Abstract

While overweight and obesity are associated with poor health outcomes in the elderly, the biological bases of obesity-related behaviors during aging are poorly understood. Common variants in the FTO gene are associated with adiposity in children and younger adults as well as with adverse mental health in older individuals. However, it is unclear whether FTO influences longitudinal trajectories of adiposity and other intermediate phenotypes relevant to mental health during aging. We examined whether a commonly carried obesity risk variant in the FTO gene (rs1421085 single nucleotide polymorphism) influences adiposity and is associated with changes in brain function in participants within the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA), one of the longest-running longitudinal aging studies in the United States. Our results show that obesity-related risk allele carriers of FTO gene show dose-dependent increments in body mass index during aging. Moreover, the obesity-related risk allele is associated with reduced medial prefrontal cortical function during aging. Consistent with reduced brain function in regions intrinsic to impulse control and taste responsiveness, risk allele carriers of FTO exhibit dose-dependent increments in both impulsivity and intake of fatty foods. We propose that a common neural mechanism may underlie obesity-associated impulsivity and increased consumption of high calorie foods during aging.

Keywords: FTO, Impulsivity, Brain function, BMI, Diet, Excitement-seeking, rCBF, PET

Introduction

The biological bases of obesity-related behaviors are poorly understood. Popular culture and the media perpetuate a ‘headless, hungry and unhealthy’ stereotype of the overweight individual as weak-willed, susceptible to the temptation of high calorie foods and prone to ill health1. However, it is unclear whether a common biological mechanism underlies predisposition to obesity as well as impulsive behavior and a preference for calorie-dense foods. This question is especially relevant in the context of aging as several adverse health outcomes are associated with obesity in the elderly 2–4. We report on the associations between the common obesity risk variant (rs1421085 single nucleotide polymorphism) in the fat mass- and obesity-associated gene, FTO, and longitudinal changes in adiposity, brain function, impulsivity and macronutrient intake in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA)5.

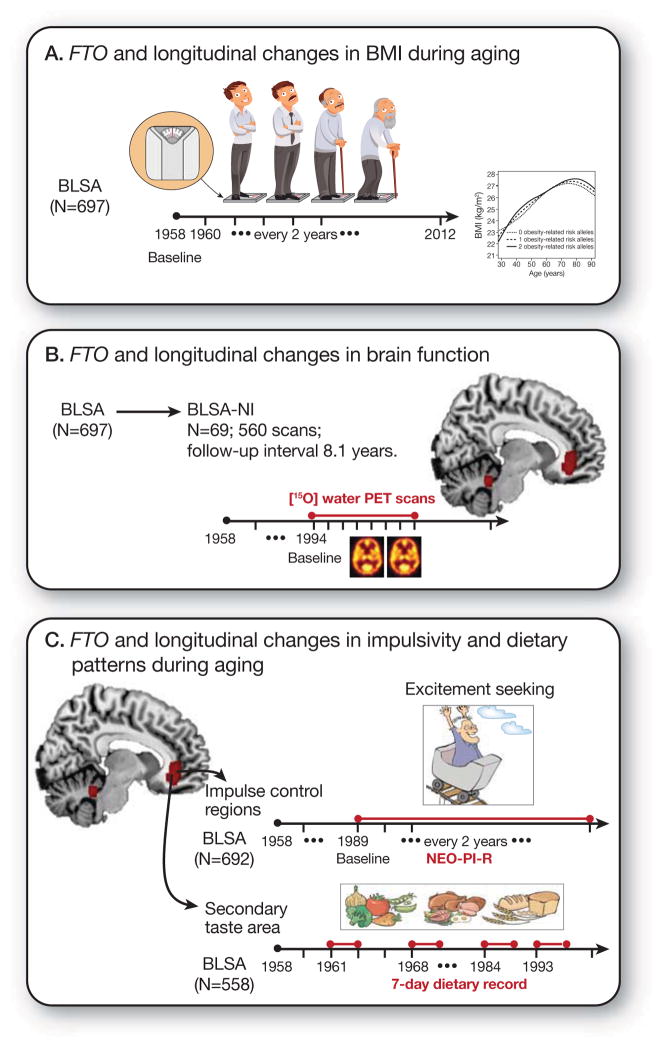

Figure 1 summarizes the study design. First, we examined whether FTO genotype influenced trajectories of body mass index (BMI) during aging. Second, using serial 15O-water positron emission tomography (PET), we compared longitudinal changes in regional resting-state cerebral blood flow (rCBF), an established marker of neuronal activity6, between obesity-related risk allele carriers (FTO+) and non-carriers (FTO−). Then, based on differences in the regional pattern of longitudinal changes in rCBF between FTO risk and non-risk groups, we asked whether FTO genotype influences longitudinal changes in impulsivity and dietary patterns during aging.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the study design and work flow A) Our first aim was to test whether FTO genotype (rs1421085 single nucleotide polymorphism; obesity-risk allele-C) influenced trajectories of adiposity during aging in the BLSA B) The second aim was to examine the association between FTO genotype and longitudinal changes in brain function, measured by serial resting state cerebral blood flow (rCBF) through 15O-water PET imaging in the neuroimaging substudy of the BLSA (BLSA-NI) C) Finally, based on our longitudinal rCBF results implicating brain regions involved in impulse control and taste responsiveness to food, we tested whether FTO genotype influenced longitudinal changes in impulsivity and macronutrient intake patterns during aging.

