Abstract

Introduction

The association between aerobic physical activity volume and bone mineral density (BMD) is not completely understood. The purpose of this study was to clarify the association between BMD and aerobic activity across a broad range of activity volumes, in particular volumes between those recommended in the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans and those of trained endurance athletes.

Methods

Data from the 2007–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey were used to quantify the association between reported physical activity and BMD at the lumbar spine and proximal femur across the entire range of activity volumes reported by US adults. Participants were categorized into multiples of the minimum guideline-recommended volume based on reported moderate and vigorous intensity leisure activity. Lumbar and proximal femur BMD was assessed with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.

Results

Among women, multivariable-adjusted linear regression analyses revealed no significant differences in lumbar BMD across activity categories, while proximal femur BMD was significantly higher among those who exceeded guidelines by 2–4 times than those who reported no activity. Among men, multivariable-adjusted BMD at both sites neared its highest values among those who exceeded guidelines by at least 4 times and was not progressively higher with additional activity. Logistic regression estimating the odds of low BMD generally echoed the linear regression results.

Conclusion

The association between physical activity volume and BMD is complex. Among women, exceeding guidelines by 2–4 times may be important for maximizing BMD at the proximal femur, while among men, exceeding guidelines by 4+ times may be beneficial for lumbar and proximal femur BMD.

Keywords: Epidemiology, general population research, exercise, DXA

Introduction

Conditions characterized by low bone mass or bone mineral density (BMD), such as osteoporosis and osteopenia, increase the risk for fractures (23). Fractures are an important public health issue, especially in the aging population, because of poor prognosis and incomplete recovery (5). In the United States (US), 52% of adults older than 50 years have low bone mass at the femoral neck or lumbar spine (defined as BMD >1 SD below the mean for young women). Further, 9% meet the diagnostic criteria for osteoporosis at one or both sites (defined as BMD ≥ 2.5 SD below the mean for young women) (23).

BMD is an important indicator of skeletal health, integrity, and strength. A recent expert review panel concluded that higher BMD is among the many health benefits of vigorous and moderate-intensity physical activity, and this applies to both aerobic- and resistance-type activities (24). In children, high-impact physical activity aids bone mineral accrual, which may have positive implications for lifetime skeletal health (12). Among adults, participation in activity at or near levels recommended in the US Department of Health and Human Services’ 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (28) (henceforth: physical activity guidelines) can attenuate age-related decreases in BMD and, optimally, increase BMD 1–2% per year (3). Hence, physical activity is an important modifiable risk factor for skeletal health.

Research among endurance athletes suggests that the dose-response relation between aerobic physical activity volume and BMD is not monotonic. Unlike resistance training, where even international-level weight lifters have demonstrated very high BMDs (18, 24), trained endurance athletes have demonstrated lower BMD versus less-active control subjects (6, 14, 26), and measurable bone mineral losses have been reported during competitive seasons (2, 20). Importantly, longitudinal reductions in BMD have been observed in weight-supported (2) and weight-bearing endurance sports (20) practiced at high aerobic intensities, suggesting a mechanism other than insufficient bone-loading forces is responsible for observed BMD decreases. Various proposed mechanisms include suppression of the pituitary-gonadal axis due to low energy availability, elevated stress hormones in the face of high training volume, and increased inflammation due to repeated exercise stimuli (2). Further, calcium loss through sweating and the resulting decrease in blood calcium may be an important factor for low BMD with high exercise loads (2, 20). As a homeostatic challenge, low blood calcium is countered by parathyroid hormone release, which activates bone resorption by the osteoclasts. This releases constituent minerals into the circulation and normalizes blood calcium levels. Notably, this mechanism could be at play during any prolonged, sweat-producing activity, regardless of aerobic intensity or impact, meaning that total activity volume may be important.

Physical activity volume is the product of duration, intensity, and frequency and can be conceptualized as a continuum. There is a void of information on the effects of aerobic physical activity on skeletal health at volumes between those observed in clinical trials (often near the physical activity guidelines and beneficial for skeletal health) and those observed in endurance athletes (far exceeding the guidelines and potentially detrimental for skeletal health). There are no population-based studies that could identify a particular physical activity volume beyond which progressively higher BMD is not observed. If such a point is identified, it could inform future physical activity guidelines and athlete care. Therefore, the purpose of this research is twofold: to quantify lumbar and proximal femur BMD across a range of reported physical activity volumes among adult respondents in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 2007–2010; and to quantify the site-specific relative odds of low BMD (T-score ≤ −1) across physical activity categories.

