Abstract

Aims

Femoroacetabular Junction Impingement (FAI) describes abnormalities in the shape of the femoral head–neck junction, or abnormalities in the orientation of the acetabulum. In the short term, FAI can give rise to pain and disability, and in the long-term it significantly increases the risk of developing osteoarthritis. The Femoroacetabular Impingement Trial (FAIT) aims to determine whether operative or non-operative intervention is more effective at improving symptoms and preventing the development and progression of osteoarthritis.

Methods

FAIT is a multicentre superiority parallel two-arm randomised controlled trial comparing physiotherapy and activity modification with arthroscopic surgery for the treatment of symptomatic FAI. Patients aged 18 to 60 with clinical and radiological evidence of FAI are eligible. Principal exclusion criteria include previous surgery to the index hip, established osteoarthritis (Kellgren–Lawrence ≥ 2), hip dysplasia (centre-edge angle < 20°), and completion of a physiotherapy programme targeting FAI within the previous 12 months. Recruitment will take place over 24 months and 120 patients will be randomised in a 1:1 ratio and followed up for three years. The two primary outcome measures are change in hip outcome score eight months post-randomisation (approximately six-months post-intervention initiation) and change in radiographic minimum joint space width 38 months post-randomisation. ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01893034.

Cite this article: Bone Joint Res 2014;3:321–7.

Keywords: Femoroacetabular Impingment, Hip Arthroscopy, Physiotherapy, Randomised Controlled Trial, Osteoarthritis

Introduction

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) describes morphological abnormalities of the femoral head–neck junction (cam impingement) or acetabulum (pincer impingement). As a consequence of this abnormal morphology, when the hip flexes and internally rotates, the femoral head–neck junction abuts the acetabular rim, resulting in labral damage and delamination of the adjacent cartilage.1 In a study of 2081 young healthy adults, 35% of males and 10% of females displayed cam morphology, and 34% of males and 17% of females displayed pincer morphology.2 In the short-term, FAI can give rise to pain and disability, and in the long term it increases the risk of developing osteoarthritis.3

Despite the considerable prevalence of FAI morphology, only a proportion of individuals develop pain or osteoarthritis,3 yet the condition is responsible for a significant burden of disease. Predictive values are dependent on the characteristics of the cohort, method used to define the presence of FAI and length of follow-up. In an asymptomatic population, the relative risk of developing hip pain within four years in the presence of FAI morphology is 4.3 (95% confidence interval (CI) 2.3 to 7.8) with a positive predictive value of 15.9%.4 The positive predictive value for the development of osteoarthritis is estimated at 6% to 25%, with follow-up times of five5 to 19 years.6 It remains unclear whether pain secondary to FAI is a reliable predictor of future osteoarthritis and low positive predictive values mean current clinical care must focus on treating symptoms rather than preventing future disease. Nevertheless, FAI is a potentially modifiable cause of osteoarthritis, and cam lesions have been identified in more than 50% of patients undergoing total hip replacement.7

There is uncertainty as to how symptomatic FAI is best treated8 and the principal two management options are physiotherapy with activity modification or surgery. Both modalities have been shown to improve symptoms in the short term,9-14 however, no published studies compare efficacy with each other or with sham procedures. It is not known whether treatment provides sustained symptomatic benefit in the long term, or whether it delays or prevents development of osteoarthritis. These two treatment modalities were chosen as comparators in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) after our feasibility study demonstrated equipoise amongst clinicians specialising in the field.8 The feasibility study results have guided study design and the protocol was drafted in accordance with the SPIRIT 2013 Statement.15

Objectives

Primary objectives

To determine whether arthroscopic surgery or physiotherapy and activity modification is more effective in improving symptoms and preventing the development and progression of osteoarthritis in patients with symptomatic FAI. The co-primary outcome measures are change in Hip Outcome Score (Activities of Daily Living Subscale)16 eight months post-randomisation and change in minimum joint space width (mJSW) (measured on anteroposterior pelvic radiographs)17 38 months post-randomisation.

Secondary objectives

To compare cost effectiveness of physiotherapy and activity modification with arthroscopic surgery.

To evaluate the performance of disease biomarkers (physiological MRI, urine, serum and synovial biochemical markers).

