Abstract

The type III export apparatus of the Salmonella flagellum consists of six transmembrane proteins (FlhA, FlhB, FliO, FliP, FliQ, and FliR) and three soluble proteins (FliH, FliI, and FliJ). Deletion of the fliO gene creates a mutant strain that is poorly motile; however, suppressor mutations in the fliP gene can partially rescue motility. To further understand the mechanism of suppression of a fliO deletion mutation, we isolated new suppressor mutant strains with partially rescued motility. Whole-genome sequence analysis of these strains found a missense mutation that localized to the clpP gene [clpP(V20F)], which encodes the ClpP subunit of the ClpXP protease, and a synonymous mutation that localized to the fliA gene [fliA(+36T→C)], which encodes the flagellar sigma factor, σ28. Combining these suppressor mutations with mutations in the fliP gene additively rescued motility and biosynthesis of the flagella in fliO deletion mutant strains. Motility was also rescued by an flgM deletion mutation or by plasmids carrying either the flhDC or fliA gene. The fliA(+36T→C) mutation increased mRNA translation of a fliA′-lacZ gene fusion, and immunoblot analysis revealed that the mutation increased levels of σ28. Quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase PCR showed that either the clpP(V20F) or fliA(+36T→C) mutation rescued expression of class 3 flagellar and chemotaxis genes; still, the suppressor mutations in the fliP gene had a greater effect on bypassing the loss of fliO function. This suggests that the function of FliO is closely associated with regulation of FliP during assembly of the flagellum.

INTRODUCTION

The bacterial flagellum enables cells to swim through liquid environments and to swarm and spread on surfaces (1, 2). The best-characterized flagellum belongs to a member of the Gammaproteobacteria, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. The flagellum consists of three parts: the basal body, the hook, and the filament (1). Synthesis of the flagellum is coupled with regulation of expression of flagellar genes. The flagellar regulon of Salmonella is organized into a three-tier hierarchy of class 1, class 2, and class 3 flagellar genes (3). Class 1 genes belong to the flhDC operon, which encodes the FlhD4FlhC2 transcription factor. Class 2 genes require FlhD4FlhC2 for expression and include genes that encode the components of the hook-basal body complex. They also include the fliAZY operon: fliA encodes the flagellar gene sigma factor, σ28, fliZ encodes an activator of class 2 flagellar gene expression, and fliY is a nonflagellar gene with its own promoter (4, 5). The class 3 genes encode proteins that make the filament, motor, and chemotaxis proteins. Expression of class 3 genes requires RNA polymerase and σ28. Some flagellar genes (including the fliAZY operon) are expressed from both class 2 and class 3 promoters (3–5).

Within the center of the flagellar basal body pore is a type III export apparatus that exports the external building blocks of the flagellum. A homologous type III export apparatus is found within the type III secretion injectisomes that are produced by some pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria, including S. enterica (6). The injectisomes export effector proteins from the cytoplasm of the bacterium and inject them into eukaryotic cells during infection. The type III export apparatus uses energy from ATP hydrolysis and the proton motive force across the cytoplasmic membrane for protein export (7, 8). The flagellar export apparatus is made of six transmembrane proteins (FlhA, FlhB, FliO, FliP, FliQ, and FliR) and three soluble proteins (FliH, FliI, and FliJ) (1, 6). FlhA, FlhB, FliP, FliQ, and FliR are highly conserved and essential for export apparatus function (1, 6). FlhA (75 kDa) has a 40-kDa C-terminal cytoplasmic domain, and FlhB (42 kDa) has a 19-kDa C-terminal cytoplasmic domain that functions in export substrate docking (9). FliI (49 kDa) is an ATPase that together with FliH (26 kDa) and FliJ (17 kDa) forms an ATPase ring complex at the export gate that also plays an important role in substrate recognition (9). The functions of FliO (13 kDa), FliP (25 kDa), FliQ (10 kDa), and FliR (29 kDa) are unknown. FliP is made with an N-terminal signal peptide that is required for insertion of FliP into the cytoplasmic membrane and afterwards is cleaved to produce mature FliP (10). Mature FliP and FliR copurify with the basal body (11).

FliO is a bitopic membrane protein that has an 11-kDa cytoplasmic domain and is less conserved than the other export apparatus proteins. A homolog of FliO exists for the flagella of many species of proteobacteria (12, 13), but a homolog has not been identified for the flagella of some distantly related species, such as Aquifex aeolicus, and a homolog is absent from the injectisomes (14). In a previous study, we made an in-frame fliO gene deletion mutant strain of S. enterica, and it was poorly motile (15). However, it produced suppressor mutant strains with somewhat rescued motility. We characterized two suppressor mutant strains and found suppressor mutations by using chain-termination dideoxynucleotide sequencing of genes encoding proteins that make the type III export apparatus. For each strain, a suppressor mutation was localized to the fliP gene. One suppressor mutant strain bore a fliP(F190L) missense mutation. We determined that the other suppressor mutant strain bore at least two suppressor mutations, a fliP(R143H) missense mutation, and another, unknown mutation. The unknown mutation was confirmed because a ΔfliO fliP(R143H) double-mutant strain made with bacteriophage lambda Red homologous recombination was less motile than the suppressor mutant strain. We have now identified the unknown mutation by using comparative genome sequence analysis. In addition, we investigated the source of rescued motility of other suppressor mutant strains and found that the newly identified mutations affect regulation of expression of flagellar genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth of bacterial strains.

The S. enterica strains and the plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1 (16–23). Escherichia coli NovaBlue (Novagen, EMD Millipore) was used for DNA manipulation. Bacterial strains were routinely grown aerobically in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (24) with shaking (250 rpm) at 37°C. Ampicillin was used at 100 μg ml−1 to maintain plasmids in S. enterica and at 50 μg ml−1 to maintain plasmids in E. coli. Kanamycin was used at 50 μg ml−1. Tetracycline was used at 15 μg ml−1. All chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich or Wako (Japan), unless otherwise indicated.

TABLE 1.

Salmonella strains and plasmids used for this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype and/or description | Source and/or referencea |

|---|---|---|

| Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strainsb | ||

| SJW1103 | Wild type for motility and chemotaxis; LT2 (fljB-off) Δ(hin-fljAB) | 16 |

| JR501 | Strain for converting plasmids to Salmonella compatibility; restriction negative, modification positive | 17 |

| TT13206 | LT7 phoN51::Tn10-11(Tetr) | 18; SGSC3718 |

| SJW1368 | Δ(cheW-flhD); nonmotile and without flagella | 19 |

| CB184 | Δ(fliO-fliP)22251::FRT | 15 |

| CB187 | ΔfliO22252::FRT | 15 |

| CB190 | ΔfliO22252 fliA22300(+36T→C); suppressor mutant strain | |

| CB191 | ΔfliO22252 fliP22254(R143H) clpP96(V20F); suppressor mutant strain | 15 |

