Abstract

Loss of coral reef resilience can lead to dramatic changes in benthic structure, often called regime shifts, which significantly alter ecosystem processes and functioning. In the face of global change and increasing direct human impacts, there is an urgent need to anticipate and prevent undesirable regime shifts and, conversely, to reverse shifts in already degraded reef systems. Such challenges require a better understanding of the human and natural drivers that support or undermine different reef regimes. The Hawaiian archipelago extends across a wide gradient of natural and anthropogenic conditions and provides us a unique opportunity to investigate the relationships between multiple reef regimes, their dynamics and potential drivers. We applied a combination of exploratory ordination methods and inferential statistics to one of the most comprehensive coral reef datasets available in order to detect, visualize and define potential multiple ecosystem regimes. This study demonstrates the existence of three distinct reef regimes dominated by hard corals, turf algae or macroalgae. Results from boosted regression trees show nonlinear patterns among predictors that help to explain the occurrence of these regimes, and highlight herbivore biomass as the key driver in addition to effluent, latitude and depth.

Keywords: boosted regression trees, coral reefs, disturbance, Hawai‘i, multiple regimes, resilience

1. Introduction

The dramatic loss of live coral cover on reefs worldwide [1–3] has raised serious concerns regarding their future [4,5]. Parallel to this loss, observational [6–8], experimental [9,10] and modelling [11] studies suggest that many coral reefs are shifting to alternative regimes (or states) with consequences for coastal societies that depend on reef resources. While transitions from coral to macroalgae dominance are most commonly described [6,7], other degraded states, characterized by sponge, soft coral or corallimorpharian dominance, have been suggested [12].

Regime shifts in coral reefs have primarily been described in human-dominated environments [13,14] where overfishing and reduced water quality, acting in concert with climate change, have been suggested as key drivers [10,15]. Specifically, the loss of herbivores, which keep algal colonization and growth in check, has been argued to be a leading cause of regime shifts [2,7], particularly when large tracts of substratum become open for rapidly colonizing algae, e.g. following hurricanes or coral mass bleaching events [10,16,17].

Yet, recent meta-analyses of longitudinal datasets have questioned the existence (or the stability) and the generality of alternative reef regimes in coral reefs. For example, Bruno et al. [18] looked for multimodal patterns in the frequency distribution of benthic cover in 1851 reefs worldwide, and reported that most reefs were in neither a coral-dominated state (more than 50% coral cover) nor a macroalgae-dominated state (more than 50% macroalgal cover), challenging the assumption that coral–macroalgae shifts are a common phenomenon. Similarly, using stochastic semi-parametric modelling on reef data from the Caribbean, Kenya and Great Barrier Reef, Żychaluk et al. [19] found no evidence of bimodality at a regional scale. However, Mumby et al. [20] argued that both studies make a number of unrealistic statistical assumptions with regards to the constancy of environmental variables, resolution of field data and disturbance dynamics. Similarly, Hughes et al. [14] claimed that data used are often too patchy and unable to identify the complex mechanisms or processes causing long-term change. Moreover, they contested the cut-off set by Bruno et al. [18] (i.e. more than 50% cover), arguing that few reefs globally display such abundances of dominating benthic taxa.

Diagnosing multiple regimes from field data is problematic, because coral reefs may respond slowly to frequent pulse perturbations [20] that mask trends of recovery or decline. Given the critical consequences of regime shifts on ecosystem services [5,21] and their profound management implications, we need a better understanding of the processes that drive alternative reef regimes, and improved methods to extract evidence of their existence from field data.

Here, relying on an extensive spatial dataset gathered in the Hawaiian archipelago across gradients of natural and anthropogenic conditions, we apply a novel approach for detecting, visualizing and defining potential multiple ecosystem regimes. We also identify the primary human and natural drivers that help to explain these regimes across a regional scale.

2. Material and methods

(a). Study area

The Hawaiian archipelago (Hawai‘i, USA) is one of the most isolated archipelagos in the world (figure 1). While the heavily populated Main Hawaiian Islands (MHI) are overfished [22] and subjected to a range of anthropogenic stressors [23], the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI) receive minimal direct human impacts and are among the most protected coral reefs globally [24].

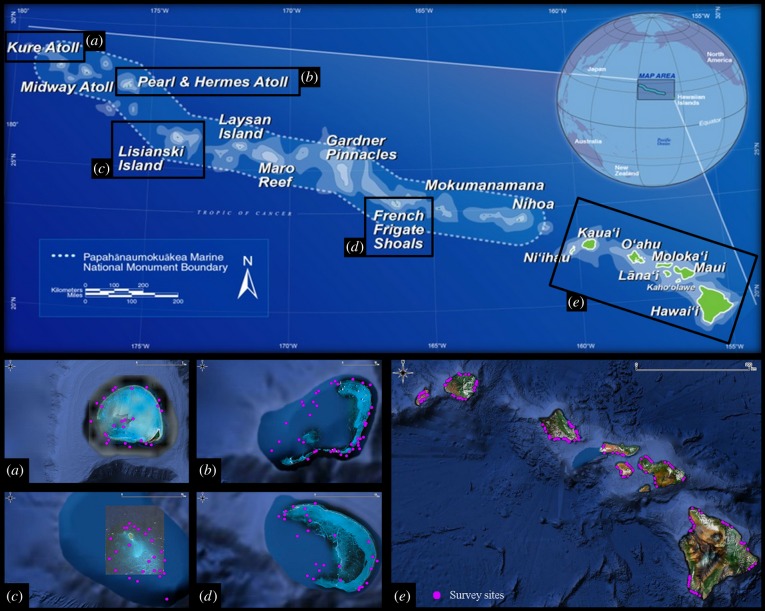

Figure 1.

