Abstract

Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) is a major intracellular protein phosphatase that regulates multiple aspects of cell growth and metabolism. Different activities of PP2A and subcellular localization are determined by its regulatory subunits. Here we identified and characterized the functions of two protein phosphatase regulatory subunit homologs, ParA and PabA, in Aspergillus nidulans. Our results demonstrate that ParA localizes to the septum site and that deletion of parA causes hyperseptation, while overexpression of parA abolishes septum formation; this suggests that ParA may function as a negative regulator of septation. In comparison, PabA displays a clear colocalization pattern with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)-stained nuclei, and deletion of pabA induces a remarkable delayed-septation phenotype. Both parA and pabA are required for hyphal growth, conidiation, and self-fertilization, likely to maintain normal levels of PP2A activity. Most interestingly, parA deletion is capable of suppressing septation defects in pabA mutants, suggesting that ParA counteracts PabA during the septation process. In contrast, double mutants of parA and pabA led to synthetic defects in colony growth, indicating that ParA functions synthetically with PabA during hyphal growth. Moreover, unlike the case for PP2A-Par1 and PP2A-Pab1 in yeast (which are negative regulators that inactivate the septation initiation network [SIN]), loss of ParA or PabA fails to suppress defects of temperature-sensitive mutants of the SEPH kinase of the SIN. Thus, our findings support the previously unrealized evidence that the B-family subunits of PP2A have comprehensive functions as partners of heterotrimeric enzyme complexes of PP2A, both spatially and temporally, in A. nidulans.

INTRODUCTION

In recent decades, tremendous progress has been made in understanding serine/threonine protein phosphatase-dependent pathways, which are involved in the regulation of numerous processes, including secretion, cell motility, cell cycle, gene transcription, and cell metabolism (1–7). Serine/threonine phosphorylation, which is regulated by many kinases, can be reversed by a few phosphatases that are targeted to substrates via dozens of regulatory subunits (7, 8). Currently, serine/threonine protein phosphatases (PPs) are grouped into two structurally distinct families: the PPP family (PP1, PP2A, and PP2B) and the PPM family (PP2C and pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase) (9). The PP2A heterotrimeric protein complex, which consists of a cascade of three subunits, namely, a catalytic subunit (C) and a structural subunit (A) associated with a third, hypothetically competitive and variable regulatory subunit (B), represents a highly conserved eukaryotic signal transduction system that is present in many organisms, from yeasts to humans. The activity of PP2A, along with its subcellular localization, is determined by B-family subunits (10–14). In mammals, PP2A is a major intracellular protein phosphatase that regulates multiple aspects of cell growth and metabolism (15). Therefore, PP2A is one of a few serine/threonine-specific phosphatases in the cell, and its complex structure and regulation system guarantee its various functions. The ability of this widely distributed heterotrimeric enzyme to function on a diverse array of substrates is largely controlled by the nature of its regulatory B-family subunits. Thus, multiple isoforms of the B-family regulatory subunit have been isolated from different organisms and grouped into three classes (B, B′, and B″) based on their structural similarities (16, 17). The structural variations between these families support the hypothesis that the B-family regulatory subunit controls enzyme activity and specificity, such that different activities of PP2A and subcellular localization are determined by B-family regulatory subunits. However, one challenge we face is the potential for redundancy in the regulatory subunits' function of assigning PP2A function in mammals (18–20). Therefore, it is difficult to approach the function of PP2A globally by knocking out one of the regulatory subunits. In contrast, simple eukaryotic organisms, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae (budding yeast) and Schizosaccharomyces pombe (fission yeast), which contain only a few isoforms of B-family regulatory subunits, are excellent model systems for studying how B-family regulatory subunits function in regulating PP2A activity. In fission yeast, there is only one B subunit of PP2A-Pab1 and two of the B′-encoding genes (par1 and par2) (21–24). Moreover, mutational studies in fission yeast have demonstrated that B regulatory subunits play crucial roles during the processes of cytokinesis, cell morphogenesis, and cell wall synthesis (25, 26). Similarly, in budding yeast, studies have shown that the B class has only one gene, CDC55, and that the B′ class is encoded by the RTS1 gene alone (25, 27, 28). No homologs were found by using the human B″ type to BLAST search the yeast protein sequence database. In Aspergillus nidulans, according to homology and phenotypic analyses, there are two predicted genes for two PP2A catalytic subunits, designated ppgA (An0164.4) and pphA (An6391.4), which correspond to the S. cerevisiae homologs ppg1 and pph21, respectively. Many studies have verified that the PP2A complex plays important roles during cell communication and differentiation (29–35).

The filamentous fungus A. nidulans is an excellent model organism for studying mitosis and cytokinesis because of its ability to generate septa in hyphal cells such that multinucleate hyphal cells are able to endure septum defects more strongly than are single yeast cells. To date, 28 protein phosphatase catalytic subunit genes have been identified in A. nidulans (36). Among them, a gene for the catalytic subunit of PP2A (pphA) is able to regulate hyphal morphogenesis, and a site-mutated mutant form of pphA (R259/Q) leads to slow growth, delayed germ tube emergence, and mitotic defects at low temperatures (37). However, studies attempting to explicate potential functions of regulatory subunits of PP2A and their relationship with each other remain limited for fungi. In this study, we identified and characterized the functions of the protein phosphatase regulatory subunits encoded by pabA and parA by using systematic molecular approaches. Our results indicate that the B subunit pabA gene and the B′ subunit parA gene for PP2A in A. nidulans play very important roles in morphogenesis, conidiation, and self-fertilization. Moreover, relationships among PabA, ParA, and the septation initiation network (SIN) and between PabA, ParA, and formin SEPA during septation have been analyzed. Our findings support previously unrealized evidence for the function of B-family subunits of PP2A and their own specific regulatory mechanisms in A. nidulans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, culture conditions, and transformation.

A list of A. nidulans strains used in this study is provided in Table S1 in the supplemental material. MM, YAG, YG (YAG without agar), YUU, YUUK, MMGPR, and MMGTPR (MMGPR with 100 mM threonine) media have been described in previous works (38–40). Growth conditions, crosses, and induction conditions for alcA(p)-driven expression were the same as those described previously (41). Expression of tagged genes under the control of the alcA promoter was regulated by different carbon sources, with repression on glucose, derepression on glycerol, and induction on threonine. Standard DNA transformation procedures were used for A. nidulans (42, 43).

Construction of parA and pabA deletion strains.

A strain containing a parA-null mutation was created by double-joint PCR (44). The Aspergillus fumigatus pyrG gene in plasmid pXDRFP4 was used as a selectable nutritional marker for fungal transformation. The linearized DNA fragment 1, which included a sequence of about 725 bp that corresponded to the region immediately upstream of the parA start codon, was amplified with primers 5′ParA-For and 5′ParA-Rev+Tail (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Linearized DNA fragment 2, including a sequence of about 688 bp that corresponded to the region immediately downstream of the parA stop codon, was amplified with primers 3′ParA-For+Tail and 3′ParA-Rev (see Table S2). Lastly, purified linearized DNA fragments 1 and 2 plus the pyrG gene were mixed and used in a fusion PCR with primers Nested-parA5′ and Nested-parA3′. The final, 3,204-bp fusion PCR products were purified and used to transform A. nidulans strain TN02A7. A similar strategy was applied to construct the pabA deletion strain, using primers 5′PabA-For and 5′PabA-Rev+Tail for linearized DNA fragment 1, primers 3′PabA-For+Tail and 3′PabA-Rev for linearized DNA fragment 2, and primers Nest-pabA5′ and Nest-pabA3′ for the fusion product. The final, 3,665-bp 5′-pabA-AfpyrG-pabA-3′ cassette was purified and used to transform A. nidulans strain TN02A7 (see Fig. S1).

Tagging of ParA and PabA with GFP.

To generate an alcA(p)-gfp-parA fusion construct, a 1,192-bp fragment of parA was amplified from TN02A7 genomic DNA by use of primers Rec-parA-5′ (NotI site included) and Rec-parA-3′ (XbaI site included) (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The 1,192-bp amplified DNA fragment was cloned into the corresponding sites of pLB01, yielding pLB-parA 5′ (45). This plasmid was transformed into TN02A7. Homologous recombination of this plasmid into the parA locus should result in an N-terminal green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion with the product of the entire parA gene under the control of the alcA promoter and a fragment of parA under the control of its own promoter. Most transformants displayed identical phenotypes, forming normal colonies under inducing conditions but showing growth defects at 37°C under repressing conditions. One transformant was subjected to diagnostic PCR analysis using a forward primer (GFP-up) designed to recognize the gfp sequence and a reverse primer (ParA-down-3′) designed to recognize the 3′ parA sequence. A similar strategy was used to construct the alcA(p)-gfp-pabA strain.

Immunoblotting experiment and Southern hybridization.

