Abstract

Fire blight is caused by Erwinia amylovora and is the most destructive bacterial disease of apples and pears worldwide. In this study, we found that E. amylovora argD(1000)::Tn5, an argD Tn5 transposon mutant that has the Tn5 transposon inserted after nucleotide 999 in the argD gene-coding region, was an arginine auxotroph that did not cause fire blight in apple and had reduced virulence in immature pear fruits. The E. amylovora argD gene encodes a predicted N-acetylornithine aminotransferase enzyme, which is involved in the production of the amino acid arginine. A plasmid-borne copy of the wild-type argD gene complemented both the nonpathogenic and the arginine auxotrophic phenotypes of the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant. However, even when mixed with virulent E. amylovora cells and inoculated onto immature apple fruit, the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant still failed to grow, while the virulent strain grew and caused disease. Furthermore, the pCR2.1-argD complementation plasmid was stably maintained in the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant growing in host tissues without any antibiotic selection. Therefore, the pCR2.1-argD complementation plasmid could be useful for the expression of genes, markers, and reporters in E. amylovora growing in planta, without concern about losing the plasmid over time. The ArgD protein cannot be considered an E. amylovora virulence factor because the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant was auxotrophic and had a primary metabolism defect. Nevertheless, these results are informative about the parasitic nature of the fire blight disease interaction, since they indicate that E. amylovora cannot obtain sufficient arginine from apple and pear fruit tissues or from apple vegetative tissues, either at the beginning of the infection process or after the infection has progressed to an advanced state.

INTRODUCTION

Fire blight is the most economically important and destructive bacterial disease in apples and pears that exists today. It is also a very well-known bacterial disease, in part because it was the first bacterial plant disease that was discovered (1, 2). The causal agent of fire blight disease is the bacterium Erwinia amylovora, a nonobligate pathogen (3). When E. amylovora infects the different parts of an apple tree, they look as if they were burned; therefore, the disease was named fire blight (4). The bacterial ooze coming out of infected apple tree bark and/or infected apple tree fruit is the most important and characteristic sign of fire blight disease (1, 2). E. amylovora also infects other members of the Rosaceae family, including quince, loquat, hawthorn, and other ornamentals (5–7).

Fire blight has been documented as an important plant disease problem for more than 200 years (8). Unfortunately, fire blight disease continues to be the cause of major sporadic losses, for example, a $68 million loss in the northwestern part of the United States in 1998 (9) and a $42 million loss in the state of Michigan, USA, in 2000 (10). Fire blight is also a perennial problem for apple and pear growers in regions where the disease is endemic (11). Furthermore, fire blight now threatens to be even more economically significant, since the disease continues to spread all around the world (11).

Since the 1980s, scientists have been working to identify E. amylovora genetic factors that contribute to the capacity of the bacterium to cause fire blight disease in apple and pear. The amylovoran synthesis (ams), hypersensitive response and pathogenicity (hrp), and disease-specific (dsp) genes are some of the most studied and most important E. amylovora virulence genes discovered to date (12–20).

Novel E. amylovora genes contributing to virulence and pathogenicity continue to be discovered to this day, including recent examples like waaL, rpoN, rcs, luxS, and hns (21–26). These genetic studies provide a better understanding of the pathogen and have the potential to provide new methods to manage the disease. For example, salicylidene acylhydrazides can suppress the expression of type III secretion and amylovoran biosynthesis genes in Erwinia amylovora, indicating that small molecules have the potential to be developed as fire blight controls (27). This is of practical importance because, with the exception of the antibiotic streptomycin, there are no registered products in the United States that can effectively control fire blight (28–31). In fact, 90% of the streptomycin used in the United States in agriculture is used to control fire blight (32). Unfortunately, streptomycin resistance has been detected in E. amylovora field populations in different parts of the world, including the United States, Mexico, and Canada (33–35).

In order to discover additional genetic aspects critical for E. amylovora's pathogenicity, we mutagenized E. amylovora strain HKN06P1 (Table 1) (36) with an engineered Tn5 transposon. The E. amylovora mutants were screened for loss of virulence on immature apple fruits. One of the E. amylovora mutants that did not cause disease in immature apple fruits had a Tn5 transposon insertion in the argD gene. The E. amylovora argD gene is predicted to encode an enzyme called N-acetylornithine aminotransferase, which is involved in step number four of the arginine biosynthesis pathway (37–40). N-Acetylornithine aminotransferase transfers an amino group from l-glutamate to the aldehydic carbon of N-acetyl-l-glutamate semialdehyde to produce N-acetyl-l-ornithine (39). Like most aminotransferases, N-acetylornithine aminotransferase is dependent on pyridoxal 5′-phosphate as a catalytic cofactor (41). In E. amylovora, the argD gene does not appear to be part of an operon and is separated from the rest of the arg genes, just as in Escherichia coli and Xanthomonas campestris (38, 40). However, in some other bacteria, such as Streptomyces clavuligerus, all the arg genes, including argD, are clustered in an operon (42). The E. coli ArgD protein is involved in lysine biosynthesis, as well (39); however, this dual enzymatic capacity of ArgD has not been demonstrated in E. amylovora. In the present study, we show that mutation of the E. amylovora argD gene causes arginine auxotrophy, nonpathogenicity in apple, and reduced virulence in immature pear fruit.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids, bacterial strains, and oligonucleotides used in this work

| Construct | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1 | PCR cloning vector without an insert (Kanr Carr) | TOPO TA kit; Invitrogen |

| EZ-Tn5-argD | Plasmid rescued from argD(1000)::Tn5 (Kanr) | This work |

| pCR2.1-argD | argD cloned in pCR2.1 (Kanr Carr) | This work |

| Bacterial strain or genotype | ||

| E. amylovora HKN06P1 | Wild-type strain | 36 |

| argD(1000)::Tn5 | E. amylovora HKN06P1 carrying a Tn5 transposon insertion in the argD gene (Kanr) | This work |

| argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1) | argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant carrying pCR2.1 (Kanr Carr) | This work |

| argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) | argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant carrying pCR2.1-argD (Kanr Carr) | This work |

| HKN06P1NalR | Nalidixic acid-resistant derivative of wild-type E. amylovora HKN06P1 | This work |

| HKN06P1NalR(pCR2.1) | Nalidixic acid-resistant derivative of wild-type E. amylovora HKN06P1 carrying pCR2.1 | This work |

| HKN06P1NalR(pCR2.1-argD) | Nalidixic acid-resistant derivative of wild-type E. amylovora HKN06P1 carrying pCR2.1-argD | This work |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| P1 | 5′-GGATCCCACCATGGCCACTGGATGAT-3′ | This work |

| P2 | 5′-GCCGGCGGAAAGCATTCTGAGCGAGC-3′ | This work |

| FP | 5′-GCCAACGACTACGCACTAGCCAAC-3′ | EZ-Tn5 kit; Epicentre |

| RP | 5′-GAGCCAATATGCGAGAACACCCGAGAA-3′ | EZ-Tn5 kit; Epicentre |

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Screening process for loss of pathogenicity.

E. amylovora strain HKN06P1 was mutagenized with an engineered Tn5 transposon according to the manufacturer's instructions (EZ-Tn5<R6KγoriKan-2> transposome kit; Epicentre, Madison, WI). Around 2,000 E. amylovora mutants were screened for loss of pathogenicity in detached immature ‘Gala' apple fruits. During the initial round of screening, one immature apple fruit was inoculated per mutant. Mutants that did not cause disease by 10 days postinoculation (dpi) were then inoculated onto 5 immature apples during the second screening round. Mutants that did not cause disease during the second screening were inoculated onto 10 apples in the third screening. During the third screening, the 10 apples were inoculated with 20 μl of a mutant bacterial suspension in 10 mM MgCl2 solution at an absorbance of 0.1 (λ = 600), as measured using a Spectronic 20+ spectrophotometer (Spectronic Instruments, Inc., Irvine, CA). The screening conditions were 28°C and 100% relative humidity. A mutant in which the Tn5 transposon was inserted after nucleotide 999 in the argD gene-coding region [argD(1000)::Tn5] (Table 1) did not cause fire blight disease in detached immature apple fruits and was selected for further study.

Molecular characterization of the Tn5 transposon insertion in the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant.

