Summary

This study demonstrates that the intronic TP53 polymorphisms rs1642785 and rs17878362 impact on the formation of G4 structures, mRNA splicing and stability, and thus on the differential expression of isoform-specific transcripts of the TP53 gene.

Abstract

G-quadruplex (G4) structures in intron 3 of the p53 pre-mRNA modulate intron 2 splicing, altering the balance between the fully spliced p53 transcript (FSp53, encoding full-length p53) and an incompletely spliced transcript retaining intron 2 (p53I2 encoding the N-terminally truncated Δ40p53 isoform). The nucleotides forming G4s overlap the polymorphism rs17878362 (A1 wild-type allele, A2 16-base pair insertion) which is in linkage disequilibrium with rs1642785 in intron 2 (c.74+38 G>C). Biophysical and biochemical analyses show rs17878362 A2 alleles form similar G4 structures as A1 alleles although their position is shifted with respect to the intron 2 splice acceptor site. In addition basal FSp53 and p53I2 levels showed allele specific differences in both p53-null cells transfected with reporter constructs or lymphoblastoid cell lines. The highest FSp53 and p53I2 levels were associated with combined rs1642785-GG/rs17878362-A1A1 alleles, whereas the presence of rs1642785-C with either rs17878362 allele was associated with lower p53 pre-mRNA, total TP53, FSp53 and p53I2 levels, due to the lower stability of transcripts containing rs1642785-C. Treatment of lymphoblastoid cell with the G4 binding ligands 360A or PhenDC3 or with ionizing radiation increased FSp53 levels only in cells with rs17878362 A1 alleles, suggesting that under this G4 configuration full splicing is favoured. These results demonstrate the complex effects of intronic TP53 polymorphisms on G4 formation and identify a new role for rs1642785 on mRNA splicing and stability, and thus on the differential expression of isoform-specific transcripts of the TP53 gene.

Introduction

G-quadruplexes (G4) are monovalent cation-dependent structures formed in guanine rich regions of DNA or RNA that involve the interaction of four guanines in a cyclic Hoogsteen hydrogen bonding arrangement (1). Using bioinformatic and biochemical approaches, over 350000 G4 structures have been located throughout the genome (2). These DNA and RNA structures are implicated in the regulation of genomic stability (3–5), DNA replication (6), gene transcription (7), mRNA splicing (8–10), mRNA synthesis (10–12) and translation (13). Two G4s have been experimentally identified in the p53 pre-mRNA: one located in intron 3 (9) and another downstream of the cleavage/polyadenylation site (11). We have previously demonstrated that G4s in TP53 intron 3 regulated the alternative splicing of intron 2 thus altering the balance between two alternatively spliced transcripts, FSp53 and p53I2 (9). The FSp53 transcript encodes the canonical full length 53kDa p53 protein, also identified as TAp53 (transcriptionally active). In the p53I2 transcript, the presence of intron 2 sequences introduces several stop codons that preclude the synthesis of TAp53. However, usage of the AUG+40 for internal initiation of translation can generate the Δ40p53 protein (14,15). This protein lacks the first 39 residues corresponding to the transactivation domain 1 including the Hdm2-binding site and has been shown to modulate p53 transcriptional activities and p53-mediated growth suppression (14–17).

The sequence environment in proximity to the intron 3 G4 overlaps the common TP53 polymorphism rs17878362 [TP53 PIN3; A1 major allele with one copy of the 16-bp motif acctggagggctgggg; A2 minor allele two copies of this motif (18)]. The frequency of the A2 allele shows significant variations with ethnicity, with minor allele frequencies ranging from 0.15 to 0.21 in Indian populations to <0.05 in Asian populations (19). A recent meta-analysis on >10000 cases and controls showed that carriage of the rs17878362-A2 allele is significantly associated with an increased cancer risk (19). In addition, we have reported that rs17878362 is a modifier of the penetrance of germline TP53 mutations in the Li-Fraumeni syndrome (20,21). In silico algorithms predict that the allelic status of rs17878362 may alter the topology of the G4 structures formed in intron 3. In addition, rs17878362 is in close proximity to and in linkage disequilibrium with another TP53 polymorphism rs1642785 located in intron 2 (TP53 PIN2, c.74+38 G>C) and carried on the TP53 pre-mRNA and p53I2 transcripts that retain intron 2. The C allele frequency in Caucasians is around 22% whereas in African and Asian populations it is 55% (20–22). Several studies have assessed the association between rs1642785 genotypes and cancer susceptibility with inconsistent results that could be confounded by the linkage disequilibrium with other TP53 polymorphisms (20,23–26). Whether rs1642785 impacts on the expression or stability of the transcripts containing intron 2 also remains an open question.

In order to address some of these issues, we investigated by biophysical and biochemical approaches whether the presence of the rs17878362-A2 allele modified the formation of G4s in intron 3 and using TP53 deficient cells carrying reporter systems or lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) if different allelic combinations of rs1642785 and rs17878362 had an impact on the basal levels of FSp53 and p53I2 transcripts. We found that although the presence of the rs17878362-A2 allele did not affect the formation of the G4 structure per se, its relative position was modified with respect to the TP53 intron/exon boundaries and identified a previously unknown role for the rs1642785 variant allele as a factor underlying the lower basal levels of both the FSp53 and p53I2 transcripts observed in certain genetic backgrounds. Indeed, transcripts retaining intron 2 (i.e. p53I2 and TP53 pre-mRNA) containing the rs1642785-C allele showed reduced half-lives compared with transcripts carrying the rs1642785-G allele. Treatment of LCLs with G4 binding ligands, or ionizing radiation (IR) increased the FSp53 transcript levels and decreased p53I2 levels in rs1642785-GG/rs17878362-A1A1 cells suggesting that under these conditions full splicing is favoured by a mechanism involving a G4 structure and that in this genetic context the rs1642785-G allele has a minimal impact on transcript levels. Such trends were not observed in rs17878362-A2A2 cells carrying rs1642875-CC. Taken together, these results show that these two intronic polymorphisms affect not only the levels of the FSp53 and p53I2 transcripts but also pre-mRNA levels through allele dependent differences in splicing and transcript stability that involve G4 structures and RNA stability.

Materials and methods

Synthetic RNA oligomers and compounds

RNA oligomers derived from the TP53 intron 3 sequence (from the A1 allele, 42N which contains one copy of the 16-bp motif (underlined): 5′-AGGGUUGGGCU GGGGACCUGGAGGGCUGGGGGGCUGGGGGGC-3′; and from the A2 allele, 58D which contains the 16-bp sequence duplicated (double underlined): 5′-AGGGUUGGGCUGGGG ACCUGGAGGGCUGGGGACCUGGAGGGCU GGGGGGCUGGGGGGC-3′ were synthesized by IBA (Göttingen, Germany). The bisquinolinium compounds 360A (27) and PhenDC3 (28) and the trisubstituted acridine derivative Braco19 (29) were used to stabilize G4. Actinomycin D (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was stored at 1mg/ml in dimethyl sulfoxide.