Abbreviations: BLSA, Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging; FTO, fat mass and obesity associated gene

Materials and Methods

Participants

The BLSA is a prospective cohort study of community dwelling volunteer participants in Baltimore, beginning in 1958, and is one of the largest and longest-running longitudinal studies of aging in the United States 5, 7. The community dwelling unpaid volunteer participants are predominantly white, of upper-middle socioeconomic status, and with an above average educational level. In general, at the time of entry into the study, participants had no physical and cognitive impairment (i.e. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score ≤ 24) and no chronic medical condition with the exception of well-controlled hypertension. Detailed examinations, including neuropsychological assessment and neurological, laboratory, and radiological evaluations, were conducted every 2 years. Written informed consent was obtained from participants at each visit, and the study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board and the National Institute on Aging.

Cognitive status were ascertained at consensus diagnosis conferences according to established procedures described previously 8, using information from neuropsychological tests and clinical data. Diagnoses of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) were based on DSM-III-R 9 and the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria 10 respectively. Only participants who remained free of dementia or mild cognitive impairment through the follow-up interval were included in the current analyses. The final study sample consisted of 697 cognitively normal participants (total 7,300 visits) with a mean follow-up interval of 23.1 ± 12 years (Table 1). All participants in this study sample are Caucasians. Among them, personality measures were available in 692 participants with a mean follow-up period of 10.0±5.8 years while longitudinal dietary records were available in 558 participants (1694 visits) with a mean follow-up interval of 15.9 ± 10.3 years (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants from BLSA cohort*

| Whole sample (n= 697) | TT (n = 226) | TC (n = 336) | CC (n = 135) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at baseline, years | 45.8±16.8 (17–96) | 45.6±15.7 | 45.2±17.3 | 47.3±17.5 | 0.484 |

| Female | 325(46.6) | 109 (48.2) | 155 (46.1) | 61 (45.2) | 0.827 |

| Education, years | 16.7±2.2 | 16.7±2.1 | 16.8±2.3 | 16.4±2.3 | 0.207 |

| Mean follow-up years | 23.1±12.0 | 23.8±11.8 | 22.7±12.2 | 23.2±11.8 | 0.512 |

| Mean follow-up visits | 10.5±6.0 | 10.8±6.1 | 10.3±6.2 | 10.4±5.7 | 0.596 |

| Physical activity at baseline | 0.134 | ||||

| Sedentary | 39 (7.6) | 16 (9.3) | 19 (8.2) | 4 (3.8) | |

| Light | 191 (37.4) | 74 (42.8) | 80 (34.3) | 37 (35.6) | |

| Moderate-high | 280 (54.9) | 83 (48.0) | 134 (57.5) | 63 (60.6) | |

| Smoking | 0.652 | ||||

| Never | 323 (46.3) | 106 (46.9) | 159 (47.3) | 58 (43.0) | |

| Former | 296 (42.5) | 98 (43.4) | 135 (40.2) | 63 (46.7) | |

| Current | 78 (11.2) | 22 (9.7) | 42 (12.5) | 14 (10.4) | |

| Baseline BMI | 24.5±3.6 | 24.5±3.8 | 24.4±3.5 | 24.6±3.4 | 0.817 |

Continuous characteristics are expressed as mean±SD. Categorial characteristics are expressed as no. (%)

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation

The Neuroimaging substudy 11 of the BLSA (BLSA-NI), beginning in 1994, includes a subset of BLSA participants who agreed to annual neuroimaging assessment and were free of central nervous system disease (dementia, stroke, bipolar illness, epilepsy), severe cardiac disease (myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease requiring angioplasty or coronary artery bypass surgery), several pulmonary disease, or metastatic cancer. The study sample consisted of 69 cognitively normal participants (43 men and 26 women; mean age 69 ± 7.3 years) who completed at least three 15O-water PET scans between 1994 and 2003 with mean follow-up 8.1 ± 1.1 years and total 560 scans (Supplementary Table 2).