To extract proteins from A. nidulans mycelia, conidial spores from the alcA(p)-gfp-parA, alcA(p)-gfp-pabA, and wild-type (WT) parent control strains were inoculated into MMGPR liquid medium and then shaken at 220 rpm on a rotary shaker at 37°C for 20 h. Tissue was ground in liquid nitrogen with a mortar and pestle and suspended in an ice-cold extraction buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 137 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 1 μl/ml pepstatin A, 1 μl/ml leupeptin). Equal amounts of protein (40 μg) in gel lanes were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE and then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Immobilon-P; Millipore) in 384 mM glycine, 50 mM Tris (pH 8.4), and 20% methanol at 250 mA for 1.5 h. The membrane was then blocked with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5% milk and 0.3% Tween 20. Next, the membrane was probed sequentially with a 1:3,000 dilution of anti-GFP antibody (Roche Applied Science) and goat anti-rabbit IgG–horseradish peroxidase diluted in PBS including 5% milk and 0.3% Tween 20. The blot was developed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham). Other procedures in immunoblotting experiments were carried out as previously described (46). To perform Southern blotting, genomic DNA was digested with EcoRV or BamHI and then separated by electrophoresis and transferred to a nylon membrane (Zeta-probe+; Bio-Rad). The fragment amplified with primers ParA-s-up and ParA-s-down (see Table S2 in the supplemental material) was used as a probe to detect the ΔparA and parent control wild-type strains, respectively. Meanwhile, the fragment amplified with primers PabA-s-up and PabA-s-down (see Table S2) was used as a probe to detect the ΔpabA and parent wild-type strains (see Fig. S1). Labeling and visualization were performed using a digoxigenin (DIG) DNA labeling and detection kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN).

Overexpression of parA and pabA.

To clone the open reading frame (ORF) of the parA gene into the inducible expression plasmid pAL5 (41), a KpnI site was introduced by PCR before the upstream sequence of the first codon and after the downstream sequence of the stop codon, using primers Pal-parA5′ and Pal-parA3′. A 2,389-bp PCR product confirmed by sequence analysis was cut with KpnI and then ligated with a KpnI-cut pAL5 vector to produce the plasmid pAL-parA. This plasmid was transformed into TN02A7. Transformants embedding the entire parA gene under the control of the alcA promoter and another entire parA gene under the control of its own promoter were selected. Overexpression of pabA was carried out in the alcA(p)-gfp-pabA strain ZGB04 under induction conditions with threonine (100 mM). Quantification of overexpression was confirmed by real-time PCR analysis. The plasmids pAL5 and pFNO3, carrying the GFP gene, were purchased from FGSC (http://www.fgsc.net).

Microscopy and image processing.

Several sterile glass coverslips were placed on the bottom of petri dishes and gently overlaid with liquid medium containing conidia. Strains were grown on the coverslips at related temperatures prior to observation under a microscope. The GFP-ParA and GFP-PabA signals were observed in live cells by placing the coverslips on a glass slide. DNA and chitin were stained using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and calcofluor white (CFW) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), respectively, after the cells had been fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Polyscience, Warrington, PA) (47). Differential interference contrast (DIC) images of the cells were collected with a Zeiss Axio Imager A1 microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). These images were then collected and analyzed with a Sensicam QE cooled digital camera system (Cooke Corporation, Germany) with the MetaMorph/MetaFluor combination software package (Universal Imaging, West Chester, PA), and the results were assembled in Adobe Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe, San Jose, CA).

Assay of PP2A activity.

Phosphatase activity was measured using a calcineurin assay kit (Biomol, Plymouth Meeting, PA) (48). Total proteins were extracted from wild-type and related mutant strains grown on YAG for 18 h. PP2A activity was measured as the dephosphorylation rate of a synthetic phosphopeptide substrate (RII peptide) in the presence or absence of 10 mM EGTA buffer. The amount of liberated PO43− was determined colorimetrically. Results were normalized on the basis of the protein concentration in each sample. The differences in PP2A activity between the wild-type, ΔparA, ΔpabA, and ΔparA ΔpabA strains were analyzed by the t test (P values of <0.05 were considered significant). Each activity assay was performed in triplicate. The soluble protein content of the supernatant was determined using a dye-binding assay (49).

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis.

The samples were cultured for 18 h in the relevant media and then were pulverized to a fine powder in the presence of liquid nitrogen. The total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Roche) following the manufacturer's instructions. The samples were treated with DNase I (TaKaRa), and cDNA was generated using an iScript Select cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). Real-time PCR was performed using an ABI one-step fast thermocycler (Applied Biosystems), and the reaction products were detected with SYBR green (TaKaRa). PCR was accomplished by a 10-min denaturation step at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 30 s at 72°C. Transcript levels were calculated by the comparative ΔCT method and normalized against the expression of the tubulin gene in A. nidulans. Primer information is provided in Table S2 in the supplemental material.

RESULTS

Identification and analysis of two PP2A regulatory subunit homologs (B and B′) in A. nidulans.

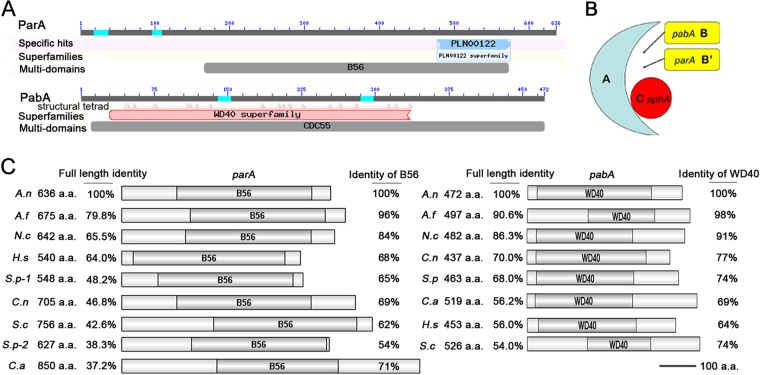

A BLASTp search using the Homo sapiens PP2A-B and PP2A-B′ subunits as queries in the NCBI and CADRE databases produced one result each for putative PP2A regulatory subunit homologs of yeast par1 and pab1 in A. nidulans, which were referred to as pabA (GenBank accession no. AN1545.4 and CADRE accession no. ANIA_01545) and parA (GenBank accession no. AN9467.4 and CADRE accession no. ANIA_09467), respectively. parA encodes a protein with a total length of 636 amino acids (aa), in which a typical conserved PP2A regulatory subunit domain, B56, is included, between aa 166 and 573, by NCBI conserved domain BLASTp analysis. Moreover, we found that ParA shares 48.2% and 38.3% amino acid sequence identities with SpPar1 and SpPar2, respectively. In comparison, PabA is a predicted SpPab1 ortholog in A. nidulans, and PabA shares 68.0% amino acid sequence identity with SpPab1. Theoretically, the pabA gene translates into a 472-amino-acid protein with a WD40 domain located in the region between aa 30 and 378 (Fig. 1A). The same method (BLASTp) was used to search both the structural subunit and the catalytic subunit of PP2A. Consequently, the potential homologs of the catalytic subunit (yeast pphA homolog) and the structural subunit were found to be AN4085.4 and AN6391.4, respectively. Based on information on the PP2A holoenzyme in yeasts and mammals, a putative structural complex of PP2A in A. nidulans was predicted (Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

Bioinformatic analysis of two putative PP2A regulatory subunit (B and B′) homologs in A. nidulans. (A) Schematic diagram of conserved domains of ParA and PabA in A. nidulans. ParA contains a conserved B56 (B′) domain, and PabA includes CDC55 multidomains and a WD40 domain with its superfamilies. (B) Structural model of the PP2A heterotrimeric protein complex. A, structural subunit encoded by AN4085.4; C, catalytic subunit encoded by the PphA gene homolog; B and B′ subunits, variable subunits, i.e., the two PP2A regulatory subunits (the B subunit is encoded by pabA, and the B′ subunit is encoded by parA). (C) Comparison of conserved domain diagrams among the ParA and PabA ortholog protein sequences in selected species. GenBank accession numbers are as follows: A. nidulans ParA, AN9467.4; A. nidulans PabA, AN1545.4; A. fumigatus Par, AFUA_5G02560; A. fumigatus Pab, AFUA_8G05560; N. crassa Par, B18D24.140; N. crassa Pab, NCU09377; gamma isoform of Par from Homo sapiens, PPP2R5C; delta isoform of Pab from Homo sapiens, PPP2R2D; S. pombe Par1p, SPCC188.02; S. pombe Par2p, SPAC6F12.12; S. pombe Pab1, SPAC227.07c; S. cerevisiae RTS1, VL3_4400; S. cerevisiae CDC55, YGL190C; Cryptococcus neoformans Par gamma isoform, CNH02750; C. neoformans Pab, CNF03200; C. albicans Par, CAWG_04383; and C. albicans Pab, CaO19.1468. Abbreviations: a.a., amino acids; A.n, Aspergillus nidulans; A.f, Aspergillus fumigatus; N.c, Neurospora crassa; H.s, Homo sapiens; S.c, Saccharomyces cerevisiae; S.p, Schizosaccharomyces pombe; C.n, Cryptococcus neoformans; C.a, Candida albicans.

Phylogenetic relationships were compared among putative orthologs of ParA and PabA from different fungi. The results suggested that based on full-length alignment, ParA in A. nidulans most closely resembled its counterpart from A. fumigatus, with 79.8% identity, and least resembled its counterpart from Candida albicans, with 37.2% identity. Comparatively, PabA exhibited the highest identity with A. fumigatus (90.6%) and the lowest identity (54.0%) with S. cerevisiae (Fig. 1C). In addition, based on comparisons of conserved domain B56 or WD40, both ParA and PabA orthologs showed highly conserved characterization among the selected fungi, even with orthologs in Homo sapiens, as shown in Fig. 1C.

Deletion and tagging of ParA and PabA.

