Abstract

To determine whether immune function is impaired among HIV-exposed but -uninfected (HEU) infants born to HIV-infected mothers and to identify potential vulnerabilities to vaccine-preventable infection, we characterized the mother-to-infant placental transfer of Haemophilus influenzae type b-specific IgG (Hib-IgG) and its levels and avidity after vaccination in Ugandan HEU infants and in HIV-unexposed U.S. infants. Hib-IgG was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in 57 Ugandan HIV-infected mothers prenatally and in their vaccinated HEU infants and 14 HIV-unexposed U.S. infants at birth and 12, 24, and 48 weeks of age. Antibody avidity at birth and 48 weeks of age was determined with 1 M ammonium thiocyanate. A median of 43% of maternal Hib-IgG was transferred to HEU infants. Although its level was lower in HEU infants than in U.S. infants at birth (P < 0.001), Hib-IgG was present at protective levels (>1.0 μg/ml) at birth in 90% of HEU infants and all U.S. infants. HEU infants had robust Hib-IgG responses to a primary vaccination. Although Hib-IgG levels declined from 24 to 48 weeks of age in HEU infants, they were higher than those in U.S. infants (P = 0.002). Antibody avidity, comparable at birth, declined by 48 weeks of age in both populations. Early vaccination of HEU infants may limit an initial vulnerability to Hib disease resulting from impaired transplacental antibody transfer. While initial Hib vaccine responses appeared adequate, the confluence of lower antibody avidity and declining Hib-IgG levels in HEU infants by 12 months support Hib booster vaccination at 1 year. Potential immunologic impairments of HEU infants should be considered in the development of vaccine platforms for populations with high maternal HIV prevalence.

INTRODUCTION

In unvaccinated infants, Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) is the most common cause of childhood meningitis and epiglottitis and a leading cause of pneumonia, arthritis, bacteremia, and cellulitis worldwide (1, 2). The infection is now rare in industrialized countries following the broad uptake of the Hib polysaccharide conjugate vaccine but remains a major contributor to childhood morbidity and mortality in resource-limited countries (3). Even where the vaccine has been introduced in many low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), vaccine failures do occur, and though many have been attributed, in part, to HIV coinfection, a significant number of cases also occur in HIV-uninfected infants (4, 5).

HIV-exposed but -uninfected (HEU) infants represent a significant cohort worldwide (approximately 1.5 million births yearly), primarily in LMIC (6). Mortality in this population is higher than in infants of uninfected mothers, and these children are at increased risk of pneumonia and diarrhea, which may relate in part to altered immune maturation and function in HEU infants compared with those in unexposed infants of HIV-uninfected mothers (7–11). Such potential immune impairment may also compromise responses to primary vaccination in the first year of life and lead to specific susceptibility to vaccine-preventable illnesses, including Hib (12). The initial protection of infants from severe infections such as Hib is derived, in part, from maternal IgG passed across the placenta until adequate natural or vaccine-induced immunity is established. Indeed, HIV-associated maternal immune dysfunction may contribute to decreased quantity, quality, and transplacental transfer of pathogen-specific antibody, further limiting adequate protection of HEU infants very early in life (13).

Although quantitative levels of Hib-specific IgG are most commonly measured, the quality of antibody generated with vaccine (or avidity, a measure of the strength of antibody binding) may be an important and independent determinant of protection (14). For example, antibody avidity correlated with serum bactericidal activity in 22 children boosted with Hib vaccine at 18 months, whereas the quantitative antibody level did not (15) (6). Moreover, naturally derived Hib antibodies are protective at lower concentrations than those derived from vaccine responses, an observation that may relate to antibody avidity (14).

In this study, we characterized the development of Hib-specific IgG in Ugandan HEU infants by quantification of transplacental transfer, responses to primary Hib vaccination, and evolution of the avidity of Hib- and Hib vaccine-associated diphtheria toxoid-specific IgG through their first year of life.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study populations.

This analysis was part of a prospective study of the impact of breast-feeding practices on a cohort of uninfected Ugandan infants born to HIV-infected mothers between 2010 and 2013. One hundred one mother-infant dyads were recruited from the Mulago Hospital Antenatal Clinic in Kampala, Uganda. Of these, 57 had previously undergone a stool microbiome assessment; these same 57 were selected for the present study. The enrollment criteria for women were HIV infection, an age of ≥18 years, 32 to 38 weeks of gestation at enrollment, and planning to breastfeed for 6 months. The eligibility criteria for infants were a singleton birth weight of >2,500 g and the absence of life-threatening conditions. All pairs received perinatal prophylaxis preventing mother-to-child transmission. One infant was infected prenatally and was not included in this study. Clinical and anthropometric data, infant blood and stool, and maternal breast milk samples were obtained at birth (within 72 h) and 12, 24, and 48 weeks later. Hib polysaccharide conjugate vaccine (Tritanrix HepB/Hib [DTwP/HBV/PRP-T]; GlaxoSmithKline) was given to all subjects at 6, 10, and 14 weeks of age, according to Uganda Ministry of Health guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained for all subjects with protocols approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board, the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, the Makerere University School of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee, and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology.

In addition, serum samples from 14 healthy infants (30% female; birth weight, 3.6 ± 3 kg) born to HIV-negative women 18 to 40 (mean, 31.6 ± 5.0) years old in Aurora, CO, with enrollment criteria comparable to those of the Ugandan cohort were collected at equivalent time points. This cohort was included to put certain features of Hib responses in the Ugandan HEU infants into context (e.g., levels at birth, avidity and decline at 1 year) rather than as a formal control population, particularly given the later vaccination schedule (Hib vaccinations were administered at 2, 4, and 6 months) and different vaccine formulation (U.S. infants received Hib conjugate vaccine combined with acellular pertussis vaccine). Furthermore, maternal plasma was not obtained at enrollment from the U.S. mothers and the maternal Hib vaccination status was unknown (the cohort included women born both before and after the introduction of routine childhood Hib vaccination in the United States). Thus, the two populations were evaluated in a side-by-side descriptive analysis of Hib immunity through the first year of life in the two populations.

