ABSTRACT

Cavally virus (CavV) and related viruses in the family Mesoniviridae diverged profoundly from other nidovirus lineages but largely retained the characteristic set of replicative enzymes conserved in the Coronaviridae and Roniviridae. The expression of these enzymes in virus-infected cells requires the extensive proteolytic processing of two large replicase polyproteins, pp1a and pp1ab, by the viral 3C-like protease (3CLpro). Here, we show that CavV 3CLpro autoproteolytic cleavage occurs at two N-terminal (N1 and N2) and one C-terminal (C1) processing site(s). The mature form of 3CLpro was revealed to be a 314-residue protein produced by cleavage at FKNK1386|SAAS (N2) and YYNQ1700|SATI (C1). Site-directed mutagenesis data suggest that the mesonivirus 3CLpro employs a catalytic Cys-His dyad comprised of CavV pp1a/pp1ab residues Cys-1539 and His-1434. The study further suggests that mesonivirus 3CLpro substrate specificities differ from those of related nidovirus proteases. The presence of Gln (or Glu) at the P1 position was not required for cleavage, although residues that control Gln/Glu specificity in related viral proteases are retained in the CavV 3CLpro sequence. Asn at the P2 position was identified as a key determinant for mesonivirus 3CLpro substrate specificity. Other positions, including P4 and P1′, each are occupied by structurally related amino acids, indicating a supportive role in substrate binding. Together, the data identify a new subgroup of nidovirus main proteases and support previous conclusions on phylogenetic relationships between the main nidovirus lineages.

IMPORTANCE Mesoniviruses have been suggested to provide an evolutionary link between nidovirus lineages with small (13 to 16 kb) and large (26 to 32 kb) RNA genome sizes, and it has been proposed that a specific set of enzymes, including a proofreading exoribonuclease and other replicase gene-encoded proteins, play a key role in the major genome expansion leading to the currently known lineages of large nidoviruses. Despite their smaller genome size (20 kb), mesoniviruses retained most of the replicative domains conserved in large nidoviruses; thus, they are considered interesting models for studying possible key events in the evolution of RNA genomes of exceptional size and complexity. Our study provides the first characterization of a mesonivirus replicase gene-encoded nonstructural protein. The data confirm and extend previous phylogenetic studies of mesoniviruses and related viruses and pave the way for studies into the formation of the mesonivirus replication complex and functional and structural studies of its functional subunits.

INTRODUCTION

Nidovirales (families Coronaviridae, Roniviridae, Mesoniviridae, and Arteriviridae) are positive-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses that infect a wide range of vertebrate and invertebrate hosts (1–7). Members of the family Mesoniviridae replicate in mosquitoes (2, 8, 9). Cavally virus (CavV) and Nam Dinh virus (NDiV) were the first mesoniviruses to be characterized (8, 9). The two viruses are closely related and belong to the same species, Alphamesonivirus 1, the prototype species of the genus Alphamesonivirus (family Mesoniviridae) (2). Other phylogenetically diverse mesoniviruses were identified in recent studies of viruses isolated from a range of mosquito species and geographic locations. The latter remain to be assigned to existing and yet-to-be-established taxa within the family Mesoniviridae (2, 10–12). Mesoniviruses have medium-sized genomes of approximately 20 kb and have been proposed to provide an evolutionary link between small (13 to 16 kb) and large (26 to 32 kb) nidoviruses (2, 8, 9, 11, 13). Therefore, the further characterization of mesonivirus biology is expected to provide insight into possible factors and/or mechanisms involved in the evolution of large-sized RNA genomes (14). In this context, we decided to embark on a systematic analysis of the mesonivirus replication/transcription complex and, in this first study, characterized the putative CavV 3C-like protease (3CLpro) (9, 11).

While coronavirus and arterivirus homologs of the predicted mesonivirus 3CLpro have been studied quite extensively (reviewed in references 7, 15, and 16), there is limited information on related proteases from other nidovirus lineages (17–19). Nidovirus 3CLpros cleave the pp1a/pp1ab precursor polyproteins at multiple processing sites in the central and C-proximal regions and thereby release the key components of the viral replication/transcription complex. Because of their central role in polyprotein processing, nidovirus 3CLpros also are referred to as main proteases (Mpro) (16, 20). Nidovirus 3CLpros share an N-terminal chymotrypsin-like two-β-barrel fold structure that is linked to a C-terminal domain whose size and structure varies among different nidovirus lineages. Ser or Cys (nucleophile) and His (general base) are used as catalytic residues (20–25). There is a remarkable degree of variability between the catalytic systems employed by 3CLpros from different nidovirus lineages. For example, arteriviruses, bafiniviruses, and toroviruses use, as the active-site nucleophile, a Ser residue which is part of a catalytic triad or dyad (Ser-His-Asp or Ser-His) (17, 18, 24, 25). In contrast, coronavirus and ronivirus 3C-like proteases employ a catalytic Cys-His dyad (19, 26–28). All previously characterized nidovirus 3C-like proteases have a partially conserved substrate specificity, with Gln or Glu occupying the P1 position and a small residue (e.g., Ser, Ala, or Gly) occupying the P1′ position in nearly all cleavage sites (the nomenclature of residues flanking the scissile bond, according to reference 29, is … P3-P2-P1|P1′-P2′-P3′ …). Substrate recognition at the P1 position is partially determined by a conserved His residue in the S1 subsite (16, 20, 25, 30).

In previous studies, we identified putative 3CLpro homologs in the replicase polyproteins of CavV and other mesoniviruses (9, 11). With respect to the enzyme's substrate specificity, we and others failed to identify conserved (Gln/Glu)|(Ser/Ala/Gly) dipeptide sequences at interdomain borders in mesonivirus polyproteins, indicating distinct substrate preferences for mesonivirus 3CLpros (8, 9, 11). The data obtained in the present study confirm and extend these earlier predictions. We were able to show that the fully processed form of the CavV 3CLpro is a 314-residue Cys protease that is released from pp1a/pp1ab by cleavage at partially conserved sites that share an Asn residue at the P2 position and Ser at the P1′ position, while (in contrast to all other nidovirus homologs studied so far) the P1 residue is not conserved. The data further suggest that CavV 3CLpro employs a Cys-His catalytic dyad embedded in a (predicted) two-β-barrel N-terminal domain that is linked to a large α+β C-terminal domain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and virus.

Aedes albopictus clone C6/36 cells (ATCC CRL-1660) were grown at 27°C in Leibovitz's L-15 medium (Gibco, Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (9). Prior to inoculation with Cavally virus (CavV) isolate C79, confluent C6/36 cells were washed with unsupplemented Leibovitz's L-15 medium. Forty-eight h postinfection (p.i.), the virus-containing cell culture supernatant was collected, centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and then stored in small aliquots at −80°C until further use.

Construction of plasmids.

Total RNA was prepared from CavV-infected C6/36 cells (Qiagen RNeasy kit) and reverse transcribed (Superscript III; Invitrogen) using the CavV-specific reverse primer LT-5. Cloning and mutagenesis of plasmid constructs was done by using an in vivo recombination method (31). A list of oligonucleotides used for PCR amplification or mutagenesis is available upon request. To generate pMAL-c2-[pp1a-1343-1720-His6], the coding sequence of the putative 3CLpro domain with flanking sequences (CavV pp1a/1ab amino acid residues Ala-1343 to Asp-1720) was amplified by PCR from cDNA using oligonucleotides LT-1 and LT-2. In a second PCR, the pMAL-c2 (New England BioLabs) backbone was amplified from pMAL-c2 plasmid DNA using oligonucleotides LT-3 and LT-4. Subsequently, the reaction mixture was digested with DpnI (Life Technologies) to remove any remaining (methylated) pMAL-c2 template DNA. The amplicons from both PCRs were combined and used to transform Escherichia coli Top10F′ cells. E. coli clones containing the desired recombinant plasmid DNA were identified by restriction and sequence analysis. pMAL-c2-[pp1a-1343-1720-His6]-derived constructs were generated by PCR-based methods using suitable primers and in vivo recombination. To construct pET-11d-[pp1a-1374-1699-His7], the CavV pp1a 1374-1699 coding sequence was amplified from pMAL-c2-[pp1a-1343-1720-His6] using primers LT-11 and LT-12. The resulting PCR products were digested with BamHI and BspHI, and pET-11d plasmid DNA (Novagen) was digested with BamHI and NcoI. Digested PCR products and plasmid DNA then were ligated using T4 DNA ligase.

Bacterial expression and cell lysis.

