Abstract

Background:

Paediatric treatment continues to lag behind adult treatment and significant efforts are urgently needed to scale up antiretroviral therapy (ART) for children. As efforts to prevent mother-to-child transmission expand, better understanding of future trends and age characterization of the population that will be in need of ART is needed to inform policymakers, as well as drug developers and manufacturers.

Methods:

The Spectrum model was used to estimate the total number of expected paediatric infections by 2020 in 21 priority countries in Africa. Different ART scale-up scenarios were investigated and age characterization of the population was explored.

Results:

By 2020, new paediatric infections in the 21 countries will decline in all the scenarios. Total paediatric infections will also decline in the 21 high-burden countries, but with a differential effect by scenario and age group. On the basis of the optimal scale-up scenario, 1 940 000 [1 760 000–2 120 000] children will be expected to be living with HIV in 2020. The number of children dying of AIDS is notably different in the three models. Assuming optimal scale-up and based on 2013 treatment initiation criteria, the estimates of children to receive ART in the 21 high-burden countries will increase to 1 670 000 (1 500 000–1 800 000).

Conclusion:

By 2020, even under the most optimistic scenarios, a considerable number of children will still be living with HIV. Age-appropriate drugs and formulations will be needed to meet the treatment needs of this vulnerable population. Improved estimates will be critical to guide the development and forecasting of commodities to close the existing paediatric treatment gap.

Keywords: antiretroviral therapy, children, paediatric estimates, paediatric forecasting, paediatric HIV

Background

Many countries are rapidly scaling up efforts to eliminate mother-to-child transmission of HIV (EMTCT) [1]. Under the Global Plan Towards the Elimination of New HIV Infections among Children by 2015 and Keeping their Mothers Alive (Global Plan) [2], the 21 priority countries in sub-Saharan Africa have reported significant gains in antiretroviral coverage in pregnant women, reaching 68% of all pregnant women living with HIV and achieving more than a 40% reduction in transmission rates (including during the breastfeeding period) since 2009 [1]. The move by many countries to lifelong treatment for all pregnant and breastfeeding women living with HIV may further accelerate the impact [1].

Despite this progress in scaling up EMTCT interventions, an estimated 240 000 (210 000–280 000) children were newly infected with HIV in 2013, globally [3]. Most of these new infections occurred in sub-Saharan Africa, where more than 90% of all children infected with HIV currently live. As paediatric testing and treatment are scaled up more effectively, a larger proportion of children are expected to survive and be in need of antiretroviral therapy (ART). The latest estimates indicate that in 2013, among the 3.2 million (2.9 –3.5 million) children younger than 15 years living with HIV, only 24% (22–26%) were receiving treatment compared with 38% (36–40%) ART coverage for adults [3]. Poor access to early infant diagnosis, as well as diagnosis during and after breastfeeding, weak linkage to care and treatment programmes and the limited capacity in managing paediatric HIV by non-specialized personnel have been identified as some of the barriers to a more effective implementation of paediatric treatment in low and middle-income countries [4].

The WHO-consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection [5] have tried to address some of the programmatic challenges by simplifying treatment initiation criteria such that all children living with HIV younger than 5 years of age should now initiate ART irrespective of CD4+ cell count or WHO clinical stage. Although first-line ART for children has also been simplified to some extent, further simplification and harmonization between age groups remains challenging, and different approaches are recommended based on age due to available formulations and safety profiles, which vary by age. Children below 10 years of age are therefore in need of drugs and formulations which are different from that of adults.

In this context, urgent efforts are needed to ensure a continuous and reliable supply of paediatric antiretrovirals and to develop suitable formulations which enable implementation of existing treatment recommendations in settings with the highest burden of paediatric cases. Forecasting demand for antiretrovirals and developing a longer-term perspective of future needs is therefore critical to ensure adequate production and encourage manufacturers to invest in new formulations. Unfortunately, data to accurately assess the number of children in need of ART or to predict uptake of treatment recommendations in different settings and age groups are very limited. As a result, forecasting the demand for paediatric drugs and formulations remains challenging with the risk of potentially undermining the expansion of paediatric treatment programmes if there is an underestimation of the future burden of paediatric HIV cases.

