phenotype in a sporadic form of papillary renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res 73: 2044–2051, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patella F, Leucci E, Evangelista M, Parker B, Wen J, Mercatanti A, Rizzo M, Chiavacci E, Lund AH, and Rainaldi G. MiR-492 impairs the angiogenic potential of endothelial cells. J Cell Mol Med 17: 1006–1015, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poliseno L, Tuccoli A, Mariani L, Evangelista M, Citti L, Woods K, Mercatanti A, Hammond S, and Rainaldi G. MicroRNAs modulate the angiogenic properties of HUVECs. Blood 108: 3068–3071, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schulman IH. and Hare JM. Regulation of cardiovascular cellular processes by S-nitrosylation. Biochem Biophys Acta 1820: 752–762, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) pathway. Sci STKE 2007: cm8, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sikorski EM, Hock T, Hill-Kapturczak N, and Agarwal A. The story so far: molecular regulation of the heme oxygenase-1 gene in renal injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F425–F441, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spinetti G, Fortunato O, Caporali A, Shantikumar S, Marchetti M, Meloni M, Descamps B, Floris I, Sangalli E, Vono R, Faglia E, Specchia C, Pintus G, Madeddu P, and Emanueli C. MicroRNA-15a and microRNA-16 impair human circulating proangiogenic cell functions and are increased in the proangiogenic cells and serum of patients with critical limb ischemia. Circ Res 112: 335–346, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Su H, Yang JR, Xu T, Huang J, Xu L, Yuan Y, and Zhuang SM. MicroRNA-101, down-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma, promotes apoptosis and suppresses tumorigenicity. Cancer Res 69: 1135–1142, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Um HC, Jang JH, Kim DH, Lee C, and Surh YJ. Nitric oxide activates Nrf2 through S-nitrosylation of Keap1 in PC12 cells. Nitric Oxide 25: 161–168, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Varambally S, Cao Q, Mani RS, Shankar S, Wang X, Ateeq B, Laxman B, Cao X, Jing X, Ramnarayanan K, Brenner JC, Yu J, Kim JH, Han B, Tan P, Kumar-Sinha C, Lonigro RJ, Palanisamy N, Maher CA, and Chinnaiyan AM. Genomic loss of microRNA-101 leads to overexpression of histone methyltransferase EZH2 in cancer. Science 322: 1695–1699, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang R, Zhao N, Li S, Fang JH, Chen MX, Yang J, Jia WH, Yuan Y, and Zhuang SM. MicroRNA-195 suppresses angiogenesis and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma by inhibiting the expression of VEGF, VAV2 and CDC42. Hepatology 58: 641–653, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang S. and Olson EN. AngiomiRs—key regulators of angiogenesis. Curr Opin Genet Dev 19: 205–211, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang S, Kim J, Ryu JH, Oh H, Chun CH, Kim BJ, Min BH, and Chun JS. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2α is a catabolic regulator of osteoarthritic cartilage destruction. Nat Med 16: 687–693, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.