Abstract

Rising rates of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection among adolescents and young adults underscore the importance of interventions for this population. While the morbidity and mortality of HIV has greatly decreased over the years, maintaining high rates of adherence is necessary to receive optimal medication effects. Few studies have developed interventions for adolescents and young adults and none have specifically been developed for sexual minority (lesbian, gay, and bisexual; LGB) youth. Guided by an evidence-based adult intervention and adolescent qualitative interviews, we developed a multicomponent, technology-enhanced, customizable adherence intervention for adolescents and young adults for use in a clinical setting. The two cases presented in this paper illustrate the use of the five-session positive strategies to enhance problem solving (Positive STEPS) intervention, based on cognitive-behavioral techniques and motivational interviewing. We present a perinatally infected heterosexual woman and a behaviorally infected gay man to demonstrate the unique challenges faced by these youth and showcase how the intervention can be customized. Future directions include varying the number of intervention sessions based on mode of HIV infection and incorporating booster sessions.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, adherence, adolescents, intervention, problem solving, technology, case study

About 76,400 adolescents and young adults ages 13–24 years are living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in the United States and 60% of these youth are unaware of their diagnosis (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012a). New HIV infection rates among youth (ages 13–24) are rising with recent U.S. data indicating that an estimated 12,200 youth received a diagnosis of HIV in 2010 (accounting for 26% of all new HIV infections), a 132% increase from estimated diagnosed cases in 2006 (n = 5,259; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012b).

Antiretroviral medications have resulted in significant declines in HIV-associated morbidity and mortality (Kapogiannis et al., 2011; Patel et al., 2008). Thus, adolescents and young adults infected with HIV now have the ability to manage their HIV infection as a chronic illness rather than an imminently life-threatening disease. Steadfast HIV medication adherence also has important implications for secondary prevention of HIV (Reisner et al., 2009). However, a recent review showed that across 21 studies published between 1999 and 2008, HIV medication adherence among adolescents ranged from 28 to 69%, much lower than the 90–95% needed to optimize treatment gain (Reisner et al., 2009). Thus hypothetically, a patient on a one-pill, once-a-day regimen should ideally miss no more than three to five pills over a month in order to experience the maximum benefit of the antiretroviral medication (Bangsberg, 2006; Shuter, Sarlo, Kanmaz, Rode, & Zingman, 2007).

Many behaviors associated with adherence (e.g., taking medications at the same time every day and not skipping any doses) are especially challenging for young people with HIV who may not be motivated to prioritize medications over competing demands of social schedules (McKinney et al., 2007). Furthermore, adolescents and young adults are particularly at risk given that their typical developmental trajectory involves behavioral experimentation, engagement in risk-taking behaviors, and balancing a range of difficult and complex choices regarding independence from families, romantic relationships, sexual behavior, substance use, and identity formation (Arnett, 2000). These developmental hurdles are particularly challenging for youth living with HIV because optimal adherence requires youth to independently manage their HIV while continuing to balance being a “normal teenager.” Yet complete adherence often requires taking medications at the same time each day, planning ahead so that schedule changes do not get in the way of taking medications as prescribed, and preventing any normative adolescent behaviors (e.g., peer relationships, substance experimentation, and sexual behaviors) from impeding adherence. HIV-positive adolescents and emerging adults have to negotiate typical development within the framework of a chronic and stigmatizing disease in which they risk being “outted” about their status and discriminated against if their HIV status becomes known (DeLaMora, Aledort, & Stavola, 2006). Medication adherence among these youth may be particularly challenging at a time of life when adolescents rely heavily on peers for social support and do not want to be perceived as different (Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents, 2008). Further, developmental cognitive processes, such as concrete thinking and partially developed abstract reasoning, may contribute to difficulties in taking medications when adolescents are asymptomatic, particularly if the medications have adverse side effects and differentiate them from peers.

Given these considerations, the most promising strategies for improving treatment adherence among HIV-infected adolescents and young adults may involve multiple components such as patient education, self-monitoring, and medication-taking reminders. This is consistent with adult adherence interventions, where multicomponent strategies tend to be most effective in improving adherence (Amico, Harman, & Johnson, 2006; Simoni, Frick, Pantalone, & Turner, 2003). There is a paucity of interventions aimed at improving adherence among adolescents and young adults. Two interventions were fairly resource intensive as they were conducted in patients’ homes and involved elements of directly observed therapy, raising concerns about sustainability (Berrien, Salazar, Reynolds, & McKay, 2004; Gaur et al., 2010). Other interventions addressed only one aspect of adherence—pill swallowing (Garvie, Lensing, & Rai, 2007) and text message reminders (Dowshen, Kuhns, Johnson, Holoyda, & Garofalo, 2012). Only three adolescent interventions that incorporated education and skills building have been tested, yielding modest effects (Lyon et al., 2003; Rogers, Miller, Murphy, Tanney, & Fortune, 2001; Shegog, Markham, Leonard, Bui, & Paul, 2012). Furthermore, we were unable to find any adolescent-focused HIV adherence interventions that were designed to address stressors unique to lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) adolescents, who likely experience additional stress, given the intersection of stigma from sexual orientation and HIV.

We developed an adolescent-focused multicomponent intervention that incorporated technological aspects (e.g., short message service [SMS] text messages and video vignettes)—positive strategies to enhance problem solving (Positive STEPS), which was guided by an evidence-based adult HIV medication adherence intervention—Life-Steps (Safren, Otto, & Worth, 1999; Safren et al., 2001). Life-Steps is based on principles of cognitive-behavioral therapy (Butler, Chapman, Forman, & Beck, 2006), motivational interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 2002), and problem solving (D’Zurilla, 1986; Nezu & Perri, 1989). It addresses 11 informational, problem-solving, and cognitive-behavioral steps, targeted over five, in-person intervention sessions with a master’s-level counselor. During each of the five intervention sessions, patients and the counselor define the problem impacting adherence, generate alternative solutions, make decisions about the alternatives, and collaboratively decide on a plan regarding how to implement the solutions. Problem-solving training serves to teach patients how to take an overwhelming task and break it into manageable steps with the goal of reducing cognitive avoidance (D’Zurilla, 1986).