FTO genotyping

Several SNPs in the FTO gene have been reported to be associated with obesity traits 12–14. These SNPs are in strong linkage disequilibrium (LD). Of the three SNPs in FTO that were first reported to be associated with obesity (rs1421085, rs17817449, rs9939609) and subsequently replicated in several studies, we focused on rs1421085, an obesity-related FTO SNP that has previously been associated with common mental disorders as well as with brain atrophy in non-demented older individuals 15, 16. In the BLSA, we confirmed that the rs1421085 SNP was in high LD with both rs17817449 LD=0.927) as well as with rs9939609 (LD=0.931). Genome-wide genotyping was performed using the Illumina Infinium HumanHap550 genotyping chip (Illumina, San Diego, California), assaying >555,000 unique SNPs per sample. Standard quality control of genotyping data was conducted including verification of data completeness, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, and Mendelian incompatibilities as described previously 17, 18. We entered the number of obesity-related risk C alleles of rs1421085 (0,1 or 2) assuming additive models. In 15O-water PET analyses where dominant models were used because of small sample size, participants with one or two obesity-related risk C alleles of rs1421085 were classified as FTO+ whereas those with T/T genotype were classified as FTO−.

Body mass index (BMI) measurement

Height and weight were measured with calibrated scales by trained technicians at each visit.

Covariates used in the FTO genotype and BMI analyses

Smoking was ascertained by self-report, and participants were categorized as ‘non-smokers,’ ‘former’ or ‘current’ smokers. In the BLSA sample, self-reported physical activity was determined with a questionnaire covering specific activities at home, work, and recreation, and metabolic equivalent of task (MET)/week was calculated accordingly.19 Based on this measure, participants were categorized as being sedentary (0–50 MET-minute/week), performing light physical activity (50–250 MET-minute/week), or moderate-high physical activity (≥ 250 MET-minute/week). The first available physical activity category during follow-up was used in the analysis.

15O-water PET data analysis

The data used in the current analyses were obtained from a resting-state scan in each session. During the rest scan, participants were instructed to keep their eyes open and focused on a computer screen covered by a black cloth. PET derived regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) measures were obtained using [15O] water on a GE 4096+ scanner. For each scan, 75 mCi of [15O] were injected as a bolus. Images of 15 axial slices of 6.5 mm thickness were acquired for 60 s from the time total radioactivity counts in the brain reached threshold level. Attenuation correction was performed using a transmission scan acquired before the emission scans.

Image preprocessing and analyses were done using Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM5; Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK). The PET scans were realigned and spatially normalized into the 2×2×2 mm MNI (Montreal Neuroscience Institute) template space, and smoothed using a full width at half maximum of 12×12×12 mm in the x, y, and z plans. To control for variability in global flow, voxel rCBF values were ratio adjusted to the mean global flow of 50 ml/100mg/min for each image.

Due to the relatively small number of homozygous risk allele carriers, only dominant (FTO+ versus FTO−) models were used in the 15O-water PET analysis. Voxel-wise differences in longitudinal changes in resting rCBF between groups (FTO+ vs. FTO−) were examined by group × time interaction, adjusting for age at first scan and sex. Significant effects for each contrast were based on both a statistical magnitude (P < 0.005) and a spatial extent (cluster size > 50 voxels (400 mm3)) as recommended by the PET Working Group of the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging Neuroimaging Initiative (http://www.nia.nih.gov/about/events/2011/positron-emission-tomography-working-group).

Covariates used in the FTO genotype and rCBF analyses

Mean BMI during the follow-up period of scans was calculated. We calculated overall cardiovascular risk by the number of specific cardiovascular co-morbidities and risk factors ascertained by self-reported medical history, physical examination and laboratory data. These included hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, smoking status, and history of angina, myocardial infarction and transient ischemic attack. APOE ε4 carrier status was used as a covariate in secondary analyses. Finally, volumes for each significant cluster were obtained and covaried in the model to account for the effect of potential volume differences between groups.

Personality assessment

Personality traits were assessed with the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R)20, which has been collected in the BLSA since 1989. The NEO-PI-R is a 240-item questionnaire that assesses 30 facets, including six for each of its five major dimensions of personality. In the current analyses, we focused primarily on the impulsivity-related facets of the NEO-PI-R: Impulsiveness (N5), Excitement-Seeking (E5), Self-Discipline (C5), and Deliberation (C6). Raw scores were standardized to T scores (M = 50, SD = 10) using combined-sex norms reported in the NEO PI-R professional manual by Costa and McCrae 20. The psychometric properties of NEO-PI-R in the BLSA have been described in detail elsewhere 17.

Dietary Records

Dietary intakes were assessed by 7-day dietary records collected during 4 time periods: 1961–1965, 1968–1975, 1984–1991, and 1993–2005. The details regarding dietary data collection methods have been published previously 19, 21, 22. Briefly, BLSA participants were trained in the procedure for completing 7-day food records by dietitians. Participants completed the food records at home and sent them to the study center for processing. Prior to 1993, in order to assist participants in assessing portion sizes, they were provided food models and a booklet of food pictures. Subsequently, subjects were given a portable scale for weighing food portions. Any questions about ascertained diet records were resolved by contacting participants by telephone.

