Abstract

Objective

Medication use during pregnancy is a major concern for most women. The aim of the present study was to assess medication use, knowledge and beliefs about medications among pregnant women in Saudi Arabia.

Methods

More than 760 pregnant women, attending the obstetric clinic, filled a semi-structured questionnaire. Data were collected about their sociodemographic background, medication use during pregnancy, medication/pregnancy risk awareness, sources of drug information and beliefs about medications.

Results

Most women had a positive attitude toward medications in general but they believed pregnant women should be more cautious regarding drug-use during pregnancy. A significant association was found between participants’ education and occupation, and beliefs about medications. In this context, well educated women and those working in a health-related career demonstrated more correct beliefs about medications. Women with health-related occupations were more knowledgeable about the life saving effect of drugs on unborn children. Women indicated inadequate provision of drug-related information from physician and pharmacist; they rely on medication pamphlet to get such information. The most frequently used drugs were paracetamol and vitamins (13.2%). Most pregnant women (59.2%) were able to identify drugs to-be avoided in pregnancy that agreed roughly with FDA categories with 23 hits out of 32. They indicated that newborn anomalies (6.5%) were not attributed to drug-use during pregnancy.

Conclusion

During pregnancy, women were more conservative and skeptic toward medication, health-care professionals should be aware of such attitudes when advising pregnant women to take medication.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Beliefs about medication, Drug information, Saudi Arabia, Women

1. Introduction

Pregnancy is a special physiological state where medication intake presents a challenge and a concern due to altered drug pharmacokinetics and drug crossing the placenta possibly causing harm to the foetus (Banhidy et al., 2005). Medication treatment in pregnancy cannot be totally avoided since some pregnant women may have chronic pathological conditions that require continuous or interrupted treatment (e.g. asthma, epilepsy, and hypertension). Also during pregnancy new medical conditions can develop and old ones can worsen (e.g. migraine, headache, hyperacidity, nausea and vomiting) requiring drug therapy (Deborah et al., 2005). So it becomes a major concern for pregnant women to take medication whether prescription, over-the counter, or herbal medication. Since the thalidomide era, there has been great awareness about harmful effects of medications on the unborn child (Kacew, 1994; Melton, 1995). It has been documented that congenital abnormalities caused by human teratogenic drugs account for less than 1% of total congenital abnormalities (Sachdeva et al., 2009). Hence in 1979, Food and Drug Administration developed a system that determines the teratogenic risk of drugs by considering the quality of data from animal and human studies (Sachdeva et al., 2009). FDA classifies various drugs used in pregnancy into five categories, categories A, B, C, D and X. Category A is considered the safest category and category X is absolutely contraindicated in pregnancy (FDA, 2005). This provides therapeutic guidance for the clinician.

Beliefs about medication have been shown to strongly associate with patients adherence to medication (Gatti et al., 2009). The Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ) was developed in an attempt to express people’s perceptions about medicines (Horne et al., 1999). The BMQ-General scale has been extensively used to assess opinions toward medicines among people with no common condition or treatment (Horne and Weinman, 1999; Mardby et al., 2009; Porteous et al., 2010). Progressively, various BMQs-Specific have been developed and used for each individual pathological condition. For example, one BMQ was developed for patients with rheumatoid arthritis (Neame and Hammond, 2005), another one was used to predict refill adherence to inhaled corticosteroids (Menckeberg et al., 2008) while a recent Swedish study used a BMQ for assessing the impact of the beliefs about medicines and personality traits on adherence to treatment with asthma medications (Emilsson et al., 2011).

Few attempts were made to identify the sociodemographic characteristics of pregnant women correlated with attitudes and beliefs regarding medications (Nordeng et al., 2010a,b; Rizk et al., 1993; Skouteris et al., 2008). Among these, education, socioeconomic level, age, occupation, lifestyle, common beliefs as well as severity of illness were reported. A patient’s knowledge and capacity to get knowledge are important in the development of beliefs (DiMatteo et al., 2007; Veazie and Cai, 2007). Although some pregnant women may have the sufficient knowledge about high-risk medication in pregnancy, there is a “general fear” from medications (Nordeng et al., 2010b). The hesitation in medication use by pregnant women might result in serious consequences which include but are not limited to: termination of a wanted pregnancy (Einarson, 2007), reluctance to drug-use for nausea and vomiting (Baggley et al., 2004), preference of herbal medications (Glover et al., 2003), non-compliance to prescriber’s medication (Ito et al., 1993; Williams et al., 2002) and inclination toward OTC drugs (Erebara et al., 2008) and other self-medication methods (Holst et al., 2009). Medication use in pregnancy has been studied in different communities. Norwegian women demonstrated a positive attitude toward medication in general, but a more restrictive one during pregnancy (Nordeng et al., 2010a). In Serbia, women had higher drug exposure during (34.7%) than before pregnancy (29.9%) (Odalovic et al., 2012) and less self-medication with over the counter drugs. In Tanzania, most (66.5%) pregnant women reported that they hesitated to take medications without consulting their physicians, and few (31.5%) were aware of certain drugs that are contraindicated during pregnancy (Kamuhabwa and Jalal, 2011).