Biophysical characterization of G4s

G4 formation of the 42N and 58D oligomers was assessed by competitive FRET-melting, thermal difference spectra (TDS) and circular dichroism (CD) and their respective thermal stability using UV-melting experiments. The competitive FRET-melting experiments were performed as described previously (30). The thermal stabilizations (ΔT ½) induced by 1 µM of 360A, Braco19 or PhenDC3 were measured with increasing 42N, 58D or ds26 (CAATCGGATCGAATTCGATCCGATTG) competitor concentrations. TDS, CD and UV-melting experiments were conducted using the 42N (3 µM) and 58D (2 µM) oligomers buffered in a 10mM pH 7.0 lithium cacodylate supplemented with 2.5mM KCl. For both RNA sequences, TDS were calculated from the UV spectra (220–335nm) measured at temperatures of 90°C (±2°C) and 4°C (±2°C) using an Uvikon XL UV/Vis spectrophotometer (31) as described previously (9). CD spectra were recorded using a JASCO J-810 spectropolarimeter as described previously (9,32) after heating at 90°C for 5min followed by cooling to 20°C at 1°C/min rate. UV-melting experiments and analysis were conducted as described previously (9). Quadruplex denaturation/renaturation was followed by recording absorbance at 295nm using the same spectrophotometer as for TDS measurements.

Cell culture

The LCLs used in this study were established from the peripheral blood of breast cancer (BC) patients (33). Prior to usage, the rs17878362 and rs1642785 status was analysed by sequencing as described below (Supplementary Table I, available at Carcinogenesis Online). LCLs were grown in RPMI 1640 containing Glutamax (Invitrogen™, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco®, Life Technologies) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The H1299 cell line, derived from a human bronchial adenocarcinoma and containing a homozygous partial deletion of the TP53 gene, lacks expression of all p53 protein isoforms (34). It was cultured in DMEM containing Glutamax, 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. All cell lines were grown at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

TP53 genotype determination

Genomic DNA was extracted from LCLs using the DNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) and the region surrounding the rs1642785 and rs17878362 polymorphisms amplified using the GoTaq® Hot Start Polymerase kit (Promega) and primers at a final concentration of 0.5 µM (TP53 IARC database (http://p53.iarc.fr/). PCR products were purified using ExoSAP-IT (USB) following the manufacturer’s recommendations and sequenced using 150nM Forward primer and BigDye terminator V1.1 (Invitrogen™).

Drug treatment and radiation

The day before treatment or radiation, LCLs were diluted to 0.5×106 cell/ml and grown overnight. Cells (2.107) were treated for 48h with the G4 binding ligand 360A (final concentration of 500nM or 5 µM) or PhenDC3 (final concentration 500nM). For experiments assessing mRNA stability cells (2.107) were treated with actinomycin D at a final concentration of 1 µg/ml for up to 4h. After each treatment cells were harvested and nuclear RNA extracted.

Cells (2.107) were irradiated using a 4.5 MeV linear electron accelerator facility built by EuroMeV (Buc, France) operated in a chopped mode as described previously (35). Cells received a single submicrosecond pulse with a beam current adjusted to provide the required dose (0.1 or 2 Gy). Cells were harvested 48h after radiation and nuclear RNA extracted.

Green fluorescent protein-based splicing reporter system

The TP53 pEGFP-E2E4 splicing reporter assay was used as previously reported (9). Briefly, the TP53 sequences from the end of exon 2 to the beginning of exon 4, excluding ATG 1 and 40, and carrying different combinations of the rs1642785 and rs17878362 alleles were introduced between the first ATG and the green fluorescent protein (GFP) coding sequence (Supplementary Figure 1, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Plasmids carrying mutations or deletions were produced by QuickChange® site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, Santa Clara, CA). The day before transfection, p53-null H1299 cells (2.2×105 cells) were plated in 100mm diameter dish. Transient transfection of plasmids (3.75 µg) was performed using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen™) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were harvested 48h after transfection and total RNA extracted.

Total and nuclear RNA extraction

Total RNA extraction from H1299 transfected cells was performed using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). Nuclear RNA was extracted from LCLs (at least 4.107 cells/treatment) to facilitate the detection and quantification of transcripts. Briefly, the cell pellet was resuspended twice in three volumes of buffer A (10mM Hepes pH 7.9, 1.5mM MgCl2, 10mM KCl, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 1mM DTT) and once in two volumes of buffer B (20mM Hepes pH 7.9, 400mM NaCl, 1.5mM MgCl2, 0.2mM EDTA, 0.5mM DTT) followed by a final step of supernatant clean-up with the RNeasy Mini kit.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR analysis

The levels of total TP53 mRNA, its pre-mRNA and the FSp53 and p53I2 transcripts were quantified by reverse transcription (high capacity cDNA reverse transcription, Invitrogen™) of 2 µg of nuclear RNA followed by quantitative PCR (Fast SYBR® Green master mix, Applied Biosystems®) using specific primers for each transcript (Supplementary Table II, available at Carcinogenesis Online) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. These expression levels were normalized to that of TATA box binding protein (TBP). The ΔC t was calculated as the average of at least four independent experiments. To quantify the level of FS-GFP and I2-GFP transcripts in the reporter assay a similar quantitative reverse transcriptase-PCR (qRT-PCR) method was used except that 1 µg of total RNA was used and expression normalized to that of neomycin (Supplementary Table II, available at Carcinogenesis Online). The ΔC t was calculated with an average of at least four experiments. OGG1 and GAPDH mRNA levels were measured using Taqman chemistry (assay Hs00249899_m1 for OGG1, Hs99999905_m1 for GAPDH, Applied Biosystems).

