Abstract

This study investigated inconsistent responding to survey items by participants involved in longitudinal, web-based substance use research. We also examined cross-sectional and prospective predictors of inconsistent responding. Middle school (N = 1,023) and college students (N = 995) from multiple sites in the United States responded to online surveys assessing substance use and related variables in three waves of data collection. We applied a procedure for creating an index of inconsistent responding at each wave that involved identifying pairs of items with considerable redundancy and calculating discrepancies in responses to these items. Inconsistent responding was generally low in the Middle School sample and moderate in the College sample, with individuals showing only modest stability in inconsistent responding over time. Multiple regression analyses identified several baseline variables—including demographic, personality, and behavioral variables—that were uniquely associated with inconsistent responding both cross-sectionally and prospectively. Alcohol and substance involvement showed some bivariate associations with inconsistent responding, but these associations largely were accounted for by other factors. The results suggest that high levels of carelessness or inconsistency do not appear to characterize participants’ responses to longitudinal web-based surveys of substance use and support the use of inconsistency indices as a tool for identifying potentially problematic responders.

Keywords: inconsistency, response style, internet, web based, longitudinal, validity, substance use

Introduction

Computer ownership and Internet access have grown dramatically in the past decade. In turn, the use of web-based assessments in psychological research has become commonplace (Gosling, Vazire, Srivastava, & John, 2004; P. G. Miller & Sonderlund, 2010). Web-based data collection has many advantages over laboratory-based paper-and-pencil assessments, including greater cost-effectiveness, feasibility, and time-efficiency. Online assessment also offers a greater sense of privacy and anonymity. This makes it a useful approach for substance use research, which typically involves the assessment of sensitive information or socially undesirable behaviors. Furthermore, web-based longitudinal studies—involving repeated and often frequent assessment of large groups of individuals—can be conducted with far fewer resources than other approaches would require. Though there is a burgeoning literature examining the psychometric properties of online measures, the extent to which the benefits of web-based assessment methods for longitudinal substance use research may come at a cost to the quality of the data is in need of further investigation.

As adolescence and young adulthood represent critical developmental periods in which substance use initiation and escalation typically occur (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2012), reliable and valid assessment of substance use in these age groups is crucial for elucidating the development of problematic substance use. Furthermore, longitudinal research is necessary to test developmental theories of substance use initiation and escalation. This involves assessment of both substance use behavior and predictors of substance use, including personality and cognitive factors, as well as other risk and protective factors that may predict the onset of substance use (especially in young adolescents). For a number of reasons, web-based methods are well suited to the study of substance use in youths and particularly for the longitudinal examination of substance use behaviors across important developmental periods. One advantage is that Internet use among America’s youth is ubiquitous. Ninety-five percent of adolescents aged 12 to 17 report using the Internet at least occasionally, and 70% of these are daily users (Pew Research Center, 2011). Also, 85% of adults over the age of 18 report Internet use (Rainie, 2012). Research shows that computer-based or online assessments encourage greater disclosure of substance use behavior by adolescents and young adults relative to traditional face-to-face or paper-and-pencil methods (Link & Mokdad, 2005; Turner et al., 1998; Wright, Aquilino, & Supple, 1998). Also, online methods are more convenient for participants, as they can be completed in the privacy of participants’ own home at a time of their choosing. This flexibility is especially important for longitudinal research, which may pose a burden to participants over time. Given widespread access to the Internet, web-based methods have been used extensively to assess alcohol and other substance use behaviors in adolescents and young adults (P. G. Miller & Sonderlund, 2010; Saitz et al., 2004; Sher & Rutledge, 2007).

Yet does such convenience come at a cost to the quality of the data? As Buchanan, Johnson, and Goldberg (2005) noted, with Internet assessment investigators give up substantial control over assessment conditions. The flexibility, privacy, and independence that make Internet assessment attractive may also make this approach vulnerable to inattentive, misguided, or even deliberately misleading responses (see also Reips, 2000; Schmidt, 1997). The fact that research participants often receive monetary or other incentives for their participation could compound this risk, as individuals may rush through their assessment without giving it sufficient attention in order to qualify for compensation. Though these concerns are not unique to web-based assessment, there have been relatively few studies examining the validity of participant’s responses to online surveys (e.g., Huang, Curran, Keeney, Poposki, & DeShon, 2012; Johnson, 2005; Meade & Craig, 2012). Thus, more research on the quality of data collected through online surveys is needed, especially in the context of longitudinal substance use research.

Inconsistency in Survey Responses

Participant response style to questionnaire items has long been of interest to the field of psychological assessment. For example, many clinical assessment batteries, such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (Butcher, Dahlstrom, Graham, Tellegen, & Kaemmer, 1989), include scales designed to quantify the validity of participant responses. A common type of validity scale that attempts to capture random or haphazard responding is an inconsistency index (see McGrath, Mitchell, Kim, & Hough, 2010). Inconsistency indices are derived by administering several pairs of items with highly redundant content, to which participants should provide similar responses. Discrepancies on responses to these highly similar items may indicate a lack of attention to the content or otherwise haphazard responding (Huang et al., 2012; Meade & Craig, 2012). These types of inconsistency analyses rarely have been employed in studies of substance use. When substance use researchers have assessed inconsistency, they have tended to limit the analysis to inconsistent reporting of substance use behavior itself (e.g., endorsing abstinence but also reporting recent use; Farrell, Danish, & Howard, 1992).

Furthermore, no studies to our knowledge have examined inconsistent responding in the context of longitudinal web-based substance use research, where the ability to monitor and provide feedback to participants showing signs of reactivity is limited. Thus, it is important to examine how inconsistency in responding might change across repeated assessments in these studies. Indeed, it is possible that participants may be more motivated to pay attention and provide valid data early in a study, but that they become bored with the study over time and fall into more rushed, haphazard response patterns. The degree to which inconsistency increases over time in a longitudinal study likely depends on several factors, including the frequency of assessment (i.e., daily assessments might cause more participant fatigue and lead to more inconsistency than yearly assessments) and the length of the survey (i.e., repeated assessments may cause more reactivity if each assessment takes several hours to complete rather than a few minutes). Still, even in studies with relatively brief assessments spaced out over longer intervals, it is possible that participants may become increasingly hasty or careless when they are asked to respond to the same questions they have previously answered several times. Moreover, identification of inconsistency may aid in data quality assurance in longitudinal research, as such response patterns can be identified early so that corrective action can be taken to discourage future inconsistency.

Factors Associated With Inconsistent Responding

Identifying factors that predict inconsistency both cross-sectionally and prospectively is important, as these variables could be used to determine which participants may be at risk for providing inconsistent responses over time. For example, individuals with particular personality characteristics may be likely to react more negatively to repeated assessments (e.g., those high on neuroticism, low on agreeableness, or high on impulsivity/sensation-seeking), resulting in increased inconsistent responding over time. Studies using the NEO-PI-R—a popular measure of the Big Five personality traits of Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness—have tended not to find relationships among these personality traits and scores on indices of inconsistent responding (Kurtz & Parrish, 2001; Schinka, Kinder, & Kremer, 1997). However, these studies did not examine prospective relationships among personality traits and inconsistency. Thus, whether and how personality influences inconsistent responding to survey items over the course of a longitudinal study is unknown. The present study provides such an examination.

