Abstract

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is an inflammatory disease characterized by acute inflammation and necrosis of the pancreatic parenchyma. AP is often associated with organ failure, sepsis, and high mortality. The pathogenesis of AP is still not well understood. In recent years several papers have highlighted the cellular and molecular events of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatitis is initiated by activation of digestive enzymes within the acinar cells that are involved in autodigestion of the gland, followed by a massive infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages and release of inflammatory mediators, responsible for the local and systemic inflammatory response. The hallmark of AP is parenchymal cell necrosis that represents the cause of the high morbidity and mortality, so that new potential therapeutic approaches are indispensable for the treatment of patients at high risk of complications. However, not all factors that determine the onset and course of the disease have been explained. Aim of this article is to review the role of mitogen-activated protein kinases in pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis.

Keywords: Experimental acute pancreatitis, Mitogen-activated protein kinases, Mitogen-activated protein kinases inhibitors, Cytokines, Cholecystokinin, Cerulein

Core tip: The review focuses on the role of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) in the treatment of acute pancreatitis. In fact, acute pancreatitis is a disease characterized by a marked inflammatory reaction and it is usually associated with severe upper abdominal pain, organ failure and also mortality. The activation of MAPKs is an early event in AP and exerts a central role in the onset and development of acute pancreatitis. Thanks to the pivotal function played by MAPKs in acute pancreatitis, the use of specific inhibitors may represent a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of this inflammatory disease.

INTRODUCTION

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is an inflammatory disease characterized by acute inflammation and necrosis of the pancreatic parenchyma[1]. AP is often associated with organ failure, sepsis and high mortality. Approximately 20% of patients may develop a more severe form of the disease with evidence of organ dysfunction[2]. 80% of cases of acute pancreatitis are associated with alcohol excess or gallstones; 10% are idiopathic and a further 10% are related to trauma, biliary interventions and drugs such as antibiotics, diuretics, immunosuppressants and antiretroviral agents. Pancreatitis is associated with parenchymal oedema and apoptosis[3]. The pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis (AP) is still not well understood. In recent years several papers have highlighted the cellular and molecular events of acute pancreatitis. It is now generally known that pancreatitis is initiated by premature activation of digestive enzymes within the acinar cells leading to autodigestion of the gland, followed by a massive infiltration of neutrophils and macrophages and production of inflammatory mediators released from the infiltrated pancreatic connective stroma, such as cytokines, adhesive molecules, platelet activating factors, nitric oxide, oxygen reactive species and lysosomal enzymes that represent the cause of the local and systemic inflammatory response. The hallmark of AP is parenchymal cell necrosis that is responsible for the high morbidity and mortality, so that new potential therapeutic approaches are essential for the treatment of patients at high risk of complications[1,4]. However, not all factors that determine the onset and course of the disease have been explained. Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) are serine-threonine kinases that mediate intracellular signaling associated with several cellular activities as cell proliferation, differentiation, survival, death, and transformation[5]. It has been hypothesized that activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) is an early event in AP and seems to exert a central role in development and onset of AP[6]. Aim of this article is to review the role of MAPKs in pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis and the potential of MAPKs as therapeutic targets.

