Abstract

Objectives:

A better understanding of the subnational variations could be paramount to the efficiency and effectiveness of the response to the HIV epidemic. The purpose of this study is to describe the methodology used to produce the first estimates at second subnational level released by UNAIDS.

Methods:

We selected national population-based surveys with HIV testing and survey clusters geolocation, conducted in 2008 or later. A kernel density estimation approach (prevR) with adaptive bandwidths was used to generate a surface of HIV prevalence. This surface was combined with LandScan global population distribution grid to estimate the spatial distribution of people living with HIV (PLWHIV). Finally, results were adjusted to national UNAIDS's published estimates and merged per second subnational administrative unit. An indicator of the quality of the estimates was computed for each administrative unit.

Results:

These estimates combine two complementary approaches: the prevR method, focusing on spatial variations of HIV prevalence, as well as national estimates published by UNAIDS, taking into account trends of HIV prevalence over time. Seventeen country reports have been produced. However, quality of the estimates at second subnational level is highly heterogonous between countries, depending on the number of units and the survey sampling size. In some countries, estimates at second subnational level are very uncertain and should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion:

These estimates at second subnational level constitute a first step to help countries to better understand their HIV epidemic and to inform programming at lower geographical levels. Further developments are needed to better match local needs.

Keywords: epidemiologic methods, HIV seroprevalence, spatial interpolation

Background

Major decisions in HIV programme planning and the evaluation of the impact of such programmes rely on the understanding of the epidemiology of HIV in a particular country. However, it is increasingly clear that substantial heterogeneity exists within the same country as far as the extent of the HIV epidemic is concerned [1,2]. Existing surveillance, estimation and modelling are overwhelmingly focused on a national level. However, a better understanding of the subnational variations could be paramount to the efficiency and effectiveness of the response to the HIV epidemic. Consequently, national programme makers and epidemiologists, as well as international funders tend to want to increase the use of tools to measure, visualize and analyse these inner-country epidemiological patterns.

In response to these developments, UNAIDS called a meeting in July 2013 [3] to bring together relevant stakeholders to review the field and identify ways in which all could move forward. Generating subnational-level HIV estimates, in particular at a second subnational level, would be useful to address the urgent need for countries to be able to describe their epidemic at a subnational level and inform programme making. Subnational estimates better reflect differences inside the HIV epidemic within a country.

Following that convening, UNAIDS commissioned a task force to forward this agenda. The HIV Modelling Consortium was therefore asked to address these technical challenges (http://www.hivmodelling.org/projects/methods-sub-national-estimates-hiv-prevalence). A technical meeting was held in Nairobi, 24–25 March 2014 for modelling groups, UNAIDS representatives, the Health Policy Project and members from national programme teams to discuss the use for subnational estimates of HIV epidemiology and review seven suggested methods to produce subnational estimates from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHSs) and/or antenatal clinics data. The methods performance in predicting the pattern of prevalence in a number of countries (Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania and Uganda) was assessed using both internal (leave-one-out cross validation and partitioned data hold-back) and external validation approaches. Results of the validation exercise will be published on HIV Modelling Group website; comparison with data from the previous available survey.

In the medium term, it was recommended to develop a complex Bayesian model allowing estimates, as well as measures of the inherent uncertainty, to be inferred from the data. The urgent need for countries to understand subnational variations in HIV epidemiology was noted. In the short term, it was suggested to use the prevR [4] approach to generate subnational estimates for time-limited use by countries. Results gained from the prevR approach were similar and close enough to more complex approaches to allow its use as a short-term strategy to generate HIV estimates at the second subnational level.

The purpose of this study is to describe the methodology used to produce the first estimates at second subnational level released by UNAIDS.