Laboratory methods. (i) ELISA for Hib-specific IgG.

Hib IgG concentrations were determined by indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously described, by using Hib polyribosylribitol phosphate (PRP) linked to tyrosine hydrochloride (Connaught Labs, Toronto, Canada) as the capture antigen, a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-IgG antibody (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME), and a 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine-based developer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) (16). Antibody concentrations in serial dilutions were determined with a reference serum standard with a known PRP-specific IgG antibody concentration (Connaught Labs). All samples were run in duplicate and included an internal control sample with a known concentration. The coefficient of variation of the controls on each plate was 10% ± 5%.

(ii) DT-specific IgG ELISA.

We measured diphtheria toxin (DT)-specific IgG by ELISA as previously described (17). DT (Massachusetts Department of Public Health Biolabs), which differs from the Hib vaccine protein conjugate CRM197 (cross-reactive material 197) by only one amino acid, was bound as the capture antigen (1 μg/ml). Other steps were as described above but with the serum IgG concentration as the assay standard. The coefficient of variation was 10.5% ± 5%.

(iii) Hib- and DT-specific IgG subtype ELISA.

Hib- and DT-specific IgG1 and IgG2 concentrations were measured by using similar ELISA methods, substituting biotin-conjugated anti-IgG1 HP6069 (EMD Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) or anti-IgG2 HP6002 (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) as conjugates.

(iv) Hib-IgG avidity assay.

The avidity of Hib-IgG was determined with the chaotropic agent ammonium thiocyanate (NH4SCN) to disrupt weaker antibody-antigen binding, by a modified form of the method described by Goldblatt et al. (18). After incubating serum samples diluted to produce an optical density (OD) of 0.8 to 1.0 by ELISA and washing, 100 μl of NH4SCN was added to serial wells at 0.1 to 6 M for 30 min, washed, and developed as described above. The avidity index was the molar concentration of NH4SCN required to reduce the OD by 50%. Because the amounts of infant serum samples available were limited, we adapted the avidity assay to the use of only 1 M NH4SCN, with avidity (percent retention on the plate with 1 M NH4SCN) defined as (OD with 1 M NH4SCN/OD at baseline) × 100. The log10-transformed results of this proxy assay correlated closely with the serial dilution avidity index by linear regression (r = −0.8986; P < 0.001; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

(v) Clinical immune assays.

We measured total serum IgG, IgM, and IgA levels at Children's Hospital Colorado by nephelometry (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) and determined complete and differential blood counts by using standard automated hematology techniques in Uganda. Lymphocyte lineages and subsets were characterized by whole-blood flow cytometry with fluorescently labeled monoclonal antibodies to CD19 for B cells; CD3, CD4, and CD8 for T cells; and CD45RA and CCR7 for naive/memory cells analyzed on a FACSCanto (BD Biosystems) using FlowJo software.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was done with Stata, version 11.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Geometric mean Hib-specific IgG concentrations in mothers at enrollment and in infants at birth and 12, 24, and 48 weeks of age as primary outcomes were compared at different time points within groups with paired t tests and comparisons of continuous variables between HEU and HIV-unexposed uninfected (HUU) populations with nonparametric Mann-Whitney tests given the low number of HUU subjects. Secondary outcomes included change in Hib-IgG over time and avidities at each time within groups and between groups and were assessed by using paired t tests. No correction was made for multiple comparisons, as the overall number of analyses was low. To compare placental transfer of Hib- and DT-specific IgG (paired, nonparametric data) and proportions of IgG subtypes, we used Mann-Whitney tests. Simple linear regression was used to correlate the proportions in the 1 M NH4SCN avidity assay with the full avidity index and to assess the correlation between the maternal antibody concentration and placental transfer. Correlations among antibody levels, changes in antibody levels between time points, and continuous variables such as hematologic parameters and total immunoglobulins were assessed by using linear regression. Antibody levels and avidity indexes were log10 transformed for regression analysis. The P value for statistical significance was set at ≤0.05.

RESULTS

Study population characteristics.

Baseline demographic, clinical anthropometric, and clinical data on the subjects enrolled in this study are summarized in Table 1. All of the enrolled Ugandan mothers had a CD4 cell count of >350/cm3, and 77% had HIV RNA loads of <10,000 copies/ml. Only infants of adequate birth weight (>2,500 g) were enrolled; however, poor weight gain was commonly observed through the study period, with 10% of the subjects showing severe malnutrition by 1 year (z-scores of <2 for weight according to World Health Organization [WHO] standard growth parameters; data not shown). All of the infants in the United Sates and Uganda were exclusively breast fed after birth, and two-thirds of those at both sites were exclusively breast fed in the first 24 weeks of the study.

TABLE 1.

Clinical characteristics of 57 HIV-infected mothers and uninfected infants in Uganda

| Group and characteristic | Value | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Mothers | ||

| Mean age (yr) | 25.1 | 4.9 |

| Median no. of HIV copies/ml | 1,538 | 20–73,900 |

| Median CD4 cell count/cm3 | 641 | 367–1,301 |

| % with spontaneous vaginal delivery | 100 | |

| Infants | ||

| Mean birth wt (kg) | 3.71 | 3.1–4.4 |

| Mean birth wt for age (z-score) | −0.08 | −1.65–1.08 |

| Mean 48-wk wt (kg) | 8.7 | 5.7–10.6 |

| Mean 48-wk wt for age (z-score) | −0.68 | −3.52–1.45 |

| % of females | 50 | |

| % Exclusively breast fed at 24 wk | 67 |

Mother-to-infant transplacental antibody transfer.

