Background: NADPH-dependent α-keto acid reductase, belonging to the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase family, is involved in bacterial alginate metabolism.

Results: A novel NADH-dependent α-keto acid reductase was identified, and its tertiary structure was determined by x-ray crystallography.

Conclusion: Two short and long loops are structural determinants for coenzyme specificity.

Significance: A method for structure-based conversion of a coenzyme requirement was established.

Keywords: Alginate Lyase, Bacterial Metabolism, Enzyme Kinetics, Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (NADH), Reductase, Site-directed Mutagenesis, X-ray Crystallography

Abstract

The alginate-assimilating bacterium, Sphingomonas sp. strain A1, degrades the polysaccharides to monosaccharides through four alginate lyase reactions. The resultant monosaccharide, which is nonenzymatically converted to 4-deoxy-l-erythro-5-hexoseulose uronate (DEH), is further metabolized to 2-keto-3-deoxy-d-gluconate by NADPH-dependent reductase A1-R in the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) family. A1-R-deficient cells produced another DEH reductase, designated A1-R′, with a preference for NADH. Here, we show the identification of a novel NADH-dependent DEH reductase A1-R′ in strain A1, structural determination of A1-R′ by x-ray crystallography, and structure-based conversion of a coenzyme requirement in SDR enzymes, A1-R and A1-R′. A1-R′ was purified from strain A1 cells and enzymatically characterized. Except for the coenzyme requirement, there was no significant difference in enzyme characteristics between A1-R and A1-R′. Crystal structures of A1-R′ and A1-R′·NAD+ complex were determined at 1.8 and 2.7 Å resolutions, respectively. Because of a 64% sequence identity, overall structures of A1-R′ and A1-R were similar, although a difference in the coenzyme-binding site (particularly the nucleoside ribose 2′ region) was observed. Distinct from A1-R, A1-R′ included a negatively charged, shallower binding site. These differences were caused by amino acid residues on the two loops around the site. The A1-R′ mutant with the two A1-R-typed loops maintained potent enzyme activity with specificity for NADPH rather than NADH, demonstrating that the two loops determine the coenzyme requirement, and loop exchange is a promising method for conversion of coenzyme requirement in the SDR family.

Introduction

Coenzymes NADH and NADPH are electron mediators and are involved in oxidation/reduction enzymatic reactions, although their physiological roles are different in biological reactions (1). NADH, mainly used in catabolism, accepts electrons from nutrients and plays important roles in the production of bioenergy in the form of ATP. However, NADPH is involved in assimilation or antioxidation by its reducing power. In general, an oxidation/reduction-catalytic enzyme shows specificity for either coenzyme based on their biological roles.

Recently, biofuel production from unused and/or excess biomass has been an area of interest (2). To achieve bioproduction, metabolic pathways are modified through introduction and/or disruption of certain genes. This biotechnology, called synthetic biology, is now being developed in academia and industry (3). However, oxidation/reduction reactions are strictly regulated in innate organisms, with coenzyme balance properly maintained. In the case of microbial production of useful substances, intracellular oxidation/reduction imbalance of coenzymes occurs because of the artificial improvement and/or addition of metabolic reactions. The imbalance often causes low yield production. Two attempts have been conducted to solve this problem. One is to regenerate each coenzyme by coupling reactions using dehydrogenases of formate or glucose (4), and the other is to convert the coenzyme requirement of metabolic enzymes such as xylose reductase (5). The latter method is suitable for continuous production because addition of substrates such as formate/glucose and introduction of coenzyme-regenerating enzymes are unnecessary.

A lot of studies have been carried out to convert the coenzyme requirement. However, in many cases, resulting mutants show low enzyme activity compared with the wild-type (WT) enzyme (6–27). There are some successful cases (28–36), although general methods for conversion of the coenzyme requirement are being sought.

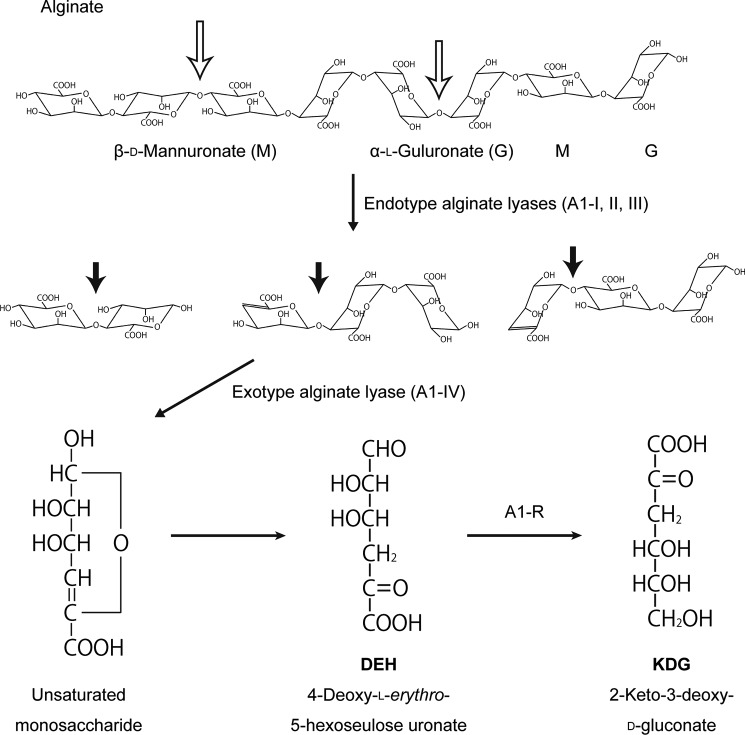

Alginate is a heteropolysaccharide consisting of two uronates β-d-mannuronate and α-l-guluronate (37). The polysaccharide is abundant as a major component of the cell wall matrix in marine algae, such as brown seaweeds. Currently, effective utilization of marine biomass alginate is desirable because brown seaweeds are readily cultivated and cause no serious competing interests for food-stuffs (38). The Gram-negative bacterium, Sphingomonas sp. strain A1, directly uptakes alginate into the cytoplasm through a superchannel consisting of a cell-surface pit and ATP-binding cassette transporter (39, 40). Alginate is degraded to monosaccharides by the action of cytoplasmic endotype alginate lyases A1-I, -II, and -III and exotype lyase A1-IV (41, 42). All of the resultant monosaccharides are nonenzymatically converted to 4-deoxy-l-erythro-5-hexoseulose uronate (DEH).3 DEH is reduced to 2-keto-3-deoxy-d-gluconate by NADPH-dependent reductase, A1-R (ID: SPH3227), and 2-keto-3-deoxy-d-gluconate is catabolized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate and pyruvate through subsequent reactions by 2-keto-3-deoxy-d-gluconate kinase and aldolase, respectively (Fig. 1) (43).

FIGURE 1.

Alginate metabolic pathway in strain A1. Degradation and metabolism of alginate by strain A1 enzymes are shown. Open and closed arrows indicate the cleavage sites of endo- and exotype alginate lyases, respectively.

Cells of recombinant strain A1, which harbor genes coding for ethanol fermentation, produce bioethanol from alginate (44). Ethanologenic bacteria or yeast that have been modified by the addition of multiple genes involved in alginate import and assimilation have been reported to convert sugars from brown macroalgae to bioethanol (45, 46). To optimize the alginate metabolism for biofuel production, an NADH-dependent DEH reductase is also valuable, and two desirable enzymes have been found in Vibrio species (45, 46). However, the characteristics of these enzymes remain to be clarified.

A1-R belongs to the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) family. SDR family enzymes use NADPH or NADH as a cofactor to metabolize sugars, fatty acids, and steroids (47). From bacteria to humans, a large number of organisms produce SDR family enzymes. More than 120,000 enzymes in the SDR family are registered in UniProtKB, although crystal structures thus far analyzed are mutually similar (48). Structural determinants for the coenzyme requirement in DEH reductases are valuable to establish a basic biotechnology regarding molecular conversion of coenzyme specificity in SDR family enzymes. Increasingly larger amounts of structural data regarding enzymes and proteins are being deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), in proportion to the progress in the field of structural biology. Structure-based biotechnology is expected to become an important part of post-structural biology. For example, the structure-based conversions of polysaccharide-degrading enzymes from the exo to the endo mode of action have been achieved (49, 50).

This study deals with molecular identification of a novel NADH-dependent DEH reductase (A1-R′) as a member of the SDR family, structural determination of A1-R′ and its complex with NAD+, and the structure-based conversion of its coenzyme requirement.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Sodium alginate (viscosity of 1% (w/v) solution; 1000 cps) and hydroxylapatite were purchased from Nacalai Tesque. TOYOPEARL DEAE-650 M and TOYOPEARL Butyl-650 M were from Tosoh. HiLoad 26/10 Q-Sepharose HP, HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 pg, HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 pg, and Mono Q HR 5/5 were from GE Healthcare. Restriction endonucleases and PCR-related enzymes were from Toyobo. Amicon Ultra-4 centrifugal filters were from Millipore. Bio-Gel P-2 was from Bio-Rad. Other analytical grade chemicals were obtained from commercial sources.

Microorganisms and Culture Conditions

Strain A1 cells were routinely cultured at 30 °C in minimal medium containing 0.5% (w/v) sodium alginate, 0.1% (w/v) (NH4)2SO4, 0.1% (w/v) KH2PO4, 0.1% (w/v) Na2HPO4, 0.01% (w/v) yeast extract, and 0.01% (w/v) MgSO4·7H2O. As a host for plasmid amplification, Escherichia coli strain DH5α (Toyobo) was routinely cultured aerobically at 37 °C in LB medium (1% (w/v) tryptone, 0.5% (w/v) yeast extract, and 1% (w/v) NaCl) (pH 7.2) containing appropriate antibiotics.

Enzyme and Protein Assays

The DEH reducing activity was assayed at 30 °C in a standard reaction mixture (0.5 ml) consisting of 4 mm DEH, 0.2 mm coenzyme (NADH or NADPH), 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer (KPB) (pH 7.0), and appropriate amount of enzyme.

The activity was measured by continuously monitoring the decrease of absorbance at 340 nm, which corresponds to the oxidation of NADH or NADPH. One unit of enzymatic activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to oxidize 1 μmol of coenzyme per min at 30 °C. The protein content was determined according to the Bradford procedure (51), with bovine serum albumin as the standard. The kinetic parameters (kcat and Km) for coenzyme or DEH were determined with data from enzyme assays conducted with various concentrations of coenzyme or DEH using the Michaelis-Menten equation with the KaleidaGraph program (Synergy Software).