The Positive STEPS manual development was guided by the 11 Life-Steps with modifications based on information obtained from adolescent qualitative interviews in the first phase of this study (Fields et al., under review). Specifically, we conducted 30 formative qualitative interviews with adolescents and young adults agsd 13–24 to explore barriers to HIV medication adherence. We specifically oversampled for LGB and transgender youth (n = 14) in order to explore potentially unique adherence barriers and facilitators. Consistent with prior research (MacDonell, Naar-King, Huszti, & Belzer, 2013), our findings revealed barriers to adherence that were consistent across many of the adolescents and young adults in our study, including poor risk perception about the potential consequences of nonadherence, seeing medication as a reminder of HIV status, having irregular daily schedules, concern about HIV stigma, lack of social support, poor mental health, and experiencing side effects from the medications. We also found barriers unique to perinatally infected youth including nondisclosure, opposition to instructions (i.e., reactance), complicated medication regimens, fatigue from chronicity of HIV, and balancing transition to managing their own HIV care. Barriers unique to behaviorally infected youth include self-blame, shame, stigma, and greater control over HIV medication initiation that could lead to choosing not to initiate treatment. LGBT youth were also more likely to identify barriers associated with internalized stigma (i.e., self-blame for HIV infection) and were more likely to have been newly diagnosed with HIV (Fields et al., under review).

In addition to incorporating techniques from Life-Steps and information from our qualitative interviews about unique factors affecting adherence among perinatally infected, behaviorally infected, and LGB youth, this intervention responds to the increasingly widespread use of technology among adolescents. Only two studies to date have examined the use of technology to improve HIV treatment adherence in adolescents and young adults. One recent feasibility study of personalized daily SMS reminders significantly improved self-reported adherence among adolescents and young adults (Dowshen et al., 2012). The other adolescent-focused pilot study, which involved a tailored, Web-based training program addressing attitudes, knowledge, skills, and self-efficacy related to adherence, showed some improvement in psychosocial outcomes but did not assess the impact on adherence (Shegog et al., 2012).

The aim of Positive STEPS is to address adolescent-specific barriers to HIV medication adherence among heterosexual and LGB, perinatally and behaviorally infected youth. In this paper, we present an overview of the intervention and two case studies (selected from our sample of participants in our small pilot randomized controlled trial [RCT]). Cases were chosen to represent the variability in our study sample across mode of infection, sexual orientation, race, and gender.

Intervention Approach

Positive STEPS Session Structure

Positive STEPS involves five 1-hour individual sessions, designed to be implemented by master’s- or doctoral-level clinicians. The sessions involve customized problem-solving strategies that address adherence barriers (see Table 1) using the GOAL acronym: G—describe your adherence goals, O—list obstacles and options to reaching your goal, A—make an action plan, and L—look back at your plan and look forward to alternatives (i.e., backup plan). Compared with the original Life-Steps (Safren et al., 1999), which addressed eight adherence barriers with adults over one session, Positive STEPS uses five sessions to explore how 11 adherence barriers (new modules on managing mood, social life, privacy and disclosure, and independent HIV care) uniquely interact with adolescent development.

Table 1.

Positive STEPS Session-by-Session Content Overview

| Session | Content |

|---|---|

| Session 1: Introduction to Positive STEPS |

|

| Session 2: Logistics and HIV Care |

Video: Taking Notes and Asking Questions at the Doctor’s Office |

| Session 3: Coping With HIV |

Video: Trying to Stay on a Medication Schedule |

| Session 4: Privacy, Social Support, and HIV |

Video: Stigma and Debate About Disclosing HIV Status |

| Session 5: Handling Adherence Slips and Wrap-Up |

Video: Multiple Strategies for Adherence |

Each Positive STEPS session includes videos depicting patient testimonials that match some of the steps, including testimonials on being assertive with providers, sticking to a medication schedule, dealing with stigma, making decisions about disclosure, and using multiple adherence strategies. After the clinician showed the videos to the patient, they would engage in a discussion about the specific issues raised in the video and the potential impact on the patient’s adherence. Patients were usually highly engaged watching the videos and ideas discussed were related back to their adherence goals. To customize our intervention for LGB youth, we selected some videos of LGB youth and addressed disclosure in same-sex relationships. All videos are publicly available and we received permission for use in our intervention. All 11 steps are introduced to patients but only explored in detail if the barrier is relevant to their own adherence pattern. Every patient is taught coping tools (goal setting, note cards to track questions for medical visits, relaxation and guided imagery, and cue-controlled reminders), watches and discusses the testimonial videos, and receives psychoeducation on the importance of adherence and ways to handle future slips in adherence. Customized text messages are chosen by the participant during the first session and sent according to his or her medication dosage. Text messages are discontinued 2 weeks prior to the end of the study. Each session begins with a review of the patient’s adherence pattern from the previous week, discussion of potential contributors to missed or late doses (if any), problem-solving ways to prevent future missed doses, and review of the previous session. The clinician ends each session by helping the patient draw a connection between the adherence barriers covered and his or her general life “values” (specific factors that motivate the patient), setting up “action items” (adherence-related tasks to work on the following week), and scheduling the next session.

The structure of Positive STEPS allows each patient to address unique barriers that affects his or her own adherence. Our goal was to develop an intervention that was customized to each patient regardless of race, gender, sexual orientation, or mode of HIV infection. By conducting formative qualitative work, we were able to strategically inform the adaptation of our intervention ensuring that topics of concern and relevance to various groups of adolescents by race, gender, sexual orientation, or mode of infection were captured. Our formative work also ensured that potential responses on ways to address issues raised by youth from various groups were also prepared ahead of time and included in the intervention development materials so that study clinicians could address these issues, if raised by patients.

Positive STEPS Session Outline

Session 1

This first session (for a session-by-session overview, see Table 1) begins by raising patients’ awareness about the importance of adherence and aims to evoke intrinsic motivation for adherence. The clinician attempts to gain an understanding of the context in which patients live and explore general life values that not only guide their everyday decision making but could also be linked to reasons to adhere to their antiretroviral therapy (ART). The focus on youth-based motivators for behavior change stemmed from our qualitative study, which guided intervention development. Specifically, youth expressed opposition to instruction from adults (i.e., reactance). Accordingly, rather than tell participants why we thought they should adhere to their medication regimen, we asked youth to generate their own list of adherence motivators. We used value cards (Naar-King & Suarez, 2011), which are sorting cards that represent an array of common psychosocial factors/values that could serve as motivators for behavior change (see Table 2), and asked patients to rank their most and least important values (see Demonstration Video 1). The clinician then associates the most important values with participants’ adherence and reminds patients to focus on these values throughout the intervention as a strategy to maintain their adherence goals. For example, when working on a specific barrier to adherence, the clinician would say things like “I know ‘making smart decisions’ (sample value) is important to you; how do you think leaving your medications at home (sample barrier) is preventing you from making smart decisions about your health?”