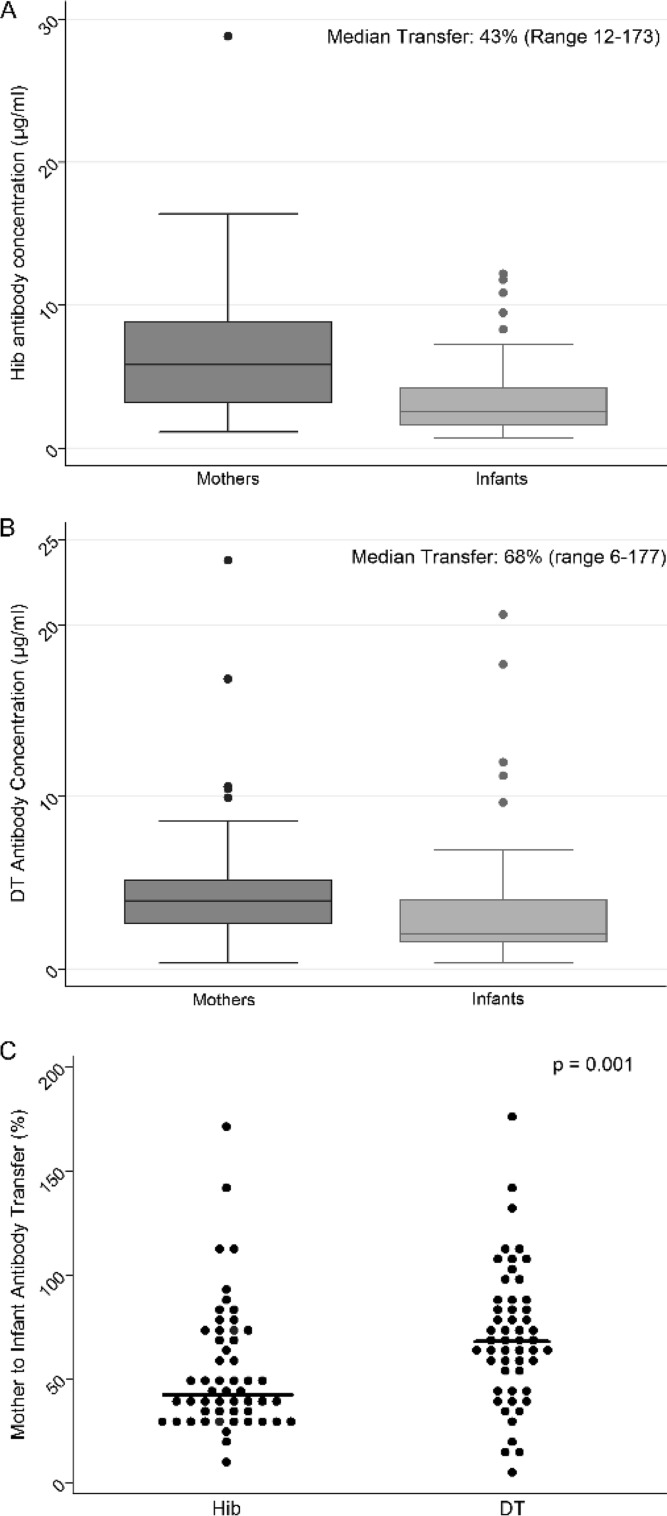

Among 52 Ugandan infants whose serum was available at birth, the geometric mean Hib IgG level was significantly lower than the maternal values (median, 2.6 versus 5.7 μg/ml, respectively; P = 0.01 [paired t test]) (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, all of the mothers and 90% of the infants had Hib-IgG levels above the threshold for long-term protection (>1.0 μg/ml). Among Ugandan newborns, the median transplacental transfer of Hib-IgG was 43% (range, 12 to 173%). In contrast, transfer of IgG to the DT protein in the same subjects was more efficient (median, 68% [range, 6 to 177%]; P = 0.001 [Mann-Whitney test]) (Fig. 1B and C). We identified no significant correlation in the proportional transfer of Hib- and DT-specific IgG between mother-infant dyads. Serum samples were not available from U.S. mothers to assess transfer. Specific IgG1 and IgG2 subclasses comprised comparable proportions of IgG to the polysaccharide Hib and to the protein DT in 20 mother-infant pairs (Table 2). The majority of the IgG to both vaccine antigens was of the IgG1 subclass in both mothers and infants. The proportion of specific IgG transferred did not correlate with either the subclass or the level of these antibodies in maternal serum samples (Fig. 2).

FIG 1.

H. influenzae type b (A), DT IgG concentration in HIV-infected mothers in Uganda before birth and in their HIV-uninfected infants at birth (B), and percent mother-to-infant Hib and DT IgG antibody transfer (C) (n = 52 mother-infant pairs; P value from Wilcoxon rank sum test).

TABLE 2.

Subclass distribution of IgG to Hib and DT in 20 mother-infant pairs

| Group | Mean % IgG1a (range) |

P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hib | DT | ||

| Mothers | 88.7 (14.8–98.2) | 86.5 (17.7–98.7) | 0.98 |

| Infants | 84.4 (30.3–96.0)c | 88.3 (50.7–99.1)d | 0.14 |

Percent IgG1 = (concentration [μg/ml] of specific IgG1/specific IgG1 + IgG2) × 100.

Determined by Wilcoxon rank sum test (Hib versus DT).

P = 0.64 by Wilcoxon rank sum test (mother versus infant).

P = 0.39 by Wilcoxon rank sum test (mother versus infant).

FIG 2.

Correlation of percent transfer of Hib- and DT-specific IgG and concentration of maternal antibody (n = 20 mother-infant pairs; P values from linear regression for each antigen and analysis of covariance for comparison between antigens).

Antibody responses to primary vaccine series.