Moreover, to the extent that heavier substance use is associated with characteristics that pose a risk for inconsistent responding, it is important to examine whether substance use and correlates of substance use are predictive of inconsistency. For example, substance use among adolescents and young adults is often part of a larger constellation of behavioral, cognitive, and emotional dysregulation. This includes risk factors for substance use such as delinquency, aggression, poor executive functioning, and negative affect (Aytaclar, Tarter, Kirisci, & Lu, 1999; Colder & Chassin, 1993; Giancola, Mezzich, & Tarter, 1998), all of which could influence an individual’s approach to an online survey and predict inconsistent responding. In addition, factors that protect against substance use in adolescents, such as parental monitoring and school engagement (Aunola, Stattin, & Nurmi, 2000; Barnes, Hoffman, Welte, Farrell, & Dintcheff, 2006; Bryant, Schulenberg, O’Malley, Bachman, & Johnston, 2003), may correlate negatively with general dysregulation and therefore might predict low inconsistency in survey responses. Given our goal of investigating inconsistent responding in the context of longitudinal substance use research, we examined the extent to which substance use and related variables (personality, risk, and protective factors) were associated concurrently and prospectively with inconsistency in responses to survey items.

The Present Study

This study examined inconsistent responding in longitudinal studies of substance use and predictors of this inconsistency. Using samples from two separate longitudinal studies—one comprising adolescents in middle school (Middle School sample) and one comprising young adults in college (College sample)—we applied an approach to creating indices of inconsistent responding to survey items. Our first goal was to investigate the extent of response inconsistency in data collected from repeated online assessments. We conducted a descriptive analysis of inconsistency within each time point and also examined whether early patterns of inconsistent responding would predict continued inconsistency. We hypothesized that participants would show stability in their response styles, such that early inconsistent responders would continue to respond inconsistently over time. We also predicted an increase in overall levels of inconsistency over time, as some participants may become bored with repeated assessments and become increasingly careless. Finally, we examined the relationship between inconsistent responding and individual differences in substance use as well as in demographic and personality factors. We hypothesized that inconsistent responding would be associated with characteristics that are typically related to carelessness or difficulty regulating behavior or emotions, such as substance use and associated consequences, risk factors for substance use (delinquency and poor school engagement), and certain personality traits (i.e., low conscientiousness, high neuroticism, high impulsivity).

Method

Participants and Procedure

Middle School Sample

Students (N = 1,023) from six Rhode Island middle schools (Grades 6, 7, and 8) were invited to participate in a 3-year study on alcohol initiation and progression among early adolescents. Using a cohort-sequential design (Nesselroade & Baltes, 1979), the cohorts were staggered such that the first cohort was enrolled in October 2009 and the last cohort was enrolled in October 2011. Students were sampled from two rural schools (Cohort 1, n = 231), three suburban schools (Cohort 2, n = 192; Cohort 4, n = 89; Cohort 5, n = 227), and an urban inner-city school (Cohort 3, n = 284). We used data from the first three waves, which were spaced 6 months apart. Participants were roughly equally divided across the three grades (33% in 6th grade, 32% in 7th grade, and 35% in 8th grade), with a mean age of 12.22 years (SD = 0.98, range = 10–15). Just more than half were female (52%). Seventy-two percent of the participants were Caucasian, 4% were African American, 12% were Hispanic, and 12% were other race/ethnicity.

The 45-minute baseline (Wave [W] 1) assessment was administered as a web-based survey, but completed at the schools on laptops provided by the study. Study staff monitored the participants and were available to answer questions but made efforts to maintain the autonomy and privacy of the participants. The 45-minute follow-up surveys (W2, W3) were web-based and could be completed from any location with Internet access. For each follow-up survey completed, the students were compensated with a $20 mall gift card; they received a $25 gift card at baseline. Retention rates were high, with 92% (n = 937) of participants completing the W2 survey and 88% (n = 901) completing the W3 survey.

College Sample

Matriculating college students were recruited for a longitudinal, web-based study investigating traumatic stress and substance use (see Read, Colder, Merrill, Ouimette, White, & Swartout, 2011). All incoming students between the ages of 18 and 24 at two mid-sized public universities—one in the Northeastern (Cohort 1, Fall 2006; Cohort 3, Fall 2007) and one in the Southeastern United States (Cohort 2, Fall 2007)—were invited to take part in a screening survey. From this screen sample, those meeting certain criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and an equal number of control participants were selected to take part in the longitudinal study. A total of 995 participants completed a baseline survey (W1) and provided enough data to derive an inconsistency index. The W1 survey was completed online by participants in September of their first year of college. Participants completed follow-up assessments at the end of their first year (April; W2) and the beginning of their second year of college (September; W3). Participants were compensated with retail gift cards ($20 for W1 and W2, $25 for W3). Retention rates were high, with 88% (n = 875) of participants completing the W2 survey and 92% (n = 920) completing the W3 survey.

Sixty-five percent of the participants were female (n = 648), and the mean age of participants at baseline was 18.12 years (SD = 0.45). Seventy-three percent of participants were Caucasian (n = 721), 11% were Asian (n = 113), 9% were African American (n = 90), 3% were Hispanic (n = 33), 3% were multiracial (n = 31), less than 1% reported another ethnicity (n = 3), and 4 participants did not report their ethnicities. At W1, roughly equal numbers of participants were living on campus (n = 454) or at home with family (n = 494), and only a small number were living off-campus not with family (n = 47).

Item Selection for Analyses of Inconsistent Responding

For both the Middle School and College samples, the same procedures were used to create ad hoc inconsistency indices, except there were differences between the samples in the specific items that were used in the indices given the different assessment batteries. In both samples, the analysis of inconsistency was accomplished by identifying pairs of survey items with considerable redundancy or conceptual overlap, such that participants responding in a certain way to one of the items in the pair should logically respond in a similar way to the other item. These item pairs were identified by first screening the pool of survey items for considerable redundancy among items. For example, one item on the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) asked participants to rate how much of the time they have felt scared, and another item asked them how much of the time they have felt afraid.

After this initial identification procedure, we examined the correlation between the items in each pair to provide an empirical confirmation of the redundancy among the items. In selecting items for the inconsistency analysis, a number of factors were considered. First, we limited the item pairs for the inconsistency index to those that were administered at all three waves. Second, we attempted to include items with both negatively and positively valenced content. Third, we sought to include at least one item pair comprising items from different measures entirely, in order to capture inconsistency across questionnaires. Fourth, we attempted to select pairs of items with an equivalent or roughly equivalent set of response options (i.e., both items rated on a 5-point scale with comparable anchors). For items with a slightly different set of response options, recoding was completed to equate the number of response categories while ensuring that the categories were as similar as possible.

Following these procedures, an inconsistency index consisting of seven item pairs was derived for the Middle School sample. This included two item pairs from a trait affect measure (PANAS-C; Laurent et al., 1999), two item pairs from an alcohol expectancy measure (Schell, Martino, Ellickson, Collins, & McCaffrey, 2005), and one item pair from a measure of parent reaction to youth drinking (adapted from Chassin, Presson, Todd, Rose, & Sherman, 1998). Additionally, we selected two intermeasure item pairs. One of these pairs assessed school attendance, consisting of an item from a measure of problem behaviors and an item from a school engagement scale (Bachman, Johnston, & O’Malley, 2005). The other pair assessed religious service attendance, consisting of an item from a measure of reinforcing activities and another item from a demographics questionnaire. We recoded the two pairs of intermeasure items to have similar meanings (e.g., “rarely” and “1–2 times per month” were combined to match “less than once per week”).

Following the same general procedure, an inconsistency index consisting of seven item pairs was derived for the College sample. Four item pairs came from a measure of state affect (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). From this measure, we selected the two pairs of items with the greatest amount of redundancy (based on the zero-order correlation) from each of the subscales (positive affect and negative affect). Two item pairs came from a measure of posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSD checklist [PCL]; Blanchard, Jones-Alexander, Buckley, & Forneris, 1996). The final item pair consisted of one item from the PANAS and one item from the PCL. Participants responded to all items on both measures using a 1 to 5 scale. See Table 1 for a description of the item pairs and the correlations between items for each of the samples.