To express recombinant proteins encoded by pMAL-c2-derived constructs, the E. coli strain TB1 was used. Freshly transformed cells were grown in LB medium containing 75 μg/ml carbenicillin until an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6 to 0.9 was reached. The culture then was divided and protein expression was induced in one of the cultures with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Induced and noninduced cultures were incubated at 18°C under vigorous shaking (225 rpm) for another 4 h. Following centrifugation, bacterial pellets were stored at −20°C until further use. To express the pET-11d-[pp1a-1374-1699-His7]-encoded protein, the E. coli BL21(DE3) strain was used. In this case, protein expression was induced for 4 h at 25°C. Protein expression was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and/or Western blotting using total cell lysates solubilized in Laemmli sample buffer and incubated at 95°C for 5 min. For protein purification, the frozen cell pellets (obtained from a 250- to 500-ml culture) were resuspended on ice in 25 ml of the appropriate binding buffer containing 0.1 mg/ml lysozyme (Roche) and then disrupted by sonication as described previously (18). Soluble proteins were isolated by centrifugation (20,000 rpm, 4°C, 30 min; FiberLite F21-8x50y; Thermo Scientific) and filtration (0.45-μm pore size).

GST affinity purification.

Glutathione S-transferase (GST)-containing processing products derived from MBP-pp1a-1343-1720-GST were purified at 4°C using an ÄktaPrime plus chromatography system (GE Healthcare) equipped with a 1-ml GST HisTrap HP column. To do this, the cells were lysed in PBS (140 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.3), and the cleared and filtered lysate was loaded onto the column using a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. After thorough washing with PBS, the bound processing products were eluted in buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl and 10 mM glutathione (pH 8.0), and 1-ml fractions were collected.

Immobilized metal ion affinity chromatography (IMAC).

MBP-pp1a-1343-1699-AGSSG-His7-derived processing products and pp1a-1374-1699-His7, were purified at 4°C using an ÄktaPrime plus chromatography system (GE Healthcare) equipped with a 1-ml Ni2+-charged HiTrap chelating HP column (GE Healthcare). Cells were lysed in buffer A (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 10% [vol/vol] glycerol, 10 mM 3-mercapto-1,2-propanediol [thioglycerol]) and loaded onto the column at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Following extensive washing with buffer A, the bound proteins were eluted in 1-ml fractions using a 30-ml linear gradient from 0% buffer A to 100% buffer B (buffer A containing 400 mM imidazole).

N-terminal sequencing of proteolytic processing products.

To determine the N terminus of affinity-purified C-terminal autoprocessing product(s), the appropriate protein samples were separated in a discontinuous 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Carl Roth). The membrane was stained with 0.025% Coomassie blue R-250 in 40% methanol and subsequently destained using 50% methanol. The area containing the desired protein was excised, and the protein was subjected to N-terminal sequencing by Edman degradation (Biochemical Institute, University of Giessen, Germany).

Expression and purification of CavV 3CLpro marker proteins.

To facilitate the identification of differentially processed forms of CavV 3CLpro by comigration with marker proteins in SDS-polyacrylamide gels, two proteolytically inactive marker proteins with defined N- and C-terminal ends were expressed and purified. The proteins MBP-pp1a-1377-1700_H1434A_C1539A (3CLpro N1-C1) and MBP-pp1a-1387-1700_H1434A_C1539A (3CLpro N2-C1) were expressed in E. coli TB1 cells (described above) at 25°C for 5 h. Cell pellets obtained from 500-ml expression cultures were suspended on ice in MBP purification buffer (20 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM thioglycerol) and lysed as described above. MBP-3CLpro fusion proteins were purified using 2 ml of amylose resin (NEB). After binding and extensive washing using MBP purification buffer, the proteins were eluted in the same buffer supplemented with 10 mM maltose. Fractions containing the desired protein were pooled and subjected to a buffer exchange using Xa cleavage buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2) and a PD-10 desalting column (GE Healthcare). The MBP tag then was cleaved off from the fusion protein(s) by overnight incubation with factor Xa (NEB) at 4°C and subsequently removed by anion exchange chromatography. To this end, a buffer exchange was performed using anion exchange binding buffer (25 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM thioglycerol), and the proteins were separated by using an ÄktaPrime plus chromatography system equipped with a 1-ml HiTrap Q-HP column. Under these conditions, the 3CLpro marker proteins did not bind to the column, while MBP and minor contaminants were retained (and eluted at increased NaCl concentrations). Aliquots of the purified 3CLpro N1-C1 and N2-C1 marker proteins were stored at −80°C.

CavV 3CLpro antiserum.

The coding sequence of CavV pp1a/pp1ab residues Met-1374 to Asn-1699, containing a short sequence upstream of 3CLpro, the entire 3CLpro domain without the C-terminal Gln-1700 residue, and a C-terminal heptahistidine (His7) tag, was inserted into pET-11d plasmid DNA (Novagen) and expressed in E. coli. The 3CLpro-containing, C-terminally His7-tagged cleavage product released from the pp1a-1374-1699-His7 fusion protein was purified by Ni2+-IMAC using the protocol described above. The purity and identity of the purified protein was assessed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using a His tag-specific monoclonal antibody (Novagen). The purified protein was dialyzed against storage buffer (20 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 200 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT), concentrated using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter units (Millipore), and used to raise a CavV 3CLpro-specific antiserum in rabbits (Eurogentec).

Detection of CavV 3CLpro in infected cells.

At 48 h p.i., CavV-infected C6/36 cells were scraped off, washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and centrifuged at low speed. The cell pellet was resuspended in NP-40 buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40) and incubated on ice for 30 min. Following centrifugation, the soluble supernatant was collected and total protein concentration determined using the Bradford protein assay. Seventy-five μg of the protein extract was mixed with Laemmli sample buffer, heat denatured, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. 3CLpro was detected by immunoblotting using the CavV 3CLpro-specific rabbit antiserum described above and IRDye 800CW-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (LI-COR Biosciences).

RESULTS

CavV 3CLpro autoprocessing activity.