MAPKS SIGNALING PATHWAY AND ACUTE PANCREATITIS: THE ROLE OF ERK AND JNK

One of the most important cascades involved in several cellular processes is the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) pathway. MAPKs play key roles in signal transduction pathways and are involved in directing cellular response to a variety of stimuli and regulate processes as gene expression, differentiation, mitosis, cell survival, and apoptosis[7-9]. There are three major classes of MAPKs in mammals, the extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) and the two stress-activated protein kinase (SAPKs) families, c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38. MAPKs are activated via a signalling cascade that is conserved from yeast to mammals[10,11]. ERK1/2 is mainly activated by mitogens stimuli through the Ras/Raf pathway but can also be activated, independently of Ras, by proinflammatory stimuli including cytokines. JNK and p38 are mainly activated by a variety of stresses and proinflammatory stimuli. Once activated, MAPKs pathways orchestrate the recruitment of gene transcription leading to activation of cellular mechanisms such as proliferation, cell differentiation, and inflammation regulated by the release of others growth factors and hormones. In recent years much interest has focused on inhibitors of the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) primarily because they have been implicated as key regulators of inflammatory diseases as acute pancreatitis. It has been demonstrated that activation of MAPKs signaling cascades is an early event in AP contributing to the progression of acute pancreatitis[12,13]. Indeed, MAPKs pathways participate to the release of inflammatory mediators highly involved in the development of inflammatory reaction from local to the systemic level[14,15]. At cellular level, time course of MAPKs activation showed that the p38 MAP kinase increases in pancreatic acinar cells most rapidly, with the peak of activity after three hours. JUN kinase activity is the highest after 12 h and after 24 h its activity becomes undetectable[16,17]. Involvement of MAPKs cascade in the pathogenesis of AP is also demonstrated by the fact that hyperstimulation with cholecystokinin (CCK) activates the two isoforms of ERK, p42 and p44, and JNK/SAPK (slowly activated compared with ERK) in pancreatic acini[12,18]. Moreover, CCK activation of JNK/SAPKs results slower than ERK’s activation, so that CCK’s concentrations for the activation of JNK/SAPKs are higher than the concentrations required for the activation of ERK. Cerulein (CER) is a cholecystokinin-pancreozymin analogue used for experimental acute pancreatitis models in rats and mice, leading to proteolytic enzyme secretion that causes pancreatic acinar autolysis with progressive interstitial oedema just one hour after injection[19]. The stimulation with a low dose of caerulein causes physiological activation both ERKs and JNK/SAPKs. Hyperstimulation both in vitro and in vivo determines an increase of JNK/SAPKs as a consequence of cellular stress. So, it has been demonstrated that after CCK or CER stimulation in vitro as well as in vivo, the activation of ERK occurs early than JNK’s activation[20]. JNK and ERK1/2 were proposed as important early mediators during caerulein-induced pancreatitis due to their pattern and activation time course[21]. Activation of ERK1/2 and JNK occurs within 5 min, peaks within 30-40 min and decreases, generally, within 1 h following caerulein hyper-stimulation. The two MAP kinases cannot be detected anymore 2 h after caerulein injection, thus confirming the very early involvement of this signalling pathway in the inflammatory cascade[22]. Active MAPKs are responsible for the phosphorylation of a variety of effector proteins including several transcription factors that trigger an inflammatory cascade[11,23]. Furthermore, in experimental models it has been shown that also reactive oxygen species (ROS) are responsible for the activation of ERK and JNK in pancreatic acinar cells[24]. In fact, the administration of caerulein in vivo stimulates the release of ROS, demonstrating a relationship between increased ROS concentrations and activation of both ERK and JNK[25]. The incubation of pancreatic acini with H2O2 causes a dose-dependent, rapid and strong activation of MAPKs: ERK, JNK and p38. These findings underline the potential role of ROS in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis, in fact large amounts of ROS are produced near to pancreatic acinar cells[26,27]. Reports describe as ERK can also be activated by exogenous ROS through EGF receptor[28,29]. High concentrations of ROS may cause cytoskeleton disruption in pancreatic acini cells directly and can modify its function via activation of MAPKs and p38, so long as these molecules play an important role in the regulation of cytoskeleton function[30]. As described, both inflammatory response and oxidative stress play essential roles on the development of acute pancreatitis, and are correlated with the severity of the disease[31,32]. Pretreatment with an antibody against tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α or blockade of TNF-α production with pentoxifylline ameliorates experimental AP[33]. The role of oxidative stress in AP has been demonstrated by the beneficial effects of antioxidants[34]. It has been demonstrated that combined treatment by simultaneous blocking of inflammation and oxidative stress pathways has positive effects as therapy in the AP. Blockade of TNF-α production with pentoxifylline partially prevented glutathione depletion and pancreatic inflammation in cerulein-induced AP[35]. Simultaneous inhibition of xanthine oxidase (XO) and TNF-α with oxypurinol and pentoxifylline significantly reduced inflammation in taurocholate-induced pancreatitis[36]. In addition, oxidative stress, as reported, causes activation of MAPKs[37], which activation leads to TNF-α production. In fact, it has been demonstrated that oxypurinol reduces p38 phosphorylation and pentoxifylline reduces ERK and JNK phosphorylation. The combination of the two treatments decreases activation of MAP kinases, and this reduction has been observed in other tissues, such as lung and liver, that are involved in systemic inflammatory process[37]. So, the p38 pathway is related to oxidative stress; ERK and JNK may be associated to inflammatory process and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. The blockade of these two processes and the concomitant inhibition of MAP kinases can represent a potential therapy to reduce the local and systemic effects in AP, as well as decrease inflammation and production of reactive species which are involved in development and progression of acute pancreatitis.

PHARMACOLOGICAL MAPKS MODULATION IN AP

Given the role of MAPKs signaling pathway in the development of AP, interest in protein kinases as drug targets has exploded in the past few years, and MAPKs pathways inhibition represents an alternative target in the treatment of AP. Pharmacological inhibitors have been identified which impact on the MAPKs ERK1/2, p38 and JNK/stress activated protein kinases and have been tested in different studies[38], as resumed in Table 1. It has been shown that selective JNK inhibition leads to amelioration of AP. Different JNK inhibitors have been used, among these, SP600125 is one of the most promising inhibitors for treatment of inflammatory diseases involving MAPKs signalling, as acute pancreatitis[39]. SP600125 is a potent, selective and reversible inhibitor of the three JNK enzymes over 300-fold more selective for JNK as compared to ERK1 and p38 MAP kinases, acting through a competitive inhibition with respect to ATP and having an IC50 of 40 nmol/L for JNK1 and JNK2, and 90 nmol/L for JNK3[40]. SP600125 was shown to cause a dose-dependent inhibition of the phosphorylation of c-Jun, and thereby the expression of inflammatory genes cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), IFN-γ, interleukin (IL)-2, TNF-α[39]. Minutoli et al[41] showed that treatment with SP600125 blunted caerulein-induced pancreatic JNK activation (90%) and partially ERK1/2 activation (45%). The observed greater effect on JNK activity obtained with SP600125 is in agreement with previous “in vitro” data showing that this compound exhibits a greater selectivity for JNK as compared to ERK1/2 MAP kinase[39]. In the same study SP600125 reduced the pancreatic content of proinflammatory mediators as TNF-α and adhesion molecules as ICAM-1 with a significant reduction in the oedema and in the inflammatory cell infiltrates, thus confirming the positive effect of MAPKs inhibition on the cell survival during AP[41]. Samuel et al[14] provided new evidence that MAP kinases (ERK, JNK, and p38) are involved in caerulein-stimulated exocrine pancreatic production of cytokines. The group used pancreatic fragments stimulated with caerulein. As awaited, the stimulation wreaked a significant increase of phospho-ERK and phospho-p38. Specific inhibitors of these MAPKs significantly reduced IL-1β and TNF-α production. Using this specific inhibitor of JNK, SP600125, they observed an attenuation of levels of both JNK and IL-1β. Therefore, there is also a connection between the activation of MAPKs and the production of cytokines, responsible for inflammatory events.

