Abstract

Based on their socioeconomic characteristics, Mexican immigrant men should have very high un-employment. More than half do not have a high school diploma. One in four works in construction; at the height of the recent recession, 20% of construction workers were unemployed. Yet their unemployment rates are similar to those of native-born white men. After controlling for education and occupation, Mexican immigrant men have lower probabilities of unemployment than native-born white men – both before and during the recent recession. I consider explanations based on eligibility for unemployment benefits, out-migrant selection for unemployment, and employer preferences for Mexican immigrant labor.

Keywords: unemployment, immigration, assimilation, labor market

1. Introduction

Based on their socioeconomic characteristics, Mexican immigrant men should have very high unemployment. In addition to the language and legal challenges that accompany the migration experience, Mexican immigrant men have, on average, low levels of education. According to the Current Population Survey (CPS), 60% of Mexican immigrant men do not have a high school diploma. In contrast, high school dropouts make up just 28% of native-born Mexican men, 13% of native-born black men, and less than 10% of native-born white men. Education matters because it is negatively associated with both the incidence and the duration of unemployment (Farber, 2004; Mincer, 1991). Education provides qualifications for employment, and it protects against job loss. During the most recent recession, 78% of the job losses were experienced by workers with a high school diploma or less, a group that constitutes less than half of the total workforce (Carnevale et al., 2012). Less than 5% of male workers in the U.S. are Mexican immigrants, yet they represent over 15% of male high school drop-outs in the U.S.1

There is at least one additional reason why Mexican immigrant men should have high unemployment: they are over-represented in construction, an industry that has frequent surges in unemployment. One in four Mexican immigrant men in the CPS works in construction, compared to 11% of native-born Mexican men, 12% of native-born white men, and 8% of native-born black men. During the Great Recession, construction workers were hit particularly hard. According to the CPS, nearly one-fifth of male construction workers were unemployed in 2009.2

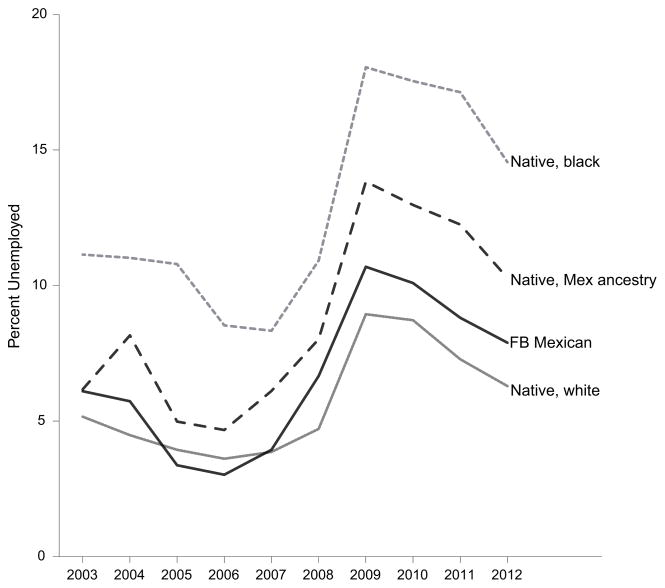

And yet, Mexican immigrant men have lower unemployment rates than both native-born Mexican and native-born black men (see Figure 1).3

Figure 1. Male unemployment rates by ethnicity, 2003 – 2012.

Source: Data come from the CPS-MORG files.

Note: Sample restricted to male workers in the labor force between the ages of 18 and 64 in their fourth interview.

Despite their lack of education, foreign-born Mexican men reached a recession peak unemployment rate of only 10.7%, a rate that is closer to the peak of 8.9% for native white men than the peak of 13.8% for native Mexican men. During the pre-recession period between 2005 and 2007, foreign-born Mexican men had lower unemployment than white men. Duncan et al. (2006) and Duncan and Trejo (2012) have noted that immigrant men with low levels of education have higher employment rates than similarly-educated native-born men. While Duncan et al. focus on employment (not unemployment), high employment and low unemployment together suggest that Mexican immigrant men have more favorable employment outcomes than their education would predict. What prior research has not yet empirically addressed are the reasons why so few Mexican immigrant men are unemployed. Given their lack of education and the disproportionate effects of recessions – especially the Great Recession – on the least educated (Elsby et al., 2011; Hoynes et al., 2012), Mexican immigrant men should have had exceptionally high unemployment during the Great Recession.

This is the most comprehensive analysis to date of potential explanations for the low unemployment rates among Mexican immigrant men. This is also the first investigation of the unemployment gap between native-born and Mexican immigrant men during the Great Recession, a recession that took unemployment to unprecedented heights (Hout et al., 2011). Consistent with prior economic research, I consider factors associated with employment, unemployment, and not being in the labor force. I take advantage of the extensive amount of employment information provided in the CPS to examine whether the data are consistent with theories about out-migrant selection for unemployment, disparities in reservation wages based on access to unemployment benefits, or employer preferences for non-citizen Mexican immigrant workers (most of whom are unauthorized to work in the United States). Prior research on disparities in male unemployment largely focuses on the concentration of unemployment among black men (Sampson, 1987; Wilson, 1987, 1996) and employer preferences for Hispanic immigrant men over native-born black men (Waldinger and Lichter, 2003). While low unemployment among immigrant men may seem inconsistent with sociological research on the ubiquity of joblessness among Mexican day laborers (Valenzuela, 2003), day laborers are a relatively small proportion of the foreign-born Mexican population, and their employment status is highly visible to the public. Though not often observed in public, unemployment among low-skill native-born men may be more prevalent.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Theories based on differences in reservation wages and eligibility for social insurance

Workers make employment decisions based on their labor market value and the costs associated with job-seeking (Lippman and McCall, 1976). Government transfers such as unemployment insurance may incentivize workers to accept unemployment by reducing the cost of not working (Feldstein, 1978). Gritz and MaCurdy (1997) find that those who take up unemployment insurance (UI) benefits have longer spells without employment than unemployed workers who do not receive benefits. While UI benefit eligibility rules vary by state, in general, UI benefits are only available to those who have worked over a specified period and at a minimum wage level for employers subject to U.S. unemployment compensation law.4 Even though they contribute to unemployment insurance through payroll taxes, unauthorized immigrants are not eligible for UI benefits. Migration scholars estimate that more than half of the Mexican immigrant population in the U.S. is unauthorized (Camarota, 2012; Hanson, 2006).

Immigrants from Mexico tend to have a low reservation wage (the minimum wage at which work will be accepted), in part because immigrants operate with a dual frame of reference, judging conditions in the receiving country relative to expectations in the sending country (Waldinger and Lichter, 2003). By increasing the cost of not working, exclusion from UI benefits may further reduce the reservation wage for Mexican immigrants. As a result, Mexican immigrants may be more likely than natives to seek out or accept part-time employment in lieu of being unemployed.

In this article, I refer to involuntary part-time employment as underemployment. The Bureau of Labor Statistics defines the underemployed as those who want and are available for full-time work but can only find part-time employment for economic reasons, such as slack demand for work or poor business conditions (Sum and Khatiwada, 2010). The deleterious effects of underemployment have received wide-spread media attention. Employers’ growing dependency on part-time labor has created a situation where there are now grocery store clerks who are not permitted to work more than 30 hours per week even after five years at the same store (Greenhouse, 2012) and full-time commercial drivers who are now restricted to a 30-hour work month (Cooper, 2012). Underemployment doubled during the second year of the recession, reaching roughly 6.5% in 2009 (Young, 2012). Lin (2011) finds that Mexican immigrant men – especially non-citizens – work fewer hours per week than non-Hispanic white workers, even after controlling for education, economic sector, union membership, and hourly versus salaried employment. What is not clear from prior research is whether Mexican immigrant men are voluntarily working fewer hours per week.

2.2. Demographic theories of migrant selection

Migration is inherently selective. The relatively low unemployment rates among Mexican immigrant men may indicate that they are self-selecting based on their capacity to find and maintain employment. Duncan and Trejo (2012) propose an employment model of migrant selectivity that takes into account immigrant-native employment differences by education level. Among workers with little education, Duncan and Trejo theorize that immigrants will have high employment relative to natives because less-skilled individuals who are unlikely to find work are better off staying in their home country and avoiding the costs of migration. In their study using data from the Mexican Migration Project, Cerrutti and Massey (2001) report that the most common reason for Mexican men to initiate migration to the U.S. is to find work. In Mexican communities where migration is common, there are strong expectations within families that teenage men should migrate to the U.S. to find work (Kandel and Massey, 2002).

