Abstract

Objective

To analyze different fluid-fluid level features between benign and malignant bone tumors on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the hospital ethics committee. We retrospectively analyzed 47 patients diagnosed with benign (n = 29) or malignant (n = 18) bone tumors demonstrated by biopsy/surgical resection and who showed the intratumoral fluid-fluid level on pre-surgical MRI. The maximum length of the largest fluid-fluid level and the ratio of the maximum length of the largest fluid-fluid level to the maximum length of a bone tumor in the sagittal plane were investigated for use in distinguishing benign from malignant tumors using the Mann-Whitney U-test and a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. Fluid-fluid level was categorized by quantity (multiple vs. single fluid-fluid level) and by T1-weighted image signal pattern (high/low, low/high, and undifferentiated), and the findings were compared between the benign and malignant groups using the χ2 test.

Results

The ratio of the maximum length of the largest fluid-fluid level to the maximum length of bone tumors in the sagittal plane that allowed statistically significant differentiation between benign and malignant bone tumors had an area under the ROC curve of 0.758 (95% confidence interval, 0.616-0.899). A cutoff value of 41.5% (higher value suggests a benign tumor) had sensitivity of 73% and specificity of 83%.

Conclusion

The ratio of the maximum length of the largest fluid-fluid level to the maximum length of a bone tumor in the sagittal plane may be useful to differentiate benign from malignant bone tumors.

Keywords: Fluid-fluid level, Magnetic resonance imaging, Bone neoplasm

INTRODUCTION

Fluid-fluid levels in bone tumors were initially described as a feature of aneurysmal bone cysts (1, 2). Additional studies reported fluid-fluid levels in a wide range of bone tumors, both benign and malignant, and the presence of a fluid-fluid level is believed to be non-specific to any particular tumor (3, 4, 5, 6).

Several studies have discussed the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to distinguish benign from malignant bone tumors by analyzing fluid-fluid level features (3, 7, 8, 9). Whether fluid-fluid level signal patterns can be a factor to distinguish benign from malignant bone tumors remains controversial (3, 7, 9). Additionally, only one study indicated that the greater the percentage of fluid-fluid level volume within a bone tumor, the greater the likelihood that the tumor was benign (8). However, fluid-fluid level volume measurements are impeded by variations in signal intensities between different fluid-fluid level tumor boundaries, resulting in variable fluid-fluid level volumes.

The aim of this study was to analyze different features of fluid-fluid levels and use MRI features to distinguish benign from malignant bone tumors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Third Hospital of Hebei Medical University with a waiver of informed consent. We evaluated 534 patients with bone tumors demonstrated by biopsy/surgical resection who were referred to the Third Hospital of Hebei Medical University from September 2005 to December 2010. All patients underwent MRI examinations. The patients included 324 women and 210 men with a median age of 35 years (range, 10-65 years) and included 212 (39.7%) benign and 322 (60.3%) malignant tumors. Median age was used in lieu of mean age because the age range was not normally distributed. Age, sex, MRI findings, diagnostic category (benign or malignant tumor), and final diagnosis of the lesion were entered into a database.

Imaging Technique

The MRI examinations were performed with either a Magnetom Symphony (n = 20) or a Magnetom Avanto (n = 29), both of which operated at 1.5 Tesla and were manufactured by Siemens (Erlangen, Germany). Of 47 cases, 26 with sagittal T2-weighted turbo spin-echo (repetition time [TR] = 1650-4200 ms, echo time [TE] = 95-100 ms; echo-train length = 10-15; matrix size = 180-250 x 180-250; slice thickness = 3-4 mm), 21 cases with sagittal short tau inversion recovery (STIR) (inversion time [TI] = 130-150 ms, TR = 4000-4500 ms, TE = 11-26 ms; echo-train length = 8; matrix size = 180-250 x 180-250; slice thickness = 3-4 mm), nine cases with axial T2-weighted turbo spin-echo (TR = 1650-4200 ms, TE = 95-100 ms; echo-train length = 10-15; matrix size = 180-250 x 180-250; slice thickness = 4-5 mm), 38 cases with axial STIR (TI = 130-150 ms, TR = 4000-4500 ms, TE = 11-26 ms; echo-train length = 8; matrix size = 180-250 x 180-250; slice thickness = 4-5 mm), and all cases with sagittal T1-weighted spin-echo (TR = 450-656 ms, TE = 11-13 ms; matrix size = 180-250 x 180-250; slice thickness = 3-4 mm) sequences were available.

