Abstract

• Background and Aims The generic delimitations of Ficinia and Isolepis, sister genera in the Cypereae, are blurred. Typical Ficinia flowers have a lobed gynophore, which envelops the base of the nutlet, whereas in Isolepis the character is considered to be absent. Some former species of Isolepis, lacking the gynophore, were recently included in Ficinia. The floral ontogeny of representative taxa in Ficinia and Isolepis were investigated with the aim of evaluating the origin and nature of the gynophore in the Cypereae.

• Methods The spikelet and floral ontogeny in inflorescences collected in the field was investigated using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and light microscopy (LM).

• Key Results SEM images of Isolepis setacea and I. antarctica, Ficinia brevifolia, F. minutiflora, F. zeyheri and F. gracilis, and LM sections of F. radiata, show that the gynoecium in Ficinia is elevated above the flower receptacle by the development of a hypogynous stalk. From its apex, a (often three-)lobed cup is formed, which envelopes the basal part of the later nutlet. In developing flowers of I. antarctica, a rudimentary hypogynous stalk appears. In I. setacea, rudiments of a hypogynous stalk can be observed at maturity. In F. radiata and F. zeyheri, intralocular hairs are present in the micropylar zone. At the surface of developing gynoecia in flowers of F. gracilis, star-shaped cuticular structures appear which disappear again at maturity.

• Conclusions The overall floral ontogeny of all species studied occurs following a typical scirpoid pattern, though no perianth primordia are formed. The gynophore in Ficinia originates as a hypogynous stalk, from which the typical gynophore lobes develop. The gynophore is not homologous with the perianth.

Keywords: Ficinia, floral ontogeny, gynophore, Isolepis, scanning electron microscopy

INTRODUCTION

Ficinia Schrad. and Isolepis R.Br. are closely related genera that have been classified in the tribe Cypereae, mainly based on the Ficinia variant of the Cyperus-type embryo morphology and on the absence of a perianth in the flowers (Haines and Lye, 1983; Goetghebeur, 1998). In phylogenetic studies of the Cyperaceae subfamily Cyperoideae, the Cypereae are resolved into two clades, one clade comprising Cyperus and allied genera that is sister to a Hellmuthia–Scirpoides–Isolepis–Ficinia clade (Muasya et al., 1998, 2001; Simpson et al., 2005). Ficinia and Isolepis are most diverse in the Cape Floristic Region in South Africa. Just a handful of species of Ficinia occur in afro-alpine habitats of Eastern Africa and one species is subantarctic circumpolar. Isolepis, however, is also diversified in Australasia and South America, tropical alpine mountains and northern temperate areas. Isolepis comprises about 70 species of annuals or short-lived perennials, lacking both leaf ligule and gynophore (Muasya and Simpson, 2002). On the other hand, the ±60 species of Ficinia are mostly perennials, sharing the presence of a membranous leaf sheath prolonged into a ligule, and presence of a gynophore (Arnold and Gordon-Gray, 1982). The gynophore in Ficinia, also called ‘hypogynous disc’, is characterized by a (three-)lobed outgrowth surrounding the base of the ovary (Goetghebeur, 1986). Variation in morphology of the gynophore has been used to distinguish between species (Arnold and Gordon-Gray, 1982). However, some Ficinia species are annual to short-lived perennials that lack the ligule as well as the gynophore, thereby obscuring the current concepts of the genera (Muasya et al., 2000, 2001; Muasya and Simpson, 2002).

Floral ontogenetic studies in Cyperaceae are uncommon. Mora (1960) published a floral (spikelet) ontogenetic study of Scirpoides holoschoenus (then known as Scirpus holoschoenus). Other recent ontogenetic studies on the Cyperoideae include works on Lepidosperma Labill. and Schoenoplectus (Reichb.) Palla (Bruhl, 1991), Cladium P.Browne (Richards, 2002; Vrijdaghs et al., 2003), Eleocharis R.BR., Fuirena Rottb. (Vrijdaghs et al., 2004), Scirpus L., Dulichium Rich., Eriophorum L. and Scirpoides Scheuzer ex Séguier (Vrijdaghs et al., 2005a) and Schoenus L. (Vrijdaghs et al., 2005b). In this study, the floral and spikelet ontogenetic patterns in Ficinia and Isolepis is investigated using SEM and LM techniques, with the aim to understand the origin and nature of the gynophore in Ficinia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Material was selected representing the diverse morphology observed in Ficinia (F. brevifolia Nees ex Kunth, F. gracilis Schrad., F. minutiflora C.B.Clarke, F. radiata (L.f.) Kunth and F. zeyheri Boeck). In Isolepis, a typical species, I. setacea (L.) R.Br., and the atypical (lacking ligule and having a rudimentary hypogynous stalk) species I. antarctica (L.) Roem. & Schult were chosen. Partial inflorescences of the species studied were collected in the field (Table 1) and preserved in FAA (70 % ethanol, acetic acid, 40 % formaldehyde, 90 : 5 : 5). Floral buds were dissected in 70 % ethanol under a Wild M3 (Leica Microsystems AG, Wetzlar, Germany) stereo microscope equipped with a cold-light source (Schott KL1500; Schott-Fostec LLC, Auburn, NY, USA).

Table 1.

Species of Cyperaceae studied and voucher data

| Taxa |

Origin |

Voucher |

|---|---|---|

| Cyperus haspan L. (Fig. 12F–H) | Kenya | Muasya 2135 (EA) |

| Ficinia brevifolia Nees ex Kunth | South Africa | Muasya 2205 (BOL, EA, K) |

| Ficinia capitella (Thunb.) Nees | South Africa | Muasya 2206 (EA) |

| Ficinia gracilis Schrad. (Fig. 8I) | South Africa | Acocks 19146 (K) |

| Ficinia gracilis Schrad. | South Africa | Muasya 2248 (BOL, EA, K) |

| Ficinia minutiflora C.B.Clarke | South Africa | Muasya 2257 (BOL, EA, K) |

| Ficinia radiata (L.f.) Kunth | South Africa | Muasya 2262 (BOL, EA, K) |

| Ficinia zeyheri Boeck | South Africa | Muasya 2209 (BOL, EA, K) |

| Isolepis antarctica (L.) Roem. & Schult. | South Africa | Muasya 2247 (BOL, EA, K) |

| Isolepis setacea (L.) R.Br. | Kenya | Muasya 2558 (EA) |

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The material was washed twice with 70 % ethanol for 5 min and then placed in a mixture (1 : 1) of 70 % ethanol and DMM (dimethoxymethane) for 20 min. Subsequently, the material was transferred to 100 % DMM for 20 min, before it was CO2 critical point dried using a CPD 030 critical point dryer (BAL-TEC AG, Balzers, Liechtenstein). The dried samples were mounted on aluminium stubs using Leit-C and coated with gold with a SPI-Module™ Sputter Coater (SPI Supplies, West-Chester, PA, USA). Images were obtained on a Jeol JSM-6360 (Jeol, Tokyo) at the Laboratory of Plant Systematics (K.U. Leuven), and on a Jeol JSM-5800 LV (Jeol, Tokyo) scanning electron microscope at the National Botanic Garden of Belgium in Meise.

