ABSTRACT

Much is known about the characteristics of broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs) generated during HIV-1 infection, but little is known about immunological mechanisms responsible for their development in only a minority of those infected by HIV-1. By monitoring longitudinally a cohort of HIV-1-infected subjects, we observed that the preservation of CXCR5+ CD4+ T helper cell frequencies and activation status of B cells during the first year of infection correlates with the maximum breadth of plasma neutralizing antibody responses during chronic infection independently of viral load. Although, during the first year of infection, no differences were observed in the abilities of peripheral CXCR5+ CD4+ T helper cells to induce antibody secretion by autologous naive B cells, higher frequencies of class-switched antibodies were detected in cocultures of CXCR5+ CD4+ T and B cells from the subjects who later developed broadly neutralizing antibody responses than those who did not. Furthermore, B cells from the former subjects had higher expression of AICDA than B cells from the latter subjects, and transcript levels correlated with the frequency of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells. Thus, the early preservation of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells and B cell function are central to the development of bNAbs. Our study provides a possible explanation for their infrequent generation during HIV-1 infection.

IMPORTANCE Broadly neutralizing antibodies are developed by HIV-1-infected subjects, but so far (and despite intensive efforts over the past 3 decades) they have not been elicited by immunization. Understanding how bNAbs are generated during natural HIV-1 infection and why only some HIV-1-infected subjects generate such antibodies will assist our efforts to elicit bNAbs by immunization. CXCR5+ PD-1+ CD4+ T cells are critical for the development of high-affinity antigen-specific antibody responses. In our study, we found that the HIV-1-infected subjects who develop bNAbs have a higher frequency of peripheral CXCR5+ PD-1+ CD4+ T cells in early infection and also that this frequency mirrored what was observed in uninfected subjects and correlated with the level of B cell activation across subjects. Our study highlights the critical role helper T cell function has in the elicitation of broadly neutralizing antibody responses in the context of HIV infection.

INTRODUCTION

Broadly neutralizing antibody (bNAb) responses (BNAR) are detectable in approximately 20% of sera from chronic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-infected subjects (1–7). In subjects who develop them, BNAR become detectable approximately 2 years after infection (7). Monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) displaying broad and potent anti-HIV-1 neutralizing activities isolated from HIV-1-infected subjects offer protection from infection in experimental animal models (8–17), can reduce established plasma viremia in SHIV-infected nonhuman primates (16, 18) and in HIV-1-infected humanized mice (19), and can delay viral rebound in chronically infected humans undergoing structured antiretroviral therapy (ART) treatment interruption (20, 21). Therefore, broadly neutralizing antibodies are believed to be a critical component of an effective vaccine against HIV-1 (22–24). However, despite intensive efforts over the past 3 decades, BNAR have not been generated by candidate HIV-1 vaccines (22, 23, 25, 26). Identifying the specific immunological pathways that are necessary for the development of BNAR is critically important for the eventual elicitation of such responses by vaccination.

Following infection or vaccination, antibodies with gradually greater binding affinities to specific antigens are produced (27–30). In the case of HIV-1 infection, the gradual increase of antibody binding affinity to key epitopes of the viral envelope glycoprotein (Env) results in antibodies displaying gradually more potent and broad antiviral neutralizing activities (31). Antibody affinity maturation is dependent on the help B cells receive from specialized CD4 T cells, T follicular helper (Tfh) cells (32). Tfh cells are found in the B cell follicles of secondary lymphoid organs and are identified by high expression of CXCR5 and PD-1, and they are further characterized by expression of ICOS, BCL6, interleukin-21 (IL-21), and CXCL13 (33–36). The expression of CXCR5 by Tfh cells and by mature B cells allows for their comigration into germinal centers (GC) via a CXCL13 gradient (35, 37). A population of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells found in the periphery is believed to encompass memory Tfh cells, which have downmodulated the expression of many of the molecules characteristic of Tfh cells in the follicles (35, 37–42). Upon restimulation, CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells take on a more pronounced Tfh cell phenotype, traffic to B cell follicles, and provide help to B cells (37–41, 43).

Tfh cells are infected by HIV-1 or simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), but their frequencies generally are maintained at physiological frequencies during chronic infection (44–47). While Tfh cells from chronic HIV-1-infected subjects are capable of providing help to B cells (46), there is evidence that the interaction between Tfh and B cells in the lymph nodes is impaired (47). In addition, the frequency and functionality of peripheral CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells appears to decline during chronic HIV-1 infection (48). Although the phenotype of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells has been associated with the development of plasma BNAR in the context of chronic clade C HIV-1 infection (42), it remains unclear as to whether or not such cells influence the development of BNAR during HIV-1 infection (42, 48). Defining the role of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells in the development of BNAR in the context of HIV-1 infection will improve our understanding of why only a fraction of those infected with HIV-1 develop BNAR but also may assist vaccination efforts aimed at eliciting BNAR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient samples.

Plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) samples were collected from HIV-1-infected individuals after signed informed consent and in accordance with the Institutional Review Boards of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Plasma and PBMCs were isolated from HIV-negative human subjects enrolled in a blood draw protocol at Seattle Biomedical Research Institute approved by the Western Institutional Review Board and were HIV negative by self-reporting. All subjects provided informed consent.

All subjects remained ART naive throughout the period of observation, with peripheral CD4+ T lymphocyte counts of >200/μl and various levels of plasma viremia (7). The development of plasma BNAR activities in a subset of individuals in this cohort was documented in detail previously (7) and is summarized here (Fig. 1 and Table 1). During the period of observation, five of these subjects developed plasma BNAR capable of neutralizing at least 75% of the heterologous HIV-1 viruses tested (including tier 2 viruses from clades A, B, and C; we term this group broad) and 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) neutralization titers greater than 1,000 in some cases. Two of the remaining subjects were excluded from further analysis, as they were not monitored for a sufficient length of time (less than 2 years postinfection) to conclusively determine the breadth of BNAR. The remaining 10 subjects developed neutralizing activities of much narrower breadth: their sera neutralized 50% or less of heterologous strains tested during the observation period (we term this group narrow). PBMCs were available from the five broad subjects and seven of the narrow subjects for cellular assays. All 10 narrow subjects were included for plasma studies.

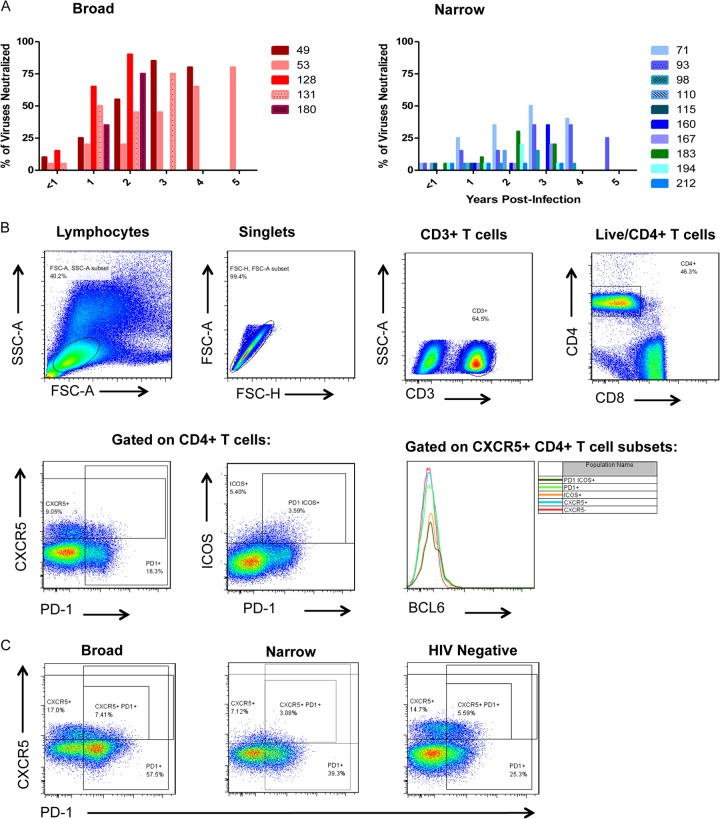

FIG 1.

(A) Summary of development of broad plasma neutralizing antibody responses at the indicated years postinfection in broad (left) and narrow (right) subject groups. Individual subjects are represented by the numbers listed and respective colored bars. (B) Representative flow cytometry gating strategy for peripheral CXCR5, PD-1, and ICOS-expressing CD4+ T cells of PBMCs. SSC, side scatter; FSC, forward scatter. (C) Expression of CXCR5 and PD-1 on peripheral CD4+ T cells from representative subjects from the broad (left), narrow (middle), and HIV-1-negative control (right) groups is shown.

TABLE 1.