Results

Formation of G4 structures by the A2-intron 3 TP53 sequence

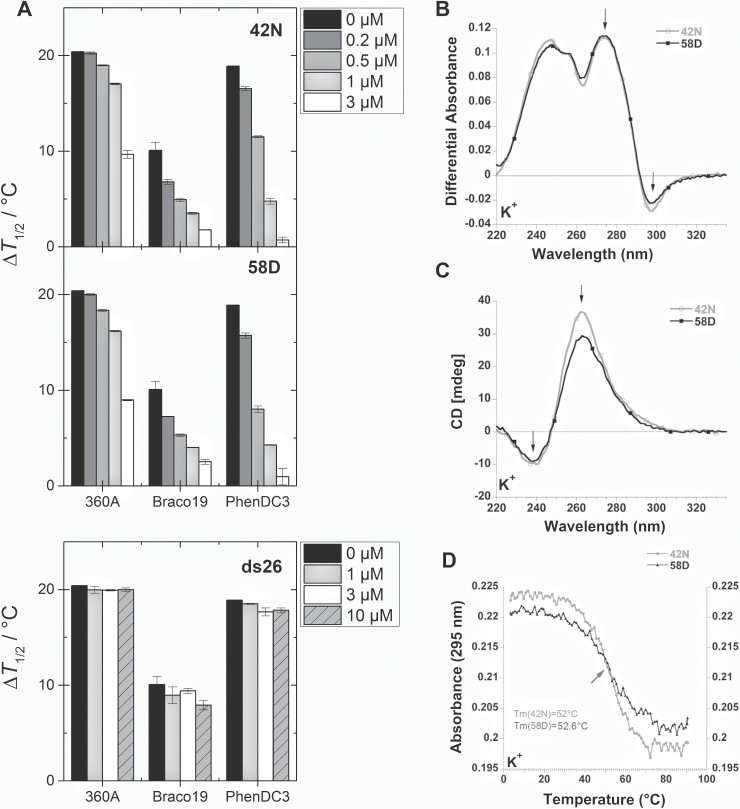

We previously reported the formation of G4s in TP53 intron 3 carrying the A1 allele of rs17878362 and their overlap with this polymorphic sequence (9). We have now investigated whether the duplication of this 16-bp sequence (rs17878362-A2 allele) could affect the formation of G4 structures. Using the online prediction tool QGRS Mapper [using default parameters, http://bioinformatics.ramapo.edu/QGRS/index.php (36)], several putative, overlapping G4 structures were identified in the intron 3 sequence carrying the A2 allele (Supplementary Table III, available at Carcinogenesis Online). To demonstrate the formation of G4 structures, biophysical analyses were performed using two synthetic RNA oligomers derived from this region: a 58mer sequence containing the rs17878362-A2 allele (oligomer 58D) and a 42mer containing the rs17878362-A1 allele (oligomer 42N); the latter corresponded to oligomer 2 of (9). Competitive FRET experiments performed on F21T with three ligands selective for G4s (360A, Braco19 and PhenDC3) confirmed the formation of G4 structures in the 42N oligomer (9) and demonstrated their formation in the 58D oligomer. For all three ligands, induced stabilization (ΔT ½) decreased with increasing 42N or 58D concentrations (Figure 1A), indicating that an increasing proportion of ligands interacted with the 42N or 58D oligonucleotides instead of F21T. No such effect is observed with the ds26 duplex competitor that is unable to form a G4, confirming the selectivity of these ligands towards G4 structures. Moreover, the similar effects of the two competitors 42N and 58D with either ligand suggests that the G4 structures adopted by these sequences are very similar since different G4s would be expected to displace ligands in different proportions. The TDSs of the 42N and 58D sequences (Figure 1B) show typical features for G4 structures and their superimposition is indicative of similar G4 structures consistent with the competitive FRET results. The CD spectra of intron 3-derived RNA oligomers (Figure 1C) also displayed a signature typical for G4 structures. Finally, thermal stability was determined by UV-melting experiments (Figure 1D). The melting temperatures (T m) was 52°C for 42N and 52.6°C for 58D suggesting a minor impact of the additional bases present in the A2 allele on G4 stability. These T ms were obtained at low ionic strength (2.5mM K+ only), suggesting that these RNA G4s are stable under near-physiological conditions.

Fig. 1.

Competitive FRET melting, TDS, CD and UV melting curves of the 42N and 58D oligomers. (A) Competitive FRET melting assay with the 42N and 58D oligomers. Thermal stabilization induced by 1 µM of G4 ligand (360A, Braco19 or PhenDC3) on the F21T sequence (0.2 µM) in the absence and presence of increasing competitor concentrations (42N, 58D and ds26). (B) TDS between the absorbance spectra recorded at 90±2°C and at 4±2°C (in K+). (C) CD recorded at 20°C (in K+) on a JASCO J-810 spectropolarimeter using 1cm path length quartz cuvettes. The oligonucleotides were annealed by heating at 90°C for 5min, followed by cooling to 20°C at 1°C/min rate. (D) UV melting profiles. Absorbance at 295nm is plotted as a function of temperature for both oligomers in K+.

A primer extension analysis was used to compare the in vitro formation of G4 structures in the A1 and A2 sequence context (Supplementary Figure 2A–D, available at Carcinogenesis Online). This assay takes advantage of differential cation-dependent stability of G4 structures as described in Marcel et al. (9). A band corresponding to the full-length RT product was observed in the presence of NaCl that was shifted by 16-bp on the rs17878362-A2 substrate compared with the A1 substrate (Supplementary Figure 2A and B, available at Carcinogenesis Online). In the presence of KCl the bands corresponding to the full-length RT product were reduced in intensity (Supplementary Figure 2A and B, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Furthermore the RT-pauses, particularly those involving guanines located within rs17878362 or close-by, were more intense (Supplementary Figure 2C, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Taken together these results suggest that the G4s formed in the rs17878362-A1 or -A2 sequence context are quasi-identical, the main difference being that the duplication introduces a 16-bp spacer element that moves the G4 structures away from the splice acceptor site of intron 2.