Light microscopy (LM)

The prepared material was dehydrated through a t-butyl alcohol series to be embedded in paraffin. Transverse and longitudinal serial sections (Microm HM360, Prosan, Belgium) were cut at 7 µm and stained with saffranin in 70 % ethanol and anilin blue in an automatic staining machine Varistain 24-3 (Shandon, Runcorn, UK) and were mounted with Eukitt.

Prepared developing gynoecia of Ficinia gracilis were dehydrated through an ethanol series, and subsequently embedded using the Technovit 7100 kit (Heraeus, Germany). The samples were cut with a rotation microtome (Microm HM360) equipped with a tungsten carbide knife. The 3-µm sections were fixed on a slide using Haupt Adhesiv, and stretched overnight at 65 °C. Subsequently the sections were stained with toluidine blue solution (0.1 g per 100 ml distilled water).

LM images were observed with a Leitz Dialux 20 microscope and digital photographs were made with an Olympus DP50 camera.

RESULTS

The floral ontogeny in Ficinia minutiflora C.B.Clarke

The spikelet of F. minutiflora consists of an indeterminate rachilla, and many spirally arranged glumes, each subtending a bisexual flower (Fig. 1A). Additional glumes originate below the spikelet apex, forming a rim-like primordium (Fig. 1A). The spikelet apex is protected by bonnet-like glumes of lower flowers (Fig. 1B). Very soon after the formation of the glume primordium, a flower primordium appears in its axil (Fig. 1C). With the glume developing, the flower primordium expands laterally, forming two lateral stamen primordia (Fig. 1D), followed with some delay by a third, abaxial one (Fig. 1E). Meanwhile, on the top of the flower primordium, a gynoecium primordium is formed (Fig. 1D and E). Next, the gynoecium primordium starts differentiating into an annular ovary primordium, surrounding a central ovule primordium (Fig. 1F). The ovary primordium grows up from the base, enveloping the central ovule, and on its top three stigma primordia originate (Fig. 1G). At later stages, a single style without a distinct style base is formed (Fig. 2C–E). From its origin, the gynoecium primordium stands on a dome-like hypogynous stalk, which surrounds the base of the gynoecium while increasing in size (Figs 1G–L and 2B–F). In between the stamens, the hypogynous stalk is broadened (Fig. 1J–L). At later stages, the hypogynous stalk forms three poorly differentiated lobes around the base of the ovary, which alternate with the stamens (Figs 1L and 2F). At this stage, the ovule primordium has become a basal, anatropous ovule positioned upon the gynophore (Fig. 1L). Meanwhile, the stamen primordia develop fast into introrse, basifixed stamens with long anthers with longitudinal slits (Fig. 2A, B and D). A delay in the development of the gynoecium may occur (Fig. 2A). In well-developed stamens, the bases of the pollen sacs become papillose (Fig. 2A). At the top of the anthers the connective develops into a blunt connective crest or apiculus (Fig. 2G). The three stigma primordia become long and papillose (Fig. 2E). A mature ovary has a base enveloped by the three lobes of the gynophore, and papillose cells in its apical half (Fig. 2F).

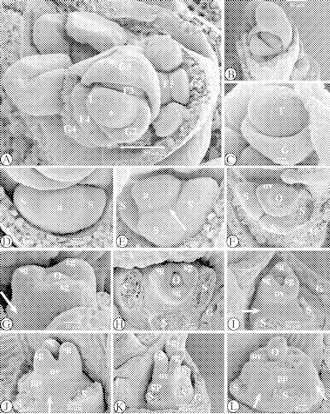

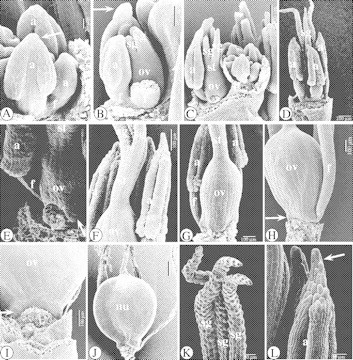

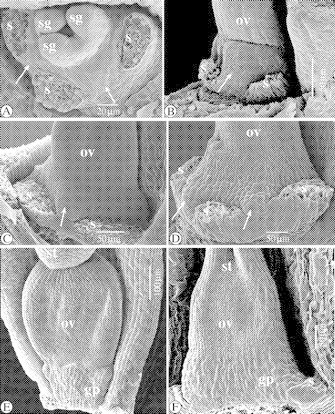

Fig. 1.

SEM images of the floral ontogeny in Ficinia minutiflora. (A) Apical view of the rachilla apex with spirally placed glumes, each subtending one out of five successive early stages of floral development, numbered 1–5. At stage ‘2’, a glume becomes apparent as a rim-like structure. (B) Lateral view of the spikelet apex, with a developing flower primordium, and the rachilla apex hidden by the bonnet-like glume of a lower flower. (C) Flower primordium in the axil of the subtending glume. (D) Apical view of a developing flower primordium; two lateral stamen primordia appear, as well as an apical gynoecium primordium. (E) Lateral-abaxial view; the abaxial stamen primordium has appeared, and the gynoecium primordium is raised by the formation of a hypogynous stalk (arrowed). (F) Apical view. One developing stamen primordium has been removed. The gynoecium primordium differentiated into an annular ovary primordium surrounding a central ovule. (G) Lateral view of the developing gynoecium, with hypogynous stalk (arrowed). Appearance of the stigma primordia. (H) Apical view of the developing flower. The three stamens have been removed. (I) Lateral view of the developing gynoecium, with conical hypogynous stalk (arrowed). (J) Alternating with the three (removed) stamens, the hypogynous stalk is broadened (arrowed). (K) Lateral view of the developing gynoecium. The stigma primordia are growing out. The stamens have been removed. (L) Hypogynous stalk and basal part of the ovary. Stamens and ovary wall were removed. The anatropous central ovule is positioned above the hypogynous stalk. In between the stamens, the hypogynous stalk is broadened (arrowed). Abbreviations: F, flower primordium; G, glume; g, gynoecium (primordium); gp, gynophore; o, ovule (primordium); ov, ovary (primordium); s, stamen (primordium); sg, stigma (primordium); st, style; *, rachilla apex.

Fig. 2.

