Schwannomatosis is a neurogenetic syndrome characterized by schwannomas throughout the peripheral nervous system without bilateral vestibular schwannomas (VS) or germline neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2) mutation.1 Management is difficult due to large tumor burden and treatment-resistant pain. Patients require multiple surgical procedures (average of 3.4 per decade) for pain, focal neurologic deficits, or myelopathy.1 There are no known effective drug therapies.

Bevacizumab (BEV; Avastin, Genentech, South San Francisco, CA), the monoclonal antibody to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF-A), has entered investigation for NF2-associated VS with early positive results.2 Preclinical models suggest that schwannomas have angiogenic features and that antiangiogenesis therapy reduces tumor microvascular density in both peripheral and central schwannomas.3 We report successful medical treatment in a patient with progressive, symptomatic schwannomatosis with BEV.

This study provides Class IV evidence that bevacizumab can shrink tumors in a patient with schwannomatosis.

Case report.

A 23-year-old man was diagnosed with schwannomatosis at age 12 years. He had a de novo germline mutation in INI1/SMARCB1 (987-1G>C, splice acceptor exon 8) without germline NF2 mutations as is characteristic of familial schwannomatosis.4 He had 12 surgeries to resect tumors throughout his body due to worsening pain, focal neurologic deficits, or organ compression. In 2009, he required surgery for an enlarging schwannoma at the cervicothoracic junction causing pain and myelopathy. Symptoms initially improved; however, roughly 4 weeks postoperatively, he developed diffuse whole body pain (prior pain had been regional) and urinary incontinence. He then developed bilateral hand weakness, left lower extremity sensory loss, and gait instability. Clinical examination revealed multifocal progressive weakness (upper extremity > lower extremity; 2/5–4/5 motor strength), diffuse dysesthesias, urinary retention, and severe pain refractory to multiple therapies. Extensive MRI evaluation revealed the previously known anatomically unchanged peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Subsequent resection of 2 of tumors compressing the spinal cord confirmed no malignant transformation and yielded no clinical benefit. Infectious and rheumatology evaluations were negative. Superficial radial nerve biopsy revealed moderate to severe acute on chronic neuropathy with abundant, ongoing Wallerian-like degeneration as well as intrafascicular schwannoma. Several courses of oral and IV steroids, plasma exchange, and IV immunoglobulin did not provide clinical improvement. Due to persistent decline in function, he was discharged home with hospice.

Results.

Tumor histology showed schwannoma with almost all cells immunohistochemically positive for INI1 and S100 with pericellular reticulin.5 Genetic analysis of tumor showed deletion of the whole NF2 gene, including flanking regions consistent with somatic rather than germline NF2 mutations and a separate somatic NF2 point mutation (c.1447-12_1447-3DelinsAAG) fulfilling a three/four hit hypothesis.6 Immunohistochemical analysis of tumor revealed increased vascular density (highlighted by CD34 staining) as well as abundant expression of VEGF within the tumor (figure e-1 on the Neurology® Web site at Neurology.org). Staining for EGFR and ErbB2 was negative.

Given the severity and refractory nature of the patient's symptoms and the angiogenic features of his resected schwannoma, he was treated off-label with BEV 10 mg/kg IV every 2 weeks for 6 months followed by 7.5 mg/kg IV every 3 weeks continuously. He was monitored with clinical examination and whole body MRI (WBMRI) preceding and following treatment (figure e-2).

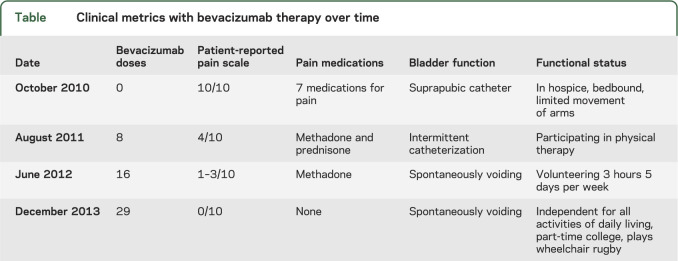

After 10 months of therapy, the patient's pain control improved from a reported 10/10 to 4/10 intensity and he discontinued 5 of 7 pain medications. He had improved lower extremity motor strength, resolution of the dysesthesias, and improved bladder function (table). Hospice was discontinued and he initiated physical medicine and rehabilitation. Radiographically, many (but not all) of the tumors were smaller on WBMRI and had less intense contrast enhancement. After 50 months of BEV therapy, he has had no adverse events and has ongoing clinical improvement with 0/10 reported pain, no use of daily pain medication, and independence with activities of daily living.