Imaging Observations and Analysis

Images for all 534 cases were evaluated retrospectively by four radiologists. Two were experienced musculoskeletal radiologists with 25 years (reader 1) and 23 years (reader 2) experience, and the other two were residents with 3 years (reader 3) and 5 years (reader 4) experience. None of the radiologists had prior knowledge of the lesion histology, and measurements were taken independently. Two criteria were measured by readers 1 and 3 on T2-weighted images: 1) the maximum length of the largest fluid-fluid level and 2) the ratio of the maximum length of the largest fluid-fluid level to maximum length of tumors in the sagittal plane. Additionally, all cases were categorized visually in two ways by readers 2 and 4: 1) by quantity, comparing multiple vs. single fluid-fluid level, and 2) by relative signal intensity of the superior/inferior layer of the fluid-fluid level, with high/low (H/L), low/high (L/H), or no differentiation (ND) signal patterns on T1-weighted images. No differentiation occurred when fluid-fluid level presented on T2-weighted images but not on T1-weighted images.

To assess inter-observer agreement, readers 1 and 3 independently measured the ratio of the maximum length of the largest fluid-fluid level to maximum length of tumors in the sagittal plane using the same procedure. Reader 3 waited 1 month, without knowing the results of the first reading, and independently re-evaluated the ratio of the maximum length of the largest fluid-fluid level to the maximum length of tumors in the sagittal plane, following the procedure used in the first evaluation to determine intra-observer agreement.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 13.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). All measurements were non-normally distributed by the Shapiro-Wilk normality test and expressed as medians and interquartile range. The maximum length of the largest fluid-fluid level and the ratio of the maximum length of the largest fluid-fluid level to the maximum length of a bone tumor in the sagittal plane were investigated to distinguish benign from malignant tumors using the Mann-Whitney U-test and a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. The proportions of benign and malignant tumors in all groups with categorical data were compared using the χ2 test. Fisher's exact method was used when the expected frequency in one or more cells was < 1.

Inter and intraobserver agreement when measuring the ratio of the maximum length of the largest fluid-fluid level to the maximum length of a bone tumor in the sagittal plane was analyzed using the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) interpreted as follows: poor agreement, < 0.40; fair to good agreement, 0.40-0.75; and excellent agreement, ≥ 0.75.

