Abstract

Biofilms are major causes of impairment of wound healing and patient morbidity. One of the most common and aggressive wound pathogens is Staphylococcus aureus, displaying a large repertoire of virulence factors and commonly reduced susceptibility to antibiotics, such as the spread of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). Bacteriophages are obligate parasites of bacteria. They multiply intracellularly and lyse their bacterial host, releasing their progeny. We isolated a novel phage, DRA88, which has a broad host range among S. aureus bacteria. Morphologically, the phage belongs to the Myoviridae family and comprises a large double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) genome of 141,907 bp. DRA88 was mixed with phage K to produce a high-titer mixture that showed strong lytic activity against a wide range of S. aureus isolates, including representatives of the major international MRSA clones and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus. Its efficacy was assessed both in planktonic cultures and when treating established biofilms produced by three different biofilm-producing S. aureus isolates. A significant reduction of biofilm biomass over 48 h of treatment was recorded in all cases. The phage mixture may form the basis of an effective treatment for infections caused by S. aureus biofilms.

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus is an opportunistic human bacterial pathogen that primarily colonizes the anterior nares (1) but is frequently shed onto skin surfaces. When an opportunity occurs that facilitates its penetration of the skin surface, it is able to cause a broad spectrum of human diseases, from skin and soft tissue infections to systemic infections such as pneumonia, meningitis, and osteomyelitis (1, 2). Host invasion and immune evasion are possible due to a myriad of virulence factors, including toxins, adhesins, and evasins (3). In addition, S. aureus infections often comprise strains with antibiotic resistance. Examples of these are penicillin- and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and isolates with decreased susceptibility to vancomycin (4).

S. aureus is one of the most common Gram-positive causes of wound infections (5, 6). The wound environment is an ideal one for establishment of a bacterial infection as it contains large aggregations of necrotic tissue and accumulations of protein exudate (7). It is also observed that wound infections are strongly associated with the formation of biofilm communities (8). Once in a biofilm, bacterial cells experience greater protection against antibiotics and against elements of the host immune system than do cells growing in a planktonic state (9). For example, the exopolysaccharide matrix blocks antibody penetration into biofilm (10) and phagocytes are unable to interact with bacterial cells (11). Biofilm structures are believed to be present in many acute wounds but are very common in chronic wounds (12) and are a major factor delaying wound healing (12, 13). Moreover, many biofilms colonize implanted medical devices (14), greatly increasing patient morbidity and mortality, and they are associated with higher health care costs (15). Chronic wounds affect 6.5 million patients in the United States, and more than US$25 billion is spent every year on treatment (16).

Current antibiotic options to successfully treat S. aureus are becoming scarce despite the development of some novel drugs (17), and there is a growing need for effective agents to combat infections (18). Bacteriophage therapy is a viable alternative/adjunct to antibiotics in treating bacterial infection (for a review, see reference 19). Bacteriophages (phages) are viruses able to infect highly specifically and kill the bacterial species targeted but not eukaryotic cells. The phage-encoded lysis proteins—endolysin and holin—cause the breakdown of the bacterial membrane (20), resulting in cell death and release of phage particles.

Several studies have shown the potential of using phages to treat S. aureus infections (21–23), and it has been demonstrated that phages also have the ability to disrupt bacterial biofilms (24). Phages are increasingly recognized as serious candidates in the fight against antibiotic-resistant bacteria in human therapeutics and as prophylaxis (25). Phages with strictly lytic life cycles, which result in a rapid killing of the target host and diminish the chances for bacteria to evolve toward phage resistance, are preferred for bacteriophage therapy use (26). It is also of value for the phage (or phage mixture) used to have a polyvalent nature, i.e., to be able to infect a large set of strains within a species, and such a phage may show improved applicability in situations where the etiological agent of an infectious disease has not been identified.

Here, we investigate the potential of using two lytic and polyvalent S. aureus phages: K, a well-documented staphylococcal phage (27–29) that attaches specifically to the cell wall teichoic acid (30), providing a wide host range, and a newly isolated phage, DRA88. Phage K was previously shown to be able to disrupt biofilms produced by S. aureus strains (28). Here, we characterized the antimicrobial activity of the phages alone and in combination in planktonic and biofilm systems.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and growth conditions.

S. aureus strains (listed in Table 1) used in this study were from our collection of >5,000 clinical isolates, and they were selected to be genetically diverse (by multilocus sequence typing [MLST] [31]) and also to contain members of the major MRSA and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) clones present worldwide. Examples of eight coagulase-negative staphylococci, S. xylosus, S. sciuri subsp. sciuri, S. chromogenes, S. hyicus, S. arlettae, S. vitulinus, S. simulans, and S. epidermidis, were also included in this study. Bacteria from 5% (vol/vol) blood agar plates were grown at 37°C with constant shaking (170 rpm) in tryptic soy broth (TSB). Tryptic soy agar (TSA) and TSB-soft agar containing 0.65% bacteriological agar were used for bacteriophage propagation and plaque count assays. Note that medium was supplemented with 1 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM MgSO4 to improve phage adsorption (32). Bacterial aliquots were stocked at −80°C in broth containing 15% (vol/vol) glycerol.

TABLE 1.

Sensitivity screening of phage mixture against 95 S. aureus isolatesa

Bacterial isolates were susceptible (clear spot; S; light gray), intermediate (turbid spot; I; medium gray), or resistant (no disturbance of bacterial lawn; R; dark gray) to phage infection. ST, sequence type.

Bacteriophage isolation.