| CB228 | ΔfliO22252; suppressor mutant strain | |

| CB229 | ΔfliO22252; suppressor mutant strain | |

| CB230 | ΔfliO22252; suppressor mutant strain | |

| CB281 | ΔfliO22252 fliP22254(R143H) | 15 |

| CB282 | ΔfliO22252 fliP22255(F190L) | 15 |

| CB382 | ΔfliO22252 ΔclpP100::tetRA | |

| CB383 | ΔfliO22252 fliP22254(R143H) ΔclpP100::tetRA | |

| CB389 | ΔfliO22252 ΔclpA97::FKF | |

| CB408 | ΔfliO22252 Δ(clpP-clpX)98::FKF | |

| CB432 | ΔfliO22252 ΔclpA97::FRT | |

| CB433 | ΔfliO22252 Δ(clpP-clpX)98::FRT | |

| CB443 | ΔfliO22252 clpP96(V20F) | |

| CB447 | ΔfliO22252 fliP22254(R143H) clpP96(V20F) | |

| CB476 | ΔfliA22301::tetRA | |

| CB478 | ΔfliO22252 ΔfliA22301::tetRA | |

| CB484 | ΔfliO22252 ΔclpX99::FKF | |

| CB502 | ΔfliO22252 fliA22300(+36T→C) | |

| CB506 | ΔfliO22252 ΔclpX99::FRT | |

| CB558 | fliA22300(+36T→C) | |

| CB588 | fliO22252 fliP22254(R143H) ΔfliA22301::tetRA | |

| CB589 | fliO22252 fliP22255(F190L) ΔfliA22301::tetRA | |

| CB590 | fliO22252 fliP22254(R143H) fliA22300(+36T→C) | |

| CB591 | fliO22252 fliP22255(F190L) fliA22300(+36T→C) | |

| CB593 | ΔfliO22252 ΔfliP22305::tetRA | |

| CB594 | ΔfliO22252 ΔfliP22305::tetRA fliA22300(+36T→C) | |

| CB595 | ΔfliO22252 ΔfliA22305::tetRA clpP96(V20F) | |

| CB597 | ΔfliO22252 fliP22254(R143H) fliP22255(F190L) | |

| CB598 | ΔfliO22252 fliP22254(R143H) fliP22255(F190L) fliA22300(+36T→C) | |

| CB599 | ΔfliO22252 fliA22300(+36T→C) clpP96(V20F) | |

| CB818 | ΔflgM22443::FKF | |

| CB820 | ΔfliO22252 ΔflgM22443::FKF | |

| CB821 | ΔfliO22252 ΔflgM22443::FRT | |

| Plasmidsc | ||

| pKD46 | Bacteriophage λ Red expression plasmid; Ampr | 20 |

| pKD13 | Carries an FRT-flanked kanamycin resistance cassette; Ampr Kmr | 20 |

| pKD4 | Carries an FRT-flanked kanamycin resistance cassette; Ampr Kmr | 20 |

| pCP20 | Flp expression plasmid; Ampr Camr | 21 |

| pTrc99A-FF4 | Expression vector; Ampr | 10 |

| pET-22b(+) | pT7 expression vector, optional C-terminal His tag; Ampr | Novagen |

| pFZY1 | Transcriptional lacZ fusion vector; Ampr | 22; NIG |

| pMC1403 | Translational lacZ fusion vector; Ampr | 23; NIG |

| pCB20 | pTrc99A-FF4 carrying fliO | 15 |

| pCB211 | pTrc99A-FF4 carrying fliP | 15 |

| pCB259 | pTrc99A-FF4 carrying fliO and fliP(R143H) | 15 |

| pCB320 | pTrc99A-FF4 carrying fliP and fliO | |

| pCB322 | pTrc99A-FF4 carrying fliP(R143H) | |

| pCB323 | pTrc99A-FF4 carrying fliP(F190L) | |

| pCB331 | pET-22b(+) carrying fliP codons 106 to 185 and codons for a C-terminal 6×His tag | |

| pCB568 | pTrc99A-FF4 carrying fliA | |

| pCB569 | pTrc99A-FF4 carrying fliZ | |

| pCB572d | pFZY1 fliA (−116 to +400) | |

| pCB573d | pFZY1 fliA (−116 to +400), synonymous mutation (+36T→C) | |

| pCB574d | pMC1403 fliA (−118 to +399) | |

| pCB575d | pMC1403 fliA (−118 to +399), synonymous mutation (+36T→C) | |

| pCB576d | pMC1403 fliA (−118 to +399), P2 negative (−33GCC−31→−33CGT−31) | |

| pCB577d | pMC1403 fliA (−118 to +399), P2 negative (−33GCC−31→−33CGT−31), synonymous mutation (+36T→C) | |

| pCB578d | pMC1403 fliA (−58 to +399) | |

| pCB579d | pMC1403 fliA (−58 to +399), synonymous mutation (+36T→C) | |

| pCB587 | pTrc99A-FF4 carrying flhDC | |

| pCB596 | pTrc99A-FF4 carrying fliO and fliP(R143H, F190L) | |

| pCB659 | pTrc99A-FF4 carrying fliC | |

| pCB660 | pTrc99A-FF4 carrying fliS | |

| pCB661 | pTrc99A-FF4 carrying fliS and fliC |

All strains and plasmids were made in this study unless indicated otherwise. SGSC, Salmonella Genetic Stock Center, University of Calgary, Canada; NIG, National Institute of Genetics, Japan.

FRT refers to the flippase enzyme recognition target site. FKF is an FRT-flanked kanamycin resistance cassette.

Flp refers to the recombinase enzyme.

The DNA regions inserted into the plasmids were numbered relative to the translation initiation codon of the fliA gene, which was considered position 1.

Construction of strains and plasmids.

Replacement of wild-type genes on the chromosome with mutant alleles was done with the bacteriophage lambda Red recombination method of Karlinsey (25). Chromosomal gene deletions were made with the lambda Red recombination method of Datsenko and Wanner (20). Full details of strain and plasmid construction are given in the supplemental material. Oligonucleotide primers used for strain and plasmid construction are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material and were synthesized by Life Technologies. DNA manipulations were performed according to standard procedures (24). Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using a QuikChange Lightning site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies).

Isolation of suppressor mutant strains and motility assays.

Soft tryptone agar plates (0.35% [wt/vol] agar) were used in motility assays at 30°C (26). Antibiotic was added to maintain plasmids as required. To produce suppressor mutant strains from the fliO deletion mutant strain (CB187), soft tryptone agar was inoculated with a 10-μl streak of an overnight culture. Suppressor mutants arose after about 24 h. Swimming rates were determined by measuring the increase in swim-ring diameter (mm) at intervals (every 1 to 4 h). The statistical significance of the difference in swimming rate between samples was determined with two-tailed Student's t test.

Whole-genome sequencing.

A Genome Analyzer IIx (Illumina, San Diego, CA) instrument was used for parallel sequencing of the 4.9-Mbp whole genome of the wild-type strain SJW1103, the fliO deletion mutant strain CB187, and five suppressor mutant strains (CB190, CB191, CB228, CB229, and CB230) with rescued motility produced by CB187. A multiplexed 76-bp, single-end-read genomic DNA sequencing run was used. A total of 530 Mbp of data was obtained for each genome. Library samples were prepared according to Illumina's instructions for multiplexing. Processing of raw sequence data from the Genome Analyzer IIx was performed using Illumina Genome Analyzer Pipeline software. The genome sequence of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 (NC_003197.1; Typhimurium.fasta) was used as the reference platform. Sequence data were then analyzed to identify fixed mutations by using inGAP software (27) and independently by mapping with the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/), formatting with SAMtools (http://samtools.sourceforge.net/), and single nucleotide polymorphism calling with SAMtools and BCFtools.

Immunoblot analyses.

Immunoblotting was performed similarly to a previously described method (28). Colonies of S. enterica were inoculated into 10 ml LB medium with an appropriate antibiotic and grown with shaking at 37°C to the required growth phase, or colonies of bacteria transformed with plasmids were inoculated into 10 ml LB medium with antibiotic and grown until an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.8, and then protein expression was induced for 2 h with the addition of 1 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Cells (normalized to 0.5 ml culture broth for an OD600 of 1.0) were harvested by centrifugation at 16,100 × g for 5 min. Pellets were suspended in 40 μl sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) loading buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 2% SDS, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 7 M urea, and 0.1% bromophenol blue) and incubated at 95°C for 15 min. Equivalent amounts of whole-cell lysates (4 to 10 μl) were separated by SDS-PAGE, and proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Bound antibodies were detected using the WesternBreeze chromogenic immunodetection system (Life Technologies). Band densitometry was performed using a ChemiDoc XRS+ system with Image Lab software (Bio-Rad). The statistical significance of the difference in band densitometry between samples was determined with two-tailed Student's t test.

Rabbit sera containing polyclonal antibodies were used at the following dilutions: σ28, 1:1,000; FliS, 1:2,000; FliO, 1:10,000; and FliP, 1:10 (after purification). To produce antiserum containing polyclonal antibodies for FliP, a FliP(106–185)-polyhistidine tag construct was purified using nickel affinity chromatography under denaturing conditions (29). However, further purification of FliP antibodies from the antiserum was required, by adsorption of nonspecific antibodies (30). Briefly, 1.5 mg protein from whole-cell lysate of strain CB184 [Δ(fliO-fliP)] was transferred to a PVDF membrane and incubated overnight at 4°C with a 1:100 dilution of FliP antiserum in primary antibody wash solution. This was then used as the purified FliP antibody stock.

FlgE and FliC export assays.

Export assays were performed as described previously (31). Briefly, three independent cultures of each S. enterica strain were grown at 37°C in LB medium with an appropriate antibiotic to late exponential phase (OD600 of 1.2). Culture broth (1.5 ml) was harvested by centrifugation at 16,100 × g for 5 min to obtain cell pellet and culture supernatant fractions. Proteins secreted into 1.4 ml of the culture supernatant were precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid and suspended in 40 μl Tris–SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Cell pellets were then suspended in 40 μl SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Samples were heated at 95°C for 15 min. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, using 12.5% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gels, and transferred to a PVDF membrane for immunoblot analyses. The following amounts of sample were loaded onto each polyacrylamide gel: supernatant for FliC detection, 5 μl; supernatant for FlgE detection, 20 μl; pellet for FliC detection, 0.5 μl; and pellet for FlgE detection, 3 μl. Rabbit antiserum containing polyclonal antibodies for either FlgE (1:1,000 dilution for the supernatant fractions and 1:10,000 dilution for the cell pellets) or FliC (1:20,000 dilution) was used. Bound antibodies were detected using the WesternBreeze chromogenic immunodetection system (Life Technologies). Band densitometry was performed using a ChemiDoc XRS+ system with Image Lab software (Bio-Rad).