Viral loads and neutralizing breadth of HIV-1-infected subjects

| Subject ID | Viral load (copies/ml) | Neutralizing antibody breadth (%) | Yr postinfection |

|---|---|---|---|

| AC049 | 2,550 | 10 | 0.62 |

| 4,230 | 25 | 1.09 | |

| 32,300 | 55 | 2.62 | |

| 24,500 | 85 | 3.64 | |

| 71,200 | 80 | 4.39 | |

| AC053 | 7,010 | 5 | 0.82 |

| 9,960 | 20 | 1.75 | |

| 6,530 | 20 | 2.29 | |

| 7,610 | 45 | 3.29 | |

| 2,250 | 65 | 4.30 | |

| 21,400 | 80 | 5.31 | |

| 23,500 | 60 | 5.88 | |

| 184,000 | 60 | 6.85 | |

| AC071 | 10,223 | 5 | 0.39 |

| 26,300 | 25 | 1.30 | |

| 15,500 | 35 | 2.28 | |

| 28,500 | 50 | 3.34 | |

| 29,800 | 40 | 3.80 | |

| AC093 | 24,000 | 5 | 0.12 |

| 69,300 | 5 | 0.90 | |

| 39,100 | 15 | 1.88 | |

| 16,900 | 15 | 2.91 | |

| 49,200 | 35 | 3.99 | |

| 112,000 | 35 | 4.97 | |

| 304,000 | 25 | 5.74 | |

| AC098 | 8,360 | 0 | 0.37 |

| 9,810 | 5 | 1.17 | |

| 25,600 | 5 | 2.21 | |

| 91,000 | 15 | 3.02 | |

| 233,000 | 5 | 4.31 | |

| AC110 | 23,700 | 5 | 0.41 |

| 35,100 | 5 | 1.03 | |

| 138,000 | 15 | 2.69 | |

| AC115 | 5,490 | 5 | 0.65 |

| 127 low | 5 | 1.58 | |

| AC128 | 75,001 | 15 | 0.43 |

| 174,000 | 65 | 1.41 | |

| 294,000 | 90 | 2.47 | |

| AC131 | 132,000 | 5 | 0.63 |

| 195,000 | 50 | 1.52 | |

| 114,000 | 45 | 2.38 | |

| 462,000 | 75 | 3.19 | |

| AC160 | 3,150 | 0 | 0.20 |

| 14,200 | 5 | 1.04 | |

| 20,200 | 5 | 2.13 | |

| 98,300 | 35 | 3.23 | |

| AC167 | 136 | 0 | 0.68 |

| 1,600 | 5 | 1.72 | |

| 6,710 | 5 | 2.25 | |

| 11,400 | 20 | 4.51 | |

| AC180 | 331,000 | 0 | 0.06 |

| Not available | 35 | 1.21 | |

| 564,000 | 75 | 2.19 | |

| AC183 | 5,220 | 5 | 0.34 |

| 9,630 | 10 | 1.54 | |

| 7,590 | 30 | 2.53 | |

| 16,400 | 20 | 3.54 | |

| AC194 | 111,000 | 5 | 0.23 |

| 1,850 | 5 | 1.17 | |

| 7,010 | 20 | 2.13 | |

| Not available | 5 | 2.37 | |

| AC212 | 770 | 5 | 0.07 |

| 2,700 | 5 | 1.03 | |

| 27,600 | 5 | 2.04 | |

| 112,000 | 5 | 2.56 |

T and B cell phenotyping.

Cryopreserved and thawed PBMCs were used for flow-cytometric analysis. For T cell phenotyping, 500,000 to 1,000,000 PBMCs were stained for Live/Dead aqua (Life Technologies), anti-CD3 fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (BD), anti-CD4 Qdot 605 (Life Technologies), anti-CD8 Pacific orange (EBioscience), anti-CXCR5 allophycocyanin (APC) (BD), anti-PD-1 violet (BioLegend), and anti-ICOS peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP)-Cy5.5 (BioLegend). They were fixed and permeabilized with FoxP3 fixation and a permeabilization kit (eBioscience) and stained for anti-BCL-6 phycoerythrin (PE) (BD). Note that the Live/Dead aqua was in the same channel as CD8 so that both CD8+ T cells and dead cells were excluded simultaneously. B cells were sorted from approximately 5 million PBMCs by magnetic beads using a negative selection B cell isolation kit (Stemcell). Isolated B cells were split: half were preserved in TRIzol and immediately placed at −80°C, and the other half were used for flow-cytometric analysis. B cells were preincubated with unlabeled anti-CD4 antibody and subsequently with biotinylated HIV-1 envelope (SF162 K160N gp120) for 20 min on ice and then washed with fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer and incubated with streptavidin Qdot 605 (Life Technologies) plus anti-CD3 V450 (BD), anti-CD19 PE-CY7 (Beckman Coulter), CD38 PE (BD), CD27 FITC (BD), CXCR5 APC (BD), and Live/Dead violet (Life Technologies). Samples were acquired on an LSRII (BD), and data were analyzed with FlowJo (TreeStar).

Cytokine analysis.

CXCL13, BAFF, and interleukin-21 (IL-21) were measured in plasma by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) by following the manufacturers' recommendations (CXCL13 and Baff ELISA kits were from R&D Systems, and the IL-21 ELISA kit was from EBioscience). Plasma levels of 26 cytokines and chemokines (Eotaxin, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor [G-CSF], granulocyte-macrophage CSF [GM-CSF], alpha interferon 2 [IFN-α2], IFN-γ, IL-10, IL-12 [p40], IL-12 [p70], IL-13, IL-15, IL-17, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, interferon gamma-induced protein 10 [IP-10], monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 [MCP-1], macrophage inflammatory protein alpha [MIP-1α], MIP-1β, tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α], and TNF-β) were measured by Luminex (Millipore).

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and gene expression.

RNA was extracted from B cells using a modified TRIzol-chloroform extraction combined with Qiagen RNeasy MinElute columns (Qiagen). In brief, cells were sorted directly into 500 μl chilled TRIzol and frozen at −80°C. One hundred μl chloroform was added. The mixture was centrifuged. The aqueous phase was transferred to a separate tube and combined with RLT buffer and ethanol (EtOH). The sample was transferred to a Qiagen MinElute spin column in a 2-ml collection tube. The rest of the Qiagen RNeasy protocol was followed. Eluted RNA was transferred immediately to −80°C for storage. cDNA was synthesized using the Qiagen QuantiTect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen) by following the manufacturer's instructions. Expression levels of 48 genes were evaluated using the appropriate TaqMan gene expression assay (validated primer/probe sets) for each gene and TaqMan gene expression master mix (Life Technologies) using the Fluidigm BioMark 48-well nanochip system by following Fluidigm BioMark protocols (Fluidigm). Expression levels were analyzed using the 2ΔCT method with the gene encoding glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as the reference gene.

T and B cell coculture.

Thawed PBMCs were stained with Live/Dead blue (Life Technologies), anti-CD3 V450 (BD), anti-CD19 PE-CY7 (Beckman Coulter), anti-CXCR5 APC (BD), anti-CD4 Qdot 605 (Life Technologies), anti-CD27 APC-CY7 (BioLegend), anti-CD14 Alexa 488 (BD), anti-CD11c PE-CY5 (BD), and anti-CD303/BDAC2 PE (BD). CXCR5+ and CXCR5− CD4+ CD3+ T cells as well as CD27− CD19+ CD3− B cells were sorted using a FACS Aria II (BD). A total of 25,000 naive B cells were plated with various numbers of CXCR5+ or CXCR5− CD4 T cells in 200 μl media in a 96-well plate. Cocultures were stimulated with 1 μg/ml staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB). On day 7 poststimulation, plates were spun down and supernatants were collected and immediately transferred to −80°C until being analyzed for IL-21 (ELISA from R&D Systems) and Ig (human isotyping kit from Bioplex) levels.

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as individual means or the medians per group of different donors. Nonparametric two-tailed Mann-Whitney tests, Wilcoxon paired tests, and Spearman correlations were calculated using GraphPad Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software). Multiple regression analysis was performed using InStat (GraphPad Software). P values of <0.05 were considered significant. The significance of P values from gene expression data was determined by computing Q values, using a false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.06 (49) using R.

RESULTS

Frequency of CXCR5+ PD-1+ CD4+ T cells during the first year of infection correlates with the breadth of neutralizing antibody responses during chronic infection.

