Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a dreaded pathogen in many clinical settings. Its inherent and acquired antibiotic resistance thwarts therapy. In particular, derepression of the AmpC β-lactamase is a common mechanism of β-lactam resistance among clinical isolates. The inducible expression of ampC is controlled by the global LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) AmpR. In the present study, we investigated the genetic and structural elements that are important for ampC induction. Specifically, the ampC (PampC) and ampR (PampR) promoters and the AmpR protein were characterized. The transcription start sites (TSSs) of the divergent transcripts were mapped using 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends-PCR (RACE-PCR), and strong σ54 and σ70 consensus sequences were identified at PampR and PampC, respectively. Sigma factor RpoN was found to negatively regulate ampR expression, possibly through promoter blocking. Deletion mapping revealed that the minimal PampC extends 98 bp upstream of the TSS. Gel shifts using membrane fractions showed that AmpR binds to PampC in vitro whereas in vivo binding was demonstrated using chromatin immunoprecipitation-quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR). Additionally, site-directed mutagenesis of the AmpR helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif identified residues critical for binding and function (Ser38 and Lys42) and critical for function but not binding (His39). Amino acids Gly102 and Asp135, previously implicated in the repression state of AmpR in the enterobacteria, were also shown to play a structural role in P. aeruginosa AmpR. Alkaline phosphatase fusion and shaving experiments suggest that AmpR is likely to be membrane associated. Lastly, an in vivo cross-linking study shows that AmpR dimerizes. In conclusion, a potential membrane-associated AmpR dimer regulates ampC expression by direct binding.

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a Gram-negative opportunistic pathogen, causes severe and life-threatening infections in susceptible individuals. This pathogen is primarily associated with morbidity and mortality in patients with cystic fibrosis, a deadly genetic disease (1). The bacterium's innate ability to counteract the action of antibiotics often complicates treatment strategies. Intrinsic resistance is conferred by its low membrane permeability, the expression of efflux pumps and hydrolyzing enzymes, the alteration of antimicrobial targets, and the ability to form biofilm (2–4). In particular, resistance to β-lactam antibiotics is mediated by the expression and overproduction of the chromosomally encoded class C β-lactamase AmpC (5–7).

Ambler class C β-lactamases were first described in members of the Enterobacteriaceae family where expression is either constitutively low or inducible (8–11). In species where expression is inducible, such as Citrobacter freundii and Enterobacter cloacae, the induction requires β-lactam challenge and the presence of the transcriptional regulator AmpR (8, 12–14). AmpR is a member of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators and as such is a DNA-binding protein with a predicted helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif at the N terminus and an inducer-binding domain at the C terminus (15, 16). Comprehensive studies in the Enterobacteriaceae have established the critical role of AmpR as the regulator of ampC expression and the paradigm of β-lactamase induction.

In the Enterobacteriaceae, ampC inducibility is intimately linked to the recycling of the peptidoglycan (PG) of the murein sacculus (17–20). During normal physiological growth, N-acetylglucosaminyl-1,6-anhydromuropeptides (GlcNAc-1,6-anhydro-MurNAc tri-, tetra-, and pentapeptides) are continuously being released from the murein sacculus due to remodeling (17, 18). The permease, AmpG, transports the metabolites into the cytoplasm, where the glycosidase NagZ removes the GlcNAc moiety and the amidase AmpD removes the stem peptides either from the incoming GlcNAc-1,6-anhydro-MurNAc peptides or from the NagZ-processed product (18, 21–26). The resulting muramyl peptides are recycled back into the PG biosynthetic pathway to form the PG precursor UDP-MurNAc-pentapeptide (27). It has been proposed that during normal cell growth, the cytosolic concentrations of UDP-MurNAc-pentapeptide maintain AmpR in an inactive conformation that represses the expression of ampC (17, 18). In the presence of β-lactams, however, there is an excessive breakdown of murein leading to accumulation of 1,6-anhydromuropeptides in the cytoplasm, which in turn overwhelm the hydrolytic activity of AmpD (17, 18, 28, 29). The increased number of AmpD-unprocessed muramyl peptides presumably displaces the repressor UDP-MurNAc-pentapeptide from AmpR and induces a conformational change in the protein to promote expression of ampC (17, 28, 29).

All amp gene homologs (ampC, ampR, ampD, and ampG) have been identified and studied in P. aeruginosa (30–37). Whether a similar induction mechanism is employed by P. aeruginosa is not yet known; however, recent work illustrates significant departures from the classical enterobacterial induction system. In particular, there are three ampD homologs in P. aeruginosa that are responsible for a stepwise upregulation mechanism leading to constitutive β-lactamase hyperexpression (2, 3, 30, 32). Additionally, P. aeruginosa harbors two AmpG homologs, PA4218 (AmpP) and PA4393 (AmpG), which appear to be required for induction of ampC (36, 38). Further, our lab has shown that P. aeruginosa AmpR is a global transcriptional regulator involved in the control of amp and various other genes (31, 39–41).

AmpR exhibits high sequence identity with its counterparts in C. freundii and E. cloacae, and as in the Enterobacteriaceae, ampR is located immediately upstream of ampC and divergently transcribed (34, 35). Such similarities suggest a common regulatory mechanism among the species; however, the P. aeruginosa ampR-ampC intercistronic region bears little resemblance to that of the enterobacteria. In vitro studies using crude extracts have shown that P. aeruginosa AmpR binds to this region, but the exact binding site and the identity of the amino acids involved in the interaction have not yet been determined (34). In essence, not much is known about the structural elements that are critical to the functioning of P. aeruginosa AmpR as a regulator of β-lactamase expression.

In the present work, we define some of the genetic elements in the ampR-ampC intergenic region, including the ampR and ampC transcriptional start sites, as well as the minimal length of the ampC promoter needed for induction of the ampC system. We further show that AmpR specifically binds to a 193-bp PampC fragment identified by promoter mapping as being required for induction. We also identify amino acids in the AmpR HTH motif that are critical for the interaction with the promoter. Additionally, we examine the role of two amino acids, Gly102 and Asp135, previously implicated in the repression state of AmpR from the Enterobacteriaceae. Lastly, we show that P. aeruginosa AmpR likely functions as a dimer, as previously seen for C. freundii, and is potentially a membrane protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers employed in this study are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Escherichia coli and P. aeruginosa were routinely cultured in Luria-Bertani medium (LB; 10 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, and 5 g NaCl, per liter). Pseudomonas isolation agar (Difco) was used with LB at a 1:1 ratio in triparental mating experiments. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations (per milliliter): ampicillin (Ap) at 100 μg, tetracycline (Tc) at 15 μg, and gentamicin (Gm) at 15 μg for E. coli; Gm and Tc each at 75 μg for P. aeruginosa. PA0ΔampC and PA0ΔampR strains used in this work were previously constructed using overlap extension PCR and homologous recombination (40, 42).

PampC promoter deletions.

To characterize the minimal promoter necessary for full activity, 5′-end deletions of PampC were constructed and transcriptionally fused to a promoterless lacZ. Briefly, 352-, 193-, 171-, 151-, 130-, 111-, 90-, 70-, and 51-bp fragments were generated by PCR with the following primer pairs, respectively: SBJ03ampCRFor-OCPampCRevBc, OCPampCFor193-OCPampCRevBc, OCPampCFor173-OCPampCRevBc, OCPampCFor151-OCPampCRevBc, OCPampCFor131-OCPampCRevBc, OCPampCFor111-OCPampCRevBc, OCPampCFor91-OCPampCRevBc, OCPampCFor71-OCPampCRevBc, and OCPampCFor51-OCPampCRevBc (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The fragments were sequenced and then cloned into the EcoRI-BamHI sites of the integrative vector mini-CTX-lacZ and integrated into PAO1.

Construction of His-tagged AmpR.

Primers OCAmpR-His-For and OCAmpR-His-Rev (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) were used to amplify PAO1 genomic ampR. The 933-bp amplicon, carrying a His6 sequence at the 3′ end, was cloned into pBluescriptSK(+) and sequenced (see Table S1). The fragment was subsequently subcloned into the EcoRI-BamHI sites of pMMB67EH-Gm, a broad-host-range expression vector (43). His-tagged AmpR was shown to be functional by β-lactamase assay and Etest (see Text S1 and Table S2).

Expression and purification of AmpR-His6.

AmpR-His6 was purified according to standard protocols. Briefly, stationary-phase cultures of PA0ΔampR (pAmpR-His6) were diluted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.02 in 2 liters of LB broth and incubated with shaking at 37°C until the culture density reached an OD600 of 0.2. Cells were then induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and incubated for an additional 6 h before harvesting. The cells were recovered by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C and resuspended in 25 ml of lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 8, 0.5 M NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], 2 pellets of EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablets [complete], 100 μl of 0.1 mg ml−1 of lysozyme, and 5 μl of DNase I). Following disruption of the cells on ice with sonication (20-s pulse on and 20-s pulse off for 20 min; amplitude, 50%), the cell lysate was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was further ultracentrifuged at 36,000 rpm for 1 h at 4°C. Membrane pellets were resuspended in 20 ml of solubilization buffer {20 mM HEPES, pH 8, 0.5 M NaCl, 10% glycerol, 5 mM imidazole, 1 mM PMSF, 2 pellets of EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (complete), and 2% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS)} and loaded onto a HisTrap FF 1-ml column. AmpR-His6 was eluted with buffer B (20 mM HEPES, pH 8, 0.5 M NaCl, 10% glycerol, 500 mM imidazole, and 0.6% CHAPS) by using a fast protein liquid chromatograph (FPLC) (Akta; Amersham Biosciences). About 20 ml was recovered and dialyzed to remove imidazole. This AmpR preparation was used to make AmpR-specific antibodies.

Construction of P. aeruginosa AmpR HTH and point mutants.