Materials and method

DHSs and similar surveys are a major survey programme carried out in over 90 low and middle-income countries around the world (http://www.dhsprogram.com/). Each survey uses a similar stratified two-stage sample design, in order to be representative both on a national and a regional level. Some surveys also use GPS to collect geographical coordinates for each survey cluster. Since HIV screening modules have been introduced in the first decade after 2000, these coordinates are randomly offset by up to two kilometres in urban areas and five kilometres in rural areas, with 1% of rural areas displaced up to 10 km, in order to ensure the anonymity of the respondents [5]. The displacement is restricted so that the coordinates stay within the country and within the DHS survey region. In surveys released since 2009, the displacement is also restricted to the country's second administrative level where possible.

We selected all surveys whose data are available on http://www.dhsprogram.com, with HIV testing and survey clusters geolocation, conducted in 2008 or later (they were all released in 2009 or later). For countries with two or more selected surveys, we only kept the most recent one (see Table 1). Survey clusters with missing geolocation, individuals with an indeterminate result or not aged 15–49 years were excluded.

Table 1.

Selected surveys, sample size, administrative units types, parameter for the estimates and proportion of units with good or moderately good estimates for 17 countries.

| Country name | Survey type | Survey year | DHS regions | Clusters excludeda | Clusters selected | Tested 15–49 individualsb | Type of units selected | Number of units | Mean number of observations per unit | N parameterc | % of units with good/moderately good estimates |

| Burkina Faso | DHS MICS | 2010 | 13 | 32 | 541 | 14 065 | Province | 44 | 319.7 | 500 | 50% |

| Burundi | DHS | 2010 | 5 | 0 | 376 | 8326 | Province | 17 | 489.8 | 500 | 100% |

| Côte d’Ivoire | DHS MICS | 2011–2012 | 11 | 12 | 339 | 8817 | Department | 50 | 176.3 | 403 | 30% |

| Cameroon | DHS MICS | 2011 | 12 | 1 | 577 | 13 905 | Department | 58 | 239.7 | 484 | 35% |

| Ethiopia | DHS | 2011 | 11 | 25 | 571 | 27 409 | Zone | 66 | 415.3 | 500 | 59% |

| Gabon | DHS | 2012 | 10 | 4 | 332 | 10 487 | Department | 48 | 218.5 | 421 | 35% |

| Guinea | DHS MICS | 2012 | 5 | 0 | 300 | 8041 | Prefecture | 34 | 236.5 | 500 | 32% |

| Haiti | EMMUS | 2012 | 11 | 8 | 437 | 17 424 | Arrondissement | 41 | 425.0 | 500 | 59% |

| Lesotho | DHS | 2009 | 10 | 5 | 395 | 6711 | District | 10 | 671.1 | 138 | 100% |

| Mozambique | INSIDA | 2009 | 11 | 0 | 270 | 9268 | District | 128 | 72.4 | 241 | 14% |

| Malawi | DHS | 2010 | 27 | 24 | 825 | 13 738 | District | 27 | 508.8 | 329 | 100% |

| Rwanda | DHS | 2010–2011 | 5 | 0 | 492 | 12877 | District | 30 | 429.2 | 500 | 100% |

| Senegal | DHS MICS | 2010–2011 | 14 | 7 | 384 | 9693 | Department | 30 | 323.1 | 500 | 67% |

| Sierra Leone | DHS | 2008 | 4 | 3 | 350 | 6349 | District | 14 | 453.5 | 500 | 93% |

| Tanzania | HMIS | 2011–2012 | 9 | 13 | 570 | 17 988 | District | 132 | 136.3 | 500 | 15% |

| Uganda | AIS | 2011 | 10 | 0 | 470 | 19 568 | District | 111 | 176.3 | 453 | 21% |

| Zimbabwe | DHS | 2010–2011 | 10 | 15 | 391 | 13 487 | District | 60 | 224.8 | 264 | 78% |

AIS, AIDS Indicators Survey; DHS, Demographic and Health Survey; EMMUS, Enquête Mortalité, Morbidité et Utilisation des Services; HMIS, HIV/AIDS and Malaria Indicator Survey; INSIDA, National Survey on Prevalence, Behavioral Risks and Information about HIV and AIDS; MICS, Multiple Indicators Cluster Survey.

aGeolocation is missing or no valid observation in that cluster.

bInvalid/indeterminate results and individuals residing in a cluster with no geolocation excluded.

cFor bandwidth computation (prevR).

