Abstract

Objective

To examine the effect of early clinical and demographic factors on occupational outcome, return to work or awarded permanent disability pension in young patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS).

Design

Longitudinal cohort study.

Intervention

A written self-management programme including a description of active coping strategies for daily life was provided.

Setting, participants

Patients with CFS after mononucleosis were evaluated at Department of Neurology, Haukeland University Hospital during 1996–2006 (contact 1). In 2009 self-report questionnaires were sent to all patients (contact 2).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Primary measure was employment status at contact 2. Secondary measures included clinical symptoms, and Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) scores on both contacts, and Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) at contact 2.

Results

Of 111 patients at contact 1, 92 (83%) patients returned the questionnaire at contact 2. Mean disease duration at contact 1 was 4.7 years and at contact 2 11.4 years. At contact 1, 9 (10%) were part-time or full-time employed. At contact 2, 49 (55%) were part-time or full-time employed. Logical regression analysis showed that FSS≥5 at contact 2 was associated with depression, arthralgia and long disease duration (all at contact 1).

Conclusions

About half of younger patients with CFS with long-term incapacity for work experienced marked improvement including full-time or part-time employment showing better outcomes than expected. Risk factors for transition to permanent disability were depression, arthralgia and disease duration.

Keywords: OCCUPATIONAL & INDUSTRIAL MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Two strengths of the study are very long prospective follow-up period and focus on employment.

A limitation is that patients were recruited from a tertiary centre.

Long-term prognosis for young patients with chronic fatigue syndrome after mononucleosis is favourable for a large subgroup.

More than half of the patients with long-term incapacity for work are re-employed after mean disease duration of 11.4 years.

Factors associated with poor long-term prognosis include depression, arthralgia and disease duration.

Introduction

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is a complex incapacitating illness of unknown cause.1 2 CFS is characterised by persistent/recurrent post-exertional fatigue of at least 6 months’ duration accompanied by at least four of eight specific symptoms including impaired short-term memory or concentration, severe enough to cause substantial reduction in previous levels of occupational, educational, social or personal activities; headache of a new type, pattern or severity; muscle pain; multijoint pain without swelling or redness; sore throat; tender cervical or axillary lymph nodes; unrefreshing sleep; post-exertional malaise (PEM), an exaggerated fatigue response to previous well tolerated activities.1 3 The clinical condition has received increased attention in the past two decades from medical, psychological and social security/insurance communities. The term ‘Chronic Fatigue Syndrome’ was coined in 1988 by the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the present case definition was developed by a joint CDC/National Institute of Health (NIH) international working group.1 The excessive fatigue and fatigue-ability with disproportionately prolonged recovery after exercise or activity differentiate CFS from other fatigue conditions.

Recent population-based epidemiological studies using the 1994 CDC case definition have reported the overall CFS prevalence to be 71 and 190 per 100 000 persons, respectively, in Olmsted County, Minnesota and three regions of England.4 5 CFS occurs in individuals during peak years of employment (age 20–50) with female preponderance. Rates of unemployment are high.6 Work-related physical and cognitive impairments are demonstrable with prolongation and recurrence of sickness absence episodes that can be the first step in a process leading to prolonged medical leave and awarded disability benefits.7

A small proportion of people that develop infectious mononucleosis remain sick with CFS.8 A recent follow-up study of the course and outcome of CFS in adolescents after mononucleosis showed that most individuals recover; however 13 of 301 adolescents, 4%, all female, met the criteria of CFS after 2 years.9

Knowledge about the natural history and prognostic factors in CFS is important as it relates to several aspects of the illness; information and advice to newly diagnosed patients, planning of healthcare and rehabilitation strategies that focus on volitional and social aspects of re-employment.10 Being unable to fulfil valued and expected social functions, including employment, can have a dramatic impact on self-concept with need to re-evaluate life goals, as well as increased stress on the part of caregivers.11

Few patient-based longitudinal studies have examined employment outcomes as measure of prognosis in the case of CFS.12 13 The objectives of this two time point study of a cohort of younger patients with CFS without systematic intervention were to document the natural course of illness and to identify predictors of work cessation or re-entry into work force. Only patients with CFS subsequent to mononucleosis were included in this study.