Site-directed mutagenesis was used to replace various amino acid residues in AmpR. Briefly, Ser38, His39, Lys42, Ser43, and Glu46 were replaced with Ala; Gly102 and Asp135 were replaced with Glu and Asn, respectively. Substitutions were constructed by PCR using the following primer pairs: AmpRSer38AlaFor-AmpRSer38AlaRev, zAmpRHis39AlaFor-AmpRHis39AlaRev, AmpRLys42AlaFor-AmpRLys42AlaRev, AmpRSer43AlaFor-AmpRSer43AlaRev, AmpRGlu46AlaFor-AmpRGlu46AlaRev, AmpRGly102GluFor-AmpRGly102GluRev, and AmpRAsp135AsnFor-AmpRAsp135AsnRev (see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

Membrane fraction purification.

Preliminary studies showed that pAmpR-His6 expression and β-lactamase induction were achieved with a 2-hour incubation at a 1 mM IPTG concentration. Thus, PA0ΔampR (pAmpR-His6) cells at an OD600 of 0.2 were induced with 1 mM IPTG and incubated for 2 h before harvesting for membrane fractionation. For β-lactamase induction, cells were further treated with 200 μg ml−1 of penicillin G an hour after IPTG addition. Cells were recovered by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C and resuspended in 50 ml of lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 8, 0.1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, and 50 μl of DNase I). Following disruption of the cells on ice with sonication (15 cycles of 10-s pulse on and 30-s pulse off; amplitude, 40%), the cell lysate was centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was ultracentrifuged at 36,000 rpm (Ti70 rotor) for 1 h at 4°C, and the pellets were resuspended with 2 ml of membrane buffer (25% sucrose, 20 mM Tris, pH 8, and 0.5 mM PMSF). Two hundred milliliters of membrane fractions was aliquoted and stored at −80°C.

EMSA.

The 193-bp PCR fragment containing the ampR-ampC intergenic region plus a small part of the ampR open reading frame (ORF) was used to perform an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). Ten picomoles of this fragment was radiolabeled at the 5′ end by incubation with T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB) and [γ-32P]ATP (3,000 Ci mmol−1; PerkinElmer). The labeled fragment was diluted to a final concentration of 100 nM, and unincorporated nucleotides were removed by Sephadex G-25 (Bio-Rad) spin chromatography. DNA-binding reaction mixtures containing 50 fmol of 32P-labeled DNA probe and various amounts of total protein membrane fractions were incubated for 20 min and loaded thereafter in a nondenaturing 5% PAGE gel. Radioactive signals were detected by scanning a phosphostorage cassette with the GE Healthcare Typhoon 9400 scanner.

For competition assays, 50 fmol of the 193-bp 32P-labeled probe was mixed with the unlabeled 193-bp fragment in 10-, 100-, and 500-fold molar excess in the EMSA. For nonspecific assays, 50 fmol of the 193-bp 32P-labeled probe was mixed with a PCR-amplified 233-bp fragment (alg44) in 10-, 100-, and 500-fold molar excess in the EMSA.

5′ RACE-PCR.

The ampC and ampR transcription start sites (TSSs) were mapped using a classical 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends-PCR (RACE-PCR) on total mRNAs extracted from PAO1, PA0ΔampR, and PA0ΔampC (44). Stationary-phase cultures of PAO1, PA0ΔampR, and PA0ΔampC were diluted to an OD600 of 0.02 and incubated with shaking at 37°C until the cultures reached an OD600 of 0.6. The cultures were then induced with 200 μg ml−1 of penicillin G for 1 h and subsequently blocked on ice for 15 min with 1/5 of the final culture volume in 5% acidic phenol-95% ethanol, pH 4. One milliliter of the cells was recovered by centrifugation and resuspended with 3 mg ml−1 of lysozyme (Tris-EDTA, pH 8). RNA was then extracted according to the RNeasy minikit protocol (Qiagen), treated with 10 U of RQ1 DNase (Promega) for 1 h, extracted with phenol-chloroform–isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and chloroform, precipitated, and dried. Superscript III (Invitrogen) was then used to reverse transcribe 10 μg of RNA as previously described (44) using primers 5RA-PampC233 and 5RA-PampR229 for determination of the ampC and ampR TSSs, respectively. In the first round of PCR amplification (Pfu; Stratagene), primers Qt, Q0, and 5RA-PampC154 were used for ampC TSS determination, while Qt, Q0, and 5RA-PampR169 were used for determination of the ampR TSS. In the second round of PCR amplification (Pfu; Stratagene), primer pairs Qi-5RA-PampC113 and Qi-5RA-PampR99 were used for ampC and ampR TSS determination, respectively (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). PCR products were cloned into TOPO (Invitrogen), blue colonies were selected for screening, and clones were sequenced.

qPCR analysis of ampR and ampC mRNAs.

Total RNA was extracted from PAO1, PA0ΔrpoN, and PA0ΔrpoN (pRpoN) in the presence and absence of the inducer (0.2 μg ml−1 imipenem) using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen). RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA with Superscript III (Invitrogen) and an (NS)5 random primer using standard methods (45). For quantitative PCR (qPCR), the ABI 7500 (Applied Biosystems) cycler was used with Power SYBR green PCR master mix with ROX (Applied Biosystems). The reading was normalized to clpX (PA1802), whose expression remains constant in all the samples and under all the conditions tested. Melting curves were generated to ensure primer specificity. Gene expression of each sample was normalized to the PAO1 uninduced value, to see the effect of induction and mutation at the same time. Primer pairs DBS_QRTAmpRFwd-DBS_QRTAmpRRev and qRT_ampCF-qRT_ampCR were used for the real-time amplification of ampR and ampC, respectively.

Construction of VSV-G-tagged AmpR.

A 540-bp fragment corresponding to the 3′ end of ampR, minus the stop codon, was amplified using primers DB_ampR3′_F and DB_ampR3′_R. The amplicon was cloned into pP30ΔFRT-MvaT-V (46), a replication-incompetent vector in P. aeruginosa, such that the 3′ end of ampR was fused in frame with three alanines and the vesicular stomatitis virus G protein (VSV-G) tag (YTDIEMNRLGK). The construct was then was introduced into PAO1 as a single copy by mating, and clones were selected for gentamicin resistance.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation-quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR).

Cells harboring the VSV-G-tagged AmpR were harvested after sub-MIC β-lactam exposure (40) and treated with formaldehyde to cross-link proteins with DNA as previously described (46). DNA was sheared by sonication to an average length of 0.5 to 1.0 kb, and AmpR was immunoprecipitated with anti-VSV-G–agarose beads (Bethyl Laboratories, Inc.). ChIP-qPCR was performed using Power SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) with primers DBS_ChIP_ampCF and DBS_ChIP_ampCR. Fold enrichment was normalized to clpX (PA1802).

Protein cross-linking.

PA0ΔampR (pAmpR-His6) was grown to an OD600 of 0.3 and induced with 1 mM IPTG for 2 h. Cells were grown for 2 additional hours in the presence and absence of β-lactam antibiotics (0.1 μg ml−1 of imipenem). Cultures were then treated with 0.1% formaldehyde for 20 and 40 min at room temperature. Crude extracts containing 10 μg of total protein were separated on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and AmpR was visualized using anti-His antibody. The blot was subsequently stripped and reprobed using anti-σ70 antibody (NeoClone).

Polyclonal anti-AmpR-His6 antibody production.

Purified AmpR-His6 was used as antigen to raise anti-AmpR-His6 rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Covance, Princeton, NJ). AmpR-His6 antibody was affinity purified as previously described (47).

Western blotting and EMSA of HTH mutants.

The concentration of purified AmpR-His6 was determined by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method (48). A calibration Western blot was generated using a FujiFilm LAS-3000 imager to correlate intensities with the concentration of purified AmpR-His6. Membrane fractions were purified from PA0ΔampR pAmpR HTH mutants, and their concentrations were determined using the BCA method, whereas the exact quantity of AmpR was deduced from Western blotting. Preliminary gel shifts with increasing concentrations of membrane fractions of AmpR HTH mutants showed that 0.4 mg ml−1 is sufficient to shift the 193-bp PampC PCR fragment (data not shown). For a second gel shift, 0.4 mg ml−1 of total membrane fraction (8.44 ng of AmpR), recovered from PA0ΔampR overexpressing AmpR HTH mutants in the presence and absence of 200 μg ml−1 penicillin G, was hybridized with the 193-bp PCR fragment spanning the ampC-ampR intergenic region (see Fig. 7). As this concentration was not enough to visualize AmpR, a higher quantity (33 ng) was used for Western blotting of the HTH mutants to show that the amount of AmpR-His6 is equivalent under all conditions and thus in the EMSA (data not shown). Further, the stability of AmpR-His6 mutants was verified by Western blotting using equal amounts of total protein with AmpR-specific antibodies (see Fig. 8). Sigma70 (NeoClone) was used as a control to show that the same amount of total protein was loaded per sample. All Western blots were developed according to standard protocols. Briefly, proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Bio-Rad) and blocked with TBST (Tris-buffered saline–0.1% Tween) and 5% nonfat dry milk at 4°C overnight or for 4 h, followed by rinsing with the same solution and probing with rabbit anti-AmpR antibody (1:3,000). Membranes were subsequently washed with TBST, incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG (heavy plus light chain [H+L])–horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (1:5,000) (Bio-Rad), rinsed, and developed using enhanced chemiluminescence Western blotting substrate (Pierce).

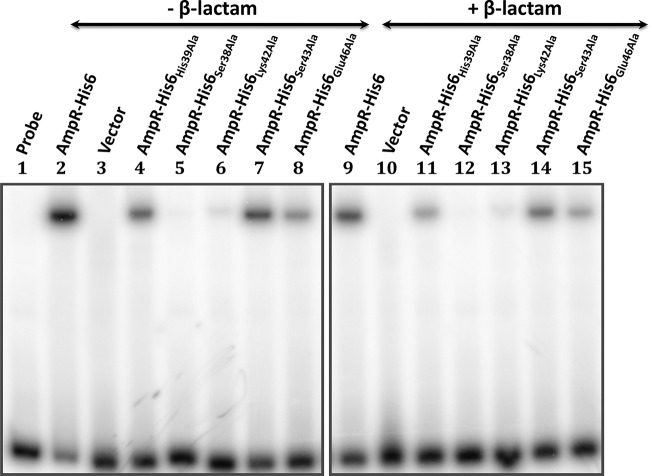

FIG 7.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay of P. aeruginosa AmpR HTH mutants. A 50-fmol amount of the 193-bp radiolabeled PampC fragment (lane 1) was mixed with membrane fractions recovered from PA0ΔampR in the absence (lanes 2 to 8) and presence (lanes 9 to 15) of β-lactams and carrying pMMB67EH-Gm (lanes 3 and 10), pAmpR-His6 (lanes 2 and 9), pAmpR-His6(His39Ala) (lanes 4 and 11), pAmpR-His6(Ser38Ala) (lanes 5 and 12), pAmpR-His6(Lys42Ala) (lanes 6 and 13), pAmpR-His6(Ser43Ala) (lanes 7 and 14), and pAmpR-His6(Glu46Ala) (lanes 8 and 15).