SEM images of the floral ontogeny in Ficinia minutiflora. (A) Adaxial view of a developing flower with well-developed stamens, with bases of pollen sacs becoming slightly papillose. There is a conical hypogynous stalk (arrowed). (B) Lateral-adaxial view. Filaments of stamens are lengthening. Notice the conical hypogynous stalk (arrowed). (C) Lateral-adaxial view. The gynophore is forming a rim (arrowed) around the base of the ovary. (D) Abaxial view of a nearly mature flower, with the abaxial and one lateral stamen removed. The stigmas are becoming papillose, and the filament (arrowed) of the remaining stamen protrudes above the gynoecium. (E) Adaxial view of a semi-mature flower. (F) Lateral view of the basal part of a mature flower. Three gynophore lobes alternate with the stamens. (G) Blunt connective crests. Abbreviations: a, anther; f, filament; gp, gynophore; gpl, gynophore lobe; o, ovule (primordium); ov, ovary (primordium); s, stamen; sg, stigma (primordium); st, style.

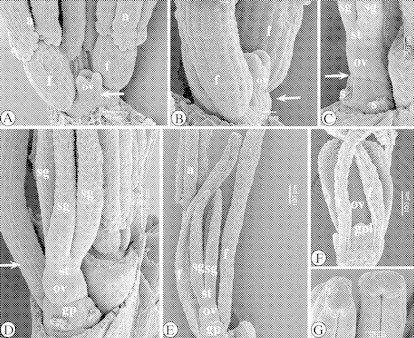

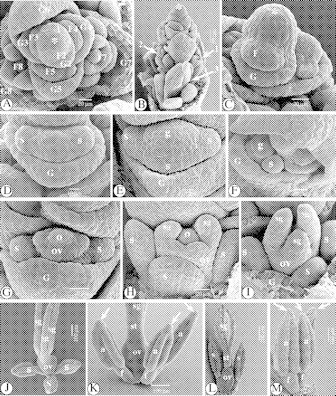

Fig. 3.

SEM images of the floral ontogeny in Ficinia brevifolia. (A) Apical view of a rachilla apex, with spirally placed glumes, each subtending one out of four successive early stages in floral development (numbered 1–5). At stage ‘1’, a new glume primordium originates. ‘G2’ is a developing rim-like glume primordium. At stage ‘5’, a flower primordium (F5) is visible. (B) Abaxial view of a flower primordium. Two lateral stamen primordia have been formed, as well as an apical gynoecium primordium on a hypogynous stalk (arrowed). (C) Lateral view of developing gynoecium, one lateral and the abaxial stamen have been removed. (D) Lateral view of developing gynoecium, with one lateral and the abaxial stamen removed. The stigma primordia are growing out. The hypogynous stalk is arrowed. (E) Detail of the adaxial basal part of the ovary. The hypogynous stalk is forming a rim around the base of the ovary (arrowed). (F) Gynophore lobes originate from the rim between ovary and gynophore (arrowed). (G) Adaxial view of a nearly mature flower. (H) Adaxial view of a nearly mature flower, with prolonged style. Abbreviations: a, anther; f, filament; F, flower primordium; G, glume; g, gynoecium (primordium); gp, gynophore; ov, ovary (primordium); s, stamen (primordium); sg, stigma (primordium); st, style; *, rachilla apex.

Floral ontogenetic stages in Ficinia brevifolia Nees ex Kunth

The spikelet of F. brevifolia is indeterminate, with spiro-tristichously arranged glumes (Fig. 3A). Each glume subtends a bisexual flower. Additional glumes originate laterally below the rachilla apex, as a rim-like structure (Fig. 3A), in which a flower primordium appears soon (Fig. 3A). Subsequently, two lateral stamen primordia are formed (Fig. 3B), followed with some delay by a third one (Fig. 3C). Meanwhile, on the top of the flower primordium, a gynoecium primordium originates (Fig. 3B). The staminal primordia develop fast into typical cyperoid basifixed, introrse stamens with elongated anthers with longitudinal slits (Fig. 3G and H). The gynoecium primordium develops in a similar way as in Ficinia minutiflora, differentiating in a basal ovule, surrounded by an ovary wall with three stigma primordia (Fig. 3C), which grow out into long papillose stigmas (Figs 3G and 4F). Very early in the development of the gynoecium, a gynophore becomes apparent (Fig. 3D). The growing ovary wall forms a single style without a distinct style base (Fig. 3D, G and H). Simultaneously, the hypogynous stalk develops outgrowths at the base of the ovary, alternating with the stamens (Figs 3E–H and 4A–D). In a nearly mature flower, the filaments and anthers elongate, so that eventually the filaments protrude above the ovary (Fig. 4A–C). Meanwhile, the bases of the pollen sacs become papillose (Fig. 4A and B), and a connective crest appears (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

SEM images of the floral ontogeny in Ficinia brevifolia. (A) Detail of the basal part of a nearly mature flower. The bases of the pollen sacs are slightly papillose. Gynophore lobes are originating (arrowed). (B) Abaxial view of a nearly mature flower, with the abaxial stamen partially removed. (C) Mature flower with distinctive gynophore lobes enveloping the base of the ovary. The gynophore lobes alternate with the stamens. (D) Detail of a gynophore lobe. (E) Detail of an apiculus. (F) Detail of mature stigmas. Abbreviations: a, anther; f, filament; gp, gynophore; gpl, gynophore lobe; ov, ovary (primordium); st, style.

The floral ontogeny in Ficinia zeyheri Boeck

The spikelet in F. zeyheri consists an indeterminate rachilla, on which many spirally placed glumes originate successively, laterally below the rachilla apex (Fig. 5A and B). In the axil of a new glume, a flower primordium is formed, which subsequently expands, forming two lateral stamen primordia (Fig. 5A). A third, abaxial stamen primordium originates (Fig. 5B), following the appearance of the gynoecium primordium on the top of the flower primordium. The stamen primordia develop fast, the abaxial one with some delay (Fig. 5C). Meanwhile, the gynoecium primordium has differentiated into an ovary wall, surrounding a central ovule. The ovary wall grows up from its base, enveloping the central ovule, while on its top, three stigma primordia become apparent. At this stage, the two lateral stamens have well-formed anthers, and the abaxial stamen primordium starts differentiating (Fig. 5C and D). Early after the appearance of the stigma primordia, a hypogynous disc becomes distinct (Fig. 5E and F). The hypogynous disc grows simultaneously with the developing gynoecium (Fig. 5G and H), in which now an ovary, a single style and three stigmas can be distinghuished. At this stage, inside the ovary, the ovule primordium has become a basal, anatropic ovule, with intralocular hairs hiding the micropyle (Fig. 6C). The gynophore soon forms three lobes from a rim below the basal part of the ovary (Figs 5H and 6B and C). Meanwhile, the three stamens have become well developed, with elongating filaments, carrying anthers with long longitudinal slits (Fig. 5H). At the apex of the anthers, the connective develops into a spiny apiculus (Fig. 6F and H). In a mature stamen, the basal part of each pollen sac becomes slightly papillose (Fig. 6E). With the stamens matured, the stigma primordia develop fast into long, papillose stigmas (Figs 5C–H and 6A, D, F and G).

