Abstract

Temozolomide, an oral alkylating agent, is used in the treatment of glioblastoma. We describe a case of a 62-year-old woman developing jaundice with significant derangement of liver function tests on day 17 of focal radiotherapy with concomitant temozolomide. There was no structural abnormality on imaging and liver biopsy was performed. Pathology revealed absence of small terminal bile ducts affecting up to 60% of sampled portal tracts and senescence of many of the remaining small bile ducts, in keeping with a diagnosis of acute vanishing bile duct syndrome. This is a rare syndrome. It has been documented in association with Hodgkin's lymphoma and viral causes. Drugs implicated as precipitating this condition include antiseizure medications, some antibiotics, ibuprofen and antifungals. Temozolomide was stopped. The patient received supportive care, ursodeoxycholic acid 750 mg daily and cholestyramine 4 g twice daily. She was otherwise asymptomatic and her blood results returned to normal by day 129.

Background

Temozolomide (TMZ) is an oral alkylating agent that demonstrates central nervous system penetration.1 For patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma (GBM), the use of focal radiotherapy (RT) with concurrent and adjuvant TMZ has improved overall survival.2 In the landmark EORTC/NCIC trial, 7% of the selected patients with GBM receiving TMZ were reported to have grade 3 or 4 haematological toxicity.2 In clinical practice, nausea and vomiting are frequently associated with TMZ. Between January 1994 and March 2013, hepatic toxicity was reported in 44 patients with GBM treated with TMZ, including 19 fatal hepatic failure cases.3 Grant et al4 reported four cases of TMZ-induced liver toxicity documented by the Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network with histology demonstrating varying degrees of cholestasis, mild inflammation, focal hepatocellular injury and prominent bile duct damage or paucity. We report a case of vanishing bile duct syndrome (VBDS) in a patient receiving RT-TMZ postoperatively for GBM.

Case presentation

A 62-year-old woman of Indian heritage, who presented with confusion, underwent surgical resection of a 4.3 × 4.2 cm enhancing left frontal lobe lesion. The pathology revealed GBM. Her medical history included type 2 diabetes for 8 years, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia. Her glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) was 0.045 (recommended level <0.7). Medications included metformin 500 mg twice daily, gliclazide 80 mg once daily, sitagliptin 100 mg once daily, rosuvastatin 5 mg once daily, ramipril 2.5 mg once daily, diamicron 60 mg once daily, pantoprazole 40 mg once daily and dexamethasone 2 mg twice daily postsurgery. No over-the-counter medications were included.

Focal RT to a dose of 60 Gy in 30 fractions with concurrent TMZ 75 mg/m2 daily from the first to the last day of RT followed by adjuvant TMZ (150–200 mg/m2 for 5 days during each 28-day cycle) was planned. On day 15 of concurrent treatment the patient developed mild pruritus and on day 17 she presented with marked jaundice. No other symptoms had been or were present. Clinical examination revealed scleral icterus and a soft, non-tender abdomen with neither hepatomegaly nor splenomegaly. There was neither ascites nor asterixis.

Investigations

Routine blood test revealed a stable complete blood count, normal clotting screen (prothrombin time 12.3 sec, international normalised ratio 0.92), hyponatraemia of 130 mmol/L and deranged liver function tests (alkaline phosphatase 1402 U/L, alanine transaminase 747 U/L, aspartate transaminase 515 U/L, bilirubin 289 umol/L and albumin 33 g/L).

