Abstract

Introduction

Systemic cytokines produced by contracting skeletal muscles may affect the onset and severity of intensive care unit (ICU)-acquired weakness after critical illness.

Aims

The purpose of this research was to determine the serum levels of interleukin (IL)-8, IL-15, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) among patients receiving mechanical ventilation for >48 hr and examine the relationships of these myokines to outcomes of patient delirium, muscle strength, activities of daily living (ADLs), duration of mechanical ventilation, and length of ICU stay.

Methods

In this exploratory, repeated-measures interventional study, the 36 participants received 20 min of once-daily in-bed or out-of-bed activity using an established early progressive mobility protocol after physiologic stability had been demonstrated for ≥4 hr in the ICU. Blood samples were drawn on 3 consecutive days, beginning on the day of study enrollment, for serum cytokine quantification.

Results

IL-8, IL-15, and TNF-α were highly variable and consistently elevated in participants compared to normal healthy adults. About 1/3 of participants were positive for significant muscle weakness at discharge from ICU. Repeated values of mean postactivity IL-8 serum values were significantly associated only with ADL following ICU discharge. There were no significant associations with repeated values of mean postactivity IL-15 or TNF-α serum values and outcomes.

Conclusion

Results provide preliminary data for exploring the potential effects of elevated serum values IL-8 and IL-15 in muscle health and TNF-α for muscle damage, including effect sizes to calculate the sample sizes needed for future studies.

Keywords: Keywords intensive care unit, interleukin-8, interleukin-15, tumor necrosis factor-α, early progressive mobility, biomarkers, muscle, ICU

Patients experiencing more than 3–5 days of severe critical illness are considered at high risk for developing profound and persistent weakness, a syndrome known as intensive care unit–acquired weakness (ICUAW; Kress & Herridge, 2012). ICUAW occurs early in the course of diagnoses associated with ICU hospitalization as well as mechanical ventilation (Batt, Dos Santos, Cameron, & Herridge, 2013; Schefold, Bierbrauer, & Weber-Carstens, 2010). The syndrome is accompanied by loss of myosin, impaired muscle-membrane excitability, and reduced contractile force (Lacomis, 2011; Llano-Diez et al., 2012; Pedersen & Febbraio, 2008; Weber-Carstens et al., 2010). Additionally, after mechanical ventilation lasting longer than 72 hr in the critically ill adult, reduced function and muscle strength are correlated with impaired cognition (E. Fan, 2012; Y. Fan, Guo, Li, & Zhu, 2012; Wiencek & Winkelman, 2010).

We hypothesized that muscle contraction from early progressive mobility activities can disrupt muscle damage during critical illness, ultimately decreasing the onset or severity of ICUAW. Contracting skeletal muscles synthesize and release a number of cytokines, known as myokines (Henriksen, Green, & Pedersen, 2012; Pedersen, Akerstrom, Nielsen, & Fischer, 2007), which may alter the course of ICUAW by decreasing muscle damage, promoting muscle repair, and reducing cognitive impairment (Makowshi, 2012; Philippou, Maridaki, Theos, & Koutsilieris, 2012). Myokines contribute to signaling pathways for muscle fiber regeneration and remodeling and modify cytokine production in the liver and circulating white blood cells. For example, interleukin (IL)-8 acts as an attractant to neutrophils and macrophages necessary to remove damaged myofibrils and stimulates new capillary formation essential to muscle repair and growth (Pedersen et al., 2007). IL-8 is also associated with delirium in adults in the ICU, and delirium significantly impacts patients' ability to participate in activity (van den Boogaard et al., 2011). Another myokine, muscle-derived IL-15, can stimulate accumulation of protein needed for muscle growth and decrease the rate of protein breakdown (Loell & Lundberg, 2011).

Systemic inflammation and critical illness–induced cytokines have been implicated in the pathological onset and severity of ICUAW (Bloch, Polkey, Griffiths, & Kemp, 2012; Lipshutz & Gropper, 2013). Sustained cytokinemia is associated with complications of multiple organ failure and chronic critical illness, including skeletal muscle derangements (Dimopoulou et al., 2008; Grander & Dunser, 2010). For example, proteolysis in muscle cells is enhanced or activated by tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), a cytokine commonly elevated in critical illness (Loell & Lundberg, 2011; Makowshi, 2012; Vesali et al., 2010). Researchers have reported that serum TNF-α, also known as cachexin, was increased in patients with reduced skeletal muscle cross-sectional area and peripheral muscle strength (Anker, Steinborn, & Strassburg, 2004; Frost & Lang, 2005; Kim, Cho, & Hah, 2012; Loell et al., 2011; Smart & Steele, 2011).

The purpose of this exploratory research was to determine the serum levels of three cytokines associated with skeletal muscle activation, damage, and repair—IL-8, IL-15, and TNF-α—among patients receiving mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hr and to examine the relationships between these cytokines and the outcomes of patient muscle strength, activities of daily living (ADLs), duration of mechanical ventilation, and length of ICU stay. We specifically hypothesized that IL-8 and IL-15 would be directly associated with increased activity and that elevated levels of TNF-α would be associated with reduced activity. In addition, because there is a potential link between muscle activity and cognition, we explored delirium as an outcome (Banerjee, Girard, & Pandharipande, 2011; Zaal & Slooter, 2012).

Method

In this prospective, repeated measures, exploratory investigation, participants were mechanically ventilated adults who received a once-daily progressive mobility protocol. We have reported the main findings and complete sample characteristics of the parent study elsewhere (Winkelman et al., 2012). The institutional review board approved the study and subsequent serum analyses, and all participants or their designated surrogates completed informed consent procedures. The overall consent rate for patients approached to participate in this study was 75%, with surrogates providing 96% of these consents. Parent study procedures included collection of blood samples at rest and after activity and data collection for delirium, muscle strength, ADL, duration of mechanical ventilation, and length of ICU stay.