Fig. 5.

SEM images of the floral ontogeny in Ficinia zeyheri. (A) Lateral view of a rachilla apex with three successive stages of floral development (numbered 1–3). At stage ‘1’ a rim-like glume primordium originates. ‘G2’ is a developing glume. At stage ‘3’, a flower primordium (F3) can be seen. Its subtending glume is partially hidden by a lower glume. (B) Apical view of a rachilla apex, protected by a bonnet-shaped glume. A third, abaxial stamen originates in the flower primordium at the bottom right corner (arrowed). (C) Apical view of a developing flower. There is a delay in development of the abaxial stamen. (D) Adaxial view of a developing flower. One lateral stamen has been removed. (E) Detail of a developing gynoecium, with hypogynous stalk (arrowed). (F) View of a longitudinal section of a developing gynoecium, with hypogynous stalk under the adhesion of the ovule (arrowed). (G) View of a developing gynoecium. The hypogynous stalk is forming a rim at the base of the ovary (arrowed). (H) Adaxial view of a nearly mature flower. The hypogynous stalk is forming a rim at the base of the ovary (arrowed). Abbreviations: a, anther; f, filament; F, flower primordium; G, glume; o, ovule (primordium); ov, ovary (primordium); s, stamen (primordium); sg, stigma (primordium); st, style; *, rachilla apex.

Fig. 6.

SEM images of the floral ontogeny in Ficinia zeyheri. (A) Detail of style, stigmas and anthers of a nearly mature flower. Stamens have lengthened. (B) Detail of the base of an ovary. The lobes of the gynophore, which alternate with the stamens, have been formed. (C) View of an ovary with a central, anatropous ovule. Part of the ovary wall has been removed. Below the micropyle, there are pollen tube-conducting hairs (arrowed). The ovule is positioned above the gynophore, compared with the gynophore lobe (left). (D) Semi-mature stamens with spiny apiculus (arrowed). (E) Detail of the adaxial, basal part of a mature flower. The base of each pollen sac is slightly papillose (arrowed). (F) Survey of a mature gynoecium, with lobed gynophore enveloping the base of the ovary. (G) Detail of stigmas. (H) Detail of two apiculi. Abbreviations: a, anther; f, filament; gp, gynophore; o. ovule; ov, ovary (primordium); ps, pollen sac; sg, stigma (primordium); st, style.

The floral ontogeny in Ficinia gracilis Schrad

The spikelet in F. gracilis consists of an indeterminate rachilla, and many spirally placed, lateral glumes, each subtending a bisexual flower (Fig. 7A and B). New glumes originate successively below the rachilla apex, forming a rim-like structure (Fig. 7B and C). Next, a flower primordium is formed in the axil of the glume, which soon expands laterally, developing two lateral stamen primordia, and simultaneously a gynoecium primordium at its apex (Fig. 7C). A third, abaxial, stamen primordium appears with some delay (Fig. 7D–G). Meanwhile the gynoecium primordium is raised by the formation of a hypogynous stalk (Fig. 7E and G). Subsequently, the gynoecium primordium differentiates into an annular ovary primordium (or three congenitally fused carpel primordia) and a central ovule primordium (Fig. 7F). At the same time the two lateral stamen primordia differentiate into filaments and anthers (Fig. 7G–I), followed with some delay by the development of the abaxial stamen (Fig. 7F and I). The annular ovary primordium grows up from the base (Fig. 7I), forming an ovary wall that eventually encloses the ovule. The ovary wall grows out, forming a single style without a distinct style base (Fig. 8A and B). On the top of the ovary wall, three stigma primordia appear (Fig. 7I) that develop into three long papillose stigmas (Fig. 8D and H). The ovary wall continues to rise from its base, forming a single style without a distinct style base (Fig. 8A and B). Simultaneously, filaments and anthers elongate, and a blunt apiculus is formed from the apical part of the connective (Figs 7A and 8C). The apiculi continue growing until the stamens have reached full maturity. By this stage, the connective crests have become huge spiny structures (Fig. 7A). With the lengthening of the style, the texture of the external surface of the ovary wall gradually changes (Fig. 8B). Star-shaped structures (Fig. 15F) appear, which spread from the apex to the base of the ovary (Fig. 8E and F). The surface of mature nutlets, however, is smooth (Fig. 8I) at low magnification. During the development of the flower, the hypogynous stalk grows slightly, forming a gynophore under the gynoecium (Fig. 8A and D), from which a lobed rim enveloping the base of the ovary is formed (Fig. 8E and G). In a mature nutlet, the gynophore lobes envelop its base (Fig. 8I).

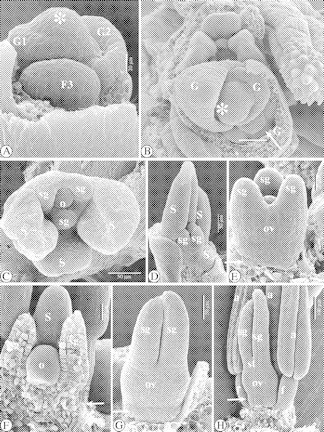

Fig. 7.

SEM images of the floral ontogeny in Ficinia gracilis. (A) Apical part of a spikelet, with several spirally placed glumes, subtending each a flower at different ontogenetic stages. The arrows indicate successive developmental stages of connective crests. (B) Apical view of rachilla apex and flowers at different stages of development, numbered 1–4. At stage ‘1’, a rim-like glume primordium originates. At stage ‘4’, a flower primordium (F4) and its subtending glume (G4) are visible. (C) Detail of rachilla apex with at the left-hand side a flower primordium with two lateral stamen primordia and an apical gynoecium appearing. (D) Apical view of a flower primordium with two lateral stamen primordia, and an apical gynoecium primordium (subtending glume removed). (E) The abaxial stamen primordium appears, and a hypogynous stalk is formed (arrowed). (F) Apical view. The gynoecium primordium starts differentiating into an annular ovary primordium and a central ovule primordium. (G) Adaxial view of a developing flower. The lateral stamen primordia start differentiating into anthers and filaments. There is a hypogynous stalk (arrowed). (H) Lateral view. There is a delay in the development of the abaxial stamen primordium. (I) Apical view. Two lateral-adaxial stigma primordia become apparent on the top of the ovary wall. One stamen has been removed. Abbreviations: G, glume; g, gynoecium (primordium); o, ovule (primordium); ov, ovary (primordium); s, stamen (primordium); sg, stigma (primordium); *, rachilla apex.

Fig. 8.