To the best of our knowledge, no attempts were made to spot the characteristics of pregnant women in the Saudi Community that influence the medication intake. Such study is highly warranted since patients are believed to make deliberate decisions regarding their drug taking, based on their beliefs about the illness and its treatment. The objective of this study was to assess use, knowledge, risk-awareness and beliefs about medications of pregnant women in Saudi Arabia and to investigate whether women’s beliefs during pregnancy were associated with socio-demographic properties and their personal medication use during pregnancy.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study design and population

This was a cross-sectional study in which an anonymous self-completed questionnaire was distributed to more than 760 pregnant women attending obstetric clinics in two tertiary hospitals in Taif, KSA. The study was conducted during a 16-week study period from December 2011 to April 2012.

Inclusion criterion was women who are currently pregnant. A written informed consent was obtained before participation in the study. The study conformed to the ethical principles of the National Committee of Medical and Bioethics, King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST), Riyadh, KSA.

2.2. Data collection

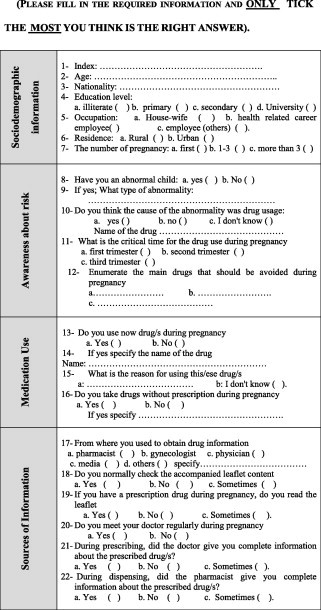

Data were collected by means of a semi-structured (Appendix I) questionnaire composed of 22 + 16-item developed in Arabic language. Midwives provided aid to illiterate women in explaining and filling the questionnaire. The questionnaire was modified from a previously validated survey (Horne et al., 1999; Nordeng et al., 2010a). Pregnant women were asked to answer 22 questions that assess their sociodemographic characteristics (Q1–7), awareness of risk (Q8–Q12), current medication use (Q13–Q16) and sources of drug information (Q17–Q22). Moreover, their beliefs and attitudes regarding medication use in general (statements M1–M7) and in pregnancy (statements S1–S9) were evaluated as described by Horne et al. (1999) and by Nordeng et al., (2010a) to which they should indicate if they agree, disagree, or are uncertain.

2.3. Data analysis

The BMQ statements were trichotomized (agree, disagree, or uncertain). Chi-square test was used to test for differences in proportions between answers given to each of the 16 statements, the women’s sociodemographic background, and use of medication during pregnancy. SPSS version 16.0.1 was used.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the study population

During the 16 weeks of the survey, 760 pregnant women completed the questionnaire. Participants were similar to the population of pregnant women in Taif city in KSA with respect to geographic area, age, parity, and maternal status, but higher % of those who had completed university-level education (Table 1). The percentage of women with a college or university degree who answered the questionnaire was 67.1%, compared to 32.9% secondary and pre-secondary education. There was also great % for unemployed women, where 81.6% of the participants are housewives; while 9.2% of the women were employed in a non-health-related sector, 7.9% were employed in the health-care sector and 1.3% were students. Interestingly, most of the pregnant women participating in the study (85%) were multiparous (with two or more pregnancies) while primaparous women constitute about 15%.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics (n = 760).

| Characteristics | Number of pregnant women (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 20–30 | 260 (34.2) |

| 30–40 | 340 (44.7) |

| 40–50 | 160 (21.1) |

| Nationality | |

| Saudi | 540 (71.1) |

| Egyptian | 60 (7.9) |

| Sudanese | 30 (3.9) |

| Jordanian | 30 (3.9) |

| Syrian | 50 (6.6) |

| Indian | 10 (1.3) |

| Pakistanis | 20 (2.6) |

| Others | 20 (2.6) |

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 60 (7.9) |

| Primary | 50 (6.6) |

| Secondary | 140 (18.4) |

| University | 500 (65.8) |

| Postgraduate | 10 (1.3) |

| Occupation | |

| House-wife | 620 (81.6) |

| Student | 10 (1.3) |

| Health-related career employee | 60 (7.9) |

| Other employee | 70 (9.2) |

| Residence | |

| Rural | 750 |

| Urban | 10 |

| Parity | |

| First-time pregnancy | 120 (15.8) |

| 1–3 previous children | 220 (28.9) |

| More than 3 previous children | 420 (55.3) |

| Previous abnormal children | |

| Yes | 50 (6.6) |

| No | 710 (93.4) |

3.2. Medication use

About 40% of the pregnant women reported having used medications (either herbal or chemical drugs) during pregnancy. The most commonly used drugs were paracetamol (acetaminophen) and vitamins (13.2% each), antibiotics (2.6%), herbal remedies (4.6%), and medications to treat nausea and vomiting in pregnancy (2.6%), NSAIDs, antihistaminics and heartburn medications (1.3%). Interestingly 59.9% of the women mentioned that they have chosen not to take medication during pregnancy (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Medication Use during pregnancy (n = 760).

