Abstract

Objective

To assess principal investigators’ and study coordinators’ views and experiences regarding community consultation in a multi-center trial of prehospital treatment for status epilepticus conducted under an exception from informed consent for research in emergency settings.

Methods

Principal investigators and study coordinators at all 17 hubs for the Rapid Anticonvulsant Medication Prior to Arrival Trial (RAMPART) were invited to complete a web-based survey regarding community consultation at their site for RAMPART. Major domains included: 1) perceived goals of community consultation; 2) experiences with and views of community consultation methods used; 3) interactions with IRB regarding community consultation; and 4) general satisfaction and lessons learned. Descriptive statistics were tabulated for Likert scale data; relevant themes were reported for text-based data.

Results

Twenty-eight individuals (16 coordinators and 12 investigators) representing all 17 RAMPART hubs completed the survey. Respondents considered multiple community consultation goals to be important, with least support for the role of community consultation in altering study design. All sites used multiple methods (median= 5). The most widely used, and generally favored, method was attending previously scheduled meetings of existing groups. Respondents expressed frustration with low attendance and responsiveness at open public meetings.

Conclusions

Coordinators and investigators in this trial viewed community consultation efforts as successful but reported real challenges generating public interest. Individuals with the condition under study were found to be more engaged and supportive of the trial. Respondents endorsed numerous potential goals of the community consultation process and often combined methods to achieve these goals.

Keywords: Ethics, Bioethics, Research Ethics, Research in Emergency Settings, Community Consultation

INTRODUCTION

Barriers to consent when conducting prehospital research are unavoidable. Federal regulations allow an exception from informed consent (EFIC) for certain studies. However, before an EFIC study can be approved, investigators must consult both the geographic community where the study will be conducted and the community from which subjects will be drawn (condition-related community) (1, 2). The stated goals of community consultation are to notify the public, to offer an opportunity for input on the study, and to demonstrate respect for communities and potential enrollees. Community consultation remains unfamiliar to many researchers, and it can be time-consuming, expensive, and a barrier to research. Determining how to consult communities optimally and to the data generate remain challenges for investigators and IRBs (3).

Multiple consultation methods exist, ranging from interviews with key stakeholders and focus groups to open fora, presentation at community meetings, and population-based surveys. Different methods require different expertise, reach different populations, and involve varying levels of interaction with consultation participants. These methods likely yield different results and serve distinct goals. Though variations and potential limitations have been discussed, few data exist comparing experiences with different methods (4–6).

This project assessed experiences and perceptions of principal investigators and study coordinators in conducting community consultation for the Rapid Anticonvulsant Medication Prior to Arrival Trial (RAMPART), a Phase-III randomized trial of intramuscular midazolam versus intravenous lorazepam in prehospital treatment of status epilepticus conducted through the Neurological Emergencies Treatment Trials (NETT) Network (7).

METHODS

Study Design

All sites developed community consultation plans locally (8). We surveyed the principal investigator and coordinator at all 17 NETT hub sites regarding their views on and experiences with community consultation for RAMPART. Principal investigators and coordinators were both invited independently in order to ensure representation from all sites and to examine both investigator and coordinator perspectives. Answers were not shared with other respondents.

Participant Selection

Each principal investigator and coordinator was invited via email to complete an online survey after they had finished community consultation for RAMPART and submitted results to their IRB. Recruitment for this survey began in the summer of 2009. A second round of recruitment, for sites that had not previously completed community consultation, was conducted in April 2010.

Sample Size

No sample size calculation was performed, because the study sampled the universe of potential participants and had primarily descriptive goals.

Human Subjects Protections

This study was approved by the Emory University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB). Survey completion was considered to constitute consent.

Measurements

The survey (available at http://nett.umich.edu/nett/files/pi-sc_survey-_appendix_1.pdf) was developed by the authors. The content and phrasing were vetted by authors and members of the NETT human subjects protections working group. Major domains included: 1) perceived community consultation goals; 2) experiences with each method used for RAMPART; 3) IRB interactions regarding community consultation for RAMPART; and 4) satisfaction and lessons learned. Potential consultation goals listed were derived from federal guidance (2), published literature (9, 10), and interviews by one author (RP) with IRB representatives from NETT sites. The survey was designed to take 10–15 minutes and contained both closed and open-ended questions. A five-point response scale was used for most closed-ended items.

