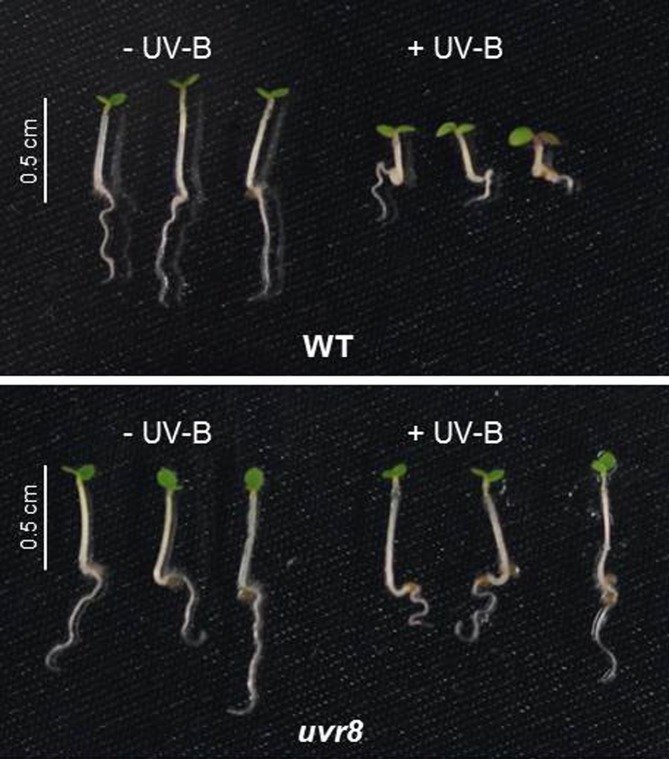

Most of us do what we can to avoid the DNA-damaging effects of UV-B rays. While plants can’t slap on sunscreen, put on a nice hat, or move to a shady spot, they too have ways to protect themselves from (and acclimate to) damaging UV-B radiation. For example, plants undergo UV-B-dependent photomorphogenic changes (see figure), including reduced hypocotyl and leaf expansion, increased stomatal closure, and the production of UV-absorbing compounds such as flavonoids. In Arabidopsis thaliana, UV-B-induced responses are mediated by the photoreceptor UV RESISTANCE LOCUS8 (UVR8) (Rizzini et al., 2011), which lacks the usual prosthetic light-sensing chromophore, instead relying on specific intrinsic tryptophans for light detection (Jenkins, 2014). Upon sensing UV-B light, the homodimeric UVR8 rapidly switches to its active, monomeric form, which interacts with the E3 ubiquitin ligase CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC1 (COP1), a well-known repressor of photomorphogenesis. Downstream of UVR8 and COP1, the bZIP transcription factor ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL5 (HY5) and its homolog HYH mediate most UV-B-induced changes in gene expression. While uncomplexed COP1 targets HY5 for ubiquitination, HY5 induces COP1 expression by binding to a specific UV-B-responsive element in its promoter, and UVR8-COP1 somehow stabilizes HY5 (Huang et al., 2012). However, it is not known how HY5 expression is induced by UV-B exposure. In addition, while HY5 potentially interacts with thousands of target genes, it is unclear how HY5 associates with chromatin in response to UV-B light exposure.

UV-B-induced photomorphogenesis. Wild-type (WT) and uvr8 mutant Arabidopsis seedlings grown for 4 d in the absence or presence of UV-B light. (Figure courtesy of M. Binkert.)

A recent study by Binkert et al. (2014) has brought us much closer to elucidating the role of HY5 in the UV-B response. First, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments using anti-HY5 antibodies demonstrated that UV-B treatment affects the association of HY5 with its target genes. Next, HY5 ChIP analysis of a uvr8 null mutant revealed that the UV-B-enhanced association of HY5 with its target promoters is regulated by UVR8. Conversely, the authors observed a reduced UV-B-specific response in plants overexpressing REPRESSOR OF UV-B PHOTOMORPHOGENESIS2, a negative regulator of UVR8. They also found that HY5 associates with the promoters of various UV-B-regulated genes but not with that of the constitutively expressed UVR8. Importantly, one of these UV-B-regulated genes is HY5 itself; ChIP analysis revealed that both HY5 and HYH specifically bind to the HY5 promoter. In fact, transgenic seedlings expressing the ProHY5:LUCIFERASE (LUC) reporter construct exhibited increased luminescence in response to UV-B irradiation in the hy5, hyh, and wild-type backgrounds, while ProHY5:LUC induction was nearly absent in the hy5 hyh double mutant background and completely absent in uvr8 knockout mutants, demonstrating that HY5 and HYH act redundantly to regulate UV-B-induced transcription of HY5. A similar assay using truncated and mutated HY5 promoters uncovered a T/G-box in the HY5 promoter that’s required for its UV-B responsiveness. The binding of this promoter region by HY5 and HYH was confirmed by electrophoretic mobility shift assays. Therefore, HY5 and HYH bind to the T/G-box of the HY5 promoter, thus playing a crucial role in the UV-B-induced regulation of HY5, which in turn mediates UV-B responses.

It remains to be determined how UV-B light enhances the binding of HY5 and HYH to the T/G-boxes in the promoters of their many target genes. Moreover, additional transcription factors that regulate UV-B-induced HY5 expression remain to be identified. Nonetheless, this pivotal study sheds light on the role played by HY5 to help plants cope with excess UV-B rays—sunscreen not required.

References

- Binkert M., Kozma-Bognár L., Terecskei K., De Veylder L., Nagy F., and Ulm R. (2014). UV-B-responsive association of the Arabidopsis bZIP transcription factor ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL5 with target genes, including its own promoter. Plant Cell 26: 4200–4213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Ouyang X., Yang P., Lau O.S., Li G., Li J., Chen H., and Deng X.W. (2012). Arabidopsis FHY3 and HY5 positively mediate induction of COP1 transcription in response to photomorphogenic UV-B light. Plant Cell 24: 4590–4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins G.I. (2014). The UV-B photoreceptor UVR8: from structure to physiology. Plant Cell 26: 21–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzini L., Favory J.J., Cloix C., Faggionato D., O’Hara A., Kaiserli E., Baumeister R., Schäfer E., Nagy F., Jenkins G.I., and Ulm R. (2011). Perception of UV-B by the Arabidopsis UVR8 protein. Science 332: 103–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]