Summary

The HIV-1 Gag protein orchestrates all steps of virion genesis, including membrane targeting and RNA recruitment into virions. Using crosslinking-immunoprecipitation (CLIP) sequencing, we uncover several dramatic changes in the RNA binding properties of Gag that occur during virion genesis, coincident with membrane binding, multimerization and proteolytic maturation. Prior to assembly, and after virion assembly and maturation, the nucleocapsid domain of Gag preferentially binds to psi and Rev Response elements in the viral genome, and GU-rich mRNA sequences. However, during virion genesis, this specificity transiently changes in a manner that facilitates genome packaging; nucleocapsid binds to many sites on the HIV-1 genome and to mRNA sequences with a HIV-1-like, A-rich nucleotide composition. Additionally, we find that the matrix domain of Gag binds almost exclusively to specific tRNAs in the cytosol, and this association regulates Gag binding to cellular membranes.

Introduction

The HIV-1 Gag protein coordinates all major steps in virion assembly. In so doing, it changes subcellular localization, multimerization state and becomes proteolytically processed (Bell and Lever, 2013; Sundquist and Krausslich, 2012). One function of Gag is to selectively package a dimeric, unspliced viral RNA genome selected from a pool of excess cellular RNAs and spliced viral mRNAs (Kuzembayeva et al., 2014; Lu et al., 2011b; Rein et al., 2011). Genome packaging requires binding of the nucleocapsid (NC) domain to viral genomic RNA (Aldovini and Young, 1990; Berkowitz et al., 1993; Gorelick et al., 1990). Selection of the viral genome is thought to be governed by a cis-acting packaging element, psi (Ψ), within the 5’ leader of the viral genome, composed of sequences in the unique 5’ region (U5) and between the tRNA primer binding site (PBS) and the 5’ portion of the Gag open reading frame (Aldovini and Young, 1990; Clavel and Orenstein, 1990; Lever et al., 1989; Luban and Goff, 1994). This element is highly structured (Clever et al., 1995; Harrison and Lever, 1992; McBride and Panganiban, 1996) and may exist in two conformations that favor translation versus dimerization and packaging (Lu et al., 2011a).

Knowledge of the viral RNA sequences that are directly bound by Gag is largely inferred from determinations of functional packaging signals in genetic studies, complemented by limited in vitro data. No assay has yet demonstrated a direct interaction between Gag and Ψ in a biologically relevant setting, i.e. in cells or virions. Additionally, some findings suggest that sequences outside Ψ might facilitate genome packaging. First, disruption of Ψ does not eliminate specific RNA encapsidation (Clever and Parslow, 1997; Laham-Karam and Bacharach, 2007; McBride and Panganiban, 1997). Second, sequences outside Ψ can increase HIV-1 vector titers or virion RNA levels (Berkowitz et al., 1995; Chamanian et al., 2013; Das et al., 1997; McBride et al., 1997; Richardson et al., 1993). Third, virions can package cellular RNAs (Muriaux et al., 2001; Rulli et al., 2007), lacking a Ψ sequence, particularly in the absence of viral RNA. The RNA properties that underlie these findings are unknown.

HIV-1 Gag molecules exist as monomers or low order multimers in the cell cytosol, and form higher order multimers only after binding to the plasma membrane (Kutluay and Bieniasz, 2010). Imaging studies indicate that small numbers of Gag molecules recruit a single viral RNA dimer to the plasma membrane, nucleating the assembly of thousands of Gag molecules into an immature virion (Jouvenet et al., 2009). Thereafter, Gag proteolysis liberates NC and other Gag domains, triggering virion maturation. Whether these changes in Gag/NC configuration affect its RNA-binding properties is unknown, but there is clear potential for the RNA binding specificity of Gag to change during virion genesis.

Although NC is thought to be the primary Gag domain that binds to viral RNA, the matrix (MA) domain can also bind RNA in vitro (Alfadhli et al., 2009; Chukkapalli et al., 2010; Cimarelli and Luban, 1999; Levin et al., 2010; Ott et al., 2005; Ramalingam et al., 2011). N-terminal basic amino-acids in MA that mediate membrane binding also drive in vitro RNA binding (Chukkapalli et al., 2013; Chukkapalli et al., 2010; Hill et al., 1996; Saad et al., 2006; Shkriabai et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 1994). Because RNA is better able to block MA binding to membranes that are devoid of phosphatidylinositol-(4,5)-bisphosphate PI(4,5)P2 (Chukkapalli et al., 2013; Chukkapalli et al., 2010; Dick et al., 2013), RNA might help to target particle assembly to the plasma membrane. However, RNA binding by MA is not thought to be specific, and whether it actually occurs in cells is unknown.

To obtain a complete account of the RNA sequences bound by Gag during virion genesis, we employed crosslinking-immunoprecipitation-sequencing PAR-CLIP and HITS-CLIP techniques (Hafner et al., 2010; Licatalosi et al., 2008). We find that cytosolic Gag binds to three sequence elements within the 5’ leader of the viral genome, that are brought together in a secondary structure that defines a minimal Ψ element. We also find that cytosolic Gag binds to additional discrete sites on the viral genome, including the Rev Response Element (RRE). Gag association with the plasma membrane and its assembly into immature virions trigger a profound change in RNA binding specificity that favors genome packaging. Subsequently, particle maturation largely reverses this change. Finally, we find that MA is a bona fide RNA binding domain that selects a subset of tRNAs in the cystosol which regulate Gag-membrane binding. Overall, these studies provide a dynamic, quantitative and high-resolution account of the global changes in Gag-RNA binding during HIV-1 virion genesis.

Results

CLIP assay for HIV-1 Gag-RNA binding

We employed recently developed CLIP approaches (Hafner et al., 2010; Licatalosi et al., 2008) to identify RNA molecules bound by HIV-1 Gag protein during particle genesis. To facilitate the purification of Gag-RNA adducts, we generated HIV-1NL4-3 (subtype B) and HIV-1NDK (subtype D)] proviral clones carrying an inactivating mutation in the viral protease and 3 consecutive copies of a HA-tag within the stalk region of MA (MA-3xHA/PR-). The MA modification did not affect Gag expression or assembly and had only a small effect on the infectiousness of a PR+ virus (Fig. S1A, S1B). Cells transfected with HIV-1NL4-3-MA-3xHA/PR-proviral plasmids were grown in the presence of ribonucleoside analogs (4SU or 6SG), which also had minimal effects on infectious virion yield (Fig. S1C, S1D).

Cells and virions were UV-irradiated, lysed and digested with ribonuclease A. Then Gag-RNA adducts were immunopurified, end-labeled with γ-32P-ATP and visualized after SDS-PAGE and transfer to nitrocellulose membranes. Gag-RNA adduct formation was dependent on UV irradiation in cells and virions (Fig. 1A). We primarily used 4SU-based CLIP thereafter, because it efficiently generated crosslinks, while 6SG and unmodified RNA was used for confirmatory purposes. Gag-crosslinked RNA oligonucleotides were purified, sequenced and mapped to the HIV-1 and human genomes (See Extended Experimental Procedures). Reads derived from the terminal repeat (R) region of the HIV-1 genome ambiguously map to 5’ and 3’ ends but are displayed at 5’ end of the viral genome, and cautiously interpreted, in our analyses.