There is a second selection mechanism that could be contributing to the low unemployment rates among Mexican immigrant men: out-migrant selection for unemployment. Prior research suggests that exposure to unemployment in the U.S. will increase the probability that a migrant will return home (Reyes, 2004; Van Hook and Zhang, 2011). Unauthorized immigrants may return to their native country because they are not eligible for unemployment benefits. Recent immigrants may be likely to return home after a period of unemployment because they tend to have smaller kinship networks than those who have been living in the U.S. for an extended period of time (Massey et al., 2003). There are also reasons to expect marital status to affect the propensity to selective out-migrate. Contrary to the household specialization model – which assumes that married men will focus more on work because they tend to carry the responsibility for generating income within a household (Becker, 1973, 2081) – married immigrant men with spouses in the U.S. may have higher unemployment than other immigrant men because they face greater costs of returning home.

Even when jobs are scarce, the reasons to stay may outweigh the reasons to leave. In their recent examination of attrition from the 1996 – 2009 CPS files, Van Hook and Zheng (2011) find that while unemployment is generally associated with out-migration for foreign-born adults in the CPS, being unemployed is not a predictor of out-migration for Mexican men between the ages of 18 and 64. Studies of pre-recession migration patterns using data from the Mexican Migration Project (MMP) find no association between unemployment in the U.S. and out-migration for Mexicans with authorization to work in the U.S. (Reyes, 2004). If Mexican immigrant men tend to return to their native country when the chances of getting a job are slim, then the return migration of Mexican men should increase during economic downturns. Yet the return migration of adult Mexican men declined during the Great Recession (Rendall et al., 2011; Van Hook and Zhang, 2011). Given the escalation of border patrol efforts since the 1980s, immigrants may choose to weather economic conditions in the U.S. rather than risk not being able to get back into the country (Hout et al., 2011; Massey, 2005; Massey et al., 2003).

2.3. Employer preferences for an immigrant workforce

In contrast with job search theories of workers as utility maximizers, the employer-based perspective focuses on firms as labor market creators. According to Osterman (1988) and Tilly (1996), firms create labor markets based on three objectives: cost minimization, flexibility, and predictability. The relative importance of these objectives is determined by the market for a firm’s product. When there is intense competition over prices, firms will pursue strategies that keep wages low. When demand is volatile, firms will seek to create a flexible workforce than can easily be laid-off and re-hired. Firms expecting steady growth in demand will focus on predictability, long-term hiring, and reducing turnover.

For example, during the reconstruction period following Hurricane Katrina in 2005, construction employers in New Orleans created entirely new low-cost, temporary labor markets. There are several reasons why post-Katrina employers recruited temporary migrant workers. First, firms that employ migrant workers can gain a competitive advantage because migrants have lower reservation wages. Brown et al. (2012) find that employing unauthorized workers increases a firm’s survival rate by 19%. Second, unauthorized migrant workers have no legal standing should they desire to protest work conditions. Employers can blame foreign recruiters for broken promises about work conditions or pay (Donato et al., 2007). Third, migrant workers are more likely than native workers to accept undesirable or hazardous work, such as asbestos and mold removal (Donato and Bankston, 2008; Hernandez-Leon, 2008). Even if employers do not have explicit plans for recruiting temporary or unauthorized workers, there is evidence to suggest that employers discriminate against natives for low-skill jobs. In their study of Latino immigrants in Los Angeles, Waldinger and Lichter (2003, p. 40) describe a tendency among employers to associate foreign-born Hispanics with desirable worker qualities, such as subordination and productivity. Waldinger’s (1997, p. 383) interviews with employers highlight the rationale behind managers’ preferences for immigrant labor: “Yes, the immigrants just want to work, work long hours, just want to do anything. They spend a lot of money coming up from Mexico. They want as many hours as possible. If I called them in for 4 hours to clean latrines, they’d do it. They like to work.”

To the extent that employer preferences depend on the business cycle, immigrant / native disparities in unemployment should vary over time. Employer preferences for temporary workers should change during a recession given that a recession affects the relative importance of cost minimization, flexibility, and predictability. Employers that experience falling demand during a recession may seek out immigrant labor as a way of reducing labor costs. If demand is not necessarily declining but more volatile as the result of a recession, then employers may try to make their labor force more flexible by hiring migrant workers. Indeed, the recent recession triggered an unprecedented increase in the number of guest workers from 1.7 million in 2009 to 2.8 million in 2010 (Massey, 2012).

This study is the first to explore potential reasons for the low unemployment rates among Mexican immigrant men. I consider explanations based on out-migrant selection for unemployment, differences in reservation wages based on access to unemployment benefits, and employer preferences for an immigrant workforce. First, if Mexican immigrants have low unemployment rates because they are more likely than natives to accept part-time work, then Mexican immigrants should have disproportionately high probabilities of underemployment (involuntary part-time employment) relative to their probability of unemployment. Second, I examine whether the data are consistent with the selective out-migration hypothesis by disaggregating married migrants based on whether or not they live with their spouses. If unemployed Mexican immigrant men have a tendency to return to Mexico, then those immigrants with spouses in the U.S. should have significantly higher unemployment because they face greater relocation costs. Finally, if Mexican immigrant unemployment rates reflect employer preferences for immigrant workers with little bargaining capacity, then non-citizen Mexican immigrants (most of whom are undocumented according to data from the Mexican Migration Project) should have the lowest probabilities of unemployment.5 If employers have greater incentives to prefer immigrants increase during periods of economic un-certainty, then the immigrant / native unemployment gap should have increased during the recent recession.

Unfortunately, given the data available in the CPS, I cannot rule out all of the alternative explanations associated with each of my hypotheses. Low unemployment among non-citizens does not necessarily mean that employer preferences are the primary determinant of immigrant / native unemployment disparities. Non-citizen Mexican immigrants may have lower reservation wages, or, they may be more likely to out-migrate when faced with unemployment. Still, if there is no variation in unemployment based on citizenship, then employer bias in favor of immigrant workers with little bargaining power is an unlikely explanations for the immigrant / native gap in unemployment.

3. Hypotheses

The optimal dataset for testing theories based on selection, reservation wages, and employer preferences would include responses from employers, as well as measures of worker employability, and job-seeking behavior among natives and immigrants across countries and over time. Given that such a dataset does not exist, I test hypotheses based on measures that are available in the CPS.

H1. Mexican immigrant men will be more likely to be underemployed (working part-time involuntarily) than native-born workers.

It may be that foreign-born Mexican men have low unemployment because ineligibility for unemployment benefits increases their likelihood of seeking out or accepting part-time employment in lieu of being unemployed.

H2. Contrary to the household specialization model, married Mexican men living with their spouses will have higher unemployment probabilities than single immigrant men and those not living with their spouses.

In general, being married reduces the odds of unemployment for men (Gorman, 1999; Lancaster and Nickell, 1980). According to the household specialization model, married men will focus more on work than single men because married men tend to carry the responsibility for income earning within a household (Becker, 1973, 2081). There is also research that suggests employers prefer married men over single men (Antonovics and Town, 2004; Korenman and Neumark, 1991). However, if Mexican immigrant men have a tendency to return to Mexico when faced with the prospect of unemployment, then Mexican immigrant men living with their spouses should have higher unemployment than other Mexican immigrant men because the costs of moving back to Mexico are greater for men with spouses in the U.S.

H3. The Great Recession exacerbated the gap in unemployment between non-citizen immigrant and native-born men.

While there are no direct measures of employer preferences in the CPS, I can examine whether Hypothesis 3 is consistent with variation in the probability of unemployment over time. Given that the relative cost of labor should matter more to employers during periods of economic uncertainty, then the immigrant / native unemployment gap should have increased during the recent recession.

4. Data and Methods

I test my hypotheses using data from the Current Population Survey (CPS), the source of the official U.S. monthly unemployment rate. The CPS is a monthly survey of approximately 60,000 households conducted by the Census Bureau for the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). I used the merged outgoing rotation group (MORG) files of the CPS instead of the CPS Annual March Demographic survey for three reasons: the MORG samples are larger, the March samples may be subject to seasonal or recall bias because they are administered once a year rather than monthly (Akerlof and Yellen, 1985; Horvath, 1982; Morgenstern and Barrett, 1974), and the MORG supplement is better suited for research on underemployment. Unlike the March survey, the MORG supplement includes a detailed question for part-time workers about their reasons for working part-time instead of full-time.