Methods

Data Source

Data from the 2007–2008 and 2009–2010 NHANES were used for these analyses (9, 10). To avoid differences in BMD due to maturation and better isolate the activity-BMD association, these analyses were restricted to adults 20 years or older. Information regarding NHANES sampling and data collection is publicly available from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Briefly, NHANES is an ongoing cross-sectional survey that uses multistage, stratified, probability sampling to obtain a representative sample of the non-institutionalized US population. Data are continuously collected and released on two-year intervals. Participants have in-home interviews and are invited to a medical examination at a mobile center. All NHANES procedures are approved by the research ethics board of the NCHS, and all participants agree by means of informed consent. The present analyses were reviewed and declared exempt from oversight by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Variables

Dependent variable 1: BMD

Bone mineral density was assessed using dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) Full information regarding NHANES femoral and vertebral DXA eligibility, protocol, and quality control is publicly available for the 2007–2010 cycles (9, 10). Briefly, respondents 8 years and older, who were not pregnant, had no recent contrast media or nuclear medicine scans, and weighed no more than 300 lbs were eligible for inclusion. All DXA examinations took place at mobile examination centers. Bone mineral content (g) and bone area (cm2) were measured in the proximal femur (subregions: femoral neck, trochanter, and intertrochanter) and lumbar spine (subregions: L1–L4) using a Hologic QDR-4500A fan-beam densitometer (Hologic, Inc., Bedford, MA). Bone mineral density was calculated by dividing the sum of subregion bone mineral content by the sum of subregion bone area. In this manner, DXA-derived BMD is an approximation of mass per volume based on a two-dimensional rendering, hence g/cm2 versus g/cm3. Measurements were performed by certified radiographic technicians who were periodically monitored in the field. Quality control calibration scans were performed daily. Images were reviewed using Hologic Discovery v12.4 (Hologic, Inc). BMD data were reported to the thousandths of a g/cm2.

Dependent variable 2: Low bone mineral density

Binary variables indicating the presence of low BMD were created, one each for the proximal femur and lumbar spine. For each site, the weighted mean BMD and standard deviation were calculated for women aged 20–29 years (n=685 for lumbar spine; n=765 for proximal femur). These values were used as standards for creating a site-specific T-score to use with both sexes. The World Health Organization recommends women aged 20–29 years as the reference (17, 29). Participants with lumbar or proximal femur BMDs >1 SD below the reference mean were defined as having low BMD for the site under study.

Independent variable: Physical activity

In NHANES 2007–2010, self-reported physical activity was assessed using an instrument based on the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (8). Respondents were asked to report the frequency and duration of vigorous- and moderate-intensity, leisure-time physical activities for a typical week. Participants were instructed to classify activity as vigorous intensity or moderate intensity based on perceived heart rate and breathing increases. The specific activities performed were not reported. The reported frequency, duration, and NHANES-recommended metabolic-equivalent (MET) values (8.0 for vigorous- and 4.0 for moderate-intensity) were multiplied to estimate summary physical activity volume in MET-hours per week (MET·H·Wk−1). A value of at least 7.5 MET·H·Wk−1 was used to denote meeting minimum physical activity guidelines (3.0 METs X 2.5 hours per week). The present analyses focus on leisure time activity as this domain most closely corresponds with previous activities that have shown reduced BMD with high volume participation (2, 6, 14, 20, 26) and is arguably the domain with the greatest degree of volitional control and thus amenable to change.

Categories of leisure-time physical activity participation were created including no reported activity (0 MET·H·Wk−1), insufficient physical activity (>0 – 7.49 MET·H·Wk−1), meeting physical activity guidelines (7.50–14.99 MET·H·Wk−1), and subsequent categories for exceeding guidelines multiple times over. For categories exceeding guidelines, a multiple of the minimum guideline-specified volume was the lower category bound (e.g. 15–22.49 MET·H·Wk−1 for doubling but not tripling guidelines, 22.50–29.99 MET·H·Wk−1 for tripling but not quadrupling, etc.). In cases where a category had few participants, adjacent categories were combined to allow stratified analyses. A superscript dash (−) was used to denote “up to but not including” (e.g., 2–4− x guidelines includes those doubling, tripling, but not quadrupling guidelines with 15.00–29.99 MET·H·Wk−1). As a reference, Table 1 gives the hours per week required to meet and exceed physical activity guidelines for three common activities.

Table 1.

Approximate hours per week required to meet and exceed the 2008 US Physical Activity Guidelines for three common activities

| Hours per week required at various intensities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Multiples of meeting guidelines | MET·H·Wk−1 (minimum) | Walking – 2.5 MPH (3.0 METs) | Jogging – general (7.0 METs) | Running - 6 MPH (9.8 METs) |

| 1x | 7.5 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 0.8 |

| 2x | 15.0 | 5 | 2.1 | 1.5 |

| 3x | 22.5 | 7.5 | 3.2 | 2.3 |

| 4x | 30.0 | 10 | 4.3 | 3.1 |

| 5x | 37.5 | 12.5 | 5.4 | 3.8 |

| 6x | 45.0 | 15 | 6.4 | 4.6 |

| 7x | 52.5 | 17.5 | 7.5 | 5.4 |

| 8x+ | 60.0 | 20 | 8.6 | 6.1 |

MET: Metabolic Equivalent

MET·H·Wk−1: MET-hours per week

MET values are sourced from the compendium of physical activities18

Covariates

Age, gender, and race/ethnicity was obtained from NHANES demographic files. Reported use of calcium and vitamin-D supplements was coded as binary variables. Use of osteogenic medications (bone resorption inhibitors, calcitonin, and teriparatide), prescription NSAIDS, oral contraceptives, and male/female sex hormone therapies were also coded as binary variables. When possible, the medication container was examined by NHANES staff. Cigarette smoking status was classified as never, former, or current use. Alcohol use was classified as never, former, current-low (≤ 14 drinks per week), or current-high (>14 drinks per week). Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) was already calculated in NHANES, and was derived from measured height (stadiometer) and measured weight (digital scale).

