Summary

Background

There are few epidemiological studies of suicide in India.

Methods

A nationally representative mortality survey determined the cause of death occurring in 1·1 million homes in 6671 small areas chosen randomly from all parts of India. Two trained physicians independently assigned codes to the causes of death, based on a nonmedical surveyor’s field interview with household respondents.

Findings

About 3% of deaths at ages 15 years and older (2684/95 335) were due to suicide. This corresponds to about 187 000 suicide deaths in India in 2010 at these ages (115 000 men and 72 000 women; age-standardised rates per 100 000 at ages 15 years and older of 26·3 for men and 17·5 for women). For suicide deaths at ages 15 years and older 40% percent of male suicides and 56% of female suicides occurred at ages 15–29 years. A 15 year old in India had an approximate cumulative risk of 1·3% of dying before age 80 years by suicide; men had higher risk (1·7%) than women (1·0%), with especially high risks in South India (3·5% among men and 1·8% among women). Suicide risks were higher in educated versus illiterate adults. About half of the suicides were from poisoning, much of which was pesticide. At ages 15–29 years, suicide accounted for nearly as many deaths as transport accidents in men and maternal deaths in women.

Interpretation

Suicide death rates in India are amongst the highest in the world. A large proportion of suicides occur at younger ages, especially in women. Much of Indian suicides may be avoidable, starting with control of access to pesticides.

Funding

U.S. National Institutes of Health

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that nearly 900 000 people worldwide die from suicide every year, including about 200 000 in China, about 170 000 in India, and 140 000 in high-income countries.1 The Government of India relies on its National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) for national estimates, and these report fewer suicide deaths (about 135 000 suicides in 2010)2 than estimated by WHO. The reliability of the NCRB data is questionable since they are based on police reports.

Most public attention in India has focused on suicide in farmers.3 The age- and sex-specific death totals, rates and risks and the mode of suicide in India’s markedly diverse socio-demographic populations are not well understood. Reliable quantification of the suicide deaths is timely as the Government of India 12th Year Plan for 2012–17 includes strategies to tackle chronic disease, injuries and mental health.4 Here, we quantify suicide mortality within the ongoing Million Death Study (MDS) in India — one of the few nationally-representative studies of the causes of death in any low or middle-income country.5–7

Methods

Study Design

Details of the MDS design,5–7 assignment of the underlying causes of death, statistical methods and preliminary results for various diseases and risk factors have been published elsewhere.5–6, 8–10 In brief, the Registrar General of India (RGI) divides India into one million small areas based on the national census conducted every 10 years. The RGI’s Sample Registration System (SRS) selected randomly 6671 of these small areas (about 1000 persons per area) from the 1991 census and monitored all births and deaths in 1·1 million homes from 1993 to 2003. Each home in which a death had been recorded between 2001 and 2003 was visited by one of 800 nonmedical SRS field-surveyors to collect information about the cause of death as well as information on marital status, occupation, alcohol use and education. The underlying cause of each death was sought by an enhanced form of verbal autopsy, known as the routine, reliable, representative, re-sampled household investigation of mortality with medical evaluation (RHIME).5–7 The RHIME method involves a structured investigation of events prior to the death, including a written report in the local language of the household. The two-page field report is converted into electronic records and assigned randomly to two of 140 specially-trained physicians (assignment was stratified only by their ability to read the language of the narrative) who independently and anonymously assign codes to the causes of death using guidelines for the major causes.11 If the two physicians disagree on the assigned three-digit code from the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision,12 a senior physician adjudicates. About 5% of the deaths are re-sampled by independent teams reporting directly to us. Full details of the methods, quality-control checks, and comparisons to hospital deaths have been reported previously, and suggest that the MDS provides classifiable causes of death reliably, particularly before age 70.5, 13–14

Subjects

The suicides in this study were of all people who had died between 2001 and 2003 and whose causes of death were eventually assigned to ICD-10 codes X60 to X84 (intentional self harm). Interviewers, who were known to the communities from previous rounds of SRS field work, were trained to collect information on the causes of death from any close associate/relative of the deceased. The most common respondents for the 1599 male suicides above age 15 years were the parents of the deceased (351, 22%), his wife (328, 21%) or neighbours (156, 10%); for the 1085 female suicides above age 15 years, the most common respondents were other relatives (218, 20%), her husband (174, 16%) or neighbours (131, 12%). The remaining informants were usually other household members.

Analysis

We calculated national and state totals of suicide deaths (so as to inform health planners), age-standardised rates (to understand variation), and risks (to inform individuals). Analyses focused on ages 15 or older, as childhood suicides were rare. We applied the age- and sex-specific proportion of suicide deaths within the 2001–03 survey to the 2010 United Nations (UN) estimates of absolute numbers of deaths (and age-specific risks) for all causes in India. The 2010 UN totals of 9·8 million total deaths were used so as to provide contemporary comparisons with other diseases such as cancer10 and vascular disease. Moreover, the use of the UN totals corrects for the slight undercounts reported in the total death rates in the SRS15–16 and for the 12% of SRS deaths missed in the survey.6 The proportions of deaths from outmigration of the family or from incomplete field records that accounted for these missed deaths were similar across states (as presumably were the proportions of these deaths from suicide). We partitioned the 2010 UN total deaths into state-specific total deaths by using the relative SRS death rates for 2007–09 using methods described earlier.8–10 The forward projection to 2010 should not introduce major biases as the major determinant of state suicide totals (and age-specific risks) is the state-specific number of all cause deaths, and these are drawn from the more contemporary 2007–9 SRS rates. All suicide rates were standardised to the estimated total Indian population for 2010. Classification of the causes of death and not random variation is the main source of uncertainty in our estimates. Thus, the lower bounds for the total suicide deaths and age-standardised rates (Table 1) were based on the numbers of deaths that were immediately coded by both physicians as suicide, while the upper bounds were based on all deaths with suicide as the initial diagnosis by at least one coder.

Table 1.