RESULTS

Fluid-Fluid Level Prevalence

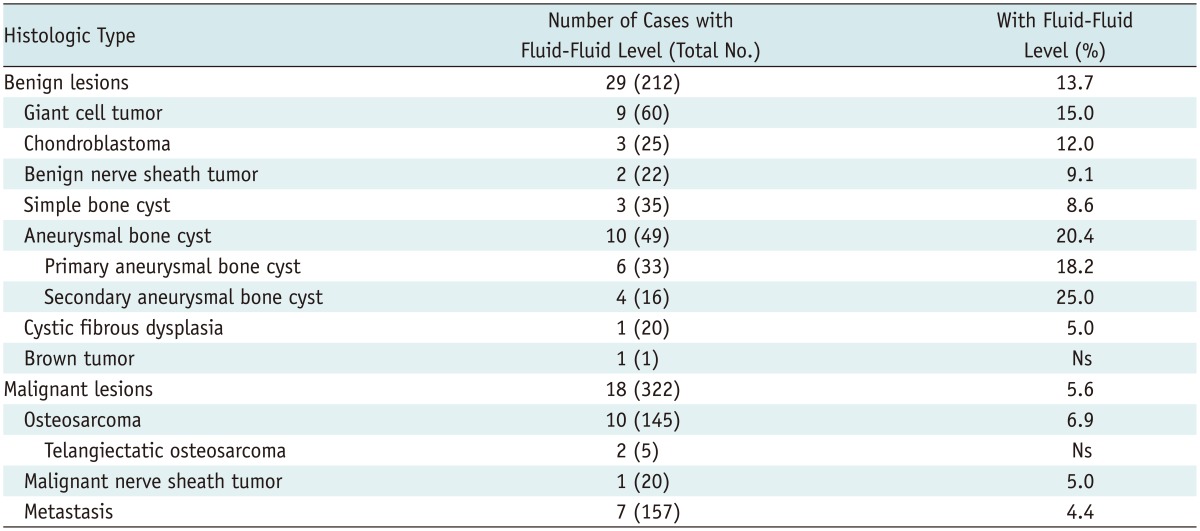

Of the 534 cases, 47 included images containing fluid-fluid levels; a prevalence of 8.8%. Biopsy/surgical resection showed that of these 47 tumors (25 females and 22 males; median age, 27 years; range, 10-65 years), 29 (61.7%) were benign and 18 (38.3%) were malignant. The tumors locations were the femur (n = 16), tibia (n = 15), humerus (n = 6), radius (n = 3), ulna (n = 2), and vertebra (n = 5). As shown in Table 1, 76.6% of the fluid-fluid level cases were osteosarcoma (21.3%), aneurysmal bone cysts (21.3%), giant cell tumors (19.1%), and metastases (14.9%). The remaining 23.4% of the fluid-fluid level case biopsy results were chondroblastoma (6.4%), simple bone cysts (6.4%), benign nerve sheath tumors (4.3%), cystic fibrous dysplasia (2.1%), brown tumors (2.1%), and malignant nerve sheath tumors (2.1%).

Table 1.

Histologic Bone Tumor Types and Proportion of Cases with Fluid-Fluid Levels

Note.- Ns = no significance

Fluid-Fluid Level Features

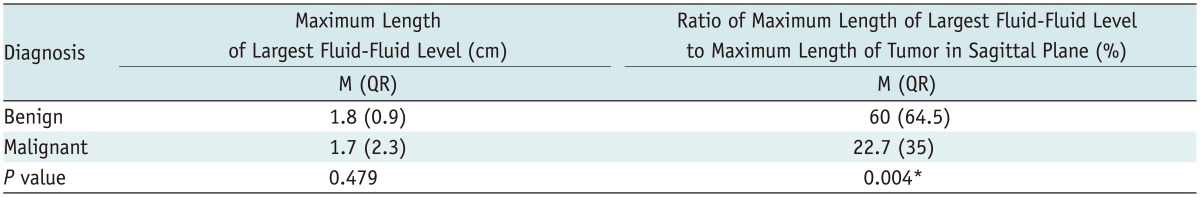

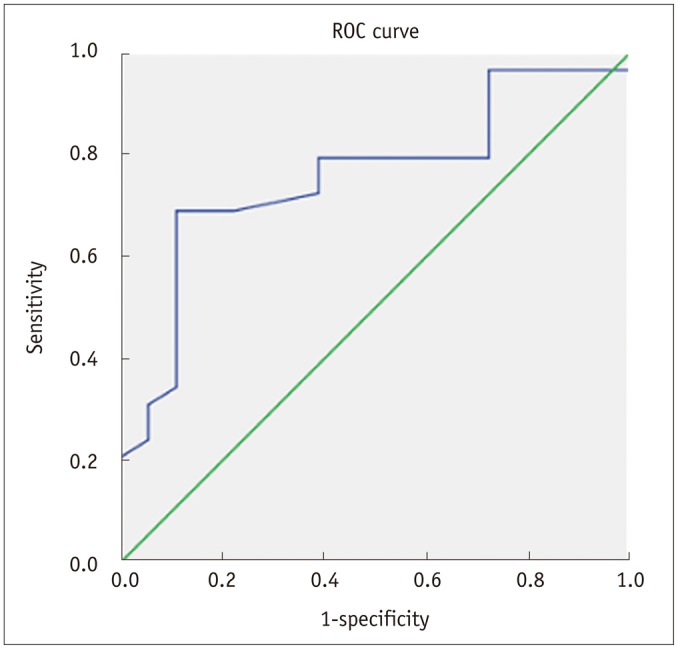

Benign and malignant bone tumors were distinguishable by measuring the ratio of the maximum length of the largest fluid-fluid level to the maximum length of the tumor in the sagittal plane (Table 2). Benign tumors had a significantly higher ratio than that of malignant tumors. The area under the ROC curve value was 0.758 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.616-0.899), and the cutoff value was 41.5% (Fig. 1) (at the point maximizing the sum of sensitivity and specificity). If a bone tumor with a ratio > 41.5% was considered benign, sensitivity was 73% (21 of 29) and specificity was 83% (15 of 18). Positive predictive value was 87.5%, and negative predictive value was 65.2%.

Table 2.