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was isolated from the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant (Wizard Genomic DNA purification kit, Promega, Madison, WI). An amount of 5 μg of argD(1000)::Tn5 gDNA was digested in a total reaction mixture volume of 100 μl, with 10 μl of 10× EcoRI enzyme buffer and 2 μl of EcoRI enzyme (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA). The reaction was run overnight at 37°C with a 50-μl mineral oil overlay. The digestion reaction volume was cleaned (QIAquick gel extraction kit; Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and eluted in 35 μl of elution buffer (EB). EcoRI-digested fragments of argD(1000)::Tn5 gDNA were circularized with 10 μl of 10× buffer T4, 2 μl of T4 DNA ligase (New England BioLabs) in a 100-μl reaction mixture volume at room temperature overnight. Then, the ligation reaction mixture was cleaned (QIAquick gel extraction kit) and eluted in 20 μl of EB. The circularized argD(1000)::Tn5 gDNA fragments were introduced into Transformax EC100D pir-116 electrocompetent E. coli cells (Epicentre) using an Electroporator 2510 (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) at 2,500 V. EZ-Tn5-argD plasmid DNA (Table 1) was isolated from the resulting kanamycin-resistant colonies (QIAquick kit; Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and used as the template for DNA sequencing according to the manufacturer's instructions for the EZ-Tn5<R6KγoriKan-2> transposome kit (Epicentre) at the Genomics Core Facility at The Pennsylvania State University at University Park, PA. The position of the flanking DNA sequence was then determined on the genome sequence of E. amylovora strain CFBP 1430 (43) by using NCBI's BLASTN program (44).

PCR protocols.

PCR was used to amplify the argD gene from wild-type E. amylovora HKN06P1 gDNA using a thermal cycler (Eppendorf), oligonucleotide primers P1 and P2 (Table 1), and Advantage 2 polymerase reaction mix (Mountain View, CA). The thermal cycler was programmed to run for 2 min at 95°C, followed by 12 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 90 s at 72°C.

To verify the position of the Tn5 transposon in the chromosome of the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant, PCR was performed using primers P1, P2, FP, and RP (Table 1). The preheating, denaturation, annealing and extension time, and temperature were the same as described above, except that a 4-min extension time was used to amplify the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant's argD gene, including the Tn5 transposon insertion.

Plasmid introductions and complementation of the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant.

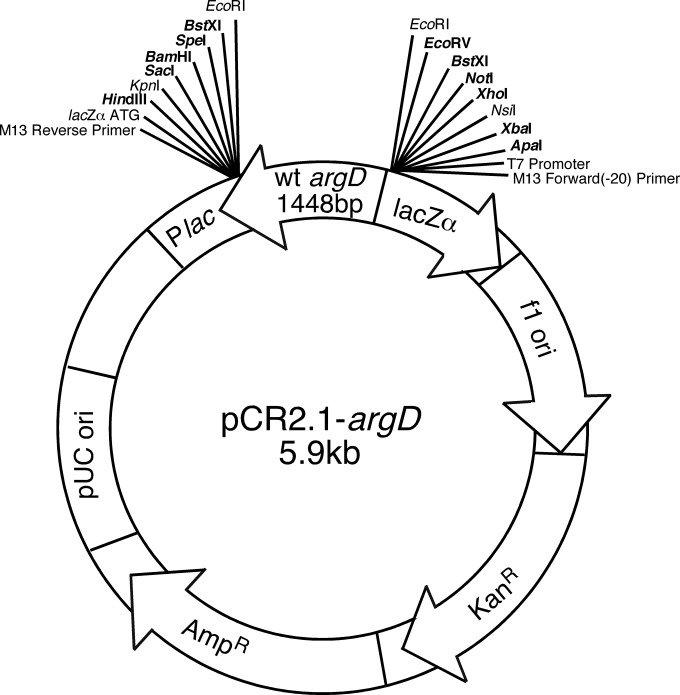

The amplified PCR product of the wild-type E. amylovora HKN06P1 argD gene, with a length of 1,448 bp, was cloned into pCR2.1 (TOPO TA kit; Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) according to the manufacturer's instructions, creating pCR2.1-argD (Table 1). The pCR2.1-argD insert was sequenced at The Pennsylvania State University—University Park at the Genomics Core Facility, using T7 and M13R as the forward and reverse primers, respectively. The cloned segment included 145 bp upstream from the argD gene start codon and 90 bp downstream from the stop codon. These upstream and downstream DNA segments included 77 bp and 58 bp of the argD flanking genes yhfK and pabA, respectively. The 1,448-bp cloned segment was identical in sequence to that of the E. amylovora CFBP 1430 reference genome (Fig. 1). Plasmids were introduced into E. amylovora competent cells using an Electroporator 2510 (Eppendorf) at 2,500 V according to the manufacturer's instructions. E. amylovora competent cells were prepared according to Epicentre's instructions for E. coli, except that the E. amylovora cultures were grown at 28°C to a final absorbance of 0.5 to 0.6 (λ = 600).

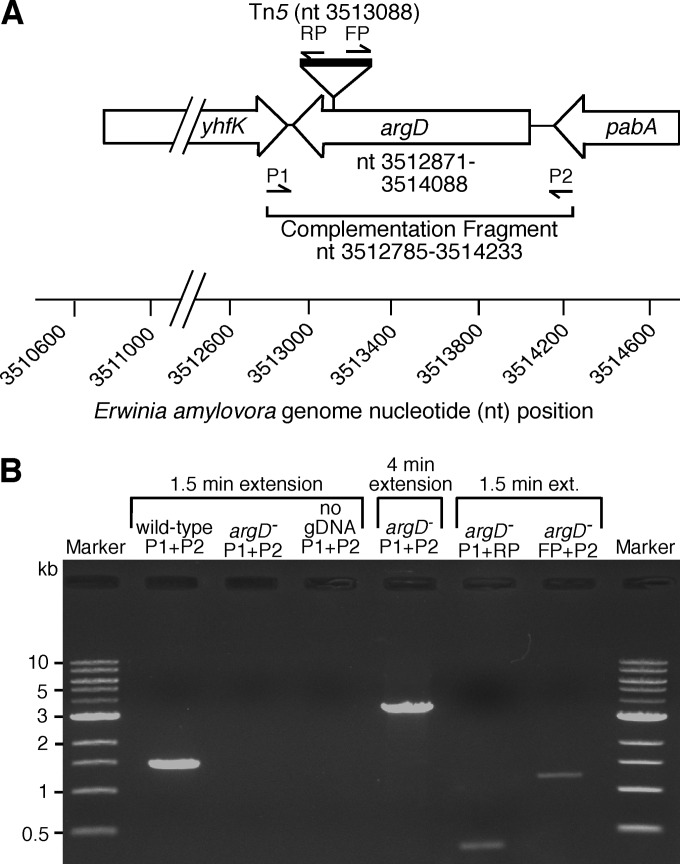

FIG 1.

(A) Illustration of the argD gene and flanking genes yhfK and pabA showing the genome nucleotide position of the Tn5 insertion in the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant and the genomic DNA (gDNA) segment used for complementation. Genome nucleotide positions are numbered according to their homologous positions in the complete genome sequence of E. amylovora CFBP 1430. PCR primer (Table 1) hybridization locations and directions are indicated. (B) PCR analysis and agarose gel electrophoresis were used to verify Tn5 transposon insertion in the argD gene in the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant. Using primers P1 and P2, a 1,448-bp PCR product was amplified from wild-type gDNA but not from that of the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant (argD−), as expected. When the PCR extension time was increased to 4 min with primers P1 and P2, a 3,449-bp PCR product was amplified from the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant's gDNA, representing the argD gene interrupted by Tn5. As expected, primer combinations P1 plus RP and FP plus P2 amplified a 303- and a 1,145-bp product, respectively, further confirming the presence of a Tn5 transposon insertion in the argD gene of the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant. Control PCRs with no gDNA template produced no PCR products.

Quantitative growth analysis in M9 minimal medium.

The wild-type strain was grown overnight in LB broth, the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant was grown overnight in LB broth supplemented with 50 μg/ml of kanamycin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and the argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1) and argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) strains (Table 1) were grown overnight in LB broth supplemented with 100 μg/ml of carbenicillin (RPI, Mount Prospect, IL). All the strains were grown at 28°C with rotary shaking at 200 rpm. Cells were pelleted at 13,000 rpm for 1 min and washed twice with 1 ml of 10 mM MgCl2 solution. All strains were resuspended in 10 mM MgCl2 solution to a final absorbance of 0.1 (λ = 600). Then, 3.5 ml of this resuspension was added to 33.5 ml of M9 minimal medium broth supplemented with 0.5 mM thiamine and 1 mM nicotinic acid (M9TN medium) and 2 mM sorbitol as the carbon source. Cultures were grown at 28°C with rotary shaking at 150 rpm. Each strain population was quantified by serial dilution plating at 0 and 48 h after starting the culture (45, 46).