Bacteriophages were isolated from crude sewage (Thames Water PLC, Luton, United Kingdom). Bacterial enrichments with S. aureus isolates were performed to increase phage numbers as follows: 5 ml of actively growing S. aureus cells (from overnight liquid culture in TSB) and TSB supplemented with 1 mM MgSO4 and 1 mM CaCl2. The enrichment was incubated overnight at 37°C. A 10-ml aliquot was taken from the overnight culture, and 1 M NaCl and 0.2% chloroform were added. The culture was then centrifuged (30 min, 3,000 × g) to remove bacteria, and the supernatant was filtered-sterilized (0.22-μm pore size; Millipore filter). This lysate (supernatant) was used to check the presence of lytic phages using the double layer method as described previously (33). Isolated single plaques were picked into SM buffer (5 M NaCl, 1 M MgSO4, 1 M Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 0.01% (wt/vol) gelatin in distilled water [dH2O]), and successive rounds of single plaque purification were carried out until purified plaques were obtained, reflected by single plaque morphology. Purified phages were stored in 50% (vol/vol) glycerol at −80°C for long-term use. Short-term stock preparations were maintained at 4°C.

Bacteriophage propagation.

Phage lysates were propagated on their respective bacterial hosts. Briefly, 100 μl of phage lysate and 100 μl of host growing culture were mixed and left for 5 min at room temperature. Afterward, 3 ml of soft agar was added and poured onto TSA plates. The following day, after an overnight incubation at 37°C, plates displaying confluent lysis were selected and 3 ml of SM buffer and 2% (vol/vol) chloroform were added before incubation at 37°C for 4 h. High-titer phage solution was removed from the plates, centrifuged (8,000 × g, 10 min) to remove cell debris, and then filter sterilized (pore size, 0.22 μm) and stored at 4°C. Both phages were propagated in the prophage-free isolate S. aureus RN4220 (34) to avoid potential contamination with mobilized phages (35).

Sensitivity assay.

To determine phage sensitivity of bacterial isolates, spot tests were performed. Briefly, 3 ml of TSB-soft agar was added to 100 μl of host growing culture and poured onto TSA. Plates were left to dry for 20 min at 37°C. The different phage lysates were standardized to a titer of 109 PFU/ml, and 10 μl of each lysate was spotted onto the bacterial lawns. This assay was performed in triplicate. The plates were allowed to dry before incubation overnight at 37°C. The following day, the sensitivity profiles of each of the bacterial strains were determined: if the bacterial lawn was lysed, slightly disrupted, or not disrupted, the bacterial isolate was labeled sensitive, intermediate, or resistant to the phage infection, respectively.

Bacteriophage adsorption.

The experiment was carried out at 37°C under constant shaking (60 rpm) and a phage inoculum with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01. The number of free phages was calculated from the PFU of chloroform-treated samples within 5 min after inoculation. The adsorption rate, assuming a first-order kinetics, was calculated in terms of the percentage of free phage loss by fitting the phage decay curve (normalized as a percentage) to the rate equation:

| (1) |

where k′ is the pseudo-first rate constant for free phage loss:

| (2) |

From this, the percent phage remaining at any time t can be easily calculated.

One-step growth curve.

Phage growth cycle parameters—the latent period (L), eclipse period (E), and burst size (B)—were determined from the dynamical change of the number of free and total phages. Hence, one-step growth curves were measured as described by Pajunen et al. (36) with some modifications: 10 ml of a mid-exponential-phase culture was harvested by centrifugation (7,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C) and resuspended in 5 ml TSB to obtain an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0. To this suspension, 5 ml of phage solution was added to obtain a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.001. Phages were allowed to adsorb for 5 min at room temperature. The mixture was than centrifuged as described above, and the pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of fresh TSB medium. Two samples were taken every 5 min over a period of 1 h at 37°C under constant shaking. The first samples were plated immediately without any treatment, and the second set of samples was plated after treatment with 1% (vol/vol) chloroform to release intracellular phages.

Measurement of phage zeta potential and size.

The particle size and electrophoretic mobility of the phages were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a Zetasizer Z/S system (Malvern, United Kingdom) at 37°C. Cuvettes filled with the sample were carefully inspected to avoid air bubbles. Phages were diluted in distilled water (dH2O) to a final concentration of 108 PFU ml−1. Measurements were repeated at least three times.

Electron microscopy.

Phage particles in water were deposited on carbon-coated copper grids and negatively stained with 1% uranyl acetate (pH 4). Visualization was performed using a transmission electron microscope (TEM) (JEM1200EXII; JEOL, Bath, United Kingdom) operated at 120 kV.

Phage DNA extraction.

Concentrated phage preparations were obtained by a cesium chloride (CsCl) (Sigma, United Kingdom) gradient composed of three different solutions with densities of 1.35, 1.50, and 1.7 g ml−1. They were prepared in a 36.5-ml ultracentrifuge tube (Beckman Coulter, Seton Scientific, United Kingdom). For the preparation of CsCl solution at a given density, ρ (g ml−1), the following equation was used to calculate the final CsCl concentration, c (g ml−1): c = 0.0478ρ2 + 1.23ρ − 1.27. The protocol described previously by Boulanger (37) was also used. After ultracentrifugation for 3 h (75,600 × g at 4°C), the phage band was collected and dialysis was performed to remove CsCl residuals. Briefly, phage suspension was washed into dialysis cassettes (Slide-A-Lyser; Fisher, United Kingdom), which in turn were introduced in 500 volumes of dialysis buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7) for 30 min. After the process was performed three times, the concentrated and purified phage suspension was collected. Phenol-chloroform extraction was performed according to the method in reference 38. A 1.8-ml amount of phage lysates was treated with 18 μl DNase I (1 mg ml−1) (Sigma-Aldrich) and 8 μl RNase A (10 mg ml−1) (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated at 37°C for 60 min. Subsequently, 18 μl proteinase K (10 mg ml−1) (Sigma-Aldrich), 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 1 mM EDTA-Na2 were added to the samples, and these were incubated at 65°C for a further 60 min. All protein material was eliminated by using phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) (Sigma-Aldrich), and DNA extraction and precipitation were performed as described previously elsewhere (39). Nucleic acid concentration and quality were assessed with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, United Kingdom).

DNA sequencing, analysis, and assembly.