To gain insight into the functions of ParA and PabA, we made full-length deletion mutants of the parA and pabA genes, respectively. Among many obtained transformants, most displayed identical phenotypes.

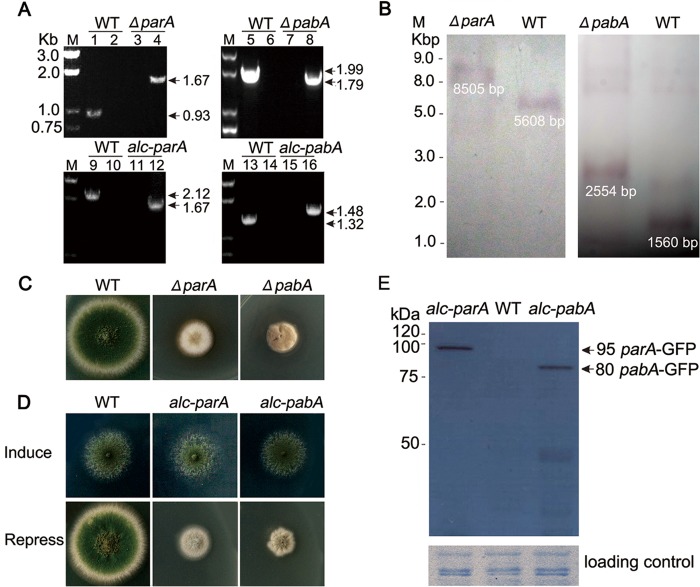

One transformant was subjected to diagnostic PCR analysis and Southern blotting. As shown in Fig. 2A and B, diagnostic PCR analysis and Southern blotting data showed that the parA and pabA genes were successfully replaced by AfpyrG through the DNA homologous replacement approach. We referred to the ΔparA strain as ZGB01 and the ΔpabA strain as ZGB02 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). In addition, backcrossing ZGB01 or ZGB02 with the strain having the pyrG marker demonstrated cosegregation of the colony morphology defects with the pyrG marker, indicating that the parA and pabA genes were successfully replaced by one copy of AfpyrG through the DNA homologous replacement approach. On the rich medium YAG, the colony size of the ΔparA mutant was reduced about 50% compared to that of the wild type, indicating that the loss of parA significantly reduced the vegetative growth rate, as shown in Fig. 2C. In comparison, under the same culture conditions, compared to the wild type, the loss of pabA caused much more severe growth defects than those of the ΔparA mutant, resulting in less than half of the colony size and an irregular colony edge (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 2C, colonies of both the ΔparA and ΔpabA mutants were notably devoid of conidia on agar media.

FIG 2.

Phenotypic characterizations of deletion and conditional mutants. (A) PCR analysis showed that the full-length sequences of parA and pabA (ZGB01 and ZGB02) were deleted in the ΔparA and ΔpabA mutants and that, in conditional strains ZGB03 and ZGB04, the original loci of parA and pabA were replaced by alcA(p)-gfp-parA and alcA(p)-gfp-pabA, respectively. For lanes 1 and 3, the PCR primers were ParA-5′ and ParA-3′ to detect whether parA still existed in the genome, and the expected size was 0.93 kb. For lanes 2 and 4, the PCR primers were ParA-5′ and AfpyrG-3′ to detect whether parA was replaced by the auxotrophy gene AfpyrG in the genome, and the expected size was 1.67 kb. For lanes 5 and 7, the PCR primers were PabA-5′ and PabA-3′ to detect whether pabA still existed in the genome, and the expected size was 1.99 kb. For lanes 6 and 8, the PCR primers were PabA-5′ and AfpyrG-3′ to detect whether there was a homologous recombination to replace pabA with the auxotrophy gene AfpyrG in the genome, and the expected size was 1.79 kb. For lanes 9 and 11, the PCR primers were ParA-up-5′ and ParA-down-3′ to detect whether parA still existed in the genome, and the expected size was 2.12 kb. For lanes 10 and 12, the PCR primers were GFP-up-5′ and ParA-down-3′ to detect whether there was a homologous recombination to replace parA with the auxotrophy gene AfpyrG in the genome, and the expected size was 1.67 kb. For lanes 13 and 15, the PCR primers were PabA-up-5′ and PabA-down-3′ to detect whether pabA still existed in the genome, and the expected size was 1.32 kb. For lanes 14 and 16, the PCR primers were GFP-up and PabA-down-3′ to detect whether there was a homologous recombination to replace pabA with the auxotrophy gene AfpyrG in the genome, and the expected size was 1.48 kb. (B) Identification of homologous recombination by Southern blotting. Only one copy of the AfpyrG selectable marker existed in the chromosome of the ΔparA and ΔpabA mutants. (C) Colony morphologies of wild-type (WT) parent control strain WJA01 and the ΔparA (ZGB01) and ΔpabA (ZGB02) mutants grown on rich medium (YAG) at 37°C for 3 days. (D) Colony phenotypic comparison of the wild type (WJA01) and the alcA(p)-gfp-parA (ZGB03) and alcA(p)-gfp-pabA (ZGB04) conditional strains on derepressing medium (MMGPR) and repressing medium (YAG) at 37°C for 3 days. (E) Western blotting indicated that the GFP-ParA and GFP-PabA fusion proteins were detected by the anti-GFP antibody at the predicted sizes of about 95 and 80 kDa, respectively.

To further confirm and identify the phenotypes caused by parA or pabA deletion, two conditional strains, the alcA(p)-gfp-parA and alcA(p)-gfp-pabA strains, were generated (Fig. 2D), in which the expression of parA or pabA was able to be repressed by glucose on YAG medium, nonrepressed by glycerol on MMGPR, and induced by glycerol plus threonine on MMGTPR. We referred to the alcA(p)-gfp-parA strain as ZGB03 and the alcA(p)-gfp-pabA strain as ZGB04. As shown in Fig. 2A, diagnostic PCR analysis showed that the gene cassettes were integrated into the predicted site in these conditional strains. To further test the functionality of these two conditional strains (ZGB03 and ZGB04), we next inoculated them on nonrepressing medium for 3 days at 37°C. As expected, both the ZGB03 and ZGB04 strains displayed almost normal colony phenotypes compared to the wild-type strain, indicating the functionalities of the GFP-ParA and GFP-PabA fusion proteins. In comparison, when grown on repressing medium (YAG), the two conditional mutants produced tiny, fluffy colony phenotypes, which were consistent with those displayed by the ΔparA and ΔpabA deletion mutants (Fig. 2D). Moreover, by Western blotting, GFP-ParA and GFP-PabA were detected as bands of about 95 and 80 kDa, respectively, by use of anti-GFP antibody under derepressed conditions (Fig. 2E). Because GFP is a 27-kDa protein, this suggests that the molecular masses of ParA and PabA are about 70 and 50 kDa, respectively, which is consistent with the predicted sizes of these two proteins based on protein sequence information. Compared to the case for GFP-tagged strains, the band was completely absent from the control parent wild-type strain, WJA01. Thus, the above data suggest that both ParA and PabA were tagged with GFP at the predicted site in conditional strains ZGB03 [alcA(p)-gfp-parA] and ZGB04 [alcA(p)-gfp-pabA].

ParA and PabA are required for conidiation and self-fertilization.

