Abstract

We describe a case of renal papillary necrosis in a middle-aged female with sickle cell trait who presented with gross hematuria. We wish to highlight this case for several reasons. Sickle cell trait is often viewed as a benign condition despite the fact that it is associated with significant morbidity such as renal papillary necrosis and renal medullary carcinoma. Appropriate evaluation needs to be undertaken to promptly diagnose renal papillary necrosis and differentiate it from renal medullary carcinoma as this can result in deadly consequences for patients. CT urography has emerged as a diagnostic study to evaluate hematuria in such patients. We review the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of renal papillary necrosis in patients with sickle cell trait.

Keywords: Sickle cell trait, renal papillary necrosis, CT urography

A 42-year-old African American woman with a history of sickle cell trait (SCT) was admitted to the hospital for painless gross hematuria with the passage of clots for 3 weeks. She also complained of fatigue, dizziness, and general malaise. She denied abdominal pain, dysuria, or fever. She had a remote history of similar presentation 20 years ago that resulted in right-sided partial nephrectomy. It was performed in an outside hospital and medical records were not available. She reported no other significant medical history and was not taking any medications at home. Family and social history was unremarkable.

On physical examination, the patient had stable vital signs with a blood pressure of 120/70 mm Hg, heart rate 90/min, and temperature of 98.4°F. She appeared comfortable but with marked pallor. Her abdomen was soft, non-tender, non-distended, and revealed no costovertebral angle tenderness. The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable.

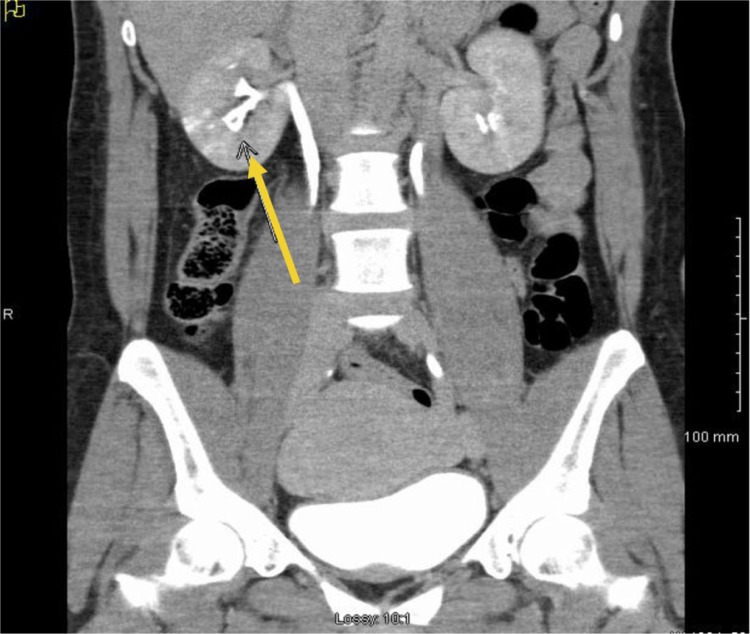

Laboratory data revealed hemoglobin of 5.7 g/dl, hematocrit 17.2%, platelets 317 K/µl, INR 0.93., and creatinine of 0.9 mg/dl. Other pertinent laboratory values showed bilirubin of 1.1, LDH of 139 U/L, and haptoglobin of 90 mg/dl. Hemoglobin electrophoresis demonstrated Hb A 74.7%, Hb A2 2.9%, Hb F 0.4%, and Hb S 22%, but it was drawn after transfusion. Urinalysis showed numerous red blood cells (RBCs), 2+ protein, and 2–5 WBC/HPF. Peripheral smear, vasculitis work up, or urine culture were not performed. Initial CT scan of abdomen and pelvis revealed hyper dense material in collecting system of right kidney extending into renal pelvis but no aneurysm or calculus was demonstrated. Later patient underwent renal angiography, which demonstrated normal arterial anatomy. She also underwent CT urography that revealed a filling defect within the pyramid of the lower pole of the right kidney representing papillary necrosis as demonstrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Computerized tomography urography depicting blunting of renal calyx of right kidney (see arrow).

The patient was managed conservatively during the hospital course. She was transfused with 3 units of blood and blood counts remained stable after transfusion. In the beginning, our differential diagnosis was broad, including renal papillary necrosis, IgA nephropathy, bladder cancer, and renal medullary carcinoma. But the diagnosis was narrowed down to renal papillary necrosis after CT urography was performed. Patient was started on sodium bicarbonate infusion along with aggressive hydration and diuretics. After 3 days of treatment, her hematuria had completely resolved and she was discharged home in stable condition.