DNA sequencing libraries were prepared using the Nextera XT DNA kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Individually tagged libraries were sequenced as a part of a flow cell as 2- by 250-base paired-end reads using the Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) at The Danish National High-Throughput DNA-Sequencing Centre. Reads were analyzed, trimmed, and assembled using 6.5.1 CLC Genomic Workbench as described before by Kot et al. (40). Genes were predicted and annotated using the RAST server (34).

Planktonic cultures treated with phage mixture.

Planktonic cultures were performed in 96-well microtiter plates, and their optical density was measured. In summary, a 1:100 dilution was prepared in the wells of the microplate by adding 2 μl of an overnight culture to 198 μl of TSB. After 2 h of incubation at 37°C, the single or mixed phage at an MOI of 0.1 was added and the microplates were incubated for a further 22 h. The incubation was followed on a plate reader (FLUOstar Omega; BMG LabTech, United Kingdom) where the growth curves were established at an optical density at 590 nm (OD590). This approach allows observation of the phage-bacterium interaction over time and also allows for monitoring of the appearance of resistant mutants for each phage lysate.

Biofilm formation.

The biofilm assay was performed similarly to previously described methods (41) but with some modifications in order to optimize the system. Biofilm formation was performed in 96-well polystyrene tissue culture microplates (Nunclon Delta Surface; Nunc, United Kingdom) to achieve an improved cell attachment. TSB supplemented with 1% d-(+)-glucose (TSBg) and 1% NaCl (TSBg-NaCl) was used to perform this assay, as this helps to improve biofilm formation (38, 39). An overnight culture was diluted to a titer of 108 CFU ml−1. Briefly, in the microplate wells a 1:100 dilution was performed by adding 2 μl of the bacterial suspension to 198 μl of TSBg-NaCl, making a starting inoculum of 106 CFU ml−1. Two hundred microliters of broth was added to a set of wells as a negative control. All wells were replicated three times. Afterwards, microplates were incubated at 37°C for 48 h with no shaking for biofilm formation. During the incubation time (∼24 h after incubation), 50 μl of fresh TSBg-NaCl was added to all control and test wells. Following incubation, medium was poured off and wells were carefully washed twice with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution (Sigma-Aldrich, United Kingdom) to remove any planktonic cells. Microplates were allowed to dry for 1 h at 50°C. To determine total biofilm biomass, microplate wells were stained with 0.1% crystal violet (CV). After staining, the wells were washed twice with PBS solution and dried. Biofilm formation was determined by visual comparison of the stained wells and photographed.

Biofilm treatment with phage mixture.

Biofilm formation was carried out as described above. Once biofilms were established and washed once with PBS, 100 μl of phage mixture in PBS was added to a set of wells. Two different MOIs were set up for the single or mixed phage, 1 and 10. One hundred microliters of PBS was added to both the isolate-positive and -negative controls. All the experiments were performed three times. After static incubation at 37°C, microplates were washed and stained, as described before, at predetermined time points. To perform optical density readings of the staining intensity, 100 μl of 95% (vol/vol) ethanol was added to each well and optical density at 590 nm (OD590) was measured using a plate reader.

Data analysis.

Comparisons between the different time points and the positive controls were made by performing Student's t test, and a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all cases. All tests were performed with a confidence level of 95%. Spread of data at the 95% confidence interval (CI) was estimated using the Winpepi freeware statistical analysis program (42).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The genome sequence of phage DRA88 has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession number KJ888149.

RESULTS

Isolation and host range determination.

Several lytic phages were isolated in crude sewage samples from a water treatment facility and tested against the S. aureus bacterial collection listed in Table 1 in order to isolate phages with broad host ranges. One phage, DRA88, presented a host infectivity coverage of 60.0% (95% CI, 50% to 69%; 57 isolates out of 95 were susceptible) and so was selected for further studies. Phage K was also tested and showed host coverage of 64.2% (95% CI, 54% to 73%; 61 isolates out of 95 were susceptible). These two phages were mixed in a phage mixture, giving a total coverage of 73.7% (95% CI, 64% to 82%) of the S. aureus isolates assigned to 14 different multilocus sequence typing (MLST) types. Infectivity of both phages was also tested on a group of coagulase-negative isolates, where DRA88 did not kill efficiently any of the isolates. Phage K also showed weak infectivity; however, two of the isolates (S. simulans and S. hyicus) were sensitive (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Sensitivity screening of phage mixture against coagulase-negative staphylococcus isolatesa

Bacterial isolates were susceptible (clear spot; S; light gray), intermediate (turbid spot; I; medium gray), or resistant (no disturbance of bacterial lawn; R; dark gray) to phage infection.

Phage growth characteristics.

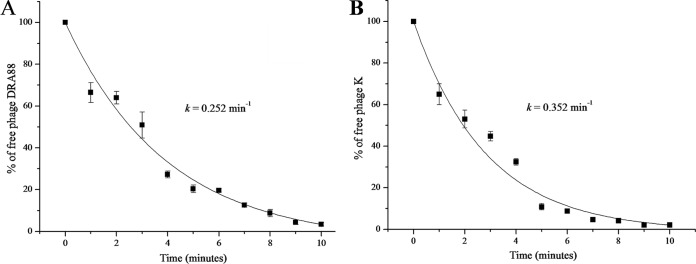

The life cycle and adsorption affinity of phage DRA88 and phage K were assessed when growing in the RN4220 S. aureus host at 37°C. First, one-step growth studies were performed to identify the different phases of a phage infection process. After infection, phage growth cycle parameters (L, latent; E, eclipse; B, burst size) were determined (Fig. 1). In the system established, the eclipse and latent periods of DRA88 were 15 min and 25 min, respectively. DRA88 yielded a burst size of 76 PFU and phage K yielded a burst size of 125 PFU per infected cell after 60 min. These phage life cycle values are in conformity with the values normally observed for T7 group phages (43). The adsorption efficiency of phages to the host was estimated with cells in the early logarithmic growth phase (Fig. 2). From equation 1, the rate constants for the adsorption (loss of free phage) for phage K and DRA88 were calculated (Fig. 2), k′ = 0.352 min−1 and k′ = 0.252 min−1, respectively. Hence, although the phages were similar, after 5 min, 80.3% of phage K and 71.6% of DRA88 were adsorbed to the bacteria. After 10 min, values for free viral particles were below 5% for both phages.

