Abstract

Objective

To assess community pharmacists’ knowledge, behaviors and experiences relating to Adverse Drug Reaction (ADR) reporting in Saudi Arabia.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted using a validated self-administered questionnaire. A convenience sample of 147 community pharmacists working in community pharmacies in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Results

The questionnaire was distributed to 147 pharmacists, of whom 104 responded to the survey, a 70.7% response rate. The mean age of participants was 29 years. The majority (n = 101, 98.1%) had graduated with a bachelorette degree and worked in chain pharmacies (n = 68, 66.7%). Only 23 (22.1%) said they were familiar with the ADR reporting process, and only 21 (20.2%) knew that pharmacists can submit ADR reports online. The majority of the participants (n = 90, 86.5%) had never reported ADRs. Reasons for not reporting ADRs most importantly included lack of awareness about the method of reporting (n = 22, 45.9%), misconception that reporting ADRs is the duty of physician and hospital pharmacist (n = 8, 16.6%) and ADRs in community pharmacies are simple and should not be reported (n = 8, 16.6%). The most common approach perceived by community pharmacists for managing patients suffering from ADRs was to refer him/her to a physician (n = 80, 76.9%).

Conclusion

The majority of community pharmacists in Riyadh have poor knowledge of the ADR reporting process. Pharmacovigilance authorities should take necessary steps to urgently design interventional programs in order to increase the knowledge and awareness of pharmacists regarding the ADR reporting process.

Keywords: Community pharmacists, Knowledge, Misconception, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

1. Introduction

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are the most common cause of morbidity, mortality and poor economic outcomes (Pirmohamed et al., 2004; Patel et al., 2007). Therefore, post-marketing surveillance is very important for monitoring the risk and benefits of pharmaceutical products after they have been released on the market (Edlavitch, 1988). As an initiative to encourage and monitor ADR reporting, the Saudi Food and Drug Authority (SFDA) has recently established a National Pharmacovigilance Center that has made online reporting forms and papers forms available to encourage ADR reporting by public and healthcare professionals (National Pharmacovigilance Centre, 2012).

Traditionally, the role of the pharmacist was limited to the preparation and dispensing of drugs prescribed by the physician. Recently, the role of the pharmacist has expanded to other aspects of patient care. These roles include reporting ADRs, improving patients’ health, and economic outcomes (Hepler and Strand, 1990; Manley and Carroll, 2002; Kane et al., 2003). Pharmacists can play an important role in ADR reporting and pharmacovigilance by increasing the number as well as the quality of submitted reports (Kees et al., 2004; Gedde-Dahl et al., 2007). However, in many countries the knowledge of pharmacists about pharmacovigilance and ADR reporting is poor and the rate of reporting is low (Oreagba et al., 2011; Su et al., 2010; Vessal et al., 2009; Toklu and Uysal, 2008; Lee et al., 1994). The scenario in Saudi Arabia is the same as in other countries. A recent Saudi study reported lower awareness of the ADR reporting program and a poor reporting rate (13.2%). Barriers to ADR reporting identified by this study included, most commonly, a lack of knowledge about where and how to report ADRs, and unavailability of ADR reporting forms (Bawazir, 2006).

Assessing the knowledge, behaviors and experiences of community pharmacists relating to spontaneous reporting of ADRs is very important. When pharmacists have sufficient knowledge of the ADR reporting process, they can improve other healthcare professionals’ knowledge about ADR reporting (Khalili et al., 2012). In Saudi Arabia, studies conducted to assess pharmacists’ knowledge, behaviors and experiences relating to ADR reporting are limited (Bawazir, 2006) and were conducted before the establishment of the National Pharmacovigilance Centre. Therefore, the aims of the current study were to assess the knowledge, behaviors and experiences of community pharmacists regarding the reporting of ADRs.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and setting

This was a cross-sectional study conducted among a convenience sample of community pharmacists from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