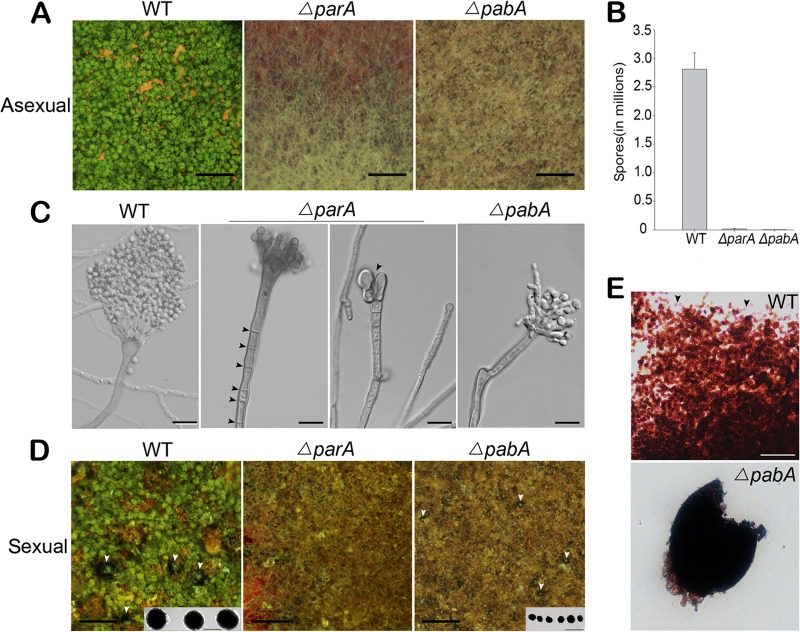

With the aim of understanding the functions of ParA and PabA during conidiation, ΔparA and ΔpabA mutants were analyzed under a dissecting microscope. As shown in Fig. 3A and C, the vegetative mycelia of the control parent strain TN02A7 were capable of developing into conidiophores with visible phialides connected with numerous conidia. In contrast, the ΔparA and ΔpabA mutants had almost completely abolished conidiation. Through quantitative testing, numbers of conidia produced by the ΔparA mutant were approximately 148-fold lower than those of the wild type (2.8 × 107 ± 0.28 × 107 conidia per cm2 for the WT versus 1.9 × 105 ± 0.31 × 105 conidia per cm2 for the ΔparA mutant) on YAG. Moreover, under the same culture conditions as those described above, the ΔpabA mutant showed more severe conidiation defects than those of the parA mutant, resulting in a nearly 772-fold decrease in the number of conidia per cm2 (2.8 × 107 ± 0.28 × 107 conidia per cm2 for the WT versus 3.6 × 104 ± 0.22 × 104 conidia per cm2 for the ΔpabA mutant) relative to that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 3B). To dissect the details of these conidiation defects, the morphology of conidiophores in both mutant and wild-type strains was observed. Occasionally, the parA deletion strain could still develop a few irregular metulae and phialides, but most parA deletion hyphae were unable to form these structures, and even had no normal developed vesicles, as shown in the right panel for the parA deletion strain in Fig. 3C. Interestingly, there were multiple septa in the stalk of the ΔparA mutant, which was not found in the wild-type or ΔpabA strain under the same conditions (Fig. 3C). To further test the ability of the mutant strains to self-fertilize for fruiting body formation, the ΔparA and ΔpabA mutants and their parent strain (TN02A7) were point inoculated onto minimal or rich medium. After cultivation for 2 days at 37°C, all the above-described agar plates were sealed to be induced for sexual development. As a result, deletion of parA did not produce any visible cleistothecia, but the parA deletion strain still developed a few aggregated Hülle cells (Fig. 3D). In comparison, deletion of pabA was able to formed aggregated Hülle cells and produced tiny cleistothecia without any ascospores and asci enclosed (Fig. 3D and E). When the ΔparA or ΔpabA mutant was outcrossed with the wild type, all crosses were able to form normal cleistothecium-containing ascospores with normal viability. These data suggest that both the parA and pabA genes are essential for self-fertilization but not for heterothallic sexual development in A. nidulans.

FIG 3.

ParA and PabA are involved in asexual development and self-fertilization. (A) Conidiation phenotypes of the wild-type (WT) strain TN02A7 and the ΔparA and ΔpabA mutants (ZGB01 and ZGB02), showing that the vegetative mycelia of the parent control strain TN02A7 could be developed into conidiophores with visible phialides connected with numerous conidia, while the ΔparA and ΔpabA mutants had almost completely abolished conidiation. Bars, 10 μm. (B) Quantitative data for numbers of conidia determined using the images in panel A. (C) Conidiophores of the parent control strain and the ΔparA (ZGB01) and ΔpabA (ZGB02) mutants, showing that multiple septa existed in the stalk of the ΔparA mutant. Bars, 10 μm. (D) Comparison of cleistothecium development with and without ascospores during self-fertilization in the wild type and the mutants. The left panel shows that the parent control wild-type strain TN02A7 produced many dark, large cleistothecia near the white Hülle cells (arrows indicate developed cleistothecia). The middle panel displays that there were a few aggregated Hülle cells in the ΔparA mutant, but no detectable cleistothecia, and in the right panel, white arrows indicate small cleistothecia in the ΔpabA mutant under normal sexually induced conditions. (E) Cleistothecia with or without asci in the wild type and the ΔpabA mutant. Bars, 10 μm.

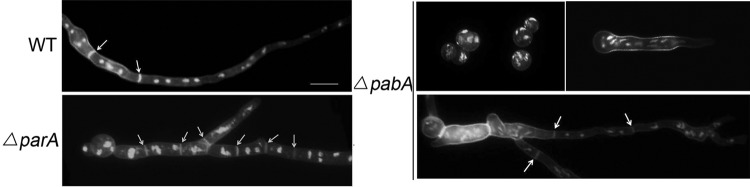

Deletion of parA or pabA results in abnormal distribution of nuclei and septa.

Because previous studies verified that abolished conidiation was induced mostly by the septation defect during cell division (45, 50), we examined the phenotypes of cell division and septation in the ΔparA and ΔpabA mutants. When conidial spores were inoculated into YG liquid medium for 12 h at 37°C and hyphae were stained with DAPI and CFW, the ΔparA mutant showed an irregular shape of abnormal nucleus distribution in both germlings and mature cells. However, in control parent strains, nuclei were distributed normally along hyphal cells (Fig. 4). In comparison, under the same culture conditions, most spores of the ΔpabA mutant failed to germinate and resulted in multiple nuclei localized in the spore, some of which showed very severe growth defects with a lot of fiber-like nucleic structures or DAPI-stained fragments over a prolonged culture time. When the ΔpabA strain was grown in YG at 37°C for 16 h, it germinated very slowly and showed more than 8 nuclei in short germlings, without any sign of septa. However, in the wild type, most germlings formed the first septa after three rounds of mitosis (8 nuclei). This suggested that the pabA mutant had a delayed-septation phenotype. Because the shape of the nucleus in the ΔparA or ΔpabA mutant was so abnormal, it was hard to quantify properly the number of nuclei in hyphal cells of mutants (Fig. 4). Moreover, the ΔparA mutant also displayed an abnormal septum distribution compared to that of the wild type. As a result, the distance between septa in the ΔparA mutant was 13.99 ± 6.37 μm (n = 110), and that in the ΔpabA mutant was 24.26 ± 8.04 μm (n = 120), instead of the distance of 20.91 ± 5.43 μm (n = 110) seen in the wild type for the same length of hyphae. Thus, according to the average distance between septa, we concluded that the ΔparA mutant had a hyperseptation phenotype, whereas the ΔpabA mutant had a delayed-septation defect. This suggests that ParA and PabA may have opposite functions during septation. It is also possible that the septation defects observed in these mutants may be a consequence of the altered morphology.

FIG 4.

Abnormal distributions of nuclei and septa in the ΔparA and ΔpabA mutants. Comparison of septum and nucleus distributions in hyphal cells between the wild-type, ΔparA, and ΔpabA strains. The ΔparA strain was grown in YAG liquid medium at 37°C for 12 h, and the ΔpabA strain was grown for 12 h, 16 h, and 20 h. Nuclei were visualized with DAPI, and septa were stained by calcofluor white. Arrows indicate the locations of septa. Bars, 10 μm.

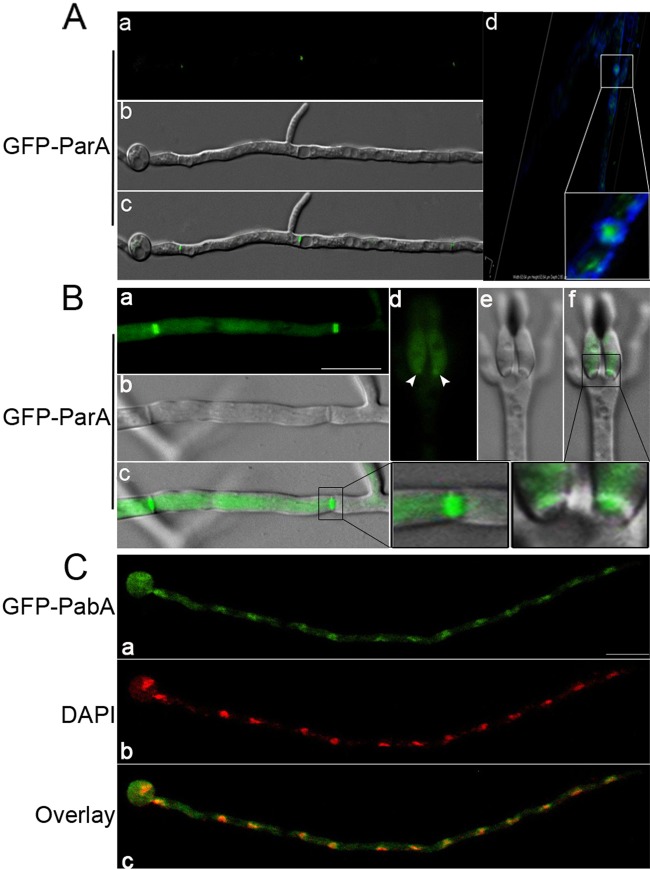

Localization of GFP-ParA and GFP-PabA.

Next, we studied the subcellular locations of ParA and PabA by using live-cell imaging of GFP-ParA and GFP-PabA fusions in two conditional strains and found that, in germlings, GFP-ParA localized mostly to the middle of the septum and then extended to the whole septum in mature cells. Later on, GFP-ParA was able to diffuse to the cytosol or aggregated in some cellular particles in old hyphal cells (Fig. 5A; see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Notably, no detectable signal of GFP-ParA was found prior to the appearance of a CFW-stained septum. To gain insight into the exact location of ParA at the septum, a three-dimensional scanning image was obtained using confocal microscopy (Fig. 5A). The result clearly showed that GFP-ParA localized just right of the center of the septum, inside the area of chitin staining, in germlings. In addition, GFP-ParA also localized to the junction between the vesicle and metulae (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that parA may function not only during septation but also in metula formation. To further confirm the localization of ParA during septation, we made another recombination strain, placing GFP at the C terminus of ParA under the control of the native parA promoter. In contrast to our expectations, although the strain was constructed successfully according to diagnostic PCR assay (see Fig. S3), there were no detectable ParA-GFP signals in this strain. We assume that other interaction proteins or unknown reasons possibly interrupted the GFP signal fused at the C terminus of ParA.

FIG 5.