Materials and Methods

Study design

The Femoroacetabular Impingement Trial (FAIT) is an assessor-blinded multicentre superiority parallel two-arm RCT comparing physiotherapy and activity modification with arthroscopic surgery for the treatment of symptomatic FAI.

Comparators

Non-operative treatment of FAI aims to minimise impingement through avoidance of activities that require repeated hip flexion and modification of joint biomechanics. Improving core stability and movement control, with particular emphasis on strengthening external rotator and abductor muscle groups9 is thought to limit forceful impaction of the femoral neck against the acetabular rim. Physiotherapy represents first line care in many centres as a result of available expertise, local funding allowances or clinician preference based on existing evidence. It describes a heterogeneous group of therapies, and a standardised treatment protocol for this study was agreed by a panel of specialists based on experience and current literature.

Either open or arthroscopic surgery can be performed to re-contour the femoral neck or acetabular rim by burring away the impinging bone. The number of surgical procedures performed in England to treat FAI has increased by 442% over the past ten years.18 Arthroscopic surgery is performed more than twice as frequently as open surgery and studies show that it carries lower rates of complication with outcomes equal to or better than alternatives.19 Arthroscopic surgery was therefore adopted as the comparator and low complication rates20 make it a potentially acceptable alternative to physiotherapy and activity modification.

Sham surgery was considered as a third treatment arm, however, it was felt this would make recruitment difficult. A survey of orthopaedic surgeons in Canada revealed only 24.8% supported a sham surgery control arm.21

Participants

Eligible patients will be symptomatic, aged 18 to 60 years and have clinical and radiolographic evidence of FAI. Exclusion criteria include radiological evidence of established osteoarthritis (Kellgren–Lawrence16 ≥ 2) or hip dysplasia (centre–edge angle < 20o) on anteroposterior pelvic radiographs, as these individuals are less likely to benefit from the study interventions;14 previous surgery to the index hip or completion of a physiotherapy programme targeting FAI within the last year, in order to counter selection bias towards patients who have failed prior intervention; medical conditions that prevent surgical intervention and contraindications to MRI (Table I). Patients will be offered continued participation should contraindications to imaging arise during follow-up, for example, pregnancy. In such circumstances, contraindicated imaging modalities will be omitted for any particular visit.

Table I.

Table I: Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient with symptomatic FAI | Previous surgery to index hip | |

| Age 18 to 60 | Established osteoarthritis (Kellgren–Lawrence ≥ 2) | |

| Clinical and radiological evidence of FAI | Hip dysplasia (centre–edge angle < 20° on anteroposterior radiograph) | |

| Competent to consent | Completion of physiotherapy programme targeting FAI within preceding 12 months | |

| Medical conditions that preclude surgical intervention | ||

| Contraindication to MRI | ||

FAI, femoroacetabular impingement

Recruitment

Patients will be recruited from NHS clinics of at least three hospitals in England including teaching hospitals and district general hospitals. A member of the surgical team will introduce the trial to eligible patients, and if they would like more information, they will be introduced to a member of the research team at this initial clinic appointment. Patients opt in by providing their contact details and written consent to be approached again once they have had at least 48 hours to consider the information. A baseline assessment will take place approximately four weeks after the initial approach. Consent and randomisation will take place at this baseline visit.

Assignment of treatment

Patients will be randomly assigned to hip arthroscopy or physiotherapy with 1:1 allocation using a telephone system provided by the Oxford Clinical Trials Unit. Simple randomisation is used for the first 12 patients followed by minimisation with a random element (p = 0.8) and using stratification factors: age (< 40 or ≥ 40 years), gender, recruitment site and baseline activities of daily living (ADL) hip outcome score (HOS)22 subscale (< 65 or ≥ 65). The HOS threshold is derived from baseline scores in comparable cohorts.23,24

Interventions

Non-operative intervention: physiotherapy and activity modification

Participants will receive physiotherapy following a goal-based programme with up to eight sessions over five months. During the initial assessment, goals will be agreed between the patient and physiotherapist based on the individual needs of the patient and their desired level of function. The physiotherapy programme will aim to address these goals alongside a standardised treatment checklist that places emphasis on muscle strengthening to improve core stability and movement control. Treatment will be led by physiotherapists who have received training for this study during site visits to ensure treatment standardisation. Patients are encouraged to continue exercises at home and to refrain from activities requiring the extremes of hip flexion, abduction and internal rotation (impingement position). Patient attendance and compliance with the treatment plan will be recorded. Should participants achieve all their goals within five months, they will be discharged and asked to continue their exercises and activity modification in the community. There will be no physiotherapy sessions in the four weeks preceding follow-up appointments to ensure symptoms are stable when assessed.

