Background: The synaptic vesicle protein, SV2A, participates in the regulation of neurotransmitter release, but its exact function is unclear.

Results: Human SV2A expressed in yeast functions as a specific transporter of the 6-carbon sugar, galactose.

Conclusion: The galactose transport capability of SV2A may play an important role in modulating synaptic function.

Significance: This is the first demonstration of a transporter activity for SV2A.

Keywords: Drug Action, Galactose, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Sugar Transport, Synapse, SV2A, Levetiracetam

Abstract

SV2A is a synaptic vesicle membrane protein expressed in neurons and endocrine cells and involved in the regulation of neurotransmitter release. Although the exact function of SV2A still remains elusive, it was identified as the specific binding site for levetiracetam, a second generation antiepileptic drug. Our sequence analysis demonstrates that SV2A has significant homology with several yeast transport proteins belonging to the major facilitator superfamily (MFS). Many of these transporters are involved in sugar transport into yeast cells. Here we present evidence showing, for the first time, that SV2A is a galactose transporter. We expressed human SV2A in hexose transport-deficient EBY.VW4000 yeast cells and demonstrated that these cells are able to grow on galactose-containing medium but not on other fermentable carbon sources. Furthermore, the addition of the SV2A-binding antiepileptic drug levetiracetam to the medium inhibited the galactose-dependent growth of hexose transport-deficient EBY.VW4000 yeast cells expressing human SV2A. Most importantly, direct measurement of galactose uptake in the same strain verified that SV2A is able to transport extracellular galactose inside the cells. The newly identified galactose transport capability of SV2A may have an important role in regulating/modulating synaptic function.

Introduction

Synaptic vesicle protein 2 (SV2)2 is an integral transmembrane glycoprotein expressed in neurons and endocrine cells (1). In neurons, SV2 is localized to synaptic vesicles and has been proposed to function as a modulator of Ca2+-dependent neurotransmitter release (2).

SV2 has three isoforms, A, B, and C, with SV2A being the most widely expressed in the brain (2). Of the three known isoforms, SV2A is ubiquitously expressed in the rat brain, whereas SV2B, although widely expressed, is undetectable in several groups of neurons in the hippocampus, central gray nuclei, and cerebellum (3). SV2C has a much more restricted distribution being found mostly in the basal ganglia, midbrain, and brainstem (2).The most studied isoform, SV2A, has been shown to regulate the expression and trafficking of the synaptic vesicle calcium sensor protein, synaptotagmin (4). Synaptotagmin is required for the calcium-mediated exocytosis of neurotransmitters stored in synaptic vesicles (5). SV2A also plays a synaptotagmin-independent role in neurotransmitter release, most likely functioning in a maturation step of primed synaptic vesicles that converts the vesicles into a Ca2+- and synaptotagmin-responsive state (6). The exact function of SV2A, however, still remains elusive. SV2A was identified as the specific binding site for levetiracetam, a second generation antiepileptic drug (7). Levetiracetam reduces presynaptic glutamate release particularly in neurons with a sustained and high frequency firing (7–9), and it was shown that the antiepileptic efficacy of levetiracetam and its derivatives correlates with their binding affinity to SV2A (7).

SV2 has 12 transmembrane domains, and the N-terminal half of the protein shows significant amino acid sequence identity to a family of bacterial proteins that transport sugars, citrate, and drugs (1), and also to mammalian glucose transporters (1, 10). A transport function for any of the SV2 isoforms, however, has not been demonstrated. Our sequence analysis studies revealed that several yeast proteins of the major facilitator superfamily (MFS) of transport proteins have significant homology to SV2A. Many of these transporters have been shown to be involved in sugar transport into yeast. Because human proteins can easily be expressed in yeast, we decided to express SV2A in a Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain that specifically lacks each hexose transport protein and assayed for its functional role based on the growth in different carbon sources. In the present study we show for the first time that human SV2A, when expressed in yeast, functions as a galactose transporter. Moreover, the antiepileptic drug levetiracetam, which specifically binds to SV2A (7), inhibits the galactose-dependent growth of SV2A-expressing yeast cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Homology Analysis

Homology analysis was conducted with the widely used multiple-sequence alignment program, Pileup. The Pileup program (which is part of the GCG package) is a progressive pairwise alignment program based on Feng and Doolittle algorithm (11).