For the arginine auxotrophy tests, strains were grown overnight, pelleted, and resuspended in 10 mM MgCl2 solution to an absorbance of 0.1 (λ = 600) as described above. Then, 3.5 ml of this resuspension was added to 33.5 ml of M9TN with 2 mM sorbitol and 0.1 mg/ml arginine (Sigma-Aldrich). Cultures were grown at 28°C with rotary shaking at 150 rpm. Culture populations were quantified by serial dilution plating at 0 and 48 h after starting the culture.

Pathogenicity assay in apple trees.

Two-year-old, dormant, bare-rooted ‘Gala' apple trees with EMLA 26 rootstocks (Adams County Nursery, Aspers, PA) were potted and grown in a greenhouse for 7 weeks. Then, the trees were wound inoculated on actively growing shoot tips with the various E. amylovora strains at 1 × 108 CFU/ml in 10 mM MgCl2 solution, as described previously (47). Four trees were used for each strain, and five shoots were inoculated on each tree. The average size of the branches used was 41.4 cm (standard deviation, ± 6.62 cm). Each tree was inoculated with one strain only. Mock-inoculated shoots were wounded and treated with 10 mM MgCl2 solution. The entire experiment was performed twice, with similar results each time. The extent of shoot necrosis was measured at 7, 14, and 21 dpi. The extent of shoot necrosis, expressed as a percentage, was calculated by dividing the length of the necrotic portion of the shoot, measured from the shoot tip, by the total shoot length measured from the shoot tip to the shoot junction with the previous year's wood.

Quantitative growth analysis in immature apple and pear fruits.

Immature apple and pear fruits were collected at the Pennsylvania State University Fruit Research and Extension Center orchards in Biglerville, PA. Bacteria were suspended in 10 mM MgCl2 solution to an absorbance of 0.1 (λ = 600). Then, 20 μl of this cell suspension was introduced onto wounds on the skin side of halved immature ‘Gala' apple and ‘Bosc' pear fruits (46). Bacterial populations in the immature fruits were quantified at 0 and 7 dpi by macerating the apples in 10 mM MgCl2 solution, followed by serial dilution plating, and expressed as CFU per gram of plant tissue (36).

The nalidixic acid-resistant derivative of the wild-type E. amylovora HKN06P1 strain (HKN06P1NalR) (Table 1) was created by plating E. amylovora HKN06P1 from the −80°C glycerol stock on LB plates without antibiotics and growing them for 2 days at 28°C. Then, all the bacteria that had grown were spread evenly across LB plates supplemented with 25 μg/ml of nalidixic acid (Sigma-Aldrich). The resulting nalidixic acid-resistant colonies were tested for pathogenicity in immature apple fruit.

For mixed inoculations, the HKN06P1NalR and argD(1000)::Tn5 strains were separately suspended in 10 mM MgCl2 solution to an absorbance of 0.1 (λ = 600). Then, a 1:1 mixture was prepared and immature apple fruit halves were inoculated with 20 μl of the combination. The population densities were measured by serial dilution plating at 0 and 7 dpi. The serial dilutions were plated on LB medium supplemented with 25 μg/ml of nalidixic acid for selecting the HKN06P1NalR strain and on LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml of kanamycin for selecting the argD(1000)::Tn5 strain.

Plasmid stability assay in apple trees and immature apple fruits.

Inoculated apple tree shoots were collected at 21 dpi, and the bases of the shoots (2- to 3-cm segments) were surface disinfected with 50% bleach for 5 min, rinsed once with deionized water, and ground using a mortar and pestle. In the case of the apple fruit, at 7 dpi, the whole apple was ground in 1 ml of 10 mM MgCl2 solution. Extracts from apple tree shoots and apple fruits inoculated with E. amylovora argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) were plated on LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml of kanamycin and on LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml of kanamycin plus 100 μg/ml of carbenicillin. Extracts from apple trees and apple fruits inoculated with the HKN06P1NalR(pCR2.1) and HKN06P1NalR(PCR2.1-argD) strains (Table 1) were plated on LB medium supplemented with 25 μg/ml of nalidixic acid and on LB medium supplemented with 25 μg/ml of nalidixic acid plus 100 μg/ml of carbenicillin. The apple tree and apple fruit extracts were processed separately.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using PROC GLM in SAS (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The strains were analyzed as the independent variable, and the growth (log10 CFU) as the dependent variable. Post hoc comparisons were evaluated using the Tukey test, with α = 0.05. The standard errors of the means of three, four, or five replicate samples per strain were determined. The number of replicates varied depending on the assay.

RESULTS

Auxotrophy assays.

One of the nonpathogenic mutants that we identified had a Tn5 transposon insertion in the argD gene [denoted as argD(1000)::Tn5] (Fig. 1). The argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant was expected to be auxotrophic due to a disruption of the arginine biosynthesis pathway. As expected, the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant did not grow in M9 minimal medium supplemented with thiamine and nicotinic acid (M9TN medium) with sorbitol as the carbon source, while the wild-type E. amylovora grew in that medium (Fig. 2). Supplementation of M9 minimal medium with thiamine and nicotinic acid allows wild-type E. amylovora bacteria to grow by several orders of magnitude; in contrast, wild-type E. amylovora does not grow by even a single order of magnitude in M9 minimal medium in the absence of thiamine and nicotinic acid (23). Therefore, the use of M9TN medium allows for easier identification of auxotrophic E. amylovora mutants.

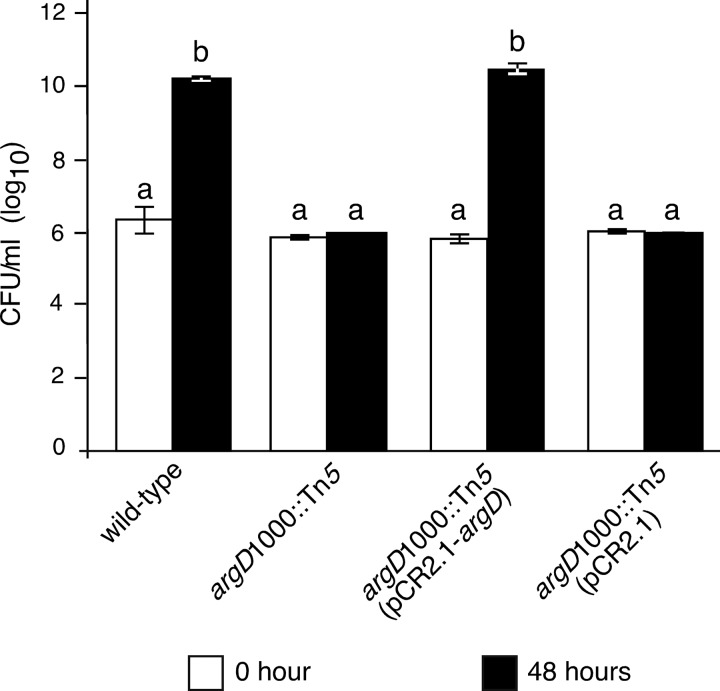

FIG 2.

Auxotrophy of the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant. Bacterial population densities of the indicated strains growing in M9 minimal medium supplemented with thiamine and nicotinic acid (M9TN medium) and with sorbitol as the carbon source were determined by serial dilution plating at 0 and 48 h after starting the culture. Values are the means of three replicates, and error bars represent standard errors; P = 0.05. Bars with the same letter have no statistically significant difference based on a Tukey test (log10). This experiment was performed three times, with similar results each time.

A genomic DNA (gDNA) segment that included the argD gene and parts of the flanking genes yhfK and pabA (Fig. 1A) was ligated into pCR2.1 to create plasmid pCR2.1-argD (Fig. 3). The pCR2.1 and pCR2.1-argD plasmids were introduced into the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant to create the argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1) and the argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) strain, respectively. The argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) strain grew in M9TN with sorbitol as the carbon source, while the argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1) strain did not grow in that medium (Fig. 2). The addition of arginine to the M9TN medium with sorbitol as the carbon source restored the growth of the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant (Fig. 4).

FIG 3.

Map of the pCR2.1-argD plasmid used to complement the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant. The wild-type argD complementation fragment (Fig. 1) was inserted with the direction of argD transcription opposite to that of the Plac promoter in pCR2.1. Unique restriction sites are indicated in boldface.