Operative: hip arthroscopy

Participating surgeons perform over 100 hip arthroscopies each year and will meet prior to commencing recruitment to ensure standardisation of technique. Hip morphology will be assessed intra-operatively under arthroscopic vision and fluoroscopy. Bone that is seen to be causing impingement on flexing, abducting and internally rotating the hip will be excised with a burr. Damage to the labrum or articular cartilage will also be addressed: labral tears will be repaired if possible using anchors, or otherwise debrided. Articular cartilage damage will be debrided to a stable base, and in areas of full thickness loss, microfracture will be performed. Microfracture involves the creation of small holes in the subchondral bone to facilitate cartilage regeneration. Patients will be discharged home once medically fit and after assessment by the physiotherapy team. They will be allowed to fully-weight bear immediately after surgery unless they received microfracture, when they will be required to touch-weight-bear for three weeks, partial-weight-bear for three weeks, and then fully-weight-bear. Participants will be asked to avoid high-impact exercise for eight weeks unless they received microfracture, at which point, this increases to 12 weeks. There will be no restriction in the range of movement permitted post-operatively. Patients will be reviewed in the NHS clinic of their surgeon six weeks after surgery to monitor for surgical complications. Follow-up thereafter is with the study team. Participants who undergo surgery follow a routine physiotherapy programme post-operatively that focuses on rehabilitation and maintaining a functional range of movement. This is a different regime to that employed for the non-operative intervention. The number of sessions and duration of treatment will depend on individual patient requirements. Patients will be discharged once they have regained their desired level of function or their improvement has plateaued. There will be no physiotherapy sessions in the four weeks preceding follow-up appointments as per the non-surgical treatment arm.

Treatment modification

The primary outcome will be measured eight months post-randomisation and crossover is not permitted before this assessment. Any time thereafter, if a participant feels they have not reached their goals and seek further intervention with respect to their index hip, they will be reviewed by a member of the recruiting surgical team and offered entry into the alternative treatment arm.

Concomitant care

Intra-articular steroid injections are not permitted after recruitment into the study as these may limit the ability to compare efficacy of the study treatment arms. All other concomitant treatments are permitted.

Study outcomes

Primary outcome measures: improvement of symptoms

The primary outcome measure is change in the hip outcome score (HOS),20 which was specifically designed as an outcome instrument for hip arthroscopy and is considered the most reliable and valid measure of self-reported physical function in this population.25 It comprises subscales for ADL and sport, and this study is powered to detect a difference in ADL. The primary outcome will be measured eight months post-randomisation, equating to approximately six months after intervention commences. This time point was chosen since i) a clinically meaningful difference in the ADL HOS of nine points is detectable six months after hip arthroscopy;23 ii) our feasibility study showed that 94% of patients are happy to trial a treatment for six months, but no longer, without improvement in their symptoms8 and iii) this reflects current routine clinic appointment scheduling and increases clinical relevance. An audit of outcomes at the co-ordinating centre demonstrated that the majority of symptom improvement takes place within six months of intervention, although improvement continues beyond 12 months. This finding has also been demonstrated in other centres.26

Primary outcome measures: prevention of osteoarthritis

Change in radiographic mJSW 38 months post-randomisation is also a primary outcome measure. Measurements will be performed by trained readers on standing anteroposterior pelvic radiographs using a validated software package (HipMorf 2.0, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK). Three-year follow-up is selected as responsiveness to change of this measurement improves significantly in studies exceeding two years.27,28

Secondary outcome measures: improvement of symptoms

Evidence for reliability, validity and responsiveness of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMS) in FAI is limited29 and the following additional PROMs will be collected as secondary outcome measures: non-arthritic hip score (NAHS),30 international hip outcome score (iHOT-33),31 hip and groin outcome score (HAGOS),32 and Oxford hip score (OHS).33 PainDETECT34 will be used to establish the nature and location of pain. Psychological factors will be assessed using the hospital and anxiety depression scale (HADS).35 At baseline, in addition to the HOS relating to current symptoms, patients will be asked to complete an additional HOS to indicate the symptoms they expect to experience after treatment is complete. The aim of this questionnaire is to determine how well treatment outcome meets expectations.