We hypothesised that baseline clinical presentations such as cognitive problems, pain and depression at the time of referral in addition to severe fatigue and long illness duration prior to the evaluation predict long-term functional disability including unemployment and awarded disability benefits.

Material and methods

Patients

The 111 young patients, mean age 23 year, participating in this study were part of a larger cohort of 873 consecutive patients referred from all over Norway to a specialist chronic fatigue clinic at the Department of Neurology, Haukeland University Hospital during 1996–2006, published previously.14 All patients were interviewed and examined by a specialist physician, HIN, who confirmed the diagnosis of CSF meeting the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) case definition.1 The 111 patients constitute all patients diagnosed with CSF triggered by mononucleosis in the total cohort of 873 patients. The diagnosis of mononucleosis was based on the physician report following the patient to our clinic.

A written self-management programme included information about the illness to provide the patients with a rationale and structural meaning for their illness experience.15 Active coping strategies for daily life included graded activity planning; encouraging activity, but staying within their physical limitations with consistent rest periods to minimise fluctuations in fatigue and symptoms. To avoid occupational impairment and restore ability to work the importance to keep contact with the local health and rehabilitation services, and inform the employer was stressed. The family doctor and the local National Sickness Benefit Scheme office (NAV) received a specialist report on the medical history and investigations, the clinical characteristics and disability.16

The Norwegian Social and Insurance Scheme accepted CFS as a medicolegal diagnosis entitled to sickness and disability benefits to compensate for income loss in 1995.17 To receive long-term sickness absence (SA) benefits a sickness certificate has to be issued by a physician describing the cause of absence and plans for treatment. A disability pension (DP) is given to individuals aged 18–66 to compensate for permanent work-life exit before scheduled age retirement after relevant treatment or vocational rehabilitation.18

Primary outcome measures at long-term follow-up were employment: return to part-time or full-time work, or transition to ill-health retirement and receipt of permanent disability pension. Secondary outcomes were self-rated scales of clinical change, fatigue, disability and CFS somatic symptoms.

Contact 1. Initial baseline evaluation

All patients completed a questionnaire at referral that included questions about the mode of clinical onset (whether the fatigue appeared acutely or evolved gradually over months) and duration of the illness. Questions about presenting symptoms comprised the presence or not of concentration or memory problems, throat pain, enlarged or tender lymph nodes, myalgia, muscle weakness, arthralgia, dyspepsia, weight change, frequent micturition, photophobia, slurred vision, dizziness, tinnitus, sleep disturbances, depression, unstable mood, palpitations, fever, increased sweating and headache. PEM19 was assessed with the following question: does physical activity influence fatigue; improving, no effect, some worsening, much worsening?

Fatigue was self-rated by the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS).20 This is a nine-item questionnaire that assesses the effect of fatigue on daily living. Each item is a statement on fatigue that the participant rates from 1, ‘completely disagree’ to 7, ‘completely agree’. Examples of the items in the questionnaire are: ‘My motivation is lower when I am fatigued’, ‘Exercise brings on my fatigue’ and ‘I am easily fatigued’. The average score of the nine items represents the FSS score (minimum score is 1 and maximum score is 7). Patients with a mean FSS score >5 are defined as having severe fatigue.21

Employment status was noted as employed full-time, part-time or unemployed. Sick leave from work or study, long-term SA benefits and DP were registered. Employment or studies at the time of the triggering mononucleosis were registered.

Contact 2. Follow-up during 2009

Self-report questionnaires were sent to the patients in 2009 on average 6.5 years after contact 1. A clinical symptom questionnaire included questions as to presence or not of problems with concentration and memory, throat pain, enlarged or tender lymph nodes, myalgia, muscle weakness, arthralgia, dyspepsia, nausea, weight change, frequent micturition, photophobia, slurred vision, dizziness, tinnitus, sleep disturbances, depression, unstable mood, palpitations, fever, increased sweating and headache.

The Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) was used to measure disability. It is a five-item scale that assesses an individual`s ability to perform everyday activities including work, home management, family and relationship interaction and social and private leisure activities. Each of the five items was rated on a nine-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all a problem) to 8 (severely impaired) so that the total scores range between 0 and 40.22 The psychometric properties have been validated in large patient with CFS cohorts confirming that WSAS is a reliable assessment tool for disability. High scores correlate with severe fatigue and poor physical fitness.16

Fatigue was self-rated by the FSS scale. Based on change in FSS score change from baseline, contact 1, the disease course was defined; FSS change <−1 was defined as worsening course; FSS change ≥−1 and ≤1 was defined as no change; FSS change >1 was defined as improvement. Self-rated global clinical outcome was scored as worsening, stable, improvement and recovered. Employment status, sickness and disability benefits were recorded providing objective evidence of disability.

The study was approved by the local ethics committee. Informed, written consent was obtained from the patients.

Statistics

Student's t test, χ2 test, Fisher's exact test, and pair-wise correlation test were performed when appropriate. The FSS score was dichotomised and FSS score ≥5 defined as pathological fatigue. Stepwise backward logistic regression analyses were performed with dichotomised FSS score at contact 2 as dependent variable. Stepwise backward linear regression analyses with FSS at contact 2 and WSAS as dependent variables were performed. STATA V.12.0 was used for analyses.

Results

In total, 111 patients participated in the baseline evaluation. Postal questionnaires were completed and returned by 92 (83%) of these patients on follow-up (contact 2); 30 (33%) males and 62 (67%) females (contact 2). The mean age of the patients at the onset of CFS was 23.7 years (SD=7.3). Mean duration of CFS at the time of contact 1 was 4.7 years (SD=4.0), (median=3.2 years, IQR=1.9−6.4). Mean time from debut of CFS to contact 2 was 11.4 years (SD=4.3; median=10.3 years, IQR=8.5–13.5; range=4.7−23.8). At the time of mononucleosis 43 (47%) were employed at work and 48 (52%) were students (missing data in one patient). We do not report any data on the 19 (17%) who did not complete the follow-up.

Employment at contact 1(92 patients)

At contact 1 9 (10.2%) patients remained employed (1 full-time and 8 part-time), 12 patients (13.5%) were students and 70 patients (81%) were neither employed nor studying (missing data in one patient). One patient (1%) was receiving partial DP and 7 patients (8%) were receiving full DP. Fourteen (15%) patients received partial long-term SA benefits, and 62 (67%) patients received full long-term sickness SA (missing data in 8 patients).

Employment at contact 2 (primary measures; 92 patients)

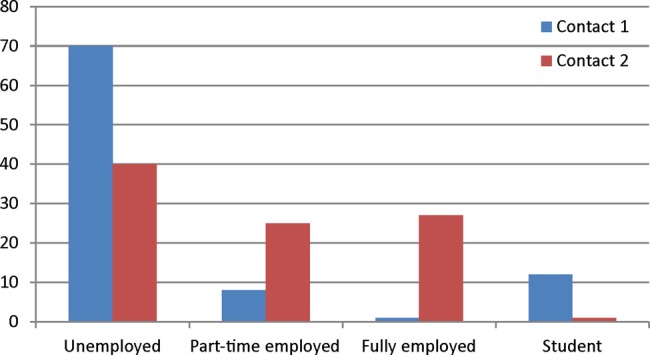

At contact 2 24 (27%) were fully employed, 25 (28%) were employed part-time and 40 (45%) were unemployed (missing data in three patients). One patient (1%) was a student. In total, 63 of 92 patients received DP or sickness absence benefits: 15 patients (17%) were awarded partial DP and 39 (44%) received full DP for the reduced working capacity, 6 patients (7%) got partial SA benefits and 3 patients (3%) full SA benefits. One (1%) unemployed patient was part-time student. Five (5%) patients were employed at both contact 1 and contact 2. Figure 1 shows employment status at contact 1 and contact 2.