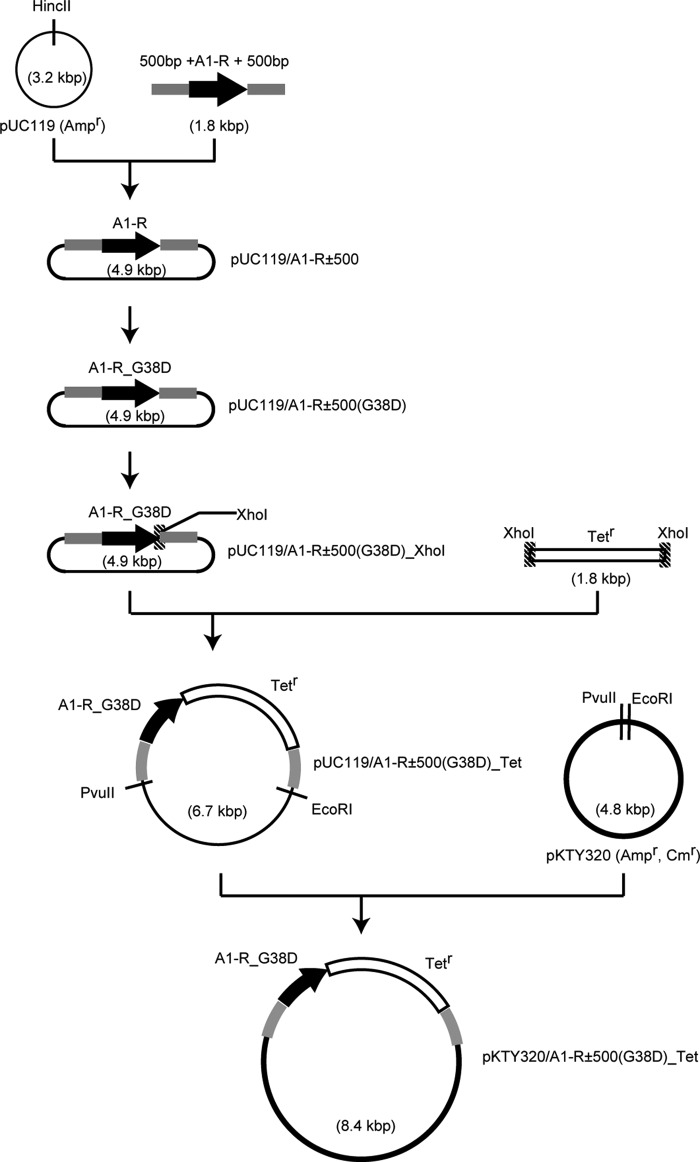

Construction of A1-R-deficient Strain A1

The strain A1 mutant with a deficiency in A1-R was generated through homologous recombination. Several plasmids were constructed to modify the strain A1 genome (Fig. 2). To amplify A1-R gene with upstream and downstream 500-bp regions, PCR was performed using A1-R±500 primers. Each primer used in this study is listed in Table 1. A reaction mixture (50 μl) contains 1 unit of KOD-FX (Toyobo), 50 ng of strain A1 genomic DNA, 15 pmol each of primers, 20 nmol of dNTPs, and KOD-FX buffer (Toyobo). The PCR conditions were as follows: 94 °C for 2 min and then 20 cycles at 98 °C for 10 s, 66 °C for 30 s, and 68 °C for 2 min. The resultant DNA fragments were ligated with HincII-digested pUC119 (Takara Bio). The resultant plasmid was designed as pUC119/A1-R±500. To mutate Gly-38 to Asp in pUC119/A1-R±500, A1-R_G38D primers were used, and the resultant plasmid was designated pUC119/A1-R±500(G38D). Inverse PCR was performed with A1-R_XhoI primers to insert an XhoI recognition site after the stop codon of the A1-R gene. The resultant plasmid after phosphorylation and self-ligation was designated as pUC119/A1-R±500(G38D)_XhoI. The tetracycline resistance gene cassette from pACYC184 (NIPPON GENE) was inserted into the XhoI site of pUC119/A1-R±500(G38D)_XhoI, and the resultant plasmid was designated pUC119/A1-R±500(G38D)_Tet. The plasmid was digested with PvuII and EcoRI, and the resultant fragment, including the A1-R gene, was inserted into PvuII- and EcoRI-digested pKTY320 (52). The resulting plasmid was designated pKTY320/A1-R±500(G38D)_Tet. DH5α cells transformed with pKTY320/A1-R±500(G38D)_Tet were used as a donor. E. coli strain HB101 cells transformed with pRK2013 were used as a helper. To obtain an A1-R-deficient strain A1 mutant, triparental mating (53) was performed using three types of strain A1, donor, and helper. Strain A1 cells were cultured in 0.5% (w/v) alginate minimal medium. Donor cells were cultured in LB medium containing 100 μg ml−1 sodium ampicillin and 20 μg ml−1 tetracycline hydrochloride. Helper cells were cultured in LB medium containing 20 μg ml−1 kanamycin sulfate. Each of the bacterial cells was cultured to an exponential growth phase until turbidity at 600 nm reached 0.5–1.0. When turbidity was 1.0, the cell concentration in the culture was regarded as 1.0 × 109 cells ml−1. Bacterial cells were collected and concentrations adjusted to 2 × 108 strain A1 cells, 1 × 108 donor cells, and 0.4 × 108 helper cells. All cells were collected at 25 °C by centrifugation at 2500 × g for 5 min and washed with 500 μl of 10 mm MgCl2. After centrifugation, bacterial cells were resuspended in 50 μl of 10 mm MgCl2 and spotted onto a 0.2-μm pore size membrane filter placed on a 0.5% (w/v) alginate medium plate containing 0.5% (w/v) yeast extract. After incubating overnight at 30 °C, bacterial cells on the filter were resuspended in 70 μl of 10 mm MgCl2. The cell suspension was spread on a 0.5% (w/v) alginate minimal medium plate containing 20 μg ml−1 tetracycline hydrochloride. After incubation at 30 °C for 4 days, single colonies were subjected to streak culture on a fresh alginate minimal medium plate containing tetracycline hydrochloride. As a result, ampicillin-sensitive and tetracycline-resistant cells were obtained. The nucleotide sequence of mutated and inserted regions in the strain A1 mutant genome was confirmed by dideoxy chain termination (54) using an automated DNA sequencer (Model 3730xl; Applied Biosystems). In the strain A1 mutant genome, the A1-R gene was substituted for the A1-R_G38D gene together with a tetracycline resistance gene.

FIGURE 2.

Construction scheme of plasmids for strain A1 mutant with a deficiency in A1-R. Black circle, plasmid; black bold arrow, A1-R gene; gray box, upstream and downstream 500 bp of the A1-R gene; shaded box, XhoI recognition site; open box, tetracycline resistance gene cassette.

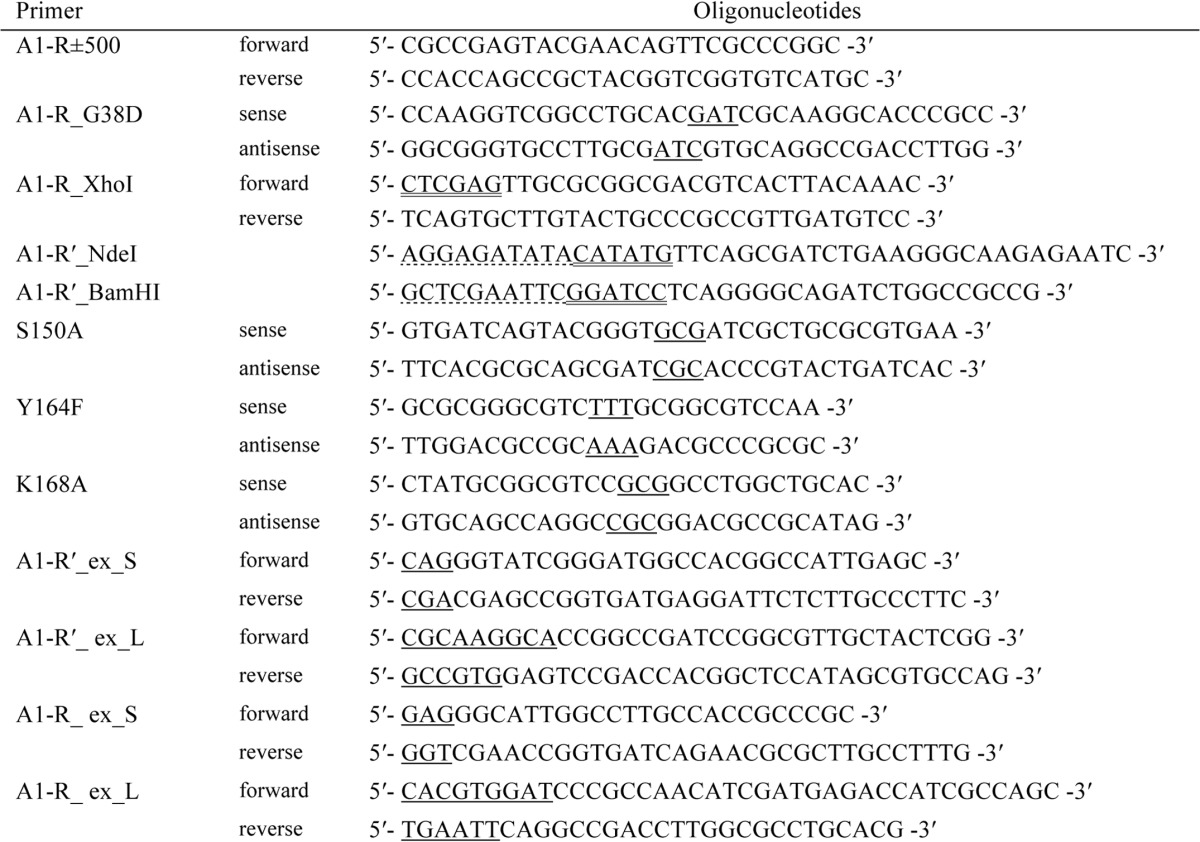

TABLE 1.

Primers for cloning and site-directed mutagenesis

Dotted, solid, and double underlines show identical sequence used in In-Fusion reaction, mutation site, and restriction site, respectively.