Media and Growth Conditions

Standard yeast media were used in all growth experiments. Yeast strains without plasmids were grown in rich medium (YPL), which contains 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 3% lactate. Strains containing plasmids requiring uracil auxotrophic marker selection were grown in synthetic complete (SC) medium lacking uracil (−ura). Synthetic complete medium contained 6.7 mg/ml yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 5 mg/ml ammonium sulfate, all amino acids, no uracil, and the required carbon source, pH 5.5–6.

Plasmid Construction

The human SV2A (hSV2A), with a 5′-BamHI and 3′-NotI site at each end, was made by PCR amplification from human SV2A ORF without stop codon purchased from Thermo Scientific (Clone ID: 100066518) and ligated in-frame into the BamHI- and NotI-digested pCM188 vector. pCM188 is a yeast centromeric expression vector driven by the tetO-CYC1 promoter.

Complementation Study

Yeast cells, EBY.VW4000 strain (strain that lacks each hexose transport protein) (12) and EBY.VW4000 harboring recombinant vector pCM188-hSV2A or the empty vector pCM188, were grown in YPL and SL−ura media, respectively (where SL−ura indicates synthetic complete medium supplemented with lactate as carbon source with no uracil), to A600 of 2. 5 × 106 cells were washed twice with sterile water and finally resuspended in 300 μl of water. Strains were serially diluted 10-fold. Cells were transferred to solid synthetic complete media containing the specific carbon source: 2% glucose, 2% galactose, 2% raffinose, 2% sucrose, 2% mannose, 1% fructose, 3% lactate, or 3% glycerol, in triplicate, by using a 36-pin replicator, and plates were incubated at 30 °C for 2–4 days.

Levetiracetam Treatment

Transformant strains were grown to log phase in SC−ura medium supplemented with 3% lactate (SL−ura), whereas EBY.VW4000 strain was grown in YPL medium. 5 × 106 cells were harvested, washed twice with sterile water, and finally resuspended in 300 μl of sterile water. Strains were serially diluted 10-fold. Cells were plated on solid synthetic complete medium supplemented with 2% galactose and levetiracetam (Sigma-Aldrich). The drug was added at different concentrations (1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 μm).

Assay of Galactose Transport

For uptake, cells were grown in SC−ura medium with 3% lactate to A600 of 0.6, harvested, and resuspended in liquid SC−ura medium with 3% glycerol. Galactose transport was measured by using techniques adapted from Chattopadhyay and Pearce (13). Each experiment was repeated independently 3–4 times to determine statistical significance. Cells were aliquoted to 1.4 ml, and 200 μl was pipetted onto a Whatman GF/C filter on a Millipore vacuum manifold for the 0 s/min time point. To determine the time course of galactose uptake, 15 μl of [14C]galactose (55.5 mCi/mmol, PerkinElmer) and 14 μl of 10 mm unlabeled galactose (100 μm total substrate) were added to each sample to start the reaction. Aliquots were taken at different time points (2, 5, 10, 15, 30, and 45 min). For Vmax and Km determination, cells were incubated with increasing galactose concentrations (1, 5, 15, 50, and 100 μm) for 1 min. The uptake was stopped by washing the cells twice with cold synthetic medium (2% galactose, 20 mg/ml histidine, 20 mg/ml uracil, 20 mg/ml tryptophan). Radioactivity was measured in a Beckman LS 6500 liquid scintillation counter. Nonlinear regression, curve fitting, and Vmax and Km calculation were performed using GraphPad Prism 5. To test the sensitivity of galactose uptake to the protonophore, carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP), cells were preincubated with CCCP for 1 min before the addition of galactose.

RESULTS

Up to now SV2A function has remained elusive. We performed sequence analysis with the widely used multiple-sequence alignment Pileup program and found that SV2A has significant homology with several yeast transport proteins belonging to the major facilitator superfamily (Table 1). Most of these transporters have been shown to be involved in sugar transport into yeast. Therefore, we tested whether human SV2A functions as a sugar transporter.

TABLE 1.