Table 2.

Values Assessed During the Value Card Activity

| Belonging |

| Contributing to my society |

| Courage |

| Creativity |

| Education |

| Employment |

| Family |

| Financial security |

| Friends |

| Fun |

| Happiness |

| Health |

| Helping others |

| Honesty |

| Hope |

| Humor |

| Making others proud |

| Making smart decisions |

| My culture |

| Open-mindedness |

| Personal independence |

| Privacy |

| Respect |

| Safety and security |

| Self-esteem |

| Sexuality |

| Spirituality |

| Staying fit |

| Success |

| To love and be loved |

Negative and positive pill associations are also explored such that medications are not only seen as a reminder of their HIV status (negative association) but also as a means to a healthier life (positive association). The clinician asks patients to describe their thoughts and emotions while looking at their medications, and then they discuss reasons for and against taking their medications. To decrease participants’ poor risk perception about the consequences of nonadherence, we used an animated psychoeducation tool that teaches participants about the benefits of consistent adherence to ART. This Adherence Brick Animation, which was developed in prior research (Finocchario-Kessler et al., 2012), was adapted and animated for this intervention to render it more teen-friendly and to teach adolescents what happens to their immune system when they do not take their medications as prescribed. This activity typically spurs a rich discussion about the importance of taking medication every day and on time. Many participants also expressed their appreciation for learning about adherence in such a clear and visually concise way (see Demonstration Video 2 for further details).

The adherence goal worksheet is used to help patients identify unique barriers that affect their adherence and set collaborative adherence goals. The session closes with an introduction to GOAL, a description of the 11 steps, and exploration of their typical daily routine in order to identify optimal times to take their medications. Last, patients work with the clinician to develop personal messages to be sent daily to their phones as a reminder to take their medications. Sample messages include “It’s about that time,” “Stick with it!” and “You are worth it.” Messages were carefully screened to ensure no protected health information (such as patients’ HIV status) was revealed. Patients were also encouraged to set a cell phone alarm reminder, if they so desired.

Session 2

This session addresses logistical barriers to adherence, including issues related to taking medications, medication fatigue, chronicity of being HIV positive, and complicated medication regimens. Using GOAL, three steps are explored: getting to appointments (getting to all medical appointments when scheduled), getting medications (ordering and picking up prescribed HIV medications; see Demonstration Video 3), and talking with my treatment team (addressing issues and being assertive with medical providers). The clinician helps patients understand that a positive relationship with their treatment team can help them overcome many barriers to adherence. Patients are also shown a testimonial video, Taking Notes and Asking Questions at the Doctor’s Office, of a young adult modeling how to be a self-advocate at medical appointments. Patients are taught to use 3 × 5 note cards to keep track of questions they want to ask their medical providers.

Session 3

This session addresses adolescent-focused attitudinal barriers that were identified by youth in our formative qualitative work including having irregular daily schedules, experiencing medication side effects, and mood lability as it affects adherence. The clinician begins the session by exploring how patients’ experience with side effects can prevent them from wanting to take their medications as prescribed (Coping With Side Effects step). A testimonial video, Trying to Stay on a Medication Schedule, is used to introduce the next step and emphasize the value of consistency in adherence. In the testimonial video, an adolescent describes her experience trying to maintain a medication routine in the face of complex daily challenges and inconsistent schedules. In the second step, Having a Daily Medication Schedule, patients explore how planned and unplanned activities may affect their own adherence. This addresses qualitative themes raised around adolescents’ struggles maintaining a consistent daily schedule and how taking medications at the same time each day did not fit into that varied schedule. The final step—Managing Mood and Adherence, is used to help patients explore how their positive and negative emotions can influence their decisions to adhere to their medications. The Relaxation and Guided Imagery coping tool is introduced to help patients manage stress and build positive associations related to their medications (i.e., patients’ picture themselves taking their medications while thinking positive thoughts about the medications during a relaxed state). Patients are given a recording (see Audio Link) of the relaxation exercise to continue practicing the skill outside of the intervention session.

Session 4

This session focuses on social influences on medication adherence. The clinician uses the step on Managing My Social Life and Friends to engage patients in discussions about how relationships with friends and their social activities positively or negatively influence their medication adherence and the role of social support in adherence. In qualitative interviews, youth raised concerns about HIV stigma, self-blame about HIV infection, and reluctance to stand out from peers, which tended to result in limited disclosure of their HIV status. In the intervention, we present a testimonial video, Stigma, in which an HIV positive young adult describes his experience with feeling isolated. This video is used as an entryway into discussions about strategies to prevent stigma and self-blame from getting in the way of adherence. The next step on Storing/Transporting Medications explores how adherence can be affected by accessibility to medications and forgetting to take the medications (a theme raised in the qualitative study). Cue-Control Strategies are introduced to help patients identify unique strategies to remind them to take their medications including using stickers placed in strategic places as reminders to take medications; associating positive thoughts, images, and statements with the stickers as a reminder to stay focused on the positive; and using overt reminders such as pill boxes with built-in alarms, watch timers, or linking pill taking with daily activities such as brushing teeth. The step Dealing With Privacy/Disclosure Issues helps patients identify how privacy and lack of disclosure can contribute to nonadherence (see Demonstration Video 4). The testimonial video, Debate About Disclosing HIV Status, normalizes the struggles related to decision making about how to disclose one’s HIV status by showcasing two HIV-positive young adults debating the pros and cons of disclosing one’s status to a partner.

