Abstract

Background

Congenital epulis is a rare lesion of the newborn, presenting as mass in the oral cavity which can interfere with respiration and feeding. It should be distinguished from other lesions which can occur in newborns, both clinically and histopathologically.

Case Details

Here, we report a case of congenital epulis in a newborn female on the right alveolar ridge, along with an extensive review of literature and discuss the immunoprofiling.

Conclusion

Early diagnosis of CE in a newborn is of paramount importance in the successful management of these rare cases.

Keywords: congenital epulis, congenital granular cell lesion, Neumann's tumor

Introduction

Congenital gingival granular cell tumor (CGCT) of the newborn, also known as congenital granular cell lesion, congenital epulis, congenital myoblastoma (historically), or Neumann's tumor, is a rare non-neoplastic lesion seen only in newborns (1). It presents in the mouth most commonly in the maxillary alveolar ridge as a smooth-surfaced sessile or pedunculated mass with normal to reddish colour mucosa. It varies in size from several millimeters to few centimeters in diameter and can interfere with respiration or feeding. In recent years, prenatal detection of such oral lesions has facilitated the narrowing down of differential diagnosis and proper treatment planning through multidisciplinary approach. Although, histopathologically this lesion shows similarity with granular cell tumour which occurs in adults, the two are separate entities with different histogenesis. We report a rare case of congenital epulis with an extensive review of literature.

Case Report

A newborn female child was referred to our institute, immediately after delivery for examination of a mass protruding from her mouth. The child weighed 3.25 kg at birth. Pregnancy was normal and vaginal delivery occurred at 37th week. No abnormalities had been diagnosed in ultrasound performed in the 29th week of gestation. No family history of hereditary diseases was reported.

On clinical examination, a round, soft pedunculated mass of 4cm diameter, exhibiting a smooth erythematous surface was located on the right side of the maxillary alveolar ridge (Fig 1). The mass prevented normal closure of the mouth and interfered with breastfeeding, but did not pose an immediate airway concern. General physical examinations, including laboratory tests, were normal.

Fig. 1.

Lesion Attached to maxillary alveolar ridge protruding from the mouth

On the second day after birth, the tumor was completely resected by surgical excision following anaesthesia, and subjected to histopathological examination. The intraoperative and postoperative courses were uneventful. The newborn recovered with no complications, and breastfeeding was initiated on the subsequent day of operation.

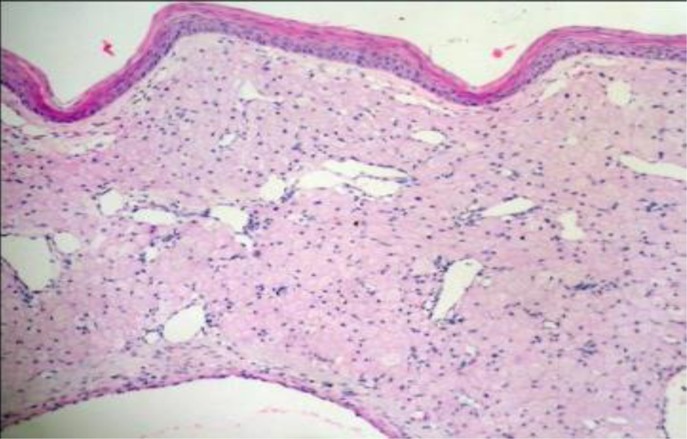

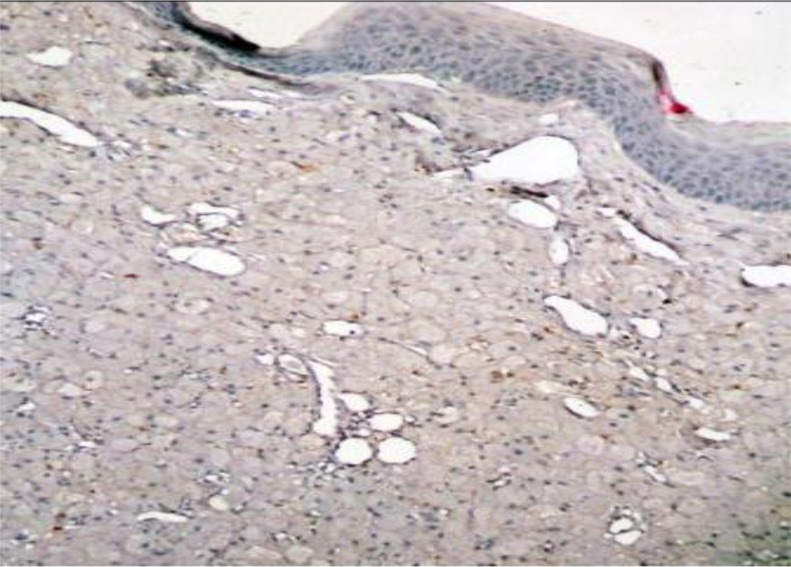

The gross specimen measured 3.5cm × 3.5cm × 2cm and was pink in color with a smooth surface and firm consistency. The cut surface was grayish-white and the lesion appeared well circumscribed. This tissue was processed for routine histopathological examination and embedded in paraffin.4 µm-thick sections were cut from these paraffin-embedded tissue blocks and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Sections revealed lesional tissue comprising large sheets of polygonal or rounded cells with a centrally placed small dark basophilic nucleus with an abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm, abutting the overlying parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelium. Lesional tissue showed a high degree of vascularity (Fig 2). The tissue was non-reactive to S-100 protein and CD68 (Fig 3); but reactive to vimentin. These findings were consistent with the diagnosis of congenital granular cell epulis.