Figure 1.

Employment status of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome at first contact (contact 1) and follow-up (contact 2).

Logistic regression analyses showed that being employed at contact 2 was associated with lack of arthralgia (OR=0.3, p=0.028) and reporting improvement (OR=1.8, p=0.062) at contact 1. Another logistic regression analyses showed that being employed at contact 2 was associated with low FSS score at contact 2 (OR=0.53, p<0.001), lack of arthralgia (OR=0.40, p=0.041) and lack of concentration problems (OR=0.32, p=0.064), but none of the other symptoms reported at contact 2.

Secondary measures

There was no correlation between FSS score at contact 2 and degree of PEM at contact 1 (p=0.57). There was no correlation between mode of onset of fatigue after mononucleosis (acute or taking months) and FSS score at contact 2 (p=0.61). Neither was there any correlation between employment status at contact 2 and degree of PEM at contact 1 (p=0.91) nor mode of onset (P=0.59). There was no correlation between degree of PEM at contact 1 and FSS score at contact 1 (p=0.99).

Based on FSS change from contact 1 to contact 2, 38 (44%; FSS improvement>1) improved, 42 (48%; FSS change ≤1 and ≥−1) did not change and 7 (8%) worsened (FSS change <−1). Based on self-assessment 10 (12%) had worsened, 14 (17%) were stable, 47 (57%) had improved and 11 (13%) had recovered at contact 2.

The correlation between self-rated clinical change between contact 1 and contact 2 and employment status at contact 2 was r=0.54 (p<0.001). The correlation between change in FSS from contact 1 to contact 2 and employment status was r=0.30 (p=0.01). The correlation between FSS score at contact 2 and employment was r=0.51 (p<0.001). The correlation between WSAS score and employment was r=0.74 (p<0.001). The correlation between WSAS score and FSS score at contact 2 was r=0.81 (p<0.001).

Clinical characteristics based on evaluation at contact 1 and contact 2 are shown in table 1. Mean FSS score dropped from 6.4 to 5.0 (p<0.001). CFS symptom pattern showed significant less frequencies of concentration and memory problems, headache, myalgia, sleep disturbances at contact 2 compared to contact 1 (all p<0.005), but no changes as to depression and arthralgia. A comparison between patients with FSS ≥5 versus FSS<5 at contact 2 is shown in tables 2 and 3.

Table 1.

Symptoms on contact 1 and contact 2

| Contact 1 | Contact 2 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FSS score, mean (SD) | 6.4 (0.96) | 5.0 (1.9) | <0.001 |

| Headache | 61 (71) | 47 (52) | 0.033 |

| Myalgia | 65 (72) | 52 (58) | 0.042 |

| Arthralgia | 43 (48) | 38 (42) | 0.45 |

| Sleep disturbances | 60 (66) | 47 (52) | 0.048 |

| Depression | 30 (33) | 25 (28) | 0.42 |

| Concentration problems | 83 (92) | 58 (64) | <0.001 |

| Memory problems | 72 (79) | 51 (56) | <0.001 |

| Sore throat | 48 (53) | 34 (37) | 0.008 |

| Tender cervical lymph nodes | 17 (19) | 30 (33) | 0.36 |

FSS, Fatigue Severity Score.

Table 2.