Suicide-attributed deaths in the present study and estimated national totals for 2010, by age, region and residence.

| Study deaths, 2001–03 | All India, 2010 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers attributed to suicide/all deaths |

Proportion suicide* (%) |

Two coders immediately agree (%) |

All deaths/population (UN estimates) (millions) |

Estimated suicides‡ (×1000) |

Death rates** (lower, upper bounds) (per 100,000) |

Cumulative risk† (%) |

|||

| Male | |||||||||

| 0 – 14 | 28 / 13645 | 0·16 | 23 | (82·1) | 1·0 / 195 | 2·3 | 1·19 | (1·0 – 1·2) | 0·02 |

| 15 – 29 | 637 / 4725 | 13·2 | 556 | (87·3) | 0·4 / 177 | 45·1 | 25·5 | (22·3 – 26·5) | 0·40 |

| 30 – 44 | 486 / 6817 | 6·5 | 417 | (85·8) | 0·6 / 130 | 35·7 | 27·4 | (24·0 – 29·7) | 0·81 |

| 45 – 59 | 307 / 11731 | 2·4 | 257 | (83·7) | 1·0 / 86 | 22·4 | 26·2 | (21·4 – 29·3) | 1·20 |

| 60 – 69 | 98 / 12120 | 0·7 | 77 | (78·6) | 0·9 / 28 | 6·6 | 23·7 | (18·6 – 27·6) | 1·44 |

| 70+ ¶ | 71 / 18732 | 0·3 | 60 | (84·5) | 1·5 / 17 | 5·0 | 30·2 | (24·2 – 35·4) | 1·71 |

| Men 15 years of age and older | |||||||||

| South States | 724 /13430 | 5·3 | 671 | (92·7) | 1·0 / 94 | 50·6 | 52·9 | (48·9 – 54·6) | 3·51 |

| Rest of India | 875 / 40695 | 2·1 | 696 | (79·5) | 3·4 / 344 | 64·2 | 18·7 | (15·0 –20·3) | 1·16 |

| Rural | 1392 / 43927 | 3·1 | 1194 | (83·5) | 3·3/ 303·3 | 95·1 | 31·5 | (27·0 –33·2) | 2·05 |

| Urban | 207 / 10198 | 1·9 | 173 | (85·7) | 1·1/ 134·7 | 19·7 | 14·4 | (12·1 –15·6) | 0·81 |

| All India (lower, upper bounds) | 1599 / 54125 | 2·8 | 1367 | (85·5) | 4·4 / 438 | 114·8 (98·2 –124·0) | 26·3 | (22·5 –28·4) | 1·69 |

| Female | |||||||||

| 0 – 14 | 29 / 13447 | 0·24 | 23 | (79·3) | 1·1 / 179 | 3·0 | 1·68 | (1·3 –1·7) | 0·03 |

| 15 – 29 | 667 / 4394 | 14·5 | 585 | (87·7) | 0·3 / 162 | 40·5 | 24·9 | (21·6 –25·7) | 0·40 |

| 30 – 44 | 252 / 4055 | 6·0 | 222 | (88·1) | 0·3 / 121 | 19·2 | 15·9 | (13·8 –16·6) | 0·64 |

| 45 – 59 | 85 / 6402 | 1·2 | 73 | (85·9) | 0·6 / 81 | 6·8 | 8·4 | (7·2 –9·2) | 0·77 |

| 60 – 69 | 54 / 9016 | 0·6 | 43 | (79·6) | 0·7 / 29 | 3·8 | 13·2 | (10·4 –14·5) | 0·85 |

| 70+ ¶ | 27 / 17343 | 0·1 | 27 | (100) | 1·5 / 20 | 1·8 | 9·1 | (9·0 –9·7) | 0·99 |

| Women 15 years of age and older | |||||||||

| South States | 457 / 10236 | 4·5 | 425 | (92·9) | 0·8 / 97 | 29·5 | 32·2 | (29·6 –32·9) | 1·76 |

| Rest of India | 628 / 30974 | 2·0 | 525 | (83·6) | 2·6/ 316 | 42·6 | 13·3 | (11·1 –13·9) | 0·70 |

| Rural | 931 / 33793 | 2·7 | 820 | (88·1) | 2·6 / 293 | 57·8 | 20·4 | (17·5 –20·6) | 1·08 |

| Urban | 154 / 7417 | 2·1 | 130 | (84·4) | 0·8 / 120 | 14·3 | 12·0 | (9·6 –12·4) | 0·60 |

| All India (lower, upper bounds) | 1085 / 41210 | 2·6 | 950 | (87·5) | 3·4 / 413 | 72·1 (62·4 –75·4) | 17·5 | (15·2 –18·4) | 0·96 |

| Total men and women (15+) ¶ (lower, upper bounds) | 2684 / 95335 | 2·7 | 2317 | (86·3) | 7·8 / 851 | 186·9 (160·1 –199·5) | 22·0 | (18·9 –23·5) | 1·32 |

Suicide death rates for ages 15 years and older are age-standardised to the 2010 estimated Indian population.

Proportion of suicide deaths compared to all deaths, weighted by state and residence (urban/rural), although such weighting made little difference as the study is nationally representative.

Obtained by multiplying the United Nations estimated total deaths in 2010 by the weighted proportions.

Cumulative risk for 15 years and above was calculated by summing the risk from 15 to 79 years, yielding the probability of death from suicide if there were no other causes of death. Cumulative risk = (1− exp(−5 Σratei)) where i= age group in 5 year age groups.

‘South States’ include Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Puducherry, Lakshadweep and Andaman & Nicobar Islands. Rural areas are those with population of less than 5,000 or population density of less than 400 per sq km or more than 25 percent of the male working population engaged in agriculture.

Note: Lower bounds of death rates were based on the numbers of deaths that were immediately coded by both physicians as suicide, while the upper bounds were based on all deaths with suicide as the initial diagnosis by at least one coder.