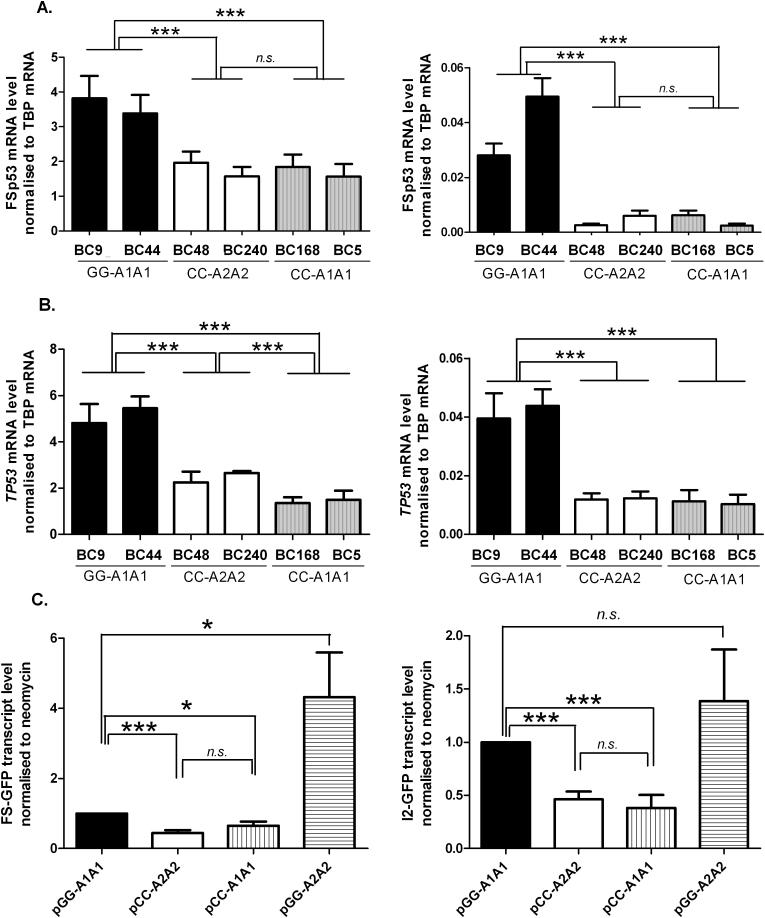

Impact of rs1642785 and rs17878362 on endogenous TP53 transcript expression

The basal expression levels of the FSp53 and p53I2 transcripts were examined in LCLs with defined rs1642785 and rs17878362 allele. First we quantified by qRT-PCR the two transcripts in two LCLs homozygous for the rs1642785-G and rs17878362-A1 alleles and two LCLs homozygous for the rs1642785-C and rs17878362-A2 alleles, the more commonly found haplotypes (Figure 2A). The mean level of the FSp53 transcript was significantly higher in the LCLS carrying rs1642785-GG/rs17878362-A1A1 than in those carrying rs1642785-CC/rs17878362-A2. The expression levels of p53I2 were significantly lower (up to 100-fold) than FSp53 in these four LCLs and showed significant allele specific differences, with the rs1642785-CC/rs17878362-A2A2 LCLs having a 6- to 10-fold lower level compared with the rs1642785-GG/rs17878362-A1A1 LCLs. To better understand the impact of rs1642785 on transcript levels, we analysed transcript levels in two additional LCLs homozygous for the rs17878362-A1 allele but carrying the rs1642785-C allele (rs1642785-CC/rs17878362-A1A1). In these LCLs, FSp53 and p53I2 expression levels were similar to those seen in rs1642785-CC/ rs17878362-A2A2 LCLs. These data suggest that the presence of the rs1642785-C allele influences the expression of both the FSp53 and p53I2 transcripts under basal conditions.

Fig. 2.

Variation in TP53 transcript levels depending on the rs17878362 and rs1642785 allele status. (A) FSp53 (left panel) and p53I2 (right panel) transcript levels in LCLs carrying the rs17878362-A1 allele with the rs1642785-G allele (GG-A1A1) or carrying the rs17878362-A2 allele with the rs1642785-C allele (CC-A2A2) or carrying the rs17878362-A1 allele with the rs1642785-C allele (CC-A1A1) measured using quantitative RT-PCR with TBP expression used as the reference. ***P ≤ 0.001 (Student’s t-test). (B) TP53 total mRNA (left panel) and pre-mRNA (right panel) transcript levels in LCLs carrying the rs17878362-A1 allele with the rs1642785-G allele (GG-A1A1) or carrying the rs17878362-A2 allele with the rs1642785-C allele (CC-A2A2) or carrying the rs17878362-A1 allele with the rs1642785-C allele (CC-A1A1) measured using quantitative RT-PCR with TBP expression used as the reference. ***P ≤ 0.001 (Student’s t-test). (C) FS-GFP (left panel) and I2-GFP (right panel) transcript levels in p53-null transfected HT1299 cells were monitored by quantitative RT-PCR with neomycin expression used as the reference. Each bar of the histogram represents the mean value ± SEM of at least four experiments performed on the LCLs. n.s., non-significant; *P ≤ 0.05, ***P ≤ 0.001 (Student’s t-test).

Allele specific differences in total TP53 mRNA levels have been reported by Gemignani et al. (37), in LCLs with the rs17878362-A1A1 genotype being associated with statistically higher basal levels compared with either the rs17878362-A1A2 or rs17878362-A2A2 genotypes. Using RNA samples from the six LCLs from this present study not only were the highest total TP53 mRNA levels seen in the rs1642785-GG/rs17878362-A1A1 sequence context (Figure 2B, left panel) but also TP53 pre-mRNA levels (Figure 2B, right panel) and as for the FSp53 and p53I2 transcripts, lower levels of total TP53 mRNA and pre-mRNA were associated with carriage of the rs1642785-C allele. As no LCL homozygous for the allelic combination (rs1642785-GG/rs17878362-A2A2) was available because of its very low population frequency [2% in Caucasian population according to the HapMap project (22)], we took advantage of an in vitro splicing assay (9) that makes use of a GFP-reporter system containing part of the TP53 sequence to investigate the impact of the four possible allelic combinations of rs1642785 and rs17878362 on p53 transcript levels in H1299 p53 null-cells (Supplementary Figure 1, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Transfection of reporters carrying each of the three allelic combinations assessed in LCLs gave the same relative expression profiles for FSp53 and p53I2 (Figure 2C). With the pGG-A2A2 reporter, corresponding to an allelic combination not tested in LCLs, levels of FSp53 were higher than with the other reporters whereas the p53I2 levels were similar to those observed with the pGG-A1A1 reporter but higher than those seen for either the pCC-A2A2 or pCC-A1A1 constructs. These data suggest that rs17878362 status affects expression of p53 transcripts only when associated with the rs1642785-G allele.

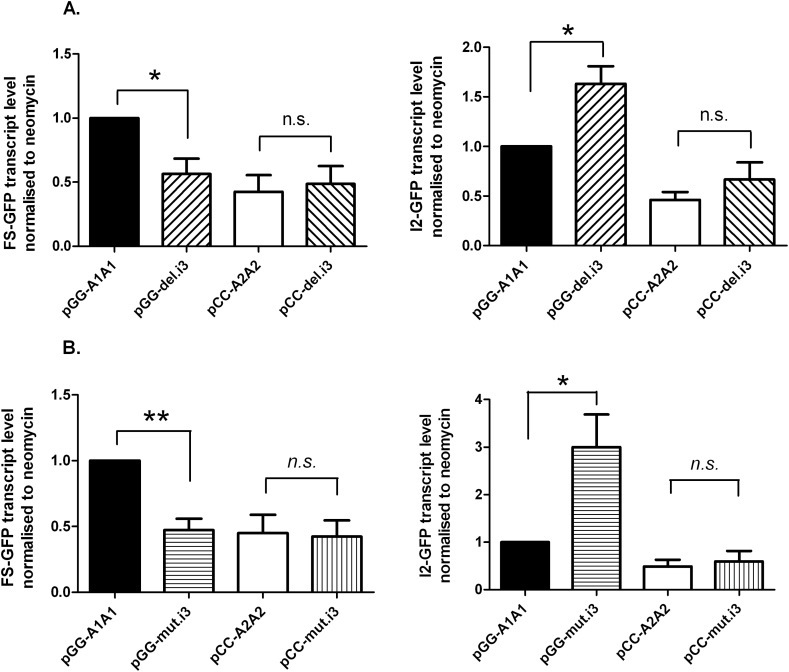

In order to assess the impact of the G4 structures on the basal levels of the FSp53 and p53I2 transcripts the guanines implicated in intron 3 were mutated or intron 3 deleted in these reporter constructs (Supplementary Figure 1, available at Carcinogenesis Online). These changes in the pGG-A1A1 reporter resulted in a reduction in FSp53 and an increase in p53I2 levels confirming the involvement of these guanines in G4 structures (Figure 3A and B). However the lower levels of FSp53 and p53I2 seen with the altered pCC-A2A2 vector were unchanged lending support to a role of rs1642785 in these low transcript levels.