In this study, we describe three scenarios developed with Spectrum to explore the expected future changes in the numbers of children living with HIV and the overall number of children needing ART by 2020. We therefore focused on characterizing the paediatric population affected by HIV to develop a long-term estimate of the need for paediatric antiretrovirals that can inform drug procurement, as well as future drug and formulation research and development to enable closing the paediatric treatment gap.

Methods

Data used for this analysis were derived from national models of HIV impact developed in 2014 by national HIV estimate teams with support from UNAIDS. National models were created using Spectrum software (version 5.03) to forecast the impact of different scenarios on paediatric need for ART. Spectrum provides a suite of modules to estimate the impact of different interventions for programming and policy decisions. The AIDS Impact Module (AIM) in Spectrum uses background demographic data from the United Nations Population Division 2012 revision World Population Prospects, HIV prevalence from recent surveillance activities, and programme data on number of people receiving ART or antiretroviral medicines to prevent vertical transmission [prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT)] to project the impact of HIV over time. Scenarios of programme coverage for ART and PMTCT in future years can be adjusted by the user.

The model relies on a number of key assumptions to determine the transmission levels and the impact on the population. Additional information on the Spectrum model is available from Futures Institute (www.futuresinstitute.org), and information on the collection of Spectrum files from countries is available from www.UNAIDS.org. Additional information on the development of the model and the assumptions in the model is available at www.epidem.org.

The model allows the user to project the impact of different interventions into the future. For this analysis, we have adjusted the coverage of ART and PMTCT between the years 2014 and 2020 to estimate impact. Adult incidence in the model is assumed to follow a similar trajectory as in previous years [3], with incidence decreasing as ART coverage among adults increases (in addition, see Brown et al’., this supplement).

Vertical transmission

HIV infection among children aged 0–14 years only occurs through vertical transmission in Spectrum. The number of pregnant women living with HIV is based on HIV prevalence in the general female population, age-specific fertility rates and an age-specific adjustment to reflect variations in fertility among HIV+ and HIV− women. In some countries, HIV prevalence among pregnant women in Spectrum will not match perfectly with the HIV prevalence from antenatal clinic (ANC) surveillance as the ANC surveillance is usually among a select set of ANCs which do not necessarily represent the full population. In the AIM module, the ANC HIV prevalence level is adjusted to reflect the national population using data from nationally representative household surveys. The probability of vertical transmission depends on the antiretroviral regimen provided, the CD4+ level of the mother and the infant-feeding practices. The probability of vertical HIV transmission for different PMTCT regimens and CD4+ level is described elsewhere [6]. In brief, the transmission for women who have started on a triple-combination regimen before the current pregnancy is 0.5% during the pregnancy and delivery, and 0.16% per month for each month of breastfeeding. Transmission among women who start on a triple regimen during pregnancy is 2% during pregnancy and delivery, and 0.2% for every month of breastfeeding. These values are the individual-level probability of transmission. The population-level transmission rates will be higher because they include the transmission from women who did not receive any prophylaxis to prevent vertical transmission. Figure 1 includes the key variables that are modified in Spectrum to estimate paediatric treatment needs.

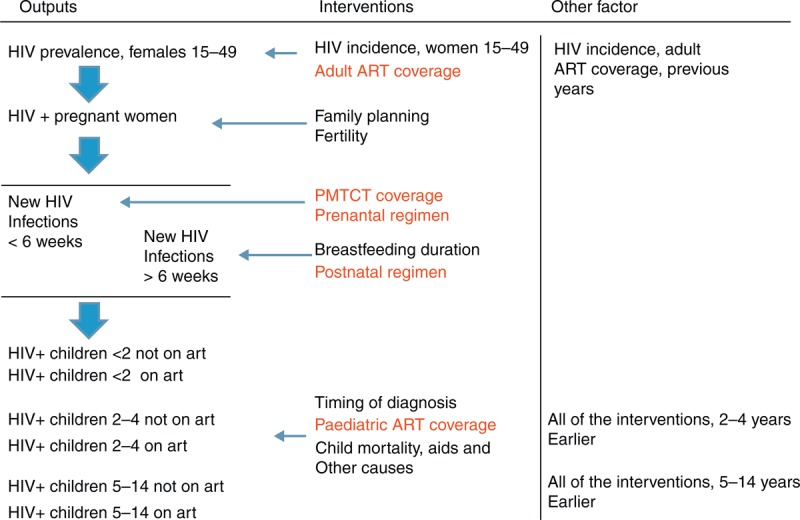

Fig. 1.