Table 1.

Summary of the actions of the mitogen-activated protein kinases inhibitors

| Inhibitor | Mechanism of action | Effects |

| SP600125 | Selective and reversible inhibitor of JNK | Dose dependent inhibition of JNK Inhibition of inflammatory genes (COX-2, IFN, IL-2, TNF-α) in vivoReduction of pancreatic inflammatory mediators (TNF-α, IL-1β) in vivo |

| CEP1347 | Potent and selective inhibitor of JNK | Dose dependent inhibition of JNK both in vivo than in vitroReduction of inflammatory cytokines |

| PD98059 | Inhibitor of ERK 1/2, prevents phosphorylation binding MEK | Protection against inflammatory process in the pancreas in vivo Protective effects probably related to the inhibition of COX-2 |

| UO126 | Selective inhibitor of MEK1 and MEK2; it prevents the activation of ERK1/2 | Protection against inflammatory process in the pancreas in vivo |

| SB203580 | Selective inhibitor of p38. Inhibition of p38 catalytic activity | Downregulation of the expression of proinflammatory mediators (TNF-α and IL-1β) in vivo |

JNK: c-jun N-terminal kinase; COX-2: Cyclooxygenase 2; IFN: Interferon; IL: Interleukin; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; ERKs: Extracellular signal-regulated kinases.

Within the MAPKs signaling cascades inhibitors, CEP-1347 is a potent and selective inhibitor of the JNK but not the p38 or the extracellular signal-regulated kinase signalling cascades, studied principally for its neuroprotective effects[42]. The correlation between inhibition of the JNK signaling cascade and pancreatitis amelioration by CEP-1347 is showed in in vitro and in vivo studies[19,43]. In vitro studies demonstrated that CEP-1347 (2 microM) inhibited caerulein-induced JNK activation in a dose dependent manner. Pretreatment of rats with CEP-1347 strongly reduced caerulein-induced pancreatic JNK activation without p38 or ERK inhibition leading to a consequent reduction of pancreatic damage as demonstrated by reduced pancreatic oedema formation and reduced histological severity of pancreatitis. CEP-1347 inhibits JNK activation in vivo and ameliorates caerulein-induced pancreatitis. Furthermore, PD98059 and UO126, both inhibitors of ERK1/2, afford significant protection against inflammatory sequelae following experimental acute pancreatitis[44].

Since AP is a condition associated with an inflammatory response, an important role is played by the cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β, which initiate and propagate acute pancreatic inflammation[45]. In fact, patients affected by acute pancreatitis show elevated serum IL-6 levels[46]. IL-6-blocking antibody attenuates experimental pancreatitis and associated pulmonary injury[47].

PD98059 mediates its inhibitory properties by binding to the ERK-specific MAP kinase MEK, therefore preventing phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (p44/p42 MAPK) by MEK1/2, with an IC50 values of 4 μmol/L and 50 μmol/L for MEK1 and MEK2. PD98059 binds to the inactive forms of MEK1 and prevents activation by upstream activators such as c-Raf[48]. Similar to PD98059, also U0126 is a selective inhibitor of MAP kinase kinases, MEK1 and MEK2, acting by inhibiting the kinase activity of MEK1/2 thus preventing the activation of MAP kinases p42 and p44. Inhibition of pancreatic ERK1/2 with PD98059 or U0126 in vivo protects against the inflammatory sequelae characteristic of the cerulein model of AP[44] confirming the role of ERK1/2 activation in the progression of AP. Moreover, the protective effects of PD98059 might be related to the inhibition of COX-2, although this mechanism has not been well investigated[49].

Evidences have shown that the local pancreatic renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is involved in AP[50]. Angiotensin II, via ROS activation, leads to activation of ERK. Leung et al[51] demonstrated in their study the involvement of ERK in regulating angiotensin II-induced IL-6 expression in pancreatic acinar cells during pancreatic inflammation. The administration of angiotensin II augmented the expression of IL-6, and angiotensin II led to ERK activation. The effect of ERK activation has been confirmed using its inhibitor, PD98059. In this model, it has been observed that the activation of ERK is mediated by the release of ROS; in fact, pretreatment with antioxidants reduced ERK activation. Blockade of AT1 receptors can represent a potential therapeutic approach to the treatment of AP, ROS mediated, too. Using two different inhibitors, SP600125 and PD98059, it has been demonstrated that they completely inhibited the activation of CER-induced pancreatic JNK and ERK[52].

CONTROVERSIAL ROLE OF P38 IN ACUTE PANCREATITIS

Despite the MAPKs have been largely involved in acute pancreatitis, the p38 has an unclear role in the development of the disease. As a matter of fact, studies have suggested that p38 MAP kinase activation could worsen acute pancreatic inflammation or protect against it[43,53]. It has been suggested that the inhibition of p38 exacerbates cerulein-induced pancreatitis in rats[53]. Others experimental evidences demonstrate that the activation, and not the inhibition, of p38 may exacerbate the progression of AP. This kinase regulates activation of nuclear factor (NF)-κB in isolated pancreatic acinar cells, but it is unclear the effective role of p38 MAP kinase in acute pancreatitis.