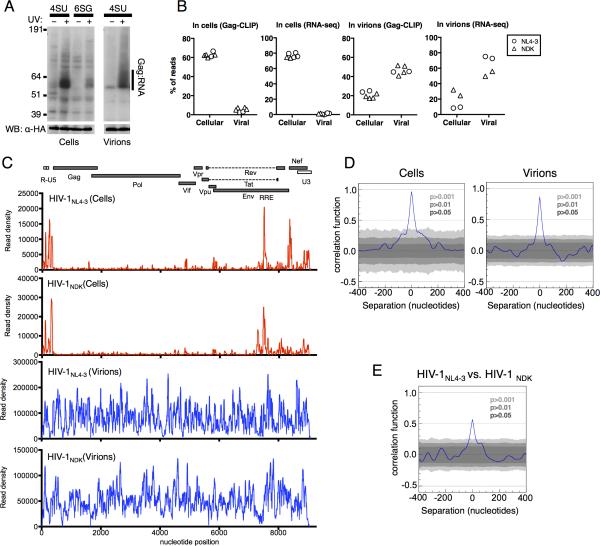

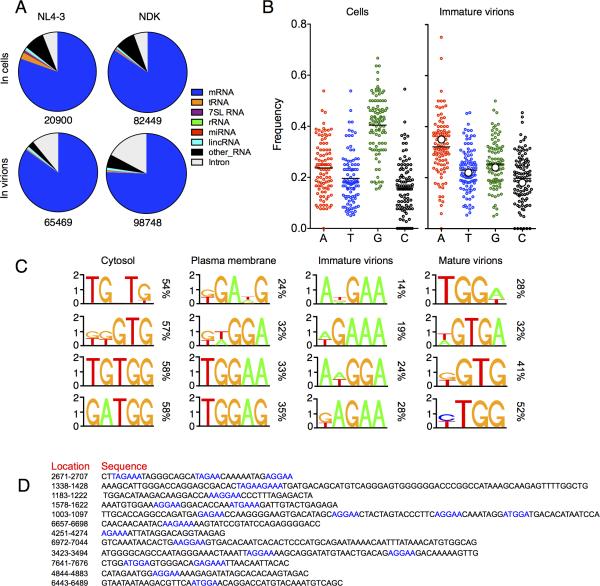

Figure 1. Viral RNA binding by Gag in cells and virions.

(A) Gag-RNA adducts immunoprecipitated from HIV-1NL4-3(MA-3xHA/PR-) expressing, 4SU or 6SG-fed, cells or progeny virions, visualized by autoradiography (upper). Western blot analysis of the same membranes (lower).

(B) Proportion of reads that map to cellular and viral genomes obtained from Gag-CLIP and RNA-seq experiments performed on cell lysates and immature virions. Each point represents a separate library.

(C) Frequency distribution of nucleotide occurrence (read density) in reads mapping to viral genomes. A schematic diagram of HIV-1 genome features shown above is co-linear.

(D) Correlation analysis of HIV-1NL4-3 Gag-binding to viral RNA in cells and virions from independent CLIP experiments.

(E) Correlation analysis of HIV-1NL4-3 vs. HIV-1NDK Gag-binding to viral RNA in virions. (See also Figure S1 and Table S1)

In six independent Gag-CLIP libraries prepared from HIV-1NL4-3(MA-3xHA/PR-) or HIV-1NDK(MA-3xHA/PR-) expressing cells, 2.5 to 7% of the total reads were HIV-1 derived, while ~60% were from host cell RNA (Fig. 1B, Table S1). In comparison, RNA-seq libraries, which measure the abundance of cellular and viral RNAs, contained 0.3 to 1.6% of reads derived from HIV-1 and ~75% were from cellular RNA (Fig. 1B, Table S1). In immature virions, ~50% and 20% of CLIP reads were from viral and host RNAs, respectively (Fig. 1B, Table S1), broadly similar to RNA abundance as determined by RNA-seq (Fig. 1B). Thus, viral RNA sequences were somewhat selectively bound by Gag in cells, but were enriched to a far greater extent in virions.

HIV-1 RNA sequences bound by Gag in cells and virions

We plotted the frequencies with which each nucleotide in the HIV-1NL4-3 genome was represented in reads from cell and virion derived HIV-1NL4-3(MA-3xHA/PR-) Gag-CLIP libraries (‘read density’, Fig. 1C). In cells, a major proportion of the Gag-linked reads were derived from discrete sites in the viral genome. As might be expected, the 5’ leader was a frequent site of Gag binding. However, additional sites of frequent Gag binding included the RRE, sequences overlapping the Nef start codon, and untranslated sequences in U3 (Fig. 1C). Several other sites on the viral genome were bound by Gag, but at lower frequencies. The distribution of Gagcrosslinked viral RNA reads was highly reproducible in HIV-1NL4-3(MA-3xHA/PR-) Gag CLIP-seq libraries as indicated by the nearly perfect correlation between independent experiments (Fig. 1D). However, when a divergent HIV-1NDK strain was included in these analyses, the only prominent Gag binding sites that were present in both strains were the 5’ leader and RRE (Fig. 1C).

The frequency with which Gag was crosslinked to sites across the viral genome was starkly different in immature virions. Sites of frequent Gag binding on HIV-1NL4-3 RNA were far more numerous in immature virions than in cells. Moreover, specific Gag binding to the 5’ leader and RRE was not evident in immature virions (Fig. 1C). The pattern of Gag binding frequency across the viral genome was highly reproducible (Fig. 1D) and was unlikely to be generated by methodological bias during CLIP-seq library generation, because it was largely unaffected by the choice of ribonucleoside analog [(4SU vs. 6SG) Fig. S1E, F], ribonuclease [(RNase A vs. RNase T1), Fig. S1G, H] or the immunoprecipitating antibody [(anti-HA vs. anti-NC), Fig. S1I, J] used to generate the CLIP libraries. HIV-1NDK Gag similarly bound to sites throughout the viral genome (Fig. 1C). Despite overall similarity, there were some clear discrepancies in viral RNA sites that were frequently occupied by HIV-1NL4-3 and HIV-1NDK Gag (Fig. 1E, S1K), presumably due to differences in target RNA sequence, or subtle differences in the RNA binding specificities of the two Gag proteins.

The 3xHA tag did not affect the pattern of Gag binding at sites proximal or distal to the insertion site (Fig. S1L). Moreover, auto-correlation analysis of Gag binding frequency revealed no peaks other than at a separation of s=0 (Fig. S1M). Thus, the frequency with which a given site in the viral genome was bound by Gag in immature virions appeared unaffected by its position relative to the Ψ sequence or other Gag binding sites. Rather, Gag binding appeared to be a function of local nucleotide sequence or structure.

Analysis of Gag binding to 5’ leader and RRE

In cells, the most prominent Gag binding sites on the viral genome coincided with the most prominently structured elements in the HIV-1 genome, namely the 5’ leader and the RRE (Fig 1C). However, Gag was not bound across the 5’ leader and the RRE with uniform frequency, but selectively associated with small determinants within these structures. In the case of the 5’ leader, Gag was most frequently bound to three distinct sequences, including one at the 5’ end of U5, a second site between the PBS and the major splice donor, and a third site 3’ to the major splice donor (Fig. 2A). These sites are separated from each other in linear sequence by approximately 100 nucleotides. Strikingly, however, an NMR based analysis of the structure of a Ψ sequence (Lu et al., 2011a) predicts that these three Gag-binding sequences would be in close proximity, and partly base paired with each other upon RNA folding into a structure that favors genome packaging (Fig. 2B).

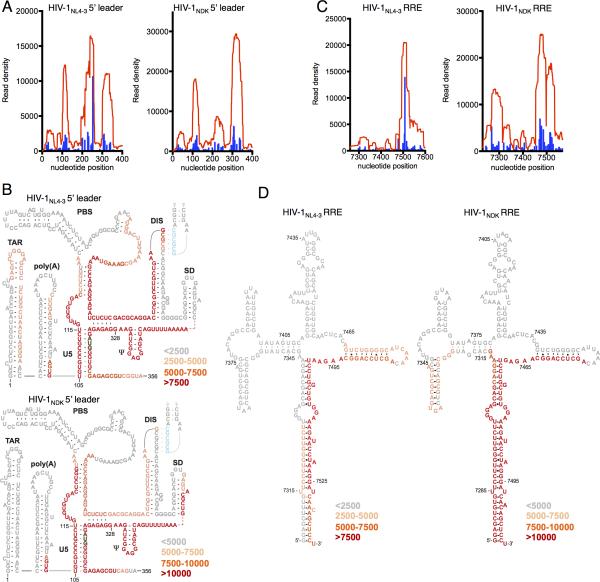

Figure 2. Details of HIV-1 Gag binding to Ψ and RRE.