Session 5

The final session addresses concerns about transition to adult care and maintenance of adherence skills. The session begins with the Taking Care of My Own HIV step, which focuses on challenges patients face in transitioning management of HIV care from their guardian to themselves and struggles with transitioning to adult care providers. The Handling Slips in Adherence step helps patients learn how to handle any future missed doses and problem solve ways to get back on track and avoid falling into complete nonadherence (i.e., preventing a lapse in adherence from becoming a relapse to complete nonadherence). The Improvement Graph (see Figure 1), which is a graph that illustrates the gradual progression of improving one’s adherence over time thereby normalizing the likelihood of future missed and late doses, encourages patients not to be disheartened by adherence slips. The testimonial video, Multiple Strategies for Adherence, wraps up the session by showing a young adult discussing several strategies for maintaining adherence and emphasizes the importance of social support and responsibility for one’s own HIV care.

Figure 1.

Adherence improvement graph.

Procedure

Overview of Positive STEPS Protocol

Participants were recruited during outpatient clinic visits from two sites: a local children’s hospital and community health center. Institutional Review Boards at both institutions approved this study. All participants over age 18 provided written informed consent and participants under age 18 provided oral assent while their parents/guardians provided written consent. Participants were screened and enrolled if they met eligibility criteria: 13 to 24 years old, HIV positive, and missed at least one dose within the last month. Once enrolled, assessments were conducted in-person by research assistants (who were not involved with intervention implementation). At baseline and follow-up (approximately 14 weeks after baseline), participants were administered questionnaires via audio computer-assisted self-interviews. During their baseline appointment, participants were given an electronic pill bottle cap (described below) to monitor their adherence. Approximately 2 weeks after their baseline appointment, participants were randomized into either the control or intervention arm of the study.

Measures

Demographics

Participants were asked to report their age, educational level, employment status, race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and mode of HIV transmission.

Adherence

Adherence to HIV medications were electronically monitored using Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS) and provided by self-report. The MEMS (AARDEX, Inc., Zurich, Switzerland) consists of medication bottle caps that record the exact times when medication bottles are opened. The MEMS software yields detailed reports of daily medication-taking patterns and allows for calculation of the percentage of total scheduled doses taken in a format suitable for conversion into a statistical analysis package. Participants were given the MEMS bottle caps at the baseline assessment and asked to bring them back to each visit. Participants were also instructed to refill the bottle after they removed the last pill. MEMS readings were collected during each participant contact (i.e., baseline, intervention sessions, and follow-up). Participants were asked by a study team member at the beginning of each interview and session if there were any corrections to be made to the MEMS reading (i.e., assessing whether and how often they opened the bottle without removing a dose, took a dose from a source other than the bottle with the electronic cap, and removed multiple doses from the bottle at a time). Consistent with previous research (Bangsberg et al., 2000), we used participants’ responses to adjust electronic adherence scores to accurately reflect actual pill-taking behavior.

Self-report adherence was assessed using a one-item measure based on previous research (Berg, Wilson, Li, & Arnsten, 2012). “Thinking about the last month, on average how would you rate your ability to take all your HIV antiretroviral medications as your doctor prescribed?” Response options ranged from 1 (very poor) to 6 (excellent).

Medication Readiness

Participants’ readiness to take medications was assessed with a 10-item scale, values ranging from 0 (not at all ready) to 4 (completely ready). Previous research showed that this scale is predictive of adherence after 1 month of treatment and has high internal consistency (α = 0.90; Balfour et al., 2007). Responses are summed with total scores ranging from 0 to 40 with higher scores indicating greater readiness to take medications.

Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D)

The CES-D (Radloff, 1977) is a 20-item questionnaire used to measure depressive symptoms during the past week. This screening scale has been extensively used to examine depression among persons living with HIV (Griffin & Rabkin, 1997). Items were scored from 0 to 3 and summed, with higher scale scores indicating more depressive symptoms. Internal consistency reliability across studies ranges from 0.85 to 0.90 (Radloff, 1977).

Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS)

The SAS was used to assess anxiety (Zung, 1971). Participants reported how frequently they experienced 20 symptoms during the past week on a scale ranging from 1 (none of the time) to 4 (most of the time). Scores range from 20 to 80 with standard cutoffs of 20–44 normal range, 45–59 mild–moderate, 60–74 marked–severe, and 75–80 extreme. Split half reliability was 0.71 (Zung, 1971).

Case Descriptions

Intervention Case 1: Patient Information and Relevant History

Sandra1 was an 18-year-old African American young woman who was in her first year at a local community college. She also worked part time and played sports at school. Sandra was perinatally infected with HIV and her mother and father died of AIDS when she was young. She was raised by relatives for the majority of her life; however, at the start of the intervention she had just moved out on her own. Sandra’s medication regimen included taking three pills, once a day.

Intervention Process

Sandra began the Positive STEPS intervention with the first author as the primary clinician. The modules used in Sandra’s treatment are shown in Table 3. Sandra’s self-identified reasons for missing two or more doses a week were because “I don’t want to get up” and “I don’t feel like taking it.” During the value card activity, she narrowed her most important values to “making others proud,” “making smart decisions,” and “success.” Sandra described numerous negative thoughts when she looked at her pills and reported feeling lack of motivation to take her medications because she had been taking them for so long. However, she also believed that she should take her medications because it was “important” and she did not want to get “sicker.” With the clinician’s guidance, Sandra successfully identified some adherence goals to work on during the intervention, including “Take my medications every day,” and “Attend more doctor visits.” Sandra worked with the clinician to create customized text message reminders and was encouraged to set a phone alarm as well.

Table 3.

Positive STEPS Treatment Modules for Case Examples

| Case 1—Sandra | Case 2—Bill | |

|---|---|---|

| Session 1 |

|

|

| Session 2 |

|

|

| Session 3 |

|

|

| Session 4 |

|

|

| Session 5 |

|

|

Over the course of the remaining four intervention sessions, it was apparent that Sandra’s difficulties with adherence stemmed around logistical barriers, managing her mood, and independent management of her HIV. While Sandra reported that she had been receiving the text messages, she typically ignored them; however, the phone alarm worked well because she indicated that she could not ignore the ringing alarm.

