Abstract

CTXΦ, a filamentous vibriophage encoding cholera toxin, uses a unique strategy for its lysogeny. The single-stranded phage genome forms intramolecular base-pairing interactions between two inversely oriented XerC and XerD binding sites (XBS) and generates a functional phage attachment site, attP(+), for integration. The attP(+) structure is recognized by the host-encoded tyrosine recombinases XerC and XerD (XerCD), which enables irreversible integration of CTXΦ into the chromosome dimer resolution site (dif) of Vibrio cholerae. The dif site and the XerCD recombinases are widely conserved in bacteria. We took advantage of these conserved attributes to develop a broad-host-range integrative expression vector that could irreversibly integrate into the host chromosome using XerCD recombinases without altering the function of any known open reading frame (ORF). In this study, we engineered two different arabinose-inducible expression vectors, pBD62 and pBD66, using XBS of CTXΦ. pBD62 replicates conditionally and integrates efficiently into the dif of the bacterial chromosome by site-specific recombination using host-encoded XerCD recombinases. The expression level of the gene of interest could be controlled through the PBAD promoter by modulating the functions of the vector-encoded transcriptional factor AraC. We validated the irreversible integration of pBD62 into a wide range of pathogenic and nonpathogenic bacteria, such as V. cholerae, Vibrio fluvialis, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica, and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Gene expression from the PBAD promoter of integrated vectors was confirmed in V. cholerae using the well-studied reporter genes mCherry, eGFP, and lacZ.

INTRODUCTION

Phages and plasmids are the most abundant and best-studied extrachromosomal genetic elements (1, 2). Although both elements are major sources of virulence factors and antibiotic resistance in bacterial pathogens and cause major problems for infectious disease management, they have made important contributions to genetic engineering and therefore to understanding genome functions. At present, plasmids are indispensable tools for laboratories studying in vivo or in vitro gene functions by creating knockout strains, producing RNAs, and purifying recombinant proteins (3, 4).

The best way to study in vivo gene functions in any bacterium is to select a stable expression vector for which both vector copy numbers and the expression module can be tightly controlled by endogenous transcriptional machinery. Autonomously replicating plasmids carrying a piece of DNA of interest are frequently used in bacterial cells to explore predicted gene functions and to complement reverse-genetic experiments and in silico analyses (3). However, different plasmids have different host specificities for their replication, and most plasmids are not stable in distally related bacterial cells (2, 4). This is one of the major limitations in the use of autonomously replicating plasmids to study gene functions in bacterial cells. Nevertheless, the copy numbers of replicating plasmids are always higher than those of the host chromosome, which often creates difficulties in studying gene functions if the selected gene is directly or indirectly linked to toxin production. Moreover, the stable inheritance of plasmids, even in the native host cells, is possible only in the presence of selection pressure, which compromises optimal growth conditions.

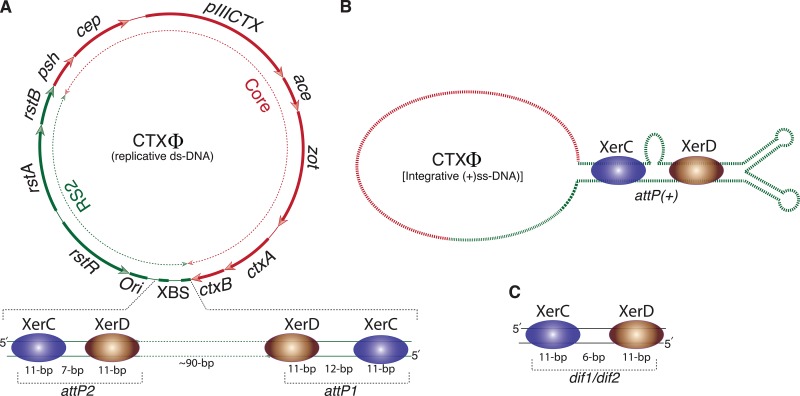

Bacteriophages are also widely used for genetic manipulation and for studying gene functions, but direct use of native phage particles also has several limitations (5, 6). CTXΦ, a lysogenic filamentous bacteriophage that belongs to the viral family Inoviridae, has a unique mode of lysogeny (5). The ∼7.0-kb genome of CTXΦ is structured in two distinct functional modules: repeat sequence 2 (RS2) and core (Fig. 1). The RS2 module harbors three genes that directly participate in CTXΦ replication, integration, and transcription regulation (Fig. 1) (6). The core region-encoded proteins are essential for phage morphogenesis and toxin production (5). CTXΦ integrates into the chromosome dimer resolution site (dif) of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae, which is the only site used for this integration (7). Unlike most other lysogenic phages, CTXΦ uses its folded plus-single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) genome for integration (Fig. 1). Integration of CTXΦ is irreversible (8). The genome of CTXΦ does not encode any DNA recombinase but exploits two host-encoded tyrosine recombinases, XerC and XerD (XerCD), to integrate at dif1 or dif2, the two chromosome dimer resolution sites of the cholera pathogen (9). Both the recombinases XerCD and the dif sites are highly conserved across bacterial phyla (10). All reported dif sites consist of an 11-bp binding site for XerC and XerD separated by a 6-bp overlap region at the border of which strand exchanges occur (11). The double-stranded replicative genome of CTXΦ harbors two inversely oriented XerCD binding sites (XBS), attP1 and attP2 (Fig. 1A). Neither attP1 nor attP2 is suitable for XerCD-mediated integration. In the single-stranded phage genome, an ∼150-bp region encompassing attP1 and attP2 forms intrastrand base pairing, which creates a functional XerCD binding site, attP(+) (8). Recent reports have demonstrated that Escherichia coli-encoded XerCD can also recognize the attP(+) structure and mediate CTXΦ integration in both dif of E. coli and dif1 of V. cholerae (7, 9). The XerCD-mediated integration of CTXΦ follows a sequential strand exchange between dif1 and attP(+) sites within a nucleoprotein complex consisting of one pair of each recombinase and two DNA fragments. During recombination, both the DNA and protein components of the synaptic complex remain transiently interconnected. Within the synaptic complex, both activated recombinases catalyze cleavage of a phosphodiester bond immediately 3′ to their binding sites. First, cleavage generates a phosphotyrosyl-linked recombinase-DNA complex at the recombinase binding side and free 5′-hydroxyl edges on the other side. Following cleavage, the liberated bases with 5′-hydroxyl extremities of the central regions of the dif1 and attP(+) sites melt from their complementary strand and react with the recombinase-DNA phosphotyrosyl linkage of their recombining partner (12). Subsequent ligation between dif1 and attP(+) strands requires complementary base pair interactions at the site of phosphodiester bond formation. The integration specificity of CTXΦ is mostly influenced by the compatibility of dif1 and attP(+) sequences (9, 13).