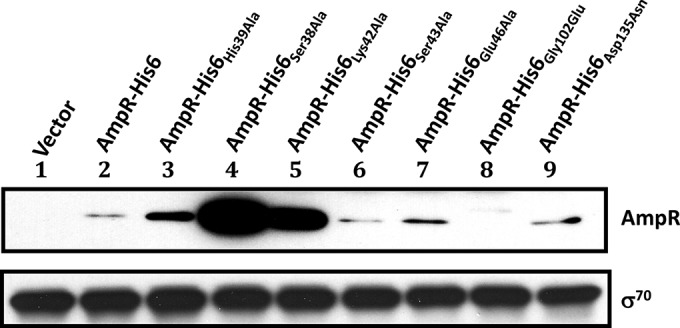

FIG 8.

Stability of P. aeruginosa AmpR mutant proteins. Total protein extracts were recovered from AmpR HTH and point mutants after a 1.5-hour incubation with 1 mM IPTG. The stability of each mutant was verified by Western blotting using AmpR-specific antibodies. Equal amounts of total membrane protein were loaded per well; σ70 was used as a loading control and detected with anti-σ70 antibody.

β-Galactosidase assay.

β-Galactosidase assays were performed as previously described (49).

AmpR-LacZ and -PhoA fusion construction and analysis.

The topology of AmpR was investigated using phoA and lacZ fusions. The plasmid pSJ01 (31), carrying a 1,220-bp fragment containing ampR, was digested at HindIII, HincII, and PstI, corresponding to the amino acid positions Gln15, Val134, and Gln186, respectively (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). The resultant fragments were ligated in frame upstream of phoA- and lacZ-containing plasmids, pTrcphoA and pTrclacZ, respectively (see Table S1) (50). The phoA and lacZ activities were qualitatively determined in E. coli according to standard protocols (49).

Protease protection (shaving) assay.

A stationary-phase culture of PA0ΔampR (pAmpR-His6) was diluted to an OD600 of 0.02 and incubated with shaking at 37°C until the culture reached an OD600 of 0.4. The cells were then induced with 1 mM IPTG for 4 h, and chloramphenicol (500 μg ml−1) was added 30 min prior to harvesting to stop protein synthesis. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 40 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 0.5 M sucrose. Spheroplasts were obtained by adding 1 mg ml−1 of lysozyme and 4 mM EDTA for 10 min in a 30°C water bath followed by the addition of 20 mM MgCl2. The formation of spheroplasts was monitored by light microscopy. Spheroplasts were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 10 min and resuspended in 40 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 0.5 M sucrose. Proteinase K (10 μg ml−1) was added to a 1-ml aliquot of the spheroplasts and incubated in a 30°C water bath. Samples were taken at different time points and added to 2 mM PMSF and 4× SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Samples were then boiled for 5 min and run in a 4 to 20% SDS-PAGE gel (Criterion; Bio-Rad). Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad) and identified using AmpR (Covance), σ70 (NeoClone), and His tag (Qiagen) antibodies. The immunoblot was developed using SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Analysis of the P. aeruginosa ampC-ampR regulatory region.

P. aeruginosa AmpR shares high identity with its homologs in C. freundii and E. cloacae (58.3 and 62.5%, respectively), as well as the same gene organization, with ampR located upstream of ampC and divergently transcribed (34, 35). The P. aeruginosa ampR-ampC intercistronic region, however, shares no significant similarities with those of C. freundii and E. cloacae, with the exception of an inverted 38-bp sequence that in C. freundii is protected by AmpR (35, 51). The lack of conservation in the promoter region could point to different sigma factor requirements and/or different regulatory mechanisms. To elucidate the transcriptional regulatory elements of P. aeruginosa ampC and ampR, their 148-bp intergenic region was characterized.

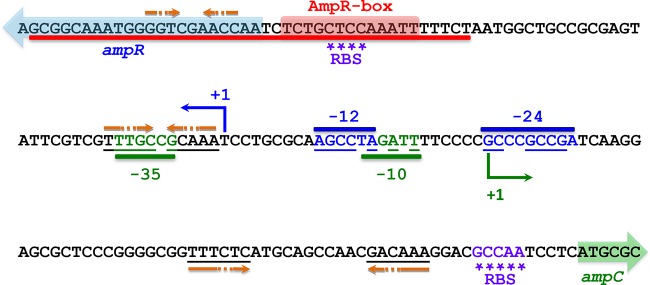

The transcription start sites (TSSs) were determined using 5′ RACE-PCR on total mRNAs isolated from PAO1, PA0ΔampR, and PA0ΔampC (Fig. 1). A strong similarity to RpoN (σ54) sigma factor sequences was detected at the −12 and −24 positions of the ampR TSS, whereas strong σ70 promoter sequences were observed at the −10 and −35 positions of ampC. Alignment of the C. freundii, E. cloacae, and P. aeruginosa intergenic regions reveals fair conservation of the ampC −10 and −35 sequences. However, there is a downstream shift in the P. aeruginosa ampR TSS that could contribute to the change in sigma factor control observed here (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG 1.

Intergenic region of P. aeruginosa ampC and ampR. A 148-bp region separates ampR from ampC. The ampR and ampC transcriptional start sites are indicated with a blue and green +1, respectively, whereas the colored arrows designate the beginning of the ORFs. Strong σ54 (blue) and σ70 (green) sequences are observed in the ampR and ampC promoter regions, respectively. The underlined bases correspond to conserved sequences. The Shine-Dalgarno sequences or ribosome binding sites (RBSs) are marked by asterisks. A putative AmpR-binding site was identified based on sequence homology and is indicated by the AmpR box. Orange arrows denote palindromic sequences in close proximity to the ampC and ampR RBSs indicative of hairpin formation for regulating translation through blocking of ribosome binding.

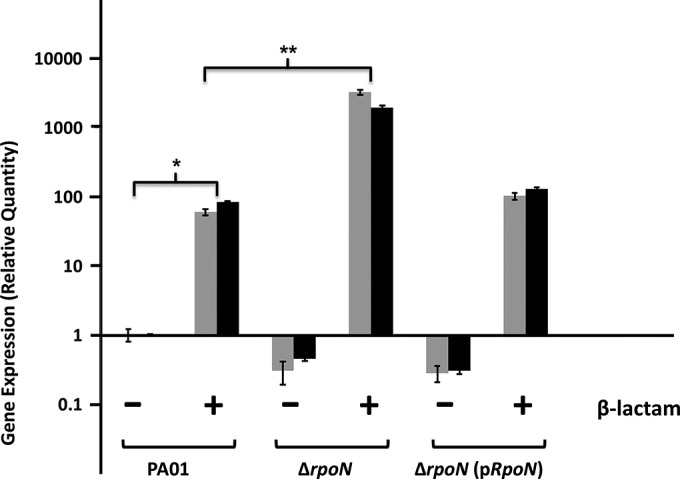

The presence of putative −12 and −24 recognition sequences in the ampR promoter (PampR) suggested that its expression might be RpoN or σ54 dependent. Quantitative real-time PCR was used to validate this hypothesis. Total RNA was extracted from β-lactam-induced and uninduced PAO1, PA0ΔrpoN, and PA0ΔrpoN (pRpoN) strains and reverse transcribed into cDNA using standard methods (45). In the wild type, exposure to β-lactams increased ampR and ampC expression approximately 100-fold over that in the uninduced samples (normalized to 1) (Fig. 2). A further, significant increase in expression of both genes was observed in PA0ΔrpoN upon β-lactam challenge that could be rescued by pRpoN. In the absence of β-lactams, a small but significant reduction in expression was observed in PA0ΔrpoN that could not be complemented.

FIG 2.

RpoN downregulates P. aeruginosa ampR expression in the presence of β-lactams. RNA was isolated from PAO1, PA0ΔrpoN, and PA0ΔrpoN(pRpoN) in the presence and absence of β-lactams, reverse transcribed to cDNA, and tested by qPCR with ampC (gray bars)- and ampR (black bars)-specific primers, as described in Materials and Methods. Values were normalized to the expression of the wild-type uninduced sample and represent the mean (±standard deviation) of two experiments conducted in triplicate. *, P value < 0.001 for both ampR and ampC expression in induced PAO1 versus expression in uninduced PAO1; **, P value < 0.005 for ampR and ampC expression in induced PA0ΔrpoN versus expression in induced PAO1 as determined by unpaired t test.

In spite of the presence of a probable binding site on PampR, σ54 is not required for ampR expression. The significant increase in the absence of rpoN and in the presence of the β-lactams suggests that σ54 negatively impacts ampR expression. RpoN may exert this negative effect indirectly by enabling transcription of a negative regulator or directly by competing for the RNA polymerase holoenzyme with another sigma factor. Alternatively, P. aeruginosa RpoN can directly repress transcription by blocking promoter access to a different sigma factor in a phenomenon referred to as σ-factor antagonism, as previously reported (52). Specifically, σ54 has been shown to repress σ22-dependent transcription from PalgD by directly binding to the overlapping promoter sequences in the absence of an external stimulus (52). Similarly, σ-factor antagonism has also been reported in E. coli, where mutagenesis of a σ54-dependent promoter created a new TSS with a σ70 requirement that exhibited decreased transcriptional activity in the presence of σ54 (53).

A model of repression by σ54 through promoter blocking is conceivable, where in the absence of some external stimuli, in this case β-lactams, σ54 binds PampR and prevents access and thus transcription by the sigma factor. In the presence of the inducer, however, σ54 may be partially or completely displaced by the sigma-RNA polymerase complex to promote ampR transcription. Thus, the loss of rpoN leads to complete derepression of ampR expression under the induced condition.