2.2. Study tool

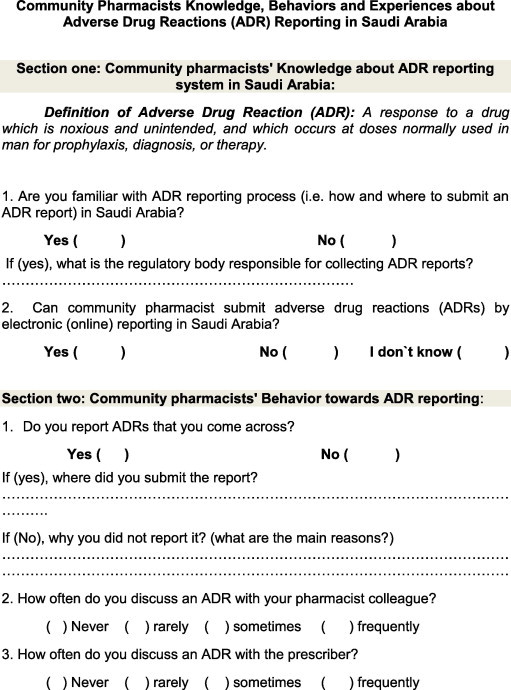

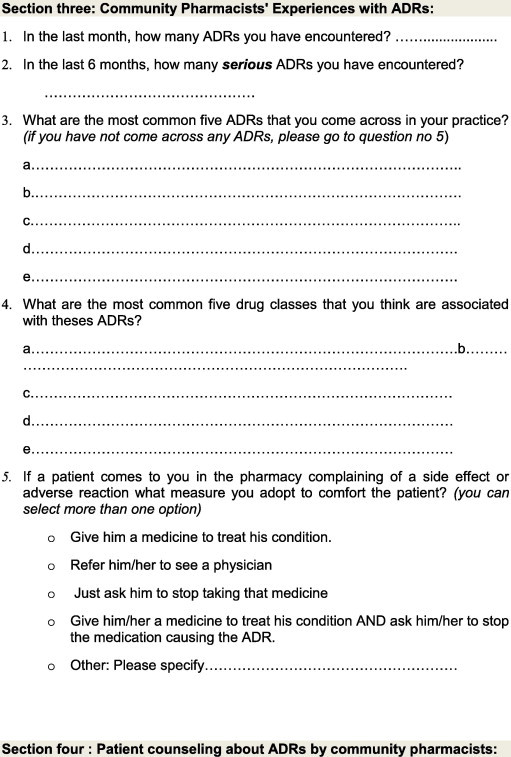

The questionnaire comprised 21 questions (Appendix 1). The first part consisted of two questions, one closed-ended and one open-ended. This part was designed to understand community pharmacists’ familiarity with the ADR reporting process. The second part consisted of four questions, two open-ended and two close-ended, which used a four-point scale ranging from “never” to “frequently”. The third part of the questionnaire consisted of four open-ended questions and one close-ended question designed to measure community pharmacists’ experiences with ADRs. In the fourth part of the survey, patients’ knowledge regarding counseling about ADRs was measured with a five-point scale ranging from “never” to “frequently”. Three experts in the field were asked to provide comments regarding the questionnaire conciseness, clarity and relevance. Their comments were taken into consideration and the final survey was prepared. The questionnaire language was English.

2.3. Data collection and ethical consideration

A pharmacy student visited each pharmacy and invited community pharmacists to participate in the study after explaining the aims of the study. A written consent form was obtained from each participant who wished to participate in the study. Participants were told that all information provided was completely confidential and the results would be presented anonymously.

2.4. Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data (frequency and percentages; mean ± standard deviation). Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) Software for Windows, (version 20.0).