SEM images of the floral ontogeny in Ficinia gracilis. (A) Semi-mature gynoecium with gynophore beneath the ovary. (B) Style without a distinctive style base. (C) Blunt apiculus on the apex of the anthers (arrowed). (D) Mature ovary with gynophore (arrowed) and remains of filaments in subtending glume. (E) Mature flower with shrivelling stamens and style. There are star-shaped wax deposits at the apical part of the gynoecium. (F) Ripening nutlet with star-shaped wax deposits all over the surface of the nutlet, except at its base. (G) Detail of the gynophore in a mature flower. (H) Detail of stigma. (I) Mature nutlet with gynophore lobes at its base (left) showing smooth surface. Abbreviations: a, anther; f, filament; gp, gynophore; nu, nutlet; ov, ovary (primordium); sg, stigma (primordium); st, style.

The floral ontogeny in Isolepis setacea (L.) R.Br.

The spikelet in Isolepis setacea consists of an indeterminate rachilla, and many spirally (tristichously) placed glumes, each subtending a bisexual flower (Fig. 9A). Laterally, below the rachilla apex, new glumes appear one by one, as a rim-like structure (Fig. 9A). In the axil of the developing glume a flower primordium originates as a bulge, that soon expands laterally (Fig. 9B–D), forming two stamen primordia (Fig. 9E and F). Simultaneously, an apical gynoecium primordium appears (Fig. 9D–G), which is, at the early developmental stages, raised by a hypogynous stalk (Fig. 9F and G). Next, a third, abaxial, stamen primordium is formed (Fig. 9G). The abaxial stamen develops with some delay, compared with the two lateral ones (Fig. 9H–J). Subsequently, the gynoecium primordium differentiates into an annular ovary primordium and an ovule primordium (Fig. 9G–I). The ovary primordium grows up from the base, forming the ovary wall, which surrounds the central ovule (Fig. 9I and J). Subsequently, the ovary wall envelops the ovule and forms a long single style (Fig. 10F and G) without a distinct style base (Fig. 10F and G). On the top of the ovary primordium soon two lateral, adaxial stigma primordia appear (Fig. 9J), followed by a third abaxial one (Fig. 9K). The stigma primordia elongate simultaneously with the development of the ovary (Fig. 10B–D), forming three long papillose stigmas (Fig. 10K). Meanwhile, the stamen primordia developed into filaments and anthers (Figs 9I–K and 10A and B), forming long basifixed, introrse stamens. Soon, the apical part of the connective grows out into an apiculus (Fig. 10A, B and L), and the base of each pollen sac becomes papillose (Fig. 10F and G). After the development of the gynoecium, the filaments as well as the anthers lengthen fast (Fig. 10D, G and H). Eventually the filaments protrude above the ovary (Fig. 10H). Rudiments of a hypogynous stalk remain visible at the base of the nutlet (Fig. 10H–J).

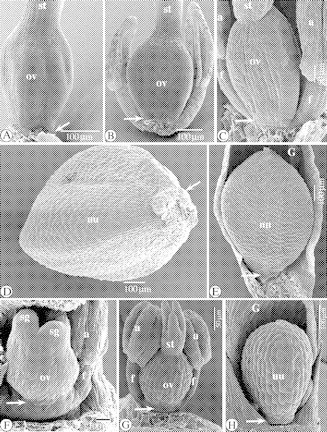

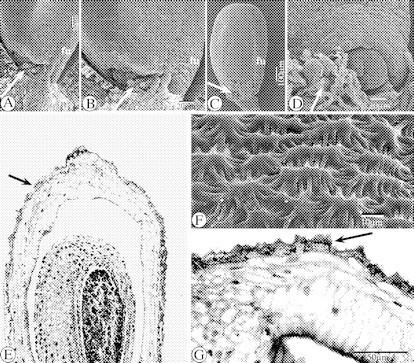

Fig. 9.

SEM images of the floral ontogeny in Isolepis setacea. (A) Spikelet apex with several spirally placed glumes, each subtending a flower in successive developmental stages, numbered 1–4. At stage ‘1’, a glume primordium (G1) subtends an originating flower primordium (F1). At stage ‘3’ a flower primordium (F3) with two lateral stamen primordia can be seen. At stage ‘4’, the glume (G4) subtends a flower (F4) with all flower parts present. (B) Detail of rachilla apex and distal flower primordia. (C) Detail of flower primordium in the axil of a subtending glume. (D) Abaxial view of a flower primordium, forming two lateral stamen primordia and apically a gynoecium primordium. (E) Apical-abaxial view of a flower primordium with two lateral stamen primordia and a gynoecium primordium on its top. (F) Abaxial view on a flower primordium with two, lateral stamen primordia and dome-shaped gynoecium primordium. (G) The gynoecium primordium becomes disc-like. (H and I) Differentiation of the gynoecium primordium into an annular ovary primordium surrounding a central ovule primordium. (J) Two adaxial-lateral stigma primordia appear on the top of the ovary wall. Meanwhile, the third, abaxial stamen primordium, appeared, and the lateral ones have developed into filaments and anthers. (K) Three stigma primordia grow out. The three stamens are developing. Abbreviations: G, glume; F, flower primordium; g, gynoecium (primordium); o, ovule (primordium); ov, ovary (primordium); s, stamen (primordium); sg, stigma (primordium); *, rachilla apex.

Fig. 10.

SEM images of the floral ontogeny in Isolepis setacea. (A) Lateral view of a developing flower. The development of the abaxial stamen is delayed. Connective crests are being formed (arrowed). (B) Lateral view of a developing flower. One lateral stamen has been removed. The stigmas are growing out. An apiculus is visible on the remaining lateral stamen (arrowed). (C) Apical part of a spikelet, with proximally a well-developed, nearly mature flower. One lateral stamen of it has been removed. (D) Abaxial view of a nearly mature flower. The stigmas become papillose. (E) Lateral view of the base of a nearly mature flower, with rudiments of a hypogynous stalk (arrowed). (F) Single style without a distinct style base, and anthers with pollen sacs with basal, papillose cells and a papillose apiculus. (G) Lateral view of a semi-mature flower, with one lateral stamen removed. (H) Adaxial view of a mature flower, with prolonged filaments, and rudiments of a hypogynous disc (arrowed). (I) Detail of the elementary hypogynous disc. (J) Nutlet. (K) Papillose stigmas. (L) Papillose apiculus. Abbreviations: a, anther; f, filament; nu, nutlet; o, ovule (primordium); ov, ovary (primordium); s, stamen (primordium); sg, stigma (primordium); st, style.