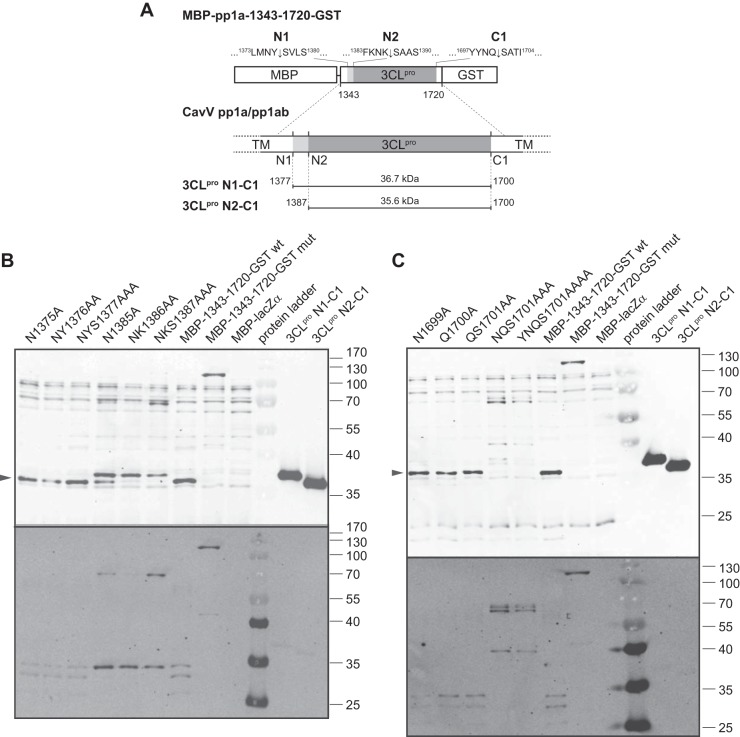

In a previous study, we identified by comparative sequence analysis a putative 3CLpro domain in the ORF1a-encoded part of the CavV replicase polyproteins pp1a and pp1ab (9). We also identified putative active-site residues, including a GxCG (the presumed active-site Cys is underlined) motif that, based on its conservation in many viral 3C and 3C-like proteases (30) as well as its position and structural context in the protease domain, was predicted to contain the CavV 3CLpro active-site nucleophile Cys-1539. To corroborate these predictions, we expressed the presumed 3CLpro domain together with flanking pp1a/pp1ab sequences (Ala-1343 to Asp-1720) in E. coli. The CavV sequence was expressed as a fusion with an N-terminal MBP and a C-terminal hexahistidine (His6) tag. As a control, we expressed a mutant form of this protein in which the putative catalytic Cys-1539 residue was replaced with Ala (Fig. 1A). The predicted size of the MBP-pp1a-1343-1720-His6 (3CLpro wild type [wt]) and MBP-pp1a-1343-1720_C1539A-His6 (3CLpro mutant [mut]) proteins was approximately 86 kDa. As a second control, we expressed the MBP-lacZα fusion protein encoded by the (empty) pMAL-c2 plasmid. The total molecular mass of this fusion protein is 51 kDa, of which 42 kDa is contributed by the MBP sequence (including an Asn-rich spacer region and factor Xa cleavage site). When the expression of the 3CLpro wt construct was induced, we observed two additional proteins of about 40 and 37 kDa, respectively, in the Coomassie-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel. These proteins were not detected in the controls (MBP-lacZα, 3CLpro mut, and noninduced cells) (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the induction of the expression of the MBP-3CLpro mut protein gave rise to only one overexpressed protein that migrated right in the middle between the 70- and 100-kDa size markers, in line with the expected size of 86 kDa for the unprocessed MBP-3CLpro fusion protein (Fig. 1B). Together, these data suggest that the MBP-3CLpro wild-type construct had the predicted proteolytic activity, and the activity was abolished when the presumed active-site nucleophile, Cys-1539, was replaced with Ala. In a subsequent Western blot experiment using an MBP-specific monoclonal antibody (Fig. 1C), we confirmed the identities of the overexpressed MBP-lacZα and MBP-3CLpro mut fusion proteins observed in the SDS-polyacrylamide gel (Fig. 1B) and identified a major MBP-containing processing product of slightly more than 40 kDa in cells expressing the MBP-3CLpro wt protein. Both the size and immune reactivity of this ∼40-kDa protein suggest that it represents the N-terminal processing product of a 3CLpro-mediated cleavage reaction occurring between the N-terminal MBP and C-terminal 3CLpro sequences (Fig. 1C). Using a hexahistidine tag-specific antibody, we failed to detect any C-terminal processing products (data not shown), suggesting that another cleavage event close to the carboxyl terminus of the MBP-3CLpro wt protein had occurred. Due to its small size, this C-terminal product might have escaped detection in our gel system, a hypothesis that could be confirmed in subsequent experiments (see below). Taken together, the data suggest that CavV pp1a/pp1ab residues 1343 to 1720 harbor an active cysteine protease that undergoes autoprocessing at both N- and C-terminal cleavage sites.

FIG 1.

Autocatalytic release of the putative CavV 3CLpro domain from flanking sequences and determination of the C-terminal 3CLpro autoprocessing site. (A) Schematic representation of CavV pp1a/1ab replicase polyproteins and fusion protein constructs used in this experiment. The putative 3CLpro domain is indicated in dark gray, and transmembrane domains are shown in light gray. 3CLpro mut, putative 3CLpro domain containing a Cys-1539-to-Ala change in the expressed sequence. (B and C) Expression analysis of the MBP-pp1a-1343-1720-His6 (wt) and MBP-pp1a-1343-1720_C1539A-His6 (mut) fusion proteins. Expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG for 4 h at 18°C. Cell lysates obtained from IPTG-induced and noninduced cells were analyzed in a 14% SDS-polyacrylamide gel (B) or by Western blotting using an MBP-specific monoclonal antibody. The products of the expression control pMAL-c2 (MBP-lacZα) and the mutant form of the MBP-3CLpro fusion protein (3CLpro mut) are indicated to the left. Two putative processing products derived from the MBP-3CLpro wt construct are indicated by filled circles. Molecular masses (in kDa) of prestained marker proteins are indicated to the right. (D) Purification of C-terminal (GST-containing) cleavage products produced by 3CLpro-mediated cleavage of the MBP-pp1a-1343-1720-GST fusion protein by glutathione Sepharose chromatography. GST-containing cleavage products eluted in fraction 4 (F4) were subjected to N-terminal sequence analysis by Edman degradation. All three cleavage products were shown to have the N terminus Ser-Ala-Thr-…, suggesting that cleavage occurred at 1700Q|S1701 in the CavV pp1a/pp1ab sequence. Molecular masses (in kDa) of marker proteins are indicated to the left. SF, soluble protein fraction; IF, insoluble fraction; FT, column flowthrough fraction; W, wash fraction; F3 to F6, elution fractions 3 to 6.

Determination of C- and N-terminal CavV 3CLpro autoprocessing sites.

To gain insight into the CavV 3CLpro substrate specificity and determine the position of the cleavage sites in the CavV pp1a/1ab polyproteins, we purified the appropriate autoprocessing products and analyzed their amino termini by Edman degradation. As described above, we were unable to detect a C-terminal processing product released from the MBP-pp1a-1343-1720-His6 fusion protein, most probably due to the small size of this protein. In the CavV pp1a/pp1ab sequence, the 3CLpro domain is flanked at its carboxyl terminus by extended hydrophobic sequences that, by analogy with other nidoviruses, are predicted to act as multiple membrane-spanning protein domains. In previous studies, related hydrophobic regions from coronaviruses proved to be toxic or tended to aggregate when expressed in bacterial or in vitro systems (32–34). To resolve this technical problem, we decided to replace the short His-tagged C-terminal region present in our original construct with a GST domain. We reasoned that a potential cleavage at the C-terminal site could be characterized by glutathione affinity purification of a larger (GST-containing) processing product and subsequent N-terminal sequence analysis. As anticipated, C-terminal cleavage products could be purified from E. coli cells expressing the MBP-pp1a-1343-1720-GST fusion protein. Surprisingly, however, we detected three (rather than just one) protein(s) in the elution fractions (Fig. 1D). All three processing products could be specifically stained using a GST-specific antibody (data not shown), confirming their identities but indicating the presence of additional 3CLpro cleavage sites in the N- or C-terminal GST region (or unspecific degradation). To address these possibilities, we determined the amino termini of all three processing products by 5 to 10 cycles of Edman degradation and found that all three processing products contained the same sequence, 1701SATIF…, at their N termini. This leads us to conclude that, in all cases, C-terminal 3CLpro cleavage had occurred at DYYNQ1700|SATIF in the CavV pp1a/pp1ab sequence, and the different sizes of the three processing products probably result from additional processing events in the C-terminal GST region.

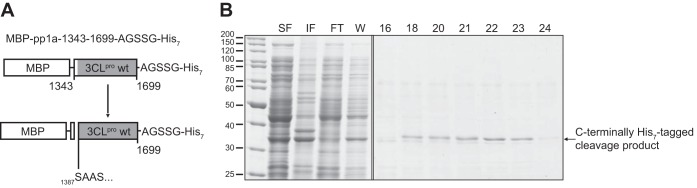

We next sought to determine the N-terminal cleavage site of CavV 3CLpro. Given that nidovirus main proteases have a pronounced preference for Gln (or Glu) at the substrate's P1 position (16), we attempted to abolish cleavage at the C-terminal CavV 3CLpro processing site by replacing the P1-Gln residue with Ala. Incomplete (or no) cleavage of the resulting protein, MBP-pp1a-1343-1720_Q1700A-GST, at the C-terminal 3CLpro cleavage site was expected to produce a 3CLpro-GST processing intermediate that could be purified by glutathione affinity chromatography; thus, it could be suitable for sequence analysis of the 3CLpro amino terminus. Surprisingly, however, expression of the MBP-pp1a-1343-1720_Q1700A-GST protein revealed that C-terminal cleavage occurred nearly as efficiently as in the wild-type construct (data not shown), indicating that the P1-Gln residue is dispensable for cleavage by CavV 3CLpro. In another attempt to abolish cleavage at the 3CLpro carboxyl terminus, we removed the entire C terminus from the MBP-pp1a-1343-1720 fusion protein construct, including P1-Gln and all residues downstream of the scissile bond, and replaced this sequence with a short linker and a heptahistidine tag (MBP-pp1a-1343-1699-AGSSG-His7). Expression in E. coli and purification of His7 tag-containing proteins by Ni2+ IMAC resulted in a 37-kDa protein species. The protein(s) eluted as two peak fractions (8 to 13 and 18 to 23) from the column (Fig. 2B and data not shown). Western blot analysis showed that only the 37-kDa protein eluting at higher imidazole concentrations in fractions 18 to 23 was detected by a His tag-specific antibody (data not shown). The amino terminus of this His7-containing cleavage product (fraction 22) (Fig. 2B) was sequenced by Edman degradation. The data provided conclusive evidence that CavV 3CLpro N-terminal cleavage had occurred between Lys-1386 and Ser-1387 within the sequence context FKNK1386|SAAS.

FIG 2.

Determination of the N-terminal 3CLpro autoprocessing site. (A) Schematic representation of the protein construct used in this experiment. The construct lacked the C-terminal 3CLpro residue (Gln-1700) and contained a short C-terminal linker sequence, including a heptahistidine (His7) tag. (B) Purification by Ni-IMAC of C-terminally His7-tagged processing products derived from 3CLpro-mediated cleavage of the fusion protein construct. N-terminal sequence analysis of the protein present in fraction 22 revealed the sequence Ser-Ala-Ala-…, suggesting that cleavage occurred at 1386K|S1387 in the CavV pp1a/pp1ab sequence. Molecular masses (in kDa) of marker proteins are indicated to the left. SF, soluble protein fraction; IF, insoluble protein fraction; FT, column flowthrough fraction; W, wash fraction; 16 to 24, elution fractions.