Fig. 3.

The impact of sequence changes in intron 3 on TP53 transcript levels. (A) FS-GFP (left panel) and I2-GFP (right panel) transcript levels in p53-null H1299 cells transfected with reporter constructs deleted for intron 3 were monitored by quantitative RT-PCR with neomycin expression used as the reference. *P ≤ 0.05 (Student’s t-test) values are means ± SEM (≥4 independent experiments). (B) FS-GFP (left panel) and I2-GFP (right panel) transcript levels in p53-null HT1299 cells transfected with reporter constructs mutated in intron 3 were monitored by quantitative RT-PCR with neomycin expression used as the reference. n.s., non-significant; *P ≤ 0.05 and **P ≤ 0.01 (Student’s t-test) values are means ± SEM (≥4 independent experiments).

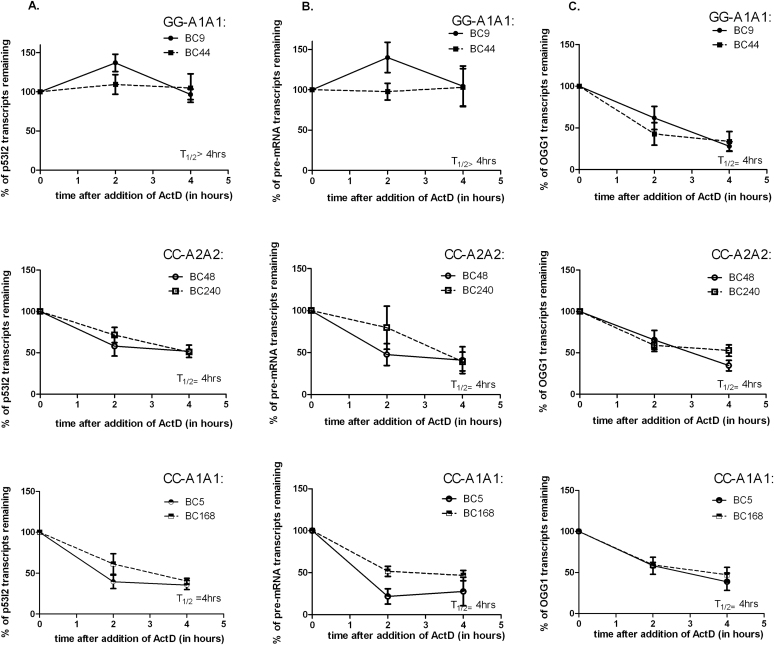

Impact of rs1642785 on the stability of transcripts containing intron 2

To investigate whether the presence of the rs1642785-C allele had an impact on the stability of the p53 transcripts that retain intron 2, we determined the half-life of the TP53 pre-mRNA and p53I2 in LCLs after treatment with actinomycin D. Under these experimental conditions, the half-life of both transcripts in the two rs1642785-GG/rs17878362-A1A1 LCLs exceeded 4h (Figure 4A and B). In contrast, their half-life in the four LCLS homozygous for rs1642785-CC and carrying either rs17878362-A1A1 or -A2A2 was approximately 4h, suggesting that the presence of rs1642785-C reduced the stability of both intron 2 containing transcripts (Figure 4A and B). Under the same experimental conditions, the half-life of the OGG1 transcript was found to be 4h in all the six lines in agreement with published studies [(38); Figure 4C]. These results lend support to the possibility that the rs1642785-C allele modulates the stability of p53I2 and TP53 pre-mRNA and that this is a contributory factor towards the lower basal transcript levels.

Fig. 4.

Effect of rs1642785 on mRNA stability. The transcripts were quantified by real-time PCR up to 4h after treatment of LCLs with actinomycin D and normalized to TBP for the LCLs homozygous for rs1642785-G and rs17878362-A1 alleles (BC9 and BC56) or the rs1642785-C and rs17878362-A2 alleles (BC48 and BC156) or rs1642785-C and the rs17878362-A1 C alleles (BC5 and BC168). (A) p53I2 transcript, (B) TP53 pre-mRNA and (C) OGG1 mRNA. Values are means ± SEM of at least three experiments. The half-life represented the time required to obtain half of the initial quantity of the transcript.

