ABSTRACT

Broadly neutralizing antibodies targeting the HIV-1 envelope (Env) are key components for protection against HIV-1. However, many cross-reactive epitopes are often occluded. This study investigates the mechanisms contributing to the masking of V2i (variable loop V2 integrin) epitopes compared to the accessibility of V3 epitopes. V2i are conformation-dependent epitopes encompassing the integrin α4β7-binding motif on the V1V2 loop of HIV-1 Env gp120. The V2i monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) display extensive cross-reactivity with gp120 monomers from many subtypes but neutralize only few viruses, indicating V2i's cryptic nature. First, we asked whether CD4-induced Env conformational changes affect V2i epitopes similarly to V3. CD4 treatment of BaL and JRFL pseudoviruses increased their neutralization sensitivity to V3 MAbs but not to the V2i MAbs. Second, the contribution of N-glycans in masking V2i versus V3 epitopes was evaluated by testing the neutralization of pseudoviruses produced in the presence of a glycosidase inhibitor, kifunensine. Viruses grown in kifunensine were more sensitive to neutralization by V3 but not V2i MAbs. Finally, we evaluated the time-dependent dynamics of the V2i and V3 epitopes. Extending the time of virus-MAb interaction to 18 h before adding target cells increased virus neutralization by some V2i MAbs and all V3 MAbs tested. Consistent with this, V2i MAb binding to Env on the surface of transfected cells also increased in a time-dependent manner. Hence, V2i and V3 epitopes are highly dynamic, but distinct factors modulate the antibody accessibility of these epitopes. The study reveals the importance of the structural dynamics of V2i and V3 epitopes in determining HIV-1 neutralization by antibodies targeting these sites.

IMPORTANCE Conserved neutralizing epitopes are present in the V1V2 and V3 regions of HIV-1 Env, but these epitopes are often occluded from Abs. This study reveals that distinct mechanisms contribute to the masking of V3 epitopes and V2i epitopes in the V1V2 domain. Importantly, V3 MAbs and some V2i MAbs display greater neutralization against relatively resistant HIV-1 isolates when the MAbs interact with the virus for a prolonged period of time. Given their highly immunogenic nature, V3 and V2i epitopes are valuable targets that would augment the efficacy of HIV vaccines.

INTRODUCTION

The need for a safe and effective human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) vaccine is paramount, but despite intensive research, the scientific challenges facing its development remain formidable. The modest level of protection observed in the RV144 phase III vaccine trial indicated that protective immunity against HIV-1 can be elicited through vaccination (1). High levels of antibodies (Abs) specific for the variable loop 1 and 2 (V1V2) domain of HIV Env gp120 in the vaccinees correlated with reduced risk of HIV-1 acquisition (2–4). Follow-up sieve analyses of breakthrough viruses showed increased vaccine efficacy against viruses with genetic signatures at two positions in V2, further supporting the role of V2 in HIV-1 immunity (5). However, the exact mechanism(s) that contributed to a reduced risk of HIV-1 in RV144 vaccinees remains unknown, highlighting the importance of better understanding the antiviral functions of Abs against the V1V2 domain of HIV-1 gp120.

Monoclonal Abs (MAbs) targeting three different categories of epitopes in the V1V2 domain have been described. CH58 and CH59, isolated from an RV144 vaccinee, bind V2 peptides and monomeric gp120 proteins; their epitopes (designated V2p, for V2 peptide) are mapped to helical and loop structures modeled from the C strand of V1V2 (6–8). MAbs, such as CAP256, CH01, PG9, and PG16, recognize quaternary epitopes (V2q) in the V1V2 domain, which are preferentially expressed on the native trimeric Env spike and comprised in part of N-glycans (9–11). Finally, a set of seven MAbs used in our study recognize a third type of epitopes designated V2i (for V2 integrin). The V2i epitope depends on the proper conformation of the V1V2 domain and maps to the disordered V2 loop that connects the C and D strands, in particular, the area overlapping with the integrin α4β7-binding site, hence “V2i” (6, 12, 13). The structure of this region is unknown, as it was not resolved in the cryoelectron microscopy and crystal structures of Env trimers and in the 1FD6-V1V2 scaffolded structures (14–16). Notably, all seven V2i MAbs display extensive cross-reactivity in binding monomeric gp120 proteins from tier 1, 2, and 3 viruses from different HIV-1 subtypes. However, V2i MAbs neutralize only a few tier 1 viruses and none of the tier 2 or tier 3 viruses in the standard neutralization assay with TZM.bl target cells (17). These data indicate that the V2i epitope is occluded from Ab recognition in resistant tier 2 and tier 3 viruses, reminiscent of cross-reactive neutralizing epitopes in the crown of variable loop 3 (V3). V3 epitopes are occluded in many viruses and pseudoviruses by the V1V2 domain (18) and the N-glycans shrouding the HIV-1 Env spike (19–21), and their exposure is augmented by CD4 binding to Env (22, 23) and when the virus is enriched for high-mannose-type N-glycans (24, 25). Nonetheless, factors regulating the accessibility of V2i epitopes have not been described.

The present study was performed to elucidate whether similar mechanisms mask V2i and V3 epitopes. We evaluated the effects of CD4 binding, N-glycan composition, and kinetics of pseudovirus-MAb interaction on the neutralization of tier 1 and tier 2 viruses by V2i MAbs compared to V3 MAbs. The data demonstrate that distinct factors affect HIV-1 neutralization by V2i and V3 MAbs. Unlike V3 MAbs, neutralization by V2i MAbs was not affected by CD4 binding or Env enrichment with high-mannose glycans. However, like V3 MAb-mediated neutralization, neutralization by V2i MAbs was improved by increasing the virus-Ab preincubation time. Together with recent structural data showing the positions of V3 and V2i epitopes on the HIV-1 Env trimer, this study indicates that the exposure of V3 and V2i is regulated differently but both epitopes are subject to conformational masking, as they become more Ab accessible by prolonged Ab-virus interaction. Although the conformational heterogeneity of V2 and V3 needs to be further investigated, these findings provide insight into the importance of the structural dynamics that govern the neutralizing activity of Abs against these sites and may be exploited in designing vaccines against HIV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines, plasmids, and viruses.

The TZM.bl cell line was obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (ARRRP), as contributed by J. Kappes and X. Wu (26). 293T/17 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Plasmids expressing Env of BaL.01 JRFL, REJO, and YU2 for generating pseudoviruses were obtained from the NIH ARRRP. Simian-human immunodeficiency viruses (SHIV) C.1157ipEL-p and HIV-1 92TH023 were also obtained from NIH ARRRP. CM244-OR Env was kindly provided by Sodsai Tovanabutra (MHRP and Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine). BaL.ec1 pseudovirus was kindly provided by Victoria Polonis (Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine). BaL.ec1 was tested in CD4-dependent and time-dependent neutralization assays, whereas BaL.01 was used for kifunensine experiments. Plasmids pMX-gp160ΔcBaL-IRES-GFP and pMX-gp160ΔcJRFL-IRES-GFP (coexpressing gp160 with a deleted cytoplasmic tail and green fluorescent protein [GFP] separated by an internal ribosome entry site [IRES]) (27, 28) for cell binding assays were kindly provided by the Nussenzweig laboratory (The Rockefeller University).

Pseudoviruses were produced by cotransfecting 293T/17 cells with HIV-1 rev- and env-expressing plasmids and the pNL4–3Δenv plasmid using jetPEI transfection reagent (Polyplus-transfect SA). Glycan-modified pseudoviruses were generated as described above in the presence of 25 μM kifunensine (Sigma). Supernatants were harvested after 48 h and clarified by centrifugation and 0.45-μm filtration. Some virus stocks were concentrated with a 100-kDa Amicon filter (Millipore). Single-use aliquots were stored at −80°C. Virus titration was performed on TZM.bl cells as described previously (29).

Human monoclonal antibodies.

The V2i, V3, and control MAbs used in this study were produced in our laboratory as described previously (13, 17, 30–34). MAbs b12 (provided by Dennis Burton and Carlos Barbas), 2G12 (provided by Hermann Katinger), and NIH45-46 (provided by Pamela Bjorkman) were obtained through the NIH ARRRP (35–37). V2q MAb PG9 was purchased from Polymun Scientific. V2p MAbs CH58 and CH59 were provided by Barton Haynes (Duke Human Vaccine Institute).

Neutralization assay.

Virus neutralization was measured using a β-galactosidase-based assay (Promega) with TZM.bl target cells (38). Serial dilutions of MAbs were added to the virus in half-area 96-well plates (Costar) and incubated for designated time periods at 37°C. TZM.bl cells were then added along with DEAE-dextran (6.25 μg/ml; Sigma) and incubated for 48 h. Each condition was tested in duplicate or triplicate. Assay controls included replicate wells of TZM.bl cells alone (cell control) and TZM.bl cells with virus alone (virus control). Percent neutralization was determined on the basis of virus control under the specific assay condition. The virus input corresponded to titrated stocks yielding 150,000 to 200,000 relative luminescence units. For neutralization assays with soluble CD4 (sCD4), the virus was preincubated with recombinant human sCD4 (Progenics Pharmaceuticals) for 30 min at 37°C, before the addition of serially diluted MAbs. For temperature-dependent study, the virus-MAb mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37°C or 38.5°C prior to adding the TZM.bl cells. For experiments with different pHs, the pH of the medium was adjusted by the addition of HCl.

gp120 binding assay.

The relative binding affinities of MAbs to gp120 from BaL and JRFL pseudoviruses was measured by a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The ELISA plates were coated with sheep anti-gp120 Ab (D7324, 2 μg/ml; Aalto BioReagents, Dublin, Ireland), blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and incubated with 1% Triton X-100-treated pseudoviruses. Serially diluted MAbs (0.01 to 10 μg/ml) were then added for 2 h, and the bound MAbs were detected with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG Fc and p-nitrophenyl phosphate substrate.

Cell binding assay.

As described previously (27), 293T/17 cells were grown to 70% confluence and transfected with pMX-gp160ΔcBaL-IRES-GFP or pMX-gp160ΔcJRFL-IRES-GFP (28), using FuGene HD (Roche). Two days later, the cells were washed with PBS, detached with trypsin-free cell-dissociation buffer (Invitrogen), and resuspended in PBS containing 2% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM EDTA. The transfected cells were stained on ice for the designated time periods with MAb (10 μg/ml), washed, and stained for 30 min with allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated mouse anti-human IgG (BD Pharmingen). The cells were analyzed using a BD LSRFortessa.

Statistical analysis.

Comparisons of virus neutralization and MAb binding were performed using S-Plus 6.1 (Insightful Corp.) or GraphPad Prism. Statistical analyses were performed on neutralization data that reached ≥50%.

RESULTS

To investigate the mechanisms by which V2i and V3 epitopes are occluded from Ab recognition, we tested whether virus neutralization by V2i and V3 MAbs was influenced by the following three parameters: CD4 binding, N-glycan composition, and time. We compared the neutralization by seven V2i MAbs (697, 830A, 1357, 1361, 1393, 2158, and 2297) and three V3 MAbs (447, 2219, and 2557) against tier 1 and tier 2 viruses from different clades of HIV-1. MAb 1418, specific for human parvovirus B19, was included as a negative control. MAbs CH58 (V2p) CH59 (V2p), PG9 (V2q), 2G12, b12 (CD4-binding site [CD4bs]), and NIH45-46 (CD4bs) were also tested in some experiments for comparison.

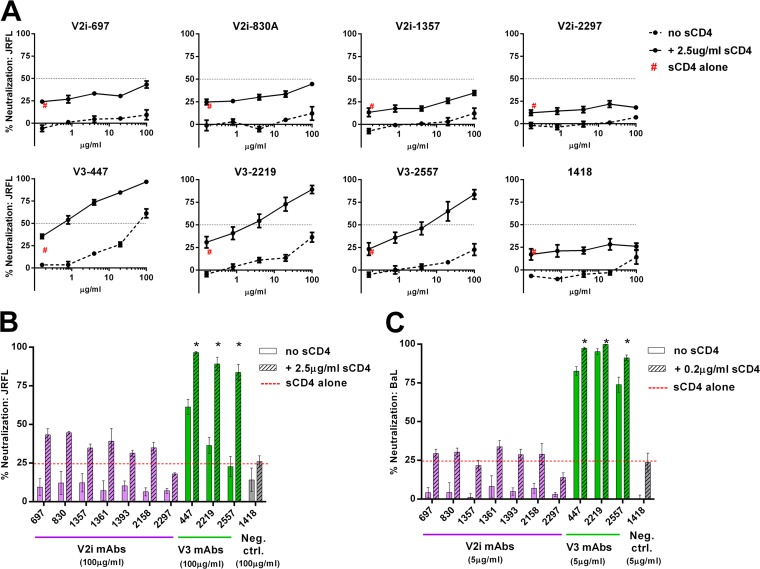

CD4 engagement enhances HIV-1 neutralization by V3 but not V2i MAbs.

CD4 binding induces conformational changes in HIV-1 Env that result in the exposure of otherwise inaccessible regions, including cryptic Ab epitopes in the V3 loop (39–42). However, the influence of CD4 on V2i epitopes has not been investigated. To address this gap in the field, we tested the capacity of V2i versus V3 MAbs to neutralize HIV-1 JRFL and BaL pseudoviruses that were pretreated with sCD4 or left untreated. No neutralization was detected with each of the seven V2i MAbs when titrated against both untreated JRFL and untreated BaL (Fig. 1). Upon pretreatment of these pseudoviruses with sCD4 at a fixed concentration that caused ∼25% inhibition, neutralization by all V2i MAbs remained below 50%, and no dose-dependent effect was observed. Similar patterns were seen with JRFL and BaL (Fig. 1B and C). In contrast, sCD4 treatment significantly increased JRFL neutralization by the V3 MAbs 447, 2219, and 2557 (P < 0.001). At the highest concentration tested (100 μg/ml), 84 to 97% neutralization was reached by the V3 MAbs against JRFL in the presence of sCD4, while only 23 to 61% was achieved without sCD4 (Fig. 1A and B). As expected, the increase in neutralization against BaL, a tier 1 virus with relatively accessible V3 epitopes, was less pronounced, albeit still significant (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1C). The control MAb 1418 did not show any neutralization in the presence or absence of sCD4 against either JRFL or BaL. These results indicate that, unlike that of V3, the accessibility of V2i epitopes is not modulated by CD4 interaction with HIV-1 Env.

FIG 1.

Influence of CD4 engagement on virus neutralization by V2i and V3 MAbs. (A) Neutralization of JRFL pseudovirus by V2i, V3, and control MAbs was tested following treatment with or without sCD4. Virus was pretreated with sCD4 at one designated concentration for 30 min at 37°C or left untreated and then incubated with serially diluted MAb for 1 h at 37°C. The mixture was added to TZM.bl target cells, and after 48 h, virus infection was measured based on β-galactosidase activity. (B, C) Comparison of neutralization by V2i, V3, and control MAbs in the presence or absence of sCD4 against JRFL and BaL.ec1. “sCD4 alone” denotes virus neutralization by sCD4 alone (no MAbs). Means and standard errors from two independent experiments (each in duplicate) are shown. Statistical analyses were performed on neutralization curves reaching ≥50%. *, P < 0.001 for JRFL (B) and P < 0.05 for BaL (C), based on the two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test showing significant synergistic difference above the calculated sum of percent neutralization by titrated MAb plus sCD4.

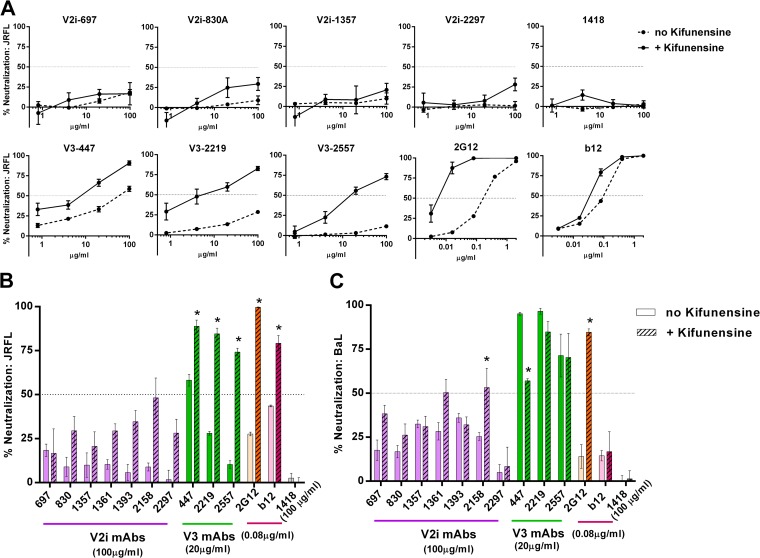

Changes in N-glycan sugar composition affect neutralization by V3 MAbs but not V2i MAbs.

The removal of N-glycans from specific sites on HIV-1 Env enhances virus sensitivity to Abs against V3 and other neutralizing epitopes on gp120 (23, 43). Recent studies further demonstrate the influence of specific sugar moieties of N-glycans on access to neutralizing V3 epitopes (24, 25). In particular, enrichment of high-mannose-type glycans enhanced virus neutralization by V3 Abs. To investigate whether V2i epitopes are similarly affected, we generated JRFL and BaL pseudoviruses in the presence of 25 μM kifunensine, a mannosidase inhibitor that blocks the processing of complex-type N-glycans and enriches for the high-mannose type. The V2i MAbs displayed poor neutralizing activities against JRFL and BaL irrespective of kifunensine treatment (Fig. 2A to C). This contrasted with the increased neutralization observed with all three V3 MAbs tested against JRFL produced in kifunensine-treated cells compared to their neutralization of untreated JRFL (Fig. 2A and B). MAbs 2G12 and b12 were also tested in parallel as controls. Consistent with previous reports (44), MAb 2G12, which recognizes a cluster of N-glycans bearing the high-mannose type (37), showed greater levels of neutralization against JRFL produced in the presence of kifunensine than against untreated JRFL. The irrelevant control MAb 1418 had no neutralizing activity against treated or untreated viruses. In the case of BaL, kifunensine treatment rendered the virus more resistant to neutralization by the V3 MAb 447 (Fig. 2C), whereas no pronounced effects were observed on neutralization by 2219, 2557, and b12. However, kifunensine treatment significantly increased BaL neutralization by the V2i MAb 2158 (P < 0.001), reaching up to 50% neutralization at the highest concentration tested (100 μg/ml). As anticipated, BaL neutralization by 2G12 was also greatly enhanced. These results demonstrate that V3 epitopes for MAbs 447, 2219, and 2557 are positively (in the case of JRFL) or negatively (in the case of BaL.01) modulated by the changes in N-glycan sugar composition, while V2i epitopes are not affected, except for 2158 against BaL. The results highlight the important role played by N-glycans in influencing V3 and V2i epitopes, beyond simple steric masking. Moreover, the differences observed between JRFL and BaL indicate that the impact of the N-glycan composition is dependent on the virus strain.

FIG 2.

Changes in N-glycan sugar composition affect virus neutralization by V3 MAbs but not V2i MAbs. (A) V2i, V3, and control MAbs were titrated and tested for neutralizing activity against JRFL produced in the presence or absence of kifunensine. Virus and MAb were incubated for 1 h and then added to TZM.bl target cells. Virus infectivity was measured 48 h later based on β-galactosidase activity. (B, C) Comparison of neutralization by V2i, V3, and control MAbs against JRFL or BaL.01 produced with or without kifunensine. Means and standard errors calculated from three different experiments (each in duplicate) are shown. *, P < 0.0001 for JRFL and BaL.01, based on the two-way ANOVA test comparing the neutralization curves of each MAb tested against virus produced with or without kifunensine.

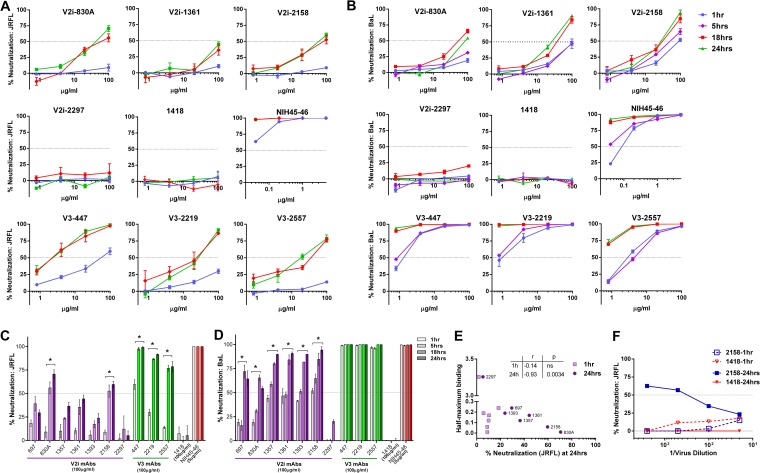

Prolonging the virus-MAb preincubation time increases neutralization and binding by V2i and V3 MAbs.

We next investigated the effects of the length of virus-MAb interaction before their exposure to TZM.bl target cells on the neutralizing activity of V2i versus V3 MAbs. Increasing the preincubation time significantly improved the neutralizing activity of several V2i MAbs against both JRFL and BaL (Fig. 3). By prolonging the incubation time from the standard 1 h to 18 h or 24 h, ≥50% neutralization was reached with V2i MAbs 830A and 2158 against JRFL (Fig. 3A and C). The V2i MAb 1361 also showed increased neutralization, reaching nearly 50%. Neutralization by the other V2i MAbs also increased but did not attain 50% (Fig. 3C). Only V2i MAb 2297 had no time-dependent neutralizing activity, similar to the control MAb 1418; this V2i MAb had an exceptionally low binding affinity for JRFL (Fig. 3E). Indeed, the levels of JRFL neutralization achieved with the longer incubation time of 24 h but not the standard 1-h incubation correlated with the relative affinities of the V2i MAbs as measured by half-maximal binding to JRFL gp120 (Fig. 3E). When tested against BaL, V2i MAbs displayed various low levels of neutralization after 1 h of virus-MAb incubation (Fig. 3B and D). With prolonged incubation time, neutralization increased significantly for all V2i MAbs except 2297. Interestingly, increased neutralization was observed after extending the incubation to 18 h but not to 5 h. With the incubation time of ≥18 h, V3 MAbs (447, 2219, and 2557) and the CD4bs MAb NIH45-46 also displayed greater neutralization against both JRFL and BaL, beyond the levels observed with the standard 1-h incubation time.

FIG 3.

Time-dependent increase of virus neutralization by V2i and V3 MAbs. (A, B) Virus neutralization was measured after JRFL or BaL.ec1 was incubated with serially diluted MAbs for the designated period of time at 37°C prior to the addition of TZM-bl target cells. The CD4bs MAb NIH45-46 and the irrelevant control MAb 1418 were tested in parallel for comparison. (C, D) Comparison of neutralization by V2i, V3, CD4bs, and control MAbs against JRFL and BaL.ec1 after various times of virus-MAb preincubation. Means and standard errors from two to three experiments are shown. *, P < 0.05 for V2i and P < 0.001 for V3 MAbs, from the two-way ANOVA test comparing neutralization curves observed with virus-MAb preincubation of 1 h versus 18 h and 1 h versus 24 h. (E) JRFL neutralization achieved after a 24-h preincubation with V2i MAbs correlated with gp120 JRFL binding as measured by ELISA. Correlation was also observed with an 18-h incubation (P = 0.033; r = −0.75) but not with a 1-h incubation (not shown). (F) JRFL neutralization after a 24-h incubation with V2i MAb displayed virus dose dependency, while no neutralization was achieved with a 1-h incubation regardless of the amount of input virus. Virus was titrated, treated with one fixed concentration of V2 MAb 2158 or control MAb 1418 (100 μg/ml) for 1 h or 24 h, and then added to the TZM.bl target cells. Virus infection was assessed 48 h later based on β-galactosidase activity. At high virus dilutions yielding exceedingly low infectivity, some neutralization values reached below 0% and are denoted in the graph as 0%.

To test whether differences in input virus infectivity account for the increased neutralization observed after 18 to 24 h versus 1 h of virus-MAb incubation, serially diluted JRFL was tested for neutralization by a constant amount (100 μg/ml) of V2i MAb 2158 or control MAb 1418 following 1 h versus 24 h of virus-MAb incubation time. Untreated diluted virus was tested in parallel. No neutralization was observed with a 1-h incubation over the range of virus input tested (Fig. 3F). In contrast, the 2158-mediated neutralization observed after a 24-h incubation showed a reciprocal relationship with the amount of virus input. These data indicate that the virus neutralization attained with a 24-h incubation time is dependent on both the MAb concentration and the virus dose, whereas the standard 1-h incubation time was not sufficient regardless of the virus dose and MAb concentration.

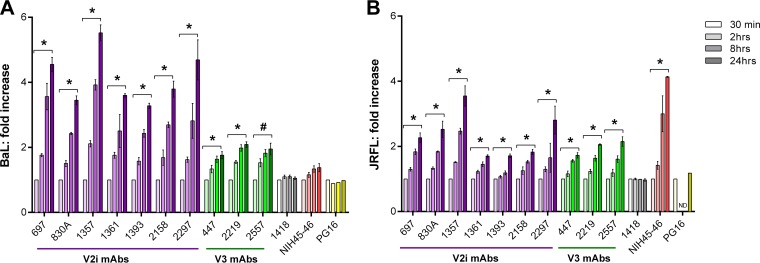

One likely reason for the need for longer virus-MAb preincubation to neutralize HIV-1 is that the V1V2 and V3 regions are highly dynamic on Env spikes, continually flickering from one conformation to another and rarely adopting the structures recognized by the MAbs. To evaluate this idea, we asked whether the binding of V2i and V3 MAbs to Env spikes also occurred in a time-dependent manner. Therefore, 293T/17 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing BaL or JRFL Env (27, 28) for 48 h and then incubated with V2i, V3, PG16, or control MAbs for various periods of time. The binding of MAbs to the virus Env on the cell surface was measured by flow cytometry (Fig. 4). Little binding to BaL Env was observed for the V2i MAbs after 30 min, but a significant linear increase was detected over time (Fig. 4A). After 24 h, the binding of all seven V2i MAbs increased 4-fold on average when measured by mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) (average MFI of 1,190 for the seven MAbs at 30 min versus MFI of 4,914 at 24 h). Higher levels of V3 than of V2i MAbs bound the BaL Env after only 30 min (average MFI, 6,369), and V3 MAb binding increased ∼1.9-fold after 24 h (Fig. 4A). The CD4bs MAb NIH45-46 showed no time-dependent increase of binding to BaL Env, indicating that this highly potent neutralizing MAb attained maximal binding within 30 min (MFI of 1,512 at 30 min and MFI of 1,894 at 24 h) (Fig. 4A). The increase in V2i MAb binding to JRFL Env was less pronounced. Low levels of binding were observed after 30 min (mean MFI of 612), and after 24 h, a 2.25-fold increase was detected (mean MFI of 1,467) (Fig. 4B). V3 MAbs similarly showed an average 2-fold increase over 24 h. As with BaL-transfected cells, V3 MAbs bound JRFL-transfected cells at higher levels (mean MFI of 2,240 at 30 min and mean MFI of 4,428 at 24 h). The CD4bs MAb NIH45-46 displayed a time-dependent 4-fold increase in binding to JRFL Env (Fig. 4B). As a control to verify the relative expression of trimeric Env spikes on the transfected cells over time, we also tested PG16 MAb, which recognizes a quaternary epitope on the Env trimer. The data show comparable binding of PG16 to BaL and JRFL after incubation for 30 min and up to 24 h, indicating that similar levels of properly folded trimeric spikes were expressed on the transfected cells throughout the assay period.

FIG 4.

Time-dependent increase of Env spike binding by V2i and V3 MAbs. Relative levels of MAb binding to BaL (A) or JRFL (B) Env spikes on transfected 293T cells were measured by flow cytometry. Cells were transfected with gp160ΔcBaL-IRES-GFP for 48 h and treated with V2i, V3, or control MAbs at 4°C for various times from 30 min to 24 h. MAb binding was detected with APC-conjugated anti-human IgG. Fold increase of MAb binding was calculated relative to mean fluorescence intensity measured at 30 min (normalized to 1). Means and standard errors from two to four independent experiments are shown. *, P < 0.05 based on the one-tail t test comparing fold increase at 24 h versus 30 min; #, P = 0.059; ND, 2 h and 8 h time points not tested for JRFL.

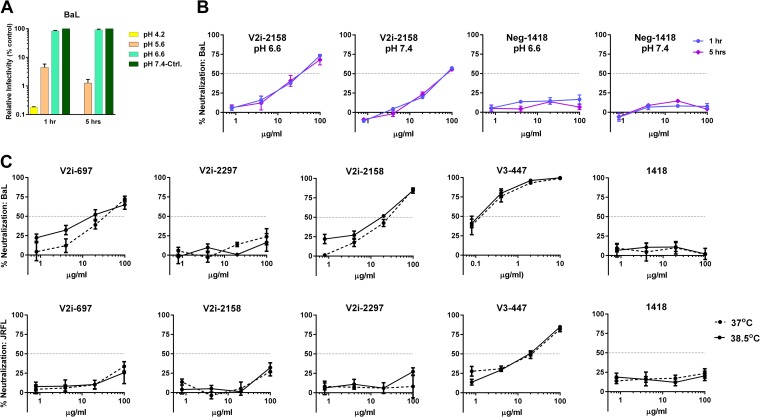

Two additional assay parameters were studied, pH and temperature. To study the effects of different pHs on virus neutralization, we first evaluated the infectivity of BaL upon incubation in medium of pH 4.2, 5.6, 6.6, or 7.4. The virus infectivity decreased to <10% at pH 4.2 and 5.6 but remained unchanged at pH 6.6 compared to the infectivity at pH 7.4 (Fig. 5A), allowing us to compare virus neutralization under the two latter conditions. BaL neutralization by V2i MAb 2158 and control MAb 1418 was assessed at pH 6.6 or pH 7.4 following 1 h or 5 h of virus-MAb incubation. Lowering the pH to 6.6 had no significant effect on virus neutralization after 1 h or 5 h of incubation with the MAb (Fig. 5B). Similarly, when the temperature during virus-MAb incubation was raised from 37°C to 38.5°C, the neutralizing activities of V2i or V3 MAbs against BaL and JRFL were comparable (Fig. 5C). Hence, lowering the pH to 6.6 and increasing the temperature to 38.5°C did not augment virus neutralization by V2i and V3 MAbs as was observed with prolonging the virus-MAb incubation time to ≥18 h.

FIG 5.

Effect of pH and temperature on virus neutralization by V2i and V3 MAbs. (A) To measure the effect of pH on virus infectivity, BaL.ec1 pseudovirus was incubated for 1 h in medium adjusted to pH 4.2, 5.6, 6.6, or 7.4 prior to the addition of TZM.bl target cells. Virus infectivity was measured 48 h later based on β-galactosidase activity. (B) To compare BaL.ec1 neutralization by V2i MAb 2158 and control MAb 1418 at pH 6.6 versus pH 7.4, virus-MAb mixtures were incubated at the designated pH for 1 h or 5 h before adding the target cells. Means and standard errors from representative experiments (each in duplicate) are shown. (C) To evaluate the effect of higher temperature on virus neutralization, 5-fold serial dilutions of V2i and V3 MAbs were incubated with JRFL and BaL.ec1 at 37°C versus 38.5°C for 1 h before the addition of TZM-bl target cells. The irrelevant control MAb 1418 was used as a negative control. The cells were then cultured at 37°C for 48 h and infection measured based on β-galactosidase activity. Means and standard errors of two experiments are shown.

Prolonging virus-MAb incubation enhances neutralization of other HIV-1 isolates by V2i, V2p, V2q, and V3 MAbs.

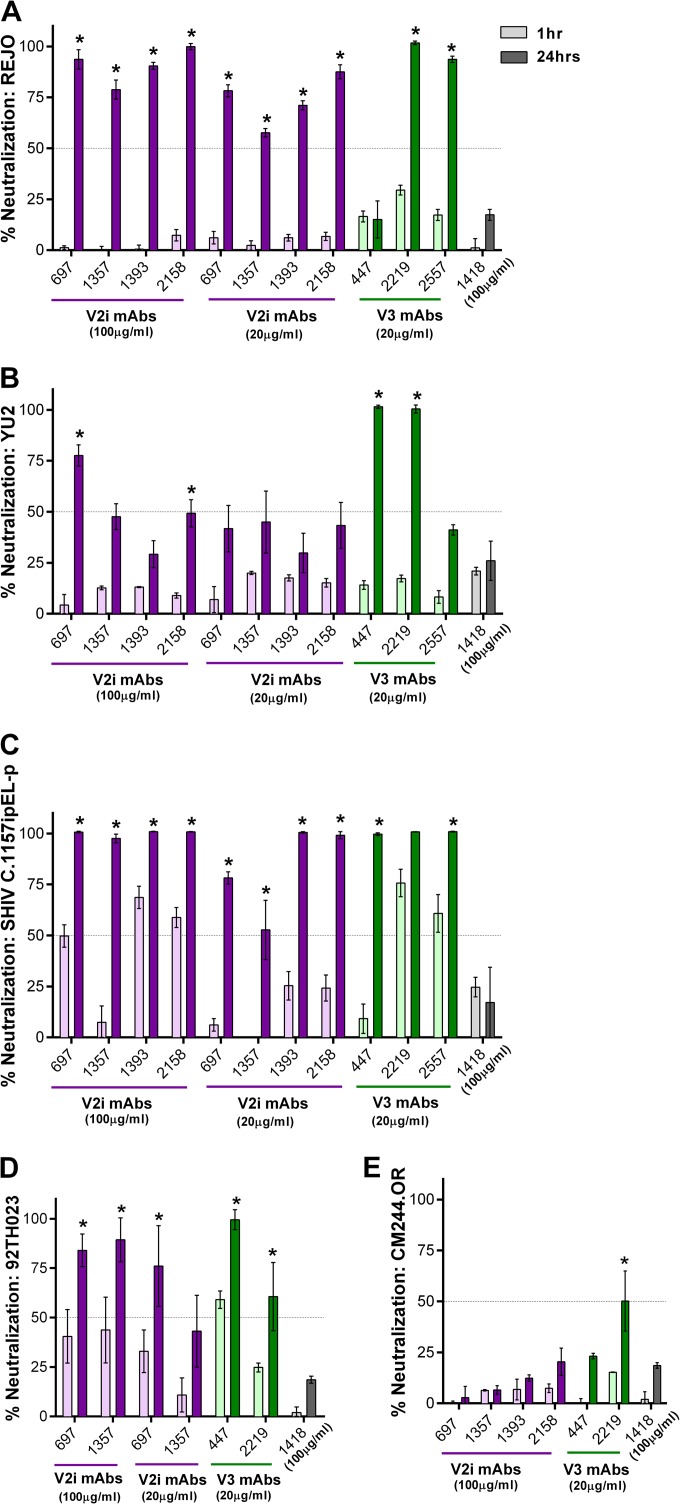

In addition to JRFL and BaL, we evaluated the neutralization of viruses from different clades, including REJO (clade B), YU2 (clade B), SHIV C.1157ipEL-p (clade C), 92TH023 (CRF_01AE), and CM244-OR (CRF_01AE). With the standard 1-h incubation, no neutralization was detected against REJO and YU2 by the V2i and V3 MAbs tested (Fig. 6A and B). However, greater than 90% neutralization was achieved when REJO was incubated for 24 h with 100 μg/ml of V2i MAbs 697, 1393, and 2158, while 79% neutralization was reached with 1357 (Fig. 6A). Neutralization above 50% was also observed with these V2i MAbs at 20 μg/ml upon 24 h of virus-MAb incubation. Increased levels of neutralization after incubation for 24 h compared to the neutralization after 1 h were similarly obtained with V3 MAbs 2219 and 2557 but not with V3 MAb 447 and control MAb 1418. In the case of YU2, neutralization reached 77% after 24 h of incubation with 100 μg/ml of V2i MAb 697 but dropped to 41% with 20 μg/ml (Fig. 6B). The other V2i MAbs also showed increased neutralization, but the levels only reached ≤50%. Similarly, V3 MAbs 447 and 2219 but not 2557 exhibited greater neutralization, reaching 100% following 24 h of incubation. Increased neutralization was also observed with 24 h versus 1 h of incubation when V2i and V3 MAbs were tested against SHIV C.1157ipEL-p (Fig. 6C) and HIV-1 92TH03 (Fig. 6D). In contrast, CM244.OR remained poorly neutralized (Fig. 6E), indicating that not all viruses become sensitive to neutralization by V2i and V3 MAbs after the extended virus-MAb incubation time. No neutralization was detected with the control MAb 1418 against any of the viruses tested.

FIG 6.

Time-dependent increase of neutralization against different viruses by V2i and V3 MAbs. Virus neutralization was measured after REJO (A), YU2 (B), SHIV C.1157ipEL-p (C), HIV-1 92TH023 (D), and CM244.OR (E) viruses were incubated with serially diluted MAbs for 1 h versus 24 h at 37°C prior to the addition of TZM-bl target cells. Means and standard errors from two to three experiments are shown. Statistical analyses were done on neutralization data reaching ≥50%. *, P < 0.001 for REJO, YU2, and SHIV and P < 0.05 for CM244.OR and HIV-1 92TH023.

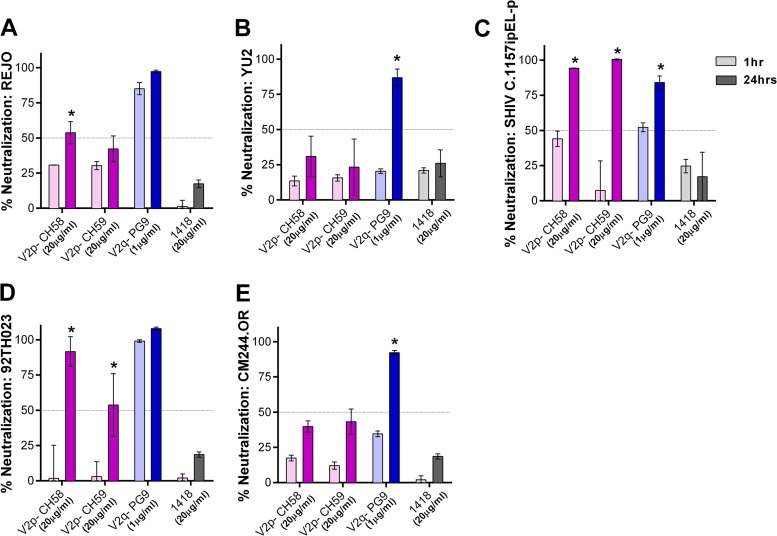

To evaluate whether prolonging virus-MAb incubation had similar effects on MAbs targeting other epitopes in the V1V2 domain, V2p and V2q, we tested MAbs CH58 (V2p), CH59 (V2p), and PG9 (V2q) against the same five viruses as were used in the experiment whose results are shown in Fig. 6. Increased neutralization was seen with V2p MAbs, albeit only against SHIV C.1157ipEL-p and HIV-1 92TH023 (Fig. 7); the two viruses are known to be sensitive to CH58 and CH59 (7). In contrast, PG9 showed potent neutralizing activity against all viruses after 24 h of virus-MAb incubation, and the neutralization of YU2, SHIV C.1157ipEL-p, and CM244.OR was significantly enhanced with the longer incubation compared to the neutralization after the standard 1 h (Fig. 7).

FIG 7.

Virus neutralization by V2p and V2q MAbs after prolonged virus-MAb incubation. Virus neutralization by V2p (CH58 and CH59) and V2q (PG9) MAbs was measured after 1 h versus 24 h of virus-MAb preincubation. REJO (A), YU2 (B), SHIV C.1157ipEL-p (C), 92TH023 (D), and CM244.OR (E) were incubated with MAbs for the designated period of time at 37°C prior to the addition of TZM-bl target cells. Means and standard errors from two to three experiments are shown. Statistical analyses were done as described in the legend to Fig. 6. *, P < 0.001 for REJO, YU2, SHIV (except P < 0.05 for PG9), HIV-1 92TH023, and CM244.OR.

Taken together, these data demonstrate that, unlike the epitopes targeted by the highly potent MAbs, such as NIH45-46, neutralizing V2 and V3 epitopes on the Env of many HIV-1 isolates are not readily recognized by Abs at any one time but become accessible gradually over a period of time. Thus, a prolonged virus-MAb incubation time is needed to detect neutralization by MAbs against these epitopes. This study also shows that different factors contribute to the occlusion of V2 and V3 epitopes from Ab recognition. Of the five parameters examined here, three influence V3 epitopes, but only the time of MAb-virus preincubation modulates V2 epitopes.

DISCUSSION

The modest level of protection reported in the RV144 clinical trial has invigorated the HIV-1 research field and brought renewed attention to the V1V2 and V3 regions of HIV-1 Env gp120. However, it remains unknown whether and how Abs target these loops to reduce infection by HIV. Although many MAbs against V1V2 and V3 cross-react with monomeric Env of HIV-1 isolates from different subtypes, they generally display weak neutralization against tier 2 and tier 3 viruses (13, 17, 45, 46), indicating poor accessibility of the V1V2 and V3 epitopes on the Env spikes. The present study evaluates whether the same mechanisms underlie V2i and V3 epitope occlusion from and exposure to MAbs that target these epitopes. Interestingly, CD4-induced Env conformational changes, which affect V3, had no effect on V2i epitopes. This finding may be informed by the V2i position revealed in the recently published trimeric HIV-1 Env structures (14, 15, 47, 48). The V1V2 domain is localized at the apex of the trimer above and distant from the CD4-binding site (14, 49, 50), and the V2i epitopes in particular encompass the disordered, surface-exposed region of V2 that contains the α4β7-binding motif (6, 12). The V3 loop, on the other hand, is beneath V1V2, with its epitope-bearing crown pointing toward the inner trimer axis, away from the trimer surface (15), albeit this is only a single structure of an envelope from a single strain, constrained by crystal packing and bound Ab. V1V2 deletion and CD4 treatment augment V3 epitope exposure, thereby promoting virus capture and neutralization by V3 MAbs (22, 51, 52). Indeed, CD4 binding induces the crown of V3 to flip up or protrude from the surface of the Env trimer, as seen in the monomeric gp120 core (53), but is not likely to modify the accessibility of V2i epitopes as seen in this study.

We also investigated the contribution of N-glycans in masking the V2i versus V3 epitopes. N-glycans play an important role in viral escape by shielding the key vulnerable epitopes on the Env spike (23), including V3 epitopes. For example, the removal of N-glycans at positions 187 and 197 in the V2 loop and at position 301 on the V3 base improved the antigenicity and immunogenicity of V3, CD4bs, and membrane proximal external region (MPER) epitopes (19, 54–56). Enriching the N-glycans on HIV Env with the high-mannose type by growing viruses in kifunensine or in a cell line lacking N-acetylglucosamine transferase I also increased virus sensitivity to V3 MAbs (24, 25). Conversely, for the relatively sensitive tier 1 virus BaL, kifunensine reduced neutralization by V3 MAb 447, suggesting the potential role of glycans in governing V3 exposure on the more open Env trimers of the tier 1 viruses. In contrast, kifunensine treatment had no positive or negative effects on neutralization with the seven V2i MAbs tested, indicating that the N-glycan composition regulating V3 epitopes is not a factor underpinning poor Ab recognition of V2i epitopes. All N-glycans observed in the crystal structures of scaffolded V1V2 point away from the V2i (6, 16, 57). Hence, although N-glycans influence the Ab recognition of V2i epitopes (13), they function mainly to induce and maintain proper folding of the V1V2 domain. N-glycans are not part of the V2i epitope, in contrast to the V2q epitopes recognized by PG9 and PG16, and do not participate in shielding V2i epitopes from neutralizing Abs.

Finally, we evaluated the time-dependent dynamics of the V2i and V3 epitopes to determine whether these epitopes continuously sample different conformations, only rarely adopting those recognizable by the Abs at any one time. If this idea is correct, the epitope occupancy by the Abs would increase over time, leading to greater virus binding and neutralization with prolonged virus-Ab incubation time. The inability to resolve the V2 loop structure where the major element of V2i epitopes is located points to the highly flexible and dynamic nature of this region on the HIV Env trimer. In the case of V3 epitopes, multiple conformations have been observed in the crystal structures of V3 peptides bound by each of the various V3 MAbs studied (58, 59), which yet differ from those seen on monomeric gp120 and trimeric gp140 proteins. The data from the present study agree with this idea, since virus neutralization by most V3 and V2i MAbs increased significantly with ≥18 h of virus-MAb preincubation. A previous study by Binley et al. (60) also showed that prolonging the incubation time from 1 h to 18 h improved virus neutralization by MAbs against V3, MPER, and the CD4-binding site. Here, we report for the first time time-dependent neutralization by MAbs targeting different epitopes in the V1V2 domain, including V2i, V2p, and V2q. Notably, the enhanced neutralization attained following the prolonged incubation time with these V2 MAbs was observed against specific virus isolates. For example, V2p MAbs which are not broadly reactive were effective only against tier 1 viruses SHIV C.1157ipEL-p and HIV-1 92TH023, while V2i MAbs were more cross-reactive and displayed potent neutralization against tier 1 viruses BaL, SHIV C.1157ipEL-p, and 92TH023 and tier 2 viruses JRFL and REJO, but only two V2i MAbs neutralized YU2 (tier 2) and none neutralized CM244.OR (tier 2). The specificity of virus neutralization detected under the prolonged virus-MAb incubation was also evident from the lack of virus neutralization by V2i MAbs that do not recognize the virus envelope (17; also data not shown) and by the irrelevant control MAb 1418.

Among the different parameters evaluated in this study, only virus-MAb incubation time was found to influence the neutralizing activities of V2i MAbs. The neutralization levels achieved by the different V2i MAbs following 24 h of incubation correlated with the MAb binding affinities, while the neutralization levels with the standard 1-h incubation did not. In contrast, increasing the temperature during virus-MAb incubation from 37°C to 38.5°C had no effect on the neutralizing activity of V2i or V3 MAbs. A previous study has shown, however, that higher temperatures increase the fluidity of membranes and facilitate HIV-1 entry via the fusion pores, thereby promoting HIV-1 infectivity (61). We also studied the effect of lower pHs on virus infectivity and neutralization by V2i MAbs. Virus infectivity decreased to <10% at pH 4.2 and 5.6 but remained unchanged at pH 6.6 compared to the infectivity at pH 7.4. In agreement with these data, past studies demonstrate that the acidic pH of <5.0 in the vaginal mucosa is detrimental to the virus but that semen neutralizes the environment, promoting virus transmission (62–64). At pH 6.6 and pH 7.4, the levels of virus neutralization by V2i MAb 2158 were comparable whether the virus was incubated with the MAb for 1 h or 5 h. Hence, unlike incubation time, pH and temperature in the limited ranges tested have minimal effects on virus neutralization by V2i MAbs.

The virus neutralization observed after 18 h or 24 h of incubation cannot be explained simply by lower virus input due to virus decay over time. With 1 h of incubation, the V2i MAb did not mediate any neutralization even when smaller amounts of input virus were used. Indeed, no neutralization was observed over the entire range of virus dilutions examined. On the other hand, with a 24-h incubation, the neutralization levels correlated inversely with the virus input. The longer time needed for V2i MAbs to neutralize HIV-1 suggests their relatively low occupancy rate, or on rate, for binding to the Env spike. This is supported by our data showing that the levels of V2i MAb binding to Env on the cell surface after the initial 30 min were low relative to those seen with potently neutralizing MAbs, such as NIH45-46. However, V2i MAb binding continued to increase over time, and as more epitopes are occupied, the virus neutralization threshold is reached after 18 h. Based on Haim's model of virus- and Ab-specific factors determining HIV-1 neutralization (65), the V2i MAbs fall into the Ab class with a high perturbation factor, which requires high degrees of conformational changes in the Env or epitope region for Ab recognition. This is consistent with the flexible nature of the V2i region (14–16, 49) and with the idea that the V2i conformation recognized by the Ab is displayed only for a brief period of time and by a fraction of the Env. Altogether, these data support the notion that V2i exposure is not influenced by N-glycans or CD4 binding; rather, the V2i epitopes situated on the surface-accessible region of the trimeric Env spike are subjected to conformational masking. Similar to V2i, the structural dynamics of V2p and V2q epitopes also influence the neutralization activity of MAbs targeting these epitopes, and the effects vary depending on the virus strains.

The significance of neutralization mediated by V2i Abs following an 18-h or longer incubation with the virus is yet unknown. Moreover, relatively high concentrations (20 to 100 μg/ml) are needed to achieve ≥50% neutralization. However, high levels of Abs to the variable loops are attainable in chronically HIV-infected patients (66), although it remains unknown whether these levels can be reached by immunization, particularly locally at the site of virus entry. Perhaps a cocktail of MAbs or polyclonal Abs consisting of V2i Abs and/or other specificities may reach sufficiently high concentrations to mediate neutralization and act in a synergistic or additive manner (67–69). Since virus neutralization after prolonged incubation with V2i MAbs is inversely correlated with the amount of virus input, these Abs are likely to have an impact on the low-dose virus transmission that occurs via sexual transmission and not the high-dose infection among intravenous drug users. Indeed, HIV-1-specific antibodies with modest virus-neutralizing activity have shown protection against SHIV transmission in low-dose challenge studies (70). The half-life of plasma virions was reported to be between 6 h and 1.2 days (71, 72). With 18 h required for V2i Abs to exert significant binding and neutralization, these Abs could reduce the virus infectivity and the size of the infectious inoculum in vivo. Nonetheless, virus entry to target cells is much faster than 18 h, as the entire sequence of CD4 binding, chemokine receptor engagement, and virus fusion occurs in ∼60 min (73). Cell-to-cell transmission of HIV can be completed even more rapidly, within 30 min or less, in the tight cell-cell junction microenvironment of the virological synapse (74–76). Whether V2i Abs requiring the prolonged virus-Ab interaction would be able to exert any inhibitory effects against virus acquisition in vivo requires further investigation.

The steps in the virus life cycle that can be affected by V2i Abs also need to be better understood. In this study, the TZM.bl assay was used to measure virus neutralization. The target cells used in this standard assay express CD4 and CCR5 but not α4β7, which has been implicated in facilitating virus attachment to gut-mucosal CD4 target cells, in part by interacting with V2 (77). If V2i Abs are present and interact with transmitted virus at the mucosal port of virus entry, they may reduce infection of CD4 T cells by blocking virus attachment via α4β7. Nonetheless, a more recent study demonstrates that α4β7 binding may not be a general property of the Envs of most HIV-1 variants (78).

Notably, this study provides novel evidence that neutralization of relatively resistant HIV-1 isolates, such as JRFL, REJO, and YU2, may be mediated by V3 and V2i MAbs, which previously were deemed to be nonneutralizing against these and other tier 2 viruses (17). Considering that induction of V3 and V2i Abs by immunization is achievable with vaccine immunogens already tested in human clinical trials and that reduced risk of infection is correlated with antibodies of these specificities (2–4, 79), the data presented here help us better understand the potential mechanisms by which V3 and V2i Abs may decrease HIV-1 acquisition.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by NIH grants R01 AI102740 (C.E.H.) and HIVRAD P01 AI100151 (S.Z.-P.) and by research funds from the Henry M. Jackson Foundation and the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development.

We thank Constance Williams and Vincenza Itri for providing MAbs, Florian Klein for pMX-gp160Δc-IRES-GFP plasmids, Victoria Polonis, Sebastian Mark Molnar, and Morgan Watts for the BaL.ec1 pseudovirus, Sodsai Tovanabutra for the CM244.OR plasmid, Michael Tuen for general laboratory support, and Susanne Tranguch for reviewing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 27 August 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Rerks-Ngarm S, Pitisuttithum P, Nitayaphan S, Kaewkungwal J, Chiu J, Paris R, Premsri N, Namwat C, de Souza M, Adams E, Benenson M, Gurunathan S, Tartaglia J, McNeil JG, Francis DP, Stablein D, Birx DL, Chunsuttiwat S, Khamboonruang C, Thongcharoen P, Robb ML, Michael NL, Kunasol P, Kim JH. 2009. Vaccination with ALVAC and AIDSVAX to prevent HIV-1 infection in Thailand. N. Engl. J. Med. 361:2209–2220. 10.1056/NEJMoa0908492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haynes BF, Gilbert PB, McElrath MJ, Zolla-Pazner S, Tomaras GD, Alam SM, Evans DT, Montefiori DC, Karnasuta C, Sutthent R, Liao HX, DeVico AL, Lewis GK, Williams C, Pinter A, Fong Y, Janes H, DeCamp A, Huang Y, Rao M, Billings E, Karasavvas N, Robb ML, Ngauy V, de Souza MS, Paris R, Ferrari G, Bailer RT, Soderberg KA, Andrews C, Berman PW, Frahm N, De Rosa SC, Alpert MD, Yates NL, Shen X, Koup RA, Pitisuttithum P, Kaewkungwal J, Nitayaphan S, Rerks-Ngarm S, Michael NL, Kim JH. 2012. Immune-correlates analysis of an HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial. N. Engl. J. Med. 366:1275–1286. 10.1056/NEJMoa1113425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zolla-Pazner S, Decamp A, Gilbert PB, Williams C, Yates NL, Williams WT, Howington R, Fong Y, Morris DE, Soderberg KA, Irene C, Reichman C, Pinter A, Parks R, Pitisuttithum P, Kaewkungwal J, Rerks-Ngarm S, Nitayaphan S, Andrews C, O'Connell RJ, Yang ZY, Nabel GJ, Kim JH, Michael NL, Montefiori DC, Liao HX, Haynes BF, Tomaras GD. 2014. Vaccine-induced IgG antibodies to V1V2 regions of multiple HIV-1 subtypes correlate with decreased risk of HIV-1 infection. PLoS One 9:e87572. 10.1371/journal.pone.0087572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zolla-Pazner S, deCamp AC, Cardozo T, Karasavvas N, Gottardo R, Williams C, Morris DE, Tomaras G, Rao M, Billings E, Berman P, Shen X, Andrews C, O'Connell RJ, Ngauy V, Nitayaphan S, de Souza M, Korber B, Koup R, Bailer RT, Mascola JR, Pinter A, Montefiori D, Haynes BF, Robb ML, Rerks-Ngarm S, Michael NL, Gilbert PB, Kim JH. 2013. Analysis of V2 antibody responses induced in vaccinees in the ALVAC/AIDSVAX HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial. PLoS One 8:e53629. 10.1371/journal.pone.0053629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rolland M, Edlefsen PT, Larsen BB, Tovanabutra S, Sanders-Buell E, Hertz T, deCamp AC, Carrico C, Menis S, Magaret CA, Ahmed H, Juraska M, Chen L, Konopa P, Nariya S, Stoddard JN, Wong K, Zhao H, Deng W, Maust BS, Bose M, Howell S, Bates A, Lazzaro M, O'Sullivan A, Lei E, Bradfield A, Ibitamuno G, Assawadarachai V, O'Connell RJ, deSouza MS, Nitayaphan S, Rerks-Ngarm S, Robb ML, McLellan JS, Georgiev I, Kwong PD, Carlson JM, Michael NL, Schief WR, Gilbert PB, Mullins JI, Kim JH. 2012. Increased HIV-1 vaccine efficacy against viruses with genetic signatures in Env V2. Nature 490:417–420. 10.1038/nature11519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spurrier B, Sampson J, Gorny MK, Zolla-Pazner S, Kong XP. 2014. Functional implications of the binding mode of a human conformation-dependent V2 monoclonal antibody against HIV. J. Virol. 88:4100–4112. 10.1128/JVI.03153-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liao HX, Bonsignori M, Alam SM, McLellan JS, Tomaras GD, Moody MA, Kozink DM, Hwang KK, Chen X, Tsao CY, Liu P, Lu X, Parks RJ, Montefiori DC, Ferrari G, Pollara J, Rao M, Peachman KK, Santra S, Letvin NL, Karasavvas N, Yang ZY, Dai K, Pancera M, Gorman J, Wiehe K, Nicely NI, Rerks-Ngarm S, Nitayaphan S, Kaewkungwal J, Pitisuttithum P, Tartaglia J, Sinangil F, Kim JH, Michael NL, Kepler TB, Kwong PD, Mascola JR, Nabel GJ, Pinter A, Zolla-Pazner S, Haynes BF. 2013. Vaccine induction of antibodies against a structurally heterogeneous site of immune pressure within HIV-1 envelope protein variable regions 1 and 2. Immunity 38:176–186. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonsignori M, Pollara J, Moody MA, Alpert MD, Chen X, Hwang KK, Gilbert PB, Huang Y, Gurley TC, Kozink DM, Marshall DJ, Whitesides JF, Tsao CY, Kaewkungwal J, Nitayaphan S, Pitisuttithum P, Rerks-Ngarm S, Kim JH, Michael NL, Tomaras GD, Montefiori DC, Lewis GK, DeVico A, Evans DT, Ferrari G, Liao HX, Haynes BF. 2012. Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity-mediating antibodies from an HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial target multiple epitopes and preferentially use the VH1 gene family. J. Virol. 86:11521–11532. 10.1128/JVI.01023-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker LM, Phogat SK, Chan-Hui PY, Wagner D, Phung P, Goss JL, Wrin T, Simek MD, Fling S, Mitcham JL, Lehrman JK, Priddy FH, Olsen OA, Frey SM, Hammond PW, Kaminsky S, Zamb T, Moyle M, Koff WC, Poignard P, Burton DR. 2009. Broad and potent neutralizing antibodies from an African donor reveal a new HIV-1 vaccine target. Science 326:285–289. 10.1126/science.1178746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonsignori M, Hwang KK, Chen X, Tsao CY, Morris L, Gray E, Marshall DJ, Crump JA, Kapiga SH, Sam NE, Sinangil F, Pancera M, Yongping Y, Zhang B, Zhu J, Kwong PD, O'Dell S, Mascola JR, Wu L, Nabel GJ, Phogat S, Seaman MS, Whitesides JF, Moody MA, Kelsoe G, Yang X, Sodroski J, Shaw GM, Montefiori DC, Kepler TB, Tomaras GD, Alam SM, Liao HX, Haynes BF. 2011. Analysis of a clonal lineage of HIV-1 envelope V2/V3 conformational epitope-specific broadly neutralizing antibodies and their inferred unmutated common ancestors. J. Virol. 85:9998–10009. 10.1128/JVI.05045-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore PL, Gray ES, Sheward D, Madiga M, Ranchobe N, Lai Z, Honnen WJ, Nonyane M, Tumba N, Hermanus T, Sibeko S, Mlisana K, Abdool Karim SS, Williamson C, Pinter A, Morris L. 2011. Potent and broad neutralization of HIV-1 subtype C by plasma antibodies targeting a quaternary epitope including residues in the V2 loop. J. Virol. 85:3128–3141. 10.1128/JVI.02658-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayr LM, Cohen S, Spurrier B, Kong XP, Zolla-Pazner S. 2013. Epitope mapping of conformational V2-specific anti-HIV human monoclonal antibodies reveals an immunodominant site in V2. PLoS One 8:e70859. 10.1371/journal.pone.0070859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorny MK, Moore JP, Conley AJ, Karwowska S, Sodroski J, Williams C, Burda S, Boots LJ, Zolla-Pazner S. 1994. Human anti-V2 monoclonal antibody that neutralizes primary but not laboratory isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 68:8312–8320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lyumkis D, Julien JP, de Val N, Cupo A, Potter CS, Klasse PJ, Burton DR, Sanders RW, Moore JP, Carragher B, Wilson IA, Ward AB. 2013. Cryo-EM structure of a fully glycosylated soluble cleaved HIV-1 envelope trimer. Science 342:1484–1490. 10.1126/science.1245627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Julien JP, Cupo A, Sok D, Stanfield RL, Lyumkis D, Deller MC, Klasse PJ, Burton DR, Sanders RW, Moore JP, Ward AB, Wilson IA. 2013. Crystal structure of a soluble cleaved HIV-1 envelope trimer. Science 342:1477–1483. 10.1126/science.1245625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLellan JS, Pancera M, Carrico C, Gorman J, Julien JP, Khayat R, Louder R, Pejchal R, Sastry M, Dai K, O'Dell S, Patel N, Shahzad-ul-Hussan S, Yang Y, Zhang B, Zhou T, Zhu J, Boyington JC, Chuang GY, Diwanji D, Georgiev I, Kwon YD, Lee D, Louder MK, Moquin S, Schmidt SD, Yang ZY, Bonsignori M, Crump JA, Kapiga SH, Sam NE, Haynes BF, Burton DR, Koff WC, Walker LM, Phogat S, Wyatt R, Orwenyo J, Wang LX, Arthos J, Bewley CA, Mascola JR, Nabel GJ, Schief WR, Ward AB, Wilson IA, Kwong PD. 2011. Structure of HIV-1 gp120 V1/V2 domain with broadly neutralizing antibody PG9. Nature 480:336–343. 10.1038/nature10696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorny MK, Pan R, Williams C, Wang XH, Volsky B, O'Neal T, Spurrier B, Sampson JM, Li L, Seaman MS, Kong XP, Zolla-Pazner S. 2012. Functional and immunochemical cross-reactivity of V2-specific monoclonal antibodies from HIV-1-infected individuals. Virology 427:198–207. 10.1016/j.virol.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krachmarov CP, Honnen WJ, Kayman SC, Gorny MK, Zolla-Pazner S, Pinter A. 2006. Factors determining the breadth and potency of neutralization by V3-specific human monoclonal antibodies derived from subjects infected with clade A or clade B strains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 80:7127–7135. 10.1128/JVI.02619-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y, Cleveland B, Klots I, Travis B, Richardson BA, Anderson D, Montefiori D, Polacino P, Hu SL. 2008. Removal of a single N-linked glycan in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 results in an enhanced ability to induce neutralizing antibody responses. J. Virol. 82:638–651. 10.1128/JVI.01691-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guttman M, Kahn M, Garcia NK, Hu SL, Lee KK. 2012. Solution structure, conformational dynamics, and CD4-induced activation in full-length, glycosylated, monomeric HIV gp120. J. Virol. 86:8750–8764. 10.1128/JVI.07224-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lusso P, Earl PL, Sironi F, Santoro F, Ripamonti C, Scarlatti G, Longhi R, Berger EA, Burastero SE. 2005. Cryptic nature of a conserved, CD4-inducible V3 loop neutralization epitope in the native envelope glycoprotein oligomer of CCR5-restricted, but not CXCR4-using, primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains. J. Virol. 79:6957–6968. 10.1128/JVI.79.11.6957-6968.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mbah HA, Burda S, Gorny MK, Williams C, Revesz K, Zolla-Pazner S, Nyambi PN. 2001. Effect of soluble CD4 on exposure of epitopes on primary, intact, native human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virions of different genetic clades. J. Virol. 75:7785–7788. 10.1128/JVI.75.16.7785-7788.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCaffrey RA, Saunders C, Hensel M, Stamatatos L. 2004. N-linked glycosylation of the V3 loop and the immunologically silent face of gp120 protects human immunodeficiency virus type 1 SF162 from neutralization by anti-gp120 and anti-gp41 antibodies. J. Virol. 78:3279–3295. 10.1128/JVI.78.7.3279-3295.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar R, Tuen M, Liu J, Nadas A, Pan R, Kong X, Hioe CE. 2013. Elicitation of broadly reactive antibodies against glycan-modulated neutralizing V3 epitopes of HIV-1 by immune complex vaccines. Vaccine 31:5413–5421. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Binley JM, Ban YE, Crooks ET, Eggink D, Osawa K, Schief WR, Sanders RW. 2010. Role of complex carbohydrates in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection and resistance to antibody neutralization. J. Virol. 84:5637–5655. 10.1128/JVI.00105-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Platt EJ, Wehrly K, Kuhmann SE, Chesebro B, Kabat D. 1998. Effects of CCR5 and CD4 cell surface concentrations on infections by macrophagetropic isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 72:2855–2864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein F, Gaebler C, Mouquet H, Sather DN, Lehmann C, Scheid JF, Kraft Z, Liu Y, Pietzsch J, Hurley A, Poignard P, Feizi T, Morris L, Walker BD, Fatkenheuer G, Seaman MS, Stamatatos L, Nussenzweig MC. 2012. Broad neutralization by a combination of antibodies recognizing the CD4 binding site and a new conformational epitope on the HIV-1 envelope protein. J. Exp. Med. 209:1469–1479. 10.1084/jem.20120423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pietzsch J, Scheid JF, Mouquet H, Klein F, Seaman MS, Jankovic M, Corti D, Lanzavecchia A, Nussenzweig MC. 2010. Human anti-HIV-neutralizing antibodies frequently target a conserved epitope essential for viral fitness. J. Exp. Med. 207:1995–2002. 10.1084/jem.20101176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li M, Gao F, Mascola JR, Stamatatos L, Polonis VR, Koutsoukos M, Voss G, Goepfert P, Gilbert P, Greene KM, Bilska M, Kothe DL, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Wei X, Decker JM, Hahn BH, Montefiori DC. 2005. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env clones from acute and early subtype B infections for standardized assessments of vaccine-elicited neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 79:10108–10125. 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10108-10125.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nyambi PN, Mbah HA, Burda S, Williams C, Gorny MK, Nadas A, Zolla-Pazner S. 2000. Conserved and exposed epitopes on intact, native, primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virions of group M. J. Virol. 74:7096–7107. 10.1128/JVI.74.15.7096-7107.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pinter A, Honnen WJ, He Y, Gorny MK, Zolla-Pazner S, Kayman SC. 2004. The V1/V2 domain of gp120 is a global regulator of the sensitivity of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates to neutralization by antibodies commonly induced upon infection. J. Virol. 78:5205–5215. 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5205-5215.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gorny MK, Conley AJ, Karwowska S, Buchbinder A, Xu JY, Emini EA, Koenig S, Zolla-Pazner S. 1992. Neutralization of diverse human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants by an anti-V3 human monoclonal antibody. J. Virol. 66:7538–7542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gorny MK, Williams C, Volsky B, Revesz K, Wang XH, Burda S, Kimura T, Konings FA, Nadas A, Anyangwe CA, Nyambi P, Krachmarov C, Pinter A, Zolla-Pazner S. 2006. Cross-clade neutralizing activity of human anti-V3 monoclonal antibodies derived from the cells of individuals infected with non-B clades of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 80:6865–6872. 10.1128/JVI.02202-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hioe CE, Wrin T, Seaman MS, Yu X, Wood B, Self S, Williams C, Gorny MK, Zolla-Pazner S. 2010. Anti-V3 monoclonal antibodies display broad neutralizing activities against multiple HIV-1 subtypes. PLoS One 5:e10254. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diskin R, Scheid JF, Marcovecchio PM, West AP, Jr, Klein F, Gao H, Gnanapragasam PN, Abadir A, Seaman MS, Nussenzweig MC, Bjorkman PJ. 2011. Increasing the potency and breadth of an HIV antibody by using structure-based rational design. Science 334:1289–1293. 10.1126/science.1213782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burton DR, Barbas CF, III, Persson MA, Koenig S, Chanock RM, Lerner RA. 1991. A large array of human monoclonal antibodies to type 1 human immunodeficiency virus from combinatorial libraries of asymptomatic seropositive individuals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88:10134–10137. 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trkola A, Purtscher M, Muster T, Ballaun C, Buchacher A, Sullivan N, Srinivasan K, Sodroski J, Moore JP, Katinger H. 1996. Human monoclonal antibody 2G12 defines a distinctive neutralization epitope on the gp120 glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 70:1100–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Montefiori DC. 2005. Evaluating neutralizing antibodies against HIV, SIV, and SHIV in luciferase reporter gene assays. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. Chapter 12:Unit 12.11. 10.1002/0471142735.im1211s64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Decker JM, Bibollet-Ruche F, Wei X, Wang S, Levy DN, Wang W, Delaporte E, Peeters M, Derdeyn CA, Allen S, Hunter E, Saag MS, Hoxie JA, Hahn BH, Kwong PD, Robinson JE, Shaw GM. 2005. Antigenic conservation and immunogenicity of the HIV coreceptor binding site. J. Exp. Med. 201:1407–1419. 10.1084/jem.20042510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoffman TL, LaBranche CC, Zhang W, Canziani G, Robinson J, Chaiken I, Hoxie JA, Doms RW. 1999. Stable exposure of the coreceptor-binding site in a CD4-independent HIV-1 envelope protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:6359–6364. 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salzwedel K, Smith ED, Dey B, Berger EA. 2000. Sequential CD4-coreceptor interactions in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Env function: soluble CD4 activates Env for coreceptor-dependent fusion and reveals blocking activities of antibodies against cryptic conserved epitopes on gp120. J. Virol. 74:326–333. 10.1128/JVI.74.1.326-333.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiang SH, Doka N, Choudhary RK, Sodroski J, Robinson JE. 2002. Characterization of CD4-induced epitopes on the HIV type 1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein recognized by neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 18:1207–1217. 10.1089/08892220260387959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Y, Rey-Cuille MA, Hu SL. 2001. N-linked glycosylation in the V3 region of HIV type 1 surface antigen modulates coreceptor usage in viral infection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 17:1473–1479. 10.1089/08892220152644179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scanlan CN, Ritchie GE, Baruah K, Crispin M, Harvey DJ, Singer BB, Lucka L, Wormald MR, Wentworth P, Jr, Zitzmann N, Rudd PM, Burton DR, Dwek RA. 2007. Inhibition of mammalian glycan biosynthesis produces non-self antigens for a broadly neutralising, HIV-1 specific antibody. J. Mol. Biol. 372:16–22. 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Israel ZR, Gorny MK, Palmer C, McKeating JA, Zolla-Pazner S. 1997. Prevalence of a V2 epitope in clade B primary isolates and its recognition by sera from HIV-1-infected individuals. AIDS 11:128–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shotton C, Arnold C, Sattentau Q, Sodroski J, McKeating JA. 1995. Identification and characterization of monoclonal antibodies specific for polymorphic antigenic determinants within the V2 region of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 69:222–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mao Y, Wang L, Gu C, Herschhorn A, Desormeaux A, Finzi A, Xiang SH, Sodroski JG. 2013. Molecular architecture of the uncleaved HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein trimer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110:12438–12443. 10.1073/pnas.1307382110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bartesaghi A, Merk A, Borgnia MJ, Milne JL, Subramaniam S. 2013. Prefusion structure of trimeric HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein determined by cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20:1352–1357. 10.1038/nsmb.2711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mao Y, Wang L, Gu C, Herschhorn A, Xiang SH, Haim H, Yang X, Sodroski J. 2012. Subunit organization of the membrane-bound HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein trimer. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19:893–899. 10.1038/nsmb.2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khayat R, Lee JH, Julien JP, Cupo A, Klasse PJ, Sanders RW, Moore JP, Wilson IA, Ward AB. 2013. Structural characterization of cleaved, soluble HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein trimers. J. Virol. 87:9865–9872. 10.1128/JVI.01222-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wyatt R, Moore J, Accola M, Desjardin E, Robinson J, Sodroski J. 1995. Involvement of the V1/V2 variable loop structure in the exposure of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 epitopes induced by receptor binding. J. Virol. 69:5723–5733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gzyl J, Bolesta E, Wierzbicki A, Kmieciak D, Naito T, Honda M, Komuro K, Kaneko Y, Kozbor D. 2004. Effect of partial and complete variable loop deletions of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein on the breadth of gp160-specific immune responses. Virology 318:493–506. 10.1016/j.virol.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang CC, Tang M, Zhang MY, Majeed S, Montabana E, Stanfield RL, Dimitrov DS, Korber B, Sodroski J, Wilson IA, Wyatt R, Kwong PD. 2005. Structure of a V3-containing HIV-1 gp120 core. Science 310:1025–1028. 10.1126/science.1118398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pantophlet R, Wilson IA, Burton DR. 2004. Improved design of an antigen with enhanced specificity for the broadly HIV-neutralizing antibody b12. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 17:749–758. 10.1093/protein/gzh085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ma BJ, Alam SM, Go EP, Lu X, Desaire H, Tomaras GD, Bowman C, Sutherland LL, Scearce RM, Santra S, Letvin NL, Kepler TB, Liao HX, Haynes BF. 2011. Envelope deglycosylation enhances antigenicity of HIV-1 gp41 epitopes for both broad neutralizing antibodies and their unmutated ancestor antibodies. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002200. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kolchinsky P, Kiprilov E, Bartley P, Rubinstein R, Sodroski J. 2001. Loss of a single N-linked glycan allows CD4-independent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection by altering the position of the gp120 V1/V2 variable loops. J. Virol. 75:3435–3443. 10.1128/JVI.75.7.3435-3443.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pancera M, Shahzad-Ul-Hussan S, Doria-Rose NA, McLellan JS, Bailer RT, Dai K, Loesgen S, Louder MK, Staupe RP, Yang Y, Zhang B, Parks R, Eudailey J, Lloyd KE, Blinn J, Alam SM, Haynes BF, Amin MN, Wang LX, Burton DR, Koff WC, Nabel GJ, Mascola JR, Bewley CA, Kwong PD. 2013. Structural basis for diverse N-glycan recognition by HIV-1-neutralizing V1-V2-directed antibody PG16. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20:804–813. 10.1038/nsmb.2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stanfield R, Cabezas E, Satterthwait A, Stura E, Profy A, Wilson I. 1999. Dual conformations for the HIV-1 gp120 V3 loop in complexes with different neutralizing fabs. Structure 7:131–142. 10.1016/S0969-2126(99)80020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jiang X, Burke V, Totrov M, Williams C, Cardozo T, Gorny MK, Zolla-Pazner S, Kong XP. 2010. Conserved structural elements in the V3 crown of HIV-1 gp120. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17:955–961. 10.1038/nsmb.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Binley JM, Wrin T, Korber B, Zwick MB, Wang M, Chappey C, Stiegler G, Kunert R, Zolla-Pazner S, Katinger H, Petropoulos CJ, Burton DR. 2004. Comprehensive cross-clade neutralization analysis of a panel of anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 monoclonal antibodies. J. Virol. 78:13232–13252. 10.1128/JVI.78.23.13232-13252.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harada S, Yusa K, Monde K, Akaike T, Maeda Y. 2005. Influence of membrane fluidity on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 329:480–486. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aldunate M, Tyssen D, Johnson A, Zakir T, Sonza S, Moench T, Cone R, Tachedjian G. 2013. Vaginal concentrations of lactic acid potently inactivate HIV. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68:2015–2025. 10.1093/jac/dkt156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Klebanoff SJ, Coombs RW. 1991. Viricidal effect of Lactobacillus acidophilus on human immunodeficiency virus type 1: possible role in heterosexual transmission. J. Exp. Med. 174:289–292. 10.1084/jem.174.1.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Klebanoff SJ, Kazazi F. 1995. Inactivation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by the amine oxidase-peroxidase system. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2054–2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Haim H, Salas I, McGee K, Eichelberger N, Winter E, Pacheco B, Sodroski J. 2013. Modeling virus- and antibody-specific factors to predict human immunodeficiency virus neutralization efficiency. Cell Host Microbe 14:547–558. 10.1016/j.chom.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zolla-Pazner S. 2005. Improving on nature: focusing the immune response on the V3 loop. Hum. Antibodies 14:69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barouch DH, Whitney JB, Moldt B, Klein F, Oliveira TY, Liu J, Stephenson KE, Chang HW, Shekhar K, Gupta S, Nkolola JP, Seaman MS, Smith KM, Borducchi EN, Cabral C, Smith JY, Blackmore S, Sanisetty S, Perry JR, Beck M, Lewis MG, Rinaldi W, Chakraborty AK, Poignard P, Nussenzweig MC, Burton DR. 2013. Therapeutic efficacy of potent neutralizing HIV-1-specific monoclonal antibodies in SHIV-infected rhesus monkeys. Nature 503:224–228. 10.1038/nature12744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Scheid JF, Mouquet H, Feldhahn N, Seaman MS, Velinzon K, Pietzsch J, Ott RG, Anthony RM, Zebroski H, Hurley A, Phogat A, Chakrabarti B, Li Y, Connors M, Pereyra F, Walker BD, Wardemann H, Ho D, Wyatt RT, Mascola JR, Ravetch JV, Nussenzweig MC. 2009. Broad diversity of neutralizing antibodies isolated from memory B cells in HIV-infected individuals. Nature 458:636–640. 10.1038/nature07930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mascola JR, Lewis MG, Stiegler G, Harris D, VanCott TC, Hayes D, Louder MK, Brown CR, Sapan CV, Frankel SS, Lu Y, Robb ML, Katinger H, Birx DL. 1999. Protection of macaques against pathogenic simian/human immunodeficiency virus 89.6PD by passive transfer of neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 73:4009–4018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mascola JR, Stiegler G, VanCott TC, Katinger H, Carpenter CB, Hanson CE, Beary H, Hayes D, Frankel SS, Birx DL, Lewis MG. 2000. Protection of macaques against vaginal transmission of a pathogenic HIV-1/SIV chimeric virus by passive infusion of neutralizing antibodies. Nat. Med. 6:207–210. 10.1038/72318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Perelson AS, Neumann AU, Markowitz M, Leonard JM, Ho DD. 1996. HIV-1 dynamics in vivo: virion clearance rate, infected cell life-span, and viral generation time. Science 271:1582–1586. 10.1126/science.271.5255.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ribeiro RM, Qin L, Chavez LL, Li D, Self SG, Perelson AS. 2010. Estimation of the initial viral growth rate and basic reproductive number during acute HIV-1 infection. J. Virol. 84:6096–6102. 10.1128/JVI.00127-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gallo SA, Reeves JD, Garg H, Foley B, Doms RW, Blumenthal R. 2006. Kinetic studies of HIV-1 and HIV-2 envelope glycoprotein-mediated fusion. Retrovirology 3:90. 10.1186/1742-4690-3-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sato H, Orenstein J, Dimitrov D, Martin M. 1992. Cell-to-cell spread of HIV-1 occurs within minutes and may not involve the participation of virus particles. Virology 186:712–724. 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90038-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hubner W, McNerney GP, Chen P, Dale BM, Gordon RE, Chuang FY, Li XD, Asmuth DM, Huser T, Chen BK. 2009. Quantitative 3D video microscopy of HIV transfer across T cell virological synapses. Science 323:1743–1747. 10.1126/science.1167525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Martin N, Welsch S, Jolly C, Briggs JA, Vaux D, Sattentau QJ. 2010. Virological synapse-mediated spread of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 between T cells is sensitive to entry inhibition. J. Virol. 84:3516–3527. 10.1128/JVI.02651-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Arthos J, Cicala C, Martinelli E, Macleod K, Van Ryk D, Wei D, Xiao Z, Veenstra TD, Conrad TP, Lempicki RA, McLaughlin S, Pascuccio M, Gopaul R, McNally J, Cruz CC, Censoplano N, Chung E, Reitano KN, Kottilil S, Goode DJ, Fauci AS. 2008. HIV-1 envelope protein binds to and signals through integrin alpha4beta7, the gut mucosal homing receptor for peripheral T cells. Nat. Immunol. 9:301–309. 10.1038/ni1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Perez LG, Chen H, Liao HX, Montefiori DC. 2014. Envelope glycoprotein binding to the integrin α4β7 complex is not a general property of most HIV-1 strains. J. Virol. 88:10767–10777. 10.1128/JVI.03296-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gottardo R, Bailer RT, Korber BT, Gnanakaran S, Phillips J, Shen X, Tomaras GD, Turk E, Imholte G, Eckler L, Wenschuh H, Zerweck J, Greene K, Gao H, Berman PW, Francis D, Sinangil F, Lee C, Nitayaphan S, Rerks-Ngarm S, Kaewkungwal J, Pitisuttithum P, Tartaglia J, Robb ML, Michael NL, Kim JH, Zolla-Pazner S, Haynes BF, Mascola JR, Self S, Gilbert P, Montefiori DC. 2013. Plasma IgG to linear epitopes in the V2 and V3 regions of HIV-1 gp120 correlate with a reduced risk of infection in the RV144 vaccine efficacy trial. PLoS One 8:e75665. 10.1371/journal.pone.0075665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]