Abstract

Disrupted-In-Schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) is a genetic risk factor that has been implicated in major mental disorders. DISC1 binds to and stabilizes serine racemase (SR) to regulate production of D-serine by astrocytes, contributing to glutamate (GLU) neurotransmission. However, the possible involvement of astrocytic DISC1 in synthesis, metabolism, re-uptake or secretion of GLU remains unexplored. Thus, we studied the effects of dominant-negative mutant DISC1 on various aspects of GLU metabolism using primary astrocyte cultures and the hippocampal tissue from transgenic mice with astrocyte-restricted expression of mutant DISC1. While mutant DISC1 had no significant effects on astrocyte proliferation, GLU re-uptake, Glutaminase or Glutamate carboxypeptidase II activity, expression of mutant DISC1 was associated with increased levels of alanine-serine-cysteine transporter 2, vesicular glutamate transporters 1 and 3 in primary astrocytes and in the hippocampus as well as elevated expression of the NR1 subunit and diminished expression of the NR2A subunit of NMDA receptors in the hippocampus at postnatal day 21. Our findings indicate that decreased D-serine production by astrocytic mutant DISC1 may lead to compensatory changes in levels of the amino acid transporters and NMDA receptors in the context of tripartite synapse.

Keywords: glutamate uptake, VGLUT, ASCT2, D-serine, NMDA, psychiatric disease

Introduction

There is a growing body of evidence demonstrating the role for astrocytes in regulating glutamate (GLU) neurotransmission at synapses via the release of so-called “gliotransmitters”, including GLU, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and D-serine (Hamilton and Attwell, 2010; Parpura, 2012; Clarke and Barres, 2013). These findings indicate that astrocytes critically influence N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-mediated plasticity (Bernstein, 2009; Bergeron and Coyle, 2012), abnormalities in which have been implicated in the pathobiology of major mental disorders (Rajkowska and Stockmeier, 2013; Sanacora and Banasr, 2013; Takahashi and Sakurai, 2013).

Recent progress in psychiatric genetics has advanced our understanding of how genetic risk factors affect neurodevelopment and adult brain functions (Sullivan, 2012). However, the majority of studies have focused on neurons and very few attempts have been made to elucidate the functions of “psychiatric” genes in glial cells despite the increasing evidence for the key roles of glial cells in mental disease (Kondziella, 2007; Schnieder et al, 2010). Thus, we have recently begun studying the role(s) of Disrupted-In-Schziophrenia-1 (DISC1) in astrocytes that also express this gene in the mouse and human brains (Seshadri, 2010; Kuroda, 2011; Ma, 2013).

Our previous publication have reported that DISC1 binds to and stabilizes serine racemase (SR), the enzyme that converts L-serine to D-serine (Ma, 2013). We have also shown that selective expression of a mutant form of DISC1, C-terminus truncated DISC1, disrupts this interaction via a dominant-negative mechanism by binding of mutant DISC1 to endogenous mouse DISC1 in astrocytes. Importantly, this pathogenic disruption leads to increased degradation of SR via increased ubiquitination and a subsequent decrease in production of D-serine by astrocytes. No such effects have been observed in neurons that selectively express mutant DISC1. Astrocyte-restricted expression of mutant DISC1 in transgenic mice leads to schizophrenia-like behavioral alterations reversible with D-serine treatment (Ma, 2013).

However, specificity of the effects of mutant DISC1 on D-serine production was not evaluated in great detail in the prior study. Indeed, over-expression of mutant DISC1 could also affect other astrocytic functions. Thus, the main goal of the current study was to characterize the effects of mutant DISC1 on the major astrocytic markers, transporters, receptors and various aspects of GLU metabolism. We found no significant effects of mutant DISC1 on astrocyte proliferation, expression of protein S100, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), or aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family, member L1 (ADH1L1). No alterations were found in GLU reuptake or expression of glial glutamate transporter 1 (GLT-1), glutamate aspartate transporter (GLAST) or metabotropic GLU receptor 3 or 5. No changes were detected in the protein levels of 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase or glycine transporter-1 (GlyT1) involved in L-serine synthesis and transport of glycine (a co-agonist of D-serine at NMDAR), respectively.