Impact of the stabilization of G4 structures on p53 transcript levels

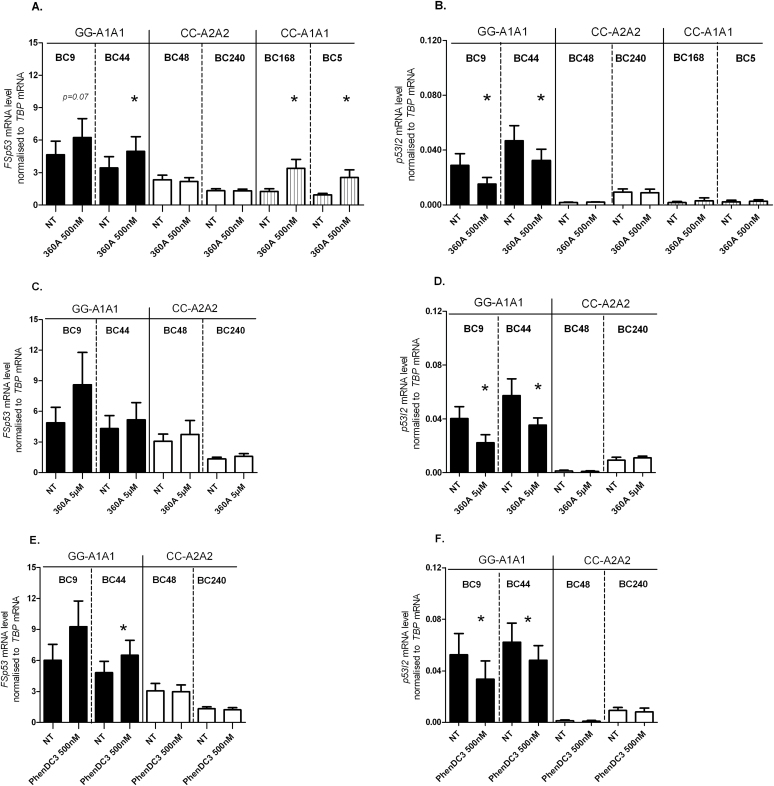

We have previously shown in the BC9 LCL homozygous for the TP53 rs17878362-A1 allele that G4 structures can be stabilized by the G4 binding ligand 360A (50nM final concentration), favouring the splicing of intron 2 and resulting in an increase of FSp53 and a reduction in p53I2 transcript levels (9). Here, we have extended these results to another LCL homozygous for the rs17878362-A1 allele (BC44) and to two LCLs homozygous for the rs17878362-A2 allele (BC48 and BC240). After treatment of BC9 and BC44 with the ligand 360A (500nM) for 48h we detected an increase in FSp53 and a significant decrease of p53I2 transcript levels compared with those seen in untreated cells (Figure 5A and B) confirming our previous data obtained in BC9 cells that G4 structures are involved in splicing of the A1-intron 2 (9). In contrast, no major effect on the level of either transcript could be detected after treatment with 360A (500nM) in the two LCLs examined homozygous for the rs17878362-A2 allele (BC48 and BC240; Figure 5A and B). In order to assess whether this lack of effect in the presence of the rs17878362-A2 allele was dose- or ligand-dependent, expression levels were examined after treatment with higher doses of 360A (5 µM) or the ligand PhenDC3 (500nM). After each treatment, no changes in FSp53 or p52I2 transcript levels were observed (Figure 5C–F). We next examined the effect of 360A in two LCLs homozygous for rs17878362-A1 but carrying rs1642785-C (BC5 and BC168). As in BC9 and BC44, we found an increase in FSp53 levels in BC5 and BC168 after treatment with 360A compared with untreated cells (Figure 5A). This indicates either that G4 binding ligands have no impact on G4 structures when located in the rs17878362-A2 allele or that the delocalized G4 structures in rs17878362-A2 allele do not impact on intron 2 splicing. Moreover, p53I2 levels were unchanged in BC5 and BC168 after 360A treatment compared with untreated cells (Figure 5B), paralleling the response for p53I2 after 360A treatment in the rs1642785-CC/rs17878362-A2A2 LCLs. These data indicate that the effect of rs1642785-C overcomes the impact of G4 structures on p53I2 transcript levels. Nevertheless, our results are compatible with the hypothesis that in the presence of the rs17878362-A1 allele G4 stabilization by 360A treatment favours intron 2 splicing resulting in an increase in FSp53 levels with a concomitant decrease in p53I2.

Fig. 5.

Effect of G4 ligands on TP53 transcript levels depending on the status of rs17878362 and rs1642785. The relative levels of FSp53 and relative p53I2 transcript levels were measured 48h after treatment with 500nM of 360A (panels A and B), 5 µM of 360A (panels C and D) and 500nM of PhenDC3 (panels E and F). Each bar of the histogram represents the mean value ± SEM of at least four experiments performed on the LCLs. *P ≤ 0.05: Student’s paired t-test. NT, non-treated cells.

Expression of TP53 transcripts after exposure to IR

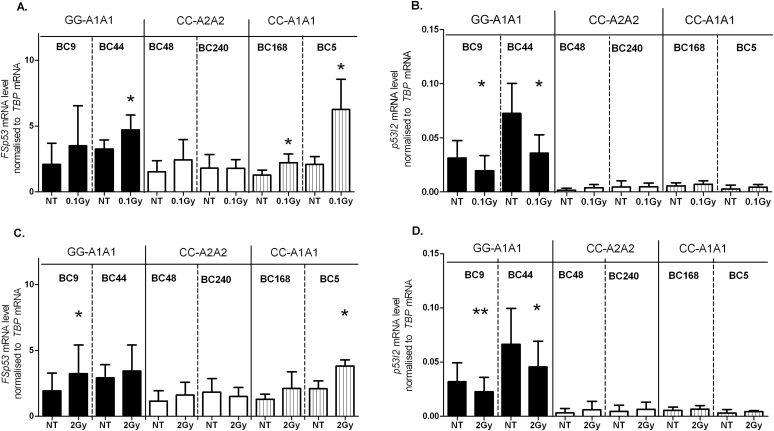

In order to assess whether the allele specific expression of FSp53 and p53I2 transcripts could be affected by DNA damage, we next exposed the same three pairs of LCLs that had been investigated after exposure to 360A to IR using a linear electron accelerator. Treatment of the four LCLs carrying rs17878362-A1A1 with 0.1 Gy resulted in an increase in FSp53 transcript levels. However, this increase was accompanied by a concomitant decrease in the p53I2 levels only in the two lines carrying rs1642785-G alleles. In the two lines carrying rs1642785-CC/rs17878362-A2A2 alleles, low dose IR exposure had no impact on either FSp53 or p53I2 levels (Figure 6A and B). After exposure to 2 Gy of IR, the most robust change detected was a reduction in p53I2 levels associated with an increase in FSp53 levels in the rs1642785-GG/rs17878362-A1A1 LCLs, compatible with increased splicing of intron 2. This higher radiation dose had no impact on FSp53 levels in the two rs17878362-A2A2 lines nor on the low p53i2 transcript levels associated with the rs1642785-C allele.

Fig. 6.

TP53 transcript levels after DNA damage induced by IR. FSp53 and p53I2 transcript levels normalized to TBP 48h after exposure of LCLs to 0.1 Gy (panels A and B) or 2 Gy (panels C and D) irradiation. The histograms represent the mean values ± SEM of at least four experiments performed on the six LCLs. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01: Student’s paired t-test. NT, non-treated cells.

Since profiles of FSp53 and p53I2 expression levels suggest a shift in alternative splicing of intron 2 in response to IR in the two rs1642785-GG/rs17878362-A1A1 LCLs, we investigated whether IR exposure would affect splicing of intron 2 using the reporter assay. In response to IR, the most robust alteration was a reduction of the p53I2 transcript in the rs1642785-GG rs17878362-A1A1 context (Supplementary Figure 3, available at Carcinogenesis Online). Intriguingly the reduction in p53I2 transcript levels after IR exposure seen in the rs1642785-GG/rs17878362-A1A1 reporter was not seen in the rs1642785-GG/rs17878362-A2A2 reporter. These results suggest that changes in transcript levels after exposure to IR involve the modulation of splicing of intron 2 in a manner dependent on the TP53 genetic background. In addition, as they paralleled the responses seen after exposures to G4 binding ligands, changes in splicing may result from changes in G4 stability.

Discussion

The TP53 gene expresses several protein isoforms encoded by different transcripts whose expression is finely regulated at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. In particular, the FSp53 and p53I2 transcripts are generated by alternative splicing of the p53 pre-mRNA and encode two related p53 protein isoforms (14,15). We previously reported that sequences in intron 3 surrounding the most frequent allele (A1) of rs17878362, can form G4 structures and that treatment of the BC9 LCL homozygous for this allele with the G4 binding ligand 360A significantly increased the levels of FSp53 while reducing those of the p53I2 transcript. These results suggested that G4 structures in intron 3 regulate the splicing of intron 2 and thus the balance between the FSp53 and p53I2 transcripts (9). In this present study we show, using biophysical methods and in vitro RT elongation assays that G4s can form with similar structure and stability in both the A1 and A2 sequence context, the main notable difference being in the position of these G4s with respect to the splice junction of intron 2. Using LCLs treated with different G4 binding ligands, our results support a role for G4 structures in the splicing of intron 2 only in the context of the rs17878362 A1 allele, whereas the A2 allele seems not to be associated with G4-mediated splicing of intron 2. Changes in the location of G4 structures with respect to the intron 2 splice junction due to the rs17878362-A2 allele may indeed abolish the impact of G4 structures on splicing of intron 2. G4 structures are known to be structural binding motifs for RNA-binding proteins, including hnRNP proteins, involved in alternative splicing [reviewed in ref. (10)] and it has been shown that the position of hnRNP protein binding is critical for the inclusion of alternative exons (39). There is also accumulating evidence for sequence context dependent splicing and it has been reported that the intronic guanine tract density and length correlate with hnRNP H/F enhancer function (40,41). Furthermore, the presence of polymorphisms near splicing sites can influence splicing (42). Clearly the topology of the region implicated in the splicing of intron 2 and the sequence duplicated in the A2 allele in intron 3 are expected to modify these criteria. However, whether the G4 structures formed in the A2 allele context can be stabilized remains an open question to be resolved. The results obtained using the pGGA2A2 construct would lend support to the idea that the G4 structures formed in the A2 allele sequence context are more stable than those seen in the A1 context as higher levels of FSp53 are observed.