Secondary outcome measures: prevention of osteoarthritis

Alternative measures of osteoarthritis may confer advantages over radiographic mJSW,17 and secondary outcome measures include regional changes in JSW, Kellgren–Lawrence grading, cartilage morphology on MRI and whole-joint semi-quantitative measures of osteoarthritis.36 Though the primary outcome measure is change in mJSW, the proportion of progressors in each treatment arm will also be calculated.

Secondary outcome measures: health economics

Health outcomes will be assessed at each trial follow-up using the EuroQol EQ-5D questionnaire37 and collection of information pertaining to the delivery of health care and ability of patients to work. The main health economic outcome is net cost per quality-adjusted life year gained. Full details are included in the ‘health economic analysis plan’ that will be finalised prior to the unblinding of the data for analysis.

Exploratory outcome measures

Evaluation of disease biomarkers

A number of novel biomarkers have been proposed for the evaluation of early osteoarthritis. These offer potential as tools to diagnose the earliest osteoarthritis when disease remains potentially reversible, and as measures of treatment efficacy within short timeframes. However, further validation is essential. The MRI protocol for this study includes T2 mapping and T1 Rho sequences that assess the biochemical composition of cartilage.38 Fasting serum and urine samples will be collected at study assessments to measure markers of cartilage metabolism.39 Synovial fluid will be collected at the time of surgery if an effusion is present, and used to validate serum and urine biomarkers. The performance of the biomarkers will be assessed through their relationship with primary and secondary outcome measures.

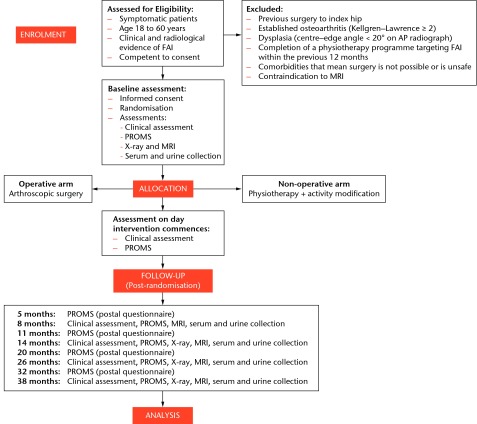

Assessment schedule

Outcome measure collection will be scheduled post-randomisation (Fig. 1). Intervention will commence approximately eight weeks after randomisation. This equates to 12 weeks after patients were first seen in clinic, in line with average waiting times for treatment at participating centres. Deviations from this schedule will be explored to seek possible solutions, particularly in relation to differences in waiting times for each treatment arm. On the day intervention commences, clinical examination and collection of PROM data will be repeated to enable evaluation of the stability of symptoms and signs. The acceptable window for appointments is four weeks either side of the calculated date. As a contingency, to ensure outcome measures are assessed at an appropriate time point after intervention, if treatment is delayed and commences more than 12 weeks post-randomisation, the assessment schedule will be shifted to a post-intervention timescale. This also ensures follow-up coincides with routine hospital visits. The HOS will continue to be collected at eight and 14 months post-randomisation via postal questionnaire to allow comparison between assessment schedules. The study is designed with regular follow-up to map symptom fluctuation40 and the trajectory of improvement in this population.

Fig. 1.

Femoroacetabular Impingement Trial (FAIT) flowchart.

Masking

Trial co-ordinators and those providing clinical care will not be masked to treatment allocation, however, all members of the research team performing post-randomisation clinical assessments will be blinded. Participants will be asked not to disclose their treatment and will wear shorts to cover any scars. Data entry will be performed by staff members independent of the study team. Blinding will be maintained when performing assays of biochemical biomarkers and imaging study interpretation.