Sandra’s logistical barriers to adherence included difficulty getting to all her provider appointments, maintaining a daily medication schedule, and storing/transporting her medications when outside her home. Sandra reported missing provider appointments because she often was not in the mood to go, felt lazy, did not feel comfortable with the provider, was busy with work/school, or could not make the appointment time. However, she expressed interest in going to her appointments in order to learn how she was doing medically and because she believed the appointments were important for her health. This related well to Sandra’s values because she wanted to make smart decisions about her health and be successful at improving her adherence. Sandra worked with the clinician to select strategies to decrease these logistical barriers, including asking her providers for more flexibility with her appointment times and taking an active role in improving her adherence in order to decrease her avoidance of medical visits due to guilt associated with nonadherence.

Over the course of treatment, Sandra revealed that when her doctors tell her she is doing well medically she sometimes stops taking her medications. She also noted that she sometimes forgot to take her medications when planned or unplanned events occur (e.g., falling asleep before taking her medications or unexpectedly staying over at a friend’s house). She identified discomfort and need for privacy as a major obstacle to taking her medications at friends’ houses. Sandra reported discomfort taking a drink from a friend’s refrigerator without permission. The clinician explained the importance of creating a routine around her adherence, so that it becomes a part of her daily life even when visiting friends. Working together, the clinician and Sandra generated options to address these logistical adherence barriers including keeping an “emergency dose” in her backpack, taking her medications well before bedtime, and strategizing creative ways to take her medications when away from home such as bringing a drink with her to a sleepover, taking her medication with dinner so she would not have to ask for another drink, or using water from the bathroom tap to take her medications.

A major barrier to Sandra’s adherence revolved around her mood. Sandra reported feeling depressed, sleeping excessively, problems with fatigue, and low energy. She articulated that her mood often got in the way of taking her medications because she was sad and was experiencing fatigue from being HIV positive all her life. Sandra noted that having negative thoughts about her medications and feeling guilty about skipping doses previously led her to stop taking her medications completely. The clinician recommended individual therapy to address her mood symptoms; however, Sandra was highly reluctant about engaging in treatment. She agreed to write a pros and cons list about seeing a therapist; however, by Session 4 she still remained ambivalent about therapy, although she now acknowledged that her missed and late doses were typically triggered by her mood. Consistent with her challenges managing her mood, Sandra also struggled with disclosing her HIV status, despite awareness that lack of disclosure played a major role in her adherence. She reported that she does not take her medications with her when she leaves her home because of fear of people finding out about her diagnosis. We discussed potential options to addressing these obstacles including disclosing her status so she would not have to hide her medications, coming up with a story about what her medication is for (such as allergies), and keeping a water bottle with her so she can take medications in private.

During the final session, Sandra reported concerns about transitioning to adult care as she was not ready to leave her current provider because she had been seeing this provider for most of her life. She also described reliance on others to remind her to take her HIV medications. Sandra indicated that low motivation to take care of herself was a major obstacle to independent HIV management. She believed that changing her attitude and soliciting help from someone in her life to motivate and remind her to take her medications would be beneficial. The clinician and Sandra discussed her fears of transitioning care, including ways she could get support from her providers, in order to help her change her attitude about transition. We also explored the incongruence between her low motivation to take care of herself and her values of wanting to make others proud and wanting to make smart decisions. The potential role of therapy in helping Sandra take ownership over her own HIV care and in helping her live a value-driven life was again reinforced and Sandra finally agree to schedule an appointment with a therapist. The clinician and Sandra reviewed the importance of planning ahead for potential slips in adherence to prevent a lapse from becoming a relapse to complete nonadherence. Sandra stated that in the past when she missed a dose she would typically stop taking her medications for a long period of time because her emotions would get in the way of resuming her medication regimen. We identified options for not letting slips affect her long-term adherence including talking to someone when she begins to struggle with adherence and focusing on her personal values of making others proud, success, and making smart decisions. Sandra’s final action items were to schedule an appointment with a therapist to address her depressive symptoms, pay attention to cell phone reminders to take medications, and practice relaxation coping skills regularly.

Results

As illustrated in Figure 2, Sandra’s MEMS data showed that she took her medications fairly regularly for the first week and then dropped off significantly. Once she began the intervention her overall and on-time adherence improved; however, this improvement was not sustained after the intervention ended. Sandra’s self-report adherence improved such that she rated her adherence at 4 at baseline and 5 at follow-up. As Table 4 shows, Sandra not only expressed increased readiness to take her medications but during her involvement in the intervention her depression and anxiety symptoms, which were in the clinical range at baseline, showed marked improvement at follow-up. It appeared that although she had not yet begun individual mental health treatment, she benefited from meeting regularly with a clinician, further underscoring her need for ongoing individual therapy.

Figure 2.

Graph illustrating the weekly MEMS adherence data from baseline until follow-up for Sandra.

Table 4.

Psychosocial Scale Scores for Case Examples

| Case 1—Sandra | Case 2—Bill | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | Baseline | Follow-up | Baseline | Follow-up |

| Medication Readinessa | 25 | 33 | 32 | 31 |

| CES-Db | 43 | 11 | 8 | 11 |

| Zung Anxiety Scaleb | 68 | 28 | 29 | 31 |

Higher scores are better,

Lower scores are better.

Note: CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale.

Intervention Case 2: Patient Information and Relevant History

Bill1 was a 22-year-old White, young, gay man in his senior year in college. He worked part time and was actively involved in extracurricular activities at school, in addition to his regular classes. Bill had been living with HIV for 3 years after being infected via unprotected sexual intercourse with another man. He moved to town for college; consequently, he did not have family support in the area but had been able to build a strong peer support group. Bill’s medication regimen included taking two pills, twice a day, and one pill, once a day. He typically took his medications in the morning and late at night.

Intervention Process

The first author served as intervention clinician for Bill with modules covered shown in Table 3. Bill presented as very appreciative for his medication regimen because he had experienced some initial difficulty finding a regimen that worked for him due to allergic reactions to several HIV medications. His experience with providers taking so long to find a regimen that worked for him served as motivation for his adherence. Bill reported missing one to two doses a month and taking his medications at varied times because of his busy schedule. During the value card activity, Bill identified “humor,” “belonging,” and “success” as his three most important values. He reported that his medications triggered feelings of security and stability, and feelings that his pills were keeping him healthy and happy. During the interactive psychoeducation module on adherence, Bill noted that he was not previously aware of the importance of taking his medications at the same time each day. At the end of Session 1, he identified four adherence goals including taking his medications on time, not missing any doses, exercising daily, and reducing stress (i.e., developing and strengthening his coping skills related to stress management).