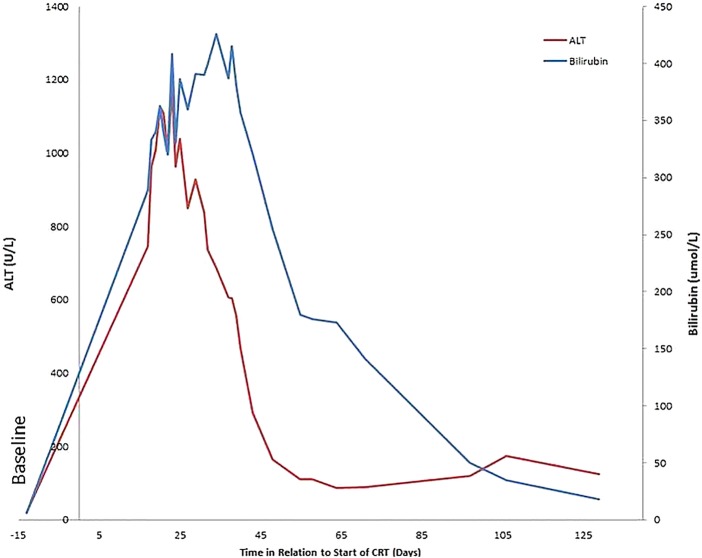

The patient was admitted and while TMZ was discontinued, she continued RT to completion. Further investigations included an abdominal ultrasound and Doppler, which revealed a moderately fatty liver of 14.4 cm with no focal lesions. There were no vascular abnormalities or intraperitoneal free fluid. The gallbladder was contracted; intrahepatic bile ducts and the common bile duct were not dilated. Viral serology was negative for hepatitis A, B and C. The Monospot test was positive for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), however, subsequent EBV DNA by PCR was negative. In addition cytomegalovirus (CMV) PCR was negative. Smooth muscle antibody, antimitochondrial antibody antinuclear antibody and anti-liver kidney microsomal antibodies were negative. Serum ferritin was elevated at 1732 µg/L (4.6–204). The patient's IgM was elevated at 7.32 g/L. Figure 1 shows the liver function tests over time with respect to the start of RT-TMZ.

Figure 1.

Bilirubin and alanine transaminase (ALT) levels in relation to the start of the concurrent temozolomide (TMZ) (day 0). CRT, chemoradiotherapy.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis included drug-induced liver injury, marker-negative autoimmune hepatitis, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, overlap syndrome, primary sclerosing cholangitis and possibly systemic infection.

Treatment

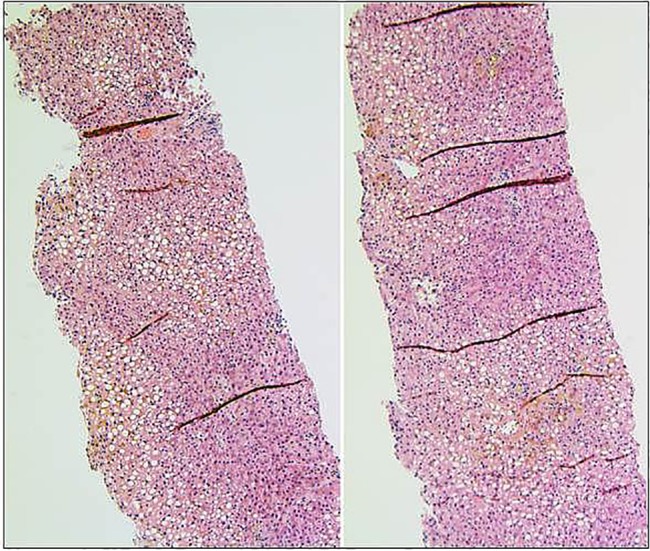

Owing to further deterioration of liver function tests despite TMZ having been discontinued for 13 days, a liver biopsy was performed on day 30. Pathology revealed absence of small terminal bile ducts affecting up to 60% of sampled portal tracts as well as senescence of many of the remaining small bile ducts, in keeping with a diagnosis of acute VBDS. There was associated cholestasis and approximately 60% steatosis but no evidence of steatohepatitis or significant fibrosis (figures 2 and 3). Steatosis was believed to be related to the patient's diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidaemia, and unrelated to cholestasis and bile duct loss. The patient received supportive care and was started on ursodeoxycholic acid 750 mg daily and cholestyramine 4 g twice daily.

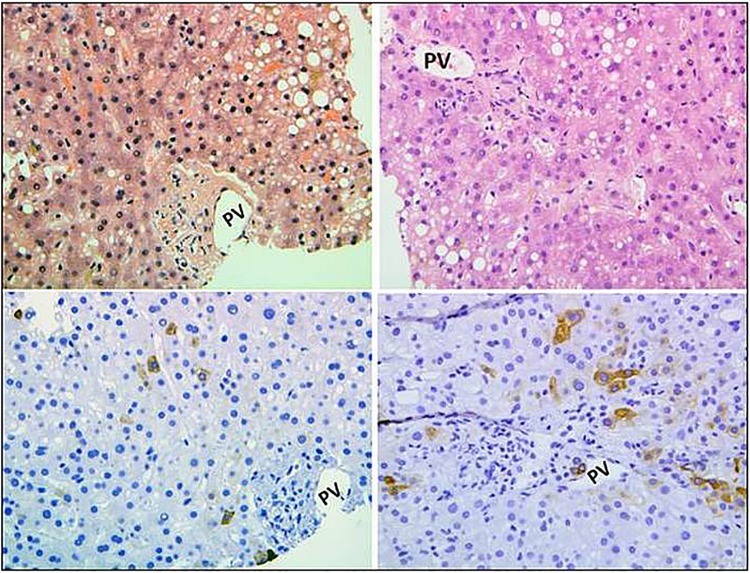

Figure 2.

