Abstract

The tyrosine kinase receptor ERBB2 is required for normal development of the heart and is a potent oncogene in breast epithelium. Trastuzumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting ERBB2, improves the survival of breast cancer patients, but cardiac dysfunction is a major side effect of the drug. The molecular mechanisms underlying how ERBB2 regulates cardiac function and why trastuzumab is cardiotoxic remain poorly understood. We show here that ERBB2 hypomorphic mice develop cardiac dysfunction that mimics the side effects observed in patients treated with trastuzumab. We demonstrate that this phenotype is related to the critical role played by ERBB2 in cardiac homeostasis and physiological hypertrophy. Importantly, genetic and therapeutic reduction of ERBB2 activity in mice, as well as ablation of ERBB2 signaling by trastuzumab or siRNAs in human cardiomyocytes, led to the identification of an impaired E2F-1-dependent genetic program critical for the cardiac adaptive stress response. These findings demonstrate the existence of a previously unknown mechanistic link between ERBB2 and E2F-1 transcriptional activity in heart physiology and trastuzumab-induced cardiac dysfunction.

INTRODUCTION

ERBB2 is a transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase that belongs to the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR or ERBB1) family, which also includes ERBB3 and ERBB4. Activation of ERBB family members is associated with multiple cellular functions, including cell growth, differentiation, migration, and survival. Not surprisingly, these receptors have also been shown to be involved in organ development and are implicated in disease initiation and progression (1). Amplification or overexpression of ERBB2 was shown to play an essential role in many types of cancer, particularly in breast cancer, where abnormally high levels of this receptor correlate with a resistance to chemotherapy and poor survival in ca. 20% of all breast cancer patients (2). On the other hand, loss of ERBB2 expression in knockout (KO) mice has deleterious effects on the developing embryo. Notably, ERBB2-deficient animals have aborted development of myocardial trabeculae in the heart ventricle, resulting in embryonic lethality (3).

The critical role of ERBB2 in the adult heart became apparent due to an unforeseen side effect of trastuzumab, a monoclonal antibody against ERBB2 used to treat ERBB2-positive breast cancers. Trastuzumab induced cardiotoxicity in patients manifested as either asymptomatic decreased left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (EF) or symptomatic congestive heart failure (2, 4). Fortunately, the cardiotoxic effects observed are largely reversible (5). The toxicity does not appear to be dose related (5), suggesting that specific targeting of ERBB2 is not cardiotoxic per se but that the receptor has a role in normal heart physiology. In addition, the incidence of trastuzumab's cardiotoxic effects increases when coadministered with drugs inducing cardiotoxic damage such as doxorubicin in combination therapies (2, 4), indicating that ERBB2 might have a role in the response of the heart to physiological stress. The mechanisms underlying why trastuzumab is cardiotoxic and those explaining how ERBB2 regulates adult cardiac function remain controversial and poorly understood. However, the importance of ERBB2 signaling in the postnatal heart was confirmed by independent studies that revealed that cardiac tissue-specific deletion of ERBB2 in mice leads to the early development of severe dilated cardiomyopathy, despite the animals having physiologically normal hearts at birth (6, 7).

In the stressed heart, cardiac adaptation is mediated in part through a cardiac hypertrophic response, which is the adaptive response of the heart to enhanced hemodynamic loads due to either physiological stimuli (e.g., postnatal developmental growth) or pathological states (e.g., drug-induced cardiotoxicity). Physiological hypertrophy involves adaptive cardiac growth and is characterized by normal or enhanced cardiac function (8). In contrast, while pressure overload initially induces physiological hypertrophy (9), sustained hemodynamic overload results in maladaptive (pathological) hypertrophy and is associated with cardiac dysfunction (10).

Taken together, these observations led us to hypothesize that ERBB2 signaling could represent an important mediator of the heart's physiological adaptive response to stress, which is crucial for preserving cardiac function in response to physiological or pathological stimuli and is thus an essential factor for maintaining homeostasis in the adult myocardium. Here, our study demonstrates that ERBB2 is a central integrator of a genetic program responsible for maintaining homeostasis in the adult heart through its ability to modulate E2F-1 expression. Our study thus identifies a novel role for E2F-1 in cardiac physiology and establishes a clear link between ablation of ERBB2, the E2F-1 transcriptional program and the development of trastuzumab-induced cardiac dysfunction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Human primary cardiomyocytes were obtained from Celprogen and maintained according to the manufacturer's instructions. Mouse HL-1 cardiomyocytes were kindly provided by the laboratory of Ron Evans (Salk Institute, San Diego, CA). HL-1 cells were plated in Corning CellBIND culture dishes and grown in Claycomb medium (SAFC Biosciences) supplemented with 100 μM norepinephrin (Sigma), 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma), and 4 mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen). For trastuzumab treatment of human cardiomyocytes, 106 cells were plated in six-well plates for 24 h and then treated for 72 h with 0.1 μg/ml of trastuzumab (Herceptin; Genentech Inc., San Francisco, CA [obtained from a pharmacy) or control antibody (ab18415; Abcam).

siRNA experiments.

Human cardiomyocytes (106 cells) were plated in six-well plates for 24 h and then transfected using HiPerFect (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's protocol (with 50 μl of HiPerfect and 100 μl of Dulbecco modified Eagle medium [DMEM] per well) with 100 nM siE2F-1, 50 nM siERBB2, or the corresponding control small interfering RNA (siRNA; ON-Target-Plus siRNA pool; Dharmacon). For optimal protein knockdown determined by Western blotting, cells were harvested at either 3 days or at 5 to 6 days posttransfection, respectively. All experiments were repeated at least three times independently. For rescue experiments, human cardiomyocytes were plated in six-well plates for 24 h and then treated with 0.1 μg/ml of trastuzumab or the control antibody as previously described. Five minutes posttreatment, the cells were transfected with an E2F-1 expression vector (plasmid 24225, Addgene) or the corresponding control (pCMX empty vector) using Lipofectamine (with 6 μl of Lipofectamine, 3 μg of vector, and 125 μl of DMEM per well) or X-tremeGENE HP DNA transfection reagent (with 6 μl of X-tremeGENE HP, 2 μg of vector, and 200 μl of DMEM per well) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cells were harvested 72 h posttreatment. Alternatively, human cardiomyocytes were transfected with siERBB2 or the control siRNA as described above, and the E2F-1 expression vector was transfected as described above 2 days after siRNA transfections. The cells were harvested at 5 days post-siRNA transfection. The experiments were independently repeated at least three times.

Animals.

Mice were housed and maintained in a pathogen-free housing facility at McGill University. All animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care Committee at McGill University (protocol number 4797) and care of the mice were in accordance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care. The generation of ERBB2 cDNA knock-in (KI) animals was described previously (11). KI animals were derived into a pure FVB genetic background. For doxorubicin treatment, 2-month-old wild-type (WT) or KI mice were randomly assigned to receive doxorubicin (LC Laboratories) at 10 mg/kg diluted in a saline solution or vehicle alone by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection. At 6 days postinjection, cardiac function and morphology were assessed by transthoracic echocardiography. Animals (n = 8 per group) were sacrificed 1 week after injection. The in vivo effects of the 7.16.4 antibody were studied in WT and ERBB2 hypomorphic mice (n = 7 per group). The 7.16.4 and control antibodies were produced in collaboration with the McGill University Goodman Cancer Centre Hybridoma Core Facility. To determine the effect of the anti-ERBB2 antibody treatment on heart function, mice received 7.16.4 (10 μg) diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), a nonspecific isotype-matched IgG, or vehicle alone by i.p. injection. The injections started at birth and were repeated twice a week. Cardiac function and morphology were assessed by echocardiography at the age of 8 weeks as described above. Use of the nonspecific isotype-matched IgG and the vehicle alone yielded comparable results. The animals were sacrificed at 2 months of age. To determine the in vivo effects of doxorubicin and 7.16.4 antibody cotreatment on heart function, 3-month-old WT mice (n = 8 per group) were treated with a single dose of doxorubicin or the vehicle alone (as described above). In addition, daily i.p. treatments with the 7.16.4 antibody (10 μg diluted in PBS) or with a nonspecific isotype-matched IgG were initiated 2 days before doxorubicin administration and repeated until the animals were sacrificed. At 6 or 7 days after the doxorubicin injection, cardiac function and morphology were assessed by transthoracic echocardiography as describe above. Animals were sacrificed 1 day after the transthoracic echocardiography was performed.