(A, B) Read density distribution (red) and T-to-C mutations (blue) within the 5’ leader (nucleotides 1-400, A) and RRE (B) in Gag-CLIP experiments with HIV-1NL4-3 and HIV-1NDK.

(C, D) Depiction of read density distribution in the context of predicted secondary structures of the 5’ leader (nucleotides 1-400, C) and RRE (D) in Gag-CLIP experiments with HIV-1NL4-3 and HIV-1NDK. Color intensity represents read density indicate in the key. (See also Figure S2)

Frequent Gag binding to the RRE occurred in stem I, a site clearly distinct from the primary site of Rev-RRE interaction in stem-loop IIB (Malim et al., 1990) (Fig. 2C, D). Importantly, the Gag-bound reads derived from both the 5’ leader and RRE contained high rates of T-to-C substitution, identifying individual nucleotide bases that were in close proximity to Gag (Fig. 2A, C). Additionally, CLIP-seq experiments performed using 4SU or 6SG yielded a similar footprint of Gag on viral RNA, with 5’ leader and RRE binding prominently featured (Fig. S2A, B). Thus, the apparently specific binding of Gag to these sequence elements was not an artifact of the particular crosslinking nucleotide used.

Changes in Gag RNA binding to viral RNA during HIV-1 virion assembly

Given the stark differences in the interaction of Gag with viral RNA in cells and immature virions, we attempted to determine what triggers this dramatic change. To this end, cells were fractionated after UV irradiation (Fig. 3A) and Gag-RNA adducts were immunoprecipitated from cytosol, in which Gag is primarily monomeric, and from a membrane fraction where multimerized assembly intermediates form (Kutluay and Bieniasz, 2010) (Fig. 3B). The RNA binding profile of cytosolic Gag was nearly indistinguishable from that described above for total cell lysates, with Ψ and RRE representing specific binding sites (Fig. 3C, D). Similarly a myristoylation-defective Gag mutant (Gag-G2A), which does not bind efficiently to membranes was also restricted to discrete binding sites on viral RNA (Fig. S3A). Conversely, Gag that was immunoprecipitated from membrane fractions was bound to many sites on the viral genome, and although binding to Ψ and RRE remained prominent, the overall RNA binding profile of cell membrane-associated Gag otherwise resembled that of immature virion-associated Gag (Fig. 3C, D, S3B). A late-domain mutant Gag protein (Δp6) was similarly bound to sites throughout the viral genome (Fig. 3C) indicating that the completion of budding was not required for this apparent shift in RNA binding specificity. Notably, a Gag CAΔCTD mutant that is fully competent to localize to the plasma membrane, but is significantly impaired in the formation of high-order multimers (Kutluay and Bieniasz, 2010) exhibited a binding profile that was more reminiscent of cytosolic Gag, although additional sites in the viral genome were bound with some prominence (Fig. 3C). Together, these data indicate that high-order oligomerization of Gag at the plasma membrane drives a profound change in Gag's RNA-binding properties (Fig. 3C, D, S3B), dramatically increasing the extent to which Gag and viral RNA interact with each other.

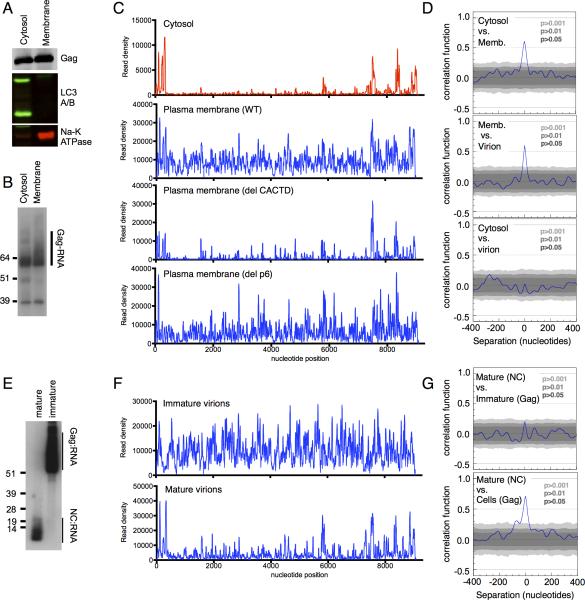

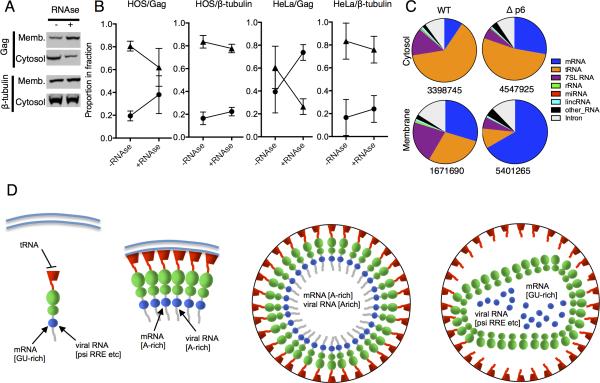

Figure 3. Changes in Gag binding to viral RNA during virion assembly and maturation.

(A) Western blot analysis of Gag, and markers of cytosol (LC3A/B) and plasma membrane (Na-K ATPase) in fractionated, 4SU-fed 293T cells transfected with a HIV-1NL4-3(MA-3xHA/PR-) proviral plasmid.

(B) Autoradiogram of Gag-RNA complexes recovered from fractions in CLIP assays.

(C) Read density distribution on viral RNA from CLIP experiments in which WT and mutant Gag proteins were immunoprecipitated from cell fractions.

(D) Correlation analysis of CLIP data from cell fractions and immature virions.

(E) Autoradiogram of NC-RNA and Gag-RNA complexes recovered from mature and immature virions using an anti-NC antibody.

(F) Read density distribution on viral RNA from CLIP experiments in which Gag and NC proteins were immunoprecipitated from immature and mature virions using an anti-NC antibody.

(G) Correlation analysis of CLIP data from cells, mature and immature virions. (See also Figure S3)

Changes in Gag-viral RNA binding triggered by virion maturation

Gag undergoes proteolytic cleavage during virion maturation, liberating NC, which is then thought to condense with the viral RNA inside a remodeled conical core (Sundquist and Krausslich, 2012). To determine whether virion maturation affects Gag-viral RNA interactions, we did CLIP experiments using an antibody that specifically recognizes NC (Fig. S3D, E) and could efficiently immunoprecipitate Gag-RNA and NC-RNA adducts from immature and mature virions, respectively (Fig. 3E). Comparison of RNA sequences bound by Gag in immature virions and NC in mature virions revealed profound changes accompanying virion maturation (Fig. 3F, G). Unlike intact Gag in immature virions, NC in mature virions preferentially occupied discrete sequences on the viral genome, that coincided in large part with the major sites of Gagviral RNA interaction in the cytosol (i.e. Ψ and RRE) (Fig. 3F, G). Many of the additional prominent NC-binding sites in mature virion RNA were also bound by intact Gag in the cytosol at lower frequencies (Fig. S3F). Thus, the RNA binding properties of NC in mature virions resemble that of unassembled Gag in the cytosol to a surprising extent, exhibiting statistically significant correlation (Fig. 3G), possibly reflecting the monomeric state of cytosolic Gag and mature NC.

