Significance

Epstein–Barr virus establishes a life-long latent infection (i.e., no virus is produced) in B cells in most people worldwide. A specific group of latency-associated proteins is expressed in B-cell and epithelial malignancies and likely contributes to tumorigenesis, but the role of epithelial cells in the virus life cycle is not well understood. We grew epithelial cells in organotypic cultures, allowing the cells to differentiate and stratify as they do in vivo. Unlike B-cell infection, EBV infection of epithelial cultures resulted in spontaneous production of high levels of virus, likely expanding the virus pool and increasing efficiency of transmission. This model of EBV-infected epithelium will enhance our understanding of the role of epithelial cells in the EBV life cycle.

Keywords: Epstein–Barr virus, epithelial, organotypic culture, productive replication

Abstract

Epstein–Barr virus is a ubiquitous human herpesvirus associated with epithelial and lymphoid tumors. EBV is transmitted between human hosts in saliva and must cross the oral mucosal epithelium before infecting B lymphocytes, where it establishes a life-long infection. The latter process is well understood because it can be studied in vitro, but our knowledge of infection of epithelial cells has been limited by the inability to infect epithelial cells readily in vitro or to generate cell lines from EBV-infected epithelial tumors. Because epithelium exists as a stratified tissue in vivo, organotypic cultures may serve as a better model of EBV in epithelium than monolayer cultures. Here, we demonstrate that EBV is able to infect organotypic cultures of epithelial cells to establish a predominantly productive infection in the suprabasal layers of stratified epithelium, similar to that seen with Kaposi’s-associated herpesvirus. These cells did express latency-associated proteins in addition to productive-cycle proteins, but a population of cells that exclusively expressed latency-associated viral proteins could not be detected; however, an inability to infect the basal layer would be unlike other herpesviruses examined in organotypic cultures. Furthermore, infection did not induce cellular proliferation, as it does in B cells, but instead resulted in cytopathic effects more commonly associated with productive viral replication. These data suggest that infection of epithelial cells is an integral part of viral spread, which typically does not result in the immortalization or enhanced growth of infected epithelial cells but rather in efficient production of virus.

Although the association between Epstein–Barr virus and epithelial malignancies has been known for more than three decades, the EBV life cycle within the epithelial milieu is still only poorly understood. In contrast, our broad understanding of the biology of EBV within the B-cell compartment has been facilitated by the ability of EBV to infect and immortalize primary B cells in vitro and by the ability of some EBV-positive B-cell tumors to give rise to cell lines that maintain restricted programs of latency gene expression similar to those seen in vivo. Although in primary EBV infection the entire complement of EBV latency-associated nuclear proteins (EBNAs 1, 2, 3A, 3B, 3C, and LP) and membrane proteins (LMPs 1, 2A, and 2B) promote cellular proliferation and survival (Latency III), EBV gene expression must be progressively silenced (Latency II; EBNA1 and LMPs 1 and 2) so that the most restricted program, Latency 0 (in which EBV gene expression is believed to be completely silenced), is achieved in resting memory B cells that serve as the long-term reservoir of latent EBV (1, 2). Because EBNA1 functions to maintain the viral genome during cell division, it alone among the viral protein repertoire is required during periodic proliferation of these memory B cells (Latency I).

EBV is strongly associated with subtypes of nasopharyngeal carcinoma and gastric carcinoma, in which it exhibits a Latency I/II program of gene expression (3–5). The presence of latent EBV in epithelial malignancies suggests that EBV might establish a latent infection within primary epithelial cells. In biopsies of oral hairy leukoplakia (OHL), a benign hyperplastic lesion that occurs in immunocompromised individuals, active EBV replication is detected in suprabasal layers of lingual epithelium (6), providing convincing evidence that EBV can infect epithelial cells and undergo productive replication. Similar patterns could be found in biopsies of normal tongue tissue, but in only a small fraction of samples (3 of 217) (7). In contrast, little evidence of latently infected cells is observed, although such cells might be rarer and more difficult to detect. Indeed, possible latently infected epithelial cells are detected in tonsil explants in the presence of acyclovir (an inhibitor of lytic cycle-specific herpesvirus DNA replication), but in less than 0.01% of cells (8).

Unfortunately, EBV-infected cell lines cannot be established readily from epithelial tumors, and primary epithelial cells are infected inefficiently in vitro. Nevertheless, EBV infection of primary keratinocytes in monolayer culture results in latency, as evidenced by the expression of Epstein–Barr virus RNA (EBER), with variable expression of EBNA-1 and LMP-1, but the infected cells fail to proliferate (8–10). Although these problems have hindered progress in understanding the life cycle of EBV in epithelial cells, a few EBV-negative epithelial tumor cell lines can be infected with EBV, resulting in Latency II gene expression, and have provided some insight. One notable example is EBV tropism. Although EBV must cross the oral mucosa to gain access to either the B-cell compartment or the oral cavity, whether it infects oral mucosal epithelial cells (with or without a latent infection) to amplify the virus pool or merely crosses the epithelial barrier by transcytosis has been debated (11, 12). However, tropism is controlled during in vitro infection by differences in the glycoprotein profile of virions derived from B versus epithelial cells (13), and virus isolated from the saliva of normal individuals is consistent with that derived from epithelial cells (14). Taken together, these observations suggest that EBV indeed can replicate within the epithelial cell compartment in vivo.

To assess better the outcome(s) of EBV infection in an environment more representative of normal epithelium in the host, we examined EBV infection within organotypic (raft) cultures of primary oral keratinocytes. Although these cultures do not contain the complexity of tissues and interactions found in vivo, in all other respects the stratified layers of differentiated tissue generated in vitro resemble the differentiated epithelium, where EBV has been detected in vivo. We demonstrate that EBV is able to infect keratinocytes in raft cultures, and, although we were unable to detect latently infected cells, we readily observed production of virus in the suprabasal layers that was readily disseminated throughout the epithelium, resulting in numerous productively replicating cells. Thus, EBV is able to infect normal epithelial cells and enter the productive cycle to expand the virus pool.