I use the 2003 – 2012 MORG files. This time period allows me to compare employment patterns before, during, and after the Great Recession. I do not include years prior to 2003 because of substantial changes to the occupation scheme in the CPS data. While the CPS is a monthly survey, new households are not interviewed each month. Households that enter the CPS are typically interviewed for four months, then ignored for eight months, then interviewed again for four more months. Households in months four and eight are considered the “outgoing rotation groups” because they are about to leave the observation sample (temporarily or permanently). To avoid observing respondents twice in one sample, I restrict my sample to respondents in their fourth interview. I further restrict this analysis to men between the ages of 16 and 64.

I use the BLS definition of unemployment: not currently working, have actively looked for work in the prior four weeks, and currently available for work.6 Those who are not working, available for work, have looked for a job during the past year but not during the past four weeks are considered by the BLS to be discouraged workers. My findings are not affected by whether I consider discouraged workers to be unemployed or not in the labor force. In the Results section, discouraged workers are considered to be not in the labor force. In the Appendix, I include results from models where discouraged workers are considered to be unemployed. In the CPS, discouraged workers represent just 2% of men ages 16–64 who are not in the labor force. Of those considered by the BLS to not be in the labor force, only 5.7% have looked for work in the last four weeks. Of that 5.7%, most report that they are either not available to work or that they do not want to work.

Similar to prior research on underemployment (Slack and Jensen, 2007), I use the BLS definition of an underemployed worker: an individual who is working part-time (less than 35 hours per week) who wants a full-time job and is available for full-time work, but can only find part-time work for economic reasons, such as slack demand for work at their firm, poor business conditions, or an inability to find a full-time job. This definition of underemployment excludes individuals who work part-time for other reasons, such as seasonal work or childcare responsibilities. The BLS classifies these individuals as voluntary part-time workers.

In all models I control for education, age, age squared, marital status, parental status, occupation (current or most recent occupation if unemployed or out of the labor force), and citizen status.7 Unemployment is concentrated among younger, less-educated workers. While the mechanisms linking family composition and unemployment are complex, the effect of marital status is clear from prior studies: compared to single men, married men have a much lower risk of unemployment. Given the research on employers’ preference for fathers (Correll et al., 2007), I expect fathers to have a lower risk of unemployment than childless men. Since most citizens are eligible for UI benefits, I expect citizens to have higher unemployment than non-citizens.

I use the 21-category CPS “two-digit” detail occupation recode based on the 2000 Census occupation codes.8 I use this occupation scheme because it identifies occupation groups that were disproportionately affected by the recent recession (e.g., construction). The more detailed Census 2000 occupation scheme, with more than 500 categories, would yield cell counts that are too small to quantify the effect of occupation on Hispanic immigrant employment patterns.

My race/ethnicity categories are: Mexico-born immigrant, other foreign-born Hispanic, native-born Mexican, native-born non-Mexican Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and other race or ethnicity. In all models, non-Hispanic immigrants are classified in the “other” race / ethnic category. I test my hypotheses about differential access to unemployment benefits by disaggregating Mexican immigrants based on citizenship. Those who were born abroad to American parents are designated as natives in my sample. All of the citizen immigrants in my sample became citizens through naturalization.

The dependent variable used to test Hypotheses 2 and 3 consists of three employment outcomes: not in the labor force, unemployed, and employed. The dependent variable used to test the underemployment hypothesis (H1) consists of five outcomes: not in the labor force, unemployed, involuntary part-time (underemployed), voluntary part-time, and full-time. Because my dependent variables consists of multiple unordered nominal categories, I estimate the outcome probability for individual i using a multinomial logit model:

where Xi is the matrix of explanatory variables and the β coefficients correspond to outcomes m and n.9

I use three different model specifications to test my hypotheses. First, I test whether foreign-born Mexican men have low unemployment because they are more likely to seek out or accept part-time employment by examining immigrant / native variation in involuntary part-time employment (underemployment). Second, if immigrant / native unemployment disparities reflect a tendency for Mexican immigrants to leave the country when faced with unemployment, then those who are living with their spouses should have higher unemployment than those who are single or not living with their spouses. Finally, I test whether immigrant / native employment gaps changed during the recent recession by comparing results from the pre-recession years of 2004 – 2006 to the recession years of 2008–2010.

Given the number of coefficients generated by multinomial logit models, I limit the presentation in the Results section to the coefficients and predicted probabilities associated with the outcomes of interest: unemployment and underemployment (versus full-time). In the Appendix, I include coefficients from the multinomial models. All models include state, metro/non-metro as well as month and year fixed effects to control for observed and unobserved geographic and temporal factors that give rise to differential rates of employment. Sample sizes and descriptives of the key covariates are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptives of CPS MORG data for men, 2003 – 2012.

| Percent Mexican immigrant | 6.3 |

| Percent Hispanic immigrant, non-Mexican | 3.1 |

| Percent native-born, Mexican ancestry | 4.4 |

| Percent native-born, non-Mexican Hispanic ancestry | 2.3 |

| Percent white (Non-Hispanic, non-immigrant) | 64.8 |

| Percent black (Non-Hispanic, non-immigrant) | 8.5 |

| Percent unemployed* | 6.4 |

| Percent of Mex immigrants unemployed | 6.7 |

| Percent of Hisp immigrants, non-Mex unemployed | 8.8 |

| Percent of native, Mex ancestry unemployed | 8.7 |

| Percent of native, non-Mex Hisp ancestry unemployed | 8.8 |

| Percent of white (non-Hisp, non-immigrant) unemployed | 5.5 |

| Percent of black (non-Hisp, non-immigrant) unemployed | 12.3 |

| Percent unemployed or discouraged** | 6.6 |

| Percent of Mex immigrants unemployed or discouraged | 6.7 |

| Percent of Hisp immigrants, non-Mex unemployed or discouraged | 8.9 |

| Percent of native, Mex ancestry unemployed or discouraged | 8.8 |

| Percent of native, non-Mex Hisp ancestry unemployed or discouraged | 8.9 |

| Percent of white (non-Hisp, non-immigrant) unemployed or discouraged | 5.6 |

| Percent of black (non-Hisp, non-immigrant) unemployed or discouraged | 12.6 |

| Percent underemployed (involuntary part-time) | 2.5 |

| Percent of Mex immigrants underemployed | 4.4 |

| Percent of Hisp immigrants, non-Mex underemployed | 4.2 |

| Percent of native, Mex ancestry underemployed | 3.6 |

| Percent of native, non-Mex Hisp ancestry underemployed | 3.1 |

| Percent of white (non-Hisp, non-immigrant) underemployed | 2.0 |

| Percent of black (non-Hisp, non-immigrant) underemployed | 3.3 |

| Percent not in the labor force (excluding discouraged workers) | 3.0 |

| Percent of Mex immigrants not in the labor force | 1.7 |

| Percent of Hisp immigrants, non-Mex not in the labor force | 2.2 |

| Percent of native, Mex ancestry not in the labor force | 3.2 |

| Percent of native, non-Mex Hisp ancestry not in the labor force | 3.3 |

| Percent of white (Non-Hispanic, non-immigrant) not in the labor force | 3.1 |

| Percent of black (Non-Hispanic, non-immigrant) not in the labor force | 3.8 |

| Controls | |

| Average age | 39.4 |

| Percent less than high school | 13.4 |

| Percent high school diploma or equivalent | 31.0 |

| Percent some college | 26.8 |

| Percent BA or higher | 28.8 |

| Percent married | 57.6 |

| Percent citizen | 89.3 |

| Percent construction and extraction | 11.5 |

| Total Sample Size | 535,613 |

Based on the BLS definition of unemployed (out of work, have actively looked for work during the past four weeks, and currently available for work)

The BLS defines discouraged workers as those who want a job, have looked for work during the past year but not during the past four weeks because 1) they believe no job is available in their line of work, 2) they had previously been unable to find work, 3) they lack the necessary training or experience, or 4) employers think they are too young or old or they face some other type of discrimination. The BLS definition of discouraged worker excludes those who provide reasons such as family responsibilities, school attendance, illness, and transportation problems for why they have not searched for work in the past four weeks.

