Abstract

Background

We estimated the nationwide burden of nosocomial S. aureus bloodstream infection (SA-BSI), a major cause of nosocomial infection, in South Korea.

Methods

To evaluate the nationwide incidence of nosocomial SA-BSI, cases of SA-BSI were prospectively collected from 22 hospitals with over 500 beds over 4?months. Data on patient-days were obtained from a national health insurance database containing the claims data for all healthcare facilities in South Korea. The additional cost of SA-BSI was estimated through a matched case?control study. The economic burden was calculated from the sum of the medical costs, the costs of caregiving and loss of productivity.

Results

Three hundred and thirty nine cases of nosocomial SA-BSI were included in the study: 254 cases of methicillin-resistant SA-BSI (MRSA-BSI) and 85 cases of methicillin-susceptible SA-BSI (MSSA-BSI). Death related to BSI occurred in 81 cases (31.9%) of MRSA-BSI and 12 cases (14.1%) of MSSA-BSI. The estimated incidence of nosocomial MRSA-BSI was 0.12/1,000 patient-days and that of nosocomial MSSA-BSI, 0.04/1,000 patient-days. The estimated annual cases of nosocomial BSI were 2,946 for MRSA and 986 for MSSA in South Korea. The additional economic burden per case of nosocomial SA-BSI was US $20,494 for MRSA-BSI and $6,914 for MSSA-BSI. Total additional annual cost of nosocomial SA-BSI was $67,192,559.

Conclusion

In view of the burden of nosocomial SA-BSI, a national strategy for reducing nosocomial SA-BSI is urgently needed in South Korea.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12879-014-0590-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, Bacteremia, Incidence, Hospital infections

Background

Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) are a public health challenge, greatly affecting patient safety. The effects of HAIs include prolonged hospital stays, long-term disabilities, and unnecessary deaths [1],[2]. HAIs also impose a significant economic burden on the healthcare system. With increasing concern about patient safety in all circles of society, the prevention of HAIs has become an important aspect of the patient safety agenda [3].

Accurate determination of the burden of HAIs is fundamental in formulating HAIs management policies. In the United States, the estimated number of patients with at least 1 or more HAIs was approximately 648,000 in 2011 [4]. In the U.S., the burden of HAIs is reported periodically [4]-[6], and changing trends can be used to indicate infection control effectiveness. However, data on the nationwide burden of HAI in Asian countries are lacking. A national surveillance system, the Korean Nosocomial Infection Surveillance System (KONIS) monitors HAIs [7], but only ICU-acquired bloodstream infections (BSIs) were included. Therefore, studies estimating the burden of nationwide nosocomial infection are urgently required.

Staphylococcus aureus is one of the most important and devastating pathogens among HAIs, and many studies have shown that nosocomial S. aureus infection, especially bloodstream infection (SA-BSI) causes a tremendous burdens on the healthcare system [2],[8]-[12]. Recently, we reported the clinical characteristics and incidence of invasive S. aureus infection in a population-based study [13]. In the present study, we estimated the nationwide incidence and additional cost of nosocomial SA-BSI in South Korea.

Methods

Study population and sources of data

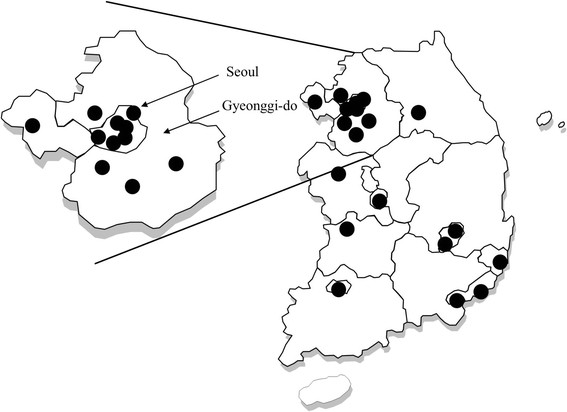

The population for this study consisted of all patients admitted to South Korean hospitals with over 500 beds during the June-September, 2011 study period. In 2011, there were 317 tertiary and general hospitals in South Korea, with 132,585 beds. Of these, 92 had over 500 beds, with a total number of 72,025 beds. We included 22 of a possible 92 hospitals, based on bed numbers and regional distributions (Figure?1). We considered the population of each region, and the proportion of selected hospitals in each region reflected the national proportion of the regional population. The 22 study hospitals had a total of 18,689 beds, which accounted for 25.9% of all hospitals with over 500 beds. All hospitals were acute-care hospitals.

Figure 1.

The locations of the 22 participating hospitals.

We obtained patient-day data for the general population and the study hospitals from the claims data of the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service, a mandatory medical insurance system that covers the entire population of South Korea [14]. Because the study was performed in 2011 and the claims data for that year were not yet complete, the data were extrapolated using the data for the previous 5?years. Data on medical costs were obtained from the administrative database of each study hospital.