Results

EBV Infects Raft Cultures Generated from Primary Keratinocytes.

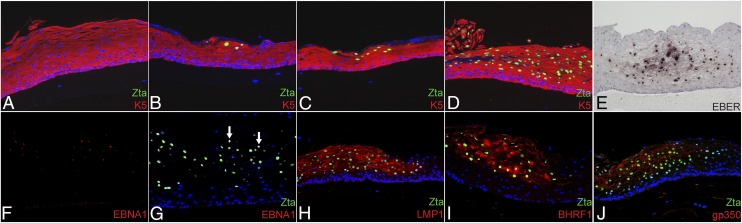

Because EBV inefficiently infects keratinocytes in monolayer culture, we sought to determine whether raft cultures, which more accurately reflect epithelial tissue in vivo, could be efficiently infected with EBV. Raft cultures were generated from primary human keratinocytes from either gingiva (PGEC) or tonsil (PTEC). Because cell-associated virus most efficiently infects keratinocytes in monolayer cultures, productively replicating EBV-positive Burkitt lymphoma (Akata) cells were applied to the scored surface of a raft culture 4 d after cells were lifted to the air–liquid interface. Because the EBV-BZLF1 transcriptional activator (Zta) is expressed not only during the productive cycle but also early during primary infection in both B and epithelial cells regardless of whether latency is established (10, 15), we first used Zta expression to identify EBV-infected cells at various times postinfection (p.i.) of rafts generated with PGEC (Fig. 1). At 2 d p.i., we detected individual or small clusters of Zta-expressing cells in epithelial marker keratin 5 (K5)-positive cells in the suprabasal layers (Fig. 1B). The number of Zta-expressing cells increased over time and by 6 d p.i. represented the majority of suprabasal cells (Fig. 1 C and D). Identical results were obtained with PTECs (Fig. S1A), and similar results were obtained with unscored rafts. Cell-free virus infects keratinocytes inefficiently in monolayer cultures (9, 16), but we found that B cell-derived cell-free EBV infected and spread throughout the raft culture (Fig. S1B), although less efficiently than cell-associated virus.

Fig. 1.

EBV infection results in discrete foci of cells that predominantly express productive cycle proteins. EBV-infected raft cultures were examined for expression of both latency-associated and productive-cycle proteins. (A–D) Zta expression was monitored in K5-expressing cells in mock-infected rafts at 6 d (A) or in EBV-infected PGEC rafts at 2 (B), 4 (C), and 6 (D) d p.i. with B-cell–associated virus. (E) In situ hybridization was performed for EBER transcripts at 4 d p.i. (F–J) Sections were analyzed at 6 d p.i. for EBNA-1 alone (F) or with Zta (G) (arrows indicate EBNA1-expressing cells), LMP1 (H), or productive-cycle proteins BHRF1 (I) or gp350 (J). Micrographs are representative of data from three sets of patient PGEC samples. DNA was stained with Hoechst (A–D and F–J) or hematoxylin (E). (Magnification: 10×.)

EBV-Infected Cells Concurrently Express Gene Products of the Latent and Productive Cycles.

As a sensitive means of detecting all forms of latent infection, including restricted latency, we examined by in situ hybridization the expression of the small noncoding EBER, which is highly expressed in all known programs of EBV latency. Hybridization to the EBER probe was analyzed at days 2 and 4 p.i., before the peak of productive replication, and was detected in discrete foci confined to the suprabasal epithelium and colocalizing with Zta expression in adjacent sections but not in the basal epithelium (Fig. 1E). Because both EBV-infected epithelial cells in monolayer culture and EBV-associated epithelial malignancies express Latency I/II genes, we analyzed the expression of EBNA1 and LMP1 in raft cultures. LMP1 was readily detected in the majority of Zta-expressing cells from days 2–10 p.i., but EBNA1 was not detected until day 4 p.i., and then only in very few cells (Fig. 1 F–H and Table 1). EBNA2 (a marker of Latency III) also was expressed at day 4 p.i. in a subset of Zta-expressing cells (Fig. S2). None of these latency-associated proteins was detected in cells of the basal layer or within uninfected raft cultures.

Table 1.

Expression of EBV proteins

| Days p.i. | EA-D | BHRF1 | gB | gp350 | EBNA1 | LMP1 | EBNA2 | Ki67 | Involucrin | Casp3 |

| 2 | 94.2 ± 0.8 | 94.5 ± 2.5 | 60.2 ± 10.3 | 16.2 ± 5.4 | 0.9 ± 1.1 | 93.6 ± 5.7 | 2.4 ± 3.0 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 7.6 ± 3.2 (2.4 ± 0.3) |

| 4 | 98.4 ± 0.4 | 96.9 ± 0.7 | 89.1 ± 3.6 | 68.5 ± 10.2 | 23.9 ± 10.0 | 99.8 ± 0.3 | 15.4 ± 5.0 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 6.9 ± 1.9 (0.8 ± 0.5) |

| 6 | 97.3 ± 1.8 | 97.4 ± 0.5 | 87.1 ± 8.8 | 64.7 ± 10.9 | 38.2 ± 7.5 | 99.7 ± 0.5 | 26.9 ± 2.6 | 0.4 ± 0.4 | 99.7 ± 0.5 | 10.5 ± 3.6 (1.9 ± 1.1) |

Numbers shown are the percentage of Zta-positive cells expressing the indicated viral or cellular protein from three experiments ± SD. Numbers in parentheses indicate percentage of cleaved caspase 3-positive cells in matching layers of mock-infected tissue.