Mouse echocardiography.

Mice were lightly anesthetized using 1 to 1.5% isoflurane in oxygen and placed on a heated platform to maintain body temperature. Cardiac function and morphology were assessed by transthoracic echocardiography using a Vevo 2100 high-resolution imaging system with a 40 MHz MS 550D transducer (VisualSonics). Parasternal long-axis projection was used for orientation, and end-systolic internal diameters were determined by using two-dimensional M-mode images of a short axis view at the proximal level of the papillary muscles. The ejection fraction, fractional shortening, wall thickness, and left ventricle mass were calculated by using VisualSonics cardiac measurement software included in the VEVO2100 system, after manual delineation of the endocardial and epicardial borders in the parasternal short-axis cine loop. All measurements were performed at least in quadruplicate. The heart rate of the animals during transthoracic echocardiography is show in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Histology and electron microscopy.

Whole hearts were fixed with 10% formalin followed by paraffin embedding. Serial 5 μM midventricular sections were stained with either hematoxylin and eosin or Masson' trichrome. For electron microscopy, hearts (n = 4 per group) were fixed in 0.01 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde, postfixed in water containing 1% osmium tetroxide and 1.5% potassium ferrocyanide and embedded in Epon. Sections (5 nm) were counterstained with uranyl acetate-lead citrate. Histology and electron microscopy experiments were performed in collaboration with the Goodman Cancer Research Centre Histology Core Facility and the Pharmacology & Therapeutics McGill University Electron Microscopy Facility.

Cell size and fibrosis analyses.

Slides were scanned with an Aperio ScanScope instrument (Aperio Technologies, Inc.) and viewed with Aperio's ImageScope software. Fibrosis and cell size were analyzed using optimized Aperio algorithms (at least five hearts per condition). The mean cardiomyocyte size was confirmed by measurements of 100 cells per specimen.

Expression analysis.

Total RNA was extracted from mouse hearts by using an RNeasy fibrous tissue Midi kit (Qiagen). Alternatively, RNA from treated cultured human cardiomyocytes was isolated by using the Qiagen RNeasy Mini kit. mRNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using Superscript (Invitrogen) and quantified by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) on a LightCycler 480 instrument (Roche) using LightCycler 480 SYBR green I master reagents (Roche). The relative expression was normalized to Rplp0 in tissues and 18S in cells. Primers used for qRT-PCR analyses are show in Tables S2 and S3 in the supplemental material.

Microarray preparation and analyses.

Microarray analyses of 2- and 6-month-old WT and ERBB2 hypomorphic hearts (n = 3) were performed at the McGill University Génome Québec Innovation Centre. Affymetrix MOE430 2.0 Gene-ChIP arrays and FlexArray software (http://genomequebec.mcgill.ca/FlexArray/) were used to identify genes differentially expressed in the hypomorphic mice compared to their WT littermates. A P value threshold of 0.05 and a relative fold change (log2) cutoff of ±0.3 were used, and gene ontology analyses were performed using FatiGO (http://babelomics3.bioinfo.cipf.es or http://babelomics.bioinfo.cipf.es/) as described in reference (12). TransFAT was used to detect overrepresentation of putative transcription factor binding sites in the set of genes tested (13).

Western blot analysis and antibodies.

Mouse heart and human cardiomyocyte total cell lysates were prepared using a modified radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche). Protein was quantified by using a Micro BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific), and Western blotting was performed with the following antibodies: ERBB2 (sc-284; Santa Cruz), E2F-1 (sc-193 or 3742; Cell Signaling), E2F-2 (ab138515; Abcam), E2F-3 (sc-878; Santa Cruz), E2F-7 (AV37583; Sigma-Aldrich), P27 (610241; BD Transduction Laboratories), CDK2 (1134-1; Epitomics), cyclin D1 (sc-246; Santa Cruz), cyclin D2 (sc-166288; Santa Cruz), RB (554136; BD Pharmingen), pRB (3408-1; Epitomics), SKP2 (4315S; Cell Signaling), CDC20 (4823S; Cell Signaling), MNAT1 (sc-135981; Santa Cruz), CDH1 (16368-1-AP; ProteinTech Group), RPLP0 (11290-2-AP; ProteinTech Group), and α-tubulin (CLT9002; Cedarlane). Proteins were detected by chemiluminescence using Lumi-Light Western blotting substrate (Roche).

DNA fragmentation analysis.

A Trevigen's TACS apoptotic DNA laddering kit was used to assay apoptosis in hearts of 6-month-old WT or KI mice. DNA was isolated by using a Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (n = 5 for each group), and 0.5 μg of isolated DNA was loaded onto a 1.5% agarose gel and separated by electrophoresis.

ChIP assays.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed on hearts from 9-week-old WT or KI mice as previously described (14), with slight modifications. Briefly, hearts were isolated and homogenized in cell lysis buffer. Nuclear pellets obtained by centrifugation were resuspended in 1% formaldehyde (J. T. Baker), and DNA-protein cross-linking was allowed to occur at room temperature for 15 min. The nuclei were lysed using nucleus lysis buffer and chromatin DNA was sheared by sonication to an average size of 500 to 1000 bp for regular ChIP and 300 to 500 bp for ChIP-sequencing. Chromatin extract from one heart was incubated overnight with either E2F-1 antibody (05-379; Millipore) or IgG (sc-2025; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) as a negative control. Immune complexes were isolated using 60 μl of prewashed protein G-Dynabeads (Invitrogen). After washing and elution, the protein-DNA complexes were reversed by heating at 65°C for 9 h. Immunoprecipitated DNA was purified by using QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and analyzed by qPCR using a LightCycler 480 instrument. The specificity of the E2F-1 antibody has previously been determined by Western blotting and ChIP (15). Primers used for ChIP studies are show in Table S4 in the supplemental material.

ChIP-sequencing library preparation, sequencing, and analyses.

Thirty-five independent E2F-1 ChIPs were pooled and used as a template for generating an Illumina sequence library. Input DNA was used as a control. Library preparation and sequencing were performed at the Génome Québec Innovation Centre. ChIP-sequencing libraries were prepared using a TruSeq DNA sample preparation kit according to the manufacturer's specifications for gDNA. Libraries were sequenced on a HiSeq 2000 high-throughput sequencer. The ChIP-sequencing data analyses were done in collaboration with the Bioinformatics Department of Genome Québec. Briefly, single-end 50-bp raw fastq reads from the Illumina HiSeq 2000 were filtered using the FASTX toolkit (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/). The filtering steps were as follows: base quality trimming from the 3′ end (phred33 score > 30), sequencing adapter removal, and discarding of sequences <32 bp. Trimmed reads were then aligned to the mouse mm9 genome reference using BWA with default parameters (16). Peaks were called with MACS software using the following parameters: gsize = mm and mfold = 10,15 (17). Gene annotation and motif discovery was performed using the HOMER software with the parameters gsize mm9 and cons–CpG (18). Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA) software (Ingenuity Systems) was used to identify enriched canonical pathways for E2F-1 ChIP-sequencing target genes with binding sites found within 2 kb of the transcriptional start sites of genes.