Definitions

Nosocomial SA-BSI was defined as S. aureus infection which occurred after 48?hours of hospitalization, and in which S. aureus was isolated from blood culture. Cases of SA-BSI occurring within 48?hours of hospitalization, but for which the association between the BSI and the current hospitalization was clear were taken to be nosocomial. Exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) community-associated infection, 2) healthcare-associated community-onset infection, and 3) transfer to a study hospital after developing SA-BSI in another hospital.

Mortality associated with SA-BSI was classified as 1) definitely associated or 2) possibly associated. The former was defined as described previously [15]: 1) positive SA-BSI at the time of death or 2) death within 14?days of the documentation of SA-BSI without any other explanation. The latter was defined as: 1) death within 30?days of the documentation of SA-BSI without another explanation. Catheter-associated infection was defined according to the definition proposed by National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System [16]; in brief, positive blood culture drawn from a central venous catheter used within 48?hours of the onset of infection, with no other apparent source of the infection identified.

Hospital charges were defined as the amount hospitals billed for healthcare services to patients. Hospital costs were defined as the sum of hospital charges and the amount that hospitals received from the Reimbursement Service, a National Health Insurance Service in South Korea. Costs were expressed in US dollars ($) at the exchange rate of 1100 Won per $ (as of 1st June, 2011).

Matched case?control study

We conducted a matched case?control study to estimate the additional cost and length of hospitalization. In that study, nosocomial SA-BSI cases meeting the following conditions were excluded: 1) age under 18?years, 2) bloodstream infection that developed more than 30?days after admission. The latter criterion was adopted because of the difficulty of selecting control patients who were free of any nosocomial infections after 30?days of hospitalization. The control patients were selected according to the following criteria: 1) age (?5?years compared to the matched case), 2) date of admission (?2?weeks relative to the matched case), 3) confinement in the same ward as the case, and 4) underlying medical conditions similar to those of the matched case, and free of nosocomial infections. If two or more controls were identified, Charlson?s comorbidity index was used. Case?control pairs were classified into survivor and non-survivor pairs, according to whether the case patient was alive after 12?weeks of follow-up, irrespective of the outcome of the control patient.

Data variables

Baseline demographic variables, such as age, gender, and underlying diseases were collected from the SA-BSI and control patients. Data on variables related to clinical outcomes, including length of hospitalization, mortality, and intensive care unit use were also collected.

Data analyses

Estimation of annual incidence and number of SA-BSI

The annual number of SA-BSI cases was estimated in two steps. In the first step, the annual incidence of SA-BSI for the study hospitals was calculated as: (number of all nosocomial SA-BSI cases during the 4?months)???3/total patient-days of the study hospitals for the year 2011. In the second step, the annual number of SA-BSI cases was estimated as: (annual incidence of SA-BSI for the study hospitals) ? (total patient-days of the 92 hospitals for the year 2011).

Estimation of additional medical and societal costs of SA-BSI

We estimated the total additional costs of SA-BSI, including direct medical and societal costs. Because the additional medical cost and length of hospital stay could be influenced by survival, i.e., early deaths could lead to lower medical costs and shorter hospital stays, the calculations were performed separately for survivors and non-survivors.

The direct medical cost of SA-BSI was calculated as the product of the additional medical cost due to SA-BSI and the annual number of SA-BSI patients. The additional medical cost was calculated by subtracting the median hospital cost of the control patients from that of the corresponding SA-BSI patients. The calculation was performed separately for survivors and non-survivors.

The societal costs included the cost of caregiving, and productivity losses due to extended hospitalization and premature death. The cost of caregiving was calculated as the product of the daily cost of the hired caregiver and the excess length of stay (see above). Productivity loss due to extended hospitalization was calculated as the product of the daily wage of adults, the excess length of hospitalization, and the labor participation rate, taken as 25%. The productivity loss due to premature death was calculated from the number of deaths associated with SA-BSI and the annual wages reported by the Ministry of Labor in Korea (Labor Statistics of Korea, Ministry of Labor 2007; available from http://laborstat.molab.go.kr/). The productivity loss due to the premature death of a given patient was the sum of the annual wages up to the time that patient would have reached 65?years of age if he or she had not died. The annual discount rate was considered to be 5%. In calculating the latter, only patients under 65?years of age, the mandatory retirement age for almost all professions, were included.

Data were analyzed with Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA) and SPSS ver. 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Evidence-based healthcare Collaborating Agency and by each participating hospital. The statistical data and analyses were reviewed by KY and OSH.