Lastly and very interestingly, the expression of ampC followed a pattern similar to that of ampR in all backgrounds. Previously, ampR expression in P. aeruginosa was shown to be low and not significantly induced upon exposure to the β-lactam benzylpenicillin (31). Similarly, expression from the C. freundii ampR promoter in E. coli was found to be constitutive in the presence and absence of the inducer (6-aminopenicillanic acid) (51). In E. cloacae, induction with cefoxitin significantly increased transcription of ampC but had no effect on ampR expression (12). Recent work from our lab, however, showed that in the presence of very powerful known inducers, namely, imipenem and meropenem, expression of both ampC and ampR is equally and very significantly induced in wild-type P. aeruginosa (42). In light of such results, it is not surprising that our current data show that wild-type P. aeruginosa has similar ampC and ampR mRNA levels in the presence of imipenem. Similar induction profiles in the absence of rpoN suggest that the ampC and ampR promoters can reach their full induction potential upon removal of the restricting negative effect imposed by RpoN. It is not clear how exactly RpoN, or its absence, can accomplish this, but it is worth noting that in the ampC and ampR TSSs, the −12 sequence of ampR overlaps the −10 sequence of ampC. Thus, if σ54 is in fact blocking promoter access to RNA polymerase, it could be blocking access to both the ampR and ampC promoters until such time as inducers lead to its partial or complete displacement from the intergenic region. Further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanism of ampC and ampR downregulation by RpoN.

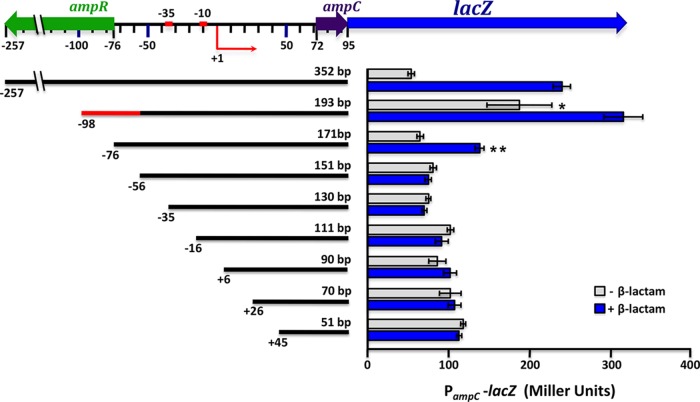

Mapping of P. aeruginosa PampC.

To map the minimal promoter needed for AmpR-dependent activity, a series of 5′-end deletions of PampC were transcriptionally fused to the promoterless lacZ gene of the integrative vector mini-CTX-lacZ (54). The activity of each promoter deletion was then analyzed in PAO1 by assaying β-galactosidase activity in the presence and absence of 200 μg ml−1 of penicillin G. The minimum length of the promoter needed for full PampC activity is 193 bp (Fig. 3). This fragment consists of the full ampR-ampC intergenic region plus small parts of the ampR (22-bp) and ampC (23-bp) ORFs. The high activity seen with the 193-bp fragment in the absence of β-lactams compared to the wild type may be the result of the partial or complete removal of the repressor-binding site. Subsequent loss of a 22-bp ampR fragment from the 5′ end of the 193-bp segment resulted in a 2-fold decrease in induction, likely indicating partial removal of the activator-binding site. This 22-bp fragment corresponding to the beginning of the ampR ORF seems to be necessary for full induction of PampC. In silico analysis reveals that this segment is very well conserved among other species but has no real identifiable features. Induction was abolished with a further 20-bp deletion (151-bp fragment). Thus, the 42-bp region (shown in red in Fig. 1 and 3), present at the 5′ end of the 193-bp fragment but deleted from the 151-bp construct, demarcates the outer bounds of the functional promoter needed for activation of PampC. Since this 42-bp fragment includes the AmpR box, an in silico-derived putative AmpR-binding site (Fig. 1), this region could be critical for activator binding.

FIG 3.

Mapping of the minimal P. aeruginosa ampC promoter. 5′-end deletions of PampC were constructed and transcriptionally fused to a promoterless lacZ gene in the integrative vector mini-CTX-lacZ as described in Materials and Methods. Constructs were introduced into PAO1 for integration at the attB site to generate single-copy promoter fusions. Promoter activities are expressed in Miller units. The +1 denotes the ampC transcriptional start site. The 42-bp segment, missing from the 151-bp construct, which appears to be necessary for activator binding is depicted in red at the 5′ end of the 193-bp fragment. *, P value < 0.05 compared to uninduced PA0attB::PampC352-lacZ; **, P value < 0.05 versus uninduced PA0attB::PampC171-lacZ as determined by unpaired t test using analysis of variance.

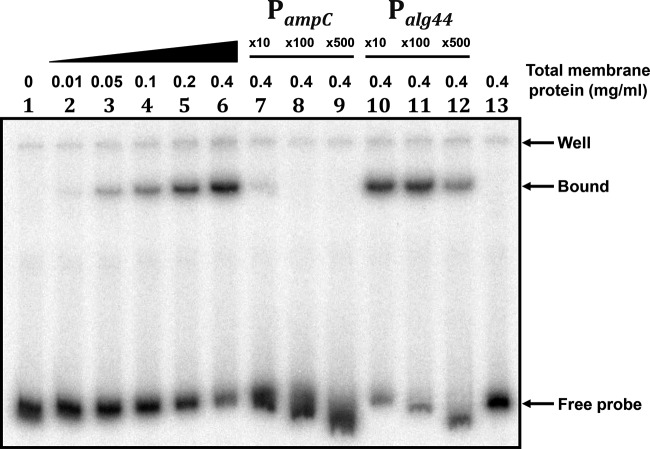

P. aeruginosa AmpR binds to PampC.

Previously, P. aeruginosa AmpR has been shown to bind PampC using AmpR-overexpressing E. coli whole-cell extracts (34). Similarly, crude preparations of C. freundii AmpR were also shown to retard a radiolabeled ampR-ampC intergenic region (51). Since preliminary work from our lab suggested that P. aeruginosa AmpR is likely to be a membrane-associated protein (see “Localization studies of P. aeruginosa AmpR” below and also Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), we tested the ability of PAO1 membrane fractions to bind PampC. EMSA was performed using AmpR-His6-enriched membrane fractions and a [γ-32P]ATP-radiolabeled PampC fragment. Shift was observed with increasing concentrations of total membrane protein up to 0.4 mg ml−1 (Fig. 4). The binding was competed out by mixing labeled DNA with unlabeled promoter DNA in a 100-fold molar excess, confirming AmpR binding to PampC (Fig. 4). Additionally, competition with a nonspecific, unlabeled fragment (233-bp alg44 PCR fragment) mixed in 10-, 100-, and 500-fold molar excess with the labeled PampC fragment failed to displace AmpR-His6 from PampC, illustrating the binding specificity.

FIG 4.

P. aeruginosa AmpR binds PampC. Fifty femtomoles of a 193-bp radiolabeled PampC fragment (lane 1) spanning the ampC-ampR promoter region was mixed with increasing concentrations of AmpR-His6-enriched membrane fractions extracted from PA0ΔampR(pAmpR-His6) in the presence of 200 μg ml−1 of penicillin G (lanes 2 to 6). Competition assays were carried out with the cold PampC fragment in 10- (lane 7), 100- (lane 8), and 500-fold (lane 9) molar excess. To characterize the binding specificity, a nonspecific fragment (233-bp alg44 PCR fragment) was mixed in 10- (lane 10), 100- (lane 11), and 500-fold (lane 12) molar excess with the radiolabeled reaction mix. Lane 13 is the control showing the 193-bp radiolabeled PampC fragment in the presence of membrane fractions extracted from PA0ΔampR containing the plasmid backbone alone.

To determine if AmpR interacts with PampC in vivo, ChIP-qPCR was employed (46). A functional VSV-G-tagged AmpR (see Table S3 in the supplemental material) was introduced into PAO1 as a single copy and then immunoprecipitated with anti-VSV-G antibody. Sequence-specific primers were used to detect the presence of PampC DNA with qPCR. Promoter occupancy was detected in the presence and absence of β-lactams as expected of LysR-type transcriptional regulators (LTTRs) (16) (fold enrichment over clpX control: uninduced, 10.6 ± 1.73; induced, 13.3 ± 4.63; fold enrichment for negative-control target aprX: uninduced, 1.30 ± 0.02; induced, 1.34 ± 0.22). AmpR thus binds PampC in vivo in the presence and absence of the inducer.

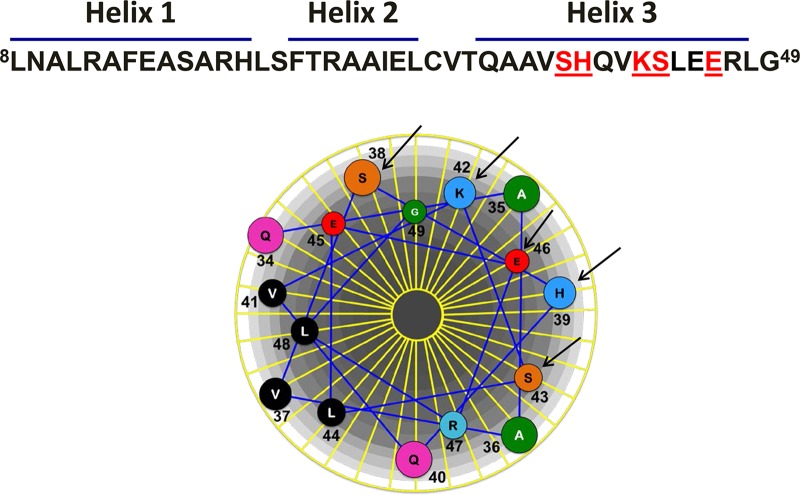

HTH is important for AmpR function.