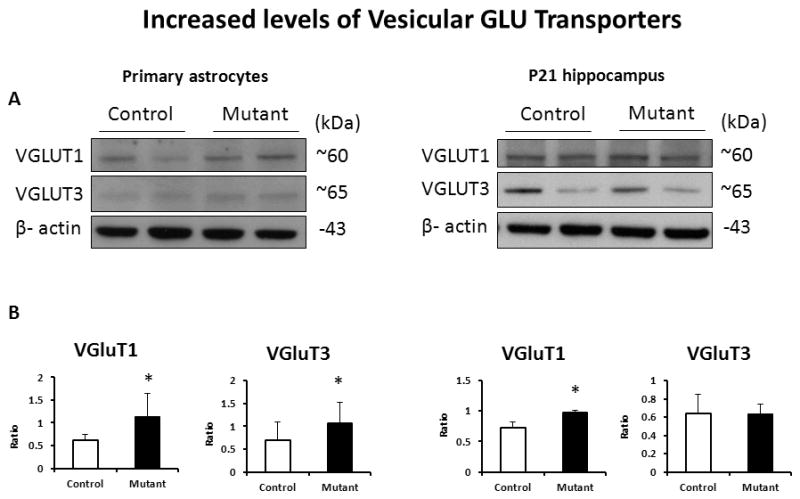

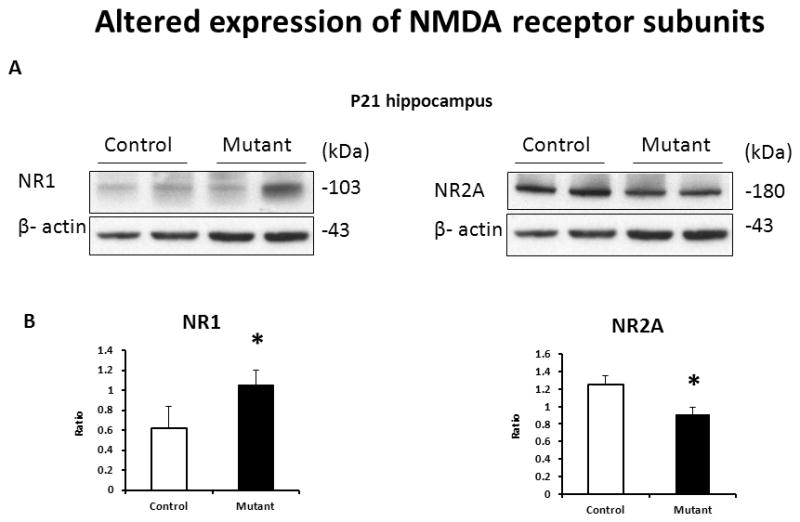

In contrast, expression of mutant DISC1 resulted in a significant elevation of protein levels of vesicular GLU transporters 1 and 3 (VGLUT1 and VGLUT3) in vitro and VGLUT1 in the hippocampus. In addition, there were increased levels of the NR1 subunit and decreased levels of the NR2A subunit of NMDAR in the hippocampus of transgenic mice at postnatal day 21. Our findings provide new evidence that astrocytic mutant DISC1 may affect GLU neurotransmission.

Materials and Methods

Tet-off transgenic model

In order to express mutant DISC1 in astrocytes, we mated single hemyzygous transgenic GFAP-tTA mice (Jackson Lab line 110, B6.Cg-Tg(GFAP-tTA)110Pop/J and 67, a kind gift by Brian Popko, University of Chicago) with single homozygous transgenic TRE-mutant DISC1 mice (lines 1302 and 1001) as described previously (Ma, 2013). This mating protocol produces litters that have about 50% of single transgenic mutant DISC1 mice that do not express mutant DISC1 (control mice) and ~50% of double transgenic mice that express mutant DISC1 (mutant mice). Tail tissue samples were used to determine the genotype of mouse pups to be used for preparing primary cultures or juvenile mice to be used for biochemical studies at postnatal day 21 (P21) as previously described (Pletnikov, 2008). Developing mice were housed with their dams until P21 with food and water ad libidum. All procedures were approved by the JHU Animal Care and Use Committee.

Primary astrocytes cultures

Primary astrocyte cultures were prepared as previously described (Ma, 2013). Briefly, primary astrocyte cultures were derived from the forebrains of neonatal (postnatal day 1–3) mice. Whole brains were placed in D-PBS with 0.1% penicillin-streptomycin reagent (Sigma-Aldrich), and the olfactory bulbs and meninges removed. The cerebral tissues were trypsinized (0.05% trypsin EDTA) and incubated for 20 min at 37 °C with periodic vigorous shaking. Cultures were cultured in a humidified atmosphere of 5%CO2/95% air at 37 °C, with media changes every 2–3 days. Live cells were used for the proliferation assay. Cell pellets were collected for biochemical experiments.

Proliferation assay

Analysis of astrocyte proliferation in vitro was performed according to the standard protocol (Guizzetti, 2011). Briefly, astrocytes were plated at 10x104 cells/well in 24-well plates. Three days after plating, cell culture medium was replaced with the medium containing 10 μM BrdU labeling reagent (Cat# 00-0103; Life technologies) for 24 hours. Culture were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed in PBS, blocked in 5% goat serum and then incubated with rat monoclonal anti-BrdU (Accurate #OBT-0030, clone BU1/75; 1:1000 dilution) overnight at 4°C, followed by additional washes and 2-hr room temperature incubation with CyTM3-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (Lot number: 108067; Jackson Labs, 1:500 dilution) and co-stained with Hoechest. The index of proliferating cells in S-phase was calculated as the ratio of BrdU+ cells to Hoechest+ cells for each individual culture.

Western blotting

In order to measure expression of various astrocytic markers, primary astrocyte cultures or the hippocampus were used. For the brain tissue, control and mutant mice were euthanized at P21, their hippocampi and frontal cortices (for GLU uptake only) were isolated, frozen on dry ice and kept at −80°C until used. These samples were assayed for expression of multiple markers as presented in Table 1 using the standard western blotting procedure (Ma, 2013). The optical density (O.D.) of protein bands on each digitized image was normalized to the O.D. of the loading control (β-actin, 1:20000, Sigma-Aldrich, MO). Densitometry was done using ImageJ software. Normalized values were used for analyses.

Table 1.

Antibodies used information

| Marker | Primary* | Secondary ** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3PGDH | Mouse (6B2): sc-100317; 1:200 | Santa Cruz | NA931V |