Subsequently, we also characterized the purified protein eluting in fractions 8 to 13. This protein was about 1 kDa smaller in size than the protein that eluted in fractions 18 to 23. Both this size difference and the apparent absence of a C-terminal His7 tag (see above) suggested that, under the experimental conditions used in this experiment, the 3CLpro domain retained residual activity at the genetically modified C-terminal cleavage site, YYN1699AGSSGHHHHHHH (CavV 3CLpro sequence underlined), which might have caused a partial loss of the His7 tag during purification. N-terminal sequencing of the 37-kDa protein present in fraction 10 revealed an amino terminus that was identical to that of the His7-containing cleavage product present in fraction 23, confirming that, in both cases, the N-terminal processing of 3CLpro had occurred between residues Lys-1386 and Ser-1387. The data also show that despite the replacement of the P1-Gln and the entire P′ region (…NQ|SATI→…NAGSSG…), the 3CLpro domain retained residual autoprocessing activity at the C terminus.

Taken together, the data obtained in bacterial expression systems identified FKNK1386|SAAS as the N-terminal and YYNQ1700|SATI as the C-terminal CavV 3CLpro cleavage sites. The apparent lack of a conserved P1-Gln/Glu residue and (partial or complete) retention of 3CLpro cleavage activity at the C-terminal cleavage site with a Gln-to-Ala alteration at the P1 position indicate that, unlike the situation in other nidovirus main proteases, the P1 residue plays a less critical role in substrate recognition.

Mutation analysis of CavV 3CLpro autoprocessing sites.

To gain more insight into the specific substrate requirements for efficient cleavage by the CavV 3CLpro, we performed mutation analyses of the N- and C-terminal autoprocessing sites. The study also included another N-proximal 3CLpro cleavage site that we had identified in the course of our study by trans-cleavage assays using large bacterial fusion protein constructs containing wild-type or mutant forms of the CavV 3CLpro (data not shown). This additional cleavage site, LMNY1376|SVLS, was found to be located 10 amino acid (aa) residues upstream of the N-terminal 3CLpro autoprocessing site described above (FKNK1386|SAAS). According to their positions in the pp1a/pp1ab sequence, we named the two N-terminal 3CLpro processing sites N1 (for the Y1376|S site) and N2 (for the K1386|S site). We considered it possible that the CavV 3CLpro uses alternative N-terminal cleavage sites to release itself from larger precursors, depending on whether the 3CLpro release occurred by intermolecular (trans) or intramolecular (cis) cleavage. A similar scenario has been discussed previously for the WBV main protease (18).

To investigate possible effects of substitutions of single or multiple residues at the various cleavage sites, we expressed the MBP-pp1a-1343-1720-GST fusion protein and a series of mutant derivatives containing appropriate amino acid substitutions in E. coli and studied the proteolytic processing of these proteins by Western blotting using CavV 3CLpro- and GST-specific antibodies (Fig. 3). To discriminate between processing products resulting from N-terminal cleavage at the N1 and/or N2 site(s), we used two bacterially expressed proteins as size markers (see Materials and Methods). One of the proteins corresponded to the CavV 3CLpro domain cleaved at the first N-terminal (N1) site and the C-terminal cleavage site, Q1700|S (C1). This protein was comprised of pp1a/pp1ab residues 1377 to 1700 and was called 3CLpro N1-C1 (Fig. 3A). The other marker protein corresponded to a processing product cleaved at the second N-terminal (N2) site that we had confirmed to be the N-terminal 3CLpro autoprocessing site in our cis cleavage assays (described above) and the C1 site. The latter protein encompassed pp1a/pp1ab residues 1387 to 1700 and was called 3CLpro N2-C1 (Fig. 3A).

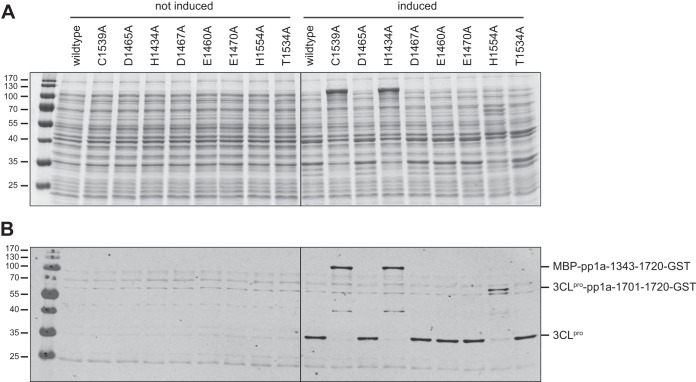

FIG 3.

Mutation analysis of N- and C-terminal CavV 3CLpro autoprocessing sites. (A) Schematic representation of the fusion protein constructs used to study effects of amino acid substitutions at one of the N-terminal (N1 and N2) or the C-terminal (C1) cleavage site. Positions and sequences of individual cleavage sites are indicated, and calculated molecular masses of processing products are given. TM, transmembrane domains. (B and C) Expression and proteolytic processing of MBP-pp1a-1343-1720-GST-derived proteins containing single or multiple Ala substitutions for residues at the 3CLpro N1 (B), N2 (B), and C1 (C) autoprocessing sites, respectively. Substitutions introduced in the respective protein constructs are given above each lane. As controls, MBP-1343-1720-GST wt, MBP-pp1a-1343-1720_C1539A-GST mut, and MBP-lacZα were used. Total cell lysates obtained after induction of expression for 4 h at 18°C were analyzed in a 14% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Recombinantly expressed N1-C1 and N2-C1 proteins were used as marker proteins. 3CLpro N1-C1, pp1a-1377-1700_H1434A_C1539A; 3CLpro N2-C1, pp1a-1387-1700_H1434A_C1539A. Fusion proteins and processing products were detected by Western blotting using GST-specific (bottom) and CavV 3CLpro-specific (top) antibodies, respectively. The sizes (in kDa) of marker proteins are indicated to the right. The position of the fully processed form of the 3CLpro, which comigrates with the recombinant 3CLpro N2-C1 protein, is indicated by an arrowhead to the left in B and C.

As shown in Fig. 3B and C, expression of the wild-type fusion protein (MBP-pp1a-1343-1720-GST wt) resulted in a single form of 3CLpro that comigrated with the 3CLpro N2-C1 marker protein, suggesting efficient cleavage at both the N2 and C1 sites. As expected, the expression of the active-site Cys-to-Ala mutant resulted in an unprocessed fusion protein that migrated according to the expected molecular mass of ∼116 kDa. When we introduced consecutive Ala substitutions at the P2, P1, and P1′ positions of the N1 processing site (N1375A, NY1376AA, and NYS1377AAA), the major processing product comigrated in all cases with the 3CLpro N2-C1 marker protein (Fig. 3B), suggesting that both the P2-P1′ sequence itself and (most likely) proteolytic cleavage of the N1 site are not required for efficient cleavage at the N2 site. Consecutive Ala substitutions at the P2-P1′ positions of the N2 cleavage site either reduced (N1385A) or abolished (NK1386AA and NKS1387AAA) cleavage at this site. In both cases, a processing product that comigrated with the 3CLpro N1-C1 marker protein was detectable, suggesting that primarily the N1 site was cleaved in this case. Furthermore, for proteins carrying amino acid substitutions at the N2 site, we observed an additional processing product of approximately 69 kDa. The protein could be stained specifically with both the 3CLpro-specific antiserum and the GST-specific antibody, suggesting that it represented a 3CLpro-GST processing intermediate in which the C1 site remained uncleaved. In line with this hypothesis, the molecular masses for 3CLpro-GST processing intermediates were calculated to be 69.8 kDa (if cleavage occurs at the N1 site) and 68.70 kDa (if cleavage occurs at the N2 site). Interestingly, we also observed that inefficient processing of the N2 site (caused by an Asn-to-Ala replacement at the P2 position of this site) resulted in just one GST cleavage product of about 35 kDa. In contrast, the expression of the wt construct and mutant proteins with substitutions in the N1 site led to the production of two GST-containing cleavage products of ∼33 and ∼30 kDa, suggesting another cleavage event in the C-terminal GST region, as confirmed before by N-terminal sequencing of GST-containing C-terminal processing products (described above) (Fig. 1D). Similar observations were made for proteins containing additional substitutions at the N2 processing site (NK1386AA and NKS1387AAA). In both cases, cleavage at the N2 site no longer was detectable. In the triple mutant protein NKS1387AAA, the amount of N1-C1 cleavage product appeared to be further reduced while a significant amount of the 3CLpro-GST processing product was detectable. Taken together, the data further support the idea that N2 represents the primary N-terminal autoprocessing site of the CavV 3CLpro. The data also show that incomplete processing of the N2 site or the presence of a 10-aa extension at the 3CLpro amino terminus interferes with efficient processing at the C-terminal autoprocessing site. Further studies are required to investigate if (and to what extent) N-terminal autoprocessing events at the N1 and/or N2 sites control cleavage at the C-terminal 3CLpro autoprocessing site.