FIG 1.

Scheme of the CTXΦ genome and different attachment sites related to its integration into the genome of V. cholerae. (A) Replicative genome of CTXΦ organized into two distinct modules, RS2 and core. Two XBS present in the RS2 module of CTXΦ are organized in inverse orientations. In attP1, a 12-bp central region separates XerC and XerD binding sites, whereas in attP2, a 7-bp spacer region connects the two enzyme binding sites. (B) In the folded plus-ssDNA phage genome, attP1 and attP2 form intrastrand base-pairing interactions and generate a functional attP(+) site. Both recombinases recognize the folded attP(+) structure and mediate CTXΦ integration. (C) The V. cholerae dif1 site is composed of a 28-bp DNA sequence, in which a 6-bp central region connects 11-bp XerC and XerD binding sites.

In the present study, we took advantage of the widespread presence of chromosomal dimer resolution systems across bacterial phyla to develop a broad-host-range integrative expression vector (10). We constructed an R6K-ori-based integrative expression vector, pBD62, that carries an AraC-encoding gene and an l-arabinose-inducible promoter (PBAD), a multiple-cloning site (MCS), a zeocin resistance gene cassette (sh ble), and CTXΦ-derived XBS. We showed that this vector could efficiently integrate at the dif sites of a wide range of pathogenic and nonpathogenic bacterial cells, like V. cholerae, Vibrio fluvialis, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi, using host-encoded tyrosine recombinases. Stable maintenance of the integrated vector in the absence of antibiotic selection and controlled expression of genes of interest from the vector-originated PBAD promoter were verified using the well-studied reporter genes mCherry, eGFP, and lacZ. Taking the data together, this novel vector would be useful for a number of applications, including gene complementation assays in knockout strains, where it can be stably maintained as a single copy with the capacity for differential gene expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The bacterial strains and the plasmids and phages used for this study are described in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. All strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C with shaking (220 rpm). Unless otherwise indicated, antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: streptomycin (Str), 100 μg/ml; chloramphenicol (Cm), 34 μg/ml for E. coli and 3 μg/ml for V. cholerae, V. fluvialis, V. parahaemolyticus, K. pneumoniae, and S. enterica serovar Typhi; zeocin (Zeo), 25 μg/ml; ampicillin (Amp), 100 μg/ml. For long storage, cells were maintained at −80°C in LB broth containing 20% glycerol. To avoid development of any suppressor mutant, all engineered strains were minimally subcultured, and freshly revived cells were used for all experiments.

TABLE 1.

Relevant bacterial species used in this study

| Species/strain | Genotype/phenotypea | Reference or sourceb |

|---|---|---|

| V. cholerae | ||

| N16961 | WT; O1 El Tor; Stpr | 19 |

| BS1 | N16961 ΔTLC-CTXΦ-dif1::lacZ-dif1 Δdif2; Stpr Spcr | |

| BS2 | N16961 ΔTLC-CTXΦ-dif1 Δdif2; Stpr Spcr Rifr | 9 |

| BS3 | N16961 ΔTLC-CTXΦ-dif1 Δdif2::lacZ-dif2; Stpr Spcr | 9 |

| BS10 | BS1ΔxerC; Stpr Spcr Rifr | 9 |

| BS11 | BS1ΔrecA; Stpr Spcr | 9 |

| BD11 | BS1::pBD63 | This study |

| BD12 | BS1::pBD64 | This study |

| BD13 | BS1::pBD62 | This study |

| BD14 | BS3::pBD65 | This study |

| V. fluvialis | WT | NICED, Kolkata, India |

| V. parahaemolyticus | WT | NICED, Kolkata, India |

| E. coli | ||

| WT | WT | MVIDH, Delhi, India |

| FCV14 | ΔxerC | CNRS-CGM, France |

| K. pneumoniae | WT | MVIDH, Delhi, India |

| S. enterica | WT | MVIDH, Delhi, India |

WT, wild type.

NICED, National Institute of Cholera and Enteric Diseases; MVIDH, Maharshi Valmiki Infectious Disease Hospital; CNRS-CGM, Centre National de la Research Scientifique-Centre de Genetique Moleculaire.

TABLE 2.

Relevant plasmids and phage used in this study

| Name | Genotype/phenotype | Reference or sourcea |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pSW23T | pSW23::oriTRP4 oriVR6K; Camr | 20 |

| pBAD24 | pBR322 ori araC bla; Ampr | 21 |

| pMEV34 | pUC ori lacZec bla; Ampr | 9 |

| pEM7/Zeo | pUC ori bla sh ble; Ampr Zeor | Invitrogen Life Technology, USA |

| pmCherry | Source of mCherry gene | K. Atmakuri laboratory, THSTI |

| pBD60 | pSW23T::xbs CTXΦ; Camr | This study |

| pBEN | Source of eGFP gene | N. Agarwal laboratory, THSTI |

| pBD61 | pBD60 Δcat::sh ble; Zeor | This study |

| pBD62 | pBD61::araC-PBAD; Zeor | This study |

| pBD63 | pBD62::lacZ; Zeor | This study |

| pBD64 | pBD62::mCherry; Zeor | This study |

| pBD65 | pBD62::eGFP; Zeor | This study |

| pBD66 | pBD62 ΔattP*; Zeor | This study |

| pRK1 | pBD60::attP1 mutated; Camr | This study |

| pRK2 | pRK1::attP2 mutated; Camr | This study |

| Phage CTXΦ:Cm | CTXΦ::cat; Camr | This study |

THSTI, Translational Health Science and Technology Institute.

Plasmids.