The floral ontogeny in Isolepis antarctica (L.) Roem. & Schult

Isolepis antarctica spikelets consist of an indeterminate (Fig. 11A–C) rachilla with many, spirally arranged glumes (Fig. 11A and B). Each glume subtends a bisexual flower. New glumes originate one by one laterally below the rachilla apex (Fig. 11A–C). Soon, a floral primordium appears in the axil of the glume (Fig. 11C), which expands laterally (Fig. 11D), forming two lateral stamen primordia, subsequently followed by the development of a third, abaxial one (Fig. 11E). Simultaneously, a gynoecium primordium originates on the apical part of the flower primordium (Fig. 11E). Meanwhile the subtending glume develops slowly (Fig. 11C–G). Older glumes grow into a bonnet-like form, protecting the flower bud in their axil (Fig. 11A and B) and even the spikelet apex (Fig. 11F). The gynoecium primordium differentiates into an annular ovary primordium surrounding a central ovule primordium (Fig. 11F–G). The ovary primordium grows up from the base, forming an ovary wall (Fig. 11H). The ovary wall gradually envelops the ovule (Fig. 11G–I), eventually forming a single style without a distinct style base (Figs 11J and K and 12A and B). On the top of the ovary wall, first two lateral stigma primordia (Fig. 11H) and next an abaxial one originate (Fig. 11I), which develop into three papillose stigmas (Fig. 11J and L). Meanwhile, each stamen primordium differentiates into a filament, and a basifixed, introrse anther, with long longitudinal slits (Fig. 11H–M). In a mature anther, the apical part of the connective forms a papillose apiculus (Fig. 11K–M). The cells at the base of each pollen sac also become slightly papillose (Fig. 11M). In well-developed, nearly mature flowers, a rudimentary gynophore can be observed under the ovary (Fig. 12A–C), of which rudiments remain on the nutlet (Fig. 12D and E).

Fig. 11.

SEM images of the floral ontogeny in Isolepis antarctica. (A) Apical view of the spikelet apex with spirally placed glumes, each subtending a flower in various developmental stages, numbered 1–8. At stage ‘1’, a rim-like glume primordium originates. At stage ‘2’, the floral primordium is appearing. At stage ‘7’, all floral parts are present in the flower (F7). (B) Lateral view of the distal part of a spikelet. Notice the flowers (gynoecia) in different ontogenetic stages (arrowed 1–3). (C) Flower primordium in the axil of its subtending glume. (D) Two lateral stamen primordia appear. (E) The abaxial stamen primordium is formed, together with the gynoecium primordium. (F) Apical view, with developmental delay of the abaxial stamen primordium. (G) The gynoecium primordium differentiates into an annular ovary primordium, surrounding a central ovule primordium. (H) The ovary primordium raises from its base, and on the top of it two lateral stigma primordia are formed, followed by a third, abaxial one. (I) The stigma primordia grow out. (J) Developing flower, with prolonged stigmas. (K) The style is lengthening. Connective crests appear (arrowed). (L) Stigmas become papillose. (M) The apiculi or connective crests (arrowed) grow out, becoming slightly papillose, like the bases of the pollen sacs. Abbreviations: a, anther; f, filament; F, flower primordium; G, glume; g, gynoecium (primordium); o, ovule (primordium); ov, ovary (primordium); s, stamen (primordium); sg, stigma (primordium); st, style; *, rachilla apex.

Fig. 12.

SEM images of the floral ontogeny in Isolepis antarctica (A–E), and three floral developmental stages in Cyperus haspan L. (F–H). (A) Isolepis antarctica. Nearly mature ovary with style base. The base of the ovary is arrowed. (B and C) As (A), with rudimentary hypogynous stalk (arrowed). (D) Isolepis antarctica. Basal part of a nutlet, with rudiments of the hypogynous stalk (arrowed). (E) Isolepis antarctica. Nutlet in subtending glume, with rudiments of the hypogynous stalk (arrowed). (F and G) Cyperus haspan. Successive developmental stages of a flower, with hypogynous stalk beneath the ovary (arrowed). (H) Cyperus haspan. Nutlet in glume, with rudimentary stalk at the base of the nutlet (arrowed). Abbreviations: a, anther; f, filament; nu, nutlet; ov, ovary; sg, stigma; st, style.

Floral ontogenetic stages in Cyperus haspan L.

The gynoecium in Cyperus haspan stands on a hypogynous stalk, from the earliest ontogenetic stages (Fig. 12F) until the development of a nutlet (Fig. 12G and H).

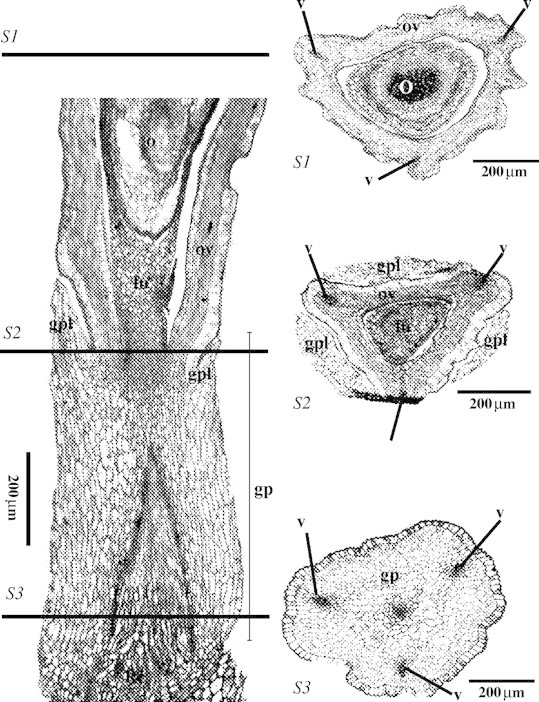

LM observations of the gynophore in Ficinia radiata (L.f.) Kunth

Longitudinal and transverse sections of the gynophore (Fig. 13) show that the gynophore lobes (gpl) grow out from the hypogynous stalk, enveloping the base of the ovary.

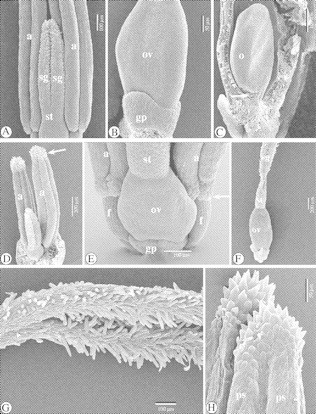

Fig. 13.

LM images of a longitudinal section (left) of the gynophore and basal part of the ovary and three transverse sections (S1–S3), of Ficinia radiata. Abbreviations: fu, funiculus; G, glume; gp, gynophore; gpl, gynophore lobe; nu, nutlet; o, ovule; ov, ovary; Rc, receptacle; v, vascular bundle; sg, stigma (primordium).

SEM observations of flower receptacle and gynophore in Ficinia capitella (Thunb.) Nees, F. minutiflora C.B.Clarke and F. radiata (L.f.) Kunth

In F. capitella (Fig. 14C), F. minutiflora (Fig. 14A and B) and F. radiata (Fig. 14D), bulges alternating with the stamens can be observed at the abaxial side. and not at the adaxial side (Fig. 14E and F).

Fig. 14.