Various researchers used kernel estimators for spatial epidemiology [6], such as the estimation of a surface of relative risks [7–9]. A surface of prevalence is the ratio between two intensity surfaces (number of cases per surface unit), while a surface of relative risks corresponds to the ratio between the density surface (whose integral has been reduced to one) of positive cases and the density surface of control cases (population exposed to the risk). With fixed bandwidths, some researchers [7,9] suggest using the same constant to estimate both density surfaces (positive cases and control cases). However, the research [7,8,10] suggests that the use of adaptive bandwidths is more relevant to health-related matters in order to get a closer match of the spatial distribution of the population and thus reduce the smoothing of information.

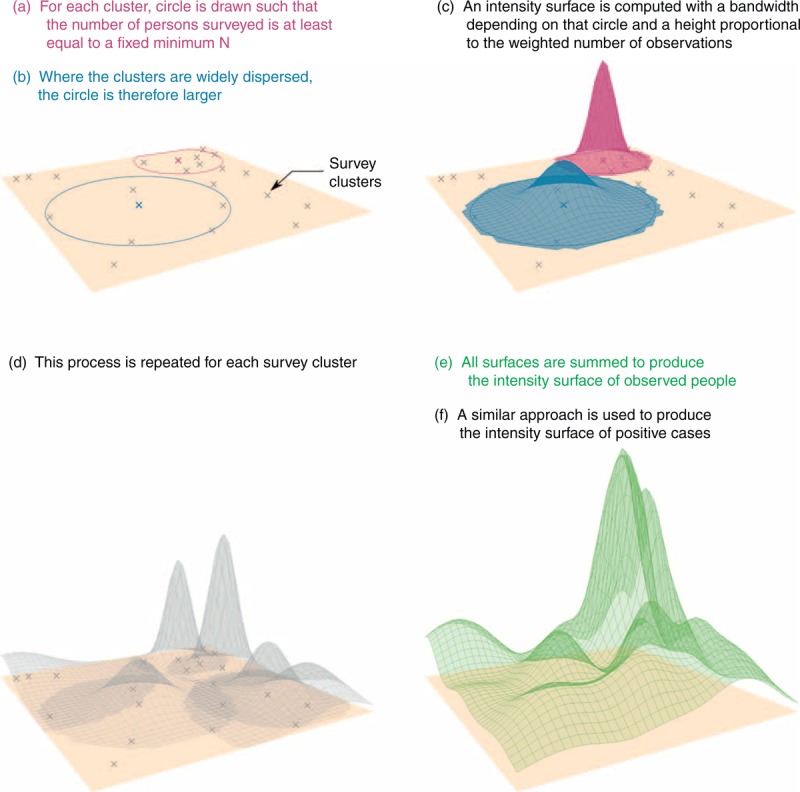

The prevR approach was explained in details elsewhere [4] and implemented in a package for the statistical software R [11]. It is a kernel density estimation using adaptive bandwidths based on a minimal number of observations (N parameter). Figure 1 summarizes the prevR approach. For each cluster, a circle is drawn such that the number of persons surveyed within it is at least equal to a fixed minimum (N parameter). A surface is computed using a Gaussian kernel with a bandwidth depending on that circle and a height proportional to the weighted number of tested individuals in that cluster, that is the sum of the individual sampling weights. These sampling weights are provided in DHSs datasets and are adjustment factors to adjust for differences in probability of selection [12]. All clusters are summed to compute the intensity surface of observed individuals. The same approach is used to compute the intensity surface of HIV-positive individuals. The prevalence surface is the ratio of the intensity surface of the number who tested positive to the surface of the total number tested.

Fig. 1.

prevR approach to compute intensity surfaces of observed people and positive cases.