When we replaced 3 or 4 aa residues at the C-terminal (C1) 3CLpro processing site with Ala, the production of a processing product comigrating with the 3CLpro N2-C1 marker protein was no longer detectable, suggesting that C-terminal cleavage of the 3CLpro domain was abolished in this case (Fig. 3C, lanes NQS1701AAA and YNQS1701AAAA). In contrast, Ala substitutions for single residues at the P1 (Q1700A) or P2 (N1699A) position or even a simultaneous replacement of the P1 and P1′ positions (QS1701AA) did not interfere with the production of a fully processed form of 3CLpro comigrating with the 3CLpro N2-C1 marker protein (Fig. 3C). The data indicate that binding of the CavV 3CLpro substrate-binding pocket to this (and, possibly, other) substrate(s) involves multiple (rather than just a few critical) interactions. In the case of the NQS1701AAA and YNQS1701AAAA mutants, we detected a major cleavage product of approximately 67 kDa. The protein was specifically stained using 3CLpro-specific and GST-specific antibodies (Fig. 3C). Both its size and antibody reactivity suggest that the 67-kDa protein represents a 3CLpro-GST processing product that was released from the fusion protein precursor by cleavage at the N2 processing site.

Taken together, the data lead us to conclude that CavV 3CLpro N-terminal autoprocessing occurs very efficiently at the N2 cleavage site and remains unaffected by substitutions at the N1 processing site. Interestingly, replacements at the N2 site affected not only N-terminal but also C-terminal autoprocessing activities. Together, these observations suggest that cleavage at the N2 site is a key event in the autocatalytic release of the 3CLpro domain. Moreover, our data suggest an important role for the presence of Asn at the P2 position of CavV 3CLpro substrates. Thus, replacement of Asn-1385 with Ala significantly decreased the autoprocessing activity at the N2 autoprocessing site. Similarly, replacement of the Asn-1699 P2 residue (combined with replacements of the P1 and P1′ residues) rendered the C1 cleavage site noncleavable while P1-Gln and P1′-Ser alterations alone did not abolish cleavage at this site. The latter data provide further evidence that, in contrast to other 3C and 3C-like proteases, mesonivirus main proteases lack a pronounced specificity for a Gln/Glu residue at the P1 position.

Identification of the CavV 3CLpro in infected cells.

As described above, the in vitro data obtained in bacterial expression systems suggested that the CavV 3CLpro uses two N-terminal (N1 and N2) processing sites and one C-terminal (C1) autoprocessing site to release itself from pp1a/1ab. To further corroborate these data, we analyzed 3CLpro autoprocessing in CavV-infected C6/36 cells. To this end, total lysates from mock-infected C6/36 cells or cells infected with CavV-C79 were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using a CavV 3CLpro-specific antiserum. As additional size markers, we used the recombinant CavV 3CLpro N1-C1 and N2-C1 marker proteins described above. As shown in Fig. 4, an ∼37-kDa protein was detectable in infected (but not in mock-infected) cells. The protein comigrated with the 3CLpro N2-C1 marker protein, while there was no evidence for accumulation of the slightly larger N1-C1 form of 3CLpro. The data suggest that, in virus-infected cells, the mature form of the CavV 3CLpro is a 314-aa protein encompassing pp1a/pp1ab residues Ser-1387 to Gln-1700.

FIG 4.

Identification of the 3CLpro in CavV-infected cells. C6/36 cells were mock infected (lane 1) or infected with CavV (lane 2). Western blot analysis of total protein extracts obtained at 48 h p.i. using CavV 3CLpro-specific antiserum is shown. Molecular masses (in kDa) of prestained size markers (M) are indicated to the left. As additional size markers, two recombinant forms representing differentially processed forms of the 3CLpro domain (described in the legend to Fig. 3) were used. 3CLpro N1-C1, pp1a-1377-1700_C1539A_H1434A (lane 3); 3CLpro N2-C1, pp1a-1387-1700_C1539A_H1434A (lane 4).

Catalytic residues in the CavV 3CLpro active site.

Previous comparative sequence analyses suggested that the mesonivirus 3CLpro is a cysteine protease that uses a Cys-His-Asp catalytic triad (9) or a Cys-His catalytic dyad (8). For the CavV 3CLpro, we further suggested that Thr-1534 and His-1554 are part of the S1 subsite (9, 11) and confer specificity for Gln/Glu at the P1 position of 3CLpro substrates. To test these predictions, we performed a mutation analysis. The 3CLpro domain was expressed in E. coli TB1 cells as part of the MBP-pp1a-1343-1720-GST fusion protein construct, and proteolytic processing was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of total lysates. Consistent with the data obtained for another fusion protein construct (Fig. 1), replacement of Cys-1539 with Ala abolished autoprocessing activity (Fig. 5). Also, the replacement of His-1434 resulted in an unprocessed protein that could be detected by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 5A) and Western blotting using a 3CLpro-specific antiserum (Fig. 5B). In both cases, the induction of expression resulted in a protein migrating between the 100-kDa and 130-kDa size markers, corresponding very well with the molecular mass of 116 kDa calculated for the MBP-pp1a-1343-1720-GST fusion protein. The data support the predicted functions of Cys-1539 and His-1434 in catalysis. In contrast, replacement of Asp-1465 (D1465A) did not seem to affect the autocatalytic release of the 3CLpro domain from the pp1a-1343-1720_D1465A fusion protein, contradicting its presumed role as a third catalytic residue. We then extended our study to include other acidic residues located nearby in the primary structure and conserved among different mesonivirus species (Asp-1467, Glu-1460, and Glu-1470) (Fig. 6). None of these substitutions had detectable effects on 3CLpro autoprocessing activity in our assay, supporting the idea that CavV 3CLpro employs a Cys-His catalytic dyad as previously suggested for the NDiV homolog (8). Replacement of the putative P1-binding residue His-1554 with Ala revealed processing products of slightly less than 70 kDa, corresponding to the calculated molecular mass of the 3CLpro and GST domain-containing processing intermediate(s) (described above) (Fig. 3). The identities of the processing products could be confirmed by their reactivities with 3CLpro- and GST-specific antisera (Fig. 5B), suggesting that this protein was not processed at the C-terminal 3CLpro autoprocessing site. It remains to be analyzed whether the two proteins represent processing products cleaved at the N1 and N2 processing site, respectively. Alternatively, the slightly smaller protein may result from (nonspecific) cleavage close to the GST carboxyl terminus as observed in other experiments (Fig. 1 and 3). The apparent lack of processing at the C-terminal (but not N-terminal) 3CLpro cleavage site in the H1554A mutant is interesting and deserves further study. Replacement of Thr-1534 with Ala was tolerated without detectable reduction of 3CLpro autoprocessing activity. However, it appeared that, similar to what we observed for N2 cleavage site mutants (Fig. 3), the additional cleavage in the C-terminal GST region was less efficient in the T1534A mutant, indicating a partial reduction of proteolytic activity on other substrates, as was shown previously for bafinivirus (WBV) and arterivirus (EAV) main proteases containing the equivalent alteration (18, 25).

FIG 5.

Mutation analysis of putative catalytic and substrate-binding residues. (A and B) pMAL-c2-[pp1a-1343-1720-GST] plasmid DNA was used to express CavV pp1a/pp1ab residues 1343 to 1720 in E. coli TB1 cells. Protein expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG (right) for 4 h at 18°C or not induced (left), and total cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. (A) Coomassie blue-stained 14% SDS-polyacrylamide gel. (B) Western blot analysis using CavV 3CLpro-specific rabbit antiserum. The MBP-pp1a-1343-1720-GST fusion contained either the 3CLpro wild-type sequence or the same sequence with Ala substitutions for single-amino-acid residues potentially involved in catalysis (Cys-1539, Asp-1465, His-1434, Asp-1467, Glu-1460, and Glu-1470) or specific binding of the P1 residue (His-1554 and Thr-1534). (B) The unprocessed fusion protein precursor (MBP-pp1a-1343-1720-GST), the N-terminally processed cleavage product (3CLpro-pp1a-1700-1720-GST), and the fully processed 3CLpro domain (3CLpro) are indicated to the right. Molecular masses (in kDa) of marker proteins are indicated to the left.