Purification of Novel DEH Reductase from Strain A1

A novel DEH reductase A1-R′ was purified from strain A1 cells as follows. Unless otherwise specified, all procedures were performed at 4 °C. Strain A1 cells were aerobically cultured in 6 liters of 0.5% (w/v) alginate minimal medium (1.5 liters per flask) at 30 °C for 48 h, collected by centrifugation at 6000 × g for 5 min, and resuspended in 40 ml of 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). Cells were ultrasonically disrupted (Insonator Model 201 M; Kubota) at 9 kHz for 20 min, and the clear solution obtained after centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 20 min was dialyzed against 1.5 liters of 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) twice and used as the cell extract. The cell extract was applied to a TOYOPEARL DEAE-650 M column (6 × 10 cm) previously equilibrated with 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). After washing with 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), the absorbed proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of NaCl (0–500 mm) in 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5, 600 ml), with a 10-ml fraction collected every 10 min. DEH reducing activity was assayed in the presence of NADH or NADPH for all fractions. Fractions including DEH-reducing activities in the presence of NADH are called active fractions hereafter. The active fractions, eluted with 200–300 mm NaCl, were dialyzed against 1.5 liters of 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) twice. The resultant dialysate was saturated with 30% (NH4)2SO4 and applied to a TOYOPEARL Butyl-650 M column (3 × 20 cm) previously equilibrated with 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 30% saturated (NH4)2SO4. After washing with 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 30% saturated (NH4)2SO4, the absorbed proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of saturated (NH4)2SO4 (30–0%, 200 ml), with a 6-ml fraction collected every 6 min. The active fractions, eluted with 10–0% saturated (NH4)2SO4, were combined and dialyzed against 1.5 liters of 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) twice. The dialysate was concentrated to 0.63 ml at a concentration of 20-mg of protein ml−1 and applied to a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 pg column (1.6 × 60 cm) previously equilibrated with 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 0.15 m NaCl. Proteins were eluted with the same buffer (120 ml) with a 2-ml fraction collected every 2 min. The active fractions were combined and dialyzed against 1.5 liters of 20 mm KPB (pH 7.0) twice. The dialysate was applied to a hydroxylapatite column (1 × 3 cm) previously equilibrated with 20 mm KPB (pH 7.0). After washing with 20 mm KPB (pH 7.0), the absorbed proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of KPB (20–200 mm, 10 ml), with a 0.5-ml fraction collected every minute. The active fractions obtained on elution with 50–100 mm KPB were dialyzed against 1.5 liters of 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) twice. The dialysate was applied to a Mono Q HR 5/5 column (0.5 × 5 cm) previously equilibrated with 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). After washing with 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), the absorbed proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of NaCl (0–500 mm, 5 ml) in 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), with a 0.5-ml fraction collected every minute. The active fractions, obtained on elution with 10–100 mm NaCl, were combined and applied to a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 pg column (1.6 × 60 cm) previously equilibrated with 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) containing 0.15 m NaCl. Proteins were eluted with the same buffer (120 ml), with a 2-ml fraction collected every 2 min, and the active fractions were combined and dialyzed against 1.5 liters of 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) twice. The dialysate was applied to a HiLoad 26/10 Q-Sepharose HP column (2.6 × 10 cm) previously equilibrated with 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). After washing with 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), the absorbed proteins were eluted with a linear gradient of NaCl (0–500 mm, 200 ml) in 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), with a 3-ml fraction collected every minute. The active fractions, eluted with 200–250 mm NaCl, were combined and confirmed as homogeneous by SDS-PAGE. The purified proteins were dialyzed against 1.5 liters of 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) twice and used as the native A1-R′ (nA1-R′).

Overexpression of A1-R′

The overexpression system for A1-R′ was constructed in E. coli cells as follows. To clone the A1-R′ gene, PCR was performed in a reaction mixture (50 μl) containing 1 unit of KOD-Plus-Neo (Toyobo), 50 ng of strain A1 genomic DNA, 15 pmol each of forward and reverse primers, 10 nmol of dNTPs, 75 nmol of MgCl2, and KOD-Plus-Neo buffer (Toyobo). The 5′ end of the forward primer (A1-R′_NdeI) contains 15 bases homologous to 15 bases of pET21b (Novagen) from the NdeI site toward the opposite direction to the BamHI site. In addition, the reverse primer (A1-R′_BamHI) possesses the same 15 bases of pET21b from the BamHI site toward the opposite direction to the NdeI site. PCR conditions were as follows: 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 30 cycles at 98 °C for 10 s, 63 °C for 30 s, and 68 °C for 1 min. The resultant fragment was ligated with NdeI- and BamHI-digested pET21b using the In-Fusion HD cloning Kit (Clontech). The resulting plasmid, designated as pET21b/A1-R′, includes the complete sequence of the A1-R′ gene with the original start and stop codons. E. coli strain BL21(DE3) (Novagen) was transformed with pET21b/A1-R′ and used for overexpression of A1-R′.

Purification of Recombinant A1-R′ from E. coli Cells

Unless otherwise specified, all procedures were performed at 4 °C. For expression, E. coli strain BL21(DE3) cells harboring pET21b/A1-R′ were aerobically cultured at 30 °C in 3 liters of LB medium (1.5 liters per flask), containing 100 μg ml−1 sodium ampicillin. When the turbidity at 600 nm reached 0.6, isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was added to the culture at a final concentration of 0.4 mm, and the cells were further cultured at 16 °C for 42 h. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 6000 × g for 5 min and resuspended in 30 ml of 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5). The cells were ultrasonically disrupted at 9 kHz for 20 min, and the clear solution obtained on centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 20 min was dialyzed against 1.5 liters of 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) twice. The dialysate was used as the cell extract. The recombinant A1-R′ (rA1-R′) was purified from the cell extract using four columns: TOYOPEARL DEAE-650 M, TOYOPEARL Butyl-650 M, HiLoad 26/10 Q-Sepharose HP, and HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 pg. Each column was operated in the same way as described above.

Site-directed Mutagenesis

To construct multiple amino acid-substituted mutants or to insert the XhoI site, the KOD-Plus mutagenesis kit (Toyobo) was used. Single amino acid-substituted mutants were constructed using a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The plasmid pET21b/A1-R′ was used as a template for A1-R′ mutants. The plasmid pET21b/A1-R (43) was used for A1-R mutants. Mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing as described above. Expression and purification of the mutants were performed in the same way as rA1-R′ from E. coli.

Crystallization and Structure Determination

The rA1-R′ solution was concentrated to 4.0 ml at a concentration of 31.1 mg of protein ml−1 and crystallized by sitting-drop vapor diffusion on a 96-well Intelli-plate (Veritas). Commercial screening kits (Hampton Research, Emerald BioSystems, and Jena Bioscience) were used to search for the crystallization conditions of rA1-R′. The reservoir solution volume was 70 μl in each well, and the droplet was prepared by mixing 1 μl of the protein solution with 1 μl of the reservoir solution. Crystals of rA1-R′ in complex with NAD+ (A1-R′·NAD+) were prepared in the solution containing NAD+ (Oriental Yeast). Each crystal of A1-R′ and A1-R′·NAD+ picked off the nylon loop was directly placed in a cold nitrogen gas stream at −173 °C. X-ray diffraction images of the crystals were collected at −173 °C under the nitrogen gas stream and synchrotron radiation of wavelength 1.0000 Å at the BL-38B1 station of SPring-8 (Hyogo, Japan). Diffraction data were processed, merged, and scaled using the HKL2000 program package (DENZO and SCALEPACK) (55). The structure of A1-R′ was determined by molecular replacement using coordinates of A1-R (PDB code 3AFM) as an initial model using the MOLREP program (56), in the CCP4 program package (57). Structure refinement was conducted using the Refmac5 program (58). Randomly selected 5% reflections were excluded from refinement and used to calculate Rfree. After each refinement cycle, the model was manually adjusted using the Coot program (59). Water molecules were incorporated where the difference in density exceeded 3.0σ in Fo − Fc map. Final model quality was checked using the PROCHECK program (60). Protein models were superimposed, and their root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) was determined using the LSQKAB program (61), which is a part of CCP4. Coordinates used in this work were obtained from the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics PDB. Figures of protein structures were prepared using the PyMOL program (62).

Analytical Methods

Polyacrylamide gel (12.5%) was used for SDS-PAGE. Proteins on the gel were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250. DEH was prepared from sodium alginate by using exotype alginate lyase, Atu3025 (63), and purified using Centriprep centrifugal filter and Bio-Gel P-2 size-exclusion column as described previously (43). Thiobarbituric acid method (64) was used for determination of DEH concentration. N-terminal amino acid sequence of the enzyme was determined by an Edman degradation method (65). To evaluate structural folding of the enzymes in 50 mm KPB (pH 7.0), circular dichroism (CD) spectra were measured in the far ultraviolet region (260–190 nm) using a J-720C spectropolarimeter (Jasco) at 25 °C. Samples were analyzed in a quartz cell with a path length of 0.1 mm. The content of helix and strand in the enzymes was estimated using the program CDPro. Structural folding in the enzymes was also investigated by measuring their thermal stabilities using differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) as described previously (66).

RESULTS

DEH Reducing Activity in A1-R-deficient Strain A1

To investigate the physiological significance of A1-R in strain A1, the strain A1 mutant (MT) with a deficiency in A1-R was constructed and characterized. The MT cells seem to produce A1-R_G38D instead of native A1-R. In A1-R_G38D, Gly-38 was replaced with Asp. In our previous paper (43), residue Gly-38 was found to be important for accommodating the phosphate group of NADPH due to its lack of side chain. In fact, the mutant (A1-R_G38D) with Gly-38 substituted with Asp exhibited a significantly reduced enzyme activity toward NADH (kcat, 8.29 s−1; Km, 181 μm) as well as NADPH (kcat, 5.16 s−1; Km, 178 μm). The specific activity of purified A1-R_G38D with 0.2 mm NADPH was drastically decreased to 1/24 (17.2 units mg−1) that of the native A1-R (406 units mg−1). This means that the strain A1 MT, which produces the A1-R_G38D mutant, shows negligible DEH reductase activity even in the presence of NADPH and NADH. MT cells showed little growth in 0.5% (w/v) alginate minimal medium containing 20 μg ml−1 tetracycline hydrochloride, although cell growth was observed after several acclimatizations. Specific DEH reducing activities in strain A1 wild-type and MT cell extracts were measured with 0.2 mm NADPH. The activity in the cell extract of MT corresponded to half as much as that of WT. The MT cell extract showed higher activity with 0.2 mm NADH than with NADPH. These results suggest the existence of another DEH reductase with a preference for NADH.