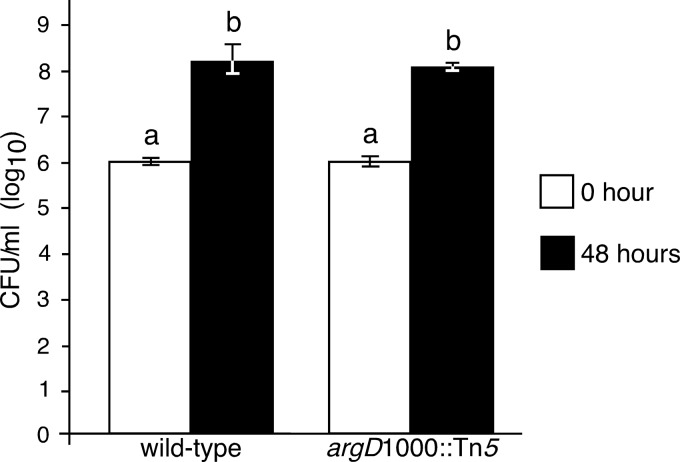

FIG 4.

Restoration of growth of the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant in minimal medium by the addition of arginine. Bacterial population densities of the indicated strains growing in M9 minimal medium supplemented with thiamine and nicotinic acid (M9TN medium) with sorbitol as the carbon source and supplemented with 0.1 mg/ml arginine were determined by serial dilution plating at 0 and 48 h after starting the culture. Values are the means of three replicates, and error bars represent standard errors; P = 0.05. There was no statistically significant difference between the wild type and the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant at any time point, according to a Tukey test (log10). This experiment was performed three times, with similar results each time.

Pathogenicity assays.

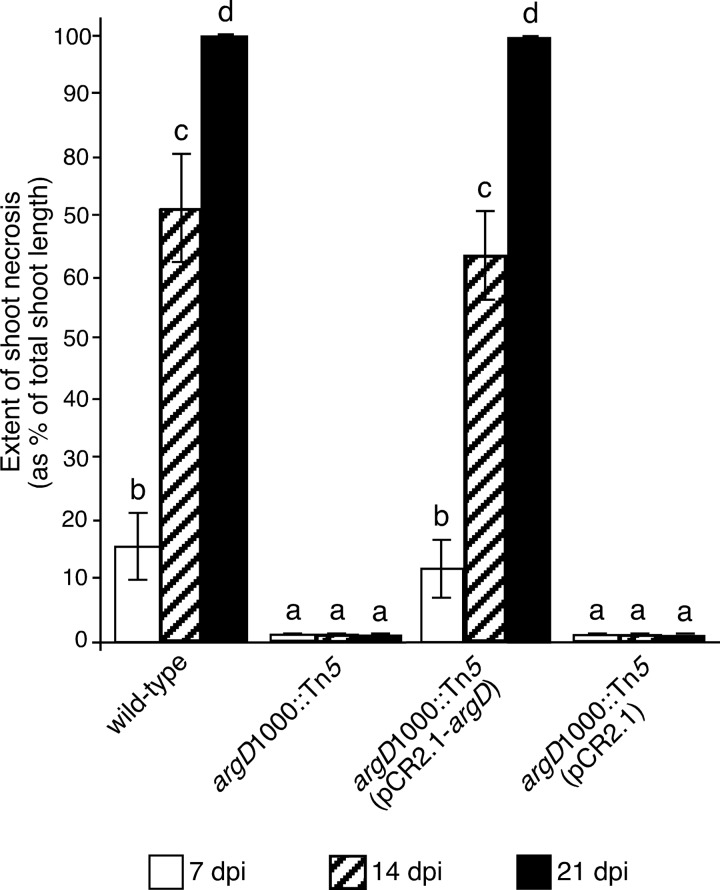

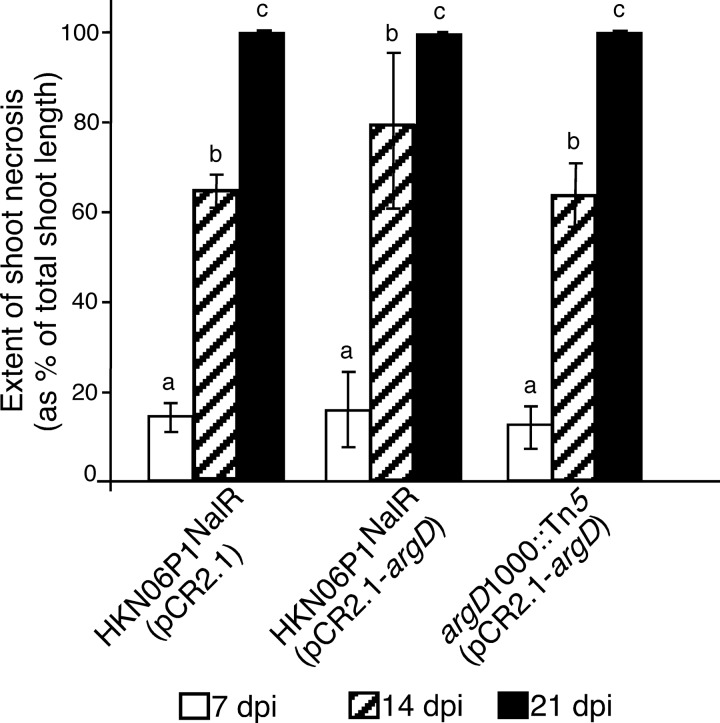

The argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant did not cause fire blight disease when inoculated onto apple trees by shoot tip wounding at 7, 14, or 21 dpi, while the wild-type strain caused extensive and progressive shoot necrosis (Fig. 5). Although a small amount of host tissue necrosis occurred at the argD(1000)::Tn5 inoculation sites, systemic symptom progression beyond the point of inoculation did not occur. The argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) strain caused progressive necrosis indistinguishable from that caused by the wild type, while the argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1) strain did not cause any progressive fire blight symptoms at any of the time points measured (Fig. 5). There was no statistically significant difference between the wild-type and the argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) strain or between the argD(1000)::Tn5 and argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1) strains, based on Tukey tests (log10).

FIG 5.

The argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant was not pathogenic in apple trees. Actively growing shoot tips were inoculated with the indicated E. amylovora strains at 108 CFU/ml by shoot tip wound inoculation. Values are the means of three replicates, and error bars represent standard errors; P = 0.05. Bars with the same letter have no statistically significant difference based on a Tukey test (log10). The entire experiment was performed twice, with similar results each time.

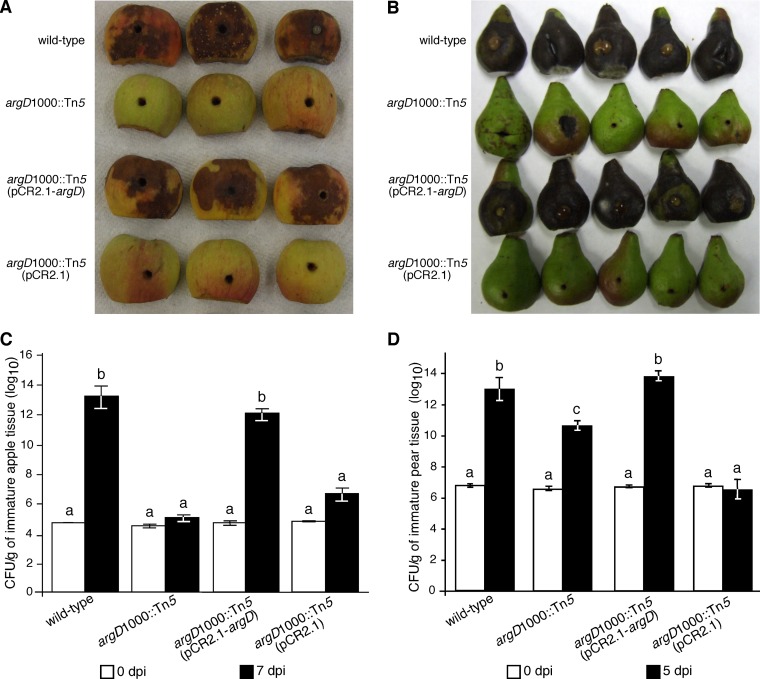

Similarly, the argD(1000)::Tn5 strain did not cause fire blight disease signs or symptoms when inoculated onto immature apple fruits at 7 dpi (Fig. 6A) and only occasionally caused minor necrosis on pear fruits at 5 dpi (Fig. 6B), while apple and pear fruits inoculated with wild-type E. amylovora exhibited extensive necrosis and frequently had bacterial ooze at 7 and 5 dpi, respectively (Fig. 6A and B). Furthermore, the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant failed to grow in immature apple fruits (Fig. 6C), while the wild-type E. amylovora bacterial population densities increased by about 8 orders of magnitude after 7 dpi. The argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant's population density grew by 4 orders of magnitude after 5 dpi in immature pear tissue, about 2 orders of magnitude less than the wild type (Fig. 6D).