Components of Spectrum model to estimate paediatric treatment needs.

This figure illustrates the key components and transitions that allow estimation of paediatric ART need. Key parameters attached to those transitions are also listed as ‘interventions’ (intervention modified to develop the 3 scenarios are in red). Finally, other factors that play a significant role in the model are listed on the right side of the figure.

Child survival

In brief, Spectrum assumes that survival from infection to death among children depends on the timing of infection. Children infected perinatally (in utero and intrapartum) will survive on average less than 1 year, whereas those infected during the first 6 months of life will more likely survive for 5–6 years without ART. Those who are infected after 6 months are likely to live an average of 14 years [7]. Further descriptions of the sources of the probability of survival for adults and children, on and off ART, are described elsewhere [8,9].

In the setting of ART scale-up, the model assumes that 85% of children who start on ART will survive the first year and that percentage will increase to 93% for all subsequent years. The mortality rates are inclusive of country-specific background mortality to which the AIDS deaths are added.

Scenarios

For this analysis, we created three scenarios to describe a situation of stable programme coverage, likely scale-up of programmes, and optimal scale-up of coverage (Table 1).

Table 1.

Final antiretroviral therapy and prevention of mother-to-child transmission coverage level in 2020 by scenario (stable, likely, optimal), 21 priority countriesa.

| Stable | Likely | Optimal | |||||||

| PMTCT% | Adult ART% | Ped ART% | PMTCT% | Adult ART% | Ped ART% | PMTCT% | Adult ART% | Ped ART% | |

| Chad | 32 | 31 | 7 | 75 | 75 | 40 | 95 | 95 | 100 |

| Nigeria | 30 | 53 | 17 | 75 | 75 | 40 | 95 | 95 | 100 |

| DR Congo | 27 | 51 | 11 | 75 | 75 | 40 | 95 | 95 | 100 |

| Angola | 39 | 49 | 25 | 75 | 75 | 40 | 95 | 95 | 100 |

| Cameroon | 63 | 33 | 10 | 75 | 75 | 40 | 95 | 95 | 100 |

| Lesotho | 53 | 40 | 22 | 85 | 85 | 50 | 95 | 95 | 100 |

| Ethiopia | 55 | 66 | 14 | 85 | 85 | 50 | 95 | 95 | 100 |

| Burundi | 58 | 65 | 18 | 85 | 85 | 50 | 95 | 95 | 100 |

| Ghana | 62 | 73 | 21 | 85 | 85 | 50 | 95 | 95 | 100 |

| Tanzania | 73 | 74 | 25 | 85 | 85 | 50 | 95 | 95 | 100 |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 75 | 56 | 14 | 85 | 85 | 50 | 95 | 95 | 100 |

| Uganda | 75 | 58 | 32 | 85 | 85 | 50 | 95 | 95 | 100 |

| Mozambique | 88 | 65 | 38 | 95 | 95 | 75 | 95 | 95 | 100 |

| Kenya | 70 | 77 | 43 | 95 | 95 | 75 | 95 | 95 | 100 |

| Zimbabwe | 82 | 80 | 37 | 95 | 95 | 75 | 95 | 95 | 100 |

| Malawi | 83 | 81 | 46 | 95 | 95 | 75 | 95 | 95 | 100 |

| Namibia | 91 | 88 | 51 | 95 | 95 | 75 | 95 | 95 | 100 |

| Zambia | 95 | 94 | 46 | 95 | 95 | 75 | 95 | 95 | 100 |

| South Africa | 89 | 77 | 68 | 95 | 95 | 100 | 95 | 95 | 100 |

| Botswana | 96 | 87 | 99 | 95 | 95 | 100 | 95 | 95 | 100 |

| Swaziland | 100 | 86 | 61 | 95 | 95 | 100 | 95 | 95 | 100 |

The assumed coverage rates for PMTCT, adult ART and Paediatric ART in 2020 varies by scenario, with the stable scenario reflecting current coverage levels and the likely and optimal scenarios showing different levels of coverage scale-up. ART, antiretroviral therapy; PMTCT, prevention of mother-to-child transmission.

aScale-up between 2013 and 2020 was assumed to be linear.