Identification of Another Novel DEH Reductase

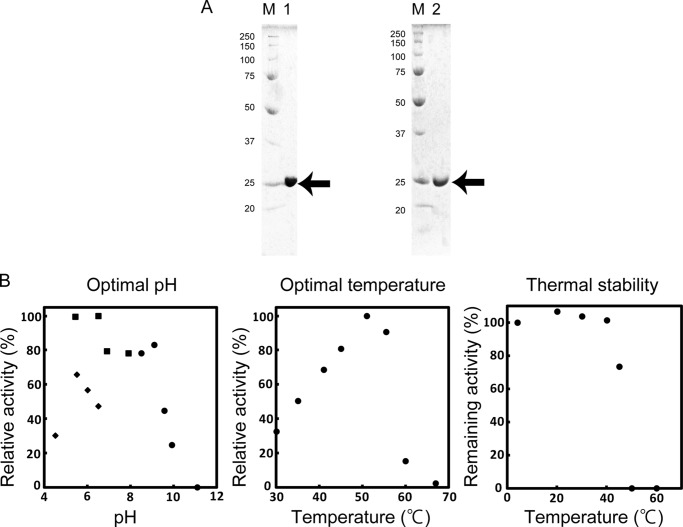

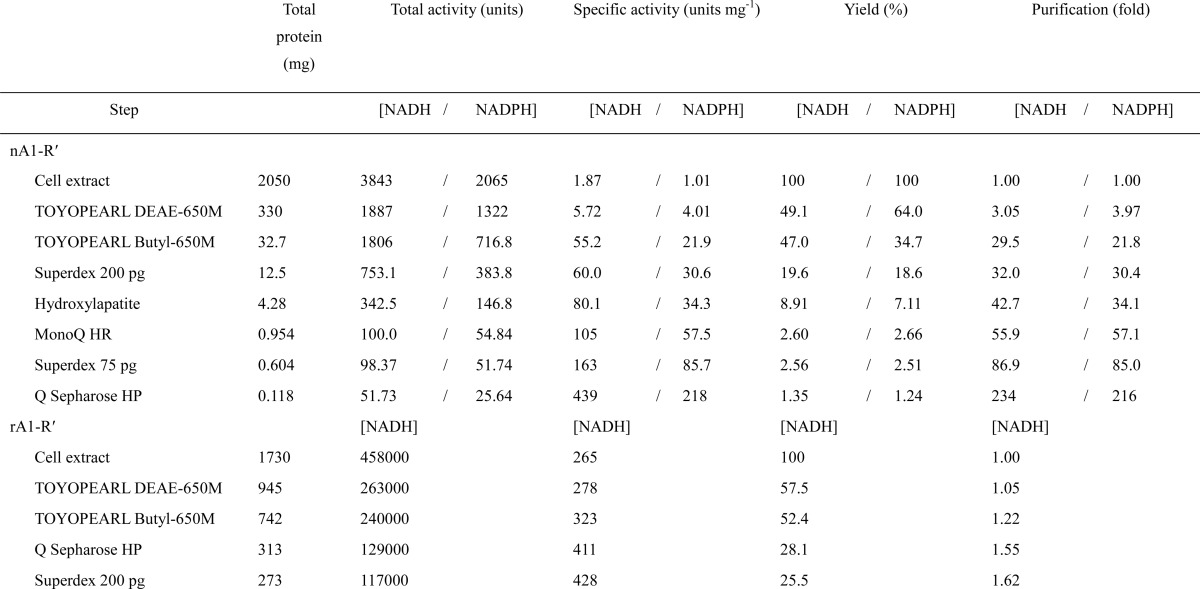

A novel DEH reductase, termed A1-R′, with a preference for NADH was purified 234-fold from strain A1 cells through seven steps of column chromatography with recovery of 1.35% (Table 2). The purified native A1-R′ (nA1-R′) was homogeneous by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3A, left panel). The N-terminal amino acid sequence of the purified enzyme was determined to be “NH2-Met-Phe-Ser-Asp-Leu.” In a genome database search of strain A1 (67), this protein was assigned ID SPH1210.

TABLE 2.

Purification of native and recombinant A1-R′ enzymes

FIGURE 3.

Properties of A1-R′. A, SDS-PAGE of purified A1-R′. Lane M, molecular weight standards; lane 1, purified nA1-R′ (5 μg); lane 2, purified rA1-R′ (5 μg). The arrow indicates the position of the enzyme. B, effects of pH and temperature on the activity and thermal stability of nA1-R′. Left panel, optimal pH. Activity was assayed with sodium acetate shown as diamond (pH 4.5, 5.5, 6.0, and 6.5), KPB shown as square (pH 5.4, 6.5, 6.9, and 7.9), and glycine-NaOH shown as circle (pH 8.5, 9.1, 9.6, 10, and 11). Sodium acetate appears to inhibit enzymatic activity compared with KPB. Activity at pH 6.5 in KPB was taken as 100%. Center panel, optimal temperature. Activity at 51 °C was taken as 100%. Right panel, thermal stability. nA1-R′ was preincubated for 5 min at various temperatures (as indicated), and the residual enzymatic activity was measured. The activity of the enzyme preincubated at 4 °C for 5 min was taken as 100%.

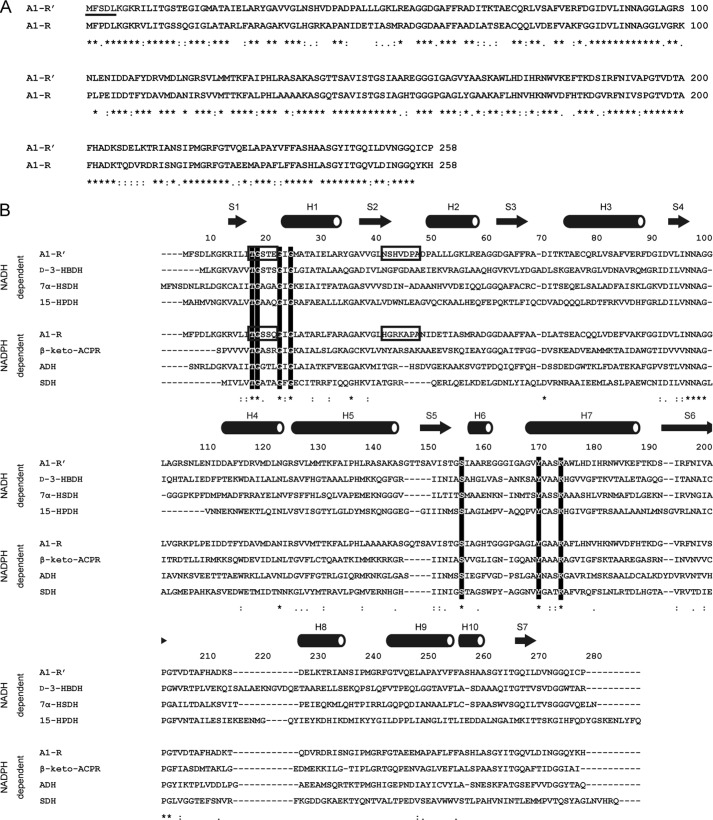

Based on the primary structure, the molecular weight of A1-R′ was calculated to be 27,337, with 258 amino acid residues. The sequence similarity between A1-R′ and A1-R was compared using ClustalW, and the resultant score was high, with 64% identity (Fig. 4A). BLAST search (blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) indicates that A1-R′ shows a high sequence identity (40–71%) with an SDR family enzyme, 3-ketoacyl-CoA reductase. A1-R′ includes a glycine-rich motif of the cofactor-binding Rossmann fold region (13TGXXXGXG20) and catalytic triad residues (Ser-150, Tyr-164, and Lys-168) conserved in the SDR family (Fig. 4B). These results demonstrate that A1-R′ belongs to the SDR family.

FIGURE 4.

Sequence alignment. A, alignment between A1-R′ and A1-R. N-terminally determined residues of A1-R′ are underlined. B, alignment of NADH and NADPH-dependent SDR family enzymes. Conserved residues among SDR family enzymes, TGXXXGXG motif and catalytic triad (Ser, Tyr, and Lys) are indicated by open letters. Asterisk, colon, and period indicate that residues are identical, highly similar, and moderately similar, respectively. Arrows and tubes over the alignment show β-strand and α-helix, respectively. Structural determinants (two loops) of the coenzyme requirement are boxed. Each enzyme is described as follows: d-3-HBDH, d-3-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase (PDB code 2ZTL) from Pseudomonas fragi; 7α-HSDH, 7-α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (PDB code 1AHI) from E. coli; 15-HPDH, 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (PDB code 2GDZ) from Homo sapiens; β-keto-ACPR, β-keto-acyl carrier protein reductase (PDB code 1EDO) from Brassica napus; ADH, alcohol dehydrogenase (PDB code 1NXQ) from Lactobacillus brevis; SDH, serine dehydrogenase (PDB code 3ASV) from E. coli.

Enzymatic Properties of A1-R′

Molecular Mass

The molecular mass of nA1-R′ was estimated to be 25 kDa via SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3A, left panel). Elution volume of nA1-R′ after HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 pg size exclusion chromatography showed that the molecular mass of nA1-R′ is ∼110 kDa (data not shown). These results indicated that nA1-R′ exists as a homotetramer.

Optimal pH, Optimal Temperature, and Thermal Stability

nA1-R′ was the most active at pH 6.5 (KPB) and 51 °C. The activity decreased by half after preincubation at 42 °C for 5 min (Fig. 3B).

Chemicals

The DEH reduction reaction was conducted at 30 °C in the presence or absence of different compounds, such as thiol reagents, the chelator EDTA, sugars, and metals. Almost all the chemicals tested had no significant effect (76–121%) on the reaction of nA1-R′ (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Effects of various compounds on the activity of nA1-R′

| Compounds | Concentration | Activitya |

|---|---|---|

| mm | % | |

| None | ||

| (NADPH) | 38b | |

| (NADH) | 100 | |

| Thiol reagents | ||

| Dithiothreitol | 1 | 97 |

| Glutathione (reduced form) | 1 | 107 |

| 2-Mercaptoethanol | 1 | 107 |

| Iodoacetic acid | 1 | 98 |

| p-Chloromercuribenzoic acid | 1 | 94 |

| Chelator | ||

| EDTA | 1 | 113 |

| Sugars | ||

| l-Fucose | 5 | 98 |

| d-Galactose | 5 | 98 |

| d-Glucose | 5 | 100 |

| d-Glucuronic acid | 5 | 103 |

| d-Mannose | 5 | 102 |

| l-Rhamnose | 5 | 100 |

| d-Xylose | 5 | 98 |

| d-Sucrose | 5 | 101 |

| d-Galacturonic acid | 5 | 103 |

| Metals | ||

| AlCl3 | 1 | 76 |

| MgCl2 | 1 | 115 |

| MnCl2 | 1 | 106 |

| CaCl2 | 1 | 121 |

| CoCl2 | 1 | 95 |

| ZnCl2 | 1 | 114 |

| HgCl2 | 0.01 | 83 |

| NaCl | 1 | 97 |

| KCl | 1 | 95 |

| LiCl | 1 | 102 |

a Relative activities (%) in a reaction mixture containing various compounds at the indicated concentrations are shown. The activity in the absence of the compound was taken as 100%.

b The value was determined when 0.2 mm NADH was replaced with 0.2 mm NADPH.

