Abstract

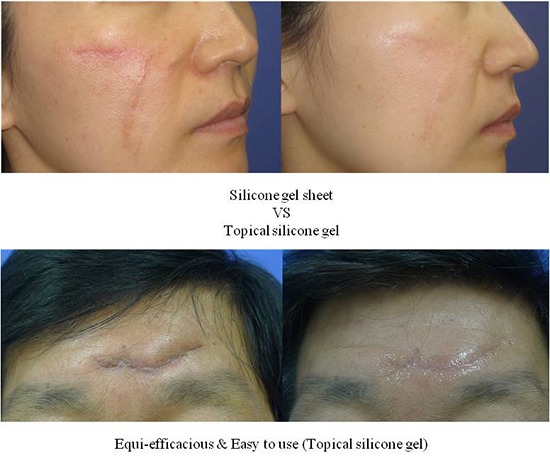

To date, few studies have compared the effectiveness of topical silicone gels versus that of silicone gel sheets in preventing scars. In this prospective study, we compared the efficacy and the convenience of use of the 2 products. We enrolled 30 patients who had undergone a surgical procedure 2 weeks to 3 months before joining the study. These participants were randomly assigned to 2 treatment arms: one for treatment with a silicone gel sheet, and the other for treatment with a topical silicone gel. Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) scores were obtained for all patients; in addition, participants completed scoring patient questionnaires 1 and 3 months after treatment onset. Our results reveal not only that no significant difference in efficacy exists between the 2 products but also that topical silicone gels are more convenient to use. While previous studies have advocated for silicone gel sheets as first-line therapies in postoperative scar management, we maintain that similar effects can be expected with topical silicone gel. The authors recommend that, when clinicians have a choice of silicone-based products for scar prevention, they should focus on each patient's scar location, lifestyle, and willingness to undergo scar prevention treatment.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: Cicatrix, Postoperative Period, Wounds and Injuries, Prevention and Control

INTRODUCTION

Silicone-based products are widely used to limit pathologic scars. Using these products is cost- and time-effective, as well as more convenient and comfortable for patients. To date, a substantial number of studies have assessed the efficacy of these products in preventing scars, but have reached no definitive conclusions. However, in certain randomized, controlled studies, these products were significantly effective in reducing postoperative incision wound scarring (1, 2, 3, 4). Currently, several types of silicone-based products are available for clinical use (5). Of these, silicone gel sheets and topical silicone gels are the most popular forms (5, 6, 7). However, both have known limitations and can be inconvenient for patients to use, thus posing a risk of to misuse or treatment interruption. Specifically, silicone gel sheets are disadvantageous because they cannot be applied to mobile or visible areas of the body, and require additional taping or bandaging (3, 4). Moreover, the sheets cannot achieve and maintain adequate contact with scars when applied to the skin with an irregular contour (3). On the other hand, topical silicone gels take time to completely dry (4). Furthermore, patients have to take extra sunsceen precautions to prevent hyperpigmentation, and must also apply topical silicone gels to scars multiple times per day (4, 8). Few studies have compared the effectiveness of topical silicone gels to that of silicone gel sheets in surgical scar prevention. Consequently, we conducted this prospective study to examine both the efficacy and the convenience of each product.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and study design

This study enrolled 30 patients between January and November 2012. Participant inclusion criteria were as follows:

History of surgery 2 weeks to 3 months before enrollment

Scarring of a surface area <10×10 cm2

Age 18 yr or older

Exclusion criteria were as follows:

Any infection

Any wound producing a significant amount of discharge, e.g., still requiring a dressing 2 weeks after surgery or lacking visible signs of normal epithelialization

Any systemic disease (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hematologic disorder, or dermatologic disorder)

Use of anticancer, psychiatric, or steroid medication

Psychiatric disorder

Deemed unable to complete the study according to the judgment of the authors.