The majority of prokaryotic DNA-binding proteins, including LTTRs, use the HTH motif to interact with DNA (15, 55). In LTTRs, this domain is often found at the N terminus (15, 16). The canonical HTH motif is comprised of three helical bundles, where the second and third helices interact with the DNA and the third makes the essential contacts with the major groove to provide recognition (15, 55, 56). A multiple alignment of the AmpR family HTH motif shows that the highest degree of conservation is found in the first two helices, with the most variation in the third helix that provides specificity (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Although P. aeruginosa AmpR has been shown to bind the ampR-ampC intercistronic region (34), the amino acids involved in the interaction have not been identified.

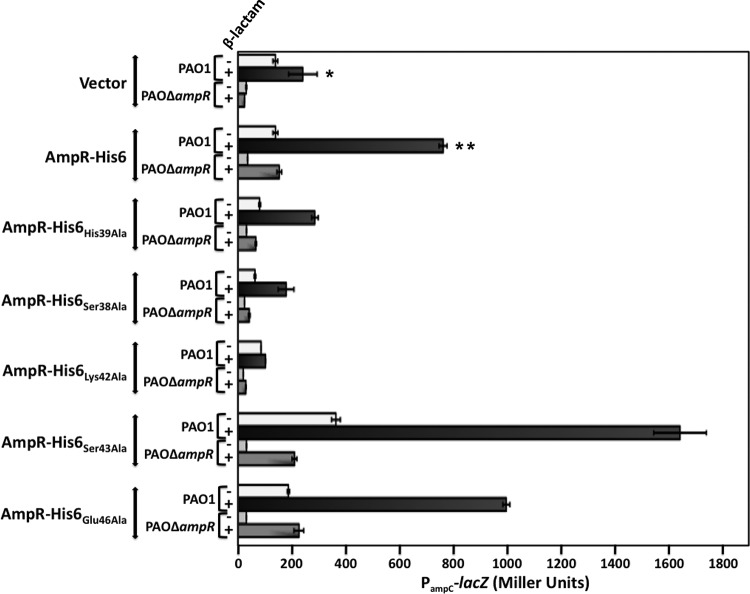

An amphipathic wheel of the third helix (residues Gln34 to Leu48), generated using DNAStar Protean, identified polar and charged amino acids potentially facing the major groove of the DNA (Fig. 5). Point mutations corresponding to these residues were generated by site-directed mutagenesis of AmpR-His6. Residues Ser38, His39, Lys42, Ser43, and Glu46 were thus replaced with alanine, and the mutants were overexpressed in PAO1 and PA0ΔampR strains carrying the chromosomal PampC-lacZ fusion (Fig. 6). The PampC activity observed in PAO1 is the result of both ampR alleles, from the chromosome (ampRchr) and from the plasmid (ampRpls), whereas in PA0ΔampR only ampRpls contributes.

FIG 5.

Analysis of the third helix of the P. aeruginosa AmpR HTH motif. An amphipathic wheel of the third helix (residues Q34 to L48) was generated using DNAStar Protean in order to identify polar and charged amino acids likely facing the major groove of the DNA. The AmpR residues Ser38, His39, Lys42, Ser43, and Glu46 were identified as amino acids likely to interact with the DNA and were thus targeted for mutagenesis. They are indicated by the arrows and denoted as S38, H39, K42, S43, and E46 in the helical wheel, respectively. The N-terminal sequence of P. aeruginosa AmpR illustrates the HTH motif and the location of the above amino acids (in red) in the third helix of AmpR.

FIG 6.

Functional analysis of the P. aeruginosa AmpR HTH motif. Site-directed mutagenesis was used to replace Ser38, His39, Lys42, Ser43, and Glu46 with Ala in AmpR-His6. The mutant proteins were overexpressed in PAO1 and PA0ΔampR strains carrying a single copy of the PampC-lacZ fusion integrated at the attB site. β-Galactosidase activity was quantified in the presence and absence of β-lactams. *, P value < 0.05 versus uninduced PAO1 vector control; **, P value < 0.005 versus induced PAO1 vector control as determined by unpaired t test using analysis of variance.

Alanine substitutions at Ser43 and Glu46 did not affect the ability of AmpR to activate PampC in PA0ΔampR (Fig. 6). In addition, both AmpRSer43Ala and AmpRGlu46Ala were able to bind PampC in the presence and absence of β-lactams (Fig. 7). These two findings suggest that Ser43 and Glu46 are not critical for AmpR function. However, expression of AmpRSer43Ala and AmpRGlu46Ala in PAO1 that carries AmpRchr significantly increased PampC activity by more than 2-fold in the presence of inducers, suggesting a possible interaction between chromosome-encoded AmpRchr and the variants (Fig. 6). In particular, the Ser43Ala substitution increased basal levels in the absence of inducers while leading to hyperinduction in the presence of β-lactams. Similarly, significant activation of PampC in PAO1 in the presence of AmpR-His6 further strengthens the idea that AmpR functions as a multimer.

AmpR mutant proteins failed to activate PampC when Ser38, His39, or Lys42 was replaced with alanine. These three residues are thus essential for AmpR activity and are presumably involved in the binding to PampC. A multiple alignment reveals that Ser38 and Lys42 are well conserved in members of the AmpR family, as expected of amino acids that play a critical role in the functionality of a protein (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material).

The loss of PampC activity in AmpRSer38Ala, AmpRHis39Ala, and AmpRLys42Ala could be attributed to the destabilization of the proteins. Their expression was thus analyzed using Western blotting with anti-AmpR antibody (Fig. 8). Interestingly, not only are these three mutant AmpR proteins made, but it appears that they, and in particular AmpRSer38Ala and AmpRLys42Ala, are made in large quantities. These amino acid substitutions, therefore, appear to stabilize rather than destabilize the proteins. Thus, we argued that the loss of PampC activity may be due to their inability to bind DNA. Gel shifts revealed that AmpRSer38Ala failed to bind to PampC while AmpRLys42Ala bound very poorly, correlating well with the loss of PampC transcriptional activity (Fig. 7). Surprisingly, the His39Ala substitution did not prevent AmpR from binding to PampC in the presence or absence of β-lactams, although it clearly prevented it from activating transcription from PampC (Fig. 6 and 7). AmpRHis39Ala is thus a positive-control mutant that can bind DNA but cannot activate transcription from the promoter to which it binds.

Positive control (pc) mutants are proteins that are defective in transcriptional activation but retain the ability to bind DNA. The pc phenotype is caused by the disruption of favorable protein-protein interactions between the activator protein and the RNA polymerase (57–59). Several pc mutants of other proteins have been characterized with mutations in or near the DNA-binding domain (57–62). Mutations away from this region have also been reported (63). In particular, mutations in the DNA-binding region have been mapped to the second helix of the HTH motif and to the junction between the second and third helices of the same domain in the activator proteins λ cI, 434 cI, and P22 c2 (57–60). AmpRHis39Ala is different from previously reported pc mutants in that its mutation is found in the helix of the DNA-binding domain that is thought to directly interact with the major groove of the DNA (helix 3) and not in the helix which usually lies across the major groove (helix 2) and makes contacts with the DNA backbone. Although it is not clear whether this third helix can contact the RNA polymerase, it may interact with other sites in the nearby helix to indirectly affect transcription. Our work here does not reveal how the disruption of His39 affects activation of transcription but merely that it is required for it.

In the present work, we show that the highly conserved residues Ser38 and Lys42 (not conserved in Klebsiella pneumoniae) in the HTH motif are critical for binding and function of AmpR. The less conserved His39 is also necessary for promoter activation but not for binding to the DNA.

Gly102 and Asp135 are critical for AmpR function.

Previous work identified C. freundii ampR mutants that constitutively express β-lactamase (64, 65). Specifically, a change in Gly102 to Glu (Gly102Glu) resulted in high constitutive β-lactamase expression in an inducer-independent manner, while a Gly102Asp substitution yielded a similar but less pronounced phenotype (64, 65). In addition, Asp135 was also found to play a role in the function of C. freundii and E. cloacae AmpR (64, 66). The expression of C. freundii AmpRAsp135Tyr led to constitutive β-lactamase hyperexpression in an ampG mutant background. In E. cloacae AmpR, Asp135 mutations to Val or Asn resulted in higher β-lactamase activity in the presence and absence of inducers and contributed to increased β-lactam resistance in two different E. coli backgrounds (64, 66). Gly102 and Asp135 thus appear to play important roles in the activation/repression state of AmpR in, at least, the Enterobacteriaceae.

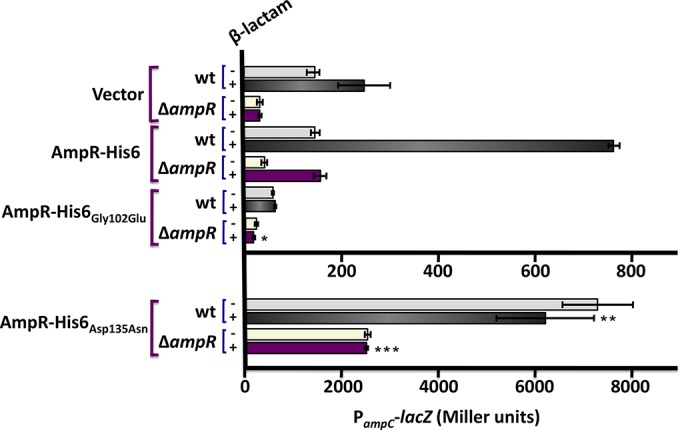

To investigate the role of these amino acids, P. aeruginosa AmpR Gly102 and Asp135 were replaced with Glu and Asn, respectively. The two mutant AmpR proteins were overexpressed in PAO1 and PA0ΔampR strains carrying PampC-lacZ (Fig. 9). Unlike in C. freundii, in P. aeruginosa the Gly102Glu substitution resulted in the loss of PampC activity in the presence and absence of β-lactams. The loss of activity is due to destabilization of the protein (Fig. 8), suggesting a structural role for Gly102 in P. aeruginosa AmpR. On the other hand, the Asp135Asn substitution led to an inducer-independent increase in PampC transcriptional activity in both PAO1 and PA0ΔampR with no concomitant increase in the amount of protein being made (Fig. 8 and 9). Thus, we postulate that the Asp135Asn substitution in the effector binding domain appears to stabilize the active conformation, effectively turning AmpR into a constitutive activator of ampC transcription. The Asp135Asn substitution has also been reported in AmpR from a P. aeruginosa clinical variant that exhibited hyperconstitutive β-lactamase expression and high resistance to β-lactams (67). The importance of Asp135 corroborates the previous work in E. cloacae and C. freundii (64, 66). Gly102, on the other hand, clearly plays different roles in the P. aeruginosa and C. freundii AmpR proteins.