Comparison of Maximum Length of Largest Fluid-Fluid Level and Ratio of Maximum Length of Largest Fluid-Fluid Level to Maximum Length of Tumor in Sagittal Plane between Benign and Malignant Tumors

Note.- *Denotes statistical significance. M = median, QR = interquartile range

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve when ratio of maximum length of largest fluid-fluid level to maximum length of bone tumor in sagittal plane is > 41.5%.

The inter-observer ICC between readers 1 and 3 for measuring the ratio of the maximum length of the largest fluid-fluid level to the maximum length of a tumor in the sagittal plane was 0.851 (95% CI, 0.749-0.914), and the intra-observer ICC between the two reader 3 measurements was 0.838 (95% CI, 0.727-0.907).

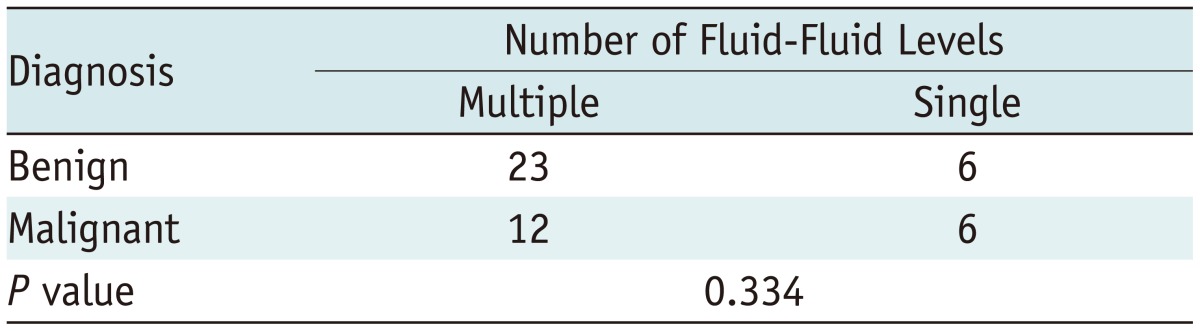

However, comparing the maximum length of the largest fluid-fluid level (Table 2) in the sagittal plane and the number of fluid-fluid levels (Table 3) failed to effectively distinguish between benign and malignant tumors. Thus, these measurements were not as effective as the ratio of the maximum length of the largest fluid-fluid level to the maximum length of a tumor in the sagittal plane.

Table 3.

Number of Fluid-Fluid Levels in Benign and Malignant Bone Tumors

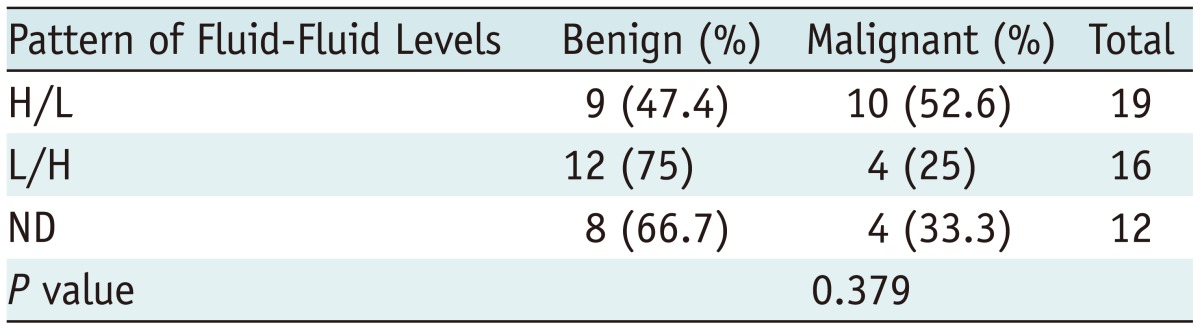

Additionally, all fluid-fluid levels showed an H/L signal pattern on T2-weighted images, whereas all fluid-fluid levels showed a variety of signal patterns on T1-weighted images (Figs. 2, 3, 4). Although the rate of benign bone tumors was higher in the L/H group (75%) than that in the H/L group (47%) and the ND group (67%), it was not significant (Table 4).