Map of the study area showing the Hawaiian archipelago (courtesy of NOAA) and the location of the survey sites (purple dots). Within the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (a–d) 118 sites were surveyed, and 184 within the main Hawaiian Islands (e).

(b). Organization of data

Benthic and fish data were collected in 2010 from 302 reef sites across the Hawaiian archipelago by the Coral Reef Ecosystem Division, as part of NOAA's Pacific Reef Assessment and Monitoring Programme. (For sampling methodology, see the electronic supplementary material, S1.)

Fish species were categorized into functional groups based on their trophic level (see the electronic supplementary material, S2), and herbivores were further divided into grazers, scrapers and browsers [25]. Grazers are fish that crop on algal turf, preventing the establishment and growth of macroalgae. Scrapers also feed on turf but they remove some component of the reef substratum, which provides bare areas for coral recruitment. Finally, browsers consistently feed on macroalgae and may play a crucial role for reversing macroalgae-dominated states [5,26]. Dietary information was collected from FishBase [27] and complemented from the literature [25] when higher-resolution data were required for herbivore classification. In cases where fish could be identified only to genus level, information on the diet of close relatives from the same genus was used. Total biomass per functional group was calculated from the biomass of individual fish obtained using the formula

where W is the weight in grams, TL the total length in millimetres, and a and b species-specific conversion parameters extracted from FishBase [27].

In addition to benthic and fish data, a set of human-use and environmental GIS (Geographic Information Systems)-derived variables—human population density, distance to potential impact (e.g. shore, stream), effluent discharge and stream disturbance data (composite metrics of many land cover variables) [28]—was compiled for the Main Hawaiian Islands except for Lāna‘i and Ni‘ihau.

(For methodology and detailed list of the variables, see the electronic supplementary material, S3.)

(c). Data analyses

All statistical analyses and graphical presentations were conducted using R v. 2.15.1 [29]. Specific packages used are referred to in the text or in the figure legends.

(i). Identification of reef regimes and categorization of sites

First, we replicated the method applied by Bruno et al. [18] to create a phase shift index (PSI) and graphically check for multimodality in the frequency distribution of benthic states. In essence, the PSI is the first component of a principal component analysis (PCA) based on the cover of coral and macroalgae.

Second, a correlation-based PCA was performed using six benthic habitat variables: hard coral cover (Hcoral), macroalgae cover (MA), turf algae cover (TA), structural complexity estimate (complexity), sand cover on the reef surface (sand) and crustose coralline algae cover (CCA). Structural complexity was included because it is a key aspect of reef habitat quality [30], and data were standardized to account for variables measured at different scales. A hierarchical clustering of the variables was produced with the same Euclidean distance matrix as for the PCA using pvclust package v. 1.2-2 [31], and p-values computed by 10 000 multi-scale bootstrap resampling [32] were assigned to each cluster to indicate how strongly the cluster was supported by the data. A cluster was considered to be significant when the approximately unbiased p-value was greater than 0.95. Finally, building on the number of significant clusters obtained through the previous hierarchical analysis, a K-means partitional clustering process [33] was carried out to categorize the 302 sites with regards to their benthic habitat.

(ii). Relative influence of natural and human variables on reef regimes

To assess what key human and environmental variables were associated with different reef regimes, a boosted regression trees (BRTs) modelling technique [34] was performed using the gbm package v. 2.0-8 [35] and the gbm.step routine described by Elith et al. [36]. For the MHI (with the exception of Lāna‘i and Ni‘ihau), 147 sites were modelled simultaneously against 15 predictor variables, whereas for the NWHI, where human settings are absent, 118 sites were modelled against a set of seven continuous and categorical predictor variables (table 1). Pairwise relationships between all variables (no Spearman rank correlation coefficient was greater than |0.75|) showed no multicollinearity. The categorization of sites into different regimes was converted to presence–absence of each regime by survey site and analysed using a binomial distribution. Partial dependency plots were used to visualize and interpret the relationships between each predictor variable and the regime after accounting for the average effect of all other predictor variables in the model. (For BRT methodology and details on model optimization, see the electronic supplementary material, S4.)

Table 1.