Because the immediate-early gene-encoded Zta was detected in the absence of convincing evidence of a latent infection, and because Zta initiates the cascade of productive-cycle proteins, we examined whether other productive-cycle proteins encoded by EBV early and late genes were expressed. By day 2 p.i., the majority of Zta-expressing cells also expressed early proteins such as BHRF1 (the viral antiapoptotic bcl-2 homolog) and EA-D (the EBV DNA polymerase processivity factor); to a lesser extent, we detected the late-gene glycoproteins gp350, which binds to the B-cell receptor, and gB, the fusion protein (Fig. 1 I and J and Fig. S2). Table 1 summarizes the percentage of Zta-expressing cells that coexpressed each of the viral proteins in multiple experiments. Notably, none of the latency-associated proteins was detected in the absence of productive-cycle proteins. Thus, infected cells clearly appeared to be in the productive cycle of replication.

EBV Does Not Affect Cellular Proliferation or Early Differentiation but Induces Cytopathology.

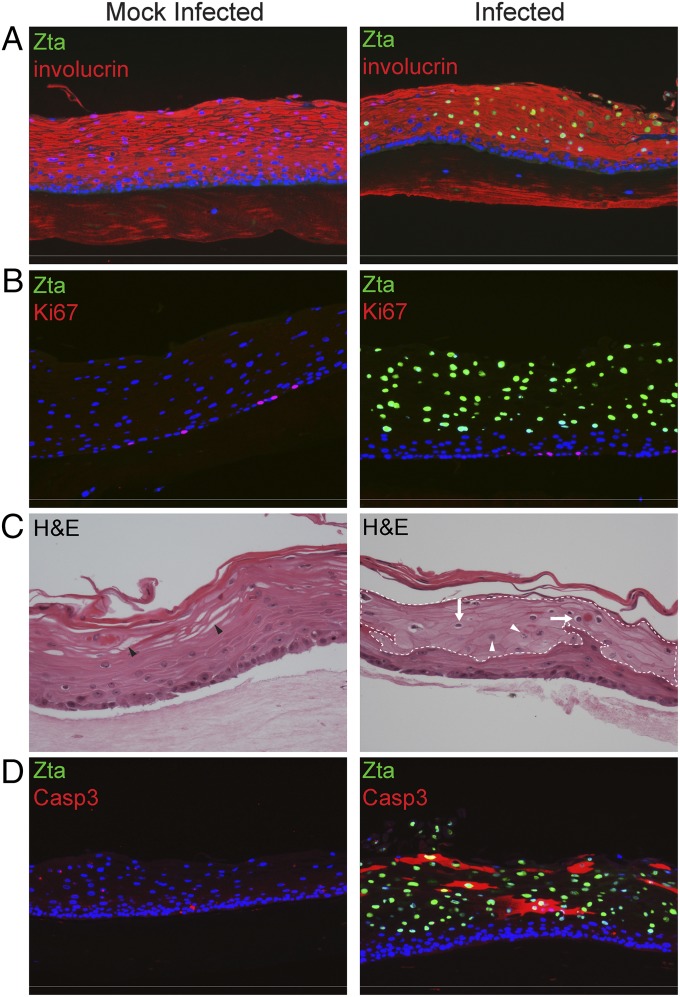

In raft cultures generated from epithelial cell lines, exogenous expression of LMP1, LMP2A, LMP2B, or BHRF1 alone promotes epithelial cell proliferation with a corresponding decrease in differentiation, functions likely to contribute to tumorigenesis (17–20). Although keratin 10 (K10) often is used as a marker of differentiation, it is not well expressed in oral epithelium (21–23) and, in our hands, was not expressed throughout the suprabasal layers. Thus, to examine whether EBV infection resulted in changes in differentiation, we analyzed expression of the early differentiation markers involucrin, which is generally coexpressed with K10, and K5. We observed no changes in K5 or involucrin expression in EBV-infected cells (Fig. 2A), and viral proteins were not detected in cells expressing the cell-proliferation marker Ki67 (Fig. 2B). Instead, EBV-infected cells exhibited cytopathic effects commonly seen with active viral replication, including koilocytosis [cells with enlarged nuclei and a prominent perinuclear halo of cytoplasmic clearing often seen in cells infected with human papilloma virus (HPV)], reduced cytoplasmic glycogen resulting in vacuolization, decreased staining likely caused by hypokeratinization and “ground glass” nuclei indicative of peripheral margination of chromatin (Fig. 2C; a larger image is presented in Fig. S3). Despite expression of the EBV BHRF1 protein, infected tissue contained increased cleaved caspase 3 (casp3) relative to mock-infected tissue (Fig. 2D), although casp3 was not restricted to Zta-positive cells. Table 1 summarizes the percentage of Zta-expressing cells that coexpress each of the cellular markers examined.

Fig. 2.

EBV infection does not alter expression of cellular proliferation or differentiation markers but induces cytopathology. (A and B) Mock-infected or EBV-infected PGEC rafts were examined for expression of Zta and the cellular protein involucrin, an epithelial differentiation marker (A) and Ki67, a replication marker (B), at 6 d p.i. (C) Changes in cellular morphology were observed by H&E staining at 4 d p.i. Koilocytes are indicated by white arrows, ground glass nuclei by white arrowheads, and vacuoles resulting from cytoplasmic glycogen by black arrowheads. EBV-infected cells were identified by Zta expression in adjacent sections indicated by the dotted white line. (D) Sections were costained for Zta and cleaved casp3 at 6 d p.i. Micrographs are representative of data produced from three sets of patient samples. EBV-infected cells were identified by Zta expression, and nuclei were identified by Hoechst staining. (Magnification: 10× in A, B, and D; 20× in C.)