The study was conducted in a medical intensive care unit (MICU) and a surgical intensive care unit (SICU) in an urban academic 700-bed medical center. Consecutive patients identified during daily rounding were approached for enrollment if they met the inclusion criteria of having received mechanical ventilation for ≥48 hr and there was no plan to extubate in the subsequent 48 hr. Patients were excluded from the study if they had neurological, muscular, or orthopedic disorders that precluded the possibility of progressive mobility. Patients with hospice care, who were judged moribund by the intensivist or who did not have a surrogate to provide consent were also excluded.

Subjects

All participants were orally intubated during the first day on which the intervention was delivered; we did not record airway status on subsequent days. For the seven participants who were discharged from the ICU before a third day of intervention, we imputed preactivity and postactivity cytokine values for the third day using the values obtained from Day 2 of the intervention to avoid reducing the sample size.

Procedure

After we obtained informed consent and determined physiologic status/stability, we negotiated a time of day for implementing the intervention with the subject and health care team members. We drew blood twice daily during the course of the 3-day intervention: Once immediately after a period of rest lasting at least 30 min and once immediately after administering the intervention, the goal of which was a period of activity lasting 20 min. Blood was collected into a 3.5-ml red-top Vacutainer™ tube using indwelling lines. Research staff members delivered the samples to the Clinical Research Unit (CRU) laboratory within 60 min of collection to minimize degradation of myokines. Staff in the CRU (supported by grant UL1TR 000439-06) separated clotted samples via centrifuge and stored serum at −80 °C in a monitored freezer. Archived serum for myokine biomarkers was stored for 9–12 months before these analyses, which was within the analytical stability period suggested by the manufacturer (www.mesoc-cale.com). Serum was processed in batches by a single individual blinded to the intervention.

We administered the intervention on the first day the patient demonstrated physiological stability for at least 4 hr. Physiological stability was defined as a partial pressure of arterial oxygenation fraction of inspired oxygen [P/F] ratio > 200, fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) < 60%, positive end expiratory pressure < 10 cmH2O, resting heart rate of 50–100 beats/min, mean arterial pressure of 60–100 mmHg, no active upward titration of intravenous vasopressor drugs (e.g., norepinephrine or dopamine), and peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) > 90% on current ventilator settings. Ventilator settings remained unchanged during data collection (period of rest and activity) and were not changed for at least 30 min before data collection began. Typically, the first day of intervention (and first blood sample collection) occurred on Day 6 of ICU hospitalization (standard deviation [SD] = 5; range = Days 2–12 following ICU admission).

Training of research staff to support intra- and interrater reliability occurred prior to and during the project. Staff delivered or assisted clinical staff in delivering the intervention. For example, if the intervention indicated passive range of motion (PROM), staff would place the patient in a semi-recumbent position with a backrest set at >45° and deliver a total of 20 min of PROM to the patient's four limbs. If the patient was eligible for sitting at the bedside or other out-of-bed activity, the staff would help assemble equipment and clinicians (e.g., nurse, respiratory therapist, and/or unlicensed assistive personnel) and assist with the activity, such as transferring the patient to a bedside chair or walking the patient. The intervention used in-bed and out-of-bed activities with demonstrated safety derived from published reports (Morris et al., 2008). All participants received an average (i.e., mean duration) of 20 min of protocolized activity. Type of activity (i.e., in bed or out of bed) was determined in consultation with the bedside nurse and physician.

All outcome data were collected by staff. Duration of mechanical ventilation and length of ICU stay were collected daily and verified at discharge from the ICU. Delirium and muscle strength data were collected on the day of planned ICU discharge. Information about ADLs was collected 24–48 hr after ICU discharge from either the participant or the surrogate. All data were collected between March 2012 and June 2011.

Measures

Quantification of IL-8, IL-15, and TNF-α

CRU staff prepared and analyzed the serum using an Meso Scale Discovery (MSD) multiplex antibody electrochemiluminescence approach (www.me-soscale.com). This technology has a reported sensitivity of 10 nanograms per deciliter (ng/dl), a range of 3–4.5 logs, and excellent precision when a standard calibration curve is generated, as was done in this project. All samples were tested in duplicate; duplicate intraassay coefficients of variation were <4%.

Delirium

We measured delirium with the confusion assessment method for ICU (CAM-ICU; Ely et al., 2001). The CAM-ICU is designed to detect acute cognitive changes and is scored as delirium present or delirium absent. A third value of unable to assess is also available. Staff were trained to administer the CAM-ICU using materials from Vanderbilt University's website (www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/icudelirium/assessment.html, accessed August 2009). Staff were initially evaluated for intra- and interrater reliability during training and then reevaluated every 6 months; we maintained agreement values of .95 or greater.

Muscle strength

To measure muscle strength, we used the manual muscle test (MMT) using limb muscles (Ali et al., 2008; Ciesla et al., 2011; De Jonghe et al., 2002; Hough, Lieu, & Caldwell, 2011). Three upper and three lower extremity muscle groups were graded with MMT: shoulder abduction, elbow flexion, wrist extension, hip flexion, knee extension, and ankle dorsiflexion. The MMT score for each muscle group ranges from 0 to 5. With six muscle groups tested, the total muscle strength score ranged from 0 to 30. A score of 30 indicated movement against gravity plus full resistance in all muscle groups and a score of 0 indicated no evidence of contractility in any muscle group (E. Fan et al., 2010). Intra- and interrater reliability of the MMT is reported at .97–.99 among trained personnel (Ciesla et al., 2011; E. Fan et al., 2010). Staff were trained by our physical therapist study consultant; initial evaluation occurred on a standard patient and re-evaluation occurred every 6 months on one patient per our consultant's advice; we maintained intra- and interrater reliability of .95.