In addition, our data indicate that the lack of effect of G4 binding ligands on splicing of intron 2 in the rs17878362-A2 context could be explained by the presence of another polymorphism. Indeed, rs17878362 is in strong linkage disequilibrium with a second polymorphism located in intron 2, rs1642785, which overcomes the effect of rs17878362 and is associated with a drastic reduction of p53 transcripts levels. We have shown using LCLs treated with actinomycin that the half-lives of the p53 pre-mRNA and p53I2 transcript that both contain the C allele of rs1642785, is lower than that containing the G allele. This observation could explain both the reduction of TP53 mRNA total, p53I2 and FSp53 transcripts produced from the TP53 pre-mRNA in the presence of the rs1642785-C allele.

The rs1642785 polymorphism is located at the centre of a region rich in CA repeats and it has been shown that CA clusters are sufficient to induce the destabilization of mRNAs (43). It is thus tempting to speculate that the presence of the C allele results in long CA repeats, inducing a higher destabilisation of both the p53I2 transcript and the p53 pre-mRNA that contain this rs1642785 allele, whereas the G allele breaks the CA cluster and the destabilization effect.

Finally, we showed that both the G4 ligands and exposures to low and high doses of IR induced similar patterns of alternative p53 transcripts in the rs17878362-A1 genetic background; an increase of FSp53 transcript levels associated with a decrease in p53I2 transcript levels. In addition, the use of reporter vector assays showed that IR treatment affects the splicing of intron 2. We can thus speculate that the presence of G4 structures could impact on radiation responses. Indeed, it has been shown that the treatment of human glioblastoma cells or bacteria with G4 ligands radiosensitizes cells to X-ray and γ-irradiation exposure, respectively (44,45). In addition, a recent study reported that stabilization of a G4 structure by hnRNP H/F protein binding in response to UV-B exposure increases p53 mRNA processing thus increasing p53 activity (11).

Overall, our data show that FSp53 and p53I2 mRNA levels are strongly dependent upon the TP53 genetic context that modulates different transcriptional and post-transcriptional processes regulating p53 isoform expression. Such observations are not restricted to the FSp53 and p53I2 transcripts and the protein isoforms that they encode. Other polymorphisms have been involved in the differential expression of p53 isoforms by modulating transcriptional and translational process [reviewed in ref. (46)]. Two studies have shown that the expression of the mRNA encoding Δ133p53, an isoform lacking the first 132 residues is modulated through the presence of several polymorphisms (34,47). In addition, genetic variations in the 5UTR of FSp53 mRNA have been shown to affect the cap-independent translation of both p53 and Δ40p53 protein isoforms (48,49). Expression of p53 isoforms is thus under genetic control resulting in the possibility that patterns of expression of p53 isoforms may vary among populations.

Our data add to the growing evidence that non-coding genetic variations modulate expression of p53 isoforms by affecting different transcriptional, post-transcriptional and translational mechanisms. Genetic alterations can modify both nucleotide sequences and structures within p53 RNA that are cis-regulators of p53 expression. Since p53 isoforms have been shown to modulate p53 transcriptional activity and thus, the p53-mediated growth suppression, we may expect that in the general population, expression patterns of p53 isoforms are different in an individual-dependent manner. Thus, non-coding polymorphisms by modulating isoform expression may be as important as coding polymorphisms in regulating p53 activity [reviewed in ref. (50)] and contribute to the individual diversity of important processes such as p53-dependent responses to DNA damage, to ageing-related physiological stress and cancer susceptibility.

Supplementary material

Supplementary Tables I–III and Figures 1–3 can be found at http://carcin.oxfordjournals.org/

Funding

This work was supported by grant INCa 2009–192 “TP53 intron3” from the French National Cancer Institute to J.H., P.H. and J.L.M. Research in Inserm U612 is also supported by Institut Curie and Inserm. C.S. has a PhD fellowship from the French Ministry of Research and V.M. and L.P. were supported by funding from the EU FP7 network of excellence DoReMi (low dose research towards multidisciplinary integration) (249689). J.L.M. was supported by grants from ANR (Quarpdiem, TKi-net and Oligoswitch), Conseil Régional d’Aquitaine (“Chaire d’accueil”, “Projet de Maturation” and Aquitaine-Midi Pyrénées grants) and a “subvention libre” from Fondation ARC.

Conflict of Interest Statement: None declared.

Supplementary Material

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- BC

breast cancer

- CD

circular dichroism

- G4

G-quadruplex

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- IR

ionizing radiation

- LCL

lymphoblastoid cell line

- TDS

thermal difference spectra.