The stable scenario maintained the same proportion of people receiving treatment (PMTCT or ART) from 2013 to 2020. The same PMTCT regimen used in 2013 is maintained through 2020.

The likely scenario assumed an aspirational, but plausible, scale-up with coverage increases depending on the existing achievements. Countries were separated into three categories of relatively low coverage in 2013, medium coverage in 2013 and high coverage in 2013. On the basis of those categories, the percentage of pregnant women who received antiretroviral medicine for PMTCT and eligible adult women who received ART were scaled up to 75, 85 and 95%, respectively. The proportion of eligible children receiving ART was very low for most of these countries. Thus, the scale-up was more gradual at 40% for the low-coverage countries, 50% for the medium-coverage countries and 75% for the high-coverage countries. For the three countries that had already reached at least 60% paediatric ART coverage, the goal was set at 100%. Pregnant women living with HIV who are reached by the PMTCT programme are started on a lifelong triple antiretroviral drug regimen from 2014 onwards. Drop-out during the postnatal period is not adjusted from the default values of 2.2% per month.

The optimal scenario assumes that all countries would achieve 95% female adult ART and PMTCT coverage by 2020. Again, the PMTCT regimen provided is lifelong triple therapy, or option B+ and drop-out during the postnatal period is not adjusted from the default values of 2.2% per month. Paediatric ART coverage is assumed to reach 100% to fully assess the total need for paediatric antiretrovirals.

We have split the age groups into groups relevant for drug-forecasting exercises. These groups are 0–3, 4–9 and 10–14-year-olds. We do not consider adolescents 15–19 years of age in this analysis.

Results

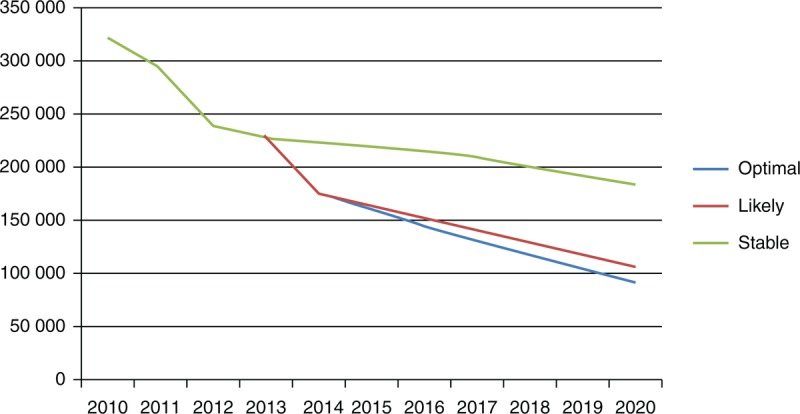

Figure 2 demonstrates the expected impact of adult ART, PMTCT and paediatric ART coverage on the number of new child infections from 2010 to 2020. New infections in the 21 countries will decline from 320 000 (290 000–350 000) (2010) to 180 000 (170 000–210 000) in the stable scenario, 110 000 (97 000–120 000) in the likely scenario and 94 000 (85 000–100 000) in the optimal scenario by 2020. While in 2020 40% of the new infections will occur by 6 weeks in the stable scenario, the proportion will increase to 52 and 55% in the likely and optimal scenarios, respectively, as more women are receiving ART throughout the breastfeeding period in the likely and optimal scenarios.

Fig. 2.

Estimated annual new child infections by scenarios (2010–2020, 21 priority countries).