FSS score >5 or <5 on second follow-up (contact 2) and symptoms at contact 1

| Number of patients | FSS <5 | FSS >5 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | 30 | 9 (25) | 21 (39) | 0.17 |

| Females | 60 | 27 (75) | 33 (61) | |

| Age debut of CFS | 23.8 (7.9) | 24.1 (7.0) | 0.85 | |

| Age (second control) | 33.6 (7.9) | 35.8 (6.9) | 0.17 | |

| First control (contact 1) | ||||

| Age (first control) | 26.8 (7.5) | 29.3 (7.0) | 0.11 | |

| FSS score (mean) | 6.3 (1.2) | 6.4 (.8) | 0.63 | |

| Duration of CFS (years sum, mean) | 3.3 (2.4) | 5.6 (4.5) | 0.006 | |

| Arthralgia | 89 | 11 (33) | 32 (59) | 0.010 |

| Myalgia | 89 | 24 (69) | 40 (74) | 0.57 |

| Headache | 89 | 25 (71) | 38 (70) | 0.92 |

| Sleeping disturbances | 90 | 23 (64) | 36 (67) | 0.79 |

| Depression | 89 | 8 (23) | 22 (41) | 0.081 |

| Concentration problems | 89 | 32 (91) | 50 (93) | 0.84 |

| Memory problems | 90 | 30 (83) | 41 (76) | 0.40 |

| Sore throat | 90 | 22 (61) | 26 (48) | 0.23 |

| Tender cervical lymph nodes | 90 | 13 (36) | 19 (35) | 0.93 |

| Physical activity: effect on fatigue | 70 | 0.94 | ||

| None | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | ||

| Worse | 11 (38) | 14 (35) | ||

| Much worse | 17 (59) | 25 (63) | ||

| Clinical change prior to first control | 71 | 0.06 | ||

| Improvement | 16 (55) | 12 (29) | ||

| No change | 4 (14) | 13 (31) | ||

| Worsening | 9 (31) | 17 (40) | ||

| Education | 89 | 0.08 | ||

| Primary school | 2 (6) | 7 (13) | ||

| High school | 6 (17) | 17 (32) | ||

| College or university | 28 (78) | 29 (55) |

CFS, chronic fatigue syndrome; FSS, Fatigue Severity Scale.

Table 3.

FSS score >5 or <5 on second follow-up and symptoms at contact 2

| Number of patients | FSS<5 | FSS>5 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (second control) | 92 | 33.6 (7.9) | 35.8 (6.9) | 0.17 |

| Duration of CFS (years, mean) | 90 | 10.1 (3.1) | 12.1 (4.7) | 0.028 |

| Arthralgia | 90 | 7 (19) | 31 (57) | <0.001 |

| Myalgia | 90 | 11 (31) | 41 (76) | <0.001 |

| Headache | 90 | 11 (31) | 35 (65) | 0.001 |

| Sleeping disturbances | 90 | 9 (25) | 37 (69) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 90 | 4 (11) | 20 (37) | 0.006 |

| Concentration problems | 90 | 14 (39) | 43 (80) | <0.001 |

| Memory problems | 90 | 12 (33) | 38 (70) | 0.001 |

| Sore throat | 90 | 12 (33) | 22 (41) | 0.48 |

| Tender cervical lymph nodes | 90 | 6 (17) | 24 (44) | 0.006 |

CFS, chronic fatigue syndrome; FSS, Fatigue Severity Scale.

Among 26 patients who reported improvement prior to contact 1, 25 (96%) reported further improvement at contact 2, whereas among 38 patients who reported worsening or no change at contact 1, 23 (61%) reported improvement at contact 2 (p=0.001).

Logistic regression showed that FSS≥5 (versus FSS<5) at contact 2 was associated with the following variables registered at contact 1: arthralgia (OR=3.1, p=0.026), depression (OR=4.0, p=0.029), duration of disease (OR=1.2, p=0.043), and male sex (OR=2.6, p=0.087). Linear regression analysis with FSS score at contact 2 as dependent variable showed that arthralgia, depression (both at contact 1) and level of education accounted for 22% of the variation of the FSS score (R2=0.22).

Disability was evaluated according to the WSAS, and table 4 shows linear regression with WSAS score as dependent variable and variables registered at contact 1. WSAS score was significantly associated with depression, arthralgia, clinical change, PEM and level of education (R2=0.28).