ADLs

We assessed ADLs with the Katz Index of Independence in ADLs instrument, commonly referred to as the Katz ADL. The Katz ADL assesses the client's ability to independently perform bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring, and feeding as well as continence. Clients are scored as yes (1 point) or no (0 point) in each of the six functions (Katz, 1983), yielding a range of 0–6 as a total score. A score of 6 indicates full function, 4 indicates moderate impairment, and 2 or less indicates severe functional impairment (Shelkey &Wallace, 1998). Inter- and intrarater reliability is reported at .9 among trained personnel. Surrogate–patient agreement ranges from .7 to .9 (Shelkey & Wallace, 1998). Validity for use in acute care is supported in that independence is associated with a short length of stay (Brorsson & Asberg, 1984; Kresevic, 2012). We used this tool after participants were discharged from the ICU, as bathing, dressing, and toileting do not commonly occur daily in ICU patients and, typically, drainage devices (urinary catheters and fecal collection devices) prevent assessment of continence in the ICU. Feeding occurs via enteral or intravenous catheters among patients who are intubated; independent feeding assessment could not be performed in our enrollees. In our experience, most of the limitations on measuring ADLs in the ICU (e.g., tubes, lines, and lack of patient bathroom facilities) are not present in rooms to which patients are discharged after ICU. One member of the staff collected Katz ADL data after training by the principle investigator (PI). The PI observed these assessments for every tenth patient to maintain training.

Duration of mechanical ventilation

We measured duration of mechanical ventilation as the number of days a patient received mechanical ventilatory support. Staff reviewed medical records at 8 a.m. Monday through Friday to confirm days of mechanical ventilation, counting a full day of ventilation if the patient received mechanical support in more than 12 of the 24 hr immediately prior to the 8 a.m. data collection time. For example, if a patient was extubated at 12 noon and reintubated at 4 p.m., the entire day was counted as 1 day of mechanical ventilation. If the patient was extubated at 12 noon and remained extubated, the 4 hr of mechanical ventilation were not counted. On Mondays, medical records were reviewed to add both Saturday and Sunday days of mechanical ventilation.

Length of ICU stay

We calculated length of ICU stay in whole-day/24-hr increments starting at the time of admission. Patient records were used to determine admission time and length of ICU stay. These records were collected daily and verified on the day of discharge.

Intervention

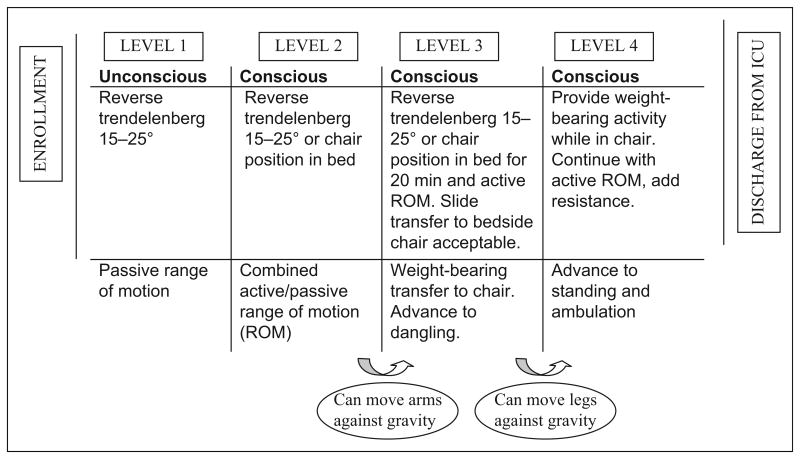

The intervention protocol is illustrated in Figure 1. Type of activity was categorized as in-bed (Levels 1 and 2) or out-of bed activities (Levels 3 and 4). Patients had to be able to follow three of the five commands and raise and hold arms and/or legs to progress to out-of-bed activity. If activity continued for more than 20 min, such as sitting in a chair after transfer, blood was collected at the 20-min mark.

Figure 1.

Early therapeutic mobility protocol. Adapted from “Early Intensive Care Unit Mobility in the Treatment of Acute Respiratory Failure,” by Morris et al., 2008, Critical Care Medicine, 36, pp. 2238–2243.

A typical enrollee participated with in-bed activity on Day 1 after enrollment, and overall 60% of activity occurred in bed. These in-bed activities included rolling, active or assisted range of motion, and bridge/slide to a chair. On Day 1, 20% of participants completed PROM only. On Day 2, one third of participants progressed to sitting at the edge of bed, standing and/or transferring from bed to chair with standing, with the remaining patients (66%) sitting in bed with activity. On Day 3, about 50% of patients were able to stand or walk at least four steps with or without assistance; another 20% were able to sit at the edge of the bed; and all others participated in activities while sitting in bed. No adverse events occurred during the intervention or immediately following activity in these 36 subjects.

Covariates

Because there is evidence that the cytokines of interest are influenced by several patient characteristics, we collected additional data for use as covariates, including age, gender, and body mass index (Akerstrom et al., 2005; Lamana et al., 2010; Martin, Viera, Petr, Marie, & Eva, 2006; Philippou et al., 2012). Covariates were entered into the statistical models as described subsequently.

Analyses

Each data collection tool was inspected for completeness and clarity after data collection and prior to data entry. The range for each variable was examined to determine whether there were any coding errors. After correction and validity checks, the edited data were stored without patient identifiers in a master database. Descriptive univariate statistics were calculated, including means, SDs, medians, and ranges using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 10 (www.ibm.com/software/analytics/spss).