Predictor variables used in the boosted regression trees analysis. MHI, main Hawaiian Islands; NWHI, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

| variable | description | range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MHI | GrazerBiom | grazer biomass in g m−2 | 0–28.3 |

| ScraperBiom | scraper biomass in g m−2 | 0–13.9 | |

| BrowserBiom | browser biomass in g m−2 | 0–22 | |

| latitude | latitude in decimal degrees (WGS 1984) | 18.97–22.24 | |

| depth | depth in metres | 2–29 | |

| DistCoast | distance in metres from nearest shoreline to survey location | 14–2509 | |

| DistStream | distance in metres from nearest stream to survey location | 96–20 130 | |

| effluent | the total effluent in million gallons per day (mgd) discharged within parcels that intersected with a 10 km buffer from survey location | 600–7 177 840 | |

| population | human population density in a 10 km buffer from survey location based on 2010 census data | 232–523 576 | |

| UrbanIndex | representation of urban disturbance standardized from 0 to 1 | 0–0.98 | |

| PointIndex | representation of the density of sources of point pollution standardized from 0 to 1 | 0–0.50 | |

| FragIndex | representation of stream fragmentation standardized from 0 to 1 | 0–0.31 | |

| FormplIndex | representation of lands that were formerly pineapple or sugarcane plantations standardized from 0 to 1 | 0–0.54 | |

| DitchIndex | representation of the relative density of ditch infrastructure standardized from 0 to 1 | 0–0.73 | |

| AgrIndex | representation of agricultural disturbance standardized from 0 to 1 | 0–0.65 | |

| NWHI | GrazerBiom | grazer biomass in g m−2 | 0–29.6 |

| ScraperBiom | scraper biomass in g m−2 | 0–30.8 | |

| BrowserBiom | browser biomass in g m−2 | 0–146.4 | |

| LPredBiom | large predator biomass in g m−2 | 0–2961.8 | |

| latitude | latitude in decimal degrees (WGS 1984) | 23.63–28.45 | |

| depth | depth in metres | 1–28 | |

| ReefZone | zones of the reef: fore reef—back reef—lagoon | n.a. |

3. Results

(a). Identification of reef regimes and categorization of sites

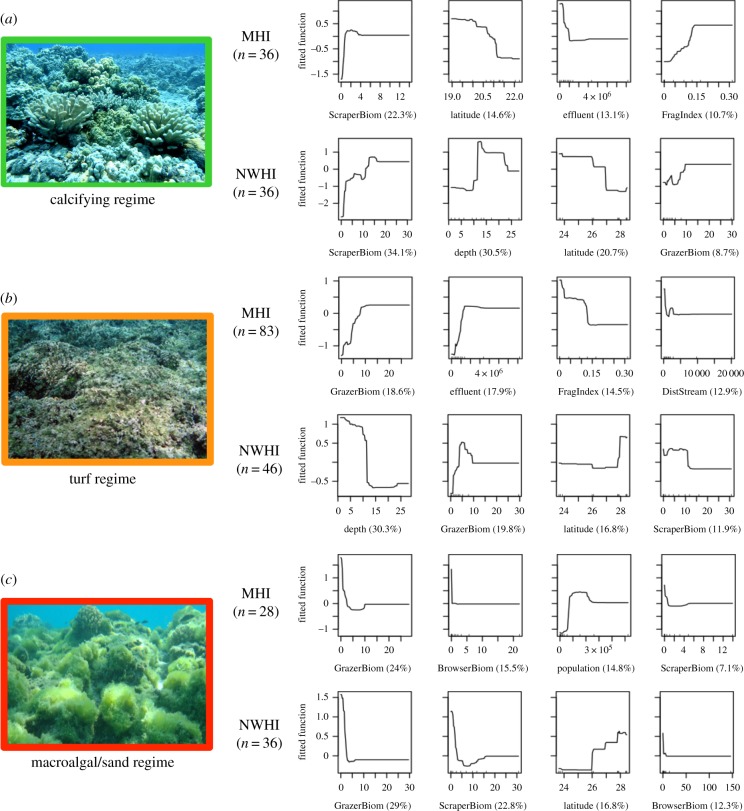

The test for multimodality in the frequency distribution of living coral and macroalgae of the 302 Hawaiian sites (figure 2) displayed a normal distribution which is similar to the findings by Bruno et al. [18], i.e. an absence of multiple regimes. By contrast, the combination of analytical approaches used in this paper highlighted the existence of three primary regimes. The results were identical for the MHI and the NWHI and, therefore, only the pattern for the archipelago as a whole is shown in figure 3.

Figure 2.

Count histogram of the phase shift index (PSI) [18] of 302 reef sites in the Hawaiian archipelago.

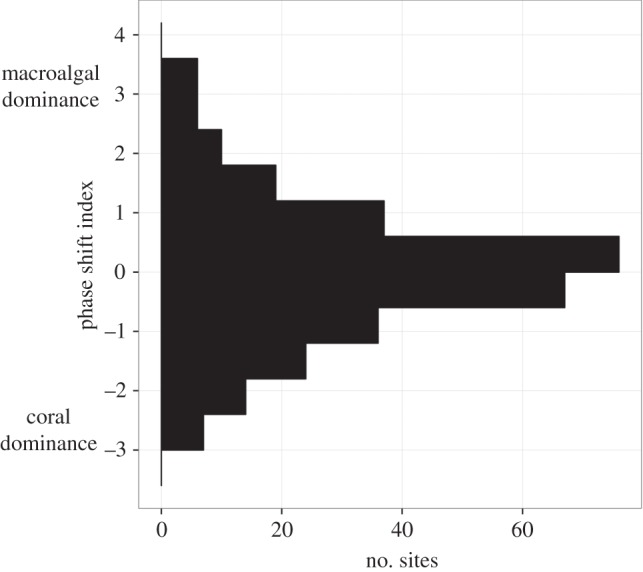

Figure 3.