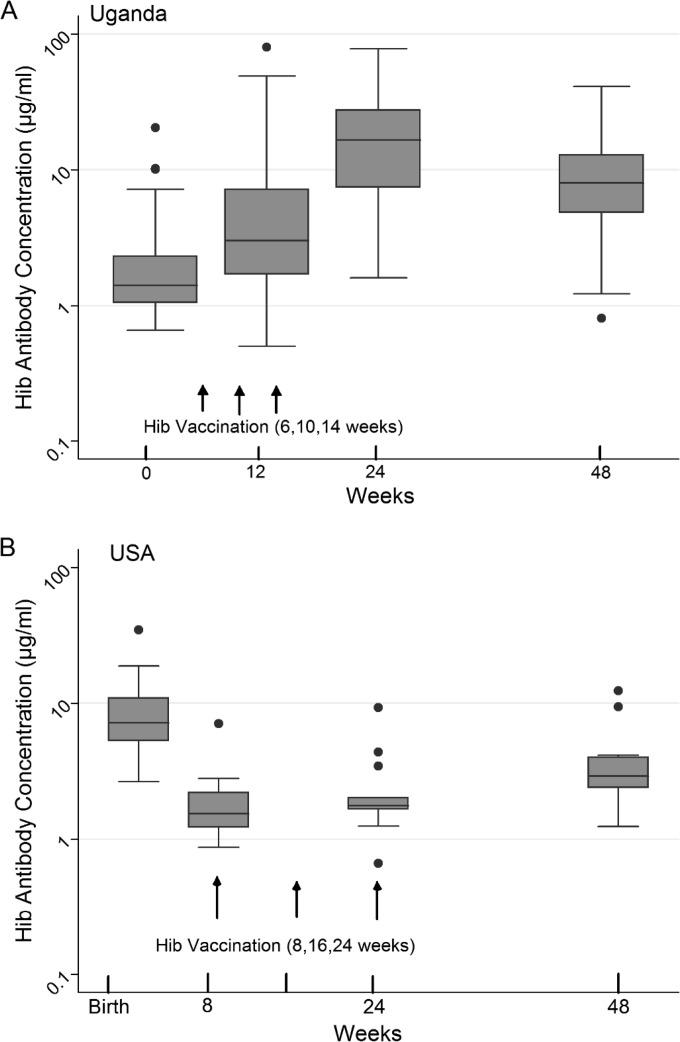

All of the infants in our HEU cohort mounted robust antibody responses at 24 weeks after receiving three doses of Hib conjugate vaccine at 6, 10, and 14 weeks (Fig. 3A). By 12 weeks of age (following two Hib vaccinations), 91% had protective levels (>1.0 μg/ml), as did all of the infants by 24 weeks after three doses. Levels of Hib-specific IgG at birth did not predict or correlate with those at 12 or 24 weeks of age. From a peak geometric mean titer (GMT) of 13.7 μg/ml at 24 weeks, Hib-specific IgG levels declined in 86% of the subjects to 7.5 μg/ml at 48 weeks (P < 0.001, paired t test), although 98.3% still retained protective levels.

FIG 3.

H. influenzae type b antibody concentrations at four time points in the first year of life in Ugandan HIV-exposed but -uninfected (A) and U.S. HIV-unexposed (B) infants (n = 57 Ugandan and 14 U.S. infants).

Among the U.S. infants, the GMT of Hib-specific IgG was significantly higher than that in the Ugandan HEU infants at birth (8.1 versus 1.7 μg/ml, respectively; P < 0.001 [Mann-Whitney test]) (Fig. 3B). After receiving three vaccine doses on an accelerated schedule, Ugandan HEU infants had generated greater responses than U.S. infants, who had received only two doses by that time. This difference persisted at 48 weeks (7.5 versus 3.3 μg/ml, respectively; P = 0.002 [Mann-Whitney test]).

The pattern of DT antibody levels through the first year of life in the Ugandan infants was similar to that of Hib antibody levels. The lowest levels were seen at birth (median, 3.5 [range, 1.2 to 31.8] μg/ml), followed by a peak at the 24-week time point (median, 121.0 [range, 0.5 to 544] μg/ml) following completion of the three-dose primary vaccine series. However, DT-specific IgG declined less consistently from 24 to 48 weeks than did Hib-specific IgG, declining in 65 versus 86% of the infants, respectively. Antibody levels at birth did not directly or inversely correlate with vaccine responses at subsequent time points.

Correlates of Hib antibody responses.

We determined whether the hematologic (lymphocyte numbers and hemoglobin levels), immunologic (numbers of CD19+ B cell and CD3+ and CD4+ T cells), feeding (duration of all or exclusive breastfeeding), or anthropometric (length for age, weight for length) characteristics of each child correlated with the levels of or changes in Hib-IgG levels or avidity in the HEU cohort. In this context, the total lymphocyte count (r = 0.308; P = 0.03), CD3+ T cell count (r = 0.357; P = 0.01), and CD4+ T cell count (r = 0.283; P = 0.05), and total serum IgG level showed a weak positive correlation with the Hib-IgG level at 48 weeks (r = 0.300; P = 0.03 [linear regression]), but growth, nutritional status, and breastfeeding status did not.

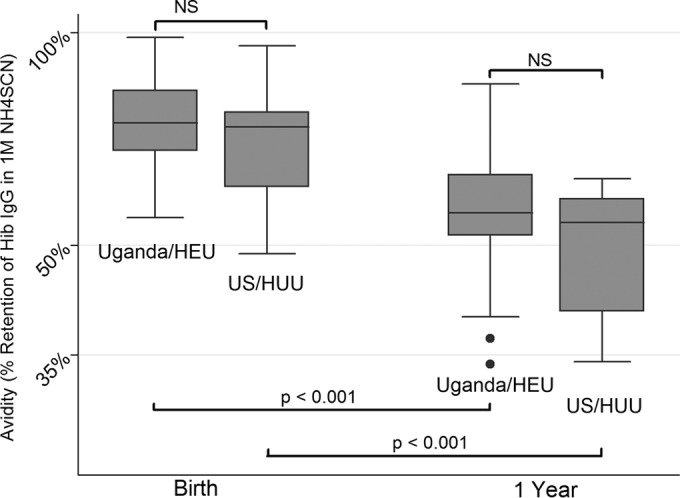

Avidity of Hib-specific IgG.