Repeated-measures analysis of covariance (RM-ANCOVA) multivariate analyses were used to examine the influence of myokines on outcomes with Days 1, 2, and 3 postactivity serum values forming the repeated measures. The Statistical Analysis System (SAS Institute Inc., version 9, Cary, NC) procedure PROC MIXED was used to implement these analyses, with covariates of age, gender, and body mass index. An a of .10 was selected as significant in this exploratory study, particularly since the intervention has been supported as safe, feasible, and beneficial to similar patients (E. Fan, 2010).

Results

Characteristics of the 36 participants are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 66 (13.2) |

| Male gender | 20 (56%) |

| Race | |

| White | 20 (56%) |

| Black or African American | 16 (44%) |

| Illness severity on admission measured by APACHE 3 score | 76.5 (22.5) |

| Illness severity on first day of activity measured by P/F ratio | 225 (121.4) |

| Admitting unit | |

| MICU | 18 (50%) |

| SICU | 18 (50%) |

| Admitting diagnosis | |

| Pulmonary | 13 (36%) |

| Cardiovascular surgery | 5 (14%) |

| Sepsis | 7 (19%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 7 (19%) |

| Other (cancer, acute kidney injury, and vascular surgery) | 4 (11%) |

Note. N = 36. APACHE = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (version 3); ICU = intensive care unit; MICU = medical ICU; P/F ratio [PaO2:FiO2] = partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2):fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2); SICU = surgical ICU.

Myogenic cytokines IL-8, IL-15, and TNF-α

The daily mean, SD, median, and range of cytokine concentrations in serum from patients are detailed in Table 2. Within-subject variations did not reach significance for any of the three cytokines. None of the cytokines, using either the initial resting value on day of enrollment or daily values, were associated with ICU severity of illness, measured by Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (version 3; APACHE 3) scores on ICU admission. Only TNF-α values were significantly associated with type of activity (i.e., in bed vs. sitting at edge of bed or out of bed). Low TNF-a values in patients were associated with out-of-bed activity; conversely high TNF-α values in patients were associated with in-bed activity (F = 5.36,p = .02).

Table 2.

Descriptive and Change Values for Serum Cytokine Concentrations Before and After Activity.

| Cytokine (pg/ml) |

Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Change Score (SD) |

Evaluation of Change Score |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Preactivity | Postactivity | Change Score (SD) |

Preactivity | Postactivity | Change Score (SD) |

Preactivity | Postactivity | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Mean (SD) |

Median (range) |

Mean (SD) |

Median (range) |

Mean (SD) |

Median (range) |

Mean (SD) |

Median (range) |

Mean (SD) |

Median (range) |

Mean (SD) |

Median (range) |

|||||

| IL-8 pg/ml | 57.3 | 46.5 | 59.7 | 47.5 | −.2.4 | 57.0 | 45.4 | 56.7 | 44.45 | .27 | 55.7 | 52.9 | 58.1 | 53.6 | −2.4 | F = 1.422 |

| (34.3) | (13.9–177.0) | (35.9) | (15.8–177.0) | (12.1) | (31.7) | (13.9–140.0) | (33.9) | (15.8–159.0) | (2.7) | (27.4) | (13.9–1 16.0) | (32.0) | (15.8–159.0) | (10.1) | p = .248 | |

| IL-15 pg/ml | 9.3 | 8.5 | 9.4 | 8.7 | −.1 | 8.2 | 7.5 | 8.3 | 7.65 | −.1 | 7.6 | 6.6 | 7.9 | 7.0 | −.3 | F = 1.89 |

| (4.0) | (3.8–20.3) | (3.9) | (3.8–19.2) | (.8) | (3.5) | (3.5–16.6) | (3.5) | (3.97–16.40) | (−5) | (3.4) | (3.8–16.4) | (3.6) | (3.9-17.7) | (−6) | p = .158 | |

| TNF-α (pg/ml) | 8.0 | 6.9 | 8.1 | 6.8 | −.1 | 7.8 | 6.8 | 8.2 | 7.6 | −.4 | 7.7 | 6.8 | 7.9 | 7.4 | −.1 | F = 1.252 |

| (3.8) | (3.3–23.2) | (3.9) | (3.2–22.7) | (−6) | (4.1) | (3.5–23.2) | (4.4) | (3.2–23.5) | (1.1) | (4.2) | (3.3–23.2) | (3.9) | (3.8–22.7) | (−7) | p = .292 | |

Note. IL = interleukin; TNF = tumor necrosis factor; pg = picogram; ml = milliliter; TNF = tumor necrosis factor. Change score calculated as preactivity minus postactivity value.

Outcomes

Outcomes of delirium, muscle strength, ADL, duration of mechanical ventilation, and length of ICU stay are summarized in Table 3. Data met assumptions related to repeated-measures ANCOVA testing. While the sample was not randomly generated, repeated-measures ANCOVA is robust to a violation of this assumption (Corty, 2007, p. 416). We treated MMT composite scores as interval-level data because the value of 0 in this measure does mean that there is no muscle strength (Corty, 2007, p. 19). While most data were normally distributed, the MMT results were negatively skewed (−1.093, standard error .481), indicating that most participants had a low score. MMT vales had a kurtosis of 4.09 (standard error .953), suggesting longer tails than a standard distribution. However, the sample is large (N = 36) for repeated-measures ANCOVA, and when the sample size is large, ANCOVA is robust to violations of normality (Corty, 2007, p. 434).

Table 3.