Evaluation criteria and outcome measures

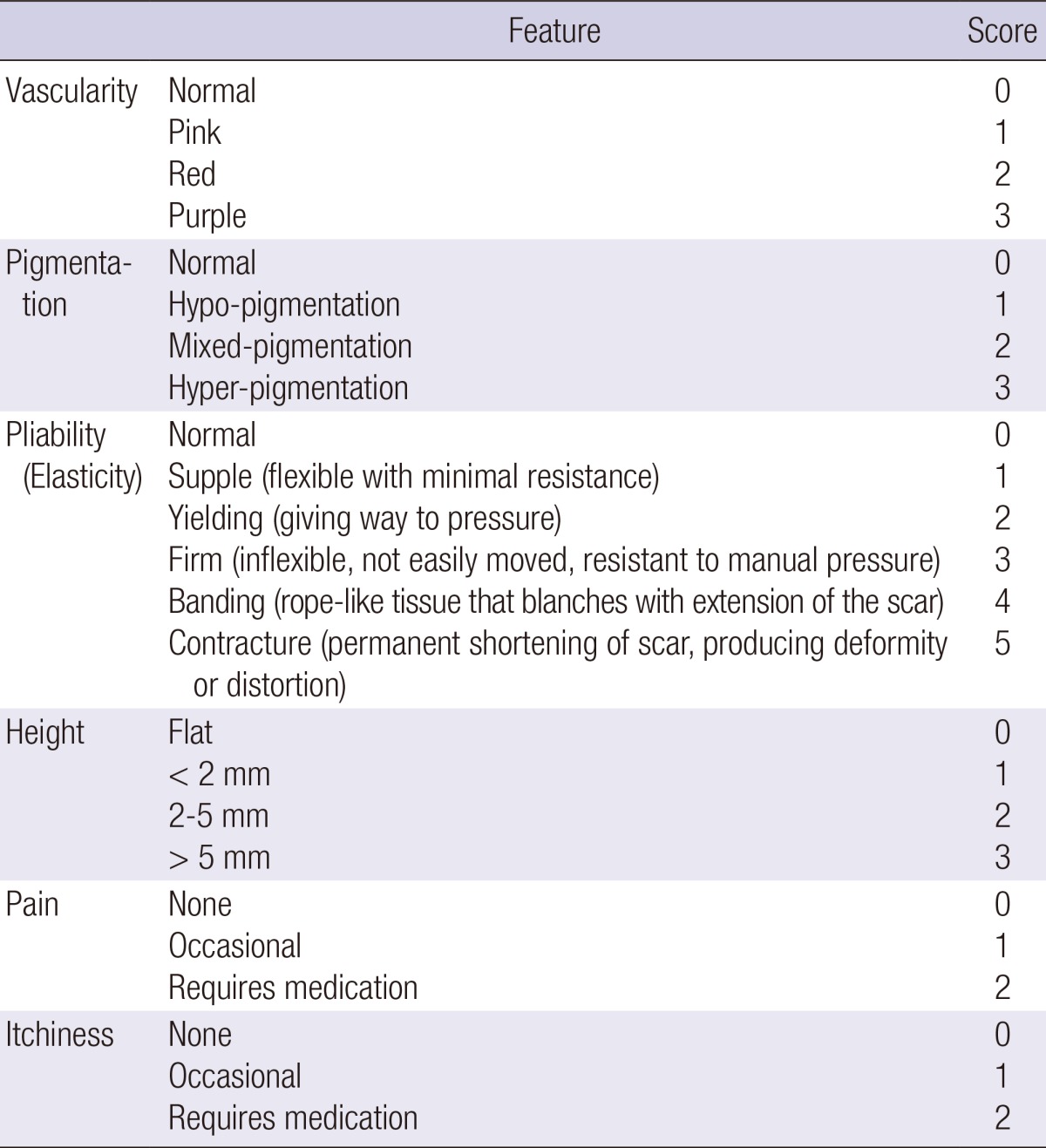

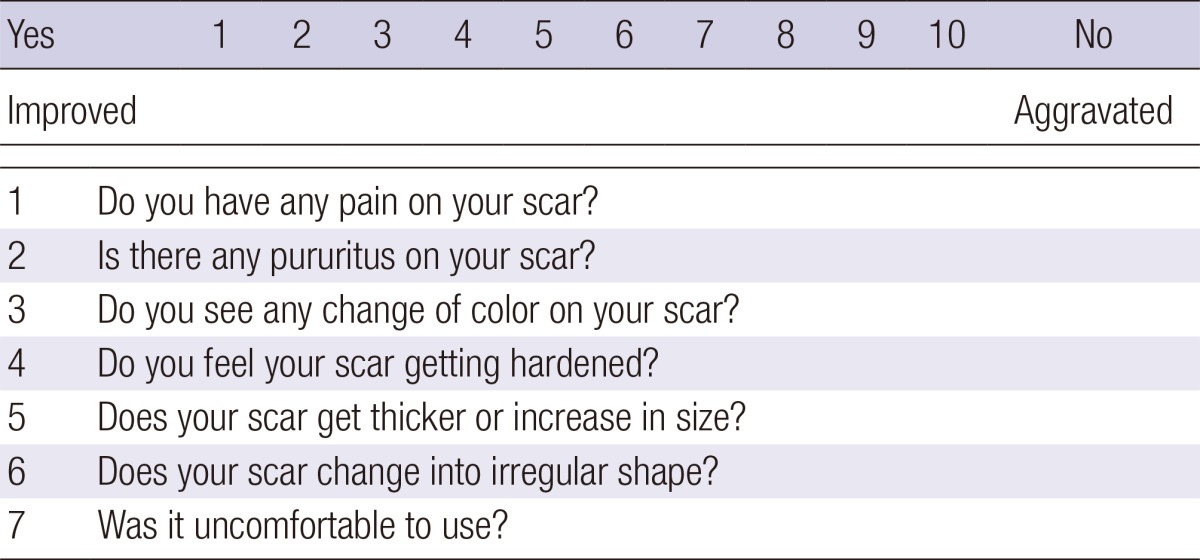

All patients were randomly assigned to and equally distributed between 2 treatment arms (treatment with either a silicone gel sheet [Scarclinic™-Thin, Hans Biomed, Seoul, Korea] or a topical silicone gel [Kelo-Cote™, SejongMedix, Seoul, Korea]). The arms were categorized as Group I (n=15) and II (n=15), respectively. First, patients' scars were photographed and evaluated using the Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS), for which their vascularity, pigmentation, pliability, height, pain, and itchiness were measured as outcomes (Table 1) (6, 9). The aforementioned evaluation was performed by 2 independent observers. We also recorded patients' questionnaire responses about any scar-related pain, pruritus, color change, hardness, thickness, overall size, irregularity, and inconvenience of use they experienced, and scored them using a 10-point scale (Table 2). Then, we evaluated the VSS scores and patient questionnaire scores at 1 and 3 months and compared them with the baseline measurements.

Table 1.

Vancouver Scar Scale

Table 2.

Patient questionnaire

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 16.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All data were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD). We used the Mann-Whitney test to compare outcome measures between the two groups. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of our medical institution (IRB approval number: HC11DSSI0091). All patients were informed of the study details (e.g., objectives, methods, predicted outcomes, adverse effects, and study devices), and submitted a signed informed consent document.

RESULTS

Baseline and clinical characteristics of the patients

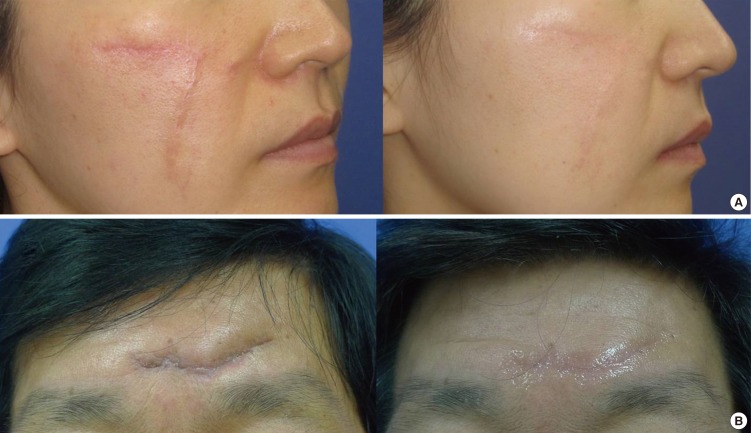

We enrolled 30 patients (n=30) in our study. Of these, 5 dropped out for personal reasons; therefore, 11 patients in Group I and 14 in Group II completed the study. These participants included 9 male and 16 female patients with a mean age of 37.52 yr (total range, 21-75 yr). When recording scar location, we observed 17, 7, and 1 patients with scars in the head and neck region, in the extremities, and in the trunk, respectively. All patients demonstrated tolerability for the treatment; none experienced specific clinical problems. By the conclusion of the study period, all patients' scars had improved in terms of pigmentation, height, irregularity, and overall size (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

(A) Before and after views of silicone gel sheet use in scar management. The scar has improved in its vascularity, irregularity, and height after 3 months of treatment. (B) Before and after views of topical silicone gel use in scar management. The scar has improved in its pigmentation, irregularity, and height after 3 months of treatment.