Analytic Methods

Descriptive statistics were tabulated in Microsoft Excel for closed-ended questions. Textual responses to open-ended questions were analyzed for content and grouped thematically. Pertinent themes were defined as those which represented novel concepts or were frequently mentioned. These themes were initially identified by ND and presented to the group for discussion. All authors had access to raw data, and thematic analysis was refined based on group discussion and consensus. ND and RP were primarily responsible for analysis.

On several occasions, a principal investigator and coordinator from a site answered questions differently. If one respondent mentioned using a method that the other did not, that method was included as one of the site’s methods. Responses to other questions were treated individually, though coordinator-investigator pairs were analyzed in order to identify role-related differences in views.

RESULTS

Twenty-eight individuals (16 coordinators, 12 principal investigators) representing all 17 NETT hubs completed the survey.

Perceptions of community consultation goals

Respondents were asked, regarding 11 potential goals, “How important do you think it is that community consultation efforts achieve each of the following potential goals?” There was broad agreement regarding importance of most goals (Table 1). The goals most frequently identified as less important related to the influence of community consultation on study design, such as enhancing benefits and minimizing risks.

Table 1.

Agreement with potential community consultation goals

| Goal | Importance (n=28) | |

|---|---|---|

| 5 Extremely Important |

Not at all Important 1 |

|

| Assess whether members of the community have significant concerns about the research study |

|

|

| Show respect for the community |

|

|

| Promote community trust in medical research |

|

|

| Educate the community about the research study |

|

|

| Determine if the research study is acceptable to the community |

|

|

| Identify particular sub-populations with concerns about the research study |

|

|

| Enlist the community’s support for the research study |

|

|

| Identify appropriate opt-out strategies for people who do not want to be included in the research study |

|

|

| Identify ways to improve protections for subjects included in the research study |

|

|

| Identify ways to minimize risks for subjects included in the research study. |

|

|

| Identify ways to enhance benefits for subjects included in the research study |

|

|

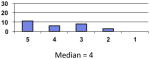

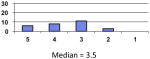

Methods Used

All hubs used more than one consultation method (range 2–6; median = 5; Table 2). The most commonly used method (16/17) was attending group meetings, defined as “regular meeting(s) of an existing group (e.g. on agenda for a church group, civic group, epilepsy foundation, etc.) that was not scheduled expressly for the purpose of CC.” Investigator-initiated meetings, defined as “special meeting(s) to discuss RAMPART to which you invited members of a particular group(s) to attend (e.g. church group, civic group, epilepsy foundation, etc.)” were used by 13/17 sites. Two sites reported using random-digit dialing surveys, and 3 sites conducted large surveys at public events or Emergency Departments. Aggregated, network-wide estimates of the total numbers of each type of event and numbers of participants have been previously reported (8).

Table 2.

Community Consultation methods used by site

| Site | Open public meetings | Existing Meetings | Investigator-Initiated Meetings | Focus groups | Telephone survey | In-person interviews | Booth-table | Other* | Total per site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | X | X | X | 3 | |||||

| 2 | X | X | X | 3 | |||||

| 3 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||

| 4 | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||||

| 5 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||

| 6 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||

| 7 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||

| 8 | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||||

| 9 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||

| 10 | X | X | 2 | ||||||

| 11 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||

| 12 | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||||

| 13 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||

| 14 | X | X | X | 3 | |||||

| 15 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |||

| 16 | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||||

| 17 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 | ||

| Total | 10 | 16 | 13 | 10 | 2 | 11 | 10 | 4 | 77 |

Methods listed as “other” included passing out flyers, media announcements, and attendance at a workshop for pastors.

Perceptions of the usefulness of each method, whether particular methods were worth the resources required, and challenges associated with each method are described in Table 3. No consistent differences were observed between study coordinators’ and investigators’ views of overall consultation success, the usefulness of particular methods, or the extent to which particular methods were worth the resources they required.

Table 3.