Localization patterns of GFP-ParA and GFP-PabA. (A) GFP-ParA showed dot-like structures localized near the middle of septum sites (a to c). (d) Three-dimensional scanning image of calcofluor white-stained septa and GFP-ParA, obtained using a confocal microscope. (Inset) Enlarged view of the localization of GFP-ParA inside the area of chitin staining by calcofluor white. (B) GFP-ParA was localized in the entire region of septum sites (a to c) and in junctions between the sites of the vesicle and phialides in mature conidiophores (d to f) in the alcA(p)-gfp-parA conditional strain (ZGB03) under inducing conditions. Arrows indicate GFP-ParA localized to junctions between the vesicle and phialides in the mature conidiophore. (C) GFP-PabA was colocalized with nuclei in the alcA(p)-gfp-pabA conditional strain (ZGB04) under inducing conditions. Bars, 10 μm.

We also checked the localization pattern of GFP-PabA in the alcA(p)-gfp-pabA strain under the same culture conditions as those described above. In this case, the fluorescence of the GFP-PabA fusion was always highly accumulated as spots with nuclei along mature hyphal cells, such that GFP-PabA displayed almost complete colocalization with DAPI staining (Fig. 5C).

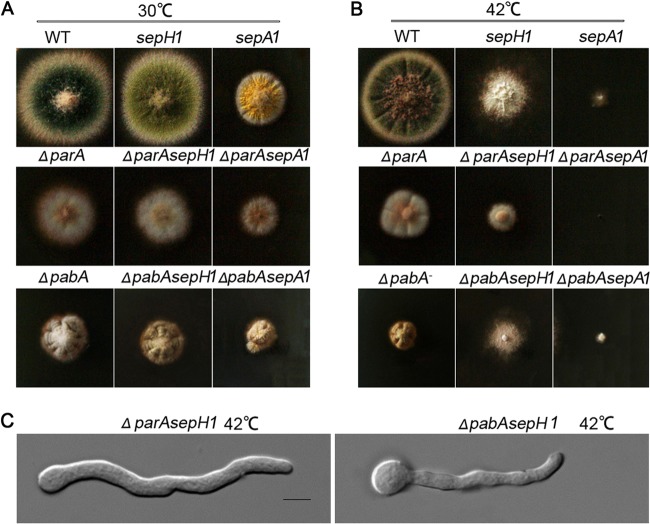

Synthetic defects caused by ΔparA sepH1, ΔpabA sepH1, ΔparA sepA1, and ΔpabA sepA1 double mutants.

Previous studies have verified that the septation initiation network (SIN) is a primary regulatory pathway that controls septation; it includes the serine/threonine protein kinase SEPH, a key component, in both fission yeast and A. nidulans (40, 51). In fission yeast, Pab1 and Par1, as orthologs of PabA and ParA, physically interact with the components of the SIN cascade, and loss of either of them suppresses the defects of SIN mutants (17, 22, 24). Thus, loss of pab1 or par1 is able to rescue the lethality of these SIN mutants in S. pombe. Similarly, SIN kinases may also interact with the PP2A heterotrimeric complex, consisting of PPH1, PP2A-A, and RGB-1, in Neurospora crassa (52, 53). In addition, formin SEPA in A. nidulans is required for the formation of actin rings at septation sites (54, 55). To identify the relationships between PabA/ParA and the SIN and between PabA/ParA and formin SEPA during septation, we generated ΔparA sepH1, ΔparA sepA1, ΔpabA sepH1, and ΔpabA sepA1 double-mutant strains by crossing temperature-sensitive sepH1 and sepA1 mutants with a pabA or parA deletion mutant. According to previous research, sepH1 and sepA1 mutants are temperature-sensitive cytokinesis mutants; when the mutants are cultured at the restrictive temperature of 42°C, sepH and sepA show losses of functionality. In contrast, 30°C is a permissive temperature for these strains (Fig. 6A). As shown in Fig. 6B, after culturing on a rich medium (YUU) at 42°C for 3 days, almost no detectable conidiation was found in all crossed progenies. In addition, the ΔparA sepH1 double mutant had reduced colony sizes with synthetic defects compared to the parent strains; the ΔpabA sepH1 mutant was a little similar to the sepH1 mutant at 42°C (Fig. 6B). Further microscopic studies indicated that both germlings and mature hyphal cells of the ΔparA sepH1 and ΔpabA sepH1 double mutants cultured in liquid medium could not show any clear CFW-stained septa (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Moreover, the ΔparA sepA1 double mutant even caused a synthetic lethal colony phenotype compared to either the sepA1 or ΔparA single mutant. The ΔpabA sepA1 double mutant was a little similar to the sepA mutant. These data indicate that the ΔparA or ΔpabA mutation failed to suppress the defects of the sepH1 or sepA1 mutant, which was totally different from the case in yeasts.

FIG 6.

Synthetic defects caused by ΔparA sepH1, ΔpabA sepH1, ΔparA sepA1, and ΔpabA sepA1 double mutants. (A and B) Colony phenotypes of sepH1 (GQ1) and sepA1 (ASH35) septation mutants and ΔparA sepH1, ΔpabA sepH1, ΔparA sepA1, and ΔpabA sepA1 double mutants grown at permissive (30°C) (A) and restrictive (42°C) (B) temperatures. The ΔparA, ΔpabA, and wild-type WJA01 strains were used as parent strains. (C) Hyphal morphologies of the ΔparA sepH1 and ΔpabA sepH1 mutants grown at a restrictive (42°C) temperature. All strains were cultured on YUU rich medium at 37°C for 8 h. parA and pabA deletion mutants cultured in YUU broth at 37°C for 8 h could not restore septation in the absence of sepH. Bars, 10 μm.

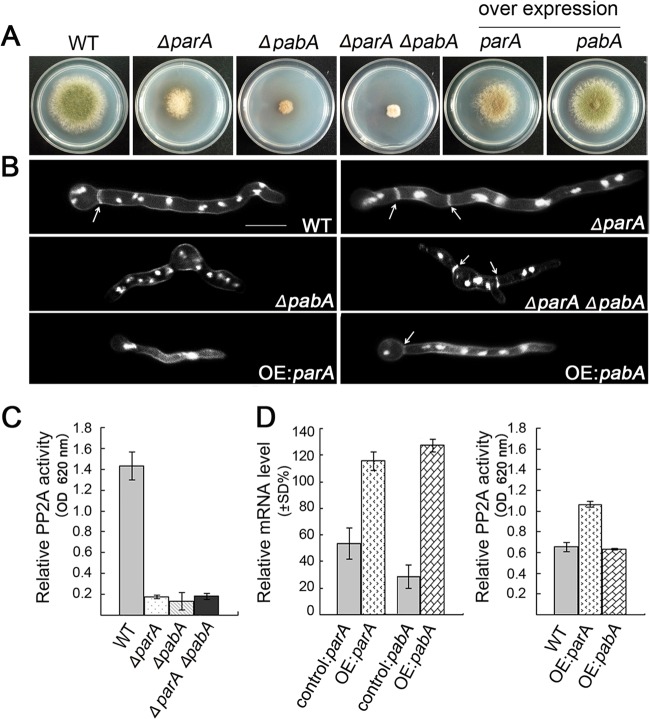

Coordination between parA and pabA and their contributions to PP2A phosphatase activity.

With the aim of exploring the relationship between two regulatory subunits—ParA and PabA—a genetic crossing between the ΔparA and ΔpabA strains (ZGB01 and ZGB02) was carried out as described previously. As a result, compared to the ΔparA or ΔpabA single mutant, the ΔparA ΔpabA double-deletion strain (ZGB09) showed more severe growth defects, with very tiny and needle-like colonies, but did not have the synthetic lethality phenotype; this suggests that ParA and PabA may function synergistically during colony formation (Fig. 7A). A microscopic study showed that both single and double ΔparA and ΔpabA mutants were significantly impaired in the formation of the single axis of hyphal polarity, resulting in more branched hyphae than those seen in the wild type, which had organized, parallel, and defined hyphal filaments. Most surprisingly, when the ΔparA ΔpabA double-deletion mutant (ZGB09) was cultured in liquid medium, germlings and mature hyphal cells showed almost normal septum formation, suggesting that parA deletion was capable of suppressing the septation defect of the pabA mutant (Fig. 7B; see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). This also indicates that parA deletion can bypass the requirement for pabA during septation. Next, we wondered how the overexpression of parA or pabA affects septation and conidiation. In two conditional strains, ZGB03 and ZGB04 (that had been induced on threonine-containing medium [MMGTPR] for 3 days at 37°C) (Fig. 7D), expression of both parA and pabA was increased to some extent as shown by quantitative PCR analysis, indicating that the overexpression of parA and pabA did indeed happen. Next, we checked the colony and septum phenotypes of these strains cultured on the above-mentioned overexpression medium. Consequently, at the point of conidiation, either deletion or overexpression of parA caused a fluffy colony phenotype. However, toward the end of septation, in contrast to the case for parA deletion, overexpression of parA almost completely abolished septum formation in germlings or mycelia, suggesting that parA may work as a negative regulator of septation. To further confirm this phenomenon, we constructed another expression vector, pAL5, in which the entire parA open reading frame was inserted into the alcA promoter vector, and then integrated this vector into the wild-type strain TN02A7 to obtain a new strain, ZGB10, in which there was an extra copy of parA in addition to the original parA gene. Consistent with the above-described data, ZGB10 also showed that overexpression of parA was capable of inactivating septation, resulting in abolished septum formation in hyphal cells. In contrast, under the same culture conditions, overexpression of pabA in strain ZGB04 was unable to induce any detectable abnormal phenotype compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 7A).