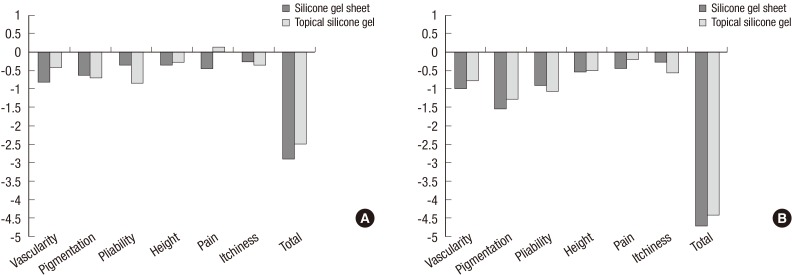

Changes from baseline in VSS scores at 1 and 3 months after treatment onset

At 1 month after treatment onset, we observed a degree of pain score change of -0.455 points in Group I and 0.143 points in Group II. This difference reached statistical significance (P=0.033). However, with the exception of the pain score, as shown in Fig. 2, no significant differences were observed between either group in either their VSS scores by outcome measure or their total scores at 1 and 3 months from baseline.

Fig. 2.

(A) Changes from the baseline in VSS scores at 1 month after treatment onset. (B) Changes from the baseline in VSS scores at 3 months after treatment onset. VSS, vancouver scar scale.

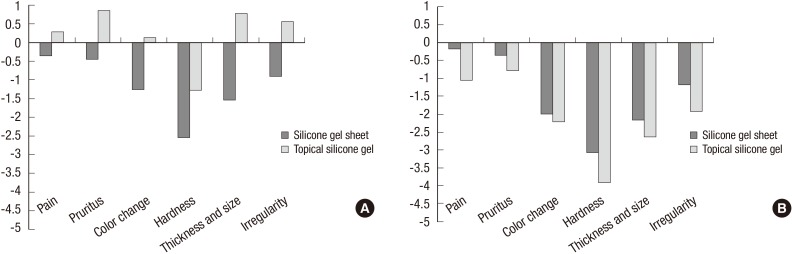

Changes from baseline in patient questionnaire response scoring at 1 and 3 months after treatment onset

At 3 months after treatment onset, questionnaire response scores for inconvenience of use were 3.818 points in Group I and 1.571 points in Group II. This difference also reached statistical significance (P=0.015). However, no significant differences between the groups were seen in any other outcome measures at 1 or 3 months from baseline (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

(A) Changes from the baseline in patient questionnaire response scores at 1 month after treatment onset. (B) Changes from the baseline in patient questionnaire response scores at 3 months after treatment onset.

DISCUSSION

Several treatment and prevention methods for surgical scarring are available today. These include intralesional corticosteroids; 5-fluorouracil; bleomycin; cryotherapy; silicone gel; pressure therapy; pulsed dye laser treatment; radiation; and surgical correction (10, 11, 12). Emerging scar-reducing therapies include the TGF-β superfamily; COX-2 inhibitors and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; collagen synthesis inhibitors; angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; minocycline; and gene therapy (11). Among these methods, silicone has typically been considered the standard noninvasive approach (13).

Since the early 1980s, silicone has been described as having potential effectiveness in treating pathological scars (14). Today, it is considered a conventional scar treatment approach (15, 16, 17). Indeed, a number of studies have assessed silicone's efficacy in preventing scar formation during the postoperative period (1, 2, 3, 4); it is frequently used after surgery because it is both non-invasive and causes few adverse effects (8, 16). However, a matter of controversy is whether silicone is truly effective in scar prevention (1, 18).