This method is an adaptation from the nearest neighbour technique (described by Silverman [13] and Altman [14] among others, and tested by Bithell [7]) to the difficulty of computing the ratio of two intensity surfaces. The use of adaptive bandwidths of equal number of persons surveyed makes it possible to achieve a smoothing effect that adapts to the high irregularity of spatial distribution among the survey clusters, selecting the clusters according to the observed population distribution. The surfaces thus generated are more accurate for densely populated areas (as more observations are available) and strongly smoothed in sparsely surveyed areas.

The main difficulty in applying this method to real data comes from determining the right value to use for parameter N. In previous publications [4,15], we attempted to model the optimal value of N (denoted No) as a function of the observed national prevalence (p), the number of persons tested (n) and the number of survey clusters (c). To that end, we simulated 22 000 DHSs with various values for the three parameters and calculated the optimal value of N for each simulation. Modelling the results gained by regression generates the following formula: No = 14 172· n0.419 · p−0.361 · c0.037 − 91.011. Although this result was determined from simulations of a fictitious country and cannot strictly be generalized to other situations, it does provide a value for the parameter that is efficient in practice, providing a balance between a smoothing effect high enough to compensate random variations due to the sampling but not too strong in order to keep local information. For countries with a very low prevalence, this parameter could increase substantially. We therefore decided, for pragmatic reasons, to limit the value of N to a maximum of 500 (see Table 1).

At an approximately 1-km resolution (30” × 30”), Oak Ridge National Laboratory's LandScan is the finest resolution global population distribution data available that represent an ambient population (average over 24 h) [16]. LandScan data were rescaled to national DemProj estimates to produce a surface of the 15–49 year-olds population (pop15–49) and a surface of 50 and more year-old population (pop50+). DemProj is the demographic projection module from the Spectrum/Estimation and Projection Package (EPP) software used by UNAIDS to estimate prevalence and incidence trends [17] at a national level.

Using prevR and DHS's sampling weights, we produced a surface of unadjusted HIV prevalence of 15–49 year-olds (prevun.15–49) at the same resolution than the LandScan grid. An unadjusted surface of 15–49 year-old people living with HIV (PLWHIV) is obtained as prevun.15–49 × pop15–49. This surface is then proportionally rescaled to make the total number of 15–49 PLWHIV equal to the national estimates obtained with Spectrum/EPP, generating an adjusted surface of 15–49 PLWHIV (plwhiva.15–49). The same approach was used to calculate an adjusted 50+ PLWHIV surface, considering that the spatial distribution of 50+ PLWHIV was similar to the spatial distribution of 15–49 PLWHIV. Finally, the adjusted 15–49 HIV prevalence surface is equal to plwhiva.15–49/pop15–49.

UNAIDS estimates are mid-year estimates. For countries with a DHS conducted during a single year, the estimates are adjusted to the same year. For countries with DHS conducted between 2 years, estimates are adjusted to UNAIDS estimates for the second year of the survey.

GADM is a spatial database of the location of administrative areas or administrative boundaries worldwide [18]. Administrative division is country-specific. In Table 1, we featured the type of administrative units retained for each country. Boundaries were obtained from GADM, except for Rwanda (boundaries were provided by the National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda [19]), Gabon (Ministry of Health of Gabon/Department of Cartography) and Uganda (Global Administrative Unit Layers was used [20]). For each administrative unit, pixels of the surfaces were added to find out the total population and the number of PLWHIV per unit, then to calculate the HIV prevalence of the unit.