Kinetic Parameters

Kinetic parameters of nA1-R′ were determined based on the saturation curve of enzyme activities at various concentrations of substrates (Table 4). kcat and Km values were 227 s−1 and 4790 μm toward DEH, 280 s−1 and 15.5 μm toward NADH, and 233 s−1 and 224 μm toward NADPH. kcat scores toward NADH and NADPH were similar, although the affinity for NADH was 14.5-fold higher compared with that for NADPH. This indicates that A1-R′ shows a preference for NADH.

TABLE 4.

Kinetic parameters of nA1-R′ and rA1-R for DEH, NADH, and NADPH

| nA1-R′ |

rA1-R |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcat | Km | kcat Km−1 | kcat | Km | kcat Km−1 | |

| s−1 | μm | s−1 mm−1 | s−1 | μm | s−1 mm−1 | |

| DEH | 227 ± 16.2 | 4790 ± 630 | 47.4 | 197 ± 8.9 | 1930 ± 98 | 102a |

| NADH | 280 ± 10.2 | 15.5 ± 2.84 | 18100 | 25.3 ± 5.7 | 192 ± 75 | 132 |

| NADPH | 233 ± 44.6 | 224 ± 78 | 1040 | 220 ± 7.1 | 9.55 ± 1.4 | 23000 |

a The kinetic parameters of rA1-R for DEH are cited from Ref. 43.

rA1-R′ from E. coli

rA1-R′ was purified to 1.62-fold from recombinant E. coli cells through four steps of column chromatography (Table 2). rA1-R′ was homogeneous via SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3A, right panel). Kinetic parameters of rA1-R′ were comparable with those of nA1-R′.

Crystal Structure of A1-R′

A1-R′ and A1-R were very similar except for their coenzyme requirements, suggesting that local structural differences cause these variations. X-ray crystallography of A1-R′ was conducted to clarify structural determinants for the coenzyme requirement. An A1-R′ crystal was obtained in a droplet consisting of 20% (v/v) polyethylene glycol 400, 0.05 m sodium potassium phosphate (pH 6.2), 0.1 m NaCl, and 15.6 mg ml−1 rA1-R′. The crystal structure of A1-R′ was determined at a resolution of 1.80 Å by the molecular replacement method. After refinement, R- and Rfree-factors were 18.2 and 20.2%, respectively. Data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table 5. The refined model had two identical monomers in an asymmetric unit, termed molecules A and B. One phosphate molecule was bound to molecule A, and two phosphate molecules were bound to molecule B. Residues 1 and 199–212 of molecule A, and residues 1 and 197–213 of molecule B were unable to be assigned because the residues in this region of the electron density map are disordered. These residues are considered to form a long flexible loop. Structures of molecules A and B are basically identical because the r.m.s.d. between both was calculated as 0.232 Å. A1-R′ has 10 α-helices and seven β-strands and consists of a three-layered structure, α/β/α, with a coenzyme-binding site, called Rossmann fold (Figs. 4B, and 5, A and B) (68). The overall structure of A1-R′ mimics that of A1-R (Fig. 5, A and B). The torsion angle of the Thr-141 peptide bond was the outlier in the Ramachandran plot analysis. Thr-141 is on the loop consisting of only three residues between parallel α-helix H5 and β-strand S5. As a result, Thr-141 forms a hydrogen bond with Ser-139, and the loop is drastically bent.

TABLE 5.

Statistics for X-ray diffraction and structure refinement

| rA1-R′ | rA1-R′·NAD+ | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Space group | P3121 | P3121 |

| Unit cell parameters (Å, °) | a = b = 87.7, c = 139.6 | a = b = 87.9, c = 139.8 |

| Resolution limit (Å) | 50.0-1.80 (1.86-1.80)a | 50.0-2.67 (2.77-2.67)a |

| Total reflections | 682,105 | 219,436 |

| Unique reflections | 58,400 | 18,404 |

| Redundancy | 11.7 (11.4) | 11.9 (12.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (100) | 100 (99.9) |

| I/σ (I) | 47.3 (5.8) | 43.4 (9.0) |

| Rmerge (%) | 6.0 (38.4) | 7.4 (30.6) |

| Wilson B-factor (Å2) | 17.4 | 38.3 |

| Refinement | ||

| Final model | 486 residues, 3 PO43−, 294 water molecules | 483 residues, 81 water molecules, 5 SO42−, 1 NAD+ |

| Resolution limit (Å) | 33.4-1.80 (1.85-1.80) | 33.5-2.67 (2.73-2.67) |

| Used reflections | 55,375 (3971) | 17,397 (1227) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.8 (98.7) | 99.7 (99.4) |

| R-factor (%) | 18.2 (21.7) | 19.4 (26.5) |

| Rfree (%) | 20.2 (24.5) | 27.6 (35.5) |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | ||

| Protein | ||

| Molecule A | 23.5 | 47.5 |

| Molecule B | 24.8 | 52.2 |

| Waters | 33.6 | 38.5 |

| PO43− | ||

| Molecule C1 | 39.1 | |

| Molecule C2 | 65.3 | |

| Molecule C3 | 59.3 | |

| NAD+ | 61.3 | |

| SO42− | ||

| Molecule E1 | 24.2 | |

| Molecule E2 | 62.0 | |

| Molecule E3 | 78.5 | |

| Molecule E4 | 63.8 | |

| Molecule E5 | 83.4 | |

| r.m.s.d. | ||

| Bond (Å) | 0.0046 | 0.0099 |

| Angle (°) | 0.97 | 1.40 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | ||

| Favored regions | 96.6 | 95.8 |

| Allowed regions | 3.0 | 3.8 |

| Outliers | 0.4 | 0.4 |

a Data on highest shells are given in parentheses.

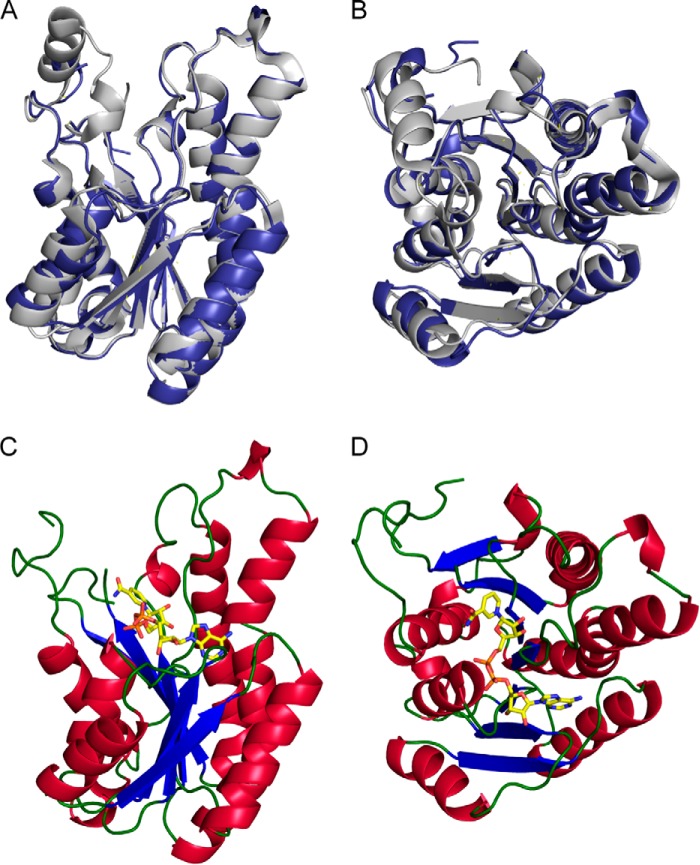

FIGURE 5.

Structures of A1-R′ and A1-R′·NAD+. A and B, overall structure of A1-R′ superimposed on A1-R based on the main chain. Blue, A1-R′; gray, A1-R. The structure of B is rotated 90° toward the reader relative to that of A. C and D, A1-R′·NAD+ complex structure. A1-R′ molecule is shown as a ribbon model, and each color indicates the following: blue, β-strand; red, α-helix, green, loop. NAD+ molecule is shown by a stick model, and each color indicates following: yellow, carbon atom; blue, nitrogen atom; orange, phosphorus atom; red, oxygen atom. The structure of D is rotated 90° toward the reader relative to that of C.

Catalytic Triad in A1-R′

Based on the sequence alignment (Fig. 4B), Ser-150, Tyr-164, and Lys-168 of A1-R′ are suggested to function as a catalytic triad. To confirm their roles as catalytic residues, three A1-R′ mutants (S150A, Y164F, and K168A, in which Ser-150, Tyr-164, and Lys-168 were replaced with Ala, Phe, and Ala, respectively) were constructed by site-directed mutagenesis. The mutants were purified in the same way as WT rA1-R′, and their kinetic parameters (kcat and Km) for DEH were determined as follows: WT, 201 s−1, and 5.68 mm; S150A, 0.00257 s−1, and 13.3 mm; Y164F, 0.000307 s−1, and 21.2 mm; and K168A, 0.373 s−1, and 5.07 mm. Compared with WT rA1-R′, all the mutants significantly decreased the enzymatic activity (kcat Km−1) (S150A, 0.00054%; Y164F, 0.000040%; and K168A, 0.21%). In particular, Y164F decreased the kcat value drastically to 0.00015%.

The arrangement of each residue of the catalytic triad (Ser-150, Tyr-164, and Lys-168) in the crystal structure of A1-R′ was identical to that of many SDR family enzymes, e.g. 3α,20β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (PDB code 2HSD). Because the involvement of the catalytic triad in the reactions catalyzed by SDR family enzymes has been well documented (47, 48, 69), the roles of Ser-150, Tyr-164, and Lys-168 in the A1-R′ reaction were postulated based on structural comparison with enzymes of the well characterized SDR family as follows: Ser-150 stabilizes the reaction intermediates; Tyr-164 acts as a catalytic base in the reduction reaction; and Lys-168 is crucial for the proper orientation of the coenzyme and lowering the pKa of Tyr-164.

Binding Mode to Coenzyme

To clarify the structural difference of the coenzyme-binding mode between A1-R′ and A1-R, the A1-R′·NAD+ complex crystal was obtained in the solution containing 0.85% (v/v) polyethylene glycol 400, 0.85 m (NH4)2SO4, 43 mm sodium Hepes (pH 7.5), 15.6 mg ml−1 rA1-R′, and 0.5 mm NAD+. The initial phase was determined by molecular replacement using coordinates of the ligand-free A1-R′ as a search model. After refinement, final structure was determined at 2.67 Å. Two monomers, termed molecules A and B, were present in an asymmetric unit. In molecule B, NAD+ bound to Rossmann fold (Fig. 5, C and D). In addition, four sulfate molecules were bound to molecule A, and one sulfate molecule was bound to molecule B. Residues 198–213 of molecule A and residues 197–213 of molecule B were unable to be assigned because the residues in this region of the electron density map are disordered. The r.m.s.d. value between molecules A and B of A1-R′·NAD+ was calculated as 0.314 Å, demonstrating that there is no significant conformational change between NAD+-free and -bound A1-R′.