FIG 1.

Curve for one-step growth of phage DRA88 (left) and phage K (right) in S. aureus RN4220 at 37°C. Shown are the PFU per infected cell in untreated cultures (●) and in chloroform-treated cultures (○) at several time points over 60 min. The phage growth parameters are indicated in the figure and correspond to eclipse period (E), latent period (L), and burst size (B). Each data point is the mean of three independent experiments, and error bars indicate the means ± standard deviations.

FIG 2.

Percentage of free DRA88 (A) and phage K (B) phages after infection of actively growing S. aureus RN4220 at an MOI of 0.001 at several time points over 10 min. Rate constants for loss of phage are 0.352 min−1 for phage K and 0.252 min−1 for DRA88. Each data point is the mean of three independent experiments, and error bars indicate the means ± standard deviations.

Morphology of phage particles.

The isolated phage DRA88 was further characterized with regard to its morphology. Images of the phage DRA88 were developed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The results revealed that phage DRA88 has, along with an icosahedral head of ∼78 nm in diameter, a long contractile tail of ∼179 nm with tail fibers (Fig. 3A). Therefore, it can be classified as belonging to the Myoviridae family (order Caudovirales), according to the classification system of Ackermann (44). It was observed for phage DRA88 that, besides single phage particles, there were also various aggregates made through contact of their tail fibers (Fig. 3B). Phage K was also observed under TEM (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), revealing a viral particle also belonging to the Myoviridae family (27). The zeta potential of phage DRA88 and phage K calculated from the electrophoretic mobility was −17 mV and −26.3 mV, respectively. The size measured was 122 nm for phage K, but according to the TEM micrographs and the literature, this phage has an average size of 280 nm total (45). This discrepancy could be due to contraction of tails, which was observed frequently, and can interfere with the measurement. Note that dynamic light scattering (DLS) may show lower accuracy when measuring irregularly shaped particles, such as tailed phages, where the size is not uniform in all dimensions. Regarding phage DRA88, we were not able to obtain an accurate size measurement and this can be related to the phenomenon of aggregation observed under TEM.

FIG 3.

Electron micrograph images of phage DRA88 negatively stained with 1% uranyl acetate, showing the tail in a contracted position (A) and formation on phage particle aggregates (B). Scale is indicated by the bars.

Genomic characterization of DRA88 and comparison with phage K.

To gain a more ample understanding of the phage DRA88, its DNA was extracted and genome sequencing was performed. Upon assembly and annotation, it was found that phage DRA88 has a large double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) genome with terminal redundancy, which suggests that phage DRA88 has a headful packaging system (46). The genome comprises 141,907 bp and can be grouped into class III of staphylococcal phages (>125 kbp) (47); 204 putative coding regions and four tRNA genes were identified (Fig. 4; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material). The gene coding potential, with 1.44 genes per kb, exhibits a high gene density. The majority of genes, 145 (71%), are found in the forward strand, and 59 (29%) are found in the opposite strand. tRNA genes are all located in the reverse strand of the genome. Regarding the GC% content, it is 30.4%, a lower percentage than the one found in the S. aureus host, 32.9%. The amino acid sequence was found to share strong similarities (>95%) with those of several other phages, such as JD007 and GH15, previously sequenced (48, 49). A comparison between phage DRA88 and phage K was performed using the BLAST algorithm (48). The DRA88 genome seems to be organized into functional modules—cell lysis, DNA replication, and structural elements—highly similar to the organization of phage K and other staphylococcal Myoviridae phages belonging to the Twort-like viruses (47, 50, 51). Between these modules, we can find several putative coding regions that are not yet found in the NCBI database or have no attributed function (phage and hypothetical proteins). These unknown functions represent 84.81% of the coding capacity. Three potential coding regions (orf178, orf192, and orf195) did not have any identical match with phage genes in the NCBI database. DRA88 lysin and DNA polymerase are not interrupted by introns (49), in contrast to phage K but similarly to phage GH15. At the end of the genome (between orf164 and orf182), there is a large coding region with unidentified functions inserted into the DRA88 genome that is not observed in phage K. Also, DRA88 genome analysis did not reveal similarity to known virulence-associated or toxin proteins.

FIG 4.

Comparative genomic analysis of phage DRA88 and phage K. Nucleotide sequences were compared using the Artemis comparison tool (ACT). Predicted open reading frames are denoted by arrows, tRNAs are indicated (vertical blue dashed line), and genes encoding proteins with at least 69% amino acid identity between the two genomes are indicated by shaded regions.

Bacteriophage mixture inhibits planktonic bacterial growth.

The efficacy of single DRA88 and phage K and their combination was assessed when treating bacterial cultures. Single phages and the phage mixture (MOI, 0.1) were introduced in a bacterial culture already growing for 2 h under planktonic conditions and allowed to incubate for a further 22 h (Fig. 5). Single-phage treatment showed less success in general than the phage mixture, and this was clearly observed for S. aureus 15981 (Fig. 5A). For all three S. aureus bacterial cultures—15981, MRSA 252, and H325—no cell growth was observed when the phage mixture was present compared to bacterial growth only. In fact, we observed efficient inhibition of the bacterial growth for 15981 and H325. The same was not observed for MRSA 252, where we observed bacterial growth after 18 h of treatment (time = 20 h).

FIG 5.