FIG 6.

Pathogenicity assay and quantitative growth analysis in detached immature apple and pear fruit. (A) Immature ‘Gala' apple fruit halves at 7 days postinoculation (dpi) with the indicated bacterial strains. Tissue necrosis and bacterial ooze are a symptom and a sign, respectively, of fire blight disease in immature apple fruit. (B) Immature ‘Bosc' pear fruit halves at 5 dpi with the indicated bacterial strains. (C) Bacterial populations in immature ‘Gala' apple fruit halves at 7 dpi with the indicated bacterial strains, as determined by serial dilution plating. The same apples shown in panel A were used for the quantitative growth assay. (D) Bacterial populations in immature ‘Bosc' pear fruit halves at 5 dpi with the indicated bacterial strains. In panels C and D, values are the means of three replicates, and error bars represent standard errors; P = 0.05. Bars with the same letter have no statistically significant difference based on the Tukey test (log10). Experiments were performed at least three times with at least five immature apple and pear fruit halves inoculated per strain, with the same results each time.

The argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) strain caused necrosis and bacterial ooze on immature apple fruits at 7 dpi (Fig. 6A) and on immature pear fruits at 5 dpi (Fig. 6B), while the argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1) strain did not cause any fire blight symptoms (Fig. 6A and B). The argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) strain grew as well as the wild type in immature apple and pear fruit tissue, while the argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1) strain failed to grow in immature apple and pear fruit tissue (Fig. 6C and D). In immature apple fruits, there was no statistically significant difference between the wild-type and argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) population densities at 7 dpi or between the argD(1000)::Tn5 and argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1) population densities at 7 dpi, based on Tukey tests (log10) (Fig. 6C). In immature pear fruits, there was no statistically significant difference between the population densities of the wild-type and argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) strains at 5 dpi; however, there were statistically significant differences between the population densities of the wild-type and argD(1000)::Tn5 strains and those of the argD(1000)::Tn5 and argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1) strains at 5 dpi, based on Tukey tests (log10) (Fig. 6D).

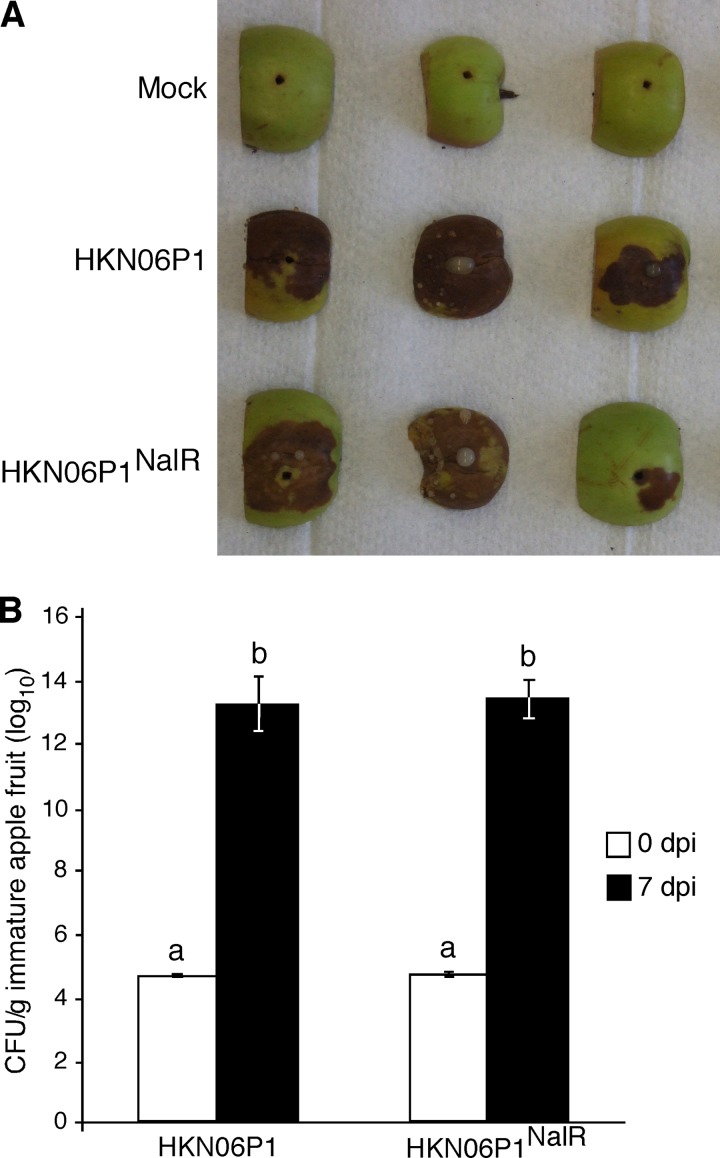

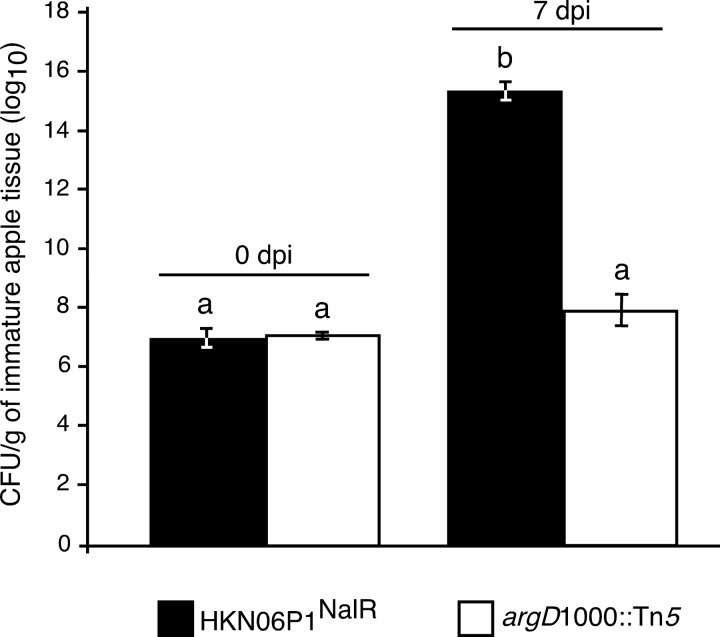

A nalidixic acid-resistant derivative of the wild-type E. amylovora HKN06P1 strain (denoted herein as HKN06P1NalR) was identified that produced symptoms similar to those caused by HKN06P1 (Fig. 7A) and grew as well as HKN06P1 (Fig. 7B) in immature apple fruit. When the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant was inoculated onto immature apple fruit in a 1:1 mixture with HKN06P1NalR, the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant did not grow, while HKN06P1NalR grew by 8 orders of magnitude after 7 dpi (Fig. 8).

FIG 7.

Fire blight symptoms and quantitative growth analysis in immature apple fruit inoculated with wild-type E. amylovora strain HKN06P1 and a nalidixic acid-resistant derivative (HKN06P1NalR). (A) Strains HKN06P1 and HKN06P1NalR produced similar fire blight symptoms in immature apple fruits at 7 days postinoculation (dpi). (B) Strains HKN06P1 and HKN06P1NalR grew to similar population densities at 7 dpi, as determined by serial dilution plating. Extracts from fruits inoculated with HKN06P1 were plated in LB medium without antibiotic selection, and extracts from fruits inoculated with HKN06P1NalR were plated on LB medium supplemented with 25 μg/ml nalidixic acid. The immature apple fruits shown in panel A were used for the quantitative growth analysis. Bars with the same letter have no statistically significant difference based on a Tukey test (log10).

FIG 8.

Bacterial growth in immature apple fruits after inoculation with a 1:1 mixture of HKN06P1NalR and the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant. Bacterial population densities were determined by serial dilution plating; HKN06P1NalR populations were determined by plating on LB medium supplemented with 25 μg/ml nalidixic acid, while argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant populations were determined by plating on LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin. Values are the means of four replicates, and error bars represent standard errors; P = 0.05. Bars with the same letter have no statistically significant difference based on a Tukey test (log10). The experiment was performed twice, with similar results each time.

Plasmid stability in planta.