Statistical Methods

Descriptive analyses included summary statistics for all variables. Means with standard deviations were generated for continuous variables; percentages were generated for categorical variables. Associations between covariates and physical activity category (3 level) were tested using Pearson’s χ2 tests for categorical variables and linear regression for continuous variables. Differences between those with and those without complete data were tested using Pearson’s χ2 tests or unpaired t-tests where appropriate.

Linear regression was used to generate crude, age-adjusted, and multivariable-adjusted mean BMDs across physical activity categories for each gender. Age-related declines in both physical activity (24) and BMD (3) are well-established; hence age likely confounds the association between activity and BMD. Because of this, crude results were omitted in favor of age- and multivariable-adjusted results. Differences in mean BMD between activity categories were tested using Wald tests with a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Multivariable models were constructed separately for each sex and anatomical site. Covariates associated with physical activity and BMD in stratified analyses were initially included as potential confounders, then each was removed and the resultant beta (β) coefficients for the physical activity factor variables were inspected. If there were no changes greater than 10%, the variable remained excluded. This was repeated until each covariate was either determined to be statistically significant in the model or was retained as a confounder. Potential interactions between physical activity and other covariates were tested with cumulative Wald tests. After stratified analyses revealed a potentially non-linear relation between physical activity and BMD, several analytic strategies were tested to determine which explained the most variance in BMD. Physical activity in MET·H·Wk−1 was used as a continuous variable, and squared and quadratic terms were entered. Additionally, spline regression with knots at activity category boundaries was performed.

Logistic regression was used to determine the crude, age-adjusted and adjusted odds of low BMD relative to the “no activity” group. Multivariable model building followed Hosmer and Lemeshow (16) and was similar to that described previously. As with linear regression, crude results were omitted.

All analyses were conducted using STATA v11SE software (College Station, TX, USA) and followed NHANES analytic guidelines (11). Survey-specific commands that included the NHANES-specified mobile examination sampling weights were used to account for the complex survey design. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05.

Results

The combined 2007–2010 NHANES cycles comprised 12,153 adults (6,237 women, 5916 men) 20 years or older. NHANES does not report ages > 80 years, so no upper bound is available. Of these, 9,486 (77.9%) had complete covariate data and a complete DXA scan for at least one of the two anatomical sites (lumbar spine or proximal femur). Those with complete data were more likely to be male (49.8% complete data; 41.0% incomplete data, p<0.001), non-Hispanic White (70.2% complete data; 61.8% incomplete data, p<0.001), have a lower BMI (28.2 kg/m2 complete data; 30.8 kg/m2 incomplete data, p<0.001), and meet activity guidelines (42.1% complete, 32.8% incomplete, p<0.001). There was no difference in age (mean 47.0 years complete data; 46.5 years incomplete data, p=0.310), proportion of current smokers (21.8% complete data; 20.2% incomplete, p=0.13), or proportion of current-high alcohol consumers (5.9% complete data; 4.6% incomplete data, p=0.202). Of all variables, the most commonly missing was lumbar DXA, which was complete in 7,787 (64.1%) participants, while 9,778 (80.5%) had complete proximal femur DXA results.

Descriptive statistics for those with at least one complete DXA site and complete covariate data are presented in Table 2. Nearly half (46.8%) reported no leisure-time physical activity while 42.1% reported sufficient activity to meet physical activity guidelines. Participants that met guidelines were younger than those that reported no or insufficient activity, had lower BMIs, were less likely to be female, and more likely non-Hispanic white. Among covariates, only sex hormone and osteogenic medication use were not associated with reported physical activity. The prevalence of low BMD at both sites was highest among those with no reported activity followed by those meeting guidelines, followed by those with insufficient activity.

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics stratified by reported leisure-time physical activity participation: US adult respondents 20 years or older, NHANES 2007–2010 (n=9468)

| No LTPA (n=5141) | Insufficienta (n=942) | Meeting GLb (n=3385) | Pc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Weighted % | 46.8 | 11.1 | 42.1 | |

| Age (yr) | 50.0 (17.5) | 46.9 (14.7) | 43.7 (14.3) | <0.001 |

| Female (%) | 53.9 | 54.8 | 44.9 | <0.001 |

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | ||||

| NH White | 65.2 | 74.8 | 74.6 | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 16.3 | 9.6 | 11.0 | |

| NH Black | 12.6 | 9.5 | 8.6 | |

| Other/Multi | 5.9 | 6.1 | 5.8 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.0 (6.4) | 28.3 (5.5) | 27.3 (4.7) | <0.001 |

| Sex hormone (%) | 3.6 | 3.3 | 3.7 | 0.826 |

| Women on OC (%) | 4.4 | 8.8 | 12.8 | <0.001 |

| Calcium supplement use (%) | 39.4 | 48.6 | 50.6 | <0.001 |

| Vitamin D supplement use (%) | 31.9 | 41.3 | 43.8 | <0.001 |

| Osteogenic medication use (%) | 2.4 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 0.423 |

