Abstract

Chronic anterior knee pain with a stable patella is often associated with overload and increased pressure on the lateral facet due to pathologic lateral soft-tissue restraints. “Lateral pressure in flexion” is a term describing the pathologic process of increasing contact pressure over the lateral patellar facet as knee flexion progresses. This report describes a surgical technique developed in response to lateral pressure in flexion and the shortcomings of traditional arthroscopic lateral release procedures. The technique is performed open with the knee in flexion, and the lateral release is repaired with a rotation flap of iliotibial band to close the defect and prevent patellar subluxation. The technique effectively decreases lateral patellar pressure and centers the patella correctly in the trochlear groove with minimal risk of iatrogenic patellar instability.

Anterior knee pain is one of the most common musculoskeletal complaints of young and active patients.1-3 It can be a disabling condition that limits daily functional activities because of constant pain. The pathogenesis of anterior knee pain is multifactorial, but primary contributors include instability and overload of the subchondral bone.4 However, in a subset of patients with anterior knee pain, no predisposing subluxation can be identified.5,6 Previously described as “patellar compression syndrome” or “excessive lateral pressure syndrome,” the disorder is associated with overload and increased pressure on the lateral facet due to pathologic lateral soft-tissue restraints.5,7,8 Contributing to the problem, an increased Q angle, indicative of patellofemoral malalignment, also results in greater surface contact between the lateral aspect of the patella and the lateral condyle of the femur during functional weight-bearing activities.9

As the knee is flexed, increased posterolateral compressive forces are exerted on the lateral aspect of the patella, which is consistent with the clinical observation that most patients with anterior knee pain tolerate prolonged knee flexion poorly.5,7,10 Because contact pressure over the lateral patellar facet is increased as knee flexion progresses, a more specific term to identify the pathologic process would be “lateral patellar pressure in flexion” or, more concisely put, “lateral pressure in flexion” (LPIF).

A common procedure designed to alleviate the pathologic forces on the patella in LPIF is the arthroscopic lateral retinacular release. However, there are problems with how the procedure is typically performed. The most significant complication is iatrogenic medial patellar subluxation, which can worsen the patient's knee pain and require further stabilization procedures.11-13 In addition, the traditional arthroscopic release does not extend distal enough to relieve the pressure in flexion.14 The biomechanical effects of lateral release are related to the length of the release, especially in the distal direction. Many releases are performed in knee extension (not flexion, the position of maximum contact pressure) and extend inferiorly only as far as the joint line or anterolateral inferior arthroscopic portal. Although the clinically necessary amount of release is not known with certainty, extending the release distally to the level of the tibiofemoral joint line does result in a measureable increase in patellar mobility.

The technique of the senior author (D.A.S.) was developed in response to the shortcomings of traditional arthroscopic lateral release procedures. The technique is performed open with the knee in flexion, and the lateral release is repaired with a rotation flap of iliotibial band to close the defect and prevent patellar subluxation (Video 1). The technique effectively decreases lateral patellar pressure and centers the patella correctly in the trochlear groove with minimal risk of iatrogenic patellar instability. We describe the senior author's technique in this report. Table 1 describes the pearls, indications, and complications of this technique.

Table 1.

Tips, Pearls, Indications, and Pitfalls for Treatment of LPIF

| Tips and pearls |

| The arthroscopic leg holder should be used for all portions of the case. |

| Ensure a long enough incision with adequate skin flaps to palpate appropriate landmarks. |

| Indications |

| LPIF |

| Before a tibial tubercle osteotomy to address malalignment or an increased TT-TG distance |

| Pitfalls |

| Failure to correct underlying malalignment |

| Overtensioning the repair |

TT-TG, tibial tubercle-trochlear groove.

Diagnosis

Patients with LPIF report constant anterior knee pain that is out of proportion with the physical examination findings. The pain is localized to the inferomedial patella and anteromedial joint line, the course of the medial patellotibial ligament. Symptoms include pain with prolonged knee flexion or when climbing or descending stairs. Knee extension is painful and limited. The pain is not relieved by medication, physical therapy, or bracing. Patients deny instability or crepitus.

Lateral patellar compression in flexion must be confirmed by clinical examination. Focal tenderness is present at the inferomedial patella and/or the anteromedial joint line. There is no effusion or crepitus, and the patella is stable in both flexion and extension. A maneuver to test for LPIF involves manually centering the patella in the trochlea at 45° of flexion and during active knee flexion and extension.