Yeast genes/proteins showing significant homology to SV2A and their putative function

| Name | Homology to SV2Aa | Function |

|---|---|---|

| % | ||

| HXT3 | 25 | Fructose/glucose transporter |

| PHO84 | 25 | High affinity inorganic phosphate (Pi) transporter; arsenic resistance |

| ITR2 | 23 | myo-Inositol transporter |

| HXT15 | 22 | Likely sugar transporter |

| HXT16 | 22 | Likely sugar transporter |

| ITR1 | 22 | myo-Inositol transporter |

| HXT5 | 23 | Likely sugar transporter |

| HXT13 | 22 | Likely sugar transporter |

| HXT17 | 22 | Likely sugar transporter |

| RGT2 | 32 (over 100 aa) | Glucose transporter |

| MAL31 | 23 | Maltose transporter |

| GAL2 | 24 | Galactose transporter |

| HXT1 | 22 | Low affinity glucose transporter |

| MPH3 | 24 | α-Glucoside permease, transports maltose, maltotriose, α-methylglucoside, and turanose |

| SNF3 | 24 (over 100 aa) | Glucose sensor |

| HXT7 | 23 | High affinity glucose transporter |

| HXT6 | 23 | High affinity glucose transporter |

| HXT10 | 22 | Likely sugar transporter |

| YDR387c | 24 | Unknown |

| HXT2 | 24 | High affinity glucose transporter |

| AQR1 | 19 (over 100 aa) | Transporter |

| QDR2 | 20 (over 100 aa) | Multidrug transporter |

| HXT4 | 24 | High affinity glucose transporter |

| HXT8 | 24 (over 100 aa) | Likely sugar transporter |

| YBR241C | 20 (over 100 aa) | Unknown |

| QDR1 | 18 (over 100 aa) | Multidrug transporter |

| HXT11 | 20 | Likely sugar transporter |

| STL1 | 20 | Likely sugar transporter |

| HXT9 | 21 (over 100 aa) | Likely sugar transporter |

| SR077 | 25 (over 100 aa) | Unknown |

| SGE1 | 22 (over 100 aa) | Multidrug transporter |

| HXT12 | 20 | Likely sugar transporter |

| YDL199c | 24 | Unknown |

| TPO1 | 17 | Polyamine transporter |

| QDR3 | 17 | Unknown |

| TPO3 | 18 (over 100 aa) | Polyamine transporter |

| MCH5 | 20 (over 100 aa) | Possible monocarboxylic transporter |

| TPO2 | 18 (over 100 aa) | Polyamine transporter |

a Homology over at least 200 amino acids (aa) unless otherwise indicated.

Hexose Transport-deficient EBY.VW4000 Yeast Cells Expressing Human SV2A Are Able to Grow on Synthetic Medium Containing 2% Galactose—