(a) Principal component analysis (PCA) diagram showing the spatial variation in benthic habitat of 302 sites in the Hawaiian archipelago along the first two principal components. Variables are plotted as vectors and dots represent sites. The smaller the angle between two variable vectors the stronger the correlation. Hcoral, hard coral cover; MA, macroalgae cover; CCA, crustose coralline algae cover; TA, turf algae cover; sand, sand cover; complexity, structural complexity. (b) Cluster dendrogram of the benthic variables from 302 sites, with p-values given as percentages. For a cluster with p > 95%, the hypothesis that ‘the cluster does not exist’ is rejected with significance level 0.05. (c) PCA diagram with an overlaying K-means clustering of the sites. Green squares (80 sites), orange circles (153 sites) and red triangles (69 sites) represent categorization of the sites matching the previous hierarchical grouping of the benthic variables. The ellipses encompass 80% of the dots associated with each cluster.

The PCA using six benthic parameters showed a clear pattern of three distinct regimes. The first principal component axis (PC1) and the second principal component axis (PC2) accounted for 61.4% of the total variability in the data (figure 3a). PC1 described a gradient from high coral cover, high CCA cover and high structural complexity (at negative PC1 scores), to high macroalgae cover, high sand cover and low complexity (at positive PC1 scores). PC2 best explained the variability of turf algae with higher turf cover at negative PC2 scores.

The hierarchical cluster analysis (figure 3b) confirmed the visual impression from the PCA with the benthic variables grouping into three significant clusters: CCA being associated with hard coral and structural complexity (p = 1), turf algae being closer to macroalgae and sand but a cluster by itself since outside of any significant cluster (p = 0.79) and macroalgae being closely associated with sand (p = 0.99).

Finally, the K-means partitional clustering differentiated the sites along these three clusters with an overrepresentation of turf algae dominated sites (figure 3c): 153 sites (51%) were categorized as turf regime (sites dominated by turf algae), 80 sites (27%) as calcifying regime (high structural complexity sites dominated by CCA and hard coral) and 69 sites (23%) as macroalgal/sand regime (low structural complexity sites dominated by macroalgae and sand). (Mapping of the categorized sites per island and average values of the benthic variables within each regime is shown in the electronic supplementary material, S5.)

(b). Relative influence of human and natural variables on reef regimes

For each region, only the four most influential predictor variables were reported and illustrated (figure 4). Preliminary threshold values below are given only in cases where the shape of the fitted function best matches the distribution of the fitted values. (See the electronic supplementary material, S4 for the plots of the fitted values in relation to each predictor.)

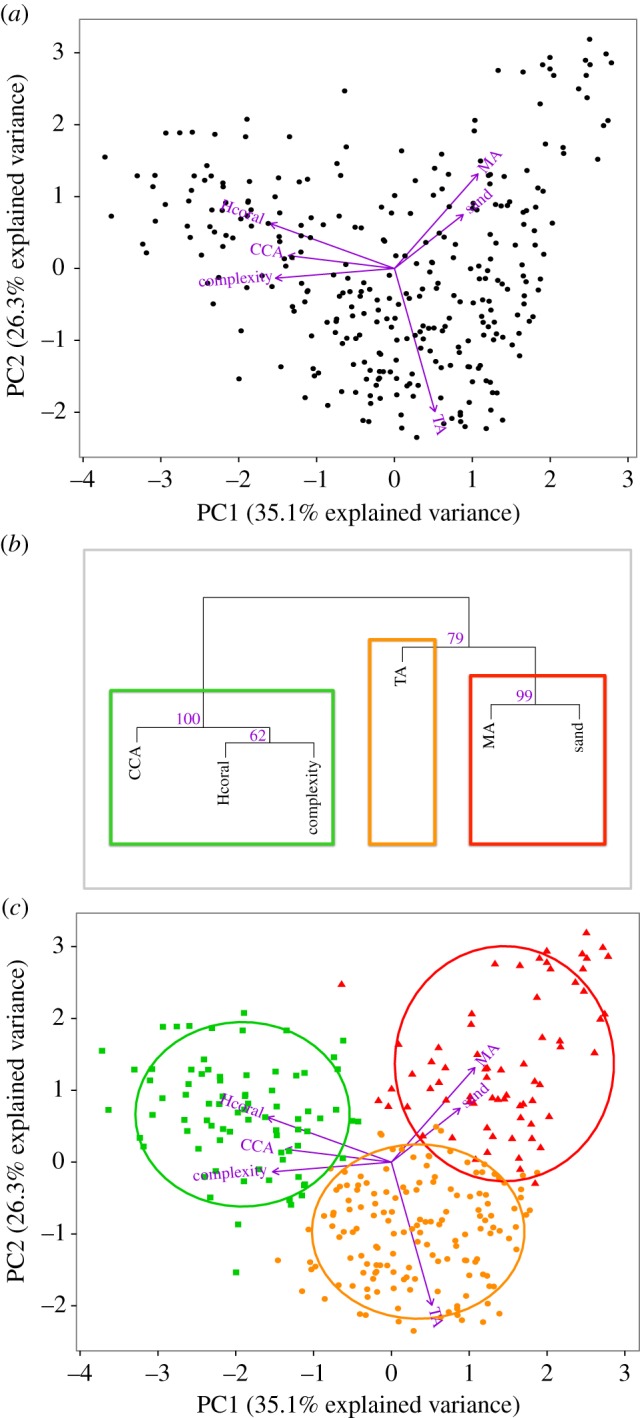

Figure 4.