Statistical analyses.

Bars in the graphical data represent means ± the standard errors of the mean (SEM). The data were compared by using a Student unpaired two-tailed t test, and P values of ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant. FatiGO performs functional enrichment analysis by comparing two lists of genes by means of a Fisher exact test (over-represented terms). In the IPA software, the significance of the association between the data set and the canonical pathway was measured in 2 ways: (i) a ratio of the number of molecules from the data set that map to the canonical pathway is displayed, and (ii) the Fisher exact test was used to calculate a P value determining the probability that the association between the genes in the data set and the canonical pathway is explained by chance alone.

RESULTS

Decreased ERBB2 levels results in impaired cardiac growth during postnatal development in mice.

To further investigate the role of ERBB2 signaling in the adult heart, we used a hypomorphic mouse model (herein also referred to as KI) in which ERBB2 is expressed at only 10% of endogenous levels observed in wild-type (WT) mice (11) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). In contrast to mice harboring cardiac tissue-specific deletion of ERBB2 which develop rapid and severe cardiomyopathy (6, 7), the ERBB2 hypomorphic mice are generally healthy, allowing for the investigation of a physiological situation mimicking the systemic effects of long-term reduction in ERBB2 signaling.

First, the impact of reduced ERBB2 levels on the cardiac adaptive stress response was investigated using postnatal cardiac growth as the stimulus for physiologic cardiac hypertrophy, which is primarily achieved through increased myocyte size. At birth, no phenotypic cardiac differences between WT and ERBB2 hypomorphic mice were observed, as determined by histological analyses, heart mass, and cell size (Fig. 1). However, heart-to-body-weight ratios and left ventricular myocyte size were significantly reduced in 2- and 4-month-old hypomorphic mice (Fig. 1) (n = 5 mice per group). These results are consistent with an impaired physiological adaptive response to enhanced hemodynamic load demand during postnatal development growth and suggest that the reduced capacity for hypertrophic growth observed in ERBB2 KI hearts can be attributed to the blunted ability of individual cardiomyocytes to grow in size.

FIG 1.

Loss of ERBB2 signaling results in impaired cardiac growth during postnatal development. (A) Representative midventricular heart cross sections of WT and ERBB2 KI mice at day 1, 2, 4, and 6 months of age. Scale bar, 1 mm. (B) Indexed heart mass to body weight ratios at birth (day 1) and at 2, 4, and 6 months of age in WT and KI mice. Bars represent means ± the SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. (C) Representative hematoxylin and eosin staining of left ventricular myocardium sections from WT and KI mice. Scale bar, 50 μm. (D) Quantification of cardiomyocyte size in WT and KI mice at 1 day and 2, 4, and 6 months of age. Bars represent means ± the SEM. n = 5 mice per group. *, P < 0.05.

Given that lack of physiological adaptation to pressure overload results in the development of maladaptive hypertrophy (8–10), we inferred that the impaired physiological hypertrophy observed in the ERBB2 hypomorphic hearts could give rise to the development of pathological hypertrophy in the aging animals. Indeed, heart-to-body-weight ratios and left ventricular myocyte size were markedly increased in these mice compared to WT at 6 months of age (Fig. 1) (n = 5 mice per group).

Cardiac dysfunction in aging ERBB2 hypomorphic mice.

Since pathological hypertrophy is associated with cardiac dysfunction (8–10), we next sought to characterize heart function in the ERBB2 KI animals. Monitoring by ultrasound echocardiography revealed no functional differences between WT and KI mice at 2 months of age (Fig. 2A to C). However, we observed progressive malfunction of the heart in aging ERBB2 hypomorphic mice exhibited by a significant decline in both left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and left ventricular fractional shortening (LVFS), indicating LV systolic impairment (Fig. 2A to C) (n = 8 mice per group). In agreement with the histological analyses (Fig. 1), the KI mice developed pathological cardiac hypertrophy by 6 months of age, as demonstrated by a significant increase in both LV mass and LV internal diameter (Fig. 2D and E) (n = 8 mice per group). Overall, these results suggest that impaired physiological hypertrophy is the leading cause of the development of pathological hypertrophy and cardiac dysfunction in the ERBB2 hypomorphic mice.

FIG 2.

Cardiac dysfunction in ERBB2 hypomorphic hearts. (A) Representative M-mode echocardiographic images from WT and ERBB2 KI mice at 2, 4, or 6 months of age. (B) Percentages of LVEF in WT and KI hearts at the indicated time points. Values represent means ± the SEM. n = 8 mice per group. **, P < 0.01. (C) Percentages of LVFS in WT and KI hearts at the indicated time points. Values represent means ± the SEM. n = 8 mice per group. **, P < 0.01. (D) Increased LV mass index to body weight (LV/BW) in 6-month-old KI mice compared to WT mice. Bars represent means ± the SEM. n = 8 mice per group. *, P < 0.05. (E) Echo-derived LV internal systolic chamber diameter in 6-month-old KI mice compared to WT. Bars represent means ± the SEM. n = 8 mice per group. *, P < 0.05. (F) Illustration of the number of upregulated and downregulated genes from microarray expression analysis of 6-month-old KI hearts versus WT hearts. n = 3 mice per group. (G) Enrichment analysis of GO terms and KEGG pathways using FatiGO of the 2,141 differently regulated genes in the 6-month-old KI hearts compared to WT mice. (H) Representative Masson's trichrome staining shows increased fibrosis (in blue) in 6-month-old KI mice relative to WT mice. Scale bars: 50 and 30 μm. (I) Hearts of 6-month-old KI mice have increased (∼20%) fibrosis compared to WT littermates. Bars represent means ± the SEM. n = 5 mice per group. *, P < 0.05. (J) Representative agarose gel showing heart DNA laddering from 6-month-old WT and KI mice. MW, molecular weight marker. (K) Transmission electron microscopy performed on heart sections from WT and KI mice at 6 months are shown. Pleomorphic mitochondria (M) and a larger number of vacuoles (arrows) in KI (right) hearts are found compared to control mice (left). Scale bar: 2 μm.

We next performed gene expression profiling studies on 6-month-old WT and ERBB2 hypomorphic hearts to further elucidate the cardiac dysfunction observed (see Table S5 in the supplemental material) (n = 3 mice per group). Functional analysis of the differentially regulated genes obtained using FatiGO revealed altered KEGG pathways associated with hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy, as well as cardiac muscle contraction (Fig. 2F and G; see also Table S6 in the supplemental material). In addition, numerous genes involved in muscle homeostasis (e.g., Srf and Yy1) and the adaptive response to stress (e.g., Fgf2 and Vegfa) were found modulated in ERBB2 KI hearts (Fig. 2G; also see Table S6 in the supplemental material). The data reinforce our initial hypothesis that ERBB2 signaling could represent an important pathway involved in the heart's physiological adaptive response to stress. Further functional analysis of the gene expression data set by IPA software identified a strong enrichment of genes associated with cardiac fibrosis in the ERBB2 hypomorphic hearts (see Table S7 in the supplemental material). In agreement, Masson's trichrome staining of cardiac sections revealed significantly more fibrosis in the ERBB2 KI mice compared to WT mice (Fig. 2H and I) (n = 5 mice per group).