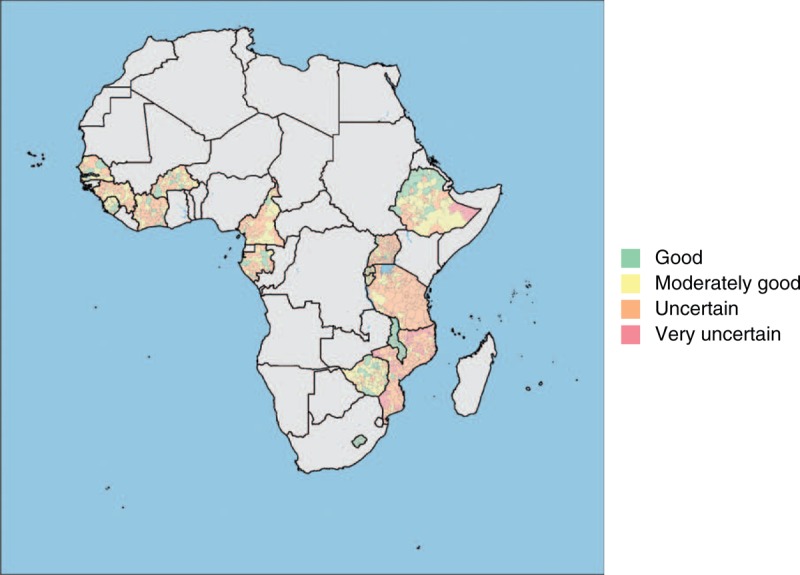

An indicator of the quality of the estimates was created for each unit, based on the number of survey observations located within the unit (nobs) and the N parameter used to estimate the prevalence surface, as follows: ‘good’ if nobs is at least N (estimates are based on observations from the same unit); ‘moderately good’ if N/2 ≤ nobs < N (estimates are mainly based on observations from the same unit); ‘uncertain’ if 0 < nobs < N/2 (estimates are mainly based on observations from neighbouring units); and ‘very uncertain’ if nobs = 0 (estimates are based only on observations from neighbouring units).

All analyses were performed with R 3.1.0 [21] and the following packages in alphabetical order: foreign, GenKern, ggplot2, maptools, prevR and raster.

Results

Table 1 presents the surveys, their sample size, the type of administrative units, the N parameter for the estimates and the proportion of units with good or moderately good estimates for the 17 selected countries.