A case-control study compared risk factors for suicide versus other deaths. Cases were defined as all suicides at ages 15–69 (verbal autopsy yields a far greater proportion of classifiable deaths at these ages than those above 70 years of age, although misclassification of suicide at older ages is less than for other causes5, 17). Controls were all non-suicide deaths at these ages (exclusion of other injury deaths from the controls did not material alter the results). We used logistic regression to compare the following variables for each gender: age at death (15–19, 20–29, 30–44, 45–59, 60–69 years); education (below primary, primary or middle, secondary or higher); geographical region (Southern states, rest of India); occupation (nonworker, cultivator, agricultural labour, business/professional); alcohol drinking status (drinker, non-drinker); religion (Hindu, Muslim, Buddhist/Jain, Christian); residence (rural, urban); and marital status (never married, married/remarried, widow/separated/divorced) and, as a measure of community wealth, the household fuel type used (gas/electricity/kerosene versus coal/firewood/other) in each SRS unit.

Role of the funding source

The sponsor of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

There were 2684 suicides among the total of 95 335 deaths at ages 15 years and older (2·7% weighted proportion; Table 1). Two physicians agreed on suicide as the cause of death at initial coding in about 87% of the deaths. The agreement rate was relatively consistent across the age ranges for both genders irrespective of the type of household or non-household informant. Only 19% of the deaths occurred in a health facility. 3275 of the deaths that randomly selected for re-interviewed by independent teams were eventually matched to the identical houses and individuals. Of these re-sampled deaths, 55 were coded as suicides, and 45 of these were found in the original survey. Thus, the sensitivity and specificity of the SRS field survey, assuming the re-sample deaths are the standard comparison, was 82% (45/55) and 75% (2409/3220), respectively.

The study proportion corresponds to about 187 000 suicide deaths in India in 2010 at ages 15 years and older (115 000 men and 72 000 women). Most of the suicides occurred at ages 15–69 years (110 000 men, 70 000 women, 180 000 total). Only 57 suicide deaths occurred below age 15, and only 20 suicide deaths occurred over age 80, so the cumulative risk shown for ages 15 to 79 years approximates lifetime risk. The overall probability of dying from suicide is a function of age-specific all-cause death rates, and the proportion due to suicide. It can be safely assumed that in the absence of suicide, survivors would face only the background rates of other deaths. Thus, a 15 year old in India had a cumulative risk of 1·3% of dying from suicide before age 80 years. Men had a higher cumulative risk (1·7%) than women (1·0%), with especially high risks in South India (3·5% among men and 1·8% among women).

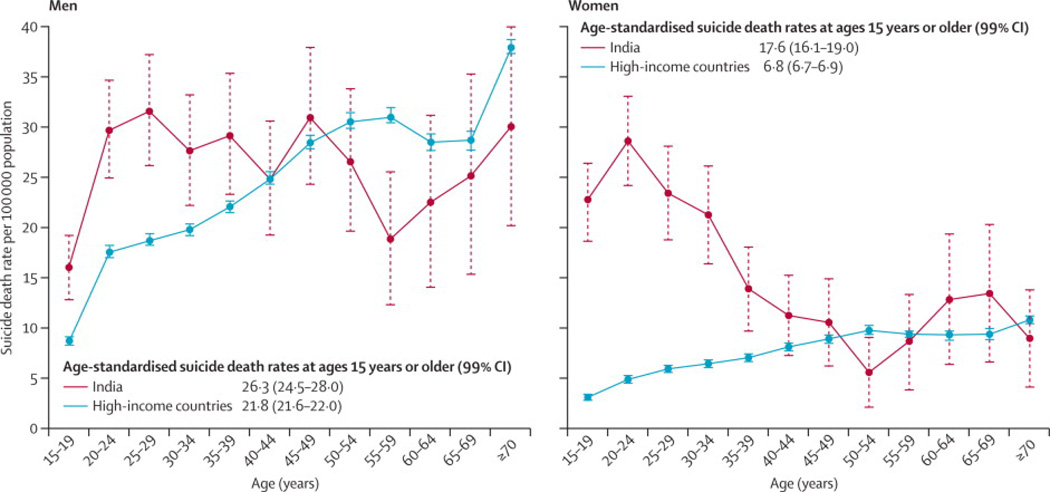

Of the total suicides at ages 15 years and older, about 40% of male suicides (45 1000/114 800) and about 56% of female suicides (40 500/72 100) occurred at ages 15–29 years. Suicides occurred at younger ages in women (median age 25 years) than in men (median age 34 years). The overall age-standardised suicide rates per 100 000 population at ages 15 years and older were 26·3 for males and 17·5 for females. The age-standardised rates per 100 000 at all ages were 18·6 for males and12·7 for females, respectively. Male death rates at ages 15 and older were generally consistent at around 25–30 per 100 000 men across age groups. Female death rates peaked at about 25 per 100 000 women at ages 15–29 years, and then fell in older women (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Age-specific suicide death rate per 100 000 for men and women in India and in high-income countries.

The rates for high-income countries (8·14 million deaths from a population of 977 million) are drawn from WHO1 and are based on nearly universal vital registration of deaths with medical certification. Age-standardised suicide rates for males and females at ages 0 years or older are 18·6 and 12·7, respectively in India and 21·8 and 6·8, respectively in high-income countries. All rates are standardised to the estimated Indian population in 2010.

At ages 15–29 years, suicide was the second leading cause of death in both genders, and accounted for nearly as many deaths as transport accidents in men and nearly as many as maternal deaths in women (Table 2).

Table 2.

Leading 5 causes of death among men and women age 15–29 from the first phase of the Million Death Study and contribution of them to the total mortality 2010

| Cause of death* | Estimated deaths (X1000) |

Contribution of each cause to the overall mortality (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Men | ||

| Transport accidents | 48 | 13·6 |

| Suicide | 45 | 12·8 |

| Other unintentional injuries** | 40 | 11·3 |

| Tuberculosis | 34 | 9·6 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 25 | 7·0 |

| Total of 5 leading causes | 192 | 54·3 |

| Women | ||

| Maternal conditions | 46 | 15·5 |

| Suicide | 40 | 13·7 |

| Tuberculosis | 30 | 10·3 |

| Unintentional injuries | 29 | 9·9 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 20 | 6·9 |

| Total of 5 leading causes | 165 | 56·3 |

Notes: Percentage to overall mortality was calculated after applying sample weights to adjust urban rural differences for each state in the sample deaths.