Results

Baseline characteristics

During 4?months of the study period, 617 cases of SA-BSI were reported, of which 368 (59.6%) were cases of MRSA-BSI and 249 (40.4%) of MSSA-BSI. Community-associated infections consisted of 43 cases of MRSA-BSI and 109 cases of MSSA-BSI; 71 of the MRSA-BSI and 55 of the MSSA-BSI were healthcare-associated community-onset infections. After excluding these cases, 254 cases of MRSA-BSI and 85 cases of MSSA-BSI were included in the analysis. The baseline characteristics of the patients with nosocomial SA-BSI are shown in Table?1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patients with Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections

| Characteristic | MRSA (n?=?254) | MSSA (n?=?85) | P -value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 167 (65.7%)/87 (34.3%) | 41 (48.2%)/44 (51.8%) | 0.004 |

| Age, median (IQR) | 66 (54?75) | 58 (48?69) | |

| Location at BSI onset | |||

| Ward | 144 (56.7%) | 60 (70.6%) | 0.002 |

| ER | 6 (2.4%) | 7 (8.2%) | |

| ICU | 104 (40.9%) | 18 (21.2%) | |

| Central line-associated bloodstream infection | 94 (37.0%) | 17 (20.0%) | 0.004 |

| Interval between admission and detection of BSI | |||

| 1-7 days | 53 (20.9%) | 48 (56.5%) | |

| 8-14 days | 56 (22.0%) | 19 (22.4%) | |

| 15-21 days | 35 (13.8%) | 6 (7.1%) | |

| 22-30 days | 19 (7.5%) | 4 (4.7%) | |

| 31-60 days | 56 (22.0%) | 6 (7.1%) | |

| 61-90 days | 14 (5.5%) | 0 | |

| 91-180 days | 16 (6.3%) | 1 (1.2%) | |

| 181-365 days | 3 (1.2%) | 1 (1.2%) | |

| Over 365?days | 2 (0.8%) | 0 | |

Abbreviations: MRSA Methicillin-resistant S. aureus, MSSA Methicillin-susceptible S. aureus, IQR Interquartile range, BSI Bloodstream infection, ER Emergency room, ICU Intensive care unit.

Clinical features of nosocomial SA-BSI

Of the 254 cases of MRSA-BSI, 104 (40.9%) occurred in the ICU, compared with 18 (21.2%) of the 85 cases of MSSA-BSI. While 163 cases (64.2%) of MRSA-BSI occurred within 30?days of hospitalisation, only 77 cases (90.6%) of MSSA-BSI occurred within this time period (Table?1).

Catheters were the most frequent primary site of infection for both MRSA-BSI and MSSA-BSI. Pneumonia and surgical site infection were frequently related to MRSA-BSI, while peripheral vein phlebitis and pneumonia were frequently related to MSSA-BSI.

Deaths associated with BSI occurred in 81 cases (31.9%) of MRSA-BSI. Of these, 64 were definitely associated with BSI, and 17 were probably associated with BSI. For MSSA-BSI, 12 deaths (14.1%) were definitely associated with BSI. In a subgroup analysis of central-line associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI), 30 of 94 (31.9%) MRSA-BSI patients died, and 27 out of the 30 deaths were definitely associated with SA-BSI.

Of the 254 MRSA-BSI cases, 121 were excluded from matching with control patients for the following reasons: 91 developed BSI after more than 30?days of hospitalization, 16 were under 18?years of age (two patients were both below 18 and developed BSI after more than a month of hospitalization), and 16 could not be matched with appropriate control patients. Of the 85 MSSA-BSI cases, 28 were excluded from the control patient matching: 8 patients developed BSI after more than a month of hospitalization, 9 were under 18 (one patient was both under 18 and developed BSI after more than a month of hospitalization), and 12 patients could not be matched with appropriate controls. At the end of this matching process, 56.0% of the cases were matched with controls. Baseline characteristics, including gender, age (excluding pediatric patients), proportions of CLABSI, and mortality between included and excluded cases were similar in the MRSA and MSSA-BSI groups. The clinical and economic outcomes of the cases and controls shown in Table?2 indicate that the median medical cost of MRSA-BSI was $19,318, about 2.5 times that of controls ($7,092). For the patients with MSSA-BSI, the median medical cost was $8,030 US dollars, almost double the $4,475 US dollars for the control patients.

Table 2.

Clinical and economic characteristics of case and control patients with S. aureus bloodstream infections

| (a) MRSA vs. control | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | MRSA (n?=?133) | Control (n?=?133) | P -value |

| Male gender | 86 (64.7%) | 84 (63.2%) | 0.798 |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 67 (56?76.5) | 68 (56?75) | |

| Died | 49 (36.8%) | 18 (13.5%) | <0.001 |

| Duration of hospitalization (days), mean (SD) | 38.5 (26.8) | 25.8 (28.0) | <0.001 |

| Survivor pairs | 44.5 (29.6) | 25.2 (29.0) | <0.001 |

| Non-survivor pairs | 28.0 (16.5) | 27.1 (26.2) | 0.843 |

| Charlson?s comorbidity index (SD) | 4.92 (2.4) | 4.5 (2.0) | 0.094 |

| Hospital cost ($), median (IQR) | 19,318 (9,852-29,438) | 7,092 (2,864-14,609) | |