Partial dependency plots for the four most influential variables in the boosted regression trees analysis of three distinct benthic regimes (a–c) in the MHI and the NWHI. Number of sites within each region and relative influence of each predictor are shown in parentheses. Photo credits: NOAA.

(i). Calcifying regime

In the MHI, a positive relationship with scraper biomass (22.3% relative influence) was the optimal predictor of the occurrence of structurally complex coral and CCA-dominated sites (figure 4a). Other important predictors were negative relationships with higher latitudes (14.6%) and increasing effluent (13.1%, drop around 1.0 × 106 million gallons per day (mgd)), and a positive correlation with stream fragmentation (10.7%).

In the NWHI, three variables contributed most strongly to predicting calcifying regime occurrence (figure 4a): scraper biomass (34.1%, positively correlated), depth (30.5%, peaked between 12 and 22 m) and latitude (20.7%, occurrence decreased at higher latitudes).

(ii). Turf regime

In the MHI, grazer biomass (18.6%) and effluent discharge (17.9%) were the two optimal predictors of turf algae occurrence, with positive nonlinear relationships for both predictors displaying thresholds around 10 g m−2 and 1.5 × 106 mgd, respectively (figure 4b). The opposite pattern (i.e. negative correlation) was observed for stream fragmentation (14.5%) and distance to stream (12.9%).

In the NWHI, depth (30.3%) contributed most to explain the occurrence of turf algae with a drop near 10 m (figure 4b). Grazer biomass (19.8%) and latitude (16.8%) were positively correlated, followed by a negative correlation with scraper biomass (11.9%).

(iii). Macroalgal/sand regime

In the MHI, three key predictor variables contributed to the occurrence of macroalgae-dominated sites (figure 4c). Macroalgal dominance displayed negative nonlinear relationships with increasing grazer (24%) and browser (15.5%) biomass. Thresholds seemed to occur around 5 and 2 g m−2, respectively. Human population density represented 14.8% of the relative influence and was positively correlated, whereas scraper biomass was negatively correlated (7.1%).

In the NWHI, herbivore biomass was again the main predictor (figure 4c): occurrence of macroalgal/sand sites decreased as the biomass of grazers (29%, drop at 5 g m−2), scrapers (22.8%, drop at 4 g m−2) and browsers (12.3%) increased. In addition, latitude (13.7%) was positively correlated.

4. Discussion

Identifying existing regimes and understanding their drivers has great relevance for managers, policy-makers and planners seeking to protect ecosystem services generated by coral reefs [5,37]. Based on a combination of exploratory and inferential statistics, this study provides a novel method to identify multiple regimes, and offers strong evidence of three distinct reef regimes occurring across the Hawaiian archipelago—calcifying, turf algae and macroalgal/sand regimes. It further suggests that simply testing for bimodality in the frequency distribution of present reef state [18] does not constitute a sufficient test of multiple regime existence. Our results also contribute to a deeper understanding of the relative influence of different drivers that underpin the occurrence of reef regimes, supporting the idea that they are multi-causal, driven by a combination of biotic processes, abiotic conditions and human drivers.

All three regimes occur both in the MHI and the NWHI, despite major differences in exposure to direct human impacts. This corroborates the findings of Vroom & Braun [38], who recorded high algal abundances in the NWHI and further stressed the necessity of re-evaluating the metrics used to gauge subtropical reef health. Our results also show that most reefs in this system are dominated by turf algae (51% of all sites). This raises the question whether turf-dominated reefs constitute a stable regime or an unstable transitional state that is moving towards a coral or macroalgal attractor [17]. It has been argued that turf eventually proceeds towards macroalgae dominance if herbivore density is low [39,40], but experimental studies suggest that turf can also constitute a stable regime in sediment-rich areas, because herbivory of epilithic algal turfs is suppressed under sediment-laden conditions [41–43].

In this study, the occurrence of all three regimes was strongly predicted, for both regions, by the biomass of herbivores, confirming the important role they play in coral reef dynamics and in mediating reef regime-shifts [2,44]. In addition, categorizing herbivores into finer-scale functional groups (i.e. grazers, scrapers and browsers) allows for a better understanding of what specific ecological functions are important in supporting different regimes. The occurrence of macroalgal/sand regimes showed a negative nonlinear relationship with the density of browsers that directly consume macroalgae, as well as with increasing biomass of grazers and scrapers that limit their growth. The calcifying regime was positively associated with the biomass of scrapers that provide area of clean substratum (feeding scars) for coral recruitment, whereas the turf regime was positively correlated with grazers that prevent the transition from turf to macroalgae through top-down control. This confirms numerous studies that show how higher herbivore abundances coincide with a lower cover of macroalgae on reefs [10,11]. However, our results further suggest that an increase in herbivore biomass could lead to different regime trajectories, depending on the functional make-up of the herbivorous assemblage. Specifically, if the herbivores are predominantly grazers, then the probability of turf dominance increases, while if scrapers are abundant (e.g. Chlorurus sordidus, Chlorurus perspicillatus and Scarus rubroviolaceus), then there is an increased chance of a reef shifting to a calcifying regime.