Bill’s barriers to adherence centered on logistical and attitudinal barriers, as well as independent management of his own HIV. We addressed logistical barriers of getting to appointments, getting medications, maintaining a daily medication schedule, and storing/transporting his medications. Bill’s busy schedule, desire to sleep in, and bad weather in the winter sometimes led to his missed medical appointments. He also noted waiting until the last minute to get his medication refills, which had resulted in him running out of medications on occasion. We discussed strategies to overcome these logisitical barriers. Bill believed that maintaining a structured, visual schedule that was accessible at all times (such as on his mobile phone) would help him stick to his appointments. We also discussed marking on a calendar when he needs to call for his medication refills, buying a transparent pill container so he can see when he is running low, or scheduling one day each month when he always refills his medications.

While Bill took all his medications during the intervention, he reported taking a few doses late because he was out late with friends. Thus, we addressed his attitudinal and environmental barriers to adherence including managing his social life and friends, and dealing with privacy and disclosure. Bill recognized that his social life sometimes got in the way of taking his medications and identified how being out with friends, having friends over and not wanting to interrupt hanging out with them to take his pills, and having hangovers could sometimes impact his adherence. He denied having to hide his medications because he fully disclosed his HIV status to his roommates and close friends. He reported that disclosing his status has been important for his adherence due to the social support he receives. After watching the video Stigma, Bill described going through a period of guilt related to his diagnosis. He noted that these feelings were more salient when he was dating; however, he had not been dating recently. We explored how his value of belonging made social support important to him and how his value of success made improving his adherence a priority as well. He set an additional goal to always take his medications within 30 minutes of his targeted time (i.e., the times he had previously set to take his medications each day). Notably, at the beginning of Session 3, Bill reported that the customized text messages had been helpful in reminding him to take his medications on time, even when with friends. He stated that the texts were instrumental in interrupting his routine and prompted him to take his medication immediately. Bill expressed interest in setting an alarm on his phone with a “cool ringtone” or signing up for a text message reminder service after the intervention has concluded to maintain his adherence.

During the final session, Bill reported having a very stressful week and missed a dose due to being busy with exams. The clinician and Bill explored strategies for managing stressful periods of time including utilizing relaxation techniques and a pillbox to monitor pill taking, so he would not have to rely on his memory about whether he had already taken his pills. Bill revealed his worries about independently managing his HIV when he graduates from college and moves to another state where he is not as familiar with the medical system. He also expressed how “scary” and “intimidating” it would be to find new providers and explore new health care options. While these factors had not yet affected his adherence, he wanted to prepare for the future and its potential impact on adherence. We discussed plans for Bill to start researching health care options in the new state before he moves and reaching out to his current medical team for help. Final action items included exploration of strategies to manage his HIV in a new state, setting a phone alarm reminder, and working on stress-reduction techniques.

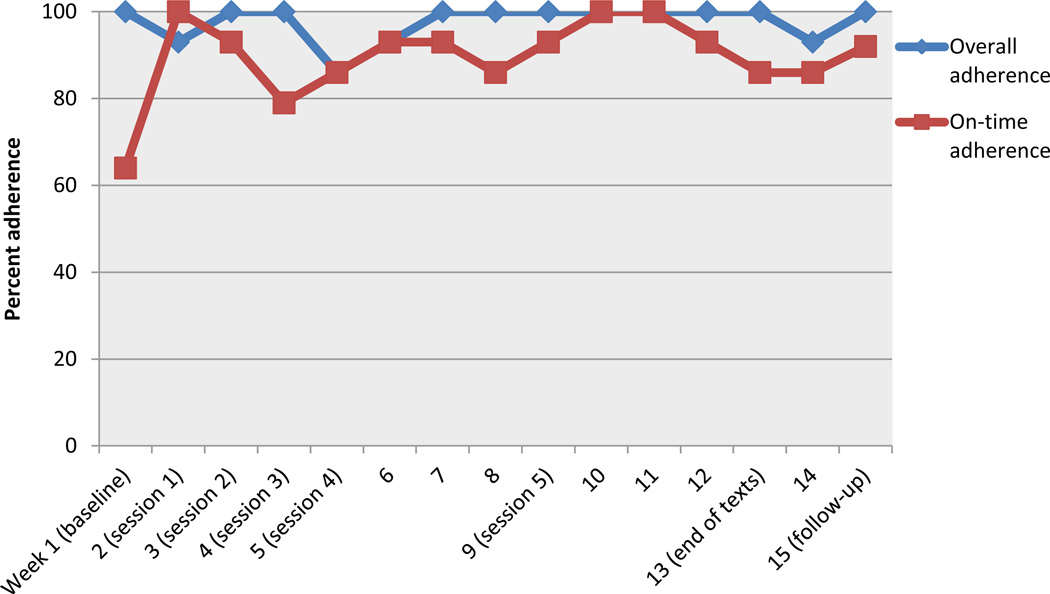

Results

Bill’s MEMS data illustrate his consistency with taking his medications every day (see Figure 3). His primary area of difficulty was on-time adherence. Following initiation of the intervention, Bill’s on-time adherence showed marked improvement and these gains were maintained through follow-up. His self-reported adherence also improved from baseline (score of 5) to follow-up (score of 6). As shown in Table 4, Bill’s change scores on medication readiness were negligible, while his depression and anxiety scores remained in the normal range from baseline to follow-up.

Figure 3.

Graph illustrating the weekly MEMS adherence data from baseline until follow-up for Bill.

Discussion

In this paper, we described Positive STEPS, an adolescent-specific intervention to address patient-centered barriers to HIV medication adherence, using two case illustrations of how the intervention can be implemented with youth who differ by mode of transmission, sexual orientation, race, and gender. Our adaptation of an evidence-based intervention (Life-Steps), which was informed by qualitative interviews with LGB and heterosexual adolescents, is innovative in its use of technology and advances the field by providing a comprehensive tool to address the unique adherence challenges faced by these youth. Previous work typically focused on one aspect of adherence and did not address adherence challenges differently based on gender, sexual orientation, or mode of infection. We specifically adapted our intervention to address adherence issues among sexual minority youth by including information learned from formative qualitative interviews about their unique barriers (e.g., internalized stigma, new HIV infection) and by accounting for how other barriers (e.g., disclosure, social life/friends, side effects) may manifest differently among LGB youth.