Community Consultation method-specific evaluations

| Method | # sites using method | How helpful? (median)* | Worth resources? (median)* | Ways helpful | Problems |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open meeting | 10 | 3 | 2 | Broad audience, direct feedback, assessment of support | Poor attendance; Difficulty explaining the study/having effective conversation; Can still be costly |

| Existing meeting | 16 | 4 | 5 | Targeted audience, better attendance, more knowledgeable population; Diversity across sessions, direct feedback, improved meeting dynamics relative to open meetings | Time constraints, getting invited and on the agenda, lack of diversity for a given group. |

| Investigator-initiated meetings | 13 | 4 | 4 | Targeted audience, direct feedback | Poor attendance, communication challenges |

| Focus Groups | 10 | 5 | 5 | Substantive feedback due to interactive, small group; useful for planning other community consultation and public disclosure; using 3rd party lessens influence by investigator | Expensive, concerns about representativeness, difficult to get conversation going, challenging to schedule, challenging to report |

| Phone Survey of random sample | 2 | 5 | 5 | Representativeness, quantitative description of views, IRB satisfaction | Once deployed, difficult to change; difficult to design instrument |

| In-person survey | 3 | 5 | 5 | Large, broad sample, short period of time, cost effective | Difficulty recruiting (particularly if no history/connection to seizure), Not 2-way communication |

| In-person interview | 11 | 4 | 5 | Helps get word out, generate support, access to community; Offers direct feedback. Helps to plan future CC. | One-on-one interviews are labor and time-intensive, self-selection |

| Booth/fair | 10 | 4.5** | 4 | Large numbers. Facilitates surveys or multiple short conversations. Gives public face of the study, “gets message out.” Can target population of interest (Seizure meetings) or hard-to reach populations | Lack of substance/depth of feedback due to distractions, short conversations, and high volume; dependent on event attendance |

Discussing the trial at community meetings was seen as helpful for soliciting direct feedback from different parts of a geographic community or from particular communities of interest. While generally considered worthwhile, commonly cited challenges with this method were getting space on agendas and not having time to adequately discuss the study.

There was low enthusiasm for town-hall style meetings. Many sites found them unhelpful and not worth the effort, primarily because of low attendance. Investigator-initiated meetings also suffered from low attendance; however, they were felt to provide useful, direct feedback from targeted audiences.

Survey methods were valued for gathering opinions from quantitatively meaningful numbers of individuals representing a cross-section of the community. In addition to targeting the geographic community, conducting surveys at events related to seizures was used to target condition-specific communities. Primary disadvantages cited related to less interaction and discussion with participants.

The use of booths or tables at large events (epilepsy symposia, job fairs, state fairs, etc.) was favorably viewed for reaching broad segments of the community, including individuals sometimes missed by other methods (young people, for example). This method was often used in conjunction with paper and pencil surveys and, in addition to allowing access to larger populations, was felt to be effective for educating the public. Primary disadvantages cited related to absence of interaction. Conversations were often short or interrupted, and attendance was variable.

Focus groups, used by over half the hubs, were felt to generate in-depth input due to small group size and opportunity for interaction. While some expressed concern that focus groups may limit diversity, one site reported purposive sampling in order to maximize representation from relevant geographic and condition-specific communities. The focus group method was nearly unanimously endorsed as helpful and worth the resources necessary.

Respondents using individual interviews also felt they received substantive input from consultants, and interviewing key stakeholders (e.g., civic leaders, pastors, etc.) was found to facilitate access to communities and help disseminate information about RAMPART within the community. The primary drawback was that interviewing is time-intensive and involves fewer individuals.

Community Consultation Impressions and Problems Encountered

The most commonly reported barriers related to accessing segments of the community (e.g., political leaders, religious groups, ethnic communities). In some instances, this was felt to be due to resistance or skepticism; other respondents felt there was little interest outside of the “seizure” community. Nevertheless, most principal investigators and coordinators felt their consultation efforts for RAMPART were successful; only 1 principal investigator and 3 coordinators were neutral. When asked what was most surprising about community consultation for RAMPART, the most common responses related to lack of interest within the general community and, in contrast, significant support and interest in the “seizure community.”

IRB interactions

Ten hubs reported IRB-required revisions to community consultation plans after initial review; only half felt these changes improved consultation. Three of 17 hubs reported that the IRB required additional consultation after reviewing initial results, 2 of whom felt this was unhelpful and reported 2 and 6 month delays in approval. The one hub that felt additional consultation was helpful estimated a delay of only 1 month. No IRB-required protocol changes were reported in response to community consultation. Four sites reported making changes to community consultation or public disclosure plans or on their own (not IRB-required) after initial consultation; one site reported making a change to the consent process used for continued participation in RAMPART after initial EFIC enrollment. The most common concerns regarding IRB interactions pertained to delays in protocol implementation and community consultation changes that were not felt to be helpful. Interestingly, 12/17 hubs reported that an IRB representative attended some or all community consultation sessions.

