Abstract

Aim:

The aim of the study was to evaluate the influence of aspirin on post-extraction bleeding in a clinical setup.

Materials and Methods:

Two hundred patients aged between 50 and 65 years who were indicated for dental extraction for endodontic reason were selected from the outpatient Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. The patients were randomly divided into aspirin continuing group (group A) and aspirin discontinuing group (group B). After checking all the vital signs, the extractions were carried out. Bleeding time and clotting time were recorded for evaluation by Chi-square test.

Results:

Chi-square test revealed that the bleeding time increased (3.8 ± 0.75) in group A patients continued with the aspirin therapy where as group B discontinued aspirin. Similarly, the clotting time increased in group B patients and decreased in group A patients. But in both the groups, bleeding and clotting time remained within normal limits.

Conclusion:

Reviewing most of the dental and medical literature, it can be concluded that there is absolutely no need to discontinue antiplatelet therapy for any ambulatory dental procedure, and even if the practitioner wishes to discontinue, it should not be for more than 3 daAQ2ys. This is also stated in the guidelines of the American Heart Association.

Keywords: Antiplatelet drugs, aspirin, bleeding time, tooth extraction

INTRODUCTION

Medical practitioners commonly advice their patients who are on antiplatelet therapy to either stop or alter their medications prior to surgical procedures due to fear of excessive and uncontrolled bleeding. It is a proven fact that aspirin causes increased risk of intraoperative as well as postoperative bleeding and also increased risk of thromboembolic events such as myocardial infraction and cerebrovascular accidents if the drug is continued.[1] Thrombotic and thromboembolic occlusion of blood vessels is the main cause of ischemic events in heart, lungs, and brain.[2] In case of blood vessel injury, hemostatic mechanism is responsible for stopping the extravasation. Mainly hemostatic mechanisms are characterized by two consecutive phases: Primary and secondary. Primary mechanism arrests early bleeding as a result of platelet plug formation.[3] The secondary hemostasis phase is mediated by a complex cascade of clotting factors which helps in the formation of fibrin clot.[4] In recent years, lot of research has been done and progress has been made in the field of antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants. These drugs have been utilized for the management of arterial thrombosis also.[2] Even though a number of antiplatelet and anticoagulant agents have been developed, aspirin and warfarin remain the standard drugs of choice.[5]

Development of aspirin dates back to 1897 and is considered as one of the safest and cheapest drugs worldwide. A general practitioner Lawrence Craven prescribed low-dose aspirin (baby aspirin) to his 400 patients and none of them developed myocardial infraction.[6] This was probably the first time in medical history where aspirin was used to prevent myocardial infarction. Since then, it has become the drug of choice for cardiologists.

The antithrombotic effect of aspirin is mediated by irreversible inhibition of cyclooxygenase activity in platelets. Phospholipase A2 acts on the cell membrane to release arachidonic acid on activation. Cyclooxygenase acts on arachidonic acid to produce thromboxane A2. Thromboxane A2 is a potent platelet stimulant which leads to degranulation of platelet and platelet aggregation. Aspirin inhibits cyclooxygenase enzyme and decreases the level of platelet stimulant thromboxane A2,[5] thus increasing the bleeding time. This is the important reason for a medical practitioner to stop aspirin 3-7 days prior to any invasive surgery.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the influence of aspirin on post-extraction bleeding.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was conducted at the outpatient Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Patients who were on aspirin therapy, aged between 50 and 65 years, and who had to undergo tooth extraction for endodontic reason with no mobility were selected for the study. Patients on warfarin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, heparin, steroids, or suffering from blood disorders and diabetes were excluded from the study. Informed consent was obtained from the patients and the ethical committee clearance was also obtained.

Two hundred patients including both males and females whose teeth were indicated for extraction were included in the study. Patients were randomly divided into group A and group B of 100 patients each. Group A patients continued to receive aspirin preoperatively, while Group B patients were asked to stop aspirin 7 days prior to extraction after consultation with the physician.

Preoperatively, all the vital signs (blood pressure and pulse) were measured. Bleeding time (White and Lee technique) and clotting time (Ivy's technique) were calculated. Extractions were carried out only if the above parameters were within normal range. After atraumatic extraction (forceps method) was performed, the bleeding time was recorded. Analgesics and antibiotics were prescribed as needed for pain and infection control.