Various mechanisms have been proposed as possible modes of action for silicone materials. These hypotheses include increased temperature or oxygen tension, direct action of silicone oil, wound hydration, polarization of scar tissue caused by negative static charge and modulation of growth factors (7, 9, 10, 13). Silicone has been produced in several forms, including silicone cream compounds; silicone oil or gel, with additives such as Vitamin E; in combination with other dressing materials, and as custom-made silicone applications (18). Among these formats, silicone gel sheets are the most widely used; however, patients' compliance with silicone gel sheet use is not always satisfactory. The silicone gel sheets are inconvenient for patients to apply to large mobile areas, such as the area near the joints, and are generally not appropriate to use on visible areas like the face (3). Taping or bandaging is required to secure the silicone gel sheet to the scar, which may cause irritation in patients with pliable skin, particularly the elderly and the young (4). Moreover, silicone gel sheets may also cause excessive sweating in hot and humid climates (4). They must be washed carefully to prevent infections and other complications (3). All of the above factors often lead to interruption of gel sheet treatment. Topical silicone gels, by contrast, are available in a tube, and can be applied in a thin layer on the skin. They form a flexible, gas-permeable and invisible film on the scar (4); they may also be spread on the scar and will dry up within a period of several minutes, allowing patients to then wear clothes or apply makeup. In addition, topical silicone gels are advantageous in that they require no fixation materials. At the same time, these gels do pose disadvantages: they must be used in combination with sunscreen to prevent hyperpigmentation and must also be applied multiple times each day (8). Patients must also be sure that gel applied to parts of the body covered by clothing have dried completely before they get dressed; failure to do so may result in friction that removes the silicone film too early (4). Finally, these gels cannot be applied to the periocular or perioral area, particularly in younger patients.

Karagoz et al. (8) compared the efficacy of a topical silicone gel, a silicone gel sheet and a topical onion extract in treating postburn hypertrophic scars, and reported that the two silicone based-products were more effective than the onion extract. The authors also found no significant difference in the effectiveness of the two silicone-based products in treating hypertrophic scars. However, they did conclude that silicone gel sheets are the preferable method of treatment. This is not only because the degree of treatment response was relatively higher in the silicone gel sheet group but also because 1 patient in their study showed no response to the topical silicone gel. In addition, Mustoe et al. (15) also deemed silicone gel sheets worthy of consideration as a first-line of therapy for scar prevention.

It was the objective of our study to compare both efficacy and convenience of use in silicone gel sheets and topical silicone gels as surgical scar preventives. Between our two groups, we found no statistically significant differences in either VSS or questionnaire response scores at 1 or 3 months after treatment onset. The only significant difference observed was the degree of change in VSS pain scores at 1 month. While we assume the silicone gel sheet offers a greater degree of stability and protection in the early stages of scar formation, we could find no statistically significant difference in the degree of VSS pain score changes at 3 months after treatment onset. Meanwhile, the patient questionnaire inconvenience of use score was higher in our silicone gel sheet group at 3 months after treatment onset. This means that convenience of use proved greater in the topical silicone gel group. Our results prove that topical silicone gel is as effective as silicone gel sheet for preventing surgical scars and that it is also easier to use.

Our study did face several limitations. Although scar maturation can continue for up to a year after surgery, we followed scar progression for only 3 months. Previous studies that evaluated the efficacy of silicone gel in scar management also typically followed scar progression for a 2- to 4-month period (4, 19, 20, 21). We believe this is because many clinicians regard that the early stage of scar remodeling is the time of greatest change. An additional limitation was that our study population was small and consisted solely of Korean patients. Finally, when using the silicone gel sheet, patients who also used tape or bandaging to secure the sheet in arbitrary fashion may have influenced the pigmentation of their scars.

In conclusion, numerous silicone-based products are used in modern management of postoperative scars. Clinicians should select products for each patient while considering both their efficacy and convenience of use. Scar management is an ongoing process over a course of at least 3 to 6 months. It is therefore essential to ensure patient compliance throughout the treatment process. Consequently, clinicians must also carefully weigh the characteristics, lifestyle, and compliance likelihood of each patient, as well as the location of their scars, in choosing the appropriate management modality. In our study, we have demonstrated that there is no significant difference in the degree of efficacy between either silicone-based product types; at the same time, our results indicate that topical silicone gels are more convenient for patients to use than silicone gel sheets. While previous studies have advocated for silicone gel sheets as first-line therapies in postoperative scar management, we maintain that similar effects can be expected with topical silicone gel. Further long-term, large-scale, prospective controlled studies are likely warranted to confirm our findings.

Footnotes

There are no conflict of interest statements.