H&E stain showing mild–moderate steatosis and cholestasis. The cholestasis as shown in higher magnification in figure 3 results from the loss of small terminal bile ducts (original magnification ×100).

Figure 3.

Higher magnifications of terminal portal tracts showing absence of bile ducts by H&E stains (upper panels) and cytokeratin 7 stains (lower panels) (PV, portal vein; original magnification ×200).

Outcome and follow-up

The patient completed RT and apart from mild pruritus, lasting more than 2 months, she was otherwise asymptomatic. Blood results returned to normal by day 129.

Discussion

VBDS has been related to several causes. It has been documented in cases of Hodgkin's lymphoma5 and has been reported to be related to several infective causes including CMV,6 EBV7and HIV in the context of highly active antiretroviral therapy.8 Drugs implicated as precipitating this condition include the antiseizure medications valproic acid,9 carbamazepine10 and lamotrigene.11 Antibiotics, such as meropenem12 and azithromycin,13 as well as ibuprofen,14 have also been associated. Antifungals such as terbinafine have also been linked to this condition.

Treatment strategies for this rare condition include drug withdrawal,15 steroids,16 ursodeoxycholic acid17 and even plasmaphoresis.18 Ursodeoxycholic acid, thought to have several mechanisms of action including stimulation of hepatobiliary secretion, cholangiocyte protection from hydrophobic bile acids and inhibition of apoptosis, is recommended in the treatment of similar intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct diseases.17

Learning points.

Although rare, hepatic toxicity has been related to temozolomide (TMZ) exposure.

Vanishing bile duct syndrome is a rare condition and treatment strategies involve drug withdrawal, steroids, ursodeoxycholic acid and even plasmaphoresis.

Current recommendations for patients starting TMZ include performing liver function tests prior to treatment initiation, after each treatment cycle and midway through the cycle for patients on a 42-day treatment cycle.3

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr W Mason, neuro-oncology consultant.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Rosso L, Brock CS, Gallo JM et al. . A new model for prediction of drug distribution in tumor and normal tissues: pharmacokinetics of temozolomide in glioma patients. Cancer Res 2009;69:120–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ et al. . Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 2005;352:987–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Health Canada. TEMODAL (temozolomide)—risk of liver problems—for health professionals. 07/05/2014Health Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grant LM, Kleiner DE, Conjeevaram HS et al. . Clinical and histological features of idiosyncratic acute liver injury caused by temozolomide. Dig Dis Sci 2013;58:1415–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nader K, Mok S, Kalra A et al. . Vanishing bile duct syndrome as a manifestation of Hodgkin's lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. Tumori 2013;99:e164–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tyagi I, Puri AS, Sakhuja P et al. . Co-occurrence of cytomegalovirus-induced vanishing bile duct syndrome with papillary stenosis in HIV infection. Hepatol Res 2013;43:311–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kikuchi K, Miyakawa H, Abe K et al. . Vanishing bile duct syndrome associated with chronic EBV infection. Dig Dis Sci 2000;45:160–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gnanaraj J, Fiedler P, Virata M. Vanishing bile duct syndrome in a HIV patient on HAART therapy. BMJ Case Rep 2011;2011:pii: bcr0620114369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gokce S, Durmaz O, Celtik C et al. . Valproic acid-associated vanishing bile duct syndrome. J Child Neurol 2010;25:909–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forbes GM, Jeffrey GP, Shilkin KB et al. . Carbamazepine hepatotoxicity: another cause of the vanishing bile duct syndrome. Gastroenterology 1992;102(4 Pt 1):1385–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhayana H, Appasani S, Thapa BR et al. . Lamotrigine-induced vanishing bile duct syndrome in a child. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012;55:e147–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schumaker AL, Okulicz JF. Meropenem-induced vanishing bile duct syndrome. Pharmacotherapy 2010;30:953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Juricic D, Hrstic I, Radic D et al. . Vanishing bile duct syndrome associated with azithromycin in a 62-year-old man. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2010;106:62–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alam I, Ferrell LD, Bass NM. Vanishing bile duct syndrome temporally associated with ibuprofen use. Am J Gastroenterol 1996;91:1626–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramos AM, Gayotto LC, Clemente CM et al. . Reversible vanishing bile duct syndrome induced by carbamazepine. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002;14:1019–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tajiri H, Etani Y, Mushiake S et al. . A favorable response to steroid therapy in a child with drug-associated acute vanishing bile duct syndrome and skin disorder. J Paediatr Child Health 2008;44:234–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pusl T, Beuers U. Ursodeoxycholic acid treatment of vanishing bile duct syndromes. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12:3487–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawasaki Y, Matsubara K, Hashimoto K et al. . Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced vanishing bile duct syndrome treated with plasmapheresis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2013;57:e30–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]