Dynamic of bacteria with single phage and phage mixture in liquid cultures over 24 h of incubation at 37°C. Absorbance readings at 590 nm were taken in a microtiter plate reader. S. aureus isolates 15981 (A), MRSA 252 (B), and H325 (C) growing with only SM buffer (○), with single DRA88 (▼), with single phage K (△), and with the phage mixture in SM buffer (■) and also a negative-control SM-only buffer (●) are shown in the figure. Assays were performed three times, and OD590 was expressed as the mean ± standard deviation.

Biofilm eradication.

Biofilms produced by the three S. aureus isolates were established in microtiter plates. All isolates were strong biofilm producers; however, MRSA 252 followed by H325 isolates produced lower biofilm biomass and more fragile structures (when performing the mechanical washing steps, the biofilm was more susceptible to disruption). The established biofilms were treated with single and mixed phage at an MOI of 10, and the biofilm was assessed (Fig. 6 and 7). Measurement of biofilm density made using crystal violet/OD590 over 48 h showed a clear reduction following phage inoculation compared with nontreated controls (P < 0.05). A decrease in biofilm biomass from the mixture compared with the single phages after 48 h of treatment was seen in all cases; although not significant, it can be observed by eye (along with CV-stained wells). Established biofilms were also treated with the phage mix at two different MOIs, 1 and 10, and the biofilm was assessed at the time points 0 h, 2 h, 4 h, 24 h, and 48 h (Fig. 8). Unsurprisingly, phage mixtures with higher MOIs (10 compared with 1) gave a more rapid reduction in biofilm density, although both MOIs, 1 and 10, resulted in the same endpoint after 48 h. For S. aureus 15981 biofilms treated with an MOI of 10, at 4 h after treatment, there was already more than 50% biofilm reduction (P < 0.05), and after 48 h of treatment, the biofilm biomass was almost completely disrupted (MOI of 10, P = 4.82 × 10−3; MOI of 1, P = 1.47 × 10−5) (Fig. 8A). Figure 8B shows that biofilms produced by MRSA 252 were eliminated by more than 50% (MOI of 10, P = 0.003; MOI of 1, P = 0.012) after 48 h of phage treatment. Finally, biofilms produced by H325 were not initially as strong as the other isolates. However, we were able to observe a reduction of the biofilms as well over 48 h for an MOI of 10 (P = 0.049). For an MOI of 1, a reduction of the biofilm structure was observed after 24 h (P = 0.034). However, such reduction was not observed after 48 h.

FIG 6.

Normalized biofilm biomass treated with single phage K, DRA88, and the phage mixture after 48 h at an MOI of 10 (OD590 reading after CV staining). S. aureus isolates: 1, 15981; 2, MRSA 252; 3, H325. Mean values (standard deviations) for the three strains treated with phage K were 0.63 (±0.10), 0.30 (±0.16), and 0.27 (±0.06); those for DRA88 were 0.11 (±0.04), 0.18 (±0.08), and 0.29 (±0.03); and those for the phage mixture were 0.06 (±0.02), 0.15 (±0.02), and 0.23 (±0.02). Assays were performed three times, and the means ± standard deviations are indicated. Statistical significance of biofilm reduction was assessed by performing Student's t test. P values are indicated (*, <0.05).

FIG 7.

Visualization of wells stained with 0.1% crystal violet after 48 h of phage treatment at an MOI of 10. Shown are the biofilm wells treated with PBS, phage K, DRA88, and phage mixture at 0 h (A) and 48 h after (B). Experiments were performed in triplicate.

FIG 8.

Normalized biofilm biomass treated with the phage mixture over 48 h at two different MOIs (OD590 reading after CV staining). S. aureus isolates: 15981 (A), MRSA 252 (B), and H325 (C). Assays were performed three times, and the means ± standard deviations are indicated. Statistical significance of biofilm reduction was assessed by performing Student's t test. P values are indicated (*, <0.05).

DISCUSSION

S. aureus biofilms in wounds and catheter sites present particular problems to patients, increasing morbidity, mortality, and difficulty in delivering effective chemotherapy. For wound healing to occur, treatment of the biofilm infection is essential and often requires selection of the correct antibiotic. The choice of appropriate chemotherapy is, however, made more difficult due to the increasing prevalence of antibiotic resistance. Hence, solutions are required to avoid treatment delay or ineffectiveness.

The host range infectivity of DRA88 against a genetically diverse collection of S. aureus isolates was broad, showing that this is a polyvalent phage. Based on TEM analysis, DRA88 belongs to the Myoviridae tailed-phage family. DRA88 adsorption occurred rapidly and at a rate similar to that observed for phage K, which is in accordance with several S. aureus-infecting Myoviridae phages (52, 53). An interesting observation for phage DRA88 was the possible formation of phage aggregates. Phage aggregation is observed occasionally in nature (54, 55) and is dependent on pH, ionic strength, and the composition of ions. Such phenomena could have been influenced by uranyl acetate (pH 4) used to stain the phages for TEM observation. However, DLS measurements (in dH2O, ∼pH 7) were unsuccessful, possibly due to the several sizes found in the sample (singles and several aggregates); hence, we suspect that phage DRA88 is prone to forming aggregates. When phage interacts with bacterial cells, aggregation could impede phage access to the cells and hence decrease the rate of adsorption. Phage aggregation can be inhibited by optimization of growth medium composition or stabilized in nanoemulsions, resulting in phages that more efficiently attach to bacterial cells (56–58); consequently, this could affect estimation of the PFU, which then may not directly correspond with the number of infective particles (MOI).

At the genome level, DRA88 was revealed to be a large double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) phage, usually a common characteristic of Myoviridae virus (50), carrying a high gene density and low GC%. It exhibits a high degree of relatedness to several other phages of the Twort-like group, including phage K. No virulence factors in the genome were identified, according to the data available, suggesting that this phage could be safely used to treat S. aureus infections. The majority of putative coding regions of the DRA88 genome do not have any function attributed yet, which is generally observed for the numerous phages being sequenced at the current time (59). Consequently, there is a crucial need for a more comprehensive investigation of phage genomes. Considering phage therapy as a therapeutic approach option, it is extremely important that we expand our knowledge regarding phage genes and proteins and their respective functions and potentialities, as they can be involved in phage-host interaction and even code for novel virulence determinants (60).