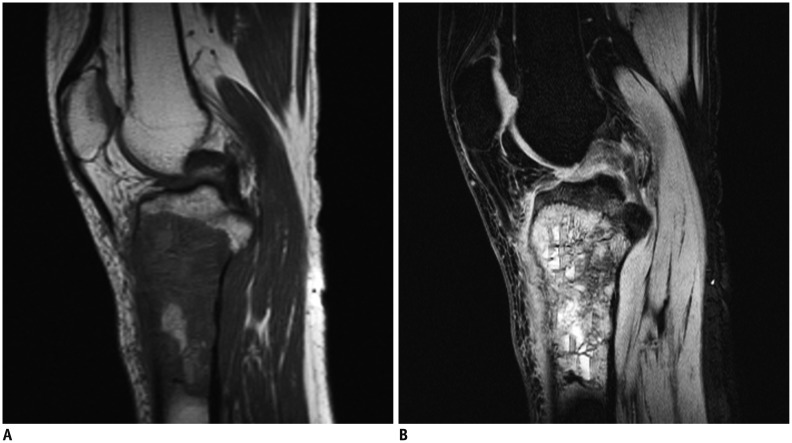

Fig. 2.

Sagittal T1-weighted (A) and short tau inversion recovery (B) magnetic resonance images in 17-year-old male with osteosarcoma of proximal tibia.

Fluid-fluid level cannot be found in A, but multiple fluid-fluid levels can be found in B, and ratio of maximum length of largest fluid-fluid level to maximum length of tumor was 13.8%. Fluid-fluid levels show high/low signal pattern in B.

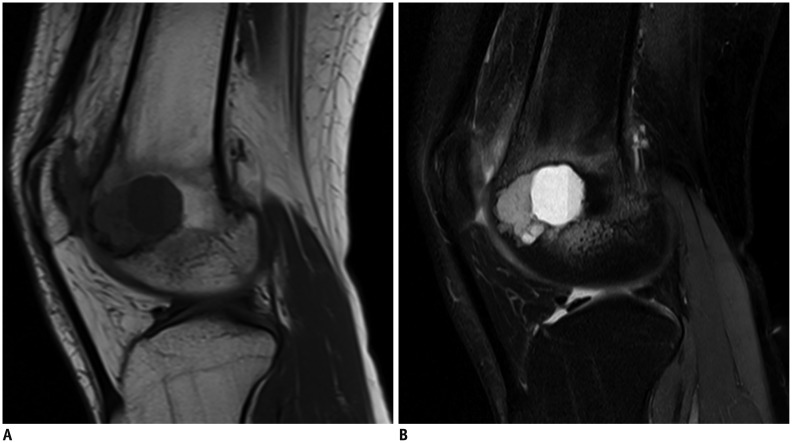

Fig. 3.

Sagittal T1-weighted (A) and short tau inversion recovery (B) magnetic resonance images in 28-year-old male with chondroblastoma of distal femur.

Tumor contained single fluid-fluid level, and ratio of maximum length of largest fluid-fluid level to maximum length of tumor was 81.8%. Fluid-fluid level shows low/high signal pattern in A and high/low in B.

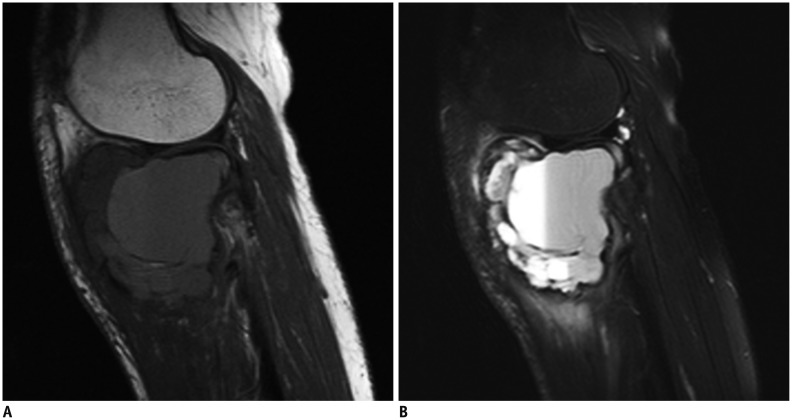

Fig. 4.

Sagittal T1-weighted (A) and short tau inversion recovery (B) magnetic resonance images in 43-year-old woman with aneurysmal bone cyst of proximal tibia.

Lesion contains two fluid-fluid levels, and fluid-fluid levels show high/low signal pattern in A and B. Ratio of maximum length of largest fluid-fluid level to maximum length of lesion was about 61.2%.

Table 4.