Table 4.

Linear regression with WSAS as dependent variable and variables registered at contact 1

| β | p Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | <0.001 | 1.0 |

| Age | 0.16 | 0.17 |

| Depression | 0.27 | 0.026 |

| Arthralgia | 0.25 | 0.041 |

| Clinical change | −0.26 | 0.031 |

| PEM | −0.28 | 0.025 |

| Education | −0.27 | 0.021 |

PEM, post-exertional malaise; WSAS, Work and Social Adjustment Scale.

Discussion

Our main finding was that about half of the patients improved during the study period and were fully or partly employed at the final follow-up. This shows that the occupational outcome is favourable in a considerable fraction of younger patients with CFS after on average 5 years sickness absence from work. However, the transition to partly (15 patients) or full (39 patients) permanent disability pension shows that a substantial proportion develop chronic incapacity for work with severe negative consequences both for the individual and for the wider society and economy.

Few studies have examined employment status over time using operational criteria for CFS and standardised measurements of disability and functioning to provide information about the numbers of patients who were functionally impaired and unable to work.13 To our knowledge this study is the longest follow-up study of CFS that has been published. Table 5 describes six studies that examined work status over time. A long-term follow-up study included 33 patients, mean age 43 years, who answered identical questionnaires at diagnosis, after 4 years illness duration, and 5 years later. Work disability was very high at baseline (77%) and increased to 91% at 5-year follow-up.23 A prospective study including 246 patients found little improvement in occupational status after a follow-up period of 18 months. Before onset of symptoms 141 (57%) patients worked. At initial assessment 69 (28%) worked and 105 (43%) were on sick leave or receiving disability benefits. At follow-up 71 patients (29%) worked and 103 (42%) were on sick leave. Self-reported improvement was indicated by 50 patients (20%), and 49 (20%) reported worsening of symptoms.24 Another study reported the outcome for 35 patients with CFS (mean age 35 years) evaluated 42 months after the initial visit. Higher unemployment rates were found at follow-up; 77% of patients versus 68% at baseline assessment.25

Table 5.

Longitudinal assessment of employment status in chronic fatigue syndrome

| Source | Intervention | Time of follow-up Months |

Patients evaluated for work status Number |

Patients employed at baseline/follow-up Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andersen et al23 | None | 60 | 33 | 23/9 |

| Vercoulen et al24 | None | 18 | 246 | 28/29 |

| Tiersky et al25 | None | 42 | 35 | 32/23 |

| McDermott et al29 | LMP | 18 | 74 | 0/42 |

| Deale et al26 | CBT | 60 | 25 | * |

| Prins et al27 | CBT | 14 | 58 | † |

*Similar proportions of patients in cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT group; 56%) versus relaxation therapy control group (39%) were employed at 5-year follow-up. CBT group patients worked more hours per week, 36 versus 24.

†Hours working in a job were similar in the CBT group and the natural course control group.

CBT, cognitive behaviour therapy; LMP, life management programme, occupational therapy.

A few longitudinal studies have reported employment at baseline and follow-up after intervention. A long-term study of cognitive behaviour therapy versus relaxation therapy evaluated outcome at 5-year follow-up. A total of 68% of the 25 patients who received cognitive therapy rated themselves as improved compared to 36% of the 28 patients who received relaxation therapy. Similar proportions of patients were employed (56% vs 39%) but the patients in the cognitive behaviour group worked more hours per week (36 vs 24).26 In another study no treatment effect of cognitive behaviour therapy as compared with natural course was found on work rehabilitation although self-rated improvement was associated with cognitive behaviour treatment.27

A randomised controlled trial of patient education to encourage graded exercise resulted in substantial self-reported improvement in physical and occupational functioning compared with standard medical care. The receipt of sickness benefit at the start of treatment was associated with poor outcome.28 Occupational therapy with a lifestyle management programme was offered to 74 patients after median illness duration of 5 years. At follow-up 18 months later 31 (42%) of the patients had returned to new employment, voluntary work or training.29

A comprehensive review of the literature on the natural course of CFS shows that the illness run a chronic course in many sufferers and that less than 10% of participants return to premorbid levels of functioning.30 Return to work after long-time sickness absence is a complex process influenced by the severity of the disorder, personal factors, work-related factors and the compensation system.