The novel isolated phage was mixed into a phage mixture with phage K, and as a result, their lytic potential was increased (74% of host coverage). The use of a phage mixture is largely preferred over use of single phage as it results in a decreased rate of bacteria exhibiting resistance (61, 62). Bacterial broth cultures growing with phage mixtures showed an elimination of bacterial cells and suppression of resistant mutants. However, this was observed for only two strains; after 18 h of growth, MRSA 252 was able to counteract the infectivity of the phage particles present in the culture, possibly due to the presence of phage-receptor-mutated clones present in the culture. This situation could be overcome or delayed by including more phage types in the therapeutic mixture, a task far easier (more rapid and likely to succeed) to undertake than the discovery of a new antibiotic. It has been demonstrated that phage therapy could be delivered in synchronization with another antibacterial therapy, such as antibiotics (63). Reducing the initial bacterial load could be sufficient to bring the bacterial numbers under control so that the rug and also the action of the immune system could clear the infection (63–65) in an effective way.

More than 60% of all infections are related to the formation of biofilms (12). Hence, it is important that biofilm model studies are investigated when testing a new antibacterial phage mixture. Some studies already suggest the significant potential of phages to reduce and/or eliminate biofilms. This is the case for phage K, where biofilms produced by S. aureus isolates showed a remarkable decrease in their biofilm biomass after addition of the phage (28, 41). Here, we showed that the phage mixture was able to reduce significantly the biofilm load on the polystyrene surface of a microtiter plate. For isolate 15981, the eradication effect started readily after addition of the killing mixture, and after 48 h of treatment, the biofilm was almost completely disrupted. Higher MOI showed a more rapid effect of biofilm reduction, and a better prevention of biofilm regrowth was also observed for isolate H325. Comparing the effect of phage mixture on broth cultures to biofilm, we observed a more positive effect on eliminating the bacterial load of broth cultures than that on biofilm, which is disrupted more slowly. This scenario was hypothesized to be due to the metabolic state of the cells. In biofilms, cells can be in a low-metabolic-activity stage, and phages cannot proliferate as efficiently as in actively growing cells (41). To date, very few studies have been performed regarding phage mixture treatments, especially to treat S. aureus biofilms and in particular MRSA-caused ones. Kelly et al. (28) have already shown the efficacy of a phage K and derivative mixture on the eradication of S. aureus biofilms produced by nonhuman clinical isolates. Here, we go further by treating biofilms produced by prevalent human clinical isolates that also include MRSA types. This study suggests that the utilization of a mixture of bacteriophage, i.e., phage K and DRA88 in this case, could provide a practical alternative to antibiotic/antimicrobial treatments for combating some S. aureus infections and in particular the devastating effects of MRSA infections and related biofilms, such as burn-wound or catheter infection. Even with the contribution of this study to the effectiveness of bacteriophage therapy to fight established bacterial infections, there is still a long way to go and several barriers to address. The safety of phages and ethical and regulatory issues, for example, must be overcome in order for phages to become an available alternative therapeutic (see review in reference 66).

In summary, here we describe the isolation and characterization of a novel bacteriophage against pathogenic S. aureus bacteria. The phage, in combination with phage K, showed an improved range of infectivity of S. aureus isolates and a potent effect in biofilm dispersion, making it a good candidate for further therapeutic development.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Thames Water for providing the water samples and Ursula Potter for her help with TEM analysis and sample preparation. We also thank AmpliPhi Biosciences Corp. for their important collaboration and technical assistance.