Human drivers also influenced the distribution of different regimes. Population density has been used as a coarse proxy for overall human influence on coral reefs [45]. However, in recent studies, the relationships between population density and reef states appear ambiguous [46,47]. This study suggests that population density is a relatively poor predictor of reef regimes across the Hawaiian archipelago, which is overwhelmed by the influence of more refined proxies, particularly those for land-based pollution and land-use change (such as effluent discharge or stream fragmentation). In the MHI, the total amount of effluent discharged had a strong positive impact on turf regime, whereas being negatively correlated with the calcifying regime. McClanahan et al. [48] showed that an increase in phosphorus stimulated growth of filamentous and turf algae but not the growth of macroalgae. Overall, there is ample literature about the negative effects of nutrient pollution on corals and how it can lead to excessive algae growth [49–51, but see 52], particularly in combination with loss of herbivory [53]. However, this negative impact on corals seemed countered by a positive correlation with fragmentation of streams. The rationale behind this unexpected positive effect of human-induced stream disturbance could be that higher fragmentation reduces the natural water flow, thus allowing more of the effluent to sink or to be deposited on the stream edges before reaching the reefs.

Finally, physical drivers also play a key role in coral reef regimes in this system. Unlike the turf and macroalgal/sand regimes, the calcifying regime was negatively correlated with latitude. Low temperatures have been shown to limit coral growth [54] and, considering the latitudes the Hawaiian archipelago encompasses, this is likely to have an influence on the results [55]. Depth was also an influential abiotic parameter, although mostly significant in the NWHI. This divergence in relative influence between both regions is not clear but could be the result of increased water turbidity that limits light gradients in the MHI because of sediments. In the NWHI, we found the occurrence of calcifying regimes to peak at mid-depths, similar to results from Williams et al. [56]. However, gradients in other oceanographic variables that are known to be important in structuring benthic communities have been identified across the region [55]. For example, additional data on sedimentation [57] or wave exposure [56,58,59] will help investigators develop a better understanding of these important physical processes in influencing reef regimes.

These analyses provide a promising approach for investigating multiple ecosystem regimes and the processes underpinning them, which could help guide effective management. However, because our study does not account for historic disturbance events (e.g. hurricanes, disease outbreaks, bleaching events), it only represents a snapshot in time (year 2010). Therefore, the stability (or at least the trajectory of development) of any specific reef regime remains unknown and needs to be further explored. From a management perspective, the identification of nonlinear patterns and preliminary thresholds among many predictor variables offers an interesting avenue for future studies to investigate more accurately the location of these tipping points, in order to provide tangible management targets for both proactive avoidance of potential regime shifts and restoration of degraded reefs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This paper draws on preliminary work from a Master's thesis by Jean-Baptiste Jouffray [60] . We thank Dana Infante and Bob Whittier for providing the original human dimensions data, and two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments helping to improve this paper.

Data accessibility

The dataset supporting this article has been made available and uploaded in Dryad (doi:10.5061/dryad.rg832).

Funding statement

This work was partly funded by the Erling-Persson Family Foundation through Global Economic Dynamics and the Biosphere at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. Mistra supported this research through a core grant to the Stockholm Resilience Centre.