Macronutrient consumption was characterized as the average grams of fat, carbohydrate and protein intake across the multiple days of diet records. These values were then converted into calories by multiplying the total grams of each macronutrient by the corresponding number of calories per gram (1g of fat = 9 calories, 1g of protein = 4 calories, and 1g of carbohydrate = 4 calories). The percentages of energy derived from fat, carbohydrate, and protein intakes were calculated by dividing the calories from that macronutrient by the sum of calories from all 3 macronutrients (i.e. fat, carbohydrate and protein).

Statistical analysis

Exploratory inspection of the relationship between FTO genotype and BMI trajectories showed a non-linear relationship. In order to account for repeated measures of BMI and the non-linear relationship between FTO genotype and BMI changes, the generalized least squares models using gls() function from nlme package in R 23 were implemented. Chronological age was used as the time metric and natural cubic spline (ns() function in splines package) was incorporated to allow flexible modeling of the non-linear relationship. Autocorrelation of order 1 (AR(1)) was used as the correlation structure between repeated BMI measures and maximum likelihood estimation was implemented. The number of obesity-related risk C alleles of FTO (0,1 or 2), age, number of obesity-related risk alleles of FTO×age, sex, sex×age, smoking status and physical activity were entered in the model. Since the BLSA spans a long time period, birth year was additionally adjusted for in the model to account for potential confounding cohort effects of nutrition and lifestyles. Finally, a log-likelihood ratio test was used to test the significance of number of obesity-related risk alleles of FTO×age interaction.

Mixed-effects models were used to investigate the association between number of obesity-related risk alleles of FTO and longitudinal changes in impulsivity-related traits and macronutrient intake. The follow-up interval was used as the time metric and included in the model as a random-effects term. Covariates in the impulsivity analysis included age at baseline (centered at 60), sex, age×time, sex×time and the number of years of education (centered at 16). In the light of a previous study among BLSA participants showing an association between longitudinal changes in BMI and impulsivity24, individual slope of BMI change was added in the model to test whether any observed effects of number of obesity-related risk alleles of FTO on longitudinal changes in impulsivity would attenuate. Separate analyses were conducted for the four impulsivity-related traits. Covariates in macronutrient intake analysis included age at baseline (centered at 60), sex, age×time, sex×time. The year of baseline visit (centered at 1980) was additionally adjusted for in the model to account for potential confounding by secular trends of nutrition intake. Separate analyses were conducted for the three macronutrients: fat, carbohydrate, and protein. All analyses were performed using STATA version 12 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

FTO genotype and longitudinal changes in BMI during aging

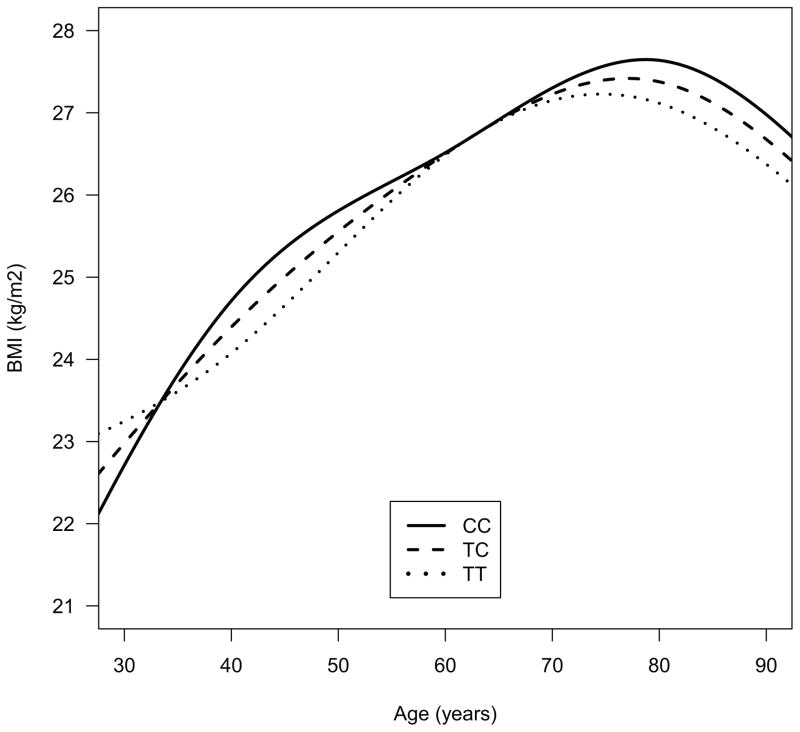

Demographic characteristics of participants in the BLSA are shown in Table 1. FTO genotype groups were well balanced. Frequencies of genotypes in rs1421085 were T/T in 226 participants (32.4%), C/T in 336 participants (48.2%), and C/C in 135 participants (19.4%) (Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) p=0.61). The frequency of the obesity-related risk (C) allele was 43.5%. Trajectories of BMI over time were significantly different between obesity risk allele non-carriers, heterozygous and homozygous individuals (likelihood ratio test: χ2=13.7, df=4, p=0.008) (Fig. 2). The peak BMI was highest in homozygous carriers, lowest in non-carriers and intermediate in heterozygous individuals. These results were similar in dominant models where FTO+ individuals showed significantly different trajectories of change in BMI as well as a higher peak BMI in comparison to FTO− participants (data not shown).