| Survivor pairs | 18,699 (9,660-28,369) | 7,440 (3,095-14,907) | |

| Non-survivor pairs | 19,647 (10,812-29,821) | 4,875 (2,551-11,850) | |

| Hospital charge ($), median (IQR) | 4,661 (2,240-7,959) | 2,359 (870?4,128) | |

| Survivor pairs | 4,423 (2,093-8,015) | 2,394 (1,077-4,384) | |

| Non-survivor pairs | 4,763 (2,596-7,930) | 1,841 (626?3,706) | |

| (b) MSSA vs. control | |||

| Characteristic | MSSA (n?=?57) | Control (n?=?57) | P -value |

| Male gender | 26 (45.6%) | 31 (54.4%) | 0.349 |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 63 (51.5-71.5) | 61 (50.5-72.0) | |

| Died | 11 (19.3%) | 4 (7.0%) | 0.052 |

| Duration of hospitalization (days), mean (SD) | 29.4 (20.7) | 18.1 (24.4) | 0.010 |

| Survivor pairs | 31.5 (21.7) | 15.5 (12.9) | <?0.001 |

| Non-survivor pairs | 17.9 (8.7) | 32.8 (56.1) | 0.139 |

| Charlson?s comorbidity index (SD) | 4.8 (2.4) | 4.1 (2.1) | 0.108 |

| Hospital cost ($), median (IQR) | 8,030 (4,998-17,733) | 4,475 (2,714-9,973) | |

| Survivor pairs | 9,247 (4,991-19,564) | 4,449 (2,692-10,090) | |

| Non-survivor pairs | 6,255 (3,952-9,815) | 5,847 (2,151-10,771) | |

| Hospital charge ($), median (IQR) | 2,054 (918?4,753) | 1,517 (669?3,673) | |

| Survivor pairs | 2,056 (845?4,822) | 1,442 (619?3,309) | |

| Non-survivor pairs | 1,713 (1,229-3,041) | 1,855 (723?4,364) |

Abbreviations: MRSA Methicillin-resistant S. aureus, IQR Interquartile range, SD Standard deviation.

The estimated annual incidence of nosocomial SA-BSI

The estimated annual incidence of nosocomial SA-BSI per 1,000 patient-days is shown in Table?3. The estimated annual incidence of MRSA-BSI was 0.12/1,000 patient-days, and that of MSSA-BSI was 0.04/1,000 patient-days. The estimated annual number of nosocomial SA-BSI cases was 2,946 for MRSA and 986 for MSSA. The estimated annual number of deaths was 943 for MRSA-BSI and 139 for MSSA-BSI.

Table 3.

Incidence of nosocomial Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection and estimated annual number of cases nationwide

| Age group | Actual number | Total patient-days for 22 hospitals | Incidence of SA BSI (per 1,000 patient-days) | Total patient-days for 92 hospitals | Estimated annual number of SA-BSI cases | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | ||

| Total | MRSA | 167 | 87 | 254 | 3,273,055 | 2,987,471 | 6,260,525 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 12,865,024 | 11,342,270 | 24,207,293 | 1969 | 991 | 2946 |

| MSSA | 41 | 44 | 85 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 483 | 501 | 986 | |||||||

| 0-9 | MRSA | 6 | 7 | 13 | 389,736 | 292,724 | 682,460 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 1,272,094 | 960,391 | 2,232,485 | 59 | 69 | 128 |

| MSSA | 3 | 5 | 8 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 29 | 49 | 79 | |||||||

| 10-19 | MRSA | 4 | 0 | 4 | 157,139 | 97,236 | 254,375 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 543,108 | 333,271 | 876,379 | 41 | 0 | 41 |

| MSSA | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0 | 10 | 10 | |||||||

| 20-29 | MRSA | 2 | 1 | 3 | 156,072 | 160,269 | 316,341 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 568,594 | 591,027 | 1,159,621 | 22 | 11 | 33 |

| MSSA | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0 | 22 | 22 | |||||||

| 30-39 | MRSA | 8 | 4 | 12 | 208,994 | 291,053 | 500,048 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 804,148 | 1,062,531 | 1,866,679 | 92 | 44 | 134 |

| MSSA | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 35 | 0 | 34 | |||||||

| 40-49 | MRSA | 9 | 8 | 17 | 375,999 | 383,098 | 759,097 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 1,501,241 | 1,464,574 | 2,965,815 | 108 | 92 | 199 |

| MSSA | 4 | 4 | 8 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 48 | 46 | 94 | |||||||

| 50-59 | MRSA | 38 | 10 | 48 | 599,353 | 478,517 | 1,077,870 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 2,392,430 | 1,898,890 | 4,291,320 | 455 | 119 | 573 |

| MSSA | 13 | 9 | 22 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 156 | 107 | 263 | |||||||