Statistical analysis

Measure of outcome

Trial statisticians will conduct all analyses and all reporting will follow CONSORT guidelines. Primary analysis will be based on the ‘intention to treat’ population of all randomised participants regardless of their compliance with the protocol. Hypothesis tests will be two-sided with a 5% significance level. Study analysis will take place in two stages: i) after all participants have completed their eight-month post-randomisation assessment and ii) after all follow-up is complete. Linear regression analysis (ANCOVA) will be used to examine differences between treatment arms for change in the ADL HOS at eight months and mJSW at 38 months in multivariate frameworks, adjusting for baseline minimisation factors and other relevant patient characteristics. Diagnostic checks will be performed to verify model assumptions. Secondary outcome measures will be analysed using linear (for continuous outcomes) or logistic (for binary outcomes) multivariate regression with appropriate covariate adjustment. Secondary analysis of PROMS will take into account the multiple data points using random effects regression methodology. Subgroup analysis will include measures of osteoarthritis on baseline imaging and at arthroscopy, given that studies suggest this is an important predictor of outcome.41 Missing data patterns will be explored and addressed according to current best practice. Further details are included in the ‘statistical analysis plan’ that will be finalised prior to the unblinding of the data for analysis.

Sample size

This study is powered to detect a clinically important difference in the HOS ADL subscale eight months post-randomisation. The minimal clinically important difference is nine points23 with a standard deviation of 14 at six months post-intervention.26 Using a statistical significance of 5% and a power of 90%, 51 patients are required for each arm. Accounting for a possible 15% loss to follow-up, 60 patients will be recruited to each arm (total 120 patients). This sample size is also sufficient to detect a clinically important change in mJSW at three years42 with a statistical significance of 5% and power of 90% where the minimum clinically important difference is 0.5mm28 and standard deviation 0.62.43

Patients frequently present with bilateral symptoms secondary to FAI and the most symptomatic hip will be treated first. Should a patient seek treatment for their contralateral hip whilst follow-up continues for their study hip, this hip will not be included in the trial but the same study outcome measures will be collected until 38-month follow-up is complete for the study hip. These results will be used in the data analysis for covariate adjustment. Treatment allocation for the contralateral hip will be through patient choice, given i) results from this hip will not be used in the primary analysis, ii) clinicians remain in equipoise with respect to treatment allocation, or iii) patients may have a strong treatment preference based on results of the intervention already received, hence aiding patient retention. Treatment of the contralateral hip will not commence until the eight-month post-randomisation assessment is complete for the study hip.

Organisation

Monitoring

A data monitoring committee (DMC) will review accumulating data and make recommendations to the trial steering committee (TSC) with respect to trial conduct and participant safety. DMC and TSC charters outline the roles and responsibilities of these committees. Power calculations will be validated by comparing the standard deviation of the ADL HOS baseline data, with values used for sample size calculations. Sample size may be increased based on these findings and treatment effect will not be considered until recruitment is complete.

Trial status

Recruitment commenced in July 2013 and is anticipated to conclude in June 2015. At the time of submission, 62 patients have been randomised and 14 have completed eight-month follow-up.

Conclusion

Equipoise exists among clinicians treating FAI and the results of this study will guide clinical management of the condition.8 Surgical treatment of FAI is not funded by the NHS in many regions. Should surgery demonstrate superior efficacy over physiotherapy at improving symptoms and preventing the development of osteoarthritis, with a favourable health economic analysis, it may be appropriate to review these funding decisions.

Funding Statement

Support is received from the NIHR Oxford Musculoskeletal Biomedical Research Unit, Thames Valley Clinical Research Network, Arthritis Research UK Centre of Excellence for Sports, Exercise and Osteoarthritis, a Royal College of Surgeons and Dunhill Medical Trust Research Fellowship, and Orthopaedic Research UK. The funding sources have no role in the design, execution, data analysis, or publication of this study. Mr Andrade reports consultancy fees and payment for lectures from Smith & Nephew. Mr Hollinghurst reports consultancy fees from Arthrex Stryker and Mr Taylor reports payment for lectures from Teaching Zimmer/Corin, none of which are related to this article.