The avidities (binding strengths) of Hib-IgG in Ugandan HEU infants and U.S. HIV-unexposed infants at birth were comparable (Fig. 4). These avidities remained comparable in the two groups at 48 weeks. However, despite the administration of three doses of the Hib conjugate vaccine in the intervening year, the avidities declined significantly from birth to 48 weeks of age (P < 0.001 for both groups [paired t tests]).

FIG 4.

Avidity in 1 M ammonium thiocyanate of H. influenzae type b IgG from Ugandan HIV-exposed but -uninfected and U.S. HIV-unexposed infants at birth and 1 year of age. The avidity percentage represents the percentage of Hib-specific IgG persistently bound in the presence of 1 M ammonium thiocyanate. A higher percentage represents greater avidity for and strength of binding to the solid-phase Hib capsular PRP antigen. Statistical comparisons are represented by dark horizontal lines; P values are for unpaired t tests (n = 23 Ugandan and 14 U.S. infants). NS, not significant.

DISCUSSION

In this cohort of maternally HIV-exposed but -uninfected Ugandan infants who are at increased risk for infectious complications (8), we identified a relatively low proportion of transplacental passage of Hib antibody. Hib-specific IgG responses following primary vaccination were robust in the fully vaccinated Ugandan infants despite the low levels at birth, decreased nutritional status, and initial HIV exposure. The Hib-specific IgG level was greater at 48 weeks in vaccinated Ugandan than in U.S. infants. These antibodies were similar in quality (avidity) in the two geographically disparate groups. However, despite significant vaccine responses, the levels of these antibodies declined by nearly half from 24 to 48 weeks in Ugandan infants, concomitant with a potential vulnerability stemming from decreased antibody quality, as measured by our avidity assay.

A striking difference in the Ugandan HEU infants compared with the U.S. infants was the relatively lower level of Hib IgG at birth, which may result in a period of increased vulnerability to Hib disease in these HEU newborns. Ten percent of the newborns were below the putative protective Hib IgG level of 1 μg/ml at birth, a proportion that would likely increase prior to the emergence of vaccine-induced immunity as a result of postnatal decay in maternal IgG. The birth levels of Hib IgG in the U.S. population are consistent with those observed in previous studies of Hib-vaccinated women (19). Thus, much of the disparity at birth between the Ugandan and U.S. babies may be due to receipt of Hib vaccination in at least some U.S. mothers, resulting in increases in maternal IgG. However, impaired transplacental transmission in association with HIV infection may also have contributed. The 43% placental transfer of Hib IgG in the 52 HEU infants in our study is consistent with a 61% reduction relative to HUU infants found in 12 HIV-infected mothers in the United Kingdom and 57% Hib-IgG transfer in 46 HIV-exposed but -uninfected infants in South Africa (12, 20). Each of these proportions of transplacental transfer is notably lower than those reported in healthy pregnancies in both developed and developing countries, which are consistently above 90% (21–23). This limited transfer with resulting low levels of Hib-specific IgG in HIV-exposed infants supports the earlier timing of vaccinations advanced by the WHO Expanded Program on Immunization for this population (6, 10, and 14 weeks) compared with the later 8-, 16-, and 24-week schedule common in many developed nations. Decreased transplacental antibody transfer in HIV-infected mothers has also been described for varicella-zoster virus, tetanus toxoid, measles virus, streptolysin O, pertussis, and Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular antigens (24–28).

The low level of mother-to-child transfer of specific IgG in our HIV-infected cohort was also more pronounced for antibodies reactive with Hib polysaccharide (43% transferred) than for diphtheria toxoid protein (68% transferred). One theory is that the efficiency of transfer may differ among IgG subclasses (29). Maternal antibodies to polysaccharide antigens such as Hib after natural exposure have been shown to contain a higher proportion of the IgG2 subtype, which may not be transported across the placenta as efficiently as IgG1, the subclass that makes up the majority of the IgG to protein antigens such as DT (30–32). However, we found that the IgG1, rather than the IgG2, subclass made up the majority of the antibodies to both Hib and DT in our HIV-infected Ugandan mothers and their infants and that the proportions of each subclass were similar in both groups and in both mothers and infants (Table 2). To ensure that this proportion was not mediated by poor IgG2 assay sensitivity, we confirmed the predominance (87%) of IgG2 to pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides relative to IgG1 in five previously pneumococcal-vaccine-treated healthy adults (data not shown), as previously reported (33). Our data raise the possibility that the ability of HIV-infected adults to produce IgG2 may also be compromised.

Other potential mechanisms underlying the decrement in placental transfer of IgG during maternal HIV infection may include competitive inhibition with high levels of circulating total IgG (hypergammaglobulinemia), IgG glycosylation, malaria exposure, malnutrition, and placental inflammation, including its effect on the expression and transport of IgG by the neonatal IgG receptor (FcRN) (13, 25, 27). Transplacental passage of IgG was not directly dependent on maternal concentrations. However, we identified significant heterogeneity of transfer in our population (e.g., several infants showed higher concentrations of specific IgG at birth than their mothers), a phenomenon that may relate to both variance in the assay and high placental efficiency in certain individuals (34).