Signal Patterns on T1-Weighted Images in Benign and Malignant Bone Tumors

Note.- H/L = high/low, L/H = low/high, ND = no differentiation

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrated that the ratio of maximum length of the largest fluid-fluid level to the maximum length of a tumor in the sagittal plane was significantly higher in benign than that in malignant bone tumors. Visually estimating this ratio can be a useful diagnostic aid when used in conjunction with more traditional diagnostic methods such as analyzing wall thickness, the existence of nodules, and characteristics of the septa on the solid part of the lesion. We found that when tumors with a ratio > 41.5% were considered benign, sensitivity was 73% and specificity was 83%. Therefore, determining the ratio of maximum length of the largest fluid-fluid level to the maximum length of a tumor in the sagittal plane is a valid test to evaluate tumor malignancy on MRI. The exact cause of this size distinction is uncertain; however, it is likely that the variable growth patterns of different tumors play an important role in fluid-fluid level characteristics. Fluid-fluid levels originating from multiple necroses in malignant tumors are usually small in size, whereas primary cavities in benign tumors typically have large fluid-fluid levels (3, 8). This may explain our results.

Although the ROC area was only 0.758, the cutoff value of the ratio was a useful diagnostic aid and can be used in conjunction with the Lodwick classification system based on five descriptive signs (destruction, edge characteristics, penetration of the cortex, sclerotic rim, and expanded shell) (10). If the ratio is > 41.5%, other signs indicating a benign nature, such as geographic destruction, regular or lobulated edge, sclerotic rim, and/or expanded shell, the weighting to diagnose a benign tumor will be increased (10, 11, 12).

O'Donnell and Saifuddin (8) found that the extent of fluid-fluid level within a focal bone lesion is inversely related to the degree of malignancy. The proportion of total lesion volume occupied by the fluid-fluid level was estimated by imaging in all available planes, and the proportion of lesion volume occupied by the fluid-fluid level was categorized as < 1/3, 1/3-2/3, or > 2/3. Of 83 bone tumor cases (50 benign and 33 malignant) with a fluid-fluid level in their series, 28 had a fluid-fluid level that occupied > 2/3 of the whole lesion volume, and 25 were benign. Therefore, if a cutoff value > 2/3 of the tumor volume occupied by the fluid-fluid level was defined as benign, sensitivity would be 50% and specificity would be 90.9%. However, measuring fluid-fluid level and lesion volume is more difficult during a visual reading than measuring tumor and fluid-fluid level length. Therefore, comparing lengths is a more effective and practical technique. In another study related to analyzing fluid-fluid level volumes, Van Dyck et al. (7) reported that fluid-fluid level size characteristics are not correlated with malignancy. In that study, 19 bone tumor cases with a fluid-fluid level were analyzed and 17 cases had tumors that occupied > 50% of the tumor volume. Of these 17, 16 were benign and one was malignant (telangiectatic osteosarcoma). However, those authors did not measure the ratio of maximum length of the largest fluid-fluid level to the maximum length of a tumor in the sagittal plane, so it is uncertain whether the characteristics of this series match the results of our study.

All tumors with a fluid-fluid level had the H/L signal pattern on T2-weighted images/STIR images in our series and in previous studies (3, 7, 9, 13, 14). Fluid-fluid level also showed various signal patterns on T1-weighted images, including L/H, H/L, and ND in this study and in a previous study (9). Although the rate of benign bone tumors was higher in the L/H group (75%) than that in the H/L (47%) and ND groups (67%), we found that the statistical significance was inadequate for diagnosis. However, after analyzing 151 cases with T1-weighted images, Alyas and Saifuddin (9) reported that the L/H signal pattern on T1-weighted images is significantly associated with benign tumors. Our calculated sensitivity and specificity for benign bone tumors with the L/H fluid-fluid level signal pattern was 37.4% and 77.3%, respectively. These observations indicate that fluid-fluid level with the elevated L/H signal pattern suggests a benign bone tumor. However, before the L/H signal pattern of the fluid-fluid level is used as a factor to diagnose benign bone tumors, further study is needed. The other methods we investigated, including the maximum length of the largest fluid-fluid level in the sagittal plane and the number of fluid-fluid levels showed no ability to differentiate between benign and malignant bone tumors.