Figure 2.

The effect of FTO genotype (rs1421085 single nucleotide polymorphism; obesity-risk allele-C) on age- and sex-adjusted trajectories of body mass index (BMI) during aging. Trajectories of BMI over time were significantly different between obesity risk allele non-carriers, heterozygous and homozygous individuals (likelihood ratio test: χ2=13.7, df=4, p=0.008)

FTO genotype and longitudinal changes in brain function during aging

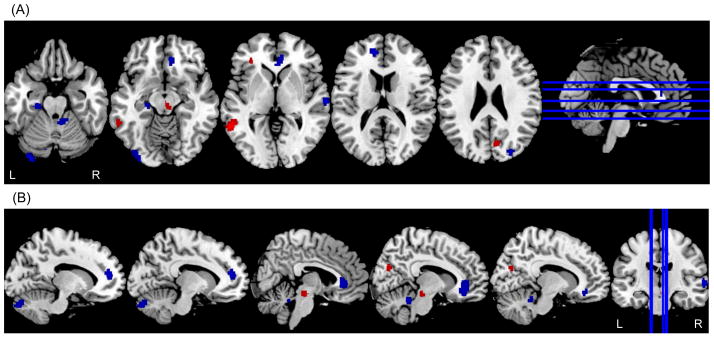

There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics between the FTO+ and FTO− participants in the 15O-water PET studies (Supplementary Table 2). The FTO+ group showed significantly greater rCBF declines over time relative to the FTO− group in several brain regions including bilateral anterior cingulate gyri (BA24, BA32), right orbitofrontal gyrus (BA10), right inferior parietal gyrus (BA40), right superior temporal gyrus (BA21), left parahippocampal gyrus (BA35), and right occipital/peristriate region (BA19) (Supplementary Table 3 and Fig. 3). Significantly greater rCBF increments over time in the FTO+ group were found relative to the FTO− group in a few regions, including the left inferior frontal gyrus (BA45), left middle temporal gyrus (BA 21), and right cuneus (BA21).

Figure 3.

Differences in longitudinal changes in regional resting state cerebral blood flow (rCBF) between obesity risk allele carriers (FTO+) and non-carriers (FTO−). Blue areas indicate brain regions that show significantly greater longitudinal decreases in rCBF in the FTO+ group; red areas indicate brain regions that show greater longitudinal increases in rCBF in the FTO+ group. (A) axial view (B) sagittal view.

In sensitivity analyses, we confirmed that these results remained unchanged after additional adjustment for concurrent mean BMI, overall cardiovascular risk, APOE ε4 status and tissue volume in each of the observed brain regions showing significant differences in longitudinal rCBF changes.

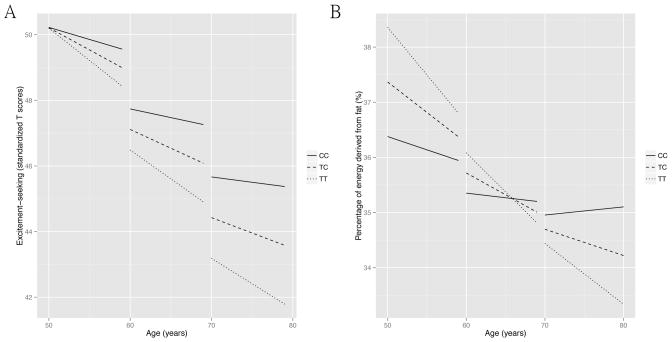

FTO genotype and longitudinal changes in impulsivity and food intake during aging

Based on the pattern of greater longitudinal decreases in rCBF in the FTO+ group within bilateral medial prefrontal cortical regions known to be associated with impulse control, we tested whether the FTO genotype would be associated with changes in impulsivity during aging. In general, most measures of impulsivity were found to decrease over time in both groups. These included decreases in ‘Impulsiveness (N5)’ and ‘Excitement-Seeking (E5)’ and increments in ‘Deliberation (C6) (Supplementary Table 4A). We observed that the presence of obesity-related risk allele(s) of FTO was associated with attenuation of decline in ‘Excitement-Seeking (E5)’ behavior (β(SE)=0.06(0.03), t=2.21, P=0.027, effect size=2) after adjustment for baseline age (centered at 60), sex, baseline age×time, race, years of education (centered at 16). The largest effect on ‘excitement-seeking’ was observed in homozygous risk allele carriers, least in non-carriers and intermediate in heterozygous individuals (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Table 4A). These results remained unchanged after adjustment for individual slopes of BMI change over time.