The two case examples illustrate several ways for customizing the Positive STEPS intervention. The cases also illustrated different challenges faced by perinatally versus behaviorally infected youth, given prior research showing differing barriers among these groups (MacDonell et al., 2013). Although Sandra (perinatally infected young woman) benefited greatly from the adherence skills she learned during the intervention (as evidenced by her improved adherence during the intervention period), those gains were not maintained after the intervention ended. This is an example of a pattern we see with other perinatally infected adolescents and young adults who are often fatigued by the complexity of their medication regimens and the chronicity of managing HIV their whole lives (Fields et al., under review). Additionally, the effect of neonatal HIV infection, HIV crossing the blood-brain barrier, and long-term usage of antiretrovirals may lead to deficits in neuropsychological functioning or stunted cognitive development (Brouwers et al., 1995; Mitchell, 2001). These effects, coupled with the impact of living with a chronic illness from a young age, might play a role in cognitive maturation resulting in poor planning, problem-solving deficits, and increased dependence on caregivers for support among perinatally infected youth.

Adolescents and emerging adults who are infected with HIV at an older age may have already developed a greater sense of agency in caring for themselves because they did not experience these additional developmental challenges earlier in life. Accordingly, perinatally infected youth may require consistent and frequent check-ins with a provider to ensure that they are staying adherent to their medication regimen. In this intervention, providing booster sessions following the intervention may have been helped Sandra sustain her initial treatment gains. The importance of monitoring mood was also highlighted in this case, which showcased how Sandra was struggling with depression that was simultaneously impacting her adherence. Her improvement in depressive and anxious symptoms at follow-up was likely related to her seeing a therapist at the end of the intervention.

The role of intrinsic motivation in adherence was illustrated in the case of Bill, whose motivation for staying adherent was based on his prior difficulty finding a regimen to which he was not allergic. Targeting and enhancing intrinsic motivation is a key theme in our intervention. Intrinsic motivation is used as an adolescent-focused tool to help reduce reactance. The role of disclosure in promoting adherence is also illustrated in both cases. Sandra’s lack of disclosure prevented her from taking medications in certain settings and got in the way of adherence. Whereas Bill’s full disclosure and sense of agency related to disclosure (i.e., encouraging others to disclose) promoted his continued adherence to his regimen. The role of mode of infection and/or sexual minority status in willingness to disclose HIV diagnosis should be explored in future studies.

There are some limitations to these case studies that should be considered when evaluating the utility of Positive STEPS. Although Positive STEPS did maintain or improve adherence in both patients, treatment gains did not always remain at follow-up. Further pilot testing will be beneficial to determine whether this finding varied by mode of HIV infection or whether longer intervention sessions and/or booster sessions are necessary to maintain treatment gains. In addition, while our intervention was designed to address a range of adherence levels (i.e., from patients who have great adherence and only need maintenance of their adherence patterns to patients who have very poor adherence), larger-scale evaluation of the utility of this intervention across varying levels of adherence is warranted. While the main purpose of this paper is to illustrate feasibility, acceptability, and utility, the promising impact on adherence even in this small sample shows promise for future application. A large, randomized clinical trial of Positive STEPS is necessary in order to determine efficacy, with further effectiveness testing to assess generalizability across a variety of patient populations.

We learned several lessons in our development of the Positive STEPS intervention. First, consistency around adherence improvement might be necessary. As illustrated in the case of Sandra, removal of support after it had been integrated into her routine could have had a negative or rebound effect on her adherence. Second, we learned that more sessions and/or booster sessions may be beneficial to help ensure that treatment gains are maintained over time. Third, given that perintally infected youth have been struggling with HIV all their lives, ongoing support around adherence, adolescent identity development, and transition to adult care are important to continually emphasize.

Positive STEPS, which was adapted from an evidence-based intervention for adults (Safren et al., 1999, 2001), provides a multifaceted intervention model that can be easily customized for use in clinical settings within a multidisciplinary team. While we acknowledge that MEMS is not practical in many settings, clinicians who wish to implement this intervention in practice should develop alternate methods for monitoring weekly adherence, such as use of online mobile applications or self-report (Wagner, 2002). Positive STEPS provides an avenue to have conversations about adherence-related barriers and provide individual support for perinatally and behaviorally infected adolescents and young adults. Additional research is needed to test the effectiveness of Positive STEPS in an RCT.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

HIV medication adherence intervention for lesbian, gay, bisexual and heterosexual 13- to 24-year-olds

Five sessions address adherence barriers using problem solving, short message service (SMS), and video vignettes

Intervention implementation with perinatally and behaviorally infected cases shown

Monitored adherence improved for both cases during the intervention

Adherence gains were not sustained for the perinatally infected young adult

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Harvard University Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) grant P30 AI060354 (PI: Mimiaga and Bogart) and The National Institute of Mental Health R34MH090790-S1 (PI: Bogart). We would like to thank Dr. Steve Safren, Jessica Ratner, Caroline Hu, and Michael Garber for their contributions to the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Patient details have been modified to protect their identities.

Contributor Information

Idia B. Thurston, University of Memphis

Laura M. Bogart, Boston Children's Hospital/Harvard Medical School

Madeline Wachman, Boston University.

Elizabeth F. Closson, The Fenway Institute, Fenway Health

Margie R. Skeer, Tufts University School of Medicine

Matthew J. Mimiaga, The Fenway Institute, Fenway Health, Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Harvard School of Public Health