Table 1.

Item Pairs Comprising the Inconsistency Indices and Correlations Between Items in Each Pair Across the Three Waves.

| Correlation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Item 1 | Item 2 | W1 | W2 | W3 |

| Middle School sample | |||||

| Within scale | |||||

| Alcohol | Act wild | Act clumsy | .78 | .84 | .88 |

| Expectancies | Act stupid | Have trouble thinking | .81 | .80 | .88 |

| PANAS | Sad | Upset | .71 | .81 | .85 |

| Cheerful | Joyful | .73 | .77 | .78 | |

| Parent reaction to youth drinking | Take something away (e.g., allowance) | Take away a privilege (e.g., watching TV) | .79 | .83 | .90 |

| Across scale | |||||

| Skipping school | Skipped school | Skip school all or part of day | .50 | .52 | .38 |

| Religious service attendance | Go to church | Attend religious services | .66 | .62 | .68 |

| College sample | |||||

| Within scale | |||||

| PANAS | Scared | Afraid | .72 | .72 | .72 |

| Distressed | Upset | .57 | .57 | .57 | |

| Excited | Enthusiastic | .59 | .66 | .66 | |

| Determined | Attentive | .58 | .60 | .62 | |

| PCL | Repeated, disturbing memories, thoughts, or images of the stressful experience(s) | Feeling very upset when something reminded you of the stressful experience(s) | .70 | .74 | .74 |

| Being “super-alert” or watchful or on guard | Feeling jumpy or easily startled | .68 | .78 | .75 | |

| Across scale | |||||

| Irritability | Irritable | Feeling irritable or having angry outbursts | .46 | .52 | .44 |

Note. All correlations are significant at the .01 level. PANAS = Positive and Negative Affects Schedule; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; PCL = PTSD Checklist; W = Wave.

Index Calculation

We calculated two different indices of inconsistent responding to be used for different purposes. The first of these (the descriptive index) was created to accomplish the first aim of the study, which was to describe the extent of inconsistent responding in our samples. Thus, we created an index that allowed us to examine raw discrepancies in responses to the redundant items in concrete terms. To do so, for each pair of items we calculated the absolute value of the difference between responses to the items. Then, we summed the observed discrepancy scores across the seven item pairs for each participant and rescaled this as a percentage of the maximum possible total discrepancy score. This made it easier to gauge the degree of inconsistency represented in the discrepancy score. For example, in the College sample all items in each pair were scored on a 5-point scale, so the possible discrepancy scores for each item pair ranged from 0 to 4. Because there were seven item pairs, the maximum possible total discrepancy was 28 (4 × 7). So, if a participant had a discrepancy of only one point for each item pair, his or her total discrepancy score would be 7, and this would translate to 25% (7/28) of the maximum total discrepancy. The same procedure for calculating this descriptive index of inconsistency was repeated using the same item pairs at all three waves. To ensure that the indices were homogenous across participants, we excluded participants at each time point who were missing data on three or more of the difference scores that comprised the indices. For the Middle School study, this resulted in sample sizes of 1,020, 925, and 881 at W1, W2, and W3, respectively. For the College study, this resulted in sample sizes of 995, 868, and 909 at W1, W2, and W3, respectively.

The second inconsistency index (the adjusted index) was calculated for the substantive analysis of predictors of inconsistency. This index adjusted the inconsistency scores to reduce the influence of the unique distributional properties of the items in the index. To do so, we first transformed all items into z-scores in order to equate the means and standard deviations across all items. Next, the absolute difference between the two transformed items in each pair of redundant items was calculated, and the mean of all of these difference scores was calculated to create the adjusted inconsistency index. Because each item in a pair was first standardized, scores on this index represent the average discrepancy in a participant’s relative response to each item. Standardizing items prior to calculating difference scores provided a clearer assessment of inconsistent responding by accounting for differences in the distributional properties of items. This also resulted in inconsistency scores that were more normally distributed and better suited to regression analyses. However, this yielded values that were not as intuitive to interpret, making it necessary to also report the descriptive inconsistency indices described above. As with the descriptive index, the adjusted index was calculated for each of the three waves in both samples, and we excluded participants who were missing data on three or more item pairs.

Measures for Prediction of Inconsistency: Middle School Sample

Demographics

Participants reported on several demographic characteristics including age, sex, and race/ethnicity. We dichotomized responses on the race and ethnicity questions into non-Hispanic White versus non-White and/or Hispanic.

Personality

To assess personality pathways to impulsive behavior, three subscales were taken from the Urgency, Premeditation, Perseverance, and Sensation seeking Impulsive Behavior Scale (Lynam, Smith, Whiteside, & Cyders, 2006): negative urgency, positive urgency, and sensation seeking. The set of items was preceded by the prompt, “For each statement, please indicate how much you agree or disagree with the statement.” Response options ranged from “Agree strongly” to “Disagree strongly.” Cronbach’s alphas were high for all three subscales: Negative Urgency, .84; Positive Urgency, .85; Sensation Seeking, .82.

Alcohol Involvement

Students were asked to report whether they had ever had a full drink of alcohol. Students provided a yes (1) or no (0) response.

Risk Factors

The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings, & Conners, 1997) consists of seven items measuring social anxiety in children and adolescents. For each item, students were asked to report how often each statement was true for them. Response options range from “Never true about me” to “Often true about me.” Cronbach’s alpha for this measure was .85. Students reported their level of life stress across six domains including school, friends, future, parents/family, job, and money. The items were based on the factors derived from Bobo, Gilchrist, Elmer, Snow, and Schinke’s (1986) factor structure of the 50-item Adolescent Hassles Inventory. Response options included, “No,” “Small/Minor Stress,” “Medium Stress,” and “Large/Major Stress.” Cronbach’s alpha for this measure was .73. The Problem Behavior Frequency Scale (PBFS) is a 20-item measure assessing aggression and delinquency and is adapted from the original 26-item measure (Farrell et al., 1992). Items were preceded by the prompt, “How often did you do these things in the past 30 days?” Response options ranged from “never” (1) to “20 times or more” (6). We used the six-item delinquency subscale (PBFS-D) in this study. Cronbach’s alpha for the PBFS-D was .80.

Protective Factors

The Parental Monitoring scale (Kerr & Stattin, 2000) is an eight-item measure assessing parents’ knowledge of children’s activities, whereabouts, and friends. Response options ranged from “No, never” (0%) to “Yes, always” (100%). Cronbach’s alpha for this measure was .88. School Engagement is a set of 12 items assessing enjoyment and perceived importance of schoolwork and school (Bachman et al., 2005). The first three questions asked about general attitudes and had three different 5-point response scales. The next nine questions were preceded by “Now thinking back over the past 12 (6) months when you were in school, how often did you …” Response options for these nine questions ranged from Never (1) to Almost always (5). Cronbach’s alpha for this measure was .80.

Measures for Prediction of Inconsistency: College Sample

Demographics

Participants reported on demographic characteristics including sex, age, and ethnicity.

Personality

The Big Five Inventory (John & Srivastava, 1999) is a 44-item self-report measure that assesses five personality dimensions: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. Items were rated on a 5-point scale that ranges from “disagree strongly” to “agree strongly.” In the current sample, the Big Five Inventory scales demonstrated acceptable internal consistency at W1 (α range = .72 to .85).