High Levels of Virion Production in Infected Raft Cultures.

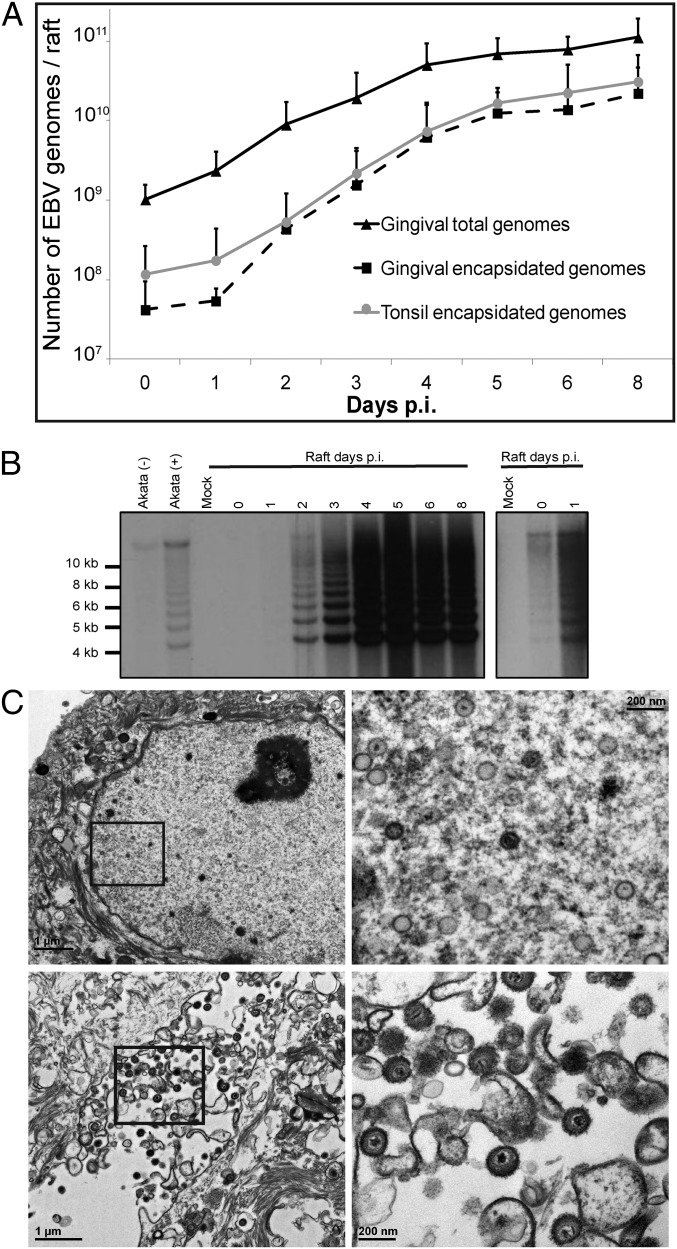

We next assessed amplification of the viral genome by quantitative PCR (qPCR) to determine whether the expression of the representative EBV lytic-cycle proteins translated to production of infectious virions. EBV DNA was not detected in mock-infected tissue from any patient sample. In contrast, the total number of viral genomes in EBV-infected raft cultures at day 8 p.i. had increased ∼100-fold relative to day 0 (i.e., input virus measured 1 h p.i.) (Fig. 3A). Encapsidated genomes, identified by resistance to endonuclease treatment, increased exponentially following an initial lag phase before attaining a plateau by day 8 p.i. in rafts generated from either PGEC or PTEC. Notably, this was a 500- to 1500-fold increase over input virus, with final virus titers as high as 5 × 1010 encapsidated genomes per raft culture. Because the EBV genome is maintained as an episome in latently infected cells but is largely linear during productive replication, these two phases of the viral life cycle can be distinguished by the differential mobility of EBV DNA fragments adjacent to fused DNA termini (found in latent episomal EBV DNA) and to the linear ends (found in productively replicating EBV) by electrophoresis in an agarose gel following restriction endonuclease digestion (24). If latent infection precedes productive replication, we would expect to see an increase in the intensity of the episomal form of the genome before an increase in the linear form of the genome. Instead, linear viral genomes indicative of productive replication were detected as early as day 1 p.i. and overwhelmingly predominated by day 2 p.i. (Fig. 3B). In contrast, episomal genomes were barely detectable early and did not increase significantly following infection. By day 6 p.i., capsids of the appropriate size for EBV (∼100 nm) were readily observed in the nuclei of epithelial cells, as were both naked and enveloped capsids in the cytoplasm and predominately enveloped capsids in the extracellular space (Fig. 3C). To determine whether these capsids were infectious and biologically intact, we infected primary B lymphocytes with virus derived from raft cultures at 1 h and 8 d p.i. Importantly, although B-cell immortalization was not achieved with a virus-containing fraction obtained from raft cultures at 1 h p.i., virus collected at day 8 p.i. efficiently immortalized primary B cells in vitro (Table 2), as is consistent with the production of biologically active EBV from the raft culture.

Fig. 3.

Infection results in viral genome amplification and the production of viral particles. EBV-infected cells were evaluated for EBV DNA amplification (A), genome structure (B), and viral particles (C). (A) Total (▲ PGEC) or encapsidated viral genomes (■ PGEC, ● PTEC) were quantified using qPCR analysis. Numbers represent average values plus SD from three PTEC or four PGEC (with the exception of day 5 p.i., for which there were three patient samples). (B) Termini analysis of the EBV genomes in infected raft tissue. Uninduced (−) and induced (+) Akata cells serve as positive controls for episomal and linear forms of the genome, respectively. Mock-infected raft tissue was used as a negative control. A longer exposure is shown on the right. Data are representative of experiments conducted using two sets of patient samples. (C) Transmission electron microscopy of cells isolated from PGEC rafts 6 d p.i. Boxed areas are shown at higher magnification on the right. Naked capsids can be seen in the nuclei of infected cells (Upper), and enveloped virions can be seen aligning on the plasma membrane of infected epithelial cells (Lower). Cells isolated from mock-infected tissue were used as a negative control.