| Drug | Number of pregnant women (%) |

|---|---|

| Paracetamol | 100 (13.2) |

| Antacid | 10 (1.3) |

| NSAIDs | 10 (1.3) |

| Antibiotics | 20 (2.6) |

| Antihistaminics | 10 (1.3) |

| Drugs for nausea and vomiting | 20 (2.6) |

| Vitamins | 100 (13.2) |

| Herbs | 35 (4.6) |

| No medication | 455 (59.9) |

NSAIDs non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

3.3. Beliefs about medications

Women’s opinions about medications are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Pregnant women’s beliefs about medications in general (n = 760).

| Statement | Agree n (%) | Disagree n (%) | Uncertain n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | Doctors prescribe too many medicines | 440 (57.9) | 170 (22.4) | 150 (19.7) |

| M2 | Most medicines are addictives | 200 (26.3) | 440 (57.9) | 120 (15.8) |

| M3 | Natural remedies are safer than medicines | 340 (44.7) | 220 (28.9) | 200 (26.3) |

| M4 | Medicines do more harm than good | 220 (28.9) | 350 (46.1) | 190 (25) |

| M5 | All medicines are poisons | 200 (26.3) | 370 (48.7) | 190 (25) |

| M6 | Doctors place too much trust on medicines | 510 (67.1) | 120 (15.8) | 130 (17.1) |

| M7 | If doctor had more time with patients; he would prescribe fewer medicines | 400 (52.6) | 230 (30.3) | 130 (17.1) |

Table 4.

Pregnant women’s beliefs about medication use during current pregnancy (n = 760).

| Statement | Agree n (%) | Disagree n (%) | Uncertain n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | All medicines can be harmful to the fetus | 450 (59.2) | 170 (22.4) | 140 (18.4) |

| S2 | Even if I’m ill and if not pregnant would have taken medicines, I believe it’s better for the fetus that I refrain from using medicines during pregnancy | 600 (78.9) | 80 (10.5) | 80 (10.5) |

| S3 | I have a higher threshold for using medicines when I’m pregnant than when I’m not pregnant | 670 (88.2) | 50 (6.6) | 40 (4.3) |

| S4 | Thanks to treatment with medicines during pregnancy lives of many unborn children are saved each year | 350 (46.1) | 250 (32.9) | 160 (21.1) |

| S5 | It is better for the fetus that I use medicines and get well than to have untreated illness during pregnancy | 340 (44.7) | 240 (31.6) | 180 (23.7) |

| S6 | Doctors prescribe too many medicines to pregnant women | 150 (19.7) | 470 (61.8) | 140 (18.4) |

| S7 | Natural remedies can generally be used by pregnant women | 160 (21.1) | 450 (59.2) | 150 (19.7) |

| S8 | Pregnant women should preferable(y) use natural remedies during pregnancy | 190 (25) | 370 (48.7) | 200 (26.3) |

| S9 | Pregnant women should not use natural remedies without the advice of doctor | 570 (75) | 90 (11.8) | 100 (13.2) |

Generally, most women believed that physicians prescribe too many medicines (M1; 57.9%); that they place too much trust in drugs (M6; 67.1%) while about half (52.6%) believed that by taking more time with patients; the doctor would prescribe fewer medicines (M7). The majority (78.9%) of pregnant women agreed that it would be better for the foetus if they cease medications (S2) and (88.2%) supported the statement about being more careful in using medications during pregnancy (S3). Most (75%) women believed a physician’s consent should be obtained before using natural remedies during pregnancy (S9).