Gag binding to viral RNA and viral RNA packaging in the absence of Ψ or RRE

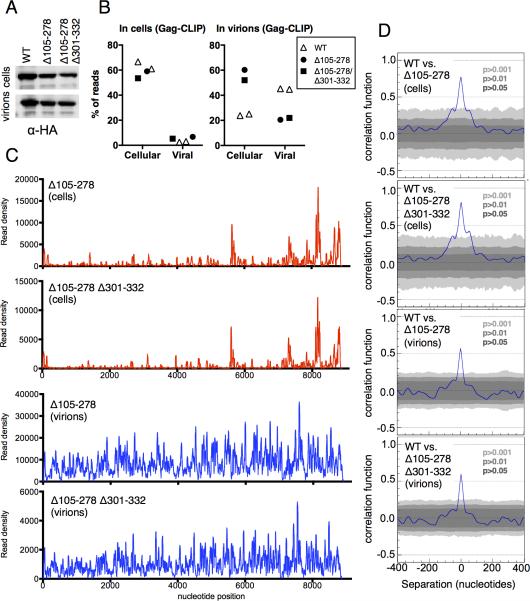

To test the importance of the Gag/NC-binding sites in Ψ and RRE, we generated viruses carrying deletions of these sequences. First, we determined whether the Gag binding to additional sites on the viral genome in cells and in virions required initial binding to Ψ. To this end, we performed CLIP experiments using viral constructs carrying deletions of two of the three Gag-binding sequences (Δ105-278), or all three Gag binding sequences (Δ105-278/Δ301-332) within Ψ. These deletions left sequences surrounding the major 5’ splice donor intact, and only modestly reduced Gag expression (Fig. 4A). Surprisingly, in cells, neither the Δ105-278 nor the Δ105-278/Δ301-332 mutation affected the fraction of Gag-crosslinked reads derived from viral versus human genomes (Fig. 4B). Moreover, in immature virions, these Ψ-deletions caused only a modest ~3-fold decrease in the fraction of reads derived from the viral genome, with a corresponding increase in the fraction of reads from cellular RNAs (Fig. 4B). The pattern of Gag binding to viral RNA in cells was not greatly affected by the Ψ deletions (Fig 4C, D), although there was an apparent reduction in the frequency with which RRE was bound. Similarly, the overall binding pattern of Gag binding to viral RNA in immature virions was also relatively unperturbed by Ψ deletions (Fig. 4C, D, S4A). However, there was a tendency for read densities to increase towards the 3’ end of the viral genome, perhaps reflecting the incorporation of spliced viral RNAs into virions generated by Ψ-deleted genomes (Clever and Parslow, 1997; Houzet et al., 2007; Russell et al., 2003). Importantly, these results indicate that multiple sites on the viral genome bind to Gag independently of Ψ and facilitate HIV-1 genome packaging.

Figure 4. Gag binding to viral RNA in the absence of Ψ.

(A) Western blot analysis (anti-HA) of Gag protein expression from WT and Ψ-deleted (Δ105-278 and Δ105-278/Δ301-332) proviral plasmids.

(B) Proportion of reads from cell and virion CLIP experiments that map to cell and viral genomes, following transfection of WT or Ψ-deleted proviral plasmids. Each point represents a separate library.

(C) Read density distribution on viral RNA from CLIP experiments in which Gag proteins were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates and immature virions following transfection with Ψ-deleted proviral plasmids.

(D) Correlation analysis of CLIP data from cells and virions using WT and Ψ-deleted proviral plasmids. (See also Figure S4).

To analyze the effects of Gag-RRE interaction on HIV-1 infectivity, we generated viruses in which Rev was deleted and the nuclear export of unspliced viral RNAs was mediated by the Mason-Pfizer monkey virus constitutive transport element (CTE) to circumvent effects of RRE on RNA nuclear export (Fig. S4B). In this setting, the presence or absence of RRE had no discernible effect on Gag protein levels or infectious virus yield (Fig. S4C), Although it is formally possible that the MPMV CTE might recapitulate the Gag binding properties of RRE, this analysis suggests that Gag RRE interactions do not regulate Gag expression and are not required for RNA packaging.

Changes in the sequence specificity of Gag RNA binding during virion genesis

The aforementioned results suggest a degree of redundancy, and contributions from multiple domains of the viral genome to RNA packaging. In an attempt to explain the factors driving the selectivity with which Gag bound to and packaged viral RNA, we determined the identities of cellular mRNA sequences that were most frequently bound to Gag in cells and in virions. Reads that aligned to the human genome were clustered using PARalyzer (Corcoran et al., 2011), which defines a cluster, or binding site, based on the occurrence of a minimum number overlapping reads proximal to a T-to-C substituted crosslinking site in 4SU-based CLIP assays (Table S2). Note that a single cluster is counted once for the analysis shown in Fig. 5A, irrespective of the number or reads associated with it. In cells, >90% of clusters (Gag binding sites) were within genes and ~80% of these were derived from mRNAs (Fig. 5A) with an overlap of >95% between HIV-1NL4-3 and HIV-1NDK Gag-bound mRNA clusters (Fig. S5A). A similar analysis of immature virions generated a collection of clusters that were also mostly derived from mRNAs (Fig. 5A) and overlapped by >70% in HIV-1NL4-3 and HIV-1NDK libraries. Notably, greater discrepancies were observed when the Gag-binding clusters in cells versus virions were compared (Fig. S5A), indicating that many mRNA sequences that are preferred Gag binding sites in cells are not preferred binding sites in virions and vice versa.

Figure 5. Changes in Gag-RNA binding specificity during virion genesis.

(A) Classification of PARalyzer-generated read-clusters that map to cellular RNAs, total number of clusters is indicated.

(B) Nucleotide composition of 100 PARalyzer-generated clusters with largest numbers of reads, derived from Gag-bound host mRNAs in cells and immature virions. Larger white circle symbols indicate nucleotide composition of the HIV-1 genome.

(C) Sequence motifs identified by cERMIT as most frequently occurring in Gag bound, host cell mRNA clusters at various steps of virion genesis. Cumulative percentage of clusters containing the motifs are indicated.

(D) Sequences of the 12 viral genome-derived clusters that are most frequently Gag-bound in immature virions. Motifs matching those identified as preferred binding sites in host mRNAs are highlighted in blue. (See also Figure S5 and Table S2)

We counted the number of reads associated with each cluster and determined the 100 sites in cellular mRNAs that were most frequently bound by Gag in cells and immature virions. The nucleotide composition of these Gag binding sites revealed a striking change in the RNA binding preference of Gag during virion genesis (Fig 5B). In cells, preferred Gag binding sites had a strong tendency to be G-rich (mean G-content of ~40%). In contrast, in immature virions, preferred Gag binding sites displayed a tendency to be A-rich. Remarkably, the mean nucleotide content of the preferred Gag binding sites in cellular mRNAs associated with immature virions was strikingly similar to the nucleotide composition of the HIV-1 genome.

We used cERMIT (Georgiev et al., 2010), to search for sequence motifs that were enriched in Gag-bound cellular mRNA clusters recovered at various stages of virion genesis. G/U-rich sequence motifs were the most often present in host mRNA sequences bound to Gag in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5C). At the plasma membrane, and particularly in immature virions, there was a clear change in binding specificity. Here, Gag bound more frequently to A-rich and A/G-rich cellular mRNA motifs (Fig. 5C), Inspection of the sequences of the twelve clusters most frequently bound by Gag in the viral genome, in immature virions, revealed multiple instances of similar A/G-rich motifs scattered in the viral genome (Fig 5D). In mature virions, RNA binding specificity reverted, and the sequence motifs favored by NC were again G/U-rich. These findings reinforce the notion that Gag binds preferentially to RNAs that have an A-rich nucleotide composition, and particularly to A-rich motifs that are present in the viral genome, transiently during immature virion assembly.

tRNAs are the most frequently Gag-bound RNA in cells, but not in virions

Although the aforementioned analysis focused on Gag binding to mRNA sequences, when the number of individual Gag-bound reads associated with each cluster or binding site was counted, it was evident that mRNAs were responsible for only a fraction (~12%) of the cellular RNA reads crosslinked to Gag. In fact, tRNAs were the dominant RNA species bound by Gag in cells (~60-70% of reads), with 7SL RNA, a known component of HIV-1 virions (Onafuwa-Nuga et al., 2006) constituting the bulk of the remaining reads (Fig. 6A). Strikingly, the fraction tRNA-derived reads was greatly reduced in CLIP-seq libraries prepared from virions as compared to cells. This was not the case for other RNA classes, suggesting that tRNAs were specifically excluded from virions (Fig. 6A).