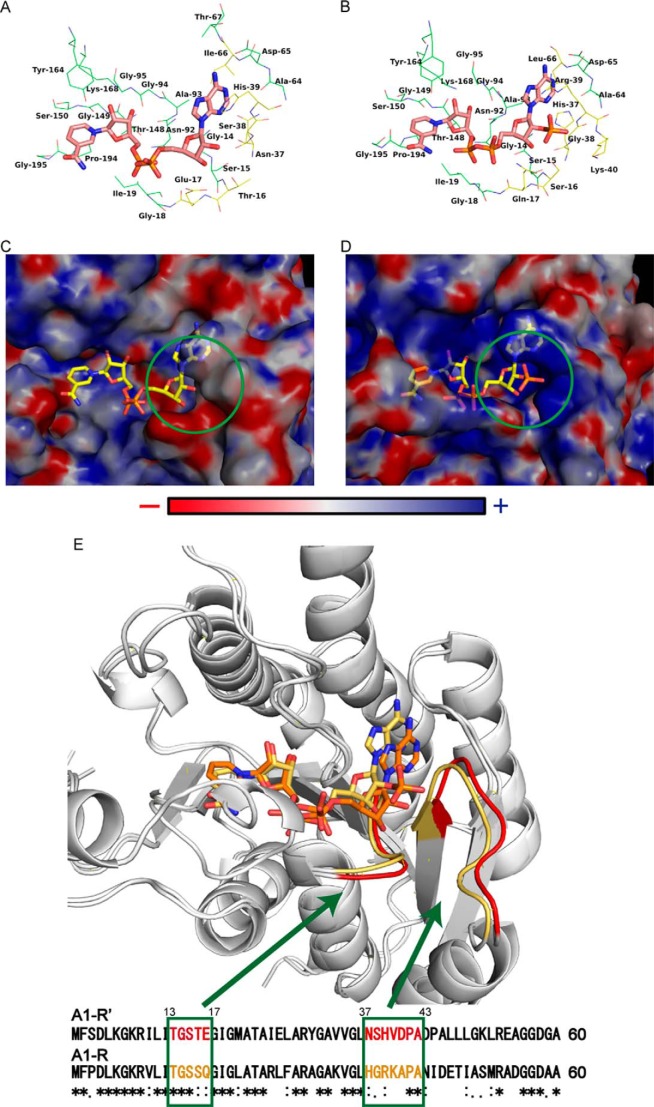

The coenzyme-binding site of A1-R′ was compared with that of A1-R (Fig. 6, A and B). In particular, the residues around the nucleoside ribose 2′ region of coenzyme bound were different between A1-R′ and A1-R, postulating that these are involved in coenzyme specificity. The electric charge of the molecular surface at pH 7.0 around the coenzyme-binding site of A1-R′ and A1-R is shown in Fig. 6, C and D. In A1-R′·NAD+, the A1-R′ site bound to the nucleoside ribose 2′ region of the coenzyme is negatively charged by the influence of Glu-17. However, the corresponding site in A1-R is positively charged by Arg-39 and Lys-40. Negative electric charge of Glu-17 may cause electrostatic repulsion to nucleoside ribose 2′ phosphate group of NADPH. Nevertheless, the positive charge of Arg-39 and Lys-40 is considered to cause electrostatic attraction. The space in A1-R′ is shallower compared with that in A1-R. The difficulty in binding of NADPH to A1-R′ is partly because of this smaller space at the nucleoside ribose 2′-binding site.

FIGURE 6.

Comparison between A1-R′ and A1-R. A, coenzyme-binding site in A1-R′·NAD+ complex structure. B, coenzyme-binding site in A1-R·NADP+ complex structure (PDB code 3AFN). Carbon atoms of NAD+ or NADP+ are colored pink. Residues within a distance of 4 Å from the coenzyme are shown. Blue, nitrogen atom; orange, phosphorus atom; red, oxygen atom. Carbon atoms of conserved and nonconserved residues between A1-R and A1-R′ are colored green and yellow, respectively. C, surface electrostatic potentials around NAD+ molecule in A1-R′·NAD+ complex structure. D, surface electrostatic potentials around NADP+ molecule in A1-R·NADP+ complex structure (PDB code 3AFN). Electric charges are calculated at pH 7.0. Blue and red indicate basic and acidic, respectively. Green circle shows the binding site around the nucleoside ribose 2′ region of the coenzyme. E, relationship between loops and primary structure. A1-R′ is superimposed on A1-R based on the main chain. Loops and primary structure of A1-R′ and A1-R are colored red and yellow, respectively.

Conversion of Coenzyme Requirement

The residues involved in electric charge and space formation at the binding site of the nucleoside ribose 2′ region of the coenzyme are on the two loops. In A1-R′, the short and long loops are composed of five residues (13TGSTE17) and seven residues (37NSHVDPA43), respectively (Fig. 6E). It was suggested that these two loops determine the coenzyme requirement because both A1-R′ and A1-R were very similar except for this requirement. To assess this hypothesis, A1-R′ and A1-R mutants were constructed, in which the loops were mutually exchanged. The terms “ex_S,” “ex_L,” and “ex_W” mean the mutants in which short loop, long loop, and both loops were exchanged, respectively.

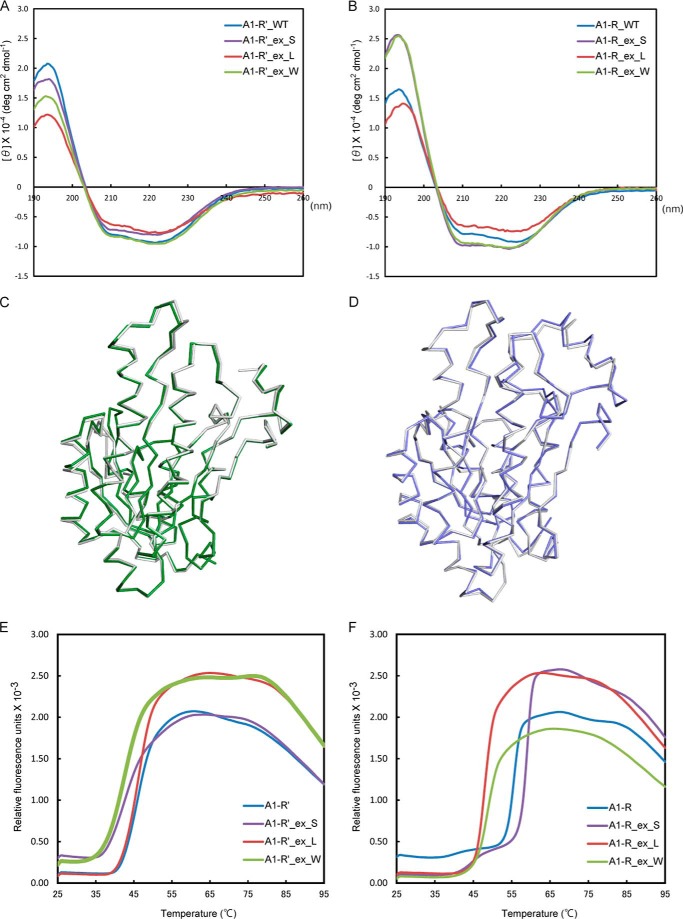

To validate the structural folding of the A1-R′ and A1-R mutants that have had their loop(s) exchanged, the purified mutants and the WT enzymes were subjected to CD spectroscopy (Fig. 7, A and B). The CD spectrum of each mutant was comparable with that of the corresponding WT enzyme. Subsequently, the secondary structural elements were determined by analyzing the CD profiles using the program CDPro. No significant differences in secondary structure were observed between the WT and mutant enzymes. This CD analysis suggested that all the mutants were properly folded, in manners similar to those of their respective WT enzymes, and that the enzymatic activity of the mutants was influenced by mutation, not misfolding.

FIGURE 7.

Structural validation of the WT and mutants of A1-R′ and A1-R. A, CD profiles of WT A1-R′ and its mutants at 1 mg ml−1. B, CD profiles of WT A1-R and its mutants at 1 mg ml−1. WT, ex_S, ex_L, and ex_W are colored blue, purple, red, and green, respectively, in A and B. C, superimposition of the main chains of A1-R′_ex_W (green) and WT A1-R′ (gray). D, superimposition of the main chains of A1-R_ex_W (blue) and WT A1-R (gray). E, fluorescence profiles of WT A1-R′ and its mutants used in the DSF analysis. F, fluorescence profiles of WT A1-R and its mutants used in the DSF analysis. WT, ex_S, ex_L, and ex_W are colored blue, purple, red, and green, respectively, in E and F.

Kinetic parameters of the mutants for NADH, NADPH, and DEH were determined (Table 6) after purification in the same way as rA1-R′. There were no significant differences between the Km values for DEH of the WT enzymes and those of the mutant enzymes as follows: WT A1-R′, 4.8 mm; A1-R′ mutants, 2.8–4.8 mm; WT A1-R, 1.9 mm; and A1-R mutants, 1.7–3.5 mm. These results suggest that the affinities of the mutants for the DEH substrate were comparable with those of their respective WT enzymes.

TABLE 6.