References

- 1.Gardner TA, Côté IM, Gill JA, Grant A, Watkinson AR. 2003. Long-term region-wide declines in Caribbean corals. Science 301, 958–960. ( 10.1126/science.1086050) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellwood DR, Hughes TP, Folke C, Nyström M. 2004. Confronting the coral reef crisis. Nature 429, 827–833. ( 10.1038/nature02691) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruno JF, Selig ER. 2007. Regional decline of coral cover in the Indo-Pacific: timing, extent, and subregional comparisons. PLoS ONE 2, e711 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0000711) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pandolfi JM, et al. 2005. Are U.S. coral reefs on the slippery slope to slime. Science 307, 1725–1726. ( 10.1126/science.1104258) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham NA, Bellwood DR, Cinner JE, Hughes TP, Norström AV, Nyström M. 2013. Managing resilience to reverse phase shifts in coral reefs. Front. Ecol. Environ. 11, 541–548. ( 10.1890/120305) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Done TJ. 1992. Phase shifts in coral reef communities and their ecological significance. Hydrobiologia 247, 121–132. ( 10.1007/BF00008211) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hughes TP. 1994. Catastrophes, phase shifts, and large-scale degradation of a Caribbean coral reef. Science 265, 1547–1551. ( 10.1126/science.265.5178.1547) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chong-Seng KM, Mannering TD, Pratchett MS, Bellwood DR, Graham NAJ. 2012. The influence of coral reef benthic condition on associated fish assemblages. PLoS ONE 7, e42167 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0042167) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hay ME. 1984. Patterns of fish and urchin grazing on Caribbean coral reefs: are previous results typical? Ecology 65, 446–454. ( 10.2307/1941407) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes TP, et al. 2007. Phase shifts, herbivory, and the resilience of coral reefs to climate change. Curr. Biol. 17, 360–365. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.049) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mumby PJ, et al. 2006. Fishing, trophic cascades, and the process of grazing on coral reefs. Science 311, 98–101. ( 10.1126/science.1121129) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norström A, Nyström M, Lokrantz J, Folke C. 2009. Alternative states on coral reefs: beyond coral–macroalgal phase shifts. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 376, 295–306. ( 10.3354/meps07815) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nyström M, Folke C, Moberg F. 2000. Coral reef disturbance and resilience in a human-dominated environment. Trends Ecol. Evol. 15, 413–417. ( 10.1016/S0169-5347(00)01948-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hughes TP, Graham NAJ, Jackson JBC, Mumby PJ, Steneck RS. 2010. Rising to the challenge of sustaining coral reef resilience. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 633–642. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2010.07.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ateweberhan M, McClanahan TR, Graham NAJ, Sheppard CRC. 2011. Episodic heterogeneous decline and recovery of coral cover in the Indian Ocean. Coral Reefs 30, 739–752. ( 10.1007/s00338-011-0775-x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams ID, Polunin NVC, Hendrick VJ. 2001. Limits to grazing by herbivorous fishes and the impact of low coral cover on macroalgal abundance on a coral reef in Belize. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 222, 187–196. ( 10.3354/meps222187) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mumby PJ, Hastings A, Edwards HJ. 2007. Thresholds and the resilience of Caribbean coral reefs. Nature 450, 98–101. ( 10.1038/nature06252) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruno JF, Sweatman H, Precht WF, Selig ER, Schutte GW, Hill C, Carolina N. 2009. Assessing evidence of phase shifts from coral to macroalgal dominance on coral reefs. Ecology 90, 1478–1484. ( 10.1890/08-1781.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Żychaluk K, Bruno JF, Clancy D, McClanahan TR, Spencer M. 2012. Data-driven models for regional coral-reef dynamics. Ecol. Lett. 15, 151–158. ( 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01720.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mumby PJ, Steneck RS, Hastings A. 2012. Evidence for and against the existence of alternate attractors on coral reefs. Oikos 122, 481–491. ( 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2012.00262.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hicks CC, Mcclanahan TR, Cinner JE, Hills JM. 2009. Trade-offs in values assigned to ecological goods and services associated with different coral reef management strategies. Ecol. Soc. 14, 10. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedlander A, DeMartini E. 2002. Contrasts in density, size, and biomass of reef fishes between the northwestern and the main Hawaiian Islands: the effects of fishing down apex predators. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 230, 253–264. ( 10.3354/meps230253) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedlander A, et al. 2005. The state of coral reef ecosystems of the main Hawaiian Islands. In The state of coral reef ecosystems of the United States and Pacific freely associated states: 2005, pp. 222–269. NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS NCCOS 11. Silver Spring, MD: NOAA/NCCOS Center for Coastal Monitoring and Assessment's Biogeography Team.

- 24.Kittinger JN, Dowling A, Purves AR, Milne NA, Olsson P. 2011. Marine protected areas, multiple-agency management, and monumental surprise in the northwestern Hawaiian Islands. J. Mar. Biol. 2011, 1–17. ( 10.1155/2011/241374) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green AL, Bellwood DR. 2009. Monitoring functional groups of herbivorous reef fishes as indicators of coral reef resilience – A practical guide for coral reef managers in the Asia Pacific region. IUCN working group on Climate Change and Coral Reefs. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- 26.Bellwood DR, Hughes TP, Hoey AS. 2006. Sleeping functional group drives coral-reef recovery. Curr. Biol. 16, 2434–2439. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.030) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Froese R, Pauly D.2012. FishBase. http://www.fishbase.org/.