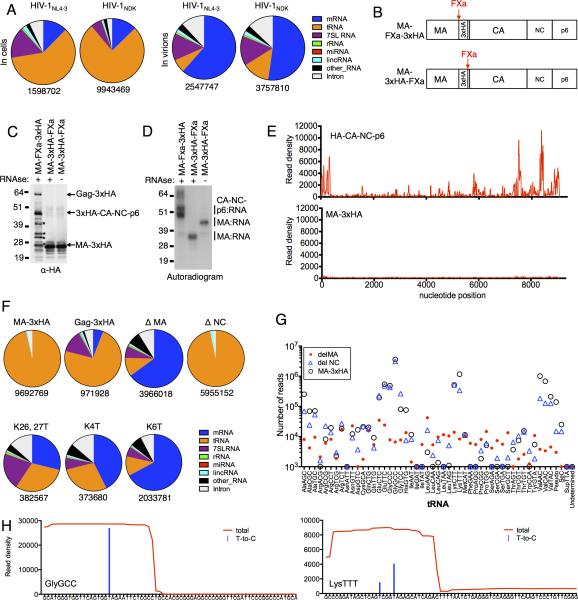

Figure 6. HIV-1 MA binds to specific tRNAs, but not viral RNA.

(A) Classification of individual reads from cell and immature virion Gag-CLIP experiments that map to genes in the host cell genome.

(B) Schematic representation of FXa-cleavable Gag proteins.

(C, D) Western blot analysis (anti-HA, C) and autoradiography (D) of immunoprecipitated (anti-HA) proteins from HIV-1NL4-3 MA-FXa-3xHA/PR- and MA-3xHA-FXa/PR- transfected cells and subjected to the modified CLIP procedure. Cell lysates were treated with Factor Xa protease, and with or without RNase A prior to immunoprecipitation. * indicates breakdown products of the 3xHA-CA-NC-p6 protein that retain the HA tag but are not crosslinked to RNA.

(E) Read density distribution on viral RNA following CLIP analysis of FXa-liberated 3xHA-CANC-p6 and MA-3xHA proteins.

(F) Classification of individual reads that map to cellular genes from cell associated Gag-CLIP experiments employing the FXa-liberated MA-3xHA protein or WT and mutant, uncleaved Gag proteins. Total number of reads is indicated below.

(G) Numbers of reads crosslinked to FXa-liberated MA-3xHA, or uncleaved Gag proteins that lack NC (ΔNC) and MA (ΔMA) that map to each tRNA gene.

(H) Two examples of read density distributions (red) and T-to-C substitutions (blue) at crosslinking sites on tRNAs (Gly(GCC) and Lys(TTT)) following CLIP analysis of FXa-liberated MA-3xHA. (See also Figure S6)

MA binds specifically to particular tRNAs

Although the aforementioned Gag-RNA binding events were assumed to involve the NC domain of Gag, there are numerous reports that MA can interact with viral or cellular RNAs [reviewed in (Alfadhli and Barklis, 2014)]. However, these interactions, generally assayed in vitro, are of uncertain significance. To test whether MA binds to RNA in cells, we modified the aforementioned HIV-1NL4-3(MA-3xHA/PR-) clones to include a FXa protease cleavage site immediately N- or C- terminal to the 3xHA-tag (Fig. 6B, S6A). After UV-crosslinking, cell lysates could be treated with FXa protease to generate two Gag fragments (MA and CA-NC-p6) only one of which would be tagged and immunoprecipitated (Fig. 6B, C).

Like full-length Gag, the immunoprecipitated CA-NC-p6 contained crosslinked RNA species that caused adducts to migrate ~0-10kD above the expected molecular weight of the protein. Notably, the isolated MA domain also generated prominent crosslinked species, indicating RNA binding. Unusually, these MA-RNA adducts migrated at a discrete molecular weight of ~35 kD, suggesting that MA bound to a unique RNA species (Fig. 6D).

While the CA-NC-p6-RNA adducts contained viral RNA sequences with a very similar distribution to those recovered from full-length Gag, MA-RNA adducts were nearly devoid of viral RNA-derived sequence (Fig. 6E). In fact, the RNA molecules crosslinked to MA were almost exclusively host tRNAs (Fig. 6F). When RNase treatment was omitted from the CLIP procedure prior to immunoprecipitation, MA-RNA adducts migrated at a larger, but still discrete, molecular weight (Fig. 6D) matching the size of one tRNA molecule (~20 kD) crosslinked to MA, suggesting that MA binds to full-length tRNAs.

While tRNAs constituted the majority of cellular RNA molecules bound by intact Gag in cells, deletion of MA caused a major reduction in the fraction of reads that were tRNA-derived, but did not inhibit binding to mRNAs or 7SL RNA (Fig. 6F, S6B). Conversely, a mutant Gag protein lacking the NC domain did not bind mRNA or 7SL, but bound nearly exclusively to tRNAs (Fig. 6F, S6B). Progressive and specific loss of tRNA binding occurred as more lysines in the N-terminal MA basic domain were substituted, and mutation of six lysines (MAK6T) reduced Gag-tRNA binding to the same degree as deletion of MA (Fig. 6F, S6B). As expected, MAK4T and MAK6T mutations caused decreases in the levels of released particles (Fig. S6B), consistent with a plasma membrane targeting defect in these mutants.

MA-binding to tRNAs was highly selective. Indeed, GluCTC, GluTTC, GlyGCC, GlyCCC, LysCTT, LysTTT, ValAAC and ValCAC tRNAs were bound up to 100-fold more frequently than the majority of tRNAs (Fig. 6G). No such enrichment occurred in CLIP experiments done with GagΔMA. Although intact tRNA molecules were bound by MA (Fig. 6D), binding apparently involved the 5’ half of the tRNA molecules, and especially the dihydrouridine loop, as indicated by the very high rates of T-to-C conversions at this site (Fig. 6H). Binding was not induced by 4SU incorporation into tRNAs, because the same tRNAs were selectively MA-bound in CLIP experiments where crosslinking was induced by UV irradiation at 254nm in the absence of modified nucleotides (Fig. S6C).

Regulation of Gag membrane binding by tRNA

The finding that the same lysine residues that mediate plasma membrane binding also mediate tRNA binding, suggested that tRNAs might regulate Gag localization. Indeed previous work has indicated that exogenous RNA can inhibit Gag binding to liposomes in vitro (Chukkapalli et al., 2013; Chukkapalli et al., 2010; Dick et al., 2013). We took a simple cell-based approach (without addition of exogenous RNA or liposomes) and tested whether RNase treatment of cell lysates increased Gag binding to endogenous cellular membranes. Lysates of HeLa and HOS cells stably expressing Gag-GFP were treated with ribonucleases and subjected to membrane flotation analysis. Strikingly, RNase treatment caused a significant redistribution of Gag from cytosol to membrane fractions (Fig. 7A, B), while a control protein, β-tubulin, was largely unaffected. Consistent with a model in which tRNAs compete with membranes for Gag binding, tRNAs comprised a significantly smaller fraction of Gag-bound RNAs at the plasma membrane than in the cytoplasm (Fig. 7C). This difference was more pronounced when particle budding was blocked at the plasma membrane by deletion of the late budding domain of Gag (Fig. 7C). Thus, these results indicate that MA can bind to tRNA or cell membranes, but not both simultaneously, and strongly suggest that tRNAs regulate Gag localization by binding to basic amino acids in MA.