| Prescription NSAID use (%) | 5.2 | 4.5 | 3.4 | 0.003 |

| Alcohol consumption (%) | ||||

| Never | 13.2 | 10.0 | 7.7 | <0.001 |

| Former | 20.7 | 12.9 | 11.3 | |

| ≤14 per wk | 59.5 | 71.9 | 75.6 | |

| >14 per wk | 6.5 | 5.2 | 5.4 | |

| Smoking status (%) | ||||

| Never | 48.7 | 55.9 | 58.1 | <0.001 |

| Former | 24.3 | 25.0 | 25.1 | |

| Current | 27.0 | 19.1 | 16.8 | |

| Low lumbar BMD (%)d | 13.3 | 3.0 | 10.4 | <0.001 |

| Low prox femur BMD (%)e | 12.5 | 2.7 | 7.4 | <0.001 |

LTPA: leisure-time physical activity; GL: guidelines; NH: non-Hispanic; BMI: body mass index; OC: oral contraceptives

>0 to <7.5 MET·H·Wk−1

≥ 7.5 MET·H·Wk−1

Pearson χ2 for all variables except age and BMI, which are weighted regression

n=7320 with lumbar DXA

n=9209 with proximal femur DXA

Values are weighted mean (Standard deviation) or proportion indicated by (%). Included are all participants with at least one valid DXA (lumbar spine or proximal femur) scan, complete self-reported leisure-time physical activity, and covariates. Oral contraceptive distribution is for women only.

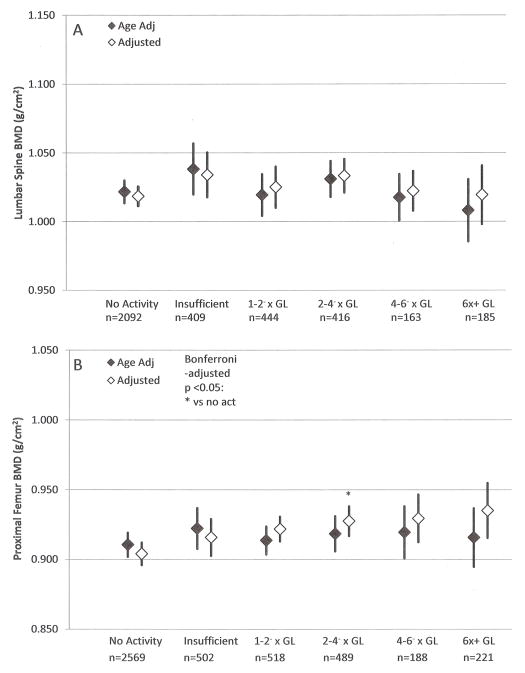

Figure 1 presents age- and multivariable-adjusted mean BMD at the lumbar spine (panel A) and proximal femur (panel B) for women. Multivariable models for both sites included age, race/ethnicity, BMI, osteogenic medication use, alcohol consumption and smoking status. There were no statistically significant differences for the lumbar spine across physical activity categories, regardless of the level of adjustment. In multivariable models at the proximal femur, women who reported activity at 2–4− times the guidelines exhibited significantly higher BMD at the proximal femur (0.928 g/cm2) than those who reported no activity (0.904 g/cm2, p=0.018).

Figure 1.

Age and multivariable adjusted (A) lumbar spine and (B) proximal femur BMD with 95% confidence intervals, women 20+ years, NHANES 2007–2010