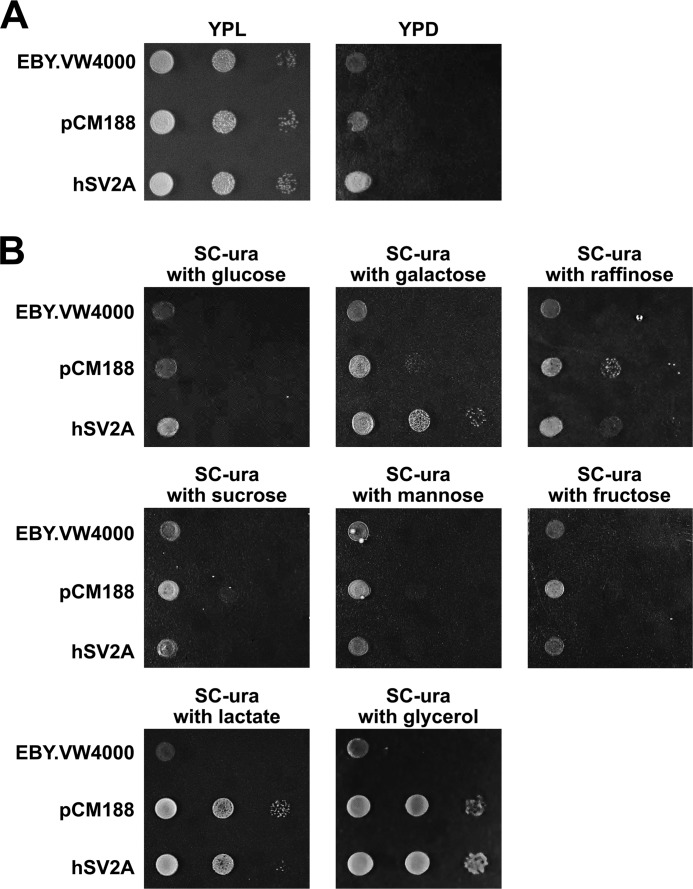

To determine whether human SV2A functions as a sugar transporter, we utilized the EBY.VW4000 yeast (S. cerevisiae) strain, which lacks all hexose transporters (12). We generated EBY.VW4000 cells harboring the empty centromeric plasmid pCM188 or expressing human SV2A in the pCM188 plasmid. EBY.VW4000 cells were plated on rich YP medium containing either 3% lactate or 2% glucose. EBY.VW4000 yeast cells showed normal growth on lactate-containing medium and defective growth on glucose-containing medium (Fig. 1A). Expression of hSV2A did not rescue the growth defect on glucose-containing medium (Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1.

The growth of hexose transport-deficient EBY.VW4000 yeast cells expressing human SV2A is galactose-dependent. A, the EBY.VW4000 yeast strain, which lacks all hexose transporters, shows normal growth on lactate-containing (YPL) medium and defective growth on glucose-containing (YPD) medium, and expression of hSV2A does not rescue the growth defect on YPD. 10-fold serial dilutions of EBY.VW4000 yeast cells, EBY.VW4000 cells harboring the empty centromeric plasmid pCM188, or EBY.VW4000 cells expressing hSV2A in the pCM188 plasmid were plated on rich YP medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone) containing either 3% lactate (YPL) or 2% glucose (YPD). B, hexose transport-deficient EBY.VW4000 yeast cells expressing hSV2A are able to grow on synthetic medium containing 2% galactose. SV2A expression does not rescue the growth defect if the synthetic medium contains other 6-carbon sugars. 10-fold serial dilutions of EBY.VW4000 yeast cells and EBY.VW4000 cells harboring the empty centromeric plasmid pCM188 or expressing human SV2A in the pCM188 plasmid were plated onto SC medium lacking uracil (−ura) and supplemented with 2% glucose, galactose, raffinose, sucrose, mannose, and fructose, respectively. The same strains were plated on synthetic complete medium containing either 3% lactate or 3% glycerol to test hexose-independent, normal growth. Plates were incubated at 30 °C for 48 h.

Then we compared the growth of hexose transport-deficient EBY.VW4000 yeast cells and EBY.VW4000 cells harboring the empty pCM188 plasmid or expressing human SV2A in the pCM188 plasmid on SC medium lacking uracil supplemented with various carbon sources. hSV2A-expressing cells were able to grow on synthetic medium containing 2% galactose, but hSV2A expression did not rescue the growth defect if the synthetic medium contained other 6-carbon sugars (Fig. 1B). EBY.VW4000 yeast cells were also plated on synthetic complete medium containing either 3% lactate or 3% glycerol to test hexose-independent, normal growth (Fig. 1B, bottom two images). Note that only the yeast cells harboring the pCM188 expression vector are able to grow normally on the uracil-lacking (−ura) media. pCM188 contains the URA3 gene required for the biosynthesis of uracil, and EBY.VW4000 cells are ura3−.

The Antiepileptic Drug Levetiracetam Inhibits the Galactose-dependent Growth of Hexose Transport-deficient Yeast Cells Expressing Human SV2A

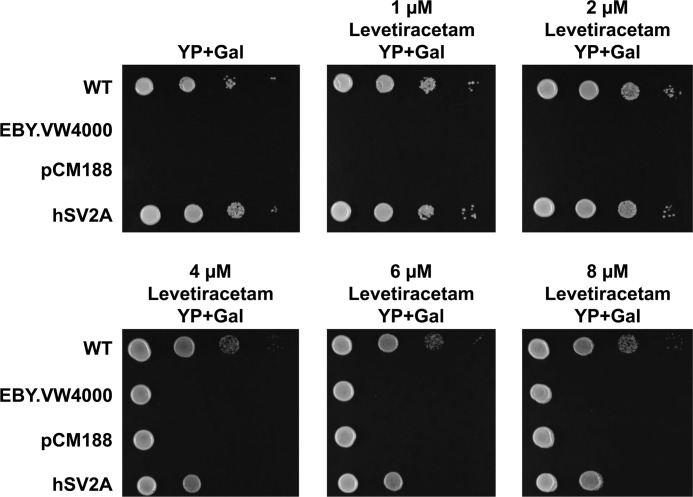

The antiepileptic drug levetiracetam specifically binds to SV2A and modulates its function (7–9). We found that the growth of hSV2A-expressing, hexose transport-deficient yeast cells on 2% galactose-containing medium was concentration-dependently inhibited by levetiracetam (Fig. 2). These results strongly indicated that human SV2A expressed in yeast cells transports extracellular galactose into the cells. Variation in the growth of the negative controls (untransformed control and vector control) at the highest cell number plated (Fig. 2) is due to the fact that the effect of levetiracetam was tested in separate experiments, first at 0–2 μm and then at 4–8 μm.