Table 2.

Raft-derived virus immortalizes primary B cells in vitro

| Virus source* | Dilution | Tissue sample 1 | Tissue sample 2 | ||

| MOI | % wells† | MOI | % wells† | ||

| Mock | 10−2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 h p.i. | 10−2 | 0.64 | 0 | 15.32 | 0 |

| 1 h p.i. | 10−3 | 0.06 | 0 | 1.53 | 0 |

| 8 d p.i. | 10−3 | 101.65 | 100 | 729.11 | 100 |

| 8 d p.i. | 10−4 | 10.16 | 100 | 72.91 | 100 |

| 8 d p.i. | 10−5 | 1.02 | 80 | 7.29 | 100 |

MOI, multiplicity of infection.

Virus was isolated from rafts at various times p.i. as indicated.

Number of wells with proliferating cells at 6 wk p.i.

The Antiviral Drug Acyclovir Inhibits Productive Replication and Dissemination.

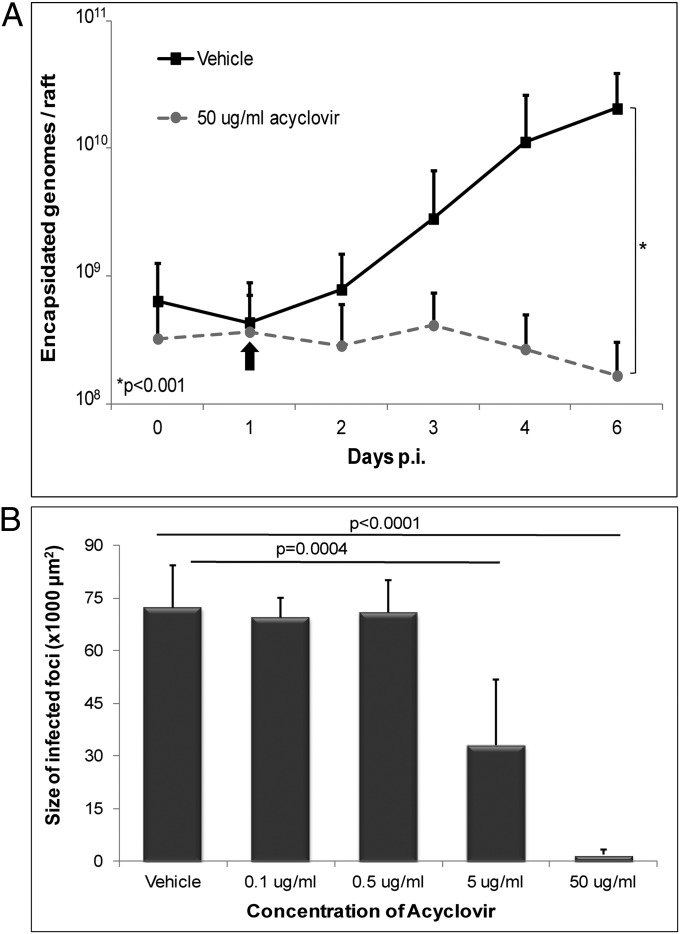

The absence of a detectable latent infection and the short lag time to expression of productive-cycle proteins suggested that the spread of infection throughout the raft culture was caused by infection by newly replicated virus from an originally small number of infected cells. To confirm this possibility, we treated raft cultures with the anti-herpesvirus drug acyclovir, which inhibits viral DNA replication during the productive cycle of infection. Notably, production of encapsidated genomes in the presence of acyclovir was reduced significantly relative to those treated with vehicle control (Fig. 4A), with an IC50 of 0.88 µg/mL. Furthermore, the size of infected-cell foci in the presence of 5 or 50 μg/mL acyclovir was reduced significantly compared with vehicle control (Fig. 4B), demonstrating that de novo replication of virus was responsible for rapid expansion of infection.

Fig. 4.

Acyclovir inhibits viral spread. PGEC raft cultures were treated 1 d p.i. with acyclovir and were analyzed for genome replication and spread of infection. (A) Encapsidated EBV genomes were quantified by qPCR in cells treated with vehicle (■) or with 50 μg/mL acyclovir (●). Numbers shown are averages plus SD from three experiments using cells from different donors. The number of genomes was log-transformed and used in a linear mixed model, which demonstrated statistical difference (P < 0.001). The EBV genome was not detected in mock-infected tissue from any patient sample. (B) Quantification of the size of the infected foci based on LMP1 expression at 6 d p.i. in rafts cultured in the presence of vehicle or various concentrations of acyclovir. The size of infected foci was measured from at least 10 fields of view at 10× magnification. Bars represent average plus SD using three different patient samples.