Summary of Subject Outcomes Assessed at Discharge From the Intensive Care Unit (ICU).

| Outcome variable | Summary values |

|---|---|

| Delirium (n = 29) | |

| CAM-ICU negative = no delirium | n = 23 (64%) |

| CAM-ICU positive = delirium present | n = 6 (17%) |

| Unable to assess | n = 7 (19%) due to coma, sedation, or death |

| Muscle strength via MMT score (n = 23) | Mean = 25.4 (SD 3.0) |

| Unable to assess | n = 13 (36%) due to inability to follow directions (coma, confusion/delirium or sedation) or death |

| Activities of daily living via Katz ADL score (n = 32) | Mean = 2.8 (SD 2.0) |

| Independent (5–6) | n = 8 (22%) |

| Dependent (0–4) | n = 24 (67%) |

| Unable to assess | n = 4 (11%) due to death and transfer out of institution |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation (n = 36) | Mean = 9.75 days (SD 7.5) |

| Length of ICU stay (n = 36) | Mean = 15.9 days (SD 9.9) |

Note. N = 36. ADL = activities of daily living; CAM-ICU = confusion assessment method—ICU version; ICU = intensive care unit; Katz ADL = Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living instrument (score range 0–6, with 6 indicating independence in all activities); MMT = manual muscle testing (score range is 0–30, with 30 indicating normal strength against resistance); SD = standard deviation.

We were not able to measure the outcomes of delirium, muscle strength, or ADLs in all participants. Among the 23 participants in whom we measured muscle strength, 8 (35%) scored <24 on the MMT, and values consistent with ICUAW (De Jonghe et al., 2002; Stevens et al., 2009). Among the 32 participants in whom we measured ADLs, 24 (75%) were moderately to severely dependent in ADLs (i.e., KATZ score ≤4) the day after ICU discharge. Outcome data for delirium, muscle strength, and ADL were not collected in the three participants who died in the ICU. These patients had a period of worsening status, and the intervention was suspended at least 24 hr before their death.

Repeated postactivity IL-8 values and outcome measures

Repeated mean postactivity IL-8 serum values were significantly associated with Katz ADL score following ICU discharge (F = .34, p = .019) but not with muscle strength obtained at discharge, duration of mechanical ventilation, or length of ICU stay. For this analysis, the effect size had a moderate value at .21 and power was calculated at .88.

Repeated postactivity IL-15 values and outcome measures

There were no significant associations between repeated mean postactivity IL-15 serum values and outcomes. However, the association between repeated mean postactivity IL-15 serum values and muscle strength approached significance (F = 2.466, p = .11). The effect size was .68 and post hoc power was calculated at 51%.

Repeated postactivity TNF-α values and outcome measures

There were no significant associations between postactivity TNF-α values and outcomes in the model (F = .414, p = .66). The effect size was .012; observed power was .114.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report to examine the serum values of selected cytokines associated with skeletal muscle health in critically ill adults. Serum IL-8, IL-15, and TNF-α values were consistently elevated among participants compared to normal healthy adults and were also highly variable. Daily postactivity IL-8 serum values were positively associated with ADL scores following ICU discharge. The association between mean daily postactivity IL-15 serum values and muscle strength approached significance (p = .11), and there was an association between TNF-α level and type of activity (i.e., high TNF-α level was associated with low levels of activity). The latter finding suggests that elevated TNF-α may contribute to lack of progression in early mobilization. Another important outcome of the study is that our calculated effect sizes will allow for an accurate estimate of sample size for future studies examining the myokines IL-8, IL-15, and TNF-α in ICU patients.

Myokines released by contracting skeletal muscle create a local and systemic anti-inflammatory environment via paracrine and endocrine effects (Philippou et al., 2012). Several studies have reported changes in inflammatory response following exercise in healthy men and women and in community-dwelling adults with mild-to-moderate conditions including heart failure, cancer, diabetes, and obesity (Loell & Lundberg, 2011; Martinez-Hernandez et al., 2012; Mathers et al., 2012; Pedersen, 2009; Philippou et al., 2012; Yeo, Woo, Shin, Park, & Kang, 2012). Lack of progression in activity level among participants in the present study is one possible explanation for the lack of change in myokine levels pre- to postactivity. Unlike participants in the previous studies involving community-dwelling adults, 30% of participants in the present study did not make progress over the 3-day intervention (i.e., on Day 3, 30% of subjects were still participating in in-bed activity only). This lack of progression may have been the result of implementing a research protocol rather than a clinical protocol. We did not keep systematic data about why progress did not occur, though we did note that patients occasionally declined to participate.

The myokine values measured in participants in the present study exceeded the normal adult median value of 0 pg/dl (Martin et al., 2006). They were, however, lower than values measured in septic patient (Tefferi et al., 2011). In a report from an ICU setting, Dimopoulou et al. (2008) found that averaged serum values for IL-8 in septic patients were 82 pg/dl among survivors and 209 pg/dl among nonsurvivors. In the present study, we measured cytokines on the first day of the mobility intervention, typically 5 days after ICU admission. By contrast, the values in the previous study among septic patients were obtained on ICU admission. Further, sepsis was not the most common diagnosis among participants in the present study. These differences in protocol and diagnoses may explain why our values differ from other reports of critically ill adults.

Research has shown that serum levels of IL-8 increase in response to exhaustive exercise in healthy males (Pedersen & Febbraio, 2008). While the intervention in the present study was not designed to be exhaustive, it is also the case that most participants initially were not able to move both arms and legs sufficiently to meet the criteria for out-of-bed activity with potential exhaustive capacity. Perhaps adding resistance exercise to the intervention would increase the postactivity myokine serum levels and have a more measurable effect on muscle strength (Burtin et al., 2009; Zanni et al., 2010). For example, adding weights to a patient's wrists or ankles as they participate in range-of-motion exercises might influence the production of myokines and result in preserved muscle strength and function (Pedersen, 2011; Philippou et al., 2012).