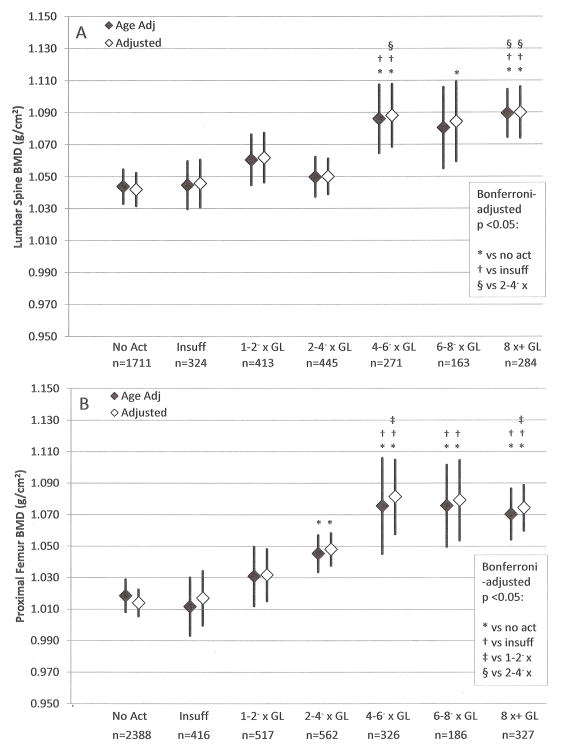

Figure 2 presents age- and multivariable-adjusted mean BMD at the lumbar spine (panel A) and proximal femur (panel B) for men. The multivariable models for both sites included age, race/ethnicity, BMI, osteogenic medication use, alcohol consumption, and smoking status. The lumbar model also included prescription sex hormone use. At the lumbar spine, mean BMD values across the lowest four activity categories were similar. Mean BMD values among the upper three categories were similar and higher than those of the lower four categories. For example, after multivariable adjustment, men who reported activity volumes of 4–6− times (1.088 g/cm2, p=0.001), 6–8− times (1.084 g/cm2, p=0.035), and ≥8 times guidelines (1.090 g/cm2, p<0.001) had significantly higher lumbar BMD than those who reported no activity (1.042 g/cm2). Men who reported activity at 4–6− and ≥8 times guidelines also exhibited significantly higher adjusted lumbar BMD than the groups who reported insufficient activity (1.088 and 1.090 versus 1.046 g/cm2, p=0.017 and p=0.001, respectively), or the group who reported volumes of 2–4− times guidelines (1.088 and 1.090 versus 1.050 g/cm2, p=0.033 and p=0.022, respectively). At the proximal femur, the results exhibited an s-shaped relation: those who reported no or insufficient activity had similar values, then progressively higher BMD values were observed with higher activity up to 4–6− times guidelines; beyond this point, the values were similar. We noted that, regardless of the level of adjustment, all categories that corresponded to 2–4− times guidelines, or greater, exhibited significantly higher BMD at the proximal femur than the no activity category (e.g., adjusted BMDs of 1.048, 1.081, 1.079, and 1.074 g/cm2 for the 2–4−, 4–6−, 6–8−, and ≥8 times guidelines, respectively, versus 1.014 g/cm2 for the no activity group, all p<0.01). Comparisons among the upper three categories revealed no significant differences.

Figure 2.

Age and multivariable adjusted (A) lumbar spine and (B) proximal femur BMD with 95% confidence intervals, men 20+ years, NHANES 2007–2010

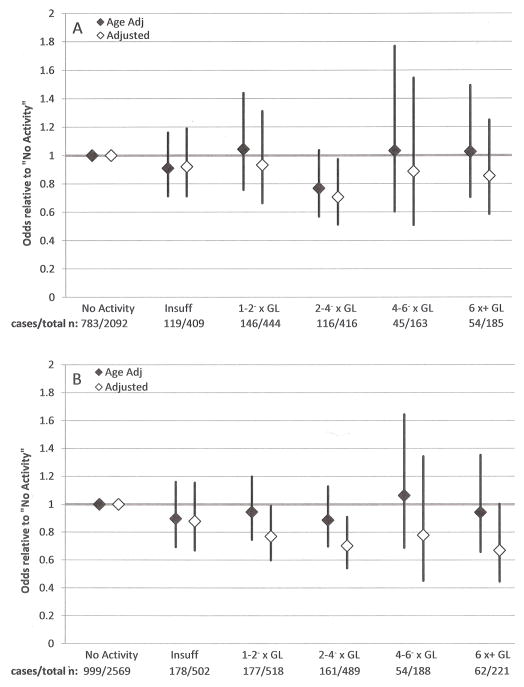

The relative odds of low BMD for women are presented in Figures 3a and 3b. Those with no physical activity serve as the referent group. Multivariable models for both sites included age, race/ethnicity, BMI, osteogenic medication use, alcohol consumption, and smoking status. The model for the proximal femur also included prescription sex hormone use. Age adjusted models at both sites revealed no significant differences in relative odds across activity categories. At the lumbar spine, multivariable analyses revealed that women who reported activity at 2–4− times physical activity guidelines were significantly less likely to have low BMD than women who reported no activity (adjusted odds ratio [95% confidence interval]: 0.71 [0.51–0.97]). At the proximal femur, multivariable models revealed significantly lower odds of low BMD among women who reported activity at 1–2− times guidelines and 2–4− times guidelines versus the no-activity group (adjusted odds ratios: 0.77 [0.60–0.99] and 0.70 [0.54–0.91], respectively).

Figure 3.

Age and multivariable adjusted relative odds of low (A) lumbar spine and (B) proximal femur BMD with 95% confidence intervals, women 20+ years, NHANES 2007–2010