The involved knee is examined with the patient in the seated position. The patient with LPIF will have pain at rest and be able to reproduce pain with range of motion. Pain will limit extension and will increase as the knee approaches 90° of flexion. Next, the examiner attempts to center the patella in the trochlea by pushing the patella medially. This will usually provide immediate relief of the inferomedial patellar and anteromedial joint line pain by reducing tension on the medial patellotibial ligament. Full extension is usually possible. The patient will often smile as pain is relieved. When this maneuver decreases the patient's pain and allows a greater pain-free arc of motion, particularly in extension, LPIF is likely.

The patient is examined under anesthesia to verify the diagnosis of lateral patellar pressure in flexion. The lateral overhang sign seen during diagnostic arthroscopy has been described by Metcalf15 and other authors.16 Although mild overhang can be seen in most normal knees in full extension, overhang that includes the complete lateral facet or 50% of the surface of the patella is considered abnormal. To appreciate the lateral-sided tightness, the patellofemoral articulation is viewed from the anteromedial arthroscopic portal. The lateral retinaculum may or may not be tight in extension (Fig 1). With flexion, the inferolateral corner of the patella begins to tighten. As flexion increases, the lateral facet of the patella becomes compressed over the lateral femoral condyle. At 90° of flexion, the patella is tight over the lateral femur and not congruent with the trochlea (Fig 2). Pressure produces a concave shape to the lateral facet. These findings cannot be seen from the anterolateral or superomedial arthroscopic portal.

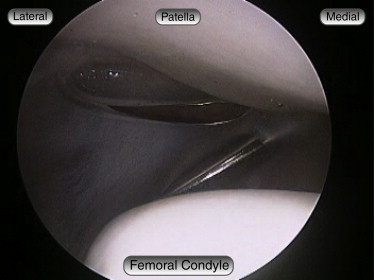

Fig 1.

Preoperative arthroscopic image of the patellofemoral compartment (right knee), viewed from the anterolateral portal, showing 2+ lateral patellar laxity at full knee extension.

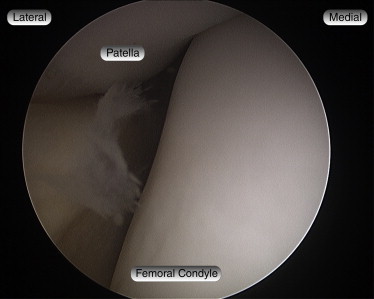

Fig 2.

Preoperative arthroscopic image of the patellofemoral compartment (right knee), viewed from the anteromedial portal, showing compression of the lateral facet of the patella over the lateral femoral condyle with the knee at 90° of flexion.

Surgical Technique

A tourniquet is placed on the thigh, and the patient is then positioned supine with the surgical limb secured in the leg holder. Diagnostic arthroscopy is routinely performed, and intra-articular findings are noted. Patellar alignment and position, the shape of the patella and the femoral trochlea, laxity on both the medial and lateral sides, and the degree of lateral-side tightness are all evaluated. Assessment of patellar stability is performed as well. These findings determine the surgical plan that is required. In addition, the patellofemoral, medial, and lateral compartments are evaluated for the presence of chondral injuries. Chondroplasty is performed as needed, and loose bodies are removed. Associated meniscal pathology is addressed as indicated.