The inability of the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant to grow in apple fruit tissue or cause disease symptoms in apple trees implied that an intact arginine biosynthesis pathway was required for E. amylovora to grow and cause disease in apples. This requirement appeared to be cell autonomous, since the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant did not grow when coinoculated with the pathogenic HKN06P1NalR strain (Fig. 8). Therefore, we hypothesized that the pCR2.1-argD plasmid would be stably maintained in the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant growing in planta.

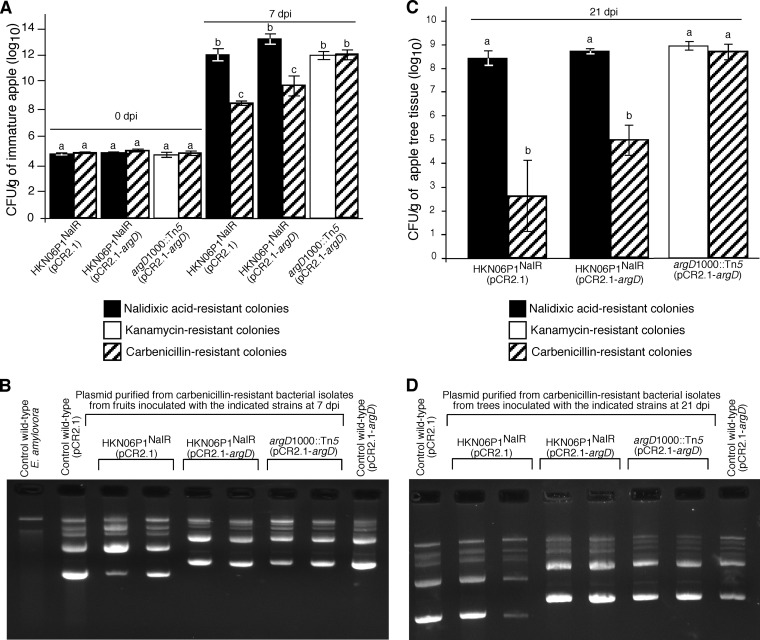

The pCR2.1 and pCR2.1-argD plasmids were introduced into HKN06P1NalR competent cells to produce the HKN06P1NalR(pCR2.1) and the HKN06P1NalR(pCR2.1-argD) strain, respectively. Immature apples were inoculated with the HKN06P1NalR(pCR2.1), HKN06P1NalR(pCR2.1-argD), and argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) strains. At 0 dpi, all three strains had similar population densities as determined by serial dilution plating of immature apple fruit extracts on LB medium supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics (Fig. 9A). At 7 dpi, the populations of nalidixic acid-resistant E. amylovora in immature apple fruits inoculated with the HKN06P1NalR(pCR2.1) and HKN06P1NalR(pCR2.1-argD) strains were the same as the populations of kanamycin-resistant E. amylovora growing in fruits inoculated with the argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) strain, indicating that all three strains were growing to the same population level. In contrast, at 7 dpi, the populations of carbenicillin-resistant E. amylovora in immature apple fruits inoculated with the HKN06P1NalR(pCR2.1) and HKN06P1NalR(pCR2.1-argD) strains were 3 to 4 orders of magnitude lower than the populations of carbenicillin-resistant E. amylovora growing in fruits inoculated with the argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) strain. Furthermore, the populations of kanamycin-resistant and carbenicillin-resistant E. amylovora in fruit inoculated with the argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) strain were equal (Fig. 9A). These results indicated that fewer than 0.1% of E. amylovora cells in fruits inoculated with the HKN06P1NalR(pCR2.1) and HKN06P1NalR(pCR2.1-argD) strains were resistant to carbenicillin after 7 days of growth in plant tissue. In contrast, the results indicate that 100% of E. amylovora cells in fruits inoculated with the argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) strain were resistant to carbenicillin after 7 days of growth in plant tissue. Plasmid preparations from randomly selected, carbenicillin-resistant E. amylovora colonies obtained during this analysis indicated that pCR2.1 and pCR2.1-argD were maintained as plasmids, as analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 9B).

FIG 9.

The pCR2.1-argD plasmid was stably maintained in the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant growing in planta. (A) Plasmid stability assay in immature apple fruits. Immature apple halves were inoculated with the indicated E. amylovora strains, and bacterial populations were determined at 0 and 7 days postinoculation (dpi) by serial dilution plating of the fruit extract on LB plates supplemented with kanamycin, carbenicillin, or nalidixic acid, as indicated. (B) Plasmid preparations from randomly selected carbenicillin-resistant isolates from the experiment whose results are shown in panel A were resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis. Plasmid preparations from wild-type strains carrying pCR2.1 and pCR2.1-argD which had not passed through plants served as controls. A plasmid preparation from wild-type E. amylovora carrying no foreign plasmids was also included. (C) Plasmid stability in apple trees inoculated with the indicated E. amylovora strains. ‘Gala' apple trees were inoculated by shoot tip wounding with the indicated E. amylovora strains, and bacterial populations were determined at 21 dpi by serial dilution plating of shoot tissue extract on LB plates supplemented with kanamycin, carbenicillin, or nalidixic acid, as indicated. (D) Plasmid preparations from randomly selected carbenicillin-resistant isolates from the experiment whose results are shown in panel C were resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis. Plasmid preparations from wild-type strains carrying pCR2.1 and pCR2.1-argD which had not passed through plants served as controls. In panels A and C, values are the means of three replicates, and error bars represent standard errors; P = 0.05. Bars with the same letter have no statistically significant difference based on a Tukey test (log10).

Similar results were obtained from plasmid stability assays in apple trees. ‘Gala' variety apple trees were inoculated by shoot tip wounding with the HKN06P1NalR(pCR2.1), HKN06P1NalR(pCR2.1-argD), and argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) strains, and each strain produced a similar progression of fire blight necrosis (Fig. 10). At 21 dpi, the populations of nalidixic acid-resistant E. amylovora in tissues from trees inoculated with the HKN06P1NalR(pCR2.1) and HKN06P1NalR(pCR2.1-argD) strains were the same as the populations of kanamycin-resistant E. amylovora growing in trees inoculated with argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) (Fig. 9C), indicating that all three strains grew similarly in the trees. In contrast, at 21 dpi, the populations of carbenicillin-resistant E. amylovora in tissues from trees inoculated with the HKN06P1NalR(pCR2.1) and HKN06P1NalR(pCR2.1-argD) strains were 3 to 5 orders of magnitude lower than the populations of carbenicillin-resistant E. amylovora growing in trees inoculated with the argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) strain (Fig. 9C). Moreover, the populations of kanamycin-resistant and carbenicillin-resistant E. amylovora in trees inoculated with the argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) strain were equal (Fig. 9C). These results indicated that fewer than 0.1% of E. amylovora cells in tissues of trees inoculated with the HKN06P1NalR(pCR2.1) and HKN06P1NalR(pCR2.1-argD) strains were resistant to carbenicillin at 21 dpi. In contrast, the results indicate that 100% of E. amylovora cells in tissues of trees inoculated with the argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) strain were resistant to carbenicillin at 21 dpi. Plasmid preparations from randomly selected carbenicillin-resistant E. amylovora colonies obtained during this analysis indicated that pCR2.1 and pCR2.1-argD were maintained as plasmids, as analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 9D).

FIG 10.

HKN06P1NalR(pCR2.1), HKN06P1NalR(pCR2.1-argD), and argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) strains caused similar fire blight disease progression in apple trees. Actively growing shoot tips of ‘Gala' apple trees were inoculated with the indicated E. amylovora strains at 108 CFU/ml by shoot tip wound inoculation. The extent of shoot necrosis at 7, 14, and 21 days postinoculation (dpi) is shown. Values are the means of three replicates, and error bars represent standard errors; P = 0.05. Bars with the same letter have no statistically significant difference based on a Tukey test (log10). The entire experiment was performed twice, with similar results each time.

DISCUSSION

The E. amylovora argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant was expected to be auxotrophic for arginine due to disruption of the arginine biosynthesis pathway. For example, disruption of the argD gene in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 and the bacterium Sinorhizobium meliloti Rmd201 caused an arginine auxotroph phenotype (48, 49). The argD(1000)::Tn5 strain did not grow in M9TN medium with sorbitol as the carbon source, which is consistent with the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant being an auxotroph. The addition of arginine to the M9TN medium with sorbitol as the carbon source restored the growth of the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant, showing that argD(1000)::Tn5 was indeed an arginine auxotroph. This result also suggests that the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant can transport arginine from the extracellular environment into the cell and use the extracellular arginine, despite having a disruption in the arginine biosynthesis pathway. Plasmid pCR2.1-argD restored the growth of the argD(1000)::Tn5 strain in M9TN medium with sorbitol as the carbon source, indicating that pCR2.1-argD complemented the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant's auxotrophic phenotype and confirming that the argD(1000)::Tn5 strain's auxotrophic phenotype was due to the Tn5 transposon insertion in the argD gene.