FIG 9.

Activity of the P. aeruginosa ampC promoter in the presence of AmpR-His6(Gly102Glu) and AmpR-His6(Asp135Asn) mutants. Site-directed mutagenesis was used to replace Gly102 and Asp135 of P. aeruginosa AmpR with Glu and Asn, respectively. Mutant AmpRs were expressed in wild-type PAO1 and PA0ΔampR strains carrying PampC-lacZ. β-Galactosidase activity was quantified in the presence and absence of β-lactams and is represented in Miller units. *, P value < 0.01 versus induced PA0ΔampR pAmpR-His6; **, P value < 0.01 versus induced PA0attB::mini-CTX-lacZ; ***, P value < 0.001 versus induced PA0ΔampR pAmpR-His6 as determined by unpaired t test using analysis of variance.

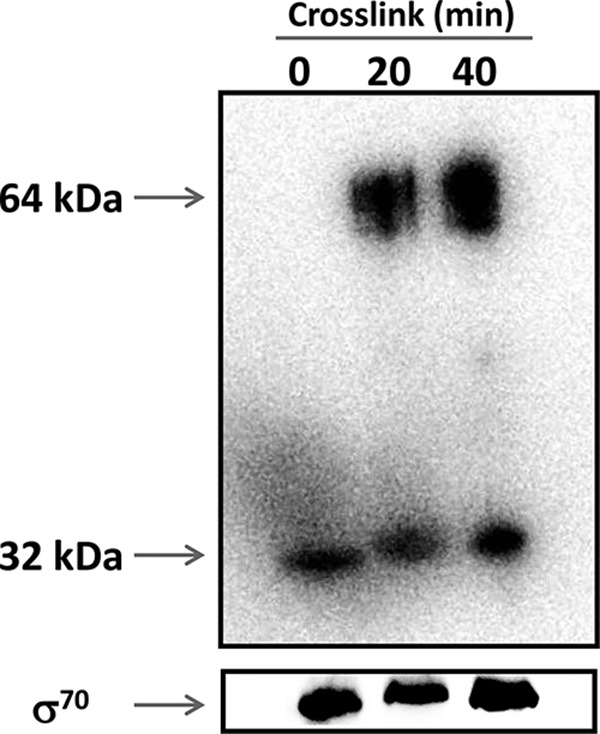

Cross-linking studies suggest that P. aeruginosa AmpR dimerizes.

The PampC activity in the presence of both ampRchr and ampRpls is always considerably higher than that in PAO1 and PA0ΔampR (ampRpls) (Fig. 6). These findings suggest a possible interaction between the wild-type and His-tagged AmpR. This is not surprising as LTTRs exist and/or function as dimers or tetramers (15, 16, 68–72). To determine if in fact P. aeruginosa AmpR can dimerize, proteins from PA0ΔampR (pAmpR-His6) were cross-linked and AmpR was visualized with anti-His antibody. The detection of a 64-kDa and a 32-kDa species in cross-linked and non-cross-linked samples, respectively, suggests that AmpR dimerizes in vivo (Fig. 10). Only the monomeric form of σ70 was detected after stripping and reprobing the blot. Our findings corroborate previous work in C. freundii where both AmpR and its effector binding domain were shown to dimerize in solution and in the crystallized form, respectively (73, 74).

FIG 10.

P. aeruginosa AmpR appears to dimerize in vivo. A fresh culture of the PA0ΔampR strain harboring pAmpR-His6 was treated with 0.1% formaldehyde for 20 and 40 min at room temperature to achieve protein cross-linking. Crude extracts containing 10 μg of total protein were separated on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and AmpR was visualized using anti-His antibody. The blot was later stripped and reprobed using anti-σ70 antibody. Monomeric AmpR is detected in non-cross-linked samples at the zero time point, while AmpR dimeric entities (64 kDa) are detected 20 and 40 min after protein cross-linking.

Localization studies of P. aeruginosa AmpR.

Although it is generally accepted that AmpR is a cytoplasmic protein, our bioinformatics analyses suggested that AmpR may be membrane associated. More specifically, a Kyte and Doolittle hydrophobicity plot (75) and the topology prediction software TopPred2 (76), DAS (77), MEMSAT (78), TMpred (79), and SCAMPI (80) suggested the presence of a transmembrane domain somewhere between amino acids 92 and 114 of P. aeruginosa AmpR. The crystal structure of C. freundii AmpR, however, reveals that this segment is near the protein-protein interface of the dimer and thus unlikely to traverse the membrane (73).

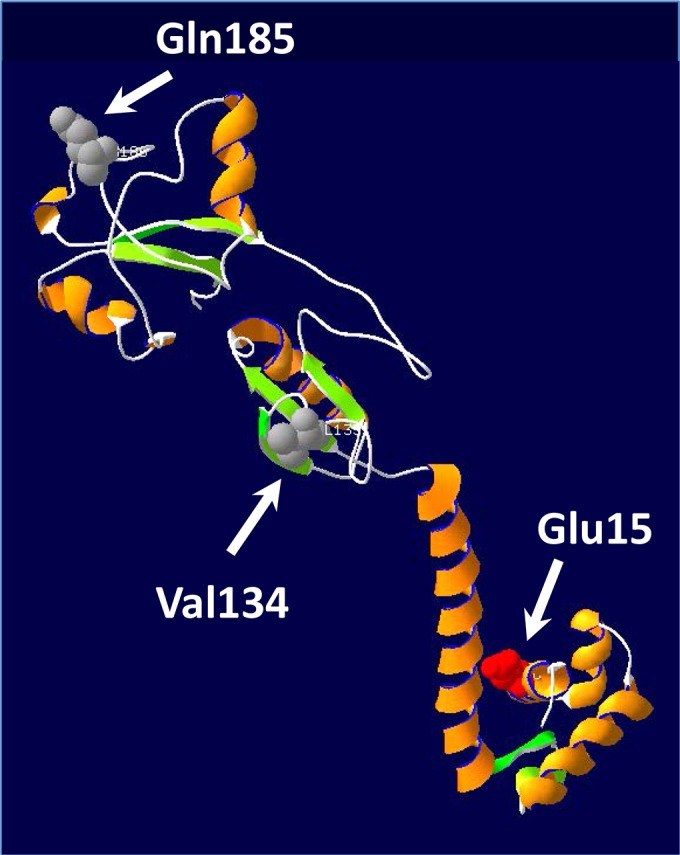

In order to localize AmpR, phoA and lacZ were fused in frame at amino acid positions Glu15, Val134, and Gln185 (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). Fusions at Glu15 were LacZ positive and PhoA negative, whereas fusions at Val134 and Gln185 were PhoA positive and LacZ negative, suggesting that AmpR may traverse the inner membrane with the N and C termini in the cytoplasm and periplasm, respectively (Fig. 11). Since these data are only qualitative, localization of P. aeruginosa AmpR was further investigated with a protease protection assay using a C-terminal His-tagged AmpR that was shown to be functional (see Table S2). Full-length AmpR (32 kDa) was detected in whole-cell extracts, as well as in spheroplast preparations treated with proteinase K (0-min incubation) that were immediately processed for immunoblotting (see Fig. S2B). Incubations with proteinase K of 5 min or longer resulted in the visible reduction of full-length AmpR and the appearance of the degradation product (10-kDa fragment). However, slight degradation of σ70 was observed. The evidence provided here is suggestive of AmpR being an inner membrane-associated protein. If confirmed, this would be an important finding and could have major implications regarding the regulation of two ampD amidase homologs that have now been localized to the periplasm (81, 82). The identity of the muramyl peptides that are important for regulating AmpR will further confirm its localization and is the subject of ongoing work in the lab.

FIG 11.

AmpR model. A three-dimensional structure of AmpR was generated using RasMol (http://www.umass.edu/microbio/rasmol/). The topology of AmpR was investigated by introducing phoA and lacZ fusions at amino acid positions Glu15, Val134, and Gln185. Fusions at Glu15 were LacZ positive but PhoA negative, whereas fusions at Val134 and Gln185 were PhoA positive and LacZ negative.

Although the majority of purified LTTRs appear to be soluble cytoplasmic proteins, the nodulation factor, NodD, from Rhizobium species appears to be a peripheral membrane protein associated with the inner leaflet of the cytoplasmic membrane (83). A few membrane-bound non-LTTRs have also been reported, such as the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium acid-sensing CadC, the streptococcal CpsA involved in regulation of capsule production, and the Vibrio cholerae toxin activator ToxR (84–86). Since these proteins act as both signal sensor and response regulator, they form a simple but sophisticated type of transmembrane signaling system.

Concluding remarks.

The role of AmpR as regulator of ampC expression has been clearly established in both the Enterobacteriaceae and P. aeruginosa. Our recent work has further redefined AmpR as a major global regulator, playing an important role in acute infections through its regulation of virulence, biofilm formation, quorum sensing, and non-β-lactam resistance (31, 39–41, 87). Regulation of ampC, however, remains one of its most critical roles, as AmpC derepression is a prevalent mechanism of β-lactam resistance in P. aeruginosa.

In the present work, we characterize some of the genetic and structural elements necessary for induction of ampC and important for the functioning of AmpR as a regulator of AmpC β-lactamase expression. The presence of strong σ54 consensus sequences in the ampR promoter led us to investigate its possible involvement in the regulation of ampR. However, contrary to what was expected, RpoN was not required for ampR expression under the conditions tested. Instead, RpoN was found to downregulate expression of both ampR and ampC, although the exact mechanism is yet unknown.