Causes of death were defined according to the following codes from the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision:12 Transport accidents (V01–99, Y85), Suicide (X60-84), Tuberculosis (A15–19, J65, B90), Cardiovascular diseases (G45–46, G81–83, I00–89), Maternal conditions (O00–99, A34, F53), Unintentional injuries (V01–99, W00–99, X00– 59, Y40–89), Other unintentional injuries (W00–99, X00– 59, Y40–84, Y86–89).

Other unintentional injuries include in men: 11% drowning, falls 7%, snakebite 7%; Unintentional injuries in women include: 29% fires, 18% transport accidents, 15% snakebites.

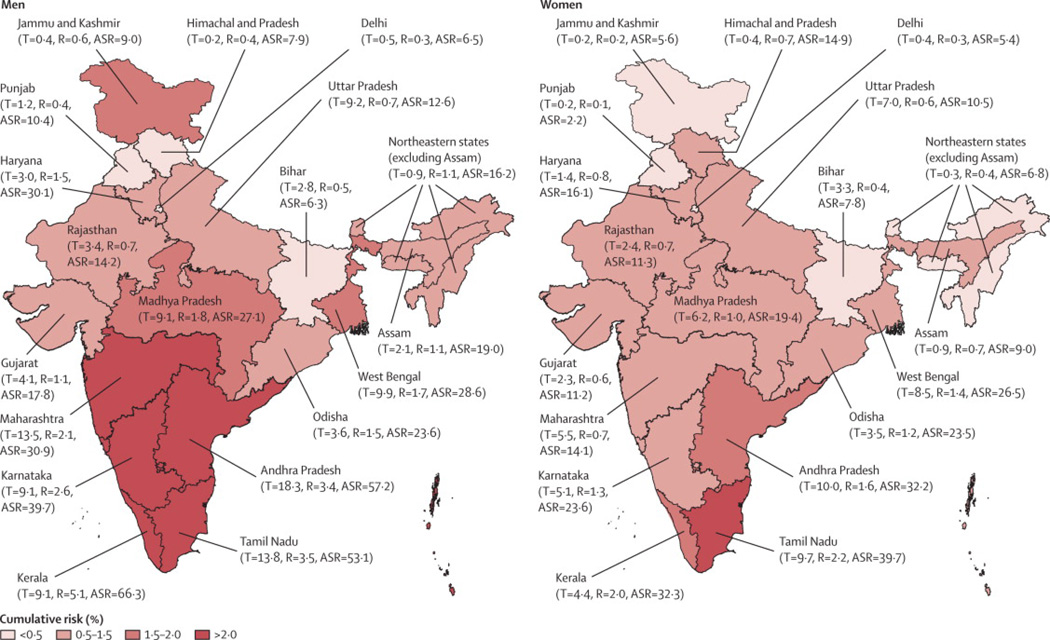

Most suicides occurred in rural areas; the age-standardised death rates at ages 15 years and older were about two-fold higher in rural than in urban areas. The variation in age standardised suicide rates at ages 15 years or older per 100 000 was more extreme between individual states (Figure 2), ranging between 6·3 to 66·3 for men and between 2·2 to 39·7 for women (Web appendix p 1). In the absence of other causes of death, more than 2% of 15-year-old males would die from suicide during their lifetimes in all of the southern states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu, and more than 2% of 15-year-old females would die from suicide during their lifetimes in Tamil Nadu. Over 42% of suicides in men and 40% of suicides in women occurred in these four southern states, which together constitute 22% of India’s population at ages 15 years and older. Maharashtra and West Bengal together accounted for an additional 15% of suicide deaths. In absolute numbers, the maximal suicides at ages 15 years and older were in Andhra Pradesh (28 000), Tamil Nadu (24 000) and Maharashtra (19 000). In the MDS questionnaire, “farmer” was not one of the recorded occupational categories. Therefore we combined “agricultural labour” and “cultivator” (who own their land) and defined these as “agricultural worker” which would include all farmers. However, suicide deaths among non workers and other workers were about three times greater than among agricultural workers (Web appendix p 2).

Figure 2. Percentage risk of suicide, age-standardised death rates per 100 000 and total suicides (1000’s) in men and women age 15 years and older by the major states of India.

Abbreviations: T=estimated number of suicide deaths in 1000’s; R=cumulative risk in % (see methods); ASR= age-standardised suicide death rate per 100 000.

Nationally, there were only 57 suicides below age 15 and 20 suicides above age 80 in the study, so the risks at ages 15–79 years are taken as an approximate lifetime risk.

State abbreviations are as follows: JK=Jammu and Kashmir, HP=Himachal Pradesh, PB=Punjab, HR=Haryana, DL=Delhi, RJ=Rajasthan, UP=Uttar Pradesh, BR=Bihar, AS=Assam, WB=West Bengal, OR=Orissa, MP=Madhya Pradesh, GJ=Gujarat, MH=Maharashtra, AP=Andhra Pradesh, KN=Karnataka, KL=Kerala, TN=Tamil Nadu, NE=Northeast States excluding Assam