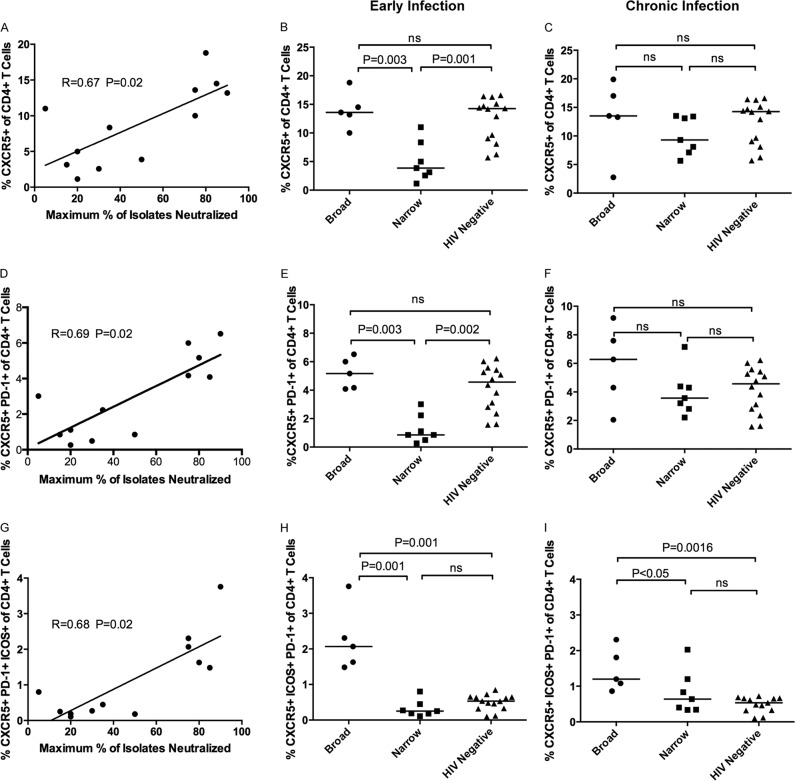

In the cohort of subjects examined here, we previously reported that the frequencies of peripheral PD-1+ CD4+ T lymphocytes were significantly higher in those who developed BNAR (7). Here, we evaluated the frequencies of peripheral CD4+ T cells expressing Tfh-associated markers CXCR5, ICOS, PD-1, and BCL-6 (Fig. 1B and C) during early (median of 0.32 years postinfection; range, 0.1 to 1) and chronic (median of 2.12 years postinfection; range, 1.41 to 3.29) infection. Like previous reports, we observed little expression of BCL-6 in the peripheral CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1B) (39, 43, 48, 50). Importantly, during early infection, the frequencies of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2A) (r = 0.67, P = 0.02), CXCR5+ PD-1+ CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2D) (r = 0.69, P = 0.01), or CXCR5+ PD-1+ ICOS+ CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2G) (r = 0.68, P = 0.01) correlated with the breadth of plasma neutralizing antibody responses detected several years later and independent of plasma viremia (according to multiple regression analysis for frequency, T ratio = 3.41 and P = 0.008 for CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells, T ratio = 3.78 and P = 0.004 for CXCR5+ PD-1+ CD4+ T cells, and T ratio = 3.69 and P = 0.005 for CXCR5+ PD-1+ ICOS+ CD4+ T cells). We then compared the frequencies of CXCR5+, CXCR5+ PD-1+, and CXCR5+ PD-1+ ICOS+ CD4+ T cells in subjects whose plasma from chronic infection neutralized 75% or more of viral isolates (broad) to those of the rest of the subjects, whose plasma from chronic infection neutralized 50% or less of viral isolates (narrow). We observed significantly higher frequencies of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2B) (P = 0.003), CXCR5+ PD-1+ CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2E) (P = 0.003), and CXCR5+ PD-1+ ICOS+ CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2H) (P = 0.001) in the broad group, and these frequencies mirrored those detected in HIV-negative subjects. We also calculated the frequencies of the CXCR5+ and the CXCR5+ PD-1+ populations as a percentage of the total CD3+ T cell population, and we observed that there were no significant differences during early infection between the broad and narrow subjects (data not shown). However, the frequency of the CXCR5+ PD-1+ ICOS+ CD4+ T cell population as a percentage of total CD3+ T cells remained significantly higher in the broad subjects than in the narrow subjects (P = 0.01) (data not shown).

FIG 2.

Frequency of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cell subsets in HIV-1-infected and uninfected subjects. The frequency of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells (A), CXCR5+ PD-1+ CD4+ T cells (D), or CXCR5+ PD-1+ ICOS+ CD4+ T cells (G) detected in HIV-1-infected samples during early infection was plotted against the maximum percentage of heterologous viral isolates neutralized by plasma isolated from chronic infection (n = 12 subjects). The frequency of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells in the broad (n = 5), narrow (n = 7), and HIV-1-negative control groups (n = 13) during early (B) and chronic (C) infection are shown. The frequency of CD4+ T cells expressing CXCR5 and PD-1 from the three groups during early (E) and chronic infection (F) are shown. The frequencies of CD4+ T cells that express CXCR5, PD-1, and ICOS during early (H) and chronic (I) infection are shown. Each dot represents a single subject. Correlations were determined by Spearman rank correlation and considered significant for P values of less than 0.05. The horizontal lines represent the median per subject group. The stated P values were calculated using the Mann-Whitney test for nonparametric data and were considered significant if less than 0.05. ns, not significant.

During chronic infection, the time when a broadening of the neutralizing antibody responses became detectable, the frequencies of CXCR5+, CXCR5+ PD-1+, or CXCR5+ PD-1+ ICOS+ CD4+ T cells did not correlate with the breadth of these antibody responses (data not shown). In addition, no significant differences in the frequencies of CXCR5+ or CXCR5+ PD-1+ CD4+ T cells between the broad and narrow groups were observed (Fig. 2C and F, respectively). This was due to a significant increase in the frequency of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells in the narrow group during chronic infection (P < 0.05) (data not shown), whereas the frequency in the broad group remained unchanged during chronic infection (data not shown), with the exception of one subject who had a plasma viral load of 5 × 105 copies/ml and subsequently required antiretroviral treatment. However, the frequency of CXCR5+ ICOS+ PD-1+ CD4+ T cells was still elevated in the broad subjects compared to both the narrow and HIV-negative subjects (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2I).

Therefore, during early infection, the frequencies of CXCR5+ and CXCR5+ PD-1+ CD4+ T cells in the broad group were similar to those observed in HIV-negative control subjects (Fig. 2B and F). In contrast, a significant reduction in the frequencies of these cells was observed in the narrow group compared to those of HIV-negative subjects (Fig. 2B [P = 0.001] and E [P = 0.002]). These observations suggest that this population of CD4+ T cells is preserved during early HIV-1 infection in those subjects who later develop BNAR and is transiently lost in other subjects.

Plasma levels of CXCL13 uniquely predict the breadth of plasma-neutralizing antibody responses.

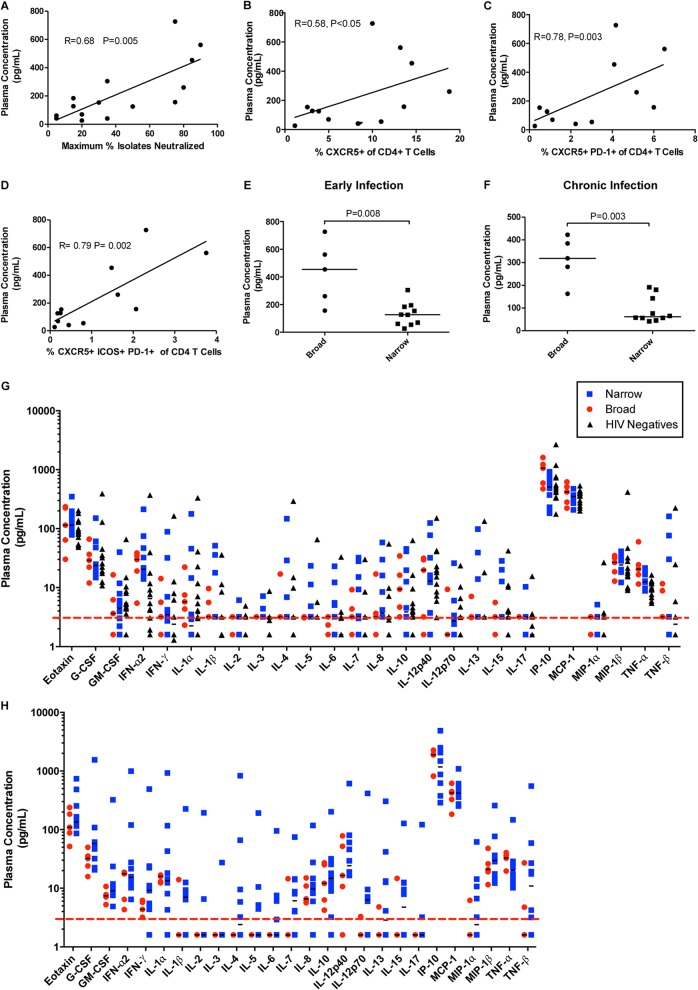

In order to identify underlying factors responsible for the observed differences in CXCR5+ T helper cell frequencies between the broad and narrow groups, we initially evaluated plasma levels of the three cytokines CXCL13, IL-21, and BAFF because they are associated with the interaction of Tfh and B cells. During early infection, plasma levels of CXCL13 were significantly correlated with the maximum breadth of plasma neutralizing antibody responses detected during chronic infection (r = 0.68, P = 0.005) (Fig. 3A) independent of viral load. In addition, plasma CXCL13 concentrations uniquely correlated with CXCR5+ (Fig. 3B) (r = 0.58, P < 0.05), CXCR5+ PD-1+ (Fig. 3C) (r = 0.78, P = 0.003), and CXCR5+ ICOS+ PD-1+ CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3D) (r = 0.79, P = 0.002). Higher plasma concentrations of CXCL13 were observed in the broad than the narrow group at both time points examined (Fig. 3E [P = 0.005] and F [P = 0.003]). In contrast, no association was detected between the breadth of plasma neutralizing antibody responses or the frequencies of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells and the plasma levels of the two other B cell-tropic cytokines examined, IL-21 and BAFF (data not shown).