Maternal HIV exposure did not appear to compromise infant responses to the primary Hib vaccine series, which were robust in all subjects, consistent with previous reports (35, 36). Indeed, the vaccine responses in our study are typical of observations in non-HIV-exposed populations in developing countries, where initial Hib vaccine responses may be more vigorous than in higher-income populations (37), as observed in Nepal, South Africa, and Latin America, where 95 to 100% of the infants generate protective levels of Hib-specific IgG (>1 μg/ml) after a primary series. Indeed, even fractional doses (a fraction of the typical dose) of vaccine have been highly immunogenic in developing countries (38–41). Furthermore, Hib vaccine responses do not appear to be affected by combination with whole-cell pertussis vaccine, such as that used in our Ugandan cohort and many low- and middle-income nations, whereas acellular pertussis vaccines are associated with decreased Hib antibody responses when used in combination, a phenomenon that may explain the higher levels of Hib IgG at 1 year among the Ugandan infants in this study (42).

Despite the adequate vaccine responses at 24 weeks of age in Ugandan infants, two observations at the 48-week time point raise concerns for waning protection in the second year of life. The first, the decrease in Hib IgG concentrations from 24 to 48 weeks of age, may lead to levels below the protective threshold in the ensuing months, consistent with previous findings in both HIV-exposed and -unexposed infants (35, 38, 43). Such data have been invoked in support of a recommendation for a booster dose at 1 year. The second observation, decreased antibody avidity relative to birth values, may further complicate the clinical significance of declining antibody levels. At birth, Hib-specific IgG is essentially all of maternal origin and, in the case of both of our study populations, likely derived primarily from natural exposure. Conversely by 48 weeks of age, the antibody will be the infant's own, derived in large part from vaccine, which may be less effective than the naturally derived antibody. In Scandinavia, an antibody level of 0.15 μg/ml was adequate for protection from Hib disease in populations with naturally derived Hib immunity, whereas in populations with vaccine-derived immunity, a much higher level of 1.0 μg/ml was required for protection (44). Thus, the risk of underprotection in the newborn period because of low maternal placental transfer may be ameliorated to some extent by the higher-quality antibody, but at 1 year, adequate levels of specific IgG may overestimate protection in the setting of low antibody avidity. Thus, infants with lowest-avidity antibodies may even be vulnerable at antibody levels greater than the 1.0-μg/ml threshold. Planned future work characterizing functional antibody assessment including bactericidal assays may more clearly define these potential vulnerabilities.

Limitations of our study include the absence of a Ugandan HIV-unexposed control group which limits our ability to analyze the impact of HIV infection on impaired placental transfer. The relevance of a small cohort of U.S.-borne HIV-unexposed infants as a reference population is limited because of a number of differences from our study population, including reduced environmental exposure to infectious agents, better nutrition, and, importantly, the Hib vaccination schedule. The unknown Hib vaccination status of the U.S. mothers and the lack of a maternal serum sample in this cohort prevent comparison of transplacental transmission and do not allow a full understanding of the differences in Hib IgG at birth. However, the U.S. cohort does allow direct comparison of Hib antibody levels at 1 year and differences over time in antibody avidity, data that will inform decisions regarding the use of a booster dose of Hib vaccine after the first year of life.

Current WHO recommendations, adopted by most sub-Saharan African countries, often result in complete Hib vaccination by as early as 14 weeks of age (45, 46). The booster dose administered at 12 to 15 months in many higher-income countries is not formally included in the WHO recommendations. Our findings provide an additional rationale for previous evidence that residual Hib disease in older children will continue to occur and suggest the possibility of an increased risk of disease in infants not fully vaccinated as a consequence of increased household Hib colonization rates in older children (47, 48). The development of a 1-year booster platform in developing countries including Hib, pneumococcal conjugate, and measles vaccines might better address the gaps in protection raised in this study and may support a more balanced approach to the prevention of Hib infection in both infants and older children (49).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 HD059527 and R21AI083615 to E.J., NIH K24 DK083772 to N.F.K.), the Elisabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation (MV-00-9-900-01432-0-00 to E.J.), the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Colorado Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (UL1 TR000154 to J.T.G. and UL1 RR025780 to E.J.), the Mucosal and Vaccine Research Colorado program, and the Veterans Affairs Research Service. The contents of this report are solely our responsibility and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