FIGURE 2.

The antiepileptic drug, levetiracetam, inhibits the galactose-dependent growth of hexose transport-deficient EBY.VW4000 yeast cells expressing human SV2A. The growth of SV2A-expressing EBY.VW4000 yeast cells on 2% galactose-containing YP medium was concentration-dependently inhibited by levetiracetam, an antiepileptic drug, which specifically binds to SV2A.

Human SV2A Expressed in Yeast Cells Transports Galactose

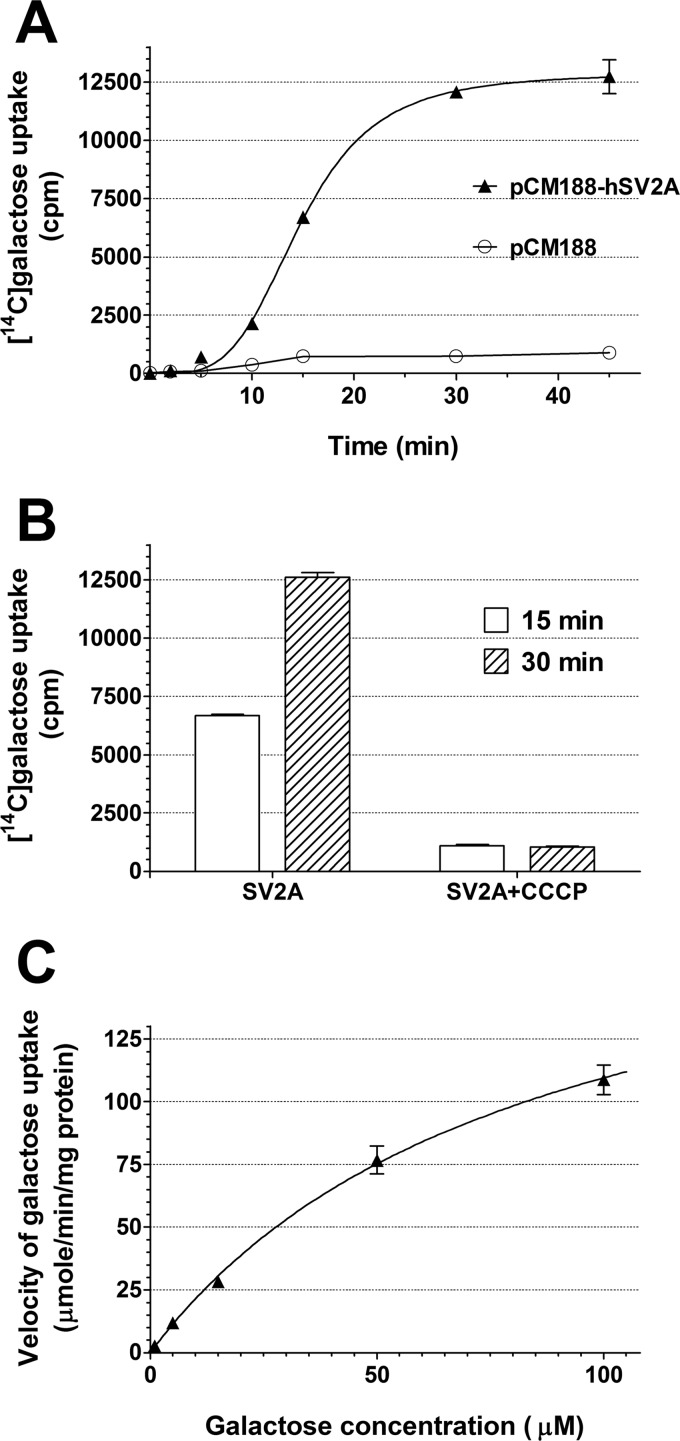

To test whether human SV2A indeed functions as a galactose transporter, the cellular uptake of [14C]galactose was measured in hexose transport-deficient EBY.VW4000 yeast cells either harboring the empty plasmid pCM188 or expressing hSV2A in the pCM188 plasmid. Time-dependent, significant cellular uptake of [14C]galactose could only be measured in hSV2A-expressing cells (Fig. 3A). The time course of galactose uptake was sigmoidal, suggesting an allosteric activation of the transport function of hSV2A. To test whether the hSV2A-mediated galactose uptake is coupled to proton transport, we used the protonophore, CCCP. CCCP (10 μm) completely blocked the transport by hSV2A (Fig. 3B). Kinetic analysis of the hSV2A-mediated galactose uptake (Fig. 3C) revealed a Vmax of 201 ± 13 (S.E.) μmol/min/mg of protein and a Km of 84 ± 10 (S.E.) μm.

FIGURE 3.

Human SV2A expressed in yeast cells transports galactose. The cellular uptake of [14C]galactose was measured in hexose transport-deficient EBY.VW4000 yeast cells either harboring the empty centromeric plasmid pCM188 or expressing human SV2A in the pCM188 vector. Cells were grown in liquid synthetic complete medium lacking uracil (SC−ura) and supplemented with 3% lactate, to A600 of 0.6, and then harvested and resuspended in liquid SC−ura medium supplemented with 3% glycerol. Galactose uptake was initiated by adding [14C]galactose to the medium, and radioactivity in the cells was measured at different time points. A, time-dependent, significant cellular uptake of [14C]galactose could only be measured in hSV2A-expressing cells. Symbols and bars represent mean ± S.D. (n = 5). B, the hSV2A-mediated galactose uptake is coupled to proton transport. [14C]Galactose uptake by hSV2A was measured in the absence or presence of the protonophore, CCCP (10 μm), for 15 and 30 min. Columns and bars represent mean ± S.D. (n = 5). C, Michaelis-Menten plot of hSV2A-mediated galactose uptake. Symbols and bars represent mean ± S.D. (n = 4–5). In A and C, curve fittings by nonlinear regression were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.

DISCUSSION