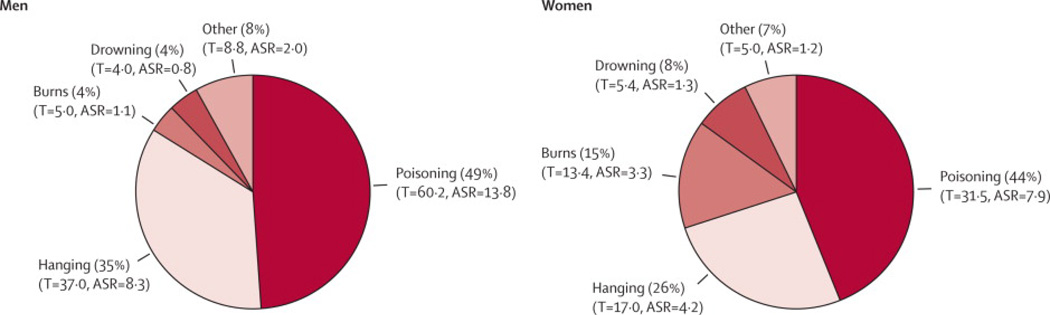

Poisoning, mostly from pesticides (chiefly organophosphates) used in agriculture, was the leading method of suicide in both men and women, corresponding to about 92 000 deaths nationally at ages 15 years and older (Figure 3). Over half (679) of the 1276 poisonings in the 2001–03 survey were classifiable (ICD-10 codes X60- X68) and 579 were unclassifiable (X69). Of classifiable poisonings, the vast majority (535) were from pesticide poisoning (X68). A keyword search among the unspecified poisonings suggested that an additional 75 were also due to pesticide poisoning. Thus, much, but not all of poisonings appeared to be from pesticide. Hanging was the second most common method. Burns were an important method for women, accounting for about one in six of suicides in women. Nearly three-fifths of suicides (1498) occurred at home. Poisonings were common in home suicide deaths as well as those in health facilities and hangings were the most common method for suicides at home (Web appendix p 3).

Figure 3. Age-standardised death rates per 100 000, total suicide deaths (1000’s) by method of suicide for men and women age 15 years and older.

The proportions are based on 1599 male and 1085 female sample deaths, with rates based on UN national totals of deaths for 2010.

Abbreviations: T = Estimated deaths by each method in 1000's, ASR = Age-standardised suicide rates per 100 000, standardised to the 2010 estimated India population. ICD-10- codes are as follows: poisoning (X60 to X69); hanging (X70), burns (X76-X77); drowning (X71); and other suicides (rest of the X60 to X84).

Physician agreement varied by the method of suicide. The highest agreement rates were observed for hanging (88%) and the lowest agreement rate was observed for poisoning (53–57%). Burning deaths in women, which may be due to accidents, suicide or homicide,37 showed moderately high levels of agreement in women (74%).

Higher education level, residency in South India, and Hindu religion (compared with Christian or Muslim religions) were significantly associated with the elevated risk of suicide at ages 15–69 years versus other causes of death in both men and women (Table 3). Drinking alcohol was associated with the risk of suicide in men, while being widowed, divorced or separated was associated with a slightly decreased risk of suicide in women. An occupation of agricultural work (Web appendix p 2) was weakly associated with suicide in men.

Table 3.

Variables and their estimated odds ratio associated for suicide versus other deaths* for men and women aged 15 to 69 years

| Men | Women | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers attributed to suicide/other deaths |

Proportion suicide/ other deaths |

Odd ratio of suicide versus other deaths (99% CI) |

Numbers attributed to suicide/other deaths |

Proportion suicide/ other deaths |

Odd ratio of suicide versus other deaths (99% CI) |

|||

| 1393 / 31351 | (%) | 964 / 21217 | (%) | |||||

| Education | ||||||||

| Secondary or higher | 231 / 4069 | 16·6 / 13·0 | 1·43 | (1·1 –1·8) | 135 / 962 | 14·0 / 4·5 | 1·90 | (1·4 –2·6) |

| Primary or middle | 594 / 8522 | 42·6 / 27·2 | 1·60 | (1·4 –1·9) | 298 / 2929 | 30·9 / 13·8 | 1·43 | (1·1 –1·8) |

| Below primary | 568 / 18 760 | 40·8 / 59·8 | 1·00 | -- | 531 / 17 326 | 55·1 / 81·7 | 1·00 | -- |

| Region | ||||||||

| Southern states | 624 / 7719 | 44·8 / 24·6 | 2·68 | (2·3 –3·1) | 387 / 4688 | 40·1 / 22·1 | 2·96 | (2·4 –3·6) |

| Rest of India | 769 / 23 632 | 55·2 / 75·4 | 1·00 | -- | 577 / 16 529 | 59·9 / 77·9 | 1·00 | -- |

| Religion | ||||||||

| Christian | 42 / 1181 | 3·0 / 3·8 | 0·50 | (0·3 –0·8) | 14 / 739 | 1·4 / 3·5 | 0·35 | (0·2 –0·7) |

| Sikh/ Buddhist/ Jain | 51 / 1422 | 3·7 / 4·5 | 0·82 | (0·6 –1·2) | 26 / 841 | 2·7 / 4·0 | 0·70 | (0·4 –1·2) |

| Muslim | 62 / 3226 | 4·4 / 10·3 | 0·53 | (0·4 –0·7) | 74 / 2353 | 7·7 / 11·1 | 0·69 | (0·5 –1·0) |

| Hindu | 1238 / 25 522 | 88·9 / 81·4 | 1·00 | -- | 850 / 17 284 | 88·2 / 81·4 | 1·00 | -- |

| Occupation | ||||||||

| Non worker | 449 / 9644 | 32·2 / 30·8 | 1·16 | (1·0 –1·4) | 648 / 14 799 | 67·2 / 69·7 | 0·86 | (0·6 –1·2) |

| Agricultural labour | 151 / 2720 | 10·9 / 8·7 | 1·23 | (0·9 –1·6) | 77 / 1464 | 8·0 / 6·9 | 0·84 | (0·6 –1·2) |

| Cultivator | 282 / 7003 | 20·2 / 22·3 | 1·30 | (1·1 –1·6) | 61 / 1822 | 6·3 / 8·6 | 1·17 | (0·9 –1·5) |

| Wage earner/ Professional/ Business | 511 / 11 984 | 36·7 / 38·2 | 1·00 | -- | 178 / 3132 | 18·5 / 14·8 | 1·00 | -- |

| Alcohol use | ||||||||

| Yes | 627 / 10 585 | 45·0 / 33·8 | 1·84 | (1·6 –2·2) | 35 / 1102 | 3·6 / 5·2 | 0·95 | (0·6 –1·5) |

| No | 766 / 20 766 | 55·0 / 66·2 | 1·00 | -- | 929 / 20 115 | 96·4 / 94·8 | 1·00 | -- |