3.3.1. Factors related to medication-use attitudes and beliefs of pregnant women

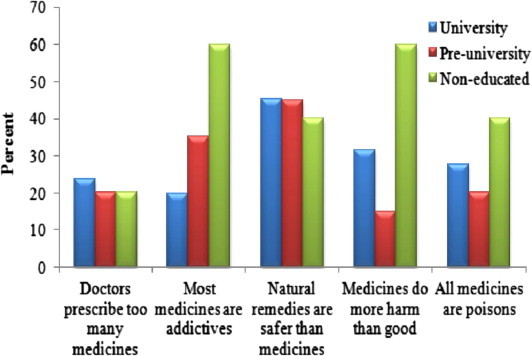

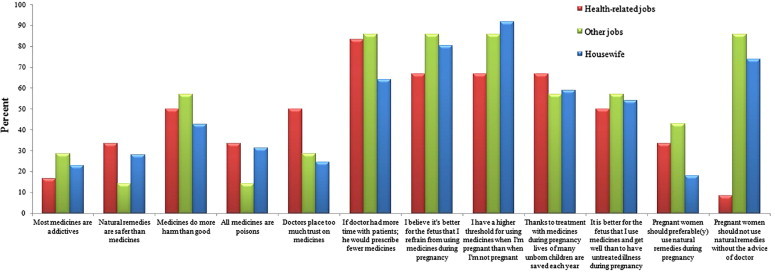

Among the different social and demographic properties, the education level and type of employment were significantly associated with the pregnant women’s opinion about drugs (Figs. 1–3).

Figure 1.

Percentage of women agreeing to general statements about medications according to the women’s education. After Chi-square test was applied, only statements where education level was significantly associated with agreement are shown. Non-educated; Pre-university = primary and secondary school; University = college or university degree.

Figure 2.

Percentage of women agreeing to general statements about medications according to the women’s occupation. After Chi-square test was applied, only statements where education level was significantly associated with agreement are shown. Non-educated; Pre-university = primary and secondary school; University = college or university degree.

Figure 3.

Percentage of women agreeing to various statements according to the women’s occupation. After Chi-square test was applied, only statements where education level was significantly associated with agreement are shown.

Regarding education, Fig. 1 reveals that pregnant women with a lower education level agreed more often than those with a higher education level that medications did more harm than good (M4) and were addictive (M2) and poisonous (M5). From Fig. 2, it is obvious that non educated women and those with a lower education were more skeptical toward drugs (S1) and think that physicians prescribe too much (S6) although they think that drugs may save their fetus in life-threatening conditions (S4) than women with a higher education. Non-educated pregnant women were more confident toward the use of natural and/or herbal remedies during pregnancy (statements S7, S8) and they believe that they need not consult their doctor before taking natural remedies (S9).

For 12 of the 16 statements, there was a significant correlation between occupation and agreement to various statements in BMQ (Fig. 3). Women in health-related occupations were in general encouraging medication-use (M2–M7) and more skeptical about herbal remedies in general (M3) and during pregnancy (S9). They also agreed more often than other women that an untreated illness could be more harmful during pregnancy than the medication itself (S5). Housewives and those who do not work in health-related job believe that they need not check with their doctor before taking natural remedies (S9).

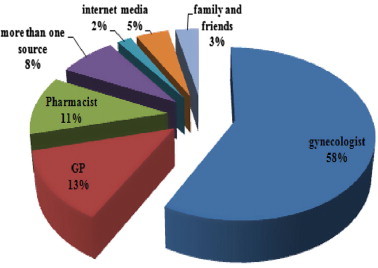

3.4. Medication-related information sources

As shown in Fig. 4, the primary information sources of drugs during pregnancy were their gynecologist (58.1%) then general practitioner (GP; 13%) and pharmacist (11%). The media, family and friends as well as the internet collectively contribute by 10% to expecting women’s information about drugs in response to Q17.

Figure 4.

Information sources on medication during current pregnancy (n = 760).

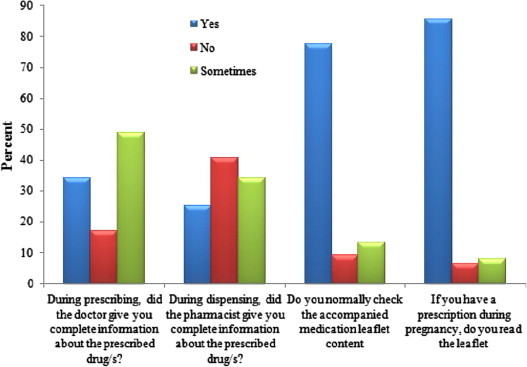

In response to Q21, pregnant women (65%) indicated that the physicians either not provide them (15%) or sometimes provide (50%) them with information about medication while prescribing (Fig. 5) although all of them (99.8%) were meeting regularly with their doctors (Q20). Surprisingly, the majority of women >40% reported not receiving information from the pharmacist during dispensing the prescribed drug (Q22). The data revealed that there was scarcity of information about drugs where 78% of women reported reading the medication leaflet in normal state (Q18) and further higher percent (86%) in pregnancy state (Q19).

Figure 5.

Sources of drug-related information as indicated by pregnant women (n = 760).