| 60-69 | MRSA | 48 | 11 | 59 | 660,593 | 515,558 | 1,176,151 | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 2,774,688 | 2,005,009 | 4,779,697 | 605 | 128 | 719 |

| MSSA | 13 | 9 | 22 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 164 | 105 | 268 | |||||||

| 70-79 | MRSA | 34 | 29 | 63 | 568,375 | 554,828 | 1,123,203 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 2,311,691 | 2,156,892 | 4,468,583 | 415 | 338 | 752 |

| MSSA | 4 | 11 | 15 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 49 | 128 | 179 | |||||||

| >80 | MRSA | 18 | 17 | 35 | 156,794 | 214,188 | 370,981 | 0.34 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 697,029 | 869,686 | 1,566,715 | 240 | 207 | 443 |

| MSSA | 1 | 3 | 4 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 13 | 37 | 51 | |||||||

Abbreviations: MRSA Methicillin-resistant S. aureus, MSSA Methicillin-susceptible S. aureus, SA-BSI S. aureus bloodstream infection.

The estimated additional cost of nosocomial SA-BSI

MRSA

The total estimated additional cost of SA-BSI is shown in Table?4. The additional medical cost for one case of MRSA-BSI was $11,259 in the survivor group and $14,772 in the non-survivor group. The costs of caregiving due to the excess days of hospitalization were $927 and $273 in the survivor and non-survivor groups, respectively. The total additional cost of MRSA-BSI was estimated to be $60,375,506 annually, corresponding to $20,494 per case of MRSA-BSI. Medical costs accounted for 60.4% of the total additional costs, and productivity loss due to premature death for 35.4%.

Table 4.

Estimate of the annual economic burden of nosocomial S. aureus bloodstream infection in South Korea

| MRSA | MSSA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additional cost per patient ($) | Annual number of patients | Additional annual cost ($) | Additional cost per patient ($) | Annual number of patients | Additional annual cost ($) | ||

| Medical cost, median | |||||||

| Survivors | 11,259 | 2003 | 22,551,777 | 4,797 | 847 | 4,063,059 | |

| Non survivors | 14,772 | 943 | 13,929,996 | 408 | 139 | 56,712 | |

| Sub-total | 2946 | 36,481,773 | 986 | 4,119,771 | |||

| Cost of care giving | 986 | ||||||

| Survivors | 927 | 2003 | 1,857,327 | 818 | 847 | 693,000 | |

| Non survivors | 273 | 943 | 257,182 | 0* | 139 | ||

| Subtotal | 2946 | 2,114,509 | 986 | 693,000 | |||

| Productivity loss due to extended hospitalization | |||||||

| Survivors | Male | 187 | 1368 | 255,546 | 165 | 425 | 70,051 |

| Female | 126 | 635 | 80,163 | 111 | 421 | 46,895 | |

| Non survivors | Male | 55 | 601 | 33,020 | 0* | 59 | |

| Female | 37 | 342 | 12,698 | 0* | 80 | ||

| Subtotal | 2946 | 381,428 | 986 | 116,946 | |||

| Productivity loss due to premature death | 943 | 21,397,796 | 139 | 1,887,336 | |||

| Total additional cost of nosocomial SA-BSI | 2946 | 60,375,506 | 986 | 6,817,053 | |||

Abbreviations: MRSA Methicillin-resistant S. aureus, MSSA Methicillin-susceptible S. aureus, SA-BSI S. aureus bloodstream infection.

*Because hospital stays were shorter in the non-survivors in the MSSA group, no additional cost was generated.

MSSA

The additional medical cost of MSSA-BSI was $4,797 in the survivor group and $408 in the non-survivor group. The cost of caregiving due to excess hospitalization was $818 in the survivor group. However, in the non-survivor group, the length of hospital stay was shorter in the SA-BSI group than in the control, and no additional cost was generated. The total additional cost of MSSA-BSI was estimated to be $6,817,053 annually, which corresponds to $6,914 per case of MSSA-BSI. Medical costs accounted for 60.4% of the total additional costs, and productivity loss due to premature death for 27.7%.

Discussion

We set out to determine the annual national financial burden of SA-BSI in South Korea. We estimated that the annual incidence of nosocomial SA-BSI was 0.16/1000 patient-days, and that there were 3,932 cases of nosocomial SA-BSI, resulting in 1,082 fatalities in 2011. We also estimated that the additional medical cost of nosocomial BSI was $12,226 per case of MRSA-BSI and $3,555 per case of MSSA-BSI. The annual economic burden of nosocomial SA-BSI in South Korea was estimated to be?>?$67.2 million, of which medical costs comprised 60.4%. This is the first nationwide nosocomial surveillance data on the clinical and financial burdens from an Asian country.