| Marital Status | ||||||||

| Widower/divorced/separated | 51 / 3622 | 3·7 / 11·5 | 0·75 | (0·5 –1·1) | 67 / 7181 | 7·0 / 33·8 | 0·64 | (0·4 –0·9) |

| Never married | 464 / 4064 | 33·3 / 13·0 | 1·10 | (0·9 –1·4) | 264 / 1694 | 27·4 / 8·0 | 0·92 | (0·7 –1·2) |

| Married/ remarried | 878 / 23 665 | 63·0 / 75·5 | 1·00 | -- | 633 / 12 342 | 65·6 / 58·2 | 1·00 | -- |

| Residence | ||||||||

| Rural | 1216 / 25 301 | 87·3 / 81·0 | 1·45 | (1·1 –1·9) | 826 / 17 642 | 85·7 / 83·2 | 1·07 | (0·8 –1·5) |

| Urban | 177 / 6050 | 12·7 / 19·0 | 1·00 | -- | 138 / 3575 | 14·3 / 16·8 | 1·00 | -- |

| Household asset (fuel type) | ||||||||

| Coal/ firewood/ dung/ bio-gas | 1225 / 25 989 | 87·9 / 82·9 | 1·20 | (0·9 –1·6) | 850 / 18 011 | 88·2 / 84·9 | 1·31 | (0·9 –1·8) |

| Gas/ electricity/ kerosene | 168 / 5362 | 12·1 / 17·1 | 1·00 | -- | 114 / 3206 | 11·8 / 15·1 | 1·00 | -- |

Notes Odds ratio adjusted for age (5 age categories) and for the other variables in the model. Bold values are significant.

The analysis excluded 229 (8%) suicide cases and 4106 (7%) other deaths with missing or unknown values. Cultivator is defined as a person who engaged in cultivation of a privately or publicly-owned land and an agricultural laborer is defined as a person who works on another person’s land for wages in money.

Discussion

This first ever nationally-representative survey of causes of deaths in India finds that suicide is an important cause of avoidable deaths particularly among young adults aged 15–29 years. Studies from high-income countries typically report male: female suicide death ratios reaching 3 to 1.18 We noted that the male: female suicide death ratio was about 1·5 to 1 at all ages, and roughly equal among young adults. The age-standardised suicide rate at ages 15 years and older among Indian women is more than 2·5 fold greater than women in high-income countries1 and nearly as high as those seen in China.1, 19 The suicide rate at ages 15 years and older among men also exceeds those for men in high-income countries, but to a smaller degree.20 Given steady declines in maternal mortality from 1997–2009,21 suicide will likely become the leading cause of death in young women in India in the next few years. Although most suicides occur in rural areas, they are as frequently observed amongst other professions as they are among agricultural workers, including farmers (Web appendix p 2).

The estimated national total of suicide (187 000 at ages 15 years and older, lower and upper bounds of 160 000 to 200 000) is within the uncertainty ranges of WHO’s indirect estimates based on disease models (about 170 000 in 2004).1 The regional suicide death rates are also broadly consistent with, or lower than, the death rates observed in smaller regional studies, most of which are from South India.22–25 The suicide totals and death rates are, as expected, much higher than those reported from official police crime statistics. Comparison with our data suggest that NCRB under-estimates suicides in men and women by at least 25% and 36%, respectively, with much of the under-reports occurring among the young and older females (Web appendix pp 1, 3). The major method of suicide was poisoning, most commonly from use of organophosphate pesticides used in agriculture, as noted in other Asian countries.26 Suicide death rates were higher in rural than in urban India, perhaps due to higher availability of pesticides combined with poorer access to emergency medical care in the rural areas.27

The southern states have a nearly a ten fold higher age-standardised suicide death rate than the some of the northern states. The South-North gradient persisted despite adjustment for education, religion, and mode of suicide (poisoning). The marked regional variations we have observed in our study are, however, much less extreme than those reported by the NCRB.28 Misreporting of suicides as homicides is unlikely to explain these sharp regional differences (Web appendix p 1). Furthermore, most suicide deaths in each of the southern states were reported in the local language and not in Hindi or English or other regional languages from adjacent states (data not shown). This suggests that migration does not explain the higher rates of suicide in each of these southern states. Studies from South India have shown that the most common contributors to suicide are a combination of social problems, such as interpersonal and family problems and financial difficulties, and pre-existing mental illness.29–31 Suicidal ideation in Puducherry (near Tamil Nadu) is reported to be more common than most other countries.32 The high suicide rates in South India might therefore be partly attributed to a combination of prevalent suicidal thinking or planning and social acceptance of suicide as a method to deal with difficulties,33 paired with access to pesticides.

Suicide death rates were greater in the richer states (many of which are in the South) and among those with higher levels of education. In contrast, suicide death rates are greater among the less educated in high-income countries.29, 34–35 Curiously, we observed a reduced risk of suicide versus other causes of death in women who were widowed, divorced or separated compared to married women, a finding consistent with China, but in contrast with the higher risks of suicide reported among the formerly-married in the United States.36 Some of these differences may, in part, be attributed to the fact that our controls for the risk factor analyses were people who had died from causes other than suicide and not living controls.