Discussion

Although the association of EBV with epithelial malignancies has been known for decades, relatively little is known about the life cycle of the virus in this tissue, largely because of the inability to study it in vitro. Using raft cultures of primary oral keratinocytes, we demonstrate that EBV can infect stratified epithelium in vitro, resulting in a productive infection that culminates in the efficient spread of virus throughout the culture, with little or no true latent infection detected. This pattern appears to resemble closely the epithelial cell infection in OHL and in the very small fraction of normal tongue biopsies in which EBV was detected, where substantial virus replication occurs in the suprabasal layers (6, 7, 25). Thus, our results are consistent with observations in both diseased and normal oral epithelium, and we have been able to track infection over time. We also detected both EBNA1 and LMP1 in productively infected cells. Although both proteins are typically considered latency-associated, they also are expressed during productive infection in both B cells and OHL biopsies, and specific roles in this phase of the virus life cycle have been proposed (26–28). Because the suprabasal cells did not express the marker of cellular proliferation, Ki67, the large increase in EBV-infected cells ultimately observed in the raft cultures was unlikely to be caused by proliferation of the infected cells, as one might expect in response to the expression of latency-associated proteins (a low level of EBNA2 was detected also). Rather, inhibition of the expansion of infected cells by acyclovir indicates that the increase in infected cells is the consequence of virus replication and spread within the culture. Further, the production of high titers of virus (up to 5 × 1010 encapsidated genomes per raft) in the absence of induction of replication by external stimuli, as needed to promote virus production in latently infected B and epithelial cell lines in vitro, is consistent with a natural ability of oral epithelial cells to support the high levels of productive replication calculated to be necessary to generate the high viral titers of EBV observed in saliva (29).

The epithelial cells of the oral cavity that are susceptible to EBV infection are not known. Tonsils have been proposed as a primary target because of their close association with the lymphatic system and the identification of EBV-infected naive B cells within tonsils, although there are few data to support EBV infection of tonsillar epithelium. Although the epithelial receptor for EBV is not known, the mRNA for the EBV receptor on B cells, CD21, is expressed in tonsillar epithelial cells, but not uvula, soft palate, tongue, or buccal mucosa epithelial cells (30). However, in AIDS patients, OHL is observed in tongue, buccal, and even gingival surfaces, supporting the possibility of an alternate receptor for EBV infection of epithelial cells. We observed no difference in the levels of infection or virus production between raft cultures established from either tonsil or gingival keratinocytes, suggesting that EBV does not preferentially target tonsil epithelium and that models of EBV infection of oral mucosa should not be limited to this anatomical site.

Given that the EBV productive cycle is induced by differentiation in B cells and epithelial cells in monolayer culture in vitro (9, 16, 31–34), the productive replication we observed in the differentiating suprabasal cells was not surprising. In B cells, this process is initiated by the spliced form of the transcription factor X-binding protein 1s (Xbp-1s) and is increased during the unfolded protein response (UPR) that can activate the viral transcription factor Zta and Rta promoters to initiate virus replication (31, 32). The UPR also is activated during epithelial cell differentiation, and EBV productive replication is observed in OHL cells expressing Blimp1, which is downstream of UPR (35). Similarly, productive replication of the gammaherpesvirus Kaposi’s-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), initiated in B cells by Xbp-1s–mediated induction of Rta (36), occurs in suprabasal layers of organotypic cultures (37), whereas the alphaherpesviruses HSV1, HSV2, and varicella zoster virus replicate in basal cells (38–40). Thus, it is likely that the UPR induces the productive replication we observe, suggesting that the gammaherpesviruses have evolved similar mechanisms for viral spread.

Because EBV can infect keratinocytes in monolayer culture, which maintain a basal cell-like phenotype, we anticipated that EBV might establish a latent infection in the less differentiated cells of the basal layer. However, we were unable to detect EBV protein expression or the normally highly expressed EBERs in the basal layer. Although EBER expression is the gold standard for detection of EBV in all latently infected B cells and in both B-cell and epithelial tumors, they are not seen in OHL by Northern blot analysis (41), suggesting a latency-only pattern of expression. This fact suggests that the staining we observed in the suprabasal layer was likely caused by the hybridization to the high levels of replicating EBV DNA rather than by the EBERs themselves and that in situ hybridization for EBERs may not be the best technique to identify rare latently infected epithelial cells in normal stratified epithelium where EBV is replicating. Indeed, EBV-infected cells that are not proliferating or that proliferate slowly, such as rare basal stem cells, may not express any viral gene products, similar to resting memory B cells, or may express them at levels below the limit of detection. Because Zta expression was seen initially only in isolated cells at a low frequency, and EBV does not appear to induce the proliferative capacity of infected cells, it is likely that the number of primary infected cells is low. Low numbers would contribute to our inability to detect them if indeed they are in the basal layer. A second possible explanation for the inability to detect EBV in the basal layer is that EBV infects only cells in the suprabasal layer of the raft and rarely, if ever, infects cells in the basal layer. Infection of suprabasal cells where UPR is activated likely would preclude the establishment of a persistent latent infection and instead would result in productive infection. This situation could arise as an artifact of our system in which the virus might not access the basal surface efficiently or result from the lack of other cell types that might play a role in infection from the basal surface (42, 43). Alternatively, a receptor or coreceptor might be expressed more efficiently on differentiated cells; although some investigators observe increased infection in more differentiated keratinocytes (9), others do not (8). If EBV were unable to infect basal cells, it would be unlike the other herpesviruses analyzed in organotypic culture to date (37–40).

Finally, organotypic cultures have been generated with epithelial cell lines expressing exogenous LMP1, BHRF1, LMP2A, or LMP2B, and cellular changes typically associated with EBV-associated carcinomas, such as hyperproliferation and decreased differentiation, were observed (17–20). These data are in contrast to the cytopathic effects typical of productive viral replication, including koilocytosis and increased cleavage of casp3, that we observed in the suprabasal layers and likely reflect differences between primary keratinocytes and immortal or transformed epithelial cells that express individual EBV proteins throughout all layers of the stratified epithelium. It should be noted that the infected cells expressing cleaved casp3 may not actually be undergoing apoptosis in the presence of EBV gene products, notably the antiapoptotic BHRF1. Interestingly, human papilloma virus induces cleavage of casp3 in differentiated epithelium to cleave the viral E1 protein for efficient genome replication (44); perhaps EBV employs a similar strategy.