| β-Actin | Mouse (A5316); 1:20000 | Sigma-Aldrich | NA931V |

| β-Tubulin | Mouse (T4026); 1:20000 | Sigma-Aldrich | NA931V |

| ALDH1 | Mouse (75-140); 1:2000 | NeuroMab | NA931V |

| ASCT2 | Rabbit (V501) #5345; 1:1000 | Cell Signl. | NA934V |

| GFAP | Mouse (MA5-15086); 1:2000 | Thermo Sci. | NA931V |

| GLAST | Rabbit; 1:300 | Rothstein Lab | NA934V |

| GLT1 | Mouse; 1:5000 | Rothstein Lab | NA931V |

| GlyT1 | Rabbit (ab113823); 1:1000 | Abcam | NA934V |

| mGluR3 | Rabbit (bs-1237R); 1:300 | Bioss Inc. | NA934V |

| mGluR5 | Rabbit (PA5-13361); 1:100 | Thermo Sci. | NA934V |

| NR1 | Mouse (32-0500); 1:1000 | Life Technolog. | NA931V |

| NR2A | Rabbit (PPS012); 1:2000 | R&D System | NA934V |

| S100 | Rabbit (ab52642); 1:1000 | Abcam | NA934V |

| VGLUT1 | Rabbit (500-560); 1:500 | Osenses | NA934V |

| VGLUT3 | Rabbit (ab23977); 1:2000 | Abcam | NA934V |

Animal source, catalog number and dilution

All secondary antibodies are from GE Healthcare, dilution used was 1:2000

GCPII enzymatic activity

Glutamate carboxypeptidase II (GCPII) activity measurements were carried out following published procedures (Robinson, 1987; Rojas, 2002). Briefly, the reaction mixture contained [3H]-NAAG (70 nM, 51 Ci/mmol) and cell membrane preparations from control and mutant DISC1 cells as source of GCPII in Tris-HCl containing 1 mM CoCl2 in a total volume of 50 μL. The reaction was carried out at 37 °C for 2 h and stopped with an equal volume of ice-cold sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4, 0.1 M). Reactions were carried out in the presence and absence of the selective GCPII inhibitor 2-PMPA (1 μM). [3H]-NAAG was separated from [3H]-glutamate by strong ion exchange chromatography (AG1X8); [3H]-NAAG bound to the resin and [3H]-glutamate eluted in the flow through. Columns were then washed twice with formate (1 M, 90 μL) to ensure complete elution of [3H]-glutamate. The radioactivity of [3H]-glutamate was determined and used as a measure of GCPII activity.

Glutaminase enzymatic activity

Measurement of glutaminase activity was adapted from previous reports in the literature (Collins, 1994; Seltzer, 2010). The reaction mixture contained [3H]-glutamine (2 mM, 0.091 μCi) and astrocyte lysates as source of glutaminase in potassium phosphate buffer (pH 8.2, 45 mM) in a total volume of 50 μL. The hydrolysis reaction was carried out for 90 min and it was terminated with imidazole (pH 7, 100 μL). [3H]-glutamine was separated from [3H]-glutamate using strong anion-exchange chromatography (BIO RAD, AGR 1-X2 Resin 200–400 mesh Cl form). The [3H]-glutamine fraction was first eluted from the column with imidazole (400 μL); [3H]-glutamate was then eluted after the addition of 400 μL HCl (0.1 N). The radioactivity of [3H]-glutamate was determined and used as a measure of glutaminase activity.

Glutamate uptake in primary cultures

Cultured astrocytes were washed, followed by a pre-incubation at RT for 10 min in Na+ buffer (5mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 10mM HEPES, 140mM NaCl, 2.5mM KCl, 1.2mM CaCl2, 1.2mM MgCl2, 1.2mM K2HPO4, and 10mM D-glucose). Glutamate uptake measurements were initiated by incubating the cells for 5 minutes at 37°C in Na+ buffer containing 0.5 μM L-glutamate and 0.3 μCi L-[3H]glutamate (PerkinElmer) per sample (glutamate ratio cold:radioactive=99:1). The cells were quickly moved onto ice and rapidly washed twice with ice-cold glutamate-free Na+-free assay buffer (5mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 10mM HEPES, 140mM Choline-Cl, 2.5mM KCl, 1.2mM CaCl2, 1.2mM MgCl2, 1.2mM K2HPO4, and 10mM D-glucose). Cells were lysed with 0.1N NaOH solution and [3H] radioactivity was measured using a scintillation counter. Radioactive counts were normalized to total protein levels as determined by Bradford method.

Glutamate uptake in crude synaptosomes

Mouse hippocampal tissues were homogenized in ice-cold 0.32M sucrose solution. The tissue lysate was first centrifuged at 800 x g for 10min, followed by a centrifugation at 20,000 x g for 20min at 4°C. Cell pellets were washed in 0.32M sucrose, re-centrifuged and re-suspended in ice-cold 0.32M sucrose. Glutamate uptake was initiated by adding synaptosomes in Na+ buffer (5mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 10mM HEPES, 140mM NaCl, 2.5mM KCl, 1.2mM CaCl2, 1.2mM MgCl2, 1.2mM K2HPO4, and 10mM D-glucose) containing 0.5 μM L-glutamate and 0.075 μCi L-[3H]glutamate (PerkinElmer; glutamate ratio cold:radioactive=99:1) per sample and incubated for 3 minutes at 37°C. The uptake was stopped by quickly adding four volumes of ice-cold glutamate-free Na+-free buffer (5mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 10mM HEPES, 140mM Choline-Cl, 2.5mM KCl, 1.2mM CaCl2, 1.2mM MgCl2, 1.2mM K2HPO4, and 10mM D-glucose). The synaptosome lysate was filtered through a Brandel Harvester and washed with Na+-free assay buffer. The filter paper (containing the labeled synaptosomes) was transferred into scintillation vials and radioactivity was measured using a scintillation counter. Radioactive counts were normalized to total protein levels as determined by Bradford method.

Statistical analyses

Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (±SEM). Individual cultures derived from individual newborn mouse pups or individual brain samples from either group were used as a unit for statistical analyses. The effects of mutant DISC1 on expression of various markers in the western blotting experiments were analyzed with two-tailed Student t-test or Wilcoxon non-parametric test, if normal distribution test failed. P<0.05 was used for the significance level.