Figure 7. Reciprocal relationship between HIV-1 Gag binding to RNA and membrane during virion genesis.

(A) Western blot analysis (anti-CA and anti-β-tubulin) of HOS cell lysates, fractionated by membrane flotation after treatment with RNase.

(B) Quantitation of Gag and β-tubulin in the cytosol and membrane fractions from five independent experiments each with HOS and HeLa cells.

(C) Classification of individual reads that map to genes in the host cell genome, from Gag-CLIP experiments done using fractionated cells and WT or mutant Gag proteins as described in Figure 3. Total number of reads is indicated below.

(D) Model summarizing changing interactions between Gag and RNA during virion genesis.

Discussion

Two central conclusions of these studies are (i) the HIV-1 Gag protein has two RNA binding domains (NC and MA) with very different specificities and (ii) dramatic changes in RNA binding regulate Gag localization and genome packaging during virion genesis (Fig. 7D).

Prior to virion assembly, Gag exists as a diffuse pool of monomers or low order multimers in the cytoplasm with its NC domain bound primarily to mRNA, with some binding to 7SL and tRNA (Fig. 7D). A fraction of NC-RNA interactions are with particular sites on the HIV-1 genome, including the Ψ sequence. Our data reveal the specific RNA sequences within Ψ that are in proximity to Gag, in a physiological setting. Satisfyingly, the three noncontiguous RNA elements that are most frequently crosslinked to Gag (nucleotides ~100-126, 195-260 and 300-350) coincide nearly precisely with a minimal Ψ element, which adopts a secondary structure that putatively favors genome packaging (Lu et al., 2011a).

Surprisingly, cytoplasmic Gag bound to additional discrete elements on the viral RNA, including RRE. Previously, env sequences, including RRE, were shown to facilitate packaging (Kaye et al., 1995; Richardson et al., 1993), but a discrete packaging sequence within env could not be mapped. Other reports suggest that Rev enhances packaging (Brandt et al., 2007), although effects of Rev/RRE on viral RNA nuclear export are potential confounders in packaging experiments. Despite strong evidence for Gag-RRE binding, the RRE did not affect infectious virion yield when its nuclear export function was replaced, suggesting that Gag-RRE binding is not required for genome packaging. While it is possible that Gag/NC-RRE interaction plays a redundant role in packaging, other plausible functions include (i) shielding double stranded stem I RNA from cytoplasmic sensors, (ii) coupling RNA-export with packaging, (iii) displacement of Rev from the RRE for recycling, (iv) regulation of Env translation and (v) enhancement of reverse transcription via NC's unwinding/chaperone function (Levin et al., 2010). Further work will be required to elucidate the functional role, if any, of Gag/NC-RRE binding.

In the cytosol, Gag favored binding to the viral genome over cellular mRNAs by a few fold. This level of discrimination is insufficient to account for the selectivity with which viral genomes are packaged. Our data indicate that a dramatic change in Gag-RNA binding specificity, coincident with CA-CTD-dependent high-order multimerization at the plasma membrane contributes to selective packaging (Fig. 7D). GU-rich sequences in cellular mRNA were targeted by Gag in the cytosol, consistent with previous in vitro and structural studies indicating that the isolated, monomeric NC domain favors binding to such sequences (Berglund et al., 1997; De Guzman et al., 1998; Fisher et al., 1998). However, during assembly, Gag molecules become tightly packed in hexameric lattices (Briggs et al., 2009; Wright et al., 2007). By constraining thousands of NC domains into a pseudo-2-dimensional curved array, local NC concentration is dramatically elevated. Potentially, features of NC that govern RNA binding specificity (zinc knuckles and basic amino-acids) might be differently accessible in an assembled Gag lattice. Under these conditions, we found that A-rich mRNA sequences were preferentially bound by Gag (Fig. 7D). Remarkably, the nucleotide composition of mRNA sequences bound by assembled Gag reflects an unusual, heretofore unexplained, property of the HIV-1 genome. Thus, our findings suggest that a need to selectively package viral RNA caused HIV-1 to evolve an unusually A-rich genome. Conversely, an A-rich genome may have evolved for other reasons which then drove Gag to gain a unique oligomerization-driven specificity for A-rich RNA. Notably, Ψ-deletion caused only a 3-fold reduction in the fraction of virion-associated, Gag-bound, RNA sequences that were viral RNA derived. Moreover the pattern of Gag binding to many sites in the viral genome was not solely a secondary effect of physical proximity to Gag - Ψ interactions. Rather it appears that HIV-1 genome packaging is a two-step process, involving interactions between (i) Ψ and monomeric Gag and (ii) A-rich viral RNA and multimeric Gag. This scenario should selectively drive particle assembly on viral RNAs and we speculate that the biases in nucleotide composition exhibited by HIV-1 and other retroviruses serves as a proofreading-like mechanism to enhance the fidelity of genome packaging following initial Gag-Ψ interaction.

An unexpected finding was that proteolytic cleavage of Gag caused NC to revert to a preference for GU-rich mRNAs and discrete viral RNA sequences. This result reinforces the notion that Gag/NC RNA binding specificity is multimerization dependent. By liberating the majority of viral RNA from NC, while maintaining interaction with structured elements (to enable NC's chaperone activity) maturation dependent changes in Gag/NC-RNA binding could facilitate reverse transcription (Levin et al., 2010).

Another surprising finding was that MA binding to specific tRNAs constitutes the most frequent binding events between Gag and RNA in cells. MA-tRNA binding was independent of NC and the PBS and is thus unlikely to involve the tRNA primer annealed to viral genome. Rather, we found that MA-tRNA interaction could regulate the binding of Gag to cellular membranes. MA specifies the location of virion assembly and it was previously shown that RNA can block in vitro MA binding specifically to liposomes that lack acidic phospholipids (Chukkapalli et al., 2013; Chukkapalli et al., 2010). Thus, occlusion of MA basic residues by specific tRNAs might inhibit nonproductive assembly at most intracellular membranes, and facilitate targeting to the plasma membrane where resident lipids have a high affinity for MA. Alternatively, MA-tRNA binding might provide a mechanism by which virion assembly is temporally regulated.

MA-tRNA interactions could serve additional purposes. Some degree of RNA binding may be an inevitable consequence of encoding a highly basic domain. Thus, specific MA binding in a 1:1 complex to small RNAs might be a mechanism to avoid the aggregation of a protein that has both two distinct RNA binding domains and a tendency to multimerize. MA-tRNA binding might also prevent nonproductive interaction of a viral genome with a Gag monomer whose NC domain has engaged viral RNA. Conceivably, MA may facilitate the selection of the RT primer, as tRNAlys3 is among the tRNAs bound by MA, but several other tRNAs are also bound by MA more frequently. Finally, MA-tRNA interaction could regulate viral and/or host translation. The A-richness of the HIV-1 genome results in suboptimal codon usage (Grantham and Perrin, 1986; Kypr and Mrazek, 1987; Sharp, 1986) and an elevated number of Ile, Lys, Glu and Val codons in the Gag and Pol ORFs (Berkhout and van Hemert, 1994). Notably, Lys, Glu and Val tRNAs are among those specifically bound by MA, providing a potential opportunity for Gag to regulate its own translation as it accumulates to high levels and sequesters tRNAs (perhaps facilitating packaging as a consequence). Similarly, MA could inhibit translation of host mRNAs whose products may be deleterious for viral replication. Indeed, interaction of MA with host elongation factors via a tRNA bridge has been reported to inhibit translation in vitro (Cimarelli and Luban, 1999).