Moreover, p38 signaling pathway is involved in cytokine-mediated pancreatic beta-cell injury. The activation of p38 MAPK occurs through two different upstream kinases, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 3 (MKK3) and MKK6. When activated, it is involved in a lot of responses, such as apoptosis, inflammation and fibrosis[54]. Several studies showed positive effects of systemic p38 inhibitor drugs in a lot of models[55]; other studies demonstrated that systemic p38 blockade could have negative effects[56]. It has been studied the role of MKK3-p38 signaling in a model of cytokine-dependent pancreatic injury induced by multiple low doses of streptozotocin, using mice deficient for the MKK3 gene[57]. In this study, the group demonstrated that MKK3 gene deletion has a protective effect, probably due to the suppression of islet inflammation. These findings suggest that MKK3 signaling plays an essential role in the development of pancreatic injury, leading to destruction of beta-cells and hyperglycemia. p38 is activated by CCK in a time and dose dependent manner, with a peak at 5 and 10 minutes, respectively. Twait et al[58] expressed a dominant negative form of the p38 MAP kinase (DNp38) and evaluated its effect on NF-κB pathway activation in an exocrine pancreatic cell line (AR42J cells). They observed that DNp38 reduced nuclear translocation of NF-κB and decreased NF-κB-dependent gene transcription after CCK or TNF-α stimulation in AR42J cells. These results support the hypothesis that p38 regulates transcription factors such as NF-κB in pancreatic exocrine cells[59]. In a recent paper, Wang et al[60] investigated the effect of SB203580 which is the inhibitor of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase on pathologic change of pancreatic tissue and expression of TNF-α and IL-1β in rats with severe acute pancreatitis. This compound is a pyridinyl imidazole inhibitor widely used to elucidate the roles of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase acting through the blocking of the activation of MAPKAPK-2 by p38 MAPK and subsequent phosphorylation of HSP27[61]. SB203580 inhibits p38 MAPK catalytic activity by binding to the ATP-binding pocket, but does not inhibit phosphorylation of p38 MAPK by upstream kinases. Wang et al[60] showed that treatment with SB203580, inhibiting p38 MAPK signaling pathway led to a down regulation of the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α and IL-1β. All these studies highlighted the central role of MAPKs activation in acute pancreatitis pathogenesis and the real possibility to use pharmacological inhibition of these pathways for treatment of this disease.

OTHER MOLECULAR MECHANISMS INVOLVING MAPKS ACTIVATION IN AP

A number of other molecules participate to the complex network of events triggering the MAPKs activation and the inflammatory response associated with the progression and the onset of AP. In this context, recent advances showed an interaction between p38 and JNK activation and cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) and 2 (CB2) in pancreas, where non selective CB1/CB2 agonist HU210 ameliorated experimental pancreatitis[62]. However, the real role of CB1 and CB2 in acute pancreatitis has not been totally investigated. The agonist HU210 carries out a protective effect in pancreatitis also in CB1 deficient mice, and the selective CB2 antagonist, AM630, activates JNK and increases apoptosis in acute pancreatitis. The administration of cerulein in CB1 deficient mice is not responsible for a more severe pancreatitis, if compared to wild type animals, excluding a prominent role of CB1 receptor in the development of the disease[63]. On the other hand the protective effect of CB2 receptor seems to be due to the inhibition of cytokines involved in inflammatory processes, for example, IL-6, which is an activator of JNK[64]. MK2 is a downstream target of p38; the genetic disruption of the MK2 gene protects against cerulein-induced pancreatitis[65]. Several experiments with MK2 deficient mice have suggested a connection between MK2 and JNK activation: the presence of MK2 determines the activation of CB2 that causes consequently the inhibition of JNK and therefore the attenuation of acute pancreatitis. In MK2 deficient mice, the absence of MK2 creates opposite effects when CB2 receptor is activated, and leads to activation of JNK and increase of IL-6 levels. So, the activation of CB2 receptor has probably protective effects through inhibition of MAPKs cascade in experimental acute pancreatitis and the use of CB2 agonist can represent an interesting therapeutic target for humans.

In the complex molecular network involved in the regulation of inflammation during AP seems to have a role also protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2)[66], a member of the G protein coupled receptor superfamily, that plays important roles not only stimulating pro-inflammatory response but also mediates anti-inflammatory effects[67]. PAR2 is activated by activated trypsin in acute pancreatic inflammation; it has pro-inflammatory effects since activates immune and endothelial cells[68]. The protective effects of PAR-2 in acute pancreatitis were investigated in the cerulein-induced pancreatitis model. It has been demonstrated that PAR-2 can activate MAPKs[69]. In contrast, it has been shown that of PAR-2 activation decreases the cerulein-induced activation both ERK and JNK by accelerating their dephosphorylation, activating MAP kinase phosphatases (MKPs), in rat’s pancreas. The expression of MKPs provides a negative feedback mechanism for MAP kinases, and the induction of MKP’s expression may be activated both by PAR2 and by cerulein. It has been demonstrated that the protective effect obtained by using ERK’s and JNK’s inhibitors is similar to the effect observed with PAR2 activation, and ameliorates the course of acute pancreatitis[68].