The green line presents the number of new child infections in a scenario where ART and PMTCT coverage remains stable through 2020. The red and blue lines show the number of new child infections in scenarios where ART and PMTCT coverage are scaled up more quickly in likely and optimal scenarios. ART, antiretroviral therapy; PMTCT, prevention of mother-to-child transmission.

Total paediatric infections will also decline from 2010 in the 21 high-burden countries, but with a differential effect by scenario and age group. By 2020, in the optimal scenario the estimated number of children living with HIV will be about 1 940 000 (1 760 000–2 120 000). In the likely and stable Scenarios, this number is estimated to be about 1 860 000 (1 690 000–2 040 000) and 2 220 000 (2 010 000–2 420 000), respectively (Fig. 3).

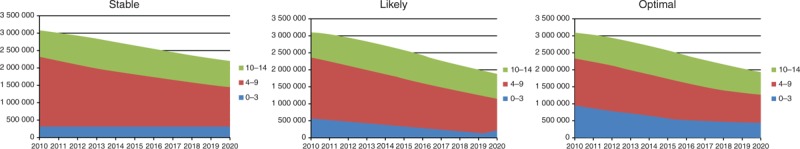

Fig. 3.

Number of children living with HIV by age group (2010–2020, 21 priority countries).

The three figures show the distribution of children living with HIV by age group.

In 2010, there were an estimated 3 120 000 (2 870 000–3 370 000) children living with HIV of whom 30% were aged 0–3 years, 45% were aged 4–9 years and 24% were aged 10–14 years. Figure 3 illustrates that the total number of children aged 0–3 years will decline from 940 000 (870 000–1 020 000) in 2010 (all scenarios) to 460 000 (420 000–500 000) in the optimal, 360 000 (330 000–390 000) in the likely and 550 000 (500 000–600 000) in the stable scenarios by 2020. Among children aged 4–9 years, there will be a decline from 1 410 000 (1 300 000–1 530 000) in 2010 (all scenarios) to 810 000 (730 000–880 000) in the optimal, 770 000 (700 000–840 000) in the likely and 910 000 (830 000–1 000 000) in the stable scenarios by 2020. Among children aged 10–14 years, there will be a decline from 760 000 (700 000–830 000) in 2010 (all scenarios) to 670 000 (610 000–730 000) in the optimal, 740 000 (670 000–800 000) in the likely scenario and 750 000 (680 000–820 000) in the stable scenarios by 2020.

The numbers of children dying of AIDS between 2015 and 2020 are notably different in the three models, and this explains the differences in the total number of children living with HIV in the three scenarios. In the year 2020, we estimate that there would be 570 000 (520 000–630 000) deaths in the optimal scenario; in the likely scenario there would be 710 000 (640 000–770 000) deaths and in the stable scenario, the number would be 800 000 (730 000–880 000).

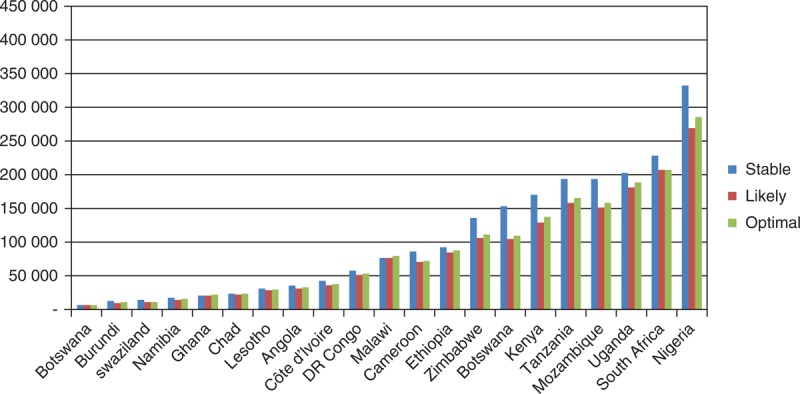

Under all scenarios, the largest burden of paediatric HIV will occur in Nigeria by 2020, accounting for 18.6–18.8% of all paediatric infections among the 21 countries (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Number of children living with HIV under the age of 15, by scenario (2020, 21 priority countries).