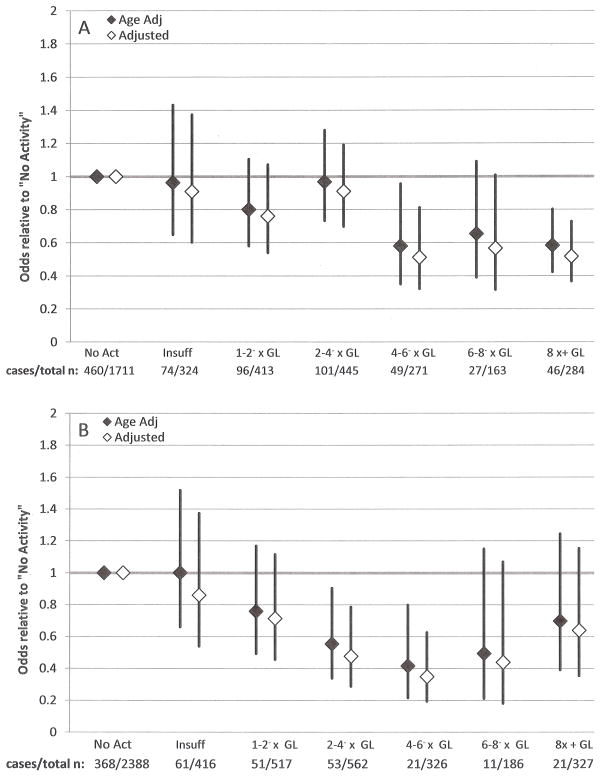

The relative odds of low BMD for men are presented in Figures 4a and 4b. Men who reported no physical activity are the referent group. Multivariable models for both sites included race/ethnicity, BMI, alcohol consumption, and smoking status. The lumbar model included osteogenic medication use and the proximal femur model included age. Age was not significantly associated with low lumbar BMD among men. The relative odds of low lumbar BMD versus the no activity group were sharply lower for those at 4–6− times guidelines versus those at 2–4− times (adjusted odds ratios: 0.51 [0.32–0.81] versus 0.91 [0.70–1.19], respectively). For categories ≥4–6− times the physical activity guidelines, point estimates for the relative odds of low lumbar BMD were of similar magnitude (0.51, 0.57, and 0.52 for 4–6−, 6–8−, and ≥8 times physical activity guidelines, respectively). Regardless of adjustment, men who reported activity at 4–6− times or 8 times guidelines had lower odds of low lumbar spine BMD than the no activity group (adjusted odds ratios: 0.51 [0.32–0.81] and 0.52 [0.37–0.73], respectively). For the proximal femur age- and multivariable-adjusted models revealed that only men who reported activity of 2–4− times or 4–6− times physical activity guidelines were significantly less likely to have low proximal femur BMD compared with men who reported no physical activity (adjusted odds ratios: 0.48 [0.29–0.79] and 0.35 [0.19–0.63], respectively).

Figure 4.

Age and multivariable adjusted relative odds of low (A) lumbar spine and (B) proximal femur BMD with 95% confidence intervals, men 20+ years, NHANES 2007–2010

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to quantify BMD across the full range of physical activity volume in an adult population-based sample and to assess the relative odds of low BMD by volume of physical activity. Using adjusted linear regression models, major findings among women included lack of an association between BMD and activity volume at the lumbar spine, and higher BMD at the proximal femur only among women who reported activity at 2–4− times guidelines versus no activity. For men, the key finding was that BMD at both the lumbar spine and proximal femur neared its peak among those who reported activity volume of 4–6− times guidelines, and was not progressively higher with greater reported volume. For both sexes and anatomical sites, results of logistic regression were largely compatible with results from linear regression in that categories exhibiting high BMD tended to have reduced risk for low BMD versus the no-activity categories.

These results do not support the hypothesis that BMD at the lumbar spine or proximal femur may be lower with high volumes of aerobic physical activity in the general population. This is in contrast to longitudinal studies reporting bone mineral losses among endurance-type athletes in training (2, 20). A possible explanation for this discrepancy is that the range of activity volume reported by NHANES participants is too low to compare with studies of athletes in training. For example, Klesges et al. reported a maximum of two 2-hour practices per day in a study of BMD among collegiate basketball players (20). According to the compendium of physical activities (1), competitive basketball practice (with drills) requires 9.3 METs. With five practices per week, the estimated volume would be 186 MET·H·Wk−1 or roughly 25 times the minimum recommended in the physical activity guidelines. By contrast, the highest activity category in the present analyses included men who exceeded guidelines by 8 times or more. Physical activity volume comparable with that reported by Klesges et al. (20) was too infrequent in the current study to be effectively evaluated. Alternatively, activity volume in NHANES may have been attained through extremely high-impact activities that place large osteogenic stimuli on the proximal femur and lumbar spine that could overwhelm any osteolytic mechanisms at play in studies of athletes. It seems unlikely, however, that NHANES respondents experienced greater impact forces than the collegiate basketball players in Klesges et al. (20). Unfortunately, estimation of impact forces is not possible with the physical activity data available in NHANES 2007–2010.

The present results suggest a non-linear relation between reported physical activity volume and BMD, particularly at the proximal femur among men. Based on Figure 2 panel B, BMD is similar between those who reported no or insufficient activity then higher with greater activity volume, up to those reporting activity at 4–6− times guidelines, beyond which no differences were seen. Several additional regression strategies were used to account for non-linearity, including entering activity volume in MET·H·Wk−1 as a continuous independent variable with a squared or quadratic term and using spline regression with knots at activity category boundaries. No strategy explained additional variance in BMD beyond that explained in the presented analyses. Further, plots of residuals did not indicate improvement in fit for the alternative techniques. Considering these points, physical activity was presented as a factor variable in these analyses to aid interpretability.