An additional molecule involved in the progression of acute pancreatitis is pancreatitis-associated protein (PAP1). PAP1 is not expressed under physiological conditions whereas is overexpressed during acute pancreatitis[69]. Its activation is linked to a large number of diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and cancer[70-72]. The peak of expression of PAP1 in pancreatic tissue or juice has been observed 24 h after the induction of acute pancreatitis by cerulein[73]. In pancreatic acinar cells the augmented expression of PAP1 led to an increase of resistance to apoptosis[74,75]. Ferrés-Masó et al[76] demonstrated an anti-inflammatory role of PAP1, since its induction occurs during inflammatory diseases (pancreatitis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis). In vivo studies showed that the administration of anti-PAP1 antibodies worsened the inflammatory response. Treatment with PAP1 prevented TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation in macrophages. Gironella et al[70] furthermore demonstrated the anti-inflammatory role of PAP1 in a PAP1-deficient mice model. The anti-inflammatory mechanism of the protein is related to the activation of JAK/STAT3 pathway. PAP1 increases the transactivation activity of the nuclear transcriptional factors associated with MAPKs family. In vitro experiments on AR42J pancreatic acinar cell line showed a time-dependent induction of PAP1 gene expression after addition of PAP1 to the colture cells. It has been shown that this cellular line presented basal levels of expression of the proteins members of the MAPKs family: ERK, JNK and p38. Treatment with PAP1 enhanced the phosphorylation of MAP kinases, underlining that PAP1 signal transduction involves MAPKs family[76]. Treatment with MAPK specific inhibitors, such as SB203580 (p38 MAPK inhibitor), PD98059 (ERK inhibitor) and JNK inhibitor, caused the inhibition of the activation of PAP1. This result demonstrates that the involvement of MAPKs family is essential for the synthesis of PAP1. Some reports indicate that ERK mediates STAT3 phosphorylation both in vivo and in vitro[77]. Probably a linkage exists between MAPK and JAK/STAT3 pathway upon activation by PAP1.

Also Substance P (SP)[78,79], a neuropeptide released from nerve endings in many tissues, plays an important role in inflammatory processes. SP binds to a G protein-coupled receptor, neurokinin-1 receptor (NK1R). Pancreatic acinar cells express NK1R, SP has been found in pancreas[80], and levels of SP and NK1R are increased in AP[81]. It has been demonstrated that genetic deletion of NK1R reduces the severity of pancreatitis and pancreatitis-associated lung injury. Knockout mice deficient in the preprotachykinin-A gene, which encodes for SP, are protected against AP[82]. These evidences suggest an important interaction between SP and NK1R in development of acute pancreatitis and lung injury. Studies have shown that SP induces an increase of cytosolic calcium, and probably elevated concentration of calcium is one of the causes of AP[83]. Pancreatic acinar cells treated with SP showed an upregulation of phosphorylation of both ERK and JNK. The inhibitor U73122, a PLC inhibitor, decreased phosphorylation of ERK and JNK, as well as inhibited the activation of NF-κB[84]. These findings are important to demonstrate that drugs targeting SP could represent a therapeutic approach for the treatment of AP.

CONCLUSION

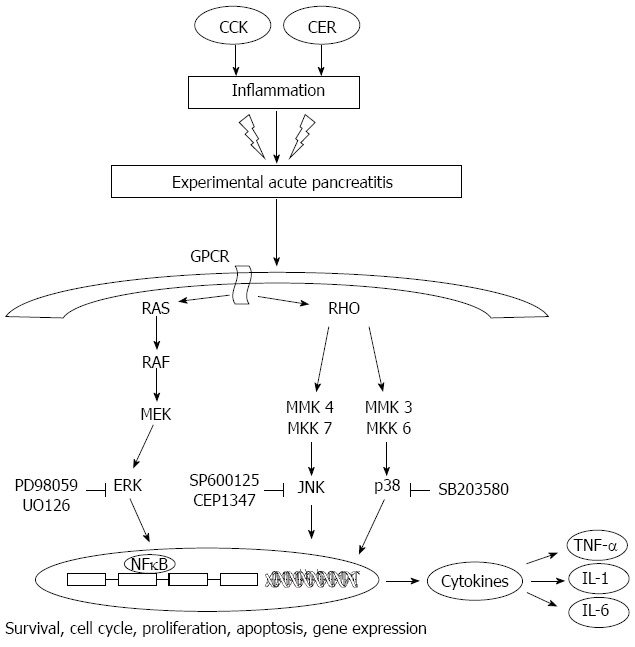

Acute pancreatitis is an autodigestive disease resulting in acute inflammation of the pancreas and MAPKs have been demonstrated to play a pivotal role in the development of the disease (Figure 1). As a consequence of the above reported observations, it is possible to speculate that the blockade of MAPKs may represent a strategic target for future treatment of acute pancreatitis.

Figure 1.

Involvement of mitogen-activated protein kinases and their inhibitors in pancreatic damage. CCK: Cholecystokinin; CER: Cerulein; GPCR: G protein coupled receptor; JNK: c-jun N-terminal kinase; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; ERKs: Extracellular signal-regulated kinases; NF: Nuclear factor; IL: Interleukin; NF: Nuclear factor.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Montecucco F S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