3.5. Awareness about risk

Regarding the awareness of participants during pregnancy, all pregnant women—except one—indicated that the critical time for the drug use during pregnancy is the first trimester (Q11). In response to Q8, few pregnant women (5.6%) mentioned having a previous abnormal child. They mentioned that the congenital abnormality was visual, mental or physical (in response to Q9). Nevertheless, the majority of these women (40 out of 50) did not consider this to be attributed to drug use in pregnancy (Q10).

The Food and Drug Administration system developed in 1979 for the teratogenic risk of drugs provides therapeutic guidance for the clinician (Sachdeva et al., 2009). According to the system, category A is considered the safest during pregnancy while Category X is absolutely contraindicated during pregnancy (FDA, 2005; Pangle, 2006). To assess women’s awareness about risk medication, the questionnaire asked them to enumerate the main drugs that should be avoided during pregnancy (Q12). About 60% of the participants were able, individually, to name some medications to be avoided during pregnancy. By comparing the drugs mentioned by the pregnant women with the FDA categories of risk medications an agreement between both categories was revealed with 23 hits out of 32 (Table 5). These results indicated that a relatively good awareness of about 60% of pregnant women in Taif in Saudi Arabia. Obviously, this awareness may be due to the high % of educated women participating in the study.

Table 5.

Agreement between drugs to be avoided in pregnancy (as indicated by participants) as compared to FDA categorization.

| Drugs | FDA categorization | Pregnant women categorization (drugs-to-be-avoided) according to question 18 |

|---|---|---|

| Analgesics and antipyretics | B and C | √ |

| Acetaminophen | B | × |

| Aspirin | C | √ |

| Antiemetics: doxylamine, meclizine, cyclizine, dimenhydrinate | B | NA |

| Antibiotics | ||

| Penicillin, Ampicillin, Amoxycillin | B, C and D | √ |

| Cloxacillin Cephalosporins |

B | |

| Erythromycin | B | √ |

| Gentamicin | C | √ |

| Amikacin | C/D | √ |

| Streptomycin | D | √ |

| Sulfonamides | B/D | √ |

| Tetracyclines | D | √ |

| Amoebicides: Metronidazole | B | NA |

| Anthelmentics | B | NA |

| Anthelmentics:piperazine, mebendazole | B | NA |

| Antimalarials | C | NA |

| Antifungals | C | NA |

| Vitamins: B,C,D,E, folic acid | A | √ |

| Hormones | ||

| Thyroxine | A | √ |

| Androgens | X | Na |

| Estrogens | X | √ |

| Progestogens Hydroxyprogestrone |

D | |

| Medroxyprogestrone | D | √ |

| Norethindrone | X | √ |

| Norgestrel | X | √ |

| Bronchodilators | C | NA |

| Others | ||

| Warfarin | X | √ |

| Vitamin A | X | √ |

| Oral Antidiabetics | X | √ |

| Anti-depressants | X | √ |

| Anticancer drugs | X | √ |

4. Discussion

Availability and access to drug-related information as well as beliefs of pregnant women about medications determine their decision on drug administration during pregnancy. The attitudes and beliefs regarding medication use have been extensively reported using beliefs about medications questionnaire (BMQ) (Jonsdottir et al., 2009; Jorgensen et al., 2006; Mardby et al., 2007; Menckeberg et al., 2008); however, to our knowledge, this is the first Saudi study to specifically describe pregnant women’s use, beliefs and awareness toward medications.

The beliefs about medication decides patient’s compliance or adherence to a certain medication (De las Cuevas et al., 2011; Saks et al., 2012), while this is true for different patients (Emilsson et al., 2011; Farmer et al., 2006), it is even more exaggerated for pregnant women; in this context, whenever faced with the decision on whether or not to use medication during pregnancy, women will ponder on multi-factors about the need of the medication against the concerns about possible risks to the fetus.

The current Saudi study demonstrated that most women generally believed that medications are not harmful, yet they should be used cautiously in pregnancy. This is in agreement with previous studies reporting that pregnant women are very cautious and often unsure about medication use, and that they often have concerns regarding the risks of drug use during pregnancy (Einarson, 2007; Koren et al., 1989; Sanz et al., 2001).

Our Saudi study indicated that the majority of participants did not believe drugs are responsible for congenital abnormalities of their newborns. An early study reported 19% of pediatric inpatients – in King Khalid University Hospital in Riyadh city of Saudi Arabia – had congenital or genetically-determined disorders (Bahakim, 1993). A more recent study by Alshehri (2005) reported a higher percent (59.1%) of neonates with congenital abnormalities in Asir Central Hospital during six years (1997–2002). Although the percent of congenital anomalies seemed to be rising in The Arabian Peninsula (Al-Odaib et al., 2003), our study demonstrated that 5.6% was the prevalence of anomalies in the population studied herein. Our study indicated that pregnant women did not believe that drugs are responsible for their newborn anomalies. Instead, the anomalies can be attributed to parental consanguinity and family history. This was reported in previous studies like Alshehri study (Alshehri, 2005) and several other publications (Al-Abdulkareem and Ballal, 1998; Al-Hussain and Al-Bunyan, 1997; Khan et al., 1990). These studies indicated that consanguineous marriages in Saudi Arabia are high (60%) and this has provided a background in which these genetic diseases abound (Al-Hussain and Al-Bunyan, 1997).