This work was partly supported by the MetaPhageLAB project financed by The Danish Research Council for Technology and Production (project 11-106991, document 2105568). We also thank the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) Healthcare Partnership fund for their funding and support.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 22 August 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01789-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lowy FD. 1998. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 339:520–532. 10.1056/NEJM199808203390806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster TJ. 2005. Immune evasion by staphylococci. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:948–958. 10.1038/nrmicro1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plata K, Rosato AE, Wegrzyn G. 2009. Staphylococcus aureus as an infectious agent: overview of biochemistry and molecular genetics of its pathogenicity. Acta Biochim. Pol. 56:597–612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang S, Sievert DM, Hageman JC, Boulton ML, Tenover FC, Downes FP, Shah S, Rudrik JT, Pupp GR, Brown WJ, Cardo D, Fridkin SK. 2003. Infection with vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus containing the vanA resistance gene. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:1342–1347. 10.1056/NEJMoa025025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray CK, Holmes RL, Ellis MW, Mende K, Wolf SE, McDougal LK, Guymon CH, Hospenthal DR. 2009. Twenty-five year epidemiology of invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolates recovered at a burn center. Burns 35:1112–1117. 10.1016/j.burns.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keen EF, Robinson BJ, Hospenthal DR, Aldous WK, Wolf SE, Chung KK, Murray CK. 2010. Prevalence of multidrug-resistant organisms recovered at a military burn center. Burns 36:819–825. 10.1016/j.burns.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erol S, Altoparlak U, Akcay MN, Celebi F, Parlak M. 2004. Changes of microbial flora and wound colonization in burned patients. Burns 30:357–361. 10.1016/j.burns.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Percival SL, Hill KE, Williams DW, Hooper SJ, Thomas DW, Costerton JW. 2012. A review of the scientific evidence for biofilms in wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 20:647–657. 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2012.00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Høiby N, Bjarnsholt T, Givskov M, Molin S, Ciofu O. 2010. Antibiotic resistance of bacterial biofilms. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 35:322–332. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Beer D, Stoodley P, Lewandowski Z. 1997. Measurement of local diffusion coefficients in biofilms by microinjection and confocal microscopy. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 53:151–158. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lam J, Chan R, Lam K, Costerton JW. 1980. Production of mucoid microcolonies by Pseudomonas aeruginosa within infected lungs in cystic fibrosis. Infect. Immun. 28:546–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.James GA, Swogger E, Wolcott R, Pulcini ED, Secor P, Sestrich J, Costerton JW, Stewart PS. 2008. Biofilms in chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 16:37–44. 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies CE, Hill KE, Wilson MJ, Stephens P, Hill CM, Harding KG, Thomas DW. 2004. Use of 16S ribosomal DNA PCR and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis for analysis of the microfloras of healing and nonhealing chronic venous leg ulcers. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:3549–3557. 10.1128/JCM.42.8.3549-3557.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donlan RM. 2008. Biofilms on central venous catheters: is eradication possible? Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 322:133–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darouiche RO. 2004. Treatment of infections associated with surgical implants. N. Engl. J. Med. 350:1422–1429. 10.1056/NEJMra035415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sen CK, Gordillo GM, Roy S, Kirsner R, Lambert L, Hunt TK, Gottrup F, Gurtner GC, Longaker MT. 2010. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen. 17:763–771. 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liapikou A, Torres A. 2013. Emerging drugs on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs 18:291–305. 10.1517/14728214.2013.813480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurlenda J, Grinholc M. 2012. Alternative therapies in Staphylococcus aureus diseases. Acta Biochim. Pol. 59:171–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burrowes B, Harper DR, Anderson J, McConville M, Enright MC. 2011. Bacteriophage therapy: potential uses in the control of antibiotic-resistant pathogens. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 9:775–785. 10.1586/eri.11.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young I, Wang I, Roof WD. 2000. Phages will out: strategies of host cell lysis. Trends Microbiol. 8:120–128. 10.1016/S0966-842X(00)01705-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kraushaar B, Thanh MD, Hammerl JA, Reetz J, Fetsch A, Hertwig S. 2013. Isolation and characterization of phages with lytic activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains belonging to clonal complex 398. Arch. Virol. 158:2341–2350. 10.1007/s00705-013-1707-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Capparelli R, Parlato M, Borriello G, Salvatore P, Iannelli D. 2007. Experimental phage therapy against Staphylococcus aureus in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:2765–2773. 10.1128/AAC.01513-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gupta R, Prasad Y. 2011. Efficacy of polyvalent bacteriophage P-27/HP to control multidrug resistant Staphylococcus aureus associated with human infections. Curr. Microbiol. 62:255–260. 10.1007/s00284-010-9699-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abedon ST. 2011. Bacteriophages and biofilms: ecology, phage therapy, plaques. Nova Science Publishers, Hauppauge, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Górski A, Miedzybrodzki R, Borysowski J, Weber-Dabrowska B, Lobocka M, Fortuna W, Letkiewicz S, Zimecki M, Filby G. 2009. Bacteriophage therapy for the treatment of infections. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 10:766–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skurnik M, Pajunen M, Kiljunen S. 2007. Biotechnological challenges of phage therapy. Biotechnol. Lett. 29:995–1003. 10.1007/s10529-007-9346-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Flaherty S, Ross RP, Meaney W, Fitzgerald GF, Elbreki MF, Coffey A. 2005. Potential of the polyvalent anti-Staphylococcus bacteriophage K for control of antibiotic-resistant staphylococci from hospitals. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:1836–1842. 10.1128/AEM.71.4.1836-1842.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelly D, McAuliffe O, Ross RP, Coffey A. 2012. Prevention of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation and reduction in established biofilm density using a combination of phage K and modified derivatives. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 54:286–291. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2012.03205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Flaherty S, Coffey A, Edwards R, Meaney W, Fitzgerald GF, Ross RP. 2004. Genome of staphylococcal phage K: a new lineage of Myoviridae infecting gram-positive bacteria with a low G+C content. J. Bacteriol. 186:2862–2871. 10.1128/JB.186.9.2862-2871.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xia G, Corrigan RM, Winstel V, Goerke C, Gründling A, Peschel A. 2011. Wall teichoic acid-dependent adsorption of staphylococcal siphovirus and myovirus. J. Bacteriol. 193:4006–4009. 10.1128/JB.01412-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Enright MC, Day NP, Davies CE, Peacock SJ, Spratt BG. 2000. Multilocus sequence typing for characterization of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible clones of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1008–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tucker RG. 1961. The role of magnesium ions in the growth of Salmonella phage anti-R. J. Gen. Microbiol. 