We thank Weiming Zhang for statistical and database support and particularly the research staff at Makerere University and Johns Hopkins University and the participants for their commitment to this study under often challenging circumstances.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 8 October 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/CVI.00356-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.St. Geme J. 2008. Haemophilus influenzae, p 892–897 In Long S, Pickering L, Prober C. (ed), Principles and practice of pediatric infectious diseases, 3rd ed. Elsevier, Inc., Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peltola H. 2000. Worldwide Haemophilus influenzae type b disease at the beginning of the 21st century: global analysis of the disease burden 25 years after the use of the polysaccharide vaccine and a decade after the advent of conjugates. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:302–317. 10.1128/CMR.13.2.302-317.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watt JP, Wolfson LJ, O'Brien KL, Henkle E, Deloria-Knoll M, McCall N, Lee E, Levine OS, Hajjeh R, Mulholland K, Cherian T. 2009. Burden of disease caused by Haemophilus influenzae type b in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet 374:903–911. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Gottberg A, Cohen C, Whitelaw A, Chhagan M, Flannery B, Cohen AL, de Gouveia L, Plessis MD, Madhi SA, Klugman KP, Group for Enteric, Respiratory, Meningeal Disease Surveillance in South Africa (GERMS-SA) 2012. Invasive disease due to Haemophilus influenzae serotype b ten years after routine vaccination, South Africa, 2003-2009. Vaccine 30:565–571. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee EH, Lewis RF, Makumbi I, Kekitiinwa A, Ediamu TD, Bazibu M, Braka F, Flannery B, Zuber PL, Feikin DR. 2008. Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine is highly effective in the Ugandan routine immunization program: a case-control study. Trop. Med. Int. Health 13:495–502. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. 2013. Mother-to-child transmission of HIV: data and statistics. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/hiv/topics/mtct/data/en/index1.html Accessed 18 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brahmbhatt H, Kigozi G, Wabwire-Mangen F, Serwadda D, Lutalo T, Nalugoda F, Sewankambo N, Kiduggavu M, Wawer M, Gray R. 2006. Mortality in HIV-infected and uninfected children of HIV-infected and uninfected mothers in rural Uganda. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 41:504–508. 10.1097/01.qai.0000188122.15493.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shapiro RL, Lockman S, Kim S, Smeaton L, Rahkola JT, Thior I, Wester C, Moffat C, Arimi P, Ndase P, Asmelash A, Stevens L, Montano M, Makhema J, Essex M, Janoff EN. 2007. Infant morbidity, mortality, and breast milk immunologic profiles among breast-feeding HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women in Botswana. J. Infect. Dis. 196:562–569. 10.1086/519847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyamoto M, Pessoa SD, Ono E, Machado DM, Salomao R, Succi RC, Pahwa S, de Moraes-Pinto MI. 2010. Low CD4+ T-cell levels and B-cell apoptosis in vertically HIV-exposed noninfected children and adolescents. J. Trop. Pediatr. 56:427–432. 10.1093/tropej/fmq024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bunders M, Pembrey L, Kuijpers T, Newell ML. 2010. Evidence of impact of maternal HIV infection on immunoglobulin levels in HIV-exposed uninfected children. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 26:967–975. 10.1089/aid.2009.0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borges-Almeida E, Milanez HM, Vilela MM, Cunha F, Abramczuk BM, Reis-Alves SC, Metze K, Lorand-Metze I. 2011. The impact of maternal HIV infection on cord blood lymphocyte subsets and cytokine profile in exposed non-infected newborns. BMC Infect. Dis. 11:38. 10.1186/1471-2334-11-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones C, Pollock L, Barnett SM, Battersby A, Kampmann B. 2013. Specific antibodies against vaccine-preventable infections: a mother-infant cohort study. BMJ Open 3(4):e002473. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palmeira P, Quinello C, Silveira-Lessa AL, Zago CA, Carneiro-Sampaio M. 2012. IgG placental transfer in healthy and pathological pregnancies. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2012:985646. 10.1155/2012/985646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agbarakwe AE, Griffiths H, Begg N, Chapel HM. 1995. Avidity of specific IgG antibodies elicited by immunisation against Haemophilus influenzae type b. J. Clin. Pathol. 48:206–209. 10.1136/jcp.48.3.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hetherington SV, Lepow ML. 1992. Correlation between antibody affinity and serum bactericidal activity in infants. J. Infect. Dis. 165:753–756. 10.1093/infdis/165.4.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiss PJ, Wallace MR, Oldfield EC, III, O'Brien J, Janoff EN. 1995. Response of recent human immunodeficiency virus seroconverters to the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine and Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 171:1217–1222. 10.1093/infdis/171.5.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janoff EN, Hardy WD, Smith PD, Wahl SM. 1991. Humoral recall responses in HIV infection. Levels, specificity, and affinity of antigen-specific IgG. J. Immunol. 147:2130–2135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldblatt D, Vaz AR, Miller E. 1998. Antibody avidity as a surrogate marker of successful priming by Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccines following infant immunization. J. Infect. Dis. 177:1112–1115. 10.1086/517407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Englund JA, Glezen WP. 2003. Maternal immunization with Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccines in different populations. Vaccine 21:3455–3459. 10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00350-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones CE, Naidoo S, De Beer C, Esser M, Kampmann B, Hesseling AC. 2011. Maternal HIV infection and antibody responses against vaccine-preventable diseases in uninfected infants. JAMA 305:576–584. 10.1001/jama.2011.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Englund JA, Glezen WP, Turner C, Harvey J, Thompson C, Siber GR. 1995. Transplacental antibody transfer following maternal immunization with polysaccharide and conjugate Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccines. J. Infect. Dis. 171:99–105. 10.1093/infdis/171.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mulholland K, Suara RO, Siber G, Roberton D, Jaffar S, N′Jie J, Baden L, Thompson C, Anwaruddin R, Dinan L, Glezen WP, Francis N, Fritzell B, Greenwood BM. 1996. Maternal immunization with Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide-tetanus protein conjugate vaccine in The Gambia. JAMA 275:1182–1188. 10.1001/jama.275.15.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wesumperuma HL, Perera AJ, Pharoah PO, Hart CA. 1999. The influence of prematurity and low birthweight on transplacental antibody transfer in Sri Lanka. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 93:169–177. 10.1080/00034989958654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Moraes-Pinto MI, Farhat CK, Carbonare SB, Curti SP, Otsubo ME, Lazarotti DS, Campagnoli RC, Carneiro-Sampaio MM. 1993. Maternally acquired immunity in newborns from women infected by the human immunodeficiency virus. Acta Paediatr. 82:1034–1038. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1993.tb12805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cumberland P, Shulman CE, Maple PA, Bulmer JN, Dorman EK, Kawuondo K, Marsh K, Cutts FT. 2007. Maternal HIV infection and placental malaria reduce transplacental antibody transfer and tetanus antibody levels in newborns in Kenya. J. Infect. Dis. 196:550–557. 