FIG 3.

Plasma levels of CXCL13 in HIV-1-infected subjects with broad or narrow plasma cross-reactive neutralizing antibody responses. (A) For each subject, CXCL13 concentrations in plasma collected during early infection were plotted against the maximum percentage of heterologous viral isolates neutralized by plasma collected from the same subject during chronic infection (n = 15). Also shown is the frequency of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells (B), CXCR5+ PD-1+ CD4+ T cells (C), and CXCR5+ ICOS+ PD-1+ CD4+ T cells during early infection (n = 12) (D). Each dot represents a single subject and time point. The lines are linear regression curves. The stated r and P values were calculated using Spearman rank correlation for nonparametric data and considered significant if less than 0.05. The plasma concentrations of CXCL13 for either the broad group (n = 5) or narrow group (n = 7) during early (E) and chronic infection (F) are shown. Horizontal lines are at the median plasma concentration values per subject group. The stated P values were calculated using the Mann-Whitney test for nonparametric data and considered significant if less than 0.05. (G and H) Levels of 26 cytokines and chemokines from plasma samples from HIV-1-negative control subjects and during early (G) and chronic (H) infection for the HIV-1-infected subjects. The red dashed line indicates the detection limit (3.2 pg/ml). The horizontal lines are at the medians.

The higher plasma levels of CXCL13 in the broad group may be indicative of systemic increases in cytokine production compared to that of the narrow group. To address this point, we evaluated the plasma levels of an additional 26 cytokines and chemokines (Fig. 3G and H). We observed significantly higher IP-10 plasma concentrations in the broad group during early infection (Fig. 3G) (P = 0.03) but not chronic infection (Fig. 3H). This difference was no longer significant after correcting for multiple comparisons. In contrast to the observation that CXCL13 levels in early infection correlated with the maximum breadth of plasma neutralizing antibody responses detected later in infection, no such correlation was made in the case of IP-10. In contrast, mean IP-10 plasma levels were associated with mean plasma viremia (r = 0.61, P = 0.01) (data not shown), as previously reported (51). While plasma CXCL13 levels have been shown to be significantly associated with viral load during chronic HIV-1 infection (48, 52, 53), CXCL13 plasma levels did not significantly correlate with viral loads in the subjects studied here. Therefore, the plasma levels of CXCL13 were uniquely associated with the development of BNAR and with the frequency of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells and CXCR5+ PD-1+ CD4+ T cells in a virus load-independent manner.

CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells from broad subjects induce greater antibody class-switching.

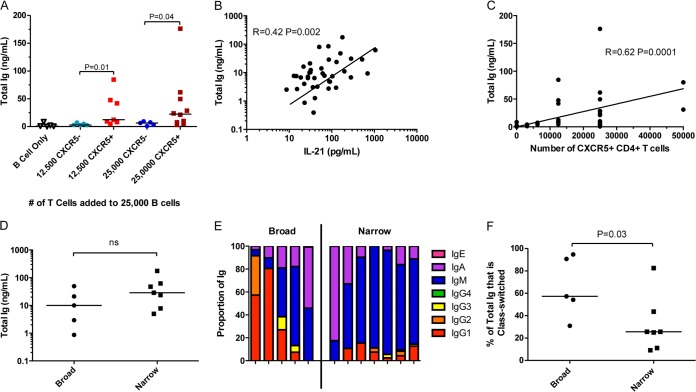

Studies investigating recall immune responses to model antigens in the context of immunization or lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection of mice demonstrated that peripheral CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells, while heterogeneous, preferentially provide B cell help compared to their CXCR5-negative counterparts (35, 37–41, 43). Here, we investigated whether or not CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells also are functional and can provide help to B cells in the context of HIV-1 infection. Indeed, we observed that peripheral CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells isolated during early infection from both the broad and narrow groups were significantly more effective in providing help to autologous naive B cells, as evidenced by increased antibody production (Fig. 4A), than their CXCR5− counterparts. Both the amount of secreted IL-21 (Fig. 4B) (r = 0.42, P = 0.002) and the number of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells in the T and B cell cocultures (Fig. 4C) (r = 0.62, P = 0.0001) correlated with the amount of antibody produced. Interestingly, for equivalent numbers of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells in the cocultures, the amount of antibody or IL-21 secreted did not differ significantly between the broad and narrow groups (Fig. 4D and data not shown). Taken together, these observations suggest that the CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells are more effective than CXCR5− CD4+ T cells in providing help to B cells in a dose-dependent manner in both the broad and narrow groups, and that these cells from both groups are equally effective in assisting the production of antibodies from the naive B cells during early HIV-1 infection. However, despite the fact that similar amounts of antibodies were produced by B cells in the presence of the same number of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells from both the broad and narrow groups, a significantly larger proportion of the antibodies produced by B cells from the broad group were class switched (Fig. 4E and F [P = 0.03]). This difference may be due to more effective T-dependent class switching in the naive B cells, a difference in the preexisting frequency of class-switched CD27− B cells, or differences in B cell activation in vivo between the narrow and broad groups.

FIG 4.

Ability of peripheral CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells compared to CXCR5− CD4+ T cells in providing help to naive B cells in vitro in HIV-1-infected subjects. Autologous naive B cells and CXCR5+ or CXCR5− T cells from subjects of both the broad and narrow groups were isolated from PBMCs collected during early infection. A total of 25,000 naive B cells were cultured with either 0, 12,500, or 25,000 CXCR5− or CXCR5+ autologous CD4+ T cells and stimulated with SEB for 7 days. (A) The amount of total Ig detected in the coculture supernatant from individual subjects (n = 12) is shown. The total amount of Ig detected in these same supernatants was plotted against the amount of IL-21 detected in the supernatant (B) and the number of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells in the coculture (C). (D) A summary of the amount of total Ig detected in cocultures containing equal numbers of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells (25,000) with equal numbers of naive B cells (25,000) for broad (n = 5) and narrow subjects (n = 7) is shown. (E) The proportion of the Ig of each isotype detected in supernatant for each subject in the cocultures containing 25,000 CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells and 25,000 naive B cells is shown. (F) The proportion of the Ig detected which was class switched for each subject group, as summarized in panel E. Each dot represents a single subject (n = 12). The horizontal line is at the median. The stated P values were calculated using the Mann-Whitney test for nonparametric data and considered significant if less than 0.05. The stated r and P values were calculated using Spearman rank correlation for nonparametric data and considered significant if less than 0.05. The lines are linear regression curves.

Preservation of B cell activation profile during early HIV-1 infection in subjects who develop broadly neutralizing antibody responses.