In a previous study, we reported that the estimated number of invasive S. aureus infection was 21,000 cases in 3 areas of South Korea, and that 55% of them were nosocomial infections [13]. This suggested that the incidence of S. aureus bacteremia was 43.3 per 100,000 person-years. A recent study from a single Korean hospital reported that the incidence of MRSA-BSI was 0.12/1,000 patient-days [17], which is in line with the results of the present study. The Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (K-CDC) collect data on multidrug-resistant organisms via a laboratory-based surveillance system, and 4,153 cases of MRSA-BSI were reported to the K-CDC in 2012 [18], a figure in line with our findings. Unfortunately, KONIS, another surveillance system, collects data on nosocomial infections in intensive care units only, and excluding those at general wards, thus our data are not comparable with those of KONIS [7]. Notably, a Taiwanese study also found that the incidence of SA-BSI was 0.01-0.88/1,000 patient-days [19].

We included only S. aureus in this study, and therefore we could not estimate the incidence of nosocomial BSI of other organisms. S. aureus usually accounts for 10-20% of all causes of nosocomial BSI [20]-[22], and a recent study from South Korea also reported similar results [23]. If we assumed S. aureus comprised 10-20% of nosocomial BSI, the annual number of nosocomial BSI of all organisms could be estimated as range from 19,660 to 39,320 in 2011 in South Korea. As the total number of hospital admissions was 6,453,839 in 2011 [24], approximately 30.5-60.9 per 10,000 admitted patients are estimated to suffer from nosocomial BSI. It is of interest that the estimated burden of BSI is very close to that reported from England, which ranged from 19,202 to 28,804 patients per year [25].

Our matched-control study showed that the additional medical costs were $12,226 and $3,555, for MRSA-BSI and MSSA-BSI, respectively. These are comparable to data from Canada, with additional costs for MRSA-BSI of $6,878 to $17,553 [12],[26]. However, these costs are small compared to the additional costs in the U.S.A of $23,690 to $27,083 for MRSA-BSI and $9,661 to $19,212 for MSSA [8]-[10]. This vast difference in the additional hospital costs is mainly due to differences between the healthcare systems, especially in terms of the medical price-setting, insurance system and reimbursement policy.

Nosocomial SA-BSI imposes a large economic burden on our healthcare system. We found that the additional cost of nosocomial SA-BSI was?>?$67.2 million. This is an enormous burden, but because the proportion SA-BSI contributed to the total burden of nosocomial infections is unknown, we could not estimate the total burden of nosocomial infection. Considering that this study did not include BSI of other organisms and other HAIs such as pneumonia, urinary tract infections and wound infections, HAIs can be understood to impose a huge economic burden on our healthcare system. Studies of the nationwide economic burden of HAIs have been reported for many countries [11],[27]. De Kraker et al. estimated that the increasing burden imposed by antimicrobial-resistant organisms will surpass that of other major diseases. In the U.S.A., the total cost of the 5 major HAIs was $9.8 billion and initiatives are considered essential to reduce HAIs [28]. Our data provide an important foundation for creating a nationwide plan to reduce HAIs.

This study had certain limitations. First, the sampling period was short. We accept that a short sampling period may distort the estimates made, because of seasonal variations in disease incidence, and sampling bias. However, seasonal variations in S. aureus HAIs are less common than are variations in skin and soft tissue infections, community-acquired infections, and in pediatric populations [29],[30]. Many studies have found that nosocomial infection rates do not vary seasonally [31],[32]. We earlier also found that no seasonal variability was evident [13]. In surveillance of K-CDC, monthly variation in incidence of MRSA bacteremia was also not evident [18].

Secondly, because we studied only hospitals with over 500 beds, data on the nosocomial SA-BSI incidence in smaller hospitals were not included. We selected hospitals that employed infectious disease specialists, because each SAB case was required to be reviewed by such a specialist. In South Korea, more than 90% of infectious diseases specialists work in university-affiliated hospitals or large hospitals (over 500 beds), and we thus could not include medium-sized and small hospitals in our study. As it is not known whether the incidence of HAIs in small or medium-sized hospitals is higher or lower than that in large hospitals, our data cannot be extrapolated to hospitals with less than 500 beds. According to data provided by the multidrug-resistant organism surveillance system in South Korea, cases of MRSA-BSI in hospitals with 300?499 beds account for 11.7% of all cases. Therefore, considering the extent of nosocomial SA-BSI in hospitals with 500 beds or less, we estimate that more than 10-20% of all SA-BSI cases were omitted in our estimations, and, hence, the calculated cost may be at the lower end of the real nationwide figure.

Conclusion

In conclusion, approximately 3,932 cases of nosocomial SA-BSI occurred in 2011 in the South Korean hospitals surveyed (those with 500 or more beds), and 1,082 patients died. The economic burden of nosocomial SA-BSI exceeded $67.2 million. A national strategy to reduce such infections featuring a campaign to improve hand hygiene practice, dissemination of bundle approach when managing central catheter, and periodic estimation of the burden of such infections, is urgently needed.