References

- 1.Ahn ST, Monafo WW, Mustoe TA. Topical silicone gel for the prevention and treatment of hypertrophic scar. Arch Surg. 1991;126:499–504. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1991.01410280103016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cruz-Korchin NI. Effectiveness of silicone sheets in the prevention of hypertrophic breast scars. Ann Plast Surg. 1996;37:345–348. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199610000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mustoe TA. Evolution of silicone therapy and mechanism of action in scar management. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2008;32:82–92. doi: 10.1007/s00266-007-9030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Signorini M, Clementoni MT. Clinical evaluation of a new self-drying silicone gel in the treatment of scars: a preliminary report. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2007;31:183–187. doi: 10.1007/s00266-005-0122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gimble J, Guilak F. Adipose-derived adult stem cells: isolation, characterization, and differentiation potential. Cytotherapy. 2003;5:362–369. doi: 10.1080/14653240310003026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bae SH, Bae YC. Analysis of frequency of use of different scar assessment scales based on the scar condition and treatment method. Arch Plast Surg. 2014;41:111–115. doi: 10.5999/aps.2014.41.2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ko WJ, Na YC, Suh BS, Kim HA, Heo WH, Choi GH, Lee SU. The effects of topical agent (kelo-cote or contractubex) massage on the thickness of post-burn scar tissue formed in rats. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40:697–704. doi: 10.5999/aps.2013.40.6.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karagoz H, Yuksel F, Ulkur E, Evinc R. Comparison of efficacy of silicone gel, silicone gel sheeting, and topical onion extract including heparin and allantoin for the treatment of postburn hypertrophic scars. Burns. 2009;35:1097–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2009.06.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Rocco G, Gentile A, Antonini A, Ceradini F, Wu JC, Capogrossi MC, Toietta G. Enhanced healing of diabetic wounds by topical administration of adipose tissue-derived stromal cells overexpressing stromal-derived factor-1: biodistribution and engraftment analysis by bioluminescent imaging. Stem Cells Int. 2010;2011:304562. doi: 10.4061/2011/304562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shih R, Waltzman J, Evans GR Plastic Surgery Educational Foundation Technology Assessment Committee. Review of over-the-counter topical scar treatment products. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:1091–1095. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000255814.75012.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reish RG, Eriksson E. Scars: a review of emerging and currently available therapies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:1068–1078. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318185d38f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stavrou D, Weissman O, Winkler E, Yankelson L, Millet E, Mushin OP, Liran A, Haik J. Silicone-based scar therapy: a review of the literature. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2010;34:646–651. doi: 10.1007/s00266-010-9496-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berman B, Perez OA, Konda S, Kohut BE, Viera MH, Delgado S, Zell D, Li Q. A review of the biologic effects, clinical efficacy, and safety of silicone elastomer sheeting for hypertrophic and keloid scar treatment and management. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1291–1302. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33280.x. discussion 1302-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perkins K, Davey RB, Wallis KA. Silicone gel: a new treatment for burn scars and contractures. Burns Incl Therm Inj. 1983;9:201–204. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(83)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mustoe TA, Cooter RD, Gold MH, Hobbs FD, Ramelet AA, Shakespeare PG, Stella M, Téot L, Wood FM, Ziegler UE, et al. International clinical recommendations on scar management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:560–571. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200208000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim SW, Kim DY, Oh DY, Lee JH, Rhie JW, Ahn ST, Yoon JH. Use of a silicone gel sheet vaginal mold in McIndoe vaginoplasty. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40:652–655. doi: 10.5999/aps.2013.40.5.652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martins-Mendes D, Monteiro-Soares M, Boyko EJ, Ribeiro M, Barata P, Lima J, Soares R. The independent contribution of diabetic foot ulcer on lower extremity amputation and mortality risk. J Diabetes Complications. 2014;28:632–638. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Brien L, Pandit A. Silicon gel sheeting for preventing and treating hypertrophic and keloid scars. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD003826. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003826.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan KY, Lau CL, Adeeb SM, Somasundaram S, Nasir-Zahari M. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, prospective clinical trial of silicone gel in prevention of hypertrophic scar development in median sternotomy wound. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1013–1020. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000178397.05852.ce. discussion 1021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chernoff WG, Cramer H, Su-Huang S. The efficacy of topical silicone gel elastomers in the treatment of hypertrophic scars, keloid scars, and post-laser exfoliation erythema. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2007;31:495–500. doi: 10.1007/s00266-006-0218-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murison M, James W. Preliminary evaluation of the efficacy of dermatix silicone gel in the reduction of scar elevation and pigmentation. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:437–439. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2005.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]