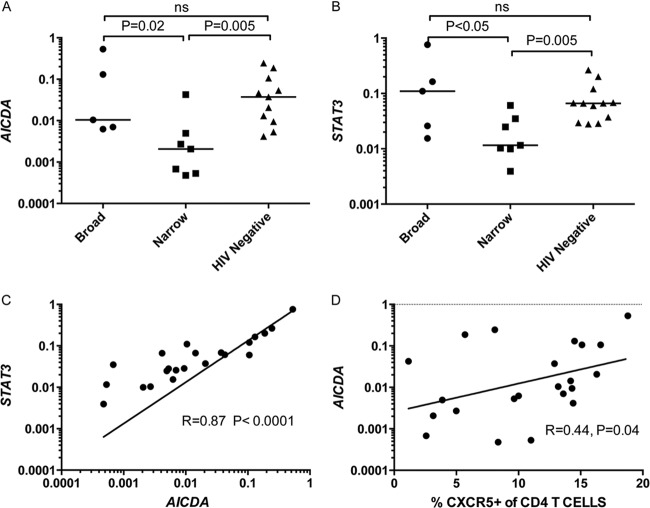

In parallel to the analyses on the frequencies of the above-mentioned CD4+ T cells, we examined the frequencies of naive, memory, and HIV-1 envelope (Env)-specific B cells during early and chronic infection. In contrast to the observed differences in the CD4+ T cell populations discussed above, there were no significant differences between the broad and narrow groups in the frequencies of naive (CD3− CD19+ CD27−), memory (CD3− CD19+ CD27+), or Env-specific memory B cells (CD3− CD19+ CD27+ gp120+) at either time point (data not shown), in agreement with previous reports (54). CXCR5 expression on B cells also did not correlate with the development of BNAR (data not shown). However, ex vivo transcriptional profiling revealed significantly higher expression of activation-associated genes (AICDA, STAT3, IL1A, TNF, CD11b, CD38, CD80, CD95, and FCRL4), IFN-stimulated genes (IFI27 and ISG15), and genes associated with GC B cell chemotaxis (CXCL13 and RGS13) in the subjects of the broad group than the narrow group (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) during early infection. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AICDA), which was found at a higher level in the broad group (P = 0.02) (Fig. 5A), is essential for mediating both the process of affinity maturation, through induction of somatic hypermutation, and class-switch recombination. Additionally, AICDA expression is induced in B cells by Tfh cells via cytokine or ligand-receptor signaling pathways. Likewise, STAT3 expression was upregulated in the broad group compared to the narrow group (Fig. 5B) (P < 0.05). The expression levels of AICDA and STAT3 were highly correlated (Fig. 5C) (r = 0.87, P < 0.001), and each correlated with the frequency of peripheral CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5D) (r = 0.44, P = 0.04) (r = 0.44, P < 0.05) (data not shown) but not with the frequency of CXCR5+ PD-1+ CD4+ T cells (data not shown). No differences in gene expression patterns between the broad and the narrow subjects were observed during chronic infection (see Table S2). Overall, the gene expression levels in the broad group were comparable to those in HIV-1-negative subjects (see Table S1). These results indicate that during early HIV-1 infection, the B cell activation phenotype in HIV-1-infected subjects who develop BNAR later during infection was similar to that of uninfected subjects and correlated with the frequency of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5D) (r = 0.44, P = 0.04).

FIG 5.

STAT3 and AICDA gene expression in B cells ex vivo. Transcript levels for STAT3 and AICDA (relative to GAPDH) in bulk B cells from a single time point for HIV-1-infected and uninfected subjects. AICDA (A) and STAT3 (B) gene expression in the broad (n = 5), narrow (n = 7), and HIV-negative control subjects (n = 11) during early infection is shown. Each dot represents a single subject. The horizontal lines represent the medians. The stated P values were calculated using the Mann-Whitney test for nonparametric data and considered significant if less than 0.05. AICDA transcript levels (relative to GAPDH) were plotted against relative STAT3 transcript levels (C) and the frequency of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells (n = 23) (D). Each dot represents a single subject. The lines on the correlations represent a linear regression curve. The stated r and P values for correlations were calculated using Spearman rank correlation for nonparametric data and considered significant if less than 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Tfh cells have been identified predominantly by their expression of the markers CXCR5 and PD-1 and are of particular interest in the field of vaccine research for their ability to provide help to B cells and promote the development of high-affinity antibodies. With Tfh cells localization in secondary lymphoid organs, a difficult location to routinely sample in human subjects, it has been very encouraging that a related subset of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells has been identified in the periphery (35, 37–41). Furthermore, studies have suggested that the frequencies of GC Tfh and CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells are inherently linked (55–57). Here, we sought to determine whether CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells are involved in the development of broadly neutralizing antibodies during HIV-1 infection. We determined the frequency, phenotype, and functionality of these cells during early HIV-1 infection and the frequency and phenotype of these cells during chronic HIV-1 infection in a cohort of subjects whose neutralizing antibody responses had been thoroughly characterized. We observed correlations between the frequencies of CXCR5+, CXCR5+ PD-1+, and CXCR5+ PD-1+ ICOS+ CD4+ T cells in early infection with the maximum breadth of plasma neutralizing activities during chronic infection. In contrast, and in agreement with previous reports (42, 48), a similar correlation during chronic infection was not observed. Although the frequencies of these CD4+ T cell subsets during chronic infection did not correlate with the breadth of serum neutralization, there remained a trend for the broad subjects to have higher frequencies of these populations. Therefore, since the sample size of our study was quite small, studies of larger cohorts will be needed to make definitive conclusions regarding this important issue. Surprisingly, during early infection, the frequencies of CXCR5+ and CXCR5+ PD-1+ CD4+ T cells in the broad subjects were similar to the frequencies in HIV-1-negative subjects. The frequency of CXCR5+ PD-1+ ICOS+ CD4+ T cells was higher in the broad than in the narrow subjects and HIV-1-negative subjects, and this difference appears to be driven by increased ICOS expression on CD4+ T cells from HIV-1-infected subjects.

We hypothesize that the differences observed in these CD4+ T cell subsets in the periphery correspond to differences in the frequencies of these subsets in secondary lymphoid organs. We propose that differences in these CD4+ T cells subpopulations are linked with the eventual development or not of BNAR during chronic HIV-1 infection. Tfh cells are susceptible to HIV-1 infection (46), as, presumably, are peripheral CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells, and the mechanism(s) allowing for the preservation of CXCR5+ (PD-1+) CD4+ T cells during early HIV-1 infection in the subset of HIV-1-infected subjects who develop BNAR presently is unknown. It is possible that cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses generated during the early phase of HIV-1 infection (58) were more effective in killing autologous HIV-1-infected CXCR5+ (PD-1+) CD4+ T cells in subjects who did not develop BNAR. Alternatively, it is possible that CXCR5+ (PD-1+) CD4+ T cell frequencies declined very early after HIV-1 infection in all subjects studied here but were actively replenished in the subjects who later developed BNAR.

Circulating CD4+ T cells that express CXCR5 likely contain a subset of cells that are specialized in providing help to B cells. However, the functionality of these cells during viremic HIV-1 infection remains unclear. Therefore, it was important to confirm that CXCR5 distinguishes CD4+ T cells capable of providing help to B cells during viremic HIV-1 infection. The observation that there were no differences in the amount of antibodies produced by B cells in the cocultures from broad or narrow subjects suggests that there were no inherent defects in the ability of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells from the narrow subjects to provide help to B cells. However, a greater fraction of the antibodies produced in the cocultures from the broad subjects were class switched. Indeed, during early infection, B cells from the broad subjects had higher levels of AICDA transcripts and displayed a gene expression profile similar to that of HIV-1-uninfected subjects.

Along with higher AICDA levels, B cells from the broad subjects also expressed higher levels of STAT3 gene expression during the first year of infection. STAT3 regulates B cell differentiation and is induced by IL-6 and IL-21 signaling. The increased expression of STAT3 may be indicative of increased IL-21 stimulation in the broad subjects. IL-21 is secreted by Tfh cells (59), and IL-21 STAT3-mediated signal transduction can induce AICDA expression (60), which is supported by the strong correlation between AICDA and STAT3 gene expression and further suggests that they are mechanistically linked (Fig. 5).

Based on these observations, we propose a model in which the development of BNAR in HIV-1 infection is dependent on the early preservation of CXCR5+ (PD-1+) CD4+ T cells. This model is similar to what has been described during LCMV infection, where the ability of the neutralizing antibody response to broaden and evolve is limited by the availability and functionality of CD4+ T cell help (61). The data presented here suggest that in early HIV-1 infection the subjects from the narrow group suffer a deficit in B cell activation, potentially related to the loss of Tfh cells. It has been shown that the Tfh-B cell interaction is impaired during chronic HIV-1 infection (47, 48). Therefore, maintaining physiological frequencies of Tfh cells early following infection appears to be crucial for the development of BNAR, most likely due to their pivotal role in maturation of the antibody response (62, 63). Affinity maturation is considered essential for the generation of broadly neutralizing antibodies, as those that have been isolated from chronic HIV-1 infection were extensively hypermutated (64–66). In our study, we looked only at global CXCR5+ CD4+ T cell frequencies and phenotypes. As the interaction between Tfh and B cells is pathogen specific, further studies will be needed to identify the contribution of HIV-1-specific peripheral Tfh (pTfh) cells.