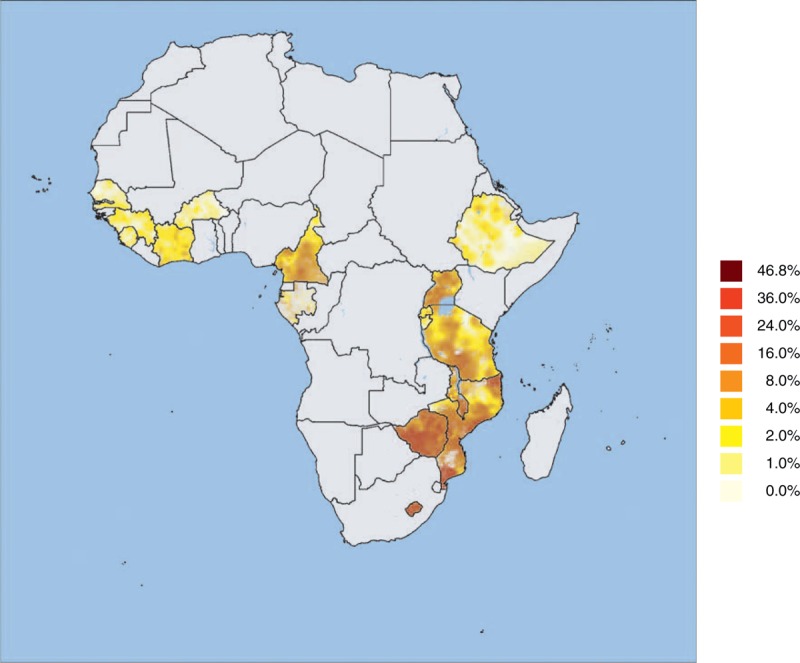

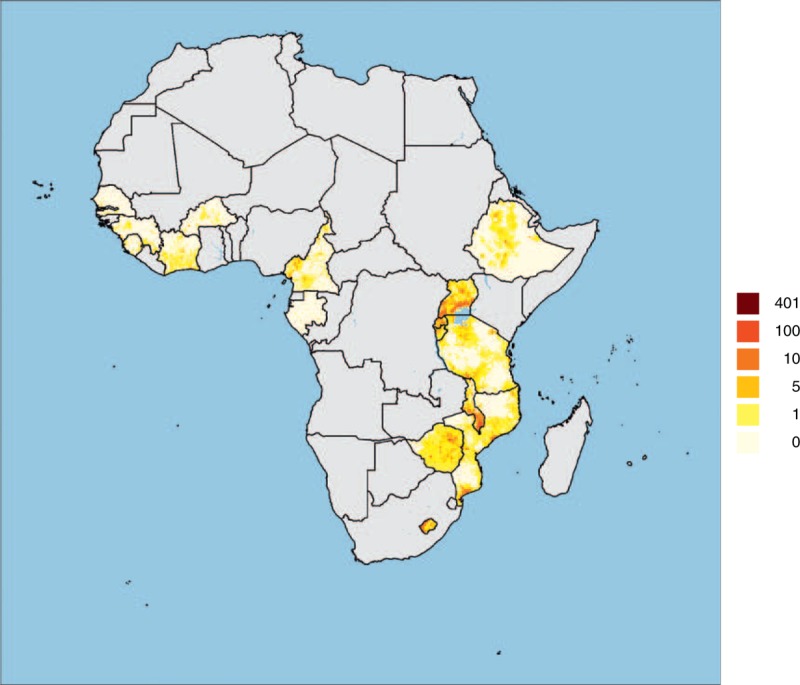

Figures 2 and 3 present the HIV prevalence surface (15–49 year-olds) and the PLWHIV intensity surface (expressed in number of PLWHIV per km2, 15-year-olds and over), respectively, for the 16 sub-Saharan selected countries (results for Haiti not presented). Quality of estimates per administrative unit is presented on Fig. 4.

Fig. 2.

HIV prevalence (in %, 15–49 year-olds) surface for the 16 selected sub-Saharan countries.

Surfaces were generated independently for each country. Surveys used were conducted between 2008 and 2012.

Fig. 3.

People living with HIV density surface (in PLWHIV/km2, 15+ year-olds) for the 16 selected sub-Saharan countries.

Surfaces were generated independently for each country. Surveys used were conducted between 2008 and 2012.

Fig. 4.

Quality of estimates per administrative unit for the 16 selected sub-Saharan countries.

Administrative units are provinces for Burkina Faso and Burundi; departments for Côte d’Ivoire, Cameroon, Gabon and Senegal; zones for Ethiopia; prefectures for Guinea; districts for Lesotho, Mozambique, Malawi, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe.

Results per administrative unit were released on the website of the UNAIDS Reference Group on HIV Estimates, Modelling and Projections in 2014 through specific country reports (http://www.epidem.org/).

Figures 2 and 3 show that, although national estimates were calculated separately for each country and at different years, when country estimates and maps across sub-Saharan Africa are brought together, HIV estimates in border areas are consistent across country borders. However, there is a high heterogeneity in the quality of the estimates per second-level administrative units (see Table 1 and Fig. 4), due to high heterogeneity in the number of second-level administrative units per country (from 14 districts in Sierra Leone to 132 districts in Tanzania) and high heterogeneity in surveys’ sampling size (from 6439 tested individuals in Sierra Leone 2008 DHS to 27 409 in Ethiopia 2011 DHS), resulting in important variations of the mean number of observations per unit (from 72.4 in Mozambique to 671.1 for Lesotho), the main determinant (with the N parameter) of the proportion of administrative units with good or moderately good estimates (from 14% in Mozambique to 100% in Burundi, Lesotho, Malawi and Rwanda).

HIV prevalence (Fig. 2) and PLWHIV density (Fig. 3) provide two complementary pictures of the epidemics. Areas with higher relative HIV prevalence (expressed in percentage) are not necessarily the ones with the higher absolute number of people living with HIV, as spatial distribution of human population is highly irregular. Due to population density, HIV epidemics are often concentrated in main cities and along main roads. Our results show that, within a same country, rural areas are also heterogeneous with disparities between regions.