The XBS was amplified from the replicative genome of CTXΦ using primers P154-P155 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The conditionally replicative pSW23T vector was amplified by using primers P142-P143 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The amplified XBS (290 bp) was digested with XhoI enzyme and cloned into similarly digested and calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIP)-treated P142-P143 amplicons to generate the recombinant vector pBD60 (Table 2). In the next step, the cat gene of pBD60 was replaced by the zeocin resistance sh ble cassette from pEM7 (Table 2). First, the cat gene was deleted from pBD60 by inverse PCR using primers P162-P163, and sh ble was amplified from pEM7 by using primers P156-P157 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The amplified sh ble cassette was digested with EcoRV-NsiI and cloned into an NruI-NsiI-digested P162-P163-amplified vector backbone. The resulting vector was designated pBD61 (Table 2). Then, a 1.3-kb DNA fragment containing the araC gene and the PBAD promoter was digested and removed from pBAD24 by using enzymes EcoRI-ClaI and cloned into similarly digested pBD61 to generate the integrative expression vector pBD62 (Table 2). The vector pBD62 was completely sequenced, and the DNA sequence was deposited in the NCBI database. Three reporter genes, lacZ, mCherry, and eGFP, were cloned into pBD62 to create reporter vectors pBD63, pBD64, and pBD65, respectively (Table 2). The lacZ gene was amplified from pMEV34 using primers P160-P161 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), digested with the PstI-XbaI enzymes, and cloned into similarly digested pBD62. The mCherry gene was amplified from pmCherry (Table 2) using primers P158-P159 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), digested with the EcoRI-XmaI enzymes, and cloned into similarly digested pBD62. Similarly, the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-encoding gene was amplified from the pBEN vector (Table 2) using primers P226-P227 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) and cloned into pBD62 using EcoRI-SacI. The dif2-specific pBD66 was constructed by introducing point mutations in the attP1 and attP2 sites of CTXΦ. We replaced thymidine (T) with cytidine (C), present next to the XerC binding site of attP1, by inverse PCR using primers P125-P126 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Similarly, adenosine (A) of attP2 was replaced by guanosine (G). The introduced point mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Transformation, conjugation, and electroporation.

Bacterial transformations were done by the heat shock method using rubidium chloride-competent E. coli cells. Conjugation between diaminopimelic acid (DAP) auxotroph E. coli β2163 donors and prototroph recipient bacterial cells were done on 0.22-μm sterile filter paper on a Luria agar (LA) plate supplemented with 0.3 mM DAP. Both donor and recipient were grown to early log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], ∼0.3), mixed in a 1/10 ratio, and incubated at 37°C for 12 h. Conjugants were selected based on antibiotic resistance and DAP auxotrophy. Integration of the conjugated plasmid at the dif1 site of V. cholerae was verified by blue-white selection using 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) and IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) in the culture medium. Electroporation of bacterial cells cultured to mid-log phase (OD600, ∼0.5) was done using G buffer (137 mM sucrose, 1 mM HEPES, pH 8.0). Electrocompetent cells (40 μl) were mixed with 500 to 1,000 ng of plasmid DNA in a prechilled microcentrifuge tube and transferred to a 0.1-cm electroporation cuvette, and electroporation was done at 1,400 V for an ∼5-ms pulse.

Microscopy.

Overnight-grown V. cholerae cells were washed with LB broth, diluted at a 1/100 ratio in fresh LB broth, and grown for 3 h at 37°C to late log phase (OD600, 0.5 to 1.0). Expression of mCherry and eGFP in V. cholerae was induced with 0.1% l-Ara. Cells with expressed mCherry and eGFP were washed with M9 minimal medium (Sigma, USA) and resuspended in 1 ml of fresh M9 medium, mixed by gentle tapping, spotted on a thin pad of 1% agarose, and covered with a glass coverslip. Cells were imaged at room temperature. Cell imaging was done at least three times using a Leica TCS SP5 laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica, Germany) with an mCherry- or eGFP-specific filter set to excite and image mCherry and eGFP fluorescence.

Flow cytometry.

The overnight-grown cells were centrifuged at 6,000 rpm for 5 min, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and washed twice. To fix the cells, 100 μl of the suspension was incubated with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) (1:3 ratio) at room temperature for 15 min. The PFA-fixed cells were washed twice with PBS, resuspended in 200 μl PBS, and diluted with flow sheath solution (Becton Dickinson) for flow cytometry analysis. The R1 region, including events corresponding in relative size as indicated by forward scatter (FSC) and in granularity as indicated by side scatter (SSC) of the bacteria, was delineated. The R1 region was gated for further histograms. Flow cytometry histograms were obtained when the cells were grown in the presence of 0.2% glucose or 0.1% l-arabinose. The fluorescence level in filter 3 (FL3) with cells grown in the presence of 0.2% glucose ranged between 0 and 101, and the M1 region was defined. A shift in fluorescence to higher intensities was obtained with cells grown in 0.1% arabinose. The events under M1 represent the proportion (percent) of cells expressing the mCherry gene.

β-Galactosidase assay.

The β-galactosidase assay was performed using a β-galactosidase enzyme activity detection kit (Sigma, USA). Briefly, V. cholerae cells were grown in LB medium supplemented with 0.1% l-arabinose or 0.4% glucose at 37°C under shaking conditions till the OD600 of the culture reached ∼0.6. Samples (0.5 ml) were taken and centrifuged to collect the cell pellet. The cells were washed in Z buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, pH 7.4) and permeabilized with lysis buffer provided in a β-galactosidase enzyme activity detection kit (Sigma, USA). o-Nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) was added to the cell lysate and incubated at 37°C until a yellow color became apparent. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 1 M sodium bicarbonate solution. β-Galactosidase enzyme activity was measured according to the instructions of the β-galactosidase enzyme activity assay kit manufacturer.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The vector pBD62 was sequenced by Sanger sequencing methods using an Applied Biosystems 3130xl genetic analyzer. The complete sequence of pBD62 was submitted to the NCBI database and is available under accession number KJ720574.

RESULTS

Construction and characteristics of integrative expression vector pBD62.