In this study we demonstrate for the first time that SV2A, a synaptic vesicle membrane protein involved in the regulation of neurotransmitter release, is a galactose transporter. We performed, as a starting point, sequence analysis studies and found that human SV2A shares significant homology with several yeast transport proteins belonging to the major facilitator superfamily. We present three lines of evidence for the galactose transport function of SV2A. First, when human SV2A is expressed in hexose transport-deficient EBY.VW4000 yeast cells, these cells are able to grow on galactose-containing medium, but SV2A expression does not rescue the growth defect if the medium contains other 6-carbon sugars (Fig. 1). Moreover, the addition of the antiepileptic drug levetiracetam (which specifically binds to SV2A (7)) inhibits the galactose-dependent growth of hexose transport-deficient EBY.VW4000 yeast cells expressing human SV2A (Fig. 2). More importantly, direct measurement of galactose uptake verified that SV2A transports extracellular galactose into the cells (Fig. 3).

In neurons, SV2A is sorted to synaptic vesicles via endosomal precursors, and when synaptic vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane to release their content, SV2A becomes a plasma membrane protein and stays there until it is recycled by endocytosis. In yeast cells, which do not have synaptic vesicles, recombinantly expressed SV2A is expected to localize to endosomes and, following exocytosis, to the plasma membrane as well. Our galactose uptake assay in hSV2A-expressing yeast cells clearly showed that hSV2A is in the plasma membrane, mediating the transport of extracellular galactose into the cell (Fig. 3A). Regarding the mechanism of transport, our finding that the protonophore CCCP blocks galactose uptake (Fig. 3B) indicates that SV2A functions as a proton-coupled symporter (CCCP would not affect a galactose uniporter, and because yeast cells maintain a low cytosolic H+ concentration by the plasma membrane proton pump, Pma1, CCCP should stimulate galactose uptake via an antiporter). Based on the above we propose that SV2A, as a transporter, has dual functions in neurons. First, due to the proton gradient across the synaptic vesicle membrane, SV2A is likely to function in the coupled transport of galactose (or a similar substrate) and protons out of synaptic vesicles into the cytoplasm, contributing to the control of vesicle lumen pH. Second, when synaptic vesicles fuse with the plasma membrane, SV2A can provide synapse-specific uptake of extracellular galactose.