Our finding of an association of postactivity IL-8 with ADL at discharge from the ICU suggests that IL-8 contributed to a systemic response (whole body movement or function). In a previous study, IL-8 demonstrated angiogenic effects (Frydelund-Larsen et al., 2007). These angiogenic effects may help increase muscle perfusion during critical illness. IL-8-induced angiogenesis might mitigate the ischemic effects of impaired blood flow from prolonged bed rest with local capillary compression. Perhaps serum IL-8 levels thus contribute to muscle system function (measured as ADLs) rather than limb muscle strength (measured with the MMT). Additional investigation comparing serum IL-8 levels with levels of IL-8 found in muscle tissue via muscle biopsy could refine our knowledge of the role of IL-8 in ICUAW.

Serum IL-15 values were elevated at baseline in the present study and showed a consistent but nonsignificant increase post-activity (Table 2). IL-15 expression is upregulated by resistance muscle training in healthy young adults (Nielsen et al., 2007). We did not test genetic expression of IL-15 in the present study, but we speculated that the nonresistance-type activities in our intervention did not sufficiently activate muscles to provide “spillover” of IL-15 into blood. Future research evaluating genetic expression would test this whether adding resistance exercises to the intervention might significantly affect IL-15 synthesis and muscle strength or function (Mathers et al., 2012; Needham, Truong, & Fan, 2009). Alternatively, a more sensitive or specific measure of muscle strength than MMT may be needed to determine associations between IL-15 and muscle weakness in the ICU setting.

We anticipated finding a correlation between elevated TNF-α values and reduced muscle strength in the present study since TNF-α has been linked to muscle loss and increased fatigue in heart failure patients (Anker & Sharma, 2002; Meyer et al., 2010). Our data did not support this hypothesis. However, high serum TNF-α levels were associated with a low level of activity. Patients with high levels of TNF-α may have had increased severity of illness or fatigue, leading to an inability to move beyond lower intensity or in-bed activity.

In previous reports, serum levels of cytokines correlated positively with the severity of ICU admission diagnosis, and prolonged cytokinemia was associated with complications of multiple organ failure, chronicity of critical illness, and mortality (Dimopoulou et al., 2008; Grander & Dunser, 2010). We did not find an association with severity of illness (i.e., APACHE 3 scores) in our small sample in the present study using the initial serum resting value in statistical modeling. The variety of admitting diagnoses among participants in the present is the most likely explanation for this discrepancy.

Limitations

The main limitations of the present study are the small sample size and the limited number of serial measurements of myokines. A related limitation is that there was only short-term follow-up of outcome measures. These limitations are common to early, exploratory investigations. One recommendation for future research in this area is to use animal or laboratory studies to test a maximized intervention. Alternatively, studies that compare myokine levels between participants receiving standard or nonprotocolized progressive mobility treatment and an activity protocol would be informative. Finally, our use of MMT limited the testing of muscle strength to subjects who could follow directions. Future studies could explore the use of alternative measures of muscle strength or measure muscle mass via ultrasound.

Conclusion

In the present study, we found no differences in serum myokine levels pre- to postactivity among patients who received a once-daily 20-min progressive mobility intervention, regardless of intensity (i.e., out of bed vs. in bed). These findings suggest that the once-daily interventions used in this study were not sufficiently exhaustive to alter myokine levels. The high variability of myokine levels and an unexpected lack of progression to maximal activity in this sample likely contributed to lack of significant findings.

We did, however, report the original finding of an association between higher postactivity serum IL-8 levels and independence in ADLs post-ICU discharge as measured by the Katz ADL. In addition, the post hoc effect sizes we calculated in the present study will contribute to calculating sample sizes necessary for future studies on myokines in ICU patient populations. Finally, our findings combined with the findings of previous studies suggest that clinicians and interventionists might increase the effectiveness of early progressive mobility protocols and further induce the production of myokines by adding resistance to in-bed activity when the patient is able to follow directions, increasing the duration of activity, or providing more than once-daily interventions.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: HILL-ROM (www.hill-rom.com) funded the parent study, including recruitment of the subsample who contributed serum for this report. The project was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health through grant UL1TR 000439-06.