Source: Data come from CPS MORG supplements.

Note: Weighted means presented. Sample restricted to non-military men ages 16–64 in their fourth interview.

Table 1 shows the distribution of unemployment and underemployment across racial and ethnic groups. Mexicans and non-Mexican Hispanics born in the U.S. have high unemployment relative to Mexican immigrants and non-Hispanic whites. Non-Mexican Hispanic immigrants have unemployment rates that are closer to the native-born Hispanic population than the Mexican immigrant population. Mexican immigrants have the lowest percentage (1.7%) of working-age adults not in the labor force. The racial and ethnic distribution of unemployment is not affected by whether I consider discouraged workers to be unemployed or out of the labor force.

5. Results

I first show results from a basic model that predicts employment status (not in the labor force, unemployed, or employed) after controlling for education, occupation (current or most recent), age, marital status, parental status, and citizen status. Logit coefficients predicting unemployment (versus full-time employment) are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Logit coefficients from multinomial logistic regression predicting unemployment (versus employment), 2003–2012

| Logit Coefficient | Standard Error | |

|---|---|---|

| Race and ethnicity (reference is non-immigrant, non-Hispanic white) | ||

| Mexican immigrant | −.24*** | (.04) |

| Hispanic immigrant, non-Mexican | .03 | (.04) |

| Native-born, Mexican ancestry | .14*** | (.03) |

| Native-born, non-Mexican Hispanic ancestry | .34*** | (.04) |

| Native, black | .78*** | (.02) |

| Other | .30*** | (.02) |

| H.S. diploma (reference is less than high school) | −.33*** | (.02) |

| Some college | −.52*** | (.02) |

| College degree | −.74*** | (.02) |

| Age | −.05*** | (.003) |

| Age squared | .001*** | (.00004) |

| Married | −.62*** | (.02) |

| Parental status (reference is parent, children not at home) | ||

| Parent, children at home | −.03 | (.02) |

| Not a parent | .05* | (.02) |

| Citizen | .21*** | (.03) |

| Construction (reference is Manager) | 1.16*** | (.03) |

| N = 535,613 | ||

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

Source: Author’s compilations. Data come from CPS MORG supplements.

Note: All models include controls for education, age, marital status, parental status, occupation (current or most recent if unemployed or out of the labor force), citizen status, as well as state, metro/non-metro, month, and year fixed effects to control for observed and unobserved geographic and temporal factors that affect employment outcomes. Sample restricted to men ages 16–64 in their fourth interview.

Once I take into account the low levels of education and occupational clustering of Mexican immigrant men, I find that their odds of being unemployed are lower than both native white men and native Hispanic men.10 Compared to native-born white men, black men have a much greater chance of being unemployed. Native-born Hispanic (Mexican and non-Mexican) men have a significantly higher likelihood of unemployment than native-born white men, although the gap between whites and native-born Hispanics is not nearly as large as the gap between whites and blacks. As expected, education, marriage, age, and being a parent all have protective effects against unemployment. Working in a construction occupation significantly increases the odds of unemployment. Citizens have a greater chance of being unemployed than non-citizens. There are many reasons non-citizens might have lower unemployment, including lower reservation wages, limited access to UI benefits, a tendency to leave the country when faced with unemployment, or employer preferences for a non-citizen workforce (I investigate these issues in more detail below). Table 3 below shows the results when I disaggregate Mexican immigrants based on citizen status.

Table 3.

Logit coefficients from multinomial logistic regression predicting unemployment (versus employment), Mexican immigrants disaggregated based on citizenship, 2003–2012

| Logit Coefficient | Standard Error | |

|---|---|---|

| Race and ethnicity (reference is native-born white) | ||

| Mexican immigrant | ||

| Non-citizen | −.46*** | (.03) |

| Citizen | −.21** | (.06) |

| Non-Mexican Hispanic immigrant | ||

| Non-citizen | −.19*** | (.04) |

| Citizen | .07 | (.07) |

| Native, Mexican ancestry | .14*** | (.03) |

| N = 535,613 | ||

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

Source: Author’s compilations. Data come from CPS MORG supplements.

Note: Model includes controls for education, age, marital status, parental status, occupation (current or most recent if unemployed or out of the labor force), as well as state, metro/non-metro, month, and year fixed effects to control for observed and unobserved geographic and temporal factors that affect employment outcomes. Sample restricted to men ages 16–64 in their fourth interview.

Non-citizen Mexican men have the lowest odds of unemployment. Mexican immigrant men who are citizens – most of whom should have access to UI benefits – have significantly lower unemployment odds than native-born white men. The odds of unemployment for non-Mexican Hispanic immigrant citizens are not significantly different from native-born whites.

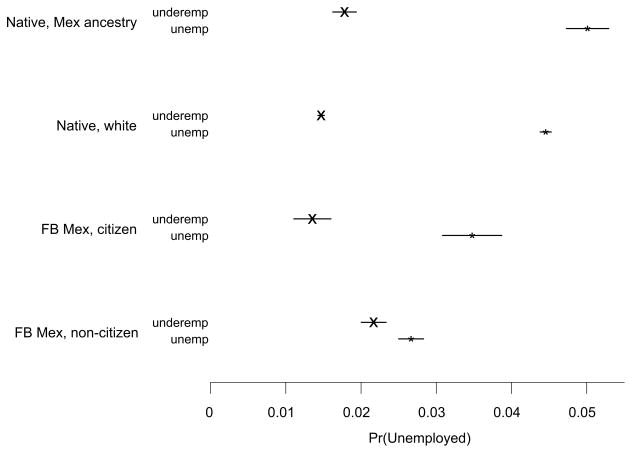

As a result of not having access to UI benefits, non-citizen immigrants may be more likely to seek out or accept part-time employment in lieu of being unemployed. Figure 2 below shows unemployment and underemployment (involuntary part-time) predicted probabilities from the model with the five-category dependent variable: not in the labor force, unemployed, voluntary part-time, involuntary part-time, and full-time.11 By holding the control variables at their means, I am essentially creating a hypothetical situation where foreign-born citizens, non-citizens, and natives have the same values on all the covariates, including education, occupation, and age.12

Figure 2. Predicted probabilities of unemployment and underemployment, 2003 – 2012.

Source: Author’s calculations. Data come from the CPS MORG supplements.

Notes: Model includes controls for education, age, marital status, parental status, occupation, as well as state, metro, month, and year fixed effects. Sample restricted to men ages 16–64 in their fourth interview.

As predicted by Hypothesis 1, foreign-born Mexican non-citizens have a higher probability of underemployment than native-born and foreign-born Mexican citizens. Mexican immigrants without citizenship are almost as likely to be underemployed as they are to be unemployed.13 Yet the underemployment hypothesis only holds for non-citizens. Why do Mexican immigrants with citizenship, most of whom should have access to unemployment benefits, have lower unemployment probabilities than their native-born counterparts?

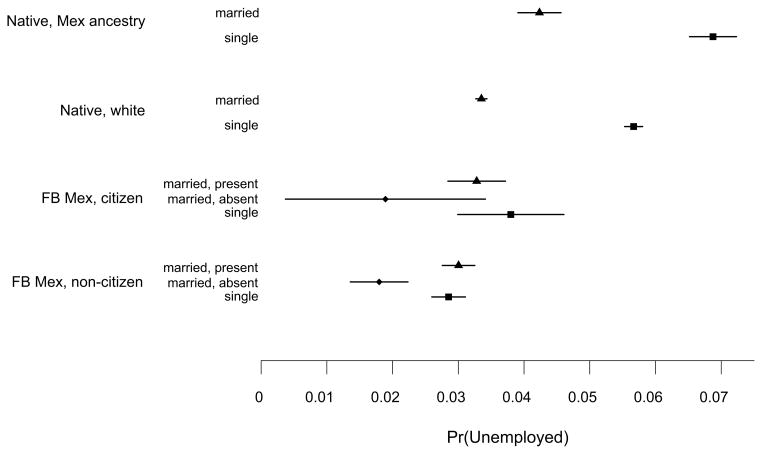

It may be that a large share of unemployed immigrants leave the country before they can be counted by the CPS. If this is the case, then I should see variation in unemployment based on propensity to out-migrate. Those immigrants living with spouses in the U.S. presumably have a lower propensity to out-migrate because they face a greater cost of relocating back to Mexico than single immigrants and immigrants with absent spouses. Figure 4 below shows the predicted probabilities of unemployment (holding all of the covariates at their mean) by ethnicity and marital status.14

Figure 4. Predicted probabilities of unemployment by ethnicity and time in the U.S., before and during the Great Recession.