3. Results

The survey was distributed to 147 pharmacists; however only 104 surveys were collected, giving a response rate of 70.7%. The mean age of the participants was 29 ± 3.9 years. Community pharmacists in this study were predominantly graduated from Egypt (n = 80, 79.4%) and most (n = 101, 98.1%) had completed their bachelorette degree (Table 1). The majority of participants were employed in chain community pharmacies (n = 68, 66.7%).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of 104 community pharmacists.

| Frequency | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (Mean) | 29 | |

| Number of years of experience as a community pharmacist (Mean ± SD) | 3.4 ± 2.4 | |

| Number of prescriptions dispensed per week (Median) | 70 | |

| Community pharmacist qualification | ||

| Bachelor | 101 | 98.1 |

| Diploma | 1 | 0.9 |

| PhD | 1 | 0.9 |

| Category of community pharmacy | ||

| Independent pharmacy | 14 | 13.7 |

| Chain Pharmacy | 68 | 66.7 |

| Hospital pharmacy | 20 | 19.6 |

| Country of graduation | ||

| Egypt | 80 | 79.4 |

| Yemen | 10 | 9.9 |

| Syria | 5 | 4.9 |

| Sudan | 4 | 3.9 |

| Jordan | 1 | 0.9 |

| India | 1 | 0.9 |

3.1. Community pharmacists’ knowledge about the ADR reporting system in Saudi Arabia

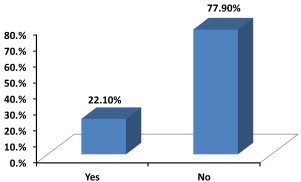

Only 23 (22%) of the participants said that they were familiar with the ADR reporting process (Fig. 1). Those who said that they were aware of such reporting were asked if they knew the regulatory body to which ADRs should be reported. Answers were provided by 18 participants which included the Ministry of Health (MOH) (n = 7), SFDA (n = 6), government hospitals (n = 1), hospital drug information centre (n = 2) and unspecified internet websites (n = 2). However, about 80% of the pharmacists did not know that they could report ADRs through an online system. The responses to knowledge items are illustrated in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Are you familiar with ADR reporting process (i.e. how and where to submit ADR reports) in Saudi Arabia?

Table 2.

Community Pharmacist Knowledge about ADR patient counseling.

| Question | Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Frequently | Always |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How often do you ask your patient if he/she is allergic to medications | 2 (1.9%) | 6 (5.8%) | 24 (23.1%) | 26 (25%) | 46 (44.2%) |

| How often do you ask a female if she is pregnant when dispensing teratogenic/abortive medication | 0 | 1 (1 %) | 4 (4.8%) | 24 (23.1%) | 75 (72.1%) |

| How often do you ask a female if she is lactating when dispensing medication that is excreted in the mother milk and might harm the baby | 0 | 5 (4.8%) | 1 (1%) | 27 (26%) | 71 (68.3%) |

| How often do you counsel your patients about ADRs that they may experience from their medication? | 1 (1%) | 6 (5.8%) | 19 (18.3%) | 26 (25%) | 52 (50%) |

3.2. Community pharmacists’ behavior toward ADR reporting

Only 13 (12.5%) of the participants said they reported ADRs when they occurred. The majority of participants (n = 91, 87.5%) did not report ADRs. Of these 91 participants, 48 provided reasons for not reporting ADRs; 22 (45.9%) said that they were not aware of the method of reporting, 8 (16.6%) said that ADR reporting was the duty of physicians and hospital pharmacists, 8 (16.6%) said that most ADRs in community pharmacy are minor and should not be reported, 4 (8.3%) said that all ADRs are familiar and already reported in the medication leaflet, 3 (6.3%) said they did not have a computer or internet access in the pharmacy to report ADRs, and 3 (6.3%) said they did not report ADRs because of workload. Table 3 summarizes community pharmacist’s responses to behavior items.

Table 3.

Community pharmacist behavior toward ADR reporting.

| Item | Never | Rarely | sometimes | Frequently |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How often do you discuss an ADR with your pharmacist colleague? | 5 (4.8%) | 14 (13.5%) | 47 (45.2%) | 38 (36.5%) |

| How often do you discuss an ADR with the prescriber? | 25 (24%) | 21 (20%) | 31 (30%) | 27 (26%) |

3.3. Community pharmacists’ experiences with ADRs

Table 2 summarizes the experiences and actions taken by pharmacists when a patient with an ADR seeks advice from them (Table 4). The most common approach perceived by community pharmacist to manage patients suffering from ADRs was to refer him/her to a physician. The most common side effects seen during the participants’ daily practice were diarrhea (n = 14, 13%), allergy (n = 8, 7.5%), and headache (n = 6, 5.7%). The most common drug classes believed to be associated with ADRs were antibiotics (n = 22, 27.5%), analgesics (n = 11, 13.7%), and antihypertensives (n = 5, 6.2%).