Microscopy of cells.

Motility of cells grown to exponential phase (OD600 of 0.8) in 10 ml LB medium at 37°C was examined by phase-contrast microscopy. A BX53 system microscope (Olympus Corporation, Japan) was used with a DP72 digital camera at a magnification of ×1,000. Whole cells were also examined by transmission electron microscopy (12). Cells were harvested by gentle centrifugation (300 × g) and suspended in molecular biology-grade water. Cells were then immobilized on Mextaform HF-34 200-mesh carbon-coated copper grids and stained with 1% uranyl acetate (pH 5). Grids were examined using a JEM-1230R transmission electron microscope (Jeol, Ltd., Japan) at 100 keV. The statistical significance of the difference in the distribution of flagellar numbers between samples was determined with a two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test.

β-Galactosidase assays.

β-Galactosidase activity was assayed by measuring the hydrolysis of o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactosidase (ONPG) by the method of Miller (32) for cells grown to exponential phase (OD600 of 0.65) in LB medium with the appropriate antibiotic at 37°C. The statistical significance of the difference in enzyme activity between samples was determined with two-tailed Student's t test.

RNA isolation and real-time qRT-PCR.

Cells were grown to exponential phase (OD600 of 0.65) at 37°C in LB medium. Total RNA was isolated using a RiboPure Bacteria kit (Life Technologies) and was treated with DNase I for 30 min at 37°C to eliminate genomic DNA contamination. RNA quality was determined using an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer. The RNA was used as the template in first-strand cDNA synthesis using a SuperScript Vilo cDNA synthesis kit, which includes SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (RT) and random primers (Life Technologies). Real-time quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) mixtures were set up using SYBR Select master mix (Life Technologies). The primers listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material were used at 200 nM in the qRT-PCR mixtures. Reactions and data analysis were performed using a model 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Three cultures were prepared for each strain (biological triplicates), and the level of target from each culture was determined twice (technical duplicates). Results were analyzed by the relative quantification (ΔΔCT) method (33). Relative quantities of target mRNAs for each sample were determined by normalization of fluorescence signals for the target mRNAs to those of two endogenous controls (gapA and gyrB mRNAs) (34) and by comparison of the samples to the reference sample (SJW1103; wild type).

RESULTS

Novel suppressor mutations that bypass a loss of fliO function.

An S. enterica mutant strain bearing a nonpolar deletion mutation of the fliO gene is poorly motile but produces suppressor mutant strains with rescued motility about 24 h after inoculation into soft tryptone agar. We previously described mutations in the fliP gene [fliP(R143H) and fliP(F190L)] that bypass a loss of fliO function (15), and here we describe novel mutations that also bypass a loss of fliO function. Genomic DNAs were prepared and sequenced for SJW1103 (wild type), CB187 (the fliO deletion mutant strain), and five suppressor mutant strains: CB190, CB191, CB228, CB229, and CB230. Suppressor mutations were localized by comparative sequence analysis of the genomes (Table 2). CB191 bore the fliP(R143H) mutation and an additional missense mutation in the clpP gene, at codon 20 [clpP(V20F)], encoding the ClpP peptidase subunit. The ClpP protein is made with a leader peptide that is processed, so the mutation produces a V6F substitution in the mature protein. CB190 bore a synonymous mutation within the coding region of the fliA gene [fliA(+36T→C)], encoding the flagellar gene-specific sigma factor σ28. The mutation changed codon 12, encoding aspartate, from 5′-GAT-3′ to 5′-GAC-3′. The clpP and fliA genes regulate flagellar gene expression: the ClpXP protease regulates proteolytic turnover of the flagellar regulon master regulator FlhD4FlhC2 (35), and σ28 is required for expression of class 3 and some class 2 flagellar genes (3). No additional mutations were found for CB228, CB229, or CB230. These suppressor mutant strains were unstable and, after repeated subculturing, gradually lost the rescued motility.

TABLE 2.

Randomly selected mutations that rescued motility for strains bearing a fliO deletion mutation

| Strain | Gene | Protein name | Mutationa | Amino acid substitutionb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CB190 | fliA | σ28, the sigma factor for flagellar genes | +36T→C | None; codon 12 for aspartate was changed from 5′-GAT-3′ to 5′-GAC-3′ |

| CB191 | clpP | ATP-dependent Clp protease proteolytic subunit | +58G→T | V20F (V6F) |

| fliP | FliP | +428G→A | R143H (R122H) | |

| CB227 | fliP | FliP | +568T→C | F190L (F169L) |

The position of the mutation is relative to the start codon of translation. Mutations in the fliP gene of CB191 and CB227 were identified previously (15). Mutations in the fliA and clpP genes were found by whole-genome sequencing and confirmed by chain-termination dideoxynucleotide sequencing.

ClpP and FliP are synthesized with short N-terminal leader peptides of 14 and 21 amino acid residues, respectively, which are cleaved to generate the mature proteins. Positions of the substitutions in the mature proteins are shown in parentheses.

Motility of strains bearing a fliO deletion mutation was rescued additively, either by combining the suppressor mutations or by increased expression of flagellar gene regulators.

To understand the effect of the suppressor mutations, a number of strains were made by using the Karlinsey method (25) of bacteriophage lambda Red homologous recombination. The motility (swimming rate) of the strains in soft tryptone agar was then determined (Table 3). The mean swimming rate of the fliO deletion mutant strain (0.7 ± 0.1 mm h−1) was 10-fold less than that of the wild-type strain (7.0 ± 0.1 mm h−1). Four suppressor mutations that bypass a loss of fliO function [clpP(V20F), fliA(+36T→C), fliP(R143H), and fliP(F190L)] were separately introduced into strains together with a fliO deletion mutation, producing double-mutant strains. All double-mutant strains were significantly (P < 0.05) more motile than the strain bearing the fliO deletion mutation alone. However, the double-mutant strains were all much less motile than the wild type. The fliP(F190L) suppressor mutation was most effective at bypassing a loss of fliO function. The ΔfliO fliP(F190L) double-mutant strain was >4-fold more motile than the fliO deletion mutant strain. A triple-mutant strain [ΔfliO fliP(R143H, F190L)] was made and was 6-fold more motile than the fliO deletion mutant strain. These results suggest that the suppressor mutations in the fliP, clpP, and fliA genes act in independent pathways to bypass the loss of FliO.

TABLE 3.

Swimming rates of strains bearing a fliO deletion mutation with other mutations or harboring plasmids carrying genes encoding flagellar proteins

| Strain | Genotype or description | Swimming rate (mm h−1)a |

|---|---|---|

| SJW1103 | Wild type | 7.0 ± 0.1 |

| CB187 | ΔfliO | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| CB443 | ΔfliO clpP(V20F) | 1.7 ± 0.0* |

| CB502 | ΔfliO fliA(+36T→C) | 1.6 ± 0.0* |

| CB281 | ΔfliO fliP(R143H) | 1.0 ± 0.1* |

| CB282 | ΔfliO fliP(F190L) | 3.0 ± 0.6* |

| CB447 | ΔfliO fliP(R143H) clpP(V20F) | 3.0 ± 0.1* |

| CB599 | ΔfliO fliA(+36T→C) clpP(V20F) | 1.9 ± 0.1* |

| CB590 | ΔfliO fliP(R143H) fliA(+36T→C) | 2.2 ± 0.1* |

| CB591 | ΔfliO fliP(F190L) fliA(+36T→C) | 5.5 ± 0.3* |

| CB597 | ΔfliO fliP(R143H, F190L) | 4.5 ± 0.2* |

| CB598 | ΔfliO fliP(R143H, F190L) fliA(+36T→C) | 6.7 ± 0.1* |

| CB432 | ΔfliO ΔclpA | 0.6 ± 0.0 |

| CB433 | ΔfliO Δ(clpP-clpX) | 2.3 ± 0.1* |

| CB506 | ΔfliO ΔclpX | 1.7 ± 0.1* |

| CB821 | ΔfliO ΔflgM | 1.5 ± 0.1* |

| CB558 | fliA(+36T→C) | 7.7 ± 0.1 |

| SJW1368 | Δ(cheW-flhD) | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| SJW1103 | Wild type + pTrc99A-FF4 (empty plasmid vector) | 6.3 ± 0.1 |

| CB187 | ΔfliO mutant + pTrc99A-FF4 (empty plasmid vector) | 0.6 ± 0.0 |

| CB187 | ΔfliO mutant + pCB587 (flhDC) | 1.2 ± 0.0* |

| CB187 | ΔfliO mutant + pCB568 (fliA for σ28) | 1.3 ± 0.0* |

| CB187 | ΔfliO mutant + pCB569 (fliZ) | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| CB187 | ΔfliO mutant + pCB659 (fliC) | 0.6 ± 0.0 |

| CB187 | ΔfliO mutant + pCB660 (fliS) | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| CB187 | ΔfliO mutant + pCB661 (fliS and fliC) | 0.6 ± 0.0 |