- 1.Bhatia M, Wong FL, Cao Y, Lau HY, Huang J, Puneet P, Chevali L. Pathophysiology of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2005;5:132–144. doi: 10.1159/000085265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neoptolemos JP, Raraty M, Finch M, Sutton R. Acute pancreatitis: the substantial human and financial costs. Gut. 1998;42:886–891. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.6.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medich DS, Lee TK, Melhem MF, Rowe MI, Schraut WH, Lee KK. Pathogenesis of pancreatic sepsis. Am J Surg. 1993;165:46–50; discussion 51-2. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80403-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lerch MM, Gorelick FS. Early trypsinogen activation in acute pancreatitis. Med Clin North Am. 2000;84:549–63, viii. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70239-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Y, Kim SC, Yu T, Yi YS, Rhee MH, Sung GH, Yoo BC, Cho JY. Functional roles of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:352371. doi: 10.1155/2014/352371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grendell JH. Acute pancreatitis. Curr Opin Gastroen. 1997;13:381–385. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raingeaud J, Gupta S, Rogers JS, Dickens M, Han J, Ulevitch RJ, Davis RJ. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and environmental stress cause p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation by dual phosphorylation on tyrosine and threonine. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7420–7426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conze D, Krahl T, Kennedy N, Weiss L, Lumsden J, Hess P, Flavell RA, Le Gros G, Davis RJ, Rincón M. c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase (JNK)1 and JNK2 have distinct roles in CD8(+) T cell activation. J Exp Med. 2002;195:811–823. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong C, Davis RJ, Flavell RA. MAP kinases in the immune response. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:55–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.091301.131133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guan KL. The mitogen activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway: from the cell surface to the nucleus. Cell Signal. 1994;6:581–589. doi: 10.1016/0898-6568(94)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seger R, Krebs EG. The MAPK signaling cascade. FASEB J. 1995;9:726–735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dabrowski A, Grady T, Logsdon CD, Williams JA. Jun kinases are rapidly activated by cholecystokinin in rat pancreas both in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5686–5690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grady T, Dabrowski A, Williams JA, Logsdon CD. Stress-activated protein kinase activation is the earliest direct correlate to the induction of secretagogue-induced pancreatitis in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;227:1–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samuel I, Zaheer A, Fisher RA. In vitro evidence for role of ERK, p38, and JNK in exocrine pancreatic cytokine production. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:1376–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmid RM, Adler G. NF-kappaB/rel/IkappaB: implications in gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:1208–1228. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70374-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Apte M, McCarroll J, Pirola R, Wilson J. Pancreatic MAP kinase pathways and acetaldehyde. Novartis Found Symp. 2007;285:200–11; discussion 211-6. doi: 10.1002/9780470511848.ch15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ren HB, Li ZS, Xu GM, Tu ZX, Shi XG, Jia YT, Gong YF. Dynamic changes of mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction in rats with severe acute pancreatitis. Chin J Dig Dis. 2004;5:123–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-9573.2004.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duan RD, Williams JA. Cholecystokinin rapidly activates mitogen-activated protein kinase in rat pancreatic acini. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:G401–G408. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1994.267.3.G401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagner AC, Mazzucchelli L, Miller M, Camoratto AM, Göke B. CEP-1347 inhibits caerulein-induced rat pancreatic JNK activation and ameliorates caerulein pancreatitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;278:G165–G172. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.278.1.G165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dabrowski A. Exocrine pancreas; molecular basis for intracellular signaling, damage and protection--Polish experience. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;54 Suppl 3:167–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Widmann C, Gibson S, Johnson GL. Caspase-dependent cleavage of signaling proteins during apoptosis. A turn-off mechanism for anti-apoptotic signals. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7141–7147. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.7141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lampel M, Kern HF. Acute interstitial pancreatitis in the rat induced by excessive doses of a pancreatic secretagogue. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1977;373:97–117. doi: 10.1007/BF00432156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sánchez I, Hughes RT, Mayer BJ, Yee K, Woodgett JR, Avruch J, Kyriakis JM, Zon LI. Role of SAPK/ERK kinase-1 in the stress-activated pathway regulating transcription factor c-Jun. Nature. 1994;372:794–798. doi: 10.1038/372794a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi C, Andersson R, Zhao X, Wang X. Potential role of reactive oxygen species in pancreatitis-associated multiple organ dysfunction. Pancreatology. 2005;5:492–500. doi: 10.1159/000087063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dabrowski A, Konturek SJ, Konturek JW, Gabryelewicz A. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of caerulein-induced acute pancreatitis. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;377:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00421-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schoenberg MH, Birk D, Beger HG. Oxidative stress in acute and chronic pancreatitis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;62:1306S–1314S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/62.6.1306S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sweiry JH, Mann GE. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1996;219:10–15. doi: 10.3109/00365529609104992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldkorn T, Balaban N, Matsukuma K, Chea V, Gould R, Last J, Chan C, Chavez C. EGF-Receptor phosphorylation and signaling are targeted by H2O2 redox stress. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;19:786–798. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.19.5.3249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carpenter G. Employment of the epidermal growth factor receptor in growth factor-independent signaling pathways. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:697–702. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.4.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schäfer C, Ross SE, Bragado MJ, Groblewski GE, Ernst SA, Williams JA. A role for the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase/Hsp 27 pathway in cholecystokinin-induced changes in the actin cytoskeleton in rat pancreatic acini. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:24173–24180. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.24173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mayer J, Rau B, Gansauge F, Beger HG. Inflammatory mediators in human acute pancreatitis: clinical and pathophysiological implications. Gut. 2000;47:546–552. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.4.