Since no difference in apoptotic DNA fragmentation was observed between 6-month-old WT and ERBB2 hypomorphic hearts, apoptosis is not a likely determinant in the development of cardiac dysfunction in the KI animals (Fig. 2J). Furthermore, transmission electron microscopy revealed a higher number of vacuoles and pleomorphic mitochondria in ERBB2 KI hearts (Fig. 2K) (n = 4 mice per group) that is consistent with the endomyocardial ultrastructural features observed in patients who experienced trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity (19). Collectively, these results illustrate that the presence of physiological levels of ERBB2 in the adult myocardium is necessary to maintain normal cardiac function and that the ERBB2 hypomorphic mice develop cardiac dysfunction closely resembling that seen in humans administered trastuzumab (2, 19).

ERBB2 KI mice are more susceptible to doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity.

We next investigated whether reduced levels of ERBB2 in the KI model can affect the susceptibility of the heart to the cardiotoxic effects of cytotoxic agents. To this end, KI and WT mice were given a single injection of 10 mg/kg doxorubicin or vehicle alone (n = 8 mice per group). Saline-injected WT and KI mice were found to have similar cardiac functions as determined by ultrasound echocardiography (Fig. 3). In contrast, doxorubicin treatment resulted in decreased LV function and left ventricular enlargement in WT mice (Fig. 3). The observed cardiotoxic effect of doxorubicin was amplified in KI animals, indicating that suppression of ERBB2 signaling sensitizes mice to doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy.

FIG 3.

Effect of doxorubicin treatment on cardiac function of WT and ERBB2 hypomorphic mice. (A) Representative M-mode echocardiographic images from 2-month-old WT and ERBB2 KI mice treated with doxorubicin (10 mg/kg) or saline solution as control (vehicle). (B) Percentages of LVEF in treated WT and KI animals. Bars represent means ± the SEM. n = 8 mice per group. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (C) Percentages of LVFS in treated WT and KI animals. Bars represent means ± the SEM. n = 8 mice per group. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (D) Echo-derived LV internal systolic chamber diameter in treated WT and KI animals. Bars represent means ± the SEM. n = 8 mice per group. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

ERBB2 deficiency alters E2F-1 target gene expression.

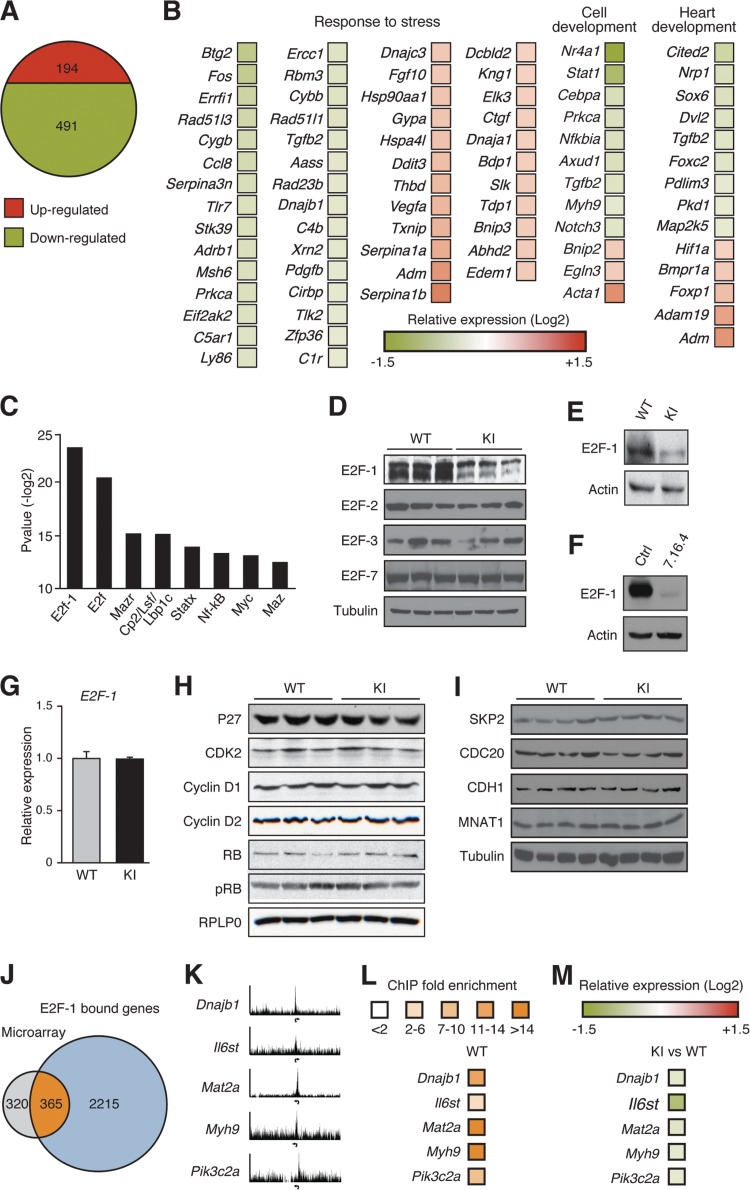

To identify an ERBB2-dependent molecular signature critical in maintaining adult cardiac homeostasis, gene expression profiling studies were performed on 2-month-old WT and ERBB2 KI hearts (see Table S8 in the supplemental material) (n = 3 mice per group). As described earlier, KI mice at this age display an impaired physiological adaptation to hemodynamic load (blunted heart size) without any signs of cardiac dysfunction (impaired LV function). Gene expression analysis identified 491 downregulated and 194 upregulated genes in the ERBB2 hypomorphic hearts compared to WT (Fig. 4A). Functional analysis of the data set using FatiGO revealed a significant number of genes associated with cardiovascular development and function, as well as the adaptive response to stress (Fig. 4B; also see Table S9 in the supplemental material).

FIG 4.

Loss of ERBB2 signaling inhibits the cardiac adaptive stress response at a molecular level. (A) Illustration of the number of upregulated and downregulated genes from microarray expression analysis of 2-month-old ERBB2 KI hearts versus WT. n = 3 mice per group. (B) Heat map representation of a subset of key genes involved in cardiovascular development and response to stress in KI hearts relative to WT mice. Expression data are shown as the relative fold change. (C) Top eight enriched transcription factor binding motifs from TransFAT analysis of the 685 differently regulated genes in KI hearts compared to WT mice. (D) Western blot analysis of E2F family member expression in cardiac extracts from 2-month-old WT and KI mice. (E) Western blot analysis of E2F-1 in cardiac extracts from 6-month-old WT and KI mice. (F) Western blot analysis of ERBB2 and E2F-1 in 7.16.4-treated mouse HL-1 cardiomyocytes. (G) Cardiac qRT-PCR analysis of E2F-1 in 2-month-old KI and WT animals. (H) Western blot analysis of factors involved in the regulation of E2F-1 activity. No differences in total heart protein levels of p27, CDK2, cyclin D1, cyclin D2, RB, and phospho-RB (pRB) were found between 2-month-old WT and KI mice. (I) Western blot analysis of E3-ubiquitin ligase proteins for which E2F-1 has been shown to be a substrate in cardiac extracts from 2-month-old animals. (J) Venn diagram illustrating the overlap between E2F-1 ChIP-sequencing target genes and differentially regulated genes in KI hearts relative to WT. (K) ChIP-sequencing enrichment ratio profiles for E2F-1 at transcriptional start sites of genes encoding diverse proteins implicated in cardiac function. Arrows indicate the transcriptional start sites for each gene. (L) Standard ChIP validation in WT mice. (M) Relative fold expression levels between ERBB2 KI and WT hearts of the same subset of genes shown in panel L.