Results

Mutant DISC1 does not affect major markers of astrocyte functioning

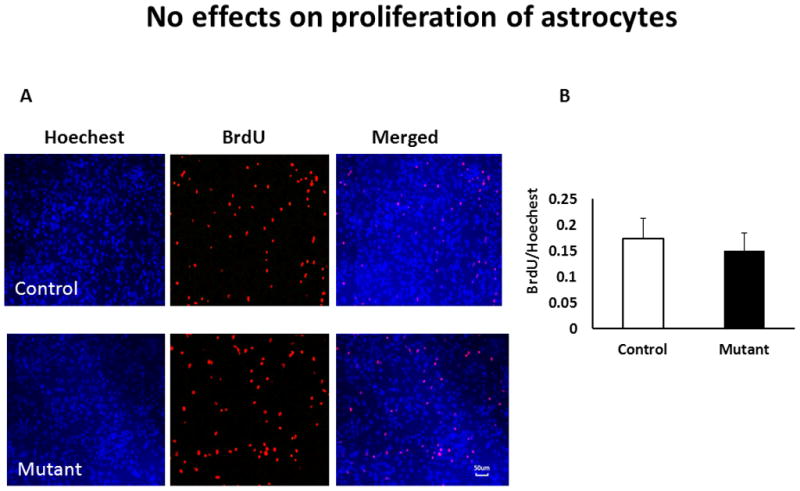

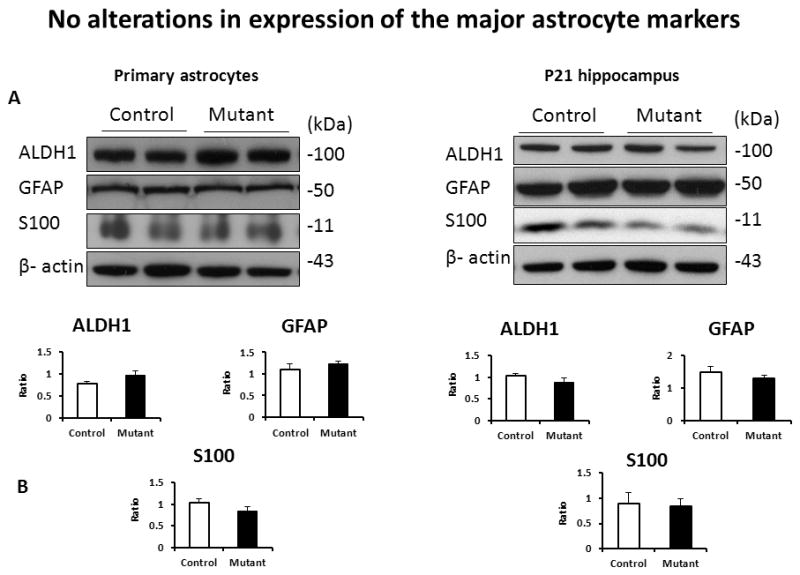

Neuronal DISC1 has been found to affect neuronal proliferation (Duan, 2007; Enomoto, 2009; Mao, 2009). Thus, we evaluated the effects of mutant DISC1 on astrocytes proliferation in vitro. We observed no significant changes in the relative number of BrdU+ cells in control vs. mutant cultures (Fig 1). Analyses of expression of major astrocytic markers demonstrated no significant alterations in protein levels of GFAP, S100 or ADH1L1 in culture or in the hippocampus of transgenic mice at P21 (Fig 2).

Figure 1. No effects of mutant DISC1 on astrocyte proliferation.

A - representative images of control (upper panels) and mutant (bottom panels) primary astrocytes; blue - Hoechest nuclear staining, red – BrdU;

B - quantitative analysis of BrdU+ cells in cultures, n=7/group

Figure 2. No changes in expression of the major astrocytic markers.

A-representative images of western blots for primary astrocytes (left) and the hippocampal tissue (right);

B - quantitative analyses of expression, n=4–6/group

Mutant DISC1 does not affect glutamate metabolism

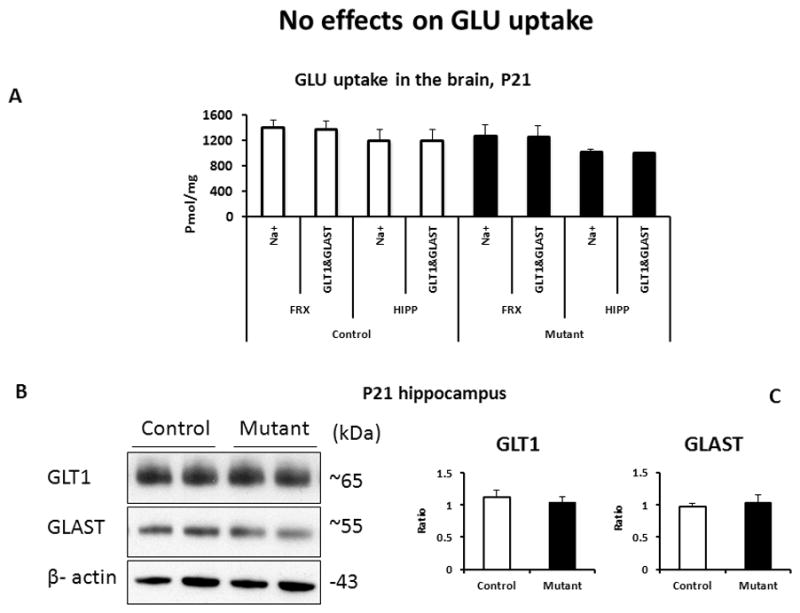

One of the major functions of astroglia is to regulate extracellular concentrations of GLU using transporter proteins present in the plasma membranes (Danbolt, 2001). The transporter proteins represent the primary mechanism for removal of GLU to maintain low and non-toxic concentrations of this neurotransmitter (Sattler and Rothstein, 2006). Thus, we measured GLU uptake and expression of two main GLU transporters, GLT-1 and GLAST, in primary astrocytes and the brain. We found no significant changes in the transporters-dependent or Na+-dependent GLU uptake (Fig 3). Consistently, unaltered GLU uptake was associated with lack of significant changes in expression of GLU transporters, GLT-1 and GLAST in vitro (SFig 1) or in the hippocampus at P21 (Fig 3).