Furthermore, fluid-fluid level in our series was not found in 12 cases on T1-weighted images despite presenting on T2-weighted or STIR images. No significant difference in the proportion of benign (8/29, 27.6%) and malignant bone tumors (4/18, 22.2%) was observed for T1-weighted images with no fluid-fluid level. This finding disagrees with the results of Alyas and Saifuddin (9), where benign lesions were more likely to have no fluid-fluid level on T1-weighted images compared with malignant lesions. Fluid-fluid level may not present on images when T1-weighted sequence scanning begins a short time after the patient lies down on the table, as it may not allow enough time (10-15 minutes) for the fluid constituents to separate (1, 2, 13). An alternative explanation is that the contrast difference between the constituents of the two layers on T1-weighted images is not as great compared with the difference on T2-weighted or STIR images (9).

An important limitation of this study is that the component of fluid-fluid level was not obtained. Another major limitation is that there may not have been enough time for the fluid constituents to separate before scanning. Additionally, the variable slice thicknesses used in the study may have increased bias. Last, all lesions in this study were located in long and irregular bones (five lesions in irregular and 42 in long bones), whereas none were found in flat or short bones, leading to potential sampling errors.

The presence of fluid-fluid level is not specific for any particular bone tumor, but we found an increased incidence in aneurysmal bone cysts, giant cell tumors, osteosarcoma, and bone metastases. The ratio of the maximum length of the largest fluid-fluid level to the maximum length of a tumor in the sagittal plane may be a useful indicator to distinguish benign from malignant bone tumors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Xiao-Lin Zhang, PhD for her contribution and advice regarding statistical analysis; Steven Louis, MS for their proof reading.

References

- 1.Hudson TM. Fluid levels in aneurysmal bone cysts: a CT feature. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;142:1001–1004. doi: 10.2214/ajr.142.5.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies AM, Cassar-Pullicino VN, Grimer RJ. The incidence and significance of fluid-fluid levels on computed tomography of osseous lesions. Br J Radiol. 1992;65:193–198. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-65-771-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsai JC, Dalinka MK, Fallon MD, Zlatkin MB, Kressel HY. Fluid-fluid level: a nonspecific finding in tumors of bone and soft tissue. Radiology. 1990;175:779–782. doi: 10.1148/radiology.175.3.2160676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burr BA, Resnick D, Syklawer R, Haghighi P. Fluid-fluid levels in a unicameral bone cyst: CT and MR findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1993;17:134–136. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199301000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buetow PC, Newman S, Kransdorf MJ. Giant-cell tumor of the tibia in a child presenting as an expansile metaphyseal lesion with fluid-fluid levels on MR. Magn Reson Imaging. 1990;8:341–344. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(90)90108-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher AJ, Totty WG, Kyriakos M. MR appearance of cystic fibrous dysplasia. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1994;18:315–318. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199403000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Dyck P, Vanhoenacker FM, Vogel J, Venstermans C, Kroon HM, Gielen J, et al. Prevalence, extension and characteristics of fluid-fluid levels in bone and soft tissue tumors. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:2644–2651. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0250-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Donnell P, Saifuddin A. The prevalence and diagnostic significance of fluid-fluid levels in focal lesions of bone. Skeletal Radiol. 2004;33:330–336. doi: 10.1007/s00256-004-0779-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alyas F, Saifuddin A. Fluid-fluid levels in bone neoplasms: variation of T1-weighted signal intensity of the superior to inferior layers--diagnostic significance on magnetic resonance imaging. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:2642–2651. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-1060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lodwick GS, Wilson AJ, Farrell C, Virtama P, Dittrich F. Determining growth rates of focal lesions of bone from radiographs. Radiology. 1980;134:577–583. doi: 10.1148/radiology.134.3.6928321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asaumi J, Konouchi H, Hisatomi M, Matsuzaki H, Shigehara H, Honda Y, et al. MR features of aneurysmal bone cyst of the mandible and characteristics distinguishing it from other lesions. Eur J Radiol. 2003;45:108–112. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(02)00008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung CB, Murphey M, Cho G, Schweitzer M, Hodler J, Haghihi P, et al. Osseous lesions of the pelvis and long tubular bones containing both fat and fluid-like signal intensity: an analysis of 28 patients. Eur J Radiol. 2005;53:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hudson TM, Hamlin DJ, Fitzsimmons JR. Magnetic resonance imaging of fluid levels in an aneurysmal bone cyst and in anticoagulated human blood. Skeletal Radiol. 1985;13:267–270. doi: 10.1007/BF00355347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen BD, Westra WH, Kuhlman JE. Bone metastasis from breast carcinoma with fluid-fluid level. Skeletal Radiol. 1996;25:189–192. doi: 10.1007/s002560050061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]