Renal papillary necrosis and sickle cell trait

SCT is a carrier state of sickle cell disease with one copy of normal beta globulin gene and one copy of sickle variant gene-producing heterozygous HbAS (1). SCT is estimated to have prevalence of 300 million worldwide, mostly concentrated in Africa, Middle East, and Mediterranean region (2). In the United States, the prevalence of SCT is around 8–10% in African American population (3). Although SCT is considered a benign condition with no increased mortality in individuals (4), it has been associated with several complications (2).

A number of abnormalities have been reported in SCT, including renal medullary carcinoma, papillary necrosis, thromboembolic events, and hyposthenuria (5, 6). Renal complications are listed in Table 1 (7, 8). Our discussion will be limited to renal papillary necrosis.

Table 1.

Renal complications of sickle cell trait

| Renal medullary carcinoma |

| Renal papillary necrosis |

| Hyposthenuria |

| Hematuria |

Renal papillary necrosis is frequently associated with sickle cell disease, but it is not uncommon in SCT as well. It has been usually associated with diabetes, analgesic nephropathy, chronic pyelonephritis, and renal tuberculosis. Renal papillary necrosis is usually precipitated by some factors such as intense exercise, dehydration, and taking NSAIDs. In our patient, none of these factors were present. To date no comparative data exist with regard to the distribution and frequency of occurrence of renal papillary necrosis among persons with SCT, hemoglobin SC, and thalassemias (5, 9); however, there have been case reports on hemoglobin SC (9, 10) but none to date on thalassemia unless associated with a sickling hemoglobin (Sβ+) (11).

Pathophysiology

Papillary necrosis results from obstruction of the vasa recta producing ischemia and micro infarction of medullary region of the kidneys (12). Polymerization of the RBCs in the vasa recta of the renal medulla is the main trigger for renal papillary necrosis. Numerous factors are involved in initiating the sickling of RBCs including hypoxia, hypertonicity, and acidosis (13). Once sickling starts it leads to increased blood viscosity and decreased blood flow to medulla, which ultimately results in micro infarction of vasa recta causing papillary necrosis. The extent of polymerization of RBCs depends upon the concentration of HbS (11).

Clinical features

The clinical presentation varies from painless gross hematuria to acute condition with pain, fever, and obstructive urinary symptoms (14, 15). Hematuria is by far the most important clinical feature. It usually manifests in the age group between 30–40 years and there seems to be no sex predominance (16). Any patient with SCT, who presents with hematuria, needs a thorough clinical investigation especially in young patients because renal medullary carcinoma can also presents in a similar fashion. Renal medullary carcinoma is a rare, aggressive fatal tumor, which presents in young patients with SCT (6). Because renal medullary cancer is very rare, there is no epidemiological data available, but according to one report in 2003, there are 55 cases of renal medullary cancer that were reported in literature (6).

Diagnosis

Renal papillary necrosis should be in the differential diagnosis in any SCT patient who comes in with hematuria. Imaging studies are the mainstay of diagnosing this condition. Intravenous pyelogram has been traditionally used for establishing the diagnosis but it is now largely replaced with CT urography because of its high sensitivity and specificity (17, 18). CT urography is also superior to other imaging studies because of its ability to diagnose papillary necrosis in early stages (19) but more studies are required for comparison between IVP, ultrasound, and CT urography. In all reported cases, there was no biopsy performed and renal angiogram is not required for diagnosis. In SCT, the most common abnormality on urinalysis is microscopic hematuria that can also be macroscopic. However, there is limited data on the prevalence of these findings. The most common findings on urinalysis of patients with sickle cell disease is proteinuria as this proteinuria occurs in 20–30% of patients with sickle cell disease. Hemoglobinuria and RBC casts can also occur. Additionally, there is decreased concentrating ability with urine osmolarity of 400–450 mOsm/kg under water deprivation (12). Hemoglobin electrophoresis is not required for diagnosis nor is there any renal correlation.

Management

Although there are no large studies done to standardize the treatment of papillary necrosis secondary to SCT, the underlying pathophysiology guides the treatment modalities. As mentioned earlier, papillary necrosis starts with sickling of RBCs, which is itself affected by factors like acidosis, hypertonicity, and hypoxia. If we can reduce these factors then papillary necrosis can be contained. Treatment options that have been utilized are listed in the Table 2, (7, 15, 16). Initial management involves conservative measures, as most of the cases of hematuria are self-limiting. Patient should be started on hypotonic fluids along with diuretics to increase the urine flow and reduce the tonicity in the medullary interstitial area. Hypotonic fluids correct dehydration and diuretics help in increasing urinary flow. Sodium bicarbonate is also used to alkalinize the urine, which reduces the acidosis, but whether it prevents further necrosis is uncertain. In some reports desmopressin (increases clotting by dose-dependent increase in plasma factor VIII, and vWF) and Epsilon-amino caproic acid (inhibits fibrinolysis by inhibiting plasmin activity) can be used to treat hematuria in resistant patients (7, 20–22). If all the aforementioned measures fail, then invasive measures can be taken which involve renal artery embolization and nephrectomy.