Swimming rates in soft tryptone agar (0.35% [wt/vol] agar) were determined independently at least four times for each strain by measuring the increase in the diameter of the swim ring over time. Means and standard deviations are shown. An asterisk indicates that the swimming rate of a strain with a fliO deletion mutation either with an additional mutation(s) or harboring a plasmid is significantly different (P < 0.05) from the swimming rate of the mutant strain with only the fliO deletion mutation. The swimming rates of the strains were compared using Student's t test.

The suppressor mutant strain CB191 was a ΔfliO fliP(R143H) clpP(V20F) triple-mutant strain. Strain CB447 was made to have the same genotype by lambda Red homologous recombination to confirm the results of the genome sequence analysis. CB191 and CB447 were equally motile (data not shown). They proved to be significantly more motile than either the ΔfliO fliP(R143H) or ΔfliO clpP(V20F) double-mutant strain (Table 3). Since a cooperative effect was observed for the fliP(R143H) mutation with either the fliP(F190L) or clpP(V20F) mutation, we looked to see if other suppressor mutations were also additive (Table 3). This was done to see whether it would be possible to completely bypass the function of fliO. The effect of the fliA(+36T→C) allele in combination with either the clpP(V20F), fliP(R143H), or fliP(F190L) allele was additive. Impressively, a ΔfliO fliP(R143H, F190L) fliA(+36T→C) quadruple-mutant strain was almost as motile (6.7 ± 0.1 mm h−1) as the wild type. Surprisingly, a strain bearing the fliA(+36T→C) mutation alone was slightly yet significantly (P < 0.05) more motile (7.7 ± 0.1 mm h−1) than the wild type. These results suggest that it is almost possible to compensate for the loss of fliO function by combining the suppressor mutations in the fliP, fliA, and clpP genes and that the fliA(+36T→C) allele is more active than the native fliA gene.

The ClpP peptidase subunit has two AAA+ ATPase binding partners, ClpA and ClpX, which direct the specificity of the protease complexes ClpAP and ClpXP, respectively (36). The ClpXP protease, but not the ClpAP protease, is known to regulate the cellular level of FlhD4FlhC2 (35). Accordingly, strains bearing clpA, clpP-clpX, or clpX gene deletion mutations together with the fliO deletion mutation were constructed (Table 3). The fliO clpA double-deletion mutant strain was similarly motile to the fliO deletion mutant strain. The clpX or clpP-clpX deletion mutation increased the motility of strains bearing a fliO deletion mutation similarly to the case with the clpP(V20F) mutation. This suggests that inactivation of the ClpXP protease, but not the ClpAP protease, can rescue motility of cells bearing a fliO deletion mutation. The flgM gene encodes a negative regulator of σ28 (37). A fliO flgM double-deletion mutant strain was significantly more motile (P < 0.05) than a fliO deletion mutant strain. This suggests that increased activity of σ28 can rescue motility of cells bearing a fliO deletion mutation.

The clpP and fliA genes encode regulators of flagellar gene expression. Consequently, we investigated whether increased expression of the flagellar transcription factor FlhD4FlhC2, FliZ, or σ28 would rescue motility of the fliO deletion mutant strain. Also, we investigated whether increased expression (and supply) of flagellin (encoded by fliC) or the chaperone protein for flagellin (encoded by fliS) separately or together would bypass the loss of fliO function. Plasmids carrying the flhDC, fliA, fliZ, fliC, fliS, or fliS and fliC genes were made. Synthesis of FlhD4FlhC2, σ28, FliZ, or FliS by strains harboring these plasmids was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie brilliant blue staining or, in the case of FliS, by immunoblot analysis (data not shown). Motility of the fliO deletion mutant strain in soft tryptone agar was rescued 2-fold (P < 0.05) by plasmids carrying the flhDC or fliA gene but not by those carrying the other genes (Table 3). These results suggest that increased expression of all flagellar genes or increased expression of class 3 flagellar and chemotaxis genes can partially bypass the loss of fliO function but that an increased supply of flagellin is not sufficient.

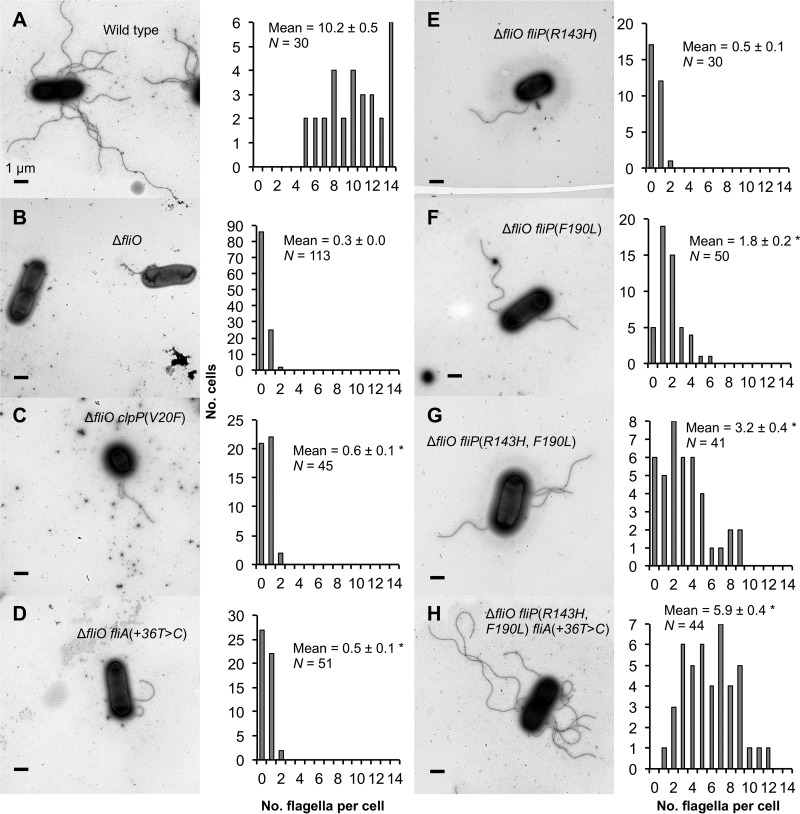

We examined the swimming of cells of the fliO deletion mutant strain and strains bearing additional mutations by using phase-contrast microscopy. Results are presented in Movie S1 and Movie S2 in the supplemental material. Motility of the cells in liquid medium and population heterogeneity can be observed. A small number of cells of the fliO deletion mutant strain were motile, but most exhibited only Brownian motion. The proportion of motile cells was slightly increased by the fliA(+36T→C) or fliP(R143H) suppressor mutation. However, the fliP(F190L) mutation had a greater effect, and most cells of the ΔfliO fliP(F190L) double-mutant strain were motile. Almost all cells of the ΔfliO fliP(R143H, F190L) triple-mutant strain and ΔfliO fliP(R143H, F190L) fliA(+36T→C) quadruple-mutant strain were motile, and motility was close to that of the wild type. These results suggest that cells with a fliO deletion mutation produce functional flagella with a low probability and that the probability of producing flagella is increased additively by the suppressor mutations.

Suppressor mutations rescued biosynthesis of flagella for strains bearing a fliO deletion mutation.