The development of a BNAR is multifaceted and likely requires the activation of B cell receptors (BCRs) that recognize conserved epitopes on the HIV-1 Env (67). Thus, in addition to maintaining Tfh cells during the early stages of infection, it is equally important for BCRs to target specific epitopes on HIV-1 Env. While BNAR take significant time to develop during HIV-1 infection, antibody lineages which later become broadly neutralizing have been detected as early as 14 weeks postinfection, highlighting the importance of this early window in infection in the development of these responses (68). Our findings support a previous study linking the phenotype of CXCR5+ CD4+ T cells early after HIV-1 infection to the development of broad neutralizing antibody responses (42). Further, our results implicate the maintenance of this population as important for maintaining physiological levels of B cell activation. These findings have implications for predicting who will eventually develop BNAR after infection with HIV-1. Ultimately, the evaluation and modulation of responses during vaccination may be essential for the induction of high-affinity and broad neutralizing antibody responses.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the study participants. Without their contributions of time and blood samples, this research would not be possible. We also thank Peter Gilbert for his insights on this analysis.

These studies were supported by NIAID R01AI081625.

We have no conflicting financial interests.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 10 September 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02186-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Binley J, Lybarger E, Crooks E, Seaman M, Gray E, Davis K, Decker J, Wycuff D, Harris L, Hawkins N, Wood B, Nathe C, Richman D, Tomaras G, Bibollet-Ruche F, Robinson J, Morris L, Shaw G, Montefiori D, Mascola J. 2008. Profiling the specificity of neutralizing antibodies in a large panel of plasmas from patients chronically infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtypes B and C. J. Virol. 82:11651–11668. 10.1128/JVI.01762-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doria-Rose N, Klein R, Daniels M, O'Dell S, Nason M, Lapedes A, Bhattacharya T, Migueles S, Wyatt R, Korber B, Mascola J, Connors M. 2010. Breadth of human immunodeficiency virus-specific neutralizing activity in sera: clustering analysis and association with clinical variables. J. Virol. 84:1631–1636. 10.1128/JVI.01482-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nandi A, Lavine C, Wang P, Lipchina I, Goepfert P, Shaw G, Tomaras G, Montefiori D, Haynes B, Easterbrook P, Robinson J, Sodroski J, Yang X. 2010. Epitopes for broad and potent neutralizing antibody responses during chronic infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Virology 396:339–348. 10.1016/j.virol.2009.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sather D, Armann J, Ching L, Mavrantoni A, Sellhorn G, Caldwell Z, Yu X, Wood B, Self S, Kalams S, Stamatatos L. 2009. Factors associated with the development of cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 83:757–769. 10.1128/JVI.02036-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simek M, Rida W, Priddy F, Pung P, Carrow E, Laufer D, Lehrman J, Boaz M, Tarragona-Fiol T, Miiro G, Birungi J, Pozniak A, McPhee D, Manigart O, Karita E, Inwoley A, Jaoko W, Dehovitz J, Bekker L, Pitisuttithum P, Paris R, Walker L, Poignard P, Wrin T, Fast P, Burton D, Koff W. 2009. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 elite neutralizers: individuals with broad and potent neutralizing activity identified by using a high-throughput neutralization assay together with an analytical selection algorithm. J. Virol. 83:7337–7348. 10.1128/JVI.00110-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Gils M, Euler Z, Schweighardt B, Wrin T, Schuitemaker H. 2009. Prevalence of cross-reactive HIV-1-neutralizing activity in HIV-1-infected patients with rapid or slow disease progression. AIDS 23:2405–2414. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833243e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mikell I, Sather DN, Kalams SA, Altfeld M, Alter G, Stamatatos L. 2011. Characteristics of the earliest cross-neutralizing antibody response to HIV-1. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1001251. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baba TW, Liska V, Hofmann-Lehmann R, Vlasak J, Xu W, Ayehunie S, Cavacini LA, Posner MR, Katinger H, Stiegler G, Bernacky BJ, Rizvi TA, Schmidt R, Hill LR, Keeling ME, Lu Y, Wright JE, Chou TC, Ruprecht RM. 2000. Human neutralizing monoclonal antibodies of the IgG1 subtype protect against mucosal simian-human immunodeficiency virus infection. Nat. Med. 6:200–206. 10.1038/72309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burton DR, Hessell AJ, Keele BF, Klasse PJ, Ketas TA, Moldt B, Dunlop DC, Poignard P, Doyle LA, Cavacini L, Veazey RS, Moore JP. 2011. Limited or no protection by weakly or nonneutralizing antibodies against vaginal SHIV challenge of macaques compared with a strongly neutralizing antibody. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:11181–11186. 10.1073/pnas.1103012108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hessell AJ, Rakasz EG, Poignard P, Hangartner L, Landucci G, Forthal DN, Koff WC, Watkins DI, Burton DR. 2009. Broadly neutralizing human anti-HIV antibody 2G12 is effective in protection against mucosal SHIV challenge even at low serum neutralizing titers. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000433. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hessell AJ, Rakasz EG, Tehrani DM, Huber M, Weisgrau KL, Landucci G, Forthal DN, Koff WC, Poignard P, Watkins DI, Burton DR. 2010. Broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies 2F5 and 4E10 directed against the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 membrane-proximal external region protect against mucosal challenge by simian-human immunodeficiency virus SHIVBa-L. J. Virol. 84:1302–1313. 10.1128/JVI.01272-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marx PA, Compans RW, Gettie A, Staas JK, Gilley RM, Mulligan MJ, Yamshcikov GV, Chen D, Eldridge JH. 1993. Protection against vaginal SIV transmission with microencapsulated vaccine. Science 260:1323–1327. 10.1126/science.8493576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mascola JR, Lewis MG, Stiegler G, Harris D, VanCott TC, Hayes D, Louder MK, Brown CR, Sapan CV, Frankel SS, Lu Y, Robb ML, Katinger H, Birx DL. 1999. Protection of macaques against pathogenic simian/human immunodeficiency virus 89.6PD by passive transfer of neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 73:4009–4018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moldt B, Rakasz EG, Schultz N, Chan-Hui PY, Swiderek K, Weisgrau KL, Piaskowski SM, Bergman Z, Watkins DI, Poignard P, Burton DR. 2012. Highly potent HIV-specific antibody neutralization in vitro translates into effective protection against mucosal SHIV challenge in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:18921–18925. 10.1073/pnas.1214785109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parren PW, Marx PA, Hessell AJ, Luckay A, Harouse J, Cheng-Mayer C, Moore JP, Burton DR. 2001. Antibody protects macaques against vaginal challenge with a pathogenic R5 simian/human immunodeficiency virus at serum levels giving complete neutralization in vitro. J. Virol. 75:8340–8347. 10.1128/JVI.75.17.8340-8347.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barouch DH, Whitney JB, Moldt B, Klein F, Oliveira TY, Liu J, Stephenson KE, Chang HW, Shekhar K, Gupta S, Nkolola JP, Seaman MS, Smith KM, Borducchi EN, Cabral C, Smith JY, Blackmore S, Sanisetty S, Perry JR, Beck M, Lewis MG, Rinaldi W, Chakraborty AK, Poignard P, Nussenzweig MC, Burton DR. 2013. Therapeutic efficacy of potent neutralizing HIV-1-specific monoclonal antibodies in SHIV-infected rhesus monkeys. Nature 503:224–228. 10.1038/nature12744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadjadpour R, Donau OK, Shingai M, Buckler-White A, Kao S, Strebel K, Nishimura Y, Martin MA. 2013. Emergence of gp120 V3 variants confers neutralization resistance in an R5 simian-human immunodeficiency virus-infected macaque elite neutralizer that targets the N332 glycan of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 87:8798–8804. 10.1128/JVI.00878-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shingai M, Nishimura Y, Klein F, Mouquet H, Donau OK, Plishka R, Buckler-White A, Seaman M, Piatak M, Jr, Lifson JD, Dimitrov DS, Nussenzweig MC, Martin MA. 2013. Antibody-mediated immunotherapy of macaques chronically infected with SHIV suppresses viraemia. Nature 503:277–280. 