Authors? contributions

CJ-K, HB-K, KH-S, ES-K, and M-O designed the study protocol; HB-K, YK-C, YH-C, JY-P, BN-K, NJ-K, KH-K, EJ-L, JB-J, YK-K, S-K, HJ-C, EJ-C, KM-S, S-L, HH-C, JH-B, SJ-L, JH-L, SY-P, MH-J and NR-Y collected the data of each participating hospital; YH-K, AR-K, SH-O performed statistical analysis and estimation; M-O managed the overall research process; CJ-K and HB-K prepared the initial draft of the manuscript; M-O revised the manuscript and finalized it; all authors were involved in manuscript review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participating hospitals and the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA) for generously providing data. The authors are also indebted to J. Patrick Barron, Professor Emeritus, Tokyo Medical University and Adjunct Professor Seoul National University Bundang Hospital for his editing of the manuscript.

Funding source

This work was supported by the National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency (NECA) of Korea (NM11-002).

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Footnotes

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Chung-Jong Kim, Email: erinus00@gmail.com.

Hong-Bin Kim, Email: ksbkhb@chollian.net.

Myoung-don Oh, Email: mdohmd@snu.ac.kr.

Yunhee Kim, Email: yuni@neca.re.kr.

Arim Kim, Email: arimkim03@neca.re.kr.

Sung-Hee Oh, Email: dhepd@neca.re.kr.

Kyoung-Ho Song, Email: khsongmd@gmail.com.

Eu Suk Kim, Email: yonathan@hanafos.com.

Yong Kyun Cho, Email: karmacho@gmail.com.

Young Hwa Choi, Email: yhwa1805@ajou.ac.kr.

Jinyong Park, Email: twsjy@naver.com.

Baek-Nam Kim, Email: griuni@chol.com.

Nam-Joong Kim, Email: molder@unitel.co.kr.

Kye-Hyung Kim, Email: kyehyungs@gmail.com.

Eun Jung Lee, Email: shegets@schmc.ac.kr.

Jae-Bum Jun, Email: uvgotletter@hanmail.net.

Young Keun Kim, Email: amoxj@yonsei.ac.kr.

Sung min Kiem, Email: smkimkor@paik.ac.kr.

Hee Jung Choi, Email: heechoi@ewha.ac.kr.

Eun Ju Choo, Email: mdchoo@schmc.ac.kr.

Kyung-mok Sohn, Email: medone@cnuh.co.kr.

Shinwon Lee, Email: ebenezere.lee@gmail.com.

Hyun Ha Chang, Email: changhha@knu.ac.kr.

Ji Hwan Bang, Email: roundbirch@gmail.com.

Su Jin Lee, Email: beauty192@hanmail.net.

Jae Hoon Lee, Email: john7026@wonkwang.ac.kr.

Seong Yeon Park, Email: psy99ch@hanmail.net.

Min Hyok Jeon, Email: yacsog@schmc.ac.kr.

Na Ra Yun, Email: shine-0222@hanmail.net.

References

- 1.Herwaldt LA, Cullen JJ, Scholz D, French P, Zimmerman MB, Pfaller MA, Wenzel RP, Perl TM. A prospective study of outcomes, healthcare resource utilization, and costs associated with postoperative nosocomial infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2006;27(12):1291–1298. doi: 10.1086/509827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noskin GA, Rubin RJ, Schentag JJ, Kluytmans J, Hedblom EC, Jacobson C, Smulders M, Gemmen E, Bharmal M. National trends in staphylococcus aureus infection rates: impact on economic burden and mortality over a 6-year period (1998?2003) Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(9):1132–1140. doi: 10.1086/522186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO: Report on the burden of endemic health care-associated infection worldwide. 2011, 1-34.