Figure 3. No alterations in GLU uptake.

A- quantitative analysis of GLU uptake in the brain tissues; n=4–6/group; FRX – frontal cortex, HIPP – hippocampus;

B - representative images of expression of GLT-1 and GLAST in the hippocampus at P21;

C - quantitative analyses of expression, n=4–6/group

Glutamate carboxypeptidase II (GCPII) and glutaminase are the enzymes involved in the synthesis of GLU. GCPII influences GLU levels by cleaving N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG) to GLU and N-acetylaspartate (NAA) (Bergeron and Coyle, 2012), while Glutaminase generates GLU from glutamine (Schousboe, 2013). We found no significant alterations in the enzymatic activities of these two enzymes (SFig 2). GLU secreted by neurons in the extracellular space acts on metabotropic GLU receptors (mGluRs) expressed on astrocytes to regulate GLU turnover via negative and positive feedbacks (Haydon, 2009; Durand, 2012). Thus, we assessed expression of mGluR3 and 5 in vitro and in the hippocampus at P21. No significant effects of mutant DISC1 on expression of mGluR3 or mGluR5 were detected (SFig 3).

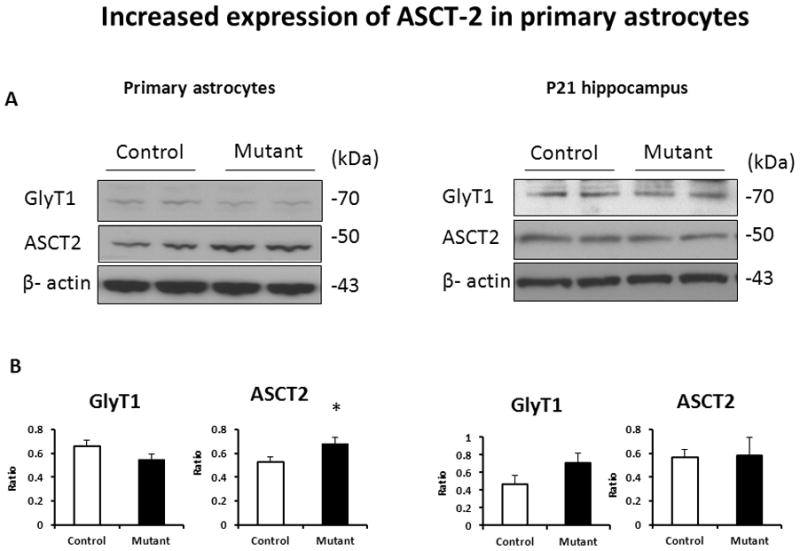

Mutant DISC1 alters expression of vesicular glutamate transporters

As expression of mutant DISC1 did not alter GLU uptake, we analyzed the effects of mutant DISC1 on levels of the glial transporters involved in GLU and D-serine metabolism, focusing on the glycine transporter 1 (GlyT1), the neutral amino acid transporter 2 (ASCT2), and the vesicular glutamate transporter 1 and 3 (VGLUT1 and 3). VLGUTs have been shown to be expressed on astrocytes and neurons (Montana, 2004; Ni, 2009). In addition, we assessed expression of 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (3PGDH), the initial step enzyme for de novo L-serine biosynthesis in animal cells (Wolosker, 2011). While we did not find significant alterations in expression of GlyT1 or 3PGDH, (Fig 4 and SFig 4), there was a significant increase in the protein levels of ASCT2 (Fig 4), VGLUT1 and VGLUT3 in vitro and VGLUT1 in the hippocampus at P21 (Fig 5).

Figure 4. Increased expression of ASCT2 in primary astrocytes.

A - representative western blot images for primary astrocytes (left) and the hippocampal tissue (right);

B - quantitative analyses of expression; n=4–6/group, * denotes p<0.05; Student test

Figure 5. Increased levels of VGLUTs.

A - representative western blot images for primary astrocytes (left) and the hippocampal tissue (right);

B - quantitative analyses of expression; n=4–6/group, * denotes p<0.05; Student t-test

Altered expression of NMDA receptors in the hippocampus

Based on our published results on decreased D-serine levels in the brain of transgenic mice (Ma, 2013) and the observed changes in expression of VGLUTs, we examined expression of NMDA receptors in the hippocampus of mutant DISC1 mice. We found significantly increased levels of the NR1 subunit and significantly decreased levels of the NR2A subunit of NMDAR in the hippocampus at P21 (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Altered expression of NMDAR subunits in the hippocampus.

A - representative western blot images of the hippocampal tissue samples;

B - quantitative analyses of expression; n=4–6/group, * denotes p<0.05; Student t-test

Discussion

Our prior report has demonstrated the involvement of astrocytic DISC1 in regulation of D-serine production via stabilizing serine racemase (Ma et al, 2013). However, other major functions of astrocytes, including glutamate (GLU) uptake, were not evaluated in that study even if it is quite possible that mutant DISC1 could have additional effects in astrocytes. Thus, the main goal of the present study was to examine the putative effects of mutant DISC1 on various aspects of GLU metabolism in astrocytes. We found that mutant DISC1 did not affect GLU uptake but significantly increased expression of ASCT2, VGLUT1 and 3 in primary astrocytes as well as increased levels of VGLUT1 and the NR1 subunit and decreased expression of the NR2A subunit in the hippocampus of transgenic mice at postnatal day 21.