Discussion

The main underlying assumptions of this approach are that the age structure was uniform across all countries (i.e. the spatial distribution of individuals from 15 to 49 and 50+ was identical to the spatial distribution of the overall population, as estimated by LandScan); close geographic areas tend to have similar HIV prevalence (i.e. HIV prevalence could be estimates using spatial interpolation and smoothing techniques); and spatial distribution of 50+ PLWHIV was equivalent to the estimated spatial distribution of 15–49 PLWHIV.

Because fertility is usually lower in urban areas, the proportion of the total population aged 15–49 years should be higher in the cities. Therefore, urban areas are probably slightly underrepresented in our final estimates.

DHSs and similar surveys are designed to be statistically representative at national and regional level (the number of DHS regions is featured in Table 1) but not at a lower geographic level. Therefore, all second-level administrative units are not systemically covered enough by the survey. Table 1 shows that the proportion of administrative units with good or moderately good estimates is highly correlated with the mean number of valid observations (tested individuals with a positive or a negative result, i.e. indeterminate results excluded, and residing in a survey cluster with geolocation, i.e. cluster with missing location excluded) per administrative unit. The quality of estimates (Fig. 3) depends on the total sampling size of the selected survey, the total number of administrative units and the distribution of the survey clusters across the administrative division. Therefore, in countries with a high number of second-level administrative units (e.g. Mozambique or Tanzania), few units, usually the most populated ones, have good or moderately good estimates.

In all cases, estimates for units with uncertain or very uncertain estimates should be interpreted with caution. The prevR approach allows the reproducing of the regional component of spatial variation, and the estimated prevalence surfaces could be considered as regional trend surfaces. A surface of this sort, by construction, is necessarily spatially continuous and self-correlated and does not at all imply any potential discontinuities and local variations in the real surface of the epidemic, which remains inaccessible in the DHS data.

In some countries, the proportion of units with uncertain or very uncertain estimates is very high (up to 86% in Mozambique). It indicates that the current available data are not precise enough to produce good estimates at that level. Most DHSs have been designed to be representative at first administrative level but not at second administrative level. The accuracy of the estimates could be improved by computing them at a lower resolution (i.e. at first administrative level or at an intermediate grouping of second level units, if available) and/or by increasing the sampling size of the next population-based survey, both approaches increasing the number of observations per administrative unit, respectively, by reducing the number of units or by increasing the total number of observations. As increasing the sampling size of a survey is costly, countries should evaluate their specific needs in terms of programming and design the next national survey accordingly. Statistically, the best approach would be to design the survey to be representative at the desired geographic level, as such approach would allow to compute directly HIV prevalence for each administrative unit.

These estimates do not take into account the different modes of transmission and the relative contribution of key populations at a higher risk (including sex workers, men having sex with other men, drug users) in local epidemics. In addition to the indications provided by these estimates, policy programmers should also consider their own knowledge of the epidemic and other available data to define health policy and to explain disparities observed within a specific country. In particular, estimates could also be linked to programme data to evaluate how current programmes are distributed in relation to populations needing services.

These estimates combine two complementary approaches: the prevR method, focusing on spatial subnational variations of HIV prevalence and taking into account the spatial distribution of the survey observations but based only on a unique population-based survey, as well as national UNAIDS published estimates, taking into account trends of HIV prevalence over time, using both national population-based surveys and antenatal clinics data, but computed only at a national or regional level (according to the country).

The adjustment to UNAIDS estimates was due to two main reasons: technically, it improves the estimates by taking into account the additional information obtained from EPP/Spectrum; pragmatically, it produces a coherent set of estimates between the several approaches used by UNAIDS.

Population estimates from Spectrum/EPP are based on the United Nations Population Division World Population Prospects 2012. There may be some difference between United Nations Population Division estimates and those obtained through Spectrum. United Nations Population Division estimates are input into Spectrum and are then adjusted within Spectrum by removing the estimated population living with HIV, which is then added back through the estimation process. This process is limited to the 39 high burden countries.