To further investigate the transcriptional pathways altered in the ERBB2 hypomorphic hearts, we sought to identify enriched transcription factor binding sites present in the promoters of the altered genes. This analysis identified the consensus motifs for E2F-1/E2F as the most significantly enriched binding elements (Fig. 4C; also see Table S10 in the supplemental material). E2F-1 but not other E2F family members (E2F-2, E2F-3, and E2F-7) known to play a role in cardiac development and function (20–22) was markedly decreased in ERBB2 KI hearts compared to WT hearts (Fig. 4D). The reduction of E2F-1 protein levels was also observed in 6-month-old KI animals (Fig. 4E). In addition, inhibition of ERBB2 signaling in HL-1 mouse cardiomyocytes by the specific ERBB2 monoclonal antibody 7.16.4 also led to a significant reduction in E2F-1 protein abundance (Fig. 4F). Interestingly, no difference in E2F-1 transcript levels was found between WT and KI hearts (Fig. 4G). Moreover, the protein levels of known upstream regulators of E2F-1 activity (Fig. 4H) and E3 ubiquitin ligases known to target E2F-1 for degradation (Fig. 4I) were unchanged in the ERBB2 KI hearts. Although the molecular mechanism by which ERBB2 signaling impacts E2F-1 expression in the heart remains to be elucidated, our data exclude several factors that could play a role in this process.

To further support the role played by E2F-1 in the ERBB2 hypomorphic heart, ChIP-sequencing was performed to identify direct cardiac E2F-1 target genes differentially regulated in the KI mice. Of the 3,592 E2F-1 enriched peaks, more than 80% (2,987) of the sites corresponding to 2,922 unique genes were found within ±2 kb of the transcriptional start sites of genes (Fig. 4J; also see Table S11 in the supplemental material). Functional analysis of these genes revealed a strong enrichment for canonical pathways linked to (i) cardiovascular development and function, (ii) cellular growth, proliferation, and development, (iii) cardiac hypertrophy, (iv) cardiovascular homeostasis and response to stress, (v) energy and metabolism, and (vi) antioxidant systems (see Table S12 in the supplemental material). Furthermore, E2F-1 was found to occupy the promoters of several genes in the neuregulin/ERBB signaling pathway (see Table S12 and Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

To investigate how the loss of E2F-1 activity could contribute to the development of cardiac dysfunction observed in the KI mice, the E2F-1 ChIP-sequencing data set was compared to the list of genes exhibiting altered expression in 2-month-old ERBB2 hypomorphic hearts. Strikingly, the promoter regions of 365 of the 685 (53%) modulated genes in our microarray were bound by E2F-1 (Fig. 4J). ChIP-sequencing enrichment ratio profiles, as well as standard ChIP and expression validation of a subset of these genes, are shown in Fig. 4K to M. Many of these modulated target genes encode proteins involved in cardiac muscle contractility, stress response, hypertrophy, ventricle morphology, and vascular integrity (see Table S13 in the supplemental material). In addition, IPA analysis identified an enrichment of the 365 ERBB2-dependent E2F-1 target genes in pathways involved in mediating cardioprotection against cardiac stress (e.g., gene encoding hypoxia-inducible factor 1α [HIF1α], eNOS, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 [ERK5], vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF], thrombopoietin, and Nrf2) and energy metabolism (e.g., peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α [PPARα]) (Fig. 5; see also Fig. S3 and Table S14 in the supplemental material). Moreover, epidermal growth factor (EGF) and integrin-linked kinase (ILK) signaling pathways implicated in cardiac growth, contractility, and repair, as well as insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) signaling associated with physiological cardiac hypertrophy, are targeted by the E2F-1-dependent transcriptional program (Fig. 5; see also Fig. S3 and Table S14 in the supplemental material).

FIG 5.

ERBB2 hypomorphic hearts have altered expression of E2F-1 ChIP-sequencing target genes involved in pathways associated with the regulation of cardiac homeostasis and the adaptive stress response. Subset of canonical pathways obtained by IPA software analysis of the 364 E2F-1 bound genes found differentially expressed in 2-month-old KI hearts compared to WT mice.

Of note, comparison of the E2F-1 ChIP-sequencing data set with the list of genes differentially regulated in the 6-month-old ERBB2 hypomorphic hearts revealed a 26% overlap in genes (see Fig. S4A in the supplemental material). Interestingly, several of the ERBB2/E2F-1 enriched pathways in 2-month-old animals were still modulated at 6 months (e.g., eNOS, ERK5, IGF-1, and PPARα) (Fig. 5; see also Fig. S4B and Table S15 in the supplemental material), suggesting that the inhibition of the ERBB2/E2F-1-dependent genetic program still plays an important role in the cardiac dysfunction observed (Fig. 4E).

Mice treated with the ERBB2 antibody 7.16.4 develop cardiac dysfunction and have decreased E2F-1 transcriptional activity.

Next, the antibody 7.16.4, capable of binding to the same subdomain of the ERBB2 receptor with some degree of epitope sharing as trastuzumab (23), was used to validate our previous findings in a different system (n = 8 mice per group). First, we investigated whether 7.16.4 treatment could affect the susceptibility of the heart to the cardiotoxic effects of cytotoxic agents as previously observed in humans with trastuzumab (2, 4). To this end, the lowest 7.16.4 dosage that has been shown to exert significant antitumorigenic effects on ERBB2-driven tumor growth in rodent models (24) was used in cotreatment with doxorubicin. Importantly, a greater increase in LV internal diameter, as well as further suppression of LVEF and LVFS, were observed in mice cotreated with doxorubicin and 7.16.4 compared to WT mice treated with doxorubicin or 7.16.4 alone (Fig. 6).

FIG 6.

Effect of doxorubicin and 7.16.4 cotreatment on cardiac function in mice. (A) Representative M-mode echocardiographic images of 2-month-old WT-treated mice. (B) Percentages of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) in 2-month-old treated WT animals. Bars represent means ± the SEM. n = 8 mice per group. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (C) Percentages of left ventricular fractional shortening (LVFS) in 2-month-old treated WT animals. Bars represent means ± the SEM. n = 8 mice per group. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (D) Echo-derived LV internal systolic chamber diameter in 2-month-old treated WT animals. Bars represent means ± the SEM. n = 8 mice per group. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Next, the 7.16.4 antibody was used to validate our findings obtained with the KI animals whereby postnatal developmental growth was used as a hemodynamic stress (n = 7 mice per group). Ultrasound echocardiography was performed on mice administered 7.16.4 over a 2-month period following birth to assess for signs of cardiac dysfunction. M-mode analyses demonstrated impaired systolic function in 7.16.4-treated mice relative to control-treated mice represented by a significant reduction in both LVEF and LVFS (Fig. 7A an B), indicating that the cardiac phenotype induced by 7.16.4 treatment closely resembles the cardiac dysfunction seen in the ERBB2 hypomorphic model (Fig. 2). As observed in ERBB2 KI hearts, treatment of WT mice with the 7.16.4 antibody resulted in decreased protein levels of ERBB2 and E2F-1 relative to control, and no decrease in other E2F family members was found (Fig. 7C). Likewise, 7.16.4 treatment led to a significant reduction in the mRNA levels of the E2F-1 target genes Myh9, Cdh5 and Irs2 important for the cardiac adaptive stress response (Fig. 7D). Interestingly, treatment of ERBB2 hypomorphic mice with 7.16.4 resulted in greater cardiac systolic dysfunction compared to both the KI and 7.16.4-treated mice alone (Fig. 8) (n = 7 mice per group). Taken together, our results provide further evidence that ERBB2 plays an important role in the heart's response to enhanced hemodynamic loads due to either physiological stimuli or pathological states.

FIG 7.