DISCUSSION

Advancing treatment for many emergency conditions requires EFIC, but the community consultation requirement remains a major challenge. This study is novel in assessing principal investigators’ and coordinators’ experiences regarding community consultation across a multi-center network. One important finding is that most sites used multiple methods (range 2–6, median =5). Some methods allow access to targeted portions of the community; others, such as random-digit-dialing sample specifically to represent the demographics of the geographic community; and methods allow differing levels of discussion and feedback. Many combinations were designed to produce a mix of population representation and depth of feedback.

Respondents considered numerous goals to be important. This study did not examine method-specific contributions toward particular goals or respondents’ prioritization among goals. However, because designing consultation to meet all potential goals would be prohibitively burdensome, these data reinforce the need for further study and consensus among researchers, ethicists, IRBs, and policy-makers regarding key goals and assessment metrics.

A specific finding echoing available literature is that open public meetings were often considered not worth the effort they required due to low turnout (11). Generating interest and finding individuals willing to talk about a study appear to be major challenges, as evidenced by the fact that 21 such events previously reported across the network involved only 256 participants (8). In contrast, respondents found attending existing meetings (particularly of seizure support groups) more productive. Several respondents reported being particularly impressed by the level of engagement and support within these consultation sessions. The critical challenge was ensuring enough time for meaningful discussion. Enthusiasm was also significant for focus groups and in-person interviews. These methods allow in-depth communication about a project, though it was recognized that they are labor-intensive, can be expensive, and involve fewer respondents. Surveys, which were conducted using random-digit dialing, over the internet, or at community events, were predictably favored for soliciting input from a broad cross-section of communities. An estimated 16,850 participants, for example, attended events where booths or tables for RAMPART were present, though the number of these participants who completed a survey or talked with presenters is unknown (8). Importantly, few hubs relied on surveys or large-group consultation methods alone, presumably recognizing that they provide less opportunity for substantive discussion.

A persistent question is how community consultation impacts study conduct and IRB review. In this sample, the most common IRB-requested change was further consultation. Respondents varied regarding how helpful IRB-directed changes were; 2 of 3 sites required to conduct more consultation, for example, reported substantial delays and did not find the additional consultation helpful. Notably, no respondent reported that an IRB required changes to the protocol itself in response to community consultation feedback, though one site made changes to the consent process (for continued participation after EFIC enrollment) on its own after community consultation. FDA guidance suggests that community consultation should be designed “to provide meaningful input to the IRB before its decision to approve, require modifications to, or disapprove the study (2).” The precise role of community consultation, however, in approval decisions or as a mechanism for identifying needed changes to a protocol is uncertain. Together, these findings underscore questions about the real impact of community consultation, questions that are particularly important given the expense and effort often required. Future studies correlating IRB members’, EMS providers’, and researchers’ perspectives on community consultation would be very valuable. Currently, very limited data exist regarding these important stakeholders’ views of community consultation (12–14).

This study has several limitations. First, it focused on community consultation for a trial testing two commonly used medications and a novel delivery mechanism. The views of investigators (or of IRB members) regarding necessary consultation may differ for studies involving placebo controls, experimental agents, or conditions lacking effective therapy. Second, this sample is small, though it captures the universe of sites across a large network and was designed as a descriptive study to appreciate the landscape of practice patterns and experiences of research teams. Third, our methodology did not allow in-depth exploration of experiences and views. Formal qualitative research involving in-depth interviews or focus groups could improve understanding of investigators’ and coordinators’ experiences. Finally, this study only assessed respondents’ perceptions of success. Actual consultation participants were not assessed, and no accepted, objective benchmarks of success exist.

Conclusion

While most published reports of community consultation come from the use of single methods, this study demonstrates that researchers commonly combine methods to achieve multiple goals. These data also highlight the difficulty of generating interest and engagement, particularly among the general public. Further research is needed to clarify the extent to which community consultation accomplishes the many goals it is designed to achieve and the extent to which it meaningfully impacts study design, conduct, and IRB review.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Information:

Dr. Dickert was supported during the study by a postdoctoral fellowship from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (1F32HL95358-1A1). Dr. Silbergleit was Principal Investigator of RAMPART and is co-investigator of the NETT Clinical Coordinating Center (CCC), both supported by the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U01NS056975 and U01NS059041). Ms. Harney is Human Subjects Coordinator for the NETT CCC.