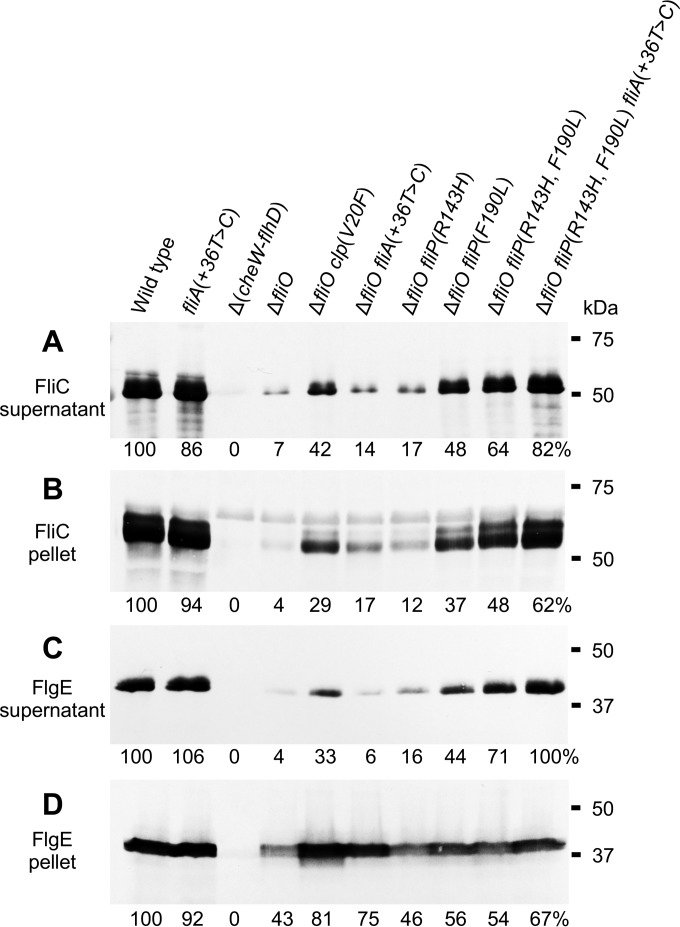

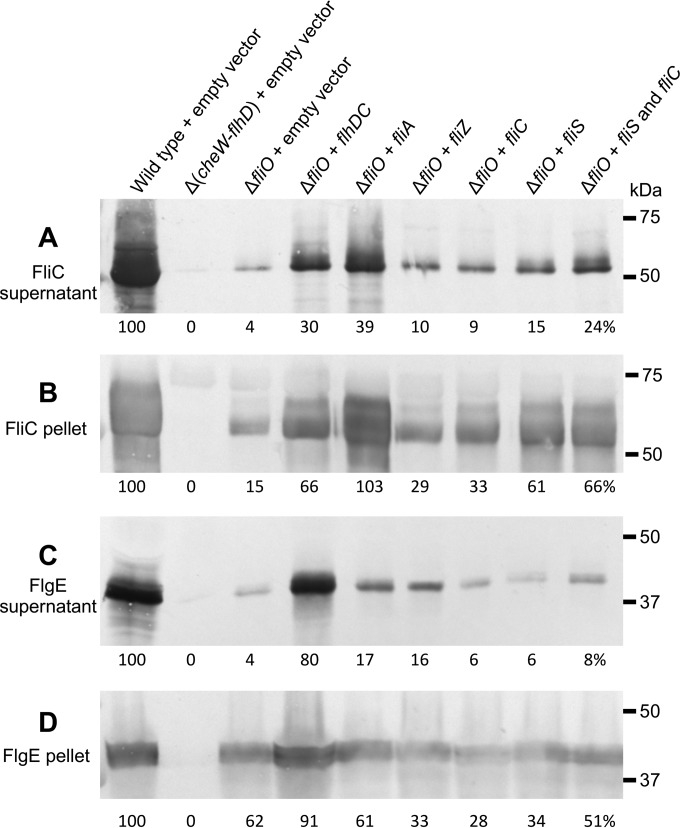

Using immunoblot analysis of flagellin (FliC) and hook (FlgE) proteins made within cells and exported into the culture supernatant, we investigated the biosynthesis of the flagella (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). For the fliO deletion mutant strain, FliC and FlgE were exported into the culture supernatant at less than 10% of the wild-type levels. The clpP(V20F), fliA(+36T→C), fliP(R143H), and fliP(F190L) suppressor mutations all partially rescued export of the flagellar proteins (Fig. 1). The fliP(F190L) mutation had the greatest effect, which was consistent with earlier observations of motility. The ΔfliO fliP(R143H, F190L) triple-mutant strain and ΔfliO fliP(R143H, F190L) fliA(+36T→C) quadruple-mutant strain exported more FliC and FlgE than the double-mutant strains. The quadruple-mutant strain made and exported these proteins at about two-thirds of the wild-type levels. The strain bearing only a fliA(+36T→C) mutation made and exported FlgE and FliC normally. These results suggest that cells bearing a fliO deletion mutation produced few flagella but that biosynthesis of flagella was rescued by suppressor mutations [fliP(R143H), fliP(F190L), clpP(V20F), and fliA(+36T→C)] that increased the formation of hook-basal body complexes or that activated expression of class 3 flagellar and chemotaxis genes.

FIG 1.

Export of flagellar proteins is rescued by extragenic suppressor mutations in strains bearing a fliO deletion mutation. The strains included were SJW1103 (wild type), CB558 [fliA(+36T→C)], SJW1368 (ΔcheW-flhD), CB187 (ΔfliO), CB443 [ΔfliO clpP(V20F)], CB502 [ΔfliO fliA(+36T→C)], CB281 [ΔfliO fliP(R143H)], CB282 [ΔfliO fliP(F190L)], CB597 [ΔfliO fliP(R143H, F190L)], and CB598 [ΔfliO fliP(R143H, F190L) fliA(+36T→C)]. (A and B) Immunoblot analyses of flagellin (FliC; 52 kDa) levels for cultures of the strains fractionated into supernatant (A) and cell pellet (B) fractions. (C and D) Immunoblot analyses of hook protein (FlgE; 42 kDa) levels in culture supernatant (C) and cell pellet (D) fractions. Polyclonal antibodies for FliC or FlgE were used. The numbers below each lane indicate the relative band densities (%) compared to those of the wild type.

FIG 2.

Export of flagellar proteins is rescued by plasmids carrying genes encoding flagellar regulators in strains bearing a fliO deletion mutation. The strains included were SJW1103 (wild type), SJW1368 (ΔcheW-flhD), and CB187 (ΔfliO). The strains harbored the following plasmids carrying the indicated genes: pTrc99A-FF4 (empty plasmid vector), pCB587 (flhDC), pCB568 (fliA), pCB569 (fliZ), pCB659 (fliC), pCB660 (fliS), and pCB661 (fliS plus fliC). (A and B) Immunoblot analyses of flagellin (FliC; 52 kDa) levels for cultures of the strains fractionated into supernatant (A) and cell pellet (B) fractions. (C and D) Immunoblot analyses of hook protein (FlgE; 42 kDa) in culture supernatant (C) and cell pellet (D) fractions. Polyclonal antibodies for FliC or FlgE were used. The numbers below each lane indicate the relative band densities (%) compared to those of the wild type.

Expression of flhDC, fliA, or fliS plus fliC in the fliO deletion mutant strain increased FliC export to a much greater extent than expression of fliZ, fliS alone, or fliC alone (Fig. 2). However, expression of fliS with fliC did not increase motility for cells bearing a fliO deletion mutation, but expression of flhDC or fliA did (Table 3). Expression of flhDC in the fliO deletion mutant strain greatly increased FlgE export in comparison to the expression of other genes, although there was a small increase of FlgE export caused by fliA or fliZ gene expression (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that for cells bearing a fliO deletion mutation, expression of flhDC markedly increased the formation of hook-basal body complexes and expression of fliA activated expression of class 3 flagellar and chemotaxis genes.

We also examined the biosynthesis of flagella for several strains by using transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 3). Most cells of the fliO deletion mutant strain lacked flagella, but some made one or two flagella. Flagella of the fliO deletion mutant strain were about 3% as abundant as those of the wild type. The proportion of cells producing one or two flagella was increased about 2-fold (P < 0.05) for the ΔfliO fliA(+36T→C) and ΔfliO clpP(V20F) double-mutant strains compared to the fliO deletion mutant strain. However, the ΔfliO fliP(R143H) double-mutant strain did not produce significantly more flagella than the fliO deletion mutant strain. The ΔfliO fliP(F190L) double-mutant strain produced increased numbers of flagella per cell relative to the fliO deletion mutant strain, and flagella were about 18% as abundant as the case for the wild type. The effects of the suppressor mutations were additive: flagella of the ΔfliO fliP(R143H, F190L) triple-mutant strain were 31% as abundant as those of the wild type, and flagella of the ΔfliO fliA(+36T→C) fliP(R143H, F190L) quadruple-mutant strain were 58% as abundant as those of the wild type.

FIG 3.