Table 4.

Community pharmacist experience with ADR reporting.

| Item | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| If a patient comes to you in the pharmacy complaining of a side effect or adverse reaction what measure do you adopt to comfort the patient? | ||

| Give him a medicine to treat his condition | 38 (36.5%) | 66 (63.5%) |

| Refer him/her to see a physician | 80 (76.9%) | 24 (23.1%) |

| Just ask him to stop taking that medicine | 39 (37.5%) | 65 (62.5%) |

| Give him/her a medicine to treat the condition and ask him/her to stop the medication causing the ADRs | 18 (17.3%) | 86 (82.7%) |

4. Discussion

We performed a cross-sectional assessment of knowledge, experience and behaviors of community pharmacists about the reporting of ADRs in Saudi Arabia. Our results have revealed that pharmacists have poor knowledge of ADR reporting, few pharmacists have reported ADRs, and the majority are not aware of the process of ADR reporting. Reasons for not reporting ADRs mainly included lack of awareness about the method of reporting, disclaiming responsibility for ADR reporting, and the belief that most ADRs in community pharmacies are minor and should not be reported.

Several previous studies have documented a lack of knowledge in community pharmacists about ADR reporting similar to our findings. The rate of ADR reporting by pharmacists in various countries has been reported to vary from 3% to 14.7% (Oreagba et al., 2011; Su et al., 2010; Vessal et al., 2009; Toklu and Uysal, 2008; Lee et al., 1994). A previous study from Saudi Arabia reported a lower level of awareness about the process of ADR reporting compared to our findings (13.2% vs. 22%) Bawazir, 2006. Regarding knowledge about where ADRs can be submitted, most pharmacists claimed that they had submitted ADRs to the Ministry of Health and SFDA. In the study by Bawazir, 2006, the majority of pharmacists surveyed claimed that they had submitted ADRs to both the pharmaceutical company and the Ministry of Health. One of the most serious barriers to reporting ADRs identified in this study is that pharmacists do not take responsibility for reporting. Previous studies had shown that pharmacists can make a major positive contribution to the quality and number of ADRs reported (Kees et al., 2004; Gedde-Dahl et al., 2007; Khalili et al., 2012).

The current study has several limitations. The survey included community pharmacists’ from one city in Saudi Arabia which limits its generalizability. In the current study, some pharmacists indicated that they did not have internet connection in their pharmacy; this may have partially contributed to the underreporting of ADRs. Also, community pharmacists’ heavy workload might have limited the response rate.

Although there is a reporting system in Saudi Arabia that deals with ADRs in both paper and electronic format, the majority of community pharmacists are unaware of where and how to report ADRs. Community pharmacists believe that ADR reporting is the responsibility of physicians and hospital pharmacists. A computer and access to an internet connection should be available in all community pharmacies to help the pharmacist report ADRs online. Pharmacovigilance authorities in Saudi Arabia should utilize interventional programs that have been shown to increase the knowledge and awareness of ADR reporting in other countries (Gedde-Dahl et al., 2007; Granas et al., 2007; Sevene et al., 2008; Irujo et al., 2007). Involvement of pharmacy students in community pharmacy internships may increase the awareness of future pharmacists regarding ADR detection and reporting (Christensen et al., 2011). In addition, training programs in pharmacovigilance and spontaneous reporting may also help to minimize the rate of underreporting.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Appendix 1.