ERBB2 inhibition by antibody 7.16.4 diminishes E2F-1 transcriptional activity in mice. (A) Representative M-mode echocardiographic images from 2-month-old control or 7.16.4-treated mice. (B) Decreased LVEF and LVFS in the 7.16.4-treated animals compared to control mice. Bars represent means ± the SEM. n = 7 mice per group. *, P < 0.05. (C) Cardiac ERBB2 and E2F-1 protein levels in 2-month-old 7.16.4-treated mice compared to the control group. (D) Heart qRT-PCR analysis of E2F-1 target genes in 2-month-old 7.16.4-treated animals compared to control mice. Transcript levels of the genes in ERBB2 KI hearts relative to WT are also shown. Expression levels were normalized to Rplp0 levels. Bars represent means ± the SEM. *, P < 0.05.

FIG 8.

Cardiac dysfunction in ERBB2 hypomorphic (KI) hearts treated with the 7.16.4 antibody. (A) Representative M-mode echocardiographic images from 2-month-old KI control or 7.16.4-treated KI mice. (B) Decreased LVEF in the 7.16.4-treated KI animals compared to control hypomorphic mice. Bars represent means ± the SEM. n = 7 mice per group. *, P < 0.05. (C) Decreased left ventricular fractional shortening (LVFS) in the 7.16.4-treated KI animals compared to control hypomorphic mice. Bars represent means ± the SEM. n = 7 mice per group. *, P < 0.05.

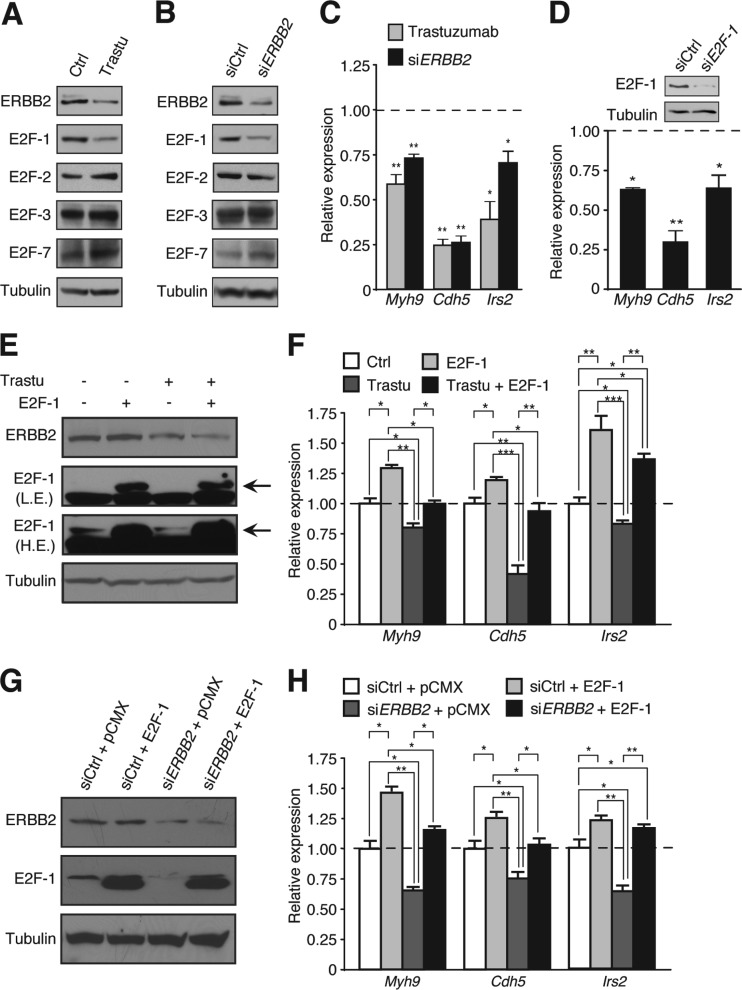

Inhibition of ERBB2 signaling in human cardiomyocytes by trastuzumab results in the ablation of E2F-1 activity.

To confirm that the ablation of an ERBB2/E2F-1 axis could diminish the cardiac adaptive stress response and thus contribute to the pathogenesis of trastuzumab-induced cardiac damage in breast cancer patients, we treated human cardiomyocytes in culture with trastuzumab. In this system, we observed a significant downregulation of E2F-1 protein levels concomitant with a reduction in ERBB2 levels (Fig. 9A). A similar effect was observed upon direct inhibition of ERRB2 expression using a pool of ERBB2-specific siRNAs (Fig. 9B). However, neither trastuzumab nor ERBB2-specific siRNA treatments reduced the protein levels of other E2F family members (Fig. 9A and B). As previously observed in the hearts of ERBB2 hypomorphic mice, inhibition of ERBB2 expression by trastuzumab or siRNAs in human cardiomyocytes also diminished the transcript levels of the E2F-1 targets Myh9, Cdh5, and Irs2 (Fig. 9C). Similarly, we observed a reduction in the expression of these genes when the human cardiomyocytes were treated with E2F-1-specific siRNAs (Fig. 9D), supporting the direct role of E2F-1 in the regulation of these genes. Overexpression of E2F-1 (Fig. 9E and G) was found to rescue the expression of the E2F-1 target genes involved in cardiac adaptive stress response in the presence of trastuzumab or siERBB2 (Fig. 9F and H).

FIG 9.

Trastuzumab inhibition of ERBB2 signaling in human cardiomyocytes impairs E2F-1 activity. (A) ERBB2 and E2F-1 protein levels in human cardiomyocytes treated with trastuzumab (Trastu). (B) ERBB2 and E2F-1 protein levels in human cardiomyocytes treated with siERBB2. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of E2F-1 target genes in trastuzumab- or siERBB2-treated cells. Expression levels were normalized to 18S levels. Bars represent means ± the SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. (D) qRT-PCR analysis of E2F-1 target genes in siE2F-1-treated human cardiomyocytes. Expression levels were normalized to RPLP0 levels. Bars represent means ± the SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Western blot analysis showing E2F-1 knockdown in cells. (E) Western blot analysis showing the rescue effects of E2F-1 overexpression in trastuzumab-treated human cardiomyocytes. Low exposure (L.E.) and high exposure (H.E.) detections are shown. (F) qRT-PCR analysis of E2F-1 target genes in cells cotreated with trastuzumab and an E2F-1 expression vector. Expression levels were normalized to RPLP0 levels. Bars represent means ± the SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (G) Western blot analysis showing the rescue effects of E2F-1 overexpression on E2F-1 in human cardiomyocytes cotransfected with siERBB2. (H) qRT-PCR analysis of E2F-1 target genes in human cardiomyocytes cotransfected with siERBB2 and E2F-1 expression vector. Expression levels were normalized to RPLP0 levels. Bars represent means ± the SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

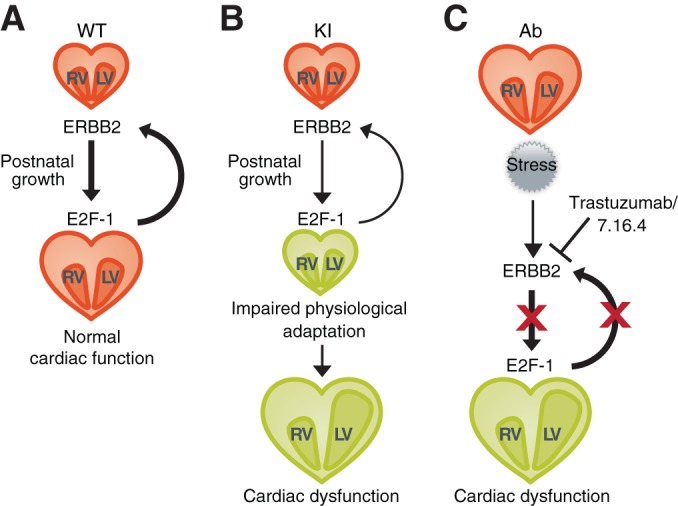

The tyrosine kinase receptor ERBB2 is best known for its oncogenic activity in breast cancer cells, but this protein also plays an important role during embryonic development, most particularly in the heart (3). Trastuzumab, a drug widely used to treat ERBB2-positive breast cancer patients since its introduction in 1998, can also induce cardiac dysfunction in patients (2, 4). Unfortunately, the mechanisms underlying the observed cardiotoxic effects remain poorly understood due to the lack of both cross-reactivity of trastuzumab with nonhuman ERBB2 and the lack of representative animal models. In the present study, we sought to develop appropriate mouse models as a means to further understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying the cardiotoxic effects of trastuzumab in the human heart. Taken together, our findings identify a pathological pathway induced by the inhibition of ERBB2 activity involving an E2F-1-dependent genetic program whose abrogation results in the development of cardiotoxic effects via impairment of the adaptive stress response (Fig. 10).