Kinetic parameters of the WT and mutants of A1-R′ and A1-R for NADH and NADPH

ND means not determined due to low activity.

| Enzyme | NADH |

NADPH |

NADH/NADPHa | DEH |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcat | Km | kcat Km−1 | kcat | Km | kcat Km−1 | kcat | Km | kcat Km−1 | ||

| s−1 | μm | s−1 mm−1 | s−1 | μm | mm−1 | s−1 | mm | s−1 mm−1 | ||

| A1-R′ Wild-type | 274 ± 4.8 | 24.3 ± 1.5 | 11300 | 233 ± 15 | 272 ± 30 | 857 | 13 | 227 ± 16.2 | 4.79 ± 0.63 | 47.4 |

| A1-R′_ex_S | 77.5 ± 4.7 | 20.4 ± 5.2 | 3800 | 109 ± 7.0 | 28.4 ± 6.9 | 3840 | 0.99 | 172 ± 2.65 | 3.32 ± 0.11 | 51.8 |

| A1-R′_ex_L | 33.6 ± 10 | 493 ± 220 | 68.2 | 110 ± 11 | 45.5 ± 15 | 2420 | 0.028 | 161 ± 6.31 | 2.77 ± 0.24 | 58.1 |

| A1-R′_ex_W | 134 ± 26 | 217 ± 78 | 618 | 149 ± 1.3 | 2.85 ± 0.31 | 52300 | 0.012 | 225 ± 6.65 | 4.45 ± 0.25 | 50.6 |

| A1-R Wild-type | 25.3 ± 5.7 | 192 ± 75 | 132 | 220 ± 7.1 | 9.55 ± 1.4 | 23000 | 0.0057 | 197 ± 8.9 | 1.93 ± 0.098 | 102 |

| A1-R_ex_S | 3.77 ± 0.47 | 623 ± 100 | 6.05 | 193 ± 18 | 512 ± 70 | 377 | 0.016 | 226 ± 6.02 | 3.54 ± 0.19 | 48.9 |

| A1-R_ex_L | 4.25 ± 2.0 | 321 ± 240 | 13.2 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 5.47 ± 0.186 | 1.66 ± 0.15 | 1.32 |

| A1-R_ex_W | 6.80 ± 3.5 | 2580 ± 1400 | 2.64 | 2.03 ± 3.0 | 5600 ± 8600 | 0.363 | 7.27 | 8.66 ± 0.257 | 3.04 ± 0.19 | 2.85 |

a The kcat Km−1 value toward NADH/the kcat Km−1 value toward NADPH.

Both A1-R′_ex_S and A1-R′_ex_L increased affinity with NADPH. A1-R′_ex_W synergistically increased affinity with NADPH, although these three A1-R′ mutants displayed a decreased kcat for NADPH compared with that for WT A1-R′. These results suggest that the two loops play a key role in affinity with NADPH. A1-R′_ex_W drastically increased the kcat Km−1 value for NADPH, whereas its kcat Km−1 value for NADH decreased, indicating that A1-R′_ex_W showed an 85-fold preference for NADPH, compared with NADH. Moreover, kinetic parameters of A1-R′_ex_W for NADPH were comparable with those of A1-R for NADPH. In contrast to conversion in dependence from NADH to NADPH, three A1-R mutants exhibited decreased activity for NADH compared with that for WT A1-R.

DISCUSSION

A novel NADH-dependent DEH reductase, A1-R′, was identified in strain A1. To date, two NADH-dependent DEH reductases from Vibrios have been reported (45, 46), although their enzyme properties and structures remain to be clarified. This is the first report on structure/function relationships of NADH-dependent DEH reductase and complete conversion of the coenzyme requirement in the enzyme.

Previously, Tomita et al. (31) succeeded in converting the coenzyme requirement in the non-SDR family enzyme, malate dehydrogenase (MDH), by multiple site-directed mutagenesis. Exchange of one of the MDH loops corresponding to the A1-R′ loops also contributes to conversion of the coenzyme requirement, although the loop mutant exhibited a reduced enzyme activity (kcat Km−1) compared with the WT enzyme. Recently, Brinkmann-Chen et al. (36) established a method for conversion of the coenzyme requirement in the non-SDR family enzymes, ketol-acid reductoisomerase family enzymes, through mutation of some residues in a loop and succeeding random mutations.

Conversion of the coenzyme requirement in A1-R′ was achieved by exchange of two loops close to the coenzyme-binding site. The A1-R′ mutant with A1-R-typed loops showed a high kcat score and low Km value for NADPH, corresponding to those of A1-R for NADPH. From these results, it was revealed that the nature of the two loops determines the coenzyme requirement. Because SDR family enzymes commonly have the two loops in the Rossmann fold, the exchange of the two loops is expected to be a potential method to convert the coenzyme requirement of other SDR enzymes. The SDR family includes several metabolic enzymes, and thus the regulation of the coenzyme requirement will enable maintenance of the cellular oxidation/reduction balance. Well balanced coenzyme concentration can lead to high efficiency and continuous production of useful chemicals.

It is of interest that NADPH-dependent A1-R′_ex_W showed high activity, whereas NADH-dependent A1-R_ex_W showed low activity (Table 6). Therefore, the tertiary and quaternary structures of A1-R′_ex_W and A1-R_ex_W were determined by x-ray crystallography, even though no significant difference in secondary structure was observed between the WT enzymes and their respective mutants by CD spectroscopy. The overall structures of A1-R′_ex_W and A1-R_ex_W superimposed well on those of WT A1-R′ and A1-R, respectively (Fig. 7, C and D), indicating that the structural folding of both mutants was identical to that of their respective WT enzymes. The significant decrease in enzymatic activity exhibited by A1-R_ex_W is probably due to the exchange of the two loops, not to misfolding. The A1-R′-type loop(s) were considered to be unsuitable for interaction with the basic scaffold of A1-R. In fact, the loop mutants A1-R_ex_W and A1-R_ex_L were found to be less thermally stable than WT A1-R through DSF analysis. The fluorescence of SYPRO Orange that bound to denatured proteins was measured during heat treatment (from 25 to 95 °C). The melting temperatures (Tm) of the WT and mutant enzymes were determined as the transition midpoint in the fluorescence profile. The fluorescence profiles of A1-R_ex_W (Tm, 49.2 °C) and A1-R_ex_L (Tm, 47.8 °C) were significantly shifted to a lower temperature, compared with that of WT A1-R (Tm, 55.6 °C) (Fig. 7F), suggesting that WT A1-R was thermally more stable than the mutants. However, the Tm (42.7 °C) of A1-R′_ex_W was slightly lower than that (Tm, 45.7 °C) of WT A1-R′ (Fig. 7E).

The question as to why strain A1 has two different DEH reductases will be the focus of future studies. DEH is demonstrated to be toxic to bacterial cells (70), suggesting that strain A1 cells are obliged to reduce DEH immediately to detoxify and metabolize alginate, although the intracellular NAD+/NADH ratio is influenced by the outer environment (i.e. oxygen concentration). To reduce DEH under any circumstance, strain A1 may have two types of reductases with different coenzyme requirements. In the case of a high level of NADH, strain A1 cells reduce DEH by A1-R′ and conserve NADPH for assimilation. As intracellular levels of NADH decrease, A1-R may reduce DEH using NADPH.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. S. Baba and N. Mizuno of the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute for their kind help in data collection. Diffraction data for crystals were collected at the BL-38B1 station of SPring-8 (Hyogo, Japan) with the approval (2011A1186, 2011B2055, 2012B1265, and 2013A1106) of Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute. We thank Drs. J. Ogawa and S. Kishino of the Division of Applied Life Sciences, Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University for N-terminal sequence determination. We also thank Dr. N. Takahashi of the Division of Applied Life Sciences, Graduate School of Agriculture, Kyoto University for analyzing the CD spectra.

This work was supported in part by grants-in-aid from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (to K. M. and W. H.), the Program for Promotion of Basic Research Activities for Innovative Biosciences of Japan (to K. M.), the Targeted Proteins Research Program (to W. H.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan, and research fellowships from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Young Scientists (to R. T.).

The nucleotide sequence(s) reported in this paper has been submitted to the DDBJ/GenBankTM/EBI Data Bank with accession number(s) AB970509.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 4TKL, 4TKM, 4W7I, and 4W7H) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- DEH

- 4-deoxy-l-erythro-5-hexoseulose uronate

- SDR

- short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- KPB

- potassium phosphate buffer

- DSF

- differential scanning fluorimetry

- MT

- mutant

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation.

REFERENCES

- 1. Moat A. G., Foster J. W. (1987) in Pyridine Nucleotide Coenzymes Part A (Avramovic D. D., Poulson R., eds) pp. 1–24, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vertès A. A., Qureshi N., Blaschek H. P., Yukawa H. (eds) (2010) Biomass to Biofuels: Strategies for Global Industries, pp. 1–22, John Wiley & Sons Ltd., Chichester, UK [Google Scholar]