SV2A is a neuronal protein, and its newly identified galactose transport function suggests that galactose has an important role in neuronal physiology. Galactose is incorporated into complex oligosaccharides of membrane and secretory glycoproteins in the Golgi, but galactose and some of its derivatives can also be added to proteins in the cytosol as transient or permanent post-translational modifications (14). The galactose-containing disaccharide, fucose-α(1-2)galactose, has been implicated in memory formation, learning, and synaptic plasticity (15–21). Fucose-α(1-2)galactose sugars are enriched on glycoproteins in presynaptic nerve terminals (22), and it has been shown that fucose-α(1-2)-galactose modification has profound effects on the expression and degradation of the synaptic vesicle-associated protein, synapsin (22). Furthermore, the importance of galactose for normal neuronal function is indicated by the fact that B27, the widely used serum replacement for primary neuronal cultures, contains galactose (23).

Abnormally enhanced glutamatergic neurotransmission is involved in the pathophysiology of epilepsy (24) and several neurodegenerative disorders, such as Parkinson disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Huntington disease, and Alzheimer disease (25, 26). SV2A gained particular attention when it was identified as the binding site for the antiepileptic drug, levetiracetam (7). It was also shown that the antiepileptic efficacy of levetiracetam and its derivatives correlated with their binding affinity to SV2A (7). Levetiracetam reduces presynaptic glutamate release particularly in neurons with a sustained and high frequency firing (8, 9). A neuroprotective role of SV2A modulation was also suggested by a recent study demonstrating that levetiracetam suppresses neuronal network dysfunction and reverses synaptic and cognitive deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease (27). The mechanism of how levetiracetam modulates SV2A function, however, is unclear. Our results indicate that levetiracetam inhibits the SV2A-mediated galactose transport, which may be its mechanism of action or a contributing factor to its antiepileptic and neuroprotective activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Boles for kindly providing the EBY.VW4000 yeast strain and Dr. Sergio Padilla-Lopez for helpful comments and for technical assistance during the course of this study. We also acknowledge initial discussions with Dr. Robert Gross, Department of Neurology, University of Rochester School of Medicine, that lead to this study.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants P20 GM103620 and NS36610 (to D. A. P.). This work was also supported by Sanford Health.

This article was selected as a Paper of the Week.