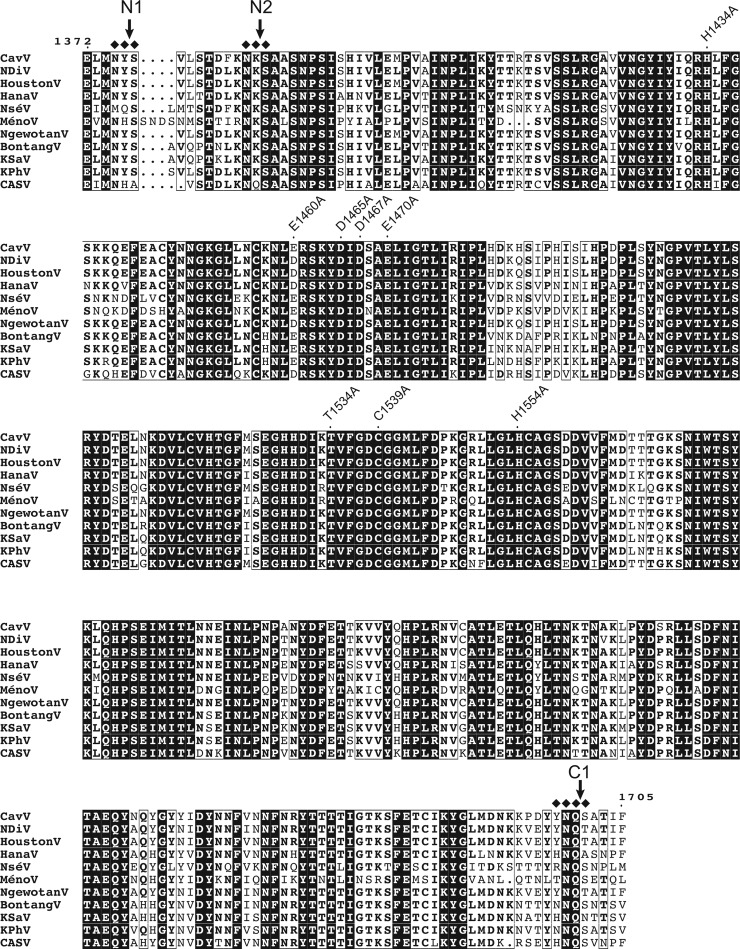

FIG 6.

Sequence alignment of mesonivirus 3CLpro domains. Shown are the putative 3CLpro domains of representative mesoniviruses, together with the predicted N- and C-terminal processing sites (indicated as N1, N2, and C1, respectively; see the text for details). Amino acid numbering is according to the position in the CavV pp1a/pp1ab amino acid sequence. Ala substitutions for specific residues in CavV 3CLpro that were characterized in this study are indicated. Filled diamonds denote residues near the scissile bond of the N1, N2, and C1 cleavage site, respectively, that were characterized by site-directed mutagenesis in this study. Abbreviations of virus names are the following: CavV, Cavally virus (isolate C79); NDiV, Nam Dinh virus (isolate 02VN178); HoustonV, Houston virus (strain V3982); HanaV, Hana virus (strain A4/CI/2004); NséV, Nsé virus (strain F24/CI/2004); MénoV, Méno virus (strain E9/CI/2004); NgewotanV, Ngewotan virus (strain JKT9982); BontangV, Bontang virus (strain JKT7774); KSaV, Karang Sari virus (strain JKT10701); KPhV, Kamphang Phet virus (strain KP84-0344); CASV, Casuarina virus (isolate 0071).

DISCUSSION

In this report, we present the first characterization of a mesonivirus nonstructural protein, the CavV 3CLpro, an ORF1a-encoded chymotrypsin-like protease that, by analogy with other nidoviruses and many other plus-strand RNA viruses, is thought to play a key role in proteolytic processing of the mesonivirus replicase polyproteins (16, 35). Using a bacterial expression system, we confirmed the predicted autoprocessing activity of the CavV 3CLpro domain and identified N- and C-terminal 3CLpro autoprocessing sites by N-terminal sequencing of appropriate processing products. Based on the data obtained in this study, we suggest that the mature form of the 3CLpro is produced by N-terminal cleavage at FKNK1386|SAAS (the so-called N2 site) and C-terminal cleavage at YYNQ1700|SATI (the C1 site). Consistent with our biochemical data, subsequent experiments using CavV-infected cells identified an ∼37-kDa protein that was recognized by a CavV 3CLpro-specific antiserum and comigrated with a recombinantly expressed marker protein comprising CavV pp1a/1ab residues Ser-1387 to Gln-1700.

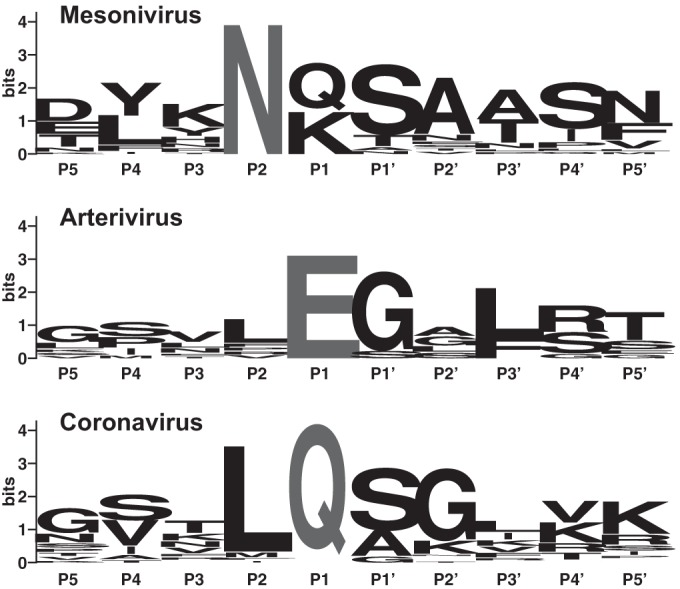

In contrast to the C-terminal cleavage of the 3CLpro, which consistently occurred at the C1 site, we obtained evidence that N-terminal processing is more complex. Besides processing at the FKNK1386|SAAS (N2) site, we obtained clear evidence for cleavage at a second (more upstream) position, LMNY1376|SVLS (N1 site), using bacterial expression systems and a range of experimental conditions. Together, the data lead us to conclude that N2 is the dominant site for N-terminal autoprocessing and full activation of the CavV 3CLpro. At present, the role of the N1 site is less clear, and further studies are required to investigate the biological significance of cleavage at the N1 site which is well conserved among mesoniviruses and conforms to the tentative mesonivirus 3CLpro substrate specificity identified in this study (Fig. 6 and 7).

FIG 7.

3CLpro autoprocessing sites in mesoni-, arteri-, and coronaviruses. Alignments of the P5-P5′ positions of N- and C-terminal autoprocessing sites of nidovirus 3CLpro domains were used to produce sequence logo presentations (43). Alignments included sequences from 11 mesoniviruses (Fig. 6 and the legend to Fig. 6), 5 arteriviruses (from 4 approved species) (44), and 20 coronaviruses, the latter representing all 17 approved alpha-, beta-, and gammacoronavirus species and another 3 yet-to-be-approved species from the genus Deltacoronavirus (4, 45). The height of each letter (amino acid residue) is proportional to the frequency of a specific residue at a given position. Strictly conserved residues at the P1 and P2 positions are indicated in gray. Accession numbers of arterivirus and coronavirus sequences used in this analysis include the following: equine arteritis virus (Bucyrus), NC_002532; simian hemorrhagic fever virus, NC_003092; porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) (VR-2332), U87392; PRRSV (Lelystad), M96262; lactate dehydrogenase elevating virus (Plagemann), NC_001639; transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus (Purdue), AJ271965; human coronavirus (HCoV) 229E, AF304460; HCoV-NL63 (Amsterdam 1), AY567487; Miniopterus bat CoV 1 (Mi-BatCoV 1), EU420138; Mi-BatCoV HKU8, EU420139; porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, AF353511; Rhinolophus bat CoV, EF203065; Scotophilus bat CoV 512, DQ648858; bovine coronavirus (Mebus), U00735; HCoV-HKU1, AY597011; mouse hepatitis virus (JHM), AC_000192; Pipistrellus bat CoV HKU5 (Pi-BatCoV HKU5), EF065509; Rousettus bat CoV HKU9 (Ro-BatCoV HKU9), EF065513; severe acute respiratory syndrome-CoV (Urbani), AY278741; Tylonycteris bat CoV HKU4 (Ty-BatCoV HKU4), EF065505; infectious bronchitis virus (Beaudette), M95169; beluga whale CoV SW1, EU111742; munia CoV HKU13, FJ376622; bulbul CoV HKU11, FJ376619; thrush CoV HKU12, FJ376621.