Footnotes

Authors' Note: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Akerstrom T, Steensberg A, Keller P, Keller C, Penkowa M, Pedersen BK. Exercise induces interleukin-8 expression in human skeletal muscle. Journal of Physiology. 2005;563:507–516. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.077610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Ali NA, O'Brien JM, Jr, Hoffmann SP, Phillips G, Garland A, Finley JC Midwest Critical Care, C. Acquired weakness, handgrip strength, and mortality in critically ill patients. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2008;178:261–268. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200712-1829OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker SD, Sharma R. The syndrome of cardiac cachexia. International Journal of Cardiology. 2002;85:51–66. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00233-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anker SD, Steinborn W, Strassburg S. Cardiac cachexia. Annals of Medicine. 2004;36:518–529. doi: 10.1080/07853890410017467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A, Girard TD, Pandharipande P. The complex interplay between delirium, sedation, and early mobility during critical illness: Applications in the trauma unit. Current Opinion in Anesthesiology. 2011;24:195–201. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e3283445382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batt J, Dos Santos CC, Cameron JI, Herridge MS. Intensive care unit-acquired weakness: Clinical phenotypes and molecular mechanisms. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2013;187:238–246. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201205-0954SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch S, Polkey MI, Griffiths M, Kemp P. Molecular mechanisms of intensive care unit-acquired weakness. European Respiratory Journal. 2012;39:1000–1011. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00090011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brorsson B, Asberg KH. Katz Index of Independence in ADL. Reliability and validity in short-term care. Scandanavian Journal of Rehabiltion Medicine. 1984;16:125–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burtin C, Clerckx B, Robeets C, Ferdinande P, Langer D, Troosters T, Gosselink R. Early exercise in critically ill patients enhances short-term functional recovery. Critical Care Medicine. 2009;37:2499–2505. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a38937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla N, Dinglas V, Fan E, Kho M, Kuramoto J, Needham D. Manual muscle testing: A method of measuring extremity muscle strength applied to critically ill patients. Journal of Visualized Experiments. 2011;50:2632. doi: 10.3791/2632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corty EW. Using and interpreting statistics. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- De Jonghe B, Sharshar T, Lefaucheur JP, Authier FJ, Durand-Zaleski I, Boussarsar M Groupe de Reflexion et d'Etude des Neuromyopathies en, R. Paresis acquired in the intensive care unit: A prospective multicenter study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:2859–2867. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimopoulou I, Orfanos S, Kotanidou A, Livaditi O, Giamarellos-Bourboulis E, Athanasiou C, Armaganidis A. Plasma pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine levels and outcome prediction in unselected critically ill patients. Cytokine. 2008;41:263–267. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely EW, Margolin R, Francis J, May L, Truman B, Dittus R, Inouye SK. Evaluation of delirium in critically ill patients: Validation of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) Critical Care Medicine. 2001;29:1370–1379. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan E. What is stopping us from early mobility in the intensive care unit? Critical Care Medicine. 2010;38:2254–2255. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f8477d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan E. Critical illness neuromyopathy and the role of physical therapy and rehabilitation in critically ill patients. Respiratory Care. 2012;57:933–944. doi: 10.4187/respcare.01634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan E, Ciesla ND, Truong AD, Bhoopathi V, Zeger SL, Needham DM. Inter-rater reliability of manual muscle strength testing in ICU survivors and simulated patients. Intensive Care Medicine. 2010;36:1038–1043. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1796-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Guo Y, Li Q, Zhu X. A review: Nursing of intensive care unit delirium. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. 2012;44:307–316. doi: 10.1097/JNN.0b013e3182682f7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost RA, Lang CH. Skeletal muscle cytokines: Regulation by pathogen-associated molecules and catabolic hormones. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 2005;8:255–263. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000165003.16578.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydelund-Larsen L, Penkowa M, Akerstrom T, Zankari A, Nielsen S, Pedersen BK. Exercise induces interleukin-8 receptor (CXCR2) expression in human skeletal muscle. Experimental Physiology. 2007;92:233–240. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2006.034769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grander W, Dunser MW. Prolonged inflammation following critical illness may impair long-term survival: A hypothesis with potential therapeutic implications. Medical Hypotheses. 2010;75:32–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen T, Green C, Pedersen BK. Myokines in myogenesis and health. Recent Patents on Biotechnology. 2012;6:167–171. doi: 10.2174/1872208311206030167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hough CL, Lieu BK, Caldwell ES. Manual muscle strength testing of critically ill patients: Feasibility and interobserver agreement. Critical Care. 2011;15:R43. doi: 10.1186/cc10005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S. Assessing self-maintenance: Activities of daily living, mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 1983;31:721–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1983.tb03391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HC, Cho HY, Hah YS. Role of IL-15 in sepsis-induced skeletal muscle atrophy and proteolysis. Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases. 2012;73:312–319. doi: 10.4046/trd.2012.73.6.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresevic D. Assessment of physical function. In: Boltz M, Capezuti E, Fulmer T, Zwicker D, editors. Evidence-based geriatric nursing protocols for best practice. 4th. New York, NY: Springer; 2012. pp. 89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kress JP, Herridge MS. Medical and economic implications of physical disability of survivorship. Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2012;33:339–347. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1321983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacomis D. Neuromuscular disorders in critically ill patients: Review and update. Journal of Clinical Neuromuscular Disease. 2011;12:197–218. doi: 10.1097/CND.0b013e3181b5e14d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamana A, Ortiz AM, Alvaro-Gracia JM, Diaz-Sanchez B, Novalbos J, Garcia-Vicuna R, Gonzalez-Alvaro I. Characterization of serum interleukin-15 in healthy volunteers and patients with early arthritis to assess its potential use as a biomarker. European Cytokine Network. 2010;21:186–194. doi: 10.1684/ecn.2010.0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipshutz AK, Gropper MA. Acquired neuromuscular weakness and early mobilization in the intensive care unit. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:202–215. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31826be693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llano-Diez M, Renaud G, Andersson M, Gonzales Marrero H, Cacciani N, Engquist H, Larsson L. Mechanisms underlying intensive care unit muscle wasting and effects of passive mechanical loading. Critical Care. 2012;16:R209. doi: 10.1186/cc11841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loell I, Helmers SB, Dastmalchi M, Alexanderson H, Munters LA, Nennesmo I, Esbjornsson M. Higher proportion of fast-twitch (type II) muscle fibres in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies—Evident in chronic but not in untreated newly diagnosed patients. Clinical Physiology and Functional Imaging. 2011;31:18–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097X.2010.00973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loell I, Lundberg IE. Can muscle regeneration fail in chronic inflammation: A weakness in inflammatory myopathies? Journal of Internal Medicine. 2011;269:243–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makowshi GS. Cytokines in muscle damage. In: Philippou A, Maridaki M, Theos A, Koutsilieris M, editors. Advances in clinical chemistry. Vol. 58. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2012. pp. 49–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin K, Viera K, Petr C, Marie N, Eva T. Simultaneous analysis of cytokines and co-stimulatory molecules concentrations by ELISA technique and of probabilities of measurable concentrations of interleukins IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, CXCL8 (IL-8), IL-10, IL-13 occurring in plasma of healthy blood donors. Mediators of Inflammation. 2006;2006:65237. doi: 10.1155/MI/2006/65237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Hernandez PL, Hernanz-Macias A, Gomez-Candela C, Grande-Aragon C, Feliu-Batlle J, Castro-Carpeno J, Sanchez Garcia-Giron J. Serum interleukin-15 levels in cancer patients with cachexia. Oncology Reports. 2012;28:1443–1452. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers JL, Farnfield MM, Garnham AP, Caldow MK, Cameron-Smith D, Peake JM. Early inflammatory and myogenic responses to resistance exercise in the elderly. Muscle & Nerve. 2012;46:407–412. doi: 10.1002/mus.23317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer T, Stanske B, Kochen MM, Cordes A, Yuksel I, Wachter R, Herrmann-Lingen C. Elevated serum levels of interleukin-10 and tumor necrosis factor alpha [corrected] are both associated with vital exhaustion in patients with cardiovascular risk factors. Psychosomatics. 2010;51:248–256. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.51.3.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris PE, Goad ACT, Taylor K, Harry B, Passmore L, Haponik E. Early intensive care unit mobility in the treatment of acute respiratory failure. Critical Care Medicine. 2008;36:2238–2243. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318180b90e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needham DM, Truong AD, Fan E. Technology to enhance physical rehabilitation of critically ill patients. Critical Care Medicine. 2009;37:S436–S441. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b6fa29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen AR, Mounier R, Plomgaard P, Mortensen OH, Penkowa M, Speerschneider T, Pedersen BK. Expression of interleukin-15 in human skeletal muscle—Effect of exercise and muscle fibre type composition. Journal of Physiology. 2007;584:305–312. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.139618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen BK. The diseasome of physical inactivity—And the role of myokines in muscle–fat cross talk. Journal of Physiology. 2009;587:5559–5568. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.179515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen BK. Muscles and their myokines. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2011;214:337–346. doi: 10.1242/jeb.048074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen BK, Akerstrom TC, Nielsen AR, Fischer CP. Role of myokines in exercise and metabolism. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2007;103:1093–1098. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00080.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA. Muscle as an endocrine organ: Focus on muscle-derived interleukin-6. Physiology Review. 2008;88:1379–1406. doi: 10.1152/physrev.90100.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippou A, Maridaki M, Theos A, Koutsiliers M. Cytokines in muscle damage. Advances in Clinical Chemistry. 2012;58(no issue):49–97. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-394383-5.00010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schefold JC, Bierbrauer J, Weber-Carstens S. Intensive care unit-acquired weakness (ICUAW) and muscle wasting in critically ill patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Journal of Cachexia Sarcopenia and Muscle. 2010;1:147–157. doi: 10.1007/s13539-010-0010-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelkey M, Wallace M. Katz index of Independence in activities of daily living. Try this: Best practices in nursing care to older adults. 1998 Retrieved from http://consultgerirn.org/uploads/File/trythis/try_this_2.pdf.