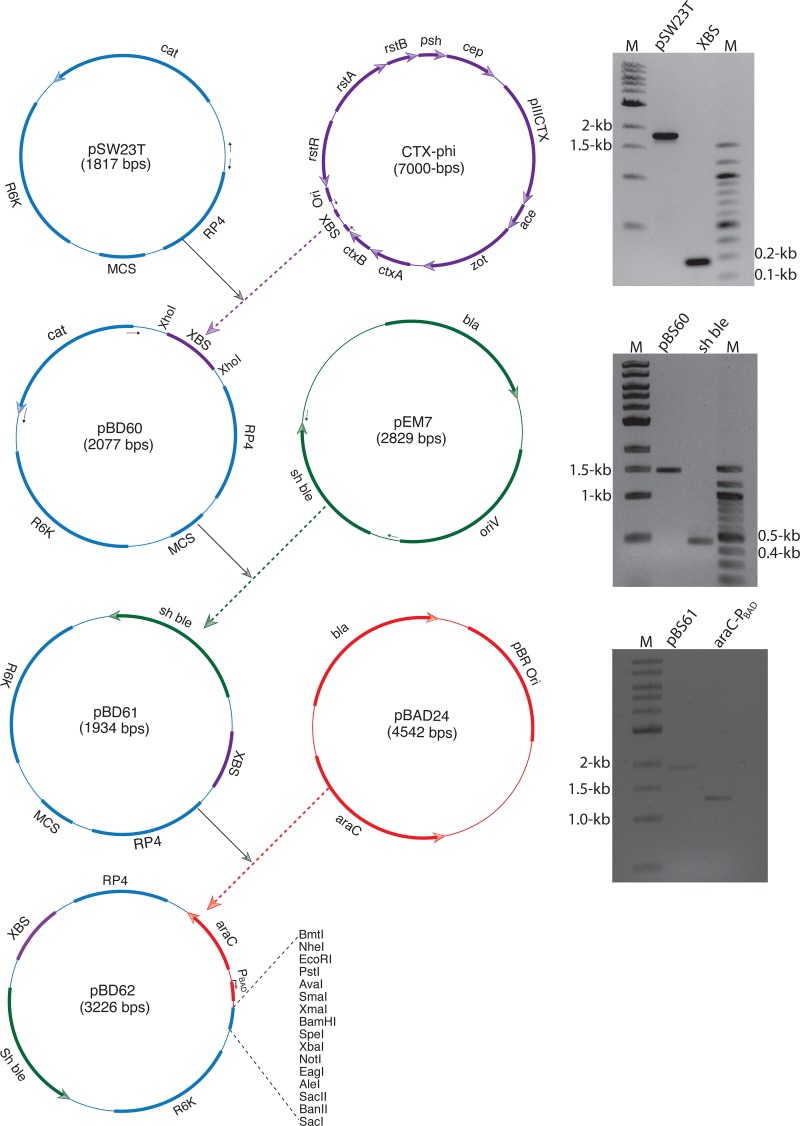

The strategy of pBD62 construction is illustrated in Fig. 2, and construction details are provided in Materials and Methods. Three different plasmids were constructed by PCR amplification, restriction digestion, and subcloning using DNA fragments from the replicative CTXΦ genome and other cloning vectors (Table 2). The DNA fragment carrying two inversely oriented XerCD binding sites was obtained from CTXΦ and cloned between the origin of transfer (RP4 mob) and the cat gene of a small mobilizable suicide plasmid, pSW23T (Fig. 2 and Table 2). The folded single-stranded attP(+) region of pBD62 is the binding site for host-encoded XerCD recombinases. The original chloramphenicol resistance-encoding cat gene of pBD60 was replaced by the sh ble gene, which encodes resistance to the glycopeptide antibiotic zeocin. The araC gene, which encodes the transcriptional regulator AraC, along with its target promoter, PBAD, was obtained from the self-replicating plasmid pBAD24 and cloned into pBD61. Both the regulator and promoter regions were digested and removed from pBAD24 and introduced into pBD61 by restriction digestion, followed by ligation (Fig. 2). The promoter region was placed in front of a suitable MCS containing unique recognition sites for 16 different restriction enzymes to generate the maximum number of options for cloning the gene of interest under the control of the PBAD promoter. The engineered plasmid carries a conditional replication origin, ori R6K, and replicates only in host cells encoding the λ-Pir protein. pBD62 also carries RP4 mob and can be mobilized conjugally if the host genome encodes functional RP4 mob conjugation machinery.

FIG 2.

Strategy used to construct pBD62. The relevant features of pBD62 and its origin from different genetic elements are indicated by the same color codes. Zeocin resistance is encoded by the sh ble gene. R6K and RP4 are essential for pBD62 replication and conjugation, respectively. The arrows indicate the orientation of transcription. Unique restriction enzyme sites present in the MCS region of pBD62 are also depicted. On the right, different gels show the DNA fragments used to construct the vectors. M, molecular size marker.

Integration of pBD62 is dif1 specific and Xer dependent.

Previous studies showed that CTXΦ exploits host-encoded XerCD recombinases to integrate its folded single-stranded genome into the dif sites of V. cholerae chromosomes (8–10). The efficiency of integration is greatly influenced by both phage- and host-encoded functions. The phage replication, which provides single-stranded DNA, and RstB, a phage-encoded single-stranded DNA binding protein, are important but not essential for CTXΦ integration (5, 6, 14). In this study, we sought to explore the possibilities for developing an integrative expression vector using CTXΦ-derived XBS. With this aim, we inserted only an ∼200-bp XBS of CTXΦ into a conditionally replicating plasmid and subsequently developed the expression vector pBD62. We used a colorimetric assay to detect the precise integration of pBD62 into a series of V. cholerae reporter strains harboring functional E. coli lacZ-dif1 or lacZ-dif2 alleles. The lacZ-dif1 allele was constructed by cloning a 28-bp dif1 site in the natural ClaI site of the E. coli lacZ gene. Both synthetic strands of the dif1 site with compatible overhang bases for ClaI site were hybridized, phosphorylated, and inserted in the ClaI-digested and CIP-treated lacZ open reading frame (ORF). Insertion of a dif1 site in the lacZ ORF does not affect the β-galactosidase activity of LacZ. In all the strains, the lacZ-dif1 or lacZ-dif2 allele was used to replace the native dif1 or dif2 site of V. cholerae. The endogenous V. cholerae lacZ gene and dif1 or dif2 site of the other chromosome were also deleted. First, pBD62 was used to transform β2163 donor cells, and then the plasmid was conjugally transferred to V. cholerae strain BS1 carrying a lacZ-dif1 allele (Table 1). The BS1 strain yielded blue colonies on LA plates supplemented with X-Gal, but any integration event at dif1 abolished the lacZ-encoded β-galactosidase function and led to the appearance of white colonies. Conjugation of pBD62 to BS1 gave rise to 0.028% zeocin-resistant colonies, 99.3% of which were white on X-Gal plates, confirming its highly precise integration, like CTXΦ (Table 3). Although negligible, limited nonspecific integration of pBD62 elsewhere in the V. cholerae chromosomes was also detected. No white colonies were obtained when pBD62 was transferred into V. cholerae cells carrying only the lacZ-dif2 allele (Table 3). Since the central-region bases of dif2 and attP(+) immediately adjacent to the XerC binding site are not compatible, no integration event was expected. Integration was not impeded in the absence of RecA function but was completely abolished if XerC function was not provided (Table 3). Altogether, these results provided sufficient evidence that pBD62 uses host-encoded Xer recombinases and integrates specifically into the dif1 site of the cholera pathogen, even in the absence of RstB function.

TABLE 3.

Integration frequencies of pBD62 in dif1 of V. cholerae

| V. cholerae strain | Relevant genotype | Integration frequency (10−7) |

|---|---|---|

| BS1 | lacZ-dif1 | 2,823 ± 578 |

| BS2 | Δdif1 Δdif2 | <1 |

| BS3 | lacZ-dif2 | <1 |

| BS10 | ΔxerC | <1 |

| BS11 | ΔrecA | 1,302 ± 174 |

Design of a dif2-specific integrative vector.

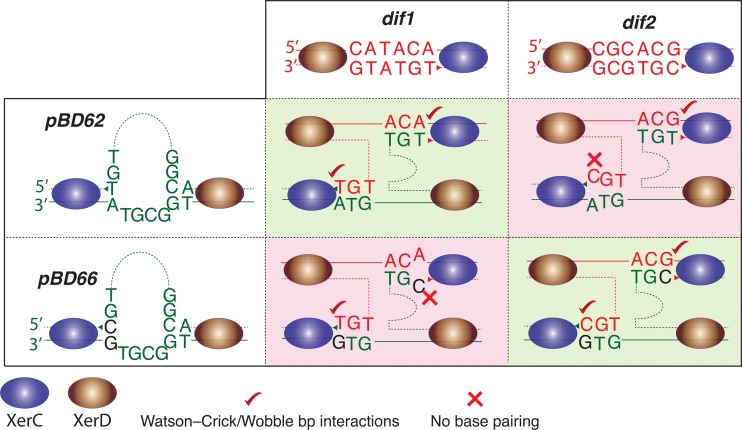

Different CTXΦ variants have different attP sequences, which alone determine chromosome specificity and integration efficiency (9). The integration specificity is directed by the ability to form hydrogen bonds between bases of the recombining strands at the site of phosphodiester bond formation, which stabilizes the exchanged strands during recombination (Fig. 3). In the present study, we engineered a dif2-specific XBS by introducing specific point mutations in the central region of attP(+) (Fig. 3). The first T base in the central region of attP1 on the XerC binding side was replaced by C, which eliminated any possible hydrogen bond formation with the corresponding A base in the central region of dif1 (Fig. 3). However, the introduced C base established a perfect Watson-Crick base pair interaction with the corresponding G base in the central region of dif2 on the XerC binding side (Fig. 3). To stabilize the attP(+) structure, the A base in the central region of attP2 on the XerD binding side was also replaced by G (Fig. 3). These two base substitutions in the XBS prompted pBD66 to integrate specifically at dif2. When we delivered the dif2-specific pBD66 into V. cholerae BS3 cells carrying lacZ-dif2, specific integration was observed (Table 4). In contrast, no white colonies were observed in V. cholerae cells deficient in dif2 or Xer recombinases (Table 4). Taking the data together, pBD66 vectors carrying dif2-compatible attachment sites are suitable tools to deliver genes of interest in the terminus region of chromosome 2 of V. cholerae.

FIG 3.

Scheme showing compatibility between phage and bacterial attachment sites. Compatible attachment sites are indicated by a green background. Base pairing between recombining strands at the site of phosphodiester bond formation is necessary for successful integration. T→C and A→G point mutations were introduced into the central regions of attP1 and attP2 of CTXΦ, respectively, to generate dif2-specific attP(+). The introduced mutations in attP(+) create proper Watson-Crick base-pairing interactions between dif2 and modified attP(+) and make the integration feasible. The triangles indicate the positions of XerC cleavage.

TABLE 4.

dif2-specific integration of pBD66

| V. cholerae strain | Relevant genotype | Integration frequency (10−7) |

|---|---|---|

| BS3 | Δdif1 lacZ-dif2 | 80 |

| BS1 | Δdif2 lacZ-dif1 | <1 |

pBD62 is stable and is an ideal tool for differential regulation of gene expression.

We checked the stability of the integrated pBD62 in V. cholerae by growing the host cells continuously in rich medium without adding any selection pressure. As a control, we used one self-replicating plasmid, pEM7 (Table 2), encoding zeocin resistance. Stability was measured by the presence of the resistance-encoding gene in the host cells. We observed that in the case of V. cholerae cells carrying pBD62, the total numbers of CFU in the presence or absence of zeocin were very similar, even after 40 h of continuous growth (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). This was not the case for V. cholerae cells carrying the self-replicating plasmid pEM7. A major population of cells lost their plasmids in the absence of antibiotic selection (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

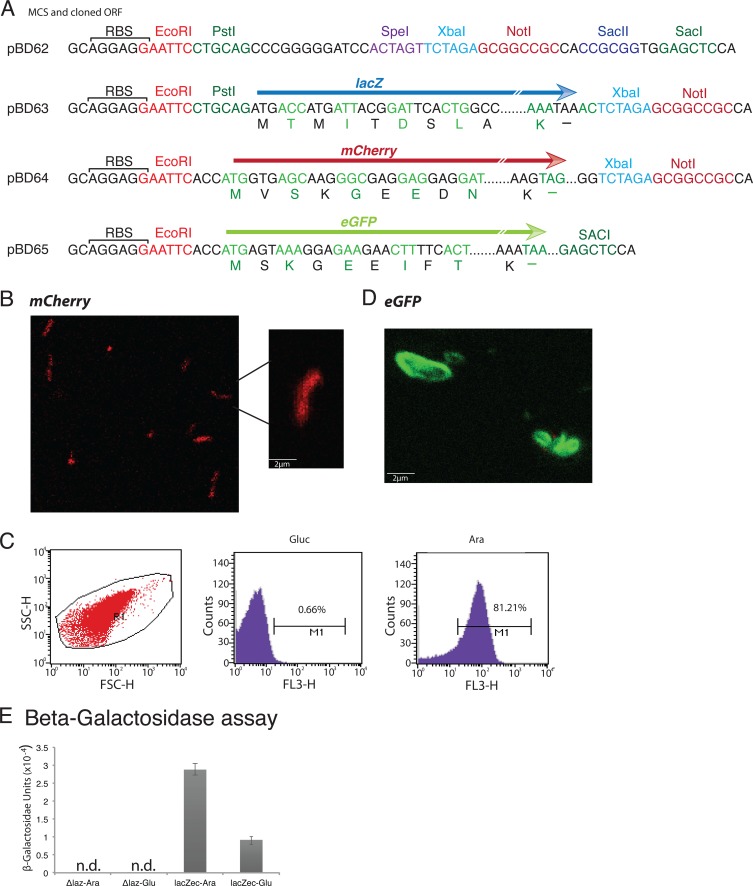

To estimate the expression levels of cloned genes under the araC-PBAD system of pBD62 in induced or repressed states, we used two well-studied reporter genes, mCherry and lacZ. Both genes were cloned under the PBAD promoter of pBD62 (Fig. 4) and introduced into the chromosomes of endogenous-lacZ-negative V. cholerae strains (Table 1). First, we confirmed mCherry expression in V. cholerae by confocal microscopy (Fig. 4). We then measured the number of bacterial cells expressing the mCherry gene and the fluorescence intensity of mCherry in the presence of either l-Ara or d-Glu using flow cytometry. We observed that in the presence of l-Ara, more than 88.8% of the cells produced fluorescent signal, whereas the mCherry signal was almost abolished (<1%) when the host cells were cultivated in a medium supplemented with d-Glu (Fig. 4). We extended our study to check the expression of another well-studied fluorescence gene, eGFP, and observed a suitable level of expression in V. cholerae (Fig. 4). Next, we quantitated the β-galactosidase activity of V. cholerae cells harboring pBD63 (Table 2), a pBD62 derivative carrying E. coli lacZ. V. cholerae cells carrying pBD63 were grown similarly to mCherry-harboring cells. Expression of the lacZ gene was modulated by supplementing the growth medium with l-Ara or d-Glu, and β-galactosidase activity was measured after 3 h of incubation at 37°C. We observed an ∼4-fold increase of β-galactosidase activity in the presence of l-Ara compared to d-Glu (Fig. 4), ensuring differential regulation of expression of the cloned gene from the integrated vector.

FIG 4.

pBD62 derivatives with multiple reporter genes and their functional validation in V. cholerae. (A) MCS region of pBD62 with or without a reporter gene. Unique restriction enzyme sites and ribosomal binding sites (RBS) are marked for all four plasmids. Arrows of different colors indicate different reporter genes. (B) Expression of mCherry from integrated pBD64 in V. cholerae was detected by laser confocal microscopy. Freshly grown cells were washed with M9 minimal medium and used for microscopy. (C) Expression of mCherry at the population level was measured in the presence of glucose (Gluc) or arabinose (Ara) using flow cytometry. (D) Expression of eGFP from integrated pBD65 in V. cholerae was detected by laser confocal microscopy. (E) β-Galactosidase activity of E. coli lacZ (lacZec), cloned into pBD63, was measured in endogenous-lacZ-negative V. cholerae cells. Experiments were done at least three times, and average values with standard deviations (error bars) are reported. n.d., not done.

A wide range of bacterial species support pBD62 integration.

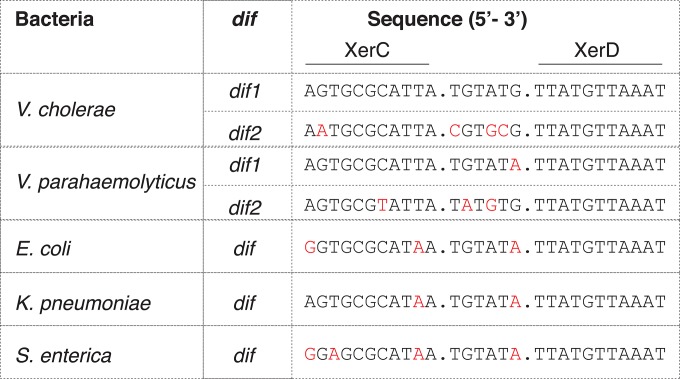

The Xer recombination system, encompassing two tyrosine recombinases (XerC-XerD), one DNA motor protein (FtsK), and a 28-nucleotide (nt) dif sequence, is highly conserved in bacteria (10). CTXΦ and several other related filamentous phages carrying dif-like attachment sites could exploit the bacterial Xer recombination system for lysogenic conversion (12). In this study, we sought to explore whether the attP(+) structure of CTXΦ could be recognized by the diverse Xer machinery present in different bacteria and, if recognized, the possibility of using CTXΦ XBS to develop a broad-host-range integrative vector. For this purpose, we selected six different well-studied pathogenic and nonpathogenic bacterial cell types to monitor the integration efficiency of pBD62. First, we verified attP-dif compatibility using available dif sequences of the selected cells (Fig. 5). We observed that all the selected bacteria have dif sequences compatible with attP(+) of CTXΦ (Fig. 5). Next, we introduced the expression vector pBD62 into all six selected bacterial cells by conjugation. We observed that, pBD62 could integrate into the chromosomes of all the selected wild-type bacterial cells with different efficiencies (Table 5). As for BS10, no integration event was detected in XerC-negative E. coli cells (Table 5). Although CTXΦ is native to V. cholerae, to our surprise, the highest integration efficiency was observed in V. fluvialis. We observed similar integration efficiencies in V. cholerae, V. parahaemolyticus, E. coli, and K. pneumoniae (Table 5). The integration frequency in S. enterica was very low (Table 5). Several factors, such as dif-attP(+) compatibility, efficiency of XerCD binding to folded attP(+), and the stability of the introduced ssDNA plasmid in host cells, could influence the pBD62 integration efficiency. Altogether, we confirmed that the integrative expression vector pBD62 is suitable for genetic manipulation in different bacteria carrying dif sites compatible with attP(+) of CTXΦ.

FIG 5.

Sequence alignment of dif sites of different enteric bacteria used in this study. The dif site is composed of a 28-bp DNA sequence in which a 6-bp central region connects 11-bp XerC and XerD binding sites. The sequence of V. cholerae dif1 was used as a reference, and any alteration compared to the reference sequence is labeled in red.

TABLE 5.

Integration frequencies of pBD62 in dif sites of bacterial chromosomes

| Bacterium | Integration frequency (10−6) | Total no. of Zeor colonies counted |

|---|---|---|

| V. cholerae | 2,830 ± 1,225 | 8,490 |

| V. fluvialis | 14,567 ± 1,803 | 43,700 |

| V. parahaemolyticus | 2,510 ± 361 | 7,530 |

| E. coli | 2,350 ± 1,129 | 7,050 |

| K. pneumoniae | 2,693 ± 780 | 8,080 |

| S. enterica | 1,130 ± 131 | 3,390 |

| E. coli ΔxerC | <1 |

DISCUSSION

We developed two novel integrative expression vectors using the araC-PBAD expression system and XBS of CTXΦ. The most attractive features of the pBD62 and pBD66 vectors for genetic studies are as follows: (i) the complemented gene has a single copy in the host cell, and the integrated vector is highly stable without adding any selection pressure; (ii) once integrated, there is no need to add selection pressure to keep the vector stable; (iii) the single copy helps in the differential expression of the gene of interest; (iv) no chromosomal gene is interrupted due to integration, and the host physiology is not changed; (v) there is no need for a homologous-recombination system for integration; and (vi) bacterial cells carrying multiple chromosomes have an opportunity to deliver genes into specific chromosomes using pBD62 or its dif2-specific derivatives.

Copy number.

In general, the copy number of an autonomously replicating plasmid does not remain constant in different phases of bacterial growth (2, 15). This may lead to varying transcript levels of the studied gene replicating with the plasmid backbone. The expression vector pBD62 is not able to replicate in host cells if the host is devoid of λ-Pir function. In the absence of the λ-Pir protein, pBD62 integrates irreversibly at the dif site of the host chromosome. The copy number of the integrated vector, and hence the gene present in the vector, always remains constant. Thus, the vector pBD62 would be suitable for complementation studies and for depletion phenotypes of essential, as well as toxin-encoding, genes.

Stable maintenance.

An extrachromosomal genetic element always imposes a cost to cells for its replication, maintenance, and segregation during cell division, which can affect chromosomal-DNA replication (16). During in vitro studies, to avoid plasmid loss, it is necessary to keep cells under selection pressure. The presence of antibiotics in the growth medium often induces altered cell phenotypes and causes accumulation of spontaneous mutations (17). The integration strategy of CTXΦ is unique. The phage uses the host recombination machinery and its folded single-stranded genome for integration. We manipulated only the ∼200-bp XBS of CTXΦ into pBD62 to exploit its integration strategy and developed the integrative vector for V. cholerae. Although most of the tyrosine recombinase-mediated reaction is reversible, the integration strategy adopted by CTXΦ is exceptional. In this unique strategy, upon integration, the folded single-stranded XBS is converted to double-stranded DNA and eliminates functional XBS, making the reaction irreversible, which makes possible the stable maintenance and inheritance of the integrated plasmid, along with the host chromosome. Since the Xer system and XBS sites are highly conserved in bacteria, we anticipated that the vector pBD62 would also be able to integrate into the dif sites of other bacteria. To validate our hypothesis, we introduced the vector into six different bacteria carrying single or multiple chromosomes. We observed that all the selected bacteria support pBD62 integration with different efficiencies (Table 5). The integration efficiency depends on several factors, including the host genotype (Tables 3 and 5). The highest and lowest levels of integration events were observed in V. fluvialis and S. Typhi, respectively. These different efficiencies of integration might be due to different efficiencies of the Xer recombinases of the respective bacteria or linked to the stability of the single-stranded DNA substrate. Further studies are warranted to explore the mechanistic basis of integration efficiency.

Specific integration and differential gene expression.

Bacteria with multiple chromosomes carry different dif sequences (10). Although the XBS are highly conserved, the overlap regions of the dif sites, where strand exchange occurs during chromosome dimer resolution or lysogenic conversion of bacteriophages, often carry different nucleotide sequences. The integration specificities of phages in the dif sites are mostly influenced by the compatibility of dif and attP sequences (9). For successful events of integration, strand stabilization at the site of phosphodiester bond formation is extremely important. The integrative vector pBD62 carries an attachment site suitable for dif1 of vibrios and dif of other bacteria, while pBD66 is compatible with dif2 of V. cholerae (Fig. 3). With both systems, the events of integration were always single and thus delivered a single copy of a gene into the chromosome.

Leaky expression of genes from autonomously replicating complemented vectors is a common problem (18). Tight repression of a cloned gene from a vector-originated promoter and endogenous transcription machinery has seldom succeeded when self-replicating vectors were used. This problem could be partially overcome with the integrative plasmid. pBD62 with an mCherry (pBD64) or lacZ (pBD63) gene reliably established that differential modulation is achievable in the presence of a repressor or inducer using a vector-originated PBAD promoter and a host-encoded RNA polymerase, which was not the case when we used the same gene and the same regulatory system in self-replicating plasmids. We observed that when we introduced pBD64 carrying an mCherry gene into V. cholerae, a fluorescence signal was hardly detectable in the presence of d-Glu. In contrast, in the presence of l-Ara, large numbers of cells that expressed elevated levels of mCherry were detected. This experimental evidence indicates that differential regulation is achievable under the PBAD promoter from a defined chromosomal location.

Integration requires attP(+) and is recA independent.

Since pBD62 integration relies on site-specific recombination and the same system is highly conserved in other bacteria, the vector would be useful to deliver genetic elements into bacterial chromosomes in the absence of a homologous-recombination system. The efficiency of XerCD-mediated site-specific recombination is very high compared to homologous recombination (9). Recombinants could be obtained easily after overnight incubation. Several studies conducted to explore the role of RecA in DNA repair and the SOS response have used autonomously replicating vectors to provide RecA trans functions. Using pBD62, gene transportation into a specific locus of a chromosome in the absence of RecA function is now feasible. Since the integration reaction is RecA independent and relies on the XerCD-mediated recombination between the double-stranded dif sequence and the folded attP(+) of the plus-ssDNA CTXΦ genome, it is important to introduce the ssDNA form of nonreplicative plasmids into host cells for any successful event of integration to occur.

Conclusion.

For expedient genetic analysis, it is extremely important to use a simple, small, broad-host-range, low-copy-number, and stable expression vector to mimic the native chromosomal copy number of the studied gene under optimal physiological conditions. The vector we developed using traits from different plasmids and a filamentous phage meets all these criteria and would be very useful for communities working on bacterial genomics and exploring the functions of novel genes. The conjugative expression vectors developed in this study allow irreversible integration of any fragment of DNA into a specific locus of a chromosome (dif) using widely distributed endogenous bacterial recombinases without interrupting chromosomal coding sequences.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank F. X. Barre and Christophe Possoz, CNRS-CGM, France, for the generous gift of plasmids, enthusiastic support, and critical reading of the manuscript. We sincerely acknowledge N. C. Sharma, MVIDH, Delhi, India; T. Ramamurthy, NICED, Kolkata, India; and Gaurav Barta, Krishnamohan Atmakuri, and Nisheeth Agarwal, THSTI, Gurgaon, India, for providing us with bacterial cells and DNA molecules. We thank J. Paul, JNU, Delhi, India, for assistance in fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis. We thank Naveen Kumar, Satyabrata Bag, Preety Rana, D. Anbumani, and Mayanka Dayal for their excellent technical assistance.

The work was supported by a research grant from the Department of Science and Technology (grant no. SB/FT/LS-309/2012), Government of India (GOI), and the Department of Biotechnology (grant no. BT/MB/THSTI/HMC-SFC/2011), GOI.

B.D. designed the research; B.D., R.K., A.P., S.S.G., S.S., and O.M. performed experiments; G.B.N. contributed reagents/analytical tools; B.D., R.K., and G.B.N. analyzed data; B.D. wrote the paper.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 15 September 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.01966-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Canchaya C, Proux C, Fournous G, Bruttin A, Brussow H. 2003. Prophage genomics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67:238–276. 10.1128/MMBR.67.2.238-276.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan SA. 2005. Plasmid rolling-circle replication: highlights of two decades of research. Plasmid 53:126–136. 10.1016/j.plasmid.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Das B, Pal RR, Bag S, Bhadra RK. 2009. Stringent response in Vibrio cholerae: genetic analysis of spoT gene function and identification of a novel (p)ppGpp synthetase gene. Mol. Microbiol. 72:380–398. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das B, Bischerour J, Barre FX. 2011. VGJphi integration and excision mechanisms contribute to the genetic diversity of Vibrio cholerae epidemic strains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:2516–2521. 10.1073/pnas.1017061108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waldor MK, Mekalanos JJ. 1996. Lysogenic conversion by a filamentous phage encoding cholera toxin. Science 272:1910–1914. 10.1126/science.272.5270.1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waldor MK, Rubin EJ, Pearson GD, Kimsey H, Mekalanos JJ. 1997. Regulation, replication, and integration functions of the Vibrio cholerae CTXphi are encoded by region RS2. Mol. Microbiol. 24:917–926. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3911758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huber KE, Waldor MK. 2002. Filamentous phage integration requires the host recombinases XerC and XerD. Nature 417:656–659. 10.1038/nature00782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Val ME, Bouvier M, Campos J, Sherratt D, Cornet F, Mazel D, Barre FX. 2005. The single-stranded genome of phage CTX is the form used for integration into the genome of Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Cell 19:559–566. 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Das B, Bischerour J, Val ME, Barre FX. 2010. Molecular keys of the tropism of integration of the cholera toxin phage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:4377–4382. 10.1073/pnas.0910212107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carnoy C, Roten CA. 2009. The dif/Xer recombination systems in proteobacteria. PLoS One 4:e6531. 10.1371/journal.pone.0006531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leslie NR, Sherratt DJ. 1995. Site-specific recombination in the replication terminus region of Escherichia coli: functional replacement of dif. EMBO J. 14:1561–1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Das B, Martinez E, Midonet C, Barre FX. 2013. Integrative mobile elements exploiting Xer recombination. Trends Microbiol. 21:23–30. 10.1016/j.tim.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Das B, Bischerour J, Barre FX. 2011. Molecular mechanism of acquisition of the cholera toxin genes. Indian J. Med. Res. 133:195–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falero A, Caballero A, Ferran B, Izquierdo Y, Fando R, Campos J. 2009. DNA binding proteins of the filamentous phages CTXphi and VGJphi of Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 191:5873–5876. 10.1128/JB.01206-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friehs K. 2004. Plasmid copy number and plasmid stability. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 86:47–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bailey JE. 1993. Host-vector interactions in Escherichia coli. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 48:29–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez JL, Baquero F. 2000. Mutation frequencies and antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1771–1777. 10.1128/AAC.44.7.1771-1777.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah S, Das B, Bhadra RK. 2008. Functional analysis of the essential GTP-binding-protein-coding gene cgtA of Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 190:4764–4771. 10.1128/JB.02021-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heidelberg JF, Eisen JA, Nelson WC, Clayton RA, Gwinn ML, Dodson RJ, Haft DH, Hickey EK, Peterson JD, Umayam L, Gill SR, Nelson KE, Read TD, Tettelin H, Richardson D, Ermolaeva MD, Vamathevan J, Bass S, Qin H, Dragoi I, Sellers P, McDonald L, Utterback T, Fleishmann RD, Nierman WC, White O, Salzberg SL, Smith HO, Colwell RR, Mekalanos JJ, Venter JC, Fraser CM. 2000. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 406:477–483. 10.1038/35020000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demarre G, Guerout AM, Matsumoto-Mashimo C, Rowe-Magnus DA, Marliere P, Mazel D. 2005. A new family of mobilizable suicide plasmids based on broad host range R388 plasmid (IncW) and RP4 plasmid (IncPalpha) conjugative machineries and their cognate Escherichia coli host strains. Res. Microbiol. 156:245–255. 10.1016/j.resmic.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guzman LM, Belin D, Carson MJ, Beckwith J. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:4121–4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.