Table.

Clinical metrics with bevacizumab therapy over time

Discussion.

VEGF signaling has been implicated in preclinical injury models of neuropathic pain in general and may be linked to schwannoma-associated injury in particular given that VEGF (and its primary receptors VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2) is expressed in many schwannomas.2,3,7 In this patient, tumor VEGF expression was confirmed and treatment with BEV resulted in clinical improvement.

These observations suggest that drug therapy specific to the molecular tumor profile is possible and that antiangiogenic therapy may have efficacy for select patients with schwannomatosis. However, the use of antiangiogenic therapies for schwannomatosis requires caution given the known idiosyncratic risks associated with VEGF inhibitors including thrombosis, hemorrhage, visceral perforations, hypertension, and renal dysfunction. In addition, the experience with NF2-associated VS indicates that continuous active treatment is required for clinical benefit. This could commit patients to long-term exposure to an expensive and potentially harmful drug. Hence, investigation for additional therapies as well as prospective studies to identify the optimal patient population, dose, and schedule for BEV in patients with schwannomatosis is required.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Michael A. Jacobs, Alireza Akhbardeh, and Laura M. Fayad for data collection and analysis.

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

Author contributions: Jaishri O. Blakeley: study design, data collection and interpretation, manuscript drafting and revision. Karisa C. Schreck: data collection and interpretation, manuscript drafting and revision. D. Gareth Evans: data analysis and manuscript editing. Bruce Korf: data analysis and manuscript editing. David Zagzag: data collection and manuscript editing. Matthias A. Karajannis: data analysis and manuscript editing. Amanda L. Bergner: data collection, conceptualization, and manuscript editing. Allan Belzberg: data collection, conceptualization, and manuscript editing.

Study funding: Supported by funding from 3P30CA006973-50S2, U01CA070095, U01CA140204, and 5P30CA016087-33 from the National Cancer Institute.

Disclosure: J. Blakeley reports non-salary research support from GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi, and Lily. K. Schreck, D. Evans, B. Korf, and D. Zagzag report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. M. Karajannis reports non-salary research support from GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis. A. Bergner and A. Belzberg report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

References

- 1.MacCollin M, Chiocca EA, Evans DG, et al. Diagnostic criteria for schwannomatosis. Neurology 2005;64:1838–1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Plotkin SR, Stemmer-Rachamimov AO, Barker FG, II, et al. Hearing improvement after bevacizumab in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2. N Engl J Med 2009;361:358–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong HK, Lahdenranta J, Kamoun WS, et al. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapies as a novel therapeutic approach to treating neurofibromatosis-related tumors. Cancer Res 2010;70:3483–3493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hadfield KD, Newman WG, Bowers NL, et al. Molecular characterisation of SMARCB1 and NF2 in familial and sporadic schwannomatosis. J Med Genet 2008;45:332–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patil S, Perry A, Maccollin M, et al. Immunohistochemical analysis supports a role for INI1/SMARCB1 in hereditary forms of schwannomas, but not in solitary, sporadic schwannomas. Brain Pathol 2008;18:517–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sestini R, Bacci C, Provenzano A, Genuardi M, Papi L. Evidence of a four-hit mechanism involving SMARCB1 and NF2 in schwannomatosis-associated schwannomas. Hum Mutat 2008;29:227–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiguchi N, Kobayashi Y, Kadowaki Y, Fukazawa Y, Saika F, Kishioka S. Vascular endothelial growth factor signaling in injured nerves underlies peripheral sensitization in neuropathic pain. J Neurochem 2013;129:169–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.