ART and PMTCT scale-up will have different potential impacts in each country. The projected number of children living with HIV in each country varies from less than 10 000 in Botswana to over 350 000 in Nigeria.

Under the scale-up scenarios, the estimated number of children who will receive ART in the 21 high-burden countries will increase from 310 000 (in 2010) to 1 670 000 in the optimal scenario, 950 000 in the likely scenario and 600 000 in the stable scenario by 2020.

Discussion

The estimates presented here demonstrate that new and current infections will contribute to a significant number of children living with HIV who will continue to require care and treatment until 2020 and beyond.

The three scenarios illustrated appear very similar in absolute numbers, which may initially be surprising. However, underlying dynamics in the three scenarios are significantly different. It is important to note that the main drivers of the total number of HIV-infected children are: number of pregnant women infected with HIV, vertical transmission rates and child survival.

In the context of suboptimal scale-up of ART interventions for adults, pregnant women and children, as illustrated in the stable and likely scenario, a considerable number of new infections will still occur and survival will be affected by the high mortality associated to HIV, especially in the first 2 years of life. If PMTCT is scaled up more effectively and the transmission rate is reduced to 8%, as illustrated in the optimal scenario, the number of new infections will decrease overall. However, as a result of better ART scale-up and underlying demographics, the total number of HIV-infected women who will become pregnant and potentially transmit the infection will increase substantially so that low transmission will still result in a considerable number of new infections which will continue to occur at least in the foreseeable future. In the same scenario, assuming paediatric treatment is also optimally scaled up, survival in HIV-infected children will increase and the aging cohort of children that are accessing care will continue contributing to the ART need observed in subsequent years.

The relatively high number of children who will continue acquiring the infection even under optimal scale-up of PMTCT interventions highlights the need to ensure timely diagnosis of HIV-infected infants, particularly outside the PMTCT programmes where the majority of the HIV-infected children will be found until PMTCT programmes are scaled up to all pregnant women. In addition, continuous efforts to develop appropriate drugs and formulations for infants and young children will need to be put in place to enable effective treatment of HIV infection when viral load is higher and disease progression faster.

At the same time, as more children survive and start on treatment at earlier ages, more children will survive into adolescence. This emphasizes the need for appropriate service delivery models for older children and adolescents which should include implementation of treatment strategies that optimize available drugs and formulations, including robust second and third-line options, in the context of life-long treatment.

We recognize a number of limitations to our findings which can be broadly related to the structure of the underlying model, the validity of the assumptions and the quality of the data input. The Spectrum model was developed accounting for demographics, disease progression and mortality patterns on and off ART across populations; however, there are a number of elements that are relevant to the paediatric population that may not be fully captured. For instance, the model considers vertical transmission as the unique mode of transmission in paediatrics and therefore does not account for horizontal transmission, which may occur as a result of nosocomial transmission (including blood transfusion) or through sexual abuse [10,11]. While overall this may explain only a marginal additional proportion of infections, it is likely to underestimate the total number of children infected with HIV in some countries. As PMTCT programmes are scaled up, non-vertical transmission may emerge as a more important driver of paediatric infections.

Adherence to ART interventions and retention in the diagnostic and treatment cascade is only partially captured. As a result, effectiveness of treatment interventions in reducing the number of new infections or in prolonging survival is potentially overestimated.

Spectrum currently assumes that the overall ART coverage reported by countries for the paediatric population applies equally across childhood. This does not unfortunately capture the limited uptake of treatment in the first 2 years of life, which is closely related to the limited scale-up of infant diagnosis and the poor linkage to care and treatment for those that are positive. Since mortality off ART is up to 50% in the first 2 years of life [12], overestimation of treatment coverage in this age group may have a significant impact on the overall survival estimates of HIV-infected children.

Efforts were made in the model to capture age-related mortality pre-ART and on ART. The assumptions in the model about mortality for children who have not yet started ART come from the only available data in a pre-ART setting which are based in Europe and might not reflect the situation in Africa. The mortality among children on ART has also been difficult to accurately reflect due to small sample sizes in the available research data. As a result, accuracy in estimating survival and the total number of children living with HIV may be gained in revising the model to reflect most recent estimates emerging from large cohort collaborations that represent mortality trends in a number of different regions across the world.