- Smart NA, Steele M. The effect of physical training on systemic proinflammatory cytokine expression in heart failure patients: A systematic review. Congestive Heart Failure. 2011;17:110–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2011.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens RD, Marshall SA, Cornblath DR, Hoke A, Needham DM, de Jonghe B, Sharshar T. A framework for diagnosing and classifying intensive care unit-acquired weakness. Critical Care Medicine. 2009;37:S299–S308. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b6ef67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A, Vaidya R, Caramazza D, Finke C, Lasho T, Pardanani A. Circulating interleukin (IL)-8, IL-2R, IL-12, and IL-15 levels are independently prognostic in primary myelofibrosis: A comprehensive cytokine profiling study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:1356–1363. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.9490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Boogaard M, Kox M, Quinn KL, van Achterberg T, van der Hoeven JG, Schoonhoven L, Pickkers P. Biomarkers associated with delirium in critically ill patients and their relation with long-term subjective cognitive dysfunction; indications for different pathways governing delirium in inflamed and noninflamed patients. Critical Care. 2011;15:R297. doi: 10.1186/cc10598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesali RF, Cibicek N, Jakobsson T, Klaude M, Wernerman J, Rooyackers O. Protein metabolism in leg muscle following an endotoxin injection in healthy volunteers. Clinical Science (London) 2010;118:421–427. doi: 10.1042/CS20090332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber-Carstens S, Deja M, Koch S, Spranger J, Bubser F, Wernecke KD, Keh D. Risk factors in critical illness myopathy during the early course of critical illness: A prospective observational study. Critical Care. 2010;14:R119. doi: 10.1186/cc9074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiencek C, Winkelman C. Chronic critical illness: Prevalence, profile, and pathophysiology. AACN Advances in Critical Care. 2010;21:44–61. doi: 10.1097/NCI.0b013e3181c6a162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkelman C, Johnson KD, Hejal R, Gordon NH, Rowbottom J, Daly J, Levine AD. Examining the positive effects of exercise in intubated adults in ICU: A prospective repeated measures clinical study. Intensive Critical Care Nurse. 2012;28:307–318. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo NH, Woo J, Shin KO, Park JY, Kang S. The effects of different exercise intensity on myokine and angiogenesis factors. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 2012;52:448–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaal IJ, Slooter AJ. Delirium in critically ill patients: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Drugs. 2012;72:1457–1471. doi: 10.2165/11635520-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanni JM, Korpolu R, Fan E, Pradham P, Janjua K, Palmer JB, Needhan DM. Rehabilitation therapy and outcomes in acute repiratory failure: An observational pilot. Critical Care. 2010;25:254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]