- 3. Colin V. L., Rodriguez A., Cristobal H. A. (2011) The role of synthetic biology in the design of microbial cell factories for biofuel production. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 10.1155/2011/601834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kaup B., Bringer-Meyer S., Sahm H. (2004) Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli: construction of an efficient biocatalyst for d-mannitol formation in a whole-cell biotransformation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 64, 333–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Watanabe S., Saleh A. A., Pack S. P., Annaluru N., Kodaki T., Makino K. (2007) Ethanol production from xylose by recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae expressing protein engineered NADP+-dependent xylitol dehydrogenase. J. Biotechnol. 130, 316–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Galkin A., Kulakova L., Ohshima T., Esaki N., Soda K. (1997) Construction of a new leucine dehydrogenase with preferred specificity for NADP+ by site-directed mutagenesis of the strictly NAD+-specific enzyme. Protein Eng. 10, 687–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Petschacher B., Leitgeb S., Kavanagh K. L., Wilson D. K., Nidetzky B. (2005) The coenzyme specificity of Candida tenuis xylose reductase (AKR2B5) explored by site-directed mutagenesis and x-ray crystallography. Biochem. J. 385, 75–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clermont S., Corbier C., Mely Y., Gerard D., Wonacott A., Branlant G. (1993) Determinants of coenzyme specificity in glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase: role of the acidic residue in the fingerprint region of the nucleotide binding fold. Biochemistry 32, 10178–10184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Banta S., Swanson B. A., Wu S., Jarnagin A., Anderson S. (2002) Alteration of the specificity of the cofactor-binding pocket of Corynebacterium 2,5-diketo-d-gluconic acid reductase A. Protein Eng. 15, 131–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Holmberg N., Ryde U., Bülow L. (1999) Redesign of the coenzyme specificity in l-lactate dehydrogenase from Bacillus stearothermophilus using site-directed mutagenesis and media engineering. Protein Eng. 12, 851–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yaoi T., Miyazaki K., Oshima T., Komukai Y., Go M. (1996) Conversion of the coenzyme specificity of isocitrate dehydrogenase by module replacement. J. Biochem. 119, 1014–1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rane M. J., Calvo K. C. (1997) Reversal of the nucleotide specificity of ketol acid reductoisomerase by site-directed mutagenesis identifies the NADPH binding site. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 338, 83–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shiraishi N., Croy C., Kaur J., Campbell W. H. (1998) Engineering of pyridine nucleotide specificity of nitrate reductase: mutagenesis of recombinant cytochrome b reductase fragment of Neurospora crassa NADPH:nitrate reductase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 358, 104–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eppink M. H., Overkamp K. M., Schreuder H. A., Van Berkel W. J. (1999) Switch of coenzyme specificity of p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase. J. Mol. Biol. 292, 87–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Elmore C. L., Porter T. D. (2002) Modification of the nucleotide cofactor-binding site of cytochrome P-450 reductase to enhance turnover with NADH in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 48960–48964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kristan K., Stojan J., Adamski J., Lanisnik Rizner T. (2007) Rational design of novel mutants of fungal 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. J. Biotechnol. 129, 123–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dambe T. R., Kühn A. M., Brossette T., Giffhorn F., Scheidig A. J. (2006) Crystal structure of NADP(H)-dependent 1,5-anhydro-d-fructose reductase from Sinorhizobium morelense at 2.2 Å resolution: construction of a NADH-accepting mutant and its application in rare sugar synthesis. Biochemistry 45, 10030–10042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Medina M., Luquita A., Tejero J., Hermoso J., Mayoral T., Sanz-Aparicio J., Grever K., Gomez-Moreno C. (2001) Probing the determinants of coenzyme specificity in ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase by site-directed mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 11902–11912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen R., Greer A., Dean A. M. (1995) A highly active decarboxylating dehydrogenase with rationally inverted coenzyme specificity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 11666–11670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hoelsch K., Sührer I., Heusel M., Weuster-Botz D. (2013) Engineering of formate dehydrogenase: synergistic effect of mutations affecting cofactor specificity and chemical stability. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 97, 2473–2481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bernard N., Johnsen K., Holbrook J. J., Delcour J. (1995) D175 discriminates between NADH and NADPH in the coenzyme binding site of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. Bulgaricus d-lactate dehydrogenase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 208, 895–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Serov A. E., Popova A. S., Fedorchuk V. V., Tishkov V. I. (2002) Engineering of coenzyme specificity of formate dehydrogenase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. J. 367, 841–847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Capone M., Scanlon D., Griffin J., Engel P. C. (2011) Re-engineering the discrimination between the oxidized coenzymes NAD+ and NADP+ in clostridial glutamate dehydrogenase and a thorough reappraisal of the coenzyme specificity of the wild-type enzyme. FEBS J. 278, 2460–2468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Baroni S., Pandini V., Vanoni M. A., Aliverti A. (2012) A single tyrosine hydroxyl group almost entirely controls the NADPH specificity of Plasmodium falciparum ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase. Biochemistry 51, 3819–3826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lerchner A., Jarasch A., Meining W., Schiefner A., Skerra A. (2013) Crystallographic analysis and structure-guided engineering of NADPH-dependent Ralstonia sp. alcohol dehydrogenase toward NADH cosubstrate specificity. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 110, 2803–2814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Scrutton N. S., Berry A., Perham R. N. (1990) Redesign of the coenzyme specificity of a dehydrogenase by protein engineering. Nature 343, 38–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marohnic C. C., Bewley M. C., Barber M. J. (2003) Engineering and characterization of a NADPH-utilizing cytochrome b5 reductase. Biochemistry 42, 11170–11182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang L., Ahvazi B., Szittner R., Vrielink A., Meighen E. (1999) Change of nucleotide specificity and enhancement of catalytic efficiency in single point mutants of Vibrio harveyi aldehyde dehydrogenase. Biochemistry 38, 11440–11447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hsieh J. Y., Liu G. Y., Chang G. G., Hung H. C. (2006) Determinants of the dual cofactor specificity and substrate cooperativity of the human mitochondrial NAD(P)+-dependent malic enzyme: functional roles of glutamine 362. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 23237–23245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Miller S. P., Lunzer M., Dean A. M. (2006) Direct demonstration of an adaptive constraint. Science 314, 458–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tomita T., Fushinobu S., Kuzuyama T., Nishiyama M. (2006) Structural basis for the alteration of coenzyme specificity in a malate dehydrogenase mutant. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 347, 502–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Watanabe S., Kodaki T., Makino K. (2005) Complete reversal of coenzyme specificity of xylitol dehydrogenase and increase of thermostability by the introduction of structural zinc. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 10340–10349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ehrensberger A. H., Elling R. A., Wilson D. K. (2006) Structure-guided engineering of xylitol dehydrogenase cosubstrate specificity. Structure 14, 567–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen R., Greer A., Dean A. M. (1996) Redesigning secondary structure to invert coenzyme specificity in isopropylmalate dehydrogenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 12171–12176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zheng H., Bertwistle D., Sanders D. A., Palmer D. R. (2013) Converting NAD-specific inositol dehydrogenase to an efficient NADP-selective catalyst, with a surprising twist. Biochemistry 52, 5876–5883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brinkmann-Chen S., Flock T., Cahn J. K., Snow C. D., Brustad E. M., McIntosh J. A., Meinhold P., Zhang L., Arnold F. H. (2013) General approach to reversing ketol-acid reductoisomerase cofactor dependence from NADPH to NADH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 10946–10951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gacesa P. (1988) Alginates. Carbohydr. Polym. 8, 161–182 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stokstad E. (2012) Biofuels. Engineered superbugs boost hopes of turning seaweed into fuel. Science 335, 273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hisano T., Kimura N., Hashimoto W., Murata K. (1996) Pit structure on bacterial cell surface. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 220, 979–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Momma K., Okamoto M., Mishima Y., Mori S., Hashimoto W., Murata K. (2000) A novel bacterial ATP-binding cassette transporter system that allows uptake of macromolecules. J. Bacteriol. 182, 3998–4004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yoon H.-J., Hashimoto W., Miyake O., Okamoto M., Mikami B., Murata K. (2000) Overexpression in Escherichia coli, purification, and characterization of Sphingomonas sp. A1 alginate lyases. Protein Expr. Purif. 19, 84–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hashimoto W., Miyake O., Momma K., Kawai S., Murata K. (2000) Molecular identification of oligoalginate lyase of Sphingomonas sp. strain A1 as one of the enzymes required for complete depolymerization of alginate. J. Bacteriol. 182, 4572–4577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Takase R., Ochiai A., Mikami B., Hashimoto W., Murata K. (2010) Molecular identification of unsaturated uronate reductase prerequisite for alginate metabolism in Sphingomonas sp. A1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1804, 1925–1936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Takeda H., Yoneyama F., Kawai S., Hashimoto W., Murata K. (2011) Bioethanol production from marine biomass alginate by metabolically engineered bacteria. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 2575–2581 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wargacki A. J., Leonard E., Win M. N., Regitsky D. D., Santos C. N., Kim P. B., Cooper S. R., Raisner R. M., Herman A., Sivitz A. B., Lakshmanaswamy A., Kashiyama Y., Baker D., Yoshikuni Y. (2012) An engineered microbial platform for direct biofuel production from brown macroalgae. Science 335, 308–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Enquist-Newman M., Faust A. M., Bravo D. D., Santos C. N., Raisner R. M., Hanel A., Sarvabhowman P., Le C., Regitsky D. D., Cooper S. R., Peereboom L., Clark A., Martinez Y., Goldsmith J., Cho M. Y., Donohoue P. D., Luo L., Lamberson B., Tamrakar P., Kim E. J., Villari J. L., Gill A., Tripathi S. A., Karamchedu P., Paredes C. J., Rajgarhia V., Kotlar H. K., Bailey R. B., Miller D. J., Ohler N. L., Swimmer C., Yoshikuni Y. (2014) Efficient ethanol production from brown macroalgae sugars by a synthetic yeast platform. Nature 505, 239–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kavanagh K. L., Jörnvall H., Persson B., Oppermann U. (2008) Medium- and short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase gene and protein families: the SDR superfamily: functional and structural diversity within a family of metabolic and regulatory enzymes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 3895–3906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Persson B., Kallberg Y. (2013) Classification and nomenclature of the superfamily of short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases (SDRs). Chem. Biol. Interact. 202, 111–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Proctor M. R., Taylor E. J., Nurizzo D., Turkenburg J. P., Lloyd R. M., Vardakou M., Davies G. J., Gilbert H. J. (2005) Tailored catalysts for plant cell-wall degradation: redesigning the exo/endo preference of Cellvibrio japonicus arabinanase 43A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 2697–2702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ochiai A., Itoh T., Mikami B., Hashimoto W., Murata K. (2009) Structural determinants responsible for substrate recognition and mode of action in family 11 polysaccharide lyases. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 10181–10189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bradford M. M. (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kimbara K., Hashimoto T., Fukuda M., Koana T., Takagi M., Oishi M., Yano K. (1989) Cloning and sequencing of two tandem genes involved in degradation of 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl to benzoic acid in the polychlorinated biphenyl-degrading soil bacterium Pseudomonas sp. strain KKS102. J. Bacteriol. 171, 2740–2747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ruvkun G. B., Ausubel F. M. (1981) A general method for site-directed mutagenesis in prokaryotes. Nature 289, 85–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sanger F., Nicklen S., Coulson A. R. (1977) DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 74, 5463–5467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Processing of x-ray diffraction data. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vagin A., Teplyakov A. (2010) Molecular replacement with MOLREP. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 22–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Collaborative Computational Project No. 4 (1994) The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50, 760–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Laskowski R. A., MacArthur M. W., Moss D. S., Thornton J. M. (1993) PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kabsch W. (1978) A discussion of the solution for the best rotation to relate two sets of vectors. Acta Crystallogr. A 34, 827–828 [Google Scholar]

- 62. Delano W. L. (2002) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, DeLano Scientific LLC, San Carlos, CA [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ochiai A., Hashimoto W., Murata K. (2006) A biosystem for alginate metabolism in Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58: molecular identification of Atu3025 as an exotype family PL-15 alginate lyase. Res. Microbiol. 157, 642–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Nedjma M., Hoffmann N., Belarbi A. (2001) Selective and sensitive detection of pectin lyase activity using a colorimetric test: application to the screening of microorganisms possessing pectin lyase activity. Anal. Biochem. 291, 290–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Edman P. (1950) Method for determination of the amino acid sequence in peptides. Acta Chem. Scand. 4, 283–293 [Google Scholar]

- 66. Nishitani Y., Maruyama Y., Itoh T., Mikami B., Hashimoto W., Murata K. (2012) Recognition of heteropolysaccharide alginate by periplasmic solute-binding proteins of a bacterial ABC transporter. Biochemistry 51, 3622–3633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hashimoto W., Momma K., Maruyama Y., Yamasaki M., Mikami B., Murata K. (2005) Structure and function of bacterial super-biosystem responsible for import and depolymerization of macromolecules. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 69, 673–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Rossmann M. G., Moras D., Olsen K. W. (1974) Chemical and biological evolution of nucleotide-binding protein. Nature 250, 194–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hoffmann F., Maser E. (2007) Carbonyl reductases and pluripotent hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases of the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase superfamily. Drug Metab. Rev. 39, 87–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hashimoto W., Kawai S., Murata K. (2010) Bacterial supersystem for alginate import/metabolism and its environmental and bioenergy applications. Bioeng. Bugs 1, 97–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]