Source: Author’s calculations. Data come from the CPS MORG supplements.

Notes: Model includes controls for education, age, marital status, occupation, as well as state, metro, and month-year fixed effects. Sample restricted to men ages 16–64 in their fourth interview.

Figure 3 shows how the effect of marital status on unemployment varies by immigrant status.15 For native-born men, being single (versus being married) significantly increases the odds of unemployment, as predicted by the household specialization model. Among immigrant men, single men and men who live with their spouses have statistically indistinguishable unemployment odds. In other words, single Mexican immigrant men (even those who are citizens and therefore most likely have access to unemployment benefits) have a much lower probability of unemployment than their marital status would predict.

Figure 3. Predicted probabilities of unemployment by marital status, 2003 – 2012.

Source: Author’s calculations. Data come from the CPS MORG supplements.

Notes: Model includes controls for education, age, parental status, occupation, as well as state, metro, month, and year fixed effects. Sample restricted to men ages 16–64 in their fourth interview.

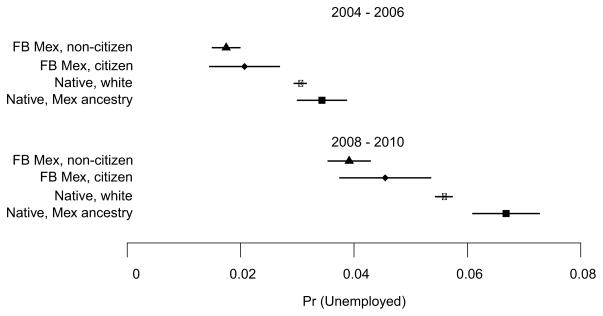

Another factor driving the low unemployment rates of Mexican immigrants may be employer preferences for an immigrant workforce. If employers have greater incentives to hire or retain immigrant workers during periods of economic uncertainty, then the immigrant / native unemployment gap should have increased during the recent recession. While there are no direct measures of employer preferences in the CPS, I can examine whether this hypothesis is consistent with variation in the probability of unemployment over time. Predicted probabilities from the models restricted to before the recession (2004 – 2006) and during the recession (2008 – 2010) are presented in Figure 4.

Mexican immigrant workers have consistently lower unemployment probabilities than native-born workers. Contrary to Hypothesis 3, there was not a sizeable increase in the unemployment gap between native-born white men and Mexican immigrant men during the recession. The group in Figure 5 with the largest increase in the predicted probability of unemployment during the recession was native-born Mexicans.16

6. Discussion

Given their average level of education and their over-representation in high-unemployment construction occupations, Mexican immigrant men should have very high unemployment rates. Yet their unemployment rates resemble those of native-born white men. After adjusting for socioeconomic characteristics (Table 2), I find that Mexican immigrant men have significantly lower unemployment probabilities than native-born men. While unemployment did increase for all groups during the Great Recession, Mexican immigrant workers consistently have lower unemployment probabilities than other workers (Figure 4). I explore three potential explanations: differences in reservation wages based on eligibility for social insurance, out-migrant selection for unemployment, and employer preferences for a migrant workforce. I first consider whether Mexican immigrant men, most of whom are excluded from unemployment benefits, have a greater tendency be working part-time involuntarily. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, I find that foreign-born Mexican non-citizens have a higher probability of involuntary part-time employment (underemployment) than native-born and foreign-born Mexican citizens (Figure 2). Compared to unemployment, however, underemployment is a less likely outcome.

Unemployment may be low among non-citizens because most of them cannot access unemployment benefits, but eligibility for social insurance cannot explain why Mexican immigrants with citizenship have such low unemployment probabilities compared to native-born men (Table 3, Figures 2–4). Figure 3 provides mixed support for selective out-migration (Hypothesis 2). On one hand, Mexican immigrant men with absent spouses have the lowest odds of unemployment. On the other hand, if propensity to leave the U.S. was the primary determinant of immigrant unemployment patterns, there should be more variation in unemployment based on spousal ties to the U.S. Figure 3 shows very small differences in immigrant unemployment probabilities based on marital status.

Given the limitations of the CPS, I cannot rule out employer preferences for the least assimilated immigrants or in-migrant selection for employment. Additional research and more data collection are needed in order to identify the causal mechanisms behind the patterns I observe. Are the immigrant groups with the lowest unemployment rates the most likely to accept job offers? Are they the most engaged in job search activities? Or do employers prefer immigrants because they have so few legal protections? As the number of temporary visas for agriculture workers has surged in recent years, so too has the number of legal complaints against agriculture employers for discriminating against native-born workers (Bronner, 2013). Economists and sociologists have documented the effects of immigration on black unemployment across cohorts and between cities (Borjas et al., 2010; Liu, 2013; Waldinger, 1997), but the extent of immigrant exploitation and discrimination against native-born workers within firms has yet to be examined. More qualitative and quantitative data at the firm-level might shed light on the causal mechanisms that are responsible for the low rates of Mexican immigrant unemployment.

While this study provides the most comprehensive examination of Mexican immigrant unemployment to date, there are limitations. As Hanson (2006, p. 884) writes, “data sources that include illegal immigrants are almost by definition subject to sample selection problems.” It is widely known that the CPS undercounts immigrants, particularly young, illegal and low-skill immigrants (Bean et al., 2001; Ibarraran and Lubotsky, 2007). If the undercounted have disproportionately high unemployment, then the low probabilities of Mexican immigrant unemployment may be an artifact of the over-representation of skilled immigrants in the CPS. If Mexican immigrant men are more likely than the native-born to report being employed when they are actually unemployed – perhaps because their permission to work in the U.S. is tied to their employment – then my estimates of immigrant unemployment would be understated. Nevertheless, if sampling bias was the primary mechanism behind my findings, then citizen immigrants should not have such low unemployment probabilities (Table 3). Sampling bias in the CPS cannot account for the fact that Mexico-born citizens have significantly lower unemployment than natives because citizens face no risk of deportation as a result of changes to their employment status, and there is no evidence to suggest that the Census Bureau undercounts citizen immigrants.

This paper presents two challenges for social scientists. First, my results on unemployment and labor force participation (Table A1) suggest rapid employment incorporation among Mexican immigrant men. Rather than asking what it is about immigrants that enables them to avoid unemployment, it may be more important to ask what it is about employers that makes them seek out a Mexican immigrant workforce. Second, while the high unemployment rates among native Mexicans might seem like evidence of downward assimilation, this analysis controls for the standard education and occupation indicators of assimilation. Even with a good job and a good education, second generation Mexican immigrant men are significantly more likely than their first generation counterparts to experience unemployment in the U.S.

Highlights.

I explore potential reasons for low rates of unemployment among Mexican immigrants.

Non-citizen Mexican immigrant men are over-represented among the underemployed.

The effect of marital status on employment outcomes varies by immigrant status.

Selection and employer preferences for migrant s are also plausible explanations.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NICHD training grant 5T32HD007543 to the Center for Studies in Demography and Ecology at the University of Washington. Thanks to Jake Rosenfeld, Stew Tolnay, Kyle Crowder, Herb Costner, Liz Ackert, as well as anonymous reviewers for insights on prior drafts of the paper. All errors are my own.

APPENDIX

Table A1.