The reason for nonlinearity in the association between activity volume and BMD cannot be derived from these cross-sectional data. Experimental evidence suggests that the magnitude and rate (intensity) at which bone is loaded is a key factor in the osteogenic response (4). To effectively stimulate bone accrual, these forces must exceed the forces to which a person has become habituated. Considering this, it is possible that the high activity categories all experienced similar bone loading intensity despite progressively higher activity volume across categories, which would occur if higher activity volume was attained primarily through longer duration participation in similar activities rather than increased intensity. Notably, the vigorous-intensity activity reported in NHANES refers not to impact intensity but aerobic intensity (i.e. % of maximal VO2), and is at best a crude proxy for impact forces. In post-hoc analyses, the association between activity volume and BMD was not significantly different in those reporting any vigorous intensity aerobic activity versus those reporting no vigorous intensity aerobic activity. An alternative explanation is that high-volume physical activity may be accompanied by another physiologic process that overwhelms the osteogenic stimulus of physical activity, such as suppression of the gonadal-pituitary axis during energy imbalance, elevated stress hormones and inflammatory cytokines, or excessive dermal calcium loss. Assessment of different types of activities and the intensity at which activities are performed by US adults could inform this area of study.

The lack of association between lumbar BMD and physical activity in women appears to conflict with the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report (24) and a recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in premenopausal women (19). Both of these reviews suggest that endurance and resistance exercise interventions can increase lumbar BMD by 1–2% per year in pre- and postmenopausal women (24). By extension, one would expect higher lumbar BMD with higher reported physical activity volume in the present analyses, but we did not see this. The discrepancy may be due to the binary categorization of physical activity in most meta-analyses (presence or absence of exercise intervention). When a comparable post-hoc analysis was performed in this study, women who reported any activity had 1% higher adjusted mean lumbar BMD than those who reported no activity (p=0.019). This result is similar to the summary effect size reported by the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee and would argue for more detailed assessment and categorization of physical activity to allow dose-response analyses.

The association between physical activity and BMD was notably different between men and women in these analyses. Among women, the range in adjusted mean BMD at the lumbar spine was 0.016 g/cm2 and peaked in those with insufficient physical activity. Among men, the range was threefold greater (0.048 g/cm2) and peaked in those reporting ≥ 8 times guidelines. At the proximal femur, there was less discrepancy, although the range of values among men (0.067 g/cm2) was twice that of women (0.031 g/cm2), and both sexes exhibited peak adjusted mean BMD among those with activity near 6 times guidelines. The sex differences are not easily explained by these analyses. One possibility is that women attain physical activity by modes that place less osteogenic strain on the lumbar spine and proximal femur. This hypothesis is supported by accelerometer-based physical activity estimates among US adults from NHANES 2003–2004 that found women of all ages accumulated fewer minutes of vigorous intensity activity per day than did men (27). These accelerometry statistics are particularly notable as accelerometers measure vertical acceleration at the hip and are therefore particularly appropriate for capturing weight-bearing ambulatory aerobic activity that produces osteogenic ground reaction forces. Alternatively, low estrogen and estrogen receptor-α levels in older women may suppress bone’s response to mechanical loading, as noted previously (21, 22). A large study including DXA, accelerometry, and hormonal status could clarify this area.

This research had several strengths. First, the size of the NHANES dataset from 2007–2010 allowed participants to be categorized into multiple strata of physical activity participation, allowing the shape of the association between physical activity and BMD to be more accurately depicted than is possible with broader activity categorization. Second, the sample size allowed complete separation of analyses for men and women. The age-related decline in BMD is more pronounced in women, and as depicted here, the physical activity–BMD association was also of different magnitudes in men and women. Finally, these analyses represented a broad spectrum of the US population. Previous studies of BMD in the highly active have primarily involved athletes. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the largest single analysis of the relationship between physical activity and skeletal health in the general public.

Several limitations should be noted. First, the DXA scan was limited to a subset of participants who met the inclusion criteria for the scan procedure. While diverse, the sample does not precisely represent the US population, as intended in the NHANES sampling method. Despite this, a depiction of the relation between population-typical physical activity volume and BMD was attainable. Second, physical activity assessment in NHANES 2007–2010 was limited to self-report using the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ), which solicited activity by aerobic intensity versus specific activity types, and did not assess resistance-training activities. Because activity-associated BMD changes depend upon mechanical loading of bones, a motion-capturing device, such as accelerometry, may better depict the activity-BMD association by serving as a more accurate proxy of mechanical strain than general reported activity. Also, the GPAQ was designed as a physical activity surveillance tool, and its utility as an individual-level measure of physical activity has not been established (7). Finally, serum sex hormone levels are determinants of bone health (3, 15) and may be reduced with high volume physical activity (13). Sex hormone status was not available in the laboratory component of NHANES, though prescription sex hormone use was considered in multivariable models.

In conclusion, these data suggested that the full range of physical activity volume in a population-based sample of US adults is not associated with low BMD at the lumbar spine or proximal femur. Aerobic physical activity at volumes up to four-times guidelines may be optimal for bone health, though this finding is preliminary. The association between activity volume and skeletal health is complex and not easily explained by cross-sectional data. Additional research is needed to better understand the association between activity and skeletal health across a continuum of physical activity volume. These data may help inform future physical activity guidelines regarding skeletal health.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Whitfield (partial support, predoctoral fellowship) - National Cancer Institute/NIH Grant #2 R25 CA57712

WMK served as a paid member of the International Institute for Nutrition and Bone Health and received funding for similar work from the National Institutes of Health and the US Department of Defense.

GPW was supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the University of Texas School of Public Health, Cancer Education and Career Development Program – National Cancer Institute/NIH Grant #2 R25 CA57712, and thanks his colleagues in the program for their feedback.