Alcohol Involvement

Participants who indicated that they had consumed alcohol at least once in the past month completed a measure based on the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985), which asked them to report the average number of standard drinks consumed on a typical Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, and so on, in the past 30 days. Respondents were provided with a definition of a standard drink. The number of drinks reported were summed across days to create a typical weekly quantity variable. Those participants who indicated that they had not consumed alcohol in the past month received a value of zero for weekly quantity. Consequences associated with alcohol consumption were assessed with the 48-item Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (Read, Kahler, Strong, & Colder, 2006). Items assess several domains of consequences, all of which load on a single, higher order consequences factor. Participants provided yes (1) or no (0) responses to indicate whether they had experienced that consequence in the past month. Participants reporting that they had abstained from alcohol in the past month received a value of zero. Cronbach’s alpha for this measure at W1 was .94.

Drug Involvement

Participants were asked to indicate the frequency with which they had used illicit drugs (i.e., cannabis, cocaine, stimulants, inhalants, sedatives or sleeping pills, hallucinogens, or opioids) in the past month. Responses ranged from never in the past month (0) to every day (6). Responses were averaged across the substance types to obtain a mean drug use frequency score. A 24-item questionnaire assessed negative consequences of drug use. The questionnaire was created by adapting items from the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Cronbach’s alpha for this measure in this sample was .92.

Results

Missing Data

In the Middle School sample, participants with complete data on the inconsistency indices at all three waves (n = 838) did not differ from participants with missing data (n = 185) on age, life stress, positive urgency, or sensation seeking (p > .05). Those with missing inconsistency data, however, had significantly higher inconsistency scores at W1, were more likely to be male, non-White, and to have ever had a full drink of alcohol (p < .05). Additionally, those with missing inconsistency data had significantly lower scores on social anxiety, negative urgency, parental monitoring, and school engagement, as well as higher delinquency scores (p < .05).

In the College sample, participants who had inconsistency scores at all three waves (n = 841) did not differ from those who were missing at least one of the inconsistency scores (n = 154) on gender, race/ethnicity, alcohol use, or consequences (p > .05). However, those with missing inconsistency scores at later waves had significantly higher inconsistency scores at W1, higher scores on neuroticism, lower scores on agreeableness and conscientiousness, as well as greater drug use and consequences at W1 (p < .05).

Descriptive Analysis of Inconsistent Responding

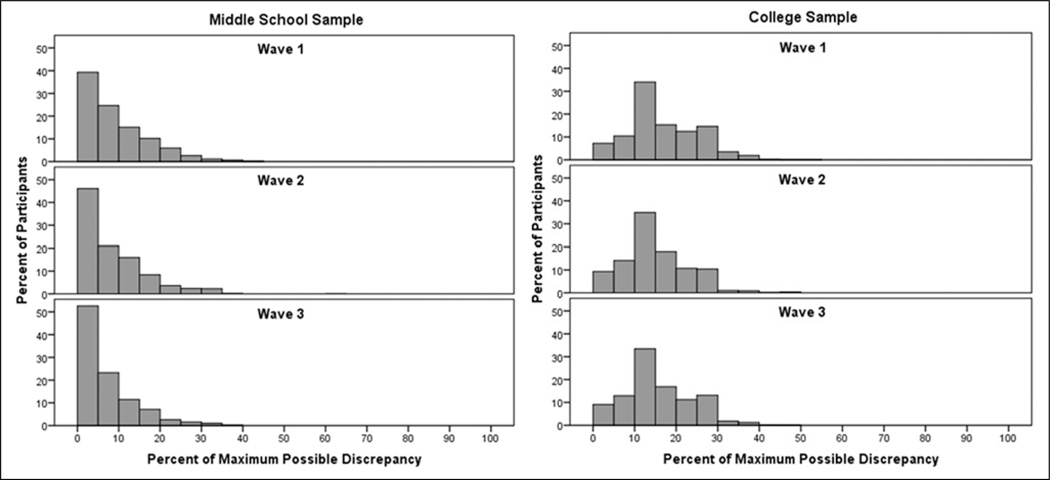

To provide a descriptive analysis of the extent of inconsistent responding in our samples, we first examined the descriptive index, which reflects the observed discrepancy in responses to similar items in terms of the percentage of the maximum possible discrepancy. Figure 1 shows the frequency distributions for this descriptive inconsistency index at each wave for both samples. As shown, both samples appeared to be characterized by generally low inconsistency in responding, although inconsistency appeared to be greater in the College sample than in the Middle School sample. Across the three time points, virtually all of the participants in the Middle School sample had values of less than or equal to 25% of the total possible discrepancy score (which is equivalent to a one point difference on a 5-point scale, on average), and 89% to 94% of these participants were at or below 10% of the maximum possible discrepancy. Across the three waves in the College sample, 88% to 94% of the students had scores on the descriptive index less than or equal to 25% of the maximum possible discrepancy score, and 32% to 41% had scores less than or equal to 10%.

Figure 1.

Frequency distributions for the descriptive inconsistency index, which represents the observed discrepancies in participants’ responses to similar items as a percentage of the maximum possible discrepancy score.

Note. Frequencies are shown separately for the Middle School and College samples and are displayed as a percentage of the total sample at each of the three waves of assessment.

Although these figures suggest a generally low level of inconsistency in responding overall, examination of the distributions reveals that a small amount of inconsistency was more typical than a complete absence of inconsistency. Indeed, the percentage of participants that had an average raw discrepancy of zero—meaning that they responded identically to both items in all seven item pairs—was fairly low (14% to 23% across the three waves for the Middle School sample and 1% to 3% across the three waves for the College sample). In the Middle School sample, the average participant displayed a modest amount of inconsistency in their responses to similar items as reflected in the sample means for the descriptive indices (M = 9.7, SD = 7.7 at Wave 1; M = 8.8, SD = 7.7 at Wave 2; and M = 7.5, SD = 6.9 at Wave 3), whereas the average student in the College sample exhibited a moderate amount of inconsistency (M = 16.58, SD = 8.25 at Wave 1; M = 14.77, SD = 7.69 at Wave 2; and M = 15.40, SD = 7.80 at Wave 3). Moreover, it appears that the discrepancies were fairly constant over time, with no marked increases or decreases in discrepancies over the three waves in either sample.

To further quantify the general level of inconsistent responding, for each sample we calculated weighted kappa coefficients for all seven item pairs at each time point. We then averaged the weighted kappa coefficients for each item pair. Weighted kappa provides an index of absolute agreement in responses to the items in each pair, weighting larger discrepancies (e.g., a 3- or 4-point difference) more heavily than smaller discrepancies (e.g., a 1- or 2-point difference) in order to arrive at a single value summarizing the extent of agreement. We applied guidelines from Landis and Koch (1977) for interpreting κ: ≤0 = poor agreement, .01 to .20 = slight agreement, .21 to .40 = fair agreement, .41 to .60 = moderate agreement, .61 to .80 = substantial agreement, and .81 to 1.00 = almost perfect agreement. Across the three waves, the average weighted kappas reflected substantial agreement in responses to the items in each pair for the Middle School sample (W1 = 0.62, W2 = 0.65, and W3 = 0.69) and moderate agreement in responses for the College sample (W1 = 0.46; W2 = 0.50; W3 = 0.49). These values converge with our examination of the frequency distributions of the discrepancy scores, suggesting that a moderate degree of inconsistency in responding was typical in both of our samples.

Substantive Analysis of Inconsistent Responding

Following our descriptive analysis of the extent of observed inconsistency, we proceeded to examine associations among the inconsistency indices and various factors that may be related to inconsistent responding. For these analyses, we used the adjusted inconsistency indices calculated from the z-score transformed items (see “Creation of Inconsistency Indices” above). The distributions for the adjusted inconsistency indices were not notably skewed and showed a reasonable degree of variability, despite the generally low levels of inconsistency found in the descriptive analysis. In both samples, all adjusted inconsistency indices roughly approximated normal distributions with small values for skewness (<2) and moderate kurtosis (<8). Thus, the assumption of normality for the regression analyses was reasonable.