Similar to most other viral 3C and 3C-like proteases, nidovirus 3C-like proteases have a pronounced preference for Gln or Glu at the P1 position and small aliphatic residues at the P1′ position (16). Additional residues may contribute to substrate binding. For example, in the case of coronavirus, ronivirus, and torovirus 3C-like proteases, residues at the P2 and P4 positions are thought to be additional specificity determinants (16, 17, 19, 36, 37) (Fig. 7). Interestingly, the specificity data obtained in our study for the mesonivirus 3CLpro do not conform to the substrate specificities determined for (all) other nidoviruses. Based on the 3 cleavage sites determined in this study and comparison with putative 3CLpro autoprocessing sites of other mesoniviruses (Fig. 6), we conclude that the P1 residue is not conserved and residues other than Glu or Gln may be present at the P1 position. To our knowledge, this represents a unique feature not observed in any other nidovirus main proteases characterized previously. Comparison of the 3 cleavage sites (Fig. 6 and 7) further revealed that Asn is conserved at the P2 position of the N2, C1, and N1 processing sites, suggesting that the P2 (rather than P1) position is the key specificity determinant in mesonivirus main proteases. To validate this hypothesis, we did a mutagenesis analysis of the N- and C-terminal 3CLpro autoprocessing sites. We found that Ala substitutions at the N1 cleavage site did not significantly affect 3CLpro autoprocessing activity at the N2 and C1 site, respectively, whereas substitutions at the N2 site caused major autoprocessing defects (Fig. 3) at both N- and C-terminal processing sites. Together, the data show that efficient cleavage of the N2 site is required for optimal autoprocessing activity of the mesonivirus 3CLpro. In contrast, an N-terminally extended form of the 3CLpro produced by cleavage at the N1 site (only) and containing replacements that blocked cleavage at the N2 site did not retain wt proteolytic activity, suggesting that N-terminal autoprocessing at the N2 site is required for full activation of the CavV 3CLpro.

Although additional cleavage sites need to be characterized to obtain the full picture of mesonivirus 3CLpro substrate specificity, the available data provide strong evidence to suggest that the substrate specificity of the CavV 3CLpro differs from that of other nidoviruses. It appears that Asn at the P2 position and the presence of a relatively small aliphatic residue at the P1′ position and a bulky residue at the P4 position contribute to substrate binding. Furthermore, the observed limited degree of sequence conservation near the scissile bond of confirmed cleavage sites indicates that additional factors, such as local folding and secondary structure elements, contribute to (or are required for) specific 3CLpro-mediated cleavages in the CavV replicase polyproteins. With respect to conserved residues potentially involved in forming important specificity subsites, we and others suggested that the CavV 3CLpro His-1554 residue and its equivalent in NDiV have a role in binding potential P1-Gln/Glu residues. This His residue is part of a GxH motif conserved in many 3C and 3C-like proteases and was shown to specifically interact with the side chain of the Glu/Gln-P1 residue conserved in typical 3Cpro/3CLpro substrates by forming hydrogen bonds to the carbonyl/carboxylate oxygens of the P1 residue (20, 23, 24, 38–40). In addition to the conserved His residue, many viral main proteases possess a second conserved residue (often Thr) that assists in the binding of the P1 residue and, in the primary structure, is located five residues upstream of the principal nucleophilic Cys/Ser residue. Sequence comparison of the CavV 3CLpro identified possible counterparts of the conserved His and Thr residues (His-1554 and Thr-1534) in the presumed S1 specificity subsite (9). Surprisingly, we and others failed to identify a conserved Glu/Gln residue at confirmed (this study) and predicted (8) mesonivirus 3CLpro cleavage sites, raising doubts as to whether the conserved CavV pp1a/pp1ab His-1554 residue has the same critical role in P1-Gln/Glu binding as its presumed counterparts in other 3C and 3C-like proteases. Another possibility is that only a subset of cleavage sites have Gln/Glu at the P1 position; therefore, His-1554 is required for cleavage at just a few sites. In this context, we observed that replacement of the His-1554 residue with Ala prevented cleavage at the C1 site (which contains Gln at the P1 position), while cleavage at the N2 site (which contains Lys at the P1 position) remained unaffected. Based on these data, it is tempting to speculate that His-1554 is required for efficient cleavage of the C1 site, while it is dispensable for cleavage at sites that lack a Gln/Glu residue at the P1 position. Further experiments are needed to corroborate this hypothesis. Yet another explanation for the conservation of the GxH motif in mesonivirus 3CLpros is that the His-1554 imidazole side chain interacts with the carboxamide moiety of the P2-Asn side chain (rather than the carboxamide group of the P1-Gln side chain), probably involving identical hydrogen bond interactions.

As previously seen in other nidovirus proteases, sequence conservation of mesonivirus main proteases appears to be limited to regions containing predicted active-site residues (9, 17–19). Our earlier studies suggested that the CavV 3CLpro active site uses a catalytic triad comprised of Cys-1539, His-1434, and Asp-1465 (9, 11). However, the replacement of the presumed third catalytic residue, Asp-1465, and several other conserved acidic residues located in this region of the protein had no detectable effect on CavV 3CLpro autoprocessing activity. Therefore, we conclude that, in line with predictions made for the related NDiV 3CLpro (8), the CavV 3CLpro employs a catalytic Cys-His dyad comprised of Cys-1539 and His-1434. This observation provides a link to the main proteases of coronaviruses and roniviruses, which both use 3C-like proteases with a Cys-His catalytic dyad (19, 20, 26, 28, 40).

In conclusion, this first characterization of a mesonivirus nonstructural protein supports and extends previous conclusions on the special position of this group of insect viruses among other nidoviruses. It appears that, while retaining some of the conserved properties of nidovirus main proteases (catalytic system and N-terminal two-β-barrel fold structure), mesonivirus 3CLpros have evolved properties that separate them from other nidovirus proteases. In particular, this applies to the unique substrate specificity identified for the CavV 3CLpro in this study. It is characterized by the lack of a conserved P1-Gln/Glu residue and the conservation of a P2-Asn residue. Other specificity determinants tentatively identified for mesonivirus main proteases also define a special group of nidovirus main proteases, for example, the apparent conservation of bulky (but variable) residues at the P4 position and aliphatic residues at the P1′ position. With a total of 314 residues, the mature form of 3CLpro of CavV is larger than that of other nidoviruses (except for the ronivirus 3CLpro, whose C-terminal autoprocessing remains to be investigated). The large size of the mesonivirus 3CLpro is due mainly to an extended C-terminal domain with a (predicted) mixed α/β structure (41, 42). Partial conservation of secondary structure elements in the 3CLpro C-terminal domains, the use of a catalytic Cys-His dyad, and a P2 residue with a polar side chain as a main specificity determinant (His in roniviruses, Asn in mesoniviruses) (19) may lend additional support to the possible common ancestry of roniviruses and mesoniviruses proposed in earlier studies (8, 14).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Karin Schultheiß for excellent technical assistance.

The work of J.Z. is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB1021, A01).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 17 September 2014