Logit coefficients from multinomial logistic regressions, 2003–2012

| Base model: | Outcomes (relative to employed): | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployed | Not in the Labor Force | |||

| Logit Coefficient | Standard Error | Logit Coefficient | Standard Error | |

| Race and ethnicity (reference is non-immigrant, non-Hispanic white) | ||||

| Mexican immigrant | −.24*** | (.04) | −.53*** | (.06) |

| Hispanic immigrant, non-Mexican | .03 | (.04) | −.23** | (.07) |

| Native-born, Mexican ancestry | .14*** | (.03) | −.20*** | (.05) |

| Native-born, non-Mexican Hispanic ancestry | .34*** | (.04) | −.08 | (.06) |

| Native-born, Black | .78*** | (.02) | .26*** | (.03) |

| Other | .30*** | (.02) | .19*** | (.03) |

| H.S. diploma (reference is less than high school) | −.33*** | (.02) | −.41*** | (.02) |

| Some college | −.52*** | (.02) | −.20*** | (.02) |

| College degree | −.74*** | (.02) | −.61*** | (.03) |

| Age | −.05*** | (.003) | −.31*** | (.004) |

| Age squared | .001*** | (.00004) | .004*** | (.00005) |

| Married | −.62*** | (.02) | −.45*** | (.03) |

| Parental status (reference is parent, children not at home) | ||||

| Parent, children at home | −.03 | (.02) | −.32*** | (.03) |

| Not a parent | .05* | (.02) | .06 | (.03) |

| Citizen | .21*** | (.03) | .19*** | (.05) |

| Construction (reference is Manager) | 1.16*** | (.03) | .90*** | (.04) |

| Citizenship model: | ||||

| Race and ethnicity (reference is native-born white) | ||||

| Mexican immigrant | ||||

| Non-citizen | −.46*** | (.03) | −.77*** | (.06) |

| Citizen | −.21** | (.06) | −.35** | (.11) |

| Non-Mexican Hispanic immigrant | ||||

| Non-citizen | −.19*** | (.04) | −.41*** | (.07) |

| Citizen | .07 | (.07) | −.23* | (.11) |

| Native-born, Mexican ancestry | .14*** | (.03) | −.20*** | (.05) |

| Marital status model: | ||||

| Race and ethnicity (reference is married native-born white) | ||||

| Mexican immigrant non-citizen | ||||

| Single | .03 | (.06) | −.49*** | (.10) |

| Married - spouse present | .09 | (.06) | −.18 | (.10) |

| Married - spouse absent | −.44** | (.13) | −.33 | (.19) |

| Mexican immigrant citizen | ||||

| Single | .12 | (.11) | −.12 | (.18) |

| Married - spouse present | −.03 | (.07) | −.14 | (.13) |

| Married - spouse absent | −.60 | (.42) | −.90 | (.72) |

| Native-born, Mexican ancestry | ||||

| Married | .24*** | (.04) | .10 | (.07) |

| Single | .75*** | (.03) | .19*** | (.05) |

| Native-born, single white | .56*** | (.02) | .43*** | (.03) |

| Recession model: | ||||

| 2004 – 2006: race and ethnicity (reference is native-born white) | ||||

| Mexican immigrant | ||||

| Non-citizen | −.59*** | (.07) | −.88*** | (.10) |

| Citizen | −.40* | (.16) | −.20 | (.19) |

| Non-Mexican Hispanic immigrant | ||||

| Non-citizen | −.28** | (.10) | −.49*** | (.13) |

| Citizen | −.18 | (.18) | −.13 | (.05) |

| Native-born, Mexican ancestry | .12 | (.07) | −.16 | (.08) |

| 2008 – 2010: race and ethnicity (reference is native-born white) | ||||

| Mexican immigrant | ||||

| Non-citizen | −.38*** | (.05) | −.72*** | (.10) |

| Citizen | −.23* | (.10) | −.57** | (.20) |

| Non-Mexican Hispanic immigrant | ||||

| Non-citizen | −.11 | (.07) | −.54*** | (.14) |

| Citizen | .11 | (.10) | −.47* | (.22) |

| Native-born, Mexican ancestry | .19*** | (.05) | −.26** | (.08) |

| Age-at-arrival model: (reference is Mexican immigrant, arrived between 0 – 4 years old) | ||||

| Mexican Immigrant | ||||

| Arrived ages 5–9 | −.09 | (14) | −.31 | (.26) |

| Arrived ages 10–14 | −.22 | (.13) | −.25 | (.24) |

| Arrived ages 15–19 | −.35** | (.11) | −.15 | (.19) |

| Arrived ages 20–29 | −.17 | (.11) | .21 | (.19) |

| Arrived ages 30–39 | −.17 | (.13) | .19 | (.23) |

| Arrived ages 40+ | .001 | (.16) | .20 | (.26) |

| Native, Mex ancestry | .18 | (.10) | .33 | (.18) |

| Native, white | .04 | (.10) | .53** | (.17) |

| Native, African-American | .82*** | (.10) | .79*** | (.18) |

| Other race | .34** | (.10) | .45* | (.18) |

| N=535,613 | ||||

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

Source: Author’s compilations. Data come from CPS MORG supplements.

Note: All models include controls for education, age, marital status, citizen status, occupation, as well as state, metro/non-metro and month and year fixed effects to control for observed and unobserved geographic and temporal factors that give rise to differential rates of employment. Sample restricted to men ages 16–64 in their fourth interview.

Table A2.

Race / ethnicity logit coefficients from logistic regressions predicting unemployment, excluding those not in the labor force, 2003–2012

| Base model: | Discouraged workers = unemployed | Excluding discouraged workers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logit Coefficient | Standard Error | Logit Coefficient | Standard Error | |

| Race and ethnicity (reference is non-immigrant, non-Hispanic white) | ||||

| Mexican immigrant | −.23*** | (.04) | −.25*** | (.04) |

| Hispanic immigrant, non-Mexican | .03 | (.04) | .03 | (.04) |

| Native, Mexican ancestry | .13*** | (.03) | .14*** | (.03) |

| Native, non-Mexican Hispanic ancestry | .33*** | (.04) | .34*** | (.04) |

| Native, black | .79*** | (.02) | .78*** | (.02) |

| Other | .31*** | (.02) | .30*** | (.02) |

| Citizenship model: | ||||

| Race and ethnicity (reference is native-born white) | ||||

| Mexican immigrant | ||||

| Non-citizen | −.46*** | (.03) | −.47*** | (.03) |

| Citizen | −.20** | (.06) | −.21** | (.06) |

| Non-Mexican Hispanic immigrant | ||||

| Non-citizen | −.21*** | (.04) | −.20*** | (.04) |

| Citizen | .09 | (.07) | .07 | (.07) |

| Native, Mexican ancestry | .13*** | (.03) | .14*** | (.03) |

| N=518,830 | N=518,250 | |||

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

Source: Author’s compilations. Data come from CPS MORG supplements.

Note: All models include controls for education, age, marital status, occupation, citizen status, as well as state, metro/non-metro and month and year fixed effects to control for observed and unobserved geographic and temporal factors that give rise to differential rates of employment. Sample restricted to men ages 16–64 in their fourth interview.

Table A3.

Logit coefficients from multinomial logistic regressions without occupation as a control, 2003–2012

| Base model: | Outcomes (relative to employed): | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployed | Not in the Labor Force | |||

| Logit Coefficient | Standard Error | Logit Coefficient | Standard Error | |

| Race and ethnicity (reference is non-immigrant, non-Hispanic white) | ||||

| Mexican immigrant | −.17*** | (.04) | −.93*** | (.03) |

| Hispanic immigrant, non-Mexican | .08* | (.04) | −.59*** | (.03) |

| Native-born, Mexican ancestry | .20*** | (.03) | .05* | (.02) |

| Native-born, non-Mexican Hispanic ancestry | .36*** | (.03) | .31*** | (.02) |

| Native-born, Black | .77*** | (.02) | .66*** | (.01) |

| Other | .29*** | (.02) | .35*** | (.01) |

| H.S. diploma (reference is less than high school) | −.40*** | (.02) | −.92*** | (.01) |