The study has certain limitations. First, we might have under estimated suicide deaths, particularly among females. Suicide remains a crime in India, and suicides of married young women are particularly sensitive given that her husband or his family are potentially held responsible if the suicide occurs within seven years of marriage. However, the SRS field surveyors are well known in these communities as they visit the areas every six months. Moreover, field surveyors were trained not to ask obviously embarrassing questions, but rather to rely on narrative histories from all available respondents. The slightly lower specificity than sensitivity of the re11 sampled suicide deaths might be expected; the resurvey teams were less well known to the community than were the SRS field staff. This implies stigma in reporting of suicides applied also in our study, which would lead to underestimating the suicide totals for India. Second, some suicide deaths might have been misclassified on the verbal autopsy as unintentional deaths, especially for poisoning deaths, and burns in women37. However, the variation in suicide rates between states was not correlated with the proportion of deaths from accidents or homicide (Web appendix p 1). Moreover, the absolute numbers of homicide and burn deaths were small, suggesting that any misclassification in either direction would only marginally alter the national estimates of suicide deaths. Third, unlike in the NCRB, we did not classify the few HIV-associated suicides as suicides, which we classified as HIV deaths.8 Fourth, the NCRB police reports a 2·5% annual increase in reported suicides from 2006 to 2010.28 If this increase represents a true increase in the incidence of suicide, then the national totals for 2010 would be under estimates. However, the NCRB trend might simply reflect a small correction of the noted large levels of under-reporting in earlier years. Indeed, the age-specific patterns in the NCRB have changed little from 2000 to 2010 as might be expected if suicide incidence were changing. Also, the proportions of suicide to total deaths in selected urban hospitals38 appear to have been stable from 1999 to 2004. There have been few public health initiatives on suicide,4 which might be expected to increase reporting. Finally, the projection to 2010 does not introduce major biases as use of 2004 and 2010 UN totals yielded similar results (data not shown).

In summary, suicide is a leading cause of death of young people in India. It causes about twice as many deaths as HIV/AIDS,8 and is on par with maternal causes of death for young women.21 However, unlike these two other conditions, suicide attracts little public health attention. Most Indians lack community and support services for the prevention of suicide and have limited access to care for mental illnesses associated with suicide, particularly access in primary to the treatment of depression which has been shown to reduce suicidal behaviours.39 Reductions in harmful alcohol drinking through regulations, higher alcohol taxation or brief interventions in primary care might also reduce suicides in men as well as violence against women, a determinant of suicide in women.31, 40–41 In the medium term, the most practicable strategy would be to reduce access to organophosphate pesticides along with public education to improve acceptance of restrictions to access.42 Urgent research is needed to explore the reasons for suicide in young people and the large regional variations observed in the study, and these should be paired with the implementation of a comprehensive, and evidence-based suicide prevention strategies.43

Supplementary Material

Panel: Research in context.

Systematic review

In a systematic review of PubMed with research terms “India” [abstract] AND “suicide” [abstract] AND “rates” OR “estimates” [all fields], we identified 58 studies from 1976 to 2010, of which 51 were published after 1990. Only three studies used national data.41, 44–45 There were 11 small scale studies in the above identified studies. The remaining studies were comments, correspondence, editorials or studies comparing trends/rates with other countries. No studies were available that provide nationally representative data on rates and estimates for India.

Interpretation

This study is the first to provide nationally-representative estimates and rates of suicide deaths among males and females of India. We estimated the age and gender specific suicide deaths and suicide death rates for India, for major states and for rural and urban India. We observed that suicide is an important cause of avoidable deaths in India particularly among young adults. Suicide rates for both genders are higher in rural areas than in urban areas and rates are remarkably varied between states. Poisoning was the leading method used in suicides. Higher education as well as residency in South of India was significantly associated with suicide.

Acknowledgements

Supported by grants from the John E. Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health (R01-TW05991–01 and TW07939-01); as well as the Canada Research chair program and University of Toronto (to Dr. Jha); and the Wellcome Trust (Grant 091834/Z/10/Z to Dr. Patel). The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Government of India or the Office of the Registrar General. We thank the Office of the Registrar General for the productive collaboration on the Million Death Study; D. Gunnell, A.S. Slutsky and A. Wong for their helpful comments on the manuscript, C. Mathers for providing WHO mortality estimates, and S. Gambhir and B. Pezzack for graphics.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo co pyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

PJ and the academic partners in India (RGI-CGHR Collaborators) planned the Million Death Study in close collaboration with the Office of the Registrar General of India. VP, CR and PJ did the statistical analyses. All authors were involved with data interpretation, critical revisions of the paper, and approved the final version; PJ is its guarantor.

Conflicts of interest

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO; 2008. The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 update. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Crime Records Bureau. New Delhi: Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India; 2008. Accidental deaths and suicides in India. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mishra S. Farmers suicide in Maharashtra. Economic and Political Weekly. 2006 Apr 22nd;:1538–1545. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel V, Chatterji S, Chisholm D, Ebrahim S, Gopalakrishna G, Mathers C, et al. Chronic diseases and injuries in India. Lancet. 2011 Jan 29;377(9763):413–428. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61188-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jha P, Gajalakshmi V, Gupta PC, Kumar R, Mony P, Dhingra N, et al. Prospective study of one million deaths in India: rationale, design, and validation results. PLoS Med. 2006 Feb;3(2):e18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jha P, Jacob B, Gajalakshmi V, Gupta PC, Dhingra N, Kumar R, et al. A nationally representative case-control study of smoking and death in India. N Engl J Med. 2008 Mar 13;358(11):1137–1147. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0707719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Registrar General of India and Centre for Global Health. New Delhi: Government of India; 2009. Causes of death in India, 2001–2003 Sample Registration System. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jha P, Kumar R, Khera A, Bhattacharya M, Arora P, Gajalakshmi V, et al. HIV mortality and infection in India: estimates from nationally representative mortality survey of 1.1 million homes. BMJ. 2010;340:c621. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhingra N, Jha P, Sharma VP, Cohen AA, Jotkar RM, Rodriguez PS, et al. Adult and child malaria mortality in India: a nationally representative mortality survey. Lancet. 2010 Nov 20;376(9754):1768–1774. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60831-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dikshit R, Gupta PC, Ramasundarahettige C, Gajalakshmi V, Aleksandrowicz L, Badwe R, Kumar R, Roy S, Suraweera W, Bray F, Mallath M, Singh PK, Sinha DN, Shet AS, Gelband H, Jha P for the Million Death Study Collaborators. Cancer mortality in India: a nationally representative mortality survey. Lancet. Lancet. 2012 Mar 28; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60358-4. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinha D, Dikshit R, Kumar V, Gajalakshmi V, Dhingra N, Seth J. Technical document VII: Health care professional's manual for assigning causes of death based on RHIME household reports. Toronto: Centre for Global Health Research, University of Toronto; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar R, Thakur JS, Rao BT, Singh MM, Bhatia SP. Validity of verbal autopsy in determining causes of adult deaths. Indian J Public Health. 2006 Apr-Jun;50(2):90–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joshi R, Cardona M, Iyengar S, Sukumar A, Raju CR, Raju KR, et al. Chronic diseases now a leading cause of death in rural India--mortality data from the Andhra Pradesh Rural Health Initiative. Int J Epidemiol. 2006 Dec;35(6):1522–1529. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mari Bhat PN. Completeness of India's sample registration system: an assessment using the general growth balance method. Population studies. 2002 Jul;56(2):119–134. doi: 10.1080/00324720215930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sivanandan V. An assessment of the completeness of death registration in India over the periods 1975–1978 and 1996–1999 under the generalized population model: an analysis based on SRS data Mumbai, India. Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gajalakshmi V, Peto R, Kanaka S, Balasubramanian S. Verbal autopsy of 48 000 adult deaths attributable to medical causes in Chennai (formerly Madras), India. BMC Public Health. 2002 May 16;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cantor CH. Suicide in the Western World. In: Hawton K, van Heeringen K, editors. International handbook of suicide and attempted suicide. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons; 2000. pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips MR, Li X, Zhang Y. Suicide rates in China, 1995–99. Lancet. 2002 Mar 9;359(9309):835–840. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07954-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.WHO. [Access 8th August 2011]; http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide_rates/en/. [cited; Available from:

- 21.Registrar General of India. [Accessed 8th August, 2011]; http://www.censusindia.gov.in/vital_statistics/SRS_Bulletins/Final-MMR%;20Bulletin-2007-09_070711.pdf. [cited; Available from:

- 22.Gajalakshmi V, Peto R. Suicide rates in rural Tamil Nadu, South India: verbal autopsy of 39 000 deaths in 1997–98. Int J Epidemiol. 2007 Feb;36(1):203–207. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aaron R, Joseph A, Abraham S, Muliyil J, George K, Prasad J, et al. Suicides in young people in rural southern India. Lancet. 2004 Apr 3;363(9415):1117–1118. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15896-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joseph A, Abraham S, Muliyil JP, George K, Prasad J, Minz S, et al. Evaluation of suicide rates in rural India using verbal autopsies, 1994–9. Bmj. 2003 May 24;326(7399):1121–1122. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7399.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abraham VJ, Abraham S, Jacob KS. Suicide in the elderly in Kaniyambadi block, Tamil Nadu, South India. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005 Oct;20(10):953–955. doi: 10.1002/gps.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gunnell D, Eddleston M. Suicide by intentional ingestion of pesticides: A continuing tragedy in developing countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:902–909. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jha P, Laxminarayan R. Choosing Health : An entitlement for all Indians. Toronto: Centre for Global Health Research; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Crime Records Bureau. Accidental deaths and suicides in India 2010. New Delhi: National Crime Records Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manoranjitham SD, Rajkumar AP, Thangadurai P, Prasad J, Jayakaran R, Jacob KS. Risk factors for suicide in rural south India. Br J Psychiatry. 2010 Jan;196(1):26–30. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.063347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vijayakumar L, Rajkumar S. Are risk factors for suicide universal? A case-control study from India. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1999;(99):407–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb00985.x. 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maselko J, Patel V. Why women attempt suicide: the role of mental illness and social disadvantage in a community cohort study in India. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008 Sep;62(9):817–822. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.069351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borges G, Nock MK, Haro Abad JM, Hwang I, Sampson NA, Alonso J, et al. Twelve-month prevalence of and risk factors for suicide attempts in the world health organization world mental health surveys. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010 Aug 24;71(12):1617–1628. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04967blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manoranjitham S, Charles H, Saravanan B, Jayakaran R, Abraham S, Jacob KS. Perceptions about suicide: a qualitative study from southern India. Natl Med J India. 2007 Jul-Aug;20(4):176–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rehkopf DH, Buka SL. The association between suicide and the socio-economic characteristics of geographical areas: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2006 Feb;36(2):145–157. doi: 10.1017/S003329170500588X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phillips MR, Yang G, Zhang Y, Wang L, Ji H, Zhou M. Risk factors for suicide in China: a national case-control psychological autopsy study. Lancet. 2002 Nov 30;360(9347):1728–1736. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11681-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Borges G, Nock M, Wang PS. Trends in suicide ideation, plans, gestures, and attempts in the United States, 1990–1992 to 2001–2003. JAMA. 2005 May 25;293(20):2487–2495. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jagnoor J, Ivers R, Kumar R, Jha P. Fire-related deaths in India: how accurate are the estimates? Lancet. 2009 Jul 11;374(9684):117. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61287-3. author reply 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Registrar General of India. New Delhi Government of India; 2007. Medically-Certified Causes of Death, Statistical Report: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patel V, Weiss HA, Chowdhary N, Naik S, Pednekar S, Chatterjee S, et al. The effectiveness of a lay health worker led collaborative stepped care intervention for depressive and anxiety disorders on clinical, suicide and disability outcomes over 12 months: the Manas cluster randomized controlled trial from Goa, India. British Journal of Psychiatry. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jacob KS. The prevention of suicide in India and the developing world: the need for population-based strategies. Crisis. 2008;29(2):102–106. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.29.2.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayer P, Ziaian T. Suicide, gender, and age variations in India. Are women in indian society protected from suicide? Crisis. 2002;23(3):98–103. doi: 10.1027//0227-5910.23.3.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gunnell D, Fernando R, Hewagama M, Priyangika WD, Konradsen F, Eddleston M. The impact of pesticide regulations on suicide in Sri Lanka. Int J Epidemiol. 2007 Dec;36(6):1235–1242. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patel V. Commentary: preventing suicide: need for a life course approach. Int J Epidemiol. 2007 Dec;36(6):1242–1243. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lester D, Natarajan M, Agarwal K. Suicide in India. Archives of Suicide Research. 1999;5(2):91–96. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mayer P. Female equality and suicide in the Indian states. Psychological reports. 2003 Jun;92(3 Pt 1):1022–1028. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2003.92.3.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.