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guice KS, Miller DE, Oldham KT, Townsend CM, Thompson JC. Superoxide dismutase and catalase: a possible role in established pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1986;151:163–169. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(86)90027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grewal HP, Mohey el Din A, Gaber L, Kotb M, Gaber AO. Amelioration of the physiologic and biochemical changes of acute pancreatitis using an anti-TNF-alpha polyclonal antibody. Am J Surg. 1994;167:214–28; discussion 214-28;. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(94)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sweiry JH, Shibuya I, Asada N, Niwa K, Doolabh K, Habara Y, Kanno T, Mann GE. Acute oxidative stress modulates secretion and repetitive Ca2+ spiking in rat exocrine pancreas. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1454:19–30. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(99)00021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gómez-Cambronero L, Camps B, de La Asunción JG, Cerdá M, Pellín A, Pallardó FV, Calvete J, Sweiry JH, Mann GE, Viña J, et al. Pentoxifylline ameliorates cerulein-induced pancreatitis in rats: role of glutathione and nitric oxide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:670–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pereda J, Sabater L, Cassinello N, Gómez-Cambronero L, Closa D, Folch-Puy E, Aparisi L, Calvete J, Cerdá M, Lledó S, et al. Effect of simultaneous inhibition of TNF-alpha production and xanthine oxidase in experimental acute pancreatitis: the role of mitogen activated protein kinases. Ann Surg. 2004;240:108–116. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000129343.47774.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mendelson KG, Contois LR, Tevosian SG, Davis RJ, Paulson KE. Independent regulation of JNK/p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases by metabolic oxidative stress in the liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12908–12913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.12908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mazzon E, Impellizzeri D, Di Paola R, Paterniti I, Esposito E, Cappellani A, Bramanti P, Cuzzocrea S. Effects of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway inhibition on the development of cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis in mice. Pancreas. 2012;41:560–570. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31823acd56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bennett BL, Sasaki DT, Murray BW, O’Leary EC, Sakata ST, Xu W, Leisten JC, Motiwala A, Pierce S, Satoh Y, et al. SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13681–13686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251194298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shin M, Yan C, Boyd D. An inhibitor of c-jun aminoterminal kinase (SP600125) represses c-Jun activation, DNA-binding and PMA-inducible 92-kDa type IV collagenase expression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1589:311–316. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(02)00195-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minutoli L, Altavilla D, Marini H, Passaniti M, Bitto A, Seminara P, Venuti FS, Famulari C, Macrì A, Versaci A, et al. Protective effects of SP600125 a new inhibitor of c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and extracellular-regulated kinase (ERK1/2) in an experimental model of cerulein-induced pancreatitis. Life Sci. 2004;75:2853–2866. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maroney AC, Finn JP, Connors TJ, Durkin JT, Angeles T, Gessner G, Xu Z, Meyer SL, Savage MJ, Greene LA, et al. Cep-1347 (KT7515), a semisynthetic inhibitor of the mixed lineage kinase family. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:25302–25308. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011601200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fleischer F, Dabew R, Göke B, Wagner AC. Stress kinase inhibition modulates acute experimental pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:259–265. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i2.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clemons AP, Holstein DM, Galli A, Saunders C. Cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis in the rat is significantly ameliorated by treatment with MEK1/2 inhibitors U0126 and PD98059. Pancreas. 2002;25:251–259. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200210000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Norman J. The role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1998;175:76–83. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)00240-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davies MG, Hagen PO. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Br J Surg. 1997;84:920–935. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800840707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chao KC, Chao KF, Chuang CC, Liu SH. Blockade of interleukin 6 accelerates acinar cell apoptosis and attenuates experimental acute pancreatitis in vivo. Br J Surg. 2006;93:332–338. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosen LB, Ginty DD, Weber MJ, Greenberg ME. Membrane depolarization and calcium influx stimulate MEK and MAP kinase via activation of Ras. Neuron. 1994;12:1207–1221. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90438-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li F, Lin YM, Sarna SK, Shi XZ. Cellular mechanism of mechanotranscription in colonic smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G646–G656. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00440.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsang SW, Cheng CH, Leung PS. The role of the pancreatic renin-angiotensin system in acinar digestive enzyme secretion and in acute pancreatitis. Regul Pept. 2004;119:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leung PS, Chan YC. Role of oxidative stress in pancreatic inflammation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:135–165. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.García-Hernández V, Sarmiento N, Sánchez-Bernal C, Matellán L, Calvo JJ, Sánchez-Yagüe J. Modulation in the expression of SHP-1, SHP-2 and PTP1B due to the inhibition of MAPKs, cAMP and neutrophils early on in the development of cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis in rats. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842:192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang J, Murphy C, Denham W, Botchkina G, Tracey KJ, Norman J. Evidence of a central role for p38 map kinase induction of tumor necrosis factor alpha in pancreatitis-associated pulmonary injury. Surgery. 1999;126:216–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kyriakis JM, Avruch J. Mammalian MAPK signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation: a 10-year update. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:689–737. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jackson JR, Bolognese B, Hillegass L, Kassis S, Adams J, Griswold DE, Winkler JD. Pharmacological effects of SB 220025, a selective inhibitor of P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, in angiogenesis and chronic inflammatory disease models. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284:687–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kumar S, Boehm J, Lee JC. p38 MAP kinases: key signalling molecules as therapeutic targets for inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:717–726. doi: 10.1038/nrd1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fukuda K, Tesch GH, Yap FY, Forbes JM, Flavell RA, Davis RJ, Nikolic-Paterson DJ. MKK3 signalling plays an essential role in leukocyte-mediated pancreatic injury in the multiple low-dose streptozotocin model. Lab Invest. 2008;88:398–407. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Twait E, Williard DE, Samuel I. Dominant negative p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase expression inhibits NF-kappaB activation in AR42J cells. Pancreatology. 