References

- 1. Lipps H.J., et al. (2009). G-quadruplex structures: in vivo evidence and function. Trends Cell Biol., 19, 414–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huppert J.L., et al. (2005). Prevalence of quadruplexes in the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res., 33, 2908–2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ribeyre C., et al. (2009). The yeast Pif1 helicase prevents genomic instability caused by G-quadruplex-forming CEB1 sequences in vivo . PLoS Genet., 5, e1000475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Paeschke K., et al. (2013). Pif1 family helicases suppress genome instability at G-quadruplex motifs. Nature, 497, 458–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Paeschke K., et al. (2011). DNA replication through G-quadruplex motifs is promoted by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Pif1 DNA helicase. Cell, 145, 678–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cayrou C., et al. (2012). Genome-scale identification of active DNA replication origins. Methods, 57, 158–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bochman M.L., et al. (2012). DNA secondary structures: stability and function of G-quadruplex structures. Nat. Rev. Genet., 13, 770–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gomez D., et al. (2004). Telomerase downregulation induced by the G-quadruplex ligand 12459 in A549 cells is mediated by hTERT RNA alternative splicing. Nucleic Acids Res., 32, 371–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marcel V., et al. (2011). G-quadruplex structures in TP53 intron 3: role in alternative splicing and in production of p53 mRNA isoforms. Carcinogenesis, 32, 271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Millevoi S., et al. (2012). G-quadruplexes in RNA biology. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA, 3, 495–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Decorsière A., et al. (2011). Essential role for the interaction between hnRNP H/F and a G quadruplex in maintaining p53 pre-mRNA 3′-end processing and function during DNA damage. Genes Dev., 25, 220–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Beaudoin J.D., et al. (2013). Exploring mRNA 3′-UTR G-quadruplexes: evidence of roles in both alternative polyadenylation and mRNA shortening. Nucleic Acids Res., 41, 5898–5911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Agarwala P., et al. (2013). The G-quadruplex augments translation in the 5′ untranslated region of transforming growth factor β2. Biochemistry, 52, 1528–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yin Y., et al. (2002). p53 Stability and activity is regulated by Mdm2-mediated induction of alternative p53 translation products. Nat. Cell Biol., 4, 462–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Courtois S., et al. (2002). DeltaN-p53, a natural isoform of p53 lacking the first transactivation domain, counteracts growth suppression by wild-type p53. Oncogene, 21, 6722–6728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ghosh A., et al. (2004). Regulation of human p53 activity and cell localization by alternative splicing. Mol. Cell. Biol., 24, 7987–7997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Maier B., et al. (2004). Modulation of mammalian life span by the short isoform of p53. Genes Dev., 18, 306–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lazar V., et al. (1993). Simple sequence repeat polymorphism within the p53 gene. Oncogene, 8, 1703–1705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sagne C., et al. (2013). A meta-analysis of cancer risk associated with the TP53 intron 3 duplication polymorphism (rs17878362): geographic and tumor-specific effects. Cell Death Dis., 4, e492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marcel V., et al. (2009). TP53 PIN3 and MDM2 SNP309 polymorphisms as genetic modifiers in the Li-Fraumeni syndrome: impact on age at first diagnosis. J. Med. Genet., 46, 766–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sagne C., et al. (2014). Age at cancer onset in germline TP53 mutation carriers: association with polymorphisms in predicted G-quadruplex structures. Carcinogenesis, 35, 807–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Garritano S., et al. (2010). Detailed haplotype analysis at the TP53 locus in p.R337H mutation carriers in the population of Southern Brazil: evidence for a founder effect. Hum. Mutat., 31, 143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fernandes T.A., et al. (2008). Evaluation of the polymorphisms in the exons 2 to 4 of the TP53 in cervical carcinoma patients from a Brazilian population. Cell. Mol. Biol. (Noisy-le-grand)., 54 (suppl), OL1025–OL1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jha P., et al. (2011). TP53 polymorphisms in gliomas from Indian patients: study of codon 72 genotype, rs1642785, rs1800370 and 16 base pair insertion in intron-3. Exp. Mol. Pathol., 90, 167–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Høgdall E.V., et al. (2003). Evaluation of a polymorphism in intron 2 of the p53 gene in ovarian cancer patients. From the Danish “Malova” Ovarian Cancer Study. Anticancer Res., 23, 3397–3404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Savage S.A., et al. ; National Osteosarcoma Etiology study group. (2007). Germ-line genetic variation of TP53 in osteosarcoma. Pediatr. Blood Cancer, 49, 28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Granotier C., et al. (2005). Preferential binding of a G-quadruplex ligand to human chromosome ends. Nucleic Acids Res., 33, 4182–4190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. De Cian A., et al. (2007). Highly efficient G-quadruplex recognition by bisquinolinium compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 129, 1856–1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Burger A.M., et al. (2005). The G-quadruplex-interactive molecule BRACO-19 inhibits tumor growth, consistent with telomere targeting and interference with telomerase function. Cancer Res., 65, 1489–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. De Cian A., et al. (2007). Fluorescence-based melting assays for studying quadruplex ligands. Methods, 42, 183–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mergny J.L., et al. (1998). Following G-quartet formation by UV-spectroscopy. FEBS Lett., 435, 74–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Guédin A., et al. (2008). Sequence effects in single-base loops for quadruplexes. Biochimie, 90, 686–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Angèle S., et al. (2003). ATM haplotypes and cellular response to DNA damage: association with breast cancer risk and clinical radiosensitivity. Cancer Res., 63, 8717–8725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Marcel V., et al. (2012). Diverse p63 and p73 isoforms regulate Δ133p53 expression through modulation of the internal TP53 promoter activity. Cell Death Differ., 19, 816–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Favaudon V., et al. (1990). CO2.- radical induced cleavage of disulfide bonds in proteins. A gamma-ray and pulse radiolysis mechanistic investigation. Biochemistry, 29, 10978–10989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kikin O., et al. (2006). QGRS Mapper: a web-based server for predicting G-quadruplexes in nucleotide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res., 34(Web Server issue), W676–W682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gemignani F., et al. (2004). A TP53 polymorphism is associated with increased risk of colorectal cancer and with reduced levels of TP53 mRNA. Oncogene, 23, 1954–1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Duan J., et al. (2013). Genome-wide survey of interindividual differences of RNA stability in human lymphoblastoid cell lines. Sci. Rep., 3, 1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. König J., et al. (2010). iCLIP reveals the function of hnRNP particles in splicing at individual nucleotide resolution. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol., 17, 909–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Xiao X., et al. (2009). Splice site strength-dependent activity and genetic buffering by poly-G runs. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol., 16, 1094–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang E., et al. (2012). Global profiling of alternative splicing events and gene expression regulated by hnRNPH/F. PLoS One, 7, e51266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lu Z.X., et al. (2011). Context-dependent robustness to 5′ splice site polymorphisms in human populations. Hum. Mol. Genet., 20, 1084–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hui J., et al. (2003). Novel functional role of CA repeats and hnRNP L in RNA stability. RNA, 9, 931–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Merle P., et al. (2011). Telomere targeting with a new G4 ligand enhances radiation-induced killing of human glioblastoma cells. Mol. Cancer Ther., 10, 1784–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Beaume N., et al. (2013). Genome-wide study predicts promoter-G4 DNA motifs regulate selective functions in bacteria: radioresistance of D. radiodurans involves G4 DNA-mediated regulation. Nucleic Acids Res., 41, 76–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Marcel V., et al. (2011). Biological functions of p53 isoforms through evolution: lessons from animal and cellular models. Cell Death Differ., 18, 1815–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bellini I., et al. (2010). DeltaN133p53 expression levels in relation to haplotypes of the TP53 internal promoter region. Hum. Mutat., 31, 456–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Grover R., et al. (2011). Effect of mutations on the p53 IRES RNA structure: implications for de-regulation of the synthesis of p53 isoforms. RNA Biol., 8, 132–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Khan D., et al. (2013). Effect of a natural mutation in the 5′ untranslated region on the translational control of p53 mRNA. Oncogene, 32, 4148–4159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Whibley C., et al. (2009). p53 polymorphisms: cancer implications. Nat. Rev. Cancer, 9, 95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.