Like other LTTRs, AmpR has two important regions critical for its functioning as an activator/repressor of ampC expression: the HTH motif for binding to DNA and the effector binding domain for ligand interaction. Analysis of polar and charged amino acids on the AmpR HTH revealed two residues, Ser38 and Lys42, important for binding of AmpR to the promoter region and consequently for ampC promoter activation. A third residue, His39, was shown to be important for function but not for binding to PampC. In the effector binding domain, we examined the role of two amino acids, Gly102 and Asp135, previously shown to be important for maintaining AmpR in an inactive conformation in the enterobacteria. In P. aeruginosa, Gly102 appears to be responsible for maintaining a stable structural conformation, while Asp135 is responsible for keeping AmpR in an inactive state that represses ampC expression. Additionally, our work suggests that AmpR dimerizes and that it is likely to be membrane associated. This is the first comprehensive look at the P. aeruginosa AmpR protein and the promoter elements that it regulates.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health-Minority Biomedical Research Support SCORE (SC1AI081376) (K.M.), Research Initiative for Scientific Enhancement graduate student fellowship (NIH/NIGMS R25 GM61347) (D.Z.), NIH/NIAID R37 AI021451 (S.L.), National Science Foundation IIP-1237818 (PFI-AIR: CREST-I/UCRC-Industry Ecosystem to Pipeline Research) (K.M.), and Florida International University Dissertation Year Fellowship (D.B.).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

We thank D. Haas from UNIL, Switzerland, for kindly providing PA0ΔrpoN and PA0ΔrpoN(pRpoN); G. Plano from the University of Miami, Miami, FL, for sharing reagents for Western blotting; and Nikolay Atanasov Nachev from Florida International University, Miami, FL, for bioinformatics analysis of P. aeruginosa AmpR.

We declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 2 September 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.01997-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koch C, Hoiby N. 1993. Pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis. Lancet 341:1065–1069. 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92422-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen HY, Yuan M, Livermore DM. 1995. Mechanisms of resistance to β-lactam antibiotics amongst Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates collected in the UK in 1993. J. Med. Microbiol. 43:300–309. 10.1099/00222615-43-4-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breidenstein EB, de la Fuente-Núñez C, Hancock RE. 2011. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: all roads lead to resistance. Trends Microbiol. 19:419–426. 10.1016/j.tim.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stover CK, Pham XQ, Erwin AL, Mizoguchi SD, Warrener P, Hickey MJ, Brinkman FS, Hufnagle WO, Kowalik DJ, Lagrou M, Garber RL, Goltry L, Tolentino E, Westbrock-Wadman S, Yuan Y, Brody LL, Coulter SN, Folger KR, Kas A, Larbig K, Lim R, Smith K, Spencer D, Wong GK, Wu Z, Paulsen IT, Reizer J, Saier MH, Hancock RE, Lory S, Olson MV. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406:959–964. 10.1038/35023079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giwercman B, Lambert PA, Rosdahl VT, Shand GH, Hoiby N. 1990. Rapid emergence of resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis patients due to in-vivo selection of stable partially derepressed β-lactamase producing strains. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 26:247–259. 10.1093/jac/26.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giwercman B, Meyer C, Lambert PA, Reinert C, Hoiby N. 1992. High-level β-lactamase activity in sputum samples from cystic fibrosis patients during antipseudomonal treatment. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:71–76. 10.1128/AAC.36.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Juan C, Macia MD, Gutierrez O, Vidal C, Perez JL, Oliver A. 2005. Molecular mechanisms of β-lactam resistance mediated by AmpC hyperproduction in Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4733–4738. 10.1128/AAC.49.11.4733-4738.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanson ND, Sanders CC. 1999. Regulation of inducible AmpC β-lactamase expression among Enterobacteriaceae. Curr. Pharm. Des. 5:881–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hennessey TD. 1967. Inducible β-lactamase in Enterobacter. J. Gen. Microbiol. 49:277–285. 10.1099/00221287-49-2-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindberg F, Normark S. 1986. Contribution of chromosomal β-lactamases to β-lactam resistance in enterobacteria. Rev. Infect. Dis. 8(Suppl 3):S292–S304. 10.1093/clinids/8.Supplement_3.S292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Normark S, Lindquist S, Lindberg F. 1986. Chromosomal β-lactam resistance in enterobacteria. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. Suppl. 49:38–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Honore N, Nicolas MH, Cole ST. 1986. Inducible cephalosporinase production in clinical isolates of Enterobacter cloacae is controlled by a regulatory gene that has been deleted from Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 5:3709–3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindberg F, Normark S. 1987. Common mechanism of ampC β-lactamase induction in enterobacteria: regulation of the cloned Enterobacter cloacae P99 β-lactamase gene. J. Bacteriol. 169:758–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindberg F, Westman L, Normark S. 1985. Regulatory components in Citrobacter freundii ampC β-lactamase induction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 82:4620–4624. 10.1073/pnas.82.14.4620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maddocks SE, Oyston PC. 2008. Structure and function of the LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) family proteins. Microbiology 154:3609–3623. 10.1099/mic.0.2008/022772-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schell MA. 1993. Molecular biology of the LysR family of transcriptional regulators. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 47:597–626. 10.1146/annurev.mi.47.100193.003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs C, Frere JM, Normark S. 1997. Cytosolic intermediates for cell wall biosynthesis and degradation control inducible β-lactam resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Cell 88:823–832. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81928-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobs C, Huang LJ, Bartowsky E, Normark S, Park JT. 1994. Bacterial cell wall recycling provides cytosolic muropeptides as effectors for β-lactamase induction. EMBO J. 13:4684–4694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Normark S. 1995. β-Lactamase induction in Gram-negative bacteria is intimately linked to peptidoglycan recycling. Microb. Drug Resist. 1:111–114. 10.1089/mdr.1995.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tuomanen E, Lindquist S, Sande S, Galleni M, Light K, Gage D, Normark S. 1991. Coordinate regulation of β-lactamase induction and peptidoglycan composition by the amp operon. Science 251:201–204. 10.1126/science.1987637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng Q, Park JT. 2002. Substrate specificity of the AmpG permease required for recycling of cell wall anhydro-muropeptides. J. Bacteriol. 184:6434–6436. 10.1128/JB.184.23.6434-6436.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng Q, Li H, Merdek K, Park JT. 2000. Molecular characterization of the β-N-acetylglucosaminidase of Escherichia coli and its role in cell wall recycling. J. Bacteriol. 182:4836–4840. 10.1128/JB.182.17.4836-4840.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Votsch W, Templin MF. 2000. Characterization of a β-N-acetylglucosaminidase of Escherichia coli and elucidation of its role in muropeptide recycling and β-lactamase induction. J. Biol. Chem. 275:39032–39038. 10.1074/jbc.M004797200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holtje JV, Kopp U, Ursinus A, Wiedemann B. 1994. The negative regulator of β-lactamase induction AmpD is a N-acetyl-anhydromuramyl-l-alanine amidase. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 122:159–164. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobs C, Joris B, Jamin M, Klarsov K, Van Beeumen J, Mengin-Lecreulx D, van Heijenoort J, Park JT, Normark S, Frere JM. 1995. AmpD, essential for both β-lactamase regulation and cell wall recycling, is a novel cytosolic N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase. Mol. Microbiol. 15:553–559. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dietz H, Wiedemann B. 1996. The role of N-actylglucosaminyl-1,6 anhydro N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanyl-d-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelic acid-d-alanine for the induction of β-lactamase in Enterobacter cloacae. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. 284:207–217. 10.1016/S0934-8840(96)80096-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mengin-Lecreulx D, Flouret B, van Heijenoort J. 1982. Cytoplasmic steps of peptidoglycan synthesis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 151:1109–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dietz H, Pfeifle D, Wiedemann B. 1996. Location of N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanyl-d-glutamylmesodiaminopimelic acid, presumed signal molecule for β-lactamase induction, in the bacterial cell. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2173–2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dietz H, Pfeifle D, Wiedemann B. 1997. The signal molecule for β-lactamase induction in Enterobacter cloacae is the anhydromuramyl-pentapeptide. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2113–2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Juan C, Moya B, Perez JL, Oliver A. 2006. Stepwise upregulation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa chromosomal cephalosporinase conferring high-level β-lactam resistance involves three AmpD homologues. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1780–1787. 10.1128/AAC.50.5.1780-1787.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kong K-F, Jayawardena SR, Indulkar SD, del Puerto A, Koh C-L, Hoiby N, Mathee K. 2005. Pseudomonas aeruginosa AmpR is a global transcriptional factor that regulates expression of AmpC and PoxB β-lactamases, proteases, quorum sensing, and other virulence factors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4567–4575. 10.1128/AAC.49.11.4567-4575.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langaee TY, Dargis M, Huletsky A. 1998. An ampD gene in Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes a negative regulator of AmpC β-lactamase expression. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:3296–3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Langaee TY, Gagnon L, Huletsky A. 2000. Inactivation of the ampD gene in Pseudomonas aeruginosa leads to moderate-basal-level and hyperinducible AmpC β-lactamase expression. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:583–589. 10.1128/AAC.44.3.583-589.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lodge J, Busby S, Piddock L. 1993. Investigation of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa ampR gene and its role at the chromosomal ampC β-lactamase promoter. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 111:315–320. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lodge JM, Minchin SD, Piddock LJ, Busby JW. 1990. Cloning, sequencing and analysis of the structural gene and regulatory region of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa chromosomal ampC β-lactamase. Biochem. J. 272:627–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y, Bao Q, Gagnon LA, Huletsky A, Oliver A, Jin S, Langaee T. 2010. ampG gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its role in β-lactamase expression. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:4772–4779. 10.1128/AAC.00009-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zamorano L, Reeve TM, Juan C, Moya B, Cabot G, Vocadlo DJ, Mark BL, Oliver A. 2011. AmpG inactivation restores susceptibility of pan-β-lactam-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:1990–1996. 10.1128/AAC.01688-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kong KF, Aguila A, Schneper L, Mathee K. 2010. Pseudomonas aeruginosa β-lactamase induction requires two permeases, AmpG and AmpP. BMC Microbiol. 10:328. 10.1186/1471-2180-10-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balasubramanian D, Schneper L, Kumari H, Mathee K. 2013. A dynamic and intricate regulatory network determines Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence. Nucleic Acids Res. 41:1–20. 10.1093/nar/gks1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balasubramanian D, Schneper L, Merighi M, Smith R, Narasimhan G, Lory S, Mathee K. 2012. The regulatory repertoire of Pseudomonas aeruginosa AmpC β-lactamase regulator AmpR includes virulence genes. PLoS One 7:e34067. 10.1371/journal.pone.0034067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumari H, Murugapiran SK, Balasubramanian D, Schneper L, Merighi M, Sarracino D, Lory S, Mathee K. 2014. LTQ-XL mass spectrometry proteome analysis expands the Pseudomonas aeruginosa AmpR regulon to include cyclic di-GMP phosphodiesterases and phosphoproteins, and identifies novel open reading frames. J. Proteomics 96:328–342. 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumari H, Balasubramanian D, Zincke D, Mathee K. 2014. Role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa AmpR on β-lactam and non-β-lactam transient cross-resistance upon pre-exposure to subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics. J. Med. Microbiol. 63:544–555. 10.1099/jmm.0.070185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Furste JP, Pansegrau W, Frank R, Blocker H, Scholz P, Bagdasarian M, Lanka E. 1986. Molecular cloning of the plasmid RP4 primase region in a multi-host-range tacP expression vector. Gene 48:119–131. 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90358-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scotto-Lavino E, Du G, Frohman MA. 2006. 5′ end cDNA amplification using classic RACE. Nat. Protoc. 1:2555–2562. 10.1038/nprot.2006.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brencic A, Lory S. 2009. Determination of the regulon and identification of novel mRNA targets of Pseudomonas aeruginosa RsmA. Mol. Microbiol. 72:612–632. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06670.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Castang S, McManus HR, Turner KH, Dove SL. 2008. H-NS family members function coordinately in an opportunistic pathogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:18947–18952. 10.1073/pnas.0808215105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Campo N, Rudner DZ. 2006. A branched pathway governing the activation of a developmental transcription factor by regulated intramembrane proteolysis. Mol. Cell 23:25–35. 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith PK, Krohn RI, Hermanson GT, Mallia AK, Gartner FH, Provenzano MD, Fujimoto EK, Goeke NM, Olson BJ, Klenk DC. 1985. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal. Biochem. 150:76–85. 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mathee K, McPherson CJ, Ohman DE. 1997. Posttranslational control of the algT (algU)-encoded σ22 for expression of the alginate regulon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and localization of its antagonist proteins MucA and MucB (AlgN). J. Bacteriol. 179:3711–3720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blank TE, Donnenberg MS. 2001. Novel topology of BfpE, a cytoplasmic membrane protein required for type IV fimbrial biogenesis in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183:4435–4450. 10.1128/JB.183.15.4435-4450.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lindquist S, Lindberg F, Normark S. 1989. Binding of the Citrobacter freundii AmpR regulator to a single DNA site provides both autoregulation and activation of the inducible ampC β-lactamase gene. J. Bacteriol. 171:3746–3753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boucher JC, Schurr MJ, Deretic V. 2000. Dual regulation of mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and sigma factor antagonism. Mol. Microbiol. 36:341–351. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reitzer LJ, Bueno R, Cheng WD, Abrams SA, Rothstein DM, Hunt TP, Tyler B, Magasanik B. 1987. Mutations that create new promoters suppress the σ54 dependence of glnA transcription in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 169:4279–4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoang TT, Kutchma AJ, Becher A, Schweizer HP. 2000. Integration-proficient plasmids for Pseudomonas aeruginosa: site-specific integration and use for engineering of reporter and expression strains. Plasmid 43:59–72. 10.1006/plas.1999.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huffman JL, Brennan RG. 2002. Prokaryotic transcription regulators: more than just the helix-turn-helix motif. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 12:98–106. 10.1016/S0959-440X(02)00295-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aravind L, Anantharaman V, Balaji S, Babu MM, Iyer LM. 2005. The many faces of the helix-turn-helix domain: transcription regulation and beyond. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 29:231–262. 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bushman FD, Ptashne M. 1988. Turning λ Cro into a transcriptional activator. Cell 54:191–197. 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90551-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hochschild A, Irwin N, Ptashne M. 1983. Repressor structure and the mechanism of positive control. Cell 32:319–325. 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90451-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whipple FW, Ptashne M, Hochschild A. 1997. The activation defect of a λcI positive control mutant. J. Mol. Biol. 265:261–265. 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bushman FD, Shang C, Ptashne M. 1989. A single glutamic acid residue plays a key role in the transcriptional activation function of λ repressor. Cell 58:1163–1171. 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90514-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gosink KK, Gaal T, Bokal AJ, Gourse RL. 1996. A positive control mutant of the transcription activator protein FIS. J. Bacteriol. 178:5182–5187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guarente L, Nye JS, Hochschild A, Ptashne M. 1982. Mutant λ phage repressor with a specific defect in its positive control function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 79:2236–2239. 10.1073/pnas.79.7.2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhou Y, Zhang X, Ebright RH. 1993. Identification of the activating region of catabolite gene activator protein (CAP): isolation and characterization of mutants of CAP specifically defective in transcription activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:6081–6085. 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bartowsky E, Normark S. 1991. Purification and mutant analysis of Citrobacter freundii AmpR, the regulator for chromosomal AmpC β-lactamase. Mol. Microbiol. 5:1715–1725. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bartowsky E, Normark S. 1993. Interactions of wild-type and mutant AmpR of Citrobacter freundii with target DNA. Mol. Microbiol. 10:555–565. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kuga A, Okamoto R, Inoue M. 2000. ampR gene mutations that greatly increase class C β-lactamase activity in Enterobacter cloacae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:561–567. 10.1128/AAC.44.3.561-567.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bagge N, Ciofu O, Hentzer M, Campbell JI, Givskov M, Hoiby N. 2002. Constitutive high expression of chromosomal β-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa caused by a new insertion sequence (IS1669) located in ampD. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3406–3411. 10.1128/AAC.46.11.3406-3411.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McFall SM, Chugani SA, Chakrabarty AM. 1998. Transcriptional activation of the catechol and chlorocatechol operons: variations on a theme. Gene 223:257–267. 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00366-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miller BE, Kredich NM. 1987. Purification of the CysB protein from Salmonella typhimurium. J. Biol. Chem. 262:6006–6009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Muraoka S, Okumura R, Ogawa N, Nonaka T, Miyashita K, Senda T. 2003. Crystal structure of a full-length LysR-type transcriptional regulator, CbnR: unusual combination of two subunit forms and molecular bases for causing and changing DNA bend. J. Mol. Biol. 328:555–566. 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00312-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Parsek MR, Shinabarger DL, Rothmel RK, Chakrabarty AM. 1992. Roles of CatR and cis,cis-muconate in activation of the catBC operon, which is involved in benzoate degradation in Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 174:7798–7806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schell MA, Brown PH, Raju S. 1990. Use of saturation mutagenesis to localize probable functional domains in the NahR protein, a LysR-type transcription activator. J. Biol. Chem. 265:3844–3850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Balcewich MD, Reeve TM, Orlikow EA, Donald LJ, Vocadlo DJ, Mark BL. 2010. Crystal structure of the AmpR effector binding domain provides insight into the molecular regulation of inducible Ampc β-lactamase. J. Mol. Biol. 400:998–1010. 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bishop RE, Weiner JH. 1993. Overproduction, solubilization, purification and DNA-binding properties of AmpR from Citrobacter freundii. Eur. J. Biochem. 213:405–412. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kyte J, Doolittle RF. 1982. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 157:105–132. 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.von Heijne G. 1992. Membrane protein structure prediction. Hydrophobicity analysis and the positive-inside rule. J. Mol. Biol. 225:487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cserzo M, Wallin E, Simon I, von Heijne G, Elofsson A. 1997. Prediction of transmembrane alpha-helices in prokaryotic membrane proteins: the dense alignment surface method. Protein Eng. 10:673–676. 10.1093/protein/10.6.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jones DT, Taylor WR, Thornton JM. 1994. A model recognition approach to the prediction of all-helical membrane protein structure and topology. Biochemistry 33:3038–3049. 10.1021/bi00176a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hofmann K, Stoffel W. 1993. A database of membrane spanning protein segments. Biol. Chem. Hoppe-Seyler 374:166. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bernsel A, Viklund H, Falk J, Lindahl E, von Heijne G, Elofsson A. 2008. Prediction of membrane-protein topology from first principles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:7177–7181. 10.1073/pnas.0711151105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lee M, Artola-Recolons C, Carrasco-Lopez C, Martinez-Caballero S, Hesek D, Spink E, Lastochkin E, Zhang W, Hellman LM, Boggess B, Hermoso JA, Mobashery S. 2013. Cell-wall remodeling by the zinc-protease AmpDh3 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135:12604–12607. 10.1021/ja407445x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang W, Lee M, Hesek D, Lastochkin E, Boggess B, Mobashery S. 2013. Reactions of the three AmpD enzymes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135:4950–4953. 10.1021/ja400970n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schlaman HR, Spaink HP, Okker RJ, Lugtenberg BJ. 1989. Subcellular localization of the nodD gene product in Rhizobium leguminosarum. J. Bacteriol. 171:4686–4693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dell CL, Neely MN, Olson ER. 1994. Altered pH and lysine signalling mutants of cadC, a gene encoding a membrane-bound transcriptional activator of the Escherichia coli cadBA operon. Mol. Microbiol. 14:7–16. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hanson BR, Lowe BA, Neely MN. 2011. Membrane topology and DNA-binding ability of the streptococcal CpsA protein. J. Bacteriol. 193:411–420. 10.1128/JB.01098-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Miller VL, Taylor RK, Mekalanos JJ. 1987. Cholera toxin transcriptional activator ToxR is a transmembrane DNA binding protein. Cell 48:271–279. 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90430-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Balasubramanian D, Kumari H, Jaric M, Fernandez M, Turner KH, Dove SL, Narasimhan G, Lory S, Mathee K. 2014. Deep sequencing analyses expands the Pseudomonas aeruginosa AmpR regulon to include small RNA-mediated regulation of iron acquisition, heat shock and oxidative stress response. Nucleic Acids Res. 42:979–998. 10.1093/nar/gkt942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.