Middle School Sample: Bivariate Associations

Table 2 shows the means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations among the adjusted inconsistency indices and the baseline demographic, personality, and substance use variables for the Middle School sample. The intercorrelations among the inconsistency scores across the three waves were all small to moderate (.27–.30). Non-White race/ethnicity was consistently correlated with higher scores on the indices. Substance use (ever having a full drink), positive urgency, stress, and delinquency also were correlated with higher inconsistency scores across all waves. Both parental monitoring and school engagement were negatively correlated with inconsistency scores.

Table 2.

Intercorrelations, Means, and Standard Deviations for the Middle School Sample.

| Wave 1 index | Wave 2 index | Wave 3 index | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inconsistency index | |||||

| Wave 1 | 0.39 | 0.28 | |||

| Wave 2 | .28*** | 0.36 | 0.27 | ||

| Wave 3 | .27*** | .30*** | 0.31 | 0.25 | |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age | −.02 | .05 | .01 | 12.22 | 0.98 |

| Female | .01 | .03 | .00 | 0.52 | 0.50 |

| Non-White | .17*** | .10** | .14*** | 0.17 | 0.38 |

| Personality | |||||

| UPPS: Positive Urgency | .13*** | .08* | .07* | 1.68 | 0.69 |

| UPPS: Negative Urgency | .07* | .06 | −.01 | 2.00 | 0.76 |

| UPPS: Sensation Seeking | −.06 | −.03 | −.07 | 2.18 | 0.80 |

| Substance use | |||||

| Ever full drink | .18*** | .10** | .13*** | 0.08 | 0.27 |

| Protective factors | |||||

| Parental monitoring | −.27*** | −.20*** | −.20*** | 4.13 | 0.83 |

| School engagement | −.28*** | −.20*** | −.16*** | 3.99 | 0.51 |

| Contributing/risk factors | |||||

| MASC: Social anxiety | .06 | .01 | −.03 | 7.14 | 5.27 |

| Stress | .10** | .09** | .07* | 0.80 | 0.58 |

| PBFS: Delinquency | .28*** | .21*** | .10** | 6.74 | 2.15 |

Note. UPPS = Urgency, Premeditation, Perseverance, and Sensation seeking; MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; PBFS = Problem Behavior Frequency scale.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p < .001.

College Sample: Bivariate Associations

Table 3 shows a similar pattern for the College sample, with small to moderate intercorrelations among the inconsistency indices across the three waves. Non-White race/ethnicity and female gender were generally correlated with higher scores on the inconsistency indices. Several of the personality variables had bivariate associations with the inconsistency indices across the three waves (higher neuroticism, lower agreeableness, lower conscientiousness at W1), as did alcohol consequences (but not alcohol use). Drug use and consequences were only correlated with inconsistency at W1.

Table 3.

Intercorrelations, Means, and Standard Deviations for the College Sample.

| Wave 1 index | Wave 2 index | Wave 3 index | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inconsistency index | |||||

| Wave 1 | 0.63 | 0.26 | |||

| Wave 2 | .25*** | 0.57 | 0.25 | ||

| Wave 3 | .22*** | .30*** | 0.58 | 0.26 | |

| Demographics | |||||

| Female | .05 | .08* | .10* | 0.65 | 0.48 |

| Non-White | .11** | .10** | .07* | 0.27 | 0.45 |

| Personality | |||||

| Extraversion | .02 | .02 | .01 | 3.42 | 0.77 |

| Agreeableness | −.15*** | −.10** | −.16** | 3.54 | 0.61 |

| Conscientiousness | −.09** | −.03 | −.07* | 3.53 | 0.66 |

| Neuroticism | .20*** | .17*** | .20*** | 3.07 | 0.85 |

| Openness | .01 | .07* | .08* | 3.87 | 0.61 |

| Substance use | |||||

| Alcohol Use | .02 | −.02 | .02 | 6.38 | 9.65 |

| Drug Use | .09** | .03 | .06 | 0.10 | 0.25 |

| Alcohol Consequences | .10** | .09* | .07 | 5.34 | 7.41 |

| Drug Consequences | .09** | .01 | .04 | 0.99 | 2.76 |

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p < .001.

Multivariate Prediction of Inconsistent Responding

Several of the personality, substance use, risk, and protective factors were correlated with one another. Thus, multiple regression analyses were conducted to determine which of these variables contributed uniquely to the prediction of inconsistent responding at each time point. In these models the above demographic, personality, and substance use variables, as well as protective and risk factors (Middle School sample only), measured at W1 were used to predict inconsistent responding both cross-sectionally (W1) and prospectively (W2 and W3). When predicting W2 and W3 inconsistency, inconsistency at W1 was included as a covariate. Participants who were missing data on any of the baseline predictors (n = 15 in Middle School sample, n = 84 in College sample) were excluded from these regression analyses.

Middle School Sample: Cross-Sectional Analysis

Results for the Middle School sample are shown in Table 4. At Wave 1, inconsistent responding was negatively associated with age and positively associated with non-White race/ethnicity. Sensation seeking was negatively associated with inconsistent responding at W1, and was the only personality/temperament variable that was significantly related with W1 inconsistency. Some of the protective and risk factors also were significant predictors of W1 inconsistency. As expected, inconsistent responding was negatively associated with parental monitoring and school engagement and positively associated with delinquency. Also, alcohol use was positively associated with inconsistent responding.

Table 4.

Summary of Multiple Regression Models Predicting Inconsistency for the Middle School Sample.

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | |

| Wave 1 inconsistency | — | — | 20 (.03)*** | .21 | .20 (.03)*** | .21 |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age | −.02 (.01)** | −.08 | .01 (.01) | .02 | −.00 (.01) | −.00 |

| Female | .00 (.02) | .00 | .01 (.02) | .02 | −.00 (.02) | −.00 |

| Non-White | .07 (.02)** | .09 | .03 (.02) | .03 | .05 (.02) | .07 |

| Personality | ||||||

| UPPS: Positive Urgency | .03 (.02) | .08 | −.01 (.02) | −.01 | .03 (.02) | .08 |

| UPPS: Negative Urgency | −.02 (.02) | −.06 | −.00 (.02) | −.00 | −.03 (.02) | −.09 |

| UPPS: Sensation Seeking | −.04 (.01)** | −.11 | −.02 (.01) | −.05 | −.03 (.01)* | −.08 |

| Substance use | ||||||

| Ever full drink | .09 (.03)** | .08 | −.00 (.04) | −.00 | .07 (.04) | .07 |

| Protective factors | ||||||

| Parental monitoring | −.04 (.01)*** | −.13 | −.02 (.02) | −.07 | −.04 (.01)*** | −.13 |

| School engagement | −.07 (.02)*** | −.14 | −.04 (.02) | −.07 | −.02 (.02) | −.05 |

| Contributing/risk factors | ||||||

| MASC: Social anxiety | .00 (.00) | .07 | −.00 (.00) | −.02 | −.00 (.00) | −.06 |

| Stress | −.01 (.02) | −.02 | .02 (.02) | .03 | .02 (.02) | .04 |

| PBFS: Delinquency | .02 (.00)*** | .17 | .01 (.00)* | .09 | −.01 (.01) | −.05 |

| Model statistics | ||||||

| F (dfs) | 17.08 (12,995)*** | 9.00 (13, 905)*** | 9.13 (13, 861)** | |||

| Adjusted R2 | .16 | .10 | .11 | |||

Note. UPPS = Urgency, Premeditation, Perseverance, and Sensation seeking; MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; PBFS = Problem Behavior Frequency scale.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p < .001.