- SV2

- synaptic vesicle protein 2

- YPL

- yeast extract/peptone/lactate

- YPD

- yeast extract/peptone/dextrose

- SC

- synthetic complete

- hSV2A

- human SV2A

- CCCP

- carbonyl cyanide 3-chlorophenylhydrazone

- aa

- amino acids.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bajjalieh S. M., Peterson K., Shinghal R., Scheller R. H. (1992) SV2, a brain synaptic vesicle protein homologous to bacterial transporters. Science 257, 1271–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kwon S. E., Chapman E. R. (2012) Glycosylation is dispensable for sorting of synaptotagmin 1 but is critical for targeting of SV2 and synaptophysin to recycling synaptic vesicles. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 35658–35668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Crèvecoeur J., Kaminski R. M., Rogister B., Foerch P., Vandenplas C., Neveux M., Mazzuferi M., Kroonen J., Poulet C., Martin D., Sadzot B., Rikir E., Klitgaard H., Moonen G., Deprez M. (2014) Expression pattern of synaptic vesicle protein 2 (SV2) isoforms in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy and hippocampal sclerosis. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 40, 191–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yao J., Nowack A., Kensel-Hammes P., Gardner R. G., Bajjalieh S. M. (2010) Cotrafficking of SV2 and synaptotagmin at the synapse. J. Neurosci. 30, 5569–5578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kochubey O., Lou X., Schneggenburger R. (2011) Regulation of transmitter release by Ca2+ and synaptotagmin: insights from a large CNS synapse. Trends Neurosci. 34, 237–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chang W. P., Südhof T. C. (2009) SV2 renders primed synaptic vesicles competent for Ca2+-induced exocytosis. J. Neurosci. 29, 883–897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lynch B. A., Lambeng N., Nocka K., Kensel-Hammes P., Bajjalieh S. M., Matagne A., Fuks B. (2004) The synaptic vesicle protein SV2A is the binding site for the antiepileptic drug levetiracetam. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 9861–9866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang X. F., Weisenfeld A., Rothman S. M. (2007) Prolonged exposure to levetiracetam reveals a presynaptic effect on neurotransmission. Epilepsia 48, 1861–1869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Meehan A. L., Yang X., McAdams B. D., Yuan L., Rothman S. M. (2011) A new mechanism for antiepileptic drug action: vesicular entry may mediate the effects of levetiracetam. J. Neurophysiol. 106, 1227–1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Feany M. B., Lee S., Edwards R. H., Buckley K. M. (1992) The synaptic vesicle protein SV2 is a novel type of transmembrane transporter. Cell 70, 861–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Palacios G., Casas I., Tenorio A., Freire C. (2002) Molecular identification of enterovirus by analyzing a partial VP1 genomic region with different methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40, 182–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wieczorke R., Krampe S., Weierstall T., Freidel K., Hollenberg C. P., Boles E. (1999) Concurrent knock-out of at least 20 transporter genes is required to block uptake of hexoses in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 464, 123–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chattopadhyay S., Pearce D. A. (2002) Interaction with Btn2p is required for localization of Rsglp: Btn2p-mediated changes in arginine uptake in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot. Cell 1, 606–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Torre E. R., Steward O. (1996) Protein synthesis within dendrites: glycosylation of newly synthesized proteins in dendrites of hippocampal neurons in culture. J. Neurosci. 16, 5967–5978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pohle W., Acosta L., Rüthrich H., Krug M., Matthies H. (1987) Incorporation of [3H]fucose in rat hippocampal structures after conditioning by perforant path stimulation and after LTP-producing tetanization. Brain Res. 410, 245–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matthies H., Staak S., Krug M. (1996) Fucose and fucosyllactose enhance in-vitro hippocampal long-term potentiation. Brain Res. 725, 276–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Krug M., Wagner M., Staak S., Smalla K. H. (1994) Fucose and fucose-containing sugar epitopes enhance hippocampal long-term potentiation in the freely moving rat. Brain Res. 643, 130–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tiunova A. A., Anokhin K. V., Rose S. P. (1998) Two critical periods of protein and glycoprotein synthesis in memory consolidation for visual categorization learning in chicks. Learn. Mem. 4, 401–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rose S. P., Jork R. (1987) Long-term memory formation in chicks is blocked by 2-deoxygalactose, a fucose analog. Behav. Neural Biol. 48, 246–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lorenzini C. G., Baldi E., Bucherelli C., Sacchetti B., Tassoni G. (1997) 2-Deoxy-d-galactose effects on passive avoidance memorization in the rat. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 68, 317–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krug M., Jork R., Reymann K., Wagner M., Matthies H. (1991) The amnesic substance 2-deoxy-d-galactose suppresses the maintenance of hippocampal LTP. Brain Res. 540, 237–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Murrey H. E., Gama C. I., Kalovidouris S. A., Luo W. I., Driggers E. M., Porton B., Hsieh-Wilson L. C. (2006) Protein fucosylation regulates synapsin Ia/Ib expression and neuronal morphology in primary hippocampal neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 21–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brewer G. J., Torricelli J. R., Evege E. K., Price P. J. (1993) Optimized survival of hippocampal neurons in B27-supplemented Neurobasal, a new serum-free medium combination. J. Neurosci. Res. 35, 567–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Badawy R. A., Harvey A. S., Macdonell R. A. (2009) Cortical hyperexcitability and epileptogenesis: understanding the mechanisms of epilepsy – Part 1. J. Clin. Neurosci. 16, 355–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bordji K., Becerril-Ortega J., Buisson A. (2011) Synapses, NMDA receptor activity and neuronal Aβ production in Alzheimer's disease. Rev. Neurosci. 22, 285–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bowie D. (2008) Ionotropic glutamate receptors & CNS disorders. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets. 7, 129–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sanchez P. E., Zhu L., Verret L., Vossel K. A., Orr A. G., Cirrito J. R., Devidze N., Ho K., Yu G. Q., Palop J. J., Mucke L. (2012) Levetiracetam suppresses neuronal network dysfunction and reverses synaptic and cognitive deficits in an Alzheimer's disease model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, E2895–E2903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]