Interestingly, most women in this study were reluctant or unsure about the use of herbal remedies during pregnancy this was reflected by low percent of herbal users (4.6% only). This reflects a more conservative attitude than that seen in other surveys among British, Italian and Norwegian women in which over 57.8%, 50% and 36% of the women indicated using herbs during pregnancy (Holst et al., 2009; Lapi et al., 2008; Nordeng and Havnen, 2004). However, our findings agree with a recent Norwegian study (Nordeng et al., 2010a). The recent focus on possible adverse effects of herbal remedies and the large controversy between different studies on the risk factors for natural remedy use in pregnancy could be an explanation for such a restrictive attitude (Holst et al., 2009; Kebede et al., 2009; Tiran, 2005).

As previously shown in other communities, sociodemographic factors, such as education and occupation, may have a significant impact on patients’ attitudes and beliefs toward medications (Horne and Weinman, 1999; Mardby et al., 2007; Phatak and Thomas, 2006). In our study, a higher level of education and health-related job were the only sociodemographic factors associated with more positive beliefs about medications.

Our study revealed inadequate drug-related information received by pregnant women especially from pharmacist. While this may contribute to more negative beliefs on medications yet the high prevalence of well educated women participating in the current study (majority were housewives) makes it easier for the women to internet-search and gain knowledge about drug-use in pregnancy. When compared with women in other occupations, women in a health-related occupation had more knowledge about the risks of untreated illness during pregnancy and believed that physicians should be consulted regarding the use of herbal remedies. This possibly reflects a higher degree of medical knowledge and trust in physicians among women who work in health-related fields.

The scarcity of information on medication may contribute to the false and/or negative beliefs on medications. The scarcity of information about drugs was revealed by the high % of women who reported reading the medication leaflet in normal state (Q18; 78%) and further higher percent in pregnancy state (Q19; 86%). This might also reflect their hesitation and skepticism regarding drug usage in pregnancy.

The impact of having a higher frequency of well-educated women, despite most being housewives, was also evident in superior participants’ percent (∼60%) to categorize drugs (safe/to be avoided). Most of these drugs were in agreement with the FDA categorization with 23 hits out of 32 (about 72%). The educational status of women in Saudi Arabia is quite in agreement with participants in our study. According to the World Bank report 2008, 95.9% of female youths (age 15–24) and 79.4% of female adults (ages 15 and above) are literate. According to the World Bank report, female students in higher education in Saudi Arabia outnumber those in Jordan, Lebanon, Tunisia and West Bank and Gaza. The high occurrence of multiparous women (85%) also contributes to such good knowledge of to-be-avoided medications.

It is noteworthy that 82% of the women participating in this study are housewives. This is in agreement with the World Bank report stating that women comprise 60% of Saudi Arabia’s college students but only 21% of its labor force, much lower than in neighboring countries.

5. Limitations

A limitation of this survey was the prevalence of well-educated women (67% reported a university degree) which might have influenced the analysis in terms of the participants’ awareness of medications or at least capability to get knowledge about drugs. However this agrees with the educational status of women in Saudi Arabia so it represents the actual situation. Moreover, the study included a high number of multiparous women (characteristic of the Saudi community) who gained knowledge about drug use from multi-pregnancy. These two issues may affect the transferability of our findings on the whole population. The response rate was quite high where 92% of approached women completed the survey.

6. Conclusion

The study was indicative of the influence of the characteristics of pregnant women in the Saudi Community on the medication intake. The insufficient information regarding drugs in pregnancy from the clinical practitioners, is an area that needs further improvement in the future. Pharmacists, with expertise in providing women with positive beliefs about medications during pregnancy and in optimizing drug therapy outcomes, are valuable components of the healthcare team and should be increasingly involved in public health efforts. Health-care professionals should be aware of women’s attitudes when advising them to take medication during pregnancy.

Ethical approval

The study did not require a review board approval. It is anonymous and involves no risk to participants. Pregnant women filled a questionnaire about their beliefs regarding medication use in pregnancy. The research is non-controversial. There is a consent statement in the questionnaire (see supporting information file). The study conformed to the ethical principles of the National Committee of Medical & Bioethics, King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST), Riyadh, KSA.