REFERENCES

- 1. de Groot RJ, Cowley JA, Enjuanes L, Faaberg KS, Perlman S, Rottier PJM, Snijder EJ, Ziebuhr J, Gorbalenya AE. 2012. Order Nidovirales, p 785–795 In King AMQ, Adams MJ, Carstens EB, Lefkowitz EJ. (ed), Virus taxonomy. Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lauber C, Ziebuhr J, Junglen S, Drosten C, Zirkel F, Nga PT, Morita K, Snijder EJ, Gorbalenya AE. 2012. Mesoniviridae: a proposed new family in the order Nidovirales formed by a single species of mosquito-borne viruses. Arch. Virol. 157:1623–1628. 10.1007/s00705-012-1295-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cowley JA, Dimmock CM, Spann KM, Walker PJ. 2000. Gill-associated virus of Penaeus monodon prawns: an invertebrate virus with ORF1a and ORF1b genes related to arteri- and coronaviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 81:1473–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Groot RJ, Baker SC, Baric R, Enjuanes L, Gorbalenya AE, Holmes KV, Perlman S, Poon L, Rottier PJM, Talbot PJ, Woo PCY, Ziebuhr J. 2012. Family Coronaviridae, p 806–828 In King AMQ, Adams MJ, Carstens EB, Lefkowitz EJ. (ed), Virus taxonomy. Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Graham RL, Donaldson EF, Baric RS. 2013. A decade after SARS: strategies for controlling emerging coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11:836–848. 10.1038/nrmicro3143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schütze H, Ulferts R, Schelle B, Bayer S, Granzow H, Hoffmann B, Mettenleiter TC, Ziebuhr J. 2006. Characterization of White bream virus reveals a novel genetic cluster of nidoviruses. J. Virol. 80:11598–11609. 10.1128/JVI.01758-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Snijder EJ, Kikkert M, Fang Y. 2013. Arterivirus molecular biology and pathogenesis. J. Gen. Virol. 94:2141–2163. 10.1099/vir.0.056341-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nga PT, Parquet Mdel C, Lauber C, Parida M, Nabeshima T, Yu F, Thuy NT, Inoue S, Ito T, Okamoto K, Ichinose A, Snijder EJ, Morita K, Gorbalenya AE. 2011. Discovery of the first insect nidovirus, a missing evolutionary link in the emergence of the largest RNA virus genomes. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002215. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zirkel F, Kurth A, Quan PL, Briese T, Ellerbrok H, Pauli G, Leendertz FH, Lipkin WI, Ziebuhr J, Drosten C, Junglen S. 2011. An insect nidovirus emerging from a primary tropical rainforest. mBio 2:e00077–00011. 10.1128/mBio.00077-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kuwata R, Satho T, Isawa H, Yen NT, Phong TV, Nga PT, Kurashige T, Hiramatsu Y, Fukumitsu Y, Hoshino K, Sasaki T, Kobayashi M, Mizutani T, Sawabe K. 2013. Characterization of Dak Nong virus, an insect nidovirus isolated from Culex mosquitoes in Vietnam. Arch. Virol. 158:2273–2284. 10.1007/s00705-013-1741-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zirkel F, Roth H, Kurth A, Drosten C, Ziebuhr J, Junglen S. 2013. Identification and characterization of genetically divergent members of the newly established family Mesoniviridae. J. Virol. 87:6346–6358. 10.1128/JVI.00416-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thuy NT, Huy TQ, Nga PT, Morita K, Dunia I, Benedetti L. 2013. A new nidovirus (NamDinh virus NDiV): its ultrastructural characterization in the C6/36 mosquito cell line. Virology 444:337–342. 10.1016/j.virol.2013.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gorbalenya AE, Enjuanes L, Ziebuhr J, Snijder EJ. 2006. Nidovirales: evolving the largest RNA virus genome. Virus Res. 117:17–37. 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lauber C, Goeman JJ, Parquet Mdel C, Nga PT, Snijder EJ, Morita K, Gorbalenya AE. 2013. The footprint of genome architecture in the largest genome expansion in RNA viruses. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003500. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ziebuhr J. 2008. Coronavirus replicative proteins, p 65–81 In Perlman S, Gallagher T, Snijder EJ. (ed), Nidoviruses. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ziebuhr J, Snijder EJ, Gorbalenya AE. 2000. Virus-encoded proteinases and proteolytic processing in the Nidovirales. J. Gen. Virol. 81:853–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smits SL, Snijder EJ, de Groot RJ. 2006. Characterization of a torovirus main proteinase. J. Virol. 80:4157–4167. 10.1128/JVI.80.8.4157-4167.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ulferts R, Mettenleiter TC, Ziebuhr J. 2011. Characterization of bafinivirus main protease autoprocessing activities. J. Virol. 85:1348–1359. 10.1128/JVI.01716-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ziebuhr J, Bayer S, Cowley JA, Gorbalenya AE. 2003. The 3C-like proteinase of an invertebrate nidovirus links coronavirus and potyvirus homologs. J. Virol. 77:1415–1426. 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1415-1426.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Anand K, Palm GJ, Mesters JR, Siddell SG, Ziebuhr J, Hilgenfeld R. 2002. Structure of coronavirus main proteinase reveals combination of a chymotrypsin fold with an extra alpha-helical domain. EMBO J. 21:3213–3224. 10.1093/emboj/cdf327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gorbalenya AE, Donchenko AP, Blinov VM, Koonin EV. 1989. Cysteine proteases of positive strand RNA viruses and chymotrypsin-like serine proteases. A distinct protein superfamily with a common structural fold. FEBS Lett. 243:103–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bazan JF, Fletterick RJ. 1988. Viral cysteine proteases are homologous to the trypsin-like family of serine proteases: structural and functional implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 85:7872–7876. 10.1073/pnas.85.21.7872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Allaire M, Chernaia MM, Malcolm BA, James MN. 1994. Picornaviral 3C cysteine proteinases have a fold similar to chymotrypsin-like serine proteinases. Nature 369:72–76. 10.1038/369072a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Barrette-Ng IH, Ng KK, Mark BL, Van Aken D, Cherney MM, Garen C, Kolodenko Y, Gorbalenya AE, Snijder EJ, James MN. 2002. Structure of arterivirus nsp4. The smallest chymotrypsin-like proteinase with an alpha/beta C-terminal extension and alternate conformations of the oxyanion hole. J. Biol. Chem. 277:39960–39966. 10.1074/jbc.M206978200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Snijder EJ, Wassenaar AL, van Dinten LC, Spaan WJ, Gorbalenya AE. 1996. The arterivirus nsp4 protease is the prototype of a novel group of chymotrypsin-like enzymes, the 3C-like serine proteases. J. Biol. Chem. 271:4864–4871. 10.1074/jbc.271.9.4864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ziebuhr J, Heusipp G, Siddell SG. 1997. Biosynthesis, purification, and characterization of the human coronavirus 229E 3C-like proteinase. J. Virol. 71:3992–3997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu DX, Brown TD. 1995. Characterisation and mutational analysis of an ORF 1a-encoding proteinase domain responsible for proteolytic processing of the infectious bronchitis virus 1a/1b polyprotein. Virology 209:420–427. 10.1006/viro.1995.1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hegyi A, Friebe A, Gorbalenya AE, Ziebuhr J. 2002. Mutational analysis of the active centre of coronavirus 3C-like proteases. J. Gen. Virol. 83:581–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schechter I, Berger A. 1967. On the size of the active site in proteases. I. Papain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 27:157–162. 10.1016/S0006-291X(67)80055-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gorbalenya AE, Snijder EJ. 1996. Viral cysteine proteases. Perspect. Drug Discov. Design 6:64–86. 10.1007/BF02174046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yao Z, Jones DH, Grose C. 1992. Site-directed mutagenesis of herpesvirus glycoprotein phosphorylation sites by recombination polymerase chain reaction. PCR Methods Appl. 1:205–207. 10.1101/gr.1.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pinon JD, Mayreddy RR, Turner JD, Khan FS, Bonilla PJ, Weiss SR. 1997. Efficient autoproteolytic processing of the MHV-A59 3C-like proteinase from the flanking hydrophobic domains requires membranes. Virology 230:309–322. 10.1006/viro.1997.8503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tibbles KW, Brierley I, Cavanagh D, Brown TD. 1996. Characterization in vitro of an autocatalytic processing activity associated with the predicted 3C-like proteinase domain of the coronavirus avian infectious bronchitis virus. J. Virol. 70:1923–1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ziebuhr J, Herold J, Siddell SG. 1995. Characterization of a human coronavirus (strain 229E) 3C-like proteinase activity. J. Virol. 69:4331–4338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dougherty WG, Semler BL. 1993. Expression of virus-encoded proteinases: functional and structural similarities with cellular enzymes. Microbiol. Rev. 57:781–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fan K, Wei P, Feng Q, Chen S, Huang C, Ma L, Lai B, Pei J, Liu Y, Chen J, Lai L. 2004. Biosynthesis, purification, and substrate specificity of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 3C-like proteinase. J. Biol. Chem. 279:1637–1642. 10.1074/jbc.M310875200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hegyi A, Ziebuhr J. 2002. Conservation of substrate specificities among coronavirus main proteases. J. Gen. Virol. 83:595–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bergmann EM, Mosimann SC, Chernaia MM, Malcolm BA, James MN. 1997. The refined crystal structure of the 3C gene product from hepatitis A virus: specific proteinase activity and RNA recognition. J. Virol. 71:2436–2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mosimann SC, Cherney MM, Sia S, Plotch S, James MN. 1997. Refined X-ray crystallographic structure of the poliovirus 3C gene product. J. Mol. Biol. 273:1032–1047. 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yang H, Yang M, Ding Y, Liu Y, Lou Z, Zhou Z, Sun L, Mo L, Ye S, Pang H, Gao GF, Anand K, Bartlam M, Hilgenfeld R, Rao Z. 2003. The crystal structures of severe acute respiratory syndrome virus main protease and its complex with an inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:13190–13195. 10.1073/pnas.1835675100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Buchan DW, Minneci F, Nugent TC, Bryson K, Jones DT. 2013. Scalable web services for the PSIPRED Protein Analysis Workbench. Nucleic Acids Res. 41:W349–W357. 10.1093/nar/gkt381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jones DT. 1999. Protein secondary structure prediction based on position-specific scoring matrices. J. Mol. Biol. 292:195–202. 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schneider TD, Stephens RM. 1990. Sequence logos: a new way to display consensus sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:6097–6100. 10.1093/nar/18.20.6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Faaberg KS, Balasuriya UB, Brinton MA, Gorbalenya AE, Leung FC-C, Nauwynck H, Snijder EJ, Stadejek T, Yang H, Yoo D. 2012. Family Arteriviridae, p 796–805 In King AMQ, Adams MJ, Carstens EB, Lefkowitz EJ. (ed), Virus taxonomy. Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 45. de Groot RJ, Baker SC, Baric RS, Brown CS, Drosten C, Enjuanes L, Fouchier RA, Galiano M, Gorbalenya AE, Memish ZA, Perlman S, Poon LL, Snijder EJ, Stephens GM, Woo PC, Zaki AM, Zambon M, Ziebuhr J. 2013. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): announcement of the Coronavirus Study Group. J. Virol. 87:7790–7792. 10.1128/JVI.01244-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]