Middle School Sample: Prospective Analysis

Although related to W1 inconsistency, age, race/ethnicity, alcohol use, and school engagement were not prospectively associated with W2 or W3 inconsistency after accounting for W1 inconsistency. Sensation seeking was not significantly associated with W2 inconsistency, but was negatively associated with W3 inconsistency. The association between W1 delinquency and inconsistent responding remained strong when predicting W2 inconsistency; however, this association was no longer significant for W3 inconsistency.

College sample: Cross-sectional Analysis

As shown in Table 5, non-White race/ethnicity was a unique predictor of inconsistent responding at W1. Among the personality variables, neuroticism was a unique predictor of greater inconsistency at W1. Also, agreeableness was negatively associated with inconsistency at W1. Contrary to hypotheses, conscientiousness was not uniquely associated with inconsistent responding. Although the substance use variables showed some positive bivariate associations with inconsistency (see Table 3), no significant associations with W1 inconsistency were observed after accounting for demographics and personality.

Table 5.

Summary of Multiple Regression Models Predicting Inconsistency for the College Sample.

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | B (SE) | β | ||||

| Wave 1 inconsistency | — | — | .17 (.04)** | .17 | .17 (.04)** | .16 | |||

| Demographics | |||||||||

| Female | −.01 (.02) | −.01 | .01 (.02) | .02 | .04 (.02) | .06 | |||

| Non-White | .06 (.02)** | .11 | .04 (.02) | .07 | .04 (.02) | .07 | |||

| Personality | |||||||||

| Extraversion | .02 (.01) | .05 | .01 (.01) | .01 | .01 (.01) | .01 | |||

| Agreeableness | −.04 (.02)** | −.10 | −.02 (.02) | −.04 | −.04 (.02)* | −.09 | |||

| Conscientiousness | −.01 (.01) | −.01 | .01 (.01) | .02 | −.01 (.02) | −.01 | |||

| Neuroticism | .06 (.01)** | .19 | .04 (.01)** | .13 | .04 (.01)** | .12 | |||

| Openness | .01 (.01) | .03 | .04 (.02)** | .10 | .04 (.02)* | .09 | |||

| Substance Use | |||||||||

| Alcohol Use | .01 (.01) | −.01 | −.01 (.01) | −.08 | .01 (.01) | .01 | |||

| Drug Use | .01 (.05) | .01 | .07 (.06) | .06 | .02 (.06) | .02 | |||

| Alcohol consequences | .01 (.01) | .03 | .01 (.01)* | .12 | .01 (.01) | .01 | |||

| Drug Consequences | .01 (.01) | .06 | −.01 (.01) | −.07 | −.01 (.01) | −.01 | |||

| Model statistics | |||||||||

| F (dfs) | 6.59 (11, 909)** | 6.47 (12, 793)** | 6.80 (12, 832)** | ||||||

| Adjusted R2 | .06 | .08 | .08 | ||||||

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

College Sample: Prospective Analysis

Consistent with the Middle School sample, race/ethnicity was not a significant predictor of W2 and W3 inconsistent responding after controlling for inconsistency at W1. Although gender was correlated with W2 and W3 inconsistency in bivariate analyses, gender did not predict unique variance in inconsistent responding in the multivariate analyses. Neuroticism remained a significant predictor of inconsistency, with W1 neuroticism predicting unique variance in W2 and W3 inconsistent responding above and beyond W1 inconsistent responding. Also, neuroticism likely accounted for the bivariate association between gender and inconsistency as females were significantly higher on neuroticism, r = .28, p < .001. Agreeableness at W1 was not a prospective predictor of W2 inconsistency but was a significant predictor of W3 inconsistency. Although not significantly associated with W1 inconsistency, Openness to Experience at W1 emerged as a significant prospective predictor of inconsistency at W2 and W3. However, alcohol and drug use and consequences contributed little to the prospective prediction of inconsistency.

Discussion

Web-based assessment is increasingly common in psychological research and is extremely useful for longitudinal studies of substance use. Though several studies have documented the extent to which online assessments correspond to other more traditional methods (Gosling et al., 2004; E. T. Miller et al., 2002; Read, Farrow, Jaanimagi, & Ouimette, 2009), there has been less research on participant response styles in web-based survey research and whether these may affect data quality. The present study sheds light on the extent of inconsistent responding in these types of studies and provides a practical strategy for conducting an ad hoc inconsistency analysis that can help to identify and predict inconsistent response patterns.

An important finding of this study is that, on average, participants in our samples showed only modest inconsistency in their responses to similar items on web-based surveys. Across the three waves in Middle School and College samples, the large majority of participants had inconsistency scores that were at or below 25% of the maximum possible inconsistency score. This is roughly equivalent to a one-point difference between responses to two items that are scored on a 5-point scale. However, the distributions of the descriptive inconsistency indices revealed that a modest amount of inconsistency was typical. That is, very few participants showed a complete absence of inconsistency by providing identical responses on all seven item pairs. Importantly, though, given that the items in each pair were not exact duplicates of one another (e.g., “distressed” and “upset” are highly similar items but not identical), some minor differences in responses to the items in each pair might be expected even from very attentive and motivated participants. Thus, the modest degree of inconsistency we observed does not necessarily reflect carelessness or inattention.

We also found that inconsistency was somewhat higher in the College sample than in the Middle School sample. Perhaps this was a result of different environmental influences (e.g., a college dorm may be more distracting than the family home of a young adolescent) or different motivational influences (e.g., a college student may be busier with school assignments or less concerned about providing accurate responses to a research team than a middle school student). However, because the inconsistency indices for Middle School and College samples consisted of item pairs that differed in content, we must use caution in drawing direct comparisons between the two samples in terms of the absolute level of observed inconsistency. That is, the difference between the samples could reflect differences in the assessment of inconsistency rather than differences in participants’ propensity toward inconsistent responding. Still, despite some differences between the samples, our analysis led to the same general conclusions for both samples—that the amount of inconsistency in responding was generally modest.

Thus, although it is a common concern that online surveys may promote haphazard or careless responding (Meade & Craig, 2012), our descriptive analyses of inconsistent responding do not lend support to these concerns. This is consistent with the results of Johnson (2005), who found a low rate of inconsistent responding in a large sample of participants completing an online personality survey. Moreover, our findings converge with the results of studies using other survey administration modalities (i.e., paper-and-pencil) that also have found a high degree of consistency in participants’ responses to survey items (Kurtz & Parish, 2001; Wu & Newfield, 2007). However, as Meade and Craig (2012) have noted, estimates of the prevalence of inconsistent responding have varied widely across studies—even when comparing studies that used the same modality of administration—depending on the method used for calculating and quantifying inconsistency. Thus, we must use caution in comparing the results of our study with studies that have used other types of inconsistency indices.

In addition, this study helped to identify participant characteristics that may be associated with inconsistent responding. First, we predicted that inconsistent responding would be stable over time, such that participants who were elevated on inconsistency indices at one time point would continue to be inconsistent responders at subsequent time points. We found some support for this hypothesis, as inconsistency scores were significantly correlated over time in both samples. However, these correlations were small (typically less than .30). So, although inconsistent responding in our study showed some stability over time, inconsistent responders on one assessment were not always inconsistent on the following assessment. Moreover, although we expected that inconsistent responding might increase over time as a function of increasing boredom or reactivity to repeated assessments, we found that average inconsistency scores in both samples tended to decrease slightly over time. This may be a function of higher levels of attrition among participants with higher inconsistency scores at Wave 1 but could also be a reflection of the relatively long interval between assessments compared with studies that use daily or weekly assessments (which might lead to greater participant fatigue). Thus, research examining inconsistent responding in studies with more frequent assessments is needed to further clarify the effect of repeated assessments on inconsistent responding.