10.1086/519845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott S, Cumberland P, Shulman CE, Cousens S, Cohen BJ, Brown DW, Bulmer JN, Dorman EK, Kawuondo K, Marsh K, Cutts F. 2005. Neonatal measles immunity in rural Kenya: the influence of HIV and placental malaria infections on placental transfer of antibodies and levels of antibody in maternal and cord serum samples. J. Infect. Dis. 191:1854–1860. 10.1086/429963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Moraes-Pinto MI, Almeida AC, Kenj G, Filgueiras TE, Tobias W, Santos AM, Carneiro-Sampaio MM, Farhat CK, Milligan PJ, Johnson PM, Hart CA. 1996. Placental transfer and maternally acquired neonatal IgG immunity in human immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Infect. Dis. 173:1077–1084. 10.1093/infdis/173.5.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta A, Mathad JS, Yang WT, Singh HK, Gupte N, Mave V, Bharadwaj R, Zaman K, Roy E, Bollinger RC, Bhosale R, Steinhoff MC. 2014. Maternal pneumococcal capsular IgG antibodies and transplacental transfer are low in South Asian HIV-infected mother-infant pairs. Vaccine 32:1466–1472. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van den Berg JP, Westerbeek EA, van der Klis FR, Berbers GA, van Elburg RM. 2011. Transplacental transport of IgG antibodies to preterm infants: a review of the literature. Early Hum. Dev. 87:67–72. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simister NE. 2003. Placental transport of immunoglobulin G. Vaccine 21:3365–3369. 10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00334-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nahm MH, Glezen P, Englund J. 2003. The influence of maternal immunization on light chain response to Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine. Vaccine 21:3393–3397. 10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carson PJ, Schut RL, Simpson ML, O'Brien J, Janoff EN. 1995. Antibody class and subclass responses to pneumococcal polysaccharides following immunization of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. J. Infect. Dis. 172:340–345. 10.1093/infdis/172.2.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soininen A, Seppala I, Nieminen T, Eskola J, Kayhty H. 1999. IgG subclass distribution of antibodies after vaccination of adults with pneumococcal conjugate vaccines. Vaccine 17:1889–1897. 10.1016/S0264-410X(98)00475-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santosham M, Englund JA, McInnes P, Croll J, Thompson CM, Croll L, Glezen PW, Siber GR. 2001. Safety and antibody persistence following Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate or pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccines given before pregnancy in women of childbearing age and their infants. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 20:931–940. 10.1097/00006454-200110000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reikie BA, Naidoo S, Ruck CE, Slogrove AL, de Beer C, la Grange H, Adams RC, Ho K, Smolen K, Speert DP, Cotton MF, Preiser W, Esser M, Kollmann TR. 2013. Antibody responses to vaccination among South African HIV-exposed and unexposed uninfected infants during the first 2 years of life. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 20:33–38. 10.1128/CVI.00557-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rutstein RM, Rudy BJ, Cnaan A. 1996. Response of human immunodeficiency virus-exposed and -infected infants to Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 150:838–841. 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170330064011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asturias EJ, Mayorga C, Caffaro C, Ramirez P, Ram M, Verstraeten T, Clemens R, Halsey NA. 2009. Differences in the immune response to hepatitis B and Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccines in Guatemalan infants by ethnic group and nutritional status. Vaccine 27:3650–3654. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Metz JA, Hanieh S, Pradhan R, Joshi A, Shakya D, Shrestha L, Shrestha A, Upadhyay B, Kelly SC, John TM, Maharjan BD, Yu LM, Omar O, Borrow R, Findlow J, Kelly DF, Thorson SM, Adhikari N, Murdoch DR, Pollard AJ. 2012. Evaluation of Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine for routine immunization in Nepali infants. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 31:e66–72. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31824a9c37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Madhi SA, Kuwanda L, Saarinen L, Cutland C, Mothupi R, Kayhty H, Klugman KP. 2005. Immunogenicity and effectiveness of Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine in HIV infected and uninfected African children. Vaccine 23:5517–5525. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tregnaghi M, Lopez P, Rocha C, Rivera L, David M, Ruttimann PR, Schuerman L. 2006. A new DTPw-HB/Hib combination vaccine for primary and booster vaccination of infants in Latin America. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica 19:179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lagos R, Valenzuela MT, Levine OS, Losonsky GA, Erazo A, Wasserman SS, Levine MM. 1998. Economisation of vaccination against Haemophilus influenzae type b: a randomised trial of immunogenicity of fractional-dose and two-dose regimens. Lancet 351:1472–1476. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07456-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eskola J, Ward J, Dagan R, Goldblatt D, Zepp F, Siegrist CA. 1999. Combined vaccination of Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate and diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis containing acellular pertussis. Lancet 354:2063–2068. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heath PT, Booy R, Azzopardi HJ, Slack MP, Bowen-Morris J, Griffiths H, Ramsay ME, Deeks JJ, Moxon ER. 2000. Antibody concentration and clinical protection after Hib conjugate vaccination in the United Kingdom. JAMA 284:2334–2340. 10.1001/jama.284.18.2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kayhty H, Peltola H, Karanko V, Makela PH. 1983. The protective level of serum antibodies to the capsular polysaccharide of Haemophilus influenzae type b. J. Infect. Dis. 147:1100. 10.1093/infdis/147.6.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.World Health Organization. 2013. WHO position paper on Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccines. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/immunization/REH_47_8_pages.pdf Accessed 30 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gessner BD. 2009. Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine impact in resource-poor settings in Asia and Africa. Expert Rev. Vaccines 8:91–102. 10.1586/14760584.8.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murphy TV, Pastor P, Medley F, Osterholm MT, Granoff DM. 1983. Decreased Haemophilus colonization in children vaccinated with Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine. J. Pediatr. 122:517–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fitzwater SP, Watt JP, Levine OS, Santosham M. 2010. Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccines: considerations for vaccination schedules and implications for developing countries. Hum. Vaccin. 6:810–818. 10.4161/hv.6.10.13017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trotter CL, McVernon J, Ramsay ME, Whitney CG, Mulholland EK, Goldblatt D, Hombach J, Kieny MP, SAGE subgroup 2008. Optimising the use of conjugate vaccines to prevent disease caused by Haemophilus influenzae type b, Neisseria meningitidis and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Vaccine 26:4434–4445. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.