Chi-square test was used to evaluate the relative frequencies of patients in both groups. Differences of parametric variables were tested with analysis of variance.

RESULTS

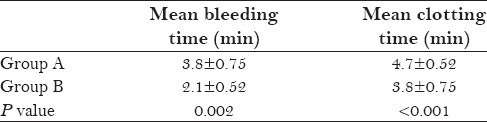

After applying Chi-square test, the mean bleeding time was calculated as 2.1 ± 0.52 min in the patients who discontinued baby aspirin (group B) 7 days prior to extraction. Bleeding time of group A patients who continued aspirin through the entire study was found to be 3.8 ± 0.75 min. This difference was statistically significant (P = 0.002) [Table 1 and Graph 1]. Although there was significant increase in the bleeding time of group A patients, it should be noted that the bleeding time of both the groups was within normal limits. Clotting time of group B patients was 3.8 ± 0.75 min and group A patients was 4.7 ± 0.52 min, which were also within the normal limits (normal range according to Ivy's method: 3-5 min).

Table 1.

Test statistics

Graph 1.

Mean bleeding time and mean clotting time (in minutes) of group A and group B patients

DISCUSSION

Historically, aspirin was used as an anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antipyretic drug for a short period of disease activity. In 1950, Lawrence Craven reported for the first time its long-term use to prevent myocardial infarction.[6] He advocated a lower dose for antiplatelet action. Antiplatelet activity of aspirin occurs at doses ranging from as low as 40 mg/day[7] to 320 mg/day.[8] Doses above 320 mg/day decrease the effectiveness of aspirin as an antiplatelet agent due to inhibition of prostacyclin production.[9] However, recent clinical trial indicates that 160 mg/day is optimal for antiplatelet action.[10] In emergencies where urgent antithrombotic action is required, a loading dose of 300 mg is advocated.[9] Usually, in the United States, daily dose of 81 mg, 160 mg, or 325 mg is prescribed, while in Europe and other countries, daily dose of 75 mg, 150 mg, or 300 mg is prescribed.[10]

Risk of continuing aspirin therapy prior to surgery is that with the alteration of platelet function, longer time period is required to stop bleeding from a surgical site. This is attributed to the alteration in primary hemostatic mechanism. Collet et al. stated that in patients on aspirin, the average risk of bleeding increases 1.5-fold. At the same time, there is a risk of stopping aspirin prior to surgery, which leads to a potential risk of rebound of thromboembolic vascular events. On stopping aspirin, thromboxane A2 activity increases to a greater extent with decrease in fibrinolytic activity.[11] Anderson et al. showed the existence of biological platelet rebound phenomenon on interruption of aspirin therapy. This could create a prothrombotic state which may lead to fatal thromboembolic events. Approximately 20% of these episodes are fatal and another 40% can lead to permanent disability.[12]

Practitioners who advocate the stoppage of aspirin have been debating among themselves regarding the time limit to stop aspirin. According to literature, the effect of aspirin on platelets is irreversible. The effect lasts for 7-10 days which is the life span of platelets.[13,14] Therefore, it was recommended to stop aspirin 7 days prior to surgical procedure.[15,16,17,18,19] Sonksen et al., in their study comprising 52 healthy individuals, reported that it is not recommended to withdraw aspirin for more than 5 days.[20] Wahl et al. advocated that aspirin should be discontinued for 3 days only, as after 3 days of interruption of aspirin, sufficient number of newer platelets would be present in the circulation for hemostasis.[21,22]

Now again the debate arises whether to stop aspirin therapy or not. Fear for uncontrolled bleeding encourages the practitioners to discontinue aspirin therapy. Some studies have shown that there is always an increased risk of bleeding in patients continuing aspirin.[23,24] Hence, some studies recommended stopping of aspirin therapy prior to surgical procedure.[17,19,25] However, if the aspirin therapy is discontinued, there is increased risk of thromboembolic events which can be fatal, but none of these have been reported in dental literature. Lawrence et al. mentioned in their article that there is scarcity of literature regarding dental surgeries involving patients on aspirin medication.[26] Little et al. reported that unless the bleeding time is increased above 20 min, aspirin-affected platelets would not cause significant bleeding complication.[22] Similar claims were made by Sonksen et al. and Gaspar et al.[20,27]

Canigral et al. conducted a research involving surgical extraction in patients on antithrombotic therapy. In 92% cases, the bleeding stopped within 10 min with pressure alone. This result was in accordance with the present study.[4] Gaspar et al. advocated that ambulatory oral surgical procedures can be performed in patients without discontinuing the use of aspirin.[27] A recent recommendation from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology is either continuing aspirin or clopidogrel therapy for minor oral surgical procedures in patients with coronary artery stents or delay the treatment until prescribed regimen is complicated.