Footnotes

Authors’ roles: Study design: GPW. Study conduct: GPW. Data analysis: GPW. Data interpretation: GPW, WMK, KPG, MHR, HWKIII. Drafting manuscript: GPW. Revising manuscript content: GPW, WMK, KPG, MHR, HWKIII. Approving final version: All. GPW takes responsibility for the integrity of the data analysis. The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by the American College of Sports Medicine.

Disclosures: WMK served as a paid member of the International Institute for Nutrition and Bone Health. WMK received funding for similar work from the National Institutes of Health and the US Department of Defense. No other authors reported any financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, Meckes N, Bassett DR, Jr, Tudor-Locke C, et al. 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(8):1575–81. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barry DW, Kohrt WM. BMD decreases over the course of a year in competitive male cyclists. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23(4):484–91. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.071203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barry DW, Kohrt WM. Exercise and the preservation of bone health. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2008;28(3):153–62. doi: 10.1097/01.HCR.0000320065.50976.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer JJ, Snow CM. What is the prescription for healthy bones? J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2003;3(4):352–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beaupre LA, Jones CA, Johnston DW, Wilson DM, Majumdar SR. Recovery of function following a hip fracture in geriatric ambulatory persons living in nursing homes: prospective cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(7):1268–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bilanin JE, Blanchard MS, Russek-Cohen E. Lower vertebral bone density in male long distance runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1989;21(1):66–70. doi: 10.1249/00005768-198902000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bull FC, Maslin TS, Armstrong T. Global physical activity questionnaire (GPAQ): nine country reliability and validity study. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6(6):790–804. doi: 10.1123/jpah.6.6.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Data Documentation, Codebook, and Frequencies - Physical Activity (PAQ_E) 2007–2008 [cited 2012 July 17]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes2007-2008/PAQ_E.htm.

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES 2007–2008 Examination Files. [cited 2012 July 17]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes2007-2008/exam07_08.htm.

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES 2009–2010 Examination Files. [cited 2012 December 28]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes2009-2010/exam09_10.htm.

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES - Analytic Guidelines. [cited 2012 July 17]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes2003-2004/analytical_guidelines.htm.

- 12.Gunter KB, Almstedt HC, Janz KF. Physical activity in childhood may be the key to optimizing lifespan skeletal health. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2012;40(1):13–21. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e318236e5ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hackney AC, Szczepanowska E, Viru AM. Basal testicular testosterone production in endurance-trained men is suppressed. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2003;89(2):198–201. doi: 10.1007/s00421-003-0794-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hetland ML, Haarbo J, Christiansen C. Low bone mass and high bone turnover in male long distance runners. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77(3):770–5. doi: 10.1210/jcem.77.3.8370698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horstman AM, Dillon EL, Urban RJ, Sheffield-Moore M. The role of androgens and estrogens on healthy aging and longevity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(11):1140–52. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2. New York: Wiley; 2000. pp. 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanis JA, Bianchi G, Bilezikian JP, Kaufman JM, Khosla S, Orwoll E, et al. Towards a diagnostic and therapeutic consensus in male osteoporosis. Osteoporos Intl. 2011;22(11):2789–98. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1632-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karlsson MK, Johnell O, Obrant KJ. Bone mineral density in weight lifters. Calcific Tissue Int. 1993;52(3):212–215. doi: 10.1007/BF00298721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelley GA, Kelley KS, Kohrt WM. Exercise and bone mineral density in premenopausal women: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Endocrinol. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/741639. Available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3563173/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Klesges RC, Ward KD, Shelton ML, Applegate WB, Cantler ED, Palmieri GM, et al. Changes in bone mineral content in male athletes. Mechanisms of action and intervention effects. JAMA. 1996;276(3):226–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lanyon LE. Using functional loading to influence bone mass and architecture: objectives, mechanisms, and relationship with estrogen of the mechanically adaptive process in bone. Bone. 1996;18(1S):37S–43S. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00378-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee KCL, Lanyon LE. Mechanical loading influences bone mass through estrogen receptor α. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2004;32(2):64–68. doi: 10.1097/00003677-200404000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Looker AC, Borrud LG, Dawson-Hughes B, Shepherd JA, Wright NC. Osteoporosis or low bone mass at the femur neck or lumbar spine in older adults: United States, 2005–2008. NCHS data brief. 2012;(93):1–8. Epub 2012/05/24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee; Department of Health and Human Services, editor. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report, 2008. Washington, D.C: 2008. pp. G5–11–G5–14. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sabo D, Bernd L, Pfeil J, Reiter A. Bone quality in the lumbar spine in high-performance athletes. Eur Spine J. 1996;5(4):258–263. doi: 10.1007/BF00301329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart AD, Hannan J. Total and regional bone density in male runners, cyclists, and controls. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(8):1373–7. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200008000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Masse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(1):181–8. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815a51b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans 2008. 2008 [cited 2012 July 5]. Available from: www.health.gov/paguidelines/pdf/paguide.pdf.

- 29.World Health Organization. WHO scientific group on the assessment of osteoporosis at primary health care level. Geneva: 2004. p. 8. [Google Scholar]