| Some college | −.76*** | (.02) | −1.02*** | (.01) |

| College degree | −1.21*** | (.02) | −1.66*** | (.01) |

| Age | −.07*** | (.003) | −.30*** | (.002) |

| Age squared | .0008*** | (.00004) | .004*** | (.00002) |

| Married | −.65*** | (.02) | −.72*** | (.01) |

| Parental status (reference is parent, children not at home) | ||||

| Parent, children at home | −.04* | (.02) | −.51*** | (.01) |

| Not a parent | .05* | (.02) | −.04** | (.01) |

| Citizen | .14*** | (.03) | .04* | (.02) |

| Citizenship model: | ||||

| Race and ethnicity (reference is native-born white) | ||||

| Mexican immigrant | ||||

| Non-citizen | −.22*** | (.05) | −1.10*** | (.04) |

| Citizen | −.11 | (.06) | −.70*** | (.05) |

| Non-Mexican Hispanic immigrant | ||||

| Non-citizen | .03 | (.06) | −.80*** | (.04) |

| Citizen | .12 | (.07) | −.36*** | (.05) |

| Native-born, Mexican ancestry | .20*** | (.03) | .05* | (.02) |

| Marital status model: | ||||

| Race and ethnicity (reference is married native-born white) | ||||

| Mexican immigrant non-citizen | ||||

| Single | −.02 | (.05) | −.64*** | (.03) |

| Married - spouse present | .05 | (.04) | −.86*** | (.04) |

| Married - spouse absent | −.56** | (.02) | −1.45*** | (.11) |

| Mexican immigrant citizen | ||||

| Single | .25* | (.11) | −.15 | (.07) |

| Married - spouse present | .09 | (.07) | −.68*** | (.06) |

| Married - spouse absent | −.52 | (.42) | −1.97*** | (.40) |

| Native-born, Mexican ancestry | ||||

| Married | .29*** | (.04) | .14*** | (.03) |

| Single | .84*** | (.03) | .64*** | (.02) |

| Native-born, single white | .59*** | (.02) | .48*** | (.01) |

| Recession model: | ||||

| 2004 – 2006: race and ethnicity (reference is native-born white) | ||||

| Mexican immigrant | ||||

| Non-citizen | −.44*** | (.07) | −1.08*** | (.05) |

| Citizen | −.34* | (.16) | −.59*** | (.09) |

| Non-Mexican Hispanic immigrant | ||||

| Non-citizen | −.16 | (.10) | −.63*** | (.06) |

| Citizen | −.15 | (.17) | −.37*** | (.10) |

| Native-born, Mexican ancestry | .20** | (.06) | .06 | (.04) |

| 2008 – 2010: race and ethnicity (reference is native-born white) | ||||

| Mexican immigrant | ||||

| Non-citizen | −.23*** | (.05) | −1.02*** | (.05) |

| Citizen | −.12 | (.09) | −.71*** | (.08) |

| Non-Mexican Hispanic immigrant | ||||

| Non-citizen | .03 | (.07) | −.84*** | (.07) |

| Citizen | .16 | (.10) | −.41*** | (.09) |

| Native-born, Mexican ancestry | .24*** | (.05) | .03 | (.04) |

| N=640,262 | ||||

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

Source: Author’s compilations. Data come from CPS MORG supplements.

Note: All models include controls for education, age, marital status, citizen status, as well as state, metro/non-metro and month and year fixed effects to control for observed and unobserved geographic and temporal factors that give rise to differential rates of employment. Sample restricted to men ages 16–64 in their fourth interview.

Footnotes

I exclude women from this analysis for two reasons. First, the pathways into and out of employment vary by sex. Second, female employment is far more selective in Latin American countries than in the U.S. (Parrado and Flippen, 2005). Compared to native-born women, a much larger share of foreign-born Mexican women do not have any work experience (Tienda and Stier, 1996). Ethnographic research suggests that among Mexican immigrants in the U.S., female employment is often viewed as a temporary necessity for families in which the men have insufficient income (Parrado and Flippen, 2005).

Why focus on Mexican men as opposed to other immigrant groups? Based on their education and their occupational distribution, Mexican immigrants should have higher unemployment rates than other immigrant men. Compared to non-Mexican Hispanic and non-Hispanic immigrants, Mexican immigrant men have much lower levels of education (greater percentage of high school dropouts), and they are more heavily concentrated in the construction industry.

I use the tile package in R to produce the figures in this analysis (Adolph, 2012).

Legal permanent residents are eligible. Foreign employment is not covered by UI.

According to data from the MMP, approximately two-thirds of non-citizen immigrants from Mexico between 2003 and 2011 were undocumented (see mmp.opr.princeton.edu).

BLS employment definitions are available at http://www.bls.gov/cps/lfcharacteristics.htm.

While the intent of this analysis is to analyze Mexican immigrant unemployment after taking their concentration in construction into account, there may be reasons to not include occupation as a control variable in a model that predicts the odds of working. For example, 86% of the male workers in the CPS who are not in the labor force do not report an occupation. In the models that follow, I drop all respondents who are missing on occupation (97% of whom are not in the labor force). Table A3 in the Appendix shows model results without occupation as a control (the sample in Table A3 is larger because it includes individuals missing on occupation). Excluding occupation from the analysis does not affect the major findings of this article. When occupation is not taken into account, immigrant / native disparities in unemployment decrease slightly and Mexican immigrant men have a higher likelihood of being underemployed. These patterns are to be expected given the concentration of Mexican immigrant workers in construction occupations that have high rates of unemployment and in food preparation and cleaning occupations that have high rates of underemployment.

The 21 two-digit occupation categories are: business and financial operations; computer and mathematical science; architecture and engineering; life, physical, and social science occupations; legal occupations; education, training, and library occupations; arts, design, entertainment, sports, and media occupations; healthcare practitioner and technical occupations; healthcare support occupations; protective service occupations; food prep and serving occupations; building and grounds cleaning and maintenance; personal care and service; sales; office and administrative support; farming, fishing, and forestry; construction and extraction; installation, maintenance, and repair; production; transportation and material moving.

The independence of irrelevant alternatives assumption of multinomial logit requires that an individual’s probability of being in one outcome category relative to another outcome category should not change if a third (irrelevant) category is added to or dropped from the analysis (for example, there’s a chance that an individual’s probability of voting for a Democrat versus a Republican will change if a third-party candidate is added to the ballot). Thus, my choice of a multinomial logit model depends on the assumption that adding employment categories to the set of possible employment outcomes will not change the relative probabilities. For example, the multinomial logit model assumes that an individual’s probability of being unemployed versus underemployed (the ratio of two probabilities) is unaffected by whether I include “not in the labor force” as a possible outcome. In the Appendix, I present similar results from logistic regression models that are not constrained by the IIA assumption.

The lower unemployment probabilities for Mexican immigrant men are not driven by higher probabilities of being out of the labor force. Table A1 in the Appendix shows that Mexican immigrant men are significantly less likely than native-born whites to be out of the labor force.

Predicted probabilities generated using the STATA version 13 margins command.

Instead of controlling for citizen status in the models used to generate Figures 2–4, I create dummy variables based on ethnicity and citizen status (i.e., separate variables for non-citizen Mexican immigrant men and citizen Mexican immigrant men)

Results do not support the hypothesis that Mexican immigrant men have low unemployment because they are more likely to be working part-time voluntarily. The predicted probability of voluntary part-time employment for Mexican non-citizens and citizens is 10% and 11%, respectively, compared to 14% for native-born Mexicans and 16% for native-born white men.

Instead of controlling for marital status, I create dummy variables based on ethnicity and marital status (e.g., Mexican immigrant men with absent spouses).

If immigrant men living with spouses are married to U.S. citizens, then compared to other immigrants they may 1) have greater access to government transfers, 2) be less likely to out-migrate, or 3) be less preferable to employers who prefer the least assimilated immigrants. IPUMS has developed an algorithm to match spouses in the monthly CPS supplements through 2010 (King et al., 2010). According to 2003 – 2010 IPUMS CPS data for men in their fourth interview using the IPUMS algorithm for matching spouses, non-citizens constitute 78% of the spouses living with non-citizen Mexican immigrant men and 36% of spouses living with citizen Mexican immigrant men. Among Mexican immigrant men in the IPUMS CPS, non-citizen men living with non-citizen spouses have slightly lower unemployment and slightly higher employment rates than non-citizen men living with citizen spouses. These differences, however, become statistically indistinguishable in a regression analysis with control variables (results available upon request).

In separate analyses I disaggregated Mexican men by generation, comparing first, second, and third-plus generations. Both second and third generation Mexican men have significantly higher unemployment probabilities than foreign-born Mexican men. Second and third generation Mexican men have statistically indistinguishable unemployment probabilities.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adolph Christopher. tile. R package. 2012 faculty.washington.edu/cadolph/software.