SEM images of the dome-like flower receptacle and gynophore in Ficinia capitella (Thunb.) Nees, F. minutiflora, and F. radiata. (A) Apical view of an early developmental stage of a flower in F. minutiflora, with stamens removed. The bulges of the gynophore alternate with the staminal scars (arrowed). (B) As (A), lateral-abaxial view. (C) Lateral-abaxial view of a early developmental stage of a flower in F. capitella, with interstaminal bulge (arrowed). (D) Lateral-abaxial view of early developmental stage of a flower in F. radiata, with interstaminal bulges (arrowed). (E) Adaxial view of a developing flower in F. capitella, with developing gynophore beneath the ovary. There is no adaxial bulge. (F) Adaxial view of a developing flower in F. radiata, with developing gynophore beneath the ovary. There is no adaxial bulge. Abbreviations: gp, gynophore; ov, ovary; s, stamen (scar); sg, stigma; st, style.

SEM observations of intralocular hairs (obturator) in Ficinia Schrad

The micropylar zone in F. zeyheri Boeck (Fig. 15A and B) and F. radiata (L.f.) Kunth (Fig. 15C and D) is hidden by intralocular hairs.

Fig. 15.

SEM images of the intralocular hairs in Ficinia radiata and F. zeyheri (A–D), SEM image in F. gracilis of the surface of a ripening ovary (F) and LM images of longitudinal sections of its wall (E and G). (A) SEM image of the micropyle and intralocular hairs (arrowed) in the ovule of a flower in F. zeyheri. (B) Detail of (A). (C) SEM image of an isolated ovule and sticking intralocular hairs (arrowed) at the micropylar zone in F. radiata. (D) SEM image of a detail of the micropyle and sticking hairs (arrowed) surrounding it, in F. radiata. (E) LM image of a longitudinal section of a ripening ovary in F. gracilis, with cuticle (arrowed). (F) SEM image of the surface of the wall of a ripening ovary in F. gracilis. (G) LM image of a detail of epiderm and cuticle (arrowed) of the wall of a semi-mature ovary in F. gracilis. Abbreviation: fu, funiculus.

LM and SEM observations of the cuticle of a semi-mature ovary in Ficinia gracilis Schrad

The cuticle in F. gracilis (Fig. 15E and G) consists of irregular star-shaped structures (Figs 8B, E and F and 15F).

DISCUSSION

The floral ontogeny in all Cyperoideae sensu Simpson et al. (2005), observed until now, occurs according to a fixed, Scirpus-like pattern (Vrijdaghs et al., 2005a). Consistent with our previous floral ontogenetic descriptions (Vrijdaghs et al., 2003, 2004, 2005a), we use the word ‘glume’ to exclusively indicate floral bracts within Cyperaceous spikelets. A glume may subtend a flower, or not (e.g. the proximal, first-formed glume or prophyll). The spikelet and floral ontogeny in Ficinia and Isolepis also follows the general pattern: each glume originates laterally, below the indeterminate rachilla apex. Next a bulge-like flower primordium appears in its apex. Subsequently the flower primordium forms two lateral stamen primordia, followed by a third abaxial stamen primordium with some delay. More or less simultaneously, a gynoecium primordium appears on the top of the flower primordium. In Ficinia, from the earliest ontogenetic stages, the gynoecium primordium is raised by a hypogynous stalk. In mature flowers/fruits, the hypogynous stalk has lobes and appears as a ‘cupula’ (Haines and Lye, 1983) enveloping the base of the ovary/nutlet. Following Haines and Lye (1983), we call the hypogynous stalk together with the cupula the ‘gynophore’. In Isolepis, a hypogynous stalk is apparent. However, only rudiments of a hypogynous stalk are visible at the base of the nutlet in I. setacea (Fig. 10), and a rudimentary hypogynous stalk is observed at the base of mature nutlets in I. antarctica (Fig. 12). Isolepis antarctica and I. marginata have been included in Isolepis, due to their annual habit and the absence of a gynophore, but recent molecular phylogenetic studies show that both are embedded in the Ficinia clade and sister to F. gracilis (Muasya et al., 2001; Simpson et al., 2005). Several typical Ficinia (e.g. F. tenuifolia Kunth, F. rigida Levyns and F. trollii (Kuk.) Muasya & D.A. Simpson) lack a gynophore (Goetghebeur, 1998; Muasya et al., 2000). Systematic studies of Ficinia are in progress and formal nomenclatural changes to transfer I. antarctica and I. marginata into Ficinia are in preparation.

Schönland (1922) suggested that the gynophore is homologous with the inner whorl of stamens, based on the observation that in some species three ‘lobes’ alternating with the stamens are present. Our observations, however, show that, at earlier stages, the ‘gynophore’ consists of nothing more than a stalk beneath the gynoecium. When the flower reaches maturity, cells from the apical part of the hypogynous stalk proliferate, forming a rim surrounding the base of the nutlet, from which the lobes that envelop the base of the nutlet develop (Figs 2–6 and 8). From a longitudinal section of a nearly mature ovary, it is clear that the insertion of the single, basal, anatropous ovule is above the hypogynous stalk (Fig. 13). Transverse sections in the gynophore, at the fixation point of the funiculus, and halfway the ovary, show that the gynophore consists of parenchyma surrounded by the epidermis, and four vascular bundles; three peripheral bundles vascularizing the three carpels, and a central one vascularizing the central ovule (Fig. 13). If the hypogynous lobes had been homologous with the internal stamens, the vascularization pattern within the gynophore would have been more complex. Hence, our results confirm the observations of Arnold and Gordon-Gray (1982), who considered the often three-lobed ‘cupula’ surrounding the base of the nutlet to be outgrowths from the hypogynous stalk. In F. minutiflora, the gynophore is broadened at the base, and two abaxial bulges alternate with the stamens (Fig. 1J and L). Similar observations were made on F. radiata and F. capitella (Fig. 14A–D). It is tempting to interprete these bulges to be rudiments of the internal staminal whorl. However, at the adaxial side, there is no rudimentary stamen (Fig. 14E and F). Considering these bulges to be part of the gynophore, one might argue that the gynophore is actually an androgynophore. However, the stamens originate before the appearance of the hypogynous stalk, and at later stages the insertion of the stamens is very basal (Fig. 14). Moreover, there are no staminal traces in a transverse section of the basal part of the gynophore in F. radiata (Fig. 13S1–S3). From our observations, it is not possible to determine where the flower receptacle ends and the gynophore begins (Fig. 13).

It is concluded that Schönland's (1922) hypothesis is not confirmed, because (a) the lobes of the cupula originate from the apical part of the hypogynous stalk, while the insertion of the stamens (which belong to the outer whorl of stamens, since they are opposed to the ribs of the ovary) is below the gynophore, (b) there is a large plastochron between the formation of the stamens and the appearance of the lobes of the cupula, (c) the insertion of the central ovule and ovary wall is at the apex of the gynophore, showing that the gynophore is a hypogynous stalk, and (d) the vascularization of the gynophore does not include any staminal vascular bundles.