Overall, our global survey reveals surprising ways in which the interaction between Gag, viral and host RNAs can change and modulate the process of virion genesis and genome packaging.

Experimental Procedures

Proviral plasmids and cells

HIV-1NL4-3-derived proviral plasmids containing a 3xHA tag in the stalk region of matrix (HIV-1NL4-3MA-3xHA) were constructed using overlap extension PCR. Various derivatives of this construct encoding a catalytically inactive viral protease (PR-), a Factor Xa cleavage sites on ether side of the HA tag (MA-FXa-3xHA and MA-3xHA-FXa), deletions of nucleocapsid domain (ΔNC), the globular head of MA (ΔMA), the CA CTD (CA ΔCTD), or the Ψ signal (Δ105-278 and Δ105-278/Δ301-332) were constructed using PCR-based deletion mutagenesis. Constructs carrying mutations at binding sites for Tsg101 and ALIX proteins in the p6 domain of Gag (Δp6), the Gag myristoylation signal (G2A), or at lysine residues in MA (MAK26,27T MAK4T and MAK6T) were constructed using PCR overlap extension based mutagenesis. Proviral plasmids with deletions or mutations in Env, Rev, and RRE and encoding a Mason-Pfizer monkey virus constitutive transport element were similarly constructed. Details of the construction are described in Extended Experimental Procedures.

PAR-CLIP, HITS-CLIP and RNA-seq

For CLIP experiments, HEK293T cells were grown in 10-cm dishes and transfected with proviral plasmids using polyethylenimine (PolySciences). Virions were harvested from filtered supernatant by ultracentrifugation through sucrose and UV-irradiated, while cells were irradiated while adhered to culture dishes. Prior to UV-crosslinking, a fraction of cells and virions were collected for RNA-seq analysis. After crosslinking, the CLIP procedure was performed on unfractionated lysates (after removal of nuclei) or on membrane and cytoplasmic fractions.

For the CLIP procedure, cell and virion lysates were treated with RNaseA or RNAseT1 and then incubated with Protein G-conjugated Dynabeads coated with anti-HA or anti-NC antibodies. After immunoprecipitation of RNA-protein adducts, beads were washed and treated sequentially with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase and then polynucleotide kinase and γ-32P-ATP. RNA-protein adducts were eluted from the beads, separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted onto nitrocellulose and digested with proteinase K. RNA oligonucleotides were then ligated to adapters, amplified by PCR and sequences determined using a Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform. CLIP-seq experiments were performed two to six times on cells and virions. Further details of the method are in the Extended Experimental Procedures.

Bioinformatic analyses

The FASTX toolkit was used to process the reads from CLIP and RNA-seq libraries before mapping. Reads were separated based on their 5’ barcode sequences and collapsed to generate a set of unique sequences. Unique CLIP-seq and RNA-seq reads were mapped to the human (hg19) and HIV-1 genomes using the Bowtie. SAMtools, in house scripts and Graphpad Prism were used to calculate and display read densities associated with viral and cellular RNAs and to calculate correlations. Clusters were generated using PARalyzer and used as an input for the cERMIT motif finding tool. Further details are given in the Extended Experimental Procedures.

Membrane flotation assays

The membrane flotation assays were performed using HeLa and HOS cells stably expressing cyan fluorescent protein-tagged Gag proteins as described (Kutluay and Bieniasz, 2010) with modifications outlined in the Extended Experimental Procedures.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Cytoplasmic HIV-1 Gag binds GU-rich RNA and discrete elements within Ψ and RRE.

Assembly induces a transient change in Gag-RNA binding specificity to A-rich motifs.

The matrix domain of Gag binds to specific tRNAs, not viral RNA.

Matrix-tRNA binding regulates Gag binding to cell membranes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Markus Hafner and members of the Darnell and Tuschl labs for advice and helpful discussions. We thank Michael Summers for the diagram of the Ψ sequence in Fig. 2. S.B.K. was supported in part by an AmFAR Mathilde Krim Postdoctoral Fellowship. This work was supported by NIH grants R01AI501111 and P50GM103297.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

S.B.K. and P.D.B. conceived the study, designed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the paper. S.B.K., T.Z., C.P. and D.J. executed the experiments. S.B.K., D.B.M and M.E. analyzed the sequencing data. P.D.B. supervised the work.