- 28.Esselman PC, Infante DM, Wang L, Wu D, Cooper AR, Taylor WW. 2011. An index of cumulative disturbance to river fish habitats of the conterminous United States from landscape anthropogenic activities. Ecol. Restor. 29, 133–151. ( 10.3368/er.29.1-2.133) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.R Core Team. 2012. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graham NAJ, Nash KL. 2013. The importance of structural complexity in coral reef ecosystems. Coral Reefs 32, 315–326. ( 10.1007/s00338-012-0984-y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suzuki R, Shimodaira H. 2011. pvclust: hierarchical clustering with P-values via multiscale bootstrap resampling. R package version 1.2-2. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimodaira H. 2004. Approximately unbiased tests of regions using multistep-multiscale bootstrap resampling. Ann. Stat. 32, 2616–2641. ( 10.1214/009053604000000823) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rai P, Singh S. 2010. A survey of clustering techniques. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 7, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Friedman JH. 2001. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 29, 1189–1232. ( 10.1214/aos/1013203451) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ridgeway G, with contribution of others. 2013. gbm: generalized boosted regression models. R package version 2.0-8. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elith J, Leathwick JR, Hastie T. 2008. A working guide to boosted regression trees. J. Anim. Ecol. 77, 802–813. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01390.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nyström M, et al. 2012. Confronting feedbacks of degraded marine ecosystems. Ecosystems 15, 695–710. ( 10.1007/s10021-012-9530-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vroom PS, Braun CL. 2010. Benthic composition of a healthy subtropical reef: baseline species-level cover, with an emphasis on algae, in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. PLoS ONE 5, e9733 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0009733) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diaz-Pulido G, McCook L. 2002. The fate of bleached corals: patterns and dynamics of algal recruitment. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 232, 115–128. ( 10.3354/meps232115) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ceccarelli DM, Jones GP, McCook LJ. 2011. Interactions between herbivorous fish guilds and their influence on algal succession on a coastal coral reef. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 399, 60–67. ( 10.1016/j.jembe.2011.01.019) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCook LJ, Jompa J, Diaz-Pulido G. 2001. Competition between corals and algae on coral reefs: a review of evidence and mechanisms. Coral Reefs 19, 400–417. ( 10.1007/s003380000129) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knowlton N. 2004. Multiple ‘stable’ states and the conservation of marine ecosystems. Prog. Oceanogr. 60, 387–396. ( 10.1016/j.pocean.2004.02.011) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bellwood DR, Fulton CJ. 2008. Sediment-mediated suppression of herbivory on coral reefs: decreasing resilience to rising sea-levels and climate change? Limnol. Oceanogr. 53, 2695–2701. ( 10.4319/lo.2008.53.6.2695) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nyström M. 2006. Redundancy and response diversity of functional groups: implications for the resilience of coral reefs. Ambio 35, 30–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mora C. 2008. A clear human footprint in the coral reefs of the Caribbean. Proc. R. Soc. B 275, 767–773. ( 10.1098/rspb.2007.1472) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cinner JE, McClanahan TR, Daw TM, Graham NAJ, Maina J, Wilson SK, Hughes TP. 2009. Linking social and ecological systems to sustain coral reef fisheries. Curr. Biol. 19, 206–212. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2008.11.055) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brewer TD, Cinner JE, Green A, Pressey RL. 2013. Effects of human population density and proximity to markets on coral reef fishes vulnerable to extinction by fishing. Conserv. Biol. 27, 443–452. ( 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2012.01963.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McClanahan TR, Cokos BA, Sala E. 2002. Algal growth and species composition under experimental control of herbivory, phosphorus and coral abundance in Glovers Reef, Belize. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 44, 441–451. ( 10.1016/S0025-326X(02)00051-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lapointe BE. 1997. Nutrient thresholds for bottom-up control of macroalgal blooms on coral reefs in Jamaica and southeast Florida. Limnol. Oceanogr. 42, 1119–1131. ( 10.4319/lo.1997.42.5_part_2.1119) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rabalais NN. 2002. Nitrogen in aquatic ecosystems. Ambio 31, 102–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McClanahan TR, Carreiro-Silva M, DiLorenzo M. 2007. Effect of nitrogen, phosphorous, and their interaction on coral reef algal succession in Glover's reef, Belize. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 54, 1947–1957. ( 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2007.09.023) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Szmant AM. 2002. Nutrient enrichment on coral reefs: is it a major cause of coral reef decline? Estuaries 25, 743–766. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith JE, Smith CM, Hunter CL. 2001. An experimental analysis of the effects of herbivory and nutrient enrichment on benthic community dynamics on a Hawaiian reef. Coral Reefs 19, 332–342. ( 10.1007/s003380000124) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jokiel PL, Coles S. 1977. Effects of temperature on the mortality and growth of Hawaiian reef corals. Mar. Biol. 43, 201–208. ( 10.1007/BF00402312) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gove JM, Williams GJ, McManus MA, Heron SF, Sandin SA, Vetter OJ, Foley DG. 2013. Quantifying climatological ranges and anomalies for pacific coral reef ecosystems. PLoS ONE 8, e61974 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0061974) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Williams GJ, Smith JE, Conklin EJ, Gove JM, Sala E, Sandin SA. 2013. Benthic communities at two remote Pacific coral reefs: effects of reef habitat, depth, and wave energy gradients on spatial patterns. PeerJ 1, e81 ( 10.7717/peerj.81) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Williams GJ, Knapp IS, Maragos JE, Davy SK. 2011. Proximate environmental drivers of coral communities at Palmyra atoll: establishing baselines prior to removing a WWII military causeway. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 62, 1842–1851. ( 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.05.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dollar SJ. 1982. Wave stress and coral community structure in Hawaii. Coral Reefs 1, 71–81. ( 10.1007/BF00301688) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Friedlander AM, Brown EK, Jokiel PL, Smith WR, Rodgers KS. 2003. Effects of habitat, wave exposure, and marine protected area status on coral reef fish assemblages in the Hawaiian archipelago. Coral Reefs 22, 291–305. ( 10.1007/s00338-003-0317-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jouffray J-B. 2013 Human and natural drivers of multiple coral reef regimes across the Hawaiian archipelago. Master's thesis. Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University. ( http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:su:diva-91. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting this article has been made available and uploaded in Dryad (doi:10.5061/dryad.rg832).