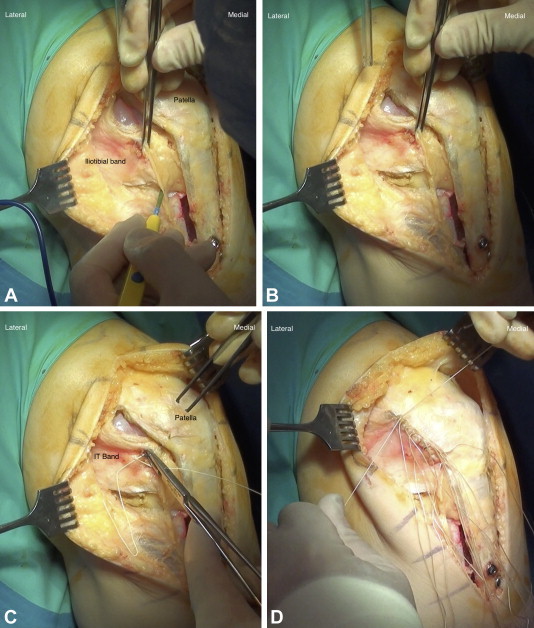

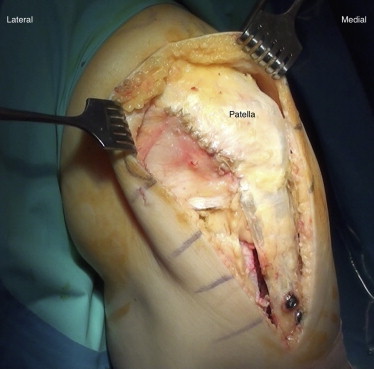

A midline skin incision is then made, and skin flaps are developed to expose the patella and patellar mechanism from the patella to the tibial tubercle. Hemostasis is obtained with electrocautery. The first step is to free the lateral side of the patellar tendon (Fig 3). The lateral retinaculum is carefully opened at the inferolateral tip of the patella. This allows the patella to move to the center of the femoral trochlea. This release is carried only far enough proximally to allow the patella to center in the trochlear groove (Fig 4). It is usually not necessary for the release to extend past the superior pole of the patella.

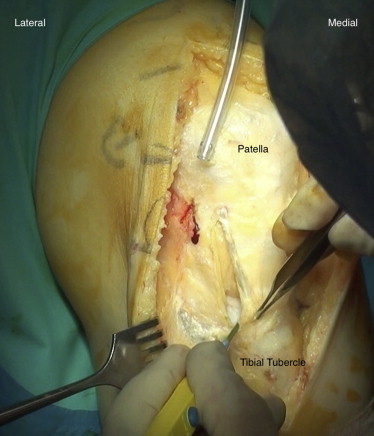

Fig 3.

Right knee after a midline skin incision. Electrocautery is used to free the lateral side of the patellar tendon.

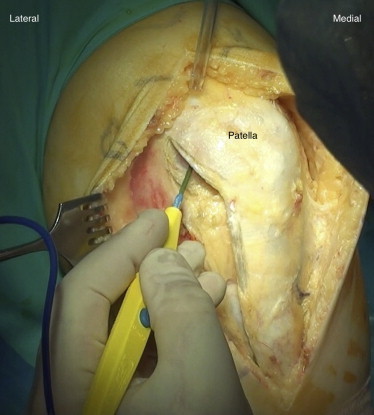

Fig 4.

The lateral retinaculum is carefully opened at the inferolateral tip of the patella and carried only far enough proximally to allow the patella to center in the trochlear groove.

If there is excessive lateralization of the tibial tubercle, a tibial tubercle osteotomy is performed to move the tubercle anteriorly and medially. If there is associated patella baja, the tubercle is recessed proximally. The patellar tendon is freed on the medial side, and the tibial tubercle is undercut with a saw to allow the tubercle to rotate medially and anteriorly and perhaps move upward or downward. The patellar tendon is attached to the tibial tubercle, and by fixing the tubercle in the desired position, the alignment and pressure on the patellar tendon can be corrected. The tubercle is then fixed in place with 2 screws (Synthes, West Chester, PA). The bony defect created on the lateral side of the tibial tubercle is filled with DBX artificial bone graft (Synthes) for the best healing.

Once the tibial tubercle is fixed in the corrected position, the lateral release is repaired by rotating a flap of adjacent iliotibial band to close the defect (Fig 5). This prevents development of lateral-side laxity and medial subluxation. If the lateral side has been seen to be excessively lax, the lateral release is extended into the vastus lateralis tendon. The tendon can be overlapped, tightening the lateral structures above the patella. The lower part of the lateral release is repaired as described earlier. The final repair is shown in Figure 6.

Fig 5.

The lateral release is repaired by rotating a flap of adjacent iliotibial band to close the defect.

Fig 6.

Right knee after lateral release, anteromedial tibial tubercle transfer, and repair of the lateral retinaculum.

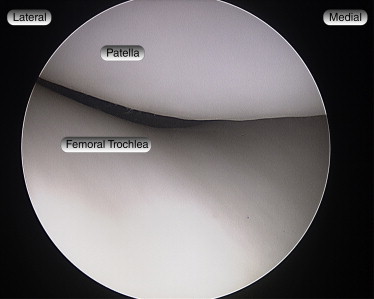

Repeat arthroscopy is performed, showing resolution of the LPIF and the patella to be centered within the femoral trochlea (Fig 7). At this point, the patella is examined for stability. Medial and lateral forces are applied to the patella in full extension and 30° of flexion to assess for medial and lateral patellar instability. If indicated, soft-tissue reconstructions are performed at this time.

Fig 7.