FIG 10.

Inhibition of the ERBB2/E2F-1 molecular axis results in the development of cardiac dysfunction via impairment of the cardiac adaptive stress response. (A) ERBB2 is a critical player in maintaining cardiac homeostasis via an E2F-1-dependent transcriptional program important in the adaptive stress response of the heart to enhanced hemodynamic loads during postnatal developmental growth. (B) Genetic (KI) reduction in ERBB2 signaling results in decreased expression of E2F-1 and its downstream target genes leading to cardiac dysfunction. (C) Therapeutic (Ab) reduction in ERBB2 signaling results in decreased expression of E2F-1 and its downstream target genes leading to cardiac dysfunction.

Our work first shows that downregulation of ERBB2 signaling in an ERBB2 hypomorphic mouse model results in a cardiac dysfunction closely resembling, on an ultrastructural and functional level, the clinical manifestations observed in humans administered trastuzumab. Notably, focal vacuolar changes and pleomorphic mitochondria, along with decreased LVEF, were found in ERBB2 hypomorphic hearts as manifested in humans experiencing trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity (2, 4, 19). In addition, the ERBB2 hypomorphic mice and 7.16.4-treated WT animals are more susceptible to doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity, suggesting that these two models could provide a means to investigate the cardiotoxic effects of novel therapeutic agents designed for cotreatment with trastuzumab.

Interestingly, the ERBB2 hypomorphic cardiac phenotype observed highlights a pivotal role for ERBB2 in the regulation of physiological cardiac hypertrophy, since the loss of this protein attenuated physiological but not pathological heart growth. This result is in accordance with a recent observation that Erbin, a binding partner of ERBB2, is important for compensated hypertrophy (25). Together, our results demonstrate an ongoing requirement for ERBB2 in adult myocardium to maintain homeostasis. Indeed, we show that impairing ERBB2 signaling while the heart is subjected to a physiologically relevant hemodynamic stress, such as the one generated during postnatal growth or induced by the coadministration of cardiotoxic drugs, leads to the development of cardiac dysfunction. In addition, we provide evidence that the molecular mechanisms underlying the onset of cardiac dysfunction in trastuzumab-treated patients and in the ERBB2 hypomorphic mice are similar. In support of this concept, we identified a common ERBB2/E2F-1-dependent molecular signature associated with the development of cardiotoxicity which is exhibited in both ERBB2 hypomorphic mice and mice treated with the anti-ERBB2 antibody 7.16.4. These results are consistent with a known role for E2F-1 in the maintenance of cardiac function (20). In addition, abrogation of ERBB2 signaling by trastuzumab in human cardiomyocytes induced a similar molecular signature, which could be rescued in large part by E2F-1 overexpression. These observations thus imply the existence of a previously unknown mechanistic link between ERBB2 signaling and E2F-1 transcriptional activity. Indeed, expression analyses and ChIP-sequencing studies revealed that a significant number of downregulated genes in ERBB2 hypomorphic hearts associated with cardiac function were in fact E2F-1 targets. Of particular interest, the ERBB2-dependent E2F-1 targets include several proteins involved in cardiac muscle contractility, conduction, maintenance of heart rate, cardiac homeostasis, adaptive stress response, hypertrophy, ventricle morphology, and vascular integrity that have previously been shown to play important roles in cardiac development and/or adult heart function. Cardiac tissue-specific ablation of a number of these pathways, such as ILK and AHR signaling, results in heart dysfunction and sudden death in animals, reinforcing the importance of the cardiac ERBB2/E2F-1 transcriptional program identified in our study (26–32). Of interest, thrombopoietin and ILK signaling, which have both been shown to protect against in vitro and in vivo anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity (33, 34), were modulated in the ERBB2-deficient hearts. Consistent with the synergistic increase in cardiac symptoms in patients coadministered trastuzumab and anthracyclines (2, 4), low thrombopoietin and ILK signaling via trastuzumab-dependent inhibition of ERBB2-E2F-1 activity may contribute to the increased susceptibility of patients to anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Moreover, IGF-1 signaling, known to be highly important in physiological hypertrophy (35), is also a target of the ERBB2/E2F-1 molecular axis.

The results of our investigation, taken together, indicate that ERBB2-dependent maintenance of E2F-1 expression is an important molecular conduit required to sustain a genetic program necessary for adult cardiovascular homeostasis and function and for the adaptive response of the heart to stress. Furthermore, our findings suggest that targeting cardiomyocytes to enhance E2F-1 action could provide a therapeutic avenue to mitigate trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity in breast cancer patients.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Carlo Ouellet, Majid Ghahremani and Maxime Caron for technical assistance and Sébastien Labrecque for figure design.