In summary, our finding that EBV appears to replicate naturally within primary stratified epithelium is in stark contrast to the predominantly latency-associated gene expression seen in EBV-associated epithelial tumors and established epithelial lines infected in vitro. Although at this point we cannot rule out the establishment of latency in our cell model, because latency may occur in only a very small percentage of cells and/or in cells that may have gone unnoticed because of undetectable viral protein (e.g., EBNA1 and LMP1) or even EBER expression, it is clear that in the absence of cell-transforming stimuli, at least one natural role of epithelial cells in the EBV life cycle is to support the replication and spread of virus within the host population, as seen in other herpesviruses and in HPV. Organotypic cultures therefore should be an invaluable tool with which to probe further the contribution of the epithelium to EBV biology, as well as mechanisms of epithelial cell transformation associated with EBV infection.

Materials and Methods

Cells and Raft Cultures.

PGEC and PTEC raft cultures were established as previously described (23) and as described in SI Materials and Methods. Raft cultures were infected 4 d post airlifting by wounding the tissue and adding 2.5 × 106 virus-producing Akata cells or cell-free virus to the top of the wounded raft.

Statistical Analysis.

A growth-curve statistical model (based on a linear mixed model) was built to compare the rate of change in the number of viral particles in raft cultures treated with vehicle or 50 ug/mL acyclovir; the number of encapsidated genomes was log-transformed. The size of the infected foci in the presence of acyclovir also was analyzed using log-transformed area by a linear mixed model. All analyses were performed using statistical software SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute). Statistical significance was defined as P ≤ 0.05.