Acknowledgements

We thank all pregnant women for their collaboration in the study. Special thanks are due to all the midwives in Al-Hada Military Hospital, Taif, Saudi Arabia for their continuous support during the execution of the study.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Appendix I. Pregnant Women’s use, perception and knowledge of medication, Saudi Study

Consent Statement: This survey is conducted to identify pregnant women’s perception of medicine use. The collected information will be anonymously recorded (no need to write your name) and only used for research purposes. As we go through the questionnaire, please feel free not to answer if you do not wish to give additional information. Your cooperation is highly appreciated.

References

- Al-Abdulkareem A.A., Ballal A.G. Consanguineous marriages in an urban area of Saudi Arabia: rates and adverse health effects on the offspring. J. Community Health. 1998;23:75–83. doi: 10.1023/a:1018727005707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hussain M., Al-Bunyan M. Consanguineous marriages in a Saudi population and the effect of inbreeding on prenatal and postnatal mortality. Ann. Trop. Paediatr. 1997;17:155–160. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1997.11747879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Odaib A.N., Abu-Amero K.K., Ozand P.T., Al-Hellani A.M. A new era for preventive genetic programs in the Arabian Peninsula. Saudi Med. J. 2003;24:1168–1175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alshehri M.A. Pattern of major congenital anomalies in Southwestern Saudi Arabia. Bahrain Med. Bull. 2005;27:22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Baggley A., Navioz Y., Maltepe C., Koren G., Einarson A. Determinants of women’s decision making on whether to treat nausea and vomiting of pregnancy pharmacologically. J. Midwifery Womens Health. 2004;49:350–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahakim H. Pediatric inpatients at the King Khalid University Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia 1985–1989. Ann. Saudi Med. 1993;13:8–13. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1993.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banhidy F., Lowry R.B., Czeizel A.E. Risk and benefit of drug use during pregnancy. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2005;2:100–106. doi: 10.7150/ijms.2.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De las Cuevas C., Rivero A., Perestelo-Perez L., Gonzalez M., Perez J., Penate W. Psychiatric patients’ attitudes towards concordance and shared decision making. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011;85:e245–e250. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deborah E., McCarter M., Spaulding M.S. Medications in pregnancy and lactation. Am. J. Matern. Child Nurs. 2005;30:10–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo M.R., Haskard K.B., Williams S.I. Health beliefs, disease severity, and patient adherence: a meta-analysis. Med. Care. 2007;45:521–528. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318032937e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einarson A. The way women perceive teratogenic risk: how it can influence decision making during pregnancy regarding drug use or abortion of a wanted pregnancy. In: Koren G., editor. Medication Safety in Pregnancy and Breastfeeding. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2007. pp. 309–312. [Google Scholar]

- Emilsson M., Berndtsson I., Lotvall J., Millqvist E., Lundgren J., Johansson A., Brink E. The influence of personality traits and beliefs about medicines on adherence to asthma treatment. Prim. Care Respir. J. 2011;20:141–147. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2011.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erebara A., Bozzo P., Einarson A., Koren G. Treating the common cold during pregnancy. Can. Fam. Physician. 2008;54:687–689. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer A., Kinmonth A.L., Sutton S. Measuring beliefs about taking hypoglycaemic medication among people with type 2 diabetes. Diabet. Med. 2006;23:265–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA, 2005. Reviewer Guidance. Evaluating the risks of drug exposure in human pregnancies. <http://www.fda.gov/cber/guidelines.htm>.

- Gatti M.E., Jacobson K.L., Gazmararian J.A., Schmotzer B., Kripalani S. Relationships between beliefs about medications and adherence. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2009;66:657–664. doi: 10.2146/ajhp080064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover D.D., Amonkar M., Rybeck B.F., Tracy T.S. Prescription, over-the-counter, and herbal medicine use in a rural, obstetric population. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;188:1039–1045. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holst L., Wright D., Haavik S., Nordeng H. The use and the user of herbal remedies during pregnancy. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2009;15:787–792. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne R., Weinman J. Patients’ beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J. Psychosom. Res. 1999;47:555–567. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne R., Weinman J., Hankins M. The beliefs about medicines questionnaire: the development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychol. Health. 1999;14:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ito S., Koren G., Einarson T.R. Maternal noncompliance with antibiotics during breastfeeding. Ann. Pharmacother. 1993;27:40–42. doi: 10.1177/106002809302700110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsdottir H., Friis S., Horne R., Pettersen K.I., Reikvam A., Andreassen O.A. Beliefs about medications: measurement and relationship to adherence in patients with severe mental disorders. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2009;119:78–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen T.M., Andersson K.A., Mardby A.C. Beliefs about medicines among Swedish pharmacy employees. Pharm. World Sci. 2006;28:233–238. doi: 10.1007/s11096-005-2907-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kacew S. Fetal consequences and risks attributed to the use of prescribed and over-the-counter (OTC) preparations during pregnancy. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1994;32:335–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamuhabwa A., Jalal R. Drug use in pregnancy: knowledge of drug dispensers and pregnant women in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2011;43:345–349. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.81503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kebede B., Gedif T., Getachew A. Assessment of drug use among pregnant women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2009;18:462–468. doi: 10.1002/pds.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S.M.D., Ahmad G.S., Abu-Talib A. Are congenital anomalies more frequent in Saudi Arabia? Ann. Saudi Med. 1990;10:488–489. [Google Scholar]