We also found that a number of individual-level characteristics measured at Wave 1 were associated with inconsistent responding. In terms of demographics, non-White race/ethnicity was consistently correlated with inconsistent responding across both the Middle School and College samples, as was female gender in the College sample. However, in the context of the multiple regressions, these correlations appeared to be largely accounted for by other variables in the model. For example, the bivariate association between gender and inconsistent responding in the College sample appears to have been accounted for by neuroticism. Non-White race/ethnicity was a significant, unique predictor only of Wave 1 inconsistency in both samples and did not prospectively predict inconsistent responding. Age at Wave 1 emerged as a significant predictor of Wave 1 inconsistency in the Middle School sample, with younger participants showing more inconsistency in responding, although this association was not observed over time. We had no hypotheses about the influence of demographic variables on inconsistent responding because there is little past research to speak to these associations. Thus, more research is necessary to determine the mechanisms that may account for the relationship between demographic variables and inconsistent responding to web-based surveys.

Personality variables also predicted inconsistency in our samples. Consistent with our hypotheses, neuroticism was a strong predictor of inconsistency in the College sample, both cross-sectionally and prospectively. High levels of neuroticism reflect the tendency to experience a range of negative emotions (John & Srivastava, 1999). Perhaps these negative emotions interfere with responding on survey items and increase risk for careless or otherwise incongruent response styles. Importantly, neuroticism measured at Wave 1 was prospectively associated with increased inconsistency scores at subsequent time points after controlling for Wave 1 inconsistency, suggesting that neuroticism may be a particularly useful trait for early identification of participants who are at risk for continued inconsistency. We also hypothesized that participants lower on conscientiousness would show greater inconsistency in responding because they may be less likely to pay careful attention to survey items. We found some support for this hypothesis in the bivariate analysis, with conscientiousness showing a significant negative correlation with Wave 1 and Wave 3 inconsistency scores in the College sample. However, in the multiple regression analyses, conscientiousness did not predict unique variance in inconsistent responding. It is important to note that lower conscientiousness was significantly correlated with higher agreeableness and lower neuroticism in this sample. Thus, it appears that the relationship between conscientiousness and inconsistent responding may have been accounted for by these other personality traits.

In the Middle School sample, we did not find support for our hypothesis that personality traits related to impulsivity would predict greater inconsistency in responding. We also observed an unexpected negative association between sensation seeking and inconsistency, such that students lower on sensation seeking tended to be more inconsistent. The reasons for these unexpected results are not clear, and point to the need for future research in this area to examine mechanisms linking personality characteristics with inconsistent responding.

Based on data showing that substance use and misuse are associated with cognitive and behavioral dysregulation (e.g., Aytaclar et al., 1999; Colder & Chassin, 1993; Giancola et al., 1998), we hypothesized that substance use and consequences would predict inconsistent response style. Though we did observe associations between inconsistency scores and alcohol use (Middle School sample) and drug and alcohol consequences (College sample) in bivariate analyses, these associations were largely accounted for by other variables in the context of the multiple regression analysis. This is an important finding, as web-based longitudinal studies are particularly useful in substance use research because they provide greater anonymity to participants who may be reluctant to report on illegal or socially undesirable substance use behavior. Our study supports the use of online methods to collect data from substance users, because substance use behaviors per se do not appear to elevate inconsistent response styles. However, as hypothesized, other behaviors that are typically associated with substance use and behavioral dysregulation in general (i.e., risk factors such as low parental monitoring, low school engagement, and delinquency) were unique predictors of inconsistent responding at Wave 1 in the Middle School sample. Thus, researchers using online methods to study substance use—especially among adolescents who display intermittent patterns of substance use—may wish to include measures of more general dysregulation, as these factors may be associated with both substance use and the tendency to respond inconsistently to survey items.

The results of this study have important practical implications for web-based research. We demonstrated that a relatively simple procedure could be applied to examine the extent of inconsistent responding to repeated online surveys and to predict which participants were more likely to provide inconsistent data. Moreover, applying the same procedure to data from two independent longitudinal studies of substance use yielded findings that were generally consistent across the studies. Given that the samples from these studies were at much different stages developmentally and that the items that comprised the inconsistency indices were different across the two studies, the convergence in our findings (in terms of the overall level of inconsistent responding and the predictors of inconsistent responding) lends support to the utility of this procedure as an ad hoc data integrity check. Furthermore, our findings provide some support to the validity of the inconsistency indices, as many of the personality and behavioral factors that we examined were related in predictable ways with inconsistent responding. Moreover, the procedures described in this study are particularly useful for longitudinal designs, as researchers could perform an inconsistency analysis after the first wave of data collection to identify participants who may provide unreliable data. Then, procedures could be implemented to encourage participants to attend more closely to survey items in subsequent assessments. One practical approach would be to calculate an inconsistency index and plot a frequency distribution (see Figure 1 for example), which could be used to identify participants with outlying values (i.e., with extreme scores that are disconnected from the rest of the distribution). With the ease of web-based data collection methods, this could be carried out on an ongoing basis.

There are some limitations to the present study that should be taken into consideration. First, although our results provide insight into the extent of inconsistent responding in the context of online longitudinal studies, we are not able to directly compare our findings with other data collection methods such as paper-and-pencil surveys. Indeed, many of the concerns that researchers may have regarding the validity of participant responses to online surveys (e.g., rushing through the survey, reactivity to repeated assessments) are not specific to Internet assessments and also occur when using traditional paper-and-pencil measures (see Meade & Craig, 2012). Still, given that longitudinal web-based studies are becoming increasingly common, and little is currently known about participant response styles in the context of such studies, the present study provides a useful examination into the extent of inconsistent responding within this specific research modality. As an important next step, future studies should use multiple methods of data collection so that direct comparisons can be made regarding inconsistent responding across methods.

In addition, the inconsistency indices used here measure only one dimension of responding that might be of concern to researchers. Participants could provide poor data in other ways, such as responding to long strings of items with the same answer (e.g., answering every item on a measure with a “3”) or skipping groups of items (Johnson, 2005), which would go undetected by the inconsistency analyses. Thus, no single dimension of participant responding should be taken as an absolute index of data quality, and researchers conducting online longitudinal studies of substance use should work toward adopting more comprehensive approaches to assessing the validity of participant responses.

It also is important to note that the item pairs that comprised the inconsistency indices in this study were not made up of identical items with respect to content (e.g., “upset” has a slightly different meaning than “distressed”). Thus, discrepancies in responses to the items in each pair could reflect an inconsistent or careless response style, or they could reflect real differences in the slightly different constructs that are assessed by the items. Moreover, even when a participant obtains a high score on the inconsistency index that is likely because of inconsistent responding to the items, there could be multiple reasons for this inconsistency including careless or haphazard responding, true cognitive/emotional dysregulation, or cultural/language influences on item interpretation.

Furthermore, the prediction of inconsistency scores from self-reported personality and behavioral variables is limited by potential shared method variance. That is, we used self-report data to predict inconsistent responding to self-report questionnaires. The validity of the inconsistency indices would be bolstered by gathering additional data from informants or behavioral observations. Also, the effect sizes for our prediction of inconsistency were fairly small, and our regression models accounted for only 6% to 18% of the variance in inconsistency scores. Thus, there are other relevant variables for predicting inconsistency that were not included in these studies.