The present study demonstrated that there was significant increase in the bleeding time in both the groups, but it was not difficult to stop the bleeding in any case. Although the bleeding time increased in group A patients, it still remained within the normal range, regardless of whether the patients continued or discontinued their aspirin therapy.[28,29,30] This result was similar to that of the study done by Canigral et al.[4] Valerin et al. conducted a study with 17 patients randomized to aspirin and 19 to placebo and found no differences in the bleeding outcomes for patients on aspirin. This finding suggested that there was no need to discontinue aspirin prior to any ambulatory oral surgical procedure.[31]

Adchariyapetch compared the postoperative bleeding in subjects who stopped taking aspirin and those who continued taking aspirin for 7 days prior to extraction. The mean bleeding time in both the groups was in normal range. After the procedure, there was no difficulty in achieving hemostasis. Therefore, they concluded that surgical extraction did not require discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy.[32] Matocha concluded in his study that the risk of bleeding after dental extraction is minimal in the patients with aspirin therapy and did not exceed 0.2-2.3%[33]

Murphy et al. concluded in their survey that 86% of the dental practitioners who advised patients to stop taking antiplatelet drugs prior to dental extraction did so with the consultation of the patients’ physicians, and found that the protocol followed by the physicians and dentists was not based on the current recommendations and guidelines.[34]

Valerin et al. concluded that the risk of stopping antiplatelet therapy and predisposing the patient to thromboembolic events overweighed the minimal risk of bleeding from dental procedures. Similar results were found in the study done by Nielsen et al.[35] Wahl reported in his study that of 950 patients receiving anticoagulation therapy, only 12 required (<1.3%) more than local measures to stop the bleeding. He concluded that while discontinuation of anticoagulation therapy has been a common practice, bleeding after dental surgery is rarely life threatening.