We found that all patients who were unemployed at the initial examination received sickness or disability benefits. Norway has been criticised for high-disability payments which may undermine motivation for individuals to stay in work.31 A poor response to treatment for CFS was predicted by being in receipt of sickness benefits in a patient education study.28 In contrast, this study shows that long-term compensations to secure the socioeconomic position does not inhibit return to work, but may be essential contributors to the high proportion becoming employed at final follow-up. In addition to the financial support the contact with the social security system initiates rehabilitation activities directed towards obtaining new work when unemployed.18

It is important to disclose predictors for long-term outcome as this may suggest targets for management. We found that arthralgia at the first contact independently predicted poor long-term prognosis as evaluated by employment, FSS and WSAS scores. Arthralgia is a prominent and serious somatic symptom in the majority of patients with CFS.4 We found that depression at the first contact tended to predict poor prognosis both as to FSS and WSAS scores, but not employment. Pre-existing depression is an exclusion criterion of CFS, but many patients develop comorbid depression reactive to the chronic illness that may contribute to a poorer prognosis due to reduced illness coping.32 In contrast to our findings another study comprising 177 patients did not find any association between depression and final outcome.33

We found that FSS score at the second contact was associated with duration of illness disease at the first contact. This is compatible to the findings in a study of natural course in CFS.34 As shown above reviews on predictors of prognosis show conflicting results.13 This may be due to major differences between studies. Important differences include varying number of patients, severity of disease, patient heterogeneity and length of follow-up. Two strengths of the present study are the long-follow-up period and the relatively high-response rate as to the return of the postal questionnaire including details about occupational status. This study differs from most others because mononucleosis was a uniform trigger of CFS in all patients. One limitation of the study is that the patients were recruited from a tertiary centre and the patient cohort may represent some selection bias. Whether the written self-management programme contributed to better outcome than expected is possible. This should be addressed in controlled studies in the future.