Figure 4.

The effect of FTO genotype (rs1421085 single nucleotide polymorphism; obesity-risk allele-C) on trajectories of excitement-seeking (A) and fat intake (B) during aging from the mixed-effects models. The trajectories were presented at 3 different baseline age periods: 50–60, 60–70, 70–80 years of age. A. In general, excitement-seeking decreased as age increased. The presence of obesity risk alleles was associated with less decrease in excitement-seeking over time in all age periods. B. Similarly, fat intake decreased during aging. In general, the presence of obesity risk alleles was associated with less decrease in fat intake over time and at later age periods, 70–80 years of age, homozygous risk alleles carriers even showed increase in fat intake over time.

Based on the pattern of longitudinal decreases in rCBF in FTO+ individuals within the orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate cortices, brain regions that contain taste neurons sensitive to food-related stimuli 25, 26, we asked whether the obesity related risk allele of FTO influenced longitudinal differences in dietary patterns during aging. In general, after adjustment for baseline age (centered at 60), sex, baseline age×time, years of baseline visit (centered at 1980), we found that the contribution of fats to total energy intake tended to decrease over time and in contrast, that from carbohydrates increased over time in all participants (Supplementary Table 4B). However, the presence of obesity related risk allele(s) of FTO was associated with attenuation of decline and even increases in fat contribution to energy intake over time at older ages (β (SE)=0.06 (0.03), t=2.41, P=0.016, effect size=2) (Fig. 4B, table S5). On the other hand, the FTO+ group showed a trend towards attenuation of the observed increase in carbohydrate contribution to energy intake over time (β (SE)= 0.06 (0.03), t= 1.88, P=0.06, effect size=2) (Supplementary Fig. 1). Again, these effects were strongest in homozygous individuals, least in non-carriers and intermediate in heterozygous participants. After adjustment for individual slopes of BMI change over time, the results remained similar to the primary analyses.

Finally, we conducted similar analyses for all outcome variables with another SNP of FTO gene (rs9939609) and all results remained the same (please refer to the supplementary material for detailed results).

Discussion

Our findings of pleiotropic longitudinal effects of the obesity-gene FTO are perhaps the first such demonstration of its influence on brain function, personality and diet in an older population. Besides showing that its influence on adiposity is persistent during aging, we find that FTO genotype is associated with reduced brain function in the medial prefrontal cortex. We suggest that these reductions in medial prefrontal cortical function mediate both increasing impulsivity as well as a greater preference for dietary fat over time during aging.

Our findings are especially relevant given that most previous studies on FTO and adiposity have been cross-sectional. Moreover, relatively few studies have been carried out primarily in older individuals27–30. It is estimated that about 35% of adults aged 65 and over in the United States were obese in 2007–2010, representing over 8 million adults 31. It is well known that the obese elderly population incurs higher health care costs and experiences greater disability 32. The population-attributable risk of obesity due to FTO is estimated to be about 20% 33. Approximately sixteen percent of individuals of European ancestry are homozygous for obesity related risk alleles of FTO and are at 67% higher risk for obesity 34. Our observation of a robust and persistent influence of FTO genotype on longitudinal changes in adiposity in older individuals therefore implicates this common genetic variation as a key biological basis of predilection to obesity during aging. It is however worth noting in this context that besides genetic influences on trajectories of BMI, environmental factors may play a key role in determining adiposity during aging 35, 36.

The implications of reduced function in the medial prefrontal cortex include increased impulsivity, encompassing behavioral disinhibition, risky decision-making and abnormalities in delay-discounting 37–39. Given our previous observation in the BLSA of a relationship between impulsivity and BMI 40, as well as our current finding of an effect of FTO genotype on adiposity, we confirmed that this association was independent of changes in BMI. As neurons in the mPFC have also been reported to mediate food-related responses evoked by taste, oral texture and olfactory stimuli 25, 26, 41, our current findings suggest that reduced mPFC function may be a common neural substrate mediating the effects of FTO genotype on both impulsivity and macronutrient intake. While our findings suggest that reduced mPFC function may be a plausible mechanism underlying FTO-associated changes in impulsivity and diet during aging, these results warrant further confirmation in independent studies. Hess and colleagues recently reported that the FTO gene regulates midbrain dopaminergic neuronal activity. Moreover, FTO knockout mice show attenuated quinpirole-mediated reduction of locomotion and enhanced sensitivity to both the locomotor and reward stimulatory actions of cocaine 42. Furthermore, dopaminergic cells in the ventral tegmental area receive direct projections from the mPFC and dopaminergic responses to reward-predicting cues are enhanced by functional inactivation of the mPFC 43. It is plausible therefore that the function of the mPFC, a major target of mesocorticolimbic dopamine neurons 44, can be modulated by FTO genotype with net effects on reward-seeking behavior.