References

- Aldovini A, Young RA. Mutations of RNA and protein sequences involved in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 packaging result in production of noninfectious virus. J Virol. 1990;64:1920–1926. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.5.1920-1926.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfadhli A, Barklis E. The roles of lipids and nucleic acids in HIV-1 assembly. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:253. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfadhli A, Still A, Barklis E. Analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix binding to membranes and nucleic acids. J Virol. 2009;83:12196–12203. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01197-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell NM, Lever AM. HIV Gag polyprotein: processing and early viral particle assembly. Trends Microbiol. 2013;21:136–144. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglund JA, Charpentier B, Rosbash M. A high affinity binding site for the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1042–1049. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkhout B, van Hemert FJ. The unusual nucleotide content of the HIV RNA genome results in a biased amino acid composition of HIV proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1705–1711. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.9.1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz RD, Hammarskjold ML, Helga-Maria C, Rekosh D, Goff SP. 5′ regions of HIV-1 RNAs are not sufficient for encapsidation: implications for the HIV-1 packaging signal. Virology. 1995;212:718–723. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz RD, Luban J, Goff SP. Specific binding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag polyprotein and nucleocapsid protein to viral RNAs detected by RNA mobility shift assays. J Virol. 1993;67:7190–7200. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7190-7200.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt S, Blissenbach M, Grewe B, Konietzny R, Grunwald T, Uberla K. Rev proteins of human and simian immunodeficiency virus enhance RNA encapsidation. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e54. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs JA, Riches JD, Glass B, Bartonova V, Zanetti G, Krausslich HG. Structure and assembly of immature HIV. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11090–11095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903535106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamanian M, Purzycka KJ, Wille PT, Ha JS, McDonald D, Gao Y, Le Grice SF, Arts EJ. A cis-acting element in retroviral genomic RNA links Gag-Pol ribosomal frameshifting to selective viral RNA encapsidation. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chukkapalli V, Inlora J, Todd GC, Ono A. Evidence in support of RNA-mediated inhibition of phosphatidylserine-dependent HIV-1 Gag membrane binding in cells. J Virol. 2013;87:7155–7159. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00075-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chukkapalli V, Oh SJ, Ono A. Opposing mechanisms involving RNA and lipids regulate HIV-1 Gag membrane binding through the highly basic region of the matrix domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:1600–1605. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908661107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimarelli A, Luban J. Translation elongation factor 1-alpha interacts specifically with the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag polyprotein. J Virol. 1999;73:5388–5401. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5388-5401.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clavel F, Orenstein JM. A mutant of human immunodeficiency virus with reduced RNA packaging and abnormal particle morphology. J Virol. 1990;64:5230–5234. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.10.5230-5234.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clever J, Sassetti C, Parslow TG. RNA secondary structure and binding sites for gag gene products in the 5′ packaging signal of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1995;69:2101–2109. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2101-2109.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clever JL, Parslow TG. Mutant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomes with defects in RNA dimerization or encapsidation. J Virol. 1997;71:3407–3414. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3407-3414.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran DL, Georgiev S, Mukherjee N, Gottwein E, Skalsky RL, Keene JD, Ohler U. PARalyzer: definition of RNA binding sites from PAR-CLIP short-read sequence data. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R79. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-8-r79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das AT, Klaver B, Klasens BI, van Wamel JL, Berkhout B. A conserved hairpin motif in the R-U5 region of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA genome is essential for replication. J Virol. 1997;71:2346–2356. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2346-2356.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Guzman RN, Wu ZR, Stalling CC, Pappalardo L, Borer PN, Summers MF. Structure of the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein bound to the SL3 psi-RNA recognition element. Science. 1998;279:384–388. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick RA, Kamynina E, Vogt VM. Effect of multimerization on membrane association of Rous sarcoma virus and HIV-1 matrix domain proteins. J Virol. 2013;87:13598–13608. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01659-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RJ, Rein A, Fivash M, Urbaneja MA, Casas-Finet JR, Medaglia M, Henderson LE. Sequence-specific binding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein to short oligonucleotides. J Virol. 1998;72:1902–1909. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.1902-1909.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiev S, Boyle AP, Jayasurya K, Ding X, Mukherjee S, Ohler U. Evidence-ranked motif identification. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R19. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick RJ, Nigida SM, Jr., Bess JW, Jr., Arthur LO, Henderson LE, Rein A. Noninfectious human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mutants deficient in genomic RNA. J Virol. 1990;64:3207–3211. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.7.3207-3211.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grantham P, Perrin P. AIDS virus and HTLV-I differ in codon choices. Nature. 1986;319:727–728. doi: 10.1038/319727b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner M, Landthaler M, Burger L, Khorshid M, Hausser J, Berninger P, Rothballer A, Ascano M, Jr., Jungkamp AC, Munschauer M, et al. Transcriptome-wide identification of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell. 2010;141:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison GP, Lever AM. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 packaging signal and major splice donor region have a conserved stable secondary structure. J Virol. 1992;66:4144–4153. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.4144-4153.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill CP, Worthylake D, Bancroft DP, Christensen AM, Sundquist WI. Crystal structures of the trimeric human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein: implications for membrane association and assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:3099–3104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houzet L, Paillart JC, Smagulova F, Maurel S, Morichaud Z, Marquet R, Mougel M. HIV controls the selective packaging of genomic, spliced viral and cellular RNAs into virions through different mechanisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:2695–2704. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouvenet N, Simon SM, Bieniasz PD. Imaging the interaction of HIV-1 genomes and Gag during assembly of individual viral particles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19114–19119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907364106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye JF, Richardson JH, Lever AM. cis-acting sequences involved in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA packaging. J Virol. 1995;69:6588–6592. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6588-6592.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutluay SB, Bieniasz PD. Analysis of the initiating events in HIV-1 particle assembly and genome packaging. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001200. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzembayeva M, Dilley K, Sardo L, Hu WS. Life of psi: how full-length HIV-1 RNAs become packaged genomes in the viral particles. Virology 454. 2014;455:362–370. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypr J, Mrazek J. Unusual codon usage of HIV. Nature. 1987;327:20. doi: 10.1038/327020a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laham-Karam N, Bacharach E. Transduction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vectors lacking encapsidation and dimerization signals. J Virol. 2007;81:10687–10698. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00653-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lever A, Gottlinger H, Haseltine W, Sodroski J. Identification of a sequence required for efficient packaging of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA into virions. J Virol. 1989;63:4085–4087. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.9.4085-4087.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin JG, Mitra M, Mascarenhas A, Musier-Forsyth K. Role of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein in HIV-1 reverse transcription. RNA biology. 2010;7:754–774. doi: 10.4161/rna.7.6.14115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licatalosi DD, Mele A, Fak JJ, Ule J, Kayikci M, Chi SW, Clark TA, Schweitzer AC, Blume JE, Wang X, et al. HITS-CLIP yields genome-wide insights into brain alternative RNA processing. Nature. 2008;456:464–469. doi: 10.1038/nature07488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K, Heng X, Garyu L, Monti S, Garcia EL, Kharytonchyk S, Dorjsuren B, Kulandaivel G, Jones S, Hiremath A, et al. NMR detection of structures in the HIV-1 5′-leader RNA that regulate genome packaging. Science. 2011a;334:242–245. doi: 10.1126/science.1210460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K, Heng X, Summers MF. Structural determinants and mechanism of HIV-1 genome packaging. J Mol Biol. 2011b;410:609–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luban J, Goff SP. Mutational analysis of cis-acting packaging signals in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA. J Virol. 1994;68:3784–3793. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3784-3793.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malim MH, Tiley LS, McCarn DF, Rusche JR, Hauber J, Cullen BR. HIV-1 structural gene expression requires binding of the Rev trans-activator to its RNA target sequence. Cell. 1990;60:675–683. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90670-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride MS, Panganiban AT. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 encapsidation site is a multipartite RNA element composed of functional hairpin structures. J Virol. 1996;70:2963–2973. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2963-2973.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride MS, Panganiban AT. Position dependence of functional hairpins important for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA encapsidation in vivo. J Virol. 1997;71:2050–2058. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2050-2058.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride MS, Schwartz MD, Panganiban AT. Efficient encapsidation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vectors and further characterization of cis elements required for encapsidation. J Virol. 1997;71:4544–4554. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4544-4554.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muriaux D, Mirro J, Harvin D, Rein A. RNA is a structural element in retrovirus particles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5246–5251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091000398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onafuwa-Nuga AA, Telesnitsky A, King SR. 7SL RNA, but not the 54-kd signal recognition particle protein, is an abundant component of both infectious HIV-1 and minimal virus-like particles. RNA. 2006;12:542–546. doi: 10.1261/rna.2306306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott DE, Coren LV, Gagliardi TD. Redundant roles for nucleocapsid and matrix RNA-binding sequences in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 assembly. J Virol. 2005;79:13839–13847. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.13839-13847.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramalingam D, Duclair S, Datta SA, Ellington A, Rein A, Prasad VR. RNA aptamers directed to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag polyprotein bind to the matrix and nucleocapsid domains and inhibit virus production. J Virol. 2011;85:305–314. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02626-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rein A, Datta SA, Jones CP, Musier-Forsyth K. Diverse interactions of retroviral Gag proteins with RNAs. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson JH, Child LA, Lever AM. Packaging of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA requires cis-acting sequences outside the 5′ leader region. J Virol. 1993;67:3997–4005. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.3997-4005.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rulli SJ, Jr., Hibbert CS, Mirro J, Pederson T, Biswal S, Rein A. Selective and nonselective packaging of cellular RNAs in retrovirus particles. J Virol. 2007;81:6623–6631. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02833-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell RS, Hu J, Beriault V, Mouland AJ, Laughrea M, Kleiman L, Wainberg MA, Liang C. Sequences downstream of the 5′ splice donor site are required for both packaging and dimerization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA. J Virol. 2003;77:84–96. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.1.84-96.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saad JS, Miller J, Tai J, Kim A, Ghanam RH, Summers MF. Structural basis for targeting HIV-1 Gag proteins to the plasma membrane for virus assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11364–11369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602818103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp PM. What can AIDS virus codon usage tell us? Nature. 1986;324:114. doi: 10.1038/324114a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shkriabai N, Datta SA, Zhao Z, Hess S, Rein A, Kvaratskhelia M. Interactions of HIV-1 Gag with assembly cofactors. Biochemistry. 2006;45:4077–4083. doi: 10.1021/bi052308e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundquist WI, Krausslich HG. HIV-1 assembly, budding, and maturation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a006924. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright ER, Schooler JB, Ding HJ, Kieffer C, Fillmore C, Sundquist WI, Jensen GJ. Electron cryotomography of immature HIV-1 virions reveals the structure of the CA and SP1 Gag shells. EMBO J. 2007;26:2218–2226. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Parent LJ, Wills JW, Resh MD. Identification of a membrane-binding domain within the amino-terminal region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein which interacts with acidic phospholipids. J Virol. 1994;68:2556–2569. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2556-2569.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.