Fig 2.

H&E stained sections showing stratified squamous epithelium and underlying tissue with granular cytoplasm

Fig. 3.

Immunostaining showing negative staining for CD68

Discussion

Congenital epulis (CE) has many synonyms. Congenital epulis of the new born is a widely accepted term and few prefer it over congenital granular cell tumor, which is suggestive of a neoplasm (4). However, epulis is a non-specific term used to designate hyperplastic gingival tissue or gingival tumor masses. Since there are cases which are not exclusively related to the gingiva, (1,3) seems that the term congenital granular cell lesion would be a more appropriate term (5).Since its first description in 1871in Germany as “congenital epulis” by Neumann (6), over 200 cases of this rare lesion have been reported (2).

CE is usually seen at birth and has a site predilection for the maxillary alveolar process, lateral to the midline in the region of the primary canine and lateral incisor. Less frequently, it has been reported in the mandibular alveolus, tongue and one case with involvement of alveolar ridge as well as the tongue (6).

CE usually occurs as a solitary lesion, although in 10% of the cases, it occurs as multiple masses (4,7). It presents as a mass with a smooth normal colored surface, pedunculated, sometimes lobulated, and varying in size from a few millimeters to 9 cm (8). It occurs more in often in females than males (9).

CE is usually diagnosed at birth; although, if the lesion is large, it may be diagnosed in utero by 3D ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examinations. In utero diagnosis is important in choosing the delivery method, since large lesions may compromise a normal vaginal delivery and a cesarean operation may be necessary (8). Although there are studies that affirm successful prenatal diagnosis of CE, these studies actually obtained images of the tumor mass, but the diagnosis could not be conclusive (5). A list of differential diagnosis thus obtained is valuable in treatment planning and a multidisciplinary approach during delivery.

Etiology of CE remains uncertain. The tumor is also postulated to originate from undifferentiated mesenchymal cells, fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, histiocytes, pericytes, Schwann cells or odontogenic epithelial cells. Few immunohistochemical study findings support a mesenchymal origin (3, 5, 10).Ultrastructural studies showed presence of many autophagosomes containing collagen precursors, suggesting the tumor cells represent early mesodermal cells that express pericytic and myofibroblastic features that undergo cytoplasmic autophagocytosis (11).

There are usually no associated dental abnormalities or congenital malformations (2), except for occasional reports of a hypoplastic or absent tooth and the possibility of mild midface hypoplasia (2,4). CE has been reported in infants with polydactyly, goiter, Triple × syndrome, maxillary hypoplasia, neurofibromatosis and polyhydraminos (2,12).

Clinical differential diagnoses for congenital lesions of oral mucosa depend on site of involvement, size, velocity of growth, and possible accompanying lesions. This includes teratoma (epignathus)(13), hemangioma, fibroma, choristoma and hamartoma, melanotic neuroectodermal tumour of infancy, rhabdomyoma, rhabdomyoscarcoma, lymphangioma, osteogenic and chondrogenic sarcomas, and granular cell tumor (3,12,13). However, some congenital lesions occur predominantly on the alveolar ridge and others on tongue, thus narrowing the list of possible differentials in a particular site. Leiomyomatous hamartoma has the appearance of congenital epulis and is often seen on the median anterior alveolar ridge and the tip of the tongue (1).

Histologically, CE bears a very close resemblance to granular cell tumor. Both the lesions show abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm. They are two different entities which may be differentiated on histological and epidemiological grounds (14). Granular cell tumor is more commonly seen, with few reported cases of malignant transformation, whereas CE is a rare lesion with an incidence of 0.0006% (9) and no evidence of malignant transformation. CE occurs in neonates predominantly in females on the right side of the maxillary alveolar ridge, whereas, granular cell tumor occurs in adults on the tongue and a wide variety of visceral and cutaneous sites (orbit, lung, mastoid, tongue, infra and supraglottic regions), with no sex predilection. Granular cell tumour may show pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia often with squamous pearl formation in the epithelium and is less vascular with prominent nerve bundles. Ultrastructurally, in CE, membrane bound granules or phagolysosomes are present in the cytoplasm, many of which contain collagen precursors, but angulate bodies are absent unlike in granular cell tumor (11). Immunohistochemical study shows no reactivity of lesional cells to S-100 protien, NGFR/p75, and inhibin-alpha in CE but both CE and granular cell tumor have stained positive for macrophage markers like CD68 and Ki-M1P. However, the statement is equivocal and few cases have demonstrated no reactivity to CD 68 (15). In line with these cases, our case also did not show any staining to CD68. CE also shows positive immunohistochemical staining to HLA-DR antigen, vimentin, NKI/C3, and PGP9 and occasionally NSE and CEA(3,16,17,18). Although immunohistochemical profiling has not confirmed the cells of origin of this lesion, it has proved useful in confirming that CE is non-neoplastic and aids in differentiating it from granular cell tumor histologically (19).