In conclusion, about half of younger patients with CFS with long-term incapacity for work got marked improvement including full or part-time employment. Self-management strategies, long-term sickness absence benefits providing a stable financial support, in addition to occupational interventions aimed at return to work were likely contributors to the generally positive, prolonged outcome. Risk factors for transition to permanent disability pension were depression, persistence of arthralgia and disease duration.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MN and HNy were involved in data collection, manuscript preparation and revisions. HNa took part in manuscript preparation, revisions and performing of analyses. JSB was involved in data collection and manuscript preparation. All have approved the present manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: REK VEST, Norway.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I et al. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. Ann Intern Med 1994;121:953–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salit IE. Precipitating factors for the chronic fatigue syndrome. J Psychiatr Res 1997;31:59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reeves WC, Lloyd A, Vernon SD et al. Identification of ambiguities in the 1994 chronic fatigue syndrome research case definition and recommendations for resolution. BMC Health Serv Res 2003;3:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vincent A, Brimmer DJ, Whipple MO et al. Prevalence, incidence, and classification of chronic fatigue syndrome in Olmsted County, Minnesota, as estimated using the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc 2012;87:1145–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nacul LC, Lacerda EM, Pheby D et al. Prevalence of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) in three regions of England: a repeated cross-sectional study in primary care. BMC Med 2011;9:91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson A, Hickie I, Hadzi-Pavlovic D et al. What is chronic fatigue syndrome? Heterogeneity within an international multicentre study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2001;35:520–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marmot M, Feeney A, Shipley M et al. Sickness absence as a measure of health status and functioning: from the UK Whitehall II study. J Epidemiol Community Health 1995;49:124–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White PD, Thomas JM, Amess J et al. Incidence, risk and prognosis of acute and chronic fatigue syndromes and psychiatric disorders after glandular fever. Br J Psychiatry 1998;173:475–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz BZ, Shiraishi Y, Mears CJ et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome after infectious mononucleosis in adolescents. Pediatrics 2009;124:189–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor RR, Kielhofner GW. Work-related impairment and employment-focused rehabilitation options for individuals with chronic fatigue syndrome: a review. J Ment Health 2005;14:253–67. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ware NC. Sociosomatics and illness in chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychosom Med 1998;60:394–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross SD, Estok RP, Frame D et al. Disability and chronic fatigue syndrome: a focus on function. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:1098–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cairns R, Hotopf M. A systematic review describing the prognosis of chronic fatigue syndrome. Occup Med (Lond) 2005;55:20–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naess H, Sundal E, Myhr KM et al. Postinfectious and chronic fatigue syndromes: clinical experience from a tertiary-referral centre in Norway. In Vivo 2010;24:185–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nijs J, Paul L, Wallman K. Chronic fatigue syndrome: an approach combining self-management with graded exercise to avoid exacerbations. J Rehabil Med 2008;40:241–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cella M, Sharpe M, Chalder T. Measuring disability in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: reliability and validity of the work and social adjustment scale. J Psychosom Res 2011;71:124–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haukenes G, Aarli JA. [Postviral fatigue syndrome]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 1995;115:3017–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gjesdal S, Bratberg E. Diagnosis and duration of sickness absence as predictors for disability pension: results from a three-year, multi-register based* and prospective study. Scand J Public Health 2003;31:246–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Ness J, Stevent S, Bateman L et al. Postexertional malaise in women with chronic fatigue syndrome. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19:239–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J et al. The fatigue severity scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol 1989;46:1121–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lerdal A, Wahl A, Rustoen T et al. Fatigue in the general population: a translation and test of the psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the fatigue severity scale. Scand J Public Health 2005;33:123–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mundt JC, Marks IM, Shear MK et al. The work and social adjustment scale: a simple measure of impairment in functioning. Br J Psychiatry 2002;180:461–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersen MM, Permin H, Albrecht F. Illness and disability in Danish Chronic Fatigue Syndrome patients at diagnosis and 5-year follow-up. J Psychosom Res 2004;56:217–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vercoulen JH, Swanink CM, Fennis JF et al. Prognosis in chronic fatigue syndrome: a prospective study on the natural course. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996;60:489–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tiersky LA, DeLuca J, Hill N et al. Longitudinal assessment of neuropsychological functioning, psychiatric status, functional disability and employment status in chronic fatigue syndrome. Appl Neuropsychol 2001;8:41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deale A, Husain K, Chalder T et al. Long-term outcome of cognitive behavior therapy versus relaxation therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome: a 5-year follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:2038–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prins JB, Bleijenberg G, Bazelmans E et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic fatigue syndrome: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2001;357:841–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bentall RP, Powell P, Nye FJ et al. Predictors of response to treatment for chronic fatigue syndrome. Br J Psychiatry 2002;181:248–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDermott C, Richards SC, Ankers S et al. An evaluation of a chronic fatigue lifestyle management programme focusing on the outcome of return to work or training. Br J Occup Ther 2004;67:269–73. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joyce J, Hotopf M, Wessely S. The prognosis of chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome: a systematic review. QJM 1997;90:223–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Markussen S, Roed K, Rogeberg OJ et al. The anatomy of absenteeism. J Health Econ 2011;30:277–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lawn T, Kumar P, Knight B et al. Psychiatric misdiagnoses in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. JRSM Short Rep 2010;1:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pheley AM, Melby D, Schenck C et al. Can we predict recovery in chronic fatigue syndrome? Minn Med 1999;82:52–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Werf SP, de Vree B, Alberts M et al. Natural course and predicting self-reported improvement in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome with a relatively short illness duration. J Psychosom Res 2002;53:749–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.