In summary, we have shown that a commonly carried obesity risk variant of FTO exerts pleiotropic longitudinal effects on several intermediate phenotypes relevant to human health and disease states during aging. Its role in reduced medial prefrontal cortical brain function suggests a common neural mechanism underlying obesity-associated impulsivity and increased consumption of high calorie foods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging participants and neuroimaging staff for their dedication to these studies and the staff of the Johns Hopkins University PET facility for their assistance. This work was supported in part by research and development contract N01-AG-3-2124 from the Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors confirm that they do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary information is available at Molecular Psychiatry’s website.

References

- 1.Puhl RM, Peterson JL, DePierre JA, Luedicke J. Headless, hungry, and unhealthy: a video content analysis of obese persons portrayed in online news. J Health Commun. 2013;18(6):686–702. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.743631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Decaria JE, Sharp C, Petrella RJ. Scoping review report: obesity in older adults. International journal of obesity. 2012;36(9):1141–1150. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hassing LB, Dahl AK, Pedersen NL, Johansson B. Overweight in midlife is related to lower cognitive function 30 years later: a prospective study with longitudinal assessments. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;29(6):543–552. doi: 10.1159/000314874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitmer RA, Gunderson EP, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Zhou J, Yaffe K. Body mass index in midlife and risk of Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2007;4(2):103–109. doi: 10.2174/156720507780362047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shock NW, Gruelich R, Andres R, Arenberg D, Costa PT, Lakatta E, et al. The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1984. Normal human aging. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jueptner M, Weiller C. Review: does measurement of regional cerebral blood flow reflect synaptic activity? Implications for PET and fMRI. Neuroimage. 1995;2(2):148–156. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1995.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrucci L. The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA): a 50-year-long journey and plans for the future. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2008;63(12):1416–1419. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.12.1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawas C, Gray S, Brookmeyer R, Fozard J, Zonderman A. Age-specific incidence rates of Alzheimer’s disease: the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Neurology. 2000;54(11):2072–2077. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.11.2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-III-R. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Resnick SM, Goldszal AF, Davatzikos C, Golski S, Kraut MA, Metter EJ, et al. One-year age changes in MRI brain volumes in older adults. Cerebral cortex. 2000;10(5):464–472. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.5.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dina C, Meyre D, Gallina S, Durand E, Korner A, Jacobson P, et al. Variation in FTO contributes to childhood obesity and severe adult obesity. Nature genetics. 2007;39(6):724–726. doi: 10.1038/ng2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frayling TM, Timpson NJ, Weedon MN, Zeggini E, Freathy RM, Lindgren CM, et al. A common variant in the FTO gene is associated with body mass index and predisposes to childhood and adult obesity. Science. 2007;316(5826):889– 894. doi: 10.1126/science.1141634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scuteri A, Sanna S, Chen WM, Uda M, Albai G, Strait J, et al. Genome-wide association scan shows genetic variants in the FTO gene are associated with obesity-related traits. PLoS genetics. 2007;3(7):e115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho AJ, Stein JL, Hua X, Lee S, Hibar DP, Leow AD, et al. A commonly carried allele of the obesity-related FTO gene is associated with reduced brain volume in the healthy elderly. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(18):8404–8409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910878107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kivimaki M, Jokela M, Hamer M, Geddes J, Ebmeier K, Kumari M, et al. Examining overweight and obesity as risk factors for common mental disorders using fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) genotype-instrumented analysis: The Whitehall II Study, 1985–2004. American journal of epidemiology. 2011;173(4):421–429. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terracciano A, Balaci L, Thayer J, Scally M, Kokinos S, Ferrucci L, et al. Variants of the serotonin transporter gene and NEO-PI-R Neuroticism: No association in the BLSA and SardiNIA samples. American journal of medical genetics Part B, Neuropsychiatric genetics : the official publication of the International Society of Psychiatric Genetics. 2009;150B(8):1070–1077. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melzer D, Perry JR, Hernandez D, Corsi AM, Stevens K, Rafferty I, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies protein quantitative trait loci (pQTLs) PLoS genetics. 2008;4(5):e1000072. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGandy RB, Barrows CH, Jr, Spanias A, Meredith A, Stone JL, Norris AH. Nutrient intakes and energy expenditure in men of different ages. Journal of gerontology. 1966;21(4):581–587. doi: 10.1093/geronj/21.4.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costa PT, MacCrae RR. Psychological Assessment Resources I. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO FFI): Professional Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources. 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hallfrisch J, Muller D, Drinkwater D, Tobin J, Andres R. Continuing diet trends in men: the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (1961–1987) Journal of gerontology. 1990;45(6):M186–191. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.6.m186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tucker KL, Hallfrisch J, Qiao N, Muller D, Andres R, Fleg JL, et al. The combination of high fruit and vegetable and low saturated fat intakes is more protective against mortality in aging men than is either alone: the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. The Journal of nutrition. 2005;135(3):556–561. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.3.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D and the R Development Core Team. nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. R package version 31. 108:2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sutin AR, Costa PT, Jr, Chan W, Milaneschi Y, Eaton WW, Zonderman AB, et al. I Know Not To, but I Can’t Help It: Weight Gain and Changes in Impulsivity-Related Personality Traits. Psychological science. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0956797612469212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rolls ET. Functions of the orbitofrontal and pregenual cingulate cortex in taste, olfaction, appetite and emotion. Acta Physiol Hung. 2008;95(2):131–164. doi: 10.1556/APhysiol.95.2008.2.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rolls ET, Yaxley S, Sienkiewicz ZJ. Gustatory responses of single neurons in the caudolateral orbitofrontal cortex of the macaque monkey. J Neurophysiol. 1990;64(4):1055–1066. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.64.4.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albuquerque D, Nobrega C, Manco L. Association of FTO polymorphisms with obesity and obesity-related outcomes in Portuguese children. PloS one. 2013;8(1):e54370. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunt SC, Stone S, Xin Y, Scherer CA, Magness CL, Iadonato SP, et al. Association of the FTO gene with BMI. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(4):902–904. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ntalla I, Panoutsopoulou K, Vlachou P, Southam L, William Rayner N, Zeggini E, et al. Replication of established common genetic variants for adult BMI and childhood obesity in Greek adolescents: the TEENAGE study. Ann Hum Genet. 2013;77(3):268–274. doi: 10.1111/ahg.12012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silventoinen K, Kaprio J. Genetics of tracking of body mass index from birth to late middle age: evidence from twin and family studies. Obes Facts. 2009;2(3):196–202. doi: 10.1159/000219675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fakhouri TH, Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity among older adults in the United States, 2007–2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012;(106):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American Federation for Aging R. Boom, Boom, Boom : obesity among baby boomers and older adults : issues and options. American Federation for Aging Research; New York, N.Y: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li S, Loos RJ. Progress in the genetics of common obesity: size matters. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2008;19(2):113–121. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3282f6a7f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cecil JE, Tavendale R, Watt P, Hetherington MM, Palmer CN. An obesity-associated FTO gene variant and increased energy intake in children. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;359(24):2558–2566. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glass TA, Rasmussen MD, Schwartz BS. Neighborhoods and obesity in older adults: the Baltimore Memory Study. American journal of preventive medicine. 2006;31(6):455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rampersaud E, Mitchell BD, Pollin TI, Fu M, Shen H, O’Connell JR, et al. Physical activity and the association of common FTO gene variants with body mass index and obesity. Archives of internal medicine. 2008;168(16):1791–1797. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.16.1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tabara Y, Osawa H, Guo H, Kawamoto R, Onuma H, Shimizu I, et al. Prognostic significance of FTO genotype in the development of obesity in Japanese: the J-SHIPP study. International journal of obesity. 2009;33(11):1243–1248. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reynolds B, Ortengren A, Richards JB, de Wit H. Dimensions of impulsive behavior: Personality and behavioral measures. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;40(2):305–315. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swann AC, Bjork JM, Moeller FG, Dougherty DM. Two models of impulsivity: relationship to personality traits and psychopathology. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51(12):988–994. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01357-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sutin AR, Costa PT, Jr, Chan W, Milaneschi Y, Eaton WW, Zonderman AB, et al. I Know Not To, but I Can’t Help It: Weight Gain and Changes in Impulsivity-Related Personality Traits. Psychological science. 2013;24(7):1323–1328. doi: 10.1177/0956797612469212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keller L, Xu W, Wang HX, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L, Graff C. The obesity related gene, FTO, interacts with APOE, and is associated with Alzheimer’s disease risk: a prospective cohort study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;23(3):461–469. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-101068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hess ME, Hess S, Meyer KD, Verhagen LA, Koch L, Bronneke HS, et al. The fat mass and obesity associated gene (Fto) regulates activity of the dopaminergic midbrain circuitry. Nature neuroscience. 2013;16(8):1042– 1048. doi: 10.1038/nn.3449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jo YS, Lee J, Mizumori SJ. Effects of prefrontal cortical inactivation on neural activity in the ventral tegmental area. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013;33(19):8159–8171. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0118-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steketee JD. Neurotransmitter systems of the medial prefrontal cortex: potential role in sensitization to psychostimulants. Brain research Brain research reviews. 2003;41(2–3):203–228. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00233-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.