26:313–323. 10.1099/00221287-26-2-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adams M. 1959. Bacteriophages. Interscience Publishers, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M, Meyer F, Olsen GJ, Olson R, Osterman AL, Overbeek RA, McNeil LK, Paarmann D, Paczian T, Parrello B, Pusch GD, Reich C, Stevens R, Vassieva O, Vonstein V, Wilke A, Zagnitko O. 2008. The RAST server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 9:75. 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nirmal Kumar GP, Sundarrajan S, Paul VD, Nandini S, Saravanan RS, Hariharan S, Sriram B, Padmanabhan S. 2012. Use of prophage free host for achieving homogenous population of bacteriophages: new findings. Virus Res. 169:182–187. 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pajunen M, Kiljunen S, Skurnik M. 2000. Bacteriophage ϕYeO3-12, specific for Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O:3, is related to coliphages T3 and T7. J. Bacteriol. 182:5114–5120. 10.1128/JB.182.18.5114-5120.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boulanger P. 2009. Purification of bacteriophages and SDS-PAGE analysis of phage structural proteins from ghost particles. Methods Mol. Biol. 502:227–238. 10.1007/978-1-60327-565-1_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pickard DJJ. 2009. Preparation of bacteriophage lysates and pure DNA. Methods Mol. Biol. 502:3–9. 10.1007/978-1-60327-565-1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sambrook J, Russell DW. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed, vol 1 to 3 CSH Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kot W, Vogensen FK, Sørensen SJ, Hansen LH. 2014. DPS—a rapid method for genome sequencing of DNA-containing bacteriophages directly from a single plaque. J. Virol. Methods 196:152–156. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2013.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cerca N, Oliveira R, Azeredo J. 2007. Susceptibility of Staphylococcus epidermidis planktonic cells and biofilms to the lytic action of staphylococcus bacteriophage K. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 45:313–317. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2007.02190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abramson JH. 2011. WINPEPI updated: computer programs for epidemiologists, and their teaching potential. Epidemiol. Perspect. Innov. 8:1. 10.1186/1742-5573-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sillankorva S, Neubauer P, Azeredo J. 2008. Isolation and characterization of a T7-like lytic phage for Pseudomonas fluorescens. BMC Biotechnol. 8:80. 10.1186/1472-6750-8-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ackermann H-W. 2011. Bacteriophage taxonomy. Microbiol. Aust. 32:90–94. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rees PJ, Fry BA. 1981. The morphology of staphylococcal bacteriophage K and DNA metabolism in infected Staphylococcus aureus. J. Gen. Virol. 53:293–307. 10.1099/0022-1317-53-2-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Streisinger G, Emrich J, Stahl MM. 1967. Chromosome structure in phage t4, iii. Terminal redundancy and length determination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 57:292–295. 10.1073/pnas.57.2.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kwan T, Liu J, DuBow M, Gros P, Pelletier J. 2005. The complete genomes and proteomes of 27 Staphylococcus aureus bacteriophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:5174–5179. 10.1073/pnas.0501140102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cui Z, Song Z, Wang Y, Zeng L, Shen W, Wang Z, Li Q, He P, Qin J, Guo X. 2012. Complete genome sequence of wide-host-range Staphylococcus aureus phage JD007. J. Virol. 86:13880–13881. 10.1128/JVI.02728-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gu J, Liu X, Lu R, Li Y, Song J, Lei L, Sun C, Feng X, Du C, Yu H, Yang Y, Han W. 2012. Complete genome sequence of Staphylococcus aureus bacteriophage GH15. J. Virol. 86:8914–8915. 10.1128/JVI.01313-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deghorain M, Van Melderen L. 2012. The staphylococci phages family: an overview. Viruses 4:3316–3335. 10.3390/v4123316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Łobocka M, Hejnowicz Dąbrowski MS, Gozdek K, Kosakowski A, Witkowska J, Ulatowska MI, Weber-Dąbrowska B, Kwiatek M, Parasion S, Gawor J, Kosowska H, Głowacka A. 2012. Genomics of staphylococcal Twort-like phages—potential therapeutics of the post-antibiotic era. Adv. Virus Res. 83:143–216. 10.1016/B978-0-12-394438-2.00005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hsieh S-E, Lo H-H, Chen S-T, Lee M-C, Tseng Y-H. 2011. Wide host range and strong lytic activity of Staphylococcus aureus lytic phage Stau2. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:756–761. 10.1128/AEM.01848-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kwiatek M, Parasion S, Mizak L, Gryko R, Bartoszcze M, Kocik J. 2012. Characterization of a bacteriophage, isolated from a cow with mastitis, that is lytic against Staphylococcus aureus strains. Arch. Virol. 157:225–234. 10.1007/s00705-011-1160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hejkal TW, Wellings FM, Lewis AL, LaRock PA. 1981. Distribution of viruses associated with particles in waste water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 41:628–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Narang HK, Codd AA. 1981. Frequency of preclumped virus in routine fecal specimens from patients with acute nonbacterial gastroenteritis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 13:982–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Langlet J, Gaboriaud F, Gantzer C. 2007. Effects of pH on plaque forming unit counts and aggregation of MS2 bacteriophage. J. Appl. Microbiol. 103:1632–1638. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zemb O, Manefield M, Thomas F, Jacquet S. 2013. Phage adsorption to bacteria in the light of the electrostatics: a case study using E. coli, T2 and flow cytometry. J. Virol. Methods 189:283–289. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Esteban PP, Alves DR, Enright MC, Bean JE, Gaudion A, Jenkins ATA, Young AER, Arnot TC. 2014. Enhancement of the antimicrobial properties of bacteriophage-K via stabilization using oil-in-water nano-emulsions. Biotechnol. Prog. 30:932–944. 10.1002/btpr.1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hatfull GF. 2008. Bacteriophage genomics. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11:447–453. 10.1016/j.mib.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lima-Mendez G, Toussaint A, Leplae R. 2011. A modular view of the bacteriophage genomic space: identification of host and lifestyle marker modules. Res. Microbiol. 162:737–746. 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tanji Y, Shimada T, Fukudomi H, Miyanaga K, Nakai Y, Unno H. 2005. Therapeutic use of phage cocktail for controlling Escherichia coli O157:H7 in gastrointestinal tract of mice. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 100:280–287. 10.1263/jbb.100.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gu J, Liu X, Li Y, Han W, Lei L, Yang Y, Zhao H, Gao Y, Song J, Lu R, Sun C, Feng X. 2012. A method for generation phage cocktail with great therapeutic potential. PLoS One 7:e31698. 10.1371/journal.pone.0031698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ryan EM, Alkawareek MY, Donnelly RF, Gilmore BF. 2012. Synergistic phage-antibiotic combinations for the control of Escherichia coli biofilms in vitro. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 65:395–398. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.00977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Comeau AM, Tétart F, Trojet SN, Prère M-F, Krisch HM. 2007. Phage-antibiotic synergy (PAS): beta-lactam and quinolone antibiotics stimulate virulent phage growth. PLoS One 2:e799. 10.1371/journal.pone.0000799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kirby AE. 2012. Synergistic action of gentamicin and bacteriophage in a continuous culture population of Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One 7:e51017. 10.1371/journal.pone.0051017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Henein A. 2013. What are the limitations on the wider therapeutic use of phage? Bacteriophage 3:e24872. 10.4161/bact.24872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.