References

- Bawazir S.A. Attitude of community pharmacists in Saudi Arabia towards adverse drug reaction reporting. Saudi Pharm. J. 2006;14:5–83. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen S.T., Søndergaard B., Honoré P.H., Bjerrum O.J. Pharmacy student driven detection of adverse drug reactions in the community pharmacy setting. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2011;20:399–404. doi: 10.1002/pds.2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlavitch S.A. Postmarketing surveillance methodologies. Drug Intell. Clin. Pharm. 1988;22:68–78. doi: 10.1177/106002808802200117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gedde-Dahl A., Harg P., Stenberg-Nilsen H., Buajordet M., Granas A.G., Horn A.M. Characteristics and quality of adverse drug reaction reports by pharmacists in Norway. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2007;16:999–1005. doi: 10.1002/pds.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granas A.G., Buajordet M., Stenberg-Nilsen H., Harg P., Horn A.M. Pharmacists’ attitudes towards the reporting of suspected adverse drug reactions in Norway. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2007;16:429–434. doi: 10.1002/pds.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepler C., Strand L. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am. J. Hosp. Pharm. 1990;47:533–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irujo M., Beitia G., Bes-Rastrollo M., Figueiras A., Hernández-Díaz S., Lasheras B. Factors that influence under-reporting of suspected adverse drug reactions among community pharmacists in a Spanish region. Drug Saf. 2007;30:1073–1082. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200730110-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane S., Weber R., Dasta J. The impact of critical care pharmacists on enhancing patient outcomes. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:691–698. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1705-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kees V.G., Olsson S., Couper M., de Jong-van den Berg L. Pharmacists’ role in reporting adverse drug reactions in an international perspective. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2004;13:457–464. doi: 10.1002/pds.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalili H., Mohebbi N., Hendoiee N., Keshtkar A.A., Dashti-Khavidaki S. Improvement of knowledge, attitude and perception of healthcare workers about ADR, a pre- and post-clinical pharmacists’ interventional study. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000367. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.K., Chan T.Y., Raymond K., Critchley J.A. Pharmacists’ attitudes toward adverse drug reaction reporting in Hong Kong. Ann. Pharmacother. 1994;28:1400–1403. doi: 10.1177/106002809402801213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley H.J., Carroll C.A. The clinical and economic impact of pharmaceutical care in end-stage renal disease patients. Semin. Dial. 2002;15(1):45–49. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-139x.2002.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Pharmacovigilance Centre. http://www.sfda.gov.sa/En/Drug/Topics/Organogram/Pharmacovigilance/. (Accessed December 2012).

- Oreagba I.A., Ogunleye O.J., Olayemi S.O. The knowledge, perceptions and practice of pharmacovigilance amongst community pharmacists in Lagos state, south west Nigeria. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2011;20:30–35. doi: 10.1002/pds.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel H., Bell D., Molokhia M., Srishanmuganathan J., Patel M., Car J., Majeed A. Trends in hospital admissions for adverse drug reactions in England: analysis of national hospital episode statistics 1998–2005. BMC Clin. Pharmacol. 2007;7:9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6904-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirmohamed M., James S., Meakin S., Green C., Scott A., Walley T., Farrar K., Park B., Alasdair B. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18,820 patients. BMJ. 2004;329:15. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7456.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevene E., Mariano A., Mehta U., Machai M., Dodoo A., Vilardell D., Patel S., Barnes K., Carné X. Spontaneous adverse drug reaction reporting in rural districts of Mozambique. Drug Saf. 2008;31:867–876. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200831100-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su C., Ji H., Su Y. Hospital pharmacists’ knowledge and opinions regarding adverse drug reaction reporting in Northern China. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2010;19:217–222. doi: 10.1002/pds.1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toklu H.Z., Uysal M.K. The knowledge and attitude of the Turkish community pharmacists toward pharmacovigilance in the Kadikoy district of Istanbul. Pharm. World Sci. 2008;30:556–562. doi: 10.1007/s11096-008-9209-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vessal G., Mardani Z., Mollai M. Knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of pharmacists to adverse drug reaction reporting in Iran. Pharm. World Sci. 2009;31:183–187. doi: 10.1007/s11096-008-9276-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]