Additional details of materials and methods are given in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Lori Frappier, Lindsey Hutt-Fletcher, and George Miller for providing reagents; Roland Myers for assistance with electron microscopy; Dr. Catherine Abendroth for analysis of H&E sections; Mary Ferguson for technical assistance; and Dr. Jeffery Sample for critical reading of the manuscript. This research was supported by National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Grant DE021583 (to C.E.S.) and by the Penn State Hershey Cancer Institute and was conducted, in part, under a grant from the Pennsylvania Department of Health using Tobacco Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement Funds. R.M.T. was supported by NIH Training Grant T32 CA60395.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Commentary on page 16242.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1400818111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hochberg D, et al. Demonstration of the Burkitt’s lymphoma Epstein-Barr virus phenotype in dividing latently infected memory cells in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(1):239–244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2237267100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thorley-Lawson DA, Hawkins JB, Tracy SI, Shapiro M. The pathogenesis of Epstein-Barr virus persistent infection. Curr Opin Virol. 2013;3(3):227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niedobitek G, et al. Expression of Epstein-Barr virus genes and of lymphocyte activation molecules in undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinomas. Am J Pathol. 1992;140(4):879–887. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niedobitek G, et al. Epstein-Barr virus and carcinomas. Expression of the viral genome in an undifferentiated gastric carcinoma. Diagn Mol Pathol. 1992;1(2):103–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.zur Hausen H, et al. EBV DNA in biopsies of Burkitt tumours and anaplastic carcinomas of the nasopharynx. Nature. 1970;228(5276):1056–1058. doi: 10.1038/2281056a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenspan JS, et al. Replication of Epstein-Barr virus within the epithelial cells of oral “hairy” leukoplakia, an AIDS-associated lesion. N Engl J Med. 1985;313(25):1564–1571. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198512193132502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frangou P, Buettner M, Niedobitek G. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection in epithelial cells in vivo: Rare detection of EBV replication in tongue mucosa but not in salivary glands. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(2):238–242. doi: 10.1086/426823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pegtel DM, Middeldorp J, Thorley-Lawson DA. Epstein-Barr virus infection in ex vivo tonsil epithelial cell cultures of asymptomatic carriers. J Virol. 2004;78(22):12613–12624. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12613-12624.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feederle R, et al. Epstein-Barr virus B95.8 produced in 293 cells shows marked tropism for differentiated primary epithelial cells and reveals interindividual variation in susceptibility to viral infection. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(3):588–594. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shannon-Lowe C, et al. Features distinguishing Epstein-Barr virus infections of epithelial cells and B cells: Viral genome expression, genome maintenance, and genome amplification. J Virol. 2009;83(15):7749–7760. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00108-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gan YJ, Chodosh J, Morgan A, Sixbey JW. Epithelial cell polarization is a determinant in the infectious outcome of immunoglobulin A-mediated entry by Epstein-Barr virus. J Virol. 1997;71(1):519–526. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.519-526.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tugizov SM, Herrera R, Palefsky JM. Epstein-Barr virus transcytosis through polarized oral epithelial cells. J Virol. 2013;87(14):8179–8194. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00443-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borza CM, Hutt-Fletcher LM. Alternate replication in B cells and epithelial cells switches tropism of Epstein-Barr virus. Nat Med. 2002;8(6):594–599. doi: 10.1038/nm0602-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang R, Scott RS, Hutt-Fletcher LM. Epstein-Barr virus shed in saliva is high in B-cell-tropic glycoprotein gp42. J Virol. 2006;80(14):7281–7283. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00497-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jochum S, Ruiss R, Moosmann A, Hammerschmidt W, Zeidler R. RNAs in Epstein-Barr virions control early steps of infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(21):E1396–E1404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115906109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imai S, Nishikawa J, Takada K. Cell-to-cell contact as an efficient mode of Epstein-Barr virus infection of diverse human epithelial cells. J Virol. 1998;72(5):4371–4378. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4371-4378.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dawson CW, Rickinson AB, Young LS. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein inhibits human epithelial cell differentiation. Nature. 1990;344(6268):777–780. doi: 10.1038/344777a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farwell DG, McDougall JK, Coltrera MD. Expression of Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane proteins leads to changes in keratinocyte cell adhesion. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1999;108(9):851–859. doi: 10.1177/000348949910800906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scholle F, Bendt KM, Raab-Traub N. Epstein-Barr virus LMP2A transforms epithelial cells, inhibits cell differentiation, and activates Akt. J Virol. 2000;74(22):10681–10689. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.22.10681-10689.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dawson CW, Dawson J, Jones R, Ward K, Young LS. Functional differences between BHRF1, the Epstein-Barr virus-encoded Bcl-2 homologue, and Bcl-2 in human epithelial cells. J Virol. 1998;72(11):9016–9024. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9016-9024.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moll R, Franke WW, Schiller DL, Geiger B, Krepler R. The catalog of human cytokeratins: Patterns of expression in normal epithelia, tumors and cultured cells. Cell. 1982;31(1):11–24. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90400-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franke WW, et al. Diversity of cytokeratins. Differentiation specific expression of cytokeratin polypeptides in epithelial cells and tissues. J Mol Biol. 1981;153(4):933–959. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90460-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Israr M, et al. Effect of the HIV protease inhibitor amprenavir on the growth and differentiation of primary gingival epithelium. Antivir Ther. 2010;15(2):253–265. doi: 10.3851/IMP1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raab-Traub N, Flynn K. The structure of the termini of the Epstein-Barr virus as a marker of clonal cellular proliferation. Cell. 1986;47(6):883–889. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90803-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niedobitek G, et al. Epstein-Barr virus infection in oral hairy leukoplakia: Virus replication in the absence of a detectable latent phase. J Gen Virol. 1991;72(Pt 12):3035–3046. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-12-3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sivachandran N, Wang X, Frappier L. Functions of the Epstein-Barr virus EBNA1 protein in viral reactivation and lytic infection. J Virol. 2012;86(11):6146–6158. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00013-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Webster-Cyriaque J, Middeldorp J, Raab-Traub N. Hairy leukoplakia: An unusual combination of transforming and permissive Epstein-Barr virus infections. J Virol. 2000;74(16):7610–7618. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.16.7610-7618.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahsan N, Kanda T, Nagashima K, Takada K. Epstein-Barr virus transforming protein LMP1 plays a critical role in virus production. J Virol. 2005;79(7):4415–4424. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4415-4424.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hadinoto V, Shapiro M, Sun CC, Thorley-Lawson DA. The dynamics of EBV shedding implicate a central role for epithelial cells in amplifying viral output. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(7):e1000496. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang R, Gu X, Nathan CO, Hutt-Fletcher L. Laser-capture microdissection of oropharyngeal epithelium indicates restriction of Epstein-Barr virus receptor/CD21 mRNA to tonsil epithelial cells. J Oral Pathol Med. 2008;37(10):626–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00681.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun CC, Thorley-Lawson DA. Plasma cell-specific transcription factor XBP-1s binds to and transactivates the Epstein-Barr virus BZLF1 promoter. J Virol. 2007;81(24):13566–13577. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01055-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhende PM, Dickerson SJ, Sun X, Feng WH, Kenney SC. X-box-binding protein 1 activates lytic Epstein-Barr virus gene expression in combination with protein kinase D. J Virol. 2007;81(14):7363–7370. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00154-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laichalk LL, Thorley-Lawson DA. Terminal differentiation into plasma cells initiates the replicative cycle of Epstein-Barr virus in vivo. J Virol. 2005;79(2):1296–1307. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.1296-1307.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li QX, et al. Epstein-Barr virus infection and replication in a human epithelial cell system. Nature. 1992;356(6367):347–350. doi: 10.1038/356347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buettner M, et al. Lytic Epstein-Barr virus infection in epithelial cells but not in B-lymphocytes is dependent on Blimp1. J Gen Virol. 2012;93(Pt 5):1059–1064. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.038661-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson SJ, et al. X box binding protein XBP-1s transactivates the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) ORF50 promoter, linking plasma cell differentiation to KSHV reactivation from latency. J Virol. 2007;81(24):13578–13586. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01663-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson AS, Maronian N, Vieira J. Activation of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus lytic gene expression during epithelial differentiation. J Virol. 2005;79(21):13769–13777. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13769-13777.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Visalli RJ, Courtney RJ, Meyers C. Infection and replication of herpes simplex virus type 1 in an organotypic epithelial culture system. Virology. 1997;230(2):236–243. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hukkanen V, Mikola H, Nykänen M, Syrjänen S. Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection has two separate modes of spread in three-dimensional keratinocyte culture. J Gen Virol. 1999;80(Pt 8):2149–2155. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-8-2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andrei G, et al. Organotypic epithelial raft cultures as a model for evaluating compounds against alphaherpesviruses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(11):4671–4680. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.11.4671-4680.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gilligan K, Rajadurai P, Resnick L, Raab-Traub N. Epstein-Barr virus small nuclear RNAs are not expressed in permissively infected cells in AIDS-associated leukoplakia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87(22):8790–8794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.22.8790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tugizov S, et al. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-infected monocytes facilitate dissemination of EBV within the oral mucosal epithelium. J Virol. 2007;81(11):5484–5496. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00171-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walling DM, Ray AJ, Nichols JE, Flaitz CM, Nichols CM. Epstein-Barr virus infection of Langerhans cell precursors as a mechanism of oral epithelial entry, persistence, and reactivation. J Virol. 2007;81(13):7249–7268. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02754-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moody CA, Fradet-Turcotte A, Archambault J, Laimins LA. Human papillomaviruses activate caspases upon epithelial differentiation to induce viral genome amplification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(49):19541–19546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707947104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.