Our prior study demonstrates that DISC1 binds to SR to stabilize it and influence production of D-serine (Ma, 2013). For unknown yet reasons, it appears that DISC1-SR interaction takes place predominantly in astrocytes although neurons harbor the major pool of the enzyme (Wolosker, 2011; Balu, 2013; Wolosker and Radzishevsky, 2013). The present study sought to evaluate specificity of the effect of mutant DISC1 on SR and D-serine using the same Tet-off model. Specifically, we evaluated different aspects of GLU metabolism in astrocytes that selectively express mutant DISC1.

Our findings are consistent with the prior results that expression of mutant DISC1 in astrocytes is not linked to alterations in levels of the main astrocytic markers, including GFAP, ADH1L1 or S100 (Ma, 2013), indicating that the changes related to D-serine production were unlikely a result of global non-specific effects of mutant DISC1. Our present study extends the prior data to show no significant changes in proliferation of primary astrocytes. This result seems in disagreement with the role of DISC1 in neurogenesis. For example, over-expression of mutant DISC1 or knockdown of endogenous DISC1 in developing cortex and adult hippocampus accelerate proliferation of neuronal progenitors (Duan, 2007; Mao, 2009). The finding that astrocytic DISC1 does not seem to significantly influence the proliferating activity of primary astrocytes could be an example of cell type-specific functions of DISC1. Although we did not observe decreased expression of the astrocytic markers in the brain tissue either, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that mutant DISC1 might alter astrocytogenesis in vivo. Future studies will address this possibility.

One of the main functions of astrocytes is to regulate levels of GLU in extracellular milieu to influence GLU neurotransmission, including prevention of potential GLU excitotoxicity (Danbolt, 2001; Sattler and Rothstein, 2006). We found no significant alterations in GLU uptake or expression of glutamate transporters, GLT-1 or GLAST, in primary astrocytes or the hippocampus. In addition, no significant changes were found in the activity of two enzymes involved in synthesis of GLU, glutaminase and GCPII, suggesting that expression of mutant DISC1 does not affect these stages of GLU turnover at the neuron-astrocyte interface (Schousboe and Waagepetersen, 2005; Rose, 2013).

Astrocytes have been shown to utilize exocytosis to influence bi-directional communication with neurons (Parpura and Zorec, 2010). This process requires vesicles containing gliotransmitters. Astrocytes have been demonstrated to have vesicles that contain releasable amino acids (GLU or D-serine) (Parpura, 2010). The uptake of GLU into vesicles is carried out by vesicle membrane bound proteins, VGLUTs. Although there are conflicting data, it has been demonstrated that astrocytes express all the three isoforms of VGLUT (1,2,3) (Parpura, 2012). We found that mutant DISC1 significantly increased levels of VGLUT 1 and 3 in astrocytes and VGLUT1 in the brain tissue where the transporter can be expressed by neurons and astrocytes (Parpura, 2012). Although more research is clearly needed to further clarify these alterations, it is tempting to speculate that the observed changes might be related to decreased production of D-serine as a result of disrupted SR-DISC1 binding. Alternatively, altered expression of VGLUT1 could be a consequence of direct effects of mutant DISC1. These and other options will be explored in the future studies. Notably, both increased and decreased expression of mRNA for VGLUTs were found in major psychiatric disorders (Talbot, 2004; Eastwood and Harrison, 2005; Uezato, 2009; Varea, 2012).

The Na+-dependent ASCT1 and ASCT2 and the Na+-independent alanine–serine–cysteine transporter-1 (Asc-1) regulate D-serine concentrations by catalyzing amino acid exchange: D-serine vs. a neutral amino acid (Fukasawa, 2000; Ribeiro, 2002; Rosenberg, 2013). ASCT2 transporter could partially account for transport of D-serine in astrocyte cultures and C6 glioma cells (Ribeiro, 2002). The glia–neuron D-serine shuttle is suggested to play a leading role in D-serine turnover (Wolosker, 2011). It is not impossible that increased expression of ASCT2 in primary astrocytes may be a compensatory response to decreased D-serine production (Ma, 2013). However, as we did not evaluate dependence of D-serine uptake on the activity of this transporter and we did not analyze D-serine trafficking in vivo, one should treat these results with caution. Moreover, it is conceivable that the observed changes in ASCT2 expression are not related to D-serine metabolism but are a result of direct effects of mutant DISC1 on ASCT2. There are very few studies of expression of ASCT1 and 2 in postmortem brains from psychiatric patients. One work finds a significant decrease in ASCT-1 immunoreactivity in neurons and astrocytes of the cingulate cortex and hippocampus in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, consistent with the role of astrocytes in the pathophysiology of GLU neurotransmission in these major psychiatric disorders (Weis, 2007).

We also found that expression of mutant DISC1 was associated with significantly increased levels of the NR1 subunit and significantly decreased levels of the NR2A subunit of NMDAR in the hippocampus of transgenic mice at P21. Whether the altered levels of these two subunits of NMDAR a consequence of abnormal production of D-serine during postnatal development remains unknown. The future studies will evaluate this possibility in greater details, including cell-specific expression of NR1 subtype on astrocytes to provide a more comprehensive description of neuron-astrocyte interaction in this model (Lee, 2010). The directionality of the changes in expression appears in line with some postmortem studies (McCullumsmith, 2007; Feyissa, 2009; Weickert, 2013) but is dissimilar to the others (Law and Deakin, 2001; Kristiansen, 2006). This is not entirely unexpected given multiple potential factors that could influence human postmortem data, including age, gender, diagnosis, or a sampled area of the hippocampus.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that astrocyte-restricted expression of mutant DISC1 leads to increased levels of ASCT2, VGLUT1 and VGLUT3 on astrocytes and altered expression of VGLUT1 and the NR1 and NR2A subunits of NMDAR in the hippocampus at postnatal day 21. These results are consistent with decreased D-serine production in astrocytes due to disrupted interaction between SR and DISC1 as previously demonstrated (Ma, 2013). We believe that our model is a valuable preparation to explore the potential roles of DISC1 in the pathophysiology of astrocytes relevant to psychiatric disease.