In Isolepis, a rudimentary hypogynous stalk is present (Figs 10H–J and 12B–E) and similar observations have been made in Cyperus (Fig. 12F–H).

In other genera, a tendency of the flower receptacle to form a dome-like stalk beneath the flower (Vrijdaghs et al., 2004, 2005a, b) at the first developmental stages has also been observed. At maturity, however, only Ficinia species have a hypogynous stalk with lobes surrounding the base of the ovary and later fruits. Therefore the term ‘gynophore’ is used for the typical ficinoid lobed hypogynous stalk. Most other genera in the former Cypereae sensu Goetghebeur (1998) lack a gynophore, but similar structures are also observed in the Cyperaceae in genera such as Alinula (Goetghebeur, 1998), Fimbristylis, Diplacrum and Scleria (Schönland, 1922).

In all the species studied, the lateral stamens originate and develop faster than the abaxial stamen. In all Ficinia species studied, and in I. setacea, at first, the growth of the androecium occurs faster than the development of the gynoecium. However, in nearly mature flowers the filaments and anthers lengthen very fast, eventually protruding far above the gynoecium. The initial ontogenetic pattern in I. antarctica, however, derives, with the gynoecium developing faster than the androecium. The stamens of the species studied in both genera, develop outgrowths from the apical part of the connective, which we call, following Haines and Lye (1983), apiculi or connective crests. The bases of the pollens sacs tend to become papillose.

In the mature ovary of F. zeyheri (Figs 6C and 15A and B) and F. radiata (Fig. 15C and D), at the abaxial side, intralocular hairs can be observed beneath the micropyle. Similar observations have been made in other genera such as Fimbristylis, Schoenoplectus, Dulichium, and Kyllinga (A. Vrijdaghs unpubl. res.). Van Der Veken (1964, p. 13) reported the observation in Cyperus flavescens L. of papillose to hair-like cells growing from the abaxial side of the funiculus as well as from the teguments. According to him, these hairs function as an obturator.

In both genera studied, there are no perianth parts. This is a common feature in most former Cypereae sensu Goetghebeur (1998). In Isolepis as well as in Ficinia, the glumes are spiro-tristichously arranged, which makes the spikelet and floral ontogeny very similar to that observed in Scirpoides (Vrijdaghs et al., 2005a).

Acknowledgments

We thank Marcel Verhaegen, for assistance with SEM observations at the National Botanic Garden of Belgium in Meise, Stefan Vinckier and Anja Vandeperre, for professional help with the LM preparations. This work was supported financially by research grants of the K.U. Leuven (0T/01/25) and the Fund for Scientific Research-Flanders (FWO-Vlaanderen, Belgium, G.0104.01; 1.5.061.03 and 1.5.069.02). A.M.M. is a visiting post-doctoral fellow of the Fund for Scientific Research-Flanders (FWO-Vlaanderen, Belgium) and of the K.U. Leuven.

Footnotes

Present address: Laboratory of Plant Systematics, Institute of Botany and Microbiology, K.U. Leuven, Kasteelpark Arenberg 31, B-3001 Leuven, Belgium.

LITERATURE CITED

- Arnold TH, Gordon-Gray KD. 1982. Notes on the genus Ficinia (Cyperaceae): morphological variation within the section Bracteosae Bothalia 14: 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bruhl JJ. 1991. Comparative development of some taxonomically critical floral/inflorescence features in Cyperaceae. Australian Journal of Botany 39: 119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Goetghebeur P. 1986.Genera Cyperacearum. Een bijdrage tot de kennis van de morfologie, systematiek en fylogenese van de Cyperaceae-genera. PhD thesis, Groep Plantkunde, Rijksuniversiteit Gent. Gent. [Google Scholar]

- Goetghebeur P. 1998. Cyperaceae. In: Kubitzki K, ed. The families and genera of vascular plants. IV Flowering plants—Monocotyledons. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 141–190. [Google Scholar]

- Haines RW, Lye KA. 1983.The sedges and rushes of East Africa. Nairobi: East African National History Society. [Google Scholar]

- Mora LE. 1960. Beitrage zur Entwicklungsgeschichte und vergleichende Morphologie der Cyperaceen. Beiträge zur Biologie der Pflanzen 35: 253–341. [Google Scholar]

- Muasya AM, Simpson DA. 2002. A monograph of the genus Isolepis R.Br. (Cyperaceae). Kew Bulletin 57: 257–362. [Google Scholar]

- Muasya AM, Simpson DA, Chase MW, Culham A. 1998. An assessment of suprageneric phylogeny in Cyperaceae using rbcL DNA sequences. Plant Systematics and Evolution 211: 257–271. [Google Scholar]

- Muasya AM, Simpson DA, Goetghebeur P. 2000. New combinations in Trichophorum, Scirpoides, and Ficinia (Cyperaceae). Novon 10: 132–133. [Google Scholar]

- Muasya AM, Simpson DA, Chase MW, Culham A. 2001. A phylogeny of Isolepis (Cyperaceae) inferred using plastid rbcL and trnL-F sequence data. Systematic Botany 26: 342–353. [Google Scholar]

- Richards JH. 2002. Flower and spikelet morphology in sawgrass, Cladium jamaicense Crantz (Cyperaceae). Annals of Botany 90: 361–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönland S. 1922. Introduction to South African Cyperaceae. Memoirs of the Botanical Survey of South Africa 3: 41. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DA, Muasya AM, Alves M, Bruhl JJ, Dhooge S, Chase MW, et al. 2005. Phylogeny of Cyperaceae based on DNA sequence data—a new rbcL analysis. In: Monocots III/Grasses IV. Claremont, CA: ALISO, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Veken P. 1964.Bijdrage tot de systematische embryologie der Cyperaceae-Cyperoideae. PhD thesis, K.U. Leuven, Leuven. [Google Scholar]

- Vrijdaghs A, Goetghebeur P, Smets E, Caris P. 2003. The orientation of the developing gynoecium of Cladium mariscus (L.) Pohl. In: Bayer C, Dressler S, Schneider J, Zizka G, eds. 16th International Symposium Biodiversity and Evolutionary Biology, 17th International Senckenberg Conference. Abstracts: 24. Palmarum Hortus Francofurtensis 7, Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Vrijdaghs A, Goetghebeur P, Smets E, Muasya AM, Caris P. 2004. The nature of the perianth in Fuirena (Cyperaceae). South African Journal of Botany 70: 587–594. [Google Scholar]

- Vrijdaghs A, Caris P, Goetghebeur P, Smets E. 2005a. Floral ontogeny in Scirpus, Dulichium and Eriophorum (Cyperaceae), with special reference to the perianth. Annals of Botany 95: 1199–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrijdaghs A, Goetghebeur P, Smets E, Caris P. 2005b. The Schoenus spikelet a rhipidium? A floral ontogenetic answer. In: Monocots III/Grasses IV. Claremont, CA: ALISO, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden (in press). [Google Scholar]