The inability of the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant to cause fire blight in apple trees and immature apple and pear fruits as the wild type does indicates that an intact arginine biosynthesis pathway is required for E. amylovora to survive and grow in the host and cause fire blight disease. The pCR2.1-argD plasmid complemented the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant's ability to cause fire blight in apple trees and immature apple fruits and restored normal growth in immature pear fruits, confirming that the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant's pathogenicity and virulence defects were due to the Tn5 transposon insertion in the argD gene.

The argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant failed to grow at all in immature apple fruits, which is consistent with the lack of symptoms in apple fruits and shoots inoculated with the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant. It is interesting to note that the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant grew by several orders of magnitude in immature pears, although this growth was 2 orders of magnitude lower than the growth of the wild type. This could be partly explained by the greater susceptibility of pears than of apples to fire blight overall (50) and possibly by the presence of more arginine in pear fruit than in apple. For example, a study of ‘Beurre' pear fruit and ‘Jonathan' apple fruit found that the pears contained approximately twice as much arginine as the apples (51).

The fact that the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant was able to transport and use extracellular arginine from the M9TN medium supplemented with sorbitol and arginine but was not able to cause fire blight symptoms in apple shoots or immature fruits, was not able to grow in immature apple fruit, and had greatly reduced growth in pear fruit tissues suggests that wild-type E. amylovora cells do not obtain sufficient arginine from the host during infection and must synthesize their own arginine; hence, the dependency on argD. This suggests either that the host tissues tested did not contain sufficient arginine to support normal E. amylovora growth or that E. amylovora cannot extract sufficient arginine from the host tissues tested to support normal growth.

The pCR2.1-argD plasmid appears to be stably maintained in E. amylovora argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) growing in planta. The populations of kanamycin-resistant and carbenicillin-resistant E. amylovora growing in immature apple fruits and apple trees inoculated with the argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) strain were the same, indicating that the argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) cells maintained the pCR2.1-argD plasmid over 7 dpi in immature apple fruit and 21 dpi in apple trees. The maintenance of the pCR2.1-argD plasmid in E. amylovora argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) growing in planta occurred without antibiotic selection and reflects a requirement for the arginine biosynthesis pathway for E. amylovora's growth in planta. Furthermore, these results imply that E. amylovora requires an intact arginine biosynthesis pathway even at stages of infection when severe symptoms and necrosis are evident, when host cellular contents are probably readily available to the pathogen. This supports the hypothesis that E. amylovora cannot acquire sufficient arginine for its needs from host tissue and must synthesize its own arginine in order to grow. This is further supported by the mixed-inoculum experiment, which indicates a cell-autonomous requirement for argD activity for E. amylovora's growth in the host. This situation contrasts with E. amylovora's iron acquisition requirements, for example. The siderophore-based, high-affinity iron acquisition of E. amylovora is required mainly for initial floral infection and epiphytic growth but not for infection through shoot wound sites or for systemic spread and necrosis in pear seedlings, when E. amylovora appears to be able to acquire sufficient iron through low-affinity uptake systems (52).

Furthermore, since the pCR2.1-argD plasmid was very stable in the argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) strain, the pCR2.1-argD plasmid could be a useful new tool for fire blight research, given its antibiotic-free selection in E. amylovora argD(1000)::Tn5(pCR2.1-argD) growing in planta. The pCR2.1-argD plasmid could be used to express genes of interest and study them in planta without losing the plasmid over time because of no antibiotic selection. Plasmid loss from plant pathogens growing in planta due to lack of antibiotic selection is commonly observed (53–55). Lastly, there has been some interest in using ArgD as an antibiotic target in bacteria (56). However, arginine biosynthesis is a highly conserved pathway (37–42, 57, 58), which limits its utility as an antibiotic target.

In summary, this study indicates that E. amylovora cannot obtain sufficient arginine from host tissues, either at the beginning of infection or later when the disease is in an advanced state. This would explain why E. amylovora needs an intact arginine biosynthesis pathway to cause fire blight disease in apple trees and immature apple and pear fruits and why the pCR2.1-argD complementation plasmid was stably maintained in the argD(1000)::Tn5 mutant growing in apple fruits and apple trees in the absence of antibiotic selection. Although the ArgD protein is not specifically involved in E. amylovora's virulence and, therefore, cannot be considered an E. amylovora virulence factor, the results presented here provide new insight into the parasitic interaction of E. amylovora with the host. Finally, the pCR2.1-argD plasmid could be a useful new tool for fire blight research for expressing genes in E. amylovora growing in planta.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Steven A. Lee for creating the E. amylovora Tn5 mutant library that we screened.