CONCLUSION

Thus, it can be concluded based on dental and medical literature that if a practitioner wishes to discontinue the aspirin therapy, it should not exceed more than 3 days. Moreover, it should not be done without consulting the physician. Risk of stopping antiplatelet therapy and predisposing the patient to thromboembolic events overweighs the minimal risk of bleeding from dental procedures. Although there was increase in bleeding time in the present study, it was not beyond the normal range. Hence, it can be concluded that low dose of aspirin should not be discontinued prior to dental extractions, as it predisposes the patient to unwanted thromboembolic events.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jafri SM, Zarowitz B, Goldstein S, Lesch M. The role of antiplatelet therapy in acute coronary syndromes and for secondary prevention following a myocardial infarction. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1993;36:75–83. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(93)90023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Owens CD, Belkin M. Thrombosis and coagulation: Operative management of the anticoagulated patient. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:1179–89. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2005.09.008. x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah M, Dave D, Dave R, Bharwani A, Shah A. Management of medically compromised patient in periodontal practice: An overview (Part 1) Adv Hum Biol. 2013;3:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cañigral A, Silvestre FJ, Cañigral G, Alós M, Garcia-Herraiz A, Plaza A. Evaluation of bleeding risk and measurement methods in dental patients. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2010;15:e863–8. doi: 10.4317/medoral.15.e863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dogne JM, de Leval X, Benoit P, Delarge J, Masereel B, David JL. Recent advances in antiplatelet agents. Curr Med Chem. 2002;9:577–89. doi: 10.2174/0929867024606948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craven LL. Acetylsalicylic acid, possible preventive of coronary thrombosis. Ann West Med Surg. 1950;4:95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brennan MT, Wynn RL, Miller CS. Aspirin and bleeding in dentistry: An update and recommendations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104:316–23. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patrono C, Ciabattoni G, Patrignani P, Pugliese F, Filabozzi P, Catella F, et al. Clinical pharmacology of platelet cyclooxygenase inhibition. Circulation. 1985;72:1177–84. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.72.6.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;324:71–86. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7329.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalen JE. Aspirin to prevent heart attack and stroke: What's the right dose? Am J Med. 2006;119:198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collet J, Montalescot G. Premature withdrawal and alternative therapies to dual oral antiplatelet therapy. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2006;8:G46–52. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson CS, Jamrozik KD, Broadhurst RJ, Stewart-Wynne EG. Predicting survival for 1 year among different subtypes of stroke: Results from The Perth Community Stroke Study. Stroke. 1994;25:1935–44. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.10.1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merritt JC, Bhatt DL. The efficacy and safety of perioperative antiplatelet therapy. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2002;13:97–103. doi: 10.1023/a:1016298831074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schafer AI. Effects of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs on platelet function and systemic hemostasis. J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;35:209–19. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1995.tb04050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watson CJ, Deane AM, Doyle PT, Bullock KN. Identifiable factors in post-prostatectomy haemorrhage: The role of aspirin. Br J Urol. 1990;66:85–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1990.tb14870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitchen L, Erichson RB, Sideropoulos H. Effect of drug-induced platelet dysfunction on surgical bleeding. Am J Surg. 1982;143:215–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(82)90071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conti CR. Aspirin and elective surgical procedures. Clin Cardiol. 1992;15:709–10. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960151026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scher KS. Unplanned reoperation for bleeding. Am Surg. 1996;62:52–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Speechley JA, Rugman FP. Some problems with anticoagulants in dental surgery. Dent Update. 1992;19:204–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sonksen JR, Kong KL, Holder R. Magnitude and time course of impaired primary haemostasis after stopping chronic low and medium dose aspirin in healthy volunteers. Br J Anaesth. 1999;82:360–5. doi: 10.1093/bja/82.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wahl MJ. Myths of dental surgery in patients receiving anticoagulant therapy. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:77–81. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Little JW, Miller CS, Henry RG, McIntosh BA. Antithrombotic agents: Implications in dentistry. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93:544–51. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.121391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferraris VA, Ferraris SP, Lough FC, Berry WR. Preoperative aspirin ingestion increases operative blood loss after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 1988;45:71–4. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)62401-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taggart DP, Siddiqui A, Wheatley DJ. Low-dose preoperative aspirin therapy, postoperative blood loss, and transfusion requirements. Ann Thorac Surg. 1990;50:424–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(90)90488-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferraris VA, Swanson E. Aspirin usage and perioperative blood loss in patients undergoing unexpected operations. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1983;156:439–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawrence C, Sakuntabhai A, Tiling-Grosse S. Effect of aspirin and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug therapy on bleeding complications in dermatologic surgical patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:988–92. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70269-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaspar R, Ardekian L, Brenner B, Peled M, Laufer D. Ambulatory oral procedures in patients on low-dose aspirin. Harefuah. 1999;136:108–10. 175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burger W, Chemnitius JM, Kneissl GD, Rücker G. Low-close aspirin for secondary cardiovascular prevention-cardiovascular risks after its perioperative withdrawal versus bleeding risks with its continuation-review and meta-analysis. J Intern Med. 2005;257:399–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harker LA, Slichter SJ. The bleeding time as a screening test for evaluation of platelet function. N Engl J Med. 1972;287:155–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197207272870401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shah KA, Patel MA, Tatu R, Patel V. Relationship between use of aspirin and post-extraction bleeding time: A randomized control and single blind study in fifty patients. J Res Adv Dent. 2013;2:167–72. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valerin MA, Brennan MT, Noll JL, Napeñas JJ, Kent ML, Fox PC, et al. Relationship between aspirin use and postoperative bleeding from dental extractions in a healthy population. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102:326. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adchariyapetch R. Dental extraction in patients on aspirin. Vajira Med J. 2009;53:283–89. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matocha DL. Postsurgical complications. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2000;18:549–64. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8627(05)70143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murphy J, Twohig E, McWilliams SR. Dentists’ approach to patients on anti-platelet agents and warfarin: A survey of practice. J Ir Dent Assoc. 2010;56:28–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nielsen JD, Laetgaard CA, Schou S, Jensen SS. Minor dentoalveolar surgery in patients undergoing antithrombotic therapy. Ugeskr Laeger. 2009;171:1407–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]