10.1038/nature12746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein F, Halper-Stromberg A, Horwitz JA, Gruell H, Scheid JF, Bournazos S, Mouquet H, Spatz LA, Diskin R, Abadir A, Zang T, Dorner M, Billerbeck E, Labitt RN, Gaebler C, Marcovecchio PM, Incesu RB, Eisenreich TR, Bieniasz PD, Seaman MS, Bjorkman PJ, Ravetch JV, Ploss A, Nussenzweig MC. 2012. HIV therapy by a combination of broadly neutralizing antibodies in humanized mice. Nature 492:118–122. 10.1038/nature11604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trkola A, Kuster H, Rusert P, Joos B, Fischer M, Leemann C, Manrique A, Huber M, Rehr M, Oxenius A, Weber R, Stiegler G, Vcelar B, Katinger H, Aceto L, Günthard HF. 2005. Delay of HIV-1 rebound after cessation of antiretroviral therapy through passive transfer of human neutralizing antibodies. Nat. Med. 11:615–622. 10.1038/nm1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manrique A, Rusert P, Joos B, Fischer M, Kuster H, Leemann C, Niederost B, Weber R, Stiegler G, Katinger H, Gunthard HF, Trkola A. 2007. In vivo and in vitro escape from neutralizing antibodies 2G12, 2F5, and 4E10. J. Virol. 81:8793–8808. 10.1128/JVI.00598-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burton DR, Ahmed R, Barouch DH, Butera ST, Crotty S, Godzik A, Kaufmann DE, McElrath MJ, Nussenzweig MC, Pulendran B, Scanlan CN, Schief WR, Silvestri G, Streeck H, Walker BD, Walker LM, Ward AB, Wilson IA, Wyatt R. 2012. A blueprint for HIV vaccine discovery. Cell Host Microbe 12:396–407. 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mascola JR, Montefiori DC. 2010. The role of antibodies in HIV vaccines. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 28:413–444. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basavapathruni A, Yeh WW, Coffey RT, Whitney JB, Hraber PT, Giri A, Korber BT, Rao SS, Nabel GJ, Mascola JR, Seaman MS, Letvin NL. 2010. Envelope vaccination shapes viral envelope evolution following simian immunodeficiency virus infection in rhesus monkeys. J. Virol. 84:953–963. 10.1128/JVI.01679-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stamatatos L. 2012. HIV vaccine design: the neutralizing antibody conundrum. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 24:316–323. 10.1016/j.coi.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haynes BF, Montefiori DC. 2006. Aiming to induce broadly reactive neutralizing antibody responses with HIV-1 vaccine candidates. Expert Rev. Vaccines 5:579–595. 10.1586/14760584.5.4.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eisen HN, Siskind GW. 1964. Variations in affinities of antibodies during the immune response. Biochemistry 3:996–1008. 10.1021/bi00895a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.French DL, Laskov R, Scharff MD. 1989. The role of somatic hypermutation in the generation of antibody diversity. Science 244:1152–1157. 10.1126/science.2658060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siskind GW, Benacerraf B. 1969. Cell selection by antigen in the immune response. Adv. Immunol. 10:1–50. 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)60414-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiss U, Zoebelein R, Rajewsky K. 1992. Accumulation of somatic mutants in the B cell compartment after primary immunization with a T cell-dependent antigen. Eur. J. Immunol. 22:511–517. 10.1002/eji.1830220233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liao HX, Lynch R, Zhou T, Gao F, Alam SM, Boyd SD, Fire AZ, Roskin KM, Schramm CA, Zhang Z, Zhu J, Shapiro L, NISC Comparative Sequencing Program. Mullikin JC, Gnanakaran S, Hraber P, Wiehe K, Kelsoe G, Yang G, Xia SM, Montefiori DC, Parks R, Lloyd KE, Scearce RM, Soderberg KA, Cohen M, Kamanga G, Louder MK, Tran LM, Chen Y, Cai F, Chen S, Moquin S, Du X, Joyce MG, Srivatsan S, Zhang B, Zheng A, Shaw GM, Hahn BH, Kepler TB, Korber BT, Kwong PD, Mascola JR, Haynes BF. 2013. Co-evolution of a broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibody and founder virus. Nature 496:469–476. 10.1038/nature12053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crotty S. 2011. Follicular helper CD4 T cells (TFH). Annu. Rev. Immunol. 29:621–663. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu D, Rao S, Tsai LM, Lee SK, He Y, Sutcliffe EL, Srivastava M, Linterman M, Zheng L, Simpson N, Ellyard JI, Parish IA, Ma CS, Li QJ, Parish CR, Mackay CR, Vinuesa CG. 2009. The transcriptional repressor Bcl-6 directs T follicular helper cell lineage commitment. Immunity 31:457–468. 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Breitfeld D, Ohl L, Kremmer E, Ellwart J, Sallusto F, Lipp M, Forster R. 2000. Follicular B helper T cells express CXC chemokine receptor 5, localize to B cell follicles, and support immunoglobulin production. J. Exp. Med. 192:1545–1552. 10.1084/jem.192.11.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schaerli P, Willimann K, Lang AB, Lipp M, Loetscher P, Moser B. 2000. CXC chemokine receptor 5 expression defines follicular homing T cells with B cell helper function. J. Exp. Med. 192:1553–1562. 10.1084/jem.192.11.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nurieva RI, Chung Y, Martinez GJ, Yang XO, Tanaka S, Matskevitch TD, Wang YH, Dong C. 2009. Bcl6 mediates the development of T follicular helper cells. Science 325:1001–1005. 10.1126/science.1176676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim CH, Rott LS, Clark-Lewis I, Campbell DJ, Wu L, Butcher EC. 2001. Subspecialization of CXCR5+ T cells: B helper activity is focused in a germinal center-localized subset of CXCR5+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 193:1373–1381. 10.1084/jem.193.12.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morita R, Schmitt N, Bentebibel SE, Ranganathan R, Bourdery L, Zurawski G, Foucat E, Dullaers M, Oh S, Sabzghabaei N, Lavecchio EM, Punaro M, Pascual V, Banchereau J, Ueno H. 2011. Human blood CXCR5(+)CD4(+) T cells are counterparts of T follicular cells and contain specific subsets that differentially support antibody secretion. Immunity 34:108–121. 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chevalier N, Jarrossay D, Ho E, Avery DT, Ma CS, Yu D, Sallusto F, Tangye SG, Mackay CR. 2011. CXCR5 expressing human central memory CD4 T cells and their relevance for humoral immune responses. J. Immunol. 186:5556–5568. 10.4049/jimmunol.1002828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.MacLeod MK, David A, McKee AS, Crawford F, Kappler JW, Marrack P. 2011. Memory CD4 T cells that express CXCR5 provide accelerated help to B cells. J. Immunol. 186:2889–2896. 10.4049/jimmunol.1002955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hale JS, Youngblood B, Latner DR, Mohammed AU, Ye L, Akondy RS, Wu T, Iyer SS, Ahmed R. 2013. Distinct memory CD4 T cells with commitment to T follicular helper- and T helper 1-cell lineages are generated after acute viral infection. Immunity 38:805–817. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Locci M, Havenar-Daughton C, Landais E, Wu J, Kroenke MA, Arlehamn CL, Su LF, Cubas R, Davis MM, Sette A, Haddad EK, International AIDS Vaccine Initiative Protocol C Principal Investigators. Poignard P, Crotty S. 2013. Human circulating PD-1CXCR3CXCR5 memory Tfh cells are highly functional and correlate with broadly neutralizing HIV antibody responses. Immunity 39:758–769. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simpson N, Gatenby PA, Wilson A, Malik S, Fulcher DA, Tangye SG, Manku H, Vyse TJ, Roncador G, Huttley GA, Goodnow CC, Vinuesa CG, Cook MC. 2010. Expansion of circulating T cells resembling follicular helper T cells is a fixed phenotype that identifies a subset of severe systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 62:234–244. 10.1002/art.25032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petrovas C, Yamamoto T, Gerner MY, Boswell KL, Wloka K, Smith EC, Ambrozak DR, Sandler NG, Timmer KJ, Sun X, Pan L, Poholek A, Rao SS, Brenchley JM, Alam SM, Tomaras GD, Roederer M, Douek DC, Seder RA, Germain RN, Haddad EK, Koup RA. 2012. CD4 T follicular helper cell dynamics during SIV infection. J. Clin. Investig. 122:3281–3294. 10.1172/JCI63039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu Y, Weatherall C, Bailey M, Alcantara S, De Rose R, Estaquier J, Wilson K, Suzuki K, Corbeil J, Cooper DA, Kent SJ, Kelleher AD, Zaunders J. 2013. Simian immunodeficiency virus infects follicular helper CD4 T cells in lymphoid tissues during pathogenic infection of pigtail macaques. J. Virol. 87:3760–3773. 10.1128/JVI.02497-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perreau M, Savoye AL, De Crignis E, Corpataux JM, Cubas R, Haddad EK, De Leval L, Graziosi C, Pantaleo G. 2013. Follicular helper T cells serve as the major CD4 T cell compartment for HIV-1 infection, replication, and production. J. Exp. Med. 210:143–156. 