Footnotes

Author contributions:A. J. R. Palmer: Study design, Study implementation and refinement of the study protocol, Approved the final manuscript, Principal Investigator.

V. Ayyar-Gupta: Study implementation and refinement of the study protocol, Approved the final manuscript.

S. J. Dutton: Expertise in trial statistics, refinement of the study protocol, Approved the final manuscript.

I. Rombach: Expertise in trial statistics, refinement of the study protocol, Approved the final manuscript.

C. D. Cooper: Study implementation, refinement of the study protocol, Approved the final manuscript.

T. C. Pollard: Refinement of the study protocol, Approved the final manuscript.

D. Hollinghurst: Refinement of the study protocol, Approved the final manuscript.

A. Taylor: Refinement of the study protocol, Approved the final manuscript.

K. L. Barker: Expertise in physiotherapy, refinement of the study protocol, Approved the final manuscript.

E. G. McNally: Expertise in imaging, refinement of the study protocol, Approved the final manuscript.

D. J. Beard: Expertise in clinical trial methodology, refinement of the study protocol, Approved the final manuscript.

A. J. Andrade: Refinement of the study protocol, Approved the final manuscript.

A. J. Carr: Refinement of the study protocol, Approved the final manuscript.

S. Glyn-Jones: Conceived study idea, study design, refinement of the study protocol, Approved the final manuscript, Chief Investigator.

ICMJE Conflict of Interest:None declared.