Postoperative arthroscopic image of the patellofemoral articulation, viewed from the lateral portal (right knee), showing a stable patella, centered in the trochlea.

Postoperatively, the patient is placed in a knee immobilizer and educated on active range-of-motion and quadriceps-strengthening exercises. The patient is encouraged to bear weight as tolerated with crutches for 2 to 4 weeks. The knee immobilizer is discontinued when the patient has gained good quadriceps control.

Discussion

To understand the pathologic process of LPIF, the normal anatomy and kinematics of the patellofemoral joint should be considered. The lateral retinaculum is a richly innervated connective tissue structure located on the lateral aspect of the knee.4 It is composed of 2 layers.17,18 The superficial layer is composed of oblique fibers of the lateral retinaculum originating from the iliotibial band and the vastus lateralis fascia and inserting into the lateral margin of the patella and the patellar tendon. The deep layer of the retinaculum consists of several structures, including the transverse and lateral patellofemoral ligaments, as well as the patellotibial band. It is oriented longitudinally with the knee extended but exerts a posterolateral force on the lateral aspect of the patella as the knee is flexed.10

Medial and lateral forces are balanced in a normal knee, and the patella glides appropriately in the femoral trochlea. Alteration in this mediolateral equilibrium can lead to pain and instability.14 The patella lies laterally with the knee extended, but in early flexion, the patella moves medially as it engages in the trochlea. As the knee continues to flex, the patella flexes and translates distally.19 By 45°, the patella is fully engaged in the trochlear groove, resulting in less dramatic changes in total contact area with greater knee flexion angles. With deeper flexion, the patella moves laterally as progressive increases in patellofemoral joint contact area have been observed from 0° to 60° of knee flexion with greater lateral facet contact area compared with the medial facet contact area at each knee flexion angle.

The lateral retinacular release was developed for peripatellar pain relief and to alleviate the pathologic lateral forces contributing to abnormal lateral pressure. The biomechanical effects of lateral release are related to the length of the release, especially in the distal direction. Arthroscopic lateral releases are performed in knee extension (not flexion, the position of maximum contact pressure) and extend inferiorly only as far as the joint line or anterolateral inferior arthroscopic portal.14 In a biomechanical comparison of lateral releases, Marumoto et al.14 found that effective release of the patellar lateral restraints, when extended down to the tibial tubercle, was significantly increased compared with a release that extends only to the level of the anterolateral inferior arthroscopic portal. Furthermore, Ostermeier et al.7 investigated the influence of lateral retinacular release and medial and lateral retinacular deficiency on patellofemoral position and retropatellar contact pressure. The lateral release extended from 20 mm proximal to the proximal aspect of the patella down to the Gerdy tubercle. Their results suggested that lateral retinacular release could decrease pressure on the lateral patellar facet in knee flexion in cases of anterior knee pain without instability but overload of the lateral facet of the patella. By performing the lateral release in flexion, the posteriorly directed force of the lateral retinaculum and iliotibial band is removed, and the patella moves in an anterior direction, alleviating the pressure on the lateral facet.

Powers et al.18 observed increases in patellar tendon tension after removal of the peripatellar retinaculum, indicating that the lateral retinaculum functions as a load-transmitting structure within the extensor mechanism. At 60° of flexion, a 9.6% increase in patellar tendon tension was observed when the retinaculum was removed. They hypothesized that, with increasing knee flexion angles, there would continue to be increased load sharing of the retinaculum. Clinically, releasing the lateral retinaculum in cases of anterior knee pain may impair its load-sharing capability and increase forces experienced by the patellar tendon. This increase in patellar tendon tension would translate into greater joint compression. By repairing the lateral release with an iliotibial band rotation flap, the load-sharing function of the lateral retinaculum is restored and patellofemoral contact pressures are normalized.

In addition to the lateral retinaculum, the position of the tibial tubercle contributes to overloading the cartilage on the lateral facet of the patella causing pain.20,21 Anteromedialization of the tibial tubercle is a surgical option for improving patellofemoral alignment.22 In cases in which there is excessive lateralization of the tibial tubercle, lateral retinacular release alone is not enough to adequately reduce pressure on the lateral facet of the patella, and a tibial tubercle osteotomy is performed. Medializing the tibial tubercle by 10 mm significantly decreases the maximum lateral pressure by 15% to 20% for intact cartilage without overloading the medial cartilage.23 The degree of anteromedialization that is performed is dependent on the amount of correction needed. Some patients have excessive lateralization and require a significant correction, whereas others require a more modest correction. The Q angle is corrected to align the bony tubercle and the patellar tendon, reducing the angle to 0°. Both over-correction and under-correction are undesirable for improving patellofemoral alignment and normalizing contact pressures.