Biosynthesis of flagella is rescued by extragenic suppressor mutations in strains bearing a fliO deletion mutation. Negatively stained transmission electron micrograph images are shown for the following strains: SJW1103 (wild type) (A), CB187 (ΔfliO) (B), CB443 [ΔfliO clpP(V20F)] (C), CB502 [ΔfliO fliA(+36T→C)] (D), CB281 [ΔfliO fliP(R143H)] (E), CB282 [ΔfliO fliP(F190L)] (F), CB597 [ΔfliO fliP(R143H, F190L)] (G), and CB598 [ΔfliO fliP(R143H, F190L) fliA(+36T→C)] (H). Representative cells are shown for each strain. Lengths of flagella varied from cell to cell. Bars, 1 μm. Histograms to the right of each image display the number of cells (y axis) producing the indicated numbers of flagella per cell (x axis). The means and standard errors of the numbers of flagella per cell are shown. N, number of cells inspected for each strain. Asterisks indicate cases where the numbers of flagella were significantly (P < 0.05) higher for strains bearing a fliO deletion mutation with suppressor mutations than for the mutant strain with the fliO deletion mutation only. The data were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney U test.

FliP R143H and F190L mutants were made normally.

It was important to know whether the fliP(R143H) or fliP(F190L) suppressor mutation affected FliP synthesis. To investigate FliP synthesis, an antiserum containing polyclonal antibodies against FliP was made. Strains harboring plasmids carrying either fliP and fliO, fliP only, fliP(R143H), or fliP(F190L) were grown to late exponential phase and harvested. Immunoblot analysis of lysed cells with the FliP antiserum determined that similar amounts of wild-type FliP and FliP R143H and F190L mutant proteins were made and that the expression level of FliP was unaffected by FliO (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

The fliA(+36T→C) synonymous mutation increased expression and translation of fliAZY mRNA.

The fliA gene is part of the fliAZY operon, which is under expression control of class 2 and class 3 promoters. The P1 mRNA is for σ28 and FliZ translation, and the P2 mRNA is for FliZ translation (5). To understand the mechanism of suppression by the fliA(+36T→C) allele, it was important to determine whether the synonymous mutation increased expression of the fliAZY operon and/or translation of σ28 from either P1 or P2 mRNA.

Transcriptional fusions of the fliAZY operon promoter region to the lacZ gene, carried by a single-copy promoter probe vector, have been studied previously (4). In this study, similar transcriptional fusions were made for the fliAZY operon promoter region with or without the fliA(+36T→C) mutation. β-Galactosidase activity was measured in various genetic backgrounds (Table 4). A 16% increase (P < 0.05) in mean enzyme activity was measured within the fliO deletion mutant strain for the transcriptional fusion with the fliA(+36T→C) mutation compared to the transcriptional fusion to the native fliAZY operon promoter region. Also, the activity of operon fusions with or without the synonymous mutation was increased 1.5- to 2-fold (P < 0.05) within the ΔfliO clpP(V20F) or ΔfliO Δ(clpP-clpX) double-mutant strain compared to the activity within the fliO deletion mutant strain. These results suggest that the fliA(+36T→C) mutation produced a small increase in mRNA stability or fliAZY expression, and for cells bearing a fliO deletion mutation, fliAZY expression was increased by inactivation of the ClpXP protease.

TABLE 4.

Activity of fliAZY operon and fliA gene fusions to the lacZ gene

| Fusion and strain | LacZ activity (Miller units) of the strain harboring the indicated plasmida | Statistical significance (P value)b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional fusion of the fliAZY operon promoter region to the lacZ gene | pCB572, native |

pCB573, +36T→C mutation |

|

| Wild type | 350 ± 30 | 410 ± 80 | 0.01 |

| ΔfliO mutant | 395 ± 90 | 460 ± 120 | 0.03 |

| ΔfliO clpP(V20F) mutant | 770 ± 140 | 940 ± 250 | 0.01 |

| ΔfliO Δ(clpP-clpX) mutant | 600 ± 130 | 720 ± 110 | 0.01 |

| Δ(cheW-flhD) mutant | 0 ± 0 | 0 ± 0 | NS |

| Translational fusion of the fliA gene to the lacZ gene controlled by promoter 1 | pCB576, native |

pCB577, +36T→C mutation |

|

| Wild type | 1,150 ± 90 | 2,200 ± 120 | <0.01 |

| ΔfliO mutant | 1,320 ± 250 | 3,160 ± 90 | <0.01 |

| Δ(cheW-flhD) mutant | 3 ± 0 | 4 ± 0 | <0.01 |

| Translational fusion of the fliA gene to the lacZ gene controlled by promoter 2 | pCB578, native |

pCB579, +36T→C mutation |

|

| Wild type | 31 ± 1 | 51 ± 6 | <0.01 |

| ΔfliO mutant | 31 ± 1 | 37 ± 1 | <0.01 |

| Δ(cheW-flhD) mutant | 23 ± 0 | 24 ± 5 | NS |

Cells were grown to exponential phase (OD600 of 0.65) in LB medium with the appropriate antibiotic at 37°C. Measurements were made in duplicate for at least three independent cultures of each strain. Means and standard deviations are shown.

Statistical significance indicates the level of significance for differences determined by Student's t test for the enzyme activity for a fusion plasmid with the native fliAZY operon promoter region compared to the corresponding fusion plasmid with the fliAZY operon promoter region bearing the fliA(+36T→C) mutation. NS, not significant.

Translational fusions of the fliA gene to the lacZ gene under expression control of either the P1 or P2 promoter in a multicopy promoter probe vector were studied previously (5). We made similar translational fusions with and without the fliA(+36T→C) synonymous mutation and measured their activities in various strains (Table 4). The activity of β-galactosidase for a fliA′-lacZ translational fusion expressed from the P1 promoter was high and increased about 2-fold (P < 0.05) with the synonymous mutation. This was observed when the fusions were expressed within the wild-type strain or within the fliO deletion mutant strain. Activity from the P2 promoter remained low, as expected. The P2 promoter controls translation of FliZ but not σ28. However, β-galactosidase activity for a fliA′-lacZ translational fusion expressed from the P2 promoter was increased from 20 to 60% (P < 0.05) by the synonymous mutation. These results suggest that the most important effect of the fliA(+36T→C) mutation was to increase σ28 translation from fliAZY mRNA transcribed from the P1 promoter.

Expression of class 3 flagellar genes was rescued by the clpP(V20F) or fliA(+36T→C) mutation for strains bearing a fliO gene deletion.

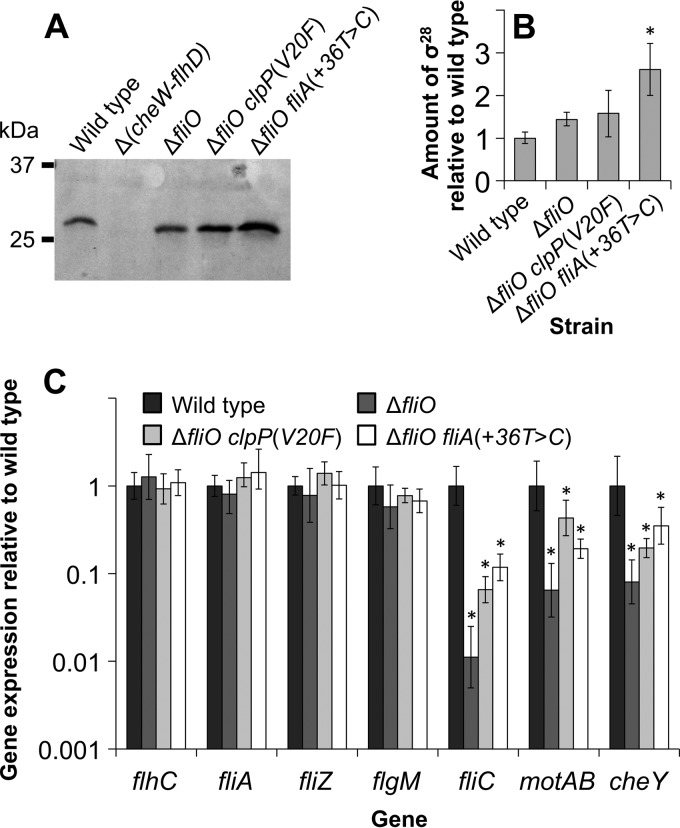

ClpXP and σ28 are regulators of flagellar gene expression. In order to understand the consequences of the clpP(V20F) and fliA(+36T→C) suppressor mutations, we examined their effects on flagellar gene expression. We analyzed synthesis of σ28 by immunoblotting lysates prepared from the wild-type strain, the fliO deletion mutant strain, the ΔfliO clpP(V20F) double-mutant strain, and the ΔfliO fliA(+36T→C) double-mutant strain (Fig. 4A and B). Surprisingly, the amounts of σ28 for the fliO deletion mutant strain and the ΔfliO clpP(V20F) double-mutant strain were not significantly different. However, σ28 was synthesized about 1.8-fold more (P < 0.05) by the ΔfliO fliA(+36T→C) double-mutant strain than by the other strains.