- Akerlof George A, Yellen Janet L. Unemployment through the Filter of Memory. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1985;100:747–773. [Google Scholar]

- Antonovics Kate, Town Robert. Are All the Good Men Married? Uncovering the Sources of the Marital Wage Premium. American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings. 2004;94:317–321. [Google Scholar]

- Bean Frank D, Corona Rodolfo, Tuiran Rodolfo, Lafield Woodrow. Circular, Invisible, and Ambiguous Migrants: Components of Difference in Estimates of the Number of Unauthorized Mexican Migrants in the United States. Demography. 2001;38:411–422. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker Gary S. A Theory of Marriage: Part 1. Journal of Political Economy. 1973;81:813–846. [Google Scholar]

- Becker Gary S. A Treatise on the Family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2081. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas George J, Grogger Jeffrey, Hanson Gordon H. Immigration and the Economic Status of African-American Men. Economica. 2010;77:225–282. [Google Scholar]

- Bronner Ethan. The New York Times. 2013. May 6, Workers Claim Race Bias as Farms Rely on Immigrants. [Google Scholar]

- Brown J David, Hotchkiss Julie L, Quispe-Agnoli Myriam. Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Working Paper Series 2012. Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta; 2012. Does Employing Undocumented Workers Give Firms a Competitive Advantage? [Google Scholar]

- Camarota Steven A. Technical report. Center for Immigration Studies; 2012. Aug, Immigrants in the United States: A Profile of America’s Foreign-Born Population. [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale Anthony P, Jayasundera Tamara, Cheah Ban. Technical report. Georgetown Public Policy Institute; 2012. The College Advantage: Weathering the Economic Storm. [Google Scholar]

- Cerrutti Marcela, Massey Douglas S. On the Auspices of Female Migration from Mexico to the United States. Demography. 2001;38:187–200. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper Michael. Lost in Recession, Toll on Underemployed and Underpaid. The New York Times. 2012 Jun 18; [Google Scholar]

- Correll Shelley J, Benard Stephen, Paik In. Getting a Job: Is There a Motherhood Penalty? American Journal of Sociology. 2007;112:1297–1339. [Google Scholar]

- Donato Katharine M, Bankston Carl L. The Origins of Employer Demand for Immigrants in a New Destination: The Salience of Soft Skills in a Volatile Economy. In: Massey Douglas S., editor. New Faces in New Places: The Changing Geography of American Immigration. Russell Sage Foundation; 2008. pp. 124–148. [Google Scholar]

- Donato Katharine M, Trujillo-Pagan Nicole, Bankston Carl L, Singer Audrey. Reconstructing New Orleans after Katrina: The Emergence of an Immigrant Labor Market. In: Brunsma David L, Overfelt David, Steven Picou J., editors. The Sociology of Katrina. Rowan & Littlefield Publishers, Inc; 2007. pp. 217–234. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan Brian, Joseph Hotz V, Trejo Stephen J. Hispanics in the U.S. Labor Market. In: Tienda Marta, Mitchell Faith., editors. Hispanics and the Future of America. The National Academies Press; 2006. pp. 228–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan Brian, Trejo Stephen J. The Employment of Low-Skilled Immigrant Men in the United States. American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings. 2012;102:549–554. [Google Scholar]

- Elsby Michael WL, Hobijn Bart, Sahin Aysegul, Valleta Robert G. The Labor Market in the Great Recession – An Update to September 2011. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 2011 Fall [Google Scholar]

- Farber Henry S. Job Loss in the United States, 1981 to 2001. Research in Labor Economics. 2004;23:69–117. [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein Martin. The Private and Social Costs of Unemployment. The American Economic Review. 1978;68:155–158. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman Elizabeth H. Bringing Home the Bacon: Marital Allocation of Income-Earning Responsibility, Job Shifts, and Men’s Wages. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:110–122. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhouse Steven. The New York Times. 2012. Oct 27, A Part-Time Life, as Hours Shrink and Shift. [Google Scholar]

- Gritz R Mark, MaCurdy Thomas. Measuring the Influence of Unemployment Insurance on Unemployment Experiences. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics. 1997;15:130–152. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson Gordon H. Illegal Migration from Mexico to the United States. Journal of Economic Literature. 2006;44:869924. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Leon Ruben. Metropolitan Migrants: The Migration of Urban Mexicans to the United States. University of California Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath Frances E. Forgotten Unemployment: Recall Bias in Retrospective Data. Monthly Labor Review. 1982;150:40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Hout Michael, Levanon Asaf, Cumberworth Erin. Job Loss and Unemployment. In: Grusky David B, Western Bruce, Wimer Christopher., editors. The Great Recession. Russell Sage Foundation; 2011. pp. 59–81. [Google Scholar]

- Hoynes Hilary, Miller Douglas L, Schaller Jessamyn. Who Suffers During Recessions? Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2012;26:27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ibarraran Pablo, Lubotsky Darren. Mexican Immigration and Self-Selection: New Evidence from the 2000 Mexican Census. In: Borjas George J., editor. Mexican Immigration to the United States. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2007. pp. 159–192. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel William, Massey Douglas S. The Culture of Mexican Migration: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis. Social Forces. 2002;80:981–1004. [Google Scholar]

- King Miriam, Ruggles Steven, Trent Alexander J, Flood Sarah, Genadek Katie, Schroeder Matthew B, Trampe Brandon, Vick Rebecca. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, Current Population Survey: Version 3.0. [Machine-readable database] Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota Population Center [producer and distributor]; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Korenman Sanders, Neumark David. Does Marriage Really Make Men More Productive? Journal of Human Resources. 1991;26:282–307. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster Tony, Nickell Stephen. The Analysis of Re-Employment Probabilities for the Unemployed. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (General) 1980;143:141–165. [Google Scholar]

- Lin Ken-Hou. Do Less-Skilled Immigrants Work More? Examining the Work Time of Mexican Immigrant Men in the United States. Social Science Research. 2011;40:1402–1418. [Google Scholar]

- Lippman Steven A, McCall John J. The Economics of Job Search: A Survey. Economic Inquiry. 1976;14:155–189. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Cathy Yang. Latino Immigration and the Low-Skill Urban Labor Market: The Case of Atlanta. Social Science Quarterly. 2013;94:131–157. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S. Trade Policy Analyses no. 29. Washington, DC: Center for Trade Policy Studies, Cato Institute; 2005. Backfire at the Border: Why Enforcement Without Legalization Cannot Stop Illegal Immigration. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S. Immigration and the Great Recession. Stanford, CA: Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Durand Jorge, Malone Nolan J. Beyond Smoke and Mirrors: Mexican Immigration in an Era of Economic Integration. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mincer Jacob. NBER Working Paper. 1991. Education and Unemployment; p. 3838. [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern Richard D, Barrett Nancy S. The Retrospective Bias in Unemployment Reporting by Sex, Race, and Age. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1974;69:355–357. [Google Scholar]

- Osterman Paul. Employment Futures: Reorganization, Dislocation, and Public Policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Parrado Emilio A, Flippen Chenoa A. Migration and Gender among Mexican Women. American Sociological Review. 2005;70:606–632. [Google Scholar]

- Rendall Michael S, Brownell Peter, Kups Sarah. Declining Return Migration From the United States to Mexico in the Late-2000s Recession: A Research Note. Demography. 2011;48:1049–1058. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0049-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes Belinda I. Changes in Trip Duration for Mexican Immigrants to the United States. Population Research and Policy Review. 2004;23:235–257. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson Robert J. Urban Black Violence: The Effect of Male Joblessness and Family Disruption. American Journal of Sociology. 1987;93:348–382. [Google Scholar]

- Slack Tim, Jensen Leif. Underemployment Across Immigrant Generations. Social Science Research. 2007;36:1415–1430. [Google Scholar]

- Sum Andrew, Khatiwada Ishwar. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Monthly Labor Review. 2010. Nov, The Nation’s Underemployed in the “Great Recession” of 2007–2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tienda Marta, Stier Haya. Generating Labor Market Inequality: Employment Opportunities and the Accumulation of Disadvantage. Social Problems. 1996;43:147–165. [Google Scholar]

- Tilly Chris. Half a Job: Bad and Good Part-Time Jobs in a Changing Labor Market. Temple University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela Abel. Day Labor Work. Annual Review of Sociology. 2003;29:307–333. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hook Jennifer, Zhang Weiwei. Who Stays? Who Goes? Selective Emigration Among the Foreign Born. Population Research and Policy Review. 2011;30:1–24. doi: 10.1007/s11113-010-9183-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger Roger. Black/Immigrant Competition Re-Assessed: New Evidence From Los Angeles. Sociological Perspectives. 1997;40:365–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldinger Roger, Lichter Michael I. How the Other Half Works. University of California Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson William Julius. The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson William Julius. When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor. Knop; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Young Justin R. Underemployment in Urban and Rural America, 2005–2012. Carsey Institute, University of New Hampshire; 2012. Paper 179, http://scholars.unh.edu/carsey/179/, visited December 6, 2012. [Google Scholar]