M.-C.P. was supported in part by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. M.-C.P. and L.J.E. are recipients of a studentship from the Fonds de Recherche Santé Québec. G.D. was supported by a predoctoral traineeship award (W81XWH-10-1-0489) from the U.S. Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program. This research was also supported by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (MOP-64275) to V.G. and a Program Project Grant from the Terry Fox Foundation (TFF-017003 and -020002) to V.G. and W.J.M.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 22 September 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/MCB.00895-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yarden Y, Pines G. 2012. The ERBB network: at last, cancer therapy meets systems biology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12:553–563. 10.1038/nrc3309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, Fuchs H, Paton V, Bajamonde A, Fleming T, Eiermann W, Wolter J, Pegram M, Baselga J, Norton L. 2001. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N. Engl. J. Med. 344:783–792. 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee KF, Simon H, Chen H, Bates B, Hung MC, Hauser C. 1995. Requirement for neuregulin receptor erbB2 in neural and cardiac development. Nature 378:394–398. 10.1038/378394a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seidman A, Hudis C, Pierri MK, Shak S, Paton V, Ashby M, Murphy M, Stewart SJ, Keefe D. 2002. Cardiac dysfunction in the trastuzumab clinical trials experience. J. Clin. Oncol. 20:1215–1221. 10.1200/JCO.20.5.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ewer MS, Vooletich MT, Durand JB, Woods ML, Davis JR, Valero V, Lenihan DJ. 2005. Reversibility of trastuzumab-related cardiotoxicity: new insights based on clinical course and response to medical treatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 23:7820–7826. 10.1200/JCO.2005.13.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crone SA, Zhao YY, Fan L, Gu Y, Minamisawa S, Liu Y, Peterson KL, Chen J, Kahn R, Condorelli G, Ross J, Jr, Chien KR, Lee KF. 2002. ErbB2 is essential in the prevention of dilated cardiomyopathy. Nat. Med. 8:459–465. 10.1038/nm0502-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozcelik C, Erdmann B, Pilz B, Wettschureck N, Britsch S, Hubner N, Chien KR, Birchmeier C, Garratt AN. 2002. Conditional mutation of the ErbB2 (HER2) receptor in cardiomyocytes leads to dilated cardiomyopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:8880–8885. 10.1073/pnas.122249299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheuer J, Malhotra A, Hirsch C, Capasso J, Schaible TF. 1982. Physiologic cardiac hypertrophy corrects contractile protein abnormalities associated with pathologic hypertrophy in rats. J. Clin. Invest. 70:1300–1305. 10.1172/JCI110729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gunther S, Grossman W. 1979. Determinants of ventricular function in pressure-overload hypertrophy in man. Circulation 59:679–688. 10.1161/01.CIR.59.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heineke J, Molkentin JD. 2006. Regulation of cardiac hypertrophy by intracellular signalling pathways. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7:589–600. 10.1038/nrm1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan R, Hardy WR, Dankort D, Laing MA, Muller WJ. 2004. Modulation of Erbb2 signaling during development: a threshold level of Erbb2 signaling is required for development. Development 131:5551–5560. 10.1242/dev.01425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Shahrour F, Minguez P, Tarraga J, Montaner D, Alloza E, Vaquerizas JM, Conde L, Blaschke C, Vera J, Dopazo J. 2006. BABELOMICS: a systems biology perspective in the functional annotation of genome-scale experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:W472–W476. 10.1093/nar/gkl172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Shahrour F, Minguez P, Vaquerizas JM, Conde L, Dopazo J. 2005. BABELOMICS: a suite of web tools for functional annotation and analysis of groups of genes in high-throughput experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:W460–W464. 10.1093/nar/gki456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dufour CR, Wilson BJ, Huss JM, Kelly DP, Alaynick WA, Downes M, Evans RM, Blanchette M, Giguere V. 2007. Genome-wide orchestration of cardiac functions by the orphan nuclear receptors ERRα and γ. Cell Metab. 5:345–356. 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen X, Xu H, Yuan P, Fang F, Huss M, Vega VB, Wong E, Orlov YL, Zhang W, Jiang J, Loh YH, Yeo HC, Yeo ZX, Narang V, Govindarajan KR, Leong B, Shahab A, Ruan Y, Bourque G, Sung WK, Clarke ND, Wei CL, Ng HH. 2008. Integration of external signaling pathways with the core transcriptional network in embryonic stem cells. Cell 133:1106–1117. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H, Durbin R. 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25:1754–1760. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y, Liu T, Meyer CA, Eeckhoute J, Johnson DS, Bernstein BE, Nusbaum C, Myers RM, Brown M, Li W, Liu XS. 2008. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9:R137. 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, Cheng JX, Murre C, Singh H, Glass CK. 2010. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell 38:576–589. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guarneri V, Lenihan DJ, Valero V, Durand JB, Broglio K, Hess KR, Michaud LB, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Hortobagyi GN, Esteva FJ. 2006. Long-term cardiac tolerability of trastuzumab in metastatic breast cancer: the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. J. Clin. Oncol. 24:4107–4115. 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.9551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cloud JE, Rogers C, Reza TL, Ziebold U, Stone JR, Picard MH, Caron AM, Bronson RT, Lees JA. 2002. Mutant mouse models reveal the relative roles of E2F1 and E2F3 in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:2663–2672. 10.1128/MCB.22.8.2663-2672.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weijts BG, Bakker WJ, Cornelissen PW, Liang KH, Schaftenaar FH, Westendorp B, de Wolf CA, Paciejewska M, Scheele CL, Kent L, Leone G, Schulte-Merker S, de Bruin A. 2012. E2F7 and E2F8 promote angiogenesis through transcriptional activation of VEGFA in cooperation with HIF1. EMBO J. 31:3871–3884. 10.1038/emboj.2012.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou J, Wu M, Xu S, Cheng M, Ding C, Liu Y, Yan H, Biyashev D, Kishore R, Qin G. 2013. Contrasting Roles of E2F2 and E2F3 in Cardiac Neovascularization. PLoS One 8:e65755. 10.1371/journal.pone.0065755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang H, Wang Q, Montone KT, Peavey JE, Drebin JA, Greene MI, Murali R. 1999. Shared antigenic epitopes and pathobiological functions of anti-p185(her2/neu) monoclonal antibodies. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 67:15–25. 10.1006/exmp.1999.2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katsumata M, Okudaira T, Samanta A, Clark DP, Drebin JA, Jolicoeur P, Greene MI. 1995. Prevention of breast tumour development in vivo by downregulation of the p185neu receptor. Nat. Med. 1:644–648. 10.1038/nm0795-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rachmin I, Tshori S, Smith Y, Oppenheim A, Marchetto S, Kay G, Foo RS, Dagan N, Golomb E, Gilon D, Borg JP, Razin E. 2014. Erbin is a negative modulator of cardiac hypertrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111:5902–5907. 10.1073/pnas.1320350111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernandez-Salguero PM, Ward JM, Sundberg JP, Gonzalez FJ. 1997. Lesions of aryl-hydrocarbon receptor-deficient mice. Vet. Pathol. 34:605–614. 10.1177/030098589703400609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hannigan GE, Coles JG, Dedhar S. 2007. Integrin-linked kinase at the heart of cardiac contractility, repair, and disease. Circ. Res. 100:1408–1414. 10.1161/01.RES.0000265233.40455.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sibilia M, Wagner B, Hoebertz A, Elliott C, Marino S, Jochum W, Wagner EF. 2003. Mice humanised for the EGF receptor display hypomorphic phenotypes in skin, bone and heart. Development 130:4515–4525. 10.1242/dev.00664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Banerjee I, Fuseler JW, Intwala AR, Baudino TA. 2009. IL-6 loss causes ventricular dysfunction, fibrosis, reduced capillary density, and dramatically alters the cell populations of the developing and adult heart. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 296:H1694–H1704. 10.1152/ajpheart.00908.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iyer NV, Kotch LE, Agani F, Leung SW, Laughner E, Wenger RH, Gassmann M, Gearhart JD, Lawler AM, Yu AY, Semenza GL. 1998. Cellular and developmental control of O2 homeostasis by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha. Genes Dev. 12:149–162. 10.1101/gad.12.2.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laustsen PG, Russell SJ, Cui L, Entingh-Pearsall A, Holzenberger M, Liao R, Kahn CR. 2007. Essential role of insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor signaling in cardiac development and function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:1649–1664. 10.1128/MCB.01110-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watanabe K, Fujii H, Takahashi T, Kodama M, Aizawa Y, Ohta Y, Ono T, Hasegawa G, Naito M, Nakajima T, Kamijo Y, Gonzalez FJ, Aoyama T. 2000. Constitutive regulation of cardiac fatty acid metabolism through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha associated with age-dependent cardiac toxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 275:22293–22299. 10.1074/jbc.M000248200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li K, Sung RY, Huang WZ, Yang M, Pong NH, Lee SM, Chan WY, Zhao H, To MY, Fok TF, Li CK, Wong YO, Ng PC. 2006. Thrombopoietin protects against in vitro and in vivo cardiotoxicity induced by doxorubicin. Circulation 113:2211–2220. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.560250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gu R, Bai J, Ling L, Ding L, Zhang N, Ye J, Ferro A, Xu B. 2012. Increased expression of integrin-linked kinase improves cardiac function and decreases mortality in dilated cardiomyopathy model of rats. PLoS One 7:e31279. 10.1371/journal.pone.0031279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Catalucci D, Latronico MV, Ellingsen O, Condorelli G. 2008. Physiological myocardial hypertrophy: how and why? Front. Biosci. 13:312–324. 10.2741/2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.