Supplementary Material

No changes in expression of GLT-1 or GLAST in primary astrocytes

A - representative western blot images for primary astrocytes;

B - quantitative analyses of expression; n=4–6/group

No alterations in the enzymatic activity of GCPII or glutaminase

A - quantitative analysis of GCPII activity; n=3/group; means±SD

B - quantitative analysis of glutaminase activity; n=3/group; means±SD

Unaffected expression of mGluR3 or mGluR5

A - representative images of western blots for primary astrocytes (left) and the hippocampal tissue (right);

B - quantitative analyses of expression, n=4–6/group

No changes in expression of 3PGDH

A - representative western blot images for primary astrocytes and the hippocampal tissue (right);

B - quantitative analyses of expression; n=4–6/group

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by MH-083728 and The Brain and Behavior Research Foundation (former NARSAD) (MVP and SA).

References

- Balu DT, Li Y, Puhl MD, et al. Multiple risk pathways for schizophrenia converge in serine racemase knockout mice, a mouse model of NMDA receptor hypofunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(26):E2400–2409. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304308110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron R, Coyle JT. NAAG, NMDA receptor and psychosis. Curr Med Chem. 2012;19(9):1360–1364. doi: 10.2174/092986712799462685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein HG, Steiner J, Bogerts B. Glial cells in schizophrenia: pathophysiological significance and possible consequences for therapy. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9(7):1059–1071. doi: 10.1586/ern.09.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke LE, Barres BA. Emerging roles of astrocytes in neural circuit development. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(5):311–321. doi: 10.1038/nrn3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RM, Jr, Zielke HR, Woody RC. Valproate increases glutaminase and decreases glutamine synthetase activities in primary cultures of rat brain astrocytes. J Neurochem. 1994;62(3):1137–1143. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62031137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danbolt NC. Glutamate uptake. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;65(1):1–105. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan X, Chang JH, Ge S, et al. Disrupted-In-Schizophrenia 1 regulates integration of newly generated neurons in the adult brain. Cell. 2007;130(6):1146–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand D, Carniglia L, Caruso C, et al. mGlu3 receptor and astrocytes: partners in neuroprotection. Neuropharmacology. 2013;66:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastwood SL, Harrison PJ. Decreased expression of vesicular glutamate transporter 1 and complexin II mRNAs in schizophrenia: further evidence for a synaptic pathology affecting glutamate neurons. Schizophr Res. 2005;73(2–3):159–172. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto A, Asai N, Namba T, et al. Roles of Disrupted-In-Schizophrenia 1-Interacting Protein Girdin in Postnatal Development of the Dentate Gyrus. Neuron. 2009;63(6):774–787. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feyissa AM, Chandran A, Stockmeier CA, et al. Reduced levels of NR2A and NR2B subunits of NMDA receptor and PSD-95 in the prefrontal cortex in major depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33(1):70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukasawa M, Takayama E, Shinomiya N, et al. Identification of the promoter region of human placental 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;267(3):703–708. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guizzetti M, Kavanagh TJ, Costa LG. Measurements of astrocyte proliferation. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;758:349–59. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-170-3_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton NB, Attwell D. Do astrocytes really exocytose neurotransmitters? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11(4):227–238. doi: 10.1038/nrn2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydon PG, Blendy J, Moss SJ, et al. Astrocytic control of synaptic transmission and plasticity: a target for drugs of abuse? Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(Suppl 1):83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondziella D, Brenner E, Eyjolfsson EM, et al. How do glial-neuronal interactions fit into current neurotransmitter hypotheses of schizophrenia? Neurochem Int. 2007;50(2):291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen LV, Beneyto M, Haroutunian V, et al. Changes in NMDA receptor subunits and interacting PSD proteins in dorsolateral prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortex indicate abnormal regional expression in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11(8):737–747. 705. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda K, Yamada S, Tanaka M, et al. Behavioral alterations associated with targeted disruption of exons 2 and 3 of the Disc1 gene in the mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20(23):4666–4683. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law AJ, Deakin JF. Asymmetrical reductions of hippocampal NMDAR1 glutamate receptor mRNA in the psychoses. Neuroreport. 2001;12(13):2971–2974. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200109170-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MC, Ting KK, Adams S, Brew BJ, Chung R, Guillemin GJ. Characterisation of the expression of NMDA receptors in human astrocytes. PLoS One. 2010;5(11):e14123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma TM, Abazyan S, Abazyan B, et al. Pathogenic disruption of DISC1-serine racemase binding elicits schizophrenia-like behavior via D-serine depletion. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(5):557–567. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y, Ge X, Frank CL, et al. Disrupted in schizophrenia 1 regulates neuronal progenitor proliferation via modulation of GSK3beta/beta-catenin signaling. Cell. 2009;136(6):1017–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullumsmith RE, Kristiansen LV, Beneyto M, et al. Decreased NR1, NR2A, and SAP102 transcript expression in the hippocampus in bipolar disorder. Brain Res. 2007;1127(1):108–118. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montana V, Ni Y, Sunjara V, et al. Vesicular glutamate transporter-dependent glutamate release from astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2004;24(11):2633–2642. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3770-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naar F, Dinh A, Genet F, et al. Pseudoseptical myositis ossificans in spinal cord injuried patients. Presse Med. 2012;41(1):e15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.lpm.2011.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni YPV. Dual regulation of Ca2+-dependent glutamate release from astrocytes: vesicular glutamate transporters and cytosolic glutamate levels. Glia. 2009;12:1296–305. doi: 10.1002/glia.20849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parpura V, Baker BJ, Jeras M, et al. Regulated exocytosis in astrocytic signal integration. Neurochem Int. 2010;57(4):451–459. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parpura V, Heneka MT, Montana V, et al. Glial cells in (patho)physiology. J Neurochem. 2012;121(1):4–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07664.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parpura V, Zorec R. Gliotransmission: Exocytotic release from astrocytes. Brain Res Rev. 2010;63(1–2):83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletnikov MV, Ayhan Y, Nikolskaia O, et al. Inducible expression of mutant human DISC1 in mice is associated with brain and behavioral abnormalities reminiscent of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13(2):173–186. 115. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkowska G, Stockmeier CA. Astrocyte pathology in major depressive disorder: insights from human postmortem brain tissue. Curr Drug Targets. 2013;14(11):1225–1236. doi: 10.2174/13894501113149990156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro CS, Reis M, Panizzutti R, et al. Glial transport of the neuromodulator D-serine. Brain Res. 2002;929(2):202–209. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03390-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MB, Blakely RD, Couto R, et al. Hydrolysis of the brain dipeptide N-acetyl-L-aspartyl-L-glutamate. Identification and characterization of a novel N-acetylated alpha-linked acidic dipeptidase activity from rat brain. J Biol Chem. 1987;262(30):14498–14506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas C, Frazier ST, Flanary J, et al. Kinetics and inhibition of glutamate carboxypeptidase II using a microplate assay. Anal Biochem. 2002;310(1):50–54. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(02)00286-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose CF, Verkhratsky A, Parpura V. Astrocyte glutamine synthetase: pivotal in health and disease. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41(6):1518–1524. doi: 10.1042/BST20130237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg D, Artoul S, Segal AC, Kolodney G, Radzishevsky I, Dikopoltsev E, Foltyn VN, Inoue R, Mori H, Billard JM, Wolosker H. Neuronal D-serine and glycine release via the Asc-1 transporter regulates NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic activity. J Neurosci. 2013;33:3533–44. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3836-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanacora G, Banasr M. From pathophysiology to novel antidepressant drugs: glial contributions to the pathology and treatment of mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(12):1172–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler R, Rothstein JD. Regulation and dysregulation of glutamate transporters. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2006;(175):277–303. doi: 10.1007/3-540-29784-7_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schousboe A, Waagepetersen HS. Role of astrocytes in glutamate homeostasis: implications for excitotoxicity. Neurotox Res. 2005;8(3–4):221–225. doi: 10.1007/BF03033975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer MJ, Bennett BD, Joshi AD, et al. Inhibition of glutaminase preferentially slows growth of glioma cells with mutant IDH1. Cancer Res. 2010;70(22):8981–8987. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seshadri S, Kamiya A, Yokota Y, et al. Disrupted-in-Schizophrenia-1 expression is regulated by beta-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme-1-neuregulin cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(12):5622–5627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909284107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnieder TP, Dwork AJ. Searching for neuropathology: gliosis in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69(2):134–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PF, Daly MJ, O’Donovan M. Genetic architectures of psychiatric disorders: the emerging picture and its implications. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13(8):537–551. doi: 10.1038/nrg3240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N, Sakurai T. Roles of glial cells in schizophrenia: possible targets for therapeutic approaches. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;53:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot K, Eidem WL, Tinsley CL, et al. Dysbindin-1 is reduced in intrinsic, glutamatergic terminals of the hippocampal formation in schizophrenia. J Clin Invest. 2004;113(9):1353–1363. doi: 10.1172/JCI20425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uezato A, Meador-Woodruff JH, McCullumsmith RE. Vesicular glutamate transporter mRNA expression in the medial temporal lobe in major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11(7):711–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varea E, Guirado R, Gilabert-Juan J, et al. Expression of PSA-NCAM and synaptic proteins in the amygdala of psychiatric disorder patients. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(2):189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weickert CS, Fung SJ, Catts VS, et al. Molecular evidence of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor hypofunction in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(11):1185–1192. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis S, Llenos IC, Dulay JR, et al. Changes in region- and cell type-specific expression patterns of neutral amino acid transporter 1 (ASCT-1) in the anterior cingulate cortex and hippocampus in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depression. J Neural Transm. 2007;114(2):261–271. doi: 10.1007/s00702-006-0544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolosker H. Serine racemase and the serine shuttle between neurons and astrocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1814(11):1558–1566. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolosker H, Radzishevsky I. The serine shuttle between glia and neurons: implications for neurotransmission and neurodegeneration. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41(6):1546–1550. doi: 10.1042/BST20130220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwain IH, Yen SS. Neurosteroidogenesis in astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and neurons of cerebral cortex of rat brain. Endocrinology. 1999;140(8):3843–3852. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.8.6907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

No changes in expression of GLT-1 or GLAST in primary astrocytes

A - representative western blot images for primary astrocytes;

B - quantitative analyses of expression; n=4–6/group

No alterations in the enzymatic activity of GCPII or glutaminase

A - quantitative analysis of GCPII activity; n=3/group; means±SD

B - quantitative analysis of glutaminase activity; n=3/group; means±SD

Unaffected expression of mGluR3 or mGluR5

A - representative images of western blots for primary astrocytes (left) and the hippocampal tissue (right);

B - quantitative analyses of expression, n=4–6/group

No changes in expression of 3PGDH

A - representative western blot images for primary astrocytes and the hippocampal tissue (right);

B - quantitative analyses of expression; n=4–6/group