Similarly, prevalence estimates differ slightly between UNAIDS estimates and DHSs, due to the fact that UNAIDS estimates take into account additional sources (in particular surveillance among pregnant women attending antenatal clinics) [22]. In our estimates at the second subnational level, UNAIDS estimates define the national HIV burden while DHSs determine the spatial distribution of HIV prevalence.

These HIV estimates at the second subnational level constitute a first step to help countries to better understand their HIV epidemic and to inform programming at lower geographical levels. However, data collection and methods to produce subnational estimates need to be improved in the future to better match local needs.

Acknowledgements

The prevR package was developed with financial support of ANRS (Agence Nationale de Recherche sur le Sida et les hépatites virales) and IRD (Institut de Recherche pour le Développement). This work received financial support from UNAIDS.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Tanser F, Bärnighausen T, Cooke GS, Newell M-L. Localized spatial clustering of HIV infections in a widely disseminated rural South African epidemic. Int J Epidemiol 2009; 38:1008–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aral SO, Padian NS, Holmes KK. Advances in multilevel approaches to understanding the epidemiology and prevention of sexually transmitted infections and HIV: an overview. J Infect Dis 2005; 191:S1–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNAIDS Reference Group on Estimates, Modeling and Projections. Identifying populations at greatest risk of infection – geographic hotspots and key populations. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larmarange J, Vallo R, Yaro S, Msellati P, Méda N. Methods for mapping regional trends of HIV prevalence from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS). Cybergeo Europ J Geo 2011; 558: http://cybergeo.revues.org/24606http://cybergeo.revues.org/24606; doi: 10.4000/cybergeo.24606. [Google Scholar]

- 5.The DHS Program. Methodology – collecting geographic data. 2014. http://www.dhsprogram.com/What-We-Do/GPS-Data-Collection.cfm [Accessed 2 June 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gatrell AC, Bailey TC, Diggle PJ, Rowlingson BS. Spatial point pattern analysis and its application in geographical epidemiology. Trans Inst Br Geogr 1996; 21:256–274. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bithell JF. An application of density estimation to geographical epidemiology. Stat Med 1990; 9:691–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies TM, Hazelton ML. Adaptive kernel estimation of spatial relative risk. Stat Med 2010; 29:2423–2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelsall JE, Diggle PJ. Kernel estimation of relative risk. Bernoulli 1995; 1:3–16. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlos HA, Shi X, Sargent J, Tanski S, Berke EM. Density estimation and adaptive bandwidths: a primer for public health practitioners. Int J Health Geogr 2010; 9:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larmarange J. prevR: estimating regional trends of a prevalence from a DHS. Paris: IRD; 2013. http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/prevR/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rutstein SO, Rojas G. Guide to DHS statistics. Calverton, MD: ORC Macro; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silverman B. Density estimation for statistics and data analysis. London: Chapman and Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Altman NS. An introduction to Kernel and nearest-neighbor nonparametric regression. Am Stat 1992; 46:175–185. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larmarange J. HIV prevalence in Africa: validity of a measurement. 2007. http://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00320283/fr/ [Accessed 3 June 2014] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bright EA, Rose AN, Urban ML. LandScan 2012. 2013. http://www.ornl.gov/landscan/ [Accessed 3 June 2014] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stover J, Brown T, Marston M. Updates to the Spectrum/Estimation and Projection Package (EPP) model to estimate HIV trends for adults and children. Sex Transm Infect 2012; 88:i11–i16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.GADM. Global administrative areas, boundaries without limits, version 2.0. 2012. http://www.gadm.org/ [Accessed 3 June 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Institute of Statistics Rwanda. Geodata; 2014. http://www.statistics.gov.rw/geodata [Accessed 7 July 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 20.FAO GeoNetwork. Global Administrative Unit Layers (GAUL). 2014. http://www.fao.org/geonetwork/srv/en/metadata.show?id=12691 [Accessed 7 July 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 21.R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013. http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strategic Information and Monitoring Division. Methodology – understanding the HIV estimates. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2013. [Google Scholar]