- 4.Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati G, Kainer MA, Lynfield R, Maloney M, McAllister-Hollod L, Nadle J, Ray SM, Thompson DL, Wilson LE, Fridkin SK. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(13):1198–1208. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klevens RM, Edwards JR, Richards CL, Jr, Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Pollock DA, Cardo DM. Estimating health care-associated infections and deaths in U.S. hospitals, 2002. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(2):160–166. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haley RW, Culver DH, White JW, Morgan WM, Emori TG. The nationwide nosocomial infection rate. A new need for vital statistics. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121(2):159–167. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeon MH, Park WB, Kim SR, Chun HK, Han SH, Bang JH, Park ES, Jeong SY, Eom JS, Kim YK. Korean nosocomial infections surveillance system, intensive care unit module report: data summary from July 2010 through June 2011. Korean J Nosocomial Infect Control. 2012;17(1):28–39. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abramson MA, Sexton DJ. Nosocomial methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible staphylococcus aureus primary bacteremia: at what costs? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20(6):408–411. doi: 10.1086/501641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ben-David D, Novikov I, Mermel LA. Are there differences in hospital cost between patients with nosocomial methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection and those with methicillin-susceptible S. Aureus bloodstream infection? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30(5):453–460. doi: 10.1086/596731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cosgrove SE, Qi Y, Kaye KS, Harbarth S, Karchmer AW, Carmeli Y. The impact of methicillin resistance in staphylococcus aureus bacteremia on patient outcomes: mortality, length of stay, and hospital charges. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26(2):166–174. doi: 10.1086/502522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Kraker ME, Davey PG, Grundmann H. Mortality and hospital stay associated with resistant staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli bacteremia: estimating the burden of antibiotic resistance in Europe. PLoS Med. 2011;8(10):e1001104. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goetghebeur M, Landry PA, Han D, Vicente C. Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus: a public health issue with economic consequences. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2007;18(1):27–34. doi: 10.1155/2007/253947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song KH, Kim ES, Sin HY, Park KH, Jung SI, Yoon N, Kim DM, Lee CS, Jang HC, Park Y, Lee KS, Kwak YG, Lee JH, Park SY, Song M, Park SK, Lee YS, Kim HB. Characteristics of invasive staphylococcus aureus infections in three regions of Korea, 2009?2011: a multi-center cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:581. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim CY. Health technology assessment in South Korea. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2009;25(Suppl 1):219–223. doi: 10.1017/S0266462309090667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harbarth S, Rutschmann O, Sudre P, Pittet D. Impact of methicillin resistance on the outcome of patients with bacteremia caused by staphylococcus aureus. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(2):182–189. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.2.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horan TC, Emori TG. Definitions of key terms used in the NNIS system. Am J Infect Control. 1997;25(2):112–116. doi: 10.1016/S0196-6553(97)90037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim YC, Kim MH, Song JE, Ahn JY, Oh DH, Kweon OM, Lee D, Kim SB, Kim HW, Jeong SJ, Ku NS, Han SH, Park ES, Yong D, Song YG, Lee K, Kim JM, Choi JY. Trend of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteremia in an institution with a high rate of MRSA after the reinforcement of antibiotic stewardship and hand hygiene. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(5):e39–e43. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Disease web statistics system. [], [http://stat.cdc.go.kr/]

- 19.Liu CY, Liao CH, Chen YC, Chang SC. Changing epidemiology of nosocomial bloodstream infections in 11 teaching hospitals in Taiwan between 1993 and 2006. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2010;43(5):416–429. doi: 10.1016/S1684-1182(10)60065-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyytikainen O, Lumio J, Sarkkinen H, Kolho E, Kostiala A, Ruutu P. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in Finnish hospitals during 1999?2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(2):e14–e19. doi: 10.1086/340981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marra AR, Camargo LF, Pignatari AC, Sukiennik T, Behar PR, Medeiros EA, Ribeiro J, Girao E, Correa L, Guerra C, Brites C, Pereira CA, Carneiro I, Reis M, de Souza MA, Tranchesi R, Barata CU, Edmond MB. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in Brazilian hospitals: analysis of 2,563 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(5):1866–1871. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00376-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wisplinghoff H, Bischoff T, Tallent SM, Seifert H, Wenzel RP, Edmond MB. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(3):309–317. doi: 10.1086/421946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Son JS, Song JH, Ko KS, Yeom JS, Ki HK, Kim SW, Chang HH, Ryu SY, Kim YS, Jung SI, Shin SY, Oh HB, Lee YS, Chung DR, Lee NY, Peck KR. Bloodstream infections and clinical significance of healthcare-associated bacteremia: a multicenter surveillance study in Korean hospitals. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25(7):992–998. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.7.992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korean Statistical Information Service, (KOSIS). [], [http://kosis.kr/statisticsList/statisticsList_01List.jsp?vwcd=MT_ZTITLE&parentId=D]

- 25.Goto M, Al-Hasan MN. Overall burden of bloodstream infection and nosocomial bloodstream infection in North America and Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19(6):501–509. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim T, Oh PI, Simor AE. The economic impact of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus in Canadian hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2001;22(2):99–104. doi: 10.1086/501871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graves N, Nicholls TM, Morris AJ. Modeling the costs of hospital-acquired infections in New Zealand. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24(3):214–223. doi: 10.1086/502192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zimlichman E, Henderson D, Tamir O, Franz C, Song P, Yamin CK, Keohane C, Denham CR, Bates DW. Health care-associated infections: a meta-analysis of costs and financial impact on the US health care system. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(22):2039–2046. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mermel LA, Machan JT, Parenteau S. Seasonality of MRSA infections. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leekha S, Diekema DJ, Perencevich EN. Seasonality of staphylococcal infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(10):927–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klein EY, Sun L, Smith DL, Laxminarayan R. The changing epidemiology of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus in the united States: a national observational study. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177(7):666–674. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perencevich EN, McGregor JC, Shardell M, Furuno JP, Harris AD, Morris JG, Jr, Fisman DN, Johnson JA. Summer peaks in the incidences of gram-negative bacterial infection among hospitalized patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(12):1124–1131. doi: 10.1086/592698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]