We thank members of the NETT Human Subjects Protections’ Working Group for their insights regarding the design and conduct of this study. We particularly thank Dr. Jill Baren and Dr. Michelle Biros for very helpful comments regarding prior versions of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Dr. Neal W Dickert, Emory University School of Medicine, Division of Cardiology; Rollins School of Public Health, Department of Epidemiology; and Atlanta Veterans’ Affairs Medical Center. Atlanta, GA.

Dr. Prasanthi Govindarajan, University of California San Francisco School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, San Francisco, CA.

Ms. Deneil Harney, University of Michigan School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Ann Arbor, MI.

Dr. Robert Silbergleit, University of Michigan School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Ann Arbor, MI.

Dr. Jeremy Sugarman, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Department of Medicine and Berman Institute of Bioethics, Baltimore, MD.

Dr. Kevin P Weinfurt, Duke University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Durham, NC.

Dr. Rebecca D Pentz, Pentz- Emory University School of Medicine, Winship Cancer Institute, Atlanta, GA.

References

- 1.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Title 21 (Code of Federal Regulations), Part 50.24 Protection of Human Subjects. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Institutional Review Boards, clinical investigators, and sponsors: Exception from informed consent requirements for emergency research. Rockville, MD: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2013. [cited 2013 August 18, 2013]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM249673.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tisherman S, Powell J, Schmidt T, Auferheide T, Kudenchuk P, Spence J, et al. Regulatory challenges for the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium. Circulation. 2008;118:1585–92. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.764084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Contant C, McCullough LB, Mangus L, Robertson C, Valadka A, Brody B. Community consultation in emergency research *. Critical care medicine. 2006;34(8):2049–52. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000227649.72651.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson M, Schmidt TA, DeIorio NM, McConnell KJ, Griffiths DE, McClure KB. Community consultation methods in a study using exception to informed consent. Prehospital emergency care: official journal of the National Association of EMS Physicians and the National Association of State EMS Directors. 2008;12(4):417–25. doi: 10.1080/10903120802290885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramsey CA, Quearry B, Ripley E. Community consultation and public disclosure: preliminary results from a new model. Academic emergency medicine: official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2011;18(7):733–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01102.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silbergleit R, Durkalski V, Lowenstein D, Conwit R, Pancioli A, Palesch Y, et al. Intramuscular versus Intravenous Therapy for Prehospital Status Epilepticus. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366(7):591–600. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silbergleit R, Biros MH, Harney D, Dickert N, Baren J. Implementation of the exception from informed consent regulations in a large multicenter emergency clinical trials network: the RAMPART experience. Academic emergency medicine: official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2012;19(4):448–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01328.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickert N, Sugarman J. Ethical Goals for Community Consultation in Research. American journal of public health. 2005;95(7):1123–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.058933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richardson LD, Quest TE, Birnbaum S. Communicating with Communities about Emergency Research. Academic emergency medicine: official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2005;12(11):1064–70. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baren JM, Biros M. The research on community consultation: an annotated bibliography. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2007;14(4):346–52. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deiorio NM, McClure KB, Nelson M, McConnell KJ, Schmidt TA. Ethics committee experience with emergency exception from informed consent protocols. Journal of empirical research on human research ethics: JERHRE. 2007;2(3):23–30. doi: 10.1525/jer.2007.2.3.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McClure KB, Delorio NM, Schmidt TA, Chiodo G, Gorman P. A qualitative study of institutional review board members’ experience reviewing research proposals using emergency exception from informed consent. Journal of medical ethics. 2007;33(5):289–93. doi: 10.1136/jme.2005.014878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ripley E, Ramsey C, Prorock-Ernest A, Foco R, Luckett S, Jr, Ornato JP. EMS providers and exception from informed consent research: benefits, ethics, and community consultation. Prehospital emergency care: official journal of the National Association of EMS Physicians and the National Association of State EMS Directors. 2012;16(4):425–33. doi: 10.3109/10903127.2012.702189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.