L.S.R. was supported in part by a Bunton Waller Graduate Fellowship, an Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Graduate Scholarship, a grant from the Pennsylvania State University College of Agricultural Sciences Graduate Student Competitive Grant Program, grant number 2010-65110-20488 from the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Competitive Grants Program of the United States Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture, and the Department of Plant Pathology and Environmental Microbiology at The Pennsylvania State University. This research was also supported in part by funding from the Sarah Chinn Kalser Faculty Research Assistance Endowment of the Pennsylvania State University (T.W.M).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 29 August 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Burrill TJ. 1880. Anthrax of fruit trees; or the so-called fire blight of pear, and twig blight of apple trees. Am. Assoc. Adv. Sci. Proc. 29:583–597. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arthur JC. 1885. Proof that bacteria are the direct cause of the disease in trees known as pear blight. Am. Assoc. Adv. Sci. Proc. 34:294–298. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santander RD, Oliver JD, Biosca EG. 2014. Cellular, physiological, and molecular adaptive responses of Erwinia amylovora to starvation. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 88:258–271. 10.1111/1574-6941.12290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coxe W. 1817. A view of the cultivation of fruit trees, and the management of orchards and cider. M. Carey & Son, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Momol MT, Yegen O. 1993. Fire blight in Turkey: 1985-1992. Acta Hort. 338:37–39. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zilberstaine M, Herzog Z, Manulis S, Zutra D. 1996. Outbreak of fire blight threatening the loquat industry in Israel. Acta Hort. 411:177–178. [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Zwet T, Keil HL. 1979. Fire blight—a bacterial disease of Rosaceous plants. Agriculture Handbook 510 U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denning W. 1794. On the decay of apple trees. Trans. Soc. Promot. Agric. Arts Manuf. 1:219–222. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonn WG. 1999. Opening address. Acta Hort. 489:27–28. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norelli JL, Jones AL, Aldwinckle HS. 2003. Fire blight management in the twenty-first century: using new technologies that enhance host resistance in apple. Plant Dis. 87:756–765. 10.1094/PDIS.2003.87.7.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vanneste JL. 2000. Fire blight: the disease and its causative agent, Erwinia amylovora. CABI Publishing, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bugert P, Geider K. 1995. Molecular analysis of the ams operon required for exopolysaccharide synthesis of Erwinia amylovora. Mol. Microbiol. 15:917–933. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wei ZM, Beer SV. 1995. hrpL activates Erwinia amylovora hrp gene transcription and is a member of the ECF subfamily of σ factors. J. Bacteriol. 177:6201–6210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim JF, Wei ZM, Beer SV. 1997. The hrpA and hrpC operons of Erwinia amylovora encode components of a type III pathway that secretes harpin. J. Bacteriol. 179:1690–1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei ZM, Laby RJ, Zumoff CH, Bauer DW, He SY, Collmer A, Beer SV. 1992. Harpin, elicitor of the hypersensitive response produced by the plant pathogen Erwinia amylovora. Science 257:85–88. 10.1126/science.1621099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaudriault S, Brisset MN, Barny MA. 1998. HrpW of Erwinia amylovora, a new Hrp-secreted protein. FEBS Lett. 428:224–228. 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00534-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim JF, Beer SV. 1998. HrpW of Erwinia amylovora, a new harpin that contains a domain homologous to pectate lyases of a distinct class. J. Bacteriol. 180:5203–5210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaudriault S, Malandrin L, Paulin JP, Barny MA. 1997. DspA, an essential pathogenicity factor of Erwinia amylovora showing homology with AvrE of Pseudomonas syringae, is secreted via the Hrp secretion pathway in a DspB-dependent way. Mol. Microbiol. 26:1057–1069. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6442015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bogdanove AJ, Bauer DW, Beer SV. 1998. Erwinia amylovora secretes DspE, a pathogenicity factor and functional AvrE homolog, through the hrp (type III secretion) pathway. J. Bacteriol. 180:2244–2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bocsanczy A, Nissinen R, Oh C, Beer S. 2008. HrpN of Erwinia amylovora functions in the translocation of DspA/E into plant cells. Mol. Plant Pathol. 9:425–434. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2008.00471.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rezzonico F, Duffy B. 2007. The role of luxS in the fire blight pathogen Erwinia amylovora is limited to metabolism and does not involve quorum sensing. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 20:1284–1297. 10.1094/MPMI-20-10-1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang D, Korban S, Zhao Y. 2009. The Rcs phosphorelay system is essential for pathogenicity in Erwinia amylovora. Mol. Plant Pathol. 10:277–290. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2008.00531.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramos LS, Lehman BL, Sinn JP, Pfeufer EE, Halbrendt NO, McNellis TW. 2013. The fire blight pathogen Erwinia amylovora requires the rpoN gene for pathogenicity in apple. Mol. Plant Pathol. 14:838–843. 10.1111/mpp.12045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ancona V, Li W, Zhao Y. 2014. Alternative sigma factor RpoN and its modulation protein YhbH are indispensable for Erwinia amylovora virulence. Mol. Plant Pathol. 15:58–66. 10.1111/mpp.12065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berry M, McGhee G, Zhao Y, Sundin G. 2009. Effect of a waaL mutation on lipopolysaccharide composition, oxidative stress survival, and virulence in Erwinia amylovora. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 291:80–87. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hildebrand M, Aldridge P, Geider K. 2006. Characterization of hns genes from Erwinia amylovora. Mol. Gen. Genomics 275:310–319. 10.1007/s00438-005-0085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang F, Korban S, Pusey L, Elofsson M, Sundin G, Zhao Y. 2014. Small-molecule inhibitors suppress the expression of both type III secretion and amylovoran biosynthesis genes in Erwinia amylovora. Mol. Plant Pathol. 15:44–57. 10.1111/mpp.12064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dunegan JC, Kienholz JR, Wilson RA, Morris WT. 1954. Control of pear blight by a streptomycin–terramycin mixture. Plant Dis. Rep. 38:666–669. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodman RN. 1954. Fire blight control with sprays of agri-mycin, a streptomycin–terramycin combination. Plant Dis. Rep. 38:874–878. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morgan BS, Goodman RN. 1955. In vitro sensitivity of plant bacterial pathogens to antibiotics and antibacterial substances. Plant Dis. Rep. 39:487–490. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaffer WH, Goodman RN. 1969. Effectiveness of an extended agri-mycin-17 spray schedule against fire blight. Plant Dis. Rep. 53:669–672. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McManus PS, Stockwell VO, Sundin GW, Jones AL. 2002. Antibiotic use in plant agriculture. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 40:443–465. 10.1146/annurev.phyto.40.120301.093927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moller WJ, Schroth MN, Thomson SV. 1981. The scenario of fire blight and streptomycin resistance. Plant Dis. 65:563–568. 10.1094/PD-65-563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sholberg PL, Bedford KE, Haag P, Randall P. 2001. Survey of Erwinia amylovora isolates from British Columbia for resistance to bactericides and virulence on apple. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 23:60–67. 10.1080/07060660109506910. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ponce de León Door A, Romo Chacón A, Acosta Muñiz C. 2013. Detection of streptomycin resistance in Erwinia amylovora strains isolated from apple orchards in Chihuaha, Mexico. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 137:223–229. 10.1007/s10658-013-0241-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee S, Ngugi K, Halbrendt N, O'keefe G, Lehman B, Travis J, Sinn J, McNellis T. 2010. Virulence characteristics accounting for fire blight disease severity in apples trees and seedlings. Phytopathology 100:539–550. 10.1094/PHYTO-100-6-0539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakanyan V, Kochikyan A, Mett I, Legrain C, Charlier D, Piérard A, Glansdorff N. 1992. A re-examination of the pathway for ornithine biosynthesis in a thermophilic and two mesophilic Bacillus species. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138:125–130. 10.1099/00221287-138-1-125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riley M, Glansdorff N. 1983. Cloning the Escherichia coli K-12 argD gene specifying acetylornithine δ-transaminase. Gene 24:335–339. 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90095-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ledwidge R, Blanchard J. 1999. The dual biosynthesis capability of N-acetylornithine aminotransferase in arginine and lysine biosynthesis. Biochemistry 38:3019–3024. 10.1021/bi982574a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qu Q, Morizono H, Shi D, Tuchman M, Caldovic L. 2007. A novel bifunctional N-acetylglutamate synthase-kinase from Xanthomonas campestris that is closely related to mammalian N-acetylglutamate synthase. BMC Biochem. 8:4. 10.1186/1471-2091-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hartmann M, Tauch A, Eggeling L, Bathe B, Möckel B, Pühler A, Kalinowski J. 2003. Identification and characterization of the last two unknown genes, dapC and dapF, in the succinylase branch of the L-lysine biosynthesis of Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Biotechnol. 104:199–211. 10.1016/S0168-1656(03)00156-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodríguez-García A, de la Fuente A, Pérez-Redondo R, Martín J, Liras P. 2000. Characterization and expression of the arginine biosynthesis gene cluster of Streptomyces clavuligerus. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2:543–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smits TH, Rezzonico F, Kamber T, Blom J, Goesmann A, Frey JE, Duffy B. 2010. Complete genome sequence of the fire blight pathogen Erwinia amylovora CFBP 1430 and comparison to other Erwinia spp. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 23:384–393. 10.1094/MPMI-23-4-0384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403–410. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sinn JP, Oh CS, Jensen PJ, Carpenter SCD, Beer SV, McNellis TW. 2008. The C-terminal half of the HrpN virulence protein of the fire blight pathogen Erwinia amylovora is essential for its secretion and for its virulence and avirulence activities. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 21:1387–1397. 10.1094/MPMI-21-11-1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jensen P, Rytter J, Detwiler DA, Travis JW, McNellis TW. 2003. Rootstock effects on gene expression patterns in apple tree scions. Plant Mol. Biol. 53:493–511. 10.1023/B:PLAN.0000019122.90956.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Floriano B, Herrero A, Flores E. 1994. Analysis of expression of the argC and argD genes in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J. Bacteriol. 176:6397–6401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kumar A, Vij N, Randhawa G. 2003. Isolation and symbiotic characterization of transposon Tn5-induced auxotroph of Sinorhizobium meliloti. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 41:1198–1204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thompson SV, Ockey SC. 2000. Fire blight of pears and apples. Utah Plant Disease Control no. 27. Utah State University Extension, Logan, UT: http://extension.usu.edu/files/factsheets/Disease%20027%20UPDC%20Fire%20blight.PDF. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pilipenko LN, Kalinkov AY, Spektor AV. 1999. Amino acid composition of fruit in the manufacture of sedimentation-stabilized dispersed products. Chem. Nat. Compd. 35:208–211. 10.1007/BF02234937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dellagi A, Brisset MN, Paulin JP, Expert D. 1998. Dual role of desferrioxamine in Erwinia amylovora pathogenicity. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 11:734–742. 10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.8.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hasnain S, Sherwani SK. 1994. Some physicochemical factor affecting plasmid stability. Pak. J. Agric. Res. 15:221–232. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boe L, Gerdes K, Molin S. 1987. Effects of genes exerting growth inhibition and plasmid stability on plasmid maintenance. J. Bacteriol. 169:4646–4650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith MA, Bidochka MJ. 1998. Bacterial fitness and plasmid loss: the importance of culture conditions and plasmid size. Can. J. Microbiol. 44:351–355. 10.1139/w98-020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rajaram V, Ratna Prasuna P, Savithri HS, Murthy MRN. 2008. Structure of biosynthesic N-acetylornithine aminotransferase from Salmonella typhimurium: studies on substrate specificity and inhibitor binding. Proteins 70:429–441. 10.1002/prot.21567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Slocum R. 2005. Genes, enzymes and regulation of arginine biosynthesis in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 43:729–745. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu Y, Labedan B, Glansdorff N. 2007. Surprising arginine biosynthesis: a reappraisal of the enzymology and evolution of the pathway in microorganisms. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 71:36–47. 10.1128/MMBR.00032-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]