A strength of the present study is that we included two independent samples at different developmental stages. Still, more research is needed to determine whether these results generalize to other populations or other research designs. In particular, concerns about inconsistency related to substance use may be more relevant in a sample of more severely dependent participants. Similarly, concerns about participant reactivity to repeated assessments may be especially relevant in daily diary studies in which assessments are much more frequent. Also, in the Middle School sample, participants completed the Wave 1 survey in a supervised group format but completed the Wave 2 and Wave 3 surveys on their own. Although we did not observe notable differences in inconsistency scores over time, we acknowledge that the change in assessment setting limits the conclusions that can be drawn regarding the effect of repeated assessments on inconsistency over time. A related issue is that several predictors, including higher scores on Wave 1 inconsistency, predicted attrition from the studies. Although our retention rates were fairly high across both studies, our prospective prediction of inconsistency scores is limited to the extent that the findings cannot be generalized to inconsistent responders who dropped out. That inconsistency scores at Wave 1 were associated with failure to complete one or both of the follow-up assessments is in itself an interesting finding, as this suggests that inconsistent responding may be an important indicator of lower participant commitment to the study.

In summary, this study presents a useful approach to conducting ad hoc analyses of inconsistent responding in web-based survey data. Using data from two longitudinal studies of substance use, we found that adolescent and young adult participants generally showed modest to moderate levels of inconsistency in their responses to items. Moreover, inconsistency in responding was predicted cross-sectionally and longitudinally from several demographic, personality, and behavioral variables. The findings have implications for researchers who wish to benefit from the convenience and efficiency of web-based assessment by providing evidence that participants tend not to be extremely careless when responding to online surveys. This study highlights the potential utility of ad hoc procedures for identifying participants who respond inconsistently in longitudinal studies so that targeted efforts can be made to encourage these participants to pay more careful attention to survey items.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by Grant R01AA016838 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism awarded to Kristina M. Jackson and by Grant R01DA018993 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse awarded to Jennifer P. Read.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Aunola K, Stattin H, Nurmi J-E. Adolescents’ achievement strategies, school adjustment, and externalizing and internalizing problem behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29:289–306. [Google Scholar]

- Aytaclar S, Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Lu S. Association between hyperactivity and executive cognitive functioning in childhood and substance use in early adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:172–178. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199902000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM. Monitoring the future: Questionnaire responses from the nation’s high school seniors, 2004. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes GM, Hoffman JH, Welte JW, Farrell MP, Dintcheff BA. Effects of parental monitoring and peer deviance on substance use and delinquency. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:1084–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL) Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:669–673. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo JK, Gilchrist LD, Elmer JF, Snow WH, Schinke SP. Hassles, role strain, and peer relations in young adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1986;6:339–352. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant AL, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. How academic achievement, attitudes, and behaviors relate to the course of substance use during adolescence: A 6-year, multiwave national longitudinal study. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2003;13:361–397. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan T, Johnson JA, Goldberg LR. Implementing a five-factor personality inventory for use on the internet. European Journal of Psychological Assessment. 2005;21:115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Butcher J, Dahlstrom W, Graham J, Tellegen A, Kaemmer B. Manual for administration and scoring: MMPI-2. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Todd M, Rose JS, Sherman SJ. Maternal socialization of adolescent smoking: The intergenerational transmission of parenting and smoking. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1189–1201. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Chassin L. The stress and negative affect model of adolescent alcohol use and the moderating effects of behavioral undercontrol. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 1993;54:326–333. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Danish SJ, Howard CW. Relationship between drug use and other problem behaviors in urban adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:705–712. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Mezzich AC, Tarter RE. Disruptive, delinquent and aggressive behavior in female adolescents with a psychoactive substance use disorder: Relation to executive cognitive functioning. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 1998;59:560–567. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosling SD, Vazire S, Srivastava S, John OP. Should we trust web-based studies? A comparative analysis of six preconceptions about internet questionnaires. American Psychologist. 2004;59:93–104. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JL, Curran PG, Keeney J, Poposki EM, DeShon RP. Detecting and deterring insufficient effort responding to surveys. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2012;27:99–114. [Google Scholar]

- John OP, Srivastava S. The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In: Pervin LA, John OP, editors. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 102–138. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JA. Ascertaining the validity of individual protocols from web-based personality inventories. Journal of Research in Personality. 2005;39:103–129. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2011. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Stattin H. What parents know, how they know it, several forms of adolescent adjustment: Further support for a reinterpretation of monitoring. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:366–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz JE, Parrish CL. Semantic response consistency and protocol validity in structured personality assessment: The case of the NEO-PI-R. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2001;76:315–332. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7602_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent J, Catanzaro SJ, Joiner TE, Jr, Rudolph KD, Potter KI, Lambert S, Gathright T. A measure of positive and negative affect for children: Scale development and preliminary validation. Psychological Assessment. 1999;11:326–338. [Google Scholar]

- Link MW, Mokdad AH. Effects of survey mode on self-reports of adult alcohol consumption: A comparison of mail, web and telephone approaches. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2005;66:239–245. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam D, Smith G, Whiteside S, Cyders M. The UPPS-P: Assessing five personality pathways to impulsive behavior. 2006 (Technical Report). Retrieved from http://www1.psych.purdue.edu/~dlynam/uppspage.htm. [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Parker JD, Sullivan K, Stallings P, Conners CK. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:554–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath RE, Mitchell M, Kim BH, Hough L. Evidence for response bias as a source of error variance in applied assessment. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:450–470. doi: 10.1037/a0019216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade AW, Craig SB. Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychological Methods. 2012;17:437–455. doi: 10.1037/a0028085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller ET, Neal DJ, Roberts LJ, Baer JS, Cressler SO, Metrik J, Marlatt GA. Test-retest reliability of alcohol measures: Is there a difference between Internetbased assessment and traditional methods? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16:56–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller PG, Sonderlund AL. Using the internet to research hidden populations of illicit drug users: A review. Addiction. 2010;105:1557–1567. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesselroade JR, Baltes PB. Longitudinal research in the study of behavior and development. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. Demographics of teen Internet users. 2013 Feb 14; Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/Static-Pages/Trend-Data-(Teens)/Whos-Online.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Rainie L. Changes to the way we identify internet users. 2012 Feb 14; Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Counting-internet-users/Counting-internet-users.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Colder CR, Merrill JE, Ouimette P, White J, Swartout A. Trauma and posttraumatic stress symptoms influence alcohol and other drug problem trajectories in the first year of college. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:426–439. doi: 10.1037/a0028210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Farrow SM, Jaanimagi U, Ouimette P. Assessing trauma and traumatic stress via the Internet: Measurement equivalence and participant reactions. Traumatology. 2009;15(1):94–102. [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Colder CR. Development and preliminary validation of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:169–177. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reips U-D. The web experiment method: Advantages, disadvantages, and solutions. In: Birnbaum MH, editor. Psychological experiments on the Internet. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 89–117. [Google Scholar]

- Saitz R, Helmuth ED, Aromaa SE, Guard A, Belanger M, Rosenbloom DL. Web-based screening and brief intervention for the spectrum of alcohol problems. Preventive Medicine. 2004;39:969–975. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schell TL, Martino SC, Ellickson PL, Collins RL, McCaffrey D. Measuring developmental changes in alcohol expectancies. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:217–220. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinka JA, Kinder BN, Kremer T. Research validity scales for the NEO-PI-R: Development and initial validation. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1997;68:127–138. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6801_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt WC. World-wide web survey research: Benefits, potential problems, and solutions. Behavior Research Methods. 1997;29:274–279. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Rutledge PC. Heavy drinking across the transition to college: Predicting first-semester heavy drinking from precollege variables. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:819–835. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, violence: Increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright DL, Aquilino WS, Supple AJ. A comparison of computer-assisted and paper-and-pencil self-administered questionnaires in a survey on smoking, alcohol, and drug use. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1998;62:331–353. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Newfield SA. Comparing data collected by computerized and written surveys for adolescent health research. Journal of School Health. 2007;77:23–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]