The senior author has performed the described technique in over 150 patients with anterior knee pain. The technique has been used in cases of isolated LPIF, as well as in conjunction with stabilization procedures for patellar instability. The results have been good or excellent in 97% of patients at a mean follow-up of 6 years.

Footnotes

The authors report that they have no conflicts of interest in the authorship and publication of this article.

Supplementary Data

Diagnosis and treatment of LPIF.

References

- 1.Sanchis-Alfonso V. Springer; London: 2006. Anterior knee pain and patellar instability. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Post W.R. Anterior knee pain: Diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13:534–543. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200512000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Witvrouw E., Callaghan M.J., Stefanik J.J. Patellofemoral pain: Consensus statement from the 3rd International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat held in Vancouver, September 2013. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:411–414. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-093450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaffagnini S., Dejour D., Arendt E. Springer Verlag; Berlin: 2010. Patellofemoral pain, instability, and arthritis. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larson R.L., Cabaud H.E., Slocum D.B., James S.L., Keenan T., Hutchinson T. The patellar compression syndrome: Surgical treatment by lateral retinacular release. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1978;134:158–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fulkerson J.P. Patellofemoral pain disorders: Evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1994;2:124–132. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199403000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostermeier S., Holst M., Hurschler C., Windhagen H., Stukenborg-Colsman C. Dynamic measurement of patellofemoral kinematics and contact pressure after lateral retinacular release: An in vitro study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:547–554. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0261-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bentley G., Dowd G. Current concepts of etiology and treatment of chondromalacia patellae. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;189:209–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y.-J., Powers C.M. The dynamic quadriceps angle: A comparison of persons with and without patellofemoral pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40:A24–A25. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson R. Lateral facet syndrome of the patella. Lateral restraint analysis and use of lateral resection. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;238:148–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abhaykumar S., Craig D.M. Fascia lata sling reconstruction for recurrent medial dislocation of the patella. Knee. 1999;6:55–57. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughston J.C., Flandry F., Brinker M.R., Terry G.C., Mills J.C., III Surgical correction of medial subluxation of the patella. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:486–491. doi: 10.1177/036354659602400413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nonweiler D.E., DeLee J.C. The diagnosis and treatment of medial subluxation of the patella after lateral retinacular release. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:680–686. doi: 10.1177/036354659402200517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marumoto J.M., Jordan C., Akins R. A biomechanical comparison of lateral retinacular releases. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:151–155. doi: 10.1177/036354659502300204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Metcalf R. An arthroscopic method for lateral release of subluxating or dislocating patella. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;167:9–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dzioba R.B., Strokon A., Mulbry L. Diagnostic arthroscopy and longitudinal open lateral release: A safe and effective treatment for “chondromalacia patella.”. Arthroscopy. 1985;1:131–135. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(85)80044-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fulkerson J.P., Gossling H. Anatomy of the knee joint lateral retinaculum. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;153:183–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powers C.M., Chen Y.-J., Farrokhi S., Lee T.Q. Role of peripatellar retinaculum in transmission of forces within the extensor mechanism. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:2042–2048. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salsich G.B., Ward S.R., Terk M.R., Powers C.M. In vivo assessment of patellofemoral joint contact area in individuals who are pain free. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;417:277–284. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000093024.56370.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramappa A.J., Apreleva M., Harrold F.R., Fitzgibbons P.G., Wilson D.R., Gill T.J. The effects of medialization and anteromedialization of the tibial tubercle on patellofemoral mechanics and kinematics. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:749–756. doi: 10.1177/0363546505283460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elias J.J., Kilambi S., Goerke D.R., Cosgarea A.J. Improving vastus medialis obliquus function reduces pressure applied to lateral patellofemoral cartilage. J Orthop Res. 2009;27:578–583. doi: 10.1002/jor.20791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fulkerson J.P., Becker G.J., Meaney J.A., Miranda M., Folcik M.A. Anteromedial tibial tubercle transfer without bone graft. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18:490–497. doi: 10.1177/036354659001800508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saranathan A., Kirkpatrick M.S., Mani S. The effect of tibial tuberosity realignment procedures on the patellofemoral pressure distribution. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;20:2054–2061. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1802-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Diagnosis and treatment of LPIF.