- Koren G., Bologa M., Long D., Feldman Y., Shear N.H. Perception of teratogenic risk by pregnant women exposed to drugs and chemicals during the first trimester. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1989;160:1190–1194. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90186-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapi F., Vannacci A., Moschini M., Cipollini F., Morsuillo M., Gallo E., Banchelli G., Cecchi E., Di Pirro M., Giovannini M.G., Cariglia M.T., Gori L., Firenzuoli F., Mugelli A. Use, attitudes and knowledge of complementary and alternative drugs (CADs) among pregnant women: a preliminary survey in Tuscany. Evid. Based Complement Altern. Med. 2008;7:477–486. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nen031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardby A.C., Akerlind I., Jorgensen T. Beliefs about medicines and self-reported adherence among pharmacy clients. Patient Educ. Couns. 2007;69:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardby A.C., Akerlind I., Hedenrud T. General beliefs about medicines among doctors and nurses in out-patient care: a cross-sectional study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2009;10:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-10-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melton M.W. Take two Aspirin or not? Risk of medication use during pregnancy. Mother Baby J. 1995;4:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Menckeberg T.T., Bouvy M.L., Bracke M., Kaptein A.A., Leufkens H.G., Raaijmakers J.A., Horne R. Beliefs about medicines predict refill adherence to inhaled corticosteroids. J. Psychosom. Res. 2008;64:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neame R., Hammond A. Beliefs about medications: a questionnaire survey of people with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:762–767. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordeng H., Havnen G.C. Use of herbal drugs in pregnancy: a survey among 400 Norwegian women. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2004;13:371–380. doi: 10.1002/pds.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordeng H., Koren G., Einarson A. Pregnant women’s beliefs about medications – a study among 866 Norwegian women. Ann. Pharmacother. 2010;44:1478–1484. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordeng H., Ystrom E., Einarson A. Perception of risk regarding the use of medications and other exposures during pregnancy. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2010;66:207–214. doi: 10.1007/s00228-009-0744-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odalovic M., Vezmar Kovacevic S., Ilic K., Sabo A., Tasic L. Drug use before and during pregnancy in Serbia. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2012;34:719–727. doi: 10.1007/s11096-012-9665-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pangle B.L. Drugs in pregnancy and lactation. In: Herfindal E.T., Gourley D.R., editors. Text Book of Therapeutics, Drug and Disease Management. eighth ed. Lippincott William Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2006. pp. 434–448. [Google Scholar]

- Phatak H.M., Thomas J., 3rd. Relationships between beliefs about medications and nonadherence to prescribed chronic medications. Ann. Pharmacother. 2006;40:1737–1742. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porteous T., Francis J., Bond C., Hannaford P. Temporal stability of beliefs about medicines: implications for optimising adherence. Patient Educ. Couns. 2010;79:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizk M.A., Abdel-Aziz F., Ashmawy A.A., Mahmoud A.A., Abuzeid T.M. Knowledge and practices of pregnant women in relation to the intake of drugs during pregnancy. J. Egypt. Public Health Assoc. 1993;68:567–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdeva P., Patel B.G., Patel B.K. Drug use in pregnancy; a point to ponder! Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2009;71:1–7. doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.51941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saks E.K., Wiebe D.J., Cory L.A., Sammel M.D., Arya L.A. Beliefs about medications as a predictor of treatment adherence in women with urinary incontinence. J. Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21:440–446. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz E., Gomez-Lopez T., Martinez-Quintas M.J. Perception of teratogenic risk of common medicines. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2001;95:127–131. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(00)00375-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skouteris H., Wertheim E.H., Rallis S., Paxton S.J., Kelly L., Milgrom J. Use of complementary and alternative medicines by a sample of Australian women during pregnancy. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2008;48:384–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2008.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiran D. Complementary therapies in maternity care: personal reflections on the last decade. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2005;11:48–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ctnm.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veazie P.J., Cai S. A connection between medication adherence, patient sense of uniqueness and the personalization of information. Med. Hypotheses. 2007;68:335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.04.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J., Myson V., Steward S., Jones G., Wilson J.F., Kerr M.P., Smith P.E. Self-discontinuation of antiepileptic medication in pregnancy: detection by hair analysis. Epilepsia. 2002;43:824–831. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.38601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]