References

- Amico KR, Harman JJ, Johnson BT. Efficacy of antiretroviral therapy adherence interventions: A research synthesis of trials, 1996 to 2004. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;41(3):285–297. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000197870.99196.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55(5):469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balfour L, Tasca GA, Kowal J, Corace K, Cooper CL, Angel JB, Cameron DW. Development and validation of the HIV Medication Readiness Scale. Assessment. 2007;14(4):408–416. doi: 10.1177/1073191107304295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangsberg DR. Less than 95% adherence to nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor therapy can lead to viral suppression. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2006;43(7):939–941. doi: 10.1086/507526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangsberg DR, Hecht FM, Charlebois ED, Zolopa AR, Holodniy M, Sheiner L, Moss A. Adherence to protease inhibitors, HIV-1 viral load, and development of drug resistance in an indigent population. AIDS. 2000;14(4):357–366. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200003100-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KM, Wilson IB, Li X, Arnsten JH. Comparison of antiretroviral adherence questions. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(2):461–468. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9864-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrien VM, Salazar JC, Reynolds E, McKay K. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected pediatric patients improves with home-based intensive nursing intervention. AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 2004;18(6):355–363. doi: 10.1089/1087291041444078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwers P, Tudor-Williams G, DeCarli C, Moss HA, Wolters PL, Civitello LA, Pizzo PA. Relation between stage of disease and neurobehavioral measures in children with symptomatic HIV disease. AIDS. 1995;9(7):713–720. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199507000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AC, Chapman JE, Forman EM, Beck AT. The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26(1):17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2012. No. 3, part A. Vol. 17. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2012a. [Retrieved November 28, 2012]. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and six U.S. dependent areas—2010. from www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: HIV infection, testing, and risk behaviors among youths—United States, 2012. [Retrieved November 28, 2012];Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2012b 61 from www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/wk/mm61e1127.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLaMora P, Aledort N, Stavola J. Caring for adolescents with HIV. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2006;3(2):74–78. doi: 10.1007/s11904-006-0021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowshen N, Kuhns LM, Johnson A, Holoyda BJ, Garofalo R. Improving adherence to antiretroviral therapy for youth living with HIV/AIDS: A pilot study using personalized, interactive, daily text message reminders. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2012;14(2):e51. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Zurilla TJ. Problem-solving therapy: A social competence approach to clinical intervention. New York, NY: Springer; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Fields EL, Bogart LM, Thurston IB, Hu C, Closson EF, Skeer MR, Mimiaga MJ. Qualitative comparison of barriers to antiretroviral medication adherence among perinatally and behaviorally HIV-infected youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. doi: 10.1177/1049732317697674. (under review). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finocchario-Kessler S, Catley D, Thomson D, Bradley-Ewing A, Berkley-Patton J, Goggin K. Patient communication tools to enhance ART adherence counseling in low and high resource settings. Patient Education and Counseling. 2012;89(1):163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvie PA, Lensing S, Rai SN. Efficacy of a pill-swallowing training intervention to improve antiretroviral medication adherence in pediatric patients with HIV/AIDS. Pediatrics. 2007;119(4):e893–e899. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaur AH, Belzer M, Britto P, Garvie PA, Hu C, Graham B, Flynn PM. Directly observed therapy (DOT) for nonadherent HIV-infected youth: Lessons learned, challenges ahead. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2010;26(9):947–953. doi: 10.1089/aid.2010.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KW, Rabkin JG. Psychological distress in people with HIV/AIDS: Prevalence rates and methodological issues. AIDS and Behavior. 1997;1(1):29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kapogiannis BG, Soe MM, Nesheim SR, Abrams EJ, Carter RJ, Farley J, Bulterys M. Mortality trends in the US Perinatal AIDS Collaborative Transmission Study (1986–2004) Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2011;53(10):1024–1034. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon ME, Trexler C, Akpan-Townsend C, Pao M, Selden K, Fletcher J, D'Angelo LJ. A family group approach to increasing adherence to therapy in HIV-infected youths: Results of a pilot project. AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 2003;17(6):299–308. doi: 10.1089/108729103322108175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonell K, Naar-King S, Huszti H, Belzer M. Barriers to medication adherence in behaviorally and perinatally infected youth living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(1):86–93. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0364-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney RE, Jr, Rodman J, Hu C, Britto P, Hughes M, Smith ME, Rathore M. Long-term safety and efficacy of a once-daily regimen of emtricitabine, didanosine, and efavirenz in HIV-infected, therapy-naive children and adolescents: Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol P1021. Pediatrics. 2007;120(2):e416–e423. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell W. Neurological and developmental effects of HIV and AIDS in children and adolescents. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 2001;7(3):211–216. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naar-King S, Suarez M. Motivational interviewing with adolescents and young adults. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nezu AM, Perri MG. Social problem-solving therapy for unipolar depression: An initial dismantling investigation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57(3):408–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. pp. 1–161. [Google Scholar]

- Patel K, Hernan MA, Williams PL, Seeger JD, McIntosh K, Van Dyke RB, Seage GR., 3rd Long-term effectiveness of highly active antiretroviral therapy on the survival of children and adolescents with HIV infection: A 10-year follow-up study. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2008;46(4):507–515. doi: 10.1086/526524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, Skeer M, Perkovich B, Johnson CV, Safren SA. A review of HIV antiretroviral adherence and intervention studies among HIV-infected youth. Topics in HIV Medicine. 2009;17(1):14–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers AS, Miller S, Murphy DA, Tanney M, Fortune T. The TREAT (Therapeutic Regimens Enhancing Adherence in Teens) program: Theory and preliminary results. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;29(Suppl. 3):30–38. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00289-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Otto MW, Worth JL. Life-Steps: Applying cognitive behavioral therapy to HIV medication adherence. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 1999;6(4):332–341. [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Otto MW, Worth JL, Salomon E, Johnson W, Mayer K, Boswell S. Two strategies to increase adherence to HIV antiretroviral medication: Life-Steps and medication monitoring. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2001;39(10):1151–1162. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shegog R, Markham CM, Leonard AD, Bui TC, Paul ME. "+CLICK": Pilot of a web-based training program to enhance ART adherence among HIV-positive youth. AIDS Care. 2012;24(3):310–318. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.608788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuter J, Sarlo JA, Kanmaz TJ, Rode RA, Zingman BS. HIV-infected patients receiving lopinavir/ritonavir-based antiretroviral therapy achieve high rates of virologic suppression despite adherence rates less than 95% Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2007;45(1):4–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318050d8c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Frick PA, Pantalone DW, Turner BJ. Antiretroviral adherence interventions: A review of current literature and ongoing studies. Topics in HIV Medicine. 2003;11(6):185–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner GJ. Predictors of antiretroviral adherence as measured by self-report, electronic monitoring, and medication diaries. AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 2002;16(12):599–608. doi: 10.1089/108729102761882134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics: Journal of Consultation Liaison Psychiatry. 1971;12(6):371–379. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(71)71479-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.