10.1084/jem.20121932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cubas RA, Mudd JC, Savoye AL, Perreau M, van Grevenynghe J, Metcalf T, Connick E, Meditz A, Freeman GJ, Abesada-Terk G, Jr, Jacobson JM, Brooks AD, Crotty S, Estes JD, Pantaleo G, Lederman MM, Haddad EK. 2013. Inadequate T follicular cell help impairs B cell immunity during HIV infection. Nat. Med. 19:494–499. 10.1038/nm.3109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boswell KL, Paris R, Boritz E, Ambrozak D, Yamamoto T, Darko S, Wloka K, Wheatley A, Narpala S, McDermott A, Roederer M, Haubrich R, Connors M, Ake J, Douek DC, Kim J, Petrovas C, Koup RA. 2014. Loss of circulating CD4 T cells with B cell helper function during chronic HIV infection. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1003853. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Storey JD, Tibshirani R. 2003. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:9440–9445. 10.1073/pnas.1530509100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lindqvist M, van Lunzen J, Soghoian DZ, Kuhl BD, Ranasinghe S, Kranias G, Flanders MD, Cutler S, Yudanin N, Muller MI, Davis I, Farber D, Hartjen P, Haag F, Alter G, Schulze zur Wiesch J, Streeck H. 2012. Expansion of HIV-specific T follicular helper cells in chronic HIV infection. J. Clin. Investig. 122:3271–3280. 10.1172/JCI64314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simmons RP, Scully EP, Groden EE, Arnold KB, Chang JJ, Lane K, Lifson J, Rosenberg E, Lauffenburger DA, Altfeld M. 2013. HIV-1 infection induces strong production of IP-10 through TLR7/9-dependent pathways. AIDS 27:2505–2517. 10.1097/01.aids.0000432455.06476.bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Widney DP, Breen EC, Boscardin WJ, Kitchen SG, Alcantar JM, Smith JB, Zack JA, Detels R, Martinez-Maza O. 2005. Serum levels of the homeostatic B cell chemokine, CXCL13, are elevated during HIV infection. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 25:702–706. 10.1089/jir.2005.25.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cagigi A, Mowafi F, Phuong Dang LV, Tenner-Racz K, Atlas A, Grutzmeier S, Racz P, Chiodi F, Nilsson A. 2008. Altered expression of the receptor-ligand pair CXCR5/CXCL13 in B cells during chronic HIV-1 infection. Blood 112:4401–4410. 10.1182/blood-2008-02-140426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Doria-Rose NA, Klein RM, Manion MM, O'Dell S, Phogat A, Chakrabarti B, Hallahan CW, Migueles SA, Wrammert J, Ahmed R, Nason M, Wyatt RT, Mascola JR, Connors M. 2009. Frequency and phenotype of human immunodeficiency virus envelope-specific B cells from patients with broadly cross-neutralizing antibodies. J. Virol. 83:188–199. 10.1128/JVI.01583-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Warnatz K, Bossaller L, Salzer U, Skrabl-Baumgartner A, Schwinger W, van der Burg M, van Dongen JJ, Orlowska-Volk M, Knoth R, Durandy A, Draeger R, Schlesier M, Peter HH, Grimbacher B. 2006. Human ICOS deficiency abrogates the germinal center reaction and provides a monogenic model for common variable immunodeficiency. Blood 107:3045–3052. 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bossaller L, Burger J, Draeger R, Grimbacher B, Knoth R, Plebani A, Durandy A, Baumann U, Schlesier M, Welcher AA, Peter HH, Warnatz K. 2006. ICOS deficiency is associated with a severe reduction of CXCR5+CD4 germinal center Th cells. J. Immunol. 177:4927–4932. 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Havenith SH, Remmerswaal EB, Idu MM, van Donselaar-van der Pant KA, van der Bom N, Bemelman FJ, van Leeuwen EM, Ten Berge IJ, van Lier RA. 2013. CXCR5+ CD4+ follicular helper T cells accumulate in resting human lymph nodes and have superior B cell helper activity. Int. Immunol. 26:183–192. 10.1093/intimm/dxt058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koup RA, Safrit JT, Cao Y, Andrews CA, McLeod G, Borkowsky W, Farthing C, Ho DD. 1994. Temporal association of cellular immune responses with the initial control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 syndrome. J. Virol. 68:4650–4655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Avery DT, Deenick EK, Ma CS, Suryani S, Simpson N, Chew GY, Chan TD, Palendira U, Bustamante J, Boisson-Dupuis S, Choo S, Bleasel KE, Peake J, King C, French MA, Engelhard D, Al-Hajjar S, Al-Muhsen S, Magdorf K, Roesler J, Arkwright PD, Hissaria P, Riminton DS, Wong M, Brink R, Fulcher DA, Casanova J-L, Cook MC, Tangye SG. 2010. B cell-intrinsic signaling through IL-21 receptor and STAT3 is required for establishing long-lived antibody responses in humans. J. Exp. Med. 207:155–171. 10.1084/jem.20091706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lafarge S, Hamzeh-Cognasse H, Richard Y, Pozzetto B, Cogne M, Cognasse F, Garraud O. 2011. Complexes between nuclear factor-kappaB p65 and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 are key actors in inducing activation-induced cytidine deaminase expression and immunoglobulin A production in CD40L plus interleukin-10-treated human blood B cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 166:171–183. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04465.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ciurea A, Hunziker L, Klenerman P, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. 2001. Impairment of CD4(+) T cell responses during chronic virus infection prevents neutralizing antibody responses against virus escape mutants. J. Exp. Med. 193:297–305. 10.1084/jem.193.3.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schwickert TA, Victora GD, Fooksman DR, Kamphorst AO, Mugnier MR, Gitlin AD, Dustin ML, Nussenzweig MC. 2011. A dynamic T cell-limited checkpoint regulates affinity-dependent B cell entry into the germinal center. J. Exp. Med. 208:1243–1252. 10.1084/jem.20102477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Victora GD, Schwickert TA, Fooksman DR, Kamphorst AO, Meyer-Hermann M, Dustin ML, Nussenzweig MC. 2010. Germinal center dynamics revealed by multiphoton microscopy with a photoactivatable fluorescent reporter. Cell 143:592–605. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wu X, Zhou T, Zhu J, Zhang B, Georgiev I, Wang C, Chen X, Longo NS, Louder M, McKee K, O'Dell S, Perfetto S, Schmidt SD, Shi W, Wu L, Yang Y, Yang ZY, Yang Z, Zhang Z, Bonsignori M, Crump JA, Kapiga SH, Sam NE, Haynes BF, Simek M, Burton DR, Koff WC, Doria-Rose NA, Connors M, Mullikin JC, Nabel GJ, Roederer M, Shapiro L, Kwong PD, Mascola JR, NISC Comparative Sequencing Program 2011. Focused evolution of HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies revealed by structures and deep sequencing. Science 333:1593–1602. 10.1126/science.1207532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Scheid JF, Mouquet H, Ueberheide B, Diskin R, Klein F, Oliveira TY, Pietzsch J, Fenyo D, Abadir A, Velinzon K, Hurley A, Myung S, Boulad F, Poignard P, Burton DR, Pereyra F, Ho DD, Walker BD, Seaman MS, Bjorkman PJ, Chait BT, Nussenzweig MC. 2011. Sequence and structural convergence of broad and potent HIV antibodies that mimic CD4 binding. Science 333:1633–1637. 10.1126/science.1207227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Klein F, Diskin R, Scheid JF, Gaebler C, Mouquet H, Georgiev IS, Pancera M, Zhou T, Incesu RB, Fu BZ, Gnanapragasam PN, Oliveira TY, Seaman MS, Kwong PD, Bjorkman PJ, Nussenzweig MC. 2013. Somatic mutations of the immunoglobulin framework are generally required for broad and potent HIV-1 neutralization. Cell 153:126–138. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kwong PD, Mascola JR. 2012. Human antibodies that neutralize HIV-1: identification, structures, and B cell ontogenies. Immunity 37:412–425. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liao HX, Lynch R, Zhou T, Gao F, Alam SM, Boyd SD, Fire AZ, Roskin KM, Schramm CA, Zhang Z, Zhu J, Shapiro L, NISC Comparative Sequencing Program. Becker J, Benjamin B, Blakesley R, Bouffard G, Brooks S, Coleman H, Dekhtyar M, Gregory M, Guan X, Gupta J, Han J, Hargrove A, Ho SL, Johnson T, Legaspi R, Lovett S, Maduro Q, Masiello C, Maskeri B, McDowell J, Montemayor C, Mullikin J, Park M, Riebow N, Schandler K, Schmidt B, Sison C, Stantripop M, Thomas J, Thomas P, Vemulapalli M, Young A, Mullikin JC, Gnanakaran S, Hraber P, Wiehe K, Kelsoe G, Yang G, Xia SM, Montefiori DC, Parks R, Lloyd KE, Scearce RM, Soderberg KA, Cohen M, Kamanga G, Louder MK, Tran LM, Chen Y, Cai F, Chen S, Moquin S, Du X, Joyce MG, Srivatsan S, Zhang B, Zheng A, Shaw GM, Hahn BH, Kepler TB, Korber BT, Kwong PD, Mascola JR, Haynes BF. 2013. Co-evolution of a broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibody and founder virus. Nature 496:469–476. 10.1038/nature12053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.