2010;10:119–128. doi: 10.1159/000290656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Han B, Ji B, Logsdon CD. CCK independently activates intracellular trypsinogen and NF-kappaB in rat pancreatic acinar cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C465–C472. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.3.C465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang XY, Tang QQ, Zhang JL, Fang MY, Li YX. Effect of SB203580 on pathologic change of pancreatic tissue and expression of TNF-α and IL-1β in rats with severe acute pancreatitis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014;18:338–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cuenda A, Rouse J, Doza YN, Meier R, Cohen P, Gallagher TF, Young PR, Lee JC. SB 203580 is a specific inhibitor of a MAP kinase homologue which is stimulated by cellular stresses and interleukin-1. FEBS Lett. 1995;364:229–233. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00357-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Michalski CW, Laukert T, Sauliunaite D, Pacher P, Bergmann F, Agarwal N, Su Y, Giese T, Giese NA, Bátkai S, et al. Cannabinoids ameliorate pain and reduce disease pathology in cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1968–1978. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Michler T, Storr M, Kramer J, Ochs S, Malo A, Reu S, Göke B, Schäfer C. Activation of cannabinoid receptor 2 reduces inflammation in acute experimental pancreatitis via intra-acinar activation of p38 and MK2-dependent mechanisms. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;304:G181–G192. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00133.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wright KL, Duncan M, Sharkey KA. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors in the gastrointestinal tract: a regulatory system in states of inflammation. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:263–270. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tietz AB, Malo A, Diebold J, Kotlyarov A, Herbst A, Kolligs FT, Brandt-Nedelev B, Halangk W, Gaestel M, Göke B, et al. Gene deletion of MK2 inhibits TNF-alpha and IL-6 and protects against cerulein-induced pancreatitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G1298–G1306. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00530.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vergnolle N. Review article: proteinase-activated receptors - novel signals for gastrointestinal pathophysiology. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:257–266. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cenac N, Coelho AM, Nguyen C, Compton S, Andrade-Gordon P, MacNaughton WK, Wallace JL, Hollenberg MD, Bunnett NW, Garcia-Villar R, et al. Induction of intestinal inflammation in mouse by activation of proteinase-activated receptor-2. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1903–1915. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64466-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Namkung W, Yoon JS, Kim KH, Lee MG. PAR2 exerts local protection against acute pancreatitis via modulation of MAP kinase and MAP kinase phosphatase signaling. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295:G886–G894. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00053.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Keim V, Rohr G, Stöckert HG, Haberich FJ. An additional secretory protein in the rat pancreas. Digestion. 1984;29:242–249. doi: 10.1159/000199041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gironella M, Iovanna JL, Sans M, Gil F, Peñalva M, Closa D, Miquel R, Piqué JM, Panés J. Anti-inflammatory effects of pancreatitis associated protein in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2005;54:1244–1253. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.056309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Duplan L, Michel B, Boucraut J, Barthellémy S, Desplat-Jego S, Marin V, Gambarelli D, Bernard D, Berthézène P, Alescio-Lautier B, et al. Lithostathine and pancreatitis-associated protein are involved in the very early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22:79–88. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xie MJ, Motoo Y, Iovanna JL, Su SB, Ohtsubo K, Matsubara F, Sawabu N. Overexpression of pancreatitis-associated protein (PAP) in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:459–464. doi: 10.1023/a:1022520212447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Graf R, Schiesser M, Lüssi A, Went P, Scheele GA, Bimmler D. Coordinate regulation of secretory stress proteins (PSP/reg, PAP I, PAP II, and PAP III) in the rat exocrine pancreas during experimental acute pancreatitis. J Surg Res. 2002;105:136–144. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2002.6387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ortiz EM, Dusetti NJ, Vasseur S, Malka D, Bödeker H, Dagorn JC, Iovanna JL. The pancreatitis-associated protein is induced by free radicals in AR4-2J cells and confers cell resistance to apoptosis. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:808–816. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70595-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Malka D, Vasseur S, Bödeker H, Ortiz EM, Dusetti NJ, Verrando P, Dagorn JC, Iovanna JL. Tumor necrosis factor alpha triggers antiapoptotic mechanisms in rat pancreatic cells through pancreatitis-associated protein I activation. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:816–828. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.16491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ferrés-Masó M, Sacilotto N, López-Rodas G, Dagorn JC, Iovanna JL, Closa D, Folch-Puy E. PAP1 signaling involves MAPK signal transduction. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:2195–2204. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0040-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chung J, Uchida E, Grammer TC, Blenis J. STAT3 serine phosphorylation by ERK-dependent and -independent pathways negatively modulates its tyrosine phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6508–6516. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bowden JJ, Garland AM, Baluk P, Lefevre P, Grady EF, Vigna SR, Bunnett NW, McDonald DM. Direct observation of substance P-induced internalization of neurokinin 1 (NK1) receptors at sites of inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8964–8968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thurston G, Baluk P, Hirata A, McDonald DM. Permeability-related changes revealed at endothelial cell borders in inflamed venules by lectin binding. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H2547–H2562. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.6.H2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sjödin L, Gylfe E. A selective and potent antagonist of substance P receptors on pancreatic acinar cells. Biochem Int. 1992;27:145–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bhatia M, Saluja AK, Hofbauer B, Frossard JL, Lee HS, Castagliuolo I, Wang CC, Gerard N, Pothoulakis C, Steer ML. Role of substance P and the neurokinin 1 receptor in acute pancreatitis and pancreatitis-associated lung injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4760–4765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bhatia M, Slavin J, Cao Y, Basbaum AI, Neoptolemos JP. Preprotachykinin-A gene deletion protects mice against acute pancreatitis and associated lung injury. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G830–G836. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00140.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Frick TW, Fernández-del Castillo C, Bimmler D, Warshaw AL. Elevated calcium and activation of trypsinogen in rat pancreatic acini. Gut. 1997;41:339–343. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.3.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ramnath RD, Sun J, Bhatia M. Role of calcium in substance P-induced chemokine synthesis in mouse pancreatic acinar cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:1339–1348. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]