The treatment of choice is surgical excision, when the lesion is obstructing feeding or respiration. It can be excised either under general anesthesia within hours to days after birth or local anesthesia where intubation is not possible or in cases of small lesions (2). There is also the possibility of removal during the delivery, in cases where the lesion was detected during pregnancy (20). This approach provides the newborn a free airway and an unobstructed oral cavity immediately after birth eliminating additional procedures such as anesthesia and intubation. Surgical excision of CE using carbon dioxide laser and erbium, chromium: yetrium-scandium-galliumgarnet (Er, Cr: YSGG) laser have also been reported. There have been eight case reports that have documented spontaneous regression. In cases where there is no interference with feeding or respiration, regular monitoring of the lesion for regression has been advocated as an acceptable clinical approach. In our case, the lesion interfered with feeding and was thus excised at the earliest so to avoid any further dehydration in the newborn. CE has not recurred even after incomplete excision, and has no tendency for malignant transformation.

References

- 1.Kayiran SM, Buyukunal C, Ince U, Gürakan B. Congenital epulis of the tongue: A case report and review of the literature. J R Soc Med Sh Rep. 2011;2:62. doi: 10.1258/shorts.2011.011048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ritwik P, Brannon RB, Musselman RJ. Spontaneous regression of congenital epulis: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports. 2010;4:331. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-4-331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fister P, Volavsek M, Novosel Sever M, Jazbec J. A newborn baby with a tumor protrudingfrom the mouth. Acta Dermatoven APA. 2007;16:128–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sahu S, Maurya RK, Rao Y, Agarwal A. Multiple congenital epulis in newborn: a rare presentation. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2009;13:78–80. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.57674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silva GCC, Vieira TC, Vieira JC, Martins CR, Silva EC. Congenital granular cell tumor (congenital epulis): A lesion of multidisciplinary interest. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2007;12(6):E428–E430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasanov A, Musayev J, Onal B, Rahımov C, Farzaliyev I. Gingival granular cell tumor of the newborn: a case report and review of literature. Turk Patoloji Derg. 2011;27(2):161–163. doi: 10.5146/tjpath.2011.01067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feller L, Wood NH, Singh AS, Raubenheimer EJ, Meyerov R, Lemmer J. Multiple congenital oral granular cell tumours in a newborn black female: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:13. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wittebole A, Bayet B, Veyckemans F, Gosseye S, Vanwijck R. Congenital epulis of the newborn. Acta Chir Belg. 2003;103:235–237. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2003.11679415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosanquet D, Roblin G. Congenital Epulis: A Case Report and Estimation of Incidence. Int J Otolaryngol. 2009;2009:508780. doi: 10.1155/2009/508780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lapid O, Shaco-Levy R, Krieger Y, Kachko L, Sagi A. Congenital epulis. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E22. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.2.e22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Damm DD, Cibull ML, Geissler RH, Neville BW, Bowden CM, Lehmann JE. Investigation into the histogenesis of congenital epulis of the newborn. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;76(2):205–212. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(93)90206-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gokhale UA, Malhotra CJ. Congenital epulis of the newborn. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52(3):436–437. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.55020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szlachetka K, Bern EML, Ozcan T. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31:123–129. doi: 10.7863/jum.2012.31.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vered M, Dobriyan A, Buchner A. Congenital granular cell epulis presents an immunohistochemical profile that distinguishes it from the granular cell tumor of the adult. Virchows Arch. 2009;454(3):303–310. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0733-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Childers ELB, Smith J CF. Congenital epulis of the newborn: 10 new cases of a rare oral tumor. Ann Diag Path. 2011;15(3):157–161. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koch BL, Myer C, 3rd, Egelhoff JC. Congenital epulis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:739–741. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adeyemi BF, Oluwasola AO, Adisa AO. Congenital epulis. Indian J Dent Res. 2010;21(2):292–294. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.66638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dhingra M, Pantola C, Agarwal A. Congenital granular cell tumor of the alveolar ridge. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53(2):327–328. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.64315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uğraş S, Demírtaş I, Bekerecíoğlu M, Kutluhan A, Karakök M, Peker O. Immunohistochemical study on histogenesis of congenital epulis and review of the literature. Pathol Int. 1997;47(9):627–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1997.tb04553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson PJ, Kirkland P, Schafler K, Moss ALH. Congenital gingival granular cell tumour. J R Soc Aed. 1996;89:53P–54P. doi: 10.1177/014107689608900116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]