References

- 1.Ganz R, Parvizi J, Beck M, et al. Femoroacetabular impingement: a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003;417:112–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laborie LB, Lehmann TG, Engesæter IØ, et al. Prevalence of radiographic findings thought to be associated with femoroacetabular impingement in a population-based cohort of 2081 healthy young adults. Radiology 2011;260:494–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agricola R, Waarsing JH, Arden NK. , et al. Cam impingement of the hip: a risk factor for hip osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2013;9:630–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khanna V, Caragianis A, Diprimio G, Rakhra K, Beaulé PE. Incidence of hip pain in a prospective cohort of asymptomatic volunteers: is the cam deformity a risk factor for hip pain? Am J Sports Med 2014;42:793–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agricola R, Heijboer MP, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, et al. Cam impingement causes osteoarthritis of the hip: a nationwide prospective cohort study (CHECK). Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:918–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholls AS, Kiran A, Pollard TC, et al. The association between hip morphology parameters and nineteen-year risk of end-stage osteoarthritis of the hip: a nested case-control study. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:3392–3400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clohisy JC, Dobson MA, Robison JF, et al. Radiographic structural abnormalities associated with premature, natural hip-joint failure. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 2011;93-A(Suppl 2):3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmer AJ, Thomas GE, Pollard TC, et al. The feasibility of performing a randomised controlled trial for femoroacetabular impingement surgery. Bone Joint Res 2013;2:33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wall PD, Fernandez M, Griffin DR, Foster NE. Nonoperative treatment for femoroacetabular impingement: a systematic review of the literature. PM R 2013;5:418–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bedi A, Chen N, Robertson W, Kelly BT. The management of labral tears and femoroacetabular impingement of the hip in the young, active patient. Arthroscopy 2008;24:1135–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ng VY, Arora N, Best TM, Pan X, Ellis TJ. Efficacy of surgery for femoroacetabular impingement: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med 2010;38:2337–2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clohisy JC, St John LC, Schutz AL. Surgical treatment of femoroacetabular impingement: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010;468:555–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gedouin JE, May O, Bonin N, et al. Assessment of arthroscopic management of femoroacetabular impingement. A prospective multicenter study. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2010;96(8 Suppl):S59–S67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Philippon MJ, Briggs KK, Yen YM, Kuppersmith DA. Outcomes following hip arthroscopy for femoroacetabular impingement with associated chondrolabral dysfunction: minimum two-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 2009;91-B:16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis 1957;16:494–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conaghan PG, Hunter DJ, Maillefert JF, Reichmann WM, Losina E. Summary and recommendations of the OARSI FDA osteoarthritis Assessment of Structural Change Working Group. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011;19:606–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palmer A, Thomas G, Whitwell D, et al. Temporal Trends in Arthroscopy and Joint Preserving Surgery of the Hip from 2001 to 2010: A Study of 12,684 Procedures using the HES Database. Bone Joint J 2013;95-B(Supp 1):96. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuda DK, Carlisle JC, Arthurs SC, Wierks CH, Philippon MJ. Comparative systematic review of the open dislocation, mini-open, and arthroscopic surgeries for femoroacetabular impingement. Arthroscopy 2011;27:252–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papavasiliou A, Bardakos NV. Complications of arthroscopic surgery of the hip. Bone Joint Res 2012;1:131–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ayeni OR, Belzile EL, Musahl V, et al. Results of the PeRception of femOroaCetabular impingEment by Surgeons Survey (PROCESS). Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2014;22:906–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin RL. Hip Arthroscopy and Outcome Assessment. Operative Techniques in Orthopaedics 2005;15:290–296. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin RL, Philippon MJ. Evidence of reliability and responsiveness for the hip outcome score. Arthroscopy 2008;24:676–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krych AJ, Thompson M, Knutson Z, Scoon J, Coleman SH. Arthroscopic labral repair versus selective labral debridement in female patients with femoroacetabular impingement: a prospective randomized study. Arthroscopy 2013;29:46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schenker ML, Martin R, Weiland DE, Philippon MJ. Current trends in hip arthroscopy: a review of injury diagnosis, techniques, and outcome scoring. Curr Op Orthop 2005;16:89–94. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Domb BG, Stake CE, Botser IB, Jackson TJ. Surgical dislocation of the hip versus arthroscopic treatment of femoroacetabular impingement: a prospective matched-pair study with average 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy 2013;29:1506–1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reichmann WM, Maillefert JF, Hunter DJ, et al. Responsiveness to change and reliability of measurement of radiographic joint space width in osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011;19:550–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altman RD, Bloch DA, Dougados M, et al. Measurement of structural progression in osteoarthritis of the hip: the Barcelona consensus group. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2004;12:515–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thorborg K, Roos EM, Bartels EM, Petersen J, Hölmich P. Validity, reliability and responsiveness of patient-reported outcome questionnaires when assessing hip and groin disability: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2010;44:1186–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christensen CP, Althausen PL, Mittleman MA, Lee JA, McCarthy JC. The nonarthritic hip score: reliable and validated. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003;406:75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohtadi NG, Griffin DR, Pedersen ME, et al. The development and validation of a self-administered quality-of-life outcome measure for young, active patients with symptomatic hip disease: the International Hip Outcome Tool (iHOT-33). Arthroscopy 2012;28:595–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thorborg K, Hölmich P, Christensen R, Petersen J, Roos EM. The Copenhagen Hip and Groin Outcome Score (HAGOS): development and validation according to the COSMIN checklist. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:478–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Carr A, Murray D. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1996;78-B:185–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, Tölle TR. painDETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin 2006;22:1911–1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jaremko JL, Lambert RG, Zubler V, et al. Methodologies for semiquantitative evaluation of hip osteoarthritis by magnetic resonance imaging: approaches based on the whole organ and focused on active lesions. J Rheumatol 2014;41:359–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.EuroQol Group. EuroQol: a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palmer AJ, Brown CP, McNally EG, et al. Non-invasive imaging of cartilage in early osteoarthritis. Bone Joint J 2013;95-B:738–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lotz M, Martel-Pelletier J, Christiansen C, et al. Value of biomarkers in osteoarthritis: current status and perspectives. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1756–1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allen KD. The value of measuring variability in osteoarthritis pain. J Rheumatol 2007;34:2132–2133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Egerton T, Hinman RS, Takla A, Bennell KL, O'Donnell J. Intraoperative cartilage degeneration predicts outcome 12 months after hip arthroscopy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013;471:593–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sipola P, Niemitukia LH, Hyttinen MM, Arokoski JP. Sample size for prospective studies of hip joint space width narrowing in osteoarthritis by the use of radiographs. Skeletal Radiol 2011;40:431–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maheu E, Cadet C, Marty M, et al. Reproducibility and sensitivity to change of various methods to measure joint space width in osteoarthritis of the hip: a double reading of three different radiographic views taken with a three-year interval. Arthritis Res Ther 2005;7:R1375–R1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]