FIG 4.

Expression of class 3 flagellar genes is rescued by clpP(V20F) or fliA(+36T→C) mutation in strains bearing a fliO deletion mutation. (A) Synthesis of σ28 (27 kDa) was analyzed by immunoblotting using polyclonal antibodies for σ28. The following strains grown to mid-exponential phase (OD600 of 0.65) were included: SJW1103 (wild type), SJW1368 [Δ(cheW-flhD)], CB187 (ΔfliO), CB443 [ΔfliO clpP(V20F)], and CB502 [ΔfliO fliA(+36T→C)]. A typical immunoblot is shown. (B) The amount of σ28 relative to the wild-type level was determined by densitometry analysis of immunoblots for three cultures of each strain. Error bars represent standard deviations. The asterisk indicates that the amount of σ28 was significantly (P < 0.05) increased for the fliO fliA(+36T→C) double-mutant strain compared to the fliO deletion mutant strain. (C) Comparison of mRNA levels of flagellar genes by real-time quantitative RT-PCR. For each strain, three cultures were grown to mid-exponential phase (OD600 of 0.65) for total RNA purification. The comparative threshold cycle (CT) method for relative quantification was used to analyze the results. Error bars represent relative quantification minimum and maximum levels (range of 95% confidence). Asterisks above bars indicate that the mRNA level was significantly reduced (P < 0.05) for the fliO deletion mutant strain compared to the wild type or that the mRNA level was significantly increased for the ΔfliO clpP(V20F) or ΔfliO fliA(+36T→C) double-mutant strain compared to the fliO deletion mutant strain.

mRNA levels for genes of the flagellar regulon were profiled for the four strains by real-time qRT-PCR (Fig. 4C). The flhC gene (of the flhDC operon) is under expression control of a class 1 promoter. The fliA and fliZ genes and the flgM gene (of the flgAMN operon) are under expression control of class 2 and class 3 promoters. The motAB genes (of the motAB-cheAW operon), the cheY gene (of the tar-cheRBYZ operon), and the fliC gene are under expression control of class 3 promoters. Expression of the flhC, fliA, fliZ, and flgM genes was similar for the four strains. Compared to the wild-type levels, mRNA levels of the cheY, motA, and fliC genes were significantly (P < 0.05) reduced for the fliO deletion mutant strain. Levels of mRNA for these class 3 genes were significantly increased for the ΔfliO clpP(V20F) and ΔfliO fliA(+36T→C) double-mutant strains in comparison to the fliO deletion mutant strain, although not compared to the wild type.

DISCUSSION

The FliO protein is required for efficient biosynthesis of the S. enterica flagellum. A fliO deletion mutant strain synthesizes flagella with a low probability (about 3% of the wild-type level). Previously, we showed that extragenic mutations in the fliP gene [fliP(R143H) or fliP(F190L)] partially bypass a loss of fliO function (15). Here we identified new mutations in regulators of flagellar genes [clpP(V20F) and fliA(+36T→C)] that also partially bypass a loss of fliO function. The suppressor mutations acted cooperatively with each other to promote flagellar assembly and motility. The ΔfliO fliP(R143H, F190L) fliA(+36T→C) quadruple-mutant strain assembled about 60% of wild-type flagellar numbers and was nearly fully motile.

After processing of the N-terminal domain, the clpP(V20F) allele produces a mature ClpP V6F mutant protein. Fortuitously, crystal structures of E. coli ClpP and a ClpP V6A mutant have been solved (36). The N-terminal domain of ClpP forms a β-hairpin conformation that was disrupted in the V6A mutant and prevented interaction with ATPase. Since the amino acid sequences of the mature ClpP proteins from E. coli and S. enterica can be aligned with 99% identity over their 193-amino-acid length, this suggests that the structure of the N-terminal domain of the ClpP V6F mutant protein is also disrupted. Deletion of the clpP-clpX genes or the clpX gene alone bypasses fliO function, which confirms that the clpP(V20F) allele is a loss-of-function mutation.

Our analysis of the β-galactosidase activity of fliAZY-lacZ operon fusions suggests that the fliA(+36T→C) synonymous mutation has a small effect on either gene expression or mRNA stability. However, analysis of the β-galactosidase activity for fliA′-lacZ gene fusions showed that the fliA(+36T→C) mutation increases mRNA translation 2-fold and that σ28 levels correspondingly increase. Recently, Chevance et al. (38) showed the significance of synonymous mutations for in vivo translation speed and observed that the effects of synonymous mutations are not neutral. Surprisingly, the fliA(+36T→C) mutation even increased the motility of the strain that bore this mutation alone compared to that of the wild-type strain.

These results suggest that an overall increase in expression of flagellar genes can partially bypass the function of fliO and rescue flagellar assembly and function. It has been predicted that inactivating the ClpXP protease should increase the expression of class 2 and class 3 flagellar genes by reducing the proteolysis of FlhD4FlhC2 (35). A plasmid carrying the flhDC genes partly recovered motility of a fliO deletion mutant strain. In addition, we observed increased synthesis and export of hook protein for the fliO deletion mutant strain harboring a plasmid carrying the flhDC genes. This suggests that an increased production of hook-basal body complexes accompanied the partially recovered motility, as observed with increased flhDC expression (39). Motility and biosynthesis of flagella of a fliO deletion mutant strain were also rescued by increased synthesis of σ28 from a plasmid carrying the fliA gene or by deletion of the flgM gene, encoding FlgM, the negative regulator of σ28. On the other hand, motility of a fliO deletion mutant strain could not be complemented by a plasmid carrying the fliS and fliC genes, despite increased export of flagellin. The fliA(+36T→C) and clpP(V20F) mutations rescued expression of class 3 flagellar genes and chemotaxis genes, including fliC, motAB, and cheY. This suggests not only that an increased supply of flagellin is required to bypass a loss of fliO function but also that a general increase in expression of class 3 genes is required. Thus, without fliO, motility and flagellar biosynthesis can be increased by the synthesis of components of the flagellum made after the hook-basal body complex is completed.

Previously, other studies showed suppression of a defect in flagellar biosynthesis from mutations in various flagellar genes by increased levels of FlhD4FlhC2. Aldridge et al. (40) isolated suppressor mutant strains produced by an flgN mutant strain that bore loss-of-function mutations in the clpX and fliT genes. Also, Erhardt and Hughes (39) found that mutations that increased expression of the flhDC operon bypassed the requirement for the cytoplasmic C-ring of the flagellum. One category of mutation was the unstable duplication of the region of the chromosome carrying the flhDC operon, which increased expression of the flhDC operon. Such chromosomal duplications would not be detected in our analysis of single nucleotide polymorphisms between the genome sequences of the suppressor mutant strains. No mutations were identified for the suppressor mutant strains CB228, CB229, and CB230 isolated in this study, and the rescued motility was transient. Therefore, chromosomal duplications may have bypassed fliO function in these strains.

The fliP(F190L) mutation was the most effective suppressor mutation: it rescued the number of flagella per cell as well as the proportion of cells producing flagella. Moreover, the ΔfliO fliP(R143H, F190L) triple-mutant strain produced about one-third of the wild-type number of flagella. This suggests that the function of FliO is most associated with regulation of FliP. Polyclonal antibodies to FliP were produced in this study so that expression of native (untagged) FliP could be measured. The fliP(R143H) or fliP(F190L) mutation did not affect the level of expression of FliP, and the expression of FliP was not affected by FliO synthesis. This suggests that our previous conclusion that FliO regulates FliP stability is incorrect (15). The function of FliO therefore remains a matter of speculation. The fliP(R143H) or fliP(F190L) mutation does not produce amino acid substitutions in FliP that correspond to the amino acid residues present in FliP homologs found in the flagellum of A. aeolicus or in the injectisomes (15). One possibility for FliO function is that it acts as a coupling protein, promoting the association of FliP with other components of the export apparatus and basal body during assembly. FliO was among the flagellar proteins required for subcellular localization of an FlhA-cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) fusion protein, suggesting a role for FliO in basal body assembly (41). This may explain why increased expression of flagellar proteins can partially bypass a loss of fliO function by increasing the probability of protein-protein interactions. Future studies should address whether FliO and FliP interact directly, whether FliO is found within the basal body pore, and also which proteins bind to the cytoplasmic domain of FliO.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded directly by the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST).