Finally, the quality of country-level programme data used as model inputs represents a limitation to this analysis, potentially resulting in inaccuracy in the numbers of people receiving antiretroviral medicines at the start of the projection period (whether ART or PMTCT). National health information systems are weak in a number of countries represented here with substantial double-counting or undercounting. There are very weak data on whether mothers are adhering to prophylaxis during the postnatal period. The default values of women dropping out of postnatal prophylaxis are rarely updated to reflect the national situation by countries.

In light of these limitations, the WHO Paediatric Antiretroviral Drug Optimization Meeting that was convened in Dakar in 2013 and brought together a range of key stakeholders, has recommended further elaboration of this model to accurately develop paediatric estimates that can guide drug development and forecasting. The UNAIDS Reference Group on Estimates, Modeling and Projections is currently working to refine the child model within Spectrum to better capture these nuances. However, without the country-specific data to enter into the programme, the model is limited in its ability to estimate the current situation.

In conclusion, paediatric HIV remains an unfinished business as1.86–2.22 million children are expected to be living with HIV in 2020. These estimates highlight the transmission that will continue to occur despite effective PMTCT interventions being scaled up and emphasize the critical value of identifying infants early, optimizing drug development that matches the age-appropriate needs and the scale-up of service delivery models that allow full uptake of ART for those in need. In this context, improved modelling of the paediatric HIV epidemic needs to be urgently refined to inform target-setting and allow forecasting of age-appropriate drugs and formulations to rapidly close the paediatric treatment gap, thus ensuring that fewer children are infected with HIV, and no HIV-infected children die from the disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Raul Gonzalez-Montero and Meg Doherty of the World Health Organisation.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. 2013 Progress report on the global plan towards the elimination of new HIV infections among children and keeping their mothers alive. Geneva, 2013. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2013/20130625_progress_global_plan_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Townsend CL, Byrne L, Cortina-Borja M, Thorne C, de Ruiter A, Lyall H, et al. Earlier initiation of ART and further decline in mother-to-child HIV transmission rates, 2000–2011. AIDS 2014; 28 7:1049–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The UNAIDS Gap Report. UNAIDS; 2014. www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2014/UNAIDS_Gap_report_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. March 2014 supplement to the 2013 consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. Geneva; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013, www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/arv2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rollins N, Mahy M, Becquet R, Kuhn L, Creek T, Mofenson L. Estimates of peripartum and postnatal mother-to-child transmission probabilities of HIV for use in Spectrum and other population-based models. Sex Transm Infect 2012; 88 Suppl 2:i44–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marston M, Becquet R, Moulton LH, Gray G, Coovadia H, et al. Net survival of perinatally and postnatally HIV-infected children: a pooled analysis of individual data from sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Epidemiol 2011; 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stover J, Brown T, Marston M, et al. Updates to the Spectrum/Estimation and Projection Package (EPP) model to estimate HIV trends for adults and children. Sex Transm Infect 2012; 88 Suppl 2:i11–i16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yiannoutsos CT, Johnson LF, Boulle A, Musick BS, Gsponer T, Balestre E, et al. Estimated mortality of adult HIV-infected patients starting treatment with combination antiretroviral therapy. Sex Transm Infect 2012; 88 Suppl 2:i33–i43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaz P, Pedro A, Le Bozec S, Macassa E, Salvador S, Biberfeld G, et al. Nonvertical, nonsexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2010; 29:271–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiemstra R, Rabie H, Schaaf HS, Eley B, Cameron N, Mehtar S, et al. Unexplained HIV-1 infection in children: documenting cases and assessing for possible risk factors. SAMJ 2004; 94:188–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newell M, Coovadia H, Cortina Borja M, Rollins N, Gaillard P, Dabis F. Mortality of infected and uninfected infants born to HIV-infected mothers in Africa: a pooled analysis. Lancet 2004; 364:1236–1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]