FIG 7.

Phenotypic comparisons of parA and pabA deletion and overexpression (OE) strains. (A) Colony morphologies of the parent control strain (WJA01), the ΔparA, ΔpabA, and ΔparA ΔpabA strains, and the conditional strains ZGB03 (parA) and ZGB04 (pabA) cultured on overexpression medium (MMGPRT) at 37°C for 3 days. (B) Hyphal morphologies of the WT (WJA01), ΔparA, ΔpabA, and ΔparA ΔpabA strains cultured on YAG and the parA and pabA overexpression mutants cultured on MMGPRT and stained with calcofluor white (septa) and DAPI (nuclei). All strains were cultured at 37°C for 7.5 h. Arrows indicate the locations of the septa. Bars, 10 μm. (C) Deletion of parA, pabA, or both caused a sharp decrease in PP2A activity. The error bars indicate the standard deviations of results for three independent replicates (t test; P < 0.05). PP2A activity was determined by measuring the dephosphorylation rate of the RII synthetic phosphopeptide substrate, evaluated by determining the optical density at 620 nm (OD 620 nm). (D) PP2A activities in parA (OE:parA) and pabA (OE:pabA) overexpression strains cultured in MMGPRT medium. All mRNA values were normalized to the actin gene.

Genomic information analysis indicated that both the parA and pabA genes encode homologs of PP2A regulatory subunits, which implied that parA and pabA may cause similar defective phenotypes. However, as discussed above, not only did the parA mutation induce a phenotype different from that induced by pabA mutation, but also the localization patterns of ParA and PabA were markedly different. In order to understand why the loss or overexpression of function of these two putative PP2A regulatory subunits would induce different phenotypes, we tested how much of PP2A function would be affected in two different mutants by analyzing PP2A protein phosphatase activity. As described in previous studies for specific detection of PP2A activity (48), an EGTA buffer was utilized to chelate Ca2+ in reaction buffer to remove PP2B (calcineurin) activity, because calcineurin function depends on Ca2+ activation. The results showed that loss of either parA, pabA, or both caused a sharp reduction of the PP2A protein phosphatase activity, such that only 12% ± 1%, 9% ± 8%, and 13% ± 2% of PP2A protein phosphatase activity was left in the ΔparA, ΔpabA, and ΔparA ΔpabA mutants, respectively, compared with the parent control strain, WJA01 (100%) (Fig. 7C). Moreover, overexpression of parA caused a 38% increase of PP2A protein phosphatase activity, but the PP2A activity was almost unchanged in the mutant with overexpressed pabA (Fig. 7D). To verify the method, there were no significant differences among the above-described samples if the substrate peptide was omitted; this indicated that the background phosphoric acid transferase activity was very low and almost the same for extraction buffers from different strains. These data suggest that both ParA and PabA are essential for normal PP2A protein phosphatase activity and that overexpression of ParA, but not PabA, cannot enhance PP2A protein phosphatase activity.

DISCUSSION

Homologs of the B′ and B subunits of PP2A.

PP2A is a heterotrimeric complex that contains a catalytic subunit (C) and a structural subunit (A) associated with a third, hypothetically competitive and variable regulatory subunit (B, B′, or B″). There appears to be a limited quantity of protein serine/threonine phosphatase catalytic subunits, with substrate specificity determined by association with a variety of regulatory and targeted subunits (15). As indicated using comparative genomic analyses of the Homo sapiens PP2A-B and PP2A-B′ subunits via BLAST searches, we reported that A. nidulans has only one ortholog each of the B and B′ subunits. As shown in Fig. 1A, conserved domain analysis indicated that the PP2A-B′ subunit, ParA, contains a B56 domain, which in humans exists as an ∼56-kDa protein family (56), whereas the PP2A-B subunit, PabA, possesses seven repeats of the WD40 domain, ending with Arg-Trp, which mediates protein interaction (57). Meanwhile, the available genome survey revealed that regulatory subunits of PP2A proteins are ubiquitous and relatively conserved in higher eukaryotes, such as single-cell yeasts, filamentous fungi, and mammals. Except for variable fragments in the N and C termini of ParA orthologs, the identities of the B56 domain are very high (ranging from 53% to 96%) among the selected species in this study. Similarly, the seven repeats of the WD40 domain also show very high identities, from 58% to 98%. This indicates that the conserved domains of both ParA and PabA orthologs show a highly conserved characterization.

ParA and PabA are involved in asexual and sexual development.

The model filamentous fungus A. nidulans develops both sexual and asexual spores through complicated regulatory mechanisms. During these reproductive processes, reversible protein phosphorylation is an important regulatory procedure in which protein phosphatases counteract the activities of protein kinases. In this study, we found that colonies of parA and pabA mutants or the conditionally deleted strains showed fluffy, nearly aconidial phenotypes compared to the wild-type strain, which exhibited robustly developed conidia under the same conditions. These data suggest that both putative regulatory subunits (ParA and PabA) are required for the developmental process of conidiation in A. nidulans. Previous studies indicated that in S. pombe, the pab1 mutant of the B regulatory subunit was unable to sporulate normally and also showed defective cell wall synthesis and cytoskeletal component distribution (26). In comparison, inactivation of rgb-1, encoding the Neurospora crassa B regulatory subunit of PP2A, resulted in a low hyphal growth rate and abnormal morphology, but the rgb-1 point mutant was female sterile and could produce abundant amounts of arthroconidia (58). This indicates that mutation of the gene that encodes the B regulatory subunit may not affect all sexual processes. Interestingly, as shown in Fig. 3, our data indicated that deletion of the B′ subunit (parA) or the B subunit (pabA) almost completely abolished self-fertilization, but not heterothallic sexual development, in A. nidulans. This phenomenon raises the question of whether there is any common signaling pathway between asexual and sexual development activation. Several lines of evidence suggest that transcription factors such as SteA, a homeodomain protein carrying two tandem C2H2 zinc finger domains, and NsdD, a putative GATA-type transcription factor carrying a type IVb C2C2 zinc finger, are able to positively regulate both sexual and asexual development (59, 60). Moreover, it has been verified that proteins highly localized on septa and conidiophores or nuclei, such as AnAXL2 (localized in conidiophores), PLKA (localized in the spindle pole body [SPB] and the nucleus), and BudA (localized in septa), may play important roles during asexual and sexual development. Consequently, defects of these proteins produce abnormal nuclear division or septum formation (61–64). Thus, we hypothesize that defects caused by parA and pabA may be due to the reasons for the defects in mitosis and cytokinesis. As shown in Fig. 3C and 4, deletion of parA caused a hyperactivated septation phenotype, especially in the stalk, accompanied by a corresponding delay of nucleus division, which is somewhat similar to the irregular morphologies and distribution of nuclei of the pphA mutant (37). In contrast, pabA deletion induced abnormal division of nuclei, accompanied by delayed septation (Fig. 4). Most interestingly, parA deletion was capable of suppressing the septation defect of the pabA mutant (Fig. 7B), suggesting that ParA counteracts PabA during septation. In contrast, the double mutant of parA and pabA led to a synthetic defect of colony growth, indicating that ParA functions synthetically with PabA during hyphal growth (Fig. 7A).

Relationship between PabA/ParA and the SIN complex.

In fission yeast, the B subunit of phosphatase 2A is a component of the SIN complex, and the loss of pab1 function rescues the lethality of mutants of the etd1, mob1, sid1, and cdc11 genes in the SIN cascade (24). Similarly, the PP2A-B′ regulatory subunit Par1 is also a suppressor of the SIN; loss of par1 rescues defects of cdc11, cdc7, and spg1 mutants but is unable to rescue other SIN mutants (17, 22). PP2A-Pab1- or PP2A-Par1p-mediated dephosphorylation likely inhibits the SIN activity, whereas Cdc11, Cdc7, and Spg1, which act as protein kinases and the GTPase, activate the SIN by phosphorylation, such that they may function antagonistically on the same substrate (65, 66). Cdc11, Cdc7, and Spg1 are positive regulators that activate the SIN during septation and cytokinesis, whereas PP2A-Pab1 and PP2A-Par1 are negative regulators that deactivate the SIN (67). Thus, both scenarios coordinate cell division and nuclear division. However, our genetic analyses showed that the roles played by ParA and PabA in A. nidulans are distinctly different from those played by the other known B′ or B regulatory subunits in yeasts. Our data indicated that the ΔparA sepH1 double mutant had a reduced colony size, with synthetic defects, compared to the parent strains, whereas the ΔpabA sepH1 mutant was similar to the sepH1 mutant cultured at the restrictive temperature of 42°C (Fig. 6B). These data suggest that loss of parA or pabA function is unable to suppress defects of SEPH kinase in the filamentous fungus A. nidulans. There are two potential explanations for this hypothesis. First, the PP2A complex in A. nidulans may have substrates different from SEPH, such that depletion of PP2A could not suppress dysfunction of the SEPH kinase. Second, aside from being a positive regulator of the SIN, PP2A may have multiple essential roles during morphogenesis. As shown in our data in Fig. 7C, deletion of parA, pabA, or parA and pabA sharply decreased PP2A protein phosphatase activity, resulting in only 12% ± 1%, 9% ± 8%, and 13% ± 2% of the PP2A protein phosphatase activity, respectively, remaining in cells of the control strain, WJA01 (100%). Thus, a proper PP2A activity level is required for cell growth. In addition, in S. pombe, almost all par1 or pab1 mutants, which rescue defects of mutants in cdc11, cdc7, and spg1 or of other SIN mutants, are temperature-sensitive mutants, not whole-gene deletions. To further confirm the relationship between PabA/ParA and the SIN during septation and cytokinesis in A. nidulans, we may have to carry out the same approaches, using site-mutated mutants, temperature-sensitive mutants, or conditional strains, to test their function in the near future.