Table 2.

Management options for renal papillary necrosis

| 1 | Bed rest and hydration |

| 2 | Hypotonic fluid resuscitation with diuretics |

| 3 | Sodium bicarbonate to reduce acidosis |

| 4 | Desmopressin |

| 5 | Epsilon-aminocaproic acid |

| 6 | Renal artery embolization or nephrectomy if conservative measures fail to resolve hematuria. |

Conclusion

Renal papillary necrosis is a rare complication of SCT. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis of gross hematuria, especially in sickle cell patients, because if it is not caught earlier it can lead to devastating complications. Conservative measures should always be tried first before attempting invasive procedures.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

References

- 1.Ashley-Koch A, Yang Q, Olney RS. Sickle hemoglobin (HbS) allele and sickle cell disease: a HuGE review. Ame J Epidemiol. 2000;151:839–45. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsaras G, Owusu-Ansah A, Boateng FO, Amoateng-Adjepong Y. Complications associated with sickle cell trait: a brief narrative review. Am J Med. 2009;122:507–12. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Motulsky AG. Frequency of sickling disorders in U.S. blacks. N Engl J Med. 1973;288:31–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197301042880108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashcroft MT, Desai P. Mortality and morbidity in Jamaican adults with sickle-cell trait and with normal haemoglobin followed up for twelve years. Lancet. 1976;2:784–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)90612-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sears DA. The morbidity of sickle cell trait: a review of the literature. Am J Med. 1978;64:1021–36. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(78)90458-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dimashkieh H, Choe J, Mutema G. Renal medullary carcinoma: a report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:e135–8. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-e135-RMCARO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiryluk K, Jadoon A, Gupta M, Radhakrishnan J. Sickle cell trait and gross hematuria. Kidney Int. 2007;71:706–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heller P, Best WR, Nelson RB, Becktel J. Clinical implications of sickle-cell trait and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency in hospitalized black male patients. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1001–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197905033001801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serjeant GR. The sickle cell trait. In: Serjeant GR, editor. Sickle cell disease . 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992. pp. 415–25. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sears DA. Sickle cell trait. In: Embury SH, Hebbel RP, Mohandas N, Steinberg MH, editors. Sickle cell disease: basic principles and clinical practice . New York: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 381–94. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta AK, Kirchner KA, Nicholson R, Adams JG, Schechter AN, Noguchi CT, et al. Effects of alpha-thalassemia and sickle polymerization tendency on the urine-concentrating defect of individuals with sickle cell trait. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:1963–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI115521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pham PT, Pham PC, Wilkinson AH, Lew SQ. Renal abnormalities in sickle cell disease. Kidney Int. 2000;57:1–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lange RD, Minnich V, Moore CV. Effect of oxygen tension and of pH on the sickling and mechanical fragility of erythrocytes from patients with sickle cell anemia and the sickle cell trait. J Lab Clin Med. 1951;37:789–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alhwiesh A, Saudi J. An update on sickle cell nephropathy. Kidney Dis Transpl. 2014;25:249–65. doi: 10.4103/1319-2442.128495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allon M. Renal abnormalities in sickle cell disease. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:501–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zadeii G, Lohr JW. Renal papillary necrosis in a patient with sickle cell trait. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:1034–9. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V861034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warshauer DM, McCarthy SM, Street L, Bookbinder MJ, Glickman MG, Richter J, et al. Detection of renal masses: sensitivities and specificities of excretory urography/linear tomography, US, and CT. Radiology. 1988;169:363–5. doi: 10.1148/radiology.169.2.3051112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gray Sears CL, Ward JF, Sears ST, Puckett MF, Kane CJ, Amling CL. Prospective comparison of computerized tomography and excretory urography in the initial evaluation of asymptomatic microhematuria. J Urol. 2002;168:2457–60. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64167-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lang EK, Macchia RJ, Thomas R, Davis R, Ruiz-Deya G, Watson RA, et al. Multiphasic helical CT diagnosis of early medullary and papillary necrosis. J Endourol. 2004;18:49–56. doi: 10.1089/089277904322836677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baldree LA, Ault BH, Chesney CM, Stapleton FB. Intravenous desmopressin acetate in children with sickle trait and persistent macroscopic hematuria. Pediatrics. 1990;86:238–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moudgil A, Kamil ES. Protracted, gross hematuria in sickle cell trait: response to multiple doses of 1-desamino-8-D-arginine vasopressin. Pediatr Nephrol. 1996;10:210–2. doi: 10.1007/BF00862083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Immergut MA, Stevenson T. The use of epsilon amino caproic acid in the control of hematuria associated with hemoglobinopathies. J Urol. 1965;93:110–11. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)63728-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]