We thank the OIST DNA Sequencing Center for sequencing the genomes of Salmonella strains, and especially Hiroki Goto and Manabu Fujie for DNA sequence data analysis. We thank Shin-Ichi Aizawa (Prefectural University of Hiroshima) for advising the transmission electron microscopy and motion analysis experiments and Toshio Sasaki (OIST) for help with transmission electron microscopy. We thank Kenichi Sajiki and Takeshi Noda (OIST) for advice with RNA preparation and quantitative real-time RT-PCR. We thank Kelly T. Hughes (University of Utah) for the gift of anti-σ28 antibodies and for the design of the flgM deletion mutation and Tohru Minamino (Osaka University) for anti-FliC and anti-FlgE antibodies. We thank Steven D. Aird (OIST) and Denise Dehnbostel for critical readings of the manuscript. We also thank the Graduate School of Frontier Biosciences (Osaka University), the Escherichia coli Genetic Stock Center (Yale University), the Salmonella Genetic Stock Center (University of Calgary), and the National BioResource Project (National Institute of Genetics, Japan) for providing strains and plasmids.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 8 September 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.02184-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Macnab RM. 2003. How bacteria assemble flagella. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:77–100. 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harshey RM. 2003. Bacterial motility on a surface: many ways to a common goal. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:249–273. 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.091014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chevance FF, Hughes KT. 2008. Coordinating assembly of a bacterial macromolecular machine. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:455–465. 10.1038/nrmicro1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wada T, Tanabe Y, Kutsukake K. 2011. FliZ acts as a repressor of the ydiV gene, which encodes an anti-FlhD4FlhC2 factor of the flagellar regulon in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 193:5191–5198. 10.1128/JB.05441-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanabe Y, Wada T, Ono K, Abo T, Kutsukake K. 2011. The transcript from the σ28-dependent promoter is translationally inert in the expression of the σ28-encoding gene fliA in the fliAZ operon of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 193:6132–6141. 10.1128/JB.05909-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erhardt M, Namba K, Hughes KT. 2010. Bacterial nanomachines; the flagellum and the type III injectisome. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2:a000299. 10.1101/cshperspect.a000299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minamino T, Namba K. 2008. Distinct roles of the FliI ATPase and proton motive force in bacterial flagellar protein export. Nature 451:485–488. 10.1038/nature06449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paul K, Erhardt M, Hirano T, Blair DF, Hughes KT. 2008. Energy source of flagellar type III secretion. Nature 451:489–492. 10.1038/nature06497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minamino T. 2014. Protein export through the bacterial flagellar type III export pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1843:1642–1648. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohnishi K, Fan F, Schoenhals GJ, Kihara M, Macnab RM. 1997. The FliO, FliP, FliQ, and FliR proteins of Salmonella typhimurium: putative components for flagellar assembly. J. Bacteriol. 179:6092–6099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fan F, Ohnishi K, Francis NR, Macnab RM. 1997. The FliP and FliR proteins of Salmonella typhimurium, putative components of the type III flagellar export apparatus, are located in the flagellar basal body. Mol. Microbiol. 26:1035–1046. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6412010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aizawa S. 2014. The flagellar world: electron microscopic images of bacterial flagella and related surface structures, 1st ed. Academic Press, Elsevier Inc, Waltham, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsang J, Hoover TR. 2014. Requirement of the flagellar protein export apparatus component FliO for optimal expression of flagellar genes in Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 196:2709–2717. 10.1128/JB.01332-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pallen MJ, Penn CW, Chaudhuri RR. 2005. Bacterial flagellar diversity in the post-genomic era. Trends Microbiol. 13:143–149. 10.1016/j.tim.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barker CS, Meshcheryakova IV, Kostyukova AS, Samatey FA. 2010. FliO regulation of FliP in the formation of the Salmonella enterica flagellum. PLoS Genet. 6:e1001143. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamaguchi S, Fujita H, Sugata K, Taira T, Iino T. 1984. Genetic analysis of H2, the structural gene for phase-2 flagellin in Salmonella. J. Gen. Microbiol. 130:255–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryu J, Hartin RJ. 1990. Quick transformation in Salmonella typhimurium LT2. Biotechniques 8:43–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang W, Metcalf WW, Lee KS, Wanner BL. 1995. Molecular cloning, mapping, and regulation of Pho regulon genes for phosphonate breakdown by the phosphonatase pathway of Salmonella typhimurium LT2. J. Bacteriol. 177:6411–6421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohnishi K, Ohto Y, Aizawa S, Macnab RM, Iino T. 1994. FlgD is a scaffolding protein needed for flagellar hook assembly in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 176:2272–2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640–6645. 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cherepanov PP, Wackernagel W. 1995. Gene disruption in Escherichia coli: TcR and KmR cassettes with the option Flp-catalyzed excision of the antibiotic-resistance determinant. Gene 158:9–14. 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00193-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koop AH, Hartley ME, Bourgeois S. 1987. A low-copy-number vector utilizing β-galactosidase for the analysis of gene control elements. Gene 52:245–256. 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Casadaban MJ, Chou J, Cohen SN. 1980. In vitro gene fusions that join an enzymatically active β-galactosidase segment to amino-terminal fragments of exogenous proteins: Escherichia coli plasmid vectors for the detection and cloning of translational initiation signals. J. Bacteriol. 143:971–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karlinsey JE. 2007. λ-Red genetic engineering in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Methods Enzymol. 421:199–209. 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)21016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toker AS, Kihara M, Macnab RM. 1996. Deletion analysis of the FliM flagellar switch protein of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 178:7069–7079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qi J, Zhao F, Buboltz A, Schuster SC. 2010. inGAP: an integrated next-generation genome analysis pipeline. Bioinformatics 26:127–129. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fraser GM, Hirano T, Ferris HU, Devgan LL, Kihara M, Macnab RM. 2003. Substrate specificity of type III flagellar protein export in Salmonella is controlled by subdomain interactions in FlhB. Mol. Microbiol. 48:1043–1057. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bornhorst JA, Falke JJ. 2000. Purification of proteins using polyhistidine affinity tags. Methods Enzymol. 326:245–254. 10.1016/S0076-6879(00)26058-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karlinsey JE, Tanaka S, Bettenworth V, Yamaguchi S, Boos W, Aizawa S, Hughes KT. 2000. Completion of the hook-basal body complex of the Salmonella typhimurium flagellum is coupled to FlgM secretion and fliC transcription. Mol. Microbiol. 37:1220–1231. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minamino T, Macnab RM. 1999. Components of the Salmonella flagellar export apparatus and classification of export substrates. J. Bacteriol. 181:1388–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller J. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wozniak CE, Chevance FF, Hughes KT. 2010. Multiple promoters contribute to swarming and the coordination of transcription with flagellar assembly in Salmonella. J. Bacteriol. 192:4752–4762. 10.1128/JB.00093-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomoyasu T, Takaya A, Isogai E, Yamamoto T. 2003. Turnover of FlhD and FlhC, master regulator proteins for Salmonella flagellum biogenesis, by the ATP-dependent ClpXP protease. Mol. Microbiol. 48:443–452. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bewley MC, Graziano V, Griffin K, Flanagan JM. 2006. The asymmetry in the mature amino-terminus of ClpP facilitates a local symmetry match in ClpAP and ClpXP complexes. J. Struct. Biol. 153:113–128. 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kutsukake K, Iino T. 1994. Role of the FliA-FlgM regulatory system on the transcriptional control of the flagellar regulon and flagellar formation in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 176:3598–3605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chevance FF, Le Guyon S, Hughes KT. 2014. The effects of codon context on in vivo translation speed. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004392. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Erhardt M, Hughes KT. 2010. C-ring requirement in flagellar type III secretion is bypassed by FlhDC upregulation. Mol. Microbiol. 75:376–393. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06973.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aldridge P, Karlinsey J, Hughes KT. 2003. The type III secretion chaperone FlgN regulates flagellar assembly via a negative feedback loop containing its chaperone substrates FlgK and FlgL. Mol. Microbiol. 49:1333–1345. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morimoto YV, Ito M, Hiraoka KD, Che YS, Bai F, Kami-Ike N, Namba K, Minamino T. 2014. Assembly and stoichiometry of FliF and FlhA in Salmonella flagellar basal body. Mol. Microbiol. 91:1214–1226. 10.1111/mmi.12529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.