Locations of ParA and PabB and the functions of these proteins.

In higher eukaryotic cells, the B subunits of heterotrimeric PP2A enzymes determine the substrate specificity of the complex in different areas. Therefore, in different organs, there are different modes of phosphatase regulation, enabling it to perform different functions. For example, in mammals, four different families of B subunits have been identified: the B, B′, B″, and B‴ families (16, 17). Each B subunit contains different genes, which are expressed in a tissue-specific manner. For example, the B family is composed of four members of PR55 (α, β, γ, and δ). Among them, PR55α and PR55δ have a widespread tissue distribution, whereas PR55β and PR55γ are highly enriched only in the brain (18–20). In this study, by using GFP-tagged live-cell imaging, we found GFP-ParA located at the center of septa in germlings but extended to whole septum sites in mature hyphal cells. In all eukaryotic organisms, mitotic exit and cell division must be integrated spatially and temporally to facilitate equal division of genetic material between daughter cells (53, 68). In the filamentous fungus A. nidulans, multicellular hyphae are compartmentalized by the formation of septa where assembly of the actomyosin-based cytokinetic ring (CR) and CR constriction occurred (64). The CR protein complex includes structural proteins, molecular motors, and signaling enzymes. The location of ParA in the center of the hyphal septum (probably around the pore) indicates that ParA may be involved in the function of the CR site signaling enzyme to convey activating or inhibitory cues to their targets via posttranslational modifications, such as dephosphorylation (33). In comparison, GFP-PabA fusion fluorescence always accumulates densely as spots with nuclei along mature hyphal cells, suggesting that pabA may play an important role in phosphatase regulation in nuclei, possibly during mitosis in A. nidulans. Although GFP-PabA was not localized to the septum, instead showing a clear nuclear localization, the ΔpabA mutation caused a clear delayed-septation defect. It is likely that PabA mediates dephosphorylation of the SIN activity, while other protein kinases and the GTPase activate the SIN by phosphorylation, such that both scenarios coordinate cell division and nuclear division. Thus, even PabA is not directly localized in the septum but indirectly affects septation. In regard to the localization artifacts due to overexpression, we rechecked the localization pattern under inducing and derepressing conditions. We found that inducing conditions (threonine) caused much stronger signals for GFP-ParA and GFP-PabA than did derepressing conditions (glycerol); however, both proteins consistently displayed similar localization patterns.

In addition, based on the comparative genomic analysis by BLAST searching shown in Fig. 1, there was only one each of the PP2A regulatory subunit (B and B′) orthologs in A. nidulans. Thus, PabA or ParA may have an important comprehensive function as a partner of holoenzyme complexes of PP2A, both spatially and temporally. Furthermore, we found that deletion of either parA or pabA caused a sharp decline in PP2A enzyme activity, suggesting that both ParA and PabA are essential for PP2A protein phosphatase activity and even that, during specific periods, they may have their own specific regulatory functions. The nonessential function of the A. nidulans B subunit is highly unusual compared to the case for the essential PP2A catalytic subunit (36).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants NSFC31370112 and NSFC81330035), the Natural Science Foundation of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions of China (grant 11KJA180005), a Specialized Research Fund for Doctoral Programs of Higher Education (SRFDP) grant (grant 20123207110012) to L. Lu, and a Priority Academic Program Development (PAPD) grant of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions to L. Lu.

A. nidulans strain AJM68 was a gift from Christopher J. Staiger (Purdue University). The sepA1 strain ASH35 was from Steven David Harris (University of Nebraska-Lincoln).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 October 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/EC.00201-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cozzone AJ. 1988. Protein phosphorylation in prokaryotes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 42:97–125. 10.1146/annurev.mi.42.100188.000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stock JB, Ninfa AJ, Stock AM. 1989. Protein phosphorylation and regulation of adaptive responses in bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 53:450–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barford D, Das AK, Egloff MP. 1998. The structure and mechanism of protein phosphatases: insights into catalysis and regulation. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 27:133–164. 10.1146/annurev.biophys.27.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang C, Stewart RC. 1998. The two-component system. Regulation of diverse signaling pathways in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Plant Physiol. 117:723–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallego M, Virshup DM. 2005. Protein serine/threonine phosphatases: life, death, and sleeping. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 17:197–202. 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi YG. 2009. Serine/threonine phosphatases: mechanism through structure. Cell 139:468–484. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foley EA, Maldonado M, Kapoor TM. 2011. Formation of stable attachments between kinetochores and microtubules depends on the B56-PP2A phosphatase. Nat. Cell Biol. 13:1265–1271. 10.1038/ncb2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ubersax JA, Ferrell JE. 2007. Mechanisms of specificity in protein phosphorylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8:530–541. 10.1038/nrm2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barford D. 1996. Molecular mechanisms of the protein serine/threonine phosphatases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 21:407–412. 10.1016/S0968-0004(96)10060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen PT, Brewis ND, Hughes V, Mann DJ. 1990. Protein serine/threonine phosphatases; an expanding family. FEBS Lett. 268:355–359. 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81285-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Millward TA, Zolnierowicz S, Hemmings BA. 1999. Regulation of protein kinase cascades by protein phosphatase 2A. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24:186–191. 10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01375-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Virshup DM. 2000. Protein phosphatase 2A: a panoply of enzymes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 12:180–185. 10.1016/S0955-0674(99)00074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arroyo JD, Hahn WC. 2005. Involvement of PP2A in viral and cellular transformation. Oncogene 24:7746–7755. 10.1038/sj.onc.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu YH, Xing YN, Chen Y, Chao Y, Lin Z, Fan E, Yu JW, Strack S, Jeffrey PD, Shi YG. 2006. Structure of the protein phosphatase 2A holoenzyme. Cell 127:1239–1251. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janssens V, Goris J. 2001. Protein phosphatase 2A: a highly regulated family of serine/threonine phosphatases implicated in cell growth and signalling. Biochem. J. 353:417–439. 10.1042/0264-6021:3530417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guzzo RM, Sevinc S, Salih M, Tuana BS. 2004. A novel isoform of sarcolemmal membrane-associated protein (SLMAP) is a component of the microtubule organizing centre. J. Cell Sci. 117:2271–2281. 10.1242/jcs.01079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson AE, McCollum D, Gould KL. 2012. Polar opposites: fine-tuning cytokinesis through SIN asymmetry. Cytoskeleton 69:686–699. 10.1002/cm.21044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayer RE, Hendrix P, Cron P, Matthies R, Stone SR, Goris J, Merlevede W, Hofsteenge J, Hemmings BA. 1991. Structure of the 55-kDa regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 2A: evidence for a neuronal-specific isoform. Biochemistry 30:3589–3597. 10.1021/bi00229a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zolnierowicz S, Csortos C, Bondor J, Verin A, Mumby MC, DePaoli-Roach AA. 1994. Diversity in the regulatory B-subunits of protein phosphatase 2A: identification of a novel isoform highly expressed in brain. Biochemistry 33:11858–11867. 10.1021/bi00205a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strack S, Chang D, Zaucha JA, Colbran RJ, Wadzinski BE. 1999. Cloning and characterization of B delta, a novel regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 2A. FEBS Lett. 460:462–466. 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)01377-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang W, Hallberg RL. 2000. Isolation and characterization of par1(+) and par2(+): two Schizosaccharomyces pombe genes encoding B′ subunits of protein phosphatase 2A. Genetics 154:1025–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Le Goff X, Buvelot S, Salimova E, Guerry F, Schmidt S, Cueille N, Cano E, Simanis V. 2001. The protein phosphatase 2A B′-regulatory subunit par1p is implicated in regulation of the S-pombe septation initiation network. FEBS Lett. 508:136–142. 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)03047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanabe O, Hirata D, Usui H, Nishito Y, Miyakawa T, Igarashi K, Takeda M. 2001. Fission yeast homologues of the B′ subunit of protein phosphatase 2A: multiple roles in mitotic cell division and functional interaction with calcineurin. Genes Cells 6:455–473. 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lahoz A, Alcaide-Gavilan M, Daga RR, Jimenez J. 2010. Antagonistic roles of PP2A-Pab1 and Etd1 in the control of cytokinesis in fission yeast. Genetics 186:1261–1270. 10.1534/genetics.110.121368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Healy AM, Zolnierowicz S, Stapleton AE, Goebl M, DePaoli-Roach AA, Pringle JR. 1991. CDC55, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene involved in cellular morphogenesis: identification, characterization, and homology to the B subunit of mammalian type 2A protein phosphatase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:5767–5780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kinoshita K, Nemoto T, Nabeshima K, Kondoh H, Niwa H, Yanagida M. 1996. The regulatory subunits of fission yeast protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) affect cell morphogenesis, cell wall synthesis and cytokinesis. Genes Cells 1:29–45. 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.02002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shu Y, Yang H, Hallberg E, Hallberg R. 1997. Molecular genetic analysis of Rts1p, a B′ regulatory subunit of Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein phosphatase 2A. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:3242–3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Queralt E, Lehane C, Novak B, Uhlmann F. 2006. Downregulation of PP2A(Cdc55) phosphatase by separase initiates mitotic exit in budding yeast. Cell 125:719–732. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poggeler S, Kuck U. 2004. A WD40 repeat protein regulates fungal cell differentiation and can be replaced functionally by the mammalian homologue striatin. Eukaryot. Cell 3:232–240. 10.1128/EC.3.1.232-240.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shim WB, Sagaram US, Choi YE, So J, Wilkinson HH, Lee YW. 2006. FSR1 is essential for virulence and female fertility in Fusarium verticillioides and F. graminearum. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 19:725–733. 10.1094/MPMI-19-0725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simonin AR, Rasmussen CG, Yang M, Glass NL. 2010. Genes encoding a striatin-like protein (ham-3) and a forkhead associated protein (ham-4) are required for hyphal fusion in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet. Biol. 47:855–868. 10.1016/j.fgb.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang CL, Shim WB, Shaw BD. 2010. Aspergillus nidulans striatin (StrA) mediates sexual development and localizes to the endoplasmic reticulum. Fungal Genet. Biol. 47:789–799. 10.1016/j.fgb.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh NS, Shao N, McLean JR, Sevugan M, Ren L, Chew TG, Bimbo A, Sharma R, Tang X, Gould KL, Balasubramanian MK. 2011. SIN-inhibitory phosphatase complex promotes Cdc11p dephosphorylation and propagates SIN asymmetry in fission yeast. Curr. Biol. 21:1968–1978. 10.1016/j.cub.2011.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bloemendal S, Bernhards Y, Bartho K, Dettmann A, Voigt O, Teichert I, Seiler S, Wolters DA, Poggeler S, Kuck U. 2012. A homologue of the human STRIPAK complex controls sexual development in fungi. Mol. Microbiol. 84:310–323. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dettmann A, Heilig Y, Ludwig S, Schmitt K, Illgen J, Fleissner A, Valerius O, Seiler S. 2013. HAM-2 and HAM-3 are central for the assembly of the Neurospora STRIPAK complex at the nuclear envelope and regulate nuclear accumulation of the MAP kinase MAK-1 in a MAK-2-dependent manner. Mol. Microbiol. 90:796–812. 10.1111/mmi.12399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Son S, Osmani SA. 2009. Analysis of all protein phosphatase genes in Aspergillus nidulans identifies a new mitotic regulator, fcp1. Eukaryot. Cell 8:573–585. 10.1128/EC.00346-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kosmidou E, Lunness P, Doonan JH. 2001. A type 2A protein phosphatase gene from Aspergillus nidulans is involved in hyphal morphogenesis. Curr. Genet. 39:25–34. 10.1007/s002940000177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kafer E. 1977. Meiotic and mitotic recombination in Aspergillus and its chromosomal aberrations. Adv. Genet. 19:33–131. 10.1016/S0065-2660(08)60245-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang JJ, Hu HQ, Wang S, Shi J, Chen SC, Wei H, Xu XS, Lu L. 2009. The important role of actinin-like protein (AcnA) in cytokinesis and apical dominance of hyphal cells in Aspergillus nidulans. Microbiology 155:2714–2725. 10.1099/mic.0.029215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhong GW, Wei WF, Guan Q, Ma ZF, Wei H, Xu XS, Zhang SZ, Lu L. 2012. Phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate synthetase, as a suppressor of the sepH mutation in Aspergillus nidulans, is required for the proper timing of septation. Mol. Microbiol. 86:894–907. 10.1111/mmi.12026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang G, Lu L, Zhang CY, Singapuri A, Yuan S. 2006. Calmodulin concentrates at the apex of growing hyphae and localizes to the Spitzenkorper in Aspergillus nidulans. Protoplasma 228:159–166. 10.1007/s00709-006-0181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Osmani SA, Pu RT, Morris NR. 1988. Mitotic induction and maintenance by overexpression of a G2-specific gene that encodes a potential protein kinase. Cell 53:237–244. 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90385-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.May GS. 1989. The highly divergent beta-tubulins of Aspergillus nidulans are functionally interchangeable. J. Cell Biol. 109:2267–2274. 10.1083/jcb.109.5.2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu J-H, Hamari Z, Han K-H, Seo J-A, Reyes-Domínguez Y, Scazzocchio C. 2004. Double-joint PCR: a PCR-based molecular tool for gene manipulations in filamentous fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 41:973–981. 10.1016/j.fgb.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu B, Xiang X, Lee YRJ. 2003. The requirement of the LC8 dynein light chain for nuclear migration and septum positioning is temperature dependent in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 47:291–301. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shi J, Chen WW, Liu Q, Chen SC, Hu HQ, Turner G, Lu L. 2008. Depletion of the MobB and CotA complex in Aspergillus nidulans causes defects in polarity maintenance that can be suppressed by the environment stress. Fungal Genet. Biol. 45:1570–1581. 10.1016/j.fgb.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harris SD, Morrell JL, Hamer JE. 1994. Identification and characterization of Aspergillus nidulans mutants defective in cytokinesis. Genetics 136:517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Erental A, Harel A, Yarden O. 2007. Type 2A phosphoprotein phosphatase is required for asexual development and pathogenesis of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 20:944–954. 10.1094/MPMI-20-8-0944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bradford MM. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248–254. 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu B, Morris NR. 2000. A spindle pole body-associated protein, SNAD, affects septation and conidiation in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Gen. Genet. 263:375–387. 10.1007/s004380051181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harris SD. 2001. Septum formation in Aspergillus nidulans. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4:736–739. 10.1016/S1369-5274(01)00276-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heilig Y, Schmitt K, Seiler S. 2013. Phospho-regulation of the Neurospora crassa septation initiation network. PLoS One 8:e79464. 10.1371/journal.pone.0079464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heilig Y, Dettmann A, Mourino-Perez RR, Schmitt K, Valerius O, Seiler S. 2014. Proper actin ring formation and septum constriction requires coordinated regulation of SIN and MOR pathways through the germinal centre kinase MST-1. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004306. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harris SD, Hamer L, Sharpless KE, Hamer JE. 1997. The Aspergillus nidulans sepA gene encodes an FH1/2 protein involved in cytokinesis and the maintenance of cellular polarity. EMBO J. 16:3474–3483. 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharpless KE, Harris SD. 2002. Functional characterization and localization of the Aspergillus nidulans formin SEPA. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:469–479. 10.1091/mbc.01-07-0356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCright B, Virshup DM. 1995. Identification of a new family of protein phosphatase 2A regulatory subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 270:26123–26128. 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smith TF, Gaitatzes C, Saxena K, Neer EJ. 1999. The WD repeat: a common architecture for diverse functions. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24:181–185. 10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01384-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yatzkan E, Yarden O. 1999. The B regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 2A is required for completion of macroconidiation and other developmental processes in Neurospora crassa. Mol. Microbiol. 31:197–209. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vallim MA, Miller KY, Miller BL. 2000. Aspergillus SteA (Sterile12-like) is a homeodomain-C-2/H-2-Zn+2 finger transcription factor required for sexual reproduction. Mol. Microbiol. 36:290–301. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Han KH, Han KY, Yu JH, Chae KS, Jahng KY, Han DM. 2001. The nsdD gene encodes a putative GATA-type transcription factor necessary for sexual development of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 41:299–309. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bachewich C, Masker K, Osmani S. 2005. The polo-like kinase PLKA is required for initiation and progression through mitosis in the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 55:572–587. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Virag A, Harris SD. 2006. Functional characterization of Aspergillus nidulans homologues of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Spa2 and Bud6. Eukaryot. Cell 5:881–895. 10.1128/EC.00036-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mogilevsky K, Glory A, Bachewich C. 2012. The Polo-like kinase PLKA in Aspergillus nidulans is not essential but plays important roles during vegetative growth and development. Eukaryot. Cell 11:194–205. 10.1128/EC.05130-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Si HY, Rittenour WR, Xu KM, Nicksarlian M, Calvo AM, Harris SD. 2012. Morphogenetic and developmental functions of the Aspergillus nidulans homologues of the yeast bud site selection proteins Bud4 and Axl2. Mol. Microbiol. 85:252–270. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rasmussen CG, Glass NL. 2005. A Rho-type GTPase, rho-4, is required for septation in Neurospora crassa. Eukaryot. Cell 4:1913–1925. 10.1128/EC.4.11.1913-1925.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rasmussen CG, Morgenstein RM, Peck S, Glass NL. 2008. Lack of the GTPase RHO-4 in Neurospora crassa causes a reduction in numbers and aberrant stabilization of microtubules at hyphal tips. Fungal Genet. Biol. 45:1027–1039. 10.1016/j.fgb.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Seiler S, Justa-Schuch D. 2010. Conserved components, but distinct mechanisms for the placement and assembly of the cell division machinery in unicellular and filamentous ascomycetes. Mol. Microbiol. 78:1058–1076. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Delgado-Alvarez DL, Bartnicki-Garcia S, Seiler S, Mourino-Perez RR. 2014. Septum development in Neurospora crassa: the septal actomyosin tangle. PLoS One 9:e96744. 10.1371/journal.pone.0096744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.