ABSTRACT

Poxviruses are composed of large double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) genomes coding for several hundred genes whose variation has supported virus adaptation to a wide variety of hosts over their long evolutionary history. Comparative genomics has suggested that the Orthopoxvirus genus in particular has undergone reductive evolution, with the most recent common ancestor likely possessing a gene complement consisting of all genes present in any existing modern-day orthopoxvirus species, similar to the current Cowpox virus species. As orthopoxviruses adapt to new environments, the selection pressure on individual genes may be altered, driving sequence divergence and possible loss of function. This is evidenced by accumulation of mutations and loss of protein-coding open reading frames (ORFs) that progress from individual missense mutations to gene truncation through the introduction of early stop mutations (ESMs), gene fragmentation, and in some cases, a total loss of the ORF. In this study, we have constructed a whole-genome alignment for representative isolates from each Orthopoxvirus species and used it to identify the nucleotide-level changes that have led to gene content variation. By identifying the changes that have led to ESMs, we were able to determine that short indels were the major cause of gene truncations and that the genome length is inversely proportional to the number of ESMs present. We also identified the number and types of protein functional motifs still present in truncated genes to assess their functional significance.

IMPORTANCE This work contributes to our understanding of reductive evolution in poxviruses by identifying genomic remnants such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and indels left behind by evolutionary processes. Our comprehensive analysis of the genomic changes leading to gene truncation and fragmentation was able to detect some of the remnants of these evolutionary processes still present in orthopoxvirus genomes and suggests that these viruses are under continual adaptation due to changes in their environment. These results further our understanding of the evolutionary mechanisms that drive virus variation, allowing orthopoxviruses to adapt to particular environmental niches. Understanding the evolutionary history of these virus pathogens may help predict their future evolutionary potential.

INTRODUCTION

Members of the Poxviridae family are large double-stranded DNA viruses, capable of infecting insects, birds, reptiles, and many mammalian species (1). Interestingly, some of these viruses infect a broad range of hosts while others can infect only one host. Particular virus-host combinations determine disease severity, which ranges from no symptoms to mild disease and to severe disease with high mortality rates (2).

These viruses are of ongoing interest because of their potential use as agents of bioterrorism and their use in gene therapy and as emerging diseases. Variola virus, the causative agent of smallpox, has been eradicated in nature; however, there is still the possibility of accidental or intentional release (3), and it is currently listed as a category A biological agent by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (4). Some poxviruses have natural oncolytic activity, and recombinant poxviruses may be effective vehicles for cancer vaccine delivery, especially since they can accept as much as 25 kb of foreign DNA integrated into their genomes (2, 5). Another concern is the potential for viruses that currently cause zoonotic disease, such as monkeypox virus in Africa, camelpox virus (CMLV) and buffalopox virus in the Middle East and India, and cowpox virus in Europe, to develop adaptations allowing more-effective transmission to and between humans (6, 7).

Poxvirus genomes range from approximately 133,000 to 360,000 bp and carry 133 to 328 genes. The central region of the genome is highly conserved and contains genes coding for proteins involved in transcription, DNA replication, and virion assembly (8). The genes located toward the ends of the genomes are generally involved in immunomodulation and host range activities; and since their activity may have been selected for by interactions with particular hosts, the presence or absence and sequence of these genes are much more variable when comparing different virus isolates (9, 10). Structurally, the ends of the genomes contain inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) and hairpin loops, which are required for viral DNA replication (11). The ITRs vary in size between isolates, and especially between species; for example, in variola viruses, they are 200 to 500 bases long and do not contain any genes; however, the longest ITRs can be up to 13 kb long and contain several genes, which are therefore present as diploid copies for that isolate (8).

The Orthopoxvirus genus contains several important species that can produce disease in humans, including Variola virus (VARV), Monkeypox virus (MPXV), and Cowpox virus (CPXV) (1). Vaccinia virus (VACV), which was used to generate the vaccine against variola during the smallpox eradication campaign, is also a member of this genus (12). Mirroring the family as a whole, the Orthopoxvirus genus contains a wide spectrum of viruses that vary extensively with respect to their host range and genome size. Orthopoxviruses range in size from just over 185,000 bp in VARV to approximately 225,000 bp in CPXV (8). Humans are the only hosts of VARV, and members of the species Ectromelia virus (ECTV) have a restricted host range and may be capable of causing disease in mice only (13). On the other hand, cowpox virus has the broadest known host range for an orthopoxvirus (14), including humans, cattle, and domestic cats, and has been detected in large felines, elephants, alpacas, and beavers showing symptoms of CPXV-like disease at European zoos (15). Despite these differences, the orthopoxviruses are closely related immunologically and infection with one can confer immunity against the others (11).

The major mechanisms that are involved in the evolution of Poxviridae species include horizontal gene transfer from host to virus (and possibly from other viruses), single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), small indels (insertions and deletions), gene loss, and possibly recombination (16). In contrast, members of the Orthopoxvirus genus appear to have diverged from their most recent common ancestor mainly through SNPs, small indels, and gene loss, resulting in, for some species, smaller genome sizes though a process of reductive evolution (8). Horizontal gene transfer does not seem to have contributed to the evolution of orthopoxviruses, since CPXV isolates contain all of the genes present in all of the other members of the genus (8) and may therefore possess a gene complement similar to that of the most recent common ancestor of the genus (16–18). These data suggest that orthopoxviruses may have adapted to their particular environmental niches through a loss in selection pressure to maintain the coding sequence of genes necessary only for successful replication and spread of the virus in other environments, resulting in an accumulation of mutations in these genes. This may have eventually led to the complete loss of expression of some of these genes, which are generally located toward the ends of the genomes, and which are often predicted to have roles in host interactions (8, 19). This is not to discount the role of adaptive mutations in orthopoxvirus genes. For example, when the coding regions from 45 variola virus isolates were compared, 1,782 SNPs were identified, with 67 genes containing polymorphic sites that distinguish West African midrange case fatality rate (CFR) isolates from alastrim low-range CFR isolates (20). Also, when a vaccinia virus with a maladapted K3L gene was grown in cells expressing the antiviral protein kinase R (PKR), a compensatory amino acid substitution, H47R, was detected after a few generations, which made the viral K3L much more effective at inhibiting PKR and increasing the overall fitness of the virus (21).

Although there is a wealth of information in the literature regarding gene content in poxviruses and evolutionary relationships between orthopoxvirus isolates (16), the molecular mechanisms involved in the response to changes in selection pressures leading to speciation have yet to be determined. Modern orthopoxviruses may have evolved through a process beginning with the accumulation of gene-specific SNPs and small indel mutations eventually leading to complete gene loss. To investigate these mechanisms in more detail, in this study we took a more comprehensive look at the specific nucleotide changes that may impact gene function in orthopoxviruses. This included the construction and use of a full-length genomic multiple-sequence alignment (MSA) for representative isolates of all orthopoxvirus species with available complete genomic sequences. This MSA served as the basis for our analysis, focusing on the identification of the specific nucleotide changes that lead to the truncation or fragmentation of virus genes as well as the determination of conserved patterns of mutation present across phylogenetic clusters of these viruses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genome sequences and assessment of gene content.

We chose representative isolates from each species within the Orthopoxvirus genus with available complete genome sequences (at the time this study began), and which represented unique clades within each species (Table 1). Nucleotide sequences were downloaded from the Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (vbrc.org) (22). These genomes were determined using Sanger sequencing.

TABLE 1.

Orthopoxvirus genomes used for these analyses

| Species and NCBI name and strain | Abbreviation | No. of haploid genes (no. of genes in each ITR) | Length (bp) | ITR length (bp)a | GC% | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cowpox virus | ||||||

| Cowpox virus strain Germany 91-3 | CPXV-Ger | 211 (5) | 228,250 | 7,374 | 33.5 | DQ437593 |

| Cowpox virus strain Brighton Red | CPXV-BR | 209 (5) | 224,499 | 9,710 | 33.4 | AF482758 |

| Cowpox virus strain GRI-90 | CPXV-Gri | 212 (5) | 223,666 | 8,303 | 33.7 | X94355 |

| Vaccinia virus | ||||||

| Vaccinia virus strain WR (Western Reserve) | VACV-WR | 190 (6) | 194,711 | 10,186; (3′ region, 10,195) | 33.3 | AY243312 |

| Horsepox virus strain MNR-76 | HSPV | 203 (5) | 212,633 | 7,527 | 33.1 | DQ792504 |

| Rabbitpox virus strain Utrecht | RPXV | 192 (6) | 197,731 | 10,022 | 33.5 | AY484669 |

| Monkeypox virus | ||||||

| Monkeypox virus strain MPXV-WRAIR7-61; Walter Reed 267 | MPXV-WR | 182 (6) | 199,195 | 8,749 | 33.1 | AY603973 |

| Monkeypox virus strain Zaire-96-I-16 | MPXV-ZAI | 183 (4) | 196,858 | 6,378 | 33.1 | AF380138 |

| Taterapox virus | ||||||

| Taterapox virus strain Dahomey 1968 | TATV | 189 (3) | 198,050 | 4,779 | 33.3 | DQ437594 |

| Camelpox virus | ||||||

| Camelpox virus strain M-96 from Kazakhstan | CMLV | 188 (3) | 205,719 | 7,736 | 33.2 | AF438165 |

| Ectromelia virus | ||||||

| Ectromelia virus strain Moscow | ECTV | 193 (5) | 209,771 | 9,413 | 33.2 | AF012825 |

| Variola virus | ||||||

| Variola virus strain Brazil 1966 (v66-39 Sao Paulo) | VARV-BRZ | 180 (0) | 188,062 | 518 | 32.7 | DQ441419 |

| Variola virus strain Sierra Leone 1969 (V68-258) | VARV-SLN | 179 (0) | 187,014 | 196 | 32.7 | DQ441437 |

| Variola virus strain South Africa 1965 (103 T'vaal, Nelspruit) | VARV-SAF | 179 (0) | 185,881 | 526 | 32.7 | DQ441436 |

| Variola virus strain Kuwait 1967 (K1629) | VARV-KUW | 179 (0) | 185,853 | 522 | 32.7 | DQ441433 |

The lengths of the ITRs should be considered approximate and were determined by finding the number of complementary bases at each end of the genomic sequences; see Hendrickson et al. (8) for more information. The VACV-WR genome was fully sequenced through each end, so the 3′ ITR length is reported because it is slightly different from the 5′ length.

The Poxvirus Genome Annotation System (PGAS) was used to consistently determine the coding potential of each open reading frame (ORF) of all virus isolates and annotate predicted genes according to their coding state, i.e., intact, truncated, fragmented, or missing genes, as described by Hendrickson et al. (8). Briefly, the PGAS contains a computational pipeline that assesses the functional status of a gene using a variety of analyses, including BLAST (23), searches of all ORFs longer than 30 amino acids, conservation of functional motifs, conserved orthology and synteny, presence of a predicted promoter sequence, and a significant Glimmer score (24), representing conservation of gene sequence coding potential. The PGAS also provides a graphical user interface that supports the manual comparison of syntenic regions in closely related strains or species, as well as the neighboring ORFs within that region. An ORF was considered intact if it was similar in length to the longest representative ORF for orthologs of that gene in other orthopoxvirus species. Truncated genes were defined as genes greater than 30 amino acids long that retained a predicted promoter sequence but were <80% of the amino acid length of intact orthologs. This cutoff is based on a comparison of gene length conservation (as defined by Hendrickson et al. [8]). Fragmented genes were identified as genomic regions containing identifiable homologous sequence to an orthologous, intact ORF, but with the fragmented ORF containing <30 amino acids, missing a predicted promoter region, or missing the 5′ end of the gene, including a start codon. ORFs that were flagged as potential genes through automated prediction but did not have an identified promoter, had an absent or weak Kozak consensus sequence, had a low Glimmer score, and showed no orthology with intact orthopoxvirus genes were considered artifacts and were not labeled as genes or gene remnants. To differentiate orthologous from paralogous genes, we assessed sequence homology as well as gene synteny, the conservation of genomic location and gene neighbors (25). We utilized the term “syntelog” to represent orthologous genes shared across isolates with a common syntenic genome location (8).

Table S1 in the supplemental materials provides a listing of all the genes analyzed. The genes are organized in the order in which they appear in the genomes, and genes are identified according to their ViPR locus ID (26), their syntelog number, and their corresponding VACV-COP homolog name, if available (8, 22).

Multiple-sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree construction.

An initial MSA of all whole-genome sequences was performed using MAFFT (27) as implemented in the Geneious software package (Geneious version 6.1.7 from Biomatters). This initial alignment was then extensively edited by hand and was also segmented into 3 regional alignments for analysis: the 5′ region spans positions 1 to 61,890 of the MSA (including gaps), the central region consists of positions 61,891 to 181,788, and the 3′ region consists of positions 181,789 to 258,241. The program JModelTest v2 (28, 29) was used to assess the evolutionary models that best fit the alignment data based on the corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc). For the whole-genome, 5′ region, and 3′ region sequences, the model selected was the “General Time Reversible plus Invariant sites plus Gamma distributed rate variation among sites” model (GTR+I+G). The best model identified for the central region was the “Transversion plus Invariant sites plus Gamma distributed rate variation among sites” model (TVM+I+G); however, the TVM models are not able to be implemented in MrBayes 3.1.2 (30, 31), and the model with the next-best fit, GTR+I+G, was selected. A FASTA-formatted file for each of the alignment segments was converted to the Nexus format using the format conversion tool from the HCV Sequence Database provided by Los Alamos National Laboratory (hcv.lanl.gov/content/sequence/FORMAT_CONVERSION/form.html) and manually edited for minor formatting changes required by MrBayes. The FASTA-formatted alignment was also converted to the PIR format using ClustalX 2.0.12 (32). There is some evidence to suggest that including indels (insertions and deletions) within an MSA increases the accuracy of phylogenetic prediction compared to treating gaps as unknown characters or deleting columns containing gaps (the default behavior of MrBayes) (33–35). Since 103,299 of the 258,241 columns in the orthopoxvirus whole-genome MSA contain at least 1 gap, we used the simple indel coding method of the GapCoder program (36) (all indels with the same start and end positions are considered to be matching characters) to create a gap data MSA. For each alignment, the nucleotide sequence and gap-data MSAs were included as 2 partitions for analysis using Bayesian phylogenetic inference as implemented by MrBayes. The nucleotide model was set to GTR+I+G, and four Markov chains were run for 100,000 generations, with samples taken every 100 generations. The chains converged significantly, and the average standard deviation of split frequencies was <0.01 at the end of the analysis. A burn-in value of 25% was used to discard samples biased by the start of the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analysis, and the remaining samples were used to generate a majority rule consensus tree, which was visualized and edited using Dendroscope 3.2.8 (37).

We also used the PhyloBayes (38) MPI tool provided on the CIPRES Science Gateway (39) to construct phylogenetic trees based on the alignments of the whole genomes and 5′, center, and 3′ regions of the orthopoxvirus genomes. The trees produced with PhyloBayes were very similar to the trees produced using MrBayes (data not shown).

Detection of variation and early stop mutations.

Gene sequence variation was detected within Geneious, with the minimum variant frequency set to zero. For each position in the alignment, any variant present in <50% of the isolates was included in the analyses, and the changes included were characterized as indels or single nucleotide polymorphisms. Each position in an indel was counted as 1 change. Indels present in the first 4,601 positions and the last 4,316 positions of the whole-genome MSA were not counted when assessing the variants present in individual genomes. These regions represent the noncoding telomeres and contain short repeated subunits, for which the number of repetitions of the subunits is highly variable (15). Large duplications that were present in only a few genomes were also not counted when quantifying the extent of variation. These large duplications covered positions 11,762 to 20,143 (CMLV, ECTV, and RPXV), 20,961 to 21,626 (CPXV-Ger), 33,078 to 34,680 (MPXV-WR), 230,447 to 233,395 (VACV-WR), and 247,174 to 249,861 (MPXV-WR and MPXV-ZAI) of the whole-genome MSA.

Early-stop mutations (ESMs) are defined as mutations that give rise to a stop codon in the sequence of a gene that either interrupts the start codon or truncates the ORF to a length 80% or less of the length of the intact orthologous gene. ESMs were identified by aligning nucleotide sequences with their amino acid translations and annotating mutations that introduced a stop codon, altered the reading frame, or altered the start codon of a gene. In the case of an altered reading frame, the mutation that caused the change in reading frame is coded as the ESM and not the newly introduced (now in-frame) stop codon.

Protein functional motifs.

Prediction of functional motifs present in the intact genes of CPXV-Ger, which was used as a reference, was carried out using InterProScan 4 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/pfa/iprscan5/ [40]). For the few genes in CPXV-Ger that were not intact, the gene sequence from CPXV-Gri was used (see Results). Coding sequences covering large duplications (see above) were not included in the analysis.

RESULTS

Multiple-sequence alignment.

An accurate MSA lays the foundation for genetic analyses, including determining phylogenetic relationships. Previously, most phylogenetic trees for the genus Orthopoxvirus were based on the conserved central portion of the genomes or on concatenated gene sequences (8, 41). The exception is the work done by Darin Carroll et al. (42), which used whole-genome sequences to differentiate monophyletic groups between CPXV species. For our work, we aligned whole genomes for isolates representing each clade within each species of the genus, with the exception of the North American orthopoxviruses, for which whole-genome sequences were not yet available (Table 1 and Fig. 1). The complete multiple-sequence alignment is provided as the FASTA file in the supplemental materials (see Dataset S1 in the supplemental material). We also annotated each potential gene using the classification scheme from Hendrickson et al. (8), which predicts the state of the genes as intact, truncated, or fragmented (see Table S1 in the supplemental materials). Intact genes are annotated based on the longest ORF present for all syntenic orthologs (with the exception of two genes that have large numbers of repeats extending the length of the gene, i.e., ECTV ViPR CV-44/syntelog group 29, an apoptosis inhibitor, and an MPXV-WR syntelog group 187, a gene of unknown function [8]). Truncated genes were defined as those genes that were less than 80% of the length of the longest intact syntenic ORF. A gene was considered fragmented if a homologous and syntenic nucleotide sequence was still present but the 5′ region of the gene had been deleted or if the 5′ ORF was less than 30 bp. Figure 1 also displays the location of the ITRs for each isolate outlined in purple. Although the ITR at either end of any one isolate is an exact duplicate, in order to provide the most accurate alignment possible among all genome sequences, the 5′ and 3′ ITRs for a single isolate often appear to be of different lengths due to the introduction of indels that accommodate the alignment of sequences present in other isolates outside their ITR region.

FIG 1.

Genome alignment. A multiple-sequence alignment (MSA) of representative orthopoxviruses is presented. A histogram of sequence conservation (nucleotide identity) is presented above the sequences. The locations of the central and end regions are shown below the sequences. Thick black lines indicate the presence of nucleotide sequence, intermediate black lines represent nucleotides interspersed with short gap insertions, and thin black lines indicate runs of gaps. Green arrows below the sequence lines mark intact genes, gray arrows mark truncated genes, and yellow arrows mark fragmented ORFs. The purple bars overlaying the sequence lines illustrate the positions of the ITRs. The SINE sequence present in TATV, which is the only nonancestral sequence detected, is denoted by a red bar.

When considered as a group, the genome sequences of all cowpox viruses contain syntenic regions homologous to the genomic sequences of isolates from all other species. The only exception is the presence of a short interspersed element (SINE) sequence in taterapox virus (TATV), previously reported by Piskurek and Okada (43). Cowpox viruses therefore appear to be more ancestral-like when assessed according to genome sequence content or gene content, since their genomic and gene sequences can be considered to be a superset of the genome and gene sequences present in all other orthopoxvirus species (8).

The whole-genome alignment supports visualization of large duplications present in some of the isolates, as well as mapping of their likely origins (Fig. 2). Large duplications were defined as sequences of at least 500 bases unique to one isolate (or two isolates in the case of one of the MPXV duplications) that were present in a region of a genomic sequence that was not syntenic with the other isolates in that region of the genome (Table 2). These regions of “unique” sequence were determined to be duplications, since they showed homology with a sequence present on the opposite side of the MSA that was syntenic within the other orthopoxvirus species. This syntenic region in which homologous sequence could be identified in several isolates was considered to be the putative origin of the duplication. Differences in the sizes of the origin and the duplication sequences as displayed in Fig. 2 are due to the addition of gap characters within the MSA and do not reflect significant differences between the sizes of the origin and duplication. All of these duplications map to regions of the genome that are present within or near the ends of an ITR. It may be possible that some of these duplications arose due to a contraction or expansion of the ITR, leaving a remnant of the original ITR sequence near the 5′ or 3′ end of the genome, near the border of the current ITR region.

FIG 2.

Large genomic duplications. The duplications characterized in Table 2 are displayed as ribbons within the graph, with black circles indicating the proposed origin, providing the direction of the duplication. The tick marks refer to the base position (in thousands of bases) within the whole-genome MSA (Fig. 1). The positions of the ITRs for each genome are displayed outside the graph. Isolate abbreviations are provided in the center of the graph and are the same color as the duplication ribbons and the ITRs. MPXV-ZAI and MPXV-WR share the darker purple duplication.

TABLE 2.

Large genomic duplications

| Isolate | Position of duplication |

Ungapped length (bp) | Within ITR? | Position of origin in MSA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome | MSA | ||||

| CMLV | 9,161–10,912 | 11,762–13,531 | 1,752 | No | 243,822–242,185 |

| ECTV | 4,954–9,528 | 12,691–17,396 | 4,574 | Yes | 238,396–243,013 |

| RPXV | 8,254–11,754 | 15,295–20,143 | 3,501 | Partially | 227,699–233,787 |

| CPXV-Ger | 8,243–8,908 | 20,961–21,626 | 666 | No | 229,543–230,129 |

| MPXV-WR | 7,154–8,748 | 33,078–34,680 | 1,595 | Yes | 243,116–247,173 |

| VACV-WR | 184,497–187,445 | 230,447–233,395 | 2,949 | Yes | 37,601–40,695 |

| MPXV-WR | 191,932–194,615 | 247,174–249,861 | 2,684 | Yes | 8,596–33,077 |

| MPXV-ZAI | 189,669–192,176 | 247,174–249,861 | 2,508 | Partially | 8,596–33,077 |

As shown in Table 3, the pairwise identities for the isolates used in this study (including gapped positions) range from 77.2% (between VACV-WR and CPXV-Ger) to 99.8% (between VARV-SAF and VARV-KUW); however, when gaps are not considered, the pairwise identities increase to between 95.3% and 99.8%, respectively, with 95.3% representing the lowest pairwise identity for a comparison between ECTV and each of the VARV isolates.

TABLE 3.

Pairwise nucleotide % identities for orthopoxvirus isolates used in this study (excluding the telomeres)a

| Isolate | CPXV-Ger | CPXV-BR | CPXV-Gri | VACV-WR | HSPV | RPXV | MPXV-WR | MPXV-ZAI | TATV | CMLV | ECTV | VARV-KUW | VARV-SAF | VARV-BRZ | VARV-SLN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPXV-Ger | 98.0 | 97.6 | 97.4 | 97.0 | 97.4 | 96.9 | 96.9 | 97.3 | 97.1 | 96.2 | 96.6 | 96.6 | 96.6 | 96.5 | |

| CPXV-BR | 92.7 | 97.2 | 97.0 | 96.7 | 97.0 | 96.6 | 96.6 | 96.7 | 96.4 | 96.0 | 96.0 | 96.0 | 96.0 | 95.9 | |

| CPXV-Gri | 93.1 | 94.2 | 98.5 | 98.1 | 98.5 | 97.7 | 97.7 | 97.7 | 97.5 | 96.7 | 96.9 | 96.9 | 96.9 | 96.9 | |

| VACV-WR | 77.2 | 79.5 | 80.5 | 98.9 | 99.2 | 97.5 | 97.5 | 97.6 | 97.3 | 96.3 | 96.8 | 96.8 | 96.8 | 96.8 | |

| HSPV | 88.6 | 90.6 | 92.6 | 84.9 | 98.9 | 97.2 | 97.2 | 97.3 | 97.1 | 96.0 | 96.6 | 96.6 | 96.6 | 96.6 | |

| RPXV | 79.3 | 81.7 | 82.7 | 90.6 | 87.2 | 97.5 | 97.5 | 97.6 | 97.3 | 96.4 | 96.8 | 96.8 | 96.8 | 96.8 | |

| MPXV-WR | 79.0 | 80.8 | 82.2 | 82.7 | 83.2 | 80.7 | 99.6 | 96.9 | 96.6 | 96.0 | 96.2 | 96.2 | 96.1 | 96.1 | |

| MPXV-ZAI | 79.5 | 81.4 | 82.8 | 83.3 | 83.7 | 81.3 | 94.9 | 96.9 | 96.6 | 96.0 | 96.2 | 96.2 | 96.1 | 96.1 | |

| TATV | 82.1 | 82.8 | 83.3 | 86.0 | 85.0 | 82.9 | 84.4 | 85.1 | 99.0 | 96.0 | 98.4 | 98.4 | 98.4 | 98.4 | |

| CMLV | 83.3 | 83.0 | 83.4 | 82.9 | 85.2 | 83.3 | 80.7 | 82.2 | 89.8 | 95.8 | 98.2 | 98.2 | 98.1 | 98.1 | |

| ECTV | 81.2 | 83.3 | 83.9 | 79.7 | 82.5 | 78.3 | 77.9 | 78.6 | 80.9 | 79.4 | 95.4 | 95.3 | 95.3 | 95.3 | |

| VARV-KUW | 79.6 | 80.6 | 80.9 | 84.4 | 84.3 | 83.5 | 81.2 | 83.4 | 88.6 | 87.7 | 79.7 | 99.9 | 99.7 | 99.7 | |

| VARV-SAF | 79.5 | 80.6 | 80.9 | 84.4 | 84.3 | 83.5 | 81.1 | 83.3 | 88.6 | 87.7 | 79.7 | 99.8 | 99.7 | 99.7 | |

| VARV-BRZ | 80.1 | 80.6 | 81.0 | 84.4 | 84.3 | 83.6 | 81.2 | 83.4 | 89.0 | 87.8 | 79.6 | 98.5 | 98.6 | 99.8 | |

| VARV-SLN | 80.0 | 80.5 | 81.0 | 84.4 | 84.3 | 83.5 | 81.1 | 83.3 | 88.9 | 87.8 | 79.6 | 98.5 | 98.5 | 99.6 |

The data above the diagonal were calculated after deleting all positions containing gaps; data below the diagonal include gapped positions.

For the purposes of this study, the genomes were divided into 3 sections, which we refer to as 5′, center, and 3′, in an attempt to better understand the genetic and evolutionary differences behind the conserved central portion and the more-variable ends of the genomes (Fig. 1). The delineation of the borders between the regions is somewhat arbitrary but generally demarcates the more-variable ends of the genomes from the conserved, central regions. The majority of syntenic gene groups (referred to as syntelog groups in Table S1 in the supplemental material) that have at least one truncated, fragmented, or missing member are located toward the ends of the genomes in the 5′ and 3′ regions of the alignment (Table 4). The average pairwise identity in the 5′ region is about 10% lower than in the 3′ region (60% versus 70% identity, including gaps), while the central region is much more conserved (96.5% identity).

TABLE 4.

Characteristics of the 5′, center, and 3′ regions of the whole-genome alignment

| Region | MSA length (bp)a | CPXV-Ger length (bp)b | Avg pairwise identity (%) | No. of intact syntelogsc | No. of syntelogs with fragmented/truncated genesd | % of genes fragmented/truncated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5′ | 61,890 | 46,184 | 59.1 | 6 | 37 | 42 |

| Center | 119,898 | 117,703 | 96.5 | 111 | 12 | 13 |

| 3′ | 76,455 | 64,360 | 70.8 | 11 | 41 | 45 |

Including gapped positions.

Excluding gapped positions.

Orthologous, syntenic gene groups.

Syntenic groups containing at least one truncated, fragmented, or missing member.

Phylogenetic tree reconstruction.

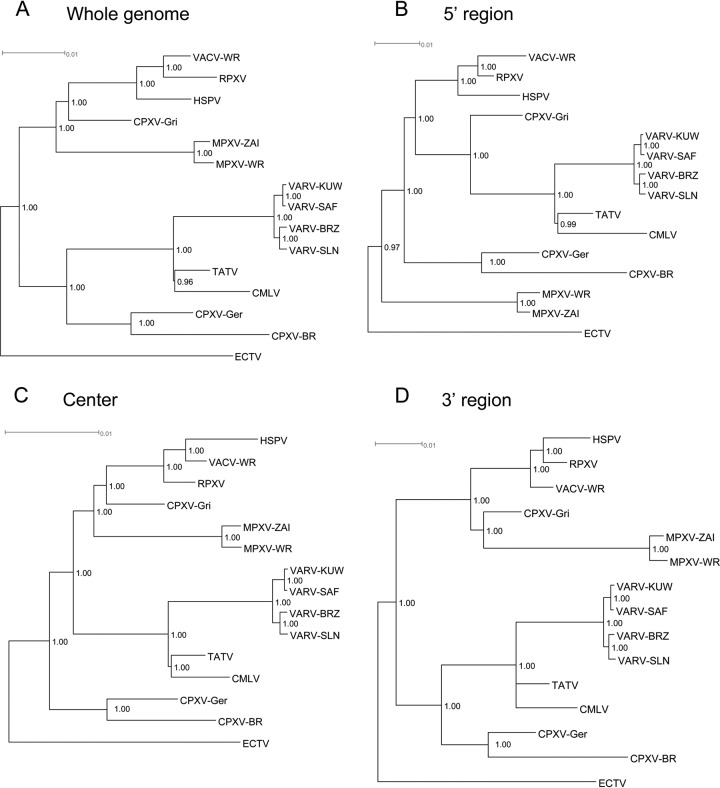

The construction of a complete genomic sequence alignment for these orthopoxvirus isolates allows us to better understand the phylogenetic relationships between these viruses and especially the differences in phylogenetic signals and therefore differences in evolutionary rates and selection pressures between the central, 5′, and 3′ regions of the genomes. Figure 3A shows a Bayesian tree based on the genome-length nucleotide alignment. The phylogeny of the whole genomes shows that the VARVs are a sister group to TATV and CMLV, and together they form a sister group to CPXV-Ger and CPXV-BR (cowpox virus groups 2 and 3, respectively, as described by Carroll et al. [42]). The other major branch is composed of the vaccinia viruses, including RPXV and horsepox virus (HSPV), their sister group CPXV-Gri (cowpox virus group 5), and the more distantly related monkeypox viruses. Carroll et al. have concluded that the cowpox viruses most likely represent at least 2 different clades, and they classify them into 5 different potential species (42), although they are still unique with respect to other orthopoxvirus species in that they all retain a mostly comprehensive orthopoxvirus gene set. The tree also indicates that ECTV belongs in a single, isolated clade with the greatest phylogenetic distance to the other isolates, as shown previously (8, 19). One possible interpretation is that ECTV diverged from the rest of the orthopoxvirus species (with the possible exception of the North American orthopoxviruses [41]) early in the history of the genus, due to its adaptation to an environment that imposed selection pressures different from those of its orthopoxvirus relatives. Other than the vaccinia virus branch and some slight differences between the TATV and CMLV nodes, this phylogenetic prediction agrees closely with previous trees for the genus Orthopoxvirus (18, 25, 44–49).

FIG 3.

Phylogenies resulting from DNA sequences of the whole genome (A), the 5′ region (B), the center (C), and the 3′ region (D) of the selected orthopoxvirus genomes. Phylogenies were inferred using Bayesian methods under the GTR+I+G nucleotide substitution model. Indel positions were included in the analysis as separate characters. Numbers at internal nodes provide clade credibility values for each node. Table 4 shows the positions for the 5′, center, and 3′ regions.

One difference between this whole-genome tree and the tree that we previously presented (in reference 8) using 141 concatenated gene sequences is the relationship between the vaccinia virus group of isolates (HSPV, RPXV, and VACV-WR). In the present phylogenetic reconstruction, HSPV diverges from the other vaccinia viruses prior to the divergence of VACV-WR and RPXV. However, for the gene concatenation alignment, RPXV is the earliest divergent member of the entire vaccinia virus clade, while HSPV forms a clade with three other vaccinia virus isolates, including VACV-WR, but is located at the end of a longer, extended branch. Most available vaccinia virus complete-genome sequences have been derived from virus stocks that have undergone multiple laboratory passages designed to attenuate virulence and support vaccine design (50, 51). The passage history of RPXV also appears to be complex, and its historical relationship to modern-day vaccinia virus strains remains difficult to trace. One possibility is that RPXV represents a laboratory-based, rabbit-adapted strain of vaccinia virus that originated from an early vaccinia virus strain in the 1930s (52). HSPV has undergone minimal passage, and therefore its sequence should better reflect the sequence of its ancestral counterpart (53). The sequences of the laboratory-derived strains of vaccinia virus and rabbitpox virus (RPXV) may therefore have diverged significantly, especially in the more-variable 5′ and 3′ ends of the genomes, in comparison to HSPV. These differences may result in the differences in tree topology seen when comparing the phylogeny constructed from the whole-genome alignment to the concatenated, conserved gene alignment. It is also possible that multiple recombination events between the vaccinia virus isolates as well as some of the other orthopoxvirus isolates may have obscured some of the phylogenetic relationships that have been inferred from these sequence alignments (54, 55).

The variable ends of the genomes reflect the unique evolutionary history of each virus and the influence of different hosts. In order to differentiate the contributions to phylogenetic prediction made by the variable ends of the genomes, we constructed phylogenetic trees for each region individually (Fig. 3B to D). The phylogenetic relationships described by the center (Fig. 3C) and 3′ (Fig. 3D) regions of the MSA are similar to the relationships for the phylogenetic tree of the whole alignment. The major differences include the relationships within the vaccinia virus clade and the position of the monkeypox virus branch as a monophyletic clade with CPXV-Gri on the 3′ region tree, as opposed to CPXV-Gri forming a monophyletic clade with the vaccinia viruses on the center region tree, with MPXV diverging just prior to the VACV-CPXV clade. The latter tree topology is more common and is the topology reflected by the whole-genome as well as center region trees.

The phylogeny generated from the 5′ region alignment (Fig. 3B) exhibits a greater number of differences than does the phylogeny of the whole-genome alignment or the center or 3′ region trees. Therefore, the 5′ region of these orthopoxviruses may be under greater and/or more-variable selection pressure than the other regions of these genomes. Many of the genes present in this region are unique to the cowpox virus isolates, with a few CPXV orthologs also conserved in HSPV or ECTV (see Table S1 in the supplemental materials). This suggests that these 5′ region genes were present in the most recent common ancestor to the entire Orthopoxvirus genus. However, in many orthopoxvirus isolates, large coding sequence deletions that have resulted in the complete removal of many of these genes in non-CPXV species are present. These large deletions may account for the significant changes seen in the 5′ region phylogeny.

There has been some debate as to whether horsepox virus is an example of a natural “wild” virus or of an escaped vaccine strain. The position of HSPV in previously published phylogenies is variable, with some showing HSPV as a descendant of the vaccinia viruses (as our center and 3′ region trees show), and other studies agreeing with our whole-genome results, which indicate that an HSPV-like virus was the predecessor to current VACV isolates. In this study, we identified several sequence regions between 2,041 and 10,639 bases long that are present in HSPV but not in VACV or RPXV (Fig. 4), possibly indicating that both these viruses were derived from an HSPV-like ancestor rather than having HSPV descending from the VACV clade. This is consistent with the hypothesis that HSPV is a natural virus whose ancestor may have been the origin of modern-day vaccinia and rabbitpox viruses, which over time have become adapted to long-term laboratory passage (11, 52). It is possible that these HSPV sequences were obtained through recombination with a cowpox virus ancestor, though this would have required at least three separate recombination events to produce the patterns seen in modern-day HSPV (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

HSPV sequences absent in RPXV and VACV. Each panel displays a segment of the whole-genome alignment, with the original location within the MSA indicated along the top of the panel. Thick black lines indicate the presence of nucleotides, and thin black lines represent gaps in the alignment. Intact and truncated ORFs are shown as green and gray arrows, respectively. Sequence that is present in HSPV but has been deleted from either or both RPXV or VACV-WR is highlighted with red lines. Early stop mutations (ESMs) are shown as vertical red bars. In the top panel, a total of 2,898 bases are missing in VACV-WR. RPXV and VACV-WR each exhibit deletions of 10,639 bases in the middle panel. In the bottom panel, RPXV is missing a total of 8,925 bases and VACV-WR is missing a total of 11,778 bases.

Genetic variation.

In order to investigate the impact of sequence variation on virus evolution and gene function among Orthopoxvirus species, we identified nucleotide variants consisting of indels and SNPs in all ORFs that have been annotated as functional genes in any virus isolate. We did not include the terminal hairpin loops, concatemer resolution motifs, or tandem repeat sequences in our analysis, since these regions were difficult to align and in many instances have not been sequenced and do not contain coding sequence. The overall frequency of indels that are present for all analyzed sequences is approximately 93.1 per 1,000 bases, while the frequency of SNPs is 18.4 per 1,000 bases. Each base present in an indel was counted as one variant when calculating the frequency provided above. These data emphasize that when considering variation at the single-nucleotide level, the insertion or deletion of a base is a much more frequent event than a base substitution. In many cases, it is difficult to determine whether any particular base in any one genome that is present in a region deleted in another genome represents an insertion event or a deletion event. This determination will also change depending on which genome is used as a reference. Ideally, we would use the sequence of the progenitor virus to the genus as the reference to make this determination. But since that virus sequence is not available, we have chosen instead to report the frequency of indels rather than make a determination of insertion or deletion events. (A cowpox virus-like reference ancestral sequence could potentially be constructed and used to assess the frequency of insertions versus deletions throughout all existing orthopoxvirus isolates.)

The distribution of SNPs remains relatively constant throughout coding or formerly coding regions; however, the number of indels is higher in fragmented gene ORFs than in intact or truncated genes (Fig. 5). As illustrated in Fig. 6A, a “sliding window” of 100 bases was used to determine the position and frequency of indels in each isolate, so that a data point with y of 40%, for example, indicates that for the 100-bp sequence at that position, 40 characters consist of gaps. The number of gaps is much higher toward the ends of the genomes, where there is a higher frequency of large duplications and large deletions that often affect more than one ORF. There is also a greater frequency of short repeats of variable length toward the ends of the genome that also increase the gap frequency in these regions. The major peaks in the central region of the genomes generally reflect gaps due to variable-length short repeats (syntelog group numbers 29, 33, between 51 and 52, between 86 and 87, 113, 118, and 135) and the TATV SINE (within syntelog group number 33). Shorter peaks are small deletions usually limited to a single ORF. The lengths of deletions in the multiple-sequence alignment are highly variable; the vast majority of deletions cover a single base, but there are also deletions that are greater than 20,000 bp long (Fig. 6B).

FIG 5.

Sequence variation in intact, truncated, and fragmented genes. Gene variants categorized as SNPs or indels are quantitated according to their presence in intact, truncated, or fragmented genes. Variants in the truncated region of an ORF are those that occur prior to the stop codon that interrupts a truncated gene, and variants in the degraded region of a truncated ORF occur after the stop codon that interrupts a truncated gene.

FIG 6.

Frequency of orthopoxvirus deletions. (A) Each point on this graph shows the percentage of positions that consist of gaps within a sliding window of 100 bp for each isolate. This graph does not include the extreme ends of alignments, and the 0% and 100% y axis values are expanded vertically in order to allow separation of data points that would otherwise overlap. Each isolate is shown individually at each position. (B) Distribution of gap size for each isolate in the MSA after removal of the telomeres and large duplications. Each gap length bin (x axis) is colored according to the number of gaps present in each isolate.

Early-stop mutations.

Previously, we described how gene loss, in addition to accumulation of SNPs and small indels, is one of the primary drivers of orthopoxvirus speciation (8). In order to better understand the process of gene truncation and gene loss, we have identified the early stop mutations (ESMs) that are responsible for gene truncation or fragmentation. ESMs lead to stop codons within the normal coding region of a gene and are identified in the reading frame of the original ATG start codon; they are often followed by an out-of-frame stop codon further downstream in the gene. The ESMs include indels that shift the reading frame, SNPs that result in a nonsense mutation, and large deletions that decrease the length of the ORF to 80% or less of the length of an intact gene or delete the start codon.

Figure 7A illustrates the ESMs in the ankyrin repeat domain-containing protein CP77, which codes for a host range factor (56). CP77 has been reported to inhibit nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and has also been referred to as CPXV025, ViPR locus ID CV-22 (26), Bang-D8L (CPXV-BR-025 gene detail; Poxvirus Bioinformatics Resource Center [http://poxvirus.org/gene_detail.asp?gene_id=41724]), Host Range Protein 1 (Q8QN36 [CP77_CWPXB]; UniProt Consortium [http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q8QN36), VHR1 (VHR1 host range protein [Cowpox virus]; National Center for Biotechnology Information [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/1485900]), and CHOhr (19). Its 668 amino acids contain 9 predicted ankyrin repeats and a PRANC/F-box-like motif. Chang et al. (56) found that the 6 ankyrin repeats located closest to the N terminus of the protein bind the p65 subunit of cellular NF-κB. The C-terminal PRANC motif binds to Cullin-1 and Skp1 of the SCF complex, which normally ubiquitinates IκBα, preventing the release of NF-κB to the nucleus; both regions of the protein are required for NF-κB inactivation. Most of the CP77 orthologs are bracketed by a gene of unknown function (short ORF appearing on the left side of Fig. 7A) and by a gene that codes for an interleukin-18 (IL-18)-binding protein that appears on the right side of Fig. 7A. Early-stop mutations resulting from indels are shown as red squares, ESMs resulting from nonsense SNPs are shown as red triangles, and sequence deletions longer than 30 bp are represented by orange lines overlapping the gaps in the aligned sequences. As can be seen in Fig. 7A, the pattern of ESMs as well as the fragmentation pattern of the CP77 gene is generally conserved between closely related viruses. The CP77 ORF in vaccinia and related viruses has been truncated at the same position, and VACV-WR, RPXV, and HSPV all share the same 3 ESMs. A 4th ESM is shared by VACV-WR and HSPV. The variola viruses all have truncated CP77 homologs, and despite having variable ORF lengths, all share a 624-bp deletion, along with several other shared ESMs. Interestingly, CP77 remains intact in TATV, while it is truncated or missing in its most closely related evolutionary relatives, VARV and CMLV.

FIG 7.

Example of early stop mutations. Excerpts from the whole-genome alignment, with the nucleotide alignment shown as black bars and breaks in the bars representing gaps. Intact and truncated ORFs are shown as green and gray arrows, respectively. ESMs consisting of indels that lead to frame shifts and truncation of the ORF are shown as red squares, and ESMs due to nonsense SNPs are shown as red triangles. Large deletions are marked as transparent orange lines overlaying the nucleotide track. Orange hatch marks represent deletions within a truncated gene that maintain the reading frame following the deletion. The numbers above the alignments refer to the positions in the whole-genome alignment. (A) CP77 gene. The alignment has been reversed for this figure so that all genes run from left to right. (B) IL-1β receptor homolog gene.

In Fig. 7B, we show the genes corresponding to VACV-COP B16R (ViPR locus ID CV-193 [26]), which codes for an IL-1β receptor homolog, as well as the ESMs interrupting some of the ORFs. IL-1β is a proinflammatory cytokine produced by cells in response to viral infection. When the viral IL-1β receptor homolog is secreted, it prevents signal transduction and the normal antiviral response (57). The intact gene is 981 bp; however, RPXV has an indel that truncates the ORF to 624 bp. The indel is in the same position as an indel in CMLV; however, the 2 viruses are not thought to be closely related, and these indels most likely do not indicate recombination, as they occur in a stretch of AT repeats. Similarly, the first ESMs in MPXV-WR and CMLV are indels that occur in a stretch of 7 threonine residues, which also contains indels in the variola viruses. Each of the variola viruses has also had the threonine deleted from the initiation ATG codon. Similar patterns of shared ESMs, truncations, and deletions are seen for many other orthopoxvirus genes (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Some genes that are truncated or fragmented contain only 1 or 2 ESMs; however, others have accumulated additional deleterious changes, such as CP77 in ECTV, which contains 10 ESMs. The number of ESMs present in any one truncated or fragmented gene ranged from 1 to 11, with the highest number present in the fragmented Schlafen protein gene in VARV-KUW and VARV-SAF (ViPR locus ID CV-180 [26]) and the MPXV-WR A-type inclusion protein (ViPR locus ID CV-145).

Not only is there variety in the number of ESMs present per nonintact gene, but also the length of the ESM indels varies across all of the virus isolate sequences analyzed. For all isolates, there were a total of 706 deletions, 195 insertions, and 115 nonsense SNPs that led to early-stop mutations in coding regions. The majority of deletions coded as ESMs have a length of 1 bp, and the median deletion size was 2 bp; however, the longest was over 18,000 bp (Fig. 8). Both of the largest ESMs due to deletions were found in VACV-WR.

FIG 8.

Length of deletions that result in ESMs. Each bin in this histogram indicates the number of deletions of the indicated length present across all analyzed virus isolates. The x axis is divided into 100-bp-length bins; however, the graph labels are shown at only 500-bp intervals. The indicated length does not include gaps inserted due to insertions in other sequences. The y axis, on a log scale, displays the number of occurrences of each deletion of the indicated size. Bins for deletions of up to 50 bp have been magnified in the inset graph; bins from 1 to 9 are at intervals of 1 bp, bins from 10 to 50 are at intervals of 10 bp, and the y axis is on a linear scale.

The frequency of ESMs present in a genome is inversely associated with the length of that genome (R2 = 0.77) (Fig. 9A). All cowpox viruses cluster together in a region of low ESM number, despite being sufficiently different at the nucleotide level to have a large phylogenetic distance. The variola viruses also cluster together, as do the laboratory-propagated vaccinia virus and its close relative rabbitpox virus. Interestingly, horsepox virus does not cluster with VACV and RPXV, suggesting that laboratory passage for VACV and RPXV has contributed to a reduction in the number of ESMs present in these genomes due to the presence of long deletions in their 5′ and 3′ regions. This finding provides support for the hypotheses that genome reduction represents a significant mechanism that drives virus evolution within the Orthopoxvirus genus. Viruses with shorter genomes that have lost the greatest number of genes show a correspondingly high number of genes that are becoming increasingly truncated and fragmented due to the accumulation of greater numbers of ESMs.

FIG 9.

Frequency of ESMs in orthopoxvirus genomes. (A) Relationship between genome length and ESM frequency. Related isolates that are located close to each other on the graph are circled. (B) Distribution of ESMs for each isolate relative to gene state.

We wanted to determine if the number of ESMs per ORF differed depending on whether a gene was truncated or fragmented. Figure 9B displays the frequency of ESMs across all truncated or fragmented genes for each genome. In general, fragmented genes have a greater number of ESMs than do truncated genes, with averages of 4.8 ESMs per 1,000 bases in fragmented genes and 3.2 ESMs per 1,000 bases in truncated genes. This ratio varies by isolate, and some isolates such as MPXV-ZAI, VACV-WR, and RPXV have more ESMs in their truncated genes than in fragmented genes (Fig. 9B). One factor that complicates this result is that the genomes with the highest numbers of truncated and fragmented genes also contain the highest numbers of deletions, and some of the ESMs may have been removed from the now-deleted regions since they first appeared. As indicated above, the low number of ESMs in VACV-WR and RPXV relative to other orthopoxviruses may be due to the large deletions found in their 5′ and 3′ regions.

Protein functional motifs.

Finally, we wanted to make a computational assessment of the impact that protein truncations may have on protein function. While it is not possible to fully assess function without directly assaying for protein activity, the conservation of known functional motifs within the coding sequence can be used as a first-pass computational assessment of possible functional activity. Protein functional motifs were identified using InterProScan (40) and CPXV-Ger as a reference genome. For the five genes truncated or absent in CPXV-Ger, the genes from CPXV-Gri (Cop-A55R, CPXV-Gri D13L, Cop-B25R, Cop-C5L, and CPXV-Gri K2R) were used instead for the protein motif search. For the purposes of this analysis, intact motifs present in the 5′ ORF of truncated proteins were assumed to be transcribed and translated. Degraded motifs are present in ORF fragments following the occurrence of an ESM, and while they still may be part of an mRNA transcript, they would not be translated into a protein. Figure 10A displays the number of functional motifs for each virus detected in intact or truncated proteins, present in degraded gene regions of truncated proteins, or entirely missing. As expected, since cowpox viruses generally contain the complete orthopoxvirus gene set as intact ORFs, the vast majority of their protein motifs remain intact. For the other viruses, between one-third and one-half of their functional motif repertoire is either degraded or missing. Because of the stability of the center region of the genomes compared to the variable ends, more of the genes in the central region have retained intact protein motifs (Fig. 10B). Table 5 contains a listing of all identified protein domains organized by gene position on Fig. 10B. Many of the protein motifs identified toward the ends of the genomes are located following an ESM in a truncated gene (degraded region) or are in a fragmented or missing gene. Orthopoxviruses contain several copies of ankyrin repeat genes toward their ends, and while a few have been determined to interact with host proteins (such as CP77 above), the majority still have functions that have been unexplored (58). Most of these genes (marked with stars in Fig. 10B) contain 7 copies of the ankyrin motif and one copy of a C-terminal PRANC domain. The impact that protein truncation and loss of functional domains have on protein function is entirely theoretical. More research will be needed to fully understand the impact that loss of functional motifs has on the function of individual proteins and the ability of viruses to infect and cause disease in a variety of host species.

FIG 10.

Protein functional motifs by gene state (A) and position of the gene (B). Functional protein motifs were detected using InterProScan. (A) Number of protein motifs for each gene state in each isolate. (B) Number of protein motifs across the genomes, with the relative genomic position of the genes shown on the x axis (see Table 5 for more information on the genes shown). The number of total domains possible is the product of the number of domains present in the intact gene and the number of virus isolates analyzed (i.e., 15). The number of motifs present is the total of all of the motifs in intact genes and motifs found in the 5′ ORF of truncated genes. Ankyrin genes, which contain multiple domains, are marked by stars. The center and variable ends of genomes are indicated below the graph.

TABLE 5.

| Position on Fig. 10B | Syntelog no.b | Gene description | No. of total motifs possiblec | No. of motifs presentd | Functional motif description (no. of motif copies)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | Crm-B secreted TNF-α receptor-like protein | 30 | 19.5 | TNF receptor-II, C-terminal, TNFR/NGFR cysteine-rich region |

| 2 | 3 | Ankyrin-like protein | 120 | 76 | Ankyrin repeat (7), PRANC domain |

| 3 | 4 | Ankyrin-like protein | 120 | 43.5 | Ankyrin repeat (7), PRANC domain |

| 4 | 245 | Kelch-like ring canal protein | 15 | 4 | BTB/POZ-like |

| 5 | 247 | Ankyrin-like protein | 60 | 16 | Ankyrin repeat (3), PRANC domain |

| 6 | 251 | C-type lectin-like protein | 15 | 2.5 | C-type lectin |

| 7 | 265 | Kelch-like ring canal protein | 75 | 10.5 | BTB/Kelch-associated, BTB/POZ-like, Kelch repeat type 1 (3) |

| 8 | 264 | TNF-α receptor-like protein | 15 | 4 | TNFR/NGFR cysteine-rich region |

| 9 | 267 | Ankyrin-like protein | 120 | 32 | Ankyrin repeat (8) |

| 10 | 250 | Ankyrin-like protein | 60 | 24 | Ankyrin repeat (3), PRANC domain |

| 11 | 266 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 135 | 61 | Ankyrin repeat (9) |

| 12 | 8 | Secreted epidermal growth factor-like protein | 15 | 15 | Epidermal growth factor-like domain |

| 13 | 196 | Zinc finger-like protein | 30 | 28 | KilA, N-terminal/APSES-type HTH, DNA-binding; Zinc finger, RING-type |

| 14 | 198 | Ankyrin-like protein | 120 | 71 | Ankyrin repeat (7), PRANC domain |

| 15 | 10 | Ankyrin-like protein | 120 | 72.5 | Ankyrin repeat (7), PRANC domain |

| 16 | 11 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 30 | 19 | TNF receptor-II, C-terminal; SignalP-NN(euk) signal-peptide 1 |

| 17 | 14 | Kelch-like protein | 15 | 10.5 | BTB/Kelch-associated |

| 18 | 16 | Complement binding secreted protein | 60 | 54.5 | Sushi/SCR/CCP (4) |

| 19 | 17 | Kelch-like protein | 75 | 40 | BTB/Kelch-associated, BTB/POZ-like, Kelch repeat type 1 (3) |

| 20 | 21 | Ankyrin-like protein | 105 | 101 | Ankyrin repeat (7) |

| 21 | 23 | Ankyrin-like protein | 75 | 50 | Ankyrin repeat (5) |

| 22 | 25 | Interferon resistance protein | 15 | 13.5 | Ribosomal protein S1-like RNA-binding domain |

| 23 | 26 | Phospholipase D-like protein | 30 | 21 | Phospholipase D/transphosphatidylase (2) |

| 24 | 27 | Putative monoglyceride lipase | 60 | 34 | Alpha/beta hydrolase fold-1 (4) |

| 25 | 31 | Kelch-like protein | 75 | 55 | BTB/POZ-like, BTB/Kelch associated, Kelch repeat type 1 (3) |

| 26 | 38 | Ser/Thr kinase Morph | 15 | 15 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase, active site |

| 27 | 41 | Palmytilated EEV membrane protein | 30 | 30 | Phospholipase D/transphosphatidylase (2) |

| 28 | 47 | Poly(A) polymerase catalytic subunit VP55 | 15 | 15 | Poly(A) polymerase large subunit, poxvirus type 1 |

| 29 | 49 | IFN resistance/PKR inhibitor (Z-DNA binding) | 30 | 26 | dsRNA-specific adenosine deaminase (DRADA), dsRNA-binding domain |

| 30 | 50 | DNA-dependent RNA polymerase subunit rpo30 | 15 | 15 | Zinc finger, TFIIS-type |

| 31 | 51 | Virosome component | 30 | 26 | BEN domain (2) |

| 32 | 55 | DNA polymerase | 45 | 45 | DNA polymerase B exonuclease, N terminal; DNA-directed DNA polymerase, family B (2) |

| 33 | 59 | Glutaredoxin | 15 | 15 | Glutaredoxin active site |

| 34 | 63 | Ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase | 45 | 43 | Ribonucleotide reductase large subunit, C terminal; ribonucleotide reductase large subunit, N terminal; ATP cone |

| 35 | 67 | RNA helicase | 30 | 30 | DNA/RNA helicase, DEAD/DEAH box type, N terminal; helicase, C terminal |

| 36 | 68 | Insulin metalloproteinase-like protein | 15 | 15 | Peptidase M44, metalloendopeptidase G1 |

| 37 | 71 | Thioredoxin-like protein | 15 | 15 | Glutaredoxin active site |

| 38 | 84 | Thymidine kinase | 15 | 15 | Thymidine kinase |

| 39 | 88 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase | 45 | 45 | RNA polymerase subunit (3) |

| 40 | 89 | Tyr/Ser phosphatase, J1L protein | 15 | 15 | Dual specificity phosphatase, subgroup, catalytic domain |

| 41 | 94 | Topoisomerase type IB | 30 | 30 | DNA topoisomerase I, subunit (2) |

| 42 | 96 | Large subunit of mRNA capping enzyme | 15 | 15 | mRNA [guanine-N(7)]-methyltransferase domain |

| 43 | 100 | NTPase | 30 | 30 | P-loop-containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolase, helicase, superfamily 3 |

| 44 | 101 | 70-kDa small subunit of early transcription initiation factor VETF | 30 | 30 | Helicase, C terminal; P-loop-containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolase |

| 45 | 103 | Carbonic anhydrase/virion | 15 | 15 | Alpha carbonic anhydrase |

| 46 | 104 | mutT motif/NTP PPH | 15 | 15 | NUDIX hydrolase, conserved site |

| 47 | 105 | mutT motif/NPH-PPH/RNA levels regulator | 15 | 15 | NUDIX hydrolase, conserved site |

| 48 | 106 | ATPase | 30 | 30 | Helicase, C terminal; P-loop-containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolase |

| 49 | 109 | Late gene transcription factor VLTF-2 | 30 | 30 | Zinc finger, MYM-type; poxvirus VLTF2, trans-activator |

| 50 | 110 | Late gene transcription factor VLTF-3 | 30 | 30 | VLTF3, late transcription factor subunit; VLTF3, zinc ribbon |

| 51 | 128 | DNA helicase | 15 | 15 | Helicase, superfamily 1/2, ATP-binding domain |

| 52 | 132 | Holliday junction resolvase/CPXV155 protein | 15 | 15 | RNase H-like domain |

| 53 | 134 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase | 75 | 75 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase domain (5) |

| 54 | 195 | Cowpox A-type inclusion protein | 120 | 68.5 | Viral A-type inclusion protein repeat (8) |

| 55 | 135 | P4c precursor/cowpox A-type inclusion protein | 30 | 26 | Armadillo-like helical, chordopoxvirus fusion domain |

| 56 | 143 | EEV membrane phosphoglycoprotein | 15 | 15 | C-type lectin fold |

| 57 | 144 | C-type lectin-like EEV protein | 15 | 15 | C-type lectin fold |

| 58 | 145 | CPXV171 protein | 15 | 11 | Chordopoxvirus A35R |

| 59 | 146 | IEV transmembrane phosphoprotein | 15 | 15 | Transmembrane domain |

| 60 | 148 | CD47-like putative membrane protein | 30 | 30 | CD47 transmembrane, CD47 immunoglobulin-like |

| 61 | 149 | Semaphorin-like protein | 15 | 9 | Semaphorin/CD100 antigen |

| 62 | 150 | C-type lectin-like type-II membrane protein | 15 | 6 | C-type lectin |

| 63 | 154 | Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase | 15 | 12.5 | 3-Beta hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/isomerase |

| 64 | 155 | Cu-Zn superoxide dismutase-like protein | 15 | 14.5 | Superoxide dismutase, copper/zinc binding domain |

| 65 | 160 | DNA ligase | 45 | 45 | DNA ligase, ATP-dependent, conserved site (3) |

| 66 | 163 | Secreted TNF receptor-like protein | 30 | 11 | TNFR/NGFR cysteine-rich region (2) |

| 67 | 164 | Kelch-like ring canal protein | 105 | 53.5 | BTB/POZ-like, BTB/Kelch-associated, Kelch repeat type 1 (5) |

| 68 | 165 | Hemagglutinin | 15 | 14 | Immunoglobulin V-set domain |

| 69 | 190 | Guanylate kinase-like protein | 15 | 3 | Guanylate kinase/L-type calcium channel |

| 70 | 167 | Schlafen/putative uncharacterized protein | 15 | 8 | ATPase, AAA-4 |

| 71 | 168 | Ankyrin-like protein | 120 | 120 | Ankyrin repeat (7), PRANC domain |

| 72 | 169 | Complement control/EEV membrane glycoprotein | 45 | 45 | Sushi/SCR/CCP (3) |

| 73 | 170 | Ankyrin-like protein | 15 | 13 | TMHMM transmembrane region |

| 74 | 172 | Gamma interferon receptor | 15 | 15 | Fibronectin, type III |

| 75 | 173 | 6-kDa intracellular viral protein | 30 | 15 | BTB/POZ-like, Kelch repeat type 1 |

| 76 | 220 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 75 | 20.5 | BTB/POZ-like, BTB/Kelch-associated, Kelch repeat type 1 (3) |

| 77 | 175 | Ser/Thr kinase-like protein | 15 | 10 | Protein kinase domain |

| 78 | 191 | IL-1β inhibitor | 45 | 26 | Immunoglobulin C-2 (3) |

| 79 | 179 | Ankyrin-like protein | 105 | 78.5 | Ankyrin repeat (6), PRANC domain |

| 80 | 180 | Immunoglobulin superfamily secreted glycoprotein | 30 | 30 | Immunoglobulin-like domain (2) |

| 81 | 181 | Ankyrin/putative uncharacterized protein | 90 | 72 | Ankyrin repeat (5), PRANC domain |

| 82 | 223 | Kelch-like/putative uncharacterized protein | 75 | 32 | Kelch repeat type 1 (3), BTB/POZ-like, BTB/Kelch associated |

| 83 | 224 | Ankyrin-like protein | 120 | 18.5 | Ankyrin repeat (7), PRANC domain |

| 84 | 257 | Crm-B secreted TNF-α-receptor-like protein | 60 | 13.5 | TNF receptor-II, C-terminal; TNFR/NGFR cysteine-rich region (3) |

| 85 | 258 | CrmE protein | 45 | 7.5 | TNFR/NGFR cysteine-rich region (3) |

| 86 | 183 | Ankyrin-like protein | 120 | 33 | Ankyrin repeat (7), PRANC domain |

| 87 | 184 | Ankyrin-like protein | 120 | 108 | Ankyrin repeat (7), PRANC domain |

| 88 | 185 | Crm-B secreted TNF-α-receptor-like protein | 45 | 40 | TNFR/NGFR cysteine-rich region (3) |

The genes are shown along the x axis of Fig. 10B. TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

Syntelog number; see Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Total number of motifs present if all genes in all isolates were intact.

Actual number of motifs present, given that some genes are truncated or fragmented.

If a motif is present in more than 1 copy per gene, the number of copies is shown in parentheses following the motif description.

DISCUSSION

The evolutionary history of orthopoxviruses is characterized by reductive evolution, SNPs, small indels, and possibly recombination, with most present-day viruses believed to contain a subset of the genomic sequence and genes that would have been present in the genus's ancestral virus (8). In this study, we identified and quantitated genomic remnants such as SNPs and indels left behind by evolutionary processes, which have led to gene truncation and fragmentation and eventual elimination. These processes have resulted in the current set of known orthopoxvirus virus species and isolates, each possessing their own unique gene complement, resulting in viruses with unique phenotypic properties, including host range and pathogenicity. To further test the hypothesis of reductive evolution, we constructed a complete genomic MSA for representative isolates of all orthopoxvirus species with an available complete genomic sequence. Analysis of the MSA demonstrated that no complete orthopoxvirus genome sequence to date contained sequence that is not already present in one of the three analyzed cowpox virus genomes, with the exception of the short interspersed element (SINE) found in TATV (43). Therefore, unlike the evolutionary history of the entire Poxviridae family, which is characterized by both gene acquisition and gene loss in addition to adaptive mutations (16), the evolutionary history of the Orthopoxvirus genus is characterized by gene loss events and amino acid changes in response to changes in selection pressures.

Analysis of the number of variants (SNPs and indels) present in orthopoxvirus genomes demonstrated that isolates with the shortest genomes that contained the highest number of deleted genes also contained the highest number of deteriorating genes, as well as the highest concentration of ESMs (Fig. 9A and B). These changes may result from an alteration in the selection pressures impacting virus replication due to changes in its environment, leading to the progressive loss of gene function through gene truncation and fragmentation, and eventually gene removal. We can observe the remnants of this process in the gene fragmentation patterns and in the ESMs identified as a result of this study. Our results suggest that many orthopoxviruses continue to exhibit sequence changes resulting in gene truncation, fragmentation, and deletion that may be a response to a continual process of adaptation to new environments through the loss of protein function. A protein exhibiting loss of function due to truncation or fragmentation may not simply be nonessential for virus replication in a new environment but actually be deleterious to virus growth and spread. If this is the case, truncated and fragmented genes continue to be selected against and eventually removed completely from the genome in order to ensure complete abrogation of protein activity. This is reflected in the large number of ESMs that accumulate in the ORFs of progressively shorter genomes (Fig. 7 and 9). The concentration and location of ESMs within a gene may also provide temporal clues concerning the loss of selection pressure within any particular evolutionary lineage, since the mutation rate in the absence of selection pressure approaches the error rate of the viral DNA polymerase (59).

Orthopoxviruses are capable of gene expansion as well as gene deletion, as demonstrated by Elde and colleagues (21). Vaccinia viruses were able to duplicate the K3L gene when put under selective pressure favoring K3L expression, most likely through recombination. These authors also witnessed loss of the duplications when the selective pressure was removed, suggesting a fitness cost to the viruses for carrying the extra genes. Future studies similar to those of Elde et al. using a range of selection pressures that impact a variety of genes may provide additional understanding of the mechanism involved in enabling poxviruses to adapt to changing environments.

While our analyses identified genes and gene remnants that would produce a truncated protein or protein fragment, we are not able to predict which of these genes may still be transcribed and translated as well as retain function. In the past decade, gene expression profiles for orthopoxviruses have been determined using tiling microarrays (60, 61) and RNA sequencing (62). From these studies, it is apparent that many of the genes that we have identified as truncated or fragmented are being transcribed into mRNA. Promoters often remain whole or minimally degraded in genes that are in the early stages of truncation and fragmentation. Nevertheless, transcription of these messages does not imply that these genes are being expressed as proteins, and even if expressed, the proteins may not be functional. In the future, it will be important to more fully understand the functional role that these nonintact genes play in the biology of particular virus species (especially in host range and pathogenesis) by exploring their activity in both in vivo and in vitro experimental systems.

Our analysis of the nucleotide changes that lead to changes in gene content and therefore in host range and pathogenesis represents an important step toward better understanding the evolutionary history of orthopoxviruses and the mechanisms driving their evolution. Here, we have shown that the smallest orthopoxvirus genomes not only have lost the greatest number of genes due to large deletions but also contain the greatest number of genes that are still in the process of being lost through truncation and fragmentation due to the accumulation of SNPs and small indels. A similar evolutionary mechanism is often observed in symbiotic and obligate parasitic bacteria, which have a reduced genome size compared to free-living bacteria. Sequences rendered nonfunctional due to the accumulation of mutations following decreased or negative selection pressure for protein function may be removed from the genome to reduce the burden of replicating nonfunctional DNA (63). The decrease in genome size of some poxviruses such as variola virus, ectromelia virus, and molluscum contagiosum virus has been hypothesized to be an important mechanism of adaptation toward a narrower host range (19, 20, 64, 65). Genes required for replication within a particular host are maintained, perhaps with minor modifications most suited to that particular host, while genes required for replication in alternative hosts are inactivated and removed. It is possible that for some viruses, restricted to replication in one or a very few hosts, an evolutionary “dead end” is established due to the removal of genes resulting from their increasingly limited host range (e.g., variola virus), while other viruses with a broader host range (e.g., cowpox viruses) maintain a larger complement of genes to support their replication in a wider, more diverse environment. Limiting the host range selects for more-limited gene sets that are produced as a consequence of sequence replication errors; however, evidence for recombination in closely related orthopoxviruses has been observed and could result in increased genetic diversity and escape from such a “dead end” (20, 51, 66–69). Our comprehensive analysis of the genomic variation and changes leading to gene content diversity was able to detect some of the remnants of these evolutionary processes still present in orthopoxvirus genomes and suggests that these viruses are under continual adaptation due to changes in their environment. Future work should help to better define the evolutionary potential of modern-day Orthopoxvirus species and the chance that viruses that have not entered an evolutionary “dead end” may evolve to produce novel host-specific pathogens.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH/NIAID grant no. U01AI48706 and NIH/NIAID contract no. HHSN266200400036C to E.J.L. and NIH/NCATS grant no. UL1TR000165 to the UAB Center for Clinical and Translational Science.

We thank Don Dempsey, Mary Odom, and John Osborne for their contributions to various aspects of this work.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 17 September 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02015-14.

REFERENCES

- 1. Knipe DM, Howley PM, Cohen JL, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B. (ed). 2013. Fields virology, 6th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 2. McFadden G. 2005. Poxvirus tropism. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:201–213. 10.1038/nrmicro1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lantto J, Haahr Hansen M, Rasmussen SK, Steinaa L, Poulsen TR, Duggan J, Dennis M, Naylor I, Easterbrook L, Bregenholt S, Haurum J, Jensen A. 2011. Capturing the natural diversity of the human antibody response against vaccinia virus. J. Virol. 85:1820–1833. 10.1128/JVI.02127-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. Bioterrorism agents/diseases. http://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/agentlist-category.asp.

- 5. Kim JW, Gulley JL. 2012. Poxviral vectors for cancer immunotherapy. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 12:463–478. 10.1517/14712598.2012.668516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moussatche N, Damaso CR, McFadden G. 2008. When good vaccines go wild: feral orthopoxvirus in developing countries and beyond. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2:156–173. 10.3855/jidc.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reynolds MG, Carroll DS, Karem KL. 2012. Factors affecting the likelihood of monkeypox's emergence and spread in the post-smallpox era. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2:335–343. 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hendrickson RC, Wang C, Hatcher EL, Lefkowitz EJ. 2010. Orthopoxvirus genome evolution: the role of gene loss. Viruses 2:1933–1967. 10.3390/v2091933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stanford MM, McFadden G, Karupiah G, Chaudhri G. 2007. Immunopathogenesis of poxvirus infections: forecasting the impending storm. Immunol. Cell Biol. 85:93–102. 10.1038/sj.icb.7100033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Johnston JB, McFadden G. 2004. Technical knockout: understanding poxvirus pathogenesis by selectively deleting viral immunomodulatory genes. Cell. Microbiol. 6:695–705. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Smith GL. 2007. Genus Orthopoxvirus: Vaccinia virus, p 1–45 In Mercer AA, Weber O, Schmidt A. (ed), Poxviruses. Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 12.International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. 2011. Virus taxonomy: classification and nomenclature of viruses: ninth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier Academic Press, London, England. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mark RBL, Fenner F. 2007. Mousepox, p 67–92 In Fox JG, Barthold SW, Davisson MT, Newcomer CE, Quimby FW, Smith AL. (ed), The mouse in biomedical research diseases, 2nd ed. Elsevier Academic Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Essbauer S, Pfeffer M, Meyer H. 2010. Zoonotic poxviruses. Vet. Microbiol. 140:229–236. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sergei Shchelkunov SM, Richard Moyer 2005. Orthopoxviruses pathogenic for humans. Springer Science+Business Media, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Odom MR, Hendrickson RC, Lefkowitz EJ. 2009. Poxvirus protein evolution: family wide assessment of possible horizontal gene transfer events. Virus Res. 144:233–249. 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hansen H, Okeke MI, Nilssen O, Traavik T. 2004. Recombinant viruses obtained from co-infection in vitro with a live vaccinia-vectored influenza vaccine and a naturally occurring cowpox virus display different plaque phenotypes and loss of the transgene. Vaccine 23:499–506. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McLysaght A, Baldi PF, Gaut BS. 2003. Extensive gene gain associated with adaptive evolution of poxviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:15655–15660. 10.1073/pnas.2136653100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bratke KA, McLysaght A, Rothenburg S. 2013. A survey of host range genes in poxvirus genomes. Infect. Genet. Evol. 14:406–425. 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Esposito JJ, Sammons SA, Frace AM, Osborne JD, Olsen-Rasmussen M, Zhang M, Govil D, Damon IK, Kline R, Laker M, Li Y, Smith GL, Meyer H, Leduc JW, Wohlhueter RM. 2006. Genome sequence diversity and clues to the evolution of variola (smallpox) virus. Science 313:807–812. 10.1126/science.1125134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Elde NC, Child SJ, Eickbush MT, Kitzman JO, Rogers KS, Shendure J, Geballe AP, Malik HS. 2012. Poxviruses deploy genomic accordions to adapt rapidly against host antiviral defenses. Cell 150:831–841. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lefkowitz EJ, Upton C, Changayil SS, Buck C, Traktman P, Buller RM. 2005. Poxvirus Bioinformatics Resource Center: a comprehensive Poxviridae informational and analytical resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:D311–D316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403–410. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Salzberg SL, Delcher AL, Kasif S, White O. 1998. Microbial gene identification using interpolated Markov models. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:544–548. 10.1093/nar/26.2.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bratke KA, McLysaght A. 2008. Identification of multiple independent horizontal gene transfers into poxviruses using a comparative genomics approach. BMC Evol. Biol. 8:67. 10.1186/1471-2148-8-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]