Abstract

Objective

Studies have repeatedly shown racial and ethnic differences in mental health care. Prior research focused on relationships between patient preferences and ethnicity, with little attention given to the possible relationship between physicians’ ethnicity and their treatment recommendations.

Design

A questionnaire was mailed to a national sample of U.S. primary care physicians and psychiatrists. It included vignettes of patients presenting with depression, anxiety, and medically unexplained symptoms. Physicians were asked how likely they would be to advise medication, see the patient regularly for counseling, refer to a psychiatrist, or refer to a psychologist or licensed mental health counselor.

Results

The response rate was 896 of 1,427 (63%) for primary care physicians and 312 of 487 (64%) for psychiatrists. Treatment preferences varied across diagnoses. Compared to whites (referent), black primary care physicians were less likely to use antidepressants (depression vignette), but more likely to see the patient for counseling (all vignettes), and to refer to a psychiatrist (depression vignette). Asian primary care physicians were more likely to see the patient for counseling (anxiety and medically unexplained symptoms vignettes) and to refer to a psychiatrist (depression and anxiety vignettes). Asian psychiatrists were more likely to recommend seeing the patient regularly for counseling (depression vignette).

Conclusions

Overall these findings suggest physician race and ethnicity contributes to different patterns of treatment for basic mental health concerns.

Introduction

Evidence has consistently shown racial and ethnic differences in mental health care, across a variety of patient samples and psychiatric diagnoses. In the United States, black patients are less likely to be diagnosed with depression (4.2%) than white patients (6.4%) or Hispanics (7.2%).(Akincigil, Olfson et al. 2012) Depressed blacks are less likely than whites to receive antidepressants (52.5% versus 68.7%), and are half as likely to receive any depression treatment.(Akincigil, Olfson et al. 2012) Among patients with depression or an anxiety disorder, blacks (17%) and Hispanics (24%) are less likely than whites (34%) to receive “appropriate care.” (Young, Klap et al. 2001) Among patients with any mood or anxiety disorder, blacks (45.2%) are less likely than whites (56.3%) and Hispanics (56.4%) to receive “minimally adequate care.”(Ault-Brutus 2012) Blacks (23.1%) and Hispanics (25.3%) are also less likely than whites (36.3%) to receive any mental health care. (Ault-Brutus 2012) In a study that included patients with a major depressive episode, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, or another serious mental illness, blacks were less likely than whites to receive “guideline consistent care.” (Wang, Berglund et al. 2000) Blacks (33.2%) were also less likely than whites (54%) to receive follow up after hospitalization for any mental illness.(Schneider, Zaslavsky et al. 2002)

Debates exist internationally also. In Europe some advocacy groups have accused psychiatrists of institutional racism, pointing to higher rates of psychiatric admission and more adverse pathways to mental health care for black and other minority groups.(Singh and Burns 2006)

The causes underlying racial and ethnic differences have not been fully identified. Most likely it is due to a complex interplay of patient preferences, physician recommendations, and ethnic-community biases. Prior research has focused on the relationship between patient preferences and ethnicity,(Cooper, Gonzales et al. 2003; Givens, Katz et al. 2007; Ault-Brutus 2012) but little attention has been given to the possibility of a relationship between physicians’ ethnicity and their treatment recommendations. This is potentially important because ethnic-community biases that affect patients are also likely to affect physicians. Moreover if patients and physicians self-aggregate by ethnicity, then ethnicity-associated patterns may be reinforced.

We recently completed a national survey of primary care physicians and psychiatrists, asking how they would manage depression, anxiety, and medically unexplained symptoms. The survey’s primary outcome was an examination of how physicians’ religious characteristics influence their treatment preferences. Physician race was incorporated into the survey as a secondary outcome measure. This paper reports observations about race-ethnicity-related variations in physicians’ responses to common mental health concerns.

Method

Between September 2009 and June 2010, we mailed a confidential self-administered questionnaire to a stratified random sample consisting of 1504 US primary care physicians and 512 US psychiatrists 65 years old or younger. The sample was generated from the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile, a database intended to include all practicing US physicians. To increase minority religious group representation in the primary care sample, we used validated surname lists (Sheskin 1998; Lauderdale and Kestenbaum 2000; Lauderdale 2006) to create four strata and oversampled from these strata. We sampled a) 121 primary care physicians with typical Asian surnames (Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Korean, Asian Indian, Vietnamese), b) 171 primary care physicians with typical Arabic surnames, c) 86 primary care physicians with typical Jewish surnames, and d) 1126 additional primary care physicians (from all those whose surnames were not on one of these ethnic lists). The psychiatrist sample was not sufficiently large to warrant oversampling by ethnic surname. Physicians received up to three separate mailings of the questionnaire. The first mailing included a $20 bill and the third offered an additional $30 for participation. Data were double keyed, cross-compared, and corrected against the original. The University of Chicago institutional review board approved the study.

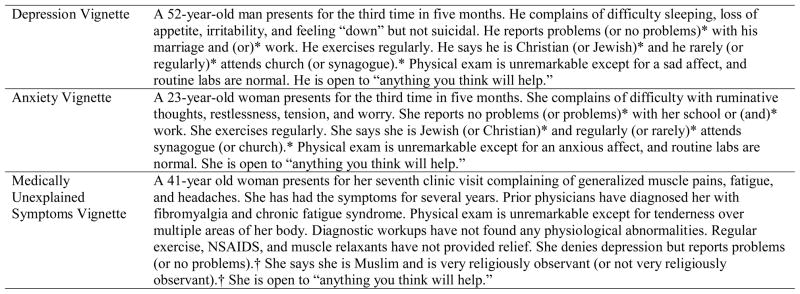

The questionnaire included three vignette experiments, involving patients suffering from depression, anxiety, and medically unexplained symptoms (Figure 1). Following each vignette, primary care physicians were asked how likely they would be to recommend antidepressant medication, see patients regularly for counseling, refer patients to a psychiatrist, or refer patients to a psychologist or other licensed mental health counselor. Psychiatrists were asked how likely they would be to recommend the primary care physician use each intervention. Responses utilized a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all likely” to “very likely.” For multivariable models this was dichotomized as “somewhat or very likely” versus “not very likely or not at all likely.” Results for each vignette are analyzed in detail elsewhere.(Lawrence, Rasinski et al. 2012; Lawrence, Rasinski et al. 2013a; Lawrence, Rasinski et al. 2013b)

Figure 1.

Texts for the vignette experiments

*Three patient characteristics (problems, religious affiliation, attendance) were varied in a between-subjects factorial experiment. Each vignette had eight possible versions (2×2×2). The three characteristics in the second vignette were opposite those in the first (e.g. a depressed Christian was followed by an anxious Jew).

† Two patient characteristics (problems, observance) were varied in a between-subjects factorial experiment. The vignette had four possible versions (2×2).

Each model included physician race (self-reported) and several covariates: sex, age (in quartiles), geographic region, and religious affiliation (self-reported as Non-Evangelical Protestant, Evangelical Protestant, Catholic, Muslim, Jewish, Hindu, other religion, or no religion). Each model also adjusted for the main effects of the experiment design.

Statistical analysis

Stratum weights for the primary care sample were calculated to account for oversampling from the ethnic surname strata (the design weight). We also created a post-stratification adjustment weight to correct for a slightly higher response rate among US medical school graduates (65% response) versus international medical school graduates (56% response, p=0.002), and among physicians whose roles are primarily teaching or “other” (75% response, 103/138) versus office-based, hospital-based, research, administrative, or unclassified (62% response, 793/1288, p=0.004). Weights were the inverse probability of a person with the relevant characteristic being in the final dataset. The final weight for each case/respondent was the product of the design weight and the post-stratification adjustment weight. This enabled us to adjust for sample stratification and variable response rates in order to generate estimates for the population of US primary care physicians. Weights were not calculated for the psychiatrist sample because no disproportionate sampling by name strata was performed, and because response rates for background variables from the Masterfile did not differ significantly.

We first counted how many interventions each physician would recommend for each vignette (range 0–4). Ordered logistic regression was used to characterize the relationship between race and the number of treatments recommended, while adjusting for sex, age (in quartiles), region, religious affiliation, and main effects of each experiment variable. Bonferroni correction adjusted for comparison across three vignettes.

We then used bivariate analyses to estimate the percentage of US primary care physicians and psychiatrists in each demographic category who were “somewhat or very likely” to recommend each intervention. In the multivariable analyses we examined whether racial/ethnic patterns persisted after adjusting for covariates and experimental variables. Bonferroni correction adjusted for comparison across four outcome variables.

Primary care physicians and psychiatrists were analyzed separately. All analyses were conducted using the survey-design-adjusted feature of Stata SE statistical software (version 11.0; Stata Corp., College Station, Tex.).

Results

Respondent Characteristics

The response rate was 63% (896/1427) for primary care physicians and 64% (312/487) for psychiatrists, after excluding 77 primary care physicians and 25 psychiatrists who had invalid addresses or were no longer practicing. Details regarding the response rate can be found elsewhere. (Lawrence, Rasinski et al. 2012) The response rates did not differ significantly by age, gender, region, or board certification. We could not assess response rates by race/ethnicity as those variables were not part of the sampling dataset. Among primary care physician respondents, 71% were white (n=625), 6% were black (n=53), 16% were Asian (n=142), 5% were Hispanic/Latino (n=41), and 2% were other (n=22). Among psychiatrist respondents 64% were white (n=198), 7% were black (n=23), 21% were Asian (n=64), 5% were Hispanic/Latino (n=17), and 3% were other (n=8). Among Asian primary care physicians, 30% (n=35) were east Asian, 54% (n=73) were south Asian, and 17% (n=23) were other Asian. Among Asian psychiatrists, 40% (n=23) were east Asian, 42% (n=24) were south Asian, and 18% (n=10) were other Asian. Respondent demographics are described in detail elsewhere. (Lawrence, Rasinski et al. 2012)

Number of treatments recommended

In ordered logistic regression models, Black and Asian primary care physicians tended to recommend more treatment options than whites when treating depression (OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.2–4.7, p=.016 for Blacks, OR 2.9, 95% CI 1.4–5.7, p=.002 for Asians) and anxiety (OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.3–4.3, p=.006 for Blacks, OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.4–5.4, p=.004 for Asians).

Asian psychiatrists recommended more treatment options than white psychiatrists for a depressed patient (OR 4.5, 95% CI 2.2–9.3, p<.001).

Specific treatment patterns: Primary Care Physicians

Black primary care physicians differed from whites in several ways. When treating a depressed patient they were less likely to use an antidepressant (82% versus 92%, OR 0.3, 95% CI 0.1–0.7), more likely to provide in-office counseling (55% versus 35%, OR 2.6, 95% CI 1.4–4.9), and more likely to refer to a psychiatrist (63% versus 38%, OR 3.4, 95% CI 1.8–6.5). Black physicians were more likely than white physicians to offer in-office counseling when treating an anxious patient (53% versus 32%, OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.5–5.1) and when treating a patient with medically unexplained symptoms (41% versus 27%, OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.2–4.3). (Table 1)

Table 1.

This table shows the percentage of primary care physicians who are somewhat/very likely to recommend each intervention for three vignette patients, by physician race/ethnicity.

| Prescribe medication | Offer in-office counseling | Refer to a psychiatrist | Refer to a psychologist or counselor | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(%*) | OR(95%CI)† | P | N(%) | OR(95%CI)† | P | N(%) | OR(95%CI)† | P | N(%) | OR(95%CI)† | P | |

| Depression Vignette | Prescribe anti-depressant medication | |||||||||||

| White | 569(92) | Referent | 216(35) | Referent | 239(38) | Referent | 521(85) | Referent | ||||

| Black | 44(82) | .3(.1–.7) | .008 | 29(55) | 2.6(1.4–4.9) | .003 | 33(63) | 3.4(1.8–6.5) | <.001 | 43(82) | .8(.4–1.8) | .618 |

| Asian | 124(87) | .5(.2–1.2) | .118 | 75(52) | 1.7(.97–2.9) | .064 | 88(66) | 3.9(2.1–7.1) | <.001 | 107(79) | 1.4(.7–2.8) | .274 |

| Hispanic | 36(94) | 1.2(.4–4.1) | .753 | 20(41) | 1.2(.6–2.4) | .704 | 22(57) | 1.8(.8–4.0) | .160 | 35(91) | 3.5(.96–12.8) | .057 |

| Other | 17(76) | .2(.07–.7) | .010 | 10(43) | 1.3(.5–3.5) | .580 | 9(39) | 1.0(.4–2.8) | .999 | 15(72) | .8(.3–2.3) | .652 |

| Anxiety Vignette | Prescribe anti-anxiety medication | |||||||||||

| White | 478(77) | Referent | 198(32) | Referent | 240(38) | Referent | 543(87) | Referent | ||||

| Black | 44(83) | 1.5(.7–3.1) | .317 | 28(53) | 2.7(1.5–5.1) | .001 | 27(53) | 1.9(1.001–3.5) | .050 | 43(83) | .7(.3–1.5) | .331 |

| Asian | 106(76) | .8(.4–1.6) | .612 | 79(53) | 2.1(1.2–3.7) | .008 | 90(66) | 3.5(1.9–6.4) | <.001 | 113(84) | 1.1(.6–2.1) | .748 |

| Hispanic | 34(88) | 2.4(.8–6.7) | .105 | 20(40) | 1.4(.7–2.8) | .394 | 20(55) | 1.6(.7–3.8) | .251 | 36(92) | 2.5(.7–9.1) | .151 |

| Other | 16(79) | .8(.3–2.3) | .712 | 10(44) | 1.6(.6–4.3) | .340 | 7(36) | .9(.3–2.4) | .779 | 16(77) | .7(.2–2.0) | .505 |

| Medically Unexplained Symptoms Vignette | Prescribe anti-depressant medication | |||||||||||

| White | 470(77) | Referent | 167(27) | Referent | 200(33) | Referent | 460(75) | Referent | ||||

| Black | 32(62) | .5(.3–.9) | .029 | 22(41) | 2.3(1.2–4.3) | .012 | 23(44) | 1.8(.9–3.4) | .080 | 38(73) | .9(.5–1.9) | .879 |

| Asian | 100(72) | .6(.3–1.2) | .161 | 74(51) | 2.2(1.3–3.7) | .005 | 72(52) | 2.0(1.1–3.7) | .017 | 91(66) | 1.2(.6–2.2) | .622 |

| Hispanic | 32(73) | .7(.3–1.8) | .485 | 21(44) | 2.0(.9–4.1) | .075 | 17(41) | 1.0(.4–2.1) | .901 | 27(66) | .6(.3–1.4) | .278 |

| Other | 15(72) | .7(.3–1.8) | .475 | 11(46) | 2.1(.8–5.5) | .130 | 8(44) | 1.4(.5–3.8) | .533 | 20(86) | 2.8(.5–14.9) | .232 |

Percentages are adjusted for survey design and estimate the percentage of all US primary care physicians.

Each multivariable logistic regression model adjusts for sex, age (in quartiles), region, religious affiliation, and main effects of the vignette-experiment design.

Asian primary care physicians also differed from whites. When treating a depressed patient they were more likely to refer to a psychiatrist (66% versus 38%, OR 3.9, 95% CI 2.1–7.1). When treating an anxious patient they were more likely to provide in-office counseling (53% versus 32%, OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.2–3.7), and more likely to refer to a psychiatrist (66% versus 38%, OR 3.5, 95% CI 1.9–6.4). When treating medically unexplained symptoms Asians were more likely than whites to provide in-office counseling (51% versus 27%, OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.3–3.7). (Table 1)

In a post-hoc analysis we added to each model whether the physician graduated from a US or a non-US medical school. Primary care physicians who graduated from a non-US medical school were more likely to provide in-office counseling for depression (57% versus 34%, OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.4–3.3), anxiety (56% versus 32%, OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.3–3.0), and medically unexplained symptoms (54% versus 27%, OR 2.4, 95% CI 1.6–3.6). In these models, black race continued to increase the likelihood of offering in-office counseling for depression and anxiety, but was not significant for medically unexplained symptoms (p=.026).

Specific treatment patterns: Psychiatrists

Asian psychiatrists differed from whites when making recommendations to primary care physicians. For a depressed patient, Asian psychiatrists were more likely to recommend in-office counseling (60% versus 34%, OR 3.3, 95% CI 1.5–7.6). (Table 2) In post-hoc analysis, graduating from a US versus non-US medical school was not associated with treatment preferences after adjusting for covariates.

Table 2.

This table shows the percentage of psychiatrists who are somewhat/very likely to recommend the primary care physician offer each intervention for three vignette patients, by physician race/ethnicity.

| Prescribe medication | Offer in-office counseling | Refer to a psychiatrist | Refer to a psychologist or counselor | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(%*) | OR(95%CI)† | P | N(%) | OR(95%CI)† | P | N(%) | OR(95%CI)† | P | N(%) | OR(95%CI)† | P | |

| Depression Vignette | Prescribe anti-depressant medication | |||||||||||

| White | 171(88) | Referent | 64(34) | Referent | 146(76) | Referent | 163(84) | Referent | ||||

| Black | 17(77) | .4(.1–1.7) | .214 | 4(19) | .5(.2–1.4) | .164 | 17(77) | .9(.3–3.0) | .856 | 16(73) | .4(.1–1.4) | .155 |

| Asian | 59(92) | 2.9(.5–17.2) | .240 | 36(60) | 3.3(1.5–7.6) | .004 | 58(95) | 7.6(1.5–38.5) | .014 | 57(90) | 2.1(.6–7.7) | .249 |

| Hispanic | 14(88) | .6(.1–3.5) | .567 | 7(44) | 1.4(.4–5.0) | .561 | 11(73) | .9(.2–3.7) | .877 | 16(94) | 3.1(.3–29.0) | .310 |

| Other | 8(100) | N/A | N/A | 2(25) | .6(.1–2.8) | .516 | 7(88) | 2.4(.4–16.1) | .369 | 7(88) | 2.1(.2–23.9) | .559 |

| Anxiety Vignette | Prescribe anti-anxiety medication | |||||||||||

| White | 138(71) | Referent | 70(36) | Referent | 150(80) | Referent | 178(91) | Referent | ||||

| Black | 17(74) | 1.0(.4–2.9) | .980 | 6(26) | .6(.2–1.9) | .395 | 19(83) | 1.2(.3–4.4) | .809 | 20(87) | .5(.1–1.8) | .257 |

| Asian | 48(76) | .8(.4–1.7) | .560 | 31(53) | 1.6(.8–3.5) | .213 | 56(90) | 2.2(.6–8.1) | .251 | 55(89) | .9(.2–4.4) | .869 |

| Hispanic | 10(59) | .5(.1–2.0) | .347 | 8(47) | 1.6(.4–5.7) | .493 | 13(76) | .6(.2–2.4) | .482 | 16(94) | 1.0(.1–11.7) | .984 |

| Other | 6(75) | 1.1(.2–4.7) | .937 | 2(25) | .4(.09–2.1) | .306 | 8(100) | N/A | N/A | 8(100) | N/A | N/A |

| Medically Unexplained Symptoms Vignette | Prescribe anti-depressant medication | |||||||||||

| White | 138(71) | Referent | 76(39) | Referent | 140(73) | Referent | 160(81) | Referent | ||||

| Black | 13(57) | .7(.2–1.8) | .409 | 5(22) | .5(.2–1.5) | .214 | 18(78) | 1.7(.5–5.6) | .364 | 18(78) | .8(.3–2.7) | .745 |

| Asian | 42(68) | 1.0(.5–2.3) | .949 | 37(62) | 2.3(1.1–5.0) | .035 | 53(87) | 4.4(1.4–13.9) | .013 | 49(83) | 1.7(.6–4.6) | .322 |

| Hispanic | 13(76) | 1.2(.4–4.1) | .714 | 8(47) | 1.7(.5–5.6) | .382 | 14(82) | 1.7(.5–6.6) | .426 | 16(94) | 2.8(.3–27.8) | .383 |

| Other | 4(50) | .4(.1–2.2) | .308 | 3(38) | .6(.1–2.7) | .479 | 8(100) | N/A | N/A | 7(88) | 1.9(.2–18.6) | .561 |

Percentages estimate the percentage of all US psychiatrists.

Each multivariable logistic regression model adjusts for sex, age (in quartiles), region, religious affiliation, and main effects of the vignette-experiment design.

Discussion

In this national survey of primary care physicians and psychiatrists, we found significant racial/ethnic variation in physicians’ treatment recommendations for depression, anxiety, and medically unexplained symptoms. These recommendations differed according to the specific intervention and the specific diagnosis being considered.

Black primary care physicians were less likely to use antidepressants when treating a depressed patient. This mirrors multiple reports that black patients prefer not to receive antidepressant medication. For example, in a telephone survey of patients with a history of depression (n=649 whites, 97 African Americans) African Americans (51%) were less likely than whites (74%) to consider antidepressants an acceptable treatment.(Cooper, Gonzales et al. 2003) In a survey of primary care patients (n=755), African Americans (67%) were less likely than whites (76%) to accept prescription medication for depression.(Givens, Katz et al. 2007)

While black physicians seem less likely to recommend antidepressants, we found no difference in prescribing anti-anxiety medication. This parallels data from the National Comorbidity Survey, which also found no difference in anti-anxiety medication use between whites, blacks, and Hispanics.(Ault-Brutus 2012)

Black and Asian physicians were frequently more likely than whites to provide or recommend in-office counseling, and to refer the patient to a psychiatrist. This suggests that physicians from both minority groups are equally committed to treating patients’ psychiatric symptoms, even though their recommendations may not include medication. Talk therapy might be especially appropriate for the patients in the vignettes, who all present with mild to moderate symptoms. This pattern of preferring talk therapy to medication has been reported before. Among persons utilizing an internet based depression screening instrument (n=78,753), whites preferred medication over counseling (42.2% versus 33.8%); while African Americans (54.0% versus 26.4%), Asians and Pacific Islanders (48.8% versus 24.8%), and Hispanics (46.4% versus 31.6%) preferred counseling over medications.(Givens, Houston et al. 2007) Whether physicians’ recommendations and patients’ preferences turn into active therapy is another issue. A study of elderly persons in the community did not find a difference in the psychotherapy rates between African Americans (18.0%) and whites (15.0%).(Akincigil, Olfson et al. 2012) And a survey in the United Kingdom (n=27,000) found that Asians and Black mental healthcare users were less likely than whites to have received talk therapy in the past year. (Raleigh 2007)

If ethnic minority physicians share the treatment preferences of their ethnic groups, it is worth considering whether physicians play a role in perpetuating differences among minority groups regarding the treatments they receive. So far, data on racial/ethnic concordance between physicians and patients is somewhat paradoxical. African Americans are more likely than whites to prefer to see a health professional of their same race/ethnicity. (Cooper, Gonzales et al. 2003) Race concordant visits tend to last longer and involve slower conversation. (Cooper, Roter et al. 2003) Patients with race concordant physicians tend to rate their physicians as being more participatory; and patients are more likely to feel satisfied with the visit and to recommend the physician to a friend. (Cooper, Roter et al. 2003) In addition, African American patients say they are more likely to disclose their problems to African American physicians.(Das, Olfson et al. 2006) These patterns suggest it should be easier for racial/ethnic minority physicians to diagnose mental health problems, but (paradoxically) white physicians diagnose depression in their African American patients more frequently than black physicians.(Das, Olfson et al. 2006) Our data add to the picture that ethnic minority physicians might play some role in perpetuating differences.

It is important to note that the differences in treatment preferences reported here are not the same as evidence for healthcare disparity. Each of the treatment options considered is a reasonable intervention for the vignette patients. Nevertheless, these findings contribute to the healthcare disparities literature by suggesting an association between physician race and treatment recommendations.

The United States has a unique blend of public sector healthcare and private practitioners, which differs from other countries where healthcare exists primarily in the public sector. Healthcare decisions in the United States involve many factors, including the patient’s preference, the patient’s personal resources, the physician’s incentive to keep the patient, and the physician’s experience with what prior patients have wanted. The relative weight given to each factor is likely to differ between public and private healthcare models. Which factors are most affected by race and ethnicity – across multiple countries – remains to be studied.

This study has strengths. Earlier work generally focused on differences between blacks and whites (and occasionally Hispanics), while the current paper included Asians also. Earlier studies often grouped together various diagnoses, raising questions about whether patterns differ for specific diagnoses. This paper explicitly separated depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and medically unexplained symptoms. To our knowledge the relationship between physician race or ethnicity and treatment preferences has not been previously studied.

This study also has limitations. Vignettes cannot reproduce clinical encounters. In real life encounters, physicians have access to far more information about their patients, and can dialogue about diagnoses and treatment options. Patients with financial, geographic, or time constraints may not be able to access all of the treatments available in our survey. This survey was not primarily focused on the relationship between race or ethnicity and treatment preferences, so it provides limited detail on how or why these differences exist, and findings should be considered preliminary and provisional until confirmed by other studies. The vignettes directly described mental health symptoms, so these data do not address ethnic differences regarding risk of mental illness, rates of diagnosis, or access to care. As in all surveys, non-responders may differ from responders in ways that bias our results.

These findings have several implications. These data could be used for clinician education, increasing physicians’ self-awareness of how their personal backgrounds might influence treatment recommendations. Physicians might then make an extra effort to discuss all reasonable treatment options with patients, even ones the physician might not prefer. Patients might become more aware that not all medical recommendations are primarily based on medical evidence, and might feel more empowered to inquire about all treatment options, or to advocate more strongly for their preferred treatments. Future studies on healthcare disparities might build on these data by developing richer datasets that consider how physician race and ethnicity factor into differences in treatments among minority groups.

Conclusion

We found that Black and Asian physicians differ from whites in some of their treatment recommendations, but these differences vary depending on the specific treatment considered and the diagnosis being treated. While previous literature has shown that black patients are less likely to receive antidepressants, we found that black primary care physicians are less likely to recommend antidepressants. However, Black and Asian physicians appeared more likely than whites to recommend in-office counseling, and to refer to a psychiatrist. Overall these findings suggest physician race and ethnicity contributes to different patterns of treatment for common mental health concerns.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by grants from the John Templeton Foundation and the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (1 K23 AT002749, to Farr Curlin).

Footnotes

Location of work: Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY; and Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago IL

Conflicts: The authors have no financial relationships with commercial interests.

Contributor Information

Ryan E. Lawrence, Email: rlawrence@uchicago.edu, Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University Medical Center and the New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1051 Riverside Drive, Box 103, New York, NY 10032, (212)543-5553.

Kenneth A. Rasinski, Email: krasinsk@medicine.bsd.uchicago.edu, Department of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

John D. Yoon, Email: jyoon1@medicine.bsd.uchicago.edu, Department of Medicine and the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

Farr A. Curlin, Email: fcurlin@bsd.uchicago.edu, Department of Medicine and the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

References

- Akincigil A, Olfson M, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in depression care in community-dwelling elderly in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:319–328. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ault-Brutus AA. Changes in racial-ethnic disparities in use and adequacy of mental health care in the United States, 1990–2003. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(6):531–540. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201000397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, et al. The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and White primary care patients. Medical Care. 2003;41(4):479–489. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000053228.58042.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LA, Roter DL, et al. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:907–915. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das AK, Olfson M, et al. Depression in African Americans: breaking barriers to detection and treatment. J Fam Pract. 2006;55(1):30–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givens JL, Houston TK, et al. Ethnicity and preferences for depression treatment. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2007;29:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givens JL, I, Katz R, et al. Stigma and the acceptability of depression treatments among African Americans and Whites. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1292–1297. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0276-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauderdale DS. Birth outcomes for Arabic-named women in California before and after September 11. Demography. 2006;43(1):185–201. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauderdale DS, Kestenbaum B. Asian American ethnic identification by surname. Population Research and Policy Review. 2000;19:283–300. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence RE, Rasinski KA, et al. Religion and anxiety treatments in primary care patients. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2013a;26(5):526–538. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2012.752461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence RE, Rasinski KA, et al. Religion and beliefs about treating medically unexplained symptoms: a survey of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2013b;45(1):31–44. doi: 10.2190/PM.45.1.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence RE, Rasinski KA, et al. Primary care physicians’ and psychiatrists’ approaches to treating mild depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;126(5):385–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01887.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raleigh VS. Ethnic variations in the experiences of mental health service users in England: results of a national patient survey programme. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;191:304–312. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.032417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider EC, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Racial disparities in the quality of care for enrollees in Medicare managed care. JAMA. 2002;287:1288–1294. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.10.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheskin IM. A methodology for examining the changing size and spatial distribution of a Jewish population: a Miami case study. Shofar. 1998;17(1):97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Singh SP, Burns T. Race and mental health: there is more to race than racism. British Medical Journal. 2006;333(7569):648–651. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38930.501516.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Berglund P